M16 rifle: Difference between revisions

SStephens13 (talk | contribs) m minor rewording in the intro |

Tag: blanking |

||

| Line 59: | Line 59: | ||

The M16 is a lightweight, 5.56 mm, air-cooled, [[Gas-operated reloading|gas-operated]], [[Magazine (firearm)|magazine]]-fed [[assault rifle]], with a [[rotating bolt]], actuated by [[direct impingement]] gas operation. The rifle is made of steel, [[7075 aluminium alloy|7075 aluminum alloy]], composite plastics and polymer materials. |

The M16 is a lightweight, 5.56 mm, air-cooled, [[Gas-operated reloading|gas-operated]], [[Magazine (firearm)|magazine]]-fed [[assault rifle]], with a [[rotating bolt]], actuated by [[direct impingement]] gas operation. The rifle is made of steel, [[7075 aluminium alloy|7075 aluminum alloy]], composite plastics and polymer materials. |

||

ArmaLite sold its righ-contract-m16a3-m16a4-rifles/ Sabre Defence Industries Awarded M16 Rifle Contract].</ref> Semi-automatic versions of the AR-15 are popular recreational shooting rifles, with versions manufactured by other small and large manufacturers in the U.S.<ref>[http://www.ar-15.us/AR15_Manufacturers.php AR15 Manufacturers & Builders].</ref> The M16 rifle design, including variant or modified version of it such as the [[Armalite]]/Colt [[AR-15]] series, AAI M15 rifle; AP74; EAC J-15; SGW XM15A; any 22-caliber rimfire variant, including the Mitchell M16A-1/22, Mitchell M16/22, Mitchell CAR-15/2 theb they wnet boom qand that was the end ysy |

|||

ArmaLite sold its rights to the AR-15 to Colt in 1959.<ref>Dockery, Kevin ''Future Weapons'', p. 96. Berkley Books, 2007.</ref> The AR-15 was first adopted in 1962 by the [[United States Air Force]], ultimately receiving the designation ''M16''. The U.S. Army began to field the ''XM16E1'' en masse in 1965 with most of them going to the [[Republic of Vietnam]], and the newly organized and experimental [[Airmobile]] Divisions, the [[1st Air Cavalry Division]] in particular. The U.S. Marine Corps in South Vietnam also experimented with the M16 rifle in combat during this period. This occurred in the early 1960s, with the Army issuing it in late 1964.<ref name=Venola>{{Cite journal |last1=Venola |first=Richard |title=What a Long Strange Trip It's Been |journal=Book of the AR-15 |volume=1 |issue=2 |year=2005 |pages=6–18 |ref=harv}}</ref> Commercial AR-15s were first issued to Special Forces troops in spring of 1964.<ref>{{Cite book |first=Daniel |last=Ford |title=The Only War We've Got: Early Days in South Vietnam |year=2001 |isbn=978-0-595-17551-2 |url=http://books.google.com/?id=sV_K3L6hTqEC}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:M16A1 PVS-2.JPEG|right|thumb|The XM16E1 is seen here fitted with an AN/PVS-2 night vision scope.]] |

|||

The first issues of the rifle generated considerable controversy because the gun suffered from a jamming flaw known as "failure to extract", which meant that a spent cartridge case remained lodged in the chamber after a bullet was fired.<ref name=Reliable>{{cite journal |author=C.H. Chivers |title= How Reliable is the M16 Rifle? |journal=[[New York Times]] |date=2 November 2009 |url=http://atwar.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/11/02/how-reliable-is-the-m-16-rifle/ |ref=harv}}</ref> According to a congressional report, the jamming was caused primarily by a change in gunpowder that was done without adequate testing and reflected a decision for which the safety of soldiers was a secondary consideration, away from what the designer specified, as well as telling troops the rifle was 'self cleaning' and at times failing to issue cleaning kits.<ref>{{cite book |author=David Maraniss |title=They Marched Into Sunlight: War and Peace Vietnam and America October 1967 |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=qftwHKSnmpkC|year=2003 |publisher=Simon and Schuster |isbn=978-0-7432-6255-2 |page=[http://books.google.com/books?id=qftwHKSnmpkC&pg=PA410 410]}}</ref> Due to the issue, reports of soldiers being wounded were directly linked to the M16, which many soldiers felt was unreliable compared to its precursor, the M14, which used [[stick powder]], varying from the M16's utilization of [[ball powder]]. |

|||

[[File:M40 gasmask.jpg|thumb|left|A U.S. soldier on NBC exercise, holding an M16A1 rifle and wearing an [[M40 Field Protective Mask]]. Note the receiver, [[forward assist]] and the barrel flash suppressor.]] |

|||

The Army standardized an upgrade of the XM16E1 as the ''M16A1'' in 1967. All of the early versions were chambered to fire the M193/M196 cartridges in the [[Semi-automatic firearm|semi]]-automatic and the [[Automatic firearm|automatic]] firing modes. The M16A1 version remained the primary infantry rifle of U.S. forces in South Vietnam until the end of direct U.S. ground involvement in 1973, and remained with all U.S. military ground forces after it had replaced the [[M14 rifle|M14]] [[service rifle]] in 1970 in [[CONUS]], Europe (Germany), and South Korea; when it was supplemented by the ''M16A2''. During the early 1980s, a roughly standardized load for this ammunition was adopted throughout [[NATO]].{{citation needed|date=April 2015}} |

|||

The M16A2 rifle entered service in the 1980s, being ordered in large scale by 1987, chambered to fire the standard [[NATO]] cartridge, the Belgian-designed M855/M856. The M16A2 is a select-fire rifle (semi-automatic fire, three-round-burst fire) incorporating design elements requested by the Marine Corps: an adjustable, windage rear-sight; a stock {{convert|5/8|in|mm|sigfig=3}} longer; heavier barrel; case deflector for left-hand shooters; and cylindrical handguards.<ref name=Venola/> The fire mode selector is on the receiver's left side. M16A2s are still in stock with the U.S. Army and Marine Corps, but are used primarily by reserve and National Guard units as well as by the U.S. Air Force and U.S. Coast Guard.{{Citation needed|date=November 2009}} |

|||

The M16A3 rifle is an M16A2 rifle with an M16A1's fire control group (semi-automatic fire, automatic fire) that is used only by the U.S. Navy.{{Citation needed |date=June 2013}} |

|||

The M16A4 rifle was standard issue for the [[United States Marine Corps]] in [[Iraq War|Operation Iraqi Freedom]] after 2004 and replaced the M16A2 in front line units.<ref name=Green2004>{{cite book|author=Michael Green|title=Weapons of the Modern Marines|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=pb5Y2bnujhwC&pg=PA17|accessdate=6 June 2013|date=January 2004|publisher=Zenith Imprint|isbn=978-1-61060-776-6|page=17}}</ref> In the U.S. Army, the M16A2 rifle is being supplemented with two rifle models, the M16A4 and the [[M4 carbine]], as the standard issue assault rifle. The M16A4 has a flat-top receiver developed for the M4 carbine, a handguard with four [[Picatinny rail]]s for mounting a sight, [[laser]], [[night vision device]], forward handgrip, M203 grenade launcher, removable handle, or a flashlight. |

|||

The M16 rifle is principally manufactured by [[Colt Firearms|Colt]] and [[Fabrique Nationale de Herstal]] (under a U.S. military contract since 1988 by FNH-USA; currently in production since 1991, primarily M16A2, A3, and A4), with variants made elsewhere in the world. Versions for the U.S. military have also been made by [[H & R Firearms]]<ref>[http://www.hr1871.com/about/ H&R About Us page]. hr1871.com</ref> [[General Motors]] [[Hydramatic]] Division<ref>[http://www.thegunzone.com/556dw-5.html The Gun Zone].</ref> and most recently by [[Sabre Defence]].<ref>[http://www.defensereview.com/sabre-defence-industries-awarded-m16-rifle-contract-m16a3-m16a4-rifles/ Sabre Defence Industries Awarded M16 Rifle Contract].</ref> Semi-automatic versions of the AR-15 are popular recreational shooting rifles, with versions manufactured by other small and large manufacturers in the U.S.<ref>[http://www.ar-15.us/AR15_Manufacturers.php AR15 Manufacturers & Builders].</ref> The M16 rifle design, including variant or modified version of it such as the [[Armalite]]/Colt [[AR-15]] series, AAI M15 rifle; AP74; EAC J-15; SGW XM15A; any 22-caliber rimfire variant, including the Mitchell M16A-1/22, Mitchell M16/22, Mitchell CAR-15/22, and AP74 Auto Rifle, is a prohibited and restricted weapon in Canada.<ref>[http://www.canlii.org/en/ca/laws/regu/sor-98-462/latest/sor-98-462.html Regulations Prescribing Certain Firearms and other Weapons, Components and Parts of Weapons, Accessories, Cartridge Magazines, Ammunition and Projectiles as Prohibited or Restricted, SOR/98-462]. Canlii. 29 June 2010</ref> |

|||

==History== |

==History== |

||

Revision as of 02:33, 3 June 2015

| Rifle, 5.56 mm, M16 | |

|---|---|

From top to bottom: M16A1, M16A2, M4A1, M16A4 | |

| Type | Assault rifle |

| Place of origin | United States |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1962–present |

| Used by | See Users |

| Wars | Vietnam War Laotian Civil War Cambodian Civil War The Troubles Cambodian–Vietnamese War 1982 Lebanon War Invasion of Grenada South Lebanon conflict (1985–2000) Bougainville Civil War[1] United States invasion of Panama Oka Crisis[2] Gulf War Somali Civil War Yugoslav Wars Operation Deny Flight Operation Joint Endeavor War in Afghanistan Iraq War Libyan Civil War Syrian Civil War Gaza–Israel conflict 2014 pro-Russian unrest in Ukraine Several other conflicts |

| Production history | |

| Designer | Eugene Stoner and L. James Sullivan[3] |

| Designed | 1956[4] |

| Manufacturer | |

| Produced | 1959–present[4] |

| No. built | ~8 million[5] |

| Variants | See Variants |

| Specifications (M16) | |

| Mass | 7.18 lb (3.26 kg) (unloaded) 8.79 lb (4.0 kg) (loaded) |

| Length | 39.5 in (1,000 mm) |

| Barrel length | 20 in (508 mm) |

| Cartridge | 5.56×45mm NATO |

| Caliber | 5.56mm |

| Action | Gas-operated, rotating bolt (direct impingement) |

| Rate of fire | 12–15 rounds/min sustained 45–60 rounds/min semi-automatic 700–950 rounds/min cyclic |

| Muzzle velocity | 3,110 ft/s (948 m/s)[6] |

| Effective firing range | 600 meters (point target)[7] 800 meters (area target)[8] |

| Feed system | 20-round detachable box magazine: (0.211 lb [95 grams] empty / 0.738 lb [335 g] full) 30-round detachable box magazine: (0.257 lb [117 g] empty / 1.06 lb [483 g] full) Beta C-Mag 100-round double-lobed drum: (2.2 lb [1 kg] empty / 4.81 lb [2.19 kg] full) |

| Sights | Iron sights |

The M16 rifle, officially designated Rifle, Caliber 5.56 mm, M16, is a United States military adaptation of the AR-15 rifle. [n 1] The M16 fires the 5.56×45mm NATO cartridge. The rifle entered United States Army service and was deployed for jungle warfare operations in South Vietnam in 1963,[11] becoming the U.S. military's standard service rifle of the Vietnam War by 1969,[12] replacing the M14 rifle in that role. The U.S. Army retained the M14 in CONUS, Europe, and South Korea until 1970. In 1983 with the USMC's adoption of the M16A2 (1986 for the U.S. Army), the M16 rifle was modified for three-round bursts,[13] with some later variants having all modes of fire and has been the primary service rifle of the U.S. armed forces.

The M16 has also been widely adopted by other militaries around the world. Total worldwide production of M16s has been approximately 8 million, making it the most-produced firearm of its 5.56 mm caliber.[14] The U.S. Army has largely replaced the M16 in combat units with the M4 carbine, which is a smaller version of the AR-15.[15]

Overview

The M16 is a lightweight, 5.56 mm, air-cooled, gas-operated, magazine-fed assault rifle, with a rotating bolt, actuated by direct impingement gas operation. The rifle is made of steel, 7075 aluminum alloy, composite plastics and polymer materials.

ArmaLite sold its righ-contract-m16a3-m16a4-rifles/ Sabre Defence Industries Awarded M16 Rifle Contract].</ref> Semi-automatic versions of the AR-15 are popular recreational shooting rifles, with versions manufactured by other small and large manufacturers in the U.S.[16] The M16 rifle design, including variant or modified version of it such as the Armalite/Colt AR-15 series, AAI M15 rifle; AP74; EAC J-15; SGW XM15A; any 22-caliber rimfire variant, including the Mitchell M16A-1/22, Mitchell M16/22, Mitchell CAR-15/2 theb they wnet boom qand that was the end ysy

History

Project SALVO

In 1948, the U.S. Army organized the civilian Operations Research Office, mirroring similar operations research organizations in the United Kingdom. One of their first efforts, Project ALCLAD, studied body armor and the conclusion was that they would need to know more about battlefield injuries in order to make reasonable suggestions. Over 3 million battlefield reports from World War I and World War II were analyzed and over the next few years they released a series of reports on their findings.[18]

The conclusion was that most combat takes place at short range. In a highly mobile war, combat teams ran into each other largely by surprise; and the team with the greater firepower tended to win. They also found that the chance of being hit in combat was essentially random; accurate "aiming" made little difference because the targets no longer sat still. The number one predictor of casualties was the total number of rounds fired.[18] Other studies of behavior in battle revealed that many U.S. infantrymen (as many as two-thirds) never actually fired their rifles in combat. By contrast, soldiers armed with rapid fire weapons were much more likely to have fired their weapons in battle.[19] These conclusions suggested that infantry should be equipped with a fully automatic rifle of some sort in order to increase the actual firepower of regular soldiers. It was also clear, however, that such weapons dramatically increased ammunition use and in order for a rifleman to be able to carry enough ammunition for a firefight he would have to carry something much lighter.[citation needed]

Existing rifles met none of these criteria. Although it appeared the new 7.62 mm T44 (precursor to the M14) would increase the rate of fire, its heavy 7.62 mm NATO cartridge made carrying significant quantities of ammunition difficult. Moreover, the length and weight of the weapon made it unsuitable for short range combat situations often found in jungle and urban combat or mechanized warfare, where a smaller and lighter weapon could be brought to bear faster.[citation needed]

These efforts were noticed by Colonel René Studler, U.S. Army Ordnance's Chief of Small Arms Research and Development. Col. Studler asked the Aberdeen Proving Ground to submit a report on the smaller caliber weapons. A team led by Donald Hall, director of program development at Aberdeen, reported that a .22 inch (5.56 mm) round fired at a higher velocity would have performance equal to larger rounds in most combat.[20] With the higher rate of fire possible due to lower recoil it was likely such a weapon would inflict more casualties on the enemy. His team members, notably William C. Davis, Jr. and Gerald A. Gustafson, started development of a series of experimental .22 (5.56 mm) cartridges. In 1955, their request for further funding was denied.[citation needed]

A new study, Project SALVO, was set up to try to find a weapon design suited to real-world combat. Running between 1953 and 1957 in two phases, SALVO eventually suggested that a weapon firing four rounds into a 20-inch (508 mm) area would double the hit probability of existing semi-automatic weapons.[citation needed]

In the second phase, SALVO II, several experimental weapons concepts were tested. Irwin Barr of AAI Corporation introduced a series of flechette weapons, starting with a shotgun shell containing 32 darts and ending with single-round flechette "rifles". Winchester and Springfield Armory offered multiple barrel weapons, while ORO's own design used two .22, .25 or .27 caliber bullets loaded into a single .308 Winchester or .30-06 cartridge.[citation needed]

Eugene Stoner

Meanwhile testing of the 7.62 mm T44 continued, and Fabrique Nationale also submitted their new FN FAL via the American firm Harrington & Richardson as the T48. The T44 was selected as the new battle rifle for the U.S. Army (rechristened the M14) despite a strong showing by the T48.[21]

In 1954, Eugene Stoner of the newly formed ArmaLite helped develop the 7.62 mm AR-10.[10] Springfield's T44 and similar entries were conventional rifles using wood for the "furniture" and otherwise built entirely of steel using mostly forged and machined parts. ArmaLite was founded specifically to bring the latest in designs and alloys to firearms design, and Stoner felt he could easily beat the other offerings.

The AR-10's receiver was made of forged and milled aluminum alloy instead of steel. The barrel was mated to the receiver by a separate hardened steel extension to which the bolt locked. This allowed a lightweight aluminum receiver to be used while still maintaining a steel-on-steel lockup. The bolt was operated by high-pressure combustion gases taken from a hole in the middle of the barrel directly through a tube above the barrel to a cylinder created in the bolt carrier with the bolt carrier itself acting as a piston. Traditional rifles located this cylinder and piston close to the gas vent. The stock and grips were made of a glass-reinforced plastic shell over a rigid foam plastic core. The muzzle brake was fabricated from titanium. Over Stoner's objections, various experimental composite and 'Sullaloy' aluminum barrels were fitted to some AR-10 prototypes by ArmaLite's president, George Sullivan. The Sullaloy barrel was made entirely of heat-treated aluminum, while the composite barrels used aluminum extruded over a thin stainless steel liner.

Meanwhile, the layout of the weapon itself was also somewhat different. Previous designs generally placed the sights directly on the barrel, using a bend in the stock to align the sights at eye level while transferring the recoil down to the shoulder. This meant that the weapon tended to rise when fired, making it very difficult to control during fully automatic fire. The ArmaLite team used a solution previously used on weapons such as the German FG 42 and Johnson light machine gun; they located the barrel in line with the stock, well below eye level, and raised the sights to eye level. The rear sight was built into a carrying handle over the receiver.

