Balochistan, Pakistan

Balochistan | |

|---|---|

Astola island | |

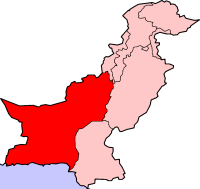

Location of Balochistan | |

| Country | |

| Established | 1 July 1970 |

| Capital | Quetta |

| Largest city | Quetta |

| Government | |

| • Type | Province |

| • Body | Provincial Assembly |

| • Governor | Nawab Zulfikar Ali Magsi |

| • Chief Minister | Nawab Aslam Raisani (PPP) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 347,190 km2 (134,050 sq mi) |

| Population (2005)[1] | |

| • Total | 7,800,000 |

| • Density | 22/km2 (58/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+5 (PKT) |

| Main Language(s) | |

| Assembly seats | 65 |

| Districts | 30 |

| Union Councils | 86 |

| Website | balochistan.gov.pk |

Balochistan (Template:Lang-ur) is the largest province by area of Pakistan, constituting approximately 48% of the total area of Pakistan. At the 1998 census, Balochistan had a population of roughly 6.6 million.[2] Covering a sizable portion of the country, it is Pakistan's largest province, as well as its poorest and least populated.

Its neighbouring regions are Iran to the west, Afghanistan and the North-West Frontier Province to the north, Punjab and Sindh provinces to the east. To the south is the Arabian Sea. The main languages in the province are Balochi, Saraiki, Brahui, Pashto, and Sindhi.[3] The capital, and only city, is Quetta; all the other towns and villages are underdeveloped. The Baloch and Pashtun people constitute the two major ethnic groups; a mixed ethnic stock, mainly of Sindhi origin, forms the third major group (Sindhi Baloch).[3] Balochistan is rich in mineral resources; it is the second major supplier, after Sindh province, of natural gas.

Geography

Balochistan is located at the south-eastern edge of the Iranian plateau. It strategically bridges the Middle East and Southwest Asia to Central Asia and South Asia, and forms the closest oceanic frontage for the land-locked countries of Central Asia.

By the surface area, Balochistan is easily the largest of the four provinces of Pakistan at 347,190 km² (134,051 mi²), which composes approximately 44% of the total land area of Pakistan. The population density is very low due to the mountainous terrain and scarcity of water. The southern region is known as Makran. The central region is known as Kalat.

The Sulaiman Mountains dominate the northeast corner and the Bolan Pass is a natural route into Afghanistan towards Kandahar, used as a passageway during the British campaigns to Afghanistan.[4] Much of the province south of the Quetta region is sparse desert terrain with pockets of towns mostly near rivers and streams.

The capital, Quetta, is located in the most densely populated district in the northeast of the province. It is situated in a river valley near the border with Afghanistan, with a road to Kandahar in the northwest.

At Gwadar on the coast of the Arabian Sea, the Pakistani government has built a large port with Chinese help which is now operating successfully.

Climate

Very cold winters and hot summers characterise the climate of the upper highlands. Winters of the lower highlands vary from extremely cold in the northern districts to mild conditions closer to the Makran coast. Summers are hot and dry, especially the arid zones of Chaghai and Kharan districts. The plain areas are also very hot in summer with temperatures rising as high as 139 °F (59 °C). Winters are mild on the plains with the temperature never falling below the freezing point. The desert climate is characterised by hot and very arid conditions. Occasionally strong windstorms make these areas very inhospitable.

