Slovakia

Slovak Republic Slovenská republika | |

|---|---|

| Anthem: Nad Tatrou sa blýska "Lightning over the Tatras" | |

![Location of Slovakia (orange) – in Europe (tan & white) – in the European Union (tan) [Legend]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f0/EU_location_SVK.png/250px-EU_location_SVK.png) Location of Slovakia (orange) – in Europe (tan & white) | |

| Capital and largest city | Bratislava |

| Official languages | Slovak |

| Ethnic groups | 85.8% Slovaks,

9.7% Hungarians, 1.7% Roma, 2.8% other minority groups |

| Demonym(s) | Slovak |

| Government | Parliamentary republic |

| Ivan Gašparovič | |

| Robert Fico | |

| Pavol Paška | |

| Independence Peaceful dissolution of Czechoslovakia | |

• Date | January 1, 19931 |

| Area | |

• Total | 49,035 km2 (18,933 sq mi) (130th) |

• Water (%) | negligible |

| Population | |

• 2001 census | 5,379,455 (109th) |

• Density | 111/km2 (287.5/sq mi) (88th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2008 estimate |

• Total | $109.677 billion[1] (59th) |

• Per capita | $22,241,[1] (41st) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2008 estimate |

• Total | $74.988 billion[1] (60th) |

• Per capita | $18,584[1] (42nd) |

| HDI (2004) | Error: Invalid HDI value (42nd) |

| Currency | Euro (€)2 (EUR2) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Drives on | right |

| Calling code | +4214 |

| ISO 3166 code | SK |

| Internet TLD | .sk3 |

1 Czechoslovakia split into the Czech Republic and Slovakia; see Velvet Divorce. 2 Before 2009: Slovak Koruna 3 Also .eu, shared with other European Union member states. 4 Shared code 42 with Czech Republic until 1997. | |

Slovakia (long form: Slovak Republic; Slovak: , long form , is a landlocked country in Central and Danubian Europe with a population of over five million and an area of about 49,000 square kilometres (almost 19,000 square miles). The Slovak Republic borders the Czech Republic and Austria to the west, Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east and Hungary to the south. The largest city is its capital, Bratislava. Slovakia is a member state of the European Union, NATO, UN, OECD, WTO, UNESCO and other international organizations.

The Slavic people arrived in the territory of present day Slovakia between the 5th and 6th centuries AD during the Migration Period. In the course of history, various parts of Slovakia belonged to Samo's Empire (the first known political unit of Slavs), Great Moravia, the Kingdom of Hungary, Habsburg (Austrian) monarchy, Austria-Hungary and Czechoslovakia. The present-day Slovak Republic became an independent state on January 1, 1993 with the peaceful division of Czechoslovakia in the Velvet Divorce; it was, with the Czech Republic, the last European country to gain independence in the 20th century.

Slovakia is a high-income economy[3] with one of the fastest growth rates in the EU and OECD. It joined the European Union in 2004 and joined the Eurozone on the 1st of January, 2009.

History

Before the fifth century

From around 500 BC, the territory of modern-day Slovakia was settled by Celts, who built powerful oppida on the sites of modern-day Bratislava and Havránok. Biatecs, silver coins with the names of Celtic Kings, represent the first known use of writing in Slovakia. From 2 AD, the expanding Roman Empire established and maintained a series of outposts around and just north of the Danube, the largest of which were known as Carnuntum (whose remains are on the main road halfway between Vienna and Bratislava) and Brigetio (present-day Szöny at the Slovak-Hungarian border). Near the northernmost line of the Roman hinterlands, the Limes Romanus, there existed the winter camp of Laugaricio (modern-day Trenčín) where the Auxiliary of Legion II fought and prevailed in a decisive battle over the Germanic Quadi tribe in 179 AD during the Marcomannic Wars. The Kingdom of Vannius, a barbarian kingdom founded by the Germanic Suebian tribes of Quadi and Marcomanni, as well as several small Germanic and Celtic tribes, including the Osi and Cotini, existed in Western and Central Slovakia from 8–6 BC to 179 AD.

Slavic states

The Slavic tribes settled in the territory of Slovakia in the 6th century during Avar rule. Western Slovakia was the centre of Samo's Empire in the 7th century. A Slavic state known as the Principality of Nitra arose in the 8th century and its ruler Pribina had the first known Christian church in Slovakia consecrated by 828. Together with neighboring Moravia, the principality formed the core of the Great Moravian Empire from 833. The high point of this Slavonic empire came with the arrival of Saints Cyril and Methodius in 863, during the reign of Prince Rastislav, and the territorial expansion under King Svätopluk I.

