Guatemala: Difference between revisions

| Line 256: | Line 256: | ||

{{Pie chart |

{{Pie chart |

||

|thumb = right |

|thumb = right |

||

</big> |

</big> |

||

|label1 = [[Mestizo]] |

|label1 = [[Mestizo]] |

||

Revision as of 00:28, 21 December 2014

Republic of Guatemala República de Guatemala | |

|---|---|

| Motto: | |

| Anthem: Himno Nacional de Guatemala National anthem of Guatemala | |

| |

| Capital and largest city | Guatemala City |

| Official languages | Spanish |

| Ethnic groups (2001) | |

| Demonym(s) | Guatemalan |

| Government | Unitary presidential republic |

| Otto Pérez Molina | |

| Roxana Baldetti | |

| Legislature | Congress of the Republic |

| Independence from the Spanish Empire | |

• Declared | 15 September 1821 |

• Declared from the First Mexican Empire | 1 July 1823 |

• Current constitution | 31 May 1985 |

| Area | |

• Total | 108,889 km2 (42,042 sq mi) (107th) |

• Water (%) | 0.4 |

| Population | |

• 2014 estimate | 15,806,675[3] (66th) |

• Density | 129/km2 (334.1/sq mi) (85th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2012 estimate |

• Total | $78.681 billion[4] |

• Per capita | $5,208[4] |

| GDP (nominal) | 2012 estimate |

• Total | $49.880 billion[4] |

• Per capita | $3,302[4] |

| Gini (2007) | 55.1 high inequality |

| HDI (2013) | medium (125th) |

| Currency | Quetzal (GTQ) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (CST) |

| Drives on | right |

| Calling code | +502 |

| ISO 3166 code | GT |

| Internet TLD | .gt |

| Part of a series on |

| Central America |

|---|

|

Guatemala,[6] officially the Republic of Guatemala (Spanish: República de Guatemala [re̞ˈpuβlikä ðe̞ ɣwäte̞ˈmälä]), is a country in Central America bordered by Mexico to the north and west, the Pacific Ocean to the southwest, Belize to the northeast, the Caribbean to the east, Honduras to the east and El Salvador to the southeast. It spans an area of 108,890 km2 (42,043 sqmi) and has an estimated population of 15,806,675,[3] making it the most populous state in Central America. A representative democracy, its capital and largest city is Nueva Guatemala de la Asunción, also known as Guatemala City.

What is today Guatemala was for centuries part of the Mayan civilization that extended across Mesoamerica. Most of the country was conquered by the Spanish in the 16th century, becoming part of the colony of New Spain (present-day Mexico). Guatemala attained its independence in 1821 as part of the Federal Republic of Central America, which dissolved in 1841.

From the mid to late 19th century, Guatemala endured the chronic instability and civil strife that was endemic to the region. Early in the 20th century, it was ruled by a series of dictators, who had the support of the United Fruit Company and the United States government. In 1944, one such authoritarian leader, Jorge Ubico, was overthrown by a pro-democratic military coup, initiating the ten-year Guatemalan Revolution that led to sweeping social and economic reforms. The revolution was ended by a U.S.-engineered military coup in 1954.

From 1960 to 1996, Guatemala underwent a bloody civil war fought between the U.S.-backed government and leftist rebels, which included a genocide of the Mayan population perpetrated by the former. Since the war ended, Guatemala has witnessed both economic growth and successful democratic elections, though it continues to struggle with high rates of poverty, crime, and instability. In the most recent election, held in 2011, Otto Pérez Molina of the Patriotic Party won the presidency.

Guatemala's abundance of biologically significant and unique ecosystems, many of which are endemic, contributes to Mesoamerica's designation as a biodiversity hotspot.[7] The country is also known for its rich culture, characterized by a fusion of Spanish and Indigenous influences.

Etymology

The name "Guatemala" comes from Nahuatl Cuauhtēmallān, "place of many trees", a translation of K'iche' Mayan K'iche' , "many trees".[8][9] This was the name the Tlaxcaltecan soldiers who accompanied Pedro de Alvarado during the Spanish Conquest gave to this territory.[10] Guatemala is from words in a native language, variously identified as "Quauhtemellan", "land of the eagle", or "Uhatzmalha", "mountain where water gushes". Hence, it is also translated as "land of eternal spring".

History

Pre-Columbian

The first evidence of human settlers in Guatemala dates back to 12,000 BC. Some evidence suggests human presence as early as 18,000 BC, such as obsidian arrowheads found in various parts of the country.[11] There is archaeological proof that early Guatemalan settlers were hunters and gatherers, but pollen samples from Petén and the Pacific coast indicate that maize cultivation was developed by 3500 BC.[12] Sites dating back to 6500 BC have been found in Quiché in the Highlands and Sipacate, Escuintla on the central Pacific coast.

Archaeologists divided the pre-Columbian history of Mesoamerica into the Preclassic period (2999 BC to 250 BC), the Classic period (250 to 900 AD), and the Postclassic from 900 to 1500 AD.[13] Until recently the Preclassic was regarded as a formative period, with small villages of farmers who lived in huts, and few permanent buildings. However, this notion has been challenged by recent discoveries of monumental architecture from that period, such as an altar in La Blanca, San Marcos, from 1000 BC; ceremonial sites at Miraflores and El Naranjo from 801 BC; the earliest monumental masks; and the Mirador Basin cities of Nakbé, Xulnal, El Tintal, Wakná and El Mirador.

Both the El Tigre and Monos pyramids encompass a volume greater than 250,000 cubic meters,[14] and the city lay at the center of a populous and well-integrated region.

The Classic period of Mesoamerican civilization corresponds to the height of the Maya civilization, and is represented by countless sites throughout Guatemala, although the largest concentration is in Petén. This period is characterized by heavy city-building, the development of independent city-states, and contact with other Mesoamerican cultures.

This lasted until around 900 AD, when the Classic Maya civilization collapsed.[15] The Maya abandoned many of the cities of the central lowlands or were killed off by a drought-induced famine.[16] Scientists debate the cause of the Classic Maya Collapse, but gaining currency is the Drought Theory discovered by physical scientists studying lakebeds, ancient pollen, and other tangible evidence.[17] A series of prolonged droughts, among other reasons (such as overpopulation), in what is otherwise a seasonal desert is thought to have decimated the Maya, who were primarily reliant upon regular rainfall.[18]

The Post-Classic period is represented by regional kingdoms, such as the Itza, Ko'woj, Yalain and Kejache in Petén, and the Mam, Ki'che', Kackchiquel, Chajoma, Tz'utujil, Poqomchi', Q'eqchi' and Ch'orti' in the Highlands. Their cities preserved many aspects of Mayan culture, but would never equal the size or power of the Classic cities.