Demographics

| Historical populations | ||

|---|---|---|

| Census | Population | Urban |

|

| ||

| 1951 | 1,167,167 | 12.38% |

| 1961 | 1,353,484 | 16.87% |

| 1972 | 2,428,678 | 16.45% |

| 1981 | 4,332,376 | 15.62% |

| 1998 | 6,565,885 | 23.89% |

As of the 1998 census, Balochistan had a population of 6.6 million inhabitants, representing approximately 5% of the Pakistani population.[2] Official estimates of Balochistan's population grew from approximately 7.45 million in 2003[3] to 7.8 million in 2005.[1] According to the 2008 Pakistan Statistical Year Book, households whose primary language is Balochi represent 54.8% of Balochistan's population while 29,5% of households speak Pashto, making Balochi an Pashtu the two dominant languages in the region. Other languages include Brahui,Sindhi, Punjabiand Saraiki.[5] Balochi-speaking people are concentrated in the sparsely populated west, east, south and southeast; Brahui speakers dominate in the centre of the province, while the Pashtuns are the majority in the north. The Kalat and Mastung areas speak Brahui. Quetta, the capital of the province, is largely populated with Pashtuns, with a significant Baloch presence. In the Lasbela District, the majority of the population speaks Sindhi, Balochi, or Lasi. Sindhi is also widely spoken in the Nasirabad District and the cities of Sibi and Dera Murad Jamali.[citation needed] A large number of Balochs moved to Quetta after it became the capital of Balochistan in 1970. Near the Kalat region and other parts of the province there are significant numbers of Baloch Brahui speakers. Along the coast various Makrani Balochi speakers predominate. Afghan refugees can also be found in the province, including Pashtuns and Tajiks. Many Sindhi farmers have moved to the more arable lands in the east.[citation needed]

Copper deposits

One of the world's largest copper deposits (and its matrix-associated residual gold) have been found at Reko Diq in the Chagai District of Balochistan. Reko Diq is a giant mining project in Chaghi. The main license (EL5) is held jointly by the Government of Balochistan (25%), Antofagasta Minerals (37.5%) and Barrick Gold (37.5%). The deposits at Reko Diq are hoped to be even bigger than those of Sarcheshmeh in Iran and Escondida in Chile (presently, the second and the third largest proven deposits of copper in the world).

BHP Billiton, the world's largest copper mining company, began the project in cooperation with the Australian firm Tethyan, entering into a joint venture with the Balochistan government. The potential annual copper production has been estimated to be 900,000 to 2.2 million tons.[citation needed] The deposits seem to be largely of porphyry rock nature.[citation needed]

| Provincial flag | Flag of Balochistan | |

| Provincial language | بلوچی |

|

| Provincial animal | Dromedary camel |

|

| Provincial bird | Houbara bustard |

|

| Provincial tree | Date palm |

|

| Provincial flower | Ephedra (genus) |

|

Society

Balochistan culture is primarily tribal, deeply patriarchal and conservative. Baloch society is dominated by tribal chieftains called Mirs, Sardars and Nawabs, who are the ruling elite of Balochistan and have been criticized for blocking the educational development and empowerment of the Baloch people [citation needed][weasel words] lest the status quo be challenged.

'Honour killings' are commonplace[6] but still discouraged by the majority of the population[citation needed]. In one recent incident in August 2008, the Asian Human Rights Commission reported that five women (including three teenagers) in a remote village had been beaten, shot and buried alive in a ditch for the crime of seeking to choose their own husbands. One of the tribesmen involved was the younger brother of a provincial minister from the ruling Pakistan People's Party, and local police therefore refused to take any action.[7]

After human rights activists brought the case to national and international attention, Israr Ullah Zehri, who represents Balochistan in the Pakistani Parliament, defended the killings and asked his fellow legislators not to make a fuss about the incident. He told Parliament, "These are centuries-old traditions, and I will continue to defend them. Only those who indulge in immoral acts should be afraid." But many Baloch literate are against the horrific crimes which took place in Balochistan. According to majority of Baloch, the person or tribe head should be brought to the court and must be punished. Many Baloch or Balochis have denied the fact that Karo Kari is part of Balochi culture. They claim it was a nomadic cultural practice which was stopped many years ago, but because of poor administration by the Pakistani government and to demilitarize the Baloch, such acts are now taking place.[8]

History

Balochistan was the site of the earliest known farming settlements in Indus Valley Civilization, the earliest of which was Mehrgarh dated at 6500 BCE. Balochistan corresponds to the ancient Achaemenid province of Gedrosia. Balochistan was sparsely populated by various tribes of Dravidian and Indo-Aryan origin for centuries following the decline of the nearby Harappa-Mohenjo-daro civilisation to the east. Aryan invasions appear to have led to the eventual demise of the Elamo-Dravidian[9] with the exception of the Brahui tribes who may have arrived much later.

