J. K. Rowling

J. K. Rowling | |

|---|---|

Rowling in 2010 | |

| Born | Joanne Rowling 31 July 1965 Yate, Gloucestershire, England |

| Pen name |

|

| Occupation |

|

| Alma mater | University of Exeter Moray House |

| Period | 1997–present |

| Genre | |

| Spouse |

|

| Children | 3 |

| Signature | |

| |

| Website | |

| jkrowling | |

Joanne Rowling, CH OBE HonFRSE FRCPE FRSL (/ˈroʊlɪŋ/ ROH-ling;[1] born 31 July 1965), is a British author and philanthropist known by her pen name J. K. Rowling. She wrote a seven-volume children's fantasy series, Harry Potter, published from 1997 to 2007. The series has been enormously successful: it has sold over 500 million copies, been translated into at least 70 languages, and spawned a global media franchise including films and video games. The Casual Vacancy (2012) was her first novel for adults. She writes Cormoran Strike, an ongoing crime fiction series, as Robert Galbraith.

Born in Yate, Rowling graduated from the University of Exeter in 1987 and began working temp jobs as a bilingual secretary. In 1990, the idea for the characters of Harry Potter came to her while she waited on a delayed train. The seven-year period that followed saw the death of her mother from multiple sclerosis, which deeply affected Rowling and her writing; the birth of her first child; and divorce from her first husband. She wrote the first Harry Potter novel, Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone (1997), while experiencing relative poverty as a single parent. Forbes named her the world's highest-paid author in 2008, 2017 and 2019.

Rowling concluded the Harry Potter series with Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows (2007). The novels follow a boy named Harry Potter as he attends Hogwarts, a school for wizards, and battles Lord Voldemort. Death and the divide between good and evil are the central themes of the series. Its influences include the Bildungsroman (coming-of-age story), school stories, fairy tales, and Christian allegory. The series revived fantasy as a genre in the children's market, spawned a host of imitators, and inspired an active fandom. Critical reception has been more mixed. Many reviewers see Rowling's writing as conventional; some regard her portrayal of gender and social division as regressive. There were also religious debates over Harry Potter.

Rowling has won many accolades for her work. She was named to the Order of the British Empire and was appointed a member of the Order of the Companions of Honour for services to literature and philanthropy. Harry Potter brought her wealth and recognition that she has used to advance philanthropic endeavours and political causes. She co-founded the charity Lumos and established the Volant Charitable Trust, named for her mother. Rowling's charitable giving centres on medical causes and supporting at-risk women and children. In politics, she has donated to Britain's Labour Party and opposed Scottish independence and Brexit. Since late 2019, she has publicly expressed her opinions on transgender people and related civil rights. These have been criticised as transphobic by LGBT rights organisations and some feminists, but have received support from other feminists and individuals.

Name

Although she writes under the pen name J. K. Rowling, before her remarriage her name was Joanne Rowling,[2] or Jo.[3] At birth, she had no middle name.[2] Staff at Bloomsbury Publishing asked that she use two initials rather than her full name, anticipating that young boys – their target audience – would not want to read a book written by a woman.[2] She chose K (for Kathleen) as the second initial of her pen name, from her paternal grandmother, and because of the ease of pronunciation of two consecutive letters.[4] Following her 2001 remarriage,[5] she has sometimes used the name Joanne Murray when conducting personal business.[6]

Life and career

Early life and family

Joanne Rowling was born on 31 July 1965 at Cottage Hospital in Yate.[8][a] Her parents Anne (née Volant) and Peter "Pete" James Rowling had met the previous year on a train, sharing a trip from King's Cross Station, London, to their naval postings at Arbroath, Scotland. Anne was in the WREN and Pete was with the British Royal Navy.[14] They came from middle-class backgrounds;[10] Pete was the son of a machine-tool setter who later opened a grocery shop.[15] They left the navy life and sought a country home to raise the baby they were expecting,[15] and married on 14 March 1965[10] when both were 19.[16] The Rowlings settled in Yate,[17] where Pete started work as an assembly-line production worker at the Bristol Siddeley factory.[15] Pete's company became part of Rolls-Royce,[18] and he worked his way into management as a chartered engineer.[19] Anne later worked as a science technician.[20] Neither Anne nor Pete attended university.[21]

Joanne has a sister, Dianne, two years younger than her.[10] When Joanne was four, the family moved to Winterbourne, Gloucestershire.[16][22] She began at St Michael's Church of England Primary School in Winterbourne when she was five.[10][b] The Rowlings lived near a family called Potter – a name Joanne always liked.[25][c] Anne loved to read and their homes were filled with books.[26] Pete read The Wind in the Willows to his daughters,[27] while Anne introduced them to the animals in Richard Scarry's books.[28] Joanne's first attempt at writing, a story called "Rabbit" composed when she was six, was inspired by Scarry's creatures.[28]

When Rowling was about nine, the family purchased the historic Church Cottage in Tutshill.[29][d] In 1974, Rowling began attending the nearby Church of England School.[33] Biographer Sean Smith describes her teacher Sylvia Morgan as a "battleaxe"[34] who "struck fear into the hearts of the children";[35] she seated Rowling in "dunces' row" after she performed poorly on an arithmetic test.[36][e] In 1975, Rowling joined a Brownies pack. Its special events and parties, and the pack groups (Fairies, Pixies, Sprites, Elves, Gnomes and Imps) provided a magical world away from the stern Morgan.[37] When she was eleven[38] or twelve, she wrote a short story, "The Seven Cursed Diamonds".[39] She later described herself during this period as "the epitome of a bookish child – short and squat, thick National Health glasses, living in a world of complete daydreams".[40]

Secondary school and university

Rowling's secondary school was Wyedean School and College, a state school she began attending at age eleven[41] and where she was bullied.[42][43] Rowling was inspired by her favourite teacher, Lucy Shepherd, who taught the importance of structure and precision in writing.[44][45] Smith writes that Rowling "craved to play heavy electric guitar",[46] and describes her as "intelligent yet shy".[47] According to her teacher Dale Neuschwander, she impressed her teachers with her imagination.[48] When she was a young teenager, Rowling's great-aunt gave her Hons and Rebels, the autobiography of the civil rights activist Jessica Mitford.[49] Mitford became Rowling's heroine, and she read all her books.[50]

Anne had a strong influence on her daughter.[10] Early in Rowling's life, the support of her mother and sister instilled confidence and enthusiasm for storytelling.[51] Anne was a creative and accomplished cook,[52][f] who helped lead her daughters' Brownie activities,[55] and took a job in the chemistry department at Wyedean while her daughters were there.[20] The three walked to and from school, sharing stories about their day, more like sisters than mother and daughters.[46][56] John Nettleship, the head of science at Wyedean, described Anne as "absolutely brilliant, a sparkling character ... very imaginative".[11]

Anne Rowling was diagnosed with a "virulent strain" of multiple sclerosis when she was 34[57] or 35 and Jo was 15,[58] and had to give up her job.[59] Rowling's home life was complicated by her mother's illness[60] and a strained relationship with her father.[61] Rowling later said "home was a difficult place to be",[62] and that her teenage years were unhappy.[31] In 2020, she wrote that her father would have preferred a son and described herself as having severe obsessive–compulsive disorder in her teens.[63] She began to smoke, took an interest in alternative rock,[57] and adopted Siouxsie Sioux's back-combed hair and black eyeliner.[11] Sean Harris, her best friend in the Upper Sixth, owned a turquoise Ford Anglia that provided an escape from her difficult home life and the means for Harris and Rowling to broaden their activities.[64][g]

Living in a small town with pressures at home, Rowling became more interested in her school work.[57] Steve Eddy, her first secondary school English teacher, remembers her as "not exceptional" but "one of a group of girls who were bright, and quite good at English".[31] Rowling took A-levels in English, French and German, achieving two As and a B and was named head girl at Wyedean.[67] She applied to Oxford University in 1982 but was rejected.[10] Biographers attribute her rejection to privilege, as she had attended a state school rather than a private one.[68][69]

Rowling always wanted to be a writer,[70] but chose to study French and the classics at the University of Exeter for practical reasons, influenced by her parents who thought job prospects would be better with evidence of bilingualism.[71] She later stated that Exeter was not initially what she expected ("to be among lots of similar people – thinking radical thoughts") but that she enjoyed herself after she met more people like her.[50] She was an average student at Exeter, described by biographers as prioritising her social life over academics, lacking ambition and enthusiasm.[72][73] Rowling recalls doing little work at university, preferring to read Dickens and Tolkien.[31] She earned a BA in French from Exeter,[74] graduating in 1987 after a year of study in Paris.[75]

