Wikipedia:Reference desk/Science: Difference between revisions

→Dream induced nauseaPascal yuiop (talk) 21:14, 26 July 2011 (UTC): move sig to text from header |

|||

| Line 407: | Line 407: | ||

:It's definitely a butterfly. Butterflies hold their wings vertically at rest, moths fold theirs flat. I think it's a type of [[swallowtail butterfly]]. [[User:SemanticMantis|SemanticMantis]] ([[User talk:SemanticMantis|talk]]) 03:54, 27 July 2011 (UTC) |

:It's definitely a butterfly. Butterflies hold their wings vertically at rest, moths fold theirs flat. I think it's a type of [[swallowtail butterfly]]. [[User:SemanticMantis|SemanticMantis]] ([[User talk:SemanticMantis|talk]]) 03:54, 27 July 2011 (UTC) |

||

::Your image agrees closely with this one [http://lightningbuglodge.blogspot.com/2011_01_01_archive.html], which says it is a spicebush swallowtail. Our article [[spicebush swallowtail]] has a similar but different picture. The differences could be due [[sexual dimorphism]], or perhaps more than one species goes by that common name. [[User:SemanticMantis|SemanticMantis]] ([[User talk:SemanticMantis|talk]]) 04:03, 27 July 2011 (UTC) |

::Your image agrees closely with this one [http://lightningbuglodge.blogspot.com/2011_01_01_archive.html], which says it is a spicebush swallowtail. Our article [[spicebush swallowtail]] has a similar but different picture. The differences could be due [[sexual dimorphism]], or perhaps more than one species goes by that common name. [[User:SemanticMantis|SemanticMantis]] ([[User talk:SemanticMantis|talk]]) 04:03, 27 July 2011 (UTC) |

||

== As seen in [[Knowing (film)]], could a solar-megaflare kill literally everyone on Earth? == |

|||

When I saw the spoilers of the end-scenes on YouTube, my first thoughts were: |

|||

#What about anyone in bunkers deep underground? Could they survive there? |

|||

#How about in submarines deep under the oceans? How far down could the solar flares hit there? |

|||

I would have confidence that being deep enough underground or underwater would ensure survival. What do you make of this? --[[Special:Contributions/70.179.165.67|70.179.165.67]] ([[User talk:70.179.165.67|talk]]) 05:55, 27 July 2011 (UTC) |

|||

Revision as of 05:55, 27 July 2011

of the Wikipedia reference desk.

Main page: Help searching Wikipedia

How can I get my question answered?

- Select the section of the desk that best fits the general topic of your question (see the navigation column to the right).

- Post your question to only one section, providing a short header that gives the topic of your question.

- Type '~~~~' (that is, four tilde characters) at the end – this signs and dates your contribution so we know who wrote what and when.

- Don't post personal contact information – it will be removed. Any answers will be provided here.

- Please be as specific as possible, and include all relevant context – the usefulness of answers may depend on the context.

- Note:

- We don't answer (and may remove) questions that require medical diagnosis or legal advice.

- We don't answer requests for opinions, predictions or debate.

- We don't do your homework for you, though we'll help you past the stuck point.

- We don't conduct original research or provide a free source of ideas, but we'll help you find information you need.

How do I answer a question?

Main page: Wikipedia:Reference desk/Guidelines

- The best answers address the question directly, and back up facts with wikilinks and links to sources. Do not edit others' comments and do not give any medical or legal advice.

July 23

About thiruchendur nazhi kinaru

what is the reason for the pure water in thiruchendur nazhi kinaru? since it has backish water in the some well and sea water near by — Preceding unsigned comment added by Panneerzeus (talk • contribs) 06:53, 23 July 2011 (UTC)

- I don't know anything about the area, or where the wells are. But often there is a halocline in underground caverns, or in groundwater, or even in coastal ocean waters. Here is a diagram for the area of fresh water beneath a small island, for example. A well in the right place might tap the fresh water that runs from higher ground, even if there is salt water in a deeper well. But I don't know that is true for thiruchendur. Wnt (talk) 22:01, 23 July 2011 (UTC)

Regarding contour

integral((1/p)exp(-(p+img.a)^2) where img.-imaginary iota, a-constant, integeral limit -infinity to +infinity — Preceding unsigned comment added by Md qutubuddin (talk • contribs) 07:19, 23 July 2011 (UTC)

- If you type that expression into Wolfram Alpha, with img changed to i, you get an answer. --Heron (talk) 09:11, 23 July 2011 (UTC)

- Using this http://www.wolframalpha.com/input/?i=+integral%28+%281%2Fp%29exp%28-%28p%2Bi.a%29^2%29%29+dp+p%3D-infinity..%2Binfinity I get integral does not converge, with a substituted with some example numbers. Graeme Bartlett (talk) 13:50, 23 July 2011 (UTC)

Scale factor with distance

By what factor does an object shrink as you move away from it? More specifically, if you are looking at a circle of radius 1 at a distance of 1 unit and you move back to 2 units, what will the radius be? I've looked around for an answer, but haven't been able to find one, I'm sure there is a wealth of information out there on such subjects, I just can't figure out the right search terms; everything seems to bring up discussions on 20/20 vision and zoom lens, neither of which are what I'm looking for. Thank you:-)

Edit: I just realized that the circle isn't the best example since if it is flat, then not every point is equidistant to you. Basically, how does size change with distance from an object? 209.252.235.206 (talk) 07:32, 23 July 2011 (UTC)

- The article called Perspective (visual) may help. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 08:44, 23 July 2011 (UTC)

- Basically, if you double the distance, the radius appears halved, the area appears one quarter of the size, and the volume appears one eighth. Similarly, if you triple the distance, radius will be 1/3, area 1/9 and volume 1/27. The scientific principle is that apparent linear size is inversely proportional to distance; the area factor is the square of the linear factor, and the volume factor is the cube. If you are interested in artistic representation then Vanishing point also needs to be considered. Dbfirs 11:23, 23 July 2011 (UTC)

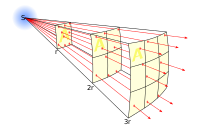

- Inverse square law may be useful. --Cookatoo.ergo.ZooM (talk) 12:20, 23 July 2011 (UTC)

The lines represent the flux emanating from the source.

- It sounds like you want a simple equation to calculate magnification. Magnification is trivially defined as "apparent length / true length." But, this will not work for simple viewing of a distant object. There is no "apparent length" to put into the equation! When you view a distant object, you are seeing an angular size, not a length. So, you can not trivially obtain a magnification relative to the object's true size.

- The angle subtended is θ ; the distance to the subject is r; and the object's length can be denoted s; so you can use either the standard circle formula, s = r θ (which is a slight approximation); or the triangular formula, s = 2 r tan (θ/2) ≈ r θ for small angles. The formulas I presented above work with the angle subtended, not the magnification factor; you need to have a reference size or reference angle in order to compute optical magnification as a ratio. Typically, in photography, you would compare the object's true size to the size of an image projected onto 35 mm film. You could also compare to the image projected inside your eyeball: you would use the geometry/physiology of your eyeball's retina imaging plane and your eye lens. In cameras, the "magnification" factor used by the marketing department is the ratio of subtended angles at the smallest and largest focal-lengths that a lens can focus at.

- If you so desired, you could pick an arbitrary projection frustum to represent the approximate behavior of a "human eye." We use this geometric tool in computer graphics all the time to help us solve the equations that define how large an object should appear on a computer-screen. Essentially, we "estimate" that your eye is the point of a frustum, and your computer-screen is the top "flat", and then we select an arbitrary bottom-"flat" to generate any geometry we choose. (You may consider that to define the "zoom" or "optical magnification factor").

- The common rule of thumb in photography is that the human eye "zoom geometry" is sort of like a 50 mm focal-length lens projecting onto 35 mm film. You'll find heated debates among photographers about whether this is anywhere close to the ballpark of the actual physiology of the human eye. Nimur (talk) 16:18, 23 July 2011 (UTC)

- Isnt this similar triangles? Something twice as far away has to be twice as tall to subtend the same angle. Therefore, moving something away twice the distance will half its apparant height, at least approximately. The OP appears not to have learnt trigonometry at school. This trigonometry calculator may be useful: http://www.carbidedepot.com/formulas-trigright.asp 92.28.245.233 (talk) 19:38, 23 July 2011 (UTC)

- Notice that because the area is inversely proportional to the square of distance, and the amount of light received is also, the apparent brightness of the object doesn't depend on its distance. (The size of the object from your perspective increases in the same way as the amount of its light that you soak up as seen from its perspective) So if you walk toward a yellow wall, it doesn't seem to get any brighter or dimmer as you approach. (Though if you look at a partial eclipse of the sun, the sliver remaining is just as bright as the normal sun, but your iris opens up because overall the sky seems dimmer, making it much more hazardous to the retina.) Wnt (talk) 03:12, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

Nice in Israel, baking in NYC

So it's a nice 86 °F (30 °C) here in this part of Israel (a subtropical part) and 84 °F (28.8888 °C) in Be'er Sheba in the Negev (most decidedly a desert). I look at the weather back home and see that in my beloved NYC, the temperature is 104 °F (40 °C) and in Central Jersey it is 120 °F (49 °C). So, here is my question, why is it that the subtropical region and the desert are so much cooler than the temperate area at about the same time of day? What's cooking here? Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie | Say Shalom! 12:01, 23 July 2011 (UTC)

- Because NYC (and much of the US) is presently under a record-setting heat wave exacerbated by high humidity. Note that NYC is characterized as having a humid subtropical climate, similar to the Mediterranean climate of coastal Israel. Beersheba is in a desert region, and so is more arid, but "desert" and "hot" don't have a causal relationship -- its climate is still semi-Mediterranean. So, based on your numbers, 86F is average for Tel Aviv and 84 is mildly below average for Beersheba. NYC, meanwhile, is setting record highs. This sort of discrepancy is actually quite common. — Lomn 12:26, 23 July 2011 (UTC)

- The subtropical area I am in, which is called the Western Galilee (guess I should have said the numbers for Nahariyya) is actually quite humid in some places, especially in our digsite, Tel Kabri, and we've never had anything nearly that bad. Why are we having this heatwave in NYC and the other less important places though? =p Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie | Say Shalom! 12:50, 23 July 2011 (UTC)

- Lots of news articles on the heat wave and its proximate causes are readily available. Here's one article on the heat wave itself and another on the terminology and scope of the system. Note that even outside of the heat wave we're seeing significant weather effects -- temperatures at my home are seasonally hot, but weather systems are presently moving east-to-west instead of the near-universal west-to-east pattern that prevails here. — Lomn 13:01, 23 July 2011 (UTC)

- Also, it sounds like the OP is making the common mistake of confusing "climate" with "weather". Merely because one region has a warmer climate than another doesn't mean that every minute of every day the cooler climate has to have temperatures which are lower than the warmer climate. There are going to be local variations on any given day that can make the weather hotter in some parts of the world than their average is, and colder in other parts of the world than their average is. While averaged over many decades, New York City may have a cooler, wetter climate than most of Israel that doesn't mean that for a few random days one summer New York City won't be much hotter than Israel. --Jayron32 16:42, 23 July 2011 (UTC)

NYC's climate is moderated by its position on the coast. Its current weather is caused by a strong stationary high over the eastern US. Note that even now, it is better to be in NYC than Brumfiss, the most miserable place in the world to spend a summer.μηδείς (talk) 16:57, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

- It didn't hit 120 in NJ as the OP mentioned. The max seems to have been 108 in Newark[1] and the heat index might have reached 120 but the state record high temperature of 110 was not broken as far as I can tell. Rmhermen (talk) 18:48, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

- A large, non-mountainous continental land mass nearby can exacerbate a heat wave, allowing air to warm rapidly over the dry areas and causing the heat wave to spread toward nearby coastal regions as well. The same happens for cold waves. ~AH1 (discuss!) 16:24, 25 July 2011 (UTC)

Dang it, how do I always miss the meteorology questions?? The answer is a bit complicated, but the simple answer is hinted at by AstroHurricane. The greatest solar heating occurs over large continental landmasses such as North America. Given the right weather conditions, New York can be downwind of a large stretch of solar heating, since it is firmly within the band of mid-latitude prevailing westerly winds. The same can happen in Israel. Both places are also next to an ocean: New York is by the Atlantic, Israel is next to the Mediterranean Sea, which is a warm sea, but water temperatures are still rarely much warmer than 90 °F (32 °C). This often serves as a moderating influence on temperatures there. So the simple answer is that the general weather pattern was a west-southwest wind in New York, which brought a large fetch of warm air in, while Israel was under a pattern of northwesterly wind, which brought in cooler air from the Mediterranean. However, given the right conditions, parts of Israel has the potential to get much warmer than New York City. You may also be interested in the urban heat island effect, which can exacerbate heat waves in large cities.

You should also note that just because a place is a desert does not make it any hotter. Sure, deserts are often hotter during the day than comparable areas which are less dry, but these areas are also often colder at night! This is due to dry air having a lower specific heat capacity than moist air]], which allows the same amount of energy input to increase the temperature by more, and vice versa.-RunningOnBrains(talk) 10:20, 27 July 2011 (UTC)

Watershed between rivers

I often find myself bicycling over a river bridge, and then many miles later going over the bridge of another river. In between the two rivers are streams, valleys, and hills, and contour lines all over the place. Is there any simple practical method of finding where I cross the watershed: ie the dividing line at which a drop of water will drain either into one river or the other? Might it be for example the highest elevation on my route? 92.28.254.185 (talk) 14:19, 23 July 2011 (UTC)

- It sounds like by "watershed" you mean drainage divide specifically (in the US "watershed" means the whole basin, not just its edge). Really every local maximum, however small, that you cross is a tiny watershed; these all shed water into one system or another, which eventually drain down either to the world ocean or to an endorheic system. Beyond that, it's kinda a matter of words about what constitutes a drainage system (usually a river) that you care about, and even with a single mountain, your scheme isn't sufficient. Imagine a plain with a single lonely mountain. Its north flank is drained by the river N and its south side by the river S. If N and S flow all the way to the sea without flowing together into a great river NS then we call the N and S systems basins in their own right; if N and S meet somewhere downstream of the mountain then the whole system is part of the NS basin (made up by the N and S basins, and by the area where water flows into the joined NS river). So, with you standing there on one part of the peak of the lonely mountain, you can tell a little bit, just from looking, where water falling on one side or the other will go, but unless you know where all the streams and river in the area flow, you can't know just from what you can see how a given droplet will finally get to the sea. So no, you need a topographic survey and (because water often goes underground) a hydrological survey too. -- Finlay McWalter ☻ Talk 14:46, 23 July 2011 (UTC)

I meant watershed, although you apparantly call it a "drainage divide" where you are. The difficulty you described was the point of my question. I fogot to add that I'm mainly interested in identifying it on a topographic map. 92.28.254.185 (talk) 15:33, 23 July 2011 (UTC)

- You basically want to identify the ridges. Visit this site and click on "Watershed/drainage basin delineation" for step by step instructions.--Shantavira|feed me 16:13, 23 July 2011 (UTC)

- Yes, the exact watershed (British usage) is not always easy to identify on the cycle route because the highest point is not necessarily the exact watershed. Sometimes the local contours around the highest point on the route mean that water from both sides of the highest point on the route can all flow to the same river. Near where I live is a meeting of three watersheds, where, in theory, a single raindrop could split into three, with some flowing into the Solway Firth (Scottish border), some into Morecambe Bay, and some out into the North Sea at the Humber Estuary. I have tried but failed to identify the exact point on the ground. Dbfirs 17:04, 23 July 2011 (UTC)

- With a very flat area, like a mesa, something as subtle as wind direction might change the actual point. Also, drifting sand dunes might change it in relatively short order, too. StuRat (talk) 17:38, 23 July 2011 (UTC)

- I would expect that the angle (syncline/anticline) and permeability of the underlying sediments should have some effect also. Wnt (talk) 22:19, 23 July 2011 (UTC)

- Can do if the folds are recent (Zagros fold and thrust belt for example) but older mountains (e.g. Snowdon as I recall} are often old synclines. Mikenorton (talk) 09:08, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

- In theory, at least, you could perform the watershed transform on the image that describes the terrain. --Martynas Patasius (talk) 17:43, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

Wholemeal starchy food

"If Americans could eliminate .... potatoes, white bread, pasta, white rice ... we would wipe out almost all the problems we have with weight and diabetes and other metabolic diseases" says http://www.latimes.com/health/la-he-carbs-20101220,0,5464425.story

