Cyrillic script

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2007) |

| Cyrillic alphabet | |

|---|---|

| |

| Script type | |

Time period | Earliest variants exist circa 940 |

| Direction | Left-to-right |

| Languages | Many Slavic languages, and almost all languages in the former Soviet Union (see Languages using Cyrillic) |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | Phoenician alphabet

|

Sister systems | Latin alphabet Coptic alphabet Armenian |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Cyrl (220), Cyrillic |

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Cyrillic |

| U+0400 to U+052F | |

The Cyrillic alphabet (pronounced /sɪˈrɪlɪk/ also called azbuka, from the old name of the first two letters) is actually a family of alphabets, subsets of which are used by certain Slavic languages—Belarusian, Bulgarian, Macedonian, Russian, Rusyn, Serbian, and Ukrainian—as well as many other languages of the former Soviet Union, Asia and Eastern Europe. It has also been used for other languages in the past. Not all letters in the Cyrillic alphabet are used in every language with which it is written.

The alphabet has official status with many organisations. With the accession of Bulgaria to the European Union on January 1, 2007, Cyrillic became the third official alphabet of the EU.

History

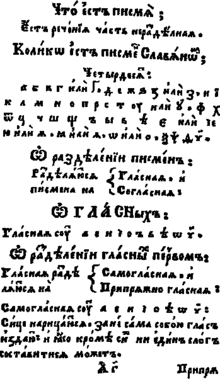

The layout of the alphabet is derived from the early Cyrillic alphabet, itself a derivative of the Glagolitic alphabet, a ninth century uncial cursive usually credited to two monks and brothers, Saint Cyril and Saint Methodius of Thessaloniki.

Although it is widely accepted that the Glagolitic alphabet was invented by Saints Cyril and Methodius, the origins of the early Cyrillic alphabet are still a source of much controversy. Though it is usually attributed to Saint Clement of Ohrid, disciple of Saint Cyril and Saint Methodius from Bulgarian Macedonia, the alphabet is more likely to have developed at the Preslav Literary School in northeastern Bulgaria, where the oldest Cyrillic inscriptions have been found, dating back to the 940s. The theory is supported by the fact that the Cyrillic alphabet almost completely replaced the Glagolitic in northeastern Bulgaria as early as the end of the tenth century, whereas the Ohrid Literary School—where Saint Clement worked—continued to use the Glagolitic until the twelfth century. Of course, as the disciples of St. Cyril and Methodius spread throughout the First Bulgarian Empire, it is likely that these two main scholarly centres were a part of a single tradition.

Among the reasons for the replacement of the Glagolithic with the Cyrillic alphabet is the greater simplicity and ease of use of the latter and its closeness with the Greek alphabet, which had been well known in the First Bulgarian Empire.

There are also other theories regarding the origins of the Cyrillic alphabet, namely that the alphabet was created by Saint Cyril and Saint Methodius themselves, or that it preceded the Glagolitic alphabet, representing a "transitional" stage between Greek and Glagolitic cursive, but these have been disproved. Although Cyril is almost certainly not the author of the Cyrillic alphabet, his contributions to the Glagolitic and hence to the Cyrillic alphabet are still recognised, as the latter is named after him.

The alphabet was disseminated along with the Old Church Slavonic liturgical language, and the alphabet used for modern Church Slavonic language in Eastern Orthodox and Eastern Catholic rites still resembles early Cyrillic. However, over the following ten centuries, the Cyrillic alphabet adapted to changes in spoken language, developed regional variations to suit the features of national languages, and was subjected to academic reforms and political decrees. Today, dozens of languages in Eastern Europe and Asia are written in the Cyrillic alphabet.

As the Cyrillic alphabet spread throughout the Slavic world, it was adopted for writing local languages, such as Old Ruthenian. Its adaptation to the characteristics of local languages led to the development of its many modern variants, below.

| А | Б | В | Г | Д | Є | Ж | Ѕ | З | И | І |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 10 | ||

| К | Л | М | Н | О | П | Ҁ | Р | С | Т | Ѹ |

| 20 | 30 | 40 | 50 | 70 | 80 | 100 | 200 | 300 | 400 | |

| Ф | Х | Ѡ | Ц | Ч | Ш | Щ | Ъ | Ы | Ь | Ѣ |

| 500 | 600 | 800 | 900 | 90 | ||||||

| Ю | ІА | Ѧ | Ѩ | Ѫ | Ѭ | Ѯ | Ѱ | Ѳ | Ѵ | Ѥ |

| 60 | 700 | 9 |

Capital and lowercase letters were not distinguished in old manuscripts.

Yeri (Ы) was originally a ligature of Yer and I (ЪІ). Iotation was indicated by ligatures formed with the letter I: ІА (ancestor of modern ya, я), Ѥ, Ю (ligature of I and ОУ), Ѩ, Ѭ. Many letters had variant forms and commonly-used ligatures, for example И=І=Ї, Ѡ=Ѻ, ОУ=Ѹ, ѠТ=Ѿ.

The letters also had numeric values, based not on the native Cyrillic alphabetical order, but inherited from the letters' Greek ancestors. See Cyrillic numerals.

The early Cyrillic alphabet is difficult to represent on computers. Many of the letterforms differed from modern Cyrillic, varied a great deal in manuscripts, and changed over time. Few fonts include adequate glyphs to reproduce the alphabet. The current Unicode standard does not represent some significant letterform variations, and omits some characters, such as Cyrillic dotless I, iotified Yat, abbreviated Yer ("Yerok"), and many ligatures.

See also: Glagolitic alphabet.

