Wallachian uprising of 1821

| Wallachian uprising | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Greek War of Independence | ||||||||

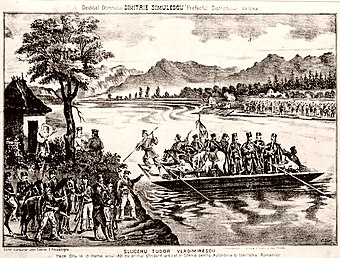

Pandurs crossing the Olt River at Slatina, on May 10, 1821; the four men standing at the front of the barge are, from the left: Dimitrie Macedonski, Tudor Vladimirescu, Mihai Cioranu, and Hadži-Prodan. Lithograph by Carol Isler | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Belligerents | ||||||||

|

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | ||||||||

|

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | ||||||||

| 4,000 to 24,000 | 7,000 to 20,000+ |

≈32,000 (10,000 to 14,000 in Wallachia) ≈1,800 Arnauts and allies 1,000 Zaporozhian Cossacks ≈40 ships | ||||||

The uprising of 1821 was a social and political rebellion in Wallachia, which was at the time a tributary state of the Ottoman Empire. It originated as a movement against the Phanariote administration, with backing from the more conservative boyars, but mutated into an attempted removal of the boyar class. Though not directed against Ottoman rule, the revolt espoused an early version of Romanian nationalism, and is described by historians as the first major event of a national awakening. The revolutionary force was centered on a group of Pandur irregulars, whose leader was Tudor Vladimirescu. Its nucleus was the Wallachian subregion of Oltenia, where Vladimirescu established his "Assembly of the People" in February.

From the beginning, Pandurs were joined by groups of Arnauts and by veterans of the Serbian Revolution. Although infused with anti-Hellenism, they collaborated with, and were infiltrated by, agents of the Filiki Eteria. Vladimirescu also cooperated with the Sacred Band of Alexander Ypsilantis, thereby contributing to the larger war of Greek independence. In conjunction with Ypsilantis' troops coming in from Moldavia, Vladimirescu managed to occupy Bucharest in March. Vladimirescu agreed to split the country with Ypsilantis, preserving control over Oltenia, Bucharest, and the southern half of Muntenia. The Pandurs' relationship with the Sacred Band degenerated rapidly, upon revelations that the Russian Empire had not validated Ypsilantis' expedition, and also over Vladimirescu's attempts to quell Eterist violence. Many of the Arnauts openly or covertly supported Ypsilantis, while others endorsed an independent warlord, Sava Fochianos.

Vladimirescu secretly negotiated an entente with the Ottomans, who ultimately invaded Wallachia in late April. The Pandurs withdrew toward Oltenia, which put them at odds with the Sacred Band. Vladimirescu's brutality alienated his own troops; in turn, this rift allowed the Greek revolutionaries to arrest and execute Vladimirescu, unopposed. The Oltenians scattered, though some Pandurs formed pockets of resistance, led by captains such as Dimitrie Macedonski and Ioan Solomon. They suffered clear defeat in their confrontation with the Ottoman Army. In June, Ypsilantis' force and its remaining Pandur allies were routed at Drăgășani. The uprising sparked a cycle of repressive terror, with a final episode in August, when Fochianos and his Arnauts were massacred in Bucharest.

The uprising of 1821 is widely seen as a failed or incomplete social revolution, with more far-reaching political and cultural implications. The Ottoman government registered its anti-Phanariote message, appointing an assimilated boyar, Grigore IV Ghica, as Prince of Wallachia. The ascent of nationalist boyars was enhanced during the Russian occupation of 1828, and cemented by a new constitutional arrangement, Regulamentul Organic. During this interval, survivors of the uprising split between those who supported this conservative establishment and those who favored liberal causes. The latter also helped preserve a heroic image of Vladimirescu, which was later also borrowed by agrarianists and left-wing activists.

Origins

Phanariote crisis

From the beginning of the 18th-century, Wallachia and Moldavia (the Danubian Principalities) had been placed by the Sublime Porte under a regime of indirect rule through Phanariotes. This cluster of Greek and Hellenized families, and the associated Greek diaspora, were conspicuously present at all levels of government. At a more generalized level, the Phanariote era emphasized tensions between the boyars, Phanariote or not, and the peasant class. Though released from serfdom, Wallachian peasants were still required to provide for the boyars in corvées and tithes. Over the early 19th century, the rural economy was often paralyzed by peasant strikes, tax resistance, sabotage, or litigation.[1] Additional pressures were created by Ottoman demands for the haraç and other fiscal duties, which the Phanariotes fulfilled through tax farming. "Excessive fiscal policies, dictated by both the Ottoman demands and the short span of reigns" meant that Phanariotes treated the principalities as "an actual tenancy."[2] The national budget for 1819 was 5.9 million thaler, of which at least 2 million were taken by the Sublime Porte, 1.3 million went to the ruling family, and 2.4 supplied the bureaucracy.[3] Although not at their highest historical level, Ottoman pressures had been steadily increasing since ca. 1800.[4]

Tax payers were additionally constrained by those boyars who obtained tax privileges or exemptions for themselves and their families. In 1819, from 194,000 families subject to taxation, 76,000 had been wholly or partly exempted.[5] Tax farmers, in particular the Ispravnici, acted in an increasingly predatory manner, and, in various cases, tortured peasants into paying more than their share.[6] In the 1800s, a reformist Prince Constantine Ypsilantis sided with the peasants, cracking down on abuse and even threatening capital punishment; this episode failed to address the causes, and abuses continued to be recorded into the 1810s.[7] Under constant fiscal pressure, many villagers resorted to selling their labor to boyars or to peasant entrepreneurs. According to a report by the Ispravnic of Gorj County, in 1819 migrant farmhands could barely cover their tax debt.[8]

Under the Phanariote regime, the country had dissolved her levy army—though a core force had briefly reemerged under Nicholas Mavrogenes, who led a Wallachian peasant force into the Austro-Turkish War of 1788.[9] Especially visible in Oltenia, the Pandurs traced their origins to the late 17th century, and had also functioned as a militia in 1718–1739, when Oltenia, or "Banat of Craiova", was a Habsburg territory. At times, they had been self-sustaining, with a lifestyle that bordered on hajduk brigandage.[10] The Phanariotes' hold on the country was put into question by turmoil during the Napoleonic era, which resulted in some additional rearmament. In 1802, the threat of an invasion by Ottoman secessionist Osman Pazvantoğlu pushed Bucharest into a panic. At its height, the mercenary Sava Fochianos and his Arnauts denounced their contract and left the city defenseless.[11] This embarrassment prompted Ypsilantis to form a small national contingent, comprising armed burghers and Pandurs who were trained by Western standards.[12]

Although approved by the Ottomans, this new militia was secretly also a component of Ypsilantis' plan to shake off Ottoman suzerainty with help from the Russian Empire. By August 1806, his alliance with Russia had been exposed, and he was forced to leave into exile.[13] The incident also sparked a six-year-long Russo-Turkish War. During this period, the Wallachian Pandurs, including a young Tudor Vladimirescu, acted as a unit of the Imperial Russian Army.[14] Under Russian occupation, the Greek–Wallachian rebel Nicolae Pangal issued several manifestos which, as noted by historian Emil Vârtosu, resembled later appeals by Vladimirescu.[15]

Hostilities were eventually suspended by the Treaty of Bucharest, hurried by Russia's need to defend herself against the French;[16] Ottoman rule in Wallachia and Moldavia was again consolidated with Russia focused on winning a war in Central Europe. The new Phanariote Prince was John Caradja, whose reign saw an upsurge in tax resistance and hajduk gang activity. In Bucharest, the epidemic known as Caragea's plague was an opportunity for marauding gangs of outlaws, who confused the authorities by dressing up as undertakers.[17] Rebellious activity peaked in Oltenia, where hajduks were organized by Iancu Jianu, a boyar's son, who frustrated all of Caradja's attempts at restoring order.[18] However, the Pandurs were divided. In 1814, some joined a raid by pirates from Ada Kaleh, storming through Mehedinți County and Gorj, though they later sought forgiveness from Vladimirescu.[19] The latter had sided with the Caradja regime, but still intervened on their behalf.[20]

Preparation

As a result of 1814 riots, tax privileges for the Pandurs were suspended, and they were demoted to the position of a militia assisting the Ispravnici.[21] In 1818, Caradja abandoned his throne and fled Wallachia, leaving Sultan Mahmud II to appoint an elderly loyalist, Alexandros Soutzos. His decision also specified that only four Phanariote families would be eligible for the crowns of either Wallachia and Moldavia: Callimachi, Mourouzis, and two lines of the Soutzos.[22] Upon entering Bucharest, the new Prince inaugurated a regime of institutional abuse. In April 1819, the attempt to put pressure on the peasantry sparked a riot at Islaz.[23] In one especially controversial writ of 1820, Soutzos ruled that the city of Târgoviște was not mortmain, and proclaimed it his family's property. This edict resulted sparked a burgher revolt, during which cadastre officials were attacked and chased out of Târgoviște.[24] Though he still favored the Arnauts,[25] Soutzos revised anti-Pandur persecution, restoring their role in the army and placing them under the command of a Romanian, Ioan Solomon.[26] His tensions with the Arnauts resulted in a standoff with the mercenaries, who barricaded themselves inside Sinaia Monastery.[27] However, Pandur Mihai Cioranu contends, Wallachia "swarmed with Greeks as never before", with every military commission set aside to serve "the Prince and his Greeks".[28]

Soutzos' other conflict was with the lesser Phanariotes, who were now won over by Greek nationalism. In 1820, Alexander Ypsilantis, son of Prince Constantine, united the various branches of the Filiki Eteria, a Greek revolutionary organization, and began preparing a massive anti-Ottoman revolt from the Russian port city of Odessa. This society had already managed to enlist in its ranks some preeminent Wallachian boyars: allegedly, its first recruits included Alecu Filipescu-Vulpea, joined later by Grigore Brâncoveanu.[29] According to one account, the Eterists also invited Soutzos to join the conspiracy, but he refused.[30] He died suddenly on January 19, 1821, prompting speculation that he had been poisoned by Ypsilantis' partisans.[31]

