Speed of light

| |

| Exact values | |

|---|---|

| metres per second | 299792458 |

| Approximate values (to three significant digits) | |

| kilometres per hour | 1080000000 |

| miles per second | 186000 |

| miles per hour[1] | 671000000 |

| astronomical units per day | 173[Note 1] |

| parsecs per year | 0.307[Note 2] |

| Approximate light signal travel times | |

| Distance | Time |

| one foot | 1.0 ns |

| one metre | 3.3 ns |

| from geostationary orbit to Earth | 119 ms |

| the length of Earth's equator | 134 ms |

| from Moon to Earth | 1.3 s |

| from Sun to Earth (1 AU) | 8.3 min |

| one light-year | 1.0 year |

| one parsec | 3.26 years |

| from the nearest star to Sun (1.3 pc) | 4.2 years |

| from the nearest galaxy to Earth | 25000 years |

| across the Milky Way | 100000 years |

| from the Andromeda Galaxy to Earth | 2.5 million years |

| Special relativity |

|---|

|

The speed of light in vacuum, commonly denoted c, is a universal physical constant that is important in many areas of physics. Its exact value is defined as 299792458 metres per second (approximately 300000 km/s or 186000 mi/s).[Note 3] According to the special theory of relativity, c is the upper limit for the speed at which conventional matter, energy or any signal carrying information can travel through space.

All forms of electromagnetic radiation — not just visible light — travel at the speed of light. For many practical purposes, light and other electromagnetic waves will appear to propagate instantaneously, but for long distances and very sensitive measurements, their finite speed has noticeable effects. In communicating with distant space probes, it can take minutes to hours for a message to get from Earth to the spacecraft, or vice versa. The light seen from stars left them many years ago, allowing the study of the history of the universe by looking at distant objects. The finite speed of light also ultimately limits the data transfer between the CPU and memory chips in computers. The speed of light can be used with time of flight measurements to measure large distances to high precision.

Ole Rømer first demonstrated in 1676 that light travels at a finite speed (non-instantaneously) by studying the apparent motion of Jupiter's moon Io. Progressively more accurate measurements of its speed came over the following centuries. In 1865, James Clerk Maxwell proposed that light was an electromagnetic wave, and therefore travelled at the speed c appearing in his theory of electromagnetism.[4] In 1905, Albert Einstein postulated that the speed of light c with respect to any inertial frame is a constant and is independent of the motion of the light source.[5] He explored the consequences of that postulate by deriving the theory of relativity and in doing so showed that the parameter c had relevance outside of the context of light and electromagnetism.

Massless particles and field perturbations such as gravitational waves also travel at the speed c in vacuum. Such particles and waves travel at c regardless of the motion of the source or the inertial reference frame of the observer. Particles with nonzero rest mass can approach c, but can never actually reach it, regardless of the frame of reference in which their speed is measured. In the special and general theories of relativity, c interrelates space and time, and also appears in the famous equation of mass–energy equivalence, E = mc2.[6] In some cases objects or waves may appear to travel faster than light (e.g. phase velocities of waves, the appearance of certain high-speed astronomical objects, and particular quantum effects). The expansion of the universe is understood to exceed the speed of light beyond a certain boundary.

The speed at which light propagates through transparent materials, such as glass or air, is less than c; similarly, the speed of electromagnetic waves in wire cables is slower than c. The ratio between c and the speed v at which light travels in a material is called the refractive index n of the material (n = c / v). For example, for visible light, the refractive index of glass is typically around 1.5, meaning that light in glass travels at c / 1.5 ≈ 200000 km/s (124000 mi/s); the refractive index of air for visible light is about 1.0003, so the speed of light in air is about 90 km/s (56 mi/s) slower than c.

Numerical value, notation, and units

The speed of light in vacuum is usually denoted by a lowercase c, for "constant" or the Latin celeritas (meaning 'swiftness, celerity'). In 1856, Wilhelm Eduard Weber and Rudolf Kohlrausch had used c for a different constant that was later shown to equal √2 times the speed of light in vacuum. Historically, the symbol V was used as an alternative symbol for the speed of light, introduced by James Clerk Maxwell in 1865. In 1894, Paul Drude redefined c with its modern meaning. Einstein used V in his original German-language papers on special relativity in 1905, but in 1907 he switched to c, which by then had become the standard symbol for the speed of light.[7][8]

Sometimes c is used for the speed of waves in any material medium, and c0 for the speed of light in vacuum.[9] This subscripted notation, which is endorsed in official SI literature,[10] has the same form as other related constants: namely, μ0 for the vacuum permeability or magnetic constant, ε0 for the vacuum permittivity or electric constant, and Z0 for the impedance of free space. This article uses c exclusively for the speed of light in vacuum.

Since 1983, the metre has been defined in the International System of Units (SI) as the distance light travels in vacuum in 1⁄299792458 of a second. This definition fixes the speed of light in vacuum at exactly 299792458 m/s.[11] As a dimensional physical constant, the numerical value of c is different for different unit systems. For example, in imperial units, the speed of light is approximately 186282 miles per second,[Note 4] or roughly 1 foot per nanosecond.[12][13] In branches of physics in which c appears often, such as in relativity, it is common to use systems of natural units of measurement or the geometrized unit system where c = 1.[14][15] Using these units, c does not appear explicitly because multiplication or division by 1 does not affect the result. Its unit of lightsecond/second is still relevant, even if omitted.

Fundamental role in physics

The speed at which light waves propagate in vacuum is independent both of the motion of the wave source and of the inertial frame of reference of the observer.[Note 5] This invariance of the speed of light was postulated by Einstein in 1905,[5] after being motivated by Maxwell's theory of electromagnetism and the lack of evidence for the luminiferous aether;[16] it has since been consistently confirmed by many experiments.[Note 6] It is only possible to verify experimentally that the two-way speed of light (for example, from a source to a mirror and back again) is frame-independent, because it is impossible to measure the one-way speed of light (for example, from a source to a distant detector) without some convention as to how clocks at the source and at the detector should be synchronized. However, by adopting Einstein synchronization for the clocks, the one-way speed of light becomes equal to the two-way speed of light by definition.[17][18] The special theory of relativity explores the consequences of this invariance of c with the assumption that the laws of physics are the same in all inertial frames of reference.[19][20] One consequence is that c is the speed at which all massless particles and waves, including light, must travel in vacuum.[21][Note 7]

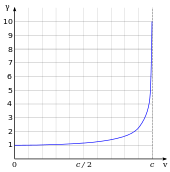

Special relativity has many counterintuitive and experimentally verified implications.[23] These include the equivalence of mass and energy (E = mc2), length contraction (moving objects shorten),[Note 8] and time dilation (moving clocks run more slowly). The factor γ by which lengths contract and times dilate is known as the Lorentz factor and is given by γ = (1 − v2/c2)−1/2, where v is the speed of the object. The difference of γ from 1 is negligible for speeds much slower than c, such as most everyday speeds—in which case special relativity is closely approximated by Galilean relativity—but it increases at relativistic speeds and diverges to infinity as v approaches c. For example, a time dilation factor of γ = 2 occurs at a relative velocity of 86.6% of the speed of light (v = 0.866 c). Similarly, a time dilation factor of γ = 10 occurs at v = 99.5% c.

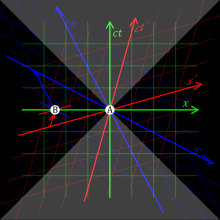

The results of special relativity can be summarized by treating space and time as a unified structure known as spacetime (with c relating the units of space and time), and requiring that physical theories satisfy a special symmetry called Lorentz invariance, whose mathematical formulation contains the parameter c.[26] Lorentz invariance is an almost universal assumption for modern physical theories, such as quantum electrodynamics, quantum chromodynamics, the Standard Model of particle physics, and general relativity. As such, the parameter c is ubiquitous in modern physics, appearing in many contexts that are unrelated to light. For example, general relativity predicts that c is also the speed of gravity and of gravitational waves,[27] and observations of gravitational waves have been consistent with this prediction.[28] In non-inertial frames of reference (gravitationally curved spacetime or accelerated reference frames), the local speed of light is constant and equal to c, but the speed of light along a trajectory of finite length can differ from c, depending on how distances and times are defined.[29]

It is generally assumed that fundamental constants such as c have the same value throughout spacetime, meaning that they do not depend on location and do not vary with time. However, it has been suggested in various theories that the speed of light may have changed over time.[30][31] No conclusive evidence for such changes has been found, but they remain the subject of ongoing research.[32][33]

It also is generally assumed that the speed of light is isotropic, meaning that it has the same value regardless of the direction in which it is measured. Observations of the emissions from nuclear energy levels as a function of the orientation of the emitting nuclei in a magnetic field (see Hughes–Drever experiment), and of rotating optical resonators (see Resonator experiments) have put stringent limits on the possible two-way anisotropy.[34][35]

Upper limit on speeds

According to special relativity, the energy of an object with rest mass m and speed v is given by γmc2, where γ is the Lorentz factor defined above. When v is zero, γ is equal to one, giving rise to the famous E = mc2 formula for mass–energy equivalence. The γ factor approaches infinity as v approaches c, and it would take an infinite amount of energy to accelerate an object with mass to the speed of light. The speed of light is the upper limit for the speeds of objects with positive rest mass, and individual photons cannot travel faster than the speed of light.[36] This is experimentally established in many tests of relativistic energy and momentum.[37]

More generally, it is impossible for signals or energy to travel faster than c. One argument for this follows from the counter-intuitive implication of special relativity known as the relativity of simultaneity. If the spatial distance between two events A and B is greater than the time interval between them multiplied by c then there are frames of reference in which A precedes B, others in which B precedes A, and others in which they are simultaneous. As a result, if something were travelling faster than c relative to an inertial frame of reference, it would be travelling backwards in time relative to another frame, and causality would be violated.[Note 9][40] In such a frame of reference, an "effect" could be observed before its "cause". Such a violation of causality has never been recorded,[18] and would lead to paradoxes such as the tachyonic antitelephone.[41]

Faster-than-light observations and experiments

There are situations in which it may seem that matter, energy, or information-carrying signal travels at speeds greater than c, but they do not. For example, as is discussed in the propagation of light in a medium section below, many wave velocities can exceed c. The phase velocity of X-rays through most glasses can routinely exceed c,[42] but phase velocity does not determine the velocity at which waves convey information.[43]

If a laser beam is swept quickly across a distant object, the spot of light can move faster than c, although the initial movement of the spot is delayed because of the time it takes light to get to the distant object at the speed c. However, the only physical entities that are moving are the laser and its emitted light, which travels at the speed c from the laser to the various positions of the spot. Similarly, a shadow projected onto a distant object can be made to move faster than c, after a delay in time.[44] In neither case does any matter, energy, or information travel faster than light.[45]

The rate of change in the distance between two objects in a frame of reference with respect to which both are moving (their closing speed) may have a value in excess of c. However, this does not represent the speed of any single object as measured in a single inertial frame.[45]

Certain quantum effects appear to be transmitted instantaneously and therefore faster than c, as in the EPR paradox. An example involves the quantum states of two particles that can be entangled. Until either of the particles is observed, they exist in a superposition of two quantum states. If the particles are separated and one particle's quantum state is observed, the other particle's quantum state is determined instantaneously. However, it is impossible to control which quantum state the first particle will take on when it is observed, so information cannot be transmitted in this manner.[45][46]

Another quantum effect that predicts the occurrence of faster-than-light speeds is called the Hartman effect: under certain conditions the time needed for a virtual particle to tunnel through a barrier is constant, regardless of the thickness of the barrier.[47][48] This could result in a virtual particle crossing a large gap faster-than-light. However, no information can be sent using this effect.[49]

So-called superluminal motion is seen in certain astronomical objects,[50] such as the relativistic jets of radio galaxies and quasars. However, these jets are not moving at speeds in excess of the speed of light: the apparent superluminal motion is a projection effect caused by objects moving near the speed of light and approaching Earth at a small angle to the line of sight: since the light which was emitted when the jet was farther away took longer to reach the Earth, the time between two successive observations corresponds to a longer time between the instants at which the light rays were emitted.[51]

A 2011 report of neutrinos appearing to travel faster than light turned out to be due to experimental error.[52][53]

In models of the expanding universe, the farther galaxies are from each other, the faster they drift apart. This receding is not due to motion through space, but rather to the expansion of space itself.[45] For example, galaxies far away from Earth appear to be moving away from the Earth with a speed proportional to their distances. Beyond a boundary called the Hubble sphere, the rate at which their distance from Earth increases becomes greater than the speed of light.[54]

Propagation of light

In classical physics, light is described as a type of electromagnetic wave. The classical behaviour of the electromagnetic field is described by Maxwell's equations, which predict that the speed c with which electromagnetic waves (such as light) propagate in vacuum is related to the distributed capacitance and inductance of vacuum, otherwise respectively known as the electric constant ε0 and the magnetic constant μ0, by the equation[55]

In modern quantum physics, the electromagnetic field is described by the theory of quantum electrodynamics (QED). In this theory, light is described by the fundamental excitations (or quanta) of the electromagnetic field, called photons. In QED, photons are massless particles and thus, according to special relativity, they travel at the speed of light in vacuum.[21]

Extensions of QED in which the photon has a mass have been considered. In such a theory, its speed would depend on its frequency, and the invariant speed c of special relativity would then be the upper limit of the speed of light in vacuum.[29] No variation of the speed of light with frequency has been observed in rigorous testing, putting stringent limits on the mass of the photon.[56] The limit obtained depends on the model used: if the massive photon is described by Proca theory,[57] the experimental upper bound for its mass is about 10−57 grams;[58] if photon mass is generated by a Higgs mechanism, the experimental upper limit is less sharp, m ≤ 10−14 eV/c2 (roughly 2 × 10−47 g).[57]

Another reason for the speed of light to vary with its frequency would be the failure of special relativity to apply to arbitrarily small scales, as predicted by some proposed theories of quantum gravity. In 2009, the observation of gamma-ray burst GRB 090510 found no evidence for a dependence of photon speed on energy, supporting tight constraints in specific models of spacetime quantization on how this speed is affected by photon energy for energies approaching the Planck scale.[59]

In a medium

In a medium, light usually does not propagate at a speed equal to c; further, different types of light wave will travel at different speeds. The speed at which the individual crests and troughs of a plane wave (a wave filling the whole space, with only one frequency) propagate is called the phase velocity vp. A physical signal with a finite extent (a pulse of light) travels at a different speed. The overall envelope of the pulse travels at the group velocity vg, and its earliest part travels at the front velocity vf.[60]

The phase velocity is important in determining how a light wave travels through a material or from one material to another. It is often represented in terms of a refractive index. The refractive index of a material is defined as the ratio of c to the phase velocity vp in the material: larger indices of refraction indicate lower speeds. The refractive index of a material may depend on the light's frequency, intensity, polarization, or direction of propagation; in many cases, though, it can be treated as a material-dependent constant. The refractive index of air is approximately 1.0003.[61] Denser media, such as water,[62] glass,[63] and diamond,[64] have refractive indexes of around 1.3, 1.5 and 2.4, respectively, for visible light. In exotic materials like Bose–Einstein condensates near absolute zero, the effective speed of light may be only a few metres per second. However, this represents absorption and re-radiation delay between atoms, as do all slower-than-c speeds in material substances. As an extreme example of light "slowing" in matter, two independent teams of physicists claimed to bring light to a "complete standstill" by passing it through a Bose–Einstein condensate of the element rubidium. However, the popular description of light being "stopped" in these experiments refers only to light being stored in the excited states of atoms, then re-emitted at an arbitrarily later time, as stimulated by a second laser pulse. During the time it had "stopped", it had ceased to be light. This type of behaviour is generally microscopically true of all transparent media which "slow" the speed of light.[65]

In transparent materials, the refractive index generally is greater than 1, meaning that the phase velocity is less than c. In other materials, it is possible for the refractive index to become smaller than 1 for some frequencies; in some exotic materials it is even possible for the index of refraction to become negative.[66] The requirement that causality is not violated implies that the real and imaginary parts of the dielectric constant of any material, corresponding respectively to the index of refraction and to the attenuation coefficient, are linked by the Kramers–Kronig relations.[67][68] In practical terms, this means that in a material with refractive index less than 1, the wave will be absorbed quickly.[69]

A pulse with different group and phase velocities (which occurs if the phase velocity is not the same for all the frequencies of the pulse) smears out over time, a process known as dispersion. Certain materials have an exceptionally low (or even zero) group velocity for light waves, a phenomenon called slow light.[70] The opposite, group velocities exceeding c, was proposed theoretically in 1993 and achieved experimentally in 2000.[71] It should even be possible for the group velocity to become infinite or negative, with pulses travelling instantaneously or backwards in time.[60]

None of these options, however, allow information to be transmitted faster than c. It is impossible to transmit information with a light pulse any faster than the speed of the earliest part of the pulse (the front velocity). It can be shown that this is (under certain assumptions) always equal to c.[60]

It is possible for a particle to travel through a medium faster than the phase velocity of light in that medium (but still slower than c). When a charged particle does that in a dielectric material, the electromagnetic equivalent of a shock wave, known as Cherenkov radiation, is emitted.[72]

Practical effects of finiteness

The speed of light is of relevance to communications: the one-way and round-trip delay time are greater than zero. This applies from small to astronomical scales. On the other hand, some techniques depend on the finite speed of light, for example in distance measurements.