The Maya civilization shares many features with other Mesoamerican civilizations due to the high degree of interaction and cultural diffusion that characterized the region. Advances such as writing, epigraphy, and the calendar did not originate with the Maya; however, their civilization fully developed them. Maya influence can be detected from Honduras, Guatemala, Northern El Salvador and to as far as central Mexico, more than 1,000 km (620 mi) from the Maya area. Many outside influences are found in Maya art and architecture, which are thought to result from trade and cultural exchange rather than direct external conquest.

Colonial (1519–1821)

After arriving in what was named the New World, the Spanish started several expeditions to Guatemala, beginning in 1519. Before long, Spanish contact resulted in an epidemic that devastated native populations. Hernán Cortés, who had led the Spanish conquest of Mexico, granted a permit to Captains Gonzalo de Alvarado and his brother, Pedro de Alvarado, to conquer this land. Alvarado at first allied himself with the Kaqchikel nation to fight against their traditional rivals the K'iche' (Quiché) nation. Alvarado later turned against the Kaqchikel, and eventually held the entire region under Spanish domination.[19] Several families of Spanish descent subsequently rose to prominence in colonial Guatemala, including the surnames de Arrivillaga, Arroyave, Alvarez de las Asturias, González de Batres, Coronado, Gálvez Corral, Mencos, Delgado de Nájera, de la Tovilla, and Varón de Berrieza.[20]

During the colonial period, Guatemala was an Audiencia and a Captaincy General (Capitanía General de Guatemala) of Spain, and a part of New Spain (Mexico).[21] The first capital, Villa de Santiago de Guatemala (now known as Tecpan Guatemala), was founded on July 25, 1524; it was located near Iximché, the Kaqchikel capital city. The capital was moved to Ciudad Vieja on November 22, 1527, as a result of the Kaqchikel attack on Villa de Santiago de Guatemala. On September 11, 1541, the new capital was flooded when the lagoon in the crater of the Agua Volcano collapsed due to heavy rains and earthquakes; the capital was then moved 6 km (4 mi) to Antigua Guatemala, in the Panchoy Valley, now a UNESCO World Heritage Site. This city was destroyed by several earthquakes in 1773–1774. The King of Spain authorized the move of the capital to its current location in the Ermita Valley, which is named after a Catholic church to the Virgen de El Carmen. This new capital was founded on January 2, 1776.

Independence and the 19th century

On September 15, 1821, the Captaincy-general of Guatemala (formed by Chiapas, Guatemala, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Honduras) officially proclaimed its independence from Spain; the Captaincy-general was dissolved two years later.[22] This region had been formally subject to New Spain throughout the colonial period, but as a practical matter was administered separately. It was not until 1825 that Guatemala created its own flag.[23]

The Guatemalan provinces formed the United Provinces of Central America, also called the Central American Federation (Federacion de Estados Centroamericanos), which dissolved in civil war from 1838 to 1840. Guatemala's General Rafael Carrera was instrumental in leading the revolt against the federal government and breaking apart the Union.[24] As of 1850, it was estimated that Guatemala had a population of 600,000.[25] During this period a region of the Highlands, Los Altos, declared independence from Guatemala, but was annexed by General Carrera, who dominated Guatemalan politics until 1865, backed by the President-Elect Juan Matheu, conservative National Assembly members, large land owners and the church.[26]

Guatemala's "Liberal Revolution" came in 1871 under the leadership of Justo Rufino Barrios, who worked to modernize the country, improve trade, and introduce new crops and manufacturing. During this era coffee became an important crop for Guatemala.[27] Barrios had ambitions of reuniting Central America and took the country to war in an unsuccessful attempt to attain it, losing his life on the battlefield in 1885 against forces in El Salvador.

From 1898 to 1920, Guatemala was ruled by the dictator Manuel Estrada Cabrera, whose access to the presidency was helped by the United Fruit Company. It was during his long presidency that the United Fruit Company became a major force in Guatemala.[28]

1944 to 1996

On July 4, 1944, dictator Jorge Ubico Castañeda was forced to resign his office in response to a wave of protests and a general strike inspired by brutal labor conditions among plantation workers.[29] His replacement, General Juan Federico Ponce Vaides, was forced out of office on October 20, 1944 by a coup d'état led by Major Francisco Javier Arana and Captain Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán. About 100 people were killed in the coup. The country was led by a military junta made up of Arana, Árbenz, and Jorge Toriello Garrido.

The Junta organized Guatemala's first free election, which was won with a majority of 86% by the prominent writer and teacher Juan José Arévalo Bermejo. He had been living in exile in Argentina for 14 years. Arévalo was the first democratically elected president of Guatemala to complete the term for which he was elected. His "Christian Socialist" policies were inspired to a large extent by the U.S. New Deal of President Franklin D. Roosevelt during the Great Depression. Amongst his major policies was a new labor code designed to "right the balance" between workers and Landowners/Industrialists, that was criticized by landowners and the upper class as "communist."[30]

Arévalo was succeeded by Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán, who was elected in 1951. Árbenz adopted a major land reform policy implemented under Decree 900, passed in 1952. It ordered redistribution of uncultivated (fallow) lands of large estates to peasants, including indigenous Mayans. It was intended to increase production of crops and provide many peasants with income. His popular program of land reform, credit, and literacy began to diminish the extreme inequality in Guatemala, although the process of redistributing land created some conflicts.

In 1954, Árbenz was overthrown in a coup d'état orchestrated by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) on the pretext that a socialist government would become a Soviet puppet in the Western Hemisphere. Historians have alleged the CIA overthrew Árbenz to protect the property of the United Fruit Company (later Chiquita Brands International Inc.), a major US company that faced losing large amounts of land due to agrarian reform, and was dissatisfied with the compensation it received.[30][31] Carlos Castillo Armas, a former military officer who led the CIA-backed invasion from Honduras, was installed as president in 1954. Castillo reversed Decree 900 and ruled until July 26, 1957, when he was assassinated by Romeo Vásquez, a member of his personal guard.