Apart from wholemeal bread pasta and rice, and oats, are there any other wholemeal uncooked or semi-cooked starchy foods that are easily bought in supermarkets? 92.28.254.185 (talk) 15:45, 23 July 2011 (UTC)

- What else can you make using wholemeal? And type 2 diabetes is caused by people not having enough exercise and not eating properly. You can ignore small details like eating ordinary pasta/wholemeal pasta, if you are stuffing yourself with Big Macs and watch t.v. all day long. Count Iblis (talk) 16:08, 23 July 2011 (UTC)

- You can get sweet potatoes instead of white potatoes, and corn is easy to find in the "whole grain" form. Bread can also be found with all varieties of whole grains in it, beyond the common grains. However, to lose weight, I'd eliminate all white flour, yes, but also limit carbs in total, getting most calories from protein and vegetable fats (and a little alcohol). StuRat (talk) 17:42, 23 July 2011 (UTC)

- Its rather dangerous to give your own pet theory as gospel, particularly when no research backs it up. 2.97.210.203 (talk) 21:48, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

- Hardly "my pet theory". It's been extensively studied, see our article: Medical research related to low-carbohydrate diets. While we're only starting to get long-term results, they certainly aren't deadly diets, at least in the mild form I recommended: "limit carbs in total, getting most calories from protein and vegetable fats (and a little alcohol)". Perhaps eliminating all carbs might be dangerous, but that's not what I advocated. StuRat (talk) 03:56, 25 July 2011 (UTC)

- I struck the portion of the medical advice to which I thought people would most likely object. It's a really bad idea to make general statements like that. 99.2.148.119 (talk) 22:48, 23 July 2011 (UTC)

- And I unstruck it. Dietary advice is not medical advice. If it was, anyone writing a diet book would be required to have a medical degree. Thus, the rule about not editing the posts of others applies here. StuRat (talk) 06:10, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

- I'm a follower of the GL Diet, which limits the carbs you eat. Some of the foods I eat include bulgar wheat, couscous, quinoa (which I don't like so don't eat that much). I can eat potatoes as long as they are small and in their skins (such as Jersey Royal potato). Bananas are a no-no, as is pineapple, but I am encouraged to eat lots of berries. I could if I wished eat yams, cassava and sweet potatoes, but I'm not that adventurous (for an Englishwoman)! They are, however, all available in my local supermarket.--TammyMoet (talk) 17:55, 23 July 2011 (UTC)

- Sweet potatoes adventurous ? I didn't realize that they were so novel to Brits. I tend to look at calories versus nutrition. In that context, sweet potatoes are much better than white potatoes, and bananas and pineapple are also good choices. StuRat (talk) 18:20, 23 July 2011 (UTC)

- She is referring to yams and cassava also, not just sweet potatoes. 92.24.180.158 (talk) 23:24, 23 July 2011 (UTC)

- Yams, sweet potatoes and their ilk are widely avaialable in British urban supermarkets but are (I suspect) mostly bought by members of immigrant communities. I don't consider myself to be conservative food-wise, but I've never eaten (or been served) any, and have no idea how to prepare or cook them. Alansplodge (talk) 16:54, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

- Sweet potatoes are usually available at supermarkets in the UK - I eat them sometimes, but they are also too sweet for me. I've never eaten a yam or cassava, and are not available in mainstream supermarkets. 2.97.210.203 (talk) 21:39, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

- My younger compatriots think I'm a fuddy-duddy. I just find them too sweet and I'd rather have a nice King Edward potato, thank you. --TammyMoet (talk) 19:11, 23 July 2011 (UTC)

- I can see why you might find a sweet potato too sweet once covered in brown sugar, melted marshmallows, etc., but it's hard to see how a plain one would be too sweet for a Brit, considering how sweet you like your chocolate bars. StuRat (talk) 20:07, 23 July 2011 (UTC)

- Much as I like Kit-Kats I don't put them on the plate next to my roast beef and Yorkshire puddings! Context is everything! --TammyMoet (talk) 20:11, 23 July 2011 (UTC)

- So, to clarify, you consider sweet potatoes with nothing more than butter and cinnamon on them, to be too sweet ? (I'm talking about ones you buy in the produce section, not "candied yams" in a can.) Note that cinnamon, being rather bitter without the added sugar, tends to counter excessive sweetness. StuRat (talk) 20:24, 23 July 2011 (UTC)

- As far as I am aware American food has routinely much more sugar in it than British food. So what might not seem too sweet to an American can to a Briton. 92.28.245.233 (talk) 20:37, 23 July 2011 (UTC)

- Candied yams, if they exist in the UK and not sold in American food isles or something similar are unlikely to be sweet potatoes. And who the heck puts marshmallows or brown sugar on sweet potatoes? Nil Einne (talk) 21:02, 23 July 2011 (UTC)

- Lots of Americans do: [2]. While I'm aware that yams are not sweet potatoes, I wasn't sure if a Brit would know, hence the question. StuRat (talk) 21:08, 23 July 2011 (UTC)

- Yam in American English often means sweet potato, as is explained in the articles. So-called true yams, the ones from Africa, are not widely available in the States, but are more likely to be found in Britain, so actually they're more likely to make the distinction than we are. --Trovatore (talk) 21:13, 23 July 2011 (UTC)

- At least they are available in the US I presume. Unlike here in NZ where I've never seen any sort of true yam (only Oxalis tuberosa). Although looking now I find [3] which suggests they probably exist (unless the person is using some sort of powder or something) and various sources [4] [5] [6] suggest they were once cultivated by the Māori Nil Einne (talk) 21:31, 23 July 2011 (UTC)

- Yam in American English often means sweet potato, as is explained in the articles. So-called true yams, the ones from Africa, are not widely available in the States, but are more likely to be found in Britain, so actually they're more likely to make the distinction than we are. --Trovatore (talk) 21:13, 23 July 2011 (UTC)

- Lots of Americans do: [2]. While I'm aware that yams are not sweet potatoes, I wasn't sure if a Brit would know, hence the question. StuRat (talk) 21:08, 23 July 2011 (UTC)

- (ec) Well TammyMoet was discussing sweet potatoes (they did mention yams but as distinct from sweet potatoes) so it seems rather unlikely they were thinking of candied sweet potatoes sold as candied yams when they said sweet potatoes were too sweet. Nil Einne (talk) 21:16, 23 July 2011 (UTC)

- I'm just so baffled by how anyone can think sweet potatoes without added sugar are too sweet, that I'm grasping at straws trying to figure it out. I wonder if carrots, beets, and corn are also "too sweet" for Tammy. StuRat (talk) 21:44, 23 July 2011 (UTC)

- Other countries don't stuff so much sugar in their food as the US does, so thats probably the reason. 2.97.210.203 (talk) 21:46, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

- I can see how the sweetness could be distracting paired with certain meats, probably ones I don't eat anyway. Italians for sure wouldn't like that (try ordering lemon chicken in a Chinese restaurant in Rome, to see how the local culture influences the interpretation). It does seem a little incongruous coming from the country that invented boiled lamb with mint jelly, though. --Trovatore (talk) 21:50, 23 July 2011 (UTC)

- I add salt to my vegetables and not sugar. This is common in the UK. Carrots and sweetcorn are OK but beetroot are too sweet without vinegar. I'm used to eating lamb with mint sauce, which is made with mint, water and vinegar - not sugar! Never heard of candied yams or candied sweet potatoes! As I said earlier, some of my younger compatriots think I'm a fuddy-duddy. But I'm not alone. Maybe the American propensity to put sugar with everything is what is leading to their obesity epidemic (and the OP's comment, to bring this back on topic). --TammyMoet (talk) 07:37, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

- I'm just so baffled by how anyone can think sweet potatoes without added sugar are too sweet, that I'm grasping at straws trying to figure it out. I wonder if carrots, beets, and corn are also "too sweet" for Tammy. StuRat (talk) 21:44, 23 July 2011 (UTC)

- Yams (sweet potatoes) cooked with brown sugar and/or honey, and sometimes marshmallows, is a very common American dish at Thanksgiving and Christmas dinner. Personally I like everything except the marshmallows. No idea how the marshmallows got to be popular; to me they ruin the dish. --Trovatore (talk) 21:07, 23 July 2011 (UTC)

I suppose the quote above is another way of saying that you should eat low Glycemic index foods and not high GI foods. See also Insulin index. 92.28.245.233 (talk) 20:02, 23 July 2011 (UTC)

- Type 2 diabetes is likely caused by eating a high fat, low carb diet. Since low carb diets have become popular in the US more than 20 years ago, the obesity and diabetes rates have skyrocketed. People in the US seem to think that potatoes are not healthy while having no problems eating a huge steak for dinner. The last time I was in the US, I had difficulties getting normal foods in restaurants. One day I ordered a potatoes and steak dish, but what I got was a huge steak and just a few potatoes. When I asked for a lot more potatoes (a full plate), the (very obese) waiter said: "What? so many potatoes! That's not healthy!". Then what he brought was about half of what I normally eat, so I had to order again.