Letter-forms and typography

The development of Cyrillic typography passed directly from the medieval stage to the late Baroque, without a Renaissance phase as in Western Europe. Late Medieval Cyrillic letters (still found on many icon inscriptions even today) show a marked tendency to be very tall and narrow; strokes are often shared between adjacent letters.

Peter the Great, Czar of Russia, mandated the use of westernized letter forms in the early eighteenth century. Over time, these were largely adopted in the other languages that use the alphabet. Thus, unlike modern Greek fonts that retained their own set of design principles (such as the placement of serifs, the shapes of stroke ends, and stroke-thickness rules), modern Cyrillic fonts are much the same as modern Latin fonts of the same font family. The development of some Cyrillic computer typefaces from Latin ones has also contributed to the visual Latinization of Cyrillic type.

Cyrillic uppercase and lowercase letter-forms are not as differentiated as in Latin typography. Upright Cyrillic lowercase letters are essentially small capitals (with the few exceptions: "а", "е", "p", "y" adopted Western lowercase shapes, lowercase "ф" is typically designed under the influence of "p", lowercase "Б" is "б", one of traditional hand-written forms), although a good-quality Cyrillic typeface will still include separate small caps glyphs.[1]

Cyrillic fonts, as well as Latin ones, have roman and italic variants (practically all popular modern fonts include parallel sets of Latin and Cyrillic letters, where many glyphs, uppercase as well as lowercase, are simply shared by both). However, the native font terminology in Slavic languages (for example, in Russian) does not use the words "roman" and "italic" in this sense.[2] Instead, the nomenclature follows German naming patterns:

- A roman-style font (Cyrillic, Latin, Greek...) is simply called pryamoy shrift (‘upright font‘)—compare with Normalschrift (‘regular font‘) in German

- An italic font is called kursiv (literally ‘cursive’) or kursivniy shrift (‘cursive font’)—from the German word Kursive, meaning italic typefaces and not actual cursive

- Cursive handwriting is rukopisniy shrift (‘hand-written font’) in Russian—in German: Kurrentschrift or Laufschrift, both meaning literally ‘running font’

Similarly to the Latin fonts, italic and handwritten shapes of many Cyrillic letters (typically lowercase; uppercase only for hand-written or stylish types) are very different from their upright shapes. In certain cases, the correspondence between uppercase and lowercase glyphs does not coincide in Latin and Cyrillic fonts: for example, handwritten Cyrillic m is a possible lowercase counterpart of T instead of M.

As in Latin typography, a sans-serif face may have a mechanically-sloped oblique font (naklonniy shrift—‘sloped’, or ‘slanted font’) instead of italic.

A boldfaced font is called poluzhirniy shrift (‘semi-bold font’), because there existed fully-boldfaced shapes which are out of use since the beginning of the twentieth century.

A bold italic combination (bold slanted) doesn't exist for all font families.

In Serbian and Macedonian, some italic and cursive letters are different from those used in other languages. These letter shapes are often used in upright fonts as well, especially for advertisements, road signs, inscriptions, posters and the like, less so in newspapers or books.

The following table shows the differences between the upright and italic/cursive Cyrillic letters as used in Russian. Italic, and especially cursive glyphs that are bound to confuse beginners are highlighted (confusing either because of an entirely different look, or because of being a false friend with an entirely different Latin character).

| а | б | в | г | д | е | ё | ж | з | и | й | к | л | м | н | о | п | р | с | т | у | ф | х | ц | ч | ш | щ | ъ | ы | ь | э | ю | я |

| а | б | в | Template:Highlight1| г | Template:Highlight1| д | е | ё | ж | з | Template:Highlight1| и | Template:Highlight1| й | к | л | м | н | о | Template:Highlight1| п | р | с | Template:Highlight1| т | у | ф | х | ц | ч | ш | щ | ъ | ы | ь | э | ю | я |

As used in various languages

Sounds are indicated using IPA. These are only approximate indicators. While these languages by and large have phonemic orthographies, there are occasional exceptions—for example, Russian его (yego, ‘him/his’), which is pronounced [jɪˈvo] instead of [jɪˈgo].

Note that transliterated spellings of names may vary, especially y/j/i, but also gh/g/h and zh/j.

See also a more complete list of languages using Cyrillic.

Common letters

The following table lists Cyrillic letters which are used in most national versions of the Cyrillic alphabet. Exceptions and additions for particular languages are noted below.

| Upright | Italic/Cursive | Name | Sound |

|---|---|---|---|

| А а | А а | A | /a/ |

| Б б | Б б | Be | /b/ |

| В в | В в | Ve | /v/ |

| Г г | Г г | Ge | /g/ |

| Д д | Д д | De | /d/ |

| Е е | Е е | Ye | /je/, /ʲe/ |

| Ж ж | Ж ж | Zhe | /ʒ/ |

| З з | З з | Ze | /z/ |

| И и | И и | I | /i/, /ʲi/ |

| Й й | Й й | Short I (Russian: I kratkoye) | /j/ |

| К к | К к | Ka | /k/ |

| Л л | Л л | El | /l/ |

| М м | М м | Em | /m/ |

| Н н | Н н | En | /n/ |

| О о | О о | O | /o/ |

| П п | П п | Pe | /p/ |

| Р р | Р р | Er | /r/ |

| С с | С с | Es | /s/ |

| Т т | Т т | Te | /t/ |

| У у | У у | U | /u/ |

| Ф ф | Ф ф | Ef | /f/ |

| Х х | Х х | Kha | /x/ |

| Ц ц | Ц ц | Tse | /ʦ/ |

| Ч ч | Ч ч | Che | /ʧ/ |

| Ш ш | Ш ш | Sha | /ʃ/ |

| Щ щ | Щ щ | Shcha, Shta | /ʃʧ/, /ʃʲ:/, /ʃt/ |

| Ь ь | Ь ь | Soft sign (Russian: myagkiy znak) or Small yer (Bulgarian: er malak) |