In Wallachia, Ypsilantis' cause had significant allies: the country's three main regents (or Caimacami)—Brâncoveanu, Grigore Ghica, Barbu Văcărescu—were all secretly members of the Eteria.[32] They contacted Vladimirescu with a mission to revive the national army and align it with Ypsilantis' movement.[33] However, other records suggest that Vladimirescu acted independently of the regents. He was located in Bucharest in November 1820, and was in direct contact with the Eterist leadership through various channels. Within two months, he had reportedly sealed a pact with two of Ypsilantis' agents, Giorgakis Olympios and Yiannis Pharmakis, who were also officers in Soutzos' Arnaut guard, and had borrowed 20,000 thaler from another Eterist, Pavel Macedonski, "to provide for the coming revolt."[34] Nevertheless, according to historian Vasile Maciu, the convention between Vladimirescu and his Eterist colleagues survives only in an unreliable translation, which may be entirely fabricated.[35] The Russian Consul in Wallachia, Alexander Pini, is viewed as a neutral player by scholar Barbara Jelavich,[36] but he too may have been involved on the Eterist side. This was attested by Pini's Moldavian secretary, Ștefan Scarlat Dăscălescu, who attributes the revolt initiative to "the leaders of the Greek revolution and Mr. Pini",[37] and dismisses Vladimirescu as a "Russian creature".[38] However, a letter from Tudor to Pini refutes any conscious cooperation between the two men.[39]

According to information gathered by the Russian spy Ivan Liprandi, Vladimirescu was also promised full adherence by the leading 77 boyars of the country, their pledge eventually issued as a formal writ and presented on their behalf by Dinicu Golescu.[40] Vladimirescu may have used this binding document as a collateral, allowing him to borrow 40,000 more thaler from Matija Nenadović.[41] Liprandi also notes that the Pandur leader was already in contact with Ilarion Gheorghiadis, the Bishop of Argeș, who helped him define his international diplomacy.[42] In the days before Soutzos' death, Vladimirescu had been spotted at Pitești, moving into Oltenia with some 40 Arnauts.[43] He traveled under an innocuous pretext, claiming to be heading for his Gugiu estate in Gorj County, to settle a land dispute.[44]

Revolutionary ideology

National and social ideas

While various researchers agree that Vladimirescu and his Pandurs were motivated by a nationalist ideology, its outline and implications remain debated among scholars. Social historians Ioan C. Filitti and Vlad Georgescu both argue that as a nationalist, Vladimirescu had short-term and long-term agendas: demands of recognition from the Porte, and for the restoration of ancient liberties, were only instrumental to a larger goal, which was national liberation with Russian assistance.[45] Nicolae Iorga views the Pandur leader as taking "one step forward" in the development of nationalist discourse, by introducing references to the general will.[46] Nicolae Liu also notes that the "pragmatic" rebel "made no reference to natural rights, but tacitly included them as the basis of his revolutionary program"; this notion was an import from Revolutionary France, along with the Pandurs' concept of the people-in-arms.[47] Sociolinguist Klaus Bochmann identifies the 1821 documents, including those issued "in the entourage of Tudor Vladimirescu" and those of his adversaries, as the first Romanian-language references to "patriotism"—and possibly as the first-ever records of a "political debate being carried out (mainly) in Romanian."[48] He underscores the ideological influence of Josephinism, noting that it came to Vladimirescu through his contacts with educator Gheorghe Lazăr;[49] other reports suggest that Vladimirescu was informed about the ideology of the Transylvanian School, having read Petru Maior.[50]

During the actual events of the uprising, Western sources began drawing parallels between Vladimirescu and historical peasant rebels, in particular Wat Tyler and Horea.[51] Various authors propose that Vladimirescu and his men were not only nationalists, but also had a core interest in social revolution, seeing it as their mission to supplant or control boyardom. Thus, historian Gheorghe Potra describes Tudor's rising as primarily "anti-feudal", with a "national character" in that it also aimed to shake off "the Turkish yoke".[52] As summarized by historian Neagu Djuvara, the Pandur revolt was originally "set out against all the nation's plunderers", but then "became a peasants' revolt which did not separate 'good' and 'bad' boyars, locals from foreigners. Nevertheless, in order to reach his goal, Tudor had no choice but to reach an agreement with the 'nationalist' boyars [...] as well as with Turkish power, [and] he resorted, at a later stage, to making his revolution into a fundamentally anti-Phanariote one."[53] Another ideological difference was that between Vladimirescu's Russophilia, a minority opinion, and the mounting Russophobia of both upper- and middle-class nationalists.[54]

Iorga proposes that Vladimirescu tried his best to establish a "democratic companionship" of Wallachians, hoping to draw a wedge between Romanian and Greek boyars.[55] Among the left-wing scholars, Andrei Oțetea argues that Vladimirescu slowly abandoned the peasant cause and fell into a "complete and humiliating subordination to the boyars."[56] The rebels' anti-boyar discourse was mitigated by other factors. One was the issue of their leader's own social standing: though originating from a clan of Oltenian peasants, Vladimirescu had been accepted into the third-class boyardom, with the rank of Sluger.[57] Cultural historian Răzvan Theodorescu argues that he, the rebel leader, actually belonged to a "rural bourgeoisie" which kept genealogies and had an "unexpected" taste for heraldry.[58] Other scholars also make note of Vladimirescu's elitist tastes and habits, his refusal to sanction retribution against the boyars, and his crushing of peasant radicalism during his seizure in power.[59] It is also probable that Vladimirescu intended to have himself recognized as Prince, as evidenced by his wearing a white kalpak, traditionally reserved for royalty.[60] His subordinates often referred to him as Domnul Tudor, which also indicated monarchic ambitions (see Domnitor).[61] The Italian press of his day viewed him as Wallachia's Duce.[62]

Pro- and anti-Greek

Another fluctuating trait of Vladimirescu's revolt was his attitude toward Greek nationalism. According to Iorga, Phanariote rule meant a "system of indissoluble elements", centered on Hellenism and Hellenization.[63] Maciu further notes that Phanariote rulers had stunted Romanian nationalism and national awakening by popularizing an Eastern Orthodox identity, common to Romanians and Greeks; this established a pattern of cooperation, pushing nationalists of various ethnicities into contact with each other.[64] Overall, Vârtosu argues, the rebellion was not xenophobic, but protectionist: Vladimirescu favored the "uplift of the native people", but also addressed his to proclamation to a larger "human kin". His white-and-blue banner had both familiar symbols of Christian tradition, which "drenched [the message] in the theological coloring of religious faith", and verse which described the "Romanian Nation".[65] In a Balkans context, Vladimirescu felt most sympathy toward the Serbian Revolution, having had direct contacts with Karađorđe,[66] and The Public Ledger even speculated that he was himself a Serb.[67] Affiliates of the Pandur revolt also included Naum Veqilharxhi, who published what may be the first manifesto of Albanian nationalism.[68]

In this setting, however, Vladimirescu "had no particular reason to hold the Phanariote [Ypsilantis] dear",[69] and the ideals of Orthodox universalism, "subordinating [Romanian] aspirations", were viewed with generalized suspicion.[70] As historians note, Vladimirescu "would have liked to rid the country of both the Greeks and the Turks",[71] viewing the former with "strong aversion", as the "agents of Turkish oppression in his country."[72] Ottomanist Kemal Karpat suggests that: "[In] Turkish sources [...] Vladimirescu's revolt is interpreted as a local uprising aimed chiefly at the protection of the local population against Greek exploitation"; a "long accepted version was that Vladimirescu rebelled against the Greeks without even being aware that [Ypsilantis], the Greek revolutionary, had risen against the Sultan in Russia."[73] In contrast, Dăscălescu proposes that the rebellion was originally anti-Turkish and pro-Greek, but that Vladimirescu had no way of winning over Oltenians with that message.[74] Moreover, Oțetea writes that the Pandur movement cannot be separated from the Eteria, who gave it "a chief, a program, a structure, the original impulse, tactics for propaganda and combat, [and] the first means of achieving its goals".[75] Oțetea also claims that Vladimirescu was indirectly influenced by the political vision of Rigas Feraios, though this verdict remains disputed.[76]

From the Eterist perspective, sending Vladimirescu to Oltenia was a cover-up for the Greek insurrection—a ruse that had been conceived by Olympios and merely approved by "Tudor Vladimirescu, his friend".[77] Seen by some commentators, and probably by Ypsilantis himself, as an actual member of the Eteria,[78] Vladimirescu endorsed the conspiracy in the belief that it had Russian support. However, in early 1821 the Congress of Laibach condemned the Greek revolution, imposing on Emperor Alexander I that he withdraw all endorsement for Ypsilantis' movement.[79] Ypsilantis prolonged his other alliance, with Vladimirescu, only by playing upon words, not revealing to him that Russia's support remained uncertain.[80]

Vladimirescu's campaign

Onset

Vladimirescu made his first Oltenian stop at Ocnele Mari, then moved in on the Gorj capital, Târgu Jiu, where he stayed at the house of a tax farmer, Vasile Moangă (or Mongescu).[81] His first action as a rebel was to arrest or take hostage the local Ispavnic, Dinicu Otetelișanu, on January 21.[82] On January 22, he and his Arnaut guard captured Tismana Monastery, turning it into a rallying point and prison.[83] A day later, at Padeș, Vladimirescu issued a proclamation mixing social and patriotic slogans. It marked his ideological dissidence, proclaiming the right of peasants to "meet evil with evil".[84] Written in a "vigorously biblical style",[85] it called into existence an "Assembly of the People", which was to "hit the snake on the head with a cane", ensuring that "good things come about".[86] In a parallel letter to the Sultan, Vladimirescu also insisted that his was an anti-boyar, rather than anti-Ottoman, uprising.[87] The response was positive on the Ottoman side.[88]