Inspiration and mother's death

After university, Rowling moved to a flat in Clapham Junction with friends,[76] and took a course to become a bilingual secretary.[10] While she was working temp jobs in London, Amnesty International hired her to document human rights issues in French-speaking Africa.[77] She began writing adult novels while working as a temp, although they were never published.[11][78] In 1990, she planned to move with her boyfriend to Manchester,[16] and frequently took long train trips to visit.[38] In mid-1990, she was on a train delayed by four hours from Manchester to London,[79] when the characters Harry Potter, Ron Weasley, and Hermione Granger came plainly into her mind.[80] Having no pen or paper allowed her to fully explore the characters and their story in her imagination before she reached her flat and began to write.[79]

Rowling moved to Manchester around November 1990.[50] She described her time in Manchester, where she worked for the Chamber of Commerce[38] and at Manchester University in temp jobs,[81] as a "year of misery".[82] Her mother died of multiple sclerosis on 30 December 1990.[83] At the time, she was writing Harry Potter and had never told her mother about it.[84] She had a difficult relationship with her father,[31] and her mother's death heavily affected Rowling's writing.[85] She later said that the Mirror of Erised is about her mother's death,[86] and noted an "evident parallelism" between Harry confronting his own mortality and her life.[87]

The pain of the loss of her mother was compounded when some of the personal effects her mother had left her were stolen.[50] With the end of the relationship with her boyfriend, and "being made redundant from an office job in Manchester", Rowling described herself as being in a state of "fight or flight".[31] An advertisement in The Guardian led her to move to Porto, Portugal, in November 1991 to teach night-classes in English as a foreign language,[88] writing during the day.[31]

Marriage, divorce, and single parenthood

Five months after arriving in Porto, Rowling met the Portuguese television journalist Jorge Arantes in a bar and found that they shared an interest in Jane Austen.[89] By mid-1992, they were planning a trip to London to introduce Arantes to Rowling's family, when she had a miscarriage.[90] The relationship was troubled, yet they married on 16 October 1992.[91][h] Their daughter Jessica Isabel Rowling Arantes (named after Jessica Mitford[i]) was born on 27 July 1993 in Portugal.[11] By this time, Rowling had finished the first three chapters of Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone – almost as they were eventually published – and had drafted the rest of the novel.[93]

Rowling experienced domestic abuse during her marriage.[63][94] Arantes said in June 2020 that he had slapped her and did not regret it.[95] Rowling described the marriage as "short and catastrophic".[38] Rowling and Arantes separated on 17 November 1993 after Arantes threw her out of the house; she returned with the police to retrieve Jessica and went into hiding for two weeks before she left Portugal.[96] In late 1993, with a draft of Harry Potter in her suitcase,[31] Rowling moved with her daughter to Edinburgh, Scotland,[8] planning to stay with her sister through Christmas.[50]

Biographer Smith raises the question of why Rowling chose to stay with her sister rather than her father.[97] Rowling has spoken of an estrangement from her father, stating in an interview with Oprah Winfrey that "It wasn't a good relationship from my point of view for a very long time but I had a need to please and I kept that going for a long time and then there ... just came a point at which I had to pull up and say I can't do this anymore."[61] Pete had married his secretary within two years of Anne's death,[98] and The Scotsman reported in 2003 that "[t]he speed of his decision to move in with his secretary ... distressed both sisters and a fault-line now separated them and their father."[11] Rowling said in 2012 that they had not spoken in the last nine years.[31]

Rowling sought government assistance and got £69 (US$103.50) per week from Social Security; not wanting to burden her recently married sister, she moved to a flat that she characterised as mouse-ridden.[99] She later described her economic status as being "poor as it is possible to be in modern Britain, without being homeless".[31] Seven years after graduating from university, she saw herself as a failure.[100] Tison Pugh writes that the "grinding effects of poverty, coupled with her concern for providing for her daughter as a single parent, caused great hardship".[38] Her marriage had failed and she was jobless with a dependent child, but she later described this as "liberating" her to focus on writing.[100] She has said that "Jessica kept me going".[98] Her old school friend, Sean Harris, loaned her £600 ($900), which allowed her to move to a flat in Leith,[101] where she finished Philosopher's Stone.[101]

Arantes arrived in Scotland in March 1994 seeking both Rowling and Jessica.[11][102] On 15 March 1994, Rowling sought an action of interdict (order of restraint) and Arantes returned to Portugal.[11][103] Early in the year, Rowling began to experience a deep depression[104] and sought medical help when she contemplated suicide.[38][j] With nine months of therapy, things gradually improved.[104] She filed for divorce on 10 August 1994[106] and the divorce was finalised on 26 June 1995.[107]

Rowling wanted to finish the book before enrolling in a teacher training course, fearing she might not be able to finish once she started the course.[50] She often wrote in cafés,[108] including Nicolson's, owned in partnership by her brother-in-law.[109] Secretarial work brought in £15 ($22.50) per week, but she would lose government benefits if she earned more.[110] In the summer of 1995, a friend gave her money that allowed her to go off benefits and enrol full-time in school.[111] Still needing money and expecting to make a living by teaching,[112] Rowling began a teacher training course in August 1995 at Moray House School of Education[113] after completing her first novel.[114] She earned her teaching certificate in July 1996.[2] Rowling later said that writing the first Harry Potter book had saved her life and that her concerns about "love, loss, separation, death ... are reflected in the first book".[87]

Publishing Harry Potter

Rowling completed Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone in June 1995.[115] The initial draft included an illustration of Harry by a fireplace, showing a lightning-shaped scar on his forehead.[116] Following an enthusiastic report from an early reader,[117] Christopher Little Literary Agency agreed to represent Rowling. It was submitted to twelve publishers, all of which rejected the manuscript.[11] Barry Cunningham, who ran the children's literature department at Bloomsbury Publishing, eventually bought it.[118] Nigel Newton, who headed Bloomsbury at the time, decided to go ahead with the manuscript after his eight-year-old daughter finished one chapter and wanted to keep reading.[38][119] Although Bloomsbury agreed to publish the book, one of Rowling's favourite memories was of Cunningham telling her, "You'll never make any money out of children's books, Jo."[120] Rowling was awarded a writer's grant by the Scottish Arts Council[k] to support her childcare costs and finances before Philosopher's Stone's publication, and to aid in writing the sequel, Chamber of Secrets.[121][122] In June 1997, Bloomsbury published Philosopher's Stone with an initial print run of 500 copies.[123][124] Before Chamber of Secrets was published, Rowling had received only £2,800 ($4,200) in royalties.[125]

Philosopher's Stone introduces Harry Potter. Harry is a wizard who lives with his non-magical relatives until his eleventh birthday, when he is invited to attend Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry.[126][127] Rowling wrote six sequels, which follow Harry's adventures at Hogwarts with friends Hermione Granger and Ron Weasley and his attempts to defeat Lord Voldemort, who killed Harry's parents when he was a child.[126] In Philosopher's Stone, Harry foils Voldemort's plan to acquire an elixir of life; in Deathly Hallows, the final book, he kills Voldemort.[126]

Rowling received the news that the US rights were being auctioned at the Bologna Children's Book Fair.[128] To her surprise and delight, Scholastic Corporation bought the rights for $105,000.[129] She bought an apartment in Edinburgh with the money from the sale.[130] Arthur A. Levine, head of the imprint at Scholastic pushed for a name change. He wanted Harry Potter and the School of Magic; as a compromise Rowling suggested Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone.[131] Sorcerer's Stone was released in the United States in September 1998.[132] It was not widely reviewed, but the reviews it received were generally positive.[133] Sorcerer's Stone became a New York Times bestseller by December.[134]

The next three books in the series were released in quick succession between 1998 and 2000: Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (1998), Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (1999), and Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire (2000), each selling millions of copies.[135] When Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix was delayed and had not appeared by 2002, rumours circulated that Rowling was suffering writer's block.[136] It was published in June 2003, selling millions of copies on the first day.[137] Two years later, Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince was released in July, again selling millions of copies on the first day.[138] The series ended with Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, published in July 2007.[139]

Films

In 1999, Warner Bros. purchased film rights to the first two Harry Potter novels for a reported $1 million.[140][141] Rowling accepted the offer with the provision that the studio only produce Harry Potter films based on books she authored,[142] while retaining the right to final script approval,[143] and some control over merchandising.[141] Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone, an adaptation of the first Harry Potter book, was released in November 2001.[144] Steve Kloves wrote the screenplays for all but the fifth film,[145] with Rowling's assistance, ensuring that his scripts kept to the plots of the novels.[146] The film series concluded with Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, which was adapted in two parts; part one was released on 19 November 2010,[147] and part two followed on 15 July 2011.[148]

Warner Bros. announced an expanded relationship with Rowling in 2013, including a planned series of films about her character Newt Scamander, author of Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them.[149] The first film of five, a prequel to the Harry Potter series, set roughly 70 years earlier, was released in November 2016.[150] Rowling wrote the screenplay, which was released as a book.[151] Crimes of Grindelwald was released in November 2018.[152] Secrets of Dumbledore is scheduled for release on 15 April 2022.[153]