/ʲ/ |

| Ю ю | Ю ю | Yu | /ju/, /ʲu/ |

| Я я | Я я | Ya | /ja/, /ʲa/ |

The soft sign ь is not a letter representing a sound, but modifies the sound of the preceding letter, indicating palatalisation (“softening”), also separates the consonant and the following vowel. Sometimes does not have phonetical meaning, just orthographical (Russian туш, tush /tuʃ/ = ‘flourish after a toast’, тушь, tushʹ /tuʃ/ = ‘india ink’). In some languages, a hard sign ъ or apostrophe ’ just separates consonant and the following vowel (бя /bʲa/, бья /bʲja/, бъя = б’я /bja/).

Slavic languages

Belarusian

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Е е | Ё ё | Ж ж | З з | І і | Й й |

| К к | Л л | М м | Н н | О о | П п | Р р | С с | Т т | У у | Ў ў |

| Ф ф | Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш | Ы ы | Ь ь | Э э | Ю ю | Я я |

The Belarusian alphabet displays the following features:

- Г represents a voiced glottal fricative /ɦ/.

- Yo (Ё ё) /jo/

- I resembles the Latin letter I (І, і).

- U short (Ў, ў) falls between U and Ef. It looks like U (У) with a breve and represents /w/, or like the u part of the diphthong in loud.

- A combination of sh and ch (ШЧ, шч) is used where those familiar only with Russian and or Ukrainian would expect Shcha (Щ, щ).

- Yery (Ы ы) /ɨ/

- E (Э э) /ɛ/

- An apostrophe is used to indicate de-palatalization of the preceding consonant.

- The letter combinations Дж дж and Дз дз appear after Д д in the Belarusian alphabet in some publications. These digraphs each represent a single sound: Дж /ʤ/, Дз /ʣ/.

Bosnian

The Bosnian language uses both Latin and Cyrillic alphabets[3] but Cyrillic is seldom if ever used in today's practice. There was also a Bosnian Cyrillic script (Bosančica) used in the Middle Ages, along with other scripts, although its connection with the Bosnian language, which was only standardised in the 1990s and whose status as a language is still debated, is tenuous at best. The modern Cyrillic used to write the language is the Serbian variant.

Bulgarian

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Е е | Ж ж | З з | И и | Й й | К к |

| Л л | М м | Н н | О о | П п | Р р | С с | Т т | У у | Ф ф | Х х |

| Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш | Щ щ | Ъ ъ | Ь ь | Ю ю | Я я |

The Bulgarian alphabet features:

- (Е) represents /ɛ/ and is called "е" [e].

- (Щ) represents /ʃt/ and is called "щъ" [ʃtə].

- (Ъ) represents the schwa /ə/, and is called "ер голям" [ˈer goˈlʲam] ('big er').

Тhe Bulgarian names for the consonants are [bə], [kə], [lə] etc. with stressed schwa instead of [be], [ka], [el] etc.

Macedonian

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Ѓ ѓ | Е е | Ж ж | З з | Ѕ ѕ | И и |

| Ј ј | К к | Л л | Љ љ | М м | Н н | Њ њ | О о | П п | Р р | С с |

| Т т | Ќ ќ | У у | Ф ф | Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Џ џ | Ш ш |

Macedonian alphabet differs from Serbian in the following ways:

- Between Ze and I is the letter Dze (Ѕ, ѕ), which looks like the Latin letter S and represents /ʣ/.

- Djerv is replaced by Gje (Ѓ, ѓ), which looks like Ghe with an acute accent (´) and represents /ɟ/,

- Tjerv is replaced by Kja (Ќ, ќ), which looks like Ka with an acute accent (´), represents /c/,

Russian

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Е е | Ё ё | Ж ж | З з | И и | Й й |

| К к | Л л | М м | Н н | О о | П п | Р р | С с | Т т | У у | Ф ф |

| Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш | Щ щ | Ъ ъ | Ы ы | Ь ь | Э э | Ю ю | Я я |

- Yo (Ё ё) /jo/

- The Hard Sign¹ (Ъ ъ) indicates no palatalisation²

- Ɨ (Ы ы) /ɨ/

- E (Э э) /ɛ/

Notes:

- In the pre-reform Russian orthography, in Old Russian and in Old Church Slavonic the letter is called yer. Historically, the "hard sign" takes the place of a now-absent vowel, still preserved in Bulgarian. See the notes for Bulgarian.

- When an iotated vowel (vowel whose sound begins with /j/) follows a consonant, the consonant will become palatalised (the /j/ sound will mix with the consonant), and the vowel’s initial /j/ sound will not be heard independently. The Hard Sign will indicate that this does not happen, and the /j/ sound will appear only in front of the vowel. The Soft Sign will indicate that the consonant should be palatised, but the vowel’s /j/ sound will not mix with the palatalization of the consonant. The Soft Sign will also indicate that a consonant before another consonant or at the end of a word is palatised. Examples: та (ta); тя (tʲa); тья (tʲja); тъя (tja); т (t); ть (tʲ).

Historical letters: before 1918, there were four extra letters in use: Іі (replaced by Ии), Ѳѳ (Фита "Fita", replaced by Фф), Ѣѣ (Ять "Yat", replaced by Ее), and Ѵѵ (ижица "Izhitsa", replaced by Ии); these were eliminated by reforms of Russian orthography.

Rusyn

The Rusyn language is spoken by the Lemko Rusyns in Transcarpathian Ukraine, Slovakia, and Poland, and the Pannonian Rusyns in Serbia.

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Ґ ґ | Д д | Е е | Є є | Ё ё* | Ж ж | З з |

| И и | I і* | Ы ы* | Ї ї | Й й | К к | Л л | М м | Н н | О о | П п |

| Р р | С с | Т т | У у | Ф ф | Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш | Щ щ | Ѣ ѣ* |

| Ю ю | Я я | Ь ь | Ъ ъ* |

*Letters absent from Pannonian Rusyn alphabet.

Serbian

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Ђ ђ | Е е | Ж ж | З з | И и | Ј ј |

| К к | Л л | Љ љ | М м | Н н | Њ њ | О о | П п | Р р | С с | Т т |

| Ћ ћ | У у | Ф ф | Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Џ џ | Ш ш |

The Serbian alphabet shows the following features:

- E represents /ɛ/.

- Between Д and E is the letter Dje (Ђ, ђ), which represents /ʥ/, and looks like Tshe, except that the loop of the h curls farther and dips downwards.

- Between И and К is the letter Je (Ј, ј), represents /j/, which looks like the Latin letter J.

- Between Л and М is the letter Lje (Љ, љ), representing /ʎ/, which looks like a ligature of Л and the Soft Sign .

- Between Н and О is the letter Nje (Њ, њ), representing /ɲ/, which looks like a ligature of Н and the Soft Sign.

- Between Т and У is the letter Tshe (Ћ, ћ), representing /ʨ/ and looks like a lowercase Latin letter h with a bar. On the uppercase letter, the bar appears at the top; on the lowercase letter, the bar crosses the top at half of the vertical line.

- Between Ч and Ш is the letter Dzhe (Џ, џ), representing /ʤ/, which looks like Ts but with the downturn moved from the right side of the bottom bar to the middle of the bottom bar.

- Ш is the last letter.

Ukrainian

The Ukrainian alphabet displays the following features:

- Ve represents /ʋ/ (which may be pronounced [w] in a word final position and before consonants).

- He (Г, г) represents a voiced glottal fricative, (/ɦ/).

- Ge (Ґ, ґ) appears after He, represents /g/. It looks like He with an "upturn" pointing up from the right side of the top bar. (This letter was not officially used in the Soviet Union after 1933, so it is missing from older Cyrillic fonts.)

- E (Е, е) represents /ɛ// .

- Ye (Є, є) appears after E, represents /jɛ/.

- Y (И, и) represents /ɪ/.

- I (І, і) appears after Y, represents /i/.

- Yi (Ї, ї) appears after I, represents /ji/.

- Yot (Й, й) represents /j/.

- Shcha (Щ, щ) represents ʃʧ.

- An apostrophe (’) is used to mark de-palatalization of the preceding consonant.

- Like in Belarusian cyrillic, the sounds /ʤ/, /ʣ/ are represented by digraphs Дж and Дз respectively.

- Until reforms in 1990, Soft sign (Ь, ь) appeared at the end of the alphabet, after Ju (Ю, ю) and Ja (Я, я), rather than before them, as in Russian. Many native speakers continue to ignore this reform.

Non-Slavic languages

These alphabets are generally modelled after Russian, but often bear striking differences, particularly when adapted for Caucasian languages. The first few of them were generated by Orthodox missionaries for the Finnic and Turkic peoples of Idel-Ural (Mari, Udmurt, Mordva, Chuvash, Kerashen Tatars) in 1870s. Later such alphabets were created for some of the Siberian and Caucasus peoples who had recently converted to Christianity. In the 1930s, some of those alphabets were switched to the Uniform Turkic Alphabet. All of the peoples of the former Soviet Union who had been using an Arabic or other Asian script (Mongolian script, etc.) also adopted Cyrillic alphabets, and during the Great Purge in late 1930s, all of the Roman‐based alphabets of the peoples of the Soviet Union were switched over to Cyrillic as well (the Baltic Republics were annexed later, and weren't affected by this change). The Abkhazian alphabet was switched to Georgian script, but after the death of Stalin, Abkhaz also adopted Cyrillic. The last language to adopt Cyrillic was the Gagauz language, which had used Greek script before.

In Uzbekistan, Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan, the use of Cyrillic to represent local languages has often been a politically controversial issue since the collapse of the Soviet Union, as it evokes the era of Soviet rule (see Russification). Some of Russia's languages have also tried to drop Cyrillic, but the move was halted under Russian law (see Tatar alphabet). A number of languages have switched from Cyrillic to other orthographies—either Roman‐based or returning to a former script.

Unlike the Roman alphabet, which is usually adapted to different languages by using additions to existing letters such as accents, umlauts, tildes and cedillas, the Cyrillic alphabet is usually adapted by the creation of entirely new letter shapes. In some alphabets invented in the nineteenth century, such as Mari, Udmurt and Chuvash, umlauts and breves also were used.

Bulgarian and Bosnian Sephardim lacking Hebrew typefaces occasionally printed Judeo-Spanish in Cyrillic.[4]

Iranian languages

Ossetian

The Ossetic language has officially used the Cyrillic alphabet since 1937.

| А а | Ӕ ӕ | Б б | В в | Г г | Гъ гъ | Д д | Дж дж |

| Дз дз | Е е | Ё ё | Ж ж | З з | И и | Й й | К к |

| Къ къ | Л л | М м | Н н | О о | П п | Пъ пъ | Р р |

| С с | Т т | Тъ тъ | У у | Ф ф | Х х | Хъ хъ | Ц ц |

| Цъ цъ | Ч ч | Чъ чъ | Ш ш | Щ щ | Ъ ъ | Ы ы | Ь ь |

| Э э | Ю ю | Я я |

Tajik

The Tajik language is written using a Cyrillic-based alphabet.

| А а | Б б | Г г | Д д | Е е | Ё ё | Ж ж | З з | И и | Й й | К к |

| Л л | М м | Н н | О о | П п | Р р | С с | Т т | У у | Ф ф | Х х |

| Ч ч | Ш ш | Ъ ъ | Э э | Ю ю | Я я | Ғ ғ | Ӣ ӣ | Қ қ | Ӯ ӯ | Ҳ ҳ |

| Ҷ ҷ |

Moldovan

The Moldovan language used the Cyrillic alphabet between 1946 and 1989. Nowadays, this alphabet is still official in the unrecognized republic of Transnistria.