Small scales

In supercomputers, the speed of light imposes a limit on how quickly data can be sent between processors. If a processor operates at 1 gigahertz, a signal can travel only a maximum of about 30 centimetres (1 ft) in a single cycle. Processors must therefore be placed close to each other to minimize communication latencies; this can cause difficulty with cooling. If clock frequencies continue to increase, the speed of light will eventually become a limiting factor for the internal design of single chips.[73][74]

Large distances on Earth

Given that the equatorial circumference of the Earth is about 40075 km and that c is about 300000 km/s, the theoretical shortest time for a piece of information to travel half the globe along the surface is about 67 milliseconds. When light is travelling around the globe in an optical fibre, the actual transit time is longer, in part because the speed of light is slower by about 35% in an optical fibre, depending on its refractive index n.[Note 10] Furthermore, straight lines rarely occur in global communications situations, and delays are created when the signal passes through an electronic switch or signal regenerator.[76]

Spaceflights and astronomy

Similarly, communications between the Earth and spacecraft are not instantaneous. There is a brief delay from the source to the receiver, which becomes more noticeable as distances increase. This delay was significant for communications between ground control and Apollo 8 when it became the first crewed spacecraft to orbit the Moon: for every question, the ground control station had to wait at least three seconds for the answer to arrive.[77] The communications delay between Earth and Mars can vary between five and twenty minutes depending upon the relative positions of the two planets. As a consequence of this, if a robot on the surface of Mars were to encounter a problem, its human controllers would not be aware of it until at least five minutes later, and possibly up to twenty minutes later; it would then take a further five to twenty minutes for instructions to travel from Earth to Mars.[78]

Receiving light and other signals from distant astronomical sources can even take much longer. For example, it has taken 13 billion (13×109) years for light to travel to Earth from the faraway galaxies viewed in the Hubble Ultra Deep Field images.[79][80] Those photographs, taken today, capture images of the galaxies as they appeared 13 billion years ago, when the universe was less than a billion years old.[79] The fact that more distant objects appear to be younger, due to the finite speed of light, allows astronomers to infer the evolution of stars, of galaxies, and of the universe itself.[81]

Astronomical distances are sometimes expressed in light-years, especially in popular science publications and media.[82] A light-year is the distance light travels in one Julian year, around 9461 billion kilometres, 5879 billion miles, or 0.3066 parsecs. In round figures, a light year is nearly 10 trillion kilometres or nearly 6 trillion miles. Proxima Centauri, the closest star to Earth after the Sun, is around 4.2 light-years away.[83]

Distance measurement

Radar systems measure the distance to a target by the time it takes a radio-wave pulse to return to the radar antenna after being reflected by the target: the distance to the target is half the round-trip transit time multiplied by the speed of light. A Global Positioning System (GPS) receiver measures its distance to GPS satellites based on how long it takes for a radio signal to arrive from each satellite, and from these distances calculates the receiver's position. Because light travels about 300000 kilometres (186000 miles) in one second, these measurements of small fractions of a second must be very precise. The Lunar Laser Ranging Experiment, radar astronomy and the Deep Space Network determine distances to the Moon,[84] planets[85] and spacecraft,[86] respectively, by measuring round-trip transit times.

High-frequency trading

The speed of light has become important in high-frequency trading, where traders seek to gain minute advantages by delivering their trades to exchanges fractions of a second ahead of other traders. For example, traders have been switching to microwave communications between trading hubs, because of the advantage which microwaves travelling at near to the speed of light in air have over fibre optic signals, which travel 30–40% slower.[87][88]

Measurement

There are different ways to determine the value of c. One way is to measure the actual speed at which light waves propagate, which can be done in various astronomical and Earth-based setups. However, it is also possible to determine c from other physical laws where it appears, for example, by determining the values of the electromagnetic constants ε0 and μ0 and using their relation to c. Historically, the most accurate results have been obtained by separately determining the frequency and wavelength of a light beam, with their product equalling c. This is described in more detail in the "Interferometry" section below.

In 1983 the metre was defined as "the length of the path travelled by light in vacuum during a time interval of 1⁄299792458 of a second",[89] fixing the value of the speed of light at 299792458 m/s by definition, as described below. Consequently, accurate measurements of the speed of light yield an accurate realization of the metre rather than an accurate value of c.

Astronomical measurements

Outer space is a convenient setting for measuring the speed of light because of its large scale and nearly perfect vacuum. Typically, one measures the time needed for light to traverse some reference distance in the Solar System, such as the radius of the Earth's orbit. Historically, such measurements could be made fairly accurately, compared to how accurately the length of the reference distance is known in Earth-based units.

Ole Christensen Rømer used an astronomical measurement to make the first quantitative estimate of the speed of light in the year 1676.[90][91] When measured from Earth, the periods of moons orbiting a distant planet are shorter when the Earth is approaching the planet than when the Earth is receding from it. The distance travelled by light from the planet (or its moon) to Earth is shorter when the Earth is at the point in its orbit that is closest to its planet than when the Earth is at the farthest point in its orbit, the difference in distance being the diameter of the Earth's orbit around the Sun. The observed change in the moon's orbital period is caused by the difference in the time it takes light to traverse the shorter or longer distance. Rømer observed this effect for Jupiter's innermost moon Io and deduced that light takes 22 minutes to cross the diameter of the Earth's orbit.[90]

Another method is to use the aberration of light, discovered and explained by James Bradley in the 18th century.[92] This effect results from the vector addition of the velocity of light arriving from a distant source (such as a star) and the velocity of its observer (see diagram on the right). A moving observer thus sees the light coming from a slightly different direction and consequently sees the source at a position shifted from its original position. Since the direction of the Earth's velocity changes continuously as the Earth orbits the Sun, this effect causes the apparent position of stars to move around. From the angular difference in the position of stars (maximally 20.5 arcseconds)[93] it is possible to express the speed of light in terms of the Earth's velocity around the Sun, which with the known length of a year can be converted to the time needed to travel from the Sun to the Earth. In 1729, Bradley used this method to derive that light travelled 10210 times faster than the Earth in its orbit (the modern figure is 10066 times faster) or, equivalently, that it would take light 8 minutes 12 seconds to travel from the Sun to the Earth.[92]

Astronomical unit

An astronomical unit (AU) is approximately the average distance between the Earth and Sun. It was redefined in 2012 as exactly 149597870700 m.[94][95] Previously the AU was not based on the International System of Units but in terms of the gravitational force exerted by the Sun in the framework of classical mechanics.[Note 11] The current definition uses the recommended value in metres for the previous definition of the astronomical unit, which was determined by measurement.[94] This redefinition is analogous to that of the metre and likewise has the effect of fixing the speed of light to an exact value in astronomical units per second (via the exact speed of light in metres per second).[97]

Previously, the inverse of c expressed in seconds per astronomical unit was measured by comparing the time for radio signals to reach different spacecraft in the Solar System, with their position calculated from the gravitational effects of the Sun and various planets. By combining many such measurements, a best fit value for the light time per unit distance could be obtained. For example, in 2009, the best estimate, as approved by the International Astronomical Union (IAU), was:[98][99]

- light time for unit distance: tau = 499.004783836(10) s

- c = 0.00200398880410(4) AU/s = 173.144632674(3) AU/day.

The relative uncertainty in these measurements is 0.02 parts per billion (2×10−11), equivalent to the uncertainty in Earth-based measurements of length by interferometry.[100] Since the metre is defined to be the length travelled by light in a certain time interval, the measurement of the light time in terms of the previous definition of the astronomical unit can also be interpreted as measuring the length of an AU (old definition) in metres.[Note 12]

Time of flight techniques

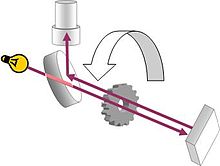

A method of measuring the speed of light is to measure the time needed for light to travel to a mirror at a known distance and back. This is the working principle behind the Fizeau–Foucault apparatus developed by Hippolyte Fizeau and Léon Foucault, based on a suggestion by François Arago.[101]

The setup as used by Fizeau consists of a beam of light directed at a mirror 8 kilometres (5 mi) away. On the way from the source to the mirror, the beam passes through a rotating cogwheel. At a certain rate of rotation, the beam passes through one gap on the way out and another on the way back, but at slightly higher or lower rates, the beam strikes a tooth and does not pass through the wheel. Knowing the distance between the wheel and the mirror, the number of teeth on the wheel, and the rate of rotation, the speed of light can be calculated.[102]

The method of Foucault replaces the cogwheel with a rotating mirror. Because the mirror keeps rotating while the light travels to the distant mirror and back, the light is reflected from the rotating mirror at a different angle on its way out than it is on its way back. From this difference in angle, the known speed of rotation and the distance to the distant mirror the speed of light may be calculated.[103]

Nowadays, using oscilloscopes with time resolutions of less than one nanosecond, the speed of light can be directly measured by timing the delay of a light pulse from a laser or an LED reflected from a mirror. This method is less precise (with errors of the order of 1%) than other modern techniques, but it is sometimes used as a laboratory experiment in college physics classes.[104]

Electromagnetic constants

An option for deriving c that does not directly depend on a measurement of the propagation of electromagnetic waves is to use the relation between c and the vacuum permittivity ε0 and vacuum permeability μ0 established by Maxwell's theory: c2 = 1/(ε0μ0). The vacuum permittivity may be determined by measuring the capacitance and dimensions of a capacitor, whereas the value of the vacuum permeability is fixed at exactly 4π×10−7 H⋅m−1 through the definition of the ampere. Rosa and Dorsey used this method in 1907 to find a value of 299710±22 km/s.[105][106]

Cavity resonance

Another way to measure the speed of light is to independently measure the frequency f and wavelength λ of an electromagnetic wave in vacuum. The value of c can then be found by using the relation c = fλ. One option is to measure the resonance frequency of a cavity resonator. If the dimensions of the resonance cavity are also known, these can be used to determine the wavelength of the wave. In 1946, Louis Essen and A.C. Gordon-Smith established the frequency for a variety of normal modes of microwaves of a microwave cavity of precisely known dimensions. The dimensions were established to an accuracy of about ±0.8 μm using gauges calibrated by interferometry.[105] As the wavelength of the modes was known from the geometry of the cavity and from electromagnetic theory, knowledge of the associated frequencies enabled a calculation of the speed of light.[105][107]

The Essen–Gordon-Smith result, 299792±9 km/s, was substantially more precise than those found by optical techniques.[105] By 1950, repeated measurements by Essen established a result of 299792.5±3.0 km/s.[108]

A household demonstration of this technique is possible, using a microwave oven and food such as marshmallows or margarine: if the turntable is removed so that the food does not move, it will cook the fastest at the antinodes (the points at which the wave amplitude is the greatest), where it will begin to melt. The distance between two such spots is half the wavelength of the microwaves; by measuring this distance and multiplying the wavelength by the microwave frequency (usually displayed on the back of the oven, typically 2450 MHz), the value of c can be calculated, "often with less than 5% error".[109][110]

Interferometry

Interferometry is another method to find the wavelength of electromagnetic radiation for determining the speed of light.[Note 13] A coherent beam of light (e.g. from a laser), with a known frequency (f), is split to follow two paths and then recombined. By adjusting the path length while observing the interference pattern and carefully measuring the change in path length, the wavelength of the light (λ) can be determined. The speed of light is then calculated using the equation c = λf.

Before the advent of laser technology, coherent radio sources were used for interferometry measurements of the speed of light.[112] However interferometric determination of wavelength becomes less precise with wavelength and the experiments were thus limited in precision by the long wavelength (~4 mm (0.16 in)) of the radiowaves. The precision can be improved by using light with a shorter wavelength, but then it becomes difficult to directly measure the frequency of the light. One way around this problem is to start with a low frequency signal of which the frequency can be precisely measured, and from this signal progressively synthesize higher frequency signals whose frequency can then be linked to the original signal. A laser can then be locked to the frequency, and its wavelength can be determined using interferometry.[113] This technique was due to a group at the National Bureau of Standards (which later became the National Institute of Standards and Technology). They used it in 1972 to measure the speed of light in vacuum with a fractional uncertainty of 3.5×10−9.[113][114]

History

| <1638 | Galileo, covered lanterns | inconclusive[115][116][117]: 1252 [Note 14] | |

| <1667 | Accademia del Cimento, covered lanterns | inconclusive[117]: 1253 [118] | |

| 1675 | Rømer and Huygens, moons of Jupiter | 220000[91][119] | ‒27% error |

| 1729 | James Bradley, aberration of light | 301000[102] | +0.40% error |

| 1849 | Hippolyte Fizeau, toothed wheel | 315000[102] | +5.1% error |

| 1862 | Léon Foucault, rotating mirror | 298000±500[102] | ‒0.60% error |

| 1907 | Rosa and Dorsey, EM constants | 299710±30[105][106] | ‒280 ppm error |

| 1926 | Albert A. Michelson, rotating mirror | 299796±4[120] | +12 ppm error |

| 1950 | Essen and Gordon-Smith, cavity resonator | 299792.5±3.0[108] | +0.14 ppm error |

| 1958 | K.D. Froome, radio interferometry | 299792.50±0.10[112] | +0.14 ppm error |

| 1972 | Evenson et al., laser interferometry | 299792.4562±0.0011[114] | ‒0.006 ppm error |

| 1983 | 17th CGPM, definition of the metre | 299792.458 (exact)[89] | exact, as defined |

Until the early modern period, it was not known whether light travelled instantaneously or at a very fast finite speed. The first extant recorded examination of this subject was in ancient Greece. The ancient Greeks, Muslim scholars, and classical European scientists long debated this until Rømer provided the first calculation of the speed of light. Einstein's Theory of Special Relativity concluded that the speed of light is constant regardless of one's frame of reference. Since then, scientists have provided increasingly accurate measurements.

Early history

Empedocles (c. 490–430 BC) was the first to propose a theory of light[121] and claimed that light has a finite speed.[122] He maintained that light was something in motion, and therefore must take some time to travel. Aristotle argued, to the contrary, that "light is due to the presence of something, but it is not a movement".[123] Euclid and Ptolemy advanced Empedocles' emission theory of vision, where light is emitted from the eye, thus enabling sight. Based on that theory, Heron of Alexandria argued that the speed of light must be infinite because distant objects such as stars appear immediately upon opening the eyes.[124] Early Islamic philosophers initially agreed with the Aristotelian view that light had no speed of travel. In 1021, Alhazen (Ibn al-Haytham) published the Book of Optics, in which he presented a series of arguments dismissing the emission theory of vision in favour of the now accepted intromission theory, in which light moves from an object into the eye.[125] This led Alhazen to propose that light must have a finite speed,[123][126][127] and that the speed of light is variable, decreasing in denser bodies.[127][128] He argued that light is substantial matter, the propagation of which requires time, even if this is hidden from our senses.[129] Also in the 11th century, Abū Rayhān al-Bīrūnī agreed that light has a finite speed, and observed that the speed of light is much faster than the speed of sound.[130]

In the 13th century, Roger Bacon argued that the speed of light in air was not infinite, using philosophical arguments backed by the writing of Alhazen and Aristotle.[131][132] In the 1270s, Witelo considered the possibility of light travelling at infinite speed in vacuum, but slowing down in denser bodies.[133]

In the early 17th century, Johannes Kepler believed that the speed of light was infinite since empty space presents no obstacle to it. René Descartes argued that if the speed of light were to be finite, the Sun, Earth, and Moon would be noticeably out of alignment during a lunar eclipse. Since such misalignment had not been observed, Descartes concluded the speed of light was infinite. Descartes speculated that if the speed of light were found to be finite, his whole system of philosophy might be demolished.[123] In Descartes' derivation of Snell's law, he assumed that even though the speed of light was instantaneous, the denser the medium, the faster was light's speed.[134] Pierre de Fermat derived Snell's law using the opposing assumption, the denser the medium the slower light travelled. Fermat also argued in support of a finite speed of light.[135]

First measurement attempts

In 1629, Isaac Beeckman proposed an experiment in which a person observes the flash of a cannon reflecting off a mirror about one mile (1.6 km) away. In 1638, Galileo Galilei proposed an experiment, with an apparent claim to having performed it some years earlier, to measure the speed of light by observing the delay between uncovering a lantern and its perception some distance away. He was unable to distinguish whether light travel was instantaneous or not, but concluded that if it were not, it must nevertheless be extraordinarily rapid.[115][116] In 1667, the Accademia del Cimento of Florence reported that it had performed Galileo's experiment, with the lanterns separated by about one mile, but no delay was observed.[136] The actual delay in this experiment would have been about 11 microseconds.

The first quantitative estimate of the speed of light was made in 1676 by Rømer.[90][91] From the observation that the periods of Jupiter's innermost moon Io appeared to be shorter when the Earth was approaching Jupiter than when receding from it, he concluded that light travels at a finite speed, and estimated that it takes light 22 minutes to cross the diameter of Earth's orbit. Christiaan Huygens combined this estimate with an estimate for the diameter of the Earth's orbit to obtain an estimate of speed of light of 220000 km/s, 26% lower than the actual value.[119]

In his 1704 book Opticks, Isaac Newton reported Rømer's calculations of the finite speed of light and gave a value of "seven or eight minutes" for the time taken for light to travel from the Sun to the Earth (the modern value is 8 minutes 19 seconds).[137] Newton queried whether Rømer's eclipse shadows were coloured; hearing that they were not, he concluded the different colours travelled at the same speed. In 1729, James Bradley discovered stellar aberration.[92] From this effect he determined that light must travel 10210 times faster than the Earth in its orbit (the modern figure is 10066 times faster) or, equivalently, that it would take light 8 minutes 12 seconds to travel from the Sun to the Earth.[92]