The Balochs began to arrive from their homeland in north-west Iran and appear to be an offshoot of the Medes, another branch being the Kurdish tribes that would mainly populate the western end of the Iranian plateau. Many Balochs believe that their origins are Semitic and not Iranian, contrary to linguistic and historical evidence. Baloch claim that they left their Aleppo homeland in Syria at some point during the 1st millennium CE and moved to Balochistan.[10] It is considered more likely they are an Iranian group who have absorbed some Arab ancestry and cultural traits. It is also believed that the Baloch have Arab ancestry – it could be they left the Arab world when Iraq broke from Persia in 652 AD and there is historical evidence that suggests they lived in Khuzestan and Bushehr before moving to Kerman and Hormozgan.[citation needed] The Baloch tribes eventually became a sizeable group rivalled in size only by another Iranian group, the Pashtuns, while the Brahuis increasingly came under the cultural influence of the Balochis.

In the 7th century the region was divided into two, the south was part of Kermān Province of the Persian Empire and the north was part of the Persian province Sistan. In early 644, the Islamic Caliph Umar sent Suhail ibn Adi from Busra to conquer the Kerman region of Iran; he was made governor of Kerman. From Kerman he entered the western Balochistan and conquered the region near to Persian frontiers.[11] South Western Balochistan was conquered during the campaign in Sistan the same year.

During Caliph Uthman’s reign in 652, Balochistan was re-conquered during the campaign against the revolt in Kerman, under the command of Majasha ibn Masood, it was first time when western Balochistan came directly under the Laws of Caliphate and gave tribute on agriculture.[12] In those days western Balochistan was included in the dominion of Kerman. In 654 Abdulrehman ibn Samrah was made governor of Sistan, an Islamic army was sent under him to crush the revolt in Zarang, which is now in southern Afghanistan. Conquering Zarang a column moved north ward to conquer areas up to Kabul and Ghazni in Hindu Kush Mountains, while another column moved towards North western Balochistan and conquered area up to the ancient city of Dawar and Qandabil (Bolan),[13] by 654 the whole of what is now Balochistan province of Pakistan was under the rule of Rashidun Caliphate except for the well defended mountain town of QaiQan (now Kalat), which was conquered during Caliph Ali’s reign.[14] Abdulrehman ibn Samrah made Zaranj his provincial capital and remained governor of these conquered areas from 654 to 656, until Uthman was murdered.

During the Caliphate of Ali, the areas of Balochistan, Makran again broke into revolt. Due to civil war in the Islamic empire Ali was unable to deal with these areas until 660 when he sent a large force under the command of Haris ibn Marah Abdi towards Makran, Balochistan and Sind. Haris ibn Marah Abdi arrived in Makran and conquered it by force then moved northward to north eastern Balochistan and re-conquered Qandabil (Bolan), then again moving south finally conquered Kalat after a fierce battle.[15] In 663 during the reign of Umayyad Caliph Muawiyah I, Muslim lost control of North eastern Balochistan and Kalat when Haris ibn Marah and large part of army died in the battle field against a revolt in Kalat.[16] Muslim forces latter re-gained the control of the area during Umayyads reign. It also remained part of Abbasid Caliphate's empire.

In the 15th century, Mir Chakar Khan Rind became the first king of Balochistan. Balochistan subsequently was dominated by empires based in Iran and Afghanistan as well as the Mughal Empire based in India. Nadir Shah won the allegiance of the rulers of Balochistan, Nadir Shah ceded Kalhoras of Sindh territories of Sibi-Kachi to Khan of Kalat[17][18][19][20] and later the successor of Nadir Shah, Ahmed Shah Durrani also won allegiance of that areas rulers. The area would eventually revert to local Baloch control, while parts of the northern regions would continue to be dominated by Pashtun tribes.

During the period of the British Raj, there were four Princely States in Balochistan: Makran, Kharan, Las Bela and Kalat. In 1876 Sir Robert Sandeman concluded a treaty with the Khan of Kalat and brought his territories - including Kharan, Makran, and Las Bela - under British suzerainty. After the Second Afghan War of 1878-80, the Treaty of Gandamak concluded in May 1879, the Afghan Emir ceded the districts of Quetta Pishin, Sibi, Harnai, and Thal Chotiali to the British. In 1883 the British leased the Bolan Pass, southeast of Quetta, from the Khan of Kalat on a permanent basis. In 1887 some areas of Balochistan were declared British territory. In 1893, Sir Mortimer Durand negotiated an agreement with Amir Abdur Rahman Khan of Afghanistan to fix the Durand Line running from Chitral to Balochistan to as the boundary between the Afghans and the British.