- Trying get a proper meal with bread for lunch is also quite difficult. A ham sandwich is not a piece of bread with some ham in it. What you get is a huge piece of ham with some sauce, covered by a paper thin piece of bread. The only way you can eat properly, is to go to some supermarket and buy bread yourself and then make your own lunch. I normally eat about 500 grams of bread per day and about 1 kg of potatoes. This is not a big amount at all if you exercise a lot and need to get more than 3000 Kcal per day.

- And then just walking on the streets and seeing so many obese people everywhere is very strange. Clearly, US citizens have indoctrinated themselves that the type of unhealthy diet they eat is healthy, and that healthy foods like potatoes, bread etc. are unhealthy. The higher the obesity rate gets, the more they stick to their idea of what is healthy, making the problem even worse. Count Iblis (talk) 16:19, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

- Your assertion at the start is doubtful. 2.97.210.203 (talk) 21:46, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

- I suspect you visited either NYC or Los Angeles, and ate at some "chic" restaurants, because the "bread and butter" restaurants here in the Midwest push bread like it's going out of style. Many restaurants bring unlimited bread with the meal, and fast food restaurants like Subway are happy to put your sandwich on an entire loaf of bread.

- There's also an obvious problem with the logic of saying that anything Americans do must cause (or at least must not prevent) obesity. For example, many Americans drink bottled water, but I see no reason why that would cause obesity. On the contrary, drinking lots of water, bottled or not, should actually help. StuRat (talk) 03:41, 25 July 2011 (UTC)

- Yes, New York and Toronto. It isn't much better in Canada. The US doctrine about diet does seem relevant to me. Another isses may be that people don't get enough exercise. What's also striking is the large numbers of obese children. And they eat what their parents give them to eat. Count Iblis (talk) 16:39, 25 July 2011 (UTC)

- Actually, one of the worst problems seems to be food provided by schools. Many of the schools are paid off by junk food makers and soft drink companies to sell unhealthy food in vending machines, etc. The food actually provided by school cafeterias tends to be unhealthy, too, such as chocolate milk instead of plain milk (the cacao isn't the issue, it's all the sugar added with it) and lots of fried foods, with veggies few and far between.

- There is no one "American diet". There are many different diets, based on geographic region, socio-economic class, ethnicity, age, etc. StuRat (talk) 17:16, 25 July 2011 (UTC)

July 24

The Brain and Exercise

It's time to exercise now that I'm home from vacation. After today's run I found it sort of tough to do addition of minutes and seconds (math isn't my strong suit in the first place, but it IS addition), followed by a distance/rate/time equation. I was wondering, is the latter caused by the former? Thanks Wikipedians! Schyler (one language) 01:37, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

- My experience is that thinking of all types is (unsurprisingly) more difficult when you're tired. I don't know of an article to point you to, though. --Trovatore (talk) 03:32, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

This study suggests the opposite; "(214 sixth-grade) students who either performed some or met Healthy People 2010 guidelines for vigorous activity had significantly higher grades than students who performed no vigorous activity in both semesters. Moderate physical activity did not affect grades." Also This study found that "Coordinative Exercise might lead to a pre-activation of parts of the brain which are also responsible for mediating functions like attention. Thus, our results support the request for more acute CE in schools, even in elite performance schools." However this one found that "review of the research demonstrates that there may be some short-term improvements of physical activity (such as on concentration) but that long-term improvement of academic achievement as a result of more vigorous physical activity is not well substantiated. The relationship between physical activity in children and academic outcomes requires further elucidation." Alansplodge (talk) 16:32, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

- My inclination is to think that the phenomenon that Schyler is asking about relates to the decrease in physiological arousal that results after running -- there is a principle known as the Yerkes–Dodson law stating that cognitive performance is best at intermediate levels of arousal, and drops off when arousal is either too low or too high. Looie496 (talk) 17:12, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

- My experience is that light aerobic exercise may indeed improve focus and concentration, but if you exercise hard enough to get seriously winded and keep it up for fifteen minutes or more, then it's kind of tough for a couple hours after that. Not sure how that relates to Looie's comments. --Trovatore (talk) 21:02, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

- And my experience is that if you do start to exercise more intensely for longer every day, you will sleep a bit longer and then this effect will go away. Count Iblis (talk) 16:05, 25 July 2011 (UTC)

- Well, I used to work at a startup that was only about eight miles from my house, so I commuted by bicycle. I also kept track of my average moving speed and tried to keep it as high as possible (I could usually average 15 mph, sometimes 16) and there was a particularly nasty spot where I had to turn left and sprint over a freeway overpass to keep from getting hit from behind. So I would arrive at work considerably out of breath. I'd cool down a bit and then change clothes. But my ability to concentrate on code was definitely impaired for at least half an hour. Never went away. --Trovatore (talk) 19:41, 25 July 2011 (UTC)

- And my experience is that if you do start to exercise more intensely for longer every day, you will sleep a bit longer and then this effect will go away. Count Iblis (talk) 16:05, 25 July 2011 (UTC)

- My experience is that light aerobic exercise may indeed improve focus and concentration, but if you exercise hard enough to get seriously winded and keep it up for fifteen minutes or more, then it's kind of tough for a couple hours after that. Not sure how that relates to Looie's comments. --Trovatore (talk) 21:02, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

material property

1)difference between strength and rigidity 2)how piston ring fit in the piston — Preceding unsigned comment added by Arpitmehta.mehta1 (talk • contribs) 05:22, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

- 1) If by "rigidity" you mean hardness, then I can answer. The harder materials tend to be fragile, like glass. Stronger materials must undergo either elastic deformation or plastic deformation to absorb an impact without breaking. But, of course, you don't want it to be so soft it breaks easily, so a moderate hardness typically provides the best strength. StuRat (talk) 06:03, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

- Have you read the piston ring article? If that does not answer your question then repost your question with more detail. Richard Avery (talk) 06:46, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

Irreducible complexity and vestiges organs

Just question out of sheer interest: If irreducible complexity is such a refuted concept, how come that there are organs in different organisms, which are acclaimed to be nonfunctional, to the level that they are not subjects to natural selection (e.g., appendicitis). Because in my understanding if one accept this, then he should expect that never non functional organs will be developed with time to become more complex functional organs-but nevertheless, I heard scientists in the field of evolution talking about Junk DNA as the sand box of evolution. Meaning that non functional organ or DNA sequence could serve according to them as the experiment lab of evolution instead of being washed out of the system though they are not protected by the pressures of natural selection (i.e., they have no value for the survival of the organism and can therefore be washed out very easily).--Gilisa (talk) 08:17, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

- There are a couple of answers here.

- One is that many doctors believe that the appendix has some small useful value to offset it's small risk of infection. (It may provide a resevoir of "gut flora" in case something happens to the gut flora in our actual gut.) The Vermiform appendix article covers this briefly.

- Another answer is that evolution is a work in progress. You can't look at modern humans as if we're the end-product of evolution. If the appendix is truly vestigal evolution will probably fix it eventually, but it may take a very long time. Appendix problems stop only a very small number of humans from breeding, so it's not the sort of change that will get selected for quickly.

- (And if it happens, Hundreds of thousands of years from now, the change might not be what you expect. Instead of simply eliminating the appendix, it may mutate into something useful.)