Connections with electromagnetism

In the 19th century Hippolyte Fizeau developed a method to determine the speed of light based on time-of-flight measurements on Earth and reported a value of 315000 km/s.[138] His method was improved upon by Léon Foucault who obtained a value of 298000 km/s in 1862.[102] In the year 1856, Wilhelm Eduard Weber and Rudolf Kohlrausch measured the ratio of the electromagnetic and electrostatic units of charge, 1/√ε0μ0, by discharging a Leyden jar, and found that its numerical value was very close to the speed of light as measured directly by Fizeau. The following year Gustav Kirchhoff calculated that an electric signal in a resistanceless wire travels along the wire at this speed.[139] In the early 1860s, Maxwell showed that, according to the theory of electromagnetism he was working on, electromagnetic waves propagate in empty space[140] at a speed equal to the above Weber/Kohlrausch ratio, and drawing attention to the numerical proximity of this value to the speed of light as measured by Fizeau, he proposed that light is in fact an electromagnetic wave.[141]

"Luminiferous aether"

It was thought at the time that empty space was filled with a background medium called the luminiferous aether in which the electromagnetic field existed. Some physicists thought that this aether acted as a preferred frame of reference for the propagation of light and therefore it should be possible to measure the motion of the Earth with respect to this medium, by measuring the isotropy of the speed of light. Beginning in the 1880s several experiments were performed to try to detect this motion, the most famous of which is the experiment performed by Albert A. Michelson and Edward W. Morley in 1887.[142][143] The detected motion was always less than the observational error. Modern experiments indicate that the two-way speed of light is isotropic (the same in every direction) to within 6 nanometres per second.[144] Because of this experiment Hendrik Lorentz proposed that the motion of the apparatus through the aether may cause the apparatus to contract along its length in the direction of motion, and he further assumed that the time variable for moving systems must also be changed accordingly ("local time"), which led to the formulation of the Lorentz transformation. Based on Lorentz's aether theory, Henri Poincaré (1900) showed that this local time (to first order in v/c) is indicated by clocks moving in the aether, which are synchronized under the assumption of constant light speed. In 1904, he speculated that the speed of light could be a limiting velocity in dynamics, provided that the assumptions of Lorentz's theory are all confirmed. In 1905, Poincaré brought Lorentz's aether theory into full observational agreement with the principle of relativity.[145][146]

Special relativity

In 1905 Einstein postulated from the outset that the speed of light in vacuum, measured by a non-accelerating observer, is independent of the motion of the source or observer. Using this and the principle of relativity as a basis he derived the special theory of relativity, in which the speed of light in vacuum c featured as a fundamental constant, also appearing in contexts unrelated to light. This made the concept of the stationary aether (to which Lorentz and Poincaré still adhered) useless and revolutionized the concepts of space and time.[147][148]

Increased accuracy of c and redefinition of the metre and second

In the second half of the 20th century, much progress was made in increasing the accuracy of measurements of the speed of light, first by cavity resonance techniques and later by laser interferometer techniques. These were aided by new, more precise, definitions of the metre and second. In 1950, Louis Essen determined the speed as 299792.5±3.0 km/s, using cavity resonance.[108] This value was adopted by the 12th General Assembly of the Radio-Scientific Union in 1957. In 1960, the metre was redefined in terms of the wavelength of a particular spectral line of krypton-86, and, in 1967, the second was redefined in terms of the hyperfine transition frequency of the ground state of caesium-133.[149]

In 1972, using the laser interferometer method and the new definitions, a group at the US National Bureau of Standards in Boulder, Colorado determined the speed of light in vacuum to be c = 299792456.2±1.1 m/s. This was 100 times less uncertain than the previously accepted value. The remaining uncertainty was mainly related to the definition of the metre.[Note 15][114] As similar experiments found comparable results for c, the 15th General Conference on Weights and Measures in 1975 recommended using the value 299792458 m/s for the speed of light.[152]

Defined as an explicit constant

In 1983 the 17th meeting of the General Conference on Weights and Measures (CGPM) found that wavelengths from frequency measurements and a given value for the speed of light are more reproducible than the previous standard. They kept the 1967 definition of second, so the caesium hyperfine frequency would now determine both the second and the metre. To do this, they redefined the metre as "the length of the path traveled by light in vacuum during a time interval of 1/299792458 of a second."[89] As a result of this definition, the value of the speed of light in vacuum is exactly 299792458 m/s[153][154] and has become a defined constant in the SI system of units.[11] Improved experimental techniques that, prior to 1983, would have measured the speed of light no longer affect the known value of the speed of light in SI units, but instead allow a more precise realization of the metre by more accurately measuring the wavelength of krypton-86 and other light sources.[155][156]

In 2011, the CGPM stated its intention to redefine all seven SI base units using what it calls "the explicit-constant formulation", where each "unit is defined indirectly by specifying explicitly an exact value for a well-recognized fundamental constant", as was done for the speed of light. It proposed a new, but completely equivalent, wording of the metre's definition: "The metre, symbol m, is the unit of length; its magnitude is set by fixing the numerical value of the speed of light in vacuum to be equal to exactly 299792458 when it is expressed in the SI unit m s−1."[157] This was one of the changes that was incorporated in the 2019 redefinition of the SI base units, also termed the New SI.[158]

See also

Notes

- ^ Exact value: (299792458 × 60 × 60 × 24 / 149597870700) AU/day

- ^ Exact value: (999992651π / 10246429500) pc/y

- ^ It is exact because, by a 1983 international agreement, a metre is defined as the length of the path travelled by light in vacuum during a time interval of 1⁄299792458 second. This particular value was chosen in order to provide a more accurate definition of the metre that still agreed as much as possible with the definition used before. See, for example, the NIST website[2] or the explanation by Penrose.[3] The second is in turn defined to be the length of time occupied by 9192631770 cycles of the radiation emitted by a caesium-133 atom in a transition between two specified energy states.[2]

- ^ The speed of light in imperial and United States customary units is based on an inch of exactly 2.54 cm and is exactly

- 299792458 m/s × 100 cm/m × 1/2.54 in/cm

- ^ However, the frequency of light can depend on the motion of the source relative to the observer, due to the Doppler effect.

- ^ See Michelson–Morley experiment and Kennedy–Thorndike experiment, for example.

- ^ Because neutrinos have a small but non-zero mass, they travel through empty space very slightly more slowly than light. However, because they pass through matter much more easily than light does, there are in theory occasions when the neutrino signal from an astronomical event might reach Earth before an optical signal can, like supernovae.[22]

- ^ Whereas moving objects are measured to be shorter along the line of relative motion, they are also seen as being rotated. This effect, known as Terrell rotation, is due to the different times that light from different parts of the object takes to reach the observer.[24][25]

- ^ It has been speculated that the Scharnhorst effect does allow signals to travel slightly faster than c, but the validity of those calculations has been questioned,[38] and it appears the special conditions in which this effect might occur would prevent one from using it to violate causality.[39]

- ^ A typical value for the refractive index of optical fibre is between 1.518 and 1.538.[75]

- ^ The astronomical unit was defined as the radius of an unperturbed circular Newtonian orbit about the Sun of a particle having infinitesimal mass, moving with an angular frequency of 0.01720209895 radians (approximately 1⁄365.256898 of a revolution) per day.[96]

- ^ Nevertheless, at this degree of precision, the effects of general relativity must be taken into consideration when interpreting the length. The metre is considered to be a unit of proper length, whereas the AU is usually used as a unit of observed length in a given frame of reference. The values cited here follow the latter convention, and are TDB-compatible.[99]

- ^ A detailed discussion of the interferometer and its use for determining the speed of light can be found in Vaughan (1989).[111]

- ^ According to Galileo, the lanterns he used were "at a short distance, less than a mile." Assuming the distance was not too much shorter than a mile, and that "about a thirtieth of a second is the minimum time interval distinguishable by the unaided eye", Boyer notes that Galileo's experiment could at best be said to have established a lower limit of about 60 miles per second for the velocity of light.[116]

- ^ Between 1960 and 1983 the metre was defined as "the length equal to 1650763.73 wavelengths in vacuum of the radiation corresponding to the transition between the levels 2p10 and 5d5 of the krypton 86 atom."[150] It was discovered in the 1970s that this spectral line was not symmetric, which put a limit on the precision with which the definition could be realized in interferometry experiments.[151]

References

- ^ Larson, Ron; Hostetler, Robert P. (2007). Elementary and Intermediate Algebra: A Combined Course, Student Support Edition (4th illustrated ed.). Cengage Learning. p. 197. ISBN 978-0-618-75354-3.

- ^ a b "Definitions of the SI base units". physics.nist.gov. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- ^ Penrose, R (2004). The Road to Reality: A Complete Guide to the Laws of the Universe. Vintage Books. pp. 410–11. ISBN 978-0-679-77631-4.

... the most accurate standard for the metre is conveniently defined so that there are exactly 299792458 of them to the distance travelled by light in a standard second, giving a value for the metre that very accurately matches the now inadequately precise standard metre rule in Paris.

- ^ Gibbs, Philip (1997). "How is the speed of light measured?". The Physics and Relativity FAQ. Archived from the original on 21 August 2015.