The era of Great Moravia

Great Moravia arose around 830 when Moimír I unified the Slavic tribes settled north of the Danube and extended the Moravian supremacy over them.[4] When Mojmír I endeavoured to secede from the supremacy of the king of East Francia in 846, King Louis the German deposed him and assisted Moimír's nephew, Rastislav (846–870) in acquiring the throne.[5] The new monarch pursued an independent policy: after stopping a Frankish attack in 855, he also sought to weaken influence of Frankish priests preaching in his realm. Rastislav asked the Byzantine Emperor Michael III to send teachers who would interpret Christianity in the Slavic vernacular. Upon Rastislav's request, two brothers, Byzantine officials and missionaries Saints Cyril and Methodius came in 863. Cyril developed the first Slavic alphabet and translated the Gospel into the Old Church Slavonic language. Rastislav was also preoccupied with the security and administration of his state. Numerous fortified castles built throughout the country are dated to his reign and some of them (e.g., Dowina, sometimes identified with Devín Castle)[6][7] are also mentioned in connection with Rastislav by Frankish chronicles.[8] [5]

During Rastislav's reign, the Principality of Nitra was given to his nephew Svatopluk as an appanage.[7] The rebellious prince allied himself with the Franks and overthrew his uncle in 870. Similarly to his predecessor, Svatopluk I (871–894) assumed the title of the king (rex). During his reign, the Great Moravian Empire reached its greatest territorial extent, when not only present-day Moravia and Slovakia but also present-day northern and central Hungary, Lower Austria, Bohemia, Silesia, Lusatia, southern Poland and northern Serbia belonged to the empire, but the exact borders of his domains are still disputed by modern authors.[4] [9] Svatopluk also withstood attacks of the nomadic Magyar tribes and the Bulgarian Empire, although sometimes it was he who hired the Magyars when waging war against East Francia.[10]

In 880, Pope John VIII set up an independent ecclesiastical province in Great Moravia with Archbishop Methodius as its head. He also named the German cleric Wiching the Bishop of Nitra.

After the death of King Svatopluk in 894, his sons Mojmír II (894-906?) and Svatopluk II succeeded him as the King of Great Moravia and the Prince of Nitra respectively.[7] However, they started to quarrel for domination of the whole empire. Weakened by an internal conflict as well as by constant warfare with Eastern Francia, Great Moravia lost most of its peripheral territories.

In the meantime, the Magyar tribes, having suffered a catastrophic defeat from the similarly nomadic Pechenegs, left their territories east of the Carpathian Mountains, invaded the Carpathian Basin and started to occupy the territory gradually around 896.[9] Their armies' advance may have been promoted by continuous wars among the countries of the region whose rulers still hired them occasionally to intervene in their struggles.[11]

Both Mojmír II and Svatopluk II probably died in battles with the Magyars between 904 and 907 because their names are not mentioned in written sources after 906. In three battles (July 4-5 and August 9, 907) near Bratislava, the Magyars routed Bavarian armies. Historians traditionally put this year as the date of the breakup of the Great Moravian Empire.

Great Moravia left behind a lasting legacy in Central and Eastern Europe. The Glagolitic script and its successor Cyrillic were disseminated to other Slavic countries, charting a new path in their cultural development. The administrative system of Great Moravia may have influenced the development of the administration of the Kingdom of Hungary.

Kingdom of Hungary

Following the disintegration of the Great Moravian Empire in the early 10th century, the Hungarians gradually annexed the territory of the present-day Slovakia. In the late 10th century, south-western territories of the present-day Slovakia became part of the arising Hungarian principality, which transformed into the Kingdom of Hungary after 1000. The territory became integral part of the Hungarian State until 1918. The ethnic composition became more diverse with the arrival of the Carpathian Germans in the 13th century, the Vlachs in the 14th century and the Jews.

A huge population loss resulted from the invasion of the Mongols in 1241 and the subsequent famine. However, in medieval times the area of the present-day Slovakia was characterized rather by burgeoning towns, construction of numerous stone castles, and the development of art.[12] In 1465, the Hungarian King Matthias Corvinus founded the Hungarian Kingdom's first university, in Bratislava (then Pressburg or Pozsony), but it was closed in 1490 after his death.[13]

After the Ottoman Empire started its expansion into Hungary and the occupation of Buda in the early 16th century, the centre of the Kingdom of Hungary (under the name of Royal Hungary) shifted towards Bratislava, which became the capital city of the Royal Hungary in 1536. But the Ottoman wars and frequent insurrections against the Habsburg Monarchy also inflicted a great deal of destruction, especially in rural areas. As the Turks withdrew from Hungary in the late 17th century, the importance of the territory of today's Slovakia within the kingdom decreased, although Bratislava retained its position as the capital city of Hungary until 1848, when the capital moved to Buda.

During the revolution in 1848-49 the Slovaks supported the Austrian Emperor with the ambition to secede from the Hungarian part of the Austrian monarchy, but they failed to achieve this aim.[citation needed] Thereafter the relations between the nationalities deteriorated (see Magyarization), resulting in the secession of Slovakia from Hungary after World War I. About 69,000 Slovak soldiers were killed in World War I.[14]

Czechoslovakia and World War II

In 1918, Slovakia and the regions of Bohemia and Moravia formed a common state, Czechoslovakia, with the borders confirmed by the Treaty of Saint Germain and Treaty of Trianon. In 1919, during the chaos following the breakup of Austria-Hungary, Slovakia was attacked by the provisional Hungarian Soviet Republic and one-third of Slovakia for three weeks became the Slovak Soviet Republic.

During the inter-war period, democratic and prosperous Czechoslovakia was under continuous pressure from the revisionist governments of Germany and Hungary, leading to a partial dismemberment on September 30, 1938 as a result of the Munich Agreement. The remainder of "rump" Czechoslovakia was renamed Czecho-Slovakia and included a greater degree of Slovak political autonomy. Southern Slovakia, however, would be lost to Hungary due to the First Vienna Award.