- APL (talk) 08:46, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

- Gilisa - I think you have the argument back-to-front. The existence of vestigial organs, junk DNA and other instances of non-optimal design such as the recurrent laryngeal nerve in giraffes are usually taken to be evidence in favour of evolution and against "intelligent design". Evolutionary forces select for characteristics that improve the survivability of a species, but there is no pressure to eliminate redundant or outdated characteristics if they carry no significant cost or downside. On the other hand, it is difficult to understand why an "intelligent designer", designing an organism from scratch, would give it such useless features (unless we head into "it's all a test of faith" territory). Gandalf61 (talk) 08:48, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

- (ec)What does irreducible complexity have to do with this? Irreducible complexity is a very particular argument that claims that a system that is "irreducibly complex" cannot evolve via natural selection, since it cannot evolve part-by-part because the individual parts have no function and hence provide no evolutionary advantage. That latter assumption, is, of course, generally wrong - irreducibly complex systems can indeed evolve by re-purposing parts that had other than the final functions (and we see evidence of this all the time). Do you mean to talk about (so-called) intelligent design in general? As for the rest of your argument, I'm not sure you understand the domain well enough. Junk DNA has nothing to do with vestigial organs, wich are build using the same coding methods as perfectly functional organs. Junk DNA is called that because it does not code for particular amino acids. Some junk DNA is anything but junk, because it provides important regulatory functions. For other parts of junk DNA we do not know any function (and it may not have any current function). For these parts, many mutations are neutral. On the other hand, some mutations can turn non-coding parts into coding parts, or enhance or reduce the expression of certain genes, leading to very drastic (and often detrimental) effects on the organism. --Stephan Schulz (talk) 08:58, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

- I'm unconvinced that the vermiform appendix is truly a vestige. Consider that some people don't have an appendix.[7] If appendicitis would truly impose an extra 0.1%-1% death rate on those having it, without some corresponding benefit, I'd expect that the people who lack one would "rapidly" (I don't know enough about the genetics of appendices to play with the Price equation, but I would assume something at nearly the same order of magnitude as the selective force, within some few thousands of generations, much younger than the human race). Wnt (talk) 10:47, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

- Well, a few thousand generations, at 20-30 years per generation, is a significant part of at least the existence of Homo sapiens. --Stephan Schulz (talk) 10:53, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

- WNT, some people are born with one kidney instead of two, some people are being born without visible Corpus callosum and yet no one argues it have no important function. Though indeed many times your reasoning does work. Stephan Schulz, I know what junk DNA is and I'm familiar with single mutations that can lead microsatellites to become coded sequences (though the code would not yield protein as end product). But my question didn't have much to do with that. If there are DNA sequences that have no apparent function then we can see them as junk at the moment. As they are very far from becoming regulating sequences or coding sequences you can't even say that organism who carry much of them have some kind of survival advantage in the case of rapid ecological change that demand rapid adjustment-because they are very far from having any function that would be promoted by selective pressure. So in essence, their existence -as well as the existence of vestiges, give some strength to the idea of irreducible complexity because if you still find them in the organism after so much time have passed since they had any function, you must assume that with time this vestiges-regardless if they are in the molecular level or at higher level (actually, it's the same) will become to be functional some day but yet you know that during their development there were stages in which they were not functional. This of course in line with the idea of irreducible complexity that more than one step is needed at a time to make system to a more complex functioning system. Isn't it?--Gilisa (talk) 11:25, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

- You're confused. The proponents of irreducible complexity assumed that it couldn't happen, so finding instances in which it does happen goes against their view of the world. Dauto (talk) 17:49, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

- Note that a vestigial trait doesn't have to be completely non functional. See our own article linked above or [8] for specific discussion of the appendix Nil Einne (talk) 19:37, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

- I would guess that the appendix has some value, but not much, and that this balances the slight risk it poses, so that it's at an evolutionary equilibrium. For another example, how about toenails ? They can become ingrown and get infected, and thus cause blood poisoning, but this isn't very common and whatever positive value they provide probably balances this risk. StuRat (talk) 03:28, 25 July 2011 (UTC)

- OK. I think i got your question. Are there biological systems (organs/genes/metabolic pathways etc.) that cannot have arisen without passing through some non functional /less fit intermediates? Yes. can this be called Irreducible complexity? I say yes. But is this a serious objection to modern evolutionary theory? I say no. that's why (as you put it) irreducible complexity is such a refuted concept as an argument for ID. The reason for this is non-functional intermediates can escape selective pressure for short periods of time (when there is gene duplication OR when the environment changes like during the colonisation of a new island were there is no competition OR it becomes vestigial OR even diploidy OR alternative splicing) biological systems evolve upto a point performing some function, then when the pressure is relaxed, they wander around between nopnfunctional neutral states till most of them are lost by chance. Some though discover new skills and start evolving in a new direction under selective pressure once more. The crux of the argument between ID and evolution in this context is whether the amount of wandering among neutral states required makes its emergence by chance likely or not Staticd (talk) 07:27, 25 July 2011 (UTC)

What to do with wreck after train crash?

The morning after the 2011 Wenzhou train collision, the train wreck was turned, crushed, and buried by diggers. video starts at 1:18 photo I would've thought they would want to keep the wreck around for a while as evidence in the investigation. Is it suspicious to destroy the train so soon after the accident? thanks F (talk) 12:22, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

- Why bury it at all? It would make more sense to recycle it. Agreed, I think they are attempting to hide something. Plasmic Physics (talk) 15:08, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

- Ever since the Sichuan schools corruption scandal there has been harsh criticism of Communist Party officials and corrupt practices. Looks like what they are doing here is trying to cut this off at the knees before it becomes another scandal. They fire a few scapegoats, bury the evidence, and move on. If this had happened in pretty much any other major industrialized country there would be a more thorough investigation, but this event appears to have been "politicized" rather quickly. Beeblebrox (talk) 15:19, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

- They are simply hiding evidence of wrongoing, negligence, etc. This is typical of an authoritarian government which does not wish to be accountable to its citizens. — Preceding unsigned comment added by 72.94.61.91 (talk) 17:01, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

- In a US trainwreck, depending on the degree of damage to the rolling stock, some cars would be put back on the rails and towed away, with necessary repairs to the wheels and the parts connecting them to the cars. A salvage crane on a railroad car would be able to lift the heaviest car (250 ton capacity was typical in the 1950's). Flatcars on the repair train carry spare rails and undergear (the trucks on which wheels are mounted on conventional rail cars). A car can be back on the rails with new trucks in 20 minutes, if not too badly distorted. Damage rails are sometime replaced while the car is lifted in the air by the crane. Mangled cars would be pushed aside to be removed later. Even back in the 1920's, a railroad could have a wreck clearing train rolling to the site in a half hour which was capable of removing wreckage and repairing the rails for traffic in three hours. At the railroad shops, some parts would be recovered for reuse, and cars damaged beyond repair would be sold for scrap, which could be a significant amount of money, given copper in the motors, and aluminum, stainless steel and other highly valuable metals. Crushing and burial on site is very odd. I suppose locals will then proceed to dig into the mess, cut up the wreckage and sell it as scrap metal. If the Chines high speed rail company did not own a repair train with a crane, one might ask why the hell not?Edison (talk) 18:44, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

- I'm sure they do own one, they just decided to sweep this incident under the rug as quickly as possible. I also doubt a U.S. passenger train crash would be dealt with in the cut-and-dried manner you describe, the NTSB will usually spend many months analyzing the debris. I imagine procedures have changed a bit in the 54 years since the article you cite was written. (step one: rig a field telephone is pretty dated) Beeblebrox (talk) 18:55, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

- So you report back on a celphone or railroad radio rather than a field phone. You still have "established telephonic communication." You can request additional personnel or additional materials. You fix the rails, set the wreckage on railway trucks (get on wheels that will roll along the repaired tracks) and get it back to the shops, where it can go into a guarded storage area for forensic examination. In those 1920's to 1950's accounts, the prompt dispatch of a repair train, in a half hour, along with medical personnel if it was a passenger train, is probably about as quick as would be accomplished today, or maybe quicker, with the personnel cuts and maintenance budget cuts by railroads. Does it seem likely that a repair train is rolling quicker now than then? When a train wrecked, along with getting the track back in operation, and getting the rolling stock back to the shops, they sought to investigate the cause. See [9]. Sometimes, someone with a grudge had pulled up spikes and mover rails to cause a derailment. In other cases, brakes failed, as proved by testing of the relevant parts of the braking system during the investigation, or the engineer was speeding, as shown by the speed recorder. Crushing and burying all the equipment sounds like it might be a coverup in more ways than one. The NTSB might investigate for months, but I do not believe that they leave the wreckage in place and the line out of operation for months. This is not an airplane that crashed in a cornfield, leaving some metal fragments and bits of flesh with a crater in the ground. Edison (talk) 19:09, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

- I'm sure they do own one, they just decided to sweep this incident under the rug as quickly as possible. I also doubt a U.S. passenger train crash would be dealt with in the cut-and-dried manner you describe, the NTSB will usually spend many months analyzing the debris. I imagine procedures have changed a bit in the 54 years since the article you cite was written. (step one: rig a field telephone is pretty dated) Beeblebrox (talk) 18:55, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

- If one wanted to Assume Good Faith, one could hypothesize that all they seem to be dealing with in the video is the passenger cars -- which seem almost completely trashed. I would doubt there's much to be learned from them, even if there is minor value in salvaging the seats or recycling the bare metal.

- Any significant failure analysis would most probably be done on the traction units, which is also where any electronic "black boxes" (if there were any) would be, right? We don't see those being buried, ergo we cannot be sure they have not ALREADY been removed for analysis, yes?

- Note I make no claim as to whether this hypothesis has actual value -- I have no more data on the human motives than I do on the locomotives. DaHorsesMouth (talk) 22:28, 25 July 2011 (UTC)

- I wouldn't describe the salvage value of the cars as "minor". A back-of-the-envelope calculation says those cars are worth $25,000 to $50,000 in scrap metal alone. --Carnildo (talk) 00:44, 27 July 2011 (UTC)

- In the old US accounts I found, I was impressed with how quickly they conjured up ramps and temporary track to pull the fallen equipment back up onto the railway line for hauling away. The Chinese authorities got their line back in operation pretty quickly as well, but abandoned the cars to metal scavengers. They claimed they buried it "to protect Chinese high speed railway technology," which sounds silly. Seems odd that a train can suffer a loss of power, supposedly from lightning, and passengers can message their friends up to the point of crash, but the following train gets no message to let them know the train ahead is stopped. No GPS transmission to railway control? No block signals (early 20th century technology which tells the following train there is a stopped train ahead in plenty of time to stop). When accidents like this happened in the US or the UK, in the 20th century, it was always puzzling that an engineer would drive at high speed right through a couple of block signals which should have initiated a stop. There have been US collisions recently where the engineer (engine driver) was texting to some "rail fan" and ignoring his job. In some US mass transit operations, the signals automatically stop a train when the engineer doesn't in such a case. Edison (talk) 04:18, 27 July 2011 (UTC)

Crazy gasoline additive

Hi, i have heard a crazy claim that you can significantly increase the volumetric heat content of gasoline by dissolving a lot of sugar in it. That seems possible since sugar can dissolve in large quantities with only slight changes in volume, but wouldn't this totall gunk up and screw up your car? 209.90.190.147 (talk) 16:27, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

- This seems to be an interesting and unique variation of the urban legend that you can disable a car by putting sugar in the gas tank. Sugar isn't soluble in gasoline (or other non-polar liquids); if you pour granulated sugar into the fuel, it will just settle to the bottom of the tank. According to Mythbusters, sugar granules don't affect vehicle performance, probably because they won't get past the fuel filter (if they get carried by fuel flow out of the tank at all). In principle a large amount of sugar could clog the fuel line just by physically plugging it up. See also Snopes, which notes that the solubility of sugar in gasoline is less than a teaspoon (a few grams) per tank. TenOfAllTrades(talk) 16:53, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

- I suspect that someone is trying to get you to perform an old prank on yourself.

- It's not likely to screw up your engine, because it won't get there. But this [Straight Dope Article] suggests that it may clog your fuel filter and possibly screw up the fuel pump. APL (talk) 20:32, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

- The moral of the story is that solubility depends on the solvent: sugar dissolves very well indeed in water, because it is sort of a bunch of water molecules (H - OH) with a line of carbons running down the middle to hold them all together. But just as water doesn't dissolve in gasoline, neither does sugar.

- In terms of energy, sugar already contains those oxygens I mentioned, so it has less energy when combined with oxygen than gasoline, which is largely carbon and hydrogen. Just as fat has more than twice the calories of sugar, so does gasoline - and it's your car's favorite food to boot. Wnt (talk) 19:03, 26 July 2011 (UTC)

mutation

a few days ago i saw a video of some person (Rabbi Shmuley Boteach) saying that mutations are not successful in 99 percent of the cases (and therefore evolution is driven by god or something) is that true? if it is, does it make evolution unlikely, magic, etc. ?--Irrational number (talk) 17:27, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

- Read this and let us know if you have any questions. This is a common Creationist argument that is very flawed. --Mr.98 (talk) 17:33, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

- Even without reading the link, can you spot the error in the logic? If mutations are unsuccessful 99 percent of the time than that means 1% of the time they are successful. Even if they are not successful 99.999% of the time 0.001% of the time they are successful, given an arbitrarily high enough number of mutations, you end up with enough successful mutations to drive evolution, regardless of the probability. Mutations would need to be unsuccessful 100% of the time to not be a factor in evolution. Of course if you play with the numbers and assume the earth is 6000 years old and that mutations only occur once every 100 years or something ridiculous like that you could say "the numbers are against evolution" or some such. --TimL (talk) 18:06, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

- That's all correct in principle, but at a practical level there actually is a problem if the rate of harmful mutations is too high -- it is hard to avoid a steady accumulation of deleterious mutations, analogous to Muller's ratchet. The value that I have seen most commonly quoted is a bit smaller, though -- something like 98% of non-neutral mutations being deleterious. And that really only applies to exons -- the probability of a mutation to non-coding regions being deleterious must be a lot lower, although I'm not aware of any actual estimates having been published. Looie496 (talk) 18:39, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

thanks.problem solved.--Irrational number (talk) 19:02, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

- That's also why sexual reproduction is such an important thing. It allows for a much more efficient removal of deleterious mutations. Dauto (talk) 19:21, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

- Isn't the concept of biodiversity useful here? It is essential to have mutations from time to time. Most of them matter not at all any way. Some are definitely useful to the individual organism and/or to the species. Some are definitely not useful. The remainder are useful in some circumstances, e.g. the gene that causes sickle cell anaemia but also protects against malaria. Itsmejudith (talk) 21:34, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

- The basic claim is flawed. It is just not true that 99% of mutations are "not successful". Most mutations have no noticeable effect at all. --Srleffler (talk) 04:46, 26 July 2011 (UTC)

- The claim isn't so much flawed as sloppily stated. Neutral mutations are essentially irrelevant -- it seems to be broadly accepted that for exon mutations that affect the way a protein folds, the majority are harmful to its function. How large that majority is thought to be varies, but I have seen values as high as 98% quoted. Looie496 (talk) 05:28, 26 July 2011 (UTC)

- The 99% figure is, well, one of the 90% of statistics that are made up. If we look at actual figures for the ratio of synonymous mutations to non-synonymous mutations, it is very rarely so extreme - a lot of mutations slip through. The reason, as stated by Fisher, is that if a mutation is small enough there are about equal odds that it will be beneficial or detrimental. Picture an archer shooting at a target: if you grab his arm and pull, you're sure to do harm to his aim, but the faintest jigglings of the wind might as likely push his arrow to the center as away from it. This is why Hopeful monsters have been largely deprecated - though I'd say luck can never be ruled out in evolution. Bottom line: for the usual gene which is not extremely well conserved (not histones!), where single base pair mutations in the sequence aren't a big deal, many more than 1% of mutations will be successful. Note however that the organisms carrying this mutation can still die at random, and many such mutations will be wiped out simply by genetic drift. Wnt (talk) 18:52, 26 July 2011 (UTC)

- The claim isn't so much flawed as sloppily stated. Neutral mutations are essentially irrelevant -- it seems to be broadly accepted that for exon mutations that affect the way a protein folds, the majority are harmful to its function. How large that majority is thought to be varies, but I have seen values as high as 98% quoted. Looie496 (talk) 05:28, 26 July 2011 (UTC)

I was impressed recently to see two dinghys passing each other in a narrow river, going in opposite directions. How nearly can dingys be sailed in 360 degrees from the wind without tacking? 2.97.210.203 (talk) 22:14, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

- They can sail pretty easily perpendicular to the wind, and even into it slightly without much problem.