Instead of preparing his submission to Ypsilantis, he then began his march on Mehedinți County, passing through Broșteni, Cerneți, and Strehaia.[89] By January 29, boyars and merchants evacuated Mehedinți; this movement was mirrored by a similar exodus from Craiova, the Oltenian capital.[90] Boyars who stayed behind surrendered to Vladimirescu and took an oath of allegiance, becoming known to the Pandurs as făgăduiți ("pledged ones"). Members of this category, though they enjoyed Vladimirescu's personal protection,[91] signed secret letters of protest to the Sultan, calling for his intervention against the "brigands".[92] In February, after Vladimirescu had conquered the town of Motru, boyars still present in Craiova petitioned the Ottomans and Russians for help. Consul Pini approved their request to use force against Vladimirescu, but refused to commit Russian troops for that purpose.[93]

Reassured by Pini, the regents began amassing an Arnaut resistance to the rebellion, with individual units led by Dumitrachi Bibescu, Serdar Diamandi Djuvara, Deli-bașa Mihali, Pharmakis, Hadži-Prodan, and Ioan Solomon. Though there were violent clashes between the two sides at Motru, many of the loyalist troops voluntarily surrendered to the Pandurs, after parleying with Pandur agent Dimitrie Macedonski.[94] Faced with such insuburdionation, Caimacam Brâncoveanu reportedly maintained his calm and demanded to know Vladimirescu's grievances. Through his Macedonski associates, the rebel leader asked for a unification of boyar parties around his revolutionary goal, which included solving the peasant issue, and ordered them to disband the Arnaut corps.[95] Meanwhile, the peasantry responded to the proclamation of Padeș by organizing into a string a small uprisings. Some happened in Pandur strongholds, as during Dumitru Gârbea's raid on Baia de Aramă, while others took root in more distant villages, such as Bârca and Radovanu.[96] A Captain Ivanciu took control of Pitești and raided the surrounding villages.[97] In other areas, there were highway robberies organized by Romanian peasants or slaves of Romani origin. Such incidents happened in Slănic, Urziceni, or at Nucet Monastery.[98]

On February 4, the Pandurs were again camped in Gorj, at Țânțăreni. Here, Vladimirescu's army grew massively, to about 4,000 infantrymen and 500 horsemen.[99] The Macedonskis recount that he was awaiting for the boyars to follow his orders and unite under his command, but that this demand was in fact unrealistic.[100] While waiting in Țânțăreni, Vladimirescu provided his response to the Boyar Divan, whose leadership had asked not to engage in activity "harmful for the country". Vladimirescu presented himself as a "caretaker" of the state—one elected by the people to review the "awful tyranny" of boyars, but without toppling the regime.[92] A boyars' delegation, led by Vornic Nicolae Văcărescu, traveled to Vladimirescu's camp on February 11. It asked of the Pandurs that they refrain from marching on Bucharest, and appealed to their patriotic sentiments. To this, Vladimirescu replied that his conception of the motherland was fundamentally different: "the people, and not the Coterie of plunderers" (or "robber class").[101] Though he thus restated his generic dislike for the boyars, Vladimirescu also reassured Văcărescu that he did not "wish any harm to this Coterie", and "even more so I want to complete and strengthen its privileges."[102]

Army creation

Văcărescu was immediately replaced with Constantin Samurcaș, who was an Eterist agent, and favored bribing the Pandurs into submission. He offered Vladimirescu a pardon and a large tribute collected from the citizens of Craiova,[103] allegedly sending Hadži-Prodan to Țânțăreni, with 90,000 thaler as a gift.[92] According to at least one account, Samurcaș also prepared Arnaut troops, under Solomon and Djuvara, for a surprise attack on Vladimirescu's quarters.[104] Prodan himself recounted that had secret orders to kill Vladimirescu, but disobeyed and defected to the Pandur side.[105] Contrarily, anti-Greek authors view Prodan as a double agent of the Eteria, infiltrated alongside Dimitrie Macedonski.[106] In recounting this episode, Liprandi claims that Vladimirescu turned tables and unexpectedly handed Samurcaș a list of boyars and notabilities that he wanted executed. Names reportedly included Dionisie Lupu, Metropolitan of Wallachia.[107] Meanwhile, Caimacam Văcărescu wrote to promise Vladimirescu 250,000 thaler as additional aid, but, according to Liprandi, also demanded that the Pandurs arrest and kill Samurcaș, the "enemy of [our] cause".[107]

The Pandurs had been joined by packs of Oltenian hajduks, including the already famous Iancu Jianu, and by a small selection of young boyars, including Ioan Urdăreanu[108] and a group of scribes: Petrache Poenaru, Ioniță Dârzeanu, and Dumitrache Protopopescu.[109] It remains uncertain whether Gheorghe Magheru, a scion of the boyar clan in Albeni, was also a volunteer Pandur in 1821.[110] Vladimirescu still persecuted exponents of the old regime, having tax farmer Pau Nicolicescu put to death at Strehaia.[111] Nevertheless, he allowed other known exploiters, including Ghiță Cuțui, to join his rebel army.[96] It is statistically probable that more than half of his army captaincies were held by third-class boyars.[112]

The native Oltenian core was supplemented by Romanian peasants migrating from the Principality of Transylvania, which was part of the Austrian Empire;[112] and from the Silistra Eyalet (Ottoman Dobruja).[113] There were also massive arrivals of other Balkan ethnicities. The cavalry in particular was staffed by foreign volunteers, mainly Arnauts and Serbs.[114] The command core had Greek, Serb, Aromanian and Bulgarian officers, whose primary loyalty was to the Eteria. They included Olympios, Pharmakis, Prodan, Serdar Djuvara, and Macedonski.[115] The anonymous chronicle Istoria jăfuitorilor additionally notes that Vladimirescu's core units were staffed with veterans of Karađorđe's armies, including Pharmakis, Mihali, and Tudor Ghencea; others who had served with Ali Pasha of Ioannina.[116] European journals also recorded the recruitment of Greeks from Germany, and the presence of former officers from the Grande Armée.[117]

Tensions between these figures and their Oltenian commander were visible in February, when Vladimirescu put a stop to Prodan and Macedonski's sacking of the Otetelișanu manor in Benești.[118] According to Liprandi, Olympios was always a liability in Vladimirescu's camp, manipulating both him and Ypsilantis for material gain.[119] Olympios also tested Vladimirescu by rescuing and protecting a renegade Pandur, Grigore Cârjaliul, and by murdering some of the prisoners held at Tismana.[120] Pharmakis, who commanded over his own cohort of "400 Albanians", also acted independently, shielding from persecutions the boyars Lăcusteanu.[121] For his part, Vladimirescu protected Dinicu Golescu and his family, ordering his troops to release Iordache. The latter was then given a Pandur guard which escorted him to Transylvania.[122]

On February 23, Bucharest went through another regime change. Brâncoveanu secretly left Bucharest and crossed into Transylvania, settling in the border city of Corona (Brașov). His departure created another panic, stoked by the Arnauts. Olympios and Pharmakis returned to the capital and took control of its garrison, also raiding Târgoviște, Găești, and Băicoi.[123] The Sultan selected a new Prince, Scarlat Callimachi, who refused to abandon Ottoman safety for his throne. Instead, Callimachi appointed a new triumvirate of Caimacami, presided upon by Stefan Bogoridi.[124] This interval also marked the return to Bucharest of Sava Fochianos, whom Callimachi had created a Binbashi of his own Arnaut garrison.[125]

In parallel, the Eterist uprising began with a revolt of the Moldavian military forces in Galați and a pogrom of the local Turks, both staged by Vasileios Karavias.[126] Organized militarily as a "Sacred Band", the Eterists occupied Moldavia in the last week of February, and issued manifestos calling on all Ottoman Christians to join them.[127] A military government was created in Iași, under a General Pendidekas.[128] This was the starting point of an exodus of locals from the country, with some pockets of anti-Eterist resistance. Overall, Moldavian boyars were shocked by Karavias' violence;[129] the native population at large was anti-Greek by virtue of being anti-Phanariote, and only a few thousand Moldavians ever joined the Sacred Band.[130]

Taking Bucharest

In Wallachia, the combined Pandur–Arnaut force also began moving on Bucharest, taking Slătioara on March 4. Callimachi's regency also sought to coax Vladimirescu into submission, but he ignored the offer, and, instigated by the Macedonskis, prepared a Pandur conquest of Wallachia.[100] He then addressed the Caimacami a five-point ultimatum, which called for the removal of Phanariotes, the reestablishment of a levy army, tax relief, as well as 500,000 thaler for Vladimirescu's expenses.[131] A document formulated as Cererile norodului românesc ("Demands of the Romanian People") also specified a racial quota in assigning boyar offices and titles, and more generically a meritocracy. The main tax was kept, but reduced and divided into quarterly installments.[132]

Numerical estimates of Vladimirescu's force vary significantly. Some authors count 8,000 soldiers (6,000 Oltenian infantrymen, 2,000 Balkan cavalry),[133] while others advance the number to 10,000,[41] 14,000,[134] or 24,000.[135] According to Cioranu, in all Vladimirescu's army comprised 20,000 men: of his 12,000 Pandurs, 6,000 had been left at forts in Oltenia, including troops under Serdar Djuvara, Solomon, and Moangă; 8,000 Arnauts "of various races", mostly Serbs from Karađorđe's army, of whom only 2,500 were available for combat.[136] Vladimirescu himself claimed to have at least 12,000 men under arms, while conservative estimates lower that number to 4,000 or 5,000.[137] These troops were also backed by a cell of artillery personnel. According to various counts, they had five to eight cannons, of which two were smaller in size.[138]

The Pandurs' march came with a recruitment drive. For instance, Solomon's auxiliary force held Craiova, where they began signing up burghers.[139] Pitești, which had strategic importance, was secured on March 7, and placed under Captain Simion Mehedințeanu. Pandur recruitment largely failed here, but the townsfolk pledged their material support.[140] The hostile narrator of Istoria jăfuitorilor also claims that Vladimirescu was expected in Bucharest by a fifth column, comprising "vagabonds, foreigners, Serbian, Arnaut or Bulgarian thieves, and all those Bucharest panhandlers that we mockingly call crai [kings]".[141] The breakdown of Phanariote power accelerated crossovers by the Arnauts, who were no longer receiving salaries from the treasury.[142] Vladimirescu himself separated between loyal and disloyal Arnauts. At Slatina, he had established a 40-men Serb "killing guard", possibly led by Chiriac Popescu. Its first mission was to assassinate Arnaut leaders who had engaged in looting.[143]

On March 10, the rebels crossed the Olt River, marched through Șerbănești and Ciolănești, then settled camp at Vadu-Lat.[139] Ostensibly to "unite with Vladimirescu",[144] the Sacred Band crossed the Milcov into Wallachia, with Ypsilantis reassuring locals that he would maintain good governance in the places he occupied and would not tolerate any violence against them.[145] Reportedly, Vladimirescu sent him letters asking him to withdraw, but these reached Ypsilantis when he was already in Ploiești.[146] While camped there, the Sacred Band organized a military government, comprising Greeks and Wallachian Eterists. Going against Ypsilantis' earlier promises, it staged raids on civilians and multiple confiscations of property.[147] As Cioranu notes, "Romanians never even wanted to hear [Ypsilantis' proclamations], let alone fight under his banner."[148]

The unexpected double invasion alarmed the Divan. Most boyars refused to trust in Vladimirescu's assurances, and fled Bucharest for safety in Transylvania or the countryside, although Olympios and Pharmakis tried to intercept them at Cotroceni and Ciorogârla.[149] A new regency took over, with Metropolitan Dionisie at its helm; ministers included Alecu Filipescu-Vulpea, Fotachi Știrbei, and Grigore Băleanu.[150] The main Pandur force took possession of Bolintin on March 16, sending out patrols to take Cotroceni and Colentina. At Bolintin, Vladimirescu issued his appeal to Bucharesters, informing them that they had nothing to fear once they took up his cause, the cause "of Christendom".[151] He disavowed the exiled boyars, accusing them of having made common cause with the Phanariotes.[152] A second proclamation on March 20 was a call to national unity, "for we are all parts of the same people".[153] It showed his belief in class collaboration, but also, again, his ambition to stand as a national leader, governing for the benefit of the dispossessed.[154]

The Pandurs slowly approached Bucharest from the west. According to one oral tradition, Vladimirescu set up another camp in Cotroceni, his tent planted in the exact spot where physician Carol Davila was later buried.[155] On March 21, the rebel army finally marched into the Wallachian capital. The rebel column, followed by a mass of city-dwellers, walked through the borough later known as Rahova. The procession was led on by an ensign with Vladimirescu's banner of white and blue; Vladimirescu himself held a loaf of bread, to signal prosperity.[156] Upon reaching Dealul Mitropoliei, he requisitioned the home of Zoe Brâncoveanu, turning it into his temporary residence.[157] He and his army were welcomed by Metropolitan Dionisie, who now expressed his "great joy".[158] Those boyars still present in the city proclaimed Vladimirescu's movement to be "useful and redeeming for the people", recognizing him as governor and taking an oath to support him.[159] By contrast, the Arnaut garrison, supporting Fochianos, occupied the Metropolitan Church and Radu Vodă Monastery, defying the Pandurs and shooting at them as they approached.[160] The standoff was ended after friendly negotiations between Fochianos and Vladimirescu, resulting in a ceasefire; Fochianos recognized Vladimirescu's executive and judicial authority over Wallachia.[161]

Conflict with Ypsilantis

Meanwhile, the Sacred Band, under Ypsilantis, had also reached the area, and remained camped outside the city. The two armies "observed each other, without merging into one another; the fundamental contradiction of [their] alliance was becoming more and more apparent".[69] The Eterists pressed on to be allowed entry into Bucharest, but Vladimirescu only offered them a deserted Ghica family manor in Colentina, outside city limits.[153] Ypsilantis and his staff were allowed to visit the city, but found themselves ridiculed by anti-Greek locals, who called theirs an army of "pie-makers".[162] On March 25, Ypsilantis and Vladimirescu had their first meeting. Though they immediately disliked each other, they agreed to a partition of Wallachia: Vladimirescu held on to Oltenia, Bucharest, and southern Muntenia (comprising the Wallachian Plain), while the Sacred Band moved into the Muntenian stretch of the Southern Carpathians.[163] The meeting also gave the Pandurs a chance to observe Ypsilantis' army, which they found to be alarmingly small and under-prepared.[164]

While the partition was ongoing, news came of Russia having denounced Ypsilantis, singled out as an enemy of the Holy Alliance. As Liprandi reports, Vladimirescu privately asked Ypsilantis to complete his transit of Wallachia or withdraw to Moldavia.[165] Ypsilantis hid this detail from his Wallachian contacts as he began taking pledges of support from the various Pandur captains.[166] He also hid from them that the Sacred Band had been anathemized by the Orthodox Patriarch, Gregory V.[167]

On March 15, Pharmakis and his troops, quartered in Lipscani, central Bucharest, broke with the Pandurs. A ceremony organized by actor Costache Aristia consecrated their own army symbols, which echoed Byzantine flags and insignia.[168] As noted by Cioranu, "just about most foreigners who were under Tudor's banners" abandoned their posts in Oltenia and joined the Sacred Band. In the process, they "looted churches, houses, villages, boyars, merchants and everything they could lay hands on, leaving Christians naked [...] and raping wives and girls in front of their husbands and fathers."[169] The same Cioranu notes that the Sacred Band, though only numbering 7,000 men officially, could count then on support from at least 20,000 Greeks and allies.[170] Vladimirescu was nevertheless able to prevent an alliance between Fochianos and Ypsilantis, reminding the former, who was effectively his hostage,[171] of his pledge to the Divan. Together, they began policing the city to prevent Eterist looting.[172] In the mahalale, the Pandurs formed a citizens' self-defense force which may have grouped thousands of Romanians and Romanies.[173] Fochianos commanded the allegiances of 800 loyalist Arnauts and 1,000 armed tanners.[174] According to various reports, the anti-looting policy alienated some of the troops, with as many as 400 men leaving Vladimirescu's camp as a result.[175]

The two armies remained "arrested on the spot",[69] and Vladimirescu began searching for an honorable retreat. On March 27, the boyars, instigated by him, produced a letter which informed foreign powers that the revolution only intended to restore "old privileges" and limit abuse.[176] Vladimirescu also drafted and sent letters of fealty to Mahmud II, limiting his demands to the restoration of elective monarchy in Wallachia; the Ottomans responded that there would be such negotiation lest he surrender his weapons.[69] At the time, the Eterist rear in Moldavia was being attacked by a pro-Ottoman, and Austrian-backed, guerrilla. Led by Gavril Istrati and flying red flags, it managed to chase the Greeks out of Botoșani.[177] As argued by Iorga, this force stood for the "other revolution" (Iorga's emphasis), "opposed, like Tudor's was, to the Greek revolution."[178] On April 5, Vladimirescu acknowledged Moldavian interests, writing to his own Divan, on April 5, about the possibility of a common movement for justice.[179]

During the final days of March, amid rumors of an Ottoman retaliation, Vladimirescu barricaded his Pandurs in Cotroceni Monastery. The new fortifications were designed by the nationalist schoolteacher Gheorghe Lazăr[180] and built using convict labor.[181] The Pandurs also set up lookout points in the Metropolitan Church and at Radu Vodă.[182] On April 14, Vladimirescu inspired his boyars to draft an anti-Eterist proclamation, accusing Ypsilanti of being a dishonored guest in a "country that had received [him] with open arms."[176] The Metropolitan and the Divan also obtained special protection from Tudor, and were moved to a safer location in Belvedere Manor, Ciurel. According to Liprandi, this was a move engineered by Filipescu-Vulpea, who planned the boyars' escape into Transylvania. Liprandi also reports that Vulpea exploited conflicts between Vladimirescu and Fochianos, presenting the latter as a mortal danger for the boyars as well.[183] In fact, the boyars were able to survive Fochianos' attempted raid on Belvedere.[184]

From his barracks in Târgoviște, Ypsilantis responded to Vladimirescu's allegations with a proclamation in which he declared his disappointment, and stated his intention of leaving Wallachia to engage the Ottomans in the Balkans. However, he also began organizing northern Muntenia as an Eterist domain, sacking Vladimirescu's supporters.[35] One report suggests that he also depleted Wallachian ammunition stores, taking away some 6,000 pounds (almost 3 tons) of gunpowder.[185] Meanwhile, Vladimirescu had become more persistent in pursuing peace with the Ottomans. With the help of an Ottoman subject, Nuri Ağa, he circulated allegations that Ypsilantis and Callimachi were both conspirators, hinting that the Sultan could only ensure Wallachia's loyalty by removing the Phanariotes altogether.[186] On April 18, Jianu and Constantin Borănescu were sent to Silistra to parley with the Ottomans. The negotiations were inconclusive, as Wallachians refused to either surrender or take up arms against the Sacred Band.[187] Jianu was arrested there by order of Mehmed Selim Pasha.[188]

Downfall

Overall, Vladimirescu appeared hesitant. Nuri later revealed that he had prepared bribes for Vladimirescu to use on Ypsilantis' captains. This offer was shoved aside by Vladimirescu, who explained that he feared bribing treasonous men.[189] In parallel, with a new proclamation from Cotroceni, Vladimirescu asserted that the Pandurs, Serbs and Bulgarians would stand together against Ottoman encroachment: "we must fire our rifles into Turkish flesh, should they invade."[190] Vladimirescu also reacted to the encroachment by sending his own Ispravnici to Rușii, where Callimachi's Postelnic, Constantin Negri, had attempted to set his base. On Easter Sunday, 600 Ottoman soldiers stormed into Rușii, executing 30 Pandurs along with 170 civilians.[191] A Serbian outlaw, known as Ghiță Haidicul, punished such an incursion on March 21, capturing and maiming some 40 Turks.[192] Vladimirescu no longer intervened when the Bashi-bazouks took Călărași, which they began fortifying in preparation for a larger invasion.[193] His revolt was nevertheless influential south of the Danube, in the Sanjak of Nicopolis. The Bulgarians here rose up in arms, but were put down by the Ottoman Army. Violent persecution against them was curbed, but later mutated into specific actions against Nicopolitan Catholics.[194]

During the last days of April, the Ottoman Army made its coordinated push into Wallachia, with 20,000 to 32,000 soldiers—half of whom headed straight for Moldavia.[195] The other 10,000 or 14,000 were split into two columns: one, placed under Dervish Mehmed Pasha and Ioan Rogobete, entered Oltenia at Calafat; the other, led by Mehmed Selim Pasha and Kara Feiz Ali, set out of Călărași into Muntenia.[196] Of the easternmost force, a regiment under Yusuf Berkofcali entered Brăila en route to Moldavia, where they set fire to Galați and massacred its population.[197] This invasion force consisted of 5,500 infantry and 500 cavalry, assisted by 1,000 Zaporozhian Cossacks of the Danubian Sich; Hilmi Ibrahim Pasha also sailed to the region with some 40 Ottoman river vessels.[198] During their subsequent invasion of Putna County, Berkofcali reportedly isolated some other remnants of Vladimirescu's army.[199]

On May 14–15, the Ottomans held Copăceni and Cățelu, in sight of Bucharest.[200] A firman of the Porte announced that its armies would seek to administer justice, separating "the exploited from exploiters"; it commended Fochianos and Negri for their loyalism, assigning them to govern over Bucharest "until the peoples are as pacified as they have been in the old day."[201] This document described Vladimirescu as a loyalist who demanded "pity and justice", whereas Ypsilantis was dismissed as an "outcast".[202] Both Nuri and an Ottoman general, Kethüda Kara Ahmed, presented new offers for cooperation with the Pandurs, including promises that they would introduce a "settlement that is more favorable to the peasants".[203] Although praised by the firman, Fochianos made a belated show of his conversion of the Eterist cause, parading through Bucharest under a "freedom banner", probably the same one flown by Aristia.[204] Reportedly, Fochainos boasted his ability to "incite all of Bulgaria through his agents and his influence on that bellicose nation."[205]

According to one interpretation, Vladimirescu still considered resisting militarily, but was suspicious of Fochianos, and abandoned this plan in favor of a full retreat.[206] He sent his acolytes Mihali and Ghencea to meet Ypsilantis and Pharmakis at Mărgineni Monastery, reportedly in order to synchronize resistance. Cioranu argues that this was merely a pretext to spy on the Sacred Band.[207] Over those days, the two rival armies, Greek and Wallachian, had already begun moving across Wallachia and toward their respective Carpathian strongholds: Vladimirescu's set course for Oltenia, while Ypsilantis moved into northern Muntenia.[208] The retreat also saw military exercises which tested the troops' resilience and readiness for combat. In one reported incident, Vladimirescu staged an Ottoman attack, ordering some of his soldiers to dress up in Turkish uniforms.[209] Order and morale waned among the Pandurs, prompting Vladimirescu to mete out punishments that were marked by "cruelty."[210] He may have killed as many as 30 of his own soldiers, some of them by his own hand.[211]

The retreat also infuriated the Sacred Band. According to one account, Ypsilantis sent Fochianos in pursuit of the Wallachian column.[212] Other versions suggest that Fochianos, still in contact with the Porte, expected to "play the two sides against each other and then side with the winner",[213] or "an opportunity of making the prince [Ypsilantis] prisoner".[185] Olympios also followed the Pandurs and, upon reaching them, demanded that Vladimirescu return to fight for Bucharest. During a subsequent standoff on the banks of Cârcinov, Vladimirescu agreed to hold deescalation talks.[214] Terror against his own troops had peaked during the Pandurs' passage through Argeș County. At Golești, Vladimirescu ordered the hanging of Ioan Urdăreanu, as punishment for the desertion of four Pandur captains. This incident reportedly caused distress, greatly diminishing Pandur support for their leader.[215] According to the scribe Dârzeanu, Olympios and Pharmakis used the negotiations at Golești, which resulted in a renewed pact with the Sacred Band, to approach Pandur malcontents and probe their commitments.[216]

Vladimirescu also fell out with the Macedonskis, who claimed to have stumbled upon proof that he had embezzled 1 million thaler, and announced that they would surrender him to the Divan for trial.[217] On May 21, Ypsilantis' agents marched into the camp and seized Vladimirescu, confident that none of his soldiers would resist them.[218] Cioranu recalls that the Eterists displayed Vladimirescu's correspondence with the Porte, prompting the Pandurs to rally behind Prodan and Macedonski, identified as their new commanders.[219] They allegedly told them that Olympios would personally handle Vladimirescu's surrender to the Divan.[220] The prisoner was instead taken to the Sacred Band headquarters at Târgoviște, where he was tortured, shot, cut into pieces, and disposed of.[221]

Aftermath

In the immediate aftermath, the Pandurs scattered, with most reentering civilian life; of those who refused to do so, some joined Ypsilantis' force, while others rallied with Anastasie Mihaloglu to form an independent revolutionary force.[222] D. Macedonski, who traveled to Oltenia but remained in contact with the Eterists, was allegedly misinformed by his allies that Vladimirescu was still alive, but exiled.[223] Pandur forces also included some 800 defectors from Golești, under Ioan Oarcă, and Solomon's troops, which had by then withdrawn to Țânțăreni.[224] News of Vladimirescu's capture interrupted Poenaru and Ilarion Gheorghiadis from their diplomatic mission to the Holy Alliance, which pleaded for direct protection from Eterist "cruelty". Having just crossed the border into Transylvania, they opted not to return.[225]

Other Pandur sympathizers followed suit. They include poet Iancu Văcărescu, who took with him a sabre that he claimed had been Vladimirescu's.[226] This influx alarmed Transylvanian authorities, who feared that Pandurs would incite revolution among the Grenz infantry and the serfs of Hunyad County. At Szúliget, several peasants, including the elderly Adam Bedia, were imprisoned for having prepared and armed themselves in expectation of "Tudor's men".[227] Chancellor Sámuel Teleki ordered the Military Border reinforced, and began sending back refugees; the boyars of Corona were deported further inland.[228] However, both Macedonski and Prodan were able to break through the cordon, disguised as merchants.[229]

Meanwhile, all of Bucharest had surrendered to Kara Ahmed. Known in Romanian as Chehaia, he was much feared and disliked by the Wallachians, having tolerated massacres and rapes.[230] In cultural terms, his arrival meant a return to sartorial traditionalism: Western fashion, which had been popular with the young boyars, became politically suspect; society in both Wallachia and Moldavia returned to the standards of Ottoman clothing.[231] The Danubian Sich also participated in Bucharest's occupation, with Kosh Nikifor Beluha organizing the plunder. Beluha returned to Dunavets with a "large bounty", including a church bell.[232] Once evacuated, Târgoviște also surrendered to the Zaporozhian Cossacks, but was not spared large-scale destruction.[233] A legion of some 3,000 soldiers, under Kara Feiz, went in pursuit of the Pandurs, taking Craiova and setting fire to Slatina.[234]

On May 26, at Zăvideni, Mihaloglu, Serdar Djuvara and Solomon were surprised by Kara Feiz. The troops scattered, with most surrendering to the Austrians in Transylvania.[235] Solomon himself would spend six years in Austrian jails.[236] During that interval, the nationalist boyars and bishops, including Dionisie, also escaped into Transylvania.[237] Remaining in the country, Fochianos had turned against Ypsilantis, again pledging himself to Callimachi. He then assisted the invasion force, helping to identify and capture revolutionary sympathizers—including Djuvara, who surrendered and was then executed.[238]

Both rival revolutionary armies were crushed in June–August 1821: Ypsilantis' was routed at Drăgășani; the independent Pandurs were massacred while resisting in northern Oltenia.[239] Repression came with extreme violence: Ioan Dobrescu, the last Wallachian chronicler, reports that "even the mountains stank" from dead bodies.[240] "A large number of dead bodies" were recovered by locals from Colentina manor, while others had been discarded in the marshes of Tei.[171] A regrouped Eterist contingent, led by Pharmakis and Olympios, held out at Secu Monastery in Moldavia; Olympios reportedly detonated himself during the siege, while Pharmakis was taken prisoner and decapitated.[241] Reportedly, only two Eterists who had fought at Secu were still alive in 1828.[242] In July, the Ottomans ambushed Ghiță Haiducul and Vladimirescu's brother Papa, then impaled them.[243]

On August 6, the Ottomans liquidated their nominal ally Fochianos, and all his Arnauts, having first lured them back to Bucharest.[244] Ottoman terror was finally curbed by the Austrian Empire, who threatened with invasion upon being informed that victims of repression included Austrian subjects.[245] On March 14, 1822, the Holy Alliance issued a final warning, which prompted the Sultan to recall his troops.[246]

Historical consequences

Phanariote demise

Despite being met with violent repression, the Eterist ideal remained planted in the Balkans, and, after a decade of fighting, Greek nationalists managed to establish the Kingdom of Greece. The Wallachian revolt had generally more delayed and less conspicuous results. Sociologist Dimitrie Drăghicescu was particularly dismissive of the 1821 movement, viewing it as a sample of Romanian "passivity": "[it] was so unlike a real, courageous, revolution; it can be reduced to a rally of no consequence."[247] According to Djuvara, Vladimirescu failed because "the time had not yet come for what he intended to accomplish": "he never managed to entice the peasant mass of the villages, where his message never penetrated the way it should have. [...] The class he could have relied on—and to which he did not himself belong—, that of traders and artisans, the barely nascent bourgeoisie, was not at that junction structured enough to represent a political force."[248]

Vârtosu also describes the Pandurs were a "first generation of democracy", but a "sacrificial generation"—"there was little ideological preparation in the Country".[249] Similarly, Potra notes that the "revolutionary movement of 1821" was actually hailed by Bucharesters as an opportunity for "national liberation", "but could not have achieved this." Instead, "this first revolution, which opened the way for a line of struggles [...] for the independence and freedom of the Romanian nation, has violently shaken up the feudal order, contributing to the demise of the Phanariote regime."[250] Maciu contrarily believes that Vladimirescu's movement could have in fact brought about "bourgeois rule" and the capitalist mode of production, but that it never took off as an actual revolution.[251] Karl Marx once categorized the 1821 events as a "national insurrection" rather than "peasants' revolt". As Maciu concludes, this acknowledges that the revolt was carefully planned, but fell short of stating a bourgeois objective.[252]

Vladimirescu endured in the symbolic realm, a hero of folklore and literature, "a legend [...] which will serve to nurture the builders of modern Romania."[248] As poet Ion Heliade Rădulescu argued, the Pandurs had managed to take Wallachia out of her "somnolence" and "degeneracy".[253] In its immediate aftermath, however, the revolt sparked mainly negative commentary. A cluster of chroniclers, boyar and conservative, still dominated the literary scene. They include Dobrescu, Alecu Beldiman, Naum Râmniceanu, and Zilot Românul, all of whom disliked Vladimirescu.[254] A noted exception to this rule was the Aromanian patriot Toma Gheorghe Peșacov.[255] Though he probably never approved of Vladimirescu's social discourse, Dinicu Golescu subdued his criticism, and expressed his own concerns about the corvée system.[256] Through its parallel depiction in folklore, the Pandur rising was transposed into foreign literature: some of the first ballads about Vladimirescu or Fochianos were collected in the Bessarabia Governorate by Alexander Pushkin (who was enthusiastic about the revolt, as early as February 1821),[257] and reused as literary sources by Alexander Veltman.[258] Semiotician Juri Lotman argues that Pushkin wanted to weave the Wallachian revolt into a planned sequel to Eugene Onegin.[259]

The revolt had sent out signals to the Ottoman government, and produced relevant policy changes. One of the early signs of change came just months after its suppression, when the Divan restored Târgoviște to its citizens, and the "cartel of the four [princely] families" was formally annulled.[260] In July 1822, after having heard a new set of boyar complaints which had Russian and Austrian backing, the Sultan put an end to the Phanariote regime, appointing Grigore IV Ghica (the former Caimacam of 1821) and Ioan Sturdza as "native" Princes of Wallachia and Moldavia, respectively.[261] Trying to appease Russia, in 1826 the Ottoman Empire also signed the Akkerman Convention, which set commercial freedoms for Wallachians and the Moldavians, and allowed the Divans to elect their Princes for seven-year terms.[262] The new regimes set a standard of Westernization and cultural Francophilia, giving impetus to the National Party and the local Freemasonry.[263] Prince Ghica, having recovered his Colentina manor, rebuilt it as a Neoclassical palace, in line with the Westernized preferences of his subjects.[171]

Pandur revival

According to Jelavich, repressive measures against the Romanian peasantry remained subdued: "although villages were disarmed and attempts were made to collect the taxes and labor obligations that were due from the period of the rebellion, the entire matter was handled with relative moderation."[264] Overall, however, the Vladimirescu revolt and the Sacred Band contributed to the "tangible degradation" of Wallachia's economy, which was only enhanced by the "terrible plundering" of Ottoman occupation.[265] Le Moniteur Universel reported that "everything in the countryside has been destroyed; what Greek revolutionaries could not accomplish, the Ottoman vanguard did."[266] A monetary crisis, sparked by the events of 1821 and cemented by the recovery of boyar privilege, affected both principalities for an entire decade.[267]

Troubles continued under Ghica, including raids by Arnauts hiding in Transylvania and a number of riots. In 1826 Simion Mehedințeanu attempted a new uprising at Padeș; he was defeated and hanged.[268] Despite Ottoman concessions, Wallachia and Moldavia fell to a new Russian occupation in 1828–1829. During this phase, the Pandurs were revived by Governor Pavel Kiselyov and Costache Ghica, who created new units throughout Muntenia. The Divan, fearful of rebellion, reduced the number of Oltenian recruits, while Muntenians simply kept away.[269] Liprandi commanded his own Russian unit in the campaign, giving employment to many Arnauts who had lived the previous seven years as marauding outlaws.[270] This moment saw the rise of a new Pandur commandant, Gheorghe Magheru. After policing Oltenia, he saw action again at Șișești, repelling 3,000 Ottomans with a force of 450 Pandurs.[110]

The Russian regime was extended by a new constitutional arrangement, Regulamentul Organic, which made the two countries Russian-controlled territories under Ottoman suzerainty. The corresponding Treaty of Adrianople enhanced commercial freedoms, and is credited as the birth certificate of Romanian capitalism, with its modern middle class and a new standard of living.[271] The full reestablishment of Wallachia's professional military under Russian command was, according to Potra, also a means to perpetuate a "strong revolutionary tradition" that included the Pandur unrest.[272] The new system continued to be perceived as oppressive by the peasants, giving rise to various attempted revolts, particularly in Oltenia. In the 1830s, Gorj and Dolj witnessed peasant rioters shouting slogans such as "Tudor has come back to life!"[273] A veteran of 1821, Nicolae Groază, reverted to a life of crime. This "last Romanian hajduk", captured and tried in 1838, defended himself by noting that he followed in the footsteps of Vladimirescu, Pharmakis, and Solomon.[274]

During this interval, Vladimirescu associate Poenaru became organizer of Wallachian education. Although he had abandoned his youthful radicalism, Poenaru encouraged research into the revolt, as well as artistic homages to Vladimirescu.[275] The Pandurs' colors may also have inspired political symbolism adopted the "native" rulers. Vladimirescu's banner, though blue-and-white, had blue-yellow-red tassels; a memory of this color scheme may have inspired the adoption of Wallachian ensigns and Romanian tricolors,[276] possibly through an intermediary flag designed in Craiova by Magheru's daughter Maria Alexandrina.[277] In Moldavia, as early as 1843, historian Mihail Kogălniceanu praised Vladimirescu for having "raised the national flag" to demand "a national government, founded on a liberal charter."[278]

Later echoes

Tensions between nationalists and the Russian protectors, first evidenced with the 1842 ouster of Wallachian Prince Alexandru II Ghica,[279] were enhanced by anti-Russian conspiracies. Before the full-scale Wallachian Revolution of 1848, one such revolutionary fraternity united Dimitrie Macedonski with the young liberal boyars Mitică Filipescu and Nicolae Bălcescu.[280] The period also saw the uprising glorified in poetry by Cezar Bolliac and Alexandru Pelimon, then explored in adventure novels by Constantin Boerescu, Dimitrie Bolintineanu, and Nicolae Filimon.[281] The uprising and its impact on the Reformed Church missionaries are also retold in a short story by Mór Jókai, from first-hand reports by Károly Sükei.[282] This revival of interest was contrasted by conservative views. Poet and essayist Grigore Alexandrescu viewed Vladimirescu as "nearsighted and cruel",[283] while Grigore Lăcusteanu defined the uprising as a "first attempt to murder Romanian aristocracy, so that the nobodies and the churls may take its place".[284] Solomon, though he had served Vladimirescu and remained a Pandur commander, also turned conservative during the 1840s.[285]

Eventually, the Regulamentul regime was ended by the Crimean War, which also opened the way for the creation of a Romanian state from the union of Moldavia and Wallachia. Iancu Vladimirescu, who was Papa's posthumous son and Tudor's nephew, was integrated by the modernized administration of the United Principalities, serving minor functions in Gorj.[286] According to Djuvara, during this process "nationalist" boyars imposed on historiography a narrative that obscured Vladimirescu's views on class conflict, preserving a memory of the revolution as only an anti-Phanariote and nativist phenomenon.[287] The social dimension of 1821 was again revisited in the 1860s by egalitarian liberals such as Bogdan Petriceicu Hasdeu, who directed Constantin D. Aricescu to write a new history of the revolt.[288]

This populist trend was continued following the proclamation of a Kingdom of Romania. The original rebel flag, preserved by the Cacalațeanu family, was recovered in 1882 and assigned to the Romanian Land Forces by Hasdeu.[289] In the 1890s, Constantin Dobrescu-Argeș, the agrarian leader and Pandur descendant, made reference to the Vladimirescu revolt as a precursor to his own movement.[290] In 1913, Gheorghe Munteanu-Murgoci founded a youth organization called Pandurs, later merged into Romania's Scouts.[291] During the World War I occupation of Oltenia, Victor Popescu set up partisan units directly modeled on the 1821 rebels.[292] Vladimirescu was also recovered by the pantheon of Greater Romania, one of the "warrior heroes" depicted in the Romanian Atheneum.[293]

Several authors revisited the events during the interwar, with topical plays being written by Iorga and Ion Peretz.[294] As nationalists, the 1821 Pandurs also had cult status in fascist propaganda put out by the Iron Guard during the 1930s and '40s,[295] and lent their name to a paramilitary subgroup of the Romanian Front.[296] This symbolism was challenged from the left by the Radical Peasants' Party, who mustered thousands of Pandur reenactors for its Gorj rally in May 1936;[297] the underground Communist Party, meanwhile, cultivated Vladimirescu's legendary status as an exponent of the "popular masses".[298] During World War II, Romania fought as an ally of Nazi Germany. Prisoners of war held by the Soviet Union were then coaxed into forming a Tudor Vladimirescu Division, which also helped communize the Land Forces.[299]

With the imposition of a communist state, the Pandurs came to be seen as revolutionary precursors, and also as figures of anti-Western sentiment. Communist Romanian and Soviet historiography glossed over differences between Ypsilantis and Vladimirescu, depicting both as Russian-inspired liberators of the Balkans.[300] In his pseudohistorical articles of 1952–1954, Solomon Știrbu alleged that Vladimirescu's revolution had been sparked by the Decembrist movement,[301] and had been ultimately defeated by "agents of the English bourgeoisie".[302] During De-Stalinization, Oțetea received political approval to curb this trend, though his own conclusions were soon challenged by other exponents of Marxist historiography, including David Prodan.[303]

Vladimirescu was still perceived as mainly a social revolutionary, but maintained a hero's status throughout the regime's latter nationalist phase.[304] In 1966, Nicolae Ceaușescu established an Order of Tudor Vladimirescu, as Communist Romania's third most important distinction.[305] During this interval, the revolt was reconstructed in film, with Tudor. Viewed at the time as a significant achievement in Romanian historical cinema,[306] it was also the lifetime role for the lead, Emanoil Petruț.[307] Despite Oțetea's stated objections, screenwriter Mihnea Gheorghiu downplayed all connections between Vladimirescu and the Eteria, and elevated his historical stature.[308] The film provided a venue for criticism of Russia, but also depicted Vladimirescu as an early champion of nationalization.[309] During the 1970s, following a revival of historical fiction, the revolt was a subject matter for Paul A. Georgescu, with a critically acclaimed novel, also named Tudor.[310] Later film productions dealing with the events include the 1981 Ostern Iancu Jianu, haiducul, which also modifies the historical narrative to endorse the regime's theses.[311]

By the 1980s, the scholarly bibliography on the revolt of 1821 had become "enormous".[312] Following the anti-communist revolution of 1989, Vladimirescu was preserved as a political symbol by some of the nationalist groups, including the Greater Romania Party.[313] Others perceived his revolt as the symbol of an Oltenian specificity. On March 21, 2017, marking the 196th anniversary of Bucharest's taking by the Pandurs, the Chamber of Deputies of Romania passed a law to celebrate the occasion annually, as Oltenia Day.[314] It had been previously accepted by the Senate of Romania on November 1, 2016 and promulgated by the President of Romania Klaus Iohannis on April 13, 2017, making it official.[315]

Notes

- ^ Djuvara, pp. 261–262

- ^ Iliescu & Miron, pp. 9–10

- ^ Djuvara, pp. 70–71

- ^ Bogdan Murgescu, România și Europa. Acumularea decalajelor economice (1500–2010), pp. 32–37. Iași: Polirom, 2010. ISBN 978-973-46-1665-7

- ^ Djuvara, p. 70. See also Iliescu & Miron, p. 10

- ^ Djuvara, pp. 73–74; Iorga (1921), pp. 326–327 and (1932), pp. 5–7

- ^ Djuvara, pp. 73–74

- ^ Maciu, pp. 935–936

- ^ Anton Caragea, "Fanarioții: vieți trăite sub semnul primejdiei. 'Grozăviile nebunului Mavrogheni'", in Magazin Istoric, November 2000, p. 70

- ^ Ciobotea & Osiac, pp. 143–144

- ^ Djuvara, pp. 281–283. See also Maciu, p. 934

- ^ Djuvara, pp. 283, 356; Vârtosu (1962), passim

- ^ Djuvara, pp. 283–284, 295

- ^ Bogdan-Duică, p. 41; Cernatoni, pp. 40–41; Ciobotea & Osiac, pp. 143–146; Dieaconu, pp. 45, 47; Djuvara, pp. 284–286, 297, 299, 356; Finlay, p. 123; Georgescu, p. 100; Iliescu & Miron, pp. 12–13; Iorga (1921), pp. XI, 3–4, 189, 232 and (1932), p. 54; Iscru, pp. 678, 680; Lăcusteanu & Crutzescu, p. 37; Maciu, pp. 936, 939; Nistor, p. 889; Rizos-Nerulos, p. 284; Vârtosu (1945), p. 345 and (1962), pp. 530, 545; Vianu & Iancovici, pp. 75–77

- ^ Vârtosu (1962), pp. 533–535, 545

- ^ Djuvara, pp. 288–289

- ^ Djuvara, pp. 293–295

- ^ Djuvara, p. 291

- ^ Maciu, pp. 936, 940. See also Iscru, pp. 679–680

- ^ Cernatoni, p. 42; Maciu, p. 936

- ^ Maciu, p. 936

- ^ Djuvara, pp. 295–296

- ^ Cernatoni, p. 42. See also Popp, p. XII

- ^ Djuvara, p. 191

- ^ Nistor, p. 887

- ^ Ciobotea & Osiac, p. 146

- ^ Dieaconu, p. 46

- ^ Iorga (1921), pp. 228–229

- ^ Vianu & Iancovici, pp. 74–75. See also Iliescu & Miron, p. 12

- ^ Djuvara, p. 296; Iorga (1921), pp. 353–354

- ^ Djuvara, p. 296; Finlay, p. 118; Georgescu, p. 97; Iorga (1921), pp. 231, 353–354 and (1932), pp. 24, 25; Lăcusteanu & Crutzescu, pp. 37, 227; Papacostea, p. 10; Potra (1963), p. 64

- ^ Djuvara, p. 297

- ^ Cernatoni, p. 43; Djuvara, p. 297; Iliescu & Miron, p. 14

- ^ Cernatoni, pp. 42–43. See also Iliescu & Miron, pp. 12–14; Rizos-Nerulos, p. 284; Vianu & Iancovici, pp. 74, 82–84

- ^ a b Maciu, p. 946

- ^ Jelavich, pp. 22, 24, 302

- ^ Iliescu & Miron, pp. 40–41

- ^ Iorga (1932), p. 25

- ^ Iscru, pp. 684–686

- ^ Vianu & Iancovici, pp. 77–79, 81

- ^ a b Vianu & Iancovici, p. 79

- ^ Vianu & Iancovici, pp. 74, 77

- ^ Cernatoni, p. 43; Gârleanu, pp. 57–58; Iliescu & Miron, pp. 14, 40; Iorga (1921), pp. 4–5, 233, 356 and (1932), pp. 27, 53; Popa & Dicu, pp. 98–99; Potra (1963), p. 64; Vianu & Iancovici, p. 78. See also Georgescu, pp. 100–102

- ^ Gârleanu, pp. 57–58; Vianu & Iancovici, p. 78

- ^ Georgescu, pp. 102–103; Maciu, p. 933

- ^ Iorga (1921), pp. XII–XIV

- ^ Liu, pp. 298–300

- ^ Bochmann, p. 107

- ^ Bochmann, pp. 107–108

- ^ Iscru, pp. 682–683

- ^ Șerban, pp. 282–283

- ^ Potra (1963), pp. 22–23

- ^ Djuvara, p. 89

- ^ Djuvara, pp. 285–286, 289, 297

- ^ Iorga (1921), p. VIII

- ^ Maciu, p. 933

- ^ Djuvara, pp. 136, 228, 297, 299–300; Maciu, pp. 941, 944; Theodorescu, p. 221. See also Cernatoni, pp. 40–41, 46

- ^ Theodorescu, pp. 208–209

- ^ Djuvara, p. 300; Georgescu, pp. 100, 103; Iorga (1932), pp. 27, 51; Iscru, pp. 676–680; Maciu, p. 941

- ^ Dima et al., p. 132; Djuvara, p. 300; Georgescu, p. 103; Iorga (1932), p. 51

- ^ Djuvara, p. 300; Iorga (1921), pp. IX–X, 61; Maciu, p. 945

- ^ Șerban, p. 280

- ^ Iorga (1921), pp. VII–VIII

- ^ Maciu, pp. 934, 937–939, 945, 947–948

- ^ Vârtosu (1945), pp. 345–346

- ^ Djuvara, p. 298; Iorga (1921), pp. X–XII

- ^ Șerban, pp. 279–280

- ^ Nicolae Chiachir, Gelcu Maksutovici, "Orașul București, centru de sprijin al mișcării de eliberare din Balcani (1848—1912)", in București. Materiale de Istorie și Muzeografie, Vol. 5, 1967, p. 279

- ^ a b c d Djuvara, p. 298

- ^ Palade, p. 36

- ^ Djuvara, p. 299

- ^ Finlay, p. 123

- ^ Karpat, pp. 406–407

- ^ Iliescu & Miron, pp. 40–43; Iorga (1932), pp. 53–54

- ^ Vianu & Iancovici, p. 70

- ^ Nestor Camariano, "Rhigas Velestinlis. Complètements et corrections concernant sa vie et son activité", in Revue des Études Sud-est Européennes, Vol. XVIII, Issue 4, October–December 1980, pp. 704–705

- ^ Rizos-Nerulos, p. 284

- ^ Dieaconu, pp. 47–48; Djuvara, pp. 297, 298; Finlay, pp. 122, 123; Maciu, p. 936; Palade, p. 36; Rizos-Nerulos, p. 284; Vianu & Iancovici, pp. 82–83

- ^ Djuvara, pp. 296–297; Finlay, pp. 126–128; Georgescu, pp. 102–103; Iliescu & Miron, pp. 11, 16–17, 40–41; Iorga (1921), pp. 191–192, 266, 269–272 and (1932), pp. 26, 58; Jelavich, pp. 23–24; Liu, pp. 300–301; Maciu, p. 944; Palade, pp. 39–40; Rizos-Nerulos, p. 310; Șerban, p. 285. See also van Meurs, pp. 48–49; Vianu & Iancovici, pp. 71–72

- ^ Djuvara, p. 298; Finlay, pp. 126–128; Iorga (1921), pp. 190, 266–268, 336–337, 362; Maciu, p. 944