Despite being over 2 lb (0.91 kg) lighter than the competition, the AR-10 offered significantly greater accuracy and recoil control. Two prototype rifles were delivered to the U.S. Army's Springfield Armory for testing late in 1956. At this time, the U.S. armed forces were already two years into a service rifle evaluation program, and the AR-10 was a newcomer with respect to older, more fully developed designs. Over Stoner's continued objections, George Sullivan had insisted that both prototypes be fitted with composite aluminum/steel barrels. Shortly after a composite barrel burst on one prototype in 1957, the AR-10 was rejected. The AR-10 was later produced by a Dutch firm, Artillerie Inrichtingen, and saw limited but successful military service with several foreign nations such as Sudan, Guatemala, and Portugal. Portugal deployed a number of AR-10s for use by its airborne (Caçadores Pára-quedista) battalions, and the rifle saw considerable combat service in Portugal's counter-insurgency campaigns in Angola and Mozambique.[22] Some AR-10 rifles were still in service with airborne forces serving during the withdrawal from Portuguese Timor in 1975.

CONARC

In 1957, a copy of Gustafson's funding request from 1955 found its way into the hands of General Willard G. Wyman, commander of the U.S. Continental Army Command. He immediately put together a team to develop a .223 caliber (5.56 mm) weapon for testing. Their finalized request called for a select-fire weapon of 6 pounds (2.7 kg) when loaded with 20 rounds of ammunition. The bullet had to penetrate a standard U.S. steel helmet, body armor, or a steel plate of 0.135 inches (3.4 mm) and retain a velocity in excess of the speed of sound at 500 yards (460 m), while equaling or exceeding the "wounding" ability of the .30 Carbine.[18][23]

Wyman had seen the AR-10 in an earlier demonstration, and impressed by its performance he personally suggested that ArmaLite enter a weapon for testing using a 5.56 mm cartridge designed by Winchester.[18] Their first design, using conventional layout and wooden furniture, proved to be too light. When combined with a conventional stock, recoil was excessive in fully automatic fire. Their second design was simply a scaled-down AR-10, and immediately proved much more controllable. Winchester entered the LMR,[24] a design based loosely on their M1 carbine, and Earle Harvey of Springfield attempted to enter a design, but was overruled by his superiors at Springfield, who refused to divert resources from the T44. In the end, ArmaLite's AR-15 had no competition. The lighter round allowed the rifle to be scaled down, and was smaller and lighter than the previous AR-10. The AR-15 weighed only around 5.5 pounds (2.5 kg) empty, and 6 pounds (2.7 kg) loaded (with a 20-round magazine).

During testing in March 1958, rainwater caused the barrels of both the ArmaLite and Winchester rifles to burst, causing the Army to once again press for a larger round, this time at 0.258 in (6.6 mm). Nevertheless, they suggested continued testing for cold-weather suitability in Alaska. Stoner was later asked to fly in to replace several parts, and when he arrived he found the rifles had been improperly reassembled. When he returned he was surprised to learn that they too had rejected the design even before he had arrived; their report also endorsed the 0.258 in (6.6 mm) round. After reading these reports, General Maxwell Taylor became dead-set against the design, and pressed for continued production of the M14.

Not all the reports were negative. In a series of mock-combat situations testing the AR-15, M14 and AK-47, the Army found that the AR-15's small size and light weight allowed it to be brought to bear much more quickly, just as CONARC had suggested. Their final conclusion was that an 8-man team equipped with the AR-15 would have the same firepower as a current 11-man team armed with the M14. U.S. troops were able to carry more than twice as much 5.56×45mm ammunition as 7.62×51mm for the same weight, which would allow them a greater advantage against a typical NVA unit armed with AK-47s.

At this point, Fairchild had spent $1.45 million in development expenses, and wished to divest itself of its small-arms business. Fairchild sold production rights for the AR-15 to Colt Firearms in December 1959, for only $75,000 cash and a 4.5% royalty on subsequent sales; Robert W. MacDonald of Cooper-MacDonald got a finder's fee of $250,000 and a 1% royalty for arranging the deal.[25] In 1960, ArmaLite was reorganized, and Stoner left the company.

M16 adoption

The first orders of the AR15 were by the Federation of Malaya on September 30, 1959,[26] with India[27][28] also obtaining some for testing with a view of adopting them.

U.S. Air Force General Curtis LeMay viewed a demonstration of the AR-15 in July 1960. In the summer of 1961, General LeMay had been promoted to the position of USAF Chief of Staff, and requested an order of 80,000 AR-15s for the U.S. Air Force. However, under the recommendation of General Maxwell D. Taylor, who advised the Commander in Chief that having two different calibers within the military system at the same time would be problematic, President Kennedy turned down the request.[29] However, Advanced Research Projects Agency, which had been created in 1958 in response to the Soviet Sputnik program, embarked on project AGILE in the spring of 1961. AGILE's priority mission was to devise inventive fixes to the communist problem in South Vietnam. In October 1961, William Godel, a senior man at ARPA, sent 10 AR-15s to South Vietnam to let the allies test them. The reception was enthusiastic, and in 1962 another 1,000 AR-15s were sent to South Vietnam.[30] Special Operations units and advisers working with the South Vietnamese troops filed battlefield reports lavishly praising the AR-15 and the stopping effectiveness of the 5.56 mm cartridge, and pressed for its adoption. However, what no one knew, except the men directly using the AR-15s in Vietnam, were the devastating kills made by the new rifle, photographs of which, showing enemy casualties made by the .223 (5.56 mm) bullet remained classified into the 1980s.[31]

The damage caused by the .223 in (5.56 mm) "varmint"[29] bullet was observed and originally believed to be caused by "tumbling" due to the slow 1 in 14-inch (360 mm) rifling twist rate. However, this twist rate only made the bullet less stable in air. Any pointed lead core bullet will turn base over point ("tumble") after penetration in flesh, because the center of gravity is aft of the center of pressure. The large wounds observed by soldiers in Vietnam were actually caused by projectile fragmentation, which was created by a combination of the projectile's velocity and construction.[32]

U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara now had two conflicting views: the ARPA report favoring the AR-15 and the Pentagon's position on the M14. Even President John F. Kennedy expressed concern, so McNamara ordered Secretary of the Army Cyrus Vance to test the M14, the AR-15 and the AK-47. The Army's test report stated that only the M14 was suitable for Army use, but Vance wondered about the impartiality of those conducting the tests. He ordered the Army Inspector General to investigate the testing methods used; the Inspector General confirmed that the testers showed favor to the M14.

Secretary Robert McNamara ordered a halt to M14 production in January 1963, after receiving reports that M14 production was insufficient to meet the needs of the armed forces. Secretary McNamara had long been a proponent of weapons program consolidation among the armed services. At the time, the AR-15 was the only rifle that could fulfill a requirement of a "universal" infantry weapon for issue to all services. McNamara ordered the weapon be adopted unmodified, in its current configuration, for immediate issue to all services, despite receiving reports noting several deficiencies with the M16 as a service rifle, including the lack of a chrome-lined bore and chamber, the 5.56 mm projectile's instability under arctic conditions,[33] and the fact that large quantities of 5.56 mm ammunition required for immediate service were not available.[citation needed] In addition, the Army insisted on the inclusion of a forward assist to help push the bolt into battery in the event that a cartridge failed to seat in the chamber through fouling or corrosion. Colt had argued the rifle was a self-cleaning design, requiring little or no maintenance. Colt, Eugene Stoner, and the U.S. Air Force believed that a forward assist needlessly complicated the rifle, adding about $4.50 to its procurement cost with no real benefit. As a result, the design was split into two variants: the Air Force's M16 without the forward assist, and, for the other service branches, the XM16E1 with the forward assist.

In November 1963, McNamara approved the U.S. Army's order of 85,000 XM16E1s for jungle warfare operations;[34] and to appease General LeMay, the Air Force was granted an order for another 19,000 M16s.[18][35] Meanwhile, the Army carried out another project, the Small Arms Weapons Systems, on general infantry firearm needs in the immediate future. They recommended the immediate adoption of the weapon. Later that year the Air Force officially accepted their first batch as the United States Rifle, Caliber 5.56 mm, M16.

The Army immediately began to issue the XM16E1 to infantry units. However, the rifle was initially delivered without adequate cleaning supplies or instructions and so, when the M16 reached Vietnam with U.S. troops in March 1965, reports of stoppages in combat began to surface. Often the rifle suffered from a stoppage known as "failure to extract", which meant that a spent cartridge case remained lodged in the chamber after a bullet flew out the muzzle.[36] Although the M14 featured a chrome-lined barrel and chamber to resist corrosion in combat conditions, neither the bore nor the chamber of the M16/XM16E1 was chrome-lined. Several documented accounts of troops killed by enemy fire with inoperable rifles broken-down for cleaning eventually brought a Congressional investigation.[37]

"We left with 72 men in our platoon and came back with 19, Believe it or not, you know what killed most of us? Our own rifle. Practically every one of our dead was found with his [M16] torn down next to him where he had been trying to fix it."

— Marine Corps Rifleman, Vietnam.[37]

The root cause of the stoppages turned out to be a problem with the powder in the ammunition. In 1964, when the Army was informed that DuPont could not mass-produce the nitrocellulose-based IMR 4475 powder to the specifications demanded by the M16, the Olin Mathieson Company provided a high-performance ball propellant of nitrocellulose and nitroglycerin. While the Olin WC 846 powder was capable of firing an M16 5.56 mm round at the desired 3,300 ft (1,000 m) per second, the powder produced higher chamber and gas port pressures with the unintended consequence of increasing the automatic rate of fire from 850 to 1,000 rounds per minute.[39] That problem was resolved by fitting the M16 with a buffer system, reducing the rate of fire back to 850 rounds per minute, and outfitting all newly produced M16s with an anti-corrosive chrome-plated chamber.[40] Dirty residue left by WC 846 made the M16 more likely to have a stoppage. Some WC 846 propellant lots clogged the M16 gas tube until concentrations of calcium carbonate stabilizers were reduced in 1970 as reformulated WC 844.[41]

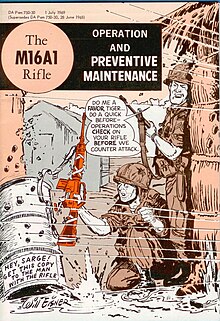

On 28 February 1967, the XM16E1 was standardized as the M16A1. Major revisions to the design followed. The rifle was given a chrome-lined chamber (later, the entire bore) to eliminate corrosion and stuck cartridges, and the rifle's recoil mechanism was re-designed to accommodate Army-issued 5.56 mm ammunition. Rifle cleaning tools and powder solvents/lubricants were issued. Intensive training programs in weapons cleaning were instituted including a comic book-style manual in 1968 and 1969, DA PAM 750-30, to demonstrate proper maintenance.[42][43] The reliability problems of the M16 diminished quickly, although the rifle's reputation continued to suffer.[18]

According to a February 1968 Department of Defense report, the M16 rifle achieved widespread acceptance by U.S. troops in Vietnam. Only 38 of 2,100 individuals queried wanted to replace the M16 with another weapon. Of those 38, 35 wanted the CAR-15 (a shorter version of the M16) instead.[44]

SPIW

The M16 and the 5.56×45 mm cartridge were initially adopted by U.S. infantry forces as interim solutions to address the weight and control issues experienced with the 7.62×51mm round and M14 rifle. In the late 1950s, future small arms development was pursued through the Special Purpose Individual Weapon program. The SPIW effort sought to replace cased bullets with flechette projectiles fired from sabots. Rifles firing the sabots would have a muzzle velocity of 1,200 metres per second (3,900 ft/s) to 1,500 metres per second (4,900 ft/s) to give a short flight time and flat trajectory. At those speeds, factors like range, wind drift, and target movement would no longer affect performance. Several manufacturers offered many different gun designs, from traditional wooden models to ones made of lightweight "space age" materials similar to the M16, to bullpups, and even multi-barrel weapons with drum magazines. [citation needed] All used similar ammunition firing a 1.8 mm diameter dart with a plastic "puller" sabot filling the case mouth. While the flechette ammunition had excellent armor penetration, there were doubts about their terminal effectiveness against unprotected targets. Conventional cased ammunition was more accurate and the sabots were expensive to produce. The SPIW program never created an infantry rifle that would be combat effective, and development was fully abandoned in the early 1970s. With the end of the program, the "temporary" M16, with the 5.56×45mm round, was retained as the standard U.S. infantry rifle.[45]

NATO standards

In March 1970, the U.S. stated that all NATO forces should eventually adopt the 5.56x45mm cartridge. This shift represented a change in the philosophy of the military's long-held position about caliber size. By the mid-1970s, other armies were also looking at M16-style weapons. A NATO standardization effort soon started, and tests of various rounds were carried out starting in 1977. The U.S. offered their original 5.56×45mm design, the M193, with no modifications, but there were concerns about its penetration in the face of the wider introduction of body armor. In the end, the Belgian 5.56×45mm SS109 round was chosen (STANAG 4172). This round was based on the U.S. cartridge, but included a new 62 grain bullet design with a small steel tip added to improve penetration. The U.S. Marine Corps was first to adopt the round with the M16A2, introduced in 1982. This was to become the standard U.S. military rifle. The NATO 5.56×45mm standard ammunition produced for U.S. forces is designated M855.

Shortly after, in October 1980, NATO accepted the 5.56x45mm NATO rifle cartridge.[46] Draft Standardization Agreement 4179 (STANAG 4179) was proposed to allow the military services of member nations to easily share rifle ammunition and magazines during operations, at the individual soldier level, in the interest of easing logistical concerns. The magazine chosen to become the STANAG magazine was originally designed for the U.S. M16 rifle. Many NATO member nations, but not all, subsequently developed or purchased rifles with the ability to accept this type of magazine. However, the standard was never ratified and remains a 'Draft STANAG'.[47]

The NATO Accessory Rail STANAG 4694, or Picatinny rail STANAG 2324, or a "Tactical Rail" is a bracket used on M16 type rifles to provide a standardized mounting platform. The rail comprises a series of ridges with a T-shaped cross-section interspersed with flat "spacing slots". Scopes are mounted either by sliding them on from one end or the other; by means of a "rail-grabber" which is clamped to the rail with bolts, thumbscrews or levers; or onto the slots between the raised sections. The rail was originally for scopes. However, once established, the use of the system was expanded to other accessories, such as tactical lights, laser aiming modules, night vision devices, reflex sights, foregrips, bipods, and bayonets.

Currently, the M16 is in use by 15 NATO countries and more than 80 countries world wide.

Reliability

The M16 rifle series has had questionable reliability performance since its introduction. Intense criticism began in 1966, when soldiers and Marines in Vietnam reported that their rifles would jam during firefights. The worst malfunction was failure to extract, where a spent cartridge case remained lodged in the chamber after a round was fired. The only way to dislodge the case was to push a metal rod down the muzzle to force the case out, which took valuable time away from returning fire. In 1967, a then-classified Army report showed that out of 1,585 troops questioned in a survey, 80 percent (1,268 troops) experienced a stoppage while firing. This occurred while the Army insisted to the public that the M16 was the best rifle available for fighting in Vietnam. A 1967 Congressional subcommittee investigation found the Army failed to ensure the weapon and ammunition worked well together, failed to train troops on the new weapon, and neglected to issue enough cleaning equipment, including a cleaning rod to clear jammed rifles. Most problems were remedied with the issuing of the M16A1.[36]

In December 2006, the Center for Naval Analyses released a report on U.S. small arms in combat. The CNA conducted surveys on 2,608 troops returning from combat in Iraq and Afghanistan over the past 12 months. Only troops who fired their weapons at enemy targets were allowed to participate. 1,188 troops were armed with M16A2 or A4 rifles, making up 46 percent of the survey. 75 percent of M16 users (891 troops) reported they were satisfied with the weapon. 60 percent (713 troops) were satisfied with handling qualities such as handguards, size, and weight. Of the 40 percent dissatisfied, most were with its size. Only 19 percent of M16 users (226 troops) reported a stoppage, while 80 percent of those that experienced a stoppage said it had little impact on their ability to clear the stoppage and re-engage their target. Half of the M16 users never experienced failures of their magazines to feed. 83 percent (986 troops) did not need their rifles repaired while in theater. 71 percent (843 troops) were confident in the M16's reliability, defined as level of soldier confidence their weapon will fire without malfunction, and 72 percent (855 troops) were confident in its durability, defined as level of soldier confidence their weapon will not break or need repair. Both factors were attributed to high levels of soldiers performing their own maintenance. 60 percent of M16 users offered recommendations for improvements. Requests included greater bullet lethality, new-built rifles instead of rebuilt, better quality magazines, decreased weight, and a collapsible stock. Some users recommended shorter and lighter weapons similar to the M4 Carbine, or to simply be issued with the M4.[48] Some issues have been addressed with the issuing of the Improved STANAG magazine in March 2009,[49][50] and the M855A1 Enhanced Performance Round in June 2010.[51]

In early 2010, two journalists from the New York Times spent three months with soldiers and Marines in Afghanistan. While there, they questioned around 100 infantrymen about the reliability of their M16 rifles, as well as the M4 Carbine. Surprisingly, troops did not report to be suffering reliability problems with their rifles. While only 100 troops were asked, they fought at least a dozen intense engagements in Helmand Province, where the ground is covered in fine powdered sand (called "moon dust" by troops) that can stick to firearms. Weapons were often dusty, wet, and covered in mud. Intense firefights lasted hours with several magazines being expended. Only one soldier reported a jam when his M16 was covered in mud after climbing out of a canal. The weapon was cleared and resumed firing with the next chambered round. Furthermore, a Marine Chief Warrant Officer reported that with his battalion's 350 M16s and 700 M4s, they've had no issues.[52]

Design

The M16's receivers are made of 7075 aluminum alloy, its barrel, bolt, and bolt carrier of steel, and its handguards, pistol grip, and buttstock of plastics. Early models were especially lightweight at 6.5 pounds (2.9 kg) without magazine and sling. This was significantly less than older 7.62 mm "battle rifles" of the 1950s and 1960s. It also compares with the 6.5 pounds (2.9 kg) AKM without magazine.[53] M16A2 and later variants (A3 & A4) weigh more (8.5 lb (3.9 kg) loaded) because of the adoption of a thicker barrel profile. The thicker barrel is more resistant to damage when handled roughly and is also slower to overheat during sustained fire. Unlike a traditional "bull" barrel that is thick its entire length, the M16A2's barrel is only thick forward of the handguards. The barrel profile under the handguards remained the same as the M16A1 for compatibility with the M203 grenade launcher. The rifle is the same length as the M16A1.

The rifling twist of early model M16 barrels had 4 grooves, right hand twist, 1 turn in 14 inches (1:355.6 mm) bore - as it was the same rifling used by the .222 Remington sporting round. This was shown to make the light .223 Remington bullet yaw in flight at long ranges and it was soon replaced. Later models had an improved rifling with 6 grooves, right hand twist, 1 turn in 12 inches (1:304.8 mm) for increased accuracy and was optimized for use with the standard U.S. M193 cartridge. Current models are optimized for the heavier NATO SS109 bullet and have 6 grooves, right hand twist, 1 turn in 7 in (1:177.8 mm).[54][55][56][57] Weapons designed to accept both the M193 or SS109 rounds (like civilian market clones) have a 6-groove, right hand twist, 1 turn in 9 inches (1:228.6 mm) bore.

The M16's most distinctive ergonomic feature is the carrying handle and rear sight assembly on top of the receiver. This is a by-product of the original design, where the carry handle served to protect the charging handle.[58] As the line of sight is 2.5 in (63.5 mm) over the bore, the M16 has an inherent parallax problem. At closer ranges (typically inside 15–20 meters), the shooter must aim high in order to place shots where desired. The M16 has a 500 mm (19.75 inches) sight radius.[59] The M16 uses an L-type flip, aperture rear sight and it is adjustable with two settings, 0 to 300 meters and 300 to 400 meters.[60] The front sight is a post adjustable for elevation in the field. The rear sight can be adjusted in the field for windage. The sights can be adjusted with a bullet tip and soldiers are trained to zero their own rifles. The sight picture is the same as the M14, M1 Garand, M1 Carbine and the M1917 Enfield. The M16 also has a "Low Light Level Sight System", which includes a front sight post with a small glass vial of (glow-in-the-dark) radioactive Tritium H3 and a larger aperture rear sight.[61] The M16A4 can mount a scope on the carrying handle. With the advent of the M16A2, a new fully adjustable rear sight was added, allowing the rear sight to be dialed in for specific range settings between 300 and 800 meters and to allow windage adjustments without the need of a tool or cartridge.[62] Modern versions of the M16 use a Picatinny rail, which allows the use of various scopes and sighting devices. The current United States Army and Air Force issue M4 Carbine comes with the M68 Close Combat Optic and Back-up Iron Sight.[63][64] The United States Marine Corps uses the ACOG Rifle Combat Optic[65][66] and the United States Navy uses EOTech Holographic Weapon Sight.[67]

Another unique design feature is its straight-line recoil design, where the recoil spring is located in the stock directly behind the action. This serves the dual function of operating spring and recoil buffer.[58] The stock being in line with the bore reduces muzzle rise, especially during automatic fire. Because the low recoil does not significantly shift the point of aim, faster follow-up shots are now much more possible and user fatigue is reduced.

The M16 utilizes direct impingement gas operation; high-pressure gas tapped from a port built near the front sight assembly travels through a tube in the upper handguard and exerts pressure on the bolt carrier mechanism, actuating the bolt. This reduces the number of moving parts by eliminating the need for a separate piston and cylinder and it provides better performance in rapid fire by lowering recoil through reduced mass of moving parts.[68]

The primary criticism of direct impingement is that fouling and debris from expended gunpowder is blown directly into the breech.[69] As the superheated gas travels down the tube, not only does it make the handguard become rather hot, it expands and cools. This cooling causes vaporized matter to condense depositing a much greater volume of solids into the operating components of the weapon.[70] The increased fouling can cause malfunctions if the rifle is not cleaned as frequently as it should be. The amount of sooting tends to vary with powder specification, caliber, and gas port design.

5.56 mm cartridge

The 5.56x45 mm cartridge originally developed by Armalite had several advantages over the 7.62x51 mm NATO round used in the M14 rifle. Most of these reasons were due to the dense and humid jungle in which U.S. soldiers were fighting during the Vietnam War. The 5.56 mm cartridge was developed as a shorter range alternative to the larger-caliber round used in M14 rifles; it also enabled each soldier to carry more ammunition. The recoil was also found easier to control during automatic or burst fire, developing the M16 into variants such as the M16A3 and M16A4.[71] The 5.56×45mm NATO cartridge can produce massive wounding effects when the bullet impacts at high speed and yaws ("tumbles") in tissue leading to fragmentation and rapid transfer of energy.[72][73][74] This produces wounds that were so devastating that the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and many countries[75] considered the M16 to be an inhumane weapon.[76][77]

The M193 55-grain round was used in early M16 and M16A1 rifles. The bullet tumbled and fragmented when it hit a soft target. With the development of the M16A2, the new M855 62-grain was adopted in 1983. The heavier bullet had more energy, and was made with a steel core to penetrate Soviet body armor. However, this caused less fragmentation on impact and reduced effects against targets without armor, both of which lessened kinetic energy transfer and wounding ability.[36] Some soldiers and Marines coped with this through training, with requirements to shoot vital areas three times to guarantee killing the target.[78] In June 2010, the U.S. Military began issuing the 62-grain M855A1 Enhanced Performance Round (EPR). The bullet had a solid copper core to eliminate lead contamination, and a steel penetrator tip. The EPR has better hard target penetration than 7.62 mm NATO ball, while also performing more consistently against soft targets than the M855. While the M855A1 was made to give better performance out of the shorter barrel of the M4 Carbine, it gives enhanced performance from the full-length M16 barrel.[51][79]

Magazines

The M16's magazine was meant to be a lightweight, disposable item.[80] As such, it was made of pressed/stamped aluminum and was not designed to be durable.[81] As a result, the magazine follower tended to rock or tilt, causing malfunctions. The M16 originally used a 20-round straight magazine, which was later replaced by a bent 30-round design.[80]

The U.S. Military had adopted 30-round magazines with black followers, then updated magazines with green followers. In 2009, the U.S. military began fielding an "improved magazine" identified by a tan-colored follower.[82][83] "The new follower incorporates an extended rear leg and modified bullet protrusion for improved round stacking and orientation. The self-leveling/anti-tilt follower minimizes jamming while a wider spring coil profile creates even force distribution. The performance gains have not added weight or cost to the magazines."[83] Standard USGI aluminum 30-round M16 magazines weigh 3.9 oz (110 g) empty and are 7.1 inches (180 mm) long.[84][85]

Grips

Grips have changed through the various iterations of the M16 platform. These changes have been seen in more drastic detail as the rifle has moved into the civilian AR-15 market with its various aftermarket parts. Finger grooves as well as angle grip have been changed to accommodate the large variance in users hands as well as position of shooting. While military rifles will use smaller grips in an effort to accommodate smaller hands aftermarket grips often focus on a longer length of pull.[86]

Accessories

Muzzle devices

Most M16 rifles have a barrel threaded in 1⁄2-28" threads to incorporate the use of a muzzle device such as a flash suppressor or sound suppressor.[87] The initial flash suppressor design had three tines or prongs and was designed to preserve the shooter's night vision by disrupting the flash. Unfortunately it was prone to breakage and getting entangled in vegetation. The design was later changed to close the end to avoid this and became known as the "A1" or "bird cage" flash suppressor on the M16A1. Eventually on the M16A2 version of the rifle, the bottom port was closed to reduce muzzle climb and prevent dust from rising when the rifle was fired in the prone position.[21] For these reasons, the U.S. military declared the A2 flash suppressor as a compensator or a muzzle brake; but it is more commonly known as the "GI" or "A2" flash suppressor.[71]

The M16's Vortex Flash Hider weighs 3 ounces, is 2.25 inches long, and does not require a lock washer to attach to barrel.[88] It was developed in 1984, and is one of the earliest privately designed muzzle devices. The U.S. military uses the Vortex Flash Hider on M4 carbines and M16 rifles.[89][90] A version of the Vortex has been adopted by the Canadian Military for the Colt Canada C8 CQB rifle.[91] Other flash suppressors developed for the M16 include the Phantom Flash Suppressor by Yankee Hill Machine (YHM) and the KX-3 by Noveske Rifleworks.[92]

The threaded barrel allows sound suppressors with the same thread pattern to be installed directly to the barrel; however this can result in complications such as being unable to remove the suppressor from the barrel due to repeated firing on full auto or three-round burst.[93] A number of suppressor manufacturers such as Advanced Armament Corporation, Gemtech, Smith Enterprise, SureFire and OPS Inc. have turned to designing "direct-connect" sound suppressors which can be installed over an existing M16's flash suppressor as opposed to using the barrel's threads.[93]

Grenade launchers and shotguns

All current M16 type rifles are designed to fire STANAG (NATO standard) 22 mm rifle grenades from their integral flash hiders without the use of an adapter. These 22 mm grenade types range from anti-tank rounds to simple finned tubes with a fragmentation hand grenade attached to the end. They come in the "standard" type which are propelled by a blank cartridge inserted into the chamber of the rifle. They also come in the "bullet trap" and "shoot through" types, as their names imply, they use live ammunition. The U.S. military does not generally use rifle grenades; however, they are used by other nations.[94]

All current M16 type rifles can mount under-barrel 40 mm grenade-launchers, such as the M203 and M320. Both use the same 40 mm grenades as the older, stand-alone M79 grenade launcher. The M16 can also mount under-barrel 12 gauge shotguns such as KAC Masterkey or the M26 Modular Accessory Shotgun System.