- The keel of the boat keeps it traveling in roughly the direction it's pointed in.

- (For example, if the wind was from the north, then the two dinghies could be sailed East and West without any special effort.) APL (talk) 22:35, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

Time cloaking?

I'm lost - can anyone explain this to me? - from whom is the time cloaked? how is it done? if time is cloaked, isn't the time 'surrounding' the contracted by the excision of the nanosecond or whatever? - please explain to this complete idiot

Adambrowne666 (talk) 22:49, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

- Sending a light beam that makes a step change in frequency through an optical material that gives a different delay to each frequency is a way to make a flashlight (UK: torch) whose beam is briefly interrupted. If that is your only light source, you will not see anything that happens during that little "off" interval. It's a very short interval and "time cloak" is a silly name for something so trivial. Vision being interrupted is not the same as time being excised. Cuddlyable3 (talk) 23:12, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

- Thanks, Cuddlyable - that's a good answer. Adambrowne666 (talk) 01:09, 25 July 2011 (UTC)

- Even so, I wonder if there is a way to use this as a sort of "box" (as in Schroedinger's cat) to cause strange quantum effects... Wnt (talk) 18:56, 26 July 2011 (UTC)

Speaking of sailing

How can a sailboat sail "into the wind". It seems counterintuitive to me. I know they tack left and right, never actually sailing directly into the wind, but net they are, and it seems like cheating physics somehow. Why can't canoes do something similar with regards to current, can the same principles be used to make a canoe that will flow upstream? (assume for the sake of this example the water is flowing for some reason other than due to gravity, i.e I'm not asking it to go uphill, just "into the current"). --TimL (talk) 22:57, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

- The canoe would be difficult. In a sailboat, the keel and rudder of the boat pushes against the water, which helps move the boat in the direction you want to go, and not strictly the direction the wind is pushing it. I'm not sure what your hypothetical river-powered canoe would be able to push against. I guess you could probably build a zig-zag rail for it to run along, then if you oriented it properly and used a rudder you could probably get the current to push the canoe upstream along the rail.

- (The other option would be to make some sort of "air keel" out of a gigantic sail, but the tiniest breeze would ruin that plan.) APL (talk) 23:08, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

- The article Tacking (sailing) explains how it works. Cuddlyable3 (talk) 23:15, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

- Yes I've read that article. It explains how it works, it doesn't explain why it works. --TimL (talk) 23:34, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

- You can probably "easily" build a boat with side-wheels driven by the current that pulls itself upriver on a rope. --Stephan Schulz (talk) 23:18, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

- That would actually be a really neat trick. You'd have a boat that could go up and down river for "free". All you'd need would be a way to engage or disengage the mechanism when you wanted to switch directions. I wonder if anyone's done this. APL (talk) 01:55, 25 July 2011 (UTC)

- The article Tacking (sailing) explains how it works. Cuddlyable3 (talk) 23:15, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

- (edit conflict) I'm trying to understand the basic physics of this. I guess it's kind of like if you let a ball hit you (let's assume this is completely inelastic collision), and than you catch the ball on it's way away from you. When it hits you, you are pushing against the floor, but when you catch it you say somehow, let yourself slide, enough of these interactions and balls heading toward you allow forward motion into the balls. That makes sense except for the pushing against the floor when getting hit, but not when catching the ball. You'd have to jump, (but only a little if you had really good timing and dexterity) -TimL (talk) 23:47, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

- We actually have an article called Sailing into the wind. After reading it once, i'm not sure I totally understand it, but I think the explanation is there. Vespine (talk) 23:49, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

- Thanks. I found this image immensely helpful. But still don't quite have the whole picture. Getting closer. --TimL (talk) 00:11, 25 July 2011 (UTC)

- We actually have an article called Sailing into the wind. After reading it once, i'm not sure I totally understand it, but I think the explanation is there. Vespine (talk) 23:49, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

In a canoe or kayak, you can ferry glide; a technique where the downstream current is used to push the boat sideways across the river[10] - you still have to paddle hard upstream to make it work though. I think we can safely assume that were there any conceivable way of taking a canoe upstream without a considerable expenditure of effort, someone would have discovered it by now. Alansplodge (talk) 00:25, 25 July 2011 (UTC)

- Note that you can cross the river without ant paddling using an unpowered cable ferry. Given that it's infinitely improbably that the cable is exactly perpendicular to the current, you will move somewhat upstream on one of the legs. Now imagine a zig-zag of cables, and you can (in theory) ferry upstream by switching ropes. It's not exactly practical, but it is possible. --Stephan Schulz (talk) 08:28, 25 July 2011 (UTC)

- The wind pushes the sail which is placed at an angle so that the wind pushes the boat sideways. The keel is also placed at an angle so that it also pushes the water sideways and the water, by Newton's 3rd law pushes back. Sideways of sideways can end up being against the wind. Dauto (talk) 02:22, 25 July 2011 (UTC)

At some point, if you studied physics, you learned the conceptual relationship between force and potential energy. It would appear, at face value, that sailing into the wind, against the force, moves the boat against the gradient of potential energy - i.e., the boat is gaining energy by sailing against the wind! This perpetual motion machine is easily explained away: wind and water forces are nonconservative forces and cannot be described in a straightforward way as a potential energy gradient. The boat is using the force of wind to do work, and in doing so, is wasting energy on turbulently moving air around, as well as engaging a contact force between the boat keel and the laminar flow of water. The entire process is very thermodynamically inefficient, aside from the fact that the wind costs nothing to harness. But, the net work, done in moving the boat upwind is FAR less than the total work exerted by the wind, on the sail. If you think of it this way, instead of (incorrectly) imagining the wind force field as the gradient of a conservative potential energy field, you will see the conundrum vanishes. Energy is supplied because each parcel of wind is imparting a net force acting over a net distance relative to each parcel of the wind - not relative to the net motion of the wind. (In fluid mechanics, we can have individual air molecules moving in different directions! To formally analyze the flow, we use continuity equations, which are not easily represented as conservative potential energy fields). Once you have extracted energy from the wind, you can convert it to kinetic energy for the boat; and the boat takes advantage of fluid resistance (using its keel, its rudder, and the design of the hull) to steer its motion into almost any direction it wants. Nimur (talk) 15:01, 25 July 2011 (UTC)

- Is turbulence rather than laminar flow an essential feature of tacking? Cuddlyable3 (talk) 18:10, 25 July 2011 (UTC)

- All interactions between a sail and the wind will involve turbulence. Sails are not meant to be streamlined, they're intended to have a large cross-sectional area, because they are designed for the wind to impart a force to them. Because turbulent airflow is involved, analysis of the force and power imparted by the wind becomes nontrivial. Nimur (talk) 20:21, 25 July 2011 (UTC)

A simplistic explanation from a lifelong sailor with a basic knowledge of fluid dynamics: When sailing into the wind, sails act like a wing. The passage of air over the convex curve of the sail and the accumulation of high pressure turbulent air at the concave surface produces lift which pulls the yacht perpendicular to the plane of orientation of the sail. This same force also causes the yacht to lean over, or heel. The keel opposes the force causing the boat to heel, preventing the boat from capsizing; and also converts the perpendicular force into forward motion. The conversion of lift to forward motion is never perfect and all yachts experience different amounts of leeward drift, depending on the characteristics of the hull, keel, and sail pattern, as well as the point of sailing (ie how close to the wind you're sailing). At least that's how I understand it! Cheers, Mattopaedia Say G'Day! 11:41, 27 July 2011 (UTC)

Swelling of hands and feet

Any shoe seller will tell you to buy your shoes at the time of day you intend to wear them. Feet get larger (more swollen) over the course of a day even in healthy people with no medical problems. Rings that fit nicely in the morning are often snug by nightfall. And summer's heat will often make the swelling worse. What is the physiological explanation? Bielle (talk) 23:40, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

- One is the difference in pooling of blood due to an upright posture. The puffiness in your face in the morning settles into your legs by lunchtime. There's also edema, which would be the name for the condition at a clinical level due to some abnormal return of lymph. See blood pressure, lymphatic system, edema. μηδείς (talk) 23:44, 24 July 2011 (UTC)

