Saponin

Saponins are a class of chemical compounds, one of many secondary metabolites found in natural sources, with saponins found in particular abundance in various plant species. Specifically, they are amphipathic glycosides grouped phenomenologically by the soap-like foaming they produce when shaken in aqueous solutions, and structurally by their composition of one or more hydrophilic glycoside moieties combined with a lipophilic triterpene derivative.[1][2] A ready and therapeutically relevant example is the cardio-active agent digoxin, from common foxglove.

Structural variety and biosynthesis

The aglycone (glycoside-free portion) of the saponins are termed sapogenins. The number of saccharide chains attached to the sapogenin/aglycone core can vary– giving rise to another dimension of nomenclature (monodesmosidic, bidesmosidic, etc.[1])– as can the length of each chain. A somewhat dated compilation has the range of saccharide chain lengths being 1–11, with the numbers 2-5 being the most frequent, and with both linear and branched chain saccharides being represented.[1] Dietary monosaccharides such as D-glucose and D-galactose are among the most common components of the attached chains.[1]

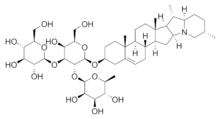

The lipophilic aglycone can be any one of a wide variety of polycyclic organic structures originating from the serial addition of ten-carbon (C10) terpene units to compose a C30 triterpene skeleton,[3][4] often with subsequent alteration to produce a C27 steroidal skeleton.[1] The subset of saponins that are steroidal have been termed saraponins;[2] Aglycone derivatives can also incorporate nitrogen, so that some saponins also present chemical and pharmacologic characteristics of alkaloid natural products. The figure at right above presents the structure of the alkaloid phytotoxin solanine, a monodesmosidic, branched-saccharide steroidal saponin. (The lipophilic steroidal structure is the series of connected six- and five-membered rings at the right of the structure, while the three oxygen-rich sugar rings are at left and below. Note the nitrogen atom inserted into the steroid skeleton at right.)

Sources of saponin

Saponins have historically been understood to be plant-derived, but they have also been isolated from marine organisms.[1][5] Saponins are indeed found in many plants,[1][6] and derive their name from the soapwort plant (Genus Saponaria, Family Caryophyllaceae), the root of which was used historically as a soap.[2] Saponins are also found in the botanical family Sapindaceae, with its defining genus Sapindus (soapberry or soapnut), and in the closely related families Aceraceae (maples) and Hippocastanaceae (horse chestnuts; ref. needed). It is also found heavily in gynostemma pentaphyllum (Genus Gynostemma, Family Cucurbitaceae) in a form called gypenosides, and ginseng (Genus Panax, Family Araliaceae) in a form called ginsenosides. Within these families, this class of chemical compounds are found in various parts of the plant: leaves, stems, roots, bulbs, blossom and fruit.[citation needed] Commercial formulations of plant-derived saponins– e.g., from the soap bark (or soapbark) tree, Quillaja saponaria, and from other sources—are available via controlled manufacturing processes, which make them of use as chemical and biomedical reagents.[7]

Role in plant ecology and impact on animal foraging

In plants, saponins may serve as anti-feedants,[2][4] and to protect the plant against microbes and fungi.[citation needed] Some plant saponins (e.g. from oat and spinach) may enhance nutrient absorption and aid in animal digestion. However, saponins are often bitter to taste, and so can reduce plant palatability (e.g., in livestock feeds), or even imbue them with life-threatening animal toxicity.[4] Data make clear that some saponins are toxic to cold-blooded organisms and insects at particular concentrations.[4] There is a need for further research to define the roles of these natural products in their host organisms—which have been described as "poorly understood" to date.[4]

Established research bioactivities and therapeutic claims

Bioactivities

One research use of the saponin class of natural products involves their complexation with cholesterol to form pores in cell membrane bilayers, e.g., in red cell (erythrocyte) membranes, where complexation leads to red cell lysis (hemolysis) on intravenous injection.[8] In addition, the amphipathic nature of the class gives them activity as surfactants that can be used to enhance penetration of macromolecules such as proteins through cell membranes.[7] Saponins have also been used as adjuvants in vaccines.[7]

Medical uses

There is tremendous, commercially driven promotion of saponins as dietary supplements and nutriceuticals. There is evidence of the presence of saponins in traditional medicine preparations,[9][10] where oral administrations might be expected to lead to hydrolysis of glycoside from terpenoid (and obviation of any toxicity associated with the intact molecule). But as is often the case with wide-ranging commercial therapeutic claims for natural products:

- the claims for organismal/human benefit are often based on very preliminary biochemical or cell biological studies;[11] and

- mention is generally omitted of the possibilities of individual chemical sensitivity, or to the general toxicity of specific agents,[12]) and high toxicity of selected cases.