- ^ a b Stachel, JJ (2002). Einstein from "B" to "Z" – Volume 9 of Einstein studies. Springer. p. 226. ISBN 978-0-8176-4143-6.

- ^ See, for example:

- Feigenbaum, Mitchell J.; Mermin, N. David (January 1988). "E = mc2". American Journal of Physics. 56 (1): 18–21. doi:10.1119/1.15422. ISSN 0002-9505.

- Uzan, J-P; Leclercq, B (2008). The Natural Laws of the Universe: Understanding Fundamental Constants. Springer. pp. 43–44. ISBN 978-0-387-73454-5.

- ^ Gibbs, P (2004) [1997]. "Why is c the symbol for the speed of light?". Usenet Physics FAQ. University of California, Riverside. Archived from the original on 25 March 2010. Retrieved 16 November 2009. "The origins of the letter c being used for the speed of light can be traced back to a paper of 1856 by Weber and Kohlrausch [...] Weber apparently meant c to stand for 'constant' in his force law, but there is evidence that physicists such as Lorentz and Einstein were accustomed to a common convention that c could be used as a variable for velocity. This usage can be traced back to the classic Latin texts in which c stood for 'celeritas', meaning 'speed'."

- ^ Mendelson, KS (2006). "The story of c". American Journal of Physics. 74 (11): 995–97. Bibcode:2006AmJPh..74..995M. doi:10.1119/1.2238887.

- ^ See for example:

- Lide, DR (2004). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. CRC Press. pp. 2–9. ISBN 978-0-8493-0485-9.

- Harris, JW; et al. (2002). Handbook of Physics. Springer. p. 499. ISBN 978-0-387-95269-7.

- Whitaker, JC (2005). The Electronics Handbook. CRC Press. p. 235. ISBN 978-0-8493-1889-4.

- Cohen, ER; et al. (2007). Quantities, Units and Symbols in Physical Chemistry (3rd ed.). Royal Society of Chemistry. p. 184. ISBN 978-0-85404-433-7.

- ^ International Bureau of Weights and Measures (2006), The International System of Units (SI) (PDF) (8th ed.), p. 112, ISBN 92-822-2213-6, archived (PDF) from the original on 4 June 2021, retrieved 16 December 2021

- ^ a b See, for example:

- Sydenham, PH (2003). "Measurement of length". In Boyes, W (ed.). Instrumentation Reference Book (3rd ed.). Butterworth–Heinemann. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-7506-7123-1.

... if the speed of light is defined as a fixed number then, in principle, the time standard will serve as the length standard ...

- "CODATA value: Speed of Light in Vacuum". The NIST reference on Constants, Units, and Uncertainty. NIST. Retrieved 21 August 2009.

- Jespersen, J; Fitz-Randolph, J; Robb, J (1999). From Sundials to Atomic Clocks: Understanding Time and Frequency (Reprint of National Bureau of Standards 1977, 2nd ed.). Courier Dover. p. 280. ISBN 978-0-486-40913-9.

- Sydenham, PH (2003). "Measurement of length". In Boyes, W (ed.). Instrumentation Reference Book (3rd ed.). Butterworth–Heinemann. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-7506-7123-1.

- ^ Mermin, N. David (2005). It's About Time: Understanding Einstein's Relativity. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 22. ISBN 0-691-12201-6. OCLC 57283944.

- ^ "Nanoseconds Associated with Grace Hopper". National Museum of American History. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

Grace Murray Hopper (1906–1992), a mathematician who became a naval officer and computer scientist during World War II, started distributing these wire "nanoseconds" in the late 1960s in order to demonstrate how designing smaller components would produce faster computers.

- ^ Lawrie, ID (2002). "Appendix C: Natural units". A Unified Grand Tour of Theoretical Physics (2nd ed.). CRC Press. p. 540. ISBN 978-0-7503-0604-1.

- ^ Hsu, L (2006). "Appendix A: Systems of units and the development of relativity theories". A Broader View of Relativity: General Implications of Lorentz and Poincaré Invariance (2nd ed.). World Scientific. pp. 427–28. ISBN 978-981-256-651-5.

- ^ Einstein, A (1905). "Zur Elektrodynamik bewegter Körper". Annalen der Physik (Submitted manuscript) (in German). 17 (10): 890–921. Bibcode:1905AnP...322..891E. doi:10.1002/andp.19053221004. English translation: Perrett, W. Walker, J (ed.). "On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies". Fourmilab. Translated by Jeffery, GB. Retrieved 27 November 2009.

- ^ Hsu, J-P; Zhang, YZ (2001). Lorentz and Poincaré Invariance. Advanced Series on Theoretical Physical Science. Vol. 8. World Scientific. pp. 543ff. ISBN 978-981-02-4721-8.

- ^ a b Zhang, YZ (1997). Special Relativity and Its Experimental Foundations. Advanced Series on Theoretical Physical Science. Vol. 4. World Scientific. pp. 172–73. ISBN 978-981-02-2749-4. Retrieved 23 July 2009.

- ^ d'Inverno, R (1992). Introducing Einstein's Relativity. Oxford University Press. pp. 19–20. ISBN 978-0-19-859686-8.

- ^ Sriranjan, B (2004). "Postulates of the special theory of relativity and their consequences". The Special Theory to Relativity. PHI Learning Pvt. Ltd. pp. 20ff. ISBN 978-81-203-1963-9.

- ^ a b Ellis, George F. R.; Williams, Ruth M. (2000). Flat and Curved Space-times (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 12. ISBN 0-19-850657-0. OCLC 44694623.

- ^ Antonioli, Pietro; et al. (2 September 2004). "SNEWS: the SuperNova Early Warning System". New Journal of Physics. 6: 114–114. doi:10.1088/1367-2630/6/1/114. ISSN 1367-2630.

- ^ Roberts, T; Schleif, S (2007). Dlugosz, JM (ed.). "What is the experimental basis of Special Relativity?". Usenet Physics FAQ. University of California, Riverside. Archived from the original on 15 October 2009. Retrieved 27 November 2009.

- ^ Terrell, J (1959). "Invisibility of the Lorentz Contraction". Physical Review. 116 (4): 1041–5. Bibcode:1959PhRv..116.1041T. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.116.1041.

- ^ Penrose, R (1959). "The Apparent Shape of a Relativistically Moving Sphere". Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society. 55 (1): 137–39. Bibcode:1959PCPS...55..137P. doi:10.1017/S0305004100033776.

- ^ Hartle, JB (2003). Gravity: An Introduction to Einstein's General Relativity. Addison-Wesley. pp. 52–59. ISBN 978-981-02-2749-4.

- ^ Hartle, JB (2003). Gravity: An Introduction to Einstein's General Relativity. Addison-Wesley. p. 332. ISBN 978-981-02-2749-4.

- ^ See, for example:

- Abbott, B.P.; et al. (2017). "Gravitational Waves and Gamma-Rays from a Binary Neutron Star Merger: GW170817 and GRB 170817A". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 848 (2): L13. arXiv:1710.05834. Bibcode:2017ApJ...848L..13A. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/aa920c.

- Cornish, Neil; Blas, Diego; Nardini, Germano (18 October 2017). "Bounding the Speed of Gravity with Gravitational Wave Observations". Physical Review Letters. 119 (16): 161102. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.119.161102.

- Liu, Xiaoshu; He, Vincent F.; Mikulski, Timothy M.; Palenova, Daria; Williams, Claire E.; Creighton, Jolien; Tasson, Jay D. (7 July 2020). "Measuring the speed of gravitational waves from the first and second observing run of Advanced LIGO and Advanced Virgo". Physical Review D. 102 (2): 024028. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.102.024028.

- ^ a b Gibbs, P (1997) [1996]. Carlip, S (ed.). "Is The Speed of Light Constant?". Usenet Physics FAQ. University of California, Riverside. Archived from the original on 2 April 2010. Retrieved 26 November 2009.

- ^

Ellis, GFR; Uzan, J-P (2005). "'c' is the speed of light, isn't it?". American Journal of Physics. 73 (3): 240–27. arXiv:gr-qc/0305099. Bibcode:2005AmJPh..73..240E. doi:10.1119/1.1819929. S2CID 119530637.

The possibility that the fundamental constants may vary during the evolution of the universe offers an exceptional window onto higher dimensional theories and is probably linked with the nature of the dark energy that makes the universe accelerate today.

- ^ Mota, DF (2006). Variations of the Fine Structure Constant in Space and Time (PhD). arXiv:astro-ph/0401631. Bibcode:2004astro.ph..1631M.

- ^ Uzan, J-P (2003). "The fundamental constants and their variation: observational status and theoretical motivations". Reviews of Modern Physics. 75 (2): 403. arXiv:hep-ph/0205340. Bibcode:2003RvMP...75..403U. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.75.403. S2CID 118684485.

- ^

Amelino-Camelia, G (2013). "Quantum Gravity Phenomenology". Living Reviews in Relativity. 16 (1): 5. arXiv:0806.0339. Bibcode:2013LRR....16....5A. doi:10.12942/lrr-2013-5. PMC 5255913. PMID 28179844.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Herrmann, S; et al. (2009). "Rotating optical cavity experiment testing Lorentz invariance at the 10−17 level". Physical Review D. 80 (100): 105011. arXiv:1002.1284. Bibcode:2009PhRvD..80j5011H. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.80.105011. S2CID 118346408.

- ^ Lang, KR (1999). Astrophysical formulae (3rd ed.). Birkhäuser. p. 152. ISBN 978-3-540-29692-8.

- ^ See, for example:

- "It's official: Time machines won't work". Los Angeles Times. 25 July 2011.

- "HKUST Professors Prove Single Photons Do Not Exceed the Speed of Light". The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. 19 July 2011.

- Shanchao Zhang; J.F. Chen; Chang Liu; M.M.T. Loy; G.K.L. Wong; Shengwang Du (16 June 2011). "Optical Precursor of a Single Photon" (PDF). Physical Review Letters. 106 (243602): 243602. Bibcode:2011PhRvL.106x3602Z. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.106.243602. PMID 21770570.

- ^ Fowler, M (March 2008). "Notes on Special Relativity" (PDF). University of Virginia. p. 56. Retrieved 7 May 2010.

- ^ See, for example:

- Ben-Menahem, Shahar (November 1990). "Causality between conducting plates". Physics Letters B. 250 (1–2): 133–138. doi:10.1016/0370-2693(90)91167-A.

- Fearn, H. (10 November 2006). "Dispersion relations and causality: does relativistic causality require that n (ω) → 1 as ω → ∞ ?". Journal of Modern Optics. 53 (16–17): 2569–2581. doi:10.1080/09500340600952085. ISSN 0950-0340.

- Fearn, H. (May 2007). "Can light signals travel faster than c in nontrivial vacua in flat space-time? Relativistic causality II". Laser Physics. 17 (5): 695–699. doi:10.1134/S1054660X07050155. ISSN 1054-660X.

- ^ Liberati, S; Sonego, S; Visser, M (2002). "Faster-than-c signals, special relativity, and causality". Annals of Physics. 298 (1): 167–85. arXiv:gr-qc/0107091. Bibcode:2002AnPhy.298..167L. doi:10.1006/aphy.2002.6233. S2CID 48166.

- ^ Taylor, EF; Wheeler, JA (1992). Spacetime Physics. W.H. Freeman. pp. 74–75. ISBN 978-0-7167-2327-1.

- ^ Tolman, RC (2009) [1917]. "Velocities greater than that of light". The Theory of the Relativity of Motion (Reprint ed.). BiblioLife. p. 54. ISBN 978-1-103-17233-7.

- ^ Hecht, E (1987). Optics (2nd ed.). Addison-Wesley. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-201-11609-0.

- ^ Quimby, RS (2006). Photonics and lasers: an introduction. John Wiley and Sons. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-471-71974-8.

- ^ Wertheim, M (20 June 2007). "The Shadow Goes". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 August 2009.

- ^ a b c d Gibbs, P (1997). "Is Faster-Than-Light Travel or Communication Possible?". Usenet Physics FAQ. University of California, Riverside. Archived from the original on 10 March 2010. Retrieved 20 August 2008.

- ^ See, for example:

- Sakurai, JJ (1994). Tuan, SF (ed.). Modern Quantum Mechanics (Revised ed.). Addison-Wesley. pp. 231–32. ISBN 978-0-201-53929-5.

- Peres, Asher (1993). Quantum Theory: Concepts and Methods. Kluwer. p. 170. ISBN 0-7923-2549-4. OCLC 28854083.

- Caves, Carlton M. (2015). "Quantum Information Science: Emerging No More". OSA Century of Optics. Optica. pp. 320–326. arXiv:1302.1864. ISBN 978-1-943-58004-0.

[I]t was natural to dream that quantum correlations could be used for faster-than-light communication, but this speculation was quickly shot down, and the shooting established the principle that quantum states cannot be copied.

- ^ Muga, JG; Mayato, RS; Egusquiza, IL, eds. (2007). Time in Quantum Mechanics. Springer. p. 48. ISBN 978-3-540-73472-7.

- ^ Hernández-Figueroa, HE; Zamboni-Rached, M; Recami, E (2007). Localized Waves. Wiley Interscience. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-470-10885-7.

- ^ Wynne, K (2002). "Causality and the nature of information". Optics Communications. 209 (1–3): 84–100. Bibcode:2002OptCo.209...85W. doi:10.1016/S0030-4018(02)01638-3. archive

- ^ Rees, M (1966). "The Appearance of Relativistically Expanding Radio Sources". Nature. 211 (5048): 468. Bibcode:1966Natur.211..468R. doi:10.1038/211468a0. S2CID 41065207.

- ^ Chase, IP. "Apparent Superluminal Velocity of Galaxies". Usenet Physics FAQ. University of California, Riverside. Retrieved 26 November 2009.

- ^ Reich, Eugenie Samuel (2 April 2012). "Embattled neutrino project leaders step down". Nature News. doi:10.1038/nature.2012.10371. Retrieved 11 February 2022.

- ^ OPERA Collaboration (12 July 2012). "Measurement of the neutrino velocity with the OPERA detector in the CNGS beam". Journal of High Energy Physics. 2012 (10): 93. arXiv:1109.4897. Bibcode:2012JHEP...10..093A. doi:10.1007/JHEP10(2012)093. S2CID 17652398.

- ^ Harrison, ER (2003). Masks of the Universe. Cambridge University Press. p. 206. ISBN 978-0-521-77351-5.

- ^ Panofsky, WKH; Phillips, M (1962). Classical Electricity and Magnetism. Addison-Wesley. p. 182. ISBN 978-0-201-05702-7.

- ^ See, for example:

- Schaefer, BE (1999). "Severe limits on variations of the speed of light with frequency". Physical Review Letters. 82 (25): 4964–66. arXiv:astro-ph/9810479. Bibcode:1999PhRvL..82.4964S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.82.4964. S2CID 119339066.

- Ellis, J; Mavromatos, NE; Nanopoulos, DV; Sakharov, AS (2003). "Quantum-Gravity Analysis of Gamma-Ray Bursts using Wavelets". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 402 (2): 409–24. arXiv:astro-ph/0210124. Bibcode:2003A&A...402..409E. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20030263. S2CID 15388873.

- Füllekrug, M (2004). "Probing the Speed of Light with Radio Waves at Extremely Low Frequencies". Physical Review Letters. 93 (4): 043901. Bibcode:2004PhRvL..93d3901F. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.93.043901. PMID 15323762.

- Bartlett, D. J.; Desmond, H.; Ferreira, P. G.; Jasche, J. (17 November 2021). "Constraints on quantum gravity and the photon mass from gamma ray bursts". Physical Review D. 104 (10): 103516. arXiv:2109.07850. Bibcode:2021PhRvD.104j3516B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.104.103516. ISSN 2470-0010.

- ^ a b Adelberger, E; Dvali, G; Gruzinov, A (2007). "Photon Mass Bound Destroyed by Vortices". Physical Review Letters. 98 (1): 010402. arXiv:hep-ph/0306245. Bibcode:2007PhRvL..98a0402A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.98.010402. PMID 17358459. S2CID 31249827.

- ^ Sidharth, BG (2008). The Thermodynamic Universe. World Scientific. p. 134. ISBN 978-981-281-234-6.

- ^ Amelino-Camelia, G (2009). "Astrophysics: Burst of support for relativity". Nature. 462 (7271): 291–92. Bibcode:2009Natur.462..291A. doi:10.1038/462291a. PMID 19924200. S2CID 205051022.

- ^ a b c Milonni, Peter W. (2004). Fast light, slow light and left-handed light. CRC Press. pp. 25 ff. ISBN 978-0-7503-0926-4.

- ^ de Podesta, M (2002). Understanding the Properties of Matter. CRC Press. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-415-25788-6.

- ^ "Optical constants of H2O, D2O (Water, heavy water, ice)". refractiveindex.info. Mikhail Polyanskiy. Retrieved 7 November 2017.

- ^ "Optical constants of Soda lime glass". refractiveindex.info. Mikhail Polyanskiy. Retrieved 7 November 2017.

- ^ "Optical constants of C (Carbon, diamond, graphite)". refractiveindex.info. Mikhail Polyanskiy. Retrieved 7 November 2017.

- ^ Cromie, William J. (24 January 2001). "Researchers now able to stop, restart light". Harvard University Gazette. Archived from the original on 28 October 2011. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- ^ Milonni, PW (2004). Fast light, slow light and left-handed light. CRC Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-7503-0926-4.

- ^ Toll, JS (1956). "Causality and the Dispersion Relation: Logical Foundations". Physical Review. 104 (6): 1760–70. Bibcode:1956PhRv..104.1760T. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.104.1760.