After the rigged[30] election that followed, General Miguel Ydígoras Fuentes assumed power. He is celebrated for challenging the Mexican president to a gentleman's duel on the bridge on the south border to end a feud on the subject of illegal fishing by Mexican boats on Guatemala's Pacific coast, two of which were sunk by the Guatemalan Air Force. Ydigoras authorized the training of 5,000 anti-Castro Cubans in Guatemala. He also provided airstrips in the region of Petén for what later became the US-sponsored, failed Bay of Pigs Invasion in 1961. Ydigoras' government was ousted in 1963 when the Guatemalan Air Force attacked several military bases; the coup was led by his Defense Minister, Colonel Enrique Peralta Azurdia.

In 1963, the junta called an election, which it permitted Arevalo to return from exile and contest. However a coup from within the military, backed by the Kennedy Administration, prevented the election from taking place, and forestalled a likely victory for Arevalo. The new regime intensified the campaign of terror against the guerrillas that had begun under Ydígoras-Fuentes.[32]

In 1966, Julio César Méndez Montenegro was elected president of Guatemala under the banner "Democratic Opening". Mendez Montenegro was the candidate of the Revolutionary Party, a center-left party that had its origins in the post-Ubico era. During this time rightist paramilitary organizations, such as the "White Hand" (Mano Blanca), and the Anticommunist Secret Army (Ejército Secreto Anticomunista) were formed. Those groups were the forerunners of the infamous "Death Squads". Military advisers from the United States Army Special Forces (Green Berets) were sent to Guatemala to train these troops and help transform its army into a modern counter-insurgency force, which eventually made it the most sophisticated in Central America.[33]

In 1970, Colonel Carlos Manuel Arana Osorio was elected president. By 1972, members of the guerrilla movement entered the country from Mexico and settled in the Western Highlands. In the disputed election of 1974, General Kjell Laugerud García defeated General Efraín Ríos Montt, a candidate of the Christian Democratic Party, who claimed that he had been cheated out of a victory through fraud.

On February 4, 1976, a major earthquake destroyed several cities and caused more than 25,000 deaths, especially among the poor, whose housing was substandard. The government's failure to respond rapidly to the aftermath of the earthquake and to relieve homelessness, gave rise to widespread discontent, which contributed to growing popular unrest. In 1978, in a fraudulent election, General Romeo Lucas García assumed power.

The 1970s saw the rise of two new guerrilla organizations, the Guerrilla Army of the Poor (EGP) and the Organization of the People in Arms (ORPA). They began guerrilla attacks that included urban and rural warfare, mainly against the military and some of the civilian supporters of the army. The army and the paramilitary forces responded with a brutal counter-insurgency campaign that resulted in tens of thousands of civilian deaths.[34] In 1979, the U.S. president, Jimmy Carter, who had until then been providing public support for the government forces, ordered a ban on all military aid to the Guatemalan Army because of its widespread and systematic abuse of human rights.[30] However, documents have since come to light that suggest that American aid continued throughout the Carter years, through clandestine channels.[35]

On January 31, 1980, a group of indigenous K'iche' took over the Spanish Embassy to protest army massacres in the countryside. The Guatemalan government launched an assault with armed forces that killed almost everyone inside due to a fire that consumed the building. The Guatemalan government claimed that the activists set the fire, thus immolating themselves.[36] However, the Spanish ambassador, who survived the fire, disputed this claim, saying that the Guatemalan police intentionally killed almost everyone inside and set the fire to erase traces of their acts. As a result, the government of Spain broke diplomatic relations with Guatemala.

This government was overthrown in 1982 and General Efraín Ríos Montt was named President of the military junta. He continued the bloody campaign of torture, forced disappearances, and "scorched earth" warfare. The country became a pariah state internationally, although the regime received considerable support from the Reagan Administration,[37] and Reagan himself described Ríos Montt as "a man of great personal integrity."[38] Ríos Montt was overthrown by General Óscar Humberto Mejía Victores, who called for an election of a national constitutional assembly to write a new constitution, leading to a free election in 1986, which was won by Vinicio Cerezo Arévalo, the candidate of the Christian Democracy Party.

In 1982, the four guerrilla groups, EGP, ORPA, FAR and PGT, merged and formed the URNG, influenced by the Salvadoran guerrilla FMLN, the Nicaraguan FSLN and Cuba's government, in order to become stronger. As a result of the Army's "scorched earth" tactics in the countryside, more than 45,000 Guatemalans fled across the border to Mexico. The Mexican government placed the refugees in camps in Chiapas and Tabasco.

In 1992, the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to Rigoberta Menchú for her efforts to bring international attention to the government-sponsored, US backed genocide against the indigenous population.[39]

Since 1996

The Guatemalan Civil War ended in 1996 with a peace accord between the guerrillas and the government, negotiated by the United Nations through intense brokerage by nations such as Norway and Spain. Both sides made major concessions. The guerrilla fighters disarmed and received land to work. According to the U.N.-sponsored truth commission (the "Commission for Historical Clarification"), government forces and state-sponsored, CIA trained paramilitaries were responsible for over 93 percent of the human rights violations during the war.[40]

Over the last few years, millions of documents related to crimes committed during the civil war were found abandoned by the former Guatemalan police. Among millions of documents found, there was evidence that the former police chief of Guatemala, Hector Bol de la Cruz, had been involved in the kidnapping and murder of 27-year-old student Fernando Garcia in 1984. The evidence was used to prosecute the former police chief. The families of over 45,000 Guatemalan activists are now reviewing the documents (which have been digitized) and this could lead to further legal actions. Paradoxically, the current democratically elected president, Otto Pérez Molina, could be a barrier to further legal action as he, a retired general, was the head of intelligence in Guatemala during the civil war.[41]

During the first ten years, the victims of the state-sponsored terror were primarily students, workers, professionals, and opposition figures, but in the last years they were thousands of mostly rural Mayan farmers and non-combatants. More than 450 Mayan villages were destroyed and over 1 million people became displaced within Guatemala or refugees. According to the report, Recuperación de la Memoria Histórica (REMHI), some 200,000 people died. More than one million people were forced to flee their homes and hundreds of villages were destroyed. The officially chartered Historical Clarification Commission attributed more than 93% of all documented violations of human rights to Guatemala's military government, and estimated that Maya Indians accounted for 83% of the victims. It concluded in 1999 that state actions constituted genocide.[42][43]

In certain areas, such as Baja Verapaz, the Truth Commission considered that the Guatemalan state engaged in an intentional policy of genocide against particular ethnic groups in the Civil War.[40] In 1999, U.S. president Bill Clinton stated that the United States was wrong to have provided support to Guatemalan military forces that took part in the brutal civilian killings.[44]

Since the peace accords, Guatemala has witnessed both economic growth and successive democratic elections, most recently in 2011. In the 2011 elections, Otto Pérez Molina of the Patriotic Party, won the presidency. He assumed office on January 14, 2012. He named Roxana Baldetti as his vice president.

On January 12, 2012, Efrain Rios Montt, the former dictator of Guatemala, appeared in a Guatemalan court on genocide charges. During the hearing, the government presented evidence of over 100 incidents involving at least 1,771 deaths, 1,445 rapes, and the displacement of nearly 30,000 Guatemalans during his 17-month rule from 1982–1983, according to the Washington Post, BBC, Siglo XXI Template:Es icon, and the LA Times. The prosecution wanted him incarcerated because of his potential for flight but the judge ruled that he could remain outside on bail. He was placed under house arrest and was watched by the Guatemalan National Civil Police (PNC). On May 10, 2013, Rios Montt was found guilty and sentenced to 80 years in prison. It marks the first time, a former head of state was found guilty for genocide by national court.[45] The conviction was overturned, however, and Montt's trial is scheduled to resume in January 2015. [46]

The estimated median age in Guatemala is 20 years old, 19.4 for males and 20.7 years for females.[47] This is the lowest median age of any country in the Western Hemisphere and comparable to most of central Africa and Iraq.

Noam Chomsky argues that Guatemala "remains one of the world's worst horror chambers" as a direct result of the U.S.-backed coup d'état in 1954 and subsequent support for various authoritarian governments.[48]

Governance

Political system

Guatemala is a constitutional democratic republic whereby the President of Guatemala is both head of state and head of government, and of a multi-party system. Executive power is exercised by the government. Legislative power is vested in both the government and the Congress of the Republic. The judiciary is independent of the executive and the legislature.

Otto Pérez Molina is the current President of Guatemala.

Departments and municipalities

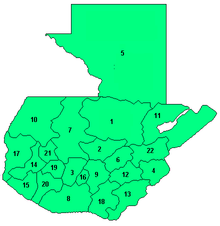

Guatemala is divided into 22 departments (departamentos) and sub-divided into about 335 municipalities (municipios).

The departments are:

Alta Verapaz

Alta Verapaz- File:Coat of arms of Baja Verapaz.gif Baja Verapaz

Chimaltenango

Chimaltenango Chiquimula

Chiquimula Petén

PeténEl Progreso

El Quiché

El Quiché Escuintla

Escuintla Guatemala

Guatemala Huehuetenango

Huehuetenango Izabal

Izabal Jalapa

Jalapa Jutiapa

Jutiapa Quetzaltenango

Quetzaltenango Retalhuleu

Retalhuleu Sacatepéquez

Sacatepéquez San Marcos

San Marcos Santa Rosa

Santa Rosa Sololá

Sololá Suchitepéquez

Suchitepéquez Totonicapán

Totonicapán Zacapa

Zacapa

Guatemala is heavily centralized. Transportation, communications, business, politics, and the most relevant urban activity takes place in Guatemala City. Guatemala City has about 2 million inhabitants within the city limits and more than 5 million within the urban area. This is a significant percentage of the population (14 million).[47]

Geography

Guatemala lies between latitudes 13° and 18°N, and longitudes 88° and 93°W.

The country is mountainous with small desert and sand dune patches, hilly valleys, except for the south coastal area and the vast northern lowlands of Petén department. Two mountain chains enter Guatemala from west to east, dividing the country into three major regions: the highlands, where the mountains are located; the Pacific coast, south of the mountains and the Petén region, north of the mountains. All major cities are located in the highlands and Pacific coast regions; by comparison, Petén is sparsely populated. These three regions vary in climate, elevation, and landscape, providing dramatic contrasts between hot, humid tropical lowlands and colder, drier highland peaks. Volcán Tajumulco, at 4,220 m, is the highest point in the Central American countries.

The rivers are short and shallow in the Pacific drainage basin, larger and deeper in the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico drainage basins, which include the Polochic and Dulce Rivers, which drain into Lake Izabal, the Motagua River, the Sarstún that forms the boundary with Belize, and the Usumacinta River, which forms the boundary between Petén and Chiapas, Mexico.

Guatemala has long claimed all or part of the territory of neighboring Belize, currently an independent Commonwealth realm that recognises Queen Elizabeth II as its Head of State. Due to this territorial dispute, Guatemala did not recognize Belize's independence until 1990, but the dispute is not resolved. Negotiations are currently under way under the auspices of the Organization of American States and the Commonwealth of Nations to conclude it.[49][50]

Largest cities

Template:Largest cities of Guatemala

Natural disasters

Guatemala's location between the Caribbean Sea and Pacific Ocean makes it a target for hurricanes, such as Hurricane Mitch in 1998 and Hurricane Stan in October 2005, which killed more than 1,500 people. The damage was not wind related, but rather due to significant flooding and resulting mudslides. The most recent was Tropical Storm Agatha in late May 2010 that killed more than 200.

Guatemala's highlands lie along the Motagua Fault, part of the boundary between the Caribbean and North American tectonic plates. This fault has been responsible for several major earthquakes in historic times, including a 7.5 magnitude tremor on February 4, 1976, which killed more than 25,000 people. In addition, the Middle America Trench, a major subduction zone lies off the Pacific coast. Here, the Cocos Plate is sinking beneath the Caribbean Plate, producing volcanic activity inland of the coast. Guatemala has 37 volcanoes, four of them are active: Pacaya, Santiaguito, Fuego and Tacaná. Fuego and Pacaya erupted in 2010.

Natural disasters have a long history in this geologically active part of the world. For example, two of the three moves of the capital of Guatemala have been due to volcanic mudflows in 1541 and earthquakes in 1773.

Biodiversity

The country has 14 ecoregions ranging from mangrove forests to both ocean littorals with 5 different ecosystems. Guatemala has 252 listed wetlands, including 5 lakes, 61 lagoons, 100 rivers, and 4 swamps.[51] Tikal National Park was the first mixed UNESCO World Heritage Site. Guatemala is a country of distinct fauna. It has some 1246 known species. Of these, 6.7% are endemic and 8.1% are threatened. Guatemala is home to at least 8,681 species of vascular plants, of which 13.5% are endemic. 5.4% of Guatemala is protected under IUCN categories I-V.[citation needed]

In the department of Petén lies the Maya Biosphere Reserve of 2,112,940 ha,[52] making it the second largest forest in Central America after Bosawas.

Demographics

According to the CIA World Fact Book, Guatemala has a population of 15,824,463 (2014 est). About 59% of the population is Ladino, also called Mestizo, and European descendants, also called Criollo. Amerindian populations include the K'iche' 9.1%, Kaqchikel 8.4%, Mam 7.9% and Q'eqchi 6.3%. 8.6% of the population is "other Mayan", 0.4% is indigenous non-Mayan, making the indigenous community in Guatemala about 40.5% of the population.[47]

There are smaller communities present. The Garífuna, who are descended primarily from Black Africans who lived with and intermarried with indigenous peoples from St. Vincent, live mainly in Livingston and Puerto Barrios. Those communities have other blacks and mulattos descended from banana workers. There are also Asians, mostly of Chinese descent. Other Asian groups include Arabs of Lebanese and Syrian descent. There is also a growing Korean community in Guatemala City and in nearby Mixco, currently numbering about 10,000.[53] Guatemala's German population is credited with bringing the tradition of a Christmas tree to the country.[54]

In 1900, Guatemala had a population of 885,000.[55] Over the course of the 20th century the population of the country had the fastest growth in the Western Hemisphere. The ever-increasing pattern of immigration to the U.S. has led to the growth of Guatemalan communities in California, Delaware, Florida, Illinois, New York, New Jersey, Texas, Rhode Island and elsewhere since the 1970s.[56]

Languages

Although Spanish is the official language, it is not universally spoken among the indigenous population, nor is it often spoken as a second language by the elderly indigenous. Twenty-one Mayan languages are spoken, especially in rural areas, as well as two non-Mayan Amerindian languages, Xinca, an indigenous language, and Garifuna, an Arawakan language spoken on the Caribbean coast. According to the Language Law of 2003, the languages of Mayas, Xincas, and Garifunas are unrecognized as National Languages.[57]

As a first and second language, Spanish is spoken by 93% of the population.

The peace accords signed in December 1996 provide for the translation of some official documents and voting materials into several indigenous languages (see summary of main substantive accords) and mandate the provision of interpreters in legal cases for non-Spanish speakers. The accord also sanctioned bilingual education in Spanish and indigenous languages. It is common for indigenous Guatemalans to learn or speak between two to five of the nation's other languages, and Spanish.[citation needed]

Diaspora

The Civil War forced many Guatemalans to start lives outside of their country. The majority of the Guatemalan diaspora is located in the United States, with estimates ranging from 480,665[58] to 1,489,426.[59] The difficulty in getting accurate counts for Guatemalans abroad is because many of them are refugee claimants awaiting determination of their status.[60] Below are estimates for certain countries:

| Country | Count |

|---|---|

| 480,665[58] – 1,489,426[59] | |

| 23,529[59] – 190,000 | |

| 14,693[59] | |

| 14,256[59] – 34,665[61] | |

| 5,989[59] | |

| 5,172[59] | |

| 4,209[59] | |

| 2,491[59] – 5,000[62] |

Economy

Guatemala is the largest economy in Central America, with a GDP (PPP) per capita of US$5,200; nevertheless, this developing country faces many social problems and is one of the poorest countries in Latin America. The distribution of income remains highly unequal with more than half of the population below the national poverty line and just over 400,000 (3.2%) unemployed. The CIA World Fact Book considers 56.2% of the population of Guatemala to be living in poverty.[47][63]

Remittances from Guatemalans who fled to the United States during the civil war now constitute the largest single source of foreign income (two thirds of exports and one tenth of GDP).[47]

In recent years, the exporter sector of nontraditional products has grown dynamically, representing more than 53% of global exports. Some of the main products for export are fruits, vegetables, flowers, handicrafts, cloths and others. In the face of a rising demand for biofuels, the country is growing and exporting an increasing amount of raw materials for biofuel production, especially sugar cane and palm oil. Critics say that this development leads to higher prices of staple foods like corn, a major ingredient in the Guatemalan diet. As a consequence of the subsidization of US American corn, Guatemala imports nearly half of its corn from the United States that is using 40 percent of its crop harvest for biofuel production.[64] The government is considering ways to legalize poppy and marijuana production, hoping to tax production and use tax revenues to fund drug prevention programs and other social projects.[65]

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in purchasing power parity (PPP) in 2010 was estimated at $70.15 billion USD. The service sector is the largest component of GDP at 63%, followed by the industry sector at 23.8% and the agriculture sector at 13.2% (2010 est.). Mines produce gold, silver, zinc, cobalt and nickel.[66] The agricultural sector accounts for about two-fifths of exports, and half of the labor force. Organic coffee, sugar, textiles, fresh vegetables, and bananas are the country's main exports. Inflation was 3.9% in 2010.

The 1996 peace accords that ended the decades-long civil war removed a major obstacle to foreign investment. Tourism has become an increasing source of revenue for Guatemala.

In March 2006, Guatemala's congress ratified the Dominican Republic – Central American Free Trade Agreement (DR-CAFTA) between several Central American nations and the United States.[67] Guatemala also has free trade agreements with Taiwan and Colombia.

Education

The government runs a number of public elementary and secondary-level schools. These schools are free, though the cost of uniforms, books, supplies, and transportation makes them less accessible to the poorer segments of society and significant numbers of poor children do not attend school. Many middle and upper-class children go to private schools. The country also has one public university (USAC or Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala), and nine private ones (see List of universities in Guatemala). USAC was the first university in Guatemala and one of the first Universities of America. It was officially declared a university on January 31, 1676 by royal command of King Charles II of Spain. Only 74.5% of the population aged 15 and over is literate, the lowest literacy rate in Central America. Although it has the lowest literacy rate, Guatemala is expected to change this within the next 20 years.[68] Organizations such as Child Aid and Pueblo a Pueblo, which train teachers in villages throughout the Central Highlands region, are working to improve educational outcomes for children. Lack of training for rural teachers is one of the key contributors to the country's low literacy rates.

Health

Guatemala is among the worst performers in terms of health outcomes in Latin America with some of the highest infant mortality rates, and one of the lowest life expectancies at birth in the region.[69] The country has about 16,000 doctors for its 16 million people and the WHO recommends about double that ratio.[70] Since the end of the Guatemalan Civil War in 1997 the Ministry of Health has extended healthcare access to 54% of the rural population.[71] Healthcare has received different levels of support from different political administrations who disagree on how best to manage distribution of services (via a private or a public entity) and the scale of financing that should be made available.[71] As of 2013 the Ministry of Health lacked the financial means to monitor or evaluate its programs.[71]

Total health care spending (both public and private) has remained constant at between 6.4–7.3% of GDP.[72][73] Per-capita average spending was $368 a year in 2012.[73] Guatemalan patients choose between the two systems (the indigenous way of practicing medicine or the Western-trained health care providers) based on the complex conditions surrounding the ailment and decide which medical system will most likely provide a cure for their ailment.[74]

Culture

Guatemala City is home to many of the nation's libraries and museums, including the National Archives, the National Library, and the Museum of Archeology and Ethnology, which has an extensive collection of Maya artifacts. There are private museums, such as the Ixchel, which focuses on textiles, and the Popol Vuh, which focuses on Maya archaeology. Both museums are housed inside the Universidad Francisco Marroquín campus. Most of the 329 municipalities in the country has a small museum.

Art

Guatemala has produced many indigenous artists who follow centuries-old Pre-Columbian traditions. However, reflecting Guatemala's colonial and post-colonial history, encounters with multiple global art movements also have produced a wealth of artists who have combined the traditional so-called "primitivism" or "naive" aesthetic with European, North American, and other traditions. The Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas "Rafael Rodríguez Padilla" is the country's leading art school, and several leading indigenous artists, also graduates of that school, are in the permanent collection of the Museo Nacional de Arte Moderno in the capital city. Contemporary Guatemalan artists who have gained reputations outside of Guatemala include Dagoberto Vásquez, Luis Rolando Ixquiac Xicara, Carlos Mérida,[75] Aníbal López, Roberto González Goyri, and Elmar René Rojas.[76]

Literature

The Guatemala National Prize in Literature is a one-time only award that recognizes an individual writer's body of work. It has been given annually since 1988 by the Ministry of Culture and Sports.

Miguel Ángel Asturias won the literature Nobel Prize in 1967. Among his famous books is El Señor Presidente, a novel based on the government of Manuel Estrada Cabrera.

Rigoberta Menchú, winner of the Nobel Peace Prize for fighting oppression of indigenous people in Guatemala, is famous for her books I, Rigoberta Menchú and Crossing Borders.

Journalism

There are seven national newspapers in TV, some of them being Noti7, Telecentro Trece and Noticiero Guatevision. The Guatemala Times is a digital English news magazine.[77]

Music

The music of Guatemala comprises a number of styles and expressions. Guatemalan social change has been empowered by music scenes such as Nueva cancion, which blends together histories, present day issues, and the political values and struggles of common people. The Maya had an intense musical practice, as is documented by iconography. Guatemala was also one of the first regions in the New World to be introduced to European music, from 1524 on. Many composers from the Renaissance, baroque, classical, romantic, and contemporary music styles have contributed works of all genres. The marimba is the national instrument that has developed a large repertoire of very attractive pieces that have been popular for more than a century.

The Historia General de Guatemala has published a series of CDs of historical music of Guatemala, in which every style is represented, from the Maya, colonial period, independent and republican eras to current times. There are many contemporary music groups in Guatemala from Caribbean music, salsa, punta (Garifuna influenced), Latin pop, Mexican regional, and mariachi.

Cuisine

Many traditional foods in Guatemalan cuisine are based on Maya cuisine and prominently feature corn, chilies and beans as key ingredients. There are also foods that are commonly eaten on certain days of the week. For example, it is a popular custom to eat paches (a kind of tamale made from potatoes) on Thursday. Certain dishes are also associated with special occasions, such as fiambre for All Saints Day on November 1, tamales and ponche (a hot drink, with actual pieces of fruit in it), which are both very common around Christmas.

Religion

50–60% of the Guatemalan population is Roman Catholic, 30–40% Protestant,[78] and at least 1% Eastern Orthodox.[79] Catholicism was the official religion during the colonial era. However, the practice of Protestantism has increased markedly in recent decades. Nearly one third of Guatemalans are Protestant, chiefly Evangelicals and Pentecostals. It is common for relevant Mayan practices to be incorporated into Catholic ceremonies and worship when they are sympathetic to the meaning of Catholic belief; this phenomenon is known as inculturation.[80][81] The practice of traditional Mayan religion is increasing as a result of the cultural protections established under the peace accords. The government has instituted a policy of providing altars at every Mayan ruin found in the country, so traditional ceremonies may be performed there. Among the Mayan population the National Evangelical Presbyterian Church of Guatemala is an important denomination. The church has 11 indigenous-language Presbyteries.

Recent growth of Eastern Orthodoxy in Guatemala has been nothing less than explosive, with hundreds of thousands of converts in the last five years,[82][83][79] making it almost overnight the most Orthodox nation (in proportion to its population) in the western hemisphere.

There are also small communities of Jews estimated between 1200 and 2000,[84] Muslims (1200), Buddhists at around 9000 to 12000,[85] and members of other faiths and those who do not profess any faith.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints currently has over 215,000 members in Guatemala, accounting for approximately 1.65% of the country's estimated population in 2008.[86] The first member of the LDS Church in Guatemala was baptized in 1948. Membership grew to 10,000 by 1966, and 18 years later, when the Guatemala City Temple[87][88] was dedicated in 1984, membership had risen to 40,000. By 1998 membership had quadrupled again to 164,000.[86] The LDS Church continues to grow in Guatemala; it has announced and begun the construction of the Quetzaltenango Guatemala Temple,[89] the LDS Church's second temple in the country.[90]

Sports

Football is the most popular sport in Guatemala.

See also

- Index of Guatemala-related articles

- Outline of Guatemala

- International rankings of Guatemala

- LGBT rights in Guatemala

- List of Guatemalans

- List of places in Guatemala

- German immigration to Guatemala

- Military of Guatemala

References

- ^ "Ilustraciones de Cada una de las 11 Denominaciones. Anverso y Reverso". Banguat.gob.gt. December 29, 1996. Retrieved September 22, 2013.

- ^ Aguirre, Lily (1949). The land of eternal spring: Guatemala, my beautiful country. Patio Press. p. 253.

- ^ a b "Poblacion de Guatemala (Demografia)". Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE). June 7, 2014.

- ^ a b c d "Guatemala". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved April 18, 2013.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2011" (PDF). United Nations. 2011. Retrieved December 22, 2011.

- ^ US: /ˌɡwɑːt[invalid input: 'i-']ˈmɑːlə/ GWAH-tə-MAH-lə, UK: /ˌɡwæt[invalid input: 'i-']ˈmɑːlə/ GWAT-ə-MAH-lə

- ^ "Biodiversity Hotspots-Mesoamerica-Overview". Conservation International. Retrieved February 1, 2007.

- ^ Campbell, Lyle. (1997). American Indian languages: The historical linguistics of Native America. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-509427-1.

- ^ www.ccidinc.org.[dead link] Retrieved June 26, 2012.

- ^ "Guatemala Rainforest Interesting fact | rainforest facts". Rainforestcentralamerica.wordpress.com. April 4, 2013. Retrieved September 22, 2013.

- ^ Mary Esquivel de Villalobos. "Ancient Guatemala". Authentic Maya. Retrieved April 29, 2007.

- ^ Barbara Leyden. "Pollen Evidence for Climatic Variability and Cultural Disturbance in the Maya Lowlands" (PDF). University of Florida. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 6, 2009.

- ^ "Chronological Table of Mesoamerican Archaeology". Regents of the University of California : Division of Social Sciences. Retrieved April 29, 2007.

- ^ Trigger, Bruce G. and Washburn, Wilcomb E. and Adams, Richard E. W. The Cambridge History of the Native Peoples of the Americas. 2000, page 212.

- ^ Richardson Benedict Gill (2000)."The great Maya droughts: water, life, and death". University of New Mexico Press. p.384. ISBN 0-8263-2774-5

- ^ Dr. Richardson Gill, The Great Maya Droughts (2000), University of New Mexico Press.

- ^ Dr. Richardson Gill, The Great Maya Droughts (2000), University of New Mexico Press

- ^ Foster, Lynn V. (2000). A Brief History of Central America.. New York: Facts On File, Inc. ISBN 0-8160-3962-3.

- ^ Lienzo de Quauhquechollan digital map exhibition on the History of the conquest of Guatemala.

- ^ Douglas R. White The Marriage Core of the Elite Network of Colonial Guatemala (2002), University of California, Irvine, School of Social Sciences.

- ^ Foster 2000, pp. 69–71.

- ^ Foster 2000, pp. 134–136.

- ^ "Flag". Guatemala Go. Retrieved September 22, 2013.

- ^ Foster 2000, pp. 148–149.

- ^ Baily, John (1850). Central America; Describing Each of the States of Guatemala, Honduras, Salvador, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica. London: Trelawney Saunders. p. 55.

- ^ Foster 2000,. pp. 152–160.

- ^ Foster 2000, pp. 173–175.

- ^ Frederick Douglass Opie, Black Labor Migration in Caribbean Guatemala, 1882–1923,(University of Florida Press, 2009), chapters 2–3.

- ^ Forster, Cindy (1994). "The Time of "Freedom": San Marcos Coffee Workers and the Radicalization of the Guatemalan National Revolution, 1944–1954". Radical History Review. 58: 35–78. doi:10.1215/01636545-1994-58-35.

- ^ a b c d Chomsky, Noam (1985). Turning the Tide. Boston, Massachusetts: South End Press. pp. 154–160.

- ^ Nicholas Cullather, Secret History: The CIA's Classified Account of its Operation in Guatemala, 1952–1954 (Stanford University Press, 1999), pp 24–7, based on the CIA archives

- ^ McClintock, Michael (1987). American Connection.

- ^ Chomsky, Noam (1985). Turning the Tide. Boston, Massachusetts: South End Press.

- ^ Lafeber, Walter (1983). Inevitable Revolutions. p. 165.

- ^ McClintock, Michael (1987). The American Connection Vol II. pp. 216–7.

- ^ "Outright Murder". Time.com. February 11, 1980. Retrieved June 1, 2010.

- ^ What Guilt Does the U.S. Bear in Guatemala? The New York Times, 19 May 2013. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- ^ Allan Nairn: After Ríos Montt Verdict, Time for U.S. to Account for Its Role in Guatemalan Genocide. Democracy Now! May 15, 2013.

- ^ Burgos-Debray, Elizabeth (2010). I, Rigoberta Menchu. Verso.

- ^ a b "Conclusions: Human rights violations, acts of violence and assignment of responsibility". Guatemala: Memory of Silence. Guatemalan Commission for Historical Clarification. Retrieved December 26, 2006.

- ^ "Los archivos hallados en 2005 podrían ayudar a esclarecer los crímenes cometidos durante la guerra civil" (in Spanish). Europapress.es. February 9, 2012. Retrieved September 22, 2013.

- ^ "Gibson film angers Mayan groups". BBC News. December 8, 2006.

- ^ "GENOCIDE – GUATEMALA"

- ^ Babington, Charles (March 11, 1999). "Clinton: Support for Guatemala Was Wrong". Washington Post. pp. Page A1. Retrieved September 21, 2013.

- ^ Malkin, Elisabeth (May 10, 2013). "Gen. Efraín Ríos Montt of Guatemala Guilty of Genocide". The New York Times.

- ^ Guatemala Rios Montt genocide trial to resume in 2015. BBC, 6 November 2013.

- ^ a b c d e "CIA World Factbook, Guatemala". July 2011. Retrieved December 22, 2011.

- ^ Noam Chomsky (July 3, 2014). Whose Security? How Washington Protects Itself and the Corporate Sector. Moyers & Company. Retrieved July 13, 2014.

- ^ Montserrat Gorina-Ysern. "OAS Mediates in Belize-Guatemala Border Dispute". ASIL Insights. American Society of International Law. Retrieved April 29, 2007.

- ^ Jorge Luján Muñoz, director general. (2005). Historia General de Guatemala. Guatemala: Asociación de Amigos del País. ISBN 84-88622-07-4.

- ^ Archived 2006-04-06 at the Wayback Machine. iucn.org

- ^ "MAB Biosphere Reserves Directory". UNESCO. Retrieved June 1, 2010.

- ^ Luisa Rodríguez Archived 2009-03-30 at the Wayback Machine. prensalibre.com. 29 August 2004

- ^ History of the Christmas Tree[dead link]

- ^ "Population Statistics". Populstat.info. Retrieved June 1, 2010.

- ^ "Migration Information Statistics". Migrationinformation.org. Retrieved June 1, 2010.

- ^ "Ley de Idiomas Nacionales, Decreto Número 19-2003" (PDF) (in Spanish). El Congreso de la República de Guatemala. Retrieved June 10, 2007.

- ^ a b The 2000 U.S. Census recorded 480,665 Guatemalan-born respondents; see Smith (2006)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Smith, James (April 2006). "DRC Migration, Globalisation and Poverty".

- ^ "Guatemalans". multiculturalcanada.ca. November 2009. Archived from the original on April 20, 2008.

- ^ "Guatemala" (PDF). Retrieved June 1, 2010.

- ^ "Embajada de Guatemala en España". Embajadaguatemala.es. Retrieved June 1, 2010.

- ^ "Guatemala: An Assessment of Poverty". World Bank. Retrieved January 9, 2009.

- ^ As Biofuel Demands Grows, So Do Guatemala's Hunger Pangs. The New York Times. January 5, 2013

- ^ Sees Opium Poppies as Potential Revenue-spinners. Voice of America. May 7, 2014

- ^ Dan Oancea Mining In Central America[dead link]. Mining Magazine. January 2009

- ^ Archived 2007-02-08 at the Wayback Machine Amnesty International, 2006. Retrieved January 26, 2007.

- ^ Education (all levels) profile – Guatemala. UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Retrieved on 2012-01-02.

- ^ World Bank, Poverty and Inequality, 2003, http://econ.worldbank.org/external/default/main?pagePK=64165259&theSitePK=477894&piPK=64165421&menuPK=64166093&entityID=000094946_0302070416252

- ^ The Healthcare System in Guatemala, blog, 2012, http://naranetacrossing.wordpress.com/2012/09/27/the-healthcare-system-in-guatemala/

- ^ a b c Universal Health Coverage Studies Series (UNICO),UNICO Studies Series No. 19, Christine Lao Pena, Improving Access to Health Care Services through the Expansion of Coverage Program (PEC): The Case of Guatemala,p. 7, http://www-wds.worldbank.org/external/default/WDSContentServer/WDSP/IB/2013/02/04/000425962_20130204103631/Rendered/PDF/750010NWP0Box30ge0Program0GUATEMALA.pdf

- ^ World Bank Data, http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.TOTL.ZS/countries/GT?display=graph

- ^ a b WHO Country data, Guatemala, 2012, http://www.who.int/countries/gtm/en/

- ^ Walter Randolph Adams and John P. Hawkins, Health Care in Maya Guatemala: Confronting Medical Pluralism in a Developing Country (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2007), 4–10.

- ^ "retrieved September 28, 2009". Latinartmuseum.com. October 1, 2009. Retrieved June 1, 2010.

- ^ "Elmar Rojas y la utopia pictorica latinoamercana". Latinartmuseum.com. Retrieved June 1, 2010.

- ^ "''The Guatemala Times''". Guatemala-times.com. Retrieved September 22, 2013.

- ^ "state department". State.gov. September 15, 2006. Retrieved June 1, 2010.

- ^ a b Jackson, Fr. Peter (September 13, 2013). "150,000 Converts in Guatemala". Interview Transcript. Ancient Faith Radio. Retrieved May 23, 2014.

- ^ From Guatemala: the focolare, a school of inculturation. Focolare. July 28, 2011. Retrieved on 2012-01-02.

- ^ Duffey, Michael K Guatemalan Catholics and Mayas: The Future of Dialogue

- ^ "Orthodox Catholic Church of Guatemala". Orthodox Metropolis of Mexico. 2013. Retrieved May 23, 2014.

- ^ Brandow, Jesse (August 27, 2012). "Seminarian Witnesses "Explosion" of Orthodox Christianity in Guatemala". St. Vladimir's Orthodox Theological Seminary. Retrieved May 23, 2014.

- ^ "Guatemala". State.gov. April 3, 2007. Retrieved June 1, 2010.

- ^ Archived 2009-10-23 at the Wayback Machine. religiousintelligence.co.uk

- ^ a b [1][dead link]

- ^ "Guatemala City Guatemala Temple Main". Lds.org. Retrieved June 1, 2010.

- ^ "Temples – LDS Newsroom". Newsroom.lds.org. December 22, 2010. Archived from the original on December 22, 2010. Retrieved June 1, 2010.

- ^ "Quetzaltenango Guatemala Temple – Mormonism, The Mormon Church, Beliefs, & Religion". MormonWiki. Retrieved June 1, 2010.

- ^ "Templo Quetzaltenango". Mormones.org.gt. Retrieved June 1, 2010.[dead link]

Further reading

- "Chapter Ten: Guatemala". Politics of Latin America: The Power Game. Oxford University Press. 2002. ISBN 0-19-512317-4.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help)

External links

- Guatemala After the War 1996–2000, Photographs by Jorge Uzon

- Guatemala Map Search with Longitude and Latitude

- Guatemala – Country Article Encyclopædia Britannica

- Government of Guatemala Template:Es icon

- Chief of State and Cabinet Members

- "Guatemala". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency.

- Guatemala at UCB Libraries GovPubs.

- Template:Dmoz

- Guatemala profile from the BBC News.

Wikimedia Atlas of Guatemala

Wikimedia Atlas of Guatemala- Key Development Forecasts for Guatemala from International Futures.

- The National Security Archive: Guatemala Project

- Guatemala Tourism Commission

- World Bank Summary Trade Statistics Guatemala