While such statements require constant review (and despite the myriad web claims to the contrary), it appears that there are very limited US, EU, etc. agency-approved roles for saponins in human therapy. In their use as adjuvants in the production of vaccines, toxicity associated with sterol complexation remains a major issue for attention.[13] Even in the case of digoxin, therapeutic benefit from the cardiotoxin is a result of careful administration of an appropriate dose. Very great care needs to be exercised in evaluating or acting on specific claims of therapeutic benefit from ingesting saponin-type and other natural products.

See also

In herbal medicine saponins are used for Anti-inflammatories:- (Licorice) Aesculus hippocastanum,Erynginum planum. etc Analgesic:- platycodon grandiflorum, dianthis barbatus,Panax notoginseng etc Antipyretic activity:- Bupleurum Chinese Anti ulcer:- glycyrrhiza glabra, Quillia etc Anti tumor activity:-Thalictrum foetidum, Saponaria officinalis etc Anti fungal :-Oats, Agave sisalana Anti viral :- Gymnema sylvestre Cough:- Polygala senega, (Snakeroot), Hedera helix, (ivy) Cortsone:- Dioscorea (digitonin, botogenin) Agave (hecogenin, manogenin and gitogenin) Smilax (sasaspogenin, manogenin, gitogenin) Immunomodulation:- Quillaja saponaria,Panax GInseng Hypercholesterolaemic activity:-Alfalfa, legumes, Calendula Tonics:-Ginsengs they are poorly absorbes in animals. thus the toxic level is c. over 50-100 mg/kg. They are 10-1000 times less toxic orally than introvenesously They are either excreted unchanged or metabolised in the gut. So how they work is apuzzle. They are insoluble in absolute ethanol, acetone or dimethyl ether. They can form insouble saponin-mineral complexes with iron zinc and calcium 160g ady of alfalfa in humans produced mild anemia afet 6 weeks.

References

- ^ a b c d e f g Hostettmann, K. (1995). Saponins. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 3ff. ISBN 0-521-32970-1. OCLC 29670810.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d "Saponins". Cornell University. 14 August 2008. Retrieved 23 February 2009.

- ^ "Project Summary: Functional Genomics of Triterpene Saponin Biosynthesis in Medicago Truncatula". Retrieved 23 February 2009.

- ^ a b c d e Foerster, Hartmut (22 May 2006). "MetaCyc Pathway: saponin biosynthesis I". Retrieved 23 February 2009.

- ^ Riguera, Ricardo (1997). "Isolating bioactive compounds from marine organisms". Journal of Marine Biotechnology. 5 (4): 187–193.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Liener, Irvin E (1980). Toxic constituents fo plant foodstuffs. New York City: Academic Press. p. 161. ISBN 0-12-449960-0. OCLC 5447168.[verification needed]

- ^ a b c "Saponin from quillaja bark". Sigma-Aldrich. Retrieved 23 February 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|BRAND_KEY&F=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|SIGMA&N5=ignored (help) - ^ Francis, George (2002). "The biological action of saponins in animal systems: a review". British Journal of Nutrition. 88 (6): 587–605. doi:10.1079/BJN2002725. PMID 12493081.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Asl, Marjan Nassiri (2008). "Review of pharmacological effects of Glycyrrhiza sp. and its bioactive compounds". Phytotherapy Research. 22 (6): 709–24. doi:10.1002/ptr.2362. PMID 18446848.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Xu R, Zhao W, Xu J, Shao B, Qin G (1996). "Studies on bioactive saponins from Chinese medicinal plants". Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 404: 371–82. PMID 8957308.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "MetaCyc Pathway: saponin biosynthesis IV". Retrieved 23 February 2009.

- ^ "Saponin". J.T. Baker. Retrieved 23 February 2009.

- ^ Skene, Caroline D. (2006). "Saponin-adjuvanted particulate vaccines for clinical use". Methods. 40 (1): 53–9. doi:10.1016/j.ymeth.2006.05.019. PMID 16997713.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)

External links

- Medical Dictionary on Saponin

- Saponins in Wine, by ScienceDaily, accessed Sep 9,2003

- Molecular Expressions Phytochemical Gallery - Saponin

- Saponins: Suprising [sic] benefits of desert plants

- How to survive the world's worst diet

- Quillia Extracts JECFA Food Additives Series 48