Riot Control Launcher

The M234 Riot Control Launcher is an M16 series rifle attachment firing a M755 blank round. The M234 mounts on the muzzle, bayonet lug and front sight post of the M16. It fires either the M734 64 mm Kinetic Riot Control or the M742 64 mm CSI Riot Control Ring Airfoil Projectiles. The latter produces a 4 to 5 foot tear gas cloud on impact. The main advantage to using Ring Airfoil Projectiles is that their design does not allow them be thrown back by rioters with any real effect. The M234 is no longer used by United States forces. It has been replaced by the M203 40mm grenade launcher and nonlethal ammunition.

Variants

Pre-Production ArmaLite AR-15

The weapon that eventually became the M16 series was basically a scaled down AR-10 with an ambidextrous charging handle located within the carrying handle, a narrower front sight "A" frame, and no flash suppressor.[95]

AR-15 (Colt Models 601 & 602)

Colt's first two models produced after the acquisition of the rifle from ArmaLite were the 601 and 602, and these rifles were in many ways clones of the original ArmaLite rifle (in fact, these rifles were often found stamped Colt ArmaLite AR-15, Property of the U.S. Government caliber .223, with no reference to them being M16s).[96] The 601 and 602 are easily identified by their flat lower receivers without raised surfaces around the magazine well and occasionally green or brown furniture. The 601 was adopted first of any of the rifles by the USAF, and was quickly supplemented with the XM16 (Colt Model 602) and later the M16 (Colt Model 604) as improvements were made. There was also a limited purchase of 602s, and a number of both of these rifles found their way to a number of Special Operations units then operating in South East Asia, most notably the U.S. Navy SEALs. The only major difference between the 601 and 602 is the switch from the original 1:14-inch rifling twist to the more common 1:12-inch twist. These weapons were equipped with a triangular charging handle and a bolt hold open device that lacked a raised lower engagement surface. The bolt hold open device had a slanted and serrated surface that had to be engaged with a bare thumb, index finger, or thumb nail because of the lack of this surface.

The United States Air Force continued to use the AR-15 marked rifles in various configurations into the 1990s.

M16

Variant originally adopted by the U.S. Air Force. This was the first M16 adopted operationally. This variant had triangular handguards, butt stocks without a compartment for the storage of a cleaning kit,[97] a three-pronged flash suppressor, and no forward assist. Bolt carriers were originally chrome plated and slick-sided, lacking forward assist notches. Later, the chrome plated carriers were dropped in favor of Army issued notched and parkerized carriers though the interior portion of the bolt carrier is still chrome-lined. The Air Force continued to operate these weapons until around 2001, at which time the Air Force converted all of its M16s to the M16A2 configuration.

The M16 was also adopted by the British SAS, who used it during the Falklands War.[98]

XM16E1 and M16A1 (Colt Model 603)

The U.S. Army XM16E1 was essentially the same weapon as the M16 with the addition of a forward assist and corresponding notches in the bolt carrier. The M16A1 was the finalized production model in 1967.

To address issues raised by the XM16E1's testing cycle, a closed, bird-cage flash suppressor replaced the XM16E1's three-pronged flash suppressor which caught on twigs and leaves. Various other changes were made after numerous problems in the field. Cleaning kits were developed and issued while barrels with chrome-plated chambers and later fully lined bores were introduced.

With these and other changes, the malfunction rate slowly declined and new soldiers were generally unfamiliar with early problems. A rib was built into the side of the receiver on the XM16E1 to help prevent accidentally pressing the magazine release button while closing the ejection port cover. This rib was later extended on production M16A1s to help in preventing the magazine release from inadvertently being pressed. The hole in the bolt that accepts the cam pin was crimped inward on one side, in such a way that the cam pin may not be inserted with the bolt installed backwards, which would cause failures to eject until corrected. The M16A1 is no longer in service with the United States, but is still standard issue in many world armies.

M16A2

The development of the M16A2 rifle was originally requested by the United States Marine Corps as a result of the USMC's combat experience in Vietnam with the XM16E1 and M16A1. The Marines were the first branch of the U.S. Armed Forces to adopt the M16A2 in the early/mid-1980s, with the United States Army following suit in the late 1980s. Modifications to the M16A2 were extensive. In addition to the new rifling, the barrel was made with a greater thickness in front of the front sight post, to resist bending in the field and to allow a longer period of sustained fire without overheating. The rest of the barrel was maintained at the original thickness to enable the M203 grenade launcher to be attached. A new adjustable rear sight was added, allowing the rear sight to be dialed in for specific range settings between 300 and 800 meters to take full advantage of the ballistic characteristics of the new SS109 rounds and to allow windage adjustments without the need of a tool or cartridge.[99] The weapon's reliability allowed it to be widely used around the United States Marine Corps special operations divisions as well. The flash suppressor was again modified, this time to be closed on the bottom so it would not kick up dirt or snow when being fired from the prone position, and acting as a recoil compensator.[100] The front grip was modified from the original triangular shape to a round one, which better fit smaller hands and could be fitted to older models of the M16. The new handguards were also symmetrical so that armories need not separate left and right spares. The handguard retention ring was tapered to make it easier to install and uninstall the handguards. A notch for the middle finger was added to the pistol grip, as well as more texture to enhance the grip. The buttstock was lengthened by 5⁄8 in (15.9 mm).[99] The new buttstock became ten times stronger than the original due to advances in polymer technology since the early 1960s. Original M16 stocks were made from fiberglass-impregnated resin; the newer stocks were engineered from DuPont Zytel glass-filled thermoset polymers. The new stock included a fully textured polymer buttplate for better grip on the shoulder, and retained a panel for accessing a small compartment inside the stock, often used for storing a basic cleaning kit. The heavier bullet reduces muzzle velocity from 3,200 feet per second (980 m/s), to about 3,050 feet per second (930 m/s).[101] The A2 uses a faster twist rifling to allow the use of a trajectory-matched tracer round. It has a 1:7 twist rate. A spent case deflector was incorporated into the upper receiver immediately behind the ejection port to prevent cases from striking left-handed users.[99]

The action was also modified, replacing the fully automatic setting with a three-round burst setting.[99] When using a fully automatic weapon, inexperienced troops often hold down the trigger and "spray" when under fire. The U.S. Army concluded that three-shot groups provide an optimum combination of ammunition conservation, accuracy and firepower. Several Marine units utilize modified rifles that support fully automatic fire capabilities. The USMC has retired the M16A2 in favor of the newer M16A4. However, many M16A2s remain in U.S. Army, Air Force, Navy and Coast Guard service.[citation needed]

M16A3

The M16A3 is a select-fire variant of the M16A2 adopted in small numbers around the time of the introduction of the M16A2, primarily by the U.S. Navy for use by SEAL, Seabee, and Security units.[102] It features the M16A1 trigger group providing "safe", "semi-automatic", and "fully automatic" modes.

M16A4

The M16A4 is the fourth generation of the M16 series. It is equipped with a removable carrying handle and a full length quad Picatinny rail for mounting optics and other ancillary devices. The FN M16A4, using safe/semi/burst selective fire, is now the standard issue for all U.S. Marine Corps and is the current issue to Marine Corps' recruits in both MCRD San Diego and MCRD Parris Island.[102]

Military issue rifles are also equipped with a Knight's Armament Company M5 RAS hand guard, allowing vertical grips, lasers, tactical lights, and other accessories to be attached, coining the designation M16A4 MWS (or Modular Weapon System) in U.S. Army field manuals.[103]

Colt also produces M16A4 models for international purchases, with specifics selective fire:

- R0901 / NSN 1005-01-383-2872 (Safe/Semi/Auto)

- R0905 (Safe/Semi/Burst)

The Marine Corps is considering a Product Improvement Program (PIP) for their M16A4 MWS rifles. Potential features include a modular and adjustable stock, ambidextrous fire selector, heavier barrel, improved trigger, free-floating rail system, and an adjustable gas block and gas regulator to give all rifles a suppression capability.[104]

A study of significant changes to Marine M16A4 rifles released in February 2015 outlined several new features that could be added from inexpensive and available components. Those features include: a muzzle compensator in place of the flash suppressor to manage recoil and allow for faster follow-on shots, though at the cost of noise and flash signature and potential overpressure in close quarters; and heavier and/or free-floating barrel to increase accuracy from 4.5 MOA to potentially 2 MOA; changing the reticle on the Rifle Combat Optic from chevron-shaped to the semi-circle with a dot at the center used in the M27 IAR's Squad Day Optic so as not to obscure the target at long distance; using a trigger group with a more consistent pull force, even a reconsideration of the burst capability; and the addition of ambidextrous charging handles and bolt catch releases for easier use with left-handed shooters.[105]

Summary

| Colt model no. | Military designation | Barrel Length | Barrel | Handguard type | Buttstock type | Pistol grip type | Lower receiver type | Upper receiver type | Rear sight type | Front sight type | Muzzle device | Forward assist? | Case deflector? | Bayonet lug? | Trigger pack |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 601 | AR-15 | 20 in (508 mm) | A1 profile (1:14 twist) | Green or brown full-length triangular | Green or brown fixed A1 | A1 | A1 | A1 | A1 | A1 | Duckbill flash suppressor | No | No | Yes | Safe-Semi-Auto |

| 602 | AR-15 or XM16 | 20 in (508 mm) | A1 profile (1:12 twist) | Full-length triangular | Fixed A1 | A1 | A1 | A1 | A1 | A1 | Duckbill or three-prong flash suppressor | No | No | Yes | Safe-Semi-Auto |

| 603 | XM16E1 | 20 in (508 mm) | A1 profile (1:12 twist) | Full-length triangular | Fixed A1 | A1 | A1 | A1 | A1 | A1 | Three-prong or M16A1 birdcage flash suppressor | Yes | No | Yes | Safe-Semi-Auto |

| 603 | M16A1 | 20 in (508 mm) | A1 profile (1:12 twist) | Full-length triangular | Fixed A1 | A1 | A1 | A1 | A1 | A1 | Three-prong or birdcage flash suppressor | Yes | No | Yes | Safe-Semi-Auto |

| 604 | M16 | 20 in (508 mm) | A1 profile (1:12 twist) | Full-length triangular | Fixed A1 | A1 | A1 | A1 | A1 | A1 | Three-prong or M16A1-style birdcage flash suppressor | No | No | Yes | Safe-Semi-Auto |

| 645 | M16A1E1/PIP | 20 in (508 mm) | A2 profile (1:7 twist) | Full-length ribbed | Fixed A2 | A1 | A1 or A2 | A1 or A2 | A1 or A2 | A2 | M16A1 or M16A2-style birdcage flash suppressor | Yes | Yes or No | Yes | Safe-Semi-Auto or Safe-Semi-Burst |

| 645 | M16A2 | 20 in (508 mm) | A2 profile (1:7 twist) | Full-length ribbed | Fixed A2 | A2 | A2 | A2 | A2 | A2 | M16A2-style birdcage flash suppressor | Yes | Yes | Yes | Safe-Semi-Burst

or Safe-Semi-Burst-Auto |

| 645E | M16A2E1 | 20 in (508 mm) | A2 profile (1:7 twist) | Full-length ribbed | Fixed A2 | A2 | A2 | Flattop with Colt Rail | Flip-up | Folding | M16A2-style birdcage flash suppressor | Yes | Yes | Yes | Safe-Semi-Burst

or Safe-Semi-Burst-Auto |

| N/A | M16A2E2 | 20 in (508 mm) | A2 profile (1:7 twist) | Full-length semi-beavertail w/ HEL guide | Retractable ACR | ACR | A2 | Flattop with Colt rail | None | A2 | ACR muzzle brake | Yes | Yes | Yes | Safe-Semi-Burst

or Safe-Semi-Burst-Auto |

| 646 | M16A2E3/M16A3 | 20 in (508 mm) | A2 profile (1:7 twist) | Full-length ribbed | Fixed A2 | A2 | A2 | A2 | A2 | A2 | M16A2-style birdcage flash suppressor | Yes | Yes | Yes | Safe-Semi-Auto |

| 655 | M16A1 Special High Profile | 20 in (508 mm) | HBAR profile (1:12 twist) |

Full-length triangular | Fixed A1 | A1 | A1 | A1 | A1 | A1 | M16A1-style birdcage flash suppressor | Yes | No | Yes | Safe-Semi-Auto |

| 656 | M16A1 Special Low Profile | 20 in (508 mm) | HBAR profile (1:12 twist) |

Full-length triangular | Fixed A1 | A1 | A1 | A1 with modified Weaver base | Low Profile A1 | Hooded A1 | M16A1-style birdcage flash suppressor | Yes | No | Yes | Safe-Semi-Auto |

| 945 | M16A2E4/M16A4 | 20 in (508 mm) | A2 profile (1:7 twist) | Full-length ribbed or KAC M5 RAS | Fixed A2 | A2 | A2 | Flattop with MIL-STD-1913 rail | None | A4 | M16A2-style birdcage flash suppressor | Yes | Yes | Yes | Safe-Semi-Burst |

| Colt model no. | Military designation | Barrel Length | Barrel | Handguard type | Buttstock type | Pistol grip type | Lower receiver type | Upper receiver type | Rear sight type | Front sight type | Muzzle device | Forward assist? | Case deflector? | Bayonet lug? | Trigger pack |

Derivatives

Colt Model 655 and 656 "Sniper" variants

With the expanding Vietnam War, Colt developed two rifles of the M16 pattern for evaluation as possible light sniper or designated marksman rifles. The Colt Model 655 M16A1 Special High Profile was essentially a standard A1 rifle with a heavier barrel and a scope bracket that attached to the rifle's carry handle. The Colt Model 656 M16A1 Special Low Profile had a special upper receiver with no carrying handle. Instead, it had a low-profile iron sight adjustable for windage and a Weaver base for mounting a scope, a precursor to the Colt and Picatinny rails. It also had a hooded front iron sight in addition to the heavy barrel. Both rifles came standard with either a Leatherwood/Realist scope 3–9× Adjustable Ranging Telescope. Some of them were fitted with a Sionics noise and flash suppressor. Neither of these rifles were ever standardized.

These weapons can be seen in many ways to be predecessors of the U.S. Army's SDM-R and the USMC's SAM-R weapons.

XM177

In Vietnam, some soldiers were issued a carbine version of the M16 called the XM177. The XM177 had a shorter 10 in (254 mm) barrel and a telescoping stock, which made it substantially more compact. It also possessed a combination flash hider/sound moderator to reduce problems with muzzle flash and loud report. The Air Force's GAU-5/A (XM177) and the Army's XM177E1 variants differed over the latter’s inclusion of a forward assist, although some GAU-5s do have the forward assist. The final Air Force GAU-5/A and Army XM177E2 had an 11.5 in (292 mm) barrel with a longer flash/sound suppressor. The lengthening of the barrel was to support the attachment of Colt's own XM148 40 mm grenade launcher. These versions were also known as the Colt Commando model commonly referenced and marketed as the CAR-15. The variants were issued in limited numbers to special forces, helicopter crews, Air Force pilots, Air Force Security Police Military Working Dog (MWD) handlers, officers, radio operators, artillerymen, and troops other than front line riflemen. Some USAF GAU-5A/As were later equipped with even longer 14.5-inch (370 mm) 1/12 rifled barrels as the two shorter versions were worn out. The 14.5-inch (370 mm) barrel allowed the use of MILES gear and for bayonets to be used with the sub-machine guns (as the Air Force described them). By 1989, the Air Force started to replace the earlier barrels with 1/7 rifled models for use with the M855 round. The weapons were given the redesignation of GUU-5/P.

These were effectively used by the British Special Air Service during the Falklands War.[98]

Colt Model 733

Colt also returned to the original "Commando" idea, with its Model 733, essentially a modernized XM177E2 with many of the features introduced on the M16A2.

M231 Firing Port Weapon (FPW)

M231 Firing Port Weapon (FPW) is an adapted version of the M16 assault rifle for firing from ports on the M2 Bradley. The infantry's normal M16s are too long for use in a "buttoned up" fighting vehicle, so the FPW was developed to provide a suitable weapon for this role. Designed by the Rock Island Arsenal, the M231 FPW remains in service, although all but the rear two firing ports on the Bradley have been removed. The M231 FPW fires from the open bolt and is only configured for fully automatic fire. The open bolt configuration gives the M231 a much higher cyclic rate of fire than the closed bolt operation of the M16A1. Official doctrine discourages deploying M231 outside of the firing port role. The weapon jams easily and is known to break the bolt without warning.

Mk 4 Mod 0

The Mk 4 Mod 0 was a variant of the M16A1 produced for the U.S. Navy SEALs during the Vietnam War and adopted in April 1970. It differed from the basic M16A1 primarily in being optimized for maritime operations and coming equipped with a sound suppressor. Most of the operating parts of the rifle were coated in Kal-Guard, a hole of 0.25 inches (6.4 mm) was drilled through the stock and buffer tube for drainage, and an O-ring was added to the end of the buffer assembly. The weapon could reportedly be carried to the depth of 200 feet (60 m) in water without damage. The initial Mk 2 Mod 0 Blast Suppressor was based on the U.S. Army's Human Engineering Lab's (HEL) M4 noise suppressor. The HEL M4 vented gas directly from the action, requiring a modified bolt carrier. A gas deflector was added to the charging handle to prevent gas from contacting the user. Thus, the HEL M4 suppressor was permanently mounted though it allowed normal semi-automatic and automatic operation. If the HEL M4 suppressor were removed, the weapon would have to be manually loaded after each single shot. On the other hand, the Mk 2 Mod 0 blast suppressor was considered an integral part of the Mk 4 Mod 0 rifle, but it would function normally if the suppressor were removed. The Mk 2 Mod 0 blast suppressor also drained water much more quickly and did not require any modification to the bolt carrier or to the charging handle. In the late 1970s, the Mk 2 Mod 0 blast suppressor was replaced by the Mk 2 blast suppressor made by Knight's Armament Company (KAC). The KAC suppressor can be fully submerged and water will drain out in less than eight seconds. It will operate without degradation even if the rifle is fired at the maximum rate of fire. The U.S. Army replaced the HEL M4 with the much simpler Studies in Operational Negation of Insurgency and Counter-Subversion (SIONICS) MAW-A1 noise and flash suppressor.

Mark 12

Developed to increase the effective range of soldiers in the designated marksman role, the U.S. Navy developed the Mark 12 Special Purpose Rifle (SPR). Configurations in service vary, but the core of the Mark 12 SPR is an 18" heavy barrel with muzzle brake and free float tube. This tube relieves pressure on the barrel caused by standard handguards and greatly increases the potential accuracy of the system. Also common are higher magnification optics ranging from the 6× power Trijicon ACOG to the Leupold Mark 4 Tactical rifle scopes. Firing Mark 262 Mod 0 ammunition with a 77gr Open tip Match bullet, the system has an official effective range of 600+ meters. However published reports of confirmed kills beyond 800 m from Iraq and Afghanistan are not uncommon.[citation needed]

M4 carbine

The M4 carbine was developed from various outgrowths of these designs, including a number of 14.5-inch (368 mm)-barreled A1 style carbines. The XM4 (Colt Model 727) started its trials in the mid-1980s, with a barrel of 14.5 inches (370 mm). Officially adopted as a replacement for the M3 "Grease Gun" (and the Beretta M9 and M16A2 for select troops) in 1994, it was used with great success in the Balkans and in more recent conflicts, including the Afghanistan and Iraq theaters. The M4 carbine has a three-round burst firing mode, while the M4A1 carbine has a fully automatic firing mode. Both have a Picatinny rail on the upper receiver, allowing the carry handle/rear sight assembly to be replaced with other sighting devices.

International derivatives

C7 and C8

The Diemaco C7 and C8 are updated variants of the M16 developed and used by the Canadian Forces and are now manufactured by Colt Canada. The C7 is a further development of the experimental M16A1E1. Like earlier M16s, it can be fired in either single shot or automatic mode, instead of the burst function selected for the M16A2. The C7 also features the structural strengthening, improved handguards, and longer stock developed for the M16A2. Diemaco changed the trapdoor in the buttstock to make it easier to access and a spacer of 0.5 inches (13 mm) is available to adjust stock length to user preference. The most easily noticeable external difference between American M16A2s and Diemaco C7s is the retention of the A1 style rear sights. Not easily apparent is Diemaco's use of hammer-forged barrels. The Canadians originally desired to use a heavy barrel profile instead.

The C7 has been developed to the C7A1, with a Weaver rail on the upper receiver for a C79 optical sight, and to the C7A2, with different furniture and internal improvements. The Diemaco produced Weaver rail on the original C7A1 variants does not meet the M1913 'Picatinny' standard, leading to some problems with mounting commercial sights. This is easily remedied with minor modification to the upper receiver or the sight itself. Since Diemaco's acquisition by Colt to form Colt Canada, all Canadian produced flattop upper receivers are machined to the M1913 standard.

The C8 is the carbine version of the C7.[106] The C7 and C8 are also used by Hærens Jegerkommando, Marinejegerkommandoen and FSK (Norway), Military of Denmark (all branches), the Royal Netherlands Army and Netherlands Marine Corps as its main infantry weapon. Following trials, variants became the weapon of choice of the British SAS.

Others

- The Chinese Norinco CQ is an unlicensed derivative of the M16A1 made specifically for export, with the most obvious external differences being in its handguard and revolver-style pistol grip.

- The ARMADA rifle (a copy of the Norinco CQ) and TRAILBLAZER carbine (a copy of the Norinco CQ Type A) are manufactured by S.A.M. – Shooter's Arms Manufacturing, a.k.a. Shooter's Arms Guns & Ammo Corporation, headquartered in Metro Cebu, Republic of the Philippines.

- The S-5.56 rifle, a clone of the Type CQ, is manufactured by the Defense Industries Organization of Iran. The rifle itself is offered in two variants: the S-5.56 A1 with a 19.9-inch barrel and 1:12 pitch rifling (1 turn in 305mm), optimized for the use of the M193 Ball cartridge; and the S-5.56 A3 with a 20-inch barrel and a 1:7 pitch rifling (1 turn in 177, 8mm), optimized for the use of the SS109 cartridge.[107]

- The KH-2002 is an Iranian bullpup conversion of the locally produced S-5.56 rifle. Iran intends to replace the standard issue weapon of its armed forces with this rifle.

- The Terab rifle is a copy of the DIO S-5.56 manufactured by the MIC (Military Industry Corporation) of Sudan.

- The M16S1 is the M16A1 rifle made under license by ST Kinetics in Singapore. It was the standard issue weapon of the Singapore Armed Forces. It is being replaced by the newer SAR 21 in most branches. It is, in the meantime, the standard issue weapon in the reserve forces.

- The MSSR rifle developed as an effective, low cost sniper rifle by the Philippine Marine Corps Scout Snipers. The Special Operations Assault Rifle (SOAR) assault carbine was developed by Ferfrans based on the M16 rifle. It is used by the Special Action Force of the Philippine National Police .

- Taiwan uses piston-driven M16-based weapons as their standard rifle. These include the T65, T86 and T91 assault rifles.

Production and users

The M16 is the most commonly manufactured 5.56×45 mm rifle in the world. Currently, the M16 is in use by 15 NATO countries and more than 80 countries world wide. Together, numerous companies in the United States, Canada, and China have produced more than 8,000,000 rifles of all variants. Approximately 90% are still in operation.[5] The M16 replaced the M14 and M1 carbine as standard infantry rifles of the U.S. armed forces. The M14 continues to see limited service, mostly in sniper, designated marksman, and ceremonial roles.

Users

Afghanistan: Standard issue rifle of the Afghan National Army.[108] Colt Canada C7 variants also saw limited service.

Afghanistan: Standard issue rifle of the Afghan National Army.[108] Colt Canada C7 variants also saw limited service. Argentina: Special Forces used M16A1 in the Falklands (Malvinas) War and they currently use the M16A2.[109]

Argentina: Special Forces used M16A1 in the Falklands (Malvinas) War and they currently use the M16A2.[109] Australia[110] M16A1 introduced during the Vietnam War and replaced by the F88 Austeyr in 1989.

Australia[110] M16A1 introduced during the Vietnam War and replaced by the F88 Austeyr in 1989. Bahrain[111]: 77, 236, 262

Bahrain[111]: 77, 236, 262  Bosnia and Herzegovina[112]

Bosnia and Herzegovina[112] Bangladesh: Used by the military, special forces and counter terrorism units.[113]

Bangladesh: Used by the military, special forces and counter terrorism units.[113] Barbados[112]

Barbados[112] Belize[112]

Belize[112] Bolivia[112]

Bolivia[112] Brazil[112]

Brazil[112] Brunei[112]

Brunei[112] Cambodia[114][115] M16A1 is used.

Cambodia[114][115] M16A1 is used. Cameroon[112]

Cameroon[112] Canada: C7 and C8 variants made by Colt Canada is used by the Canadian Forces.[116]

Canada: C7 and C8 variants made by Colt Canada is used by the Canadian Forces.[116] Chile[112]

Chile[112] Costa Rica[117]

Costa Rica[117] Democratic Republic of the Congo[114]

Democratic Republic of the Congo[114] Denmark:[112] C7 and C8 variants made by Colt Canada are used by all branches of the Danish Defence.

Denmark:[112] C7 and C8 variants made by Colt Canada are used by all branches of the Danish Defence. Dominican Republic[112]

Dominican Republic[112] East Timor[118]

East Timor[118] Ecuador[112]

Ecuador[112] El Salvador[112] M16A1/A2/A3/A4 is used.

El Salvador[112] M16A1/A2/A3/A4 is used. Estonia[119] Ex-U.S. M16A1s in use.

Estonia[119] Ex-U.S. M16A1s in use. Fiji[112]

Fiji[112] France[112]

France[112] Gabon[112]

Gabon[112] Ghana[112]

Ghana[112] Greece[112] M16A2/M4 is used by the Special forces of the Hellenic Army ISAF Forces in Afghanistan and Hellenic Navy

Greece[112] M16A2/M4 is used by the Special forces of the Hellenic Army ISAF Forces in Afghanistan and Hellenic Navy Grenada[112]

Grenada[112] Guatemala[114] M16A1/M16A2 is used.

Guatemala[114] M16A1/M16A2 is used. Haiti[114]

Haiti[114] Honduras[120]

Honduras[120] India[112]

India[112] Indonesia[112]

Indonesia[112] Iraq: Used by Iraqi Army.[121]

Iraq: Used by Iraqi Army.[121] Israel[122] Being replaced by IMI Tavor.[123]

Israel[122] Being replaced by IMI Tavor.[123] Jamaica[112]

Jamaica[112] Jordan[112]

Jordan[112] South Korea: During the Vietnam War, the United States provided 27,000 M16 rifles to the Republic of Korea Armed Forces in Vietnam. Also, 600,000 M16A1s (Colt Model 603K) were manufactured under license by Daewoo Precision Industries. The delivery started in 1974 and ended in 1985.[112] Still KATUSA (Korean Augmentation to the United States Army) soldiers who serve their military service in the United States Army uses M16A2 with the United States Army.