After Nazi Germany threatened to annex part of Slovakia and to allow the remaining regions to be partitioned by Hungary and Poland, Slovakia chose to maintain its national and territorial integrity, seceding from Czecho-Slovakia in March 1939 and allying itself, as demanded by Germany, with Hitler's coalition.[15] The government of the First Slovak Republic, led by Jozef Tiso and Vojtech Tuka, was strongly influenced by Germany and gradually became a puppet regime in many respects. Most Jews were deported from the country and taken to Nazi concentration camps during the Holocaust; thousands of Jews, however, remained to labor in Slovak work camps in Sered, Vyhne, and Nováky.[16] Tiso, through the granting of presidential exceptions, has been credited with saving as many as 40,000 Jews during the war, although other estimates place the figure closer to 4,000 or even 1,000.[17] An anti-Nazi resistance movement launched a fierce armed insurrection, known as the Slovak National Uprising, in 1944. A bloody German occupation and a guerilla war followed.

Rule of the Communist party

After World War II, Czechoslovakia was reconstituted and Jozef Tiso was hanged in 1947 for collaboration with the Nazis. More than 76,000 Hungarians[18] and 32,000 Germans[19] were forced to leave Slovakia, in a series of population transfers initiated by the Allies at the Potsdam Conference.[20] This expulsion is still a source of tension between Slovakia and Hungary.[citation needed]

Czechoslovakia came under the influence of the Soviet Union and its Warsaw Pact after a coup in 1948. The country was occupied by the Warsaw Pact forces in 1968, ending a period of liberalization under the leadership of Alexander Dubček. In 1969, Czechoslovakia became a federation of the Czech Socialist Republic and the Slovak Socialist Republic.

Establishment of the Slovak Republic

The end of Communist rule in Czechoslovakia in 1989, during the peaceful Velvet Revolution, was followed once again by the country's dissolution, this time into two successor states. In July 1992 Slovakia, led by Prime Minister Vladimír Mečiar, declared itself a sovereign state, meaning that its laws took precedence over those of the federal government. Throughout the Autumn of 1992, Mečiar and Czech Prime Minister Václav Klaus negotiated the details for disbanding the federation. In November the federal parliament voted to dissolve the country officially on December 31, 1992. Slovakia and the Czech Republic went their separate ways after January 1, 1993, an event sometimes called the Velvet Divorce. Slovakia has remained a close partner with the Czech Republic, both countries cooperate with Hungary and Poland in the Visegrád Group. Slovakia became a member of NATO on March 29, 2004 and of the European Union on May 1, 2004. On January 1st, 2009, Slovakia adopted the Euro as its national currency.

Geography

The Slovak landscape is noted primarily for its mountainous nature, with the Carpathian Mountains extending across most of the northern half of the country. Amongst these mountain ranges are the high peaks of the Tatra mountains.[2] To the north, close to the Polish border, are the High Tatras which are a popular skiing destination and home to many scenic lakes and valleys as well as the highest point in Slovakia, the Gerlachovský štít at 2,655 metres (8,711 ft), and the country's highly symbolic mountain Kriváň.

Major Slovak rivers are the Danube, the Váh and the Hron. Tisa marks Slovak-Hungarian border at only 5 km.

The Slovak climate lies between the temperate and continental climate zones with relatively warm summers and cold, cloudy and humid winters. The area of Slovakia can be divided into three kinds of climatic zones and the first zone can be divided into two sub-zones.

Climate of lowlands

Dominance of oceanic influences

The average annual temperature is about 9–10 °C. The average temperature of the hottest month is about 20 °C and the average temperature of the coldest month is greater than −3 °C. This kind of climate occurs at Záhorská nížina and Podunajská nížina. It is the typical climate of the capital city Bratislava.[21]

Climate of lowlands with dominance of continental influences

The average annual temperature is about 8–9 °C. The average temperature of the hottest month is about 19 °C and the average temperature of the coldest month is less than −3 °C. This kind of climate can be found at Košická kotlina and Východoslovenská nížina. It is the typical climate of the city of Košice.[22]

Climate of basins

The average annual temperature is between 5 °C and 8.5 °C. The average temperature of the hottest month is between 15 °C and 18.5 °C and the average temperature of the coldest month is between −3 °C and −6 °C. This climate can be found in almost all basins in Slovakia. For example Podtatranská kotlina, Žilinská kotlina, Turčianska kotlina, Zvolenská kotlina. It is the typical climate for the towns of Poprad[23] and Sliač.[24]

Mountain climate

The average annual temperature is less than 5 °C. The average temperature of the hottest month is less than 15 °C and the average temperature of the coldest month is less than −5 °C. This kind of climate occurs in mountains and in some villages in the valleys of Orava and Spiš.

Demographics

The majority of the inhabitants of Slovakia are ethnically Slovak (85.8%). Hungarians are the largest ethnic minority (9.7%). Other ethnic groups, as of the 2001 census, include Roma with 1.7%,[25] Ruthenians or Ukrainians with 1%, and other or unspecified, 1.8%.[2] Unofficial estimates on the number of Roma population are much higher, around 9%.[26]

The official state language is Slovak, a member of the Slavic Language Family, but Hungarian is also widely spoken in the south of the country and enjoys a co-official status in some municipalities, and many people also speak Czech.

The Slovak constitution guarantees freedom of religion. The majority of Slovak citizens (68.9 %) identify themselves with Roman Catholicism (although church attendance is much lower); the second-largest group are people without confession (13%). About 6.93% belong to Lutheranism, 4.1% are Greek Catholic, affiliated with the Roman Catholic Church, Calvinism has 2.0%, other and non-registered churches 1.1% and some (0.9%) are Eastern Orthodox. About 2,300 Jews remain of the large estimated pre-WWII population of 90,000.[27]

In 2007 Slovakia was estimated to have a fertility rate of 1.33.[2] (i.e., the average woman will have 1.33 children in her lifetime), which is one of the lowest numbers among EU countries.

Politics

Slovakia is a parliamentary democratic republic with a multi-party system. The last parliamentary elections were held on June 17, 2006 and two rounds of presidential elections took place on April 3, 2004 and April 17, 2004.

The Slovak head of state is the president (Ivan Gašparovič, 2004 - 2009), elected by direct popular vote for a five-year term. Most executive power lies with the head of government, the prime minister (Robert Fico, 2006 - 2010), who is usually the leader of the winning party, but he/she needs to form a majority coalition in the parliament. The prime minister is appointed by the president. The remainder of the cabinet is appointed by the president on the recommendation of the prime minister.

Slovakia's highest legislative body is the 150-seat unicameral National Council of the Slovak Republic (Národná rada Slovenskej republiky). Delegates are elected for a four-year term on the basis of proportional representation. Slovakia's highest judicial body is the Constitutional Court of Slovakia (Ústavný súd), which rules on constitutional issues. The 13 members of this court are appointed by the president from a slate of candidates nominated by parliament.

Slovakia has been a member state of the European Union and NATO since 2004. As a member of the United Nations (since 1993), Slovakia was, on October 10, 2005, elected to a two-year term on the UN Security Council from 2006 to 2007. Slovakia is also a member of WTO, OECD, OSCE, and other international organizations.

Controversially, the Beneš Decrees, by which, after World War II, the German and Hungarian populations of Czechoslovakia were decreed collectively guilty of World War II, stripped of their citizenship, and many deported, have still not been repealed.

Regions and districts

As for administrative division, Slovakia is subdivided into 8 kraje (singular - kraj, usually translated as "region", but actual meaning is "county"), each of which is named after its principal city. Regions have enjoyed a certain degree of autonomy since 2002. Their self-governing bodies are referred to as Self-governing (or autonomous) Regions (sg. samosprávny kraj, pl. samosprávne kraje) or Upper-Tier Territorial Units (sg. vyšší územný celok, pl. vyššie územné celky, abbr. VÚC).

- Bratislava Region (Bratislavský kraj) (capital Bratislava)

- Trnava Region (Trnavský kraj) (capital Trnava)

- Trenčín Region (Trenčiansky kraj) (capital Trenčín)

- Nitra Region (Nitriansky kraj) (capital Nitra)

- Žilina Region (Žilinský kraj) (capital Žilina)

- Banská Bystrica Region (Banskobystrický kraj) (capital Banská Bystrica)

- Prešov Region (Prešovský kraj) (capital Prešov)

- Košice Region (Košický kraj) (capital Košice)

(the word kraj can be replaced by samosprávny kraj or by VÚC in each case)

The "kraje" are subdivided into many okresy (sg. okres, usually translated as districts). Slovakia currently has 79 districts. The districts are then subdivided into zuj ("village" or "municipality").

In terms of economics and unemployment rate, the western regions are richer than eastern regions; however the relative difference is no bigger than in most EU countries having regional differences.

Economy

The Slovak economy is considered a tiger economy, with the country dubbed the Tatra Tiger. Slovakia has achieved a difficult transition from a centrally planned economy to a modern, high-income[3] market economy. Major privatizations are nearly complete, the banking sector is almost completely in private hands, and foreign investment has picked up.

Slovakia's economy is characterized by sustained high economic growth. In 2006, Slovakia achieved the highest growth of GDP (8.9%) among the members of OECD. The annual GDP growth in 2007 is estimated at 10.4% with the record level of 14.3% reached in the fourth quarter.[28]

Unemployment, peaking at 19.2% at the end of 1999, decreased to 7.51% in October 2008 according to the Statistical Office of the Slovak Republic.[29] In addition to economic growth, migration of workers to other EU countries also contributed to this reduction. According to Eurostat, which uses a calculation method different from that of the Statistical Office of the Slovak Republic, the unemployment rate is still the second highest after Spain in the EU-15 group at 9.9%.[30]

Inflation dropped from an average annual rate of 12.0% in 2000 to just 3.3% in the election year 2002, but it rose again in 2003-2004 because of increases in taxes and regulated prices. It reached 3.7 % in 2005.

Slovakia adopted the euro currency on 1 January 2009 as the 16th member of the Eurozone. The euro in Slovakia was approved by the European commission on 7 May 2008. The Slovak koruna was revalued on 28 May 2008 to 30.126 for 1 euro,[31] which was also the exchange rate for the euro.[32]

Slovakia is an attractive country for foreign investors mainly because of its lower labour costs, low tax rates and well educated labour force. In recent years, Slovakia has been pursuing a policy of encouraging foreign investment. FDI inflow grew more than 600% from 2000 and cumulatively reached an all-time high of $17.3 billion USD in 2006, or around $18,000 per capita by the end of 2006.

Despite a sufficient number of researchers and a solid secondary educational system, Slovakia, along with other post-communist countries, still faces many challenges in the field of modern knowledge economy. The business and public research and development expenditures are well below the EU average. The Programme for International Student Assessment, coordinated by the OECD, currently ranks Slovak secondary education as the 30th in the world (placing it just below the United States and just above Spain).[33]

In March 2008, the Ministry of Finance announced that Slovakia's economy is developed enough to stop being an aid receiver from the World Bank. Slovakia will become an aid provider by the end of 2008.[34]

Industry

Although Slovakia's GDP comes mainly from the tertiary (services) sector, the country's industry also plays an important role within its economy. The main industry sectors are car manufacturing and electrical engineering. Since 2007, Slovakia has been the world's largest producer of cars per capita[35], with a total of 571,071 cars manufactured in the country in 2007 alone[35]. There are currently three car manufacturers: Volkswagen in Bratislava, PSA Peugeot Citroen in Trnava and Kia Motors in Žilina.

From electrical engineering companies, Sony has a factory at Nitra for LCD TV manufacturing, Samsung at Galanta for computer monitors and television sets manufacturing.

Bratislava's geographical position in Central Europe has long made Bratislava a natural crossroads for international trade traffic.[36][37] Various ancient trade routes, such as the Amber Road and the Danube waterway have crossed territory of today Bratislava. Today Bratislava is the road, railway, waterway and airway hub.[38]

Infrastructures

Road

The city is a large international motorway junction: The D1 motorway connects Bratislava to Trnava, Nitra, Trenčín, Žilina and beyond, while the D2 motorway, going in the north-south direction, connects it to Prague, Brno and Budapest in the north-south direction. The D4 motorway (an outer bypass), which would ease the pressure on the city highway system, is mostly at the planning stage.

The A6 motorway to Vienna connects Slovakia directly to the Austrian motorway system and was opened on 19 November 2007.[39]

Currently, five bridges stand over the Danube (ordered by the flow of the river): Lafranconi Bridge, Nový Most, Starý most, Most Apollo and Prístavný most.

The city's inner network of roadways is made on the radial-circular shape. Nowadays, Bratislava experiences a sharp increase in the road traffic, increasing pressure on the road network. There are about 200,000 registered cars in Bratislava, what is approximately 2 inhabitants per one car.[38]

Rail

The first railway in the whole Kingdom of Hungary was built in 1840, when a horse-drawn railway was built to Svätý Jur and later extended into Trnava and Sereď in 1846 (the track was converted for steam trains in the 1870s).[40] Steam traction was introduced in 1848, with a link to Vienna and in 1850 with a link to Budapest.

Air

Bratislava's M. R. Štefánik Airport, named after General Milan Rastislav Štefánik and also called Bratislava Airport (Letisko Bratislava), is the main international airport in Slovakia. It is located 9 kilometres (5.59 mi) north-east of the city centre. It serves civil and governmental, scheduled and unscheduled domestic and international flights. The current runways support the landing of all common types of aircraft currently used. The airport has enjoyed rapidly growing passenger traffic in recent years; it served 279,028 passengers in 2000, 1,937,642 in 2006 and 2,024,142 in 2007.[41]

River

The Port of Bratislava is one of the two international river ports in Slovakia. The port connects Bratislava to international boat traffic, especially the interconnection from the North Sea to the Black Sea via the Rhine-Main-Danube Canal. Additionally, tourist lines operate from Bratislava's passenger port, including routes to Devín, Vienna and elsewhere.

Public transport

Public transportation in Bratislava is managed by Dopravný podnik Bratislava, a city-owned company. The transport system is known as Mestská hromadná doprava (MHD, Municipal Mass Transit). The history of public transportation in Bratislava began in 1895, with the opening of the first tram route.[42]

The system uses three main types of vehicles. Buses cover almost the entire city and go to the most remote boroughs and areas, with 60 daily routes, 20 night routes and other routes on certain occasions. Trams (streetcars) cover 13 heavily-used commuter routes, except for Petržalka.Trolleybuses serve as a complementary means of transport, with 13 routes.[43][44] An additional service, Bratislava Integrated Transport (Bratislavská integrovaná doprava), links train and bus routes in the city with points beyond.

Transport junctions include Trnavské mýto, Račianske mýto, Patrónka, main rail station, and others.

Tourism

Slovakia features natural landscapes, mountains, caves, medieval castles and towns, folk architecture, spas and ski resorts. More than 1.6 million people visited Slovakia in 2006, and the most attractive destinations are the capital of Bratislava and the High Tatras.[45] Most visitors come from the Czech Republic (about 26%), Poland (15%) and Germany (11%).[46]

Science

Slovak inventions include the double achromatic objective lens (Jozef Maximilián Petzval), wireless telegraph (Jozef Murgaš), the first used parachute[47] (Štefan Banič) and the steam and gas turbine[48] (Aurel Stodola). The invention of the electric motor and first electrical generator are attributed to Ányos Jedlik/Štefan Anián Jedlík, of Slovak-Hungarian origin. German-Hungarian Nobel prize winner for physics, Philipp Lenard, was born in present-day Bratislava.

American astronaut Eugene Cernan (Čerňan), the last man on the Moon, has Czecho-Slovak parentage. Ivan Bella was the first Slovak citizen in space, having participated in a 9-day joint Russian-French-Slovak mission on the space station Mir in 1999.

Culture

- See also List of Slovaks

Slovaks have a very rich, old and diverse folk culture (songs, fairy tales, dances), literature, music and art.

The art of Slovakia can be traced back to the Middle Ages, when some of the greatest masterpieces of the country's history were created. Significant figures from this period included the many Masters, among them the Master Paul of Levoča and Master MS. More contemporary art can be seen in the shadows of Koloman Sokol, Albín Brunovský, Martin Benka, Mikuláš Galanda, and Ľudovít Fulla. The most important Slovak composers have been Eugen Suchoň, Ján Cikker, and Alexander Moyzes, in the 21st century Vladimir Godar and Peter Machajdik.

The most famous Slovak names can indubitably be attributed to invention and technology. Such people include Jozef Murgaš, the inventor of wireless telegraphy; Ján Bahýľ, the inventor of the motor-driven helicopter; Jozef Maximilián Petzval, inventor of the camera zoom and lens (although he considered himself an ethnic Hungarian); Jozef Karol Hell (although German by heritage), inventor of the industrial water pump; Štefan Banič, inventor of the modern parachute; Aurel Stodola, inventor of the bionic arm and pioneer in thermodynamics; and, more recently, John Dopyera, father of modern acoustic string instruments.

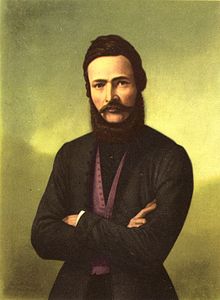

Štefan Anián Jedlík

Slovakia is also known for its polyhistors, of whom include Pavol Jozef Šafárik, Matej Bel, Ján Kollár, and its political revolutionaries, such Milan Rastislav Štefánik and Alexander Dubček.

There were two leading persons who codified the Slovak language. The first one was Anton Bernolák whose concept was based on the dialect of western Slovakia (1787). It was the enactment of the first national literary language of Slovaks ever. The second notable man was Ľudovít Štúr. His formation of the Slovak language had principles in the dialect of central Slovakia (1843).

The best known Slovak hero was Juraj Jánošík (the Slovak equivalent of Robin Hood). Prominent explorer Móric Benyovszky had Slovak ancestors.

In terms of sports, the Slovaks are probably best known (in North America) for their hockey personalities, especially Stan Mikita, Peter Šťastný, Peter Bondra, Žigmund Pálffy and Marián Hossa. For a list see List of Slovaks.

For a list of the most notable Slovak writers and poets, see List of Slovak authors.

Literature

The first monuments of literature in present-day Slovakia are from the time of Great Moravia (from 863 to the early 10th century). Authors from this period are Saint Cyril, Saint Methodius and Clement of Ohrid. Works from this period, mostly written on Christian topics include: poem Proglas as a foreword to the four Gospels, partial translations of the Bible into Old Church Slavonic, Zakon sudnyj ljudem, etc.

The medieval period covers the span from the 11th to the 15th century. Literature in this period was written in Latin, Czech and slovakized Czech languages. Lyric (prayers, songs and formulas) was still controlled by the Church, while epic was concentrated on legends. Authors from this period include Johannes de Thurocz, author of the Chronica Hungarorum and Maurus. The worldly literature also emerged and chronicles were written in this period.

The character of a national literature first emerged in the 16th century, much later than in other national literatures. Latin dominates as the writing language in the 16th century. Besides the Church topics, antique topics, related to the ancient Greece and Rome.

Cuisine

Pork, beef and poultry are the main meats consumed in Slovakia, with pork being the most popular by a substantial margin. Among poultry, chicken is most common, although duck, goose, and turkey are also well established. A blood sausage called jaternice also has a following, containing any and all parts of a butchered pig. Game meats, especially boar, rabbit, and venison, are also widely available around the year. Lamb and goat are also available, but for the most part are not very popular. The consumption of horse meat is generally frowned upon.

Wine is common throughout all parts of Slovakia. Slovak wine comes predominantly from the southern areas along the Danube and its tributaries; the northern half of the country is too cold and mountainous to grow grapevines. Traditionally, white wine was more popular than red or rosé (except in some regions), and sweet wine more popular than dry, but both these tastes seem to be changing.[49] Beer (in slovak language Pivo) is also popular throughout the country.

Music

Popular music began to replace folk music beginning in the 1950s, when Slovakia was a part of Czechoslovakia; American jazz, R&B, and rock and roll were popular, alongside waltzes, polkas, and czardas, among other folk forms. By the end of the '50s, radios were common household items, though only state stations were legal. Slovak popular music began as a mix of bossa nova, cool jazz, and rock, with propagandistic lyrics. Dissenters listened to ORF (Austrian Radio), Radio Luxembourg, or Slobodna Europa (Radio Free Europe), which played more rock. Czechoslovakia was more passive in the face of Soviet domination, and thus radio and the whole music industry toed the line more closely than other satellite states.

After the Velvet Revolution and the declaration of the Slovak state, domestic music greatly diversified as free enterprise allowed a great expansion in the number of bands and genres represented in the Slovak market. Soon, however, major labels brought pop music to Slovakia and drove many of the small companies out of business. The 1990s, American grunge and alternative rock, and Britpop gain a wide following, as well as a newfound popularity in musicals.

Sport

Various sports and sports teams have a long tradition in Bratislava, with many teams and individuals competing in Slovak and international leagues and competitions.

Football is currently represented by two clubs playing in the top Slovak football league, the Corgoň Liga. ŠK Slovan Bratislava, founded in 1919, has its home ground at the Tehelné pole stadium. ŠK Slovan is the most successful football club in Slovak history, being the only club from the former Czechoslovakia to win the European football competition the Cup Winners' Cup, in 1969.[50] FC Artmedia Bratislava is the oldest of Bratislava's football clubs, founded in 1898, and is based at Štadión Pasienky in Nové Mesto (formerly at Štadión Petržalka in Petržalka). Another known club from the city is FK Inter Bratislava. Founded in 1945, they have their home ground at Štadión Pasienky and currently play in the Slovak Second Division.

Bratislava is home to three winter sports arenas: Ondrej Nepela Winter Sports Stadium, V. Dzurilla Winter Sports Stadium, and Dúbravka Winter Sports Stadium. The HC Slovan Bratislava ice hockey team represents Bratislava in Slovakia's top ice hockey league, the Slovak Extraliga. Samsung Arena, a part of Ondrej Nepela Winter Sports Stadium, is home to HC Slovan. The Ice Hockey World Championships in 1959 and 1992 were played in Bratislava, and the 2011 Men's Ice Hockey World Championships will be held in Bratislava and Košice, for which a new arena is being planned.[51]

The Čunovo Water Sports Centre is a whitewater slalom and rafting area, close to the Gabčíkovo dam. The Centre hosts several international and national canoe and kayak competitions annually..

The National Tennis Centre, which includes Sibamac Arena, hosts various cultural, sporting and social events. Several Davis Cup matches have been played there, including the 2005 Davis Cup final. The city is represented in the top Slovak leagues in women's and men's basketball, women's handball and volleyball, and men's water polo. The Devín–Bratislava National run is the oldest athletic event in Slovakia,[52] and the Bratislava City Marathon has been held annually since 2006. A race track is located in Petržalka, where horse racing and dog racing events and dog shows are held regularly.

International rankings

- Human Development Index 2007: Rank 42nd out of 177 countries

- Index of Economic Freedom 2008: Rank 35th out of 157 countries

- Reporters Without Borders world-wide press freedom index 2008: Rank 7th (along with 6 other countries) out of 173 countries

- Global Competitiveness Report ranking 2008-2009: Rank 46th out of 157 countries

- Corruption Perceptions Index 2007: Rank 49th out of 180 countries

- Democracy Index 2008: Rank 44th out of 167 countries

- Global Peace Index 2007: Rank 17

- PISA 2006: Rank 27

See also

References

- ^ a b c d "Slovakia". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 2008-10-09.

- ^ a b c d "Slovakia". The World Factbook. CIA. 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ a b World Bank Country Classification, 2007

- ^ a b . p. 360.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ a b Kristó, Gyula (editor) (1994). Korai Magyar Történeti Lexikon (9-14. század) (Encyclopedia of the Early Hungarian History - 9-14th centuries). Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó. p. 467. ISBN 963 05 6722 9.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) Cite error: The named reference "Korai Magyar Történeti Lexikon" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Poulik, Josef (1978). "The Origins of Christianity in Slavonic Countries North of the Middle Danube Basin". World Archaeology. 10 (2): 158–171.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c Čaplovič, Dušan (2000). Dejiny Slovenska. Bratislava: AEP.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Annales Fuldenses, sive, Annales regni Francorum orientalis ab Einhardo, Ruodolfo, Meginhardo Fuldensibus, Seligenstadi, Fuldae, Mogontiaci conscripti cum continuationibus Ratisbonensi et Altahensibus / post editionem G.H. Pertzii recognovit Friderious Kurze ; Accedunt Annales Fuldenses antiquissimi. Hannover: Imprensis Bibliopolii Hahniani. 1978.."

- ^ a b Tóth, Sándor László (1998). Levediától a Kárpát-medencéig ("From Levedia to the Carpathian Basin"). Szeged: Szegedi Középkorász Műhely. p. 199. ISBN 963 482 175 8.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) Cite error: The named reference "Tóth" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ . p. 51.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Kristó, Gyula (1996). Magyar honfoglalás - honfoglaló magyarok ("The Hungarians' Occupation of their Country - The Hungarians occupying their Country"). Kossuth Könyvkiadó. pp. 84–85. ISBN 963 09 3836 7.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Tibenský, Ján; et al. (1971). Slovensko: Dejiny. Bratislava: Obzor.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ "Academia Istropolitana". City of Bratislava. February 14, 2005.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Divided Memories: The Image of the First World War in the Historical Memory of Slovaks, Slovak Sociological Review , Issue 3 /2003 [1]

- ^ Gerhard L. Weinberg, The Foreign Policy of Hitler's Germany: Starting World War II, 1937-1939 (Chicago, 1980), pp. 470-481.

- ^ Leni Yahil, The Holocaust: The Fate of European Jewry, 1932-1945 (Oxford, 1990), pp. 402-403.

- ^ For the higher figure, see Milan S. Durica, The Slovak Involvement in the Tragedy of the European Jews (Abano Terme: Piovan Editore, 1989), p. 12; for the lower figure, see Gila Fatran, "The Struggle for Jewish Survival During the Holocaust" in The Tragedy of the Jews of Slovakia (Banská Bystrica, 2002), p. 148.