- The puffiness in your face in the morning settles into your legs by lunchtime .beautiful description. Staticd (talk) 06:44, 25 July 2011 (UTC)

- I think that the lymph/interstitial fluid pooling is more important than that of the blood.Staticd (talk) 06:44, 25 July 2011 (UTC)

- Feet also get slowly bigger as you age, as do ears. 2.101.4.222 (talk) 08:45, 25 July 2011 (UTC)

- The statement above that this phenomenon is primarily due to pooling of blood is erroneous - the swelling described by the OP is largely due to increases in interstitial fluid (fluid between cells, but not in blood) in dependent tissues. Our edema article (cited in the same "answer" above has quite a bit of relevant information on this topic; in particular, the Mechanism section there discusses the multiple factors that affect the quantity of interstitial fluid in tissues. That this is not related to pooling of blood is the slow shifts (over hours) that occur with changes in position (pooling of blood, to the extent it might occur in dependent tissue, would be reversed in seconds with change in position). -- Scray (talk) 02:23, 27 July 2011 (UTC)

- Well, I guess I should have pointed out that I meant to include lymph by saying "blood" above, and did indeed explicitly mention lymph, but figured it wasn't important given Staticd's statement. I figured he had cleared up any confusion. My bad. But now that I have been corrected twice, yes, let me point out that I didn't mean to imply that as with a corpse, one can expect pooling of blood in the cheeks of a person who sleeps in the prone position. And no, that blood that's not pooled in your cheeks doesn't settle in some special leg cavities as the sun approaches zenith. Unfortunate that I didn't provide links to lymphatic system or edema, then my response would actually have been helpful. And I hope I didn't give the impression that blood and lymph are made of the same thing or flow through the same system. I mean, God help us, please, can't somebody think of the children? μηδείς (talk) 02:48, 27 July 2011 (UTC)

July 25

Line of cooling, line of heating

Is there any map of the USA which shows a line to the north of which you do not require air conditioning in the summer, and to the south you do? And similarly is there a map with a line to the south of which you do not require winter heating? 2.101.4.222 (talk) 09:05, 25 July 2011 (UTC)

- What temperatures would "require" air conditioning or heating? I have no air conditioning while the guy I work with has it. If I had to guess, I'd say more people around me don't have air conditioning than do. So, would this requirement line be north of me or south? I would suspect that if you were to draw a vertical line on a map and then poll the households along that line, there would be a gradient for both heating and cooling that is more or less a smooth decline or accumulation depending on which way you go up or down that line. You will at some point reach 0% of homes that has either heating or cooling. So would this be your line of requirement? 0%? Dismas|(talk) 09:31, 25 July 2011 (UTC)

- 50% of households would be an appropriate line. 2.101.4.222 (talk) 09:44, 25 July 2011 (UTC)

- That's an iffy way to try to collect that data. While air conditioning is very pleasant to have in warm climates, it's not essential for most individuals the way that home heating is. (In the sense of 'your water pipes will freeze solid, then you will die of hypothermia'.) The "50% air conditioned" line will be skewed very heavily by demographics—regions with lower household incomes will be less air-conditioned than higher-income regions. You'll probably also see significant rural-suburban-urban splits. (Dismas' suggestion to look for a 0% air-conditioner penetrance is interesting, but would probably rule out the entire United States. As of 2002, something like 30% of households in Canada had an air conditioner, and that number was steadily trending upwards.)

- What you're probably looking for is something like a map of heating degree days (and cooling degree days). That article has both maps for the United States, and a pretty good explanation of what the numbers represent. TenOfAllTrades(talk) 13:50, 25 July 2011 (UTC)

- Many homes in the Southeastern United States do not have central heating, even though temperatures occasionally fall below freezing. You could even say the line is variable between different years. ~AH1 (discuss!) 15:51, 25 July 2011 (UTC)

- Climate on a large continent is not that simple. For example, I live on a state that borders Canada, and it was 102 degrees Fahrenheit last week. I certainly wouldn't want to live here without air conditioning. Washington state, at the same latitude, rarely gets that hot on the coasts, but does inland. So you wouldn't end up with a straight line. thx1138 (talk) 16:32, 25 July 2011 (UTC)

Better US climate than London

Most of the US, compared to Britain, gets extremely hot in the summer, and extremely cold in the winter. By comparison the average winter temperature in London is above freezing with hardly any snow, and only during infrequent summer heat waves would you appreciate air-conditioning in the home. Nor does it rain much (contrary to US stereotypes) with around 20 inches of precipitation a year.

Which places in the US have a better climate than London? 2.101.4.222 (talk) 09:13, 25 July 2011 (UTC)

- Could you better define "better"? I quite like where I live and we regularly get a few feet of snow each winter. To me, that's better than London. But it seems as though you're looking for a place where the temperature range isn't very wide and where there is very little precipitation. Am I right? Dismas|(talk) 09:23, 25 July 2011 (UTC)

- Principally where it is not extremely hot in summer or extremely cold in winter, and preferably with around 20 inches or less of precipitation. 2.101.4.222 (talk) 09:43, 25 July 2011 (UTC)

- Again, you'll have to better explain what you mean by "extremely". My niece in Georgia would likely tell me that anything below 20F is extremely cold while I don't mind these temperatures. Moving along though... Well, I don't have a map with a pin in it for you but can provide some links to maps so that you can figure it out on your own... This pdf shows the average rainfall in 2001 as well as average temperature but unfortunately not the range. NOAA has a collection of maps that are relevant. As well as How Stuff Works. This site seems very handy as well. Dismas|(talk) 09:54, 25 July 2011 (UTC)

- Principally where it is not extremely hot in summer or extremely cold in winter, and preferably with around 20 inches or less of precipitation. 2.101.4.222 (talk) 09:43, 25 July 2011 (UTC)

- Honolulu may be a bit too warm for you, but it never gets unbearably hot. And you can fine-tune average rain fall to your liking by picking the right place between the mountains and the sea. --Wrongfilter (talk) 10:35, 25 July 2011 (UTC)

- San Diego has a reputation for an extraordinarily equable climate. See the article Climate of San Diego. Deor (talk) 12:08, 25 July 2011 (UTC)

- You might also try Seattle, which does not frequently get much snow compared to higher elevations, though there is an inherent earthquake risk. ~AH1 (discuss!) 15:48, 25 July 2011 (UTC)

- Drawback to Seattle is it gets around 40 inches of rain a year compared to 20-25 for London, but they do appear broadly similar. Googlemeister (talk) 15:56, 25 July 2011 (UTC)

- You might also try Seattle, which does not frequently get much snow compared to higher elevations, though there is an inherent earthquake risk. ~AH1 (discuss!) 15:48, 25 July 2011 (UTC)

- San Francisco? --Jayron32 16:04, 25 July 2011 (UTC)

- Yes, and neighboring parts of California. Los Angeles and San Diego also have nice parts, but if you get more than a mile or so from the beach they are pretty hot. Looie496 (talk) 21:20, 25 July 2011 (UTC)

- The inquirer apparently means a mild climate, which means on the coast. NYC, Long Island and Cape Cod are not bad. I personally prefer a winter where it is cold enough to ice skate and a summer warm enough to swim in the ocean without shivering. Most articles on cities give their mean monthly temperatures. μηδείς (talk) 01:11, 26 July 2011 (UTC)

Phase diagrams

Does anyone know where to find phase diagrams for phosphorus and sulfur, including the allotropes and molecular species present? At what temperature does octathiocane autoignite, does it burst into flame before it melts? Plasmic Physics (talk) 09:58, 25 July 2011 (UTC)

- I have the phase map for sulfur it could be found here just before "4 phases at the extremes"--Irrational number (talk) 14:38, 25 July 2011 (UTC)

- I typically do an image search on "critical point" and the name of the substance for phase diagrams. Octathiocane says it decomposes at 115 Celsius. 99.2.148.119 (talk) 19:13, 25 July 2011 (UTC)

- For sulfur there is a German phase diagram available on commons. I was converting it to .svg form, but the quality was so low that I abandoned the attempt. It is actually much more complex as at higher temperatures there are mixtures of molecules, including trisulfur and other allotropes of sulfur such as S6 and S2 in the gas. What is there depends on the thermal history of the mix. There is a chart for Phosphorus but not a phase diagram here. Graeme Bartlett (talk) 10:22, 26 July 2011 (UTC)