Mongolian

The Mongolic languages include Khalkha (in Mongolia), Buryat (around Lake Baikal) and Kalmyk (northwest of the Caspian Sea). Khalkha Mongolian is also written with the Mongol vertical alphabet.

Overview

This table contains all the characters used.

Һһ is shown twice as it appears at two different location in Buryat and Kalmyk

| Khalkha | Аа | Бб | Вв | Гг | Дд | Ее | Ёё | Жж | Зз | Ии | Йй | Кк | Лл | Мм | Нн | Оо | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buryat | Аа | Бб | Вв | Гг | Дд | Ее | Ёё | Жж | Зз | Ии | Йй | Лл | Мм | Нн | Оо | |||||

| Kalmyk | Аа | Әә | Бб | Вв | Гг | Һһ | Дд | Ее | Жж | Җҗ | Зз | Ии | Йй | Кк | Лл | Мм | Нн | Ңң | Оо | |

| Khalkha | Өө | Пп | Рр | Сс | Тт | Уу | Үү | Фф | Хх | Цц | Чч | Шш | Щщ | Ъъ | Ыы | Ьь | Ээ | Юю | Яя | |

| Buryat | Өө | Пп | Рр | Сс | Тт | Уу | Үү | Хх | Һһ | Цц | Чч | Шш | Ыы | Ьь | Ээ | Юю | Яя | |||

| Kalmyk | Өө | Пп | Рр | Сс | Тт | Уу | Үү | Хх | Цц | Чч | Шш | Ьь | Ээ | Юю | Яя |

Khalkha

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Е е | Ё ё | Ж ж | З з | И и | Й й |

| К к | Л л | М м | Н н | О о | Ө ө | П п | Р р | С с | Т т | У у |

| Ү ү | Ф ф | Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш | Щ щ | Ъ ъ | Ы ы | Ь ь | Э э |

| Ю ю | Я я |

- В в = /w/

- Е е = /jɛ/, /jœ/

- Ё ё = /jo/

- Ж ж = /ʤ/

- З з = /ʣ/

- Н н = /n-/, /-ŋ/

- Ө ө = /œ/

- Ү ү = /y/

- Ы ы = /iː/ (after a hard consonant)

- Ь ь = /ĭ/ (extra short)

- Ю ю = /ju/, /jy/

The Cyrillic letters Кк, Фф and Щщ are not used in native Mongolian words, but only for Russian loans.

Buryat

The Buryat (буряад) Cyrillic alphabet is similar to the Khalkha above, but Ьь indicates palatalization as in Russian. Buryat does not use Вв, Кк, Фф, Цц, Чч, Щщ or Ъъ in its native words.

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Е е | Ё ё | Ж ж | З з | И и | Й й |

| Л л | М м | Н н | О о | Ө ө | П п | Р р | С с | Т т | У у | Ү ү |

| Х х | Һ һ | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш | Ы ы | Ь ь | Э э | Ю ю | Я я |

- Е е = /jɛ/, /jœ/

- Ё ё = /jo/

- Ж ж = /ʤ/

- Н н = /n-/, /-ŋ/

- Ө ө = /œ/

- Ү ү = /y/

- Һ һ = /h/

- Ы ы = /ei/, /iː/

- Ю ю = /ju/, /jy/

Kalmyk

The Kalmyk (хальмг) Cyrillic alphabet is similar to the Khalkha, but the letters Ээ, Юю and Яя appear only word-initially. In Kalmyk, long vowels are written double in the first syllable (нөөрин), but single in syllables after the first. Short vowels are omitted altogether in syllables after the first syllable (хальмг = /xaʎmag/).

| А а | Ә ә | Б б | В в | Г г | Һ һ | Д д | Е е | Ж ж | Җ җ | З з |

| И и | Й й | К к | Л л | М м | Н н | Ң ң | О о | Ө ө | П п | Р р |

| С с | Т т | У у | Ү ү | Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш | Ь ь | Э э | Ю ю |

| Я я |

- Ә ә = /æ/

- В в = /w/

- Һ һ = /ɣ/

- Е е = /ɛ/, /jɛ-/

- Җ җ = /ʤ/

- Ң ң = /ŋ/

- Ө ө = /œ/

- Ү ү = /y/

Northwest Caucasian languages

Living Northwest Caucasian languages are generally written using adaptations of the Cyrillic alphabet.

Abkhaz

Abkhaz is a Caucasian language, spoken in the Autonomous Republic of Abkhazia, Georgia.

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Гь гь | Ҕ ҕ | Ҕь ҕь | Д д | Дә дә | Џ џ | Џь џь |

| Е е | Ҽ ҽ | Ҿ ҿ | Ж ж | Жь жь | Жә жә | З з | Ӡ ӡ | Ӡә ӡә | И и | Й й |

| К к | Кь кь | Қ қ | Қь қь | Ҟ ҟ | Ҟь ҟь | Л л | М м | Н н | О о | Ҩ ҩ |

| П п | Ҧ ҧ | Р р | С с | Т т | Тә тә | Ҭ ҭ | Ҭә ҭә | У у | Ф ф | Х х |

| Хь хь | Ҳ ҳ | Ҳә ҳә | Ц ц | Цә цә | Ҵ ҵ | Ҵә ҵә | Ч ч | Ҷ ҷ | Ш ш | Шь шь |

| Шә шә | Щ щ | Ы ы |

Turkic languages

Azerbaijani

The Cyrillic alphabet was used for the Azerbaijani language from 1939 to 1991.

Bashkir

The Cyrillic alphabet was used for the Bashkir language after the winter of 1938.

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Ғ ғ | Д д | Ҙ ҙ | Е е | Ё ё | Ж ж | З з | |

| И и | Й й | К к | Ҡ ҡ | Л л | М м | Н н | Ң ң | О о | Ө ө | П п | |

| Р р | С с | Ҫ ҫ | Т т | У у | Ү ү | Ф ф | Х х | Һ һ | Ц ц | Ч ч | |

| Ш ш | Щ щ | Ъ ъ | Ы ы | Ь ь | Э э | Ә ә | Ю ю | Я я |

Chuvash

The Cyrillic alphabet is used for the Chuvash language since the late 19th century, with some changes in 1938.

| А а | Ӑ ӑ | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Е е | Ё ё | Ӗ ӗ | Ж ж | З з |

| И и | Й й | К к | Л л | М м | Н н | О о | П п | Р р | С с | Ҫ ҫ |

| Т т | У у | Ӳ ӳ | Ф ф | Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш | Щ щ | Ъ ъ | Ы ы |

| Ь ь | Э э | Ю ю | Я я |

Kazakh

Kazakh is also written with the Latin alphabet (in Turkey, but not in Kazakhstan), and modified Arabic alphabet (in the People's Republic of China, Iran and Afghanistan).

| А а | Ә ә | Б б | В в | Г г | Ғ ғ | Д д | Е е | Ё ё | Ж ж | З з |

| И и | Й й | К к | Қ қ | Л л | М м | Н н | Ң ң | О о | Ө ө | П п |

| Р р | С с | Т т | У у | Ұ ұ | Ү ү | Ф ф | Х х | Һ һ | Ц ц | Ч ч |

| Ш ш | Щ щ | Ъ ъ | Ы ы | İ і | Ь ь | Э э | Ю ю | Я я |

- Ә ә = /æ/

- Ғ ғ = /ʁ/ (voiced uvular fricative)

- Қ қ = /q/ (voiceless uvular plosive)

- Ң ң = /ŋ/

- Ө ө = /œ/

- У у = /uw/, /yw/,/w/

- Ұ ұ = /u/

- Ү ү = /y/

- Һ һ = /h/

- İ і = /i/

The Cyrillic letters Вв, Ёё, Цц, Чч, Щщ, Ъъ, Ьь and Ээ are not used in native Kazakh words, but only for Russian loans.

Kyrgyz

Kyrgyz has also been written in Latin and in Arabic.

| А а | Б б | Г г | Д д | Е е | Ё ё | Ж ж | З з | И и | Й й | К к |

| Л л | М м | Н н | Ң ң | О о | Ө ө | П п | Р р | С с | Т т | У у |

| Ү ү | Х х | Ч ч | Ш ш | Ы ы | Э э | Ю ю | Я я |

- Ң ң = /ŋ/ (velar nasal)

- Ү ү = /y/ (close front rounded vowel)

- Ө ө = /œ/ (open-mid front rounded vowel)

Tatar

Tatar has used Cyrillic since 1939, but the Russian Orthodox Tatar community has used Cyrillic since the 19th century. In 2000 a new Latin alphabet was adopted for Tatar, but it is used generally in the Internet.

Uzbek

The Cyrillic alphabet is still used most often for the Uzbek language, although the government has adopted a version of the Latin alphabet to replace it. The deadline for making this transition has however been repeatedly changed. The latest deadline was supposed to be 2005, but was shifted once again a few more years. Some scholars are not convinced that the transition will be made at all.

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Е е | Ё ё | Ж ж | З з | И и | Й й | К к |

| Л л | М м | Н н | О о | П п | Р р | С с | Т т | У у | Ф ф | Х х | Ч ч |

| Ш ш | Ъ ъ | Э э | Ю ю | Я я | Ў ў | Қ қ | Ғ ғ | Ҳ ҳ |

- В в = /w/

- Ж ж = /ʤ/

- Ф ф = /ɸ/

- Х х = /χ/

- Ъ ъ = /ʔ/

- Ў ў = /ø/

- Қ қ = /q/

- Ғ ғ = /ʁ/

- Ҳ ҳ = /h/

Derived alphabets

The first alphabet partly derived from Cyrillic is Abur, applied to the Komi language. Other writing systems derived from Cyrillic were applied to Caucasian languages and the Molodtsov alphabet for Komi language.

Relationship to other writing systems

Latin alphabets

A number of languages written in the Cyrillic alphabet have also been written in the Latin alphabet.

The old Belarusian Latin alphabet (Łacinka) is based on Polish orthography, but, because of the political realities in the former USSR, Belarusian is usually romanized by analogy to Russian.

Serbian is written in both Cyrillic and Latin alphabets. In Serbian there is a one-to-one correspondence between Vuk Karadžić's Serbian Cyrillic and Ljudevit Gaj's Croatian Gajica (derived from the Czech alphabet. See Serbo-Croatian writing systems.)

There are also Latin alphabets for some non-Slavic languages, such as Azerbaijani, Uzbek or Moldavian. After the disintegration of the Soviet Union in 1991, official status shifted from Cyrillic to Latin. The transition is complete in most of Moldova, but Azerbaijan and Uzbekistan still use both systems.

Romanization

There are various systems for romanization of Cyrillic text, including transliteration to convey Cyrillic spelling in Latin characters, and transcription to convey pronunciation.

Standard Cyrillic-to-Latin transliteration systems include:

- Scientific transliteration, used in linguistics, is based on the Latin Croatian alphabet.

- The Working Group on Romanization Systems of the United Nations recommends different systems for specific languages. These are the most commonly used around the world.

- ISO 9:1995, from the International Organization for Standardization.

- American Library Association and Library of Congress Romanization tables for Slavic alphabets (ALA-LC Romanization), used in North American libraries.

- BGN/PCGN romanization (1947), United States Board on Geographic Names & Permanent Committee on Geographical Names for British Official Use).

- GOST 16876, a now defunct Soviet transliteration standard. Replaced by GOST 7.79, which is ISO 9 equivalent.

- Volapuk encoding, an informal rendering of Cyrillic text over Latin-alphabet ASCII.

See also romanization of Belarusian, Bulgarian, Kyrgyz, Russian, and Ukrainian.

Cyrillization

Representing other writing systems with Cyrillic letters is called Cyrillization.

Computer encoding

| Cyrillic[1] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+040x | Ѐ | Ё | Ђ | Ѓ | Є | Ѕ | І | Ї | Ј | Љ | Њ | Ћ | Ќ | Ѝ | Ў | Џ |

| U+041x | А | Б | В | Г | Д | Е | Ж | З | И | Й | К | Л | М | Н | О | П |

| U+042x | Р | С | Т | У | Ф | Х | Ц | Ч | Ш | Щ | Ъ | Ы | Ь | Э | Ю | Я |

| U+043x | а | б | в | г | д | е | ж | з | и | й | к | л | м | н | о | п |

| U+044x | р | с | т | у | ф | х | ц | ч | ш | щ | ъ | ы | ь | э | ю | я |

| U+045x | ѐ | ё | ђ | ѓ | є | ѕ | і | ї | ј | љ | њ | ћ | ќ | ѝ | ў | џ |

| U+046x | Ѡ | ѡ | Ѣ | ѣ | Ѥ | ѥ | Ѧ | ѧ | Ѩ | ѩ | Ѫ | ѫ | Ѭ | ѭ | Ѯ | ѯ |

| U+047x | Ѱ | ѱ | Ѳ | ѳ | Ѵ | ѵ | Ѷ | ѷ | Ѹ | ѹ | Ѻ | ѻ | Ѽ | ѽ | Ѿ | ѿ |

| U+048x | Ҁ | ҁ | ҂ | ◌҃ | ◌҄ | ◌҅ | ◌҆ | ◌҇ | ◌҈ | ◌҉ | Ҋ | ҋ | Ҍ | ҍ | Ҏ | ҏ |

| U+049x | Ґ | ґ | Ғ | ғ | Ҕ | ҕ | Җ | җ | Ҙ | ҙ | Қ | қ | Ҝ | ҝ | Ҟ | ҟ |

| U+04Ax | Ҡ | ҡ | Ң | ң | Ҥ | ҥ | Ҧ | ҧ | Ҩ | ҩ | Ҫ | ҫ | Ҭ | ҭ | Ү | ү |

| U+04Bx | Ұ | ұ | Ҳ | ҳ | Ҵ | ҵ | Ҷ | ҷ | Ҹ | ҹ | Һ | һ | Ҽ | ҽ | Ҿ | ҿ |

| U+04Cx | Ӏ | Ӂ | ӂ | Ӄ | ӄ | Ӆ | ӆ | Ӈ | ӈ | Ӊ | ӊ | Ӌ | ӌ | Ӎ | ӎ | ӏ |

| U+04Dx | Ӑ | ӑ | Ӓ | ӓ | Ӕ | ӕ | Ӗ | ӗ | Ә | ә | Ӛ | ӛ | Ӝ | ӝ | Ӟ | ӟ |

| U+04Ex | Ӡ | ӡ | Ӣ | ӣ | Ӥ | ӥ | Ӧ | ӧ | Ө | ө | Ӫ | ӫ | Ӭ | ӭ | Ӯ | ӯ |

| U+04Fx | Ӱ | ӱ | Ӳ | ӳ | Ӵ | ӵ | Ӷ | ӷ | Ӹ | ӹ | Ӻ | ӻ | Ӽ | ӽ | Ӿ | ӿ |

Notes

| ||||||||||||||||

In Unicode, the Cyrillic block extends from U+0400 to U+052F. The characters in the range U+0400 to U+045F are basically the characters from ISO 8859-5 moved upward by 864 positions. The characters in the range U+0460 to U+0489 are historic letters, not used now. The characters in the range U+048A to U+052F are additional letters for various languages that are written with Cyrillic script.

Unicode does not include accented Cyrillic letters, but they can be combined by adding U+0301 ("combining acute accent") after the accented vowel (e.g., ы́ э́ ю́ я́). Some languages, including modern Church Slavonic, are still not fully supported.

Punctuation for Cyrillic text is similar to that used in European Latin-alphabet languages.

Other character encoding systems for Cyrillic:

- CP866 – 8-bit Cyrillic character encoding established by Microsoft for use in MS-DOS also known as GOST-alternative

- ISO/IEC 8859-5 – 8-bit Cyrillic character encoding established by International Organization for Standardization

- KOI8-R – 8-bit native Russian character encoding

- KOI8-U – KOI8-R with addition of Ukrainian letters

- MIK – 8-bit native Bulgarian character encoding for use in DOS

- Windows-1251 – 8-bit Cyrillic character encoding established by Microsoft for use in Microsoft Windows. Former standard encoding in some Linux distributions for Belarusian and Bulgarian, but currently displaced by UTF-8.

- GOST-main

- GB 2312 - Principally simplified Chinese encodings, but there are also basic 33 Russian Cyrillic letters (in upper- and lower-case).

- JIS and Shift JIS - Principally Japanese encodings, but there are also basic 33 Russian Cyrillic letters (in upper- and lower-case).

Keyboard layouts

Each language has its own standard keyboard layout, adopted from typewriters. With the flexibility of computer input methods, there are also transliterating or homophonic keyboard layouts made for typists who are more familiar with other layouts, like the common English qwerty keyboard. When practical Cyrillic keyboard layouts or fonts are not available, computer users sometimes use transliteration or look-alike "volapuk" encoding to type languages which are normally written with the Cyrillic alphabet.

See Keyboard layouts for non-Roman alphabetic scripts.

Notes

- ^ Bringhurst (2002) writes "in Cyrillic, the difference between normal lower case and small caps is more subtle than it is in the Latin or Greek alphabets,..." (p 32) and "in most Cyrillic faces, the lower case is close in color and shape to Latin small caps" (p 107).

- ^ Name ital'yanskiy shrift (Italian font) in Russian refers to a particular font family [1], whereas rimskiy shrift (roman font) is just a synonym for Latin font, Latin alphabet.

- ^ Senahid Halilović, Pravopis bosanskog jezika

- ^ Šmid (2002), pp. 113–24: "Es interesante el hecho que en Bulgaria se imprimieron unas pocas publicaciones en alfabeto cirílico búlgaro y en Grecia en alfabeto griego… Nezirović (1992: 128) anota que también en Bosnia se ha encontrado un documento en que la lengua sefardí está escrita en alfabeto cirilico." Translation: "It is an interesting fact that in Bulgaria a few [Sephardic] publications are printed in the Bulgarian Cyrillic alphabet and in Greece in the Greek alphabet… Nezirović (1992:128) writes that in Bosnia a document has also been found in which the Sephardic language is written in the Cyrillic alphabet."

References

- Bringhurst, Robert (2002). The Elements of Typographic Style (version 2.5), pp. 262–264. Vancouver, Hartley & Marks. ISBN 0-88179-133-4.

- Nezirović, M. (1992). Jevrejsko-španjolska književnost. Sarajevo: Svjetlost. [cited in Šmid, 2002]

- Šmid, Katja (2002). "Template:PDFlink", in Verba Hispanica, vol X. Liubliana: Facultad de Filosofía y Letras de la Universidad de Liubliana. ISSN 0353-9660.

See also

- Languages using Cyrillic

- List of Cyrillic letters

- Faux Cyrillic, real or fake Cyrillic letters used to give Latin-alphabet text a Soviet or Russian feel

- Russian Manual Alphabet (the fingerspelled Cyrillic alphabet)

- Cyrillic Alphabet Day

- Vladislav the Grammarian

External links

- Cyrillic alphabet at omniglot.com

- Minority Languages of Russia on the Net, a list of resources.

- Information on Cyrillic transliteration and the handwritten script form of Cyrillic.

- A Survey of the Use of Modern Cyrillic Script, including the complete required repertoire of graphic characters, by J. W. van Wingen.

- Tipometar: Serbian Cyrillic typography and typefaces

- The Cyrillic Charset Soup, Roman Czyborra’s overview and history of Cyrillic charsets.

- Template:PDFlink

- Template:PDFlink

- Transliteration of Non-Roman Scripts, a collection of writing systems and transliteration tables, by Thomas T. Pedersen. Includes PDF reference charts for many languages' transliteration systems.

| Letters of the Cyrillic alphabet | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| А A |

Б Be |

В Ve |

Г Ge |

Ґ Ge upturn |

Д De |

Ђ Dje |

Ѓ Gje |

Е Ye |

Ё Yo |

Є Ye |

| Ж Zhe |

З Ze |

Ѕ Dze |

И I |

І Dotted I |

Ї Yi |

Й Short I |

Ј Je |

К Ka |

Л El |

Љ Lje |

| М Em |

Н En |

Њ Nje |

О O |

П Pe |

Р Er |

С Es |

Т Te |

Ћ Tshe |

Ќ Kje |

У U |

| Ў Short U |

Ф Ef |

Х Kha |

Ц Tse |

Ч Che |

Џ Dzhe |

Ш Sha |

Щ Shcha |

Ъ Hard sign (Yer) |

Ы Yery |

Ь Soft sign (Yeri) |

| Э E |

Ю Yu |

Я Ya |

||||||||

| Cyrillic Non-Slavic Letters | ||||||||||

| Ӏ Palochka |

Ә Cyrillic Schwa |

Ғ Ayn |

Ҙ Dhe |

Ҡ Bashkir Qa |

Қ Qaf |

Ң Ng |

Ө Barred O |

Ү Straight U |

Ұ Straight U with stroke |

Һ He |

| Cyrillic Archaic Letters | ||||||||||

| ІА A iotified |

Ѥ E iotified |

Ѧ Yus small |

Ѫ Yus big |

Ѩ Yus small iotified |

Ѭ Yus big iotified |

Ѯ Ksi |

Ѱ Psi |

Ѳ Fita |

Ѵ Izhitsa |

Ѷ Izhitsa okovy |

| Ҁ Koppa |

Ѹ Uk |

Ѡ Omega |

Ѿ Ot |

Ѣ Yat |

||||||