- ^ Management of the Hungarian Issue in Slovak Politics

- ^ German minority in Slovakia after 1918 (Nemecká menšina na Slovensku po roku 1918) (in Slovak)

- ^ Rock, David (2002). Coming home to Germany? : the integration of ethnic Germans from central and eastern Europe in the Federal Republic. New York; Oxford: Berghahn.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Bratislava at euroWEATHER

- ^ Košice at euroWEATHER

- ^ Poprad at euroWEATHER

- ^ Sliač at euroWEATHER

- ^ Roma political and cultural activists estimate that the number of Roma in Slovakia is higher, citing a figure of 350,000 to 400,000 [2]

- ^ M. Vašečka, “A Global Report on Roma in Slovakia”, (Institute of Public Affairs: Bratislava, 2002) + Minority Rights Group. See: Equality, Diversity and Enlargement. European Commission: Brussels, 2003, p. 104

- ^ Vogelsang, Peter (2002). "Deportations". The Danish Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Gross domestic product in the 4th quarter of 2007". Statistical Office of the Slovak Republic. 3 March 2008.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Slovak unemployment falls to 7.84 pct in Feb from Jan from Thomson Financial News Limited

- ^ Eurozone unemployment up to 7.5%

- ^ Slovakia revalues currency ahead of euro entry at Guardian.co.uk

- ^ 'Slovak euro exchange rate is set' at BBC

- ^ Range of rank on the PISA 2006 science scale at OECD

- ^ Slovakia Is Sufficiently Developled to Offer Aid Within World Bank at TASR

- ^ a b Slovak Car Industry Production Almost Doubled in 2007

- ^ "Bratislava in Encyclopædia Britannica". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. Retrieved April 30.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "MIPIM 2007 - Other Segments". City of Bratislava. 2007. Retrieved April 30.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Transport and Infrastructure". City of Bratislava. 2007. Retrieved 12 June.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "Do Viedne už netreba ísť po okresnej ceste" (in Slovak). Pravda. 2007. Retrieved November 19.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "The Bratislava-Trnava Horse-drawn Railway". Slovak ministry of transport, post and telecommunications. Retrieved 12 June.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "Letisko Bratislava - O letisku - Štatistické údaje (Airport Bratislava - About airport - Statistical data)". Letisko M.R. Štefánika - Airport Bratislava. 2008. Retrieved January 19.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "Z histórie (History)" (in Slovak). Dopravný podnik Bratislava. 2004. Retrieved 17 May.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "Trasy liniek (routes)" (in Slovak). Dopravný podnik Bratislava. 2007. Retrieved 17 May.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "Pilotný projekt nočných liniek MHD od 1. júla 2007" (in Slovak). Dopravný podnik Bratislava. 2007. Retrieved 26 July.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "The number of tourists in Slovakia is increasing (Turistov na Slovensku pribúda)" (in Slovak). Aktualne.sk. 30 June 2007. Retrieved 30 December.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "Most tourists in Slovakia still come from the Czech Republic (Na Slovensko chodí stále najviac turistov z ČR)" (in Slovak). Monika Martišková, Joj.sk. 20 September 2007. Retrieved 28 November.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ European countries (Slovakia) at europa.eu.int

- ^ Fund of A.Stodola

- ^ Slovak Cuisine

- ^ "Slovan Bratislava - najväčšie úspechy (Slovan Bratislava - greatest achievements)" (in Slovak). Slovan Bratislava. 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help). "Slovan Bratislava - História (History)" (in Slovak). Slovan Bratislava. 2006.{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Marta Ďurianová (May 22, 2006). "Slovakia to host ice hockey World Championships in 2011". The Slovak Spectator.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "Twin City Journal - The Oldest Athletic Event in Slovakia" (PDF). City of Bratislava. 2006. pp. p. 7.

{{cite web}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)

Further reading

- Anton Spiesz and Dusan Caplovic: Illustrated Slovak History: A Struggle for Sovereignty in Central Europe ISBN 0-86516-426-6

- Elena Mannová (ed.): A Concise History of Slovakia ISBN 80-88880-42-4

- Pavel Dvorak: The Early History of Slovakia in Images ISBN 80-85501-34-1

- Julius Bartl and Dusan Skvarna: Slovak History: Chronology & Lexicon ISBN 086-5164444

- Olga Drobna, Eduard Drobny and Magdalena Gocnikova: Slovakia: The Heart of Europe ISBN 086-5163197

- Karen Henderson: Slovakia: The Escape from Invisibility ISBN 0415274362

- Stanislav Kirschbaum: A History of Slovakia : The Struggle for Survival ISBN 0312161255

- Alfred Horn: Insight Guide: Czech & Slovak Republics ISBN 088-7296556

- Rob Humphreys: The Rough Guide to the Czech and Slovak Republics ISBN 1858289041

- Michael Jacobs: Blue Guide: Czech and Slovak Republics ISBN 0393319326

- Neil Wilson, Richard Nebesky: Lonely Planet World Guide: Czech & Slovak Republics ISBN 1864502126

- Eugen Lazistan, Fedor Mikovič, Ivan Kučma and Anna Jurečková: Slovakia: A Photographic Odyssey ISBN 086-5165173

- Lil Junas: My Slovakia: An American's View ISBN 8070906227

- Sharon Fisher: Political Change in Post-Communist Slovakia and Croatia: From Nationalist to Europeanist ISBN 1-4039-7286-9

External links

- Government

- The Slovak Republic Government Office

- Statistical Office of the Slovak Republic

- Chief of State and Cabinet Members

- General information

- "Slovakia". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency.

- Slovakia from UCB Libraries GovPubs

- Template:Dmoz

Wikimedia Atlas of Slovakia

Wikimedia Atlas of Slovakia- Google satellite map of Slovakia

- Template:Wikitravel