- ^ Wolf, Emil (2001). "Analyticity, Causality and Dispersion Relations". Selected Works of Emil Wolf: with commentary. River Edge, N.J.: World Scientific. pp. 577–584. ISBN 978-981-281-187-5. OCLC 261134839.

- ^ Libbrecht, K. G.; Libbrecht, M. W. (December 2006). "Interferometric measurement of the resonant absorption and refractive index in rubidium gas" (PDF). American Journal of Physics. 74 (12): 1055–1060. doi:10.1119/1.2335476. ISSN 0002-9505.

- ^ See, for example:

- Hau, LV; Harris, SE; Dutton, Z; Behroozi, CH (1999). "Light speed reduction to 17 metres per second in an ultracold atomic gas" (PDF). Nature. 397 (6720): 594–98. Bibcode:1999Natur.397..594V. doi:10.1038/17561. S2CID 4423307.

- Liu, C; Dutton, Z; Behroozi, CH; Hau, LV (2001). "Observation of coherent optical information storage in an atomic medium using halted light pulses" (PDF). Nature. 409 (6819): 490–93. Bibcode:2001Natur.409..490L. doi:10.1038/35054017. PMID 11206540. S2CID 1894748.

- Bajcsy, M; Zibrov, AS; Lukin, MD (2003). "Stationary pulses of light in an atomic medium". Nature. 426 (6967): 638–41. arXiv:quant-ph/0311092. Bibcode:2003Natur.426..638B. doi:10.1038/nature02176. PMID 14668857. S2CID 4320280.

- Dumé, B (2003). "Switching light on and off". Physics World. Institute of Physics. Archived from the original on 5 December 2008. Retrieved 8 December 2008.

- ^ See, for example:

- Chiao, R. Y. (1993). "Superluminal (but causal) propagation of wave packets in transparent media with inverted atomic populations". Physical Review A. 48: R34. Bibcode:1993PhRvA..48...34C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.48.R34.

- Wang, L. J.; Kuzmich, A.; Dogariu, A. (2000). "Gain-assisted superluminal light propagation". Nature. 406: 277–279. doi:10.1038/35018520.

- Whitehouse, D (19 July 2000). "Beam Smashes Light Barrier". BBC News. Retrieved 9 February 2022.

- Gbur, Greg (26 February 2008). "Light breaking its own speed limit: how 'superluminal' shenanigans work". Retrieved 9 February 2022.

- ^ Cherenkov, Pavel A. (1934). "Видимое свечение чистых жидкостей под действием γ-радиации" [Visible emission of pure liquids by action of γ radiation]. Doklady Akademii Nauk SSSR. 2: 451. Reprinted: Cherenkov, P.A. (1967). "Видимое свечение чистых жидкостей под действием γ-радиации" [Visible emission of pure liquids by action of γ radiation]. Usp. Fiz. Nauk. 93 (10): 385. doi:10.3367/ufnr.0093.196710n.0385., and in A.N. Gorbunov; E.P. Čerenkova, eds. (1999). Pavel Alekseyevich Čerenkov: Chelovek i Otkrytie [Pavel Alekseyevich Čerenkov: Man and Discovery]. Moscow: Nauka. pp. 149–53.

- ^ Parhami, B (1999). Introduction to parallel processing: algorithms and architectures. Plenum Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-306-45970-2.

- ^ Imbs, D; Raynal, Michel (2009). Malyshkin, V (ed.). Software Transactional Memories: An Approach for Multicore Programming. 10th International Conference, PaCT 2009, Novosibirsk, Russia, 31 August – 4 September 2009. Springer. p. 26. ISBN 978-3-642-03274-5.

- ^ Midwinter, JE (1991). Optical Fibers for Transmission (2nd ed.). Krieger Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-89464-595-2.

- ^ "Theoretical vs real-world speed limit of Ping". Pingdom. June 2007. Archived from the original on 2 September 2010. Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- ^ "Day 4: Lunar Orbits 7, 8 and 9". The Apollo 8 Flight Journal. NASA. Archived from the original on 4 January 2011. Retrieved 16 December 2010.

- ^ "Communications". Mars 2020 Mission Perseverence Rover. NASA. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- ^ a b "Hubble Reaches the "Undiscovered Country" of Primeval Galaxies" (Press release). Space Telescope Science Institute. 5 January 2010.

- ^ "The Hubble Ultra Deep Field Lithograph" (PDF). NASA. Retrieved 4 February 2010.

- ^ Mack, Katie (2021). The End of Everything (Astrophysically Speaking). London: Penguin Books. pp. 18–19. ISBN 978-0-141-98958-7. OCLC 1180972461.

- ^ "The IAU and astronomical units". International Astronomical Union. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

- ^ Further discussion can be found at "StarChild Question of the Month for March 2000". StarChild. NASA. 2000. Retrieved 22 August 2009.

- ^ Dickey, JO; et al. (July 1994). "Lunar Laser Ranging: A Continuing Legacy of the Apollo Program" (PDF). Science. 265 (5171): 482–90. Bibcode:1994Sci...265..482D. doi:10.1126/science.265.5171.482. PMID 17781305. S2CID 10157934.

- ^ Standish, EM (February 1982). "The JPL planetary ephemerides". Celestial Mechanics. 26 (2): 181–86. Bibcode:1982CeMec..26..181S. doi:10.1007/BF01230883.

- ^ Berner, JB; Bryant, SH; Kinman, PW (November 2007). "Range Measurement as Practiced in the Deep Space Network" (PDF). Proceedings of the IEEE. 95 (11): 2202–2214. doi:10.1109/JPROC.2007.905128. S2CID 12149700.

- ^ "Time is money when it comes to microwaves". Financial Times. 10 May 2013. Retrieved 25 April 2014.

- ^ Buchanan, Mark (11 February 2015). "Physics in finance: Trading at the speed of light". Nature. 518 (7538): 161–163. Bibcode:2015Natur.518..161B. doi:10.1038/518161a. PMID 25673397.

- ^ a b c "Resolution 1 of the 17th CGPM". BIPM. 1983. Retrieved 23 August 2009.

- ^ a b c Cohen, IB (1940). "Roemer and the first determination of the velocity of light (1676)". Isis. 31 (2): 327–79. doi:10.1086/347594. hdl:2027/uc1.b4375710. S2CID 145428377.

- ^ a b c

"Demonstration tovchant le mouvement de la lumiere trouvé par M. Rŏmer de l'Académie Royale des Sciences" [Demonstration to the movement of light found by Mr. Römer of the Royal Academy of Sciences] (PDF). Journal des sçavans (in French): 233–36. 1676.

Translated in "A demonstration concerning the motion of light, communicated from Paris, in the Journal des Sçavans, and here made English". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. 12 (136): 893–95. 1677. Bibcode:1677RSPT...12..893.. doi:10.1098/rstl.1677.0024.

Reproduced in Hutton, C; Shaw, G; Pearson, R, eds. (1809). "On the Motion of Light by M. Romer". The Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, from Their Commencement in 1665, in the Year 1800: Abridged. Vol. II. From 1673 to 1682. London: C. & R. Baldwin. pp. 397–98.

The account published in Journal des sçavans was based on a report that Rømer read to the French Academy of Sciences in November 1676 (Cohen, 1940, p. 346). - ^ a b c d Bradley, J (1729). "Account of a new discovered Motion of the Fix'd Stars". Philosophical Transactions. 35: 637–60.

- ^ Duffett-Smith, P (1988). Practical Astronomy with your Calculator. Cambridge University Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-521-35699-2. Extract of page 62

- ^ a b "Resolution B2 on the re-definition of the astronomical unit of length" (PDF). International Astronomical Union. 2012.

- ^ "Supplement 2014: Updates to the 8th edition (2006) of the SI Brochure" (PDF). The International System of Units. International Bureau of Weights and Measures: 14. 2014.

- ^ International Bureau of Weights and Measures (2006), The International System of Units (SI) (PDF) (8th ed.), p. 126, ISBN 92-822-2213-6, archived (PDF) from the original on 4 June 2021, retrieved 16 December 2021

- ^ Brumfiel, Geoff (14 September 2012). "The astronomical unit gets fixed". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2012.11416. ISSN 1476-4687.

- ^ See the following:

- Pitjeva, EV; Standish, EM (2009). "Proposals for the masses of the three largest asteroids, the Moon–Earth mass ratio and the Astronomical Unit". Celestial Mechanics and Dynamical Astronomy. 103 (4): 365–72. Bibcode:2009CeMDA.103..365P. doi:10.1007/s10569-009-9203-8. S2CID 121374703.

- "Astrodynamic Constants". Solar System Dynamics. Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 10 February 2022.

- ^ a b IAU Working Group on Numerical Standards for Fundamental Astronomy. "IAU WG on NSFA Current Best Estimates". US Naval Observatory. Archived from the original on 8 December 2009. Retrieved 25 September 2009.

- ^ "NPL's Beginner's Guide to Length". UK National Physical Laboratory. Archived from the original on 31 August 2010. Retrieved 28 October 2009.