- ^ Iorga (1921), pp. 4–5, 233

- ^ Cernatoni, p. 43; Gârleanu, p. 58; Iorga (1921), pp. 5–6, 10, 13, 233–234, 245, 356; Potra (1963), p. 64

- ^ Cernatoni, p. 43; Gârleanu, pp. 58, 60; Iliescu & Miron, pp. 14, 15; Iorga (1921), pp. 6–7, 10, 189, 216–217, 233–234, 241, 245

- ^ Cernatoni, p. 43; Ciobotea & Osiac, p. 147; Gârleanu, p. 59; Iorga (1921), pp. 6–7; Jelavich, p. 23

- ^ Theodorescu, p. 221

- ^ Ciobotea & Osiac, p. 147; Gârleanu, p. 59; Iorga (1921), pp. 6–7, 234–235. See also Iliescu & Miron, p. 15

- ^ Cernatoni, p. 43; Iliescu & Miron, p. 15; Iorga (1921), pp. 7–10, 189–190, 238–241, 329–330; Jelavich, p. 23; Maciu, pp. 942–943, 945, 947; Vianu & Iancovici, p. 85

- ^ Vianu & Iancovici, p. 85

- ^ Cernatoni, pp. 43–44; Iorga (1921), pp. 10–24

- ^ Iorga (1921), pp. 12–13, 24–28, 40–42, 330–331; Potra (1963), p. 64. See also Iorga, (1932), p. 27

- ^ Maciu, p. 942; Vârtosu (1945), p. 347

- ^ a b c Cernatoni, p. 44

- ^ Iorga (1921), pp. 24–30; Potra (1963), pp. 64–65

- ^ Iorga (1921), pp. 13–18, 24, 34–41, 236–238, 241–246, 330–332, 357–358. See also Ciobotea & Osiac, pp. 148, 152; Dieaconu, p. 48; Iorga (1932), p. 27

- ^ Iorga (1921), pp. 34–37; Vianu & Iancovici, pp. 79–80

- ^ a b Gârleanu, p. 60

- ^ Iorga (1921), p. 54

- ^ Dieaconu, pp. 47, 56–57

- ^ Ciobotea & Osiac, pp. 148–150

- ^ a b Vianu & Iancovici, pp. 80–81

- ^ Cernatoni, p. 44; Djuvara, pp. 297–298; Georgescu, p. 118; Iorga (1921), pp. 46–47; Liu, p. 299. See also Bochmann, pp. 108–111; Maciu, p. 943; Popp, p. XIII

- ^ Djuvara, p. 297; Iorga (1921), pp. 47–48

- ^ Iorga (1921), pp. 45–52, 54, 247, 331–332

- ^ Iorga (1921), pp. 48–51, 244–247, 331

- ^ Maciu, p. 943

- ^ Iorga (1921), pp. 240–241, 257, 269, 289–290, 331

- ^ a b Vianu & Iancovici, p. 80

- ^ Djuvara, pp. 291, 299

- ^ Potra (1963), pp. V, 4–5, 63–69

- ^ a b I. D. Suciu, "Recenzii. Apostol Stan, Constantin Vlăduț, Gheorghe Magheru", in Studii. Revistă de Istorie, Vol. 23, Issue 6, 1970, p. 1248

- ^ Gârleanu, p. 60; Iorga (1921), pp. 10–13

- ^ a b Ciobotea & Osiac, p. 150

- ^ Radu Ștefan Ciobanu, "Evoluția ideii de independență la românii dobrogeni între revoluția condusă de Tudor Vladimirescu și războiul pentru neatîrnarea neamului (1821—1877)", in Muzeul Național, Vol. VI, 1982, p. 220

- ^ Ciobotea & Osiac, pp. 149–150; Djuvara, p. 300

- ^ Djuvara, p. 300. See also Dieaconu, pp. 47–50; Maciu, pp. 947–948

- ^ Iorga (1921), pp. 328–329

- ^ Șerban, p. 285

- ^ Potra (1963), p. 65. See also Maciu, p. 941

- ^ Gârleanu, p. 57; Vianu & Iancovici, pp. 82–84

- ^ Iorga (1921), pp. 58, 216–217. See also Dieaconu, pp. 48, 49

- ^ Lăcusteanu & Crutzescu, pp. 37–38

- ^ Popp, p. V

- ^ Iorga (1921), pp. 53–55, 333–334

- ^ Cernatoni, p. 45; Iorga (1921), pp. 246–249, 256–257, 333–334, 338–339 and (1932), p. 28; Vianu & Iancovici, p. 80–81

- ^ Finlay, pp. 122–123; Iorga (1921), pp. 256–257, 334, 335

- ^ Ardeleanu, pp. 144–149; Dieaconu, pp. 46–47; Finlay, pp. 117–122; Iliescu & Miron, pp. 16, 21–24; Iorga (1921), p. 332; Rizos-Nerulos, pp. 288–289. See also Cochran, p. 312; Jelavich, p. 25; Șerban, p. 283

- ^ Djuvara, p. 296

- ^ Ardeleanu, pp. 154, 159; Iorga (1921), p. 266

- ^ Ardeleanu, pp. 148–149

- ^ Djuvara, p. 297; Finlay, p. 122

- ^ Iorga (1921), pp. 246–247

- ^ Iliescu & Miron, p. 16. See also Liu, p. 300; Vârtosu (1945), pp. 344–345

- ^ Cernatoni, p. 45; Ciobotea & Osiac, p. 153. See also Djuvara, p. 297; Jelavich, p. 24

- ^ Iorga (1932), p. 54

- ^ Iorga (1921), p. 363

- ^ Iorga (1921), pp. 254–255, 257–259, 290

- ^ Iorga (1921), pp. 189–190, 260–261, 334, 363

- ^ Iorga (1921), pp. 203, 255, 257, 268, 290, 337, 363, 364

- ^ a b Cernatoni, p. 45

- ^ Popa & Dicu, pp. 98–100

- ^ Iorga (1921), p. 331

- ^ Iorga (1921), pp. 57, 331

- ^ Iorga (1921), pp. 257–259, 358–359. See also Iscru, p. 676

- ^ Cochran, p. 313

- ^ Cernatoni, pp. 45, 46; Iliescu & Miron, pp. 24–25; Iorga (1921), pp. 52, 55–57, 59, 250–252, 266

- ^ Vianu & Iancovici, p. 84. See also Iliescu & Miron, pp. 23–24, 25

- ^ Iorga (1921), pp. 59–61

- ^ Iorga (1921), p. 266

- ^ Cernatoni, pp. 45, 50; Iorga (1921), pp. 53–54, 55, 57–60, 65–66, 255–257, 266, 332–333, 361, 363. See also Dieaconu, p. 49

- ^ Iorga (1921), pp. 57–58, 74, 255–257

- ^ Cernatoni, pp. 45–46; Iorga (1921), pp. 260–261, 386–387

- ^ Maciu, pp. 943–944

- ^ a b Cernatoni, p. 46

- ^ Iorga (1921), pp. 263–265; Maciu, p. 942

- ^ Paul Cernovodeanu, Nicolae Vătămanu, "Considerații asupra 'calicilor' bucureșteni în veacurile al XVII-lea și al XVIII-lea. Cîteva identificări topografice legate de așezările lor", in București. Materiale de Istorie și Muzeografie, Vol. III, 1965, p. 38

- ^ Ciobotea & Osiac, p. 153

- ^ Cernatoni, p. 46; Iorga (1921), pp. 58, 261–262, 335, 359–360

- ^ Potra (1963), p. 19

- ^ Cernatoni, p. 46; Maciu, pp. 944–945

- ^ Iorga (1921), pp. 58, 262–263, 335–336 and (1932), p. 28

- ^ Iorga (1921), pp. 335–336

- ^ Iorga (1921), p. 266; Papacostea, p. 10

- ^ Djuvara, p. 298; Iliescu & Miron, p. 17; Iorga (1921), p. 338. See also Georgescu, p. 103

- ^ Cernatoni, pp. 46–47; Iorga (1921), pp. 266–269, 362

- ^ Iorga (1921), p. 84; Vianu & Iancovici, pp. 84–85, 343

- ^ Iorga (1921), pp. 267–268; Vianu & Iancovici, pp. 84–85

- ^ Iorga (1921), pp. 275–282

- ^ Iorga (1921), pp. 272–274, 362

- ^ Iorga (1921), p. 254

- ^ Iorga (1921), pp. 261–262, 268–269

- ^ a b c Ionel Zănescu, Camelia Ene, "Palatul 'de la Colentina-Tei'", in Magazin Istoric, May 2002, p. 54

- ^ Iorga (1921), pp. 273–274, 283, 288–289, 360–361. See also Dieaconu, pp. 48–49; Finlay, pp. 126–127

- ^ Iorga (1921), pp. 360–361

- ^ Iorga (1921), p. 284

- ^ Șerban, p. 284

- ^ a b Cernatoni, p. 47

- ^ Iorga (1919), pp. 172–175

- ^ Iorga (1919), p. 174

- ^ Cernatoni, p. 47; Dima et al., p. 233; Maciu, p. 945

- ^ Bogdan-Duică, p. 57; Dima et al., pp. 160, 163, 262; Popp, pp. XII–XIII

- ^ Iorga (1921), pp. 61–62, 337–338

- ^ Cernatoni, p. 47; Iliescu & Miron, p. 17

- ^ Vianu & Iancovici, pp. 81–82

- ^ Iorga (1921), pp. 67–68, 284–285

- ^ a b Finlay, p. 129

- ^ Iorga (1921), pp. 65–67. See also Finlay, p. 128

- ^ Cernatoni, p. 47; Vianu & Iancovici, pp. 85–86. See also Dieaconu, p. 50; Iliescu & Miron, p. 17; Iorga (1921), p. 363 and (1932), pp. 28, 58

- ^ Dieaconu, p. 50

- ^ Vianu & Iancovici, pp. 85–86