There were two devastating earthquakes in Balochistan during British colonial rule: The 1935 Balochistan Earthquake devastated Quetta and the 1945 Balochistan Earthquake, with its epicentre in Makran region, was felt in other regions of South Asia.

After independence from the British, Balochistan like much of Pakistan has experienced development. However, due to its sparse population, it has developed at a much slower rate than other parts of Pakistan. This has led to conflict in Balochistan.

Provincial government

The Unicameral Provincial Assembly of Balochistan comprises 65 seats of which 4% are reserved for non-Muslims and 16% for women only.

Administrative districts

Template:Districts of Balochistan (Pakistan) Map

Major cities and towns

Economy

Balochistan's share of the national economy has historically ranged between 3.7% to 4.9%.[21] Since 1972, Balochistan's economy has grown in size by 2.7 times.[22] The economy of the province is largely based upon the production of natural gas, coal and minerals. Outside Quetta, the infrastructure of the province is gradually developing but still lags far behind other parts of Pakistan. Tourism remains limited but has increased due to the exotic appeal of the province. Limited farming in the east as well as fishing along the Arabian Sea coastline are other forms of income and sustenance for the local populations. Due to the tribal lifestyle of many Baloch and Brahui, animal husbandry is important, as are trading bazaars found throughout the province.

Though the province remains largely underdeveloped, there are currently several major development projects in progress in Balochistan, including the construction of a new deep sea port at the strategically important town of Gwadar.[23] The port is projected to be the hub of an energy and trade corridor to and from China and the Central Asian republics.

Further west is the Mirani Dam[24] multipurpose project, on the Dasht River, 50 kilometres (31 mi) west of Turbat in the Makran Division. It will provide dependable irrigation supplies for the development of agriculture and add more than 35,000 km² of arable land. There is also Chinese involvement in the nearby Saindak gold and copper mining project.

Industry

Balochistan has established industrial areas in the province to create industry and jobs. These industrial estates include:

- Hub Industrial and Trading Estate (HITE) in Hub, Lasbela District

- Uthal Industrial Estate in Uthal, Lasbela District

- Windher Industrial and Trading Estate, Khuzdar District

- Dera Murad Jamali Industrial Estate, Nasirabad District

- Quetta Industrial and Trading Estate, Quetta District

- Quetta Small Industrial Zone, Quetta District

- Gadani Industrial Estate, Lasbela District

- Piahin District

Education

Notable colleges and universities

- Balochistan University of Engineering and Technology, Khuzdar

- Balochistan University of Information Technology Engineering and Management Sciences, Quetta

- Bolan Medical College, Quetta

- Iqra University, Quetta

- Lasbela University of Agriculture, Water and Marine Sciences, Lasbela

- PEARL Institute of Management & Information Technology, Quetta

- Sardar Bahadur Khan Women University, Quetta

- Sunrise School/College, Khuzdar[25]

- Tameer-e-Nau Public College, Quetta

- University of Balochistan, Quetta

Literacy and education levels

| Year | Literacy rate |

|---|---|

| 1972 | 10.1% |

| 1981 | 10.3% |

| 1998 | 26.6% |

| 2008 | 48.8% |

| Qualification | Urban | Rural | Total | Enrolment ratio(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| — | 1,568,780 | 4,997,105 | 6,565,885 | — |

| Below Primary | 237,827 | 1,149,334 | 1,387,161 | 10.00 |

| Primary | 361,760 | 1,427,173 | 1,788,933 | 15.87 |

| Middle | 325,051 | 971,437 | 1,296,488 | 17.62 |

| Matriculation | 318,932 | 846,509 | 1,165,441 | 31.88 |

| Intermediate | 132,248 | 232,865 | 365,113 | 14.13 |

| BA, BSc... degrees | 9,726 | 16,490 | 26,216 | 8.57 |

| MA, MSc... degrees | 99,303 | 133,422 | 232,725 | 8.17 |

| Diploma, Certificate... | 56,319 | 61,464 | 117,783 | 4.62 |

| Other qualifications | 27,614 | 158,411 | 186,025 | 2.83 |

See also:[28]