Religion, wealth and remarriage

By 1998, Rowling was portrayed in the media as a "penniless divorcee hitting the jackpot".[125] According to biographer Smith, the publicity became effective marketing for Harry Potter.[125] But her journey from living on benefits to wealth brought, along with fame, concerns from parents about the books' portrayals of the occult and gender.[154] Ultimately, Smith says that these concerns served to "increase her public profile rather than damage it".[155]

Rowling identifies as a Christian.[156] Although she grew up next door to her church,[157] accounts of the family's church attendance differ.[l] She began attending a Church of Scotland congregation, where Jessica was christened, around the time she was writing Harry Potter.[159] In a 2012 interview, she said she belonged to the Scottish Episcopal Church.[160] Rowling has stated that she believes in God,[161] but has experienced doubt[162] and that her struggles with faith play a part in her books.[87] She does not believe in magic or witchcraft.[156][161]

Rowling married Neil Murray, a doctor, in 2001.[5] The couple intended to marry in July of that year in the Galapagos; after a leak to the press, they delayed their wedding plans and changed their vacation destination to Mauritius.[163] After the UK Press Complaints Commission ruled that a magazine had breached Jessica's privacy when the eight-year-old was included in a photograph of the family vacationing together,[164][165] Murray and Rowling sought a more private and quiet place to live and work.[166] Rowling purchased Killiechassie House and its estate in Perthshire, Scotland.[167] On 26 December 2001, the couple had a small, private wedding there, officiated by an Episcopalian priest who travelled from Edinburgh.[5] Their son, David Gordon Rowling Murray, was born in 2003,[168] and their daughter Mackenzie Jean Rowling Murray was born in 2005.[169]

In 2004, Forbes named Rowling "the first billion-dollar author".[170] Rowling denied that she was a billionaire in a 2005 interview.[171] By 2012, Forbes concluded she was no longer a billionaire due to her charitable donations and high UK taxes.[172] She was named the world's highest paid author by Forbes in 2008,[173] 2017[174] and 2019.[175] Her UK sales total in excess of £238 million, making her the best-selling living author in Britain.[176] The 2021 Sunday Times Rich List estimated Rowling's fortune at £820 million, ranking her as the 196th-richest person in the UK.[177] As of 2020, she also owns a £4.5 million Georgian house in Kensington and a £2 million home in Edinburgh.[178]

Adult fiction and Robert Galbraith

In mid-2011, Rowling left Christopher Little Literary Agency and followed her agent Neil Blair to the Blair Partnership. He represented her for the publication of The Casual Vacancy, released in September 2012 by Little, Brown and Company.[179] It was Rowling's first since Harry Potter ended, and her first book for adults.[180] A contemporary take on 19th-century British fiction about village life,[181] Casual Vacancy was promoted as a black comedy,[182] while the critic Ian Parker described it as a "rural comedy of manners".[31] It was adapted to a miniseries co-created by the BBC and HBO.[183]

Little, Brown published The Cuckoo's Calling, the purported début novel of Robert Galbraith, in April 2013.[184] It initially sold 1,500 copies in hardback.[185] After an investigation prompted by discussion on Twitter, the journalist Richard Brooks contacted Rowling's agent, who confirmed Galbraith was Rowling's pseudonym.[185] Rowling later said she enjoyed working as Robert Galbraith,[186] a name she took from Robert F. Kennedy, a personal hero, and Ella Galbraith, a name she invented for herself in childhood.[187] After the revelation, sales of Cuckoo's Calling escalated.[188]

Continuing the Cormoran Strike series of detective novels, The Silkworm was released in 2014;[189] Career of Evil in 2015;[190] Lethal White in 2018;[191] and Troubled Blood in 2020.[192] The eponymous Cormoran Strike is a disabled veteran of the War in Afghanistan with a prosthetic leg;[193] Cormoran is unfriendly and sometimes oblivious, but acts with a deep moral sensibility.[194] BBC One released Strike, a television adaptation of the Cormoran Strike novels starring Tom Burke, in 2017. The series was picked up by HBO for distribution in the United States and Canada.[195]

Later Harry Potter works

Pottermore, a website with information and stories about characters in the Harry Potter universe, launched in 2011. On its release, Pottermore was rooted in the Harry Potter novels, tracing the series's story in an interactive format. Its brand was associated with Rowling: she introduced the site in a video as a shared media environment to which she and Harry Potter fans would contribute. The site was substantially revised in 2015 to resemble an encyclopedia of Harry Potter. Beyond encyclopedia content, the post-2015 Pottermore included promotions for Warner Bros. films including Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them.[196][197]

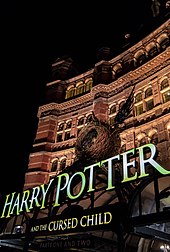

Harry Potter and the Cursed Child premiered in the West End in May 2016[198] and on Broadway in July.[199] At its London premiere, Rowling confirmed that she would not write any more Harry Potter books.[200] Rowling collaborated with writer Jack Thorne and director John Tiffany.[198][199] Cursed Child's script was published as a book in July 2016.[201] The play follows the friendship between Harry's son Albus and Scorpius Malfoy, Draco Malfoy's son, at Hogwarts.[199]

Children's stories

The Ickabog was Rowling's first book aimed at children since Harry Potter.[202] The eponymous Ickabog is a monster that turns out to be real; a group of children find out the truth about the Ickabog and save the day.[203][204] Rowling released The Ickabog for free online in mid-2020, during the COVID-19 lockdown in the United Kingdom.[205] She began writing it as early as 2009 but set it aside to focus on other works including Casual Vacancy.[205] Scholastic held a competition to select children's art for the print edition, which was published in the US and Canada on 10 November 2020.[206] Profits went to charities focused on COVID-19 relief.[202][207]

In The Christmas Pig, a young boy loses his favourite stuffed animal, a pig, and the Christmas Pig guides him through the fantastical Land of the Lost to retrieve it.[208] The novel was published on 12 October 2021 in the US[209] and became a bestseller in the UK[210] and the US.[211]

Influences

Rowling has named Jessica Mitford as her greatest influence. She said Mitford had "been my heroine since I was 14 years old, when I overheard my formidable great-aunt discussing how Mitford had run away at the age of 19 to fight with the Reds in the Spanish Civil War", and that what inspired her about Mitford was that she was "incurably and instinctively rebellious, brave, adventurous, funny and irreverent, she liked nothing better than a good fight, preferably against a pompous and hypocritical target".[212] As a child, Rowling read Lewis's The Chronicles of Narnia, Goudge's The Little White Horse, Manxmouse by Paul Gallico, and books by E. Nesbit and Noel Streatfeild.[213] Rowling describes Jane Austen as her "favourite author of all time".[214]

Rowling acknowledges Homer, Geoffrey Chaucer, and William Shakespeare as literary influences.[215] Scholars agree that Harry Potter is heavily influenced by the children's fantasy of writers such as C. S. Lewis, J. R. R. Tolkien, Elizabeth Goudge, Ursula K. Le Guin, Dianna Wynne Jones, and E. Nesbit.[216] According to the critic Beatrice Groves, Harry Potter is also "rooted in the Western literary tradition", including the classics.[217] Commentators also note similarities to the children's stories of Enid Blyton and Roald Dahl.[218] Rowling expresses admiration for Lewis, in whose writing battles between good and evil are also prominent, but rejects any connection with Dahl.[219]

Earlier works prominently featuring characters who learn to use magic include Le Guin's Earthsea series, in which a school of wizardry also appears, and the Chrestomanci books by Jones.[220][221] Rowling's setting of a "school of witchcraft and wizardry" departs from the still older tradition of protagonists as apprentices to magicians, exemplified by The Sorcerer's Apprentice: yet this trope does appear in Harry Potter, when Harry receives individual instruction from Remus Lupin and other teachers.[220] Rowling also draws on the tradition of stories set in boarding schools, a major example of which is Thomas Hughes's 1857 volume Tom Brown's School Days.[222][223]

Style and themes

Style and allusions

Rowling is known primarily as an author of fantasy and children's literature.[224] Her writing in other genres including literary fiction and murder mystery has received less critical attention.[225] Rowling's most famous work, Harry Potter, has been defined as a fairy tale, a Bildungsroman and a boarding-school story.[226][227] Her other writings have been described by Pugh as gritty contemporary fiction with historical influences (The Casual Vacancy) and hardboiled detective fiction (Cormoran Strike).[228]

In Harry Potter, Rowling juxtaposes the extraordinary against the ordinary.[229] Her narrative features two worlds – the mundane and the fantastic – but it differs from typical portal fantasy in that its magical elements stay grounded in the everyday.[230] Paintings move and talk; books bite readers; letters shout messages; and maps show live journeys,[229][231] making the wizarding world "both exotic and cosily familiar" according to the scholar Catherine Butler.[231] This blend of realistic and romantic elements extends to Rowling's characters. Their names often include morphemes that correspond to their characteristics: Malfoy is difficult, Filch unpleasant and Lupin a werewolf.[232][233] Harry is ordinary and relatable, with down-to-earth features such as wearing broken glasses;[234] Roni Natov terms him an "everychild".[235] These elements serve to highlight Harry when he is heroic, making him both an everyman and a fairytale hero.[234][236]

Arthurian, Christian and fairytale motifs are frequently found in Rowling's writing. Harry's ability to draw the Sword of Gryffindor from the Sorting Hat resembles the Arthurian sword in the stone legend.[237] His life with the Dursleys has been compared to Cinderella.[238] Like C. S. Lewis's The Chronicles of Narnia, Harry Potter contains Christian symbolism and allegory. The series has been viewed as a Christian moral fable in the psychomachia tradition, in which stand-ins for good and evil fight for supremacy over a person's soul.[239] Children's literature critic Joy Farmer sees parallels between Harry and Jesus Christ.[240] Comparing Rowling with Lewis, she argues that "magic is both authors' way of talking about spiritual reality".[241] According to Maria Nikolajeva, Christian imagery is particularly strong in the final scenes of the series: Harry dies in self-sacrifice and Voldemort delivers an "ecce homo" speech, after which Harry is resurrected and defeats his enemy.[242]

Themes

Death is Rowling's overarching theme in Harry Potter.[243][244] In the first book, when Harry looks into the Mirror of Erised, he feels both joy and "a terrible sadness" at seeing his desire: his parents, alive and with him.[245] Confronting their loss is central to Harry's character arc and manifests in different ways through the series, such as in his struggles with Dementors.[245][246] Other characters in Harry's life die; he even faces his own death in Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows.[247] The series has an existential perspective – Harry must grow mature enough to accept death.[248] In Harry's world, death is not binary but mutable, a state that exists in degrees.[249] Unlike Voldemort, who evades death by separating and hiding his soul in seven parts, Harry's soul is whole, nourished by friendship and love.[248] Love distinguishes the two characters. Harry is a hero because he loves others, even willing to accept death to save them; Voldemort is a villain because he does not.[250]

While Harry Potter can be viewed as a story about good vs. evil, its moral divisions are not absolute.[251][252] First impressions of characters are often misleading. Harry assumes in the first book that Quirrell is good because he opposes Snape, who appears malicious; in reality, their positions are reversed. This pattern later recurs with Moody and Snape.[251] In Rowling's world, good and evil are choices rather than inherent attributes: second chances and redemption are key themes of the series.[253] This is reflected in Harry's self-doubts after learning his connections to Voldemort, such as Parseltongue;[254] and prominently in Snape's characterisation, which has been described as complex and multifaceted.[255] In some scholars' view, while Rowling's narrative appears on the surface to be about Harry, her focus may actually be on Snape's morality and character arc.[256][257]

Reception

Rowling has enjoyed enormous commercial success as an author. Her Harry Potter series topped bestseller lists,[258] spawned a global media franchise including films[61] and video games,[259] and was translated into at least 70 languages by 2018.[260] The first three Harry Potter books occupied the top three spots of The New York Times bestseller list for more than a year; they were then moved to a newly created children's list.[261] The final four books – Goblet of Fire,[262] Order of the Phoenix,[263] Half-Blood Prince, and Deathly Hallows[264] – each set records as the fastest-selling books in the UK or US. As of 2018[update], the series had sold more than 500 million copies according to Bloomsbury.[265] Neither of Rowling's later works, The Casual Vacancy and the Cormoran Strike series, have been as successful,[266] though Casual Vacancy was still a bestseller in the UK within weeks of its release.[267] Harry Potter's popularity has been attributed to factors including the nostalgia evoked by the boarding-school story, the endearing nature of Rowling's characters, and the accessibility of her books to a variety of readers.[268][269] According to Julia Eccleshare, the books are "neither too literary nor too popular, too difficult nor too easy, neither too young nor too old", and hence bridge traditional reading divides.[270]

Critical response to Harry Potter has been more mixed.[271] Harold Bloom regards Rowling's prose as poor and her plots as conventional,[272][273] while Jack Zipes argues that the series would not be successful if it were not formulaic.[274] Zipes states that the early novels have the same plot: in each book, Harry escapes the Dursleys to visit Hogwarts, where he confronts Lord Voldemort and then heads back successful.[275] Rowling's prose has been described as simple and not innovative; Le Guin, like several other critics, considers it "stylistically ordinary".[276] According to the novelist A. S. Byatt, the books reflect a dumbed-down culture dominated by soap operas and reality television.[277][226] Thus, some critics argue, Harry Potter does not innovate on established literary forms; nor does it challenge readers' preconceived ideas.[226][278] Conversely, scholar Philip Nel rejects such critiques as "snobbery" that reacts to the novels' popularity,[272] whereas Mary Pharr argues that Harry Potter's conventionalism is the point: by amalgamating literary forms familiar to her readers, Rowling invites them to "ponder their own ideas".[279] Other critics who see artistic merit in Rowling's writing include Marina Warner, who views Harry Potter as part of an "alternative geanology" of English literature that she traces from Edmund Spenser to Christina Rossetti,[271] and Michiko Kakutani, who praises Rowling's fictional world and the darker tone of the series' later entries.[280]

Reception of Rowling's later works has varied among critics. The Casual Vacancy, her attempt at literary fiction, drew mixed reviews. Some critics praised its characterisation, while others stated that it would have been better if it contained magic.[281] The Cormoran Strike series was more warmly received as a work of British detective fiction, even as some reviewers noted that its plots are occasionally contrived.[282] Theatrical reviews of Harry Potter and the Cursed Child were highly positive.[198][199] Fans have been more critical of the play's use of time travel, changes to characters' personalities, and perceived queerbaiting in Albus and Scorpius' relationship, leading some to question its connection to the Harry Potter canon.[283]

Gender and social division

Rowling's portrayal of women in Harry Potter has been described as complex and varied, but nonetheless conforming to stereotypical and patriarchal depictions of gender.[284] Gender divides are ostensibly absent in the books: Hogwarts is coeducational and women hold positions of power in wizarding society. However, this setting obscures the typecasting of female characters and the general depiction of conventional gender roles.[285] According to scholars Elizabeth Heilman and Trevor Donaldson, the subordination of female characters goes further early in the series. The final three books "showcase richer roles and more powerful females": for instance, the series' "most matriarchal character", Molly Weasley, engages substantially in the final battle of Deathly Hallows, while other women are shown as leaders.[286] Hermione Granger, in particular, becomes an active and independent character essential to the protagonists' battle against evil.[287] Yet, even particularly capable female characters such as Hermione and Minerva McGonagall are placed in supporting roles,[288] and Hermione's status as a feminist model is debated.[289] Girls and women are frequently shown as emotional, defined by their appearance, and denied agency in family settings.[290]

The social hierarchies in Rowling's magical world have been a matter of debate among scholars and critics.[291] The primary antagonists of Harry Potter, Voldemort and his followers, believe blood purity is paramount, and that non-wizards, or "muggles", are subhuman.[292] Their ideology of racial difference is depicted as unambiguously evil.[293] However, the series cannot wholly reject racial division, according to several scholars, as it still depicts wizards as fundamentally superior to muggles.[294] Blake and Zipes argue that numerous examples of wizardly superiority are depicted as "natural and comfortable".[295] Thus, according to Gupta, Harry Potter depicts superior races as having a moral obligation of tolerance and altruism towards lesser races, rather that explicitly depicting equality.[296]

Rowling's depictions of the status of magical non-humans is similarly debated.[297] Discussing the slavery of house-elves within Harry Potter, scholars such as Brycchan Carey have praised the books' abolitionist sentiments, viewing Hermione's Society for the Promotion of Elfish Welfare as a model for younger readers' political engagement.[298] Other critics, including Farah Mendlesohn, find the portrayal of house-elves extremely troublesome; they are written as happy in their slavery, and Hermione's efforts on their behalf, implied to be naïve.[299] Pharr terms the house-elves a disharmonious element in the series, writing that Rowling leaves their fate hanging;[300] at the end of Deathly Hallows, the elves remain enslaved and cheerful.[301] More generally, the subordination of magical non-humans remains in place, unchanged by the defeat of Voldemort.[302] Thus, scholars suggest, the series's message is essentially conservative; it sees no reason to transform social hierarchies, only being concerned with who holds positions of power.[303]

Religious reactions

There have been attempts to ban Harry Potter around the world, especially in the United States,[304][305] and in the Bible Belt in particular.[306] The series topped the American Library Association's list of most challenged books in the first three years of its publication.[307] In the following years, parents in several US cities launched protests against teaching it in schools.[308] Some Christian critics, particularly Evangelical Christians, have claimed that the novels promote witchcraft and harm children;[309][310] similar opposition has been expressed to the film adaptations.[311] Criticism has taken two main forms: allegations that Harry Potter is a pagan text; and claims that it encourages children to oppose authority, derived mainly from Harry's rejection of the Dursleys, his adoptive parents.[312] Author and scholar Amanda Cockrell suggests that Harry Potter's popularity, and recent preoccupation with fantasy and the occult among Christian fundamentalists, explains why the series received particular opposition.[305] Some groups of Shia and Sunni Muslims also argued that the series contained satanic subtext, and it was banned in private schools in the United Arab Emirates.[313]

The Harry Potter books also have a group of vocal religious supporters who believe that Harry Potter espouses Christian values, or that the Bible does not prohibit the forms of magic described in the series.[314] Christian analyses of the series have argued that it embraces ideals of friendship, loyalty, courage, love, and the temptation of power.[315][316] After the final volume was published, Rowling said she intentionally incorporated Christian themes, in particular the idea that love may hold power over death.[315] According to Farmer, it is a profound misreading to think that Harry Potter promotes witchcraft.[317] Scholar Em McAvan writes that evangelical objections to Harry Potter are superficial, based on the presence of magic in the books: they do not attempt to understand the moral messages in the series.[306]

Legacy

Rowling's Harry Potter series has been credited with a resurgence in crossover fiction: children's literature with an adult appeal.[318][m] Crossovers were prevalent in 19th-century American and British fiction, but fell out of favour in the 20th century[320] and did not occur at the same scale.[321] The post-Harry Potter crossover trend is associated with the fantasy genre.[322] In the 1970s, children's books were generally realistic as opposed to fantastic,[323] while adult fantasy became popular because of the influence of The Lord of the Rings.[324] The next decade saw an increasing interest in grim, realist themes, with an outflow of fantasy readers and writers to adult works.[325][326]

The commercial success of Harry Potter in 1997 reversed this trend.[327] The scale of its growth had no precedent in the children's market: within four years, it occupied 28% of that field by revenue.[328] Children's literature rose in cultural status,[329] and fantasy became a dominant genre.[322][330] Older works of children's fantasy, including Diana Wynne Jones's Chrestomanci series and Diane Duane's Young Wizards, were reprinted and rose in popularity; some authors re-established their careers.[331] In the following decades, many Harry Potter imitators and subversive responses grew popular.[332][333]

Rowling has been compared to Enid Blyton, who also wrote in simple language about groups of children and long held sway over the British children's market.[334][335] She has also been described as an heir to Roald Dahl.[336] Some critics view Harry Potter's rise, along with the concurrent success of Philip Pullman's His Dark Materials, as part of a broader shift in reading tastes: a rejection of literary fiction in favour of plot and adventure.[337] This is reflected in the BBC's 2003 "Big Read" survey of the UK's favourite books, where Pullman and Rowling ranked at numbers 3 and 5, respectively, with very few British literary classics in the top 10.[338]

Harry Potter's popularity led its publishers to plan elaborate releases and spawned a textual afterlife among fans and forgers. Beginning with the release of Prisoner of Azkaban on 8 July 1999 at 3:45 pm,[339] its publishers coordinated selling the books at the same time globally, introduced security protocols to prevent premature purchases, and required booksellers to agree not to sell copies before the appointed time.[340] Driven by the growth of internet access and use around its initial publication, fan fiction about the series proliferated and has spawned a diverse community of readers and writers.[341][342] While Rowling has supported fan fiction, her statements about characters – for instance, that Harry and Hermione could have been a couple, and that Dumbledore was gay – have complicated her relationship with readers.[343][344] According to scholars, this shows that modern readers feel a sense of ownership over the text that is independent of, and sometimes contradicts, authorial intent.[345][346]

Legal disputes

In the 1990s and 2000s, Rowling was both a plaintiff and defendant in lawsuits alleging copyright infringement. Nancy Stouffer sued Rowling in 1999, alleging that Harry Potter was based on stories she published in 1984.[347][348] Rowling won in September 2002.[349] Richard Posner describes Stouffer's suit as deeply flawed and notes that the court, finding she had used "forged and altered documents", assessed a $50,000 penalty against her.[350]

With her literary agents and Warner Bros., Rowling has brought legal action against publishers and writers of Harry Potter knockoffs in several countries.[351] In the mid-2000s, Rowling and her publishers obtained a series of injunctions prohibiting sales or published reviews of her books before their official release dates.[352][353]

Beginning in 2001, after Rowling sold film rights to Warner Bros., the studio tried to take Harry Potter fan sites offline unless it determined that they were made by "authentic" fans for innocuous purposes.[354] In 2007, with Warner Bros., Rowling started proceedings to cease publication of a book based on content from a fan site called The Harry Potter Lexicon.[347][355] The court held that Lexicon was neither a fair use of Rowling's material nor a derivative work, but it did not prevent the book from being published in a different form.[356] Lexicon was published in 2009.[357]

Philanthropy

With an awareness of the good fortune that led to her wealth and fame,[358] and wanting to use her public image to help others despite her concerns about publicity and the press, Rowling became, in the words of Smith, "emboldened ... to stand up and be counted on issues that were important to her".[359] As early as 2000, while she was still writing the Harry Potter series, Rowling established the Volant Charitable Trust, named after her mother.[360] Its mission is to "alleviate social deprivation, with a particular emphasis on supporting women, children and young people at risk".[361] Rowling and MEP Emma Nicholson[362] founded Lumos in 2005 (then the Children's High Level Group).[360] She was appointed president of the charity Gingerbread (originally One Parent Families) in 2004,[363] after becoming its first ambassador in 2000.[360] She also collaborated with Sarah Brown[364] in writing a book of children's stories to benefit One Parent Families.[360] Rowling's charitable donations before 2012 were estimated by Forbes at $160 million.[172] She was the second most generous UK donor in 2015 (following singer Elton John), giving about $14 million.[365]

Lumos has advocated for reform in orphanage care in Ukraine, working with an orphanage west of Kyiv.[366] After the February 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Rowling stated she will personally match up to £1 million in donations made toward an emergency appeal launched by Lumos.[367]

Rowling has made donations to support medical causes. She named another institution for her mother when, in 2010, she donated £10 million to found a multiple sclerosis research centre at the University of Edinburgh.[368] She gave an additional £15.3 million to the centre in 2019.[369] During the 2012 Summer Olympics opening ceremony, accompanied by an inflatable representation of Lord Voldemort,[370] she read from Peter Pan as part of a tribute to Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children.[371] To support COVID-19 relief, she donated six-figure sums to both Khalsa Aid and the British Asian Trust from royalties for The Ickabog.[207]

Several publications in the Harry Potter universe have been sold for charitable purposes. Profits from Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them and Quidditch Through the Ages, both published in 2001, went to Comic Relief.[360] To support Children's Voice, later renamed Lumos, Rowling sold a deluxe copy of The Tales of Beedle the Bard at auction in 2007. Amazon's £1.95 million purchase set a record for a contemporary literary work and for children's literature.[372][373] Rowling published the book and, in 2013, donated the proceeds of nearly £19 million (then about $30 million) to Lumos.[374][375] Rowling and 12 other writers composed short pieces in 2008 to be sold to benefit Dyslexia Action and English PEN. Rowling's contribution was an 800-word Harry Potter prequel.[376][n]

When the revelation that Rowling wrote The Cuckoo's Calling led to an increase in sales,[188] she donated the royalties to ABF The Soldiers' Charity (formerly the Army Benevolent Fund).[360][378]

Views

Politics

In 2008 Rowling donated £1 million to the Labour Party, endorsed Labour Prime Minister Gordon Brown over his Conservative challenger David Cameron, and commended Labour's policies on child poverty.[379] When asked about the 2008 United States presidential election, she stated that "it is a pity that Clinton and Obama have to be rivals because both are extraordinary."[87]

In her "Single mother's manifesto" published in The Times in 2010, Rowling criticised Prime Minister Cameron's plan to encourage married couples to stay together by offering them an annual tax credit. She thought that the proposal discriminated against single parents, whose interests the Conservative Party failed to consider.[380]

She opposed the 2014 Scottish independence referendum, due to concerns about the economic consequences, and donated £1 million to the Better Together anti-independence campaign,[381] and campaigned for the United Kingdom to stay in the European Union in the run-up to the 2016 United Kingdom European Union membership referendum. She defined herself as an internationalist, "the mongrel product of this European continent",[28] and expressed concern that "racists and bigots" were directing parts of the Leave campaign.[382]

She opposed Benjamin Netanyahu, and believed that depriving Israelis of shared culture would not dislodge him.[383] In 2015, Rowling joined 150 others in signing a letter published in The Guardian espousing cultural engagement with Israel.[384]

Press

Rowling has a difficult relationship with the press and has tried to influence the type of coverage she receives.[385] She described herself in 2003 as "too thin-skinned" with regard to the press.[386] As of 2011, she had taken more than 50 actions against the press.[387] Rowling dislikes the British tabloid the Daily Mail,[388] which she successfully sued in 2014 for libel about her time as a single mother.[389]

The Leveson Inquiry, an investigation of the British press, named Rowling as a "core participant" in 2011. She was one of many celebrities alleged to have been victims of phone hacking.[390] In 2012, she wrote an op-ed for The Guardian in response to Cameron's decision not to implement all the inquiry's recommendations.[391] She reaffirmed her stance on "Hacked Off", a campaign supporting the self-regulation of the press, by co-signing a 2014 declaration to "[safeguard] the press from political interference while also giving vital protection to the vulnerable" with other British celebrities.[392]

Transgender people

In December 2019, Rowling tweeted her support for Maya Forstater, a British woman who initially lost her employment tribunal case (Maya Forstater v Centre for Global Development) but won on appeal against her former employer, the Center for Global Development, after her contract was not renewed due to her comments about transgender people.[393][394][395] Rowling wrote on Twitter, "Dress however you please. Call yourself whatever you like. Sleep with any consenting adult who'll have you. Live your best life in peace and security. But force women out of their jobs for stating that sex is real?"[396]

On 6 June 2020, Rowling tweeted criticism of the phrase "people who menstruate",[397] and stated "If sex isn't real, the lived reality of women globally is erased. I know and love trans people, but erasing the concept of sex removes the ability of many to meaningfully discuss their lives."[398] Rowling's tweets were criticised by GLAAD, who called them "cruel" and "anti-trans".[399][400] Some members of the cast of the Harry Potter film series criticised Rowling's views or spoke out in support of trans rights, including Daniel Radcliffe, Emma Watson, Rupert Grint, Bonnie Wright, and Katie Leung, as did Fantastic Beasts lead actor Eddie Redmayne and the fansites MuggleNet and The Leaky Cauldron.[401][402][403] The actress Noma Dumezweni (who played Hermione Granger in Harry Potter and the Cursed Child) initially expressed support for Rowling but backtracked following criticism.[404]

On 10 June 2020, Rowling published a 3,600-word essay on her website in response to the criticism.[63][405] She again wrote that many women consider terms like "people who menstruate" to be demeaning. She said that she was a survivor of domestic abuse and sexual assault, and stated that "When you throw open the doors of bathrooms and changing rooms to any man who believes or feels he's a woman ... then you open the door to any and all men who wish to come inside", while stating that most trans people were vulnerable and deserved protection.[406] Rowling's essay was criticised by, among others, the children's charity Mermaids (which supports transgender and gender non-conforming children and their parents), Stonewall, GLAAD and the feminist gender theorist Judith Butler.[407][408][409][410][411][412] Rowling has been referred to as a trans-exclusionary radical feminist (TERF) on multiple occasions, though she rejects the label.[413] Rowling has received support from actors Robbie Coltrane[414] and Eddie Izzard,[415] and some feminists[416] such as activist Ayaan Hirsi Ali[417] and the radical feminist Julie Bindel.[416] The BBC nominated her essay for its annual Russell Prize for best writing.[418][419]

In August 2020, Rowling returned her Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights Ripple of Hope Award after Kerry Kennedy released a statement expressing her "profound disappointment" in Rowling's "attacks upon the transgender community", which Kennedy called "inconsistent with the fundamental beliefs and values of RFK Human Rights and ... a repudiation of my father's vision".[420][421][422] Rowling stated that she was "deeply saddened" by Kennedy's statement, but maintained that no award would encourage her to "forfeit the right to follow the dictates" of her conscience.[420]

Awards and honours

Rowling has won numerous accolades for the Harry Potter series for general literature, children's literature and speculative fiction. In 2000, Prisoner of Azkaban was nominated for the Whitbread Book of the Year where it competed against a book by a Nobel prize laureate. The award body gave it the children's prize instead (worth half the cash amount); some scholars view this as exposing a literary prejudice against children's books.[423][424] The series has won multiple British Book Awards, beginning with the Children's Book of the Year for Philosopher's Stone[425] and Chamber of Secrets,[426] followed by a shift to the more general Book of the Year for Half-Blood Prince.[427] It received speculative fiction awards such as the Hugo Award for Best Novel for Goblet of Fire.[428]

Rowling's early career awards include the Order of the British Empire (OBE) for services to children's literature in 2000,[429] and three years later, the Spanish Prince of Asturias Award for Concord.[430] She won the British Book Awards' Author of the Year and Outstanding Achievement prizes over the span of the Harry Potter series.[431][432] Following the publication of Deathly Hallows, Time named Rowling a runner-up for its 2007 Person of the Year, citing the social, moral, and political inspiration she gave her fans.[433] Two years later, she was recognised as a Chevalier de la Légion d'Honneur by French President Nicolas Sarkozy[434] and leading magazine editors named her the "Most Influential Woman in the UK".[435] Later awards include the Freedom of the City of London in 2012[436] and for her services to literature and philanthropy, the Order of the Companions of Honour (CH) in 2017.[437]

Academic bodies have bestowed multiple honours[28][438] on Rowling including honorary degrees from the University of Exeter (which she attended)[439] and Harvard University, where she spoke at the 2008 commencement ceremony.[440] The same year, Rowling won University College Dublin's James Joyce Award.[28] Her other honours include fellowship of the Royal Society of Literature (FRSL),[441] the Royal Society of Edinburgh (HonFRSE),[442] and the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh (FRCPE).[443]

Rowling's other works have also received recognition. The fifth volume of the Cormoran Strike series won the British Book Awards' Crime and Thriller category in 2021.[444] At the 2011 British Academy Film Awards, the Harry Potter film series was named an Outstanding British Contribution to Cinema; Rowling shared this honour with producer David Heyman and members of the cast and crew.[445] Harry Potter and the Cursed Child won a record-breaking number of Laurence Olivier Awards in 2017.[198][199]

Bibliography

| Target/ Type |

Series/ Description |

Title | Date | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young adult fiction |

Harry Potter series | 1. Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone | 1997-06-26 | [123][124] |

| 2. Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets | 1998-07-02 | [123][446] | ||

| 3. Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban | 1999-07-08 | [123][447] | ||

| 4. Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire | 2000-07-08 | [123][448] | ||

| 5. Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix | 2003-06-21 | [123][449] | ||

| 6. Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince | 2005-07-16 | [123][450] | ||

| 7. Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows | 2007-07-21 | [451][452] | ||

| Harry Potter- related books |

Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them (supplement to the Harry Potter series) | 2001-03-12 | [453] | |

| Quidditch Through the Ages (supplement to the Harry Potter series) | 2001-03-12 | [454] | ||

| Harry Potter prequel (short story published in What's Your Story Postcard Collection) | 2008-07-01 | [377][455] | ||

| The Tales of Beedle the Bard (supplement to the Harry Potter series) | 2008-12-04 | [456] | ||

| Harry Potter and the Cursed Child (story concept for play) | 2016-07-30 premier |

[457][458] | ||

| Short Stories from Hogwarts of Power, Politics and Pesky Poltergeists | 2016-09-06 | [459] | ||

| Short Stories from Hogwarts of Heroism, Hardship and Dangerous Hobbies | 2016-09-06 | [460] | ||

| Hogwarts: An Incomplete and Unreliable Guide | 2016-09-06 | [461] | ||

| Harry Potter- related original screenplays |

Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them | 2016-11-18 | [462] | |

| Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald | 2018-11-16 premier |

[463] | ||

| Fantastic Beasts: The Secrets of Dumbledore | 2022-04-15 planned premier |

[153] | ||

| Adult fiction |

The Casual Vacancy | 2012-09-27 | [464] | |

| Cormoran Strike series (as Robert Galbraith) |

1. The Cuckoo's Calling | 2013-04-18 | [465] | |

| 2. The Silkworm | 2014-06-19 | [189] | ||

| 3. Career of Evil | 2015-10-20 | [190] | ||

| 4. Lethal White | 2018-09-18 | [191] | ||

| 5. Troubled Blood | 2020-09-15 | [466] | ||

| Children's fiction |

The Ickabog | 2020-11-10 | [206] | |

| The Christmas Pig | 2021-10-12 | [209] | ||

| Non-fiction | Books | Very Good Lives: The Fringe Benefits of Failure and Importance of Imagination, illustrated by Joel Holland, Sphere. | 2015-04-14 | [467] |

| A Love Letter to Europe : an Outpouring of Love and Sadness from our Writers, Thinkers and Artists, Coronet (contributor). | 2019-10-31 | [468] | ||

| Articles | "The first it girl: J. K. Rowling reviews Decca: the Letters by Jessica Mitford". Sussman, Peter Y., editor. The Daily Telegraph. | 2006-11-26 | [31][469] | |

| "The fringe benefits of failure, and the importance of imagination". Harvard Magazine. | 2008-06-05 | [440] | ||

| "Gordon Brown – the 2009 Time 100". Time magazine. | 2009-04-30 | [470] | ||

| "The single mother's manifesto". The Times. | 2010-04-14 | [471] | ||

| "I feel duped and angry at David Cameron's reaction to Leveson". The Guardian. | 2012-11-30 | [391] | ||

| "Isn't it time we left orphanages to fairytales?" The Guardian. | 2014-12-17 | [472] | ||

| Book | Foreword/ Introduction |

Reynolds, Kim; Cooling, Wendy, project consultants. Families Just Like Us: The One Parent Families Good Book Guide. National Council for One Parent Families; Book Trust. | 2000 | [473][474] |

| McNeil, Gil; Brown, Sarah, editors. Magic. Bloomsbury. | 2002-06-03 | [475] | ||

| Brown, Gordon. "Ending child poverty" in Moving Britain Forward. Selected Speeches 1997–2006. Bloomsbury. | 2006-09-25 | [31][476] | ||

| Anelli, Melissa. Harry, A History. Pocket Books. | 2008-11-04 | [477] |

Filmography

| Year | Title | Credited as | Notes | Ref. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actress | Screenwriter | Producer | Executive producer | ||||

| 2003 | The Simpsons | Yes | Voice cameo in "The Regina Monologues" | [478] | |||

| 2010 | Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 1 | Yes | Film based on Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows | [479] | |||

| 2011 | Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 2 | Yes | |||||

| 2015 | The Casual Vacancy | Yes | Television miniseries based on The Casual Vacancy | [480] | |||

| 2016 | Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them | Yes | Yes | Film inspired by the Harry Potter supplementary book Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them | [481] | ||

| 2017–present | Strike | Yes | Television series based on Cormoran Strike novels | [482] | |||

| 2018 | Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald | Yes | Yes | Film inspired by Harry Potter supplementary book Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them | [483] | ||

Notes

- ^ Sources differ on the precise name of Rowling's place of birth. As of January 2022[update], Rowling's personal website said she was born at "Yate General Hospital near Bristol".[8] She has sometimes said she was born in Chipping Sodbury, which is near Yate.[9] Tison Pugh says she was born in Chipping Sodbury General Hospital.[10] The Scotsman lists Cottage Hospital in Chipping Sodbury.[11] Biographer Smith describes Chipping Sodbury as "Yate's elegant neighbor", and reproduces a birth certificate that says District Sodbury, but lists the hospital as Cottage Hospital, 240 Station Road, Yate.[12] According to Smith: "... the [BBC Television] documentary still erroneously claimed that Joanne was born in Chipping Sodbury. Yet despite the mistake, the good folk of Yate are pressing for some kind of plaque or feature in their town to record it as her place of birth."[13]

- ^ St Michael's Primary School headmaster, Alfred Dunn, has been suggested as the inspiration for the Harry Potter headmaster Albus Dumbledore;[23] biographer Smith writes that Rowling's father, and other figures in her education, provide more likely examples.[24]

- ^ Rowling denies that her young playmate Ian Potter represents Harry.[25]

- ^ Smith describes Tutshill as "staunchly middle class",[30] and Parker describes Church Cottage as a "handsome Gothic Revival cottage".[31] In 2020, it was reported that a company listing Rowling's husband, Neil Murray, as director had purchased Church Cottage and renovations were underway.[32]

- ^ Pugh writes that "Rowling reportedly modeled the strict pedagogical style of Severus Snape after Morgan's methods."[10]

- ^ Smith compares the place meals held in the Rowling household[53] and the descriptions of food in The Little White Horse[54] to the elaborate food prepared for Hogwarts pupils.

- ^ Rowling later described Harris as "getaway driver and foul weather friend"; his Anglia inspired a flying version that appeared in Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets as a symbol of escape and rescue.[65][66]

- ^ Pugh writes, "In a droll allusion to this ill-fated union, Professor Trelawney warns Lavender Brown, 'Incidentally, that thing you are dreading – it will happen on Friday the sixteenth of October'."[38]

- ^ Rowling says Jessica was named after Mitford and a boy would have been named Harry; according to Smith (2002), Arantes says Jessica was named after Jezebel from the Bible.[92]

- ^ The depression inspired the Dementors – soul-sucking creatures introduced in Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban.[105]

- ^ The Scottish Arts Council grant was after Rowling had a contract for publication of Philosopher's Stone but before it was actually published.[121]

- ^ Smith writes that the Rowling sisters "never attended Sunday school or services",[158] and Parker writes that the other Rowling family members were not regular churchgoers, but that "Rowling regularly attended services in the church next door".[31]

- ^ Whle noting the prevalent view that Harry Potter catalysed this change, the critic Rachel Falconer also credits socio-economic factors. In her view, Rowling's success is part of "a larger cultural change in contemporary Western society which accords greater weight and value to the signifier, the 'child', than in previous decades".[319]

- ^ The original Harry Potter prequel manuscript was stolen in 2017.[377]

References

- ^ Smith 2002, p. 241.

- ^ a b c d Kirk 2003, p. 76.

- ^ Kirk 2003, p. 12.

- ^ Smith 2002, p. 175.

- ^ a b c Smith 2002, pp. 271–273.

- ^ "Judge rules against JK Rowling in privacy case". The Guardian. 7 August 2007. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- ^ Smith 2002, pp. 1, 39, 224.

- ^ a b c "About". JK Rowling. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- ^ Kirk 2003, pp. 11–12.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Pugh 2020, p. 2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "The JK Rowling story". The Scotsman. 16 June 2003. Archived from the original on 23 June 2020. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- ^ Smith 2002, pp. 4–6.

- ^ Smith 2002, p. 271.

- ^ Kirk 2003, p. 10.

- ^ a b c Smith 2002, p. 2.

- ^ a b c "Biography". JK Rowling. Archived from the original on 26 December 2007. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- ^ Smith 2002, p. 4.

- ^ Smith 2002, p. 8.

- ^ Smith 2002, pp. 8, 23, 72.

- ^ a b Smith 2002, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Smith 2002, p. 79.

- ^ Smith 2002, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Kirk 2003, p. 28.

- ^ Smith 2002, pp. 19, 27–32, 51–52.

- ^ a b Smith 2002, pp. 22, 29, 109.

- ^ Smith 2002, pp. 9–10, 39.

- ^ Smith 2002, p. 10.

- ^ a b c d e Pugh 2020, p. 6.

- ^ Smith 2002, pp. 22, 25–27, 39.

- ^ Smith 2002, p. 25.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Parker, Ian (24 September 2012). "Mugglemarch: J.K. Rowling writes a realist novel for adults". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 30 July 2014. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- ^ "Harry Potter: JK Rowling secretly buys childhood home". BBC News. 14 April 2020. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- ^ Smith 2002, p. 27.

- ^ Smith 2002, p. 28.

- ^ Smith 2002, pp. 27–30.

- ^ Smith 2002, pp. 28–30.

- ^ Smith 2002, pp. 36–38.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Pugh 2020, p. 3.

- ^ Kirk 2003, p. 37.

- ^ Smith 2002, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Kirk 2003, p. 33. The years of British secondary school are equivalent to the United States grades of 6–12; Kirk compares them to the seven years of the books in the Harry Potter series.

- ^ Kirk 2003, p. 39.

- ^ Smith 2002, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Smith 2002, pp. 56–58.

- ^ Kirk 2003, p. 36.

- ^ a b Smith 2002, p. 54.

- ^ Smith 2002, p. 61.

- ^ Smith 2002, pp. 55–56.

- ^ Smith 2002, p. 62.

- ^ a b c d e f Fraser, Lindsay (9 November 2002). "Harry and me". The Scotsman. Archived from the original on 9 June 2021. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- ^ Smith 2002, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Smith 2002, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Smith 2002, p. 17.

- ^ Smith 2002, p. 45.

- ^ Smith 2002, p. 38.

- ^ Kirk 2003, p. 35.

- ^ a b c Kirk 2003, p. 40.

- ^ Smith 2002, pp. 71, 74.

- ^ Smith 2002, pp. 74–75.

- ^ Smith 2002, p. xii.

- ^ a b c Pugh 2020, p. 4.

- ^ Smith 2002, p. 72.

- ^ a b c "J.K. Rowling Writes about Her Reasons for Speaking out on Sex and Gender Issues". J.K. Rowling. 10 June 2020. Archived from the original on 10 June 2020. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- ^ Smith 2002, pp. 76–78.

- ^ Pugh 2020, p. 9.

- ^ Smith 2002, pp. 77–78.

- ^ Smith 2002, pp. 79–81.

- ^ Smith 2002, pp. 80–81.

- ^ Kirk 2003, p. 42.

- ^ Smith 2002, p. 90.

- ^ Kirk 2003, p. 44.

- ^ Kirk 2003, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Smith 2002, pp. 89–90.

- ^ Smith 2002, pp. 95–97.

- ^ Smith 2002, p. 97.

- ^ Smith 2002, pp. 104–5 says Clapham; Kirk 2003, p. 49 says Clapham but p. 67 says Clapham Junction. Rowling tweeted in 2020 that she first put pen to paper in Clapham Junction. Minelle, Bethany (22 May 2020). "JK Rowling reveals Harry Potter's true birthplace: Clapham Junction". Sky News. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- ^ Pugh 2020, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Kirk 2003, p. 51.

- ^ a b Kirk 2003, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Loer, Stephanie (18 October 1999). "All about Harry Potter from Quidditch to the future of the Sorting Hat". The Boston Globe. p. C7. ProQuest 405306485.

- ^ Smith 2002, p. 108.

- ^ Smith 2002, p. 106.

- ^ Smith 2002, pp. 109–110.

- ^ Greig, Geordie (10 January 2006). "'There would be so much to tell her...'". The Daily Telegraph. p. 25. ProQuest 321301864.

- ^ Smith 2002, pp. 109–112.

- ^ Smith 2002, p. 111.

- ^ a b c d Cruz 2008.

- ^ Smith 2002, pp. 114–116.

- ^ Smith 2002, pp. 121–122.

- ^ Smith 2002, p. 127.

- ^ Smith 2002, pp. 127–131.

- ^ Smith 2002, p. 132.

- ^ Kirk 2003, p. 70.

- ^ Kirk 2003, p. 57: "Soon, by many eyewitness accounts and even some versions of Jorge's own story, domestic violence became a painful reality in Jo's life.".

- ^ "JK Rowling: Sun newspaper criticised by abuse charities for article on ex-husband". BBC News. 12 June 2020. Archived from the original on 12 June 2020. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- ^ Smith 2002, pp. 133–134.

- ^ Smith 2002, pp. 136–137.

- ^ a b Smith 2002, p. 136.

- ^ Smith 2002, pp. 138–139.

- ^ a b Rowling, JK (June 2008). "JK Rowling: The fringe benefits of failure". TED. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 5 March 2011.

Failure & imagination

- ^ a b Smith 2002, p. 140.

- ^ Smith 2002, p. 141.

- ^ Smith 2002, p. 142.

- ^ a b Kirk 2003, p. 60.

- ^ Chaundy, Bob (18 February 2003). "Harry Potter's magician". BBC News. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- ^ Smith 2002, p. 144.

- ^ Smith 2002, p. 150.

- ^ Kirk 2003, pp. 55, 60.

- ^ Smith 2002, pp. 144–146.

- ^ Smith 2002, pp. 147–148.

- ^ Smith 2002, p. 149.

- ^ Smith 2002, p. 173.

- ^ Smith 2002, pp. 148–149.

- ^ Anelli 2008, p. 44.

- ^ Anelli 2008, pp. 41, 47.

- ^ Smith 2002, p. 152.

- ^ Anelli 2008, p. 43.

- ^ Kirk 2003, p. 75.

- ^ Lawless, John (3 July 2005). "Revealed: The eight-year-old girl who saved Harry Potter". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 6 October 2011.

- ^ Smith 2002, p. 162.

- ^ a b Smith 2002, p. 176.

- ^ Kirk 2003, pp. 62, 76, 119.

- ^ a b c d e f g "A Potter timeline for muggles". Toronto Star. 14 July 2007. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- ^ a b Errington 2017, p. 2.

- ^ a b c Smith 2002, pp. 187–188.

- ^ a b c Hahn 2015, pp. 264–266.

- ^ Mamary 2020, pp. 1–3.

- ^ Kirk 2003, p. 77.

- ^ Kirk 2003, p. 79.

- ^ Anelli 2008, pp. 50, 58–59.

- ^ "Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone". Kirkus Reviews. 1 September 1998. Archived from the original on 14 December 2013. Retrieved 14 December 2013.

- ^ Anelli 2008, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Anelli 2008, p. 63.

- ^ Whited 2002, p. 2.

- ^ Whited 2002, p. 5.

- ^ Kirkpatrick, David D. (23 June 2003). "New 'Harry Potter' book sells 5 million on first day". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 27 May 2015. Retrieved 31 January 2022.

- ^ Wyatt, Edward (18 July 2005). "Harry Potter book sets record in first day". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 29 May 2015. Retrieved 31 January 2022.

- ^ Rich, Motoko (23 July 2007). "Harry Potter's popularity holds up in early sales". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 5 March 2008. Retrieved 31 January 2022.

- ^ Gunelius 2008, pp. 8, 37.

- ^ a b Smith 2002, p. 210.

- ^ Anelli 2008, pp. 66–68.

- ^ Kirk 2003, p. 94.

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter (28 October 2021). "Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone review – 20 years on, it's a nostalgic spectacular". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- ^ Lyall, Sarah (12 November 2010). "A screenwriter's Hogwarts decade". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 16 November 2010. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- ^ Sragow, Michael (15 November 2001). "The wizard behind 'Harry'". The Baltimore Sun. p. 1E. ProQuest 406491574.

- ^ Barnes, Brooks (21 November 2010). "'Harry Potter' has $330 million debut weekend". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 22 November 2010. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- ^ Barnes, Brooks (17 July 2011). "Millions of Muggles propel Potter film at box office". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- ^ Cieply, Michael (12 September 2013). "Warner and J.K. Rowling Reach Wide-Ranging Deal". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 12 September 2013. Retrieved 31 January 2022.

- ^ "JK Rowling plans five Fantastic Beasts films". BBC News. 14 October 2016. Archived from the original on 24 November 2016.

- ^ Cain, Sian (25 November 2016). "The screenplay of Fantastic Beasts is a rare miss for the wizarding world". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- ^ Dargis, Manohla (8 November 2018). "'Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald' review: apocalypse too soon". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 9 November 2018. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- ^ a b Crouch, Aaron (22 September 2021). "'Fantastic Beasts: The Secrets of Dumbledore' sets new 2022 release date". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 22 September 2021. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- ^ Smith 2002, pp. 218–222.

- ^ Smith 2002, p. 222.

- ^ a b Nelson, Michael (31 January 2002). "Fantasia: The Gospel According to C.S. Lewis". The American Prospect. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- ^ Smith 2002, pp. 25–27, 76.

- ^ Smith 2002, p. 76.

- ^ Weeks, Linton (20 October 1999). "Charmed, I'm sure; the enchanting success story of Harry Potter's creator, J.K. Rowling". The Washington Post. p. C01. ProQuest 408532236.

- ^ Presenter: Mark Lawson (27 September 2012). "J. K. Rowling". Front Row. Event occurs at 17:45. BBC Radio 4. Archived from the original on 1 October 2012. Retrieved 27 September 2012.

- ^ a b Kirk 2003, p. 105.

- ^ Hale, Mike (16 July 2009). "The woman behind the boy wizard". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 15 July 2011. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- ^ Kirk 2003, p. 113.

- ^ Holmes 2015, p. 203.

- ^ "Adjudicated complaints: J K Rowling". Press Complaints Commission. Retrieved 1 February 2022.

- ^ Smith 2002, pp. 261–262, 266–267.

- ^ "Hogwarts hideaway for Potter author". The Scotsman. 22 November 2001. Archived from the original on 13 June 2020. Retrieved 25 October 2007.

- ^ "Baby joy for JK Rowling". BBC News. 24 March 2003. Archived from the original on 1 February 2009. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ "News: JKR gives birth to baby girl". JK Rowling. 25 January 2005. Archived from the original on 12 January 2012. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- ^ Watson, Julie; Kellner, Tomas (26 February 2004). "J.K. Rowling and the billion-dollar empire". Forbes. Archived from the original on 29 July 2017. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- ^ Couric, Katie (18 July 2005). "J.K. Rowling, the author with the magic touch". NBC News. Archived from the original on 28 November 2019. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- ^ a b "J.K. Rowling: billionaire to millionaire". The New Zealand Herald. 12 March 2012. Archived from the original on 25 July 2013. Retrieved 16 January 2013.

- ^ "Rowling 'makes £5 every second'". BBC News. 3 October 2008. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ "JK Rowling named world's highest-earning author by Forbes". BBC News. 4 August 2017. Archived from the original on 2 October 2017. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ^ "Worlds highest-paid authors 2019: J.K. Rowling back on top with $92 million". Forbes. 20 December 2019. Retrieved 20 December 2020.