Notable people

Balochistan's past and present notable residents include the following:

See also

- Balochistan (Afghanistan)

- Balochistan (region)

- Balochistan honour killings

- Baloch people

- Brahui people

- Chief Minister of Balochistan

- Government of Balochistan (Pakistan)

- Gwadar

- Las Bela

- List of cities in Balochistan

- Marri-Bugti Country

- Pashtun people

- Quetta

- Balochistan (Iran)

References

- ^ a b Pakistan Balochistan Economic Report: From Periphery to Core (In Two Volumes) - Volume II: Full Report. The World Bank. May 2008. "The Balochistan population totalled 4.5 million in 1981/82 and 7.8 million in 2004/05..." "NIPS estimates that Balochistan’s population growth will slow down to 1.3 percent by 2025..."

- ^ a b "Population, Area and Density by Region/Province" (PDF). Federal Bureau of Statistics, Government of Pakistan. 1998. Retrieved 2009-07-20.

- ^ a b c "Balochistān". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2009. Retrieved December 15, 2009.

- ^ Bolan Pass - Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition

- ^ "Percentage Distribution of Households by Language Usually Spoken and Region/Province, 1998 Census" (PDF). Pakistan Statistical Year Book 2008. Federal Bureau of Statistics - Government of Pakistan. Retrieved 19 December 2009.

- ^ Hussain, Zahid (2008-09-05). "Three teenagers buried alive in 'honour killings'". Times Online. London. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

- ^ "PAKISTAN: Five women buried alive, allegedly by the brother of a minister". Asian Human Rights Commission. Retrieved 2008-08-11.

- ^ "Pakistani women buried alive 'for choosing husbands'". Telegraph. London. 2008-09-01. Retrieved 2008-09-01.

- ^ David McAlpin, Proto-Elamo-Dravidian, Philadelphia 1981

- ^ M. Longworth Dames, Balochi Folklore, Folklore, Vol. 13, No. 3 (Sep. 29, 1902), pp. 252-274

- ^ Ibn Aseer, Vol. 3, p. 17

- ^ Futuh al-Buldan, p. 384 incomplete citation, needs edition statement to identify the page

- ^ Tabqat ibn Saad, Vol. 8, p. 471

- ^ Futuh al-Buldan, p. 386 incomplete citation, needs edition statement to identify the page

- ^ Rashidun Caliphate and Hind, by Qazi Azher Mubarek Puri, published by Takhliqat , Lahore Pakistan

- ^ Tarikh al Khulfa, Vol. 1, pp. 214-215, 229

- ^ http://www.dawn.com/wps/wcm/connect/dawn-content-library/dawn/the-newspaper/letters-to-the-editor/baloch-national-identity-in-karachi

- ^ http://www.iranica.com/newsite/index.isc?Article=http://www.iranica.com/newsite/articles/unicode/v3f6/v3f6a030.html

- ^ http://panhwar.org/Article26.htm

- ^ http://panhwar.com/Article26.htm

- ^ "Provincial Accounts of Pakistan: Methodology and Estimates 1973-2000" (PDF).

- ^ http://siteresources.worldbank.org/PAKISTANEXTN/Resources/293051-1241610364594/6097548-1257441952102/balochistaneconomicreportvol2.pdf

- ^ "Gawader". Pakistan Board of Investment. Retrieved 2006-11-19.

- ^ "[[Mirani Dam]] Project". National Engineering Services Pakistan. Retrieved 2006-11-19.

{{cite web}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help) - ^ http://www.sunrisecollegekhuzdar.com

- ^ http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0014/001459/145959e.pdf

- ^ http://www.statpak.gov.pk/depts/fbs/publications/lfs2007_08/results.pdf

- ^ http://www.statpak.gov.pk/depts/pco/statistics/pop_by_province/pop_by_province.html

- ^ "Senate of Pakistan: Mir Muhammad Ali Rind".

Further reading

- Johnson, E.A., et al. (1999). Lithofacies, depositional environments, and regional stratigraphy of the lower Eocene Ghazij Formation, Balochistan, Pakistan (U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1599). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey.