Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson | |

|---|---|

| File:Andrew jackson head.gif Official White House portrait of Jackson | |

| 7th President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1829 – March 4, 1837 | |

| Vice President | John C. Calhoun (1829–1832) None (1832–1833) Martin Van Buren (1833–1837) |

| Preceded by | John Quincy Adams |

| Succeeded by | Martin Van Buren |

| Military Governor of Florida | |

| In office March 10, 1821 – November 12, 1821 | |

| President | James Monroe |

| Preceded by | José María Coppinger (Spanish territory) |

| Succeeded by | William P. Duval |

| United States Senator from Tennessee | |

| In office September 26, 1797 – April, 1798 | |

| Preceded by | William Cocke |

| Succeeded by | Daniel Smith |

| In office March 4, 1823 – October 14, 1825 | |

| Preceded by | John Williams |

| Succeeded by | Hugh Lawson White |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Tennessee's At-Large district | |

| In office December 4, 1796 – September 26, 1797 | |

| Preceded by | None – first TN Congressman (statehood) |

| Succeeded by | William C. C. Claiborne |

| Chairman of the Senate Committee on Military Affairs | |

| In office 1823–1825 | |

| Preceded by | John Williams |

| Succeeded by | William Henry Harrison |

| Personal details | |

| Born | March 15, 1767 Waxhaws area |

| Died | June 8, 1845 (aged 78) Nashville, Tennessee |

| Nationality | American |

| Political party | Democratic-Republican and Democratic |

| Spouse | Rachel Donelson Robards Jackson (1791–1828) |

| Children | (all adopted:) Andrew Jackson, Jr. Lyncoya Jackson John Samuel Donelson Daniel Smith Donelson Andrew Jackson Donelson Andrew Jackson Hutchings Carolina Butler Eliza Butler Edward Butler Anthony Butler |

| Parent(s) | Andrew Jackson, Sr. and Elisabeth Hutchinson Jackson |

| Occupation | Prosecutor, Judge, Farmer (Planter), Soldier (General) |

| Awards | Thanks of Congress |

| Signature | |

| Nickname | Old Hickory |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service | Tennessee Militia United States Army |

| Rank | Colonel Major General |

| Battles/wars | American Revolutionary War

First Seminole War |

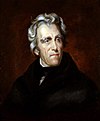

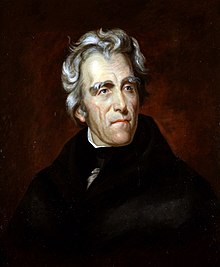

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was the seventh President of the United States (1829–1837). He was the military governor of pre-admission Florida (1821) and the commander of the American forces at the Battle of New Orleans (1815) and is an eponym of the era of Jacksonian democracy. A polarizing figure who dominated the Second Party System in the 1820s and 1830s, his political ambition and widening political participation shaped the modern Democratic Party.[1]

His legacy is now seen as mixed, as a protector of popular democracy and individual liberty for American citizens, checkered by his support for slavery and Indian removal.[2][3] Renowned for his toughness, he was nicknamed "Old Hickory".[4] As he based his career in developing Tennessee, Jackson was the first president primarily associated with the American frontier.

Early life and career

Jackson was born to Presbyterian Scotch-Irish colonists Andrew and Elizabeth Hutchinson Jackson, on March 15, 1767, two years after they had emigrated from Ireland.[5][6] Jackson's father was born in Carrickfergus, County Antrim, in Ireland around 1738.[7] He married Elizabeth, sold his land and emigrated to America in 1765. The Jacksons probably landed in Pennsylvania and made their way overland to the Scotch-Irish community in the Waxhaws region, straddling the border between North and South Carolina.[8] Jackson had two brothers, Hugh (born 1763) and Robert (born 1764). Jackson's father died in an accident in February 1767, at the age of 29, three weeks before Jackson was born. The house that Jackson's parents lived in is now preserved as the Andrew Jackson Centre and is open to the public. Jackson was born in the Waxhaws area, but his exact birth site was the subject of conflicting lore in the area. He claimed to have been born in a cabin just inside South Carolina. Controversies about Jackson's birthplace went far beyond the dispute between North and South Carolina. Because of his heroic stature and humble origins, there was much speculation.

Jackson received a sporadic education in the local "old-field" school. During the American Revolutionary War, Jackson, at age thirteen, joined a local militia as a courier.[9] His eldest brother, Hugh, died from heat exhaustion during the Battle of Stono Ferry, on June 20, 1779. Jackson and his brother Robert were captured by the British and held as prisoners; they nearly starved to death in captivity. When Jackson refused to clean the boots of a British officer, he slashed at the youth with a sword, giving him scars on his left hand and head, as well as an intense hatred for the British.[10] While imprisoned, the brothers contracted smallpox. Robert died a few days after their mother secured their release, on April 27, 1781. After his mother was assured Andrew would recover, she volunteered to nurse prisoners of war on board two ships in Charleston harbor, where there had been an outbreak of cholera. She died from the disease in November 1781, and was buried in an unmarked grave, leaving Jackson an orphan at age 14.[10] Jackson's entire immediate family had died from hardships during the war; Jackson blamed the British.

Jackson was the last U.S. President to have been a veteran of the American Revolution.

In 1781, Jackson worked for a time in a saddle-maker's shop.[11] Later, he taught school and studied law in Salisbury, North Carolina. In 1787, he was admitted to the bar, and moved to Jonesborough, in what was then the Western District of North Carolina. This area later became the Southwest Territory (1790), the precursor to the state of Tennessee.

Though his legal education was scanty, Jackson knew enough to be a country lawyer on the frontier. Since he was not from a distinguished family, he had to make his career by his own merits; soon he began to prosper in the rough-and-tumble world of frontier law. Most of the actions grew out of disputed land-claims, or from assault and battery. In 1788, he was appointed Solicitor of the Western District and held the same position in the government of the Territory South of the River Ohio after 1791.

In 1796, Jackson was a delegate to the Tennessee constitutional convention. When Tennessee achieved statehood that year, Jackson was elected its U.S. Representative. In 1797, he was elected U.S. Senator as a Democratic-Republican. He resigned within a year. In 1798, he was appointed a judge of the Tennessee Supreme Court, serving until 1804.[12]

Besides his legal and political career, Jackson prospered as a slave owner, planter, and merchant. In 1803 he owned a lot, and built a home and the first general store in Gallatin, Tennessee. In 1804, he acquired the Hermitage, a 640-acre (2.6 km2) plantation in Davidson County, near Nashville, Tennessee. Jackson later added 360 acres (1.5 km2) to the farm. The plantation eventually grew to 1,050 acres (425 ha). The primary crop was cotton, grown by enslaved workers. Jackson started with nine slaves, by 1820 he held as many as 44, and later held up to 150 slaves. Throughout his lifetime Jackson may have owned as many as 300 slaves.[13][14]

Jackson was a major land speculator in West Tennessee after he had negotiated the sale of the land from the Chickasaw Nation in 1818 (termed the Jackson Purchase) and was one of the three original investors who founded Memphis, Tennessee in 1819 (see History of Memphis, Tennessee).[15]

Military career

War of 1812

Jackson was appointed commander of the Tennessee militia in 1801, with the rank of colonel.

During the War of 1812, Tecumseh incited the "Red Stick" Creek Indians of northern Alabama and Georgia to attack white settlements. Four hundred settlers were killed in the Fort Mims Massacre. In the resulting Creek War, Jackson commanded the American forces, which included Tennessee militia, U.S. regulars, and Cherokee, Choctaw, and Southern Creek Indians.

Jackson defeated the Red Stick Creeks at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend in 1814. Eight hundred "Red Sticks" were killed, but Jackson spared chief William Weatherford. Sam Houston and David Crockett served under Jackson in this campaign. After the victory, Jackson imposed the Treaty of Fort Jackson upon both the Northern Creek enemies and the Southern Creek allies, wresting twenty million acres (81,000 km²) from all Creeks for white settlement. Jackson was appointed Major General after this action.

Jackson's service in the War of 1812 against the United Kingdom was conspicuous for bravery and success. When British forces threatened New Orleans, Jackson took command of the defenses, including militia from several western states and territories. He was a strict officer but was popular with his troops. It was said he was "tough as old hickory" wood on the battlefield, which gave him his nickname. In the Battle of New Orleans on January 8, 1815, Jackson's 5,000 soldiers won a victory over 7,500 British. At the end of the day, the British had 2,037 casualties: 291 dead (including three senior generals), 1,262 wounded, and 484 captured or missing. The Americans had 71 casualties: 13 dead, 39 wounded, and 19 missing.[16]

The war, and especially this victory, made Jackson a national hero. He received the Thanks of Congress and a gold medal by resolution of February 27, 1815. Alexis de Tocqueville later commented in Democracy in America that Jackson "...was raised to the Presidency, and has been maintained there, solely by the recollection of a victory which he gained, twenty years ago, under the walls of New Orleans."

First Seminole War

Jackson served in the military again during the First Seminole War. He was ordered by President James Monroe in December 1817 to lead a campaign in Georgia against the Seminole and Creek Indians. Jackson was also charged with preventing Spanish Florida from becoming a refuge for runaway slaves. Critics later alleged that Jackson exceeded orders in his Florida actions. His directions were to "terminate the conflict."[17] Jackson believed the best way to do this was to seize Florida. Before going, Jackson wrote to Monroe, "Let it be signified to me through any channel... that the possession of the Floridas would be desirable to the United States, and in sixty days it will be accomplished."[18] Monroe gave Jackson orders that were purposely ambiguous, sufficient for international denials.

The Seminoles attacked Jackson's Tennessee volunteers. The Seminoles' attack, however, left their villages vulnerable, and Jackson burned them and the crops. He found letters that indicated that the Spanish and British were secretly assisting the Indians. Jackson believed that the United States could not be secure as long as Spain and the United Kingdom encouraged Indians to fight, and argued that his actions were undertaken in self-defense. Jackson captured Pensacola, Florida, with little more than some warning shots, and deposed the Spanish governor. He captured and then tried and executed two British subjects, Robert Ambrister and Alexander Arbuthnot, who had been supplying and advising the Indians. Jackson's action also struck fear into the Seminole tribes as word spread of his ruthlessness in battle (Jackson was known as "Sharp Knife").

The executions, and Jackson's invasion of territory belonging to Spain, a country with which the U.S. was not at war, created an international incident. Many in the Monroe administration called for Jackson to be censured. Jackson's actions were defended by Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, an early believer in Manifest Destiny. When the Spanish minister demanded a "suitable punishment" for Jackson, Adams wrote back, "Spain must immediately [decide] either to place a force in Florida adequate at once to the protection of her territory ... or cede to the United States a province, of which she retains nothing but the nominal possession, but which is, in fact ... a post of annoyance to them."[19] Adams used Jackson's conquest, and Spain's own weakness, to get Spain to cede Florida to the United States by the Adams-Onís Treaty. Jackson was subsequently named military governor and served from March 10, 1821, to December 31, 1821.

Election of 1824

The Tennessee legislature nominated Jackson for President in 1822. It also elected him U.S. Senator again.

By 1824, the Democratic-Republican Party had become the only functioning national party. Its Presidential candidates had been chosen by an informal Congressional nominating caucus, but this had become unpopular. In 1824, most of the Democratic-Republicans in Congress boycotted the caucus. Those who attended backed Treasury Secretary William H. Crawford for President and Albert Gallatin for Vice President. A Pennsylvanian convention nominated Jackson for President a month later, stating that the irregular caucus ignored the "voice of the people" and was a "vain hope that the American people might be thus deceived into a belief that he [Crawford] was the regular democratic candidate."[20] Gallatin criticized Jackson as "an honest man and the idol of the worshippers of military glory, but from incapacity, military habits, and habitual disregard of laws and constitutional provisions, altogether unfit for the office."[21]

Besides Jackson and Crawford, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams and House Speaker Henry Clay were also candidates. Jackson received the most popular votes (but not a majority, and four states had no popular ballot). The Electoral votes were split four ways, with Jackson having a plurality. Since no candidate received a majority, the election was decided by the House of Representatives, which chose Adams. Jackson supporters denounced this result as a "corrupt bargain" because Clay gave his state's support to Adams, and subsequently Adams appointed Clay as Secretary of State. As none of Kentucky's electors had initially voted for Adams, and Jackson had won the popular vote, it appeared that Henry Clay had violated the will of the people and substituted his own judgment in return for personal political favors. Jackson's defeat burnished his political credentials, however; many voters believed the "man of the people" had been robbed by the "corrupt aristocrats of the East."

Election of 1828

Jackson resigned from the Senate in October 1825, but continued his quest for the Presidency. The Tennessee legislature again nominated Jackson for President. Jackson attracted Vice President John C. Calhoun, Martin Van Buren, and Thomas Ritchie into his camp (Van Buren and Ritchie were previous supporters of Crawford). Van Buren, with help from his friends in Philadelphia and Richmond, revived the old Republican Party, gave it a new name as the Democratic Party, "restored party rivalries," and forged a national organization of durability.[22] The Jackson coalition handily defeated Adams in 1828.

During the election, Jackson's opponents referred to him as a "jackass". Jackson liked the name and used the jackass as a symbol for a while, but it died out. However, it later became the symbol for the Democratic Party when cartoonist Thomas Nast popularized it.[23]

The campaign was very much a personal one. Although neither candidate personally campaigned, their political followers organized many campaign events. Both candidates were rhetorically attacked in the press, which reached a low point when the press accused Jackson's wife Rachel of bigamy. Though the accusation was true, as were most personal attacks leveled against him during the campaign, it was based on events that occurred many years prior (1791 to 1794). Jackson said he would forgive those who insulted him, but he would never forgive the ones who attacked his wife. Rachel died suddenly on December 22, 1828, before his inauguration, and was buried on Christmas Eve.

Inauguration

Jackson was the first President to invite the public to attend the White House ball honoring his first inauguration. Many poor people came to the inaugural ball in their homemade clothes. The crowd became so large that Jackson's guards could not hold them out of the White House. The White House became so crowded with people that dishes and decorative pieces in the White House began to break. Some people stood on good chairs in muddied boots just to get a look at the President. The crowd had become so wild that the attendants poured punch in tubs and put it on the White House lawn to lure people out of the White House. Jackson's raucous populism earned him the nickname King Mob.

Election of 1832

In the 1832 presidential election, Jackson easily won reelection as the candidate of the Democratic Party against Henry Clay, of the National Republican Party, and William Wirt, of the Anti-Masonic Party. Jackson jettisoned Vice President John C. Calhoun because of his support for nullification and involvement in the Petticoat affair, replacing him with longtime confidant Martin Van Buren of New York.

Presidency 1829–1837

| The Jackson cabinet | ||

|---|---|---|

| Office | Name | Term |

| President | Andrew Jackson | 1829–1837 |

| Vice President | John C. Calhoun | 1829–1832 |

| None | 1832–1833 | |

| Martin Van Buren | 1833–1837 | |

| Secretary of State | Martin Van Buren | 1829–1831 |

| Edward Livingston | 1831–1833 | |

| Louis McLane | 1833–1834 | |

| John Forsyth | 1834–1837 | |

| Secretary of the Treasury | Samuel D. Ingham | 1829–1831 |

| Louis McLane | 1831–1833 | |

| William J. Duane | 1833 | |

| Roger B. Taney | 1833–1834 | |

| Levi Woodbury | 1834–1837 | |

| Secretary of War | John H. Eaton | 1829–1831 |

| Lewis Cass | 1831–1836 | |

| Attorney General | John M. Berrien | 1829–1831 |

| Roger B. Taney | 1831–1833 | |

| Benjamin F. Butler | 1833–1837 | |

| Postmaster General | William T. Barry | 1829–1835 |

| Amos Kendall | 1835–1837 | |

| Secretary of the Navy | John Branch | 1829–1831 |

| Levi Woodbury | 1831–1834 | |

| Mahlon Dickerson | 1834–1837 | |

Federal debt

In 1835, Jackson managed to reduce the federal debt to only $33,733.05, the lowest it had been since the first fiscal year of 1791.[24] By implementing a tariff and limits on terms of elected officials President Jackson remains the only president in United States history to have paid off the national debt.[25] However, this accomplishment was short lived. A severe depression from 1837 to 1844 caused a tenfold increase in national debt within its first year.[26]

Electoral College

Jackson repeatedly called for the abolition of the Electoral College by constitutional amendment in his annual messages to Congress as President.[27][28] In his third annual message to Congress, he expressed the view "I have heretofore recommended amendments of the Federal Constitution giving the election of President and Vice-President to the people and limiting the service of the former to a single term. So important do I consider these changes in our fundamental law that I can not, in accordance with my sense of duty, omit to press them upon the consideration of a new Congress."[29] The institution Jackson railed against remains to the present day.

Spoils system

When Jackson became President, he implemented the theory of rotation in office, declaring it "a leading principle in the republican creed."[27] He believed that rotation in office would prevent the development of a corrupt bureaucracy. To strengthen party loyalty, Jackson's supporters wanted to give the posts to party members. In practice, this meant replacing federal employees with friends or party loyalists.[30] However, the effect was not as drastic as expected or portrayed. By the end of his term, Jackson dismissed less than twenty percent of the Federal employees at the start of it.[31] While Jackson did not start the "spoils system," he did indirectly encourage its growth for many years to come.

Opposition to the National Bank

The Second Bank of the United States was authorized for a twenty year period during James Madison's tenure in 1816. As President, Jackson worked to rescind the bank's federal charter. In Jackson's veto message (written by George Bancroft), the bank needed to be abolished because:

- It concentrated the nation's financial strength in a single institution.

- It exposed the government to control by foreign interests.

- It served mainly to make the rich richer.

- It exercised too much control over members of Congress.

- It favored northeastern states over southern and western states.

- Banks are controlled by a few select families.

- Banks have a long history of instigating wars between nations, forcing them to borrow funding to pay for them.

Following Jefferson, Jackson supported an "agricultural republic" and felt the Bank improved the fortunes of an "elite circle" of commercial and industrial entrepreneurs at the expense of farmers and laborers. After a titanic struggle, Jackson succeeded in destroying the Bank by vetoing its 1832 re-charter by Congress and by withdrawing U.S. funds in 1833. (See Banking in the Jacksonian Era)

The bank's money-lending functions were taken over by the legions of local and state banks that sprang up. This fed an expansion of credit and speculation. At first, as Jackson withdrew money from the Bank to invest it in other banks, land sales, canal construction, cotton production, and manufacturing boomed.[32] However, due to the practice of banks issuing paper banknotes that were not backed by gold or silver reserves, there was soon rapid inflation and mounting state debts.[33] Then, in 1836, Jackson issued the Specie Circular, which required buyers of government lands to pay in "specie" (gold or silver coins). The result was a great demand for specie, which many banks did not have enough of to exchange for their notes. These banks collapsed.[32] This was a direct cause of the Panic of 1837, which threw the national economy into a deep depression. It took years for the economy to recover from the damage.

The U.S. Senate censured Jackson on March 28, 1834, for his action in removing U.S. funds from the Bank of the United States. When the Jacksonians had a majority in the Senate, the censure was expunged.

Nullification crisis

Another notable crisis during Jackson's period of office was the "Nullification Crisis", or "secession crisis," of 1828 – 1832, which merged issues of sectional strife with disagreements over tariffs. Critics alleged that high tariffs (the "Tariff of Abominations") on imports of common manufactured goods made in Europe made those goods more expensive than ones from the northern U.S., raising the prices paid by planters in the South. Southern politicians argued that tariffs benefited northern industrialists at the expense of southern farmers.

The issue came to a head when Vice President Calhoun, in the South Carolina Exposition and Protest of 1828, supported the claim of his home state, South Carolina, that it had the right to "nullify"—declare void—the tariff legislation of 1828, and more generally the right of a state to nullify any Federal laws that went against its interests. Although Jackson sympathized with the South in the tariff debate, he was also a strong supporter of a strong union, with effective powers for the central government. Jackson attempted to face down Calhoun over the issue, which developed into a bitter rivalry between the two men.

Particularly notable was an incident at the April 13, 1830, Jefferson Day dinner, involving after-dinner toasts. Robert Hayne began by toasting to "The Union of the States, and the Sovereignty of the States." Jackson then rose, and in a booming voice added "Our federal Union: It must be preserved!" – a clear challenge to Calhoun. Calhoun clarified his position by responding "The Union: Next to our Liberty, the most dear!"[34]

The next year, Calhoun and Jackson broke apart politically from one another. Around this time, the Petticoat affair caused further resignations from Jackson's cabinet, leading to its reorganization as the "Kitchen Cabinet". Martin Van Buren, despite resigning as Secretary of State, played a leading role in the new unofficial cabinet.[35] At the first Democratic National Convention, privately engineered by members of the Kitchen Cabinet,[36] Van Buren replaced Calhoun as Jackson's running mate. In December 1832, Calhoun resigned as Vice President to become a U.S. Senator for South Carolina.

In response to South Carolina's nullification claim, Jackson vowed to send troops to South Carolina to enforce the laws. In December 1832, he issued a resounding proclamation against the "nullifiers," stating that he considered "the power to annul a law of the United States, assumed by one State, incompatible with the existence of the Union, contradicted expressly by the letter of the Constitution, unauthorized by its spirit, inconsistent with every principle on which it was founded, and destructive of the great object for which it was formed." South Carolina, the President declared, stood on "the brink of insurrection and treason," and he appealed to the people of the state to reassert their allegiance to that Union for which their ancestors had fought. Jackson also denied the right of secession: "The Constitution... forms a government not a league... To say that any State may at pleasure secede from the Union is to say that the United States is not a nation."[37]

Jackson asked Congress to pass a "Force Bill" explicitly authorizing the use of military force to enforce the tariff, but its passage was delayed until protectionists led by Clay agreed to a reduced Compromise Tariff. The Force Bill and Compromise Tariff passed on March 1, 1833, and Jackson signed both. The South Carolina Convention then met and rescinded its nullification ordinance. The Force Bill became moot because it was no longer needed.

Indian removal

Perhaps the most controversial aspect of Jackson's presidency was his policy regarding American Indians, which involved the ethnic cleansing of several Indian tribes.[38][39] Jackson was a leading advocate of a policy known as Indian removal. Jackson had been negotiating treaties and removal policies with Indian leaders for years before his election as president. Many tribes and portions of tribes had been removed to Arkansas Territory and further west of the Mississippi River without the suffering and tragedies of what later became known as the Trail of Tears. Further, many white Americans advocated total extermination of the "savages," particularly those who had experienced frontier wars. Jackson's support of removal policies can be best understood by examination of those prior cases he had personally negotiated, rather than those in post-presidential years. Nevertheless, Jackson is often held responsible for all that took place in the 1830s.

In his December 8, 1829, First Annual Message to Congress, Jackson stated:

This emigration should be voluntary, for it would be as cruel as unjust to compel the aborigines to abandon the graves of their fathers and seek a home in a distant land. But they should be distinctly informed that if they remain within the limits of the States they must be subject to their laws. In return for their obedience as individuals they will without doubt be protected in the enjoyment of those possessions which they have improved by their industry.[40]

Before his election as president, Jackson had been involved with the issue of Indian removal for over ten years. The removal of the Native Americans to the west of the Mississippi River had been a major part of his political agenda in both the 1824 and 1828 presidential elections.[41] After his election he signed the Indian Removal Act into law in 1830. The Act authorized the President to negotiate treaties to buy tribal lands in the east in exchange for lands further west, outside of existing U.S. state borders.

While frequently frowned upon in the North, and opposed by Jeremiah Evarts and Theodore Frelinghuysen, the Removal Act was popular in the South, where population growth and the discovery of gold on Cherokee land had increased pressure on tribal lands. The state of Georgia became involved in a contentious jurisdictional dispute with the Cherokees, culminating in the 1832 U.S. Supreme Court decision (Worcester v. Georgia), which ruled that Georgia could not impose its laws upon Cherokee tribal lands. Jackson is often quoted (regarding the decision) as having said, "John Marshall has made his decision, now let him enforce it!" Whether he said it is disputed.[42]

In any case, Jackson used the Georgia crisis to pressure Cherokee leaders to sign a removal treaty. A small faction of Cherokees led by John Ridge negotiated the Treaty of New Echota with Jackson's representatives. Ridge was not a recognized leader of the Cherokee Nation, and this document was rejected by most Cherokees as illegitimate.[43] Over 15,000 Cherokees signed a petition in protest of the proposed removal; the list was ignored by the Supreme Court and the U.S. legislature, in part due to unfortunate and tragic delays and timing.[44] The treaty was enforced by Jackson's successor, Van Buren, who ordered 7,000 armed troops to remove the Cherokees. Due to the infighting between political factions, many Cherokees thought their appeals were still being considered until troops arrived.[45] This abrupt and forced removal resulted in the deaths of over 4,000 Cherokees on the "Trail of Tears".

By the 1830s, under constant pressure from settlers, each of the five southern tribes had ceded most of its lands, but sizable self-government groups lived in Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and Florida. All of these (except the Seminoles) had moved far in the coexistence with whites, and they resisted suggestions that they should voluntarily remove themselves. Their nonviolent methods earned them the title the Five Civilized Tribes.[46]

In all, more than 45,000 American Indians were relocated to the West during Jackson's administration. A few Cherokees escaped forced relocation, or walked back afterwards, escaping to the high Smoky Mountains along the North Carolina and Tennessee border.[47]

During the Jacksonian era, the administration bought about 100 million acres (400,000 km²) of Indian land for about $68 million and 32 million acres (130,000 km²) of western land. Jackson was criticized at the time for his role in these events, and the criticism has grown over the years. Remini characterizes the Indian Removal era as "one of the unhappiest chapters in American history."[48]

Attack and assassination attempt

The first attempt to do bodily harm to a President was against Jackson. Jackson ordered the dismissal of Robert B. Randolph from the Navy for embezzlement. On May 6, 1833, Jackson sailed on USS Cygnet to Fredericksburg, Virginia, where he was to lay the cornerstone on a monument near the grave of Mary Ball Washington, George Washington's mother. During a stopover near Alexandria, Virginia, Randolph appeared and struck the President. He then fled the scene with several members of Jackson's party chasing him, including the well known writer Washington Irving. Jackson decided not to press charges.[11]

On January 30, 1835, what is believed to be the first attempt to kill a sitting President of the United States occurred just outside the United States Capitol. When Jackson was leaving the Capitol out of the East Portico after the funeral of South Carolina Representative Warren R. Davis, Richard Lawrence, an unemployed and deranged housepainter from England, either burst from a crowd or stepped out from hiding behind a column and aimed a pistol at Jackson, which misfired. Lawrence then pulled out a second pistol, which also misfired. It has been postulated that moisture from the humid weather contributed to the double misfiring.[49] Lawrence was then restrained, with legend saying that Jackson attacked Lawrence with his cane, prompting his aides to restrain him. Others present, including David Crockett, restrained and disarmed Lawrence.

Richard Lawrence gave the doctors several reasons for the shooting. He had recently lost his job painting houses and somehow blamed Jackson. He claimed that with the President dead, "money would be more plenty" (a reference to Jackson's struggle with the Bank of the United States) and that he "could not rise until the President fell." Finally, he informed his interrogators that he was a deposed English King—specifically, Richard III, dead since 1485—and that Jackson was merely his clerk. He was deemed insane, institutionalized, and never punished for his assassination attempt.

Afterward, due to curiosity concerning the double misfires, the pistols were tested and retested. Each time they performed perfectly. When these results were known, many believed that Jackson had been protected by the same Providence that had protected the young nation. This national pride was a large part of the Jacksonian cultural myth fueling American expansion in the 1830s.

Judicial appointments

In total Jackson appointed 24 federal judges: six Justices to the Supreme Court of the United States and eighteen judges to the United States district courts.

Supreme Court appointments

- John McLean – 1830.

- Henry Baldwin – 1830.

- James Moore Wayne – 1835.

- Roger Brooke Taney (Chief Justice) – 1836.

- Philip Pendleton Barbour – 1836.

- John Catron – 1837.

Major Supreme Court cases

- Cherokee Nation v. Georgia – 1831.

- Worcester v. Georgia – 1832.

- Charles River Bridge v. Warren Bridge – 1837.

States admitted to the Union

Family and personal life

Shortly after Jackson first arrived in Nashville in 1788, he lived as a boarder with Rachel Stockley Donelson, the widow of John Donelson. Here Jackson became acquainted with their daughter, Rachel Donelson Robards. At the time, Rachel Robards was in an unhappy marriage with Captain Lewis Robards, a man subject to irrational[dubious – discuss] fits of jealous rage. Due to Lewis Robards' temperament, the two were separated in 1790. According to Jackson, he married Rachel after hearing that Robards had obtained a divorce. However, the divorce had never been completed, making Rachel's marriage to Jackson technically bigamous and therefore invalid. After the divorce was officially completed, Rachel and Jackson remarried in 1794.[50] However, there is evidence that Donelson had been living with Jackson and referred to herself as Mrs. Jackson before the petition for divorce was ever made.[51] It was not uncommon on the frontier for relationships to be formed and dissolved unofficially, as long as they were recognized by the community.

The controversy surrounding their marriage remained a sore point for Jackson, who deeply resented attacks on his wife's honor. Jackson fought 13 duels, many nominally over his wife's honor.[citation needed] Charles Dickinson, the only man Jackson ever killed in a duel, had been goaded into angering Jackson by Jackson's political opponents. In the duel, fought over a horse-racing debt and an insult to his wife on May 30, 1806, Dickinson shot Jackson in the ribs before Jackson returned the fatal shot; Jackson allowed Dickinson to shoot first, knowing him to be an excellent shot, and as his opponent reloaded, Jackson shot, even as the bullet lodged itself in his chest. The bullet that struck Jackson was so close to his heart that it could never be safely removed. Jackson had been wounded so frequently in duels that it was said he "rattled like a bag of marbles."[52] At times he coughed up blood, and he experienced considerable pain from his wounds for the rest of his life.

Rachel died of a heart attack on December 22, 1828, two weeks after her husband's victory in the election and two months before Jackson taking office as President. Jackson blamed John Quincy Adams for Rachel's death because the marital scandal was brought up in the election of 1828. He felt that this had hastened her death and never forgave Adams.

Jackson had two adopted sons, Andrew Jackson Jr., the son of Rachel's brother Severn Donelson, and Lyncoya, a Creek Indian orphan adopted by Jackson after the Creek War. Lyncoya died of tuberculosis in 1828, at the age of sixteen.[53]

The Jacksons also acted as guardians for eight other children. John Samuel Donelson, Daniel Smith Donelson and Andrew Jackson Donelson were the sons of Rachel's brother Samuel Donelson, who died in 1804. Andrew Jackson Hutchings was Rachel's orphaned grand nephew. Caroline Butler, Eliza Butler, Edward Butler, and Anthony Butler were the orphaned children of Edward Butler, a family friend. They came to live with the Jacksons after the death of their father.

The widower Jackson invited Rachel's niece Emily Donelson to serve as host at the White House. Emily was married to Andrew Jackson Donelson, who acted as Jackson's private secretary and in 1856 would run for Vice President on the American Party ticket. The relationship between the President and Emily became strained during the Petticoat affair, and the two became estranged for over a year. They eventually reconciled and she resumed her duties as White House host. Sarah Yorke Jackson, the wife of Andrew Jackson Jr., became cohost of the White House in 1834. It was the only time in history when two women simultaneously acted as unofficial First Lady. Sarah took over all hosting duties after Emily died from tuberculosis in 1836. Jackson used Rip Raps as a retreat, visiting between August 19, 1829 through August 16, 1835.[54]

Jackson remained influential in both national and state politics after retiring to The Hermitage in 1837. Though a slave-holder, Jackson was a firm advocate of the federal union of the states, and declined to give any support to talk of secession.

Jackson was a lean figure standing at 6 feet, 1 inch (1.85 m) tall, and weighing between 130 and 140 pounds (64 kg) on average. Jackson also had an unruly shock of red hair, which had completely grayed by the time he became president at age 61. He had penetrating deep blue eyes. Jackson was one of the more sickly presidents, suffering from chronic headaches, abdominal pains, and a hacking cough, caused by a musket ball in his lung that was never removed, that often brought up blood and sometimes made his whole body shake. After retiring to Nashville, he enjoyed eight years of retirement and died at The Hermitage on June 8, 1845, at the age of 78, of chronic tuberculosis, dropsy, and heart failure.

In his will, Jackson left his entire estate to his adopted son, Andrew Jackson Jr., except for specifically enumerated items that were left to various other friends and family members. About a year after retiring the presidency,[55] Jackson became a member of the First Presbyterian Church in Nashville.

Jackson on U.S. Postage

Few American presidents ever appear on US Postage more than the usual two or three times, and Andrew Jackson is one of them. Jackson died in 1845, but the U.S. Post Office did not release a Postage stamp in his honor until 18 years after his death, with the issue of 1863, a 2-cent black issue, commonly referred to by collectors as the 'Black Jack', displayed above. In contrast, the first Warren Harding stamp was released only one month after his death, Lincoln, one year exactly. As Jackson was a controversial figure in his day there is speculation that officials in Washington chose to wait a period of time before issuing a stamp with his portrait. In all, Jackson has appeared on thirteen different US postage stamps, more than that of most US presidents and second only to the number of times Washington, Franklin and Lincoln have appeared.[56][57] During the American Civil War the Confederate government also issued two Confederate postage stamps bearing Jackson's portrait, one a 2-cent red stamp and the other a 2-cent green stamp, both issued in 1863.[58]

|  |  |

Jackson also appears on other U.S. Postage stamps of the 19th and 20th centuries. In all, Jackson appears on twelve US Postage stamps to date.

Memorials

- Jackson's portrait appears on the United States twenty-dollar bill. He has appeared on $5, $10, $50, and $10,000 bills in the past, as well as a Confederate $1,000 bill.

- Jackson's image is on the Black Jack and many other postage stamps. These include the Prominent Americans series (1965–1978) 10¢ stamp.

- Memorials to Jackson include a set of four identical equestrian statues located in different parts of the United States. One is in Jackson Square in New Orleans. Another is in Nashville on the grounds of the Tennessee State Capitol. A third is in Washington, D.C. near the White House. The fourth is in Downtown Jacksonville, Florida. Equestrian statues of Jackson have also been erected elsewhere, including one with Jackson on horseback together with seated figures of James K. Polk and Andrew Johnson on the State Capitol grounds in Raleigh, North Carolina.

- Numerous counties and cities are named after him, including Jacksonville, Florida; Jackson, Louisiana; Jackson, Michigan; Jackson, Mississippi; Jackson County, Mississippi; Jackson, Missouri; Jackson County, Oregon; Jacksonville, North Carolina; Jackson, Tennessee; Jackson County, Florida; Jackson Parish, Louisiana; Jackson County, Missouri; and Jackson County, Ohio.

- Andrew Jackson State Park is located on the site of his birthplace in Lancaster County, South Carolina. The park features a museum about his childhood, and a bronze statue of Jackson on horseback by sculptor Anna Hyatt Huntington.

- In Nashville, Old Hickory Boulevard, named for Jackson, is a historic road that encircles the city. Originally the road, aided by ferries, formed an unbroken loop around the city. Today, it is interrupted by lakes and rerouted sections. It is the longest road in the city.

- Two suburbs in the eastern part of Nashville, near The Hermitage, are named for Jackson and his home: Old Hickory, Tennessee, and Hermitage, Tennessee.

- A main thoroughfare in Hermitage, Tennessee is named Andrew Jackson Parkway. Several roads in the same area have names associated with Jackson, such as Andrew Jackson Way, Andrew Jackson Place, Rachel Donelson Pass, Rachel's Square Drive, Rachel's Way, Rachel's Court, Rachel's Trail, and Andrew Donelson Drive.

- One of the most popular lakes in middle Tennessee is Old Hickory Lake.

- Andrew Jackson High School, in Lancaster County, SC, is named after him and uses the title of "Hickory Log" for its Annual photo book.

- The section of U.S. Route 74 between Charlotte, North Carolina and Wilmington, North Carolina is named the Andrew Jackson Highway.

- The U.S. Army installation Fort Jackson in Columbia, South Carolina, is named in his honor.

- Fort Jackson, built before the Civil War on the Mississippi River for the defense of New Orleans, was named in his honor.

- USS Andrew Jackson (SSBN-619), a Lafayette-class nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine, which served from 1963 to 1989.

- Jackson Park, the third-largest park in Chicago, is named for him.

- Jackson Park, a public golf course in Seattle, Washington is named for him.

- Andrew Jackson Centre, the Andrew Jackson Cottage and US Rangers Centre is a "traditional thatched Ulster–Scots farmhouse built in 1750s" and "includes the home of Jackson's parents. It has been restored to its original state."[6]

See also

- Second Party System

- List of Presidents of the United States

- List of US Presidents on US currency

- US Presidents on US postage stamps

References

- ^ Wilentz, Sean. Andrew Jackson (2005), p. 8, 35.

- ^ Finkelman, Paul (2006). "Jackson, Andrew (1767–1845)," in Encyclopedia of American Civil Liberties, 3 vols., Routledge (CRC Press), ISBN 978-0-415-94342-0, vol. 2 (G-Q), p. 832–833.

- ^ See also: Remini 1988, The Legacy of Andrew Jackson: Essays on Democracy, Indian Removal, and Slavery.

- ^ Hargreaves, Mary (2010-12-08). "John Quincy Adams: Campaigns and Elections". American President: An Online Reference Resource. University of Virginia.

In a masterstroke of popular politics, the Jacksonians made good use of the general's nickname, Old Hickory. He had earned the name because he was reputed to be as tough as hickory wood.

- ^ "Andrew Jackson". Information Services Branch, State Library of North Carolina.

- ^ a b "Andrew Jackson Cottage and US Rangers Centre". Northern Ireland Tourist Board.

- ^ Gullan, Harold I. (c2004). First fathers: the men who inspired our Presidents. Hoboken, N.J. : J: John Wiley & Sons. pp. xii, 308 p. : ill., 25 cm. ISBN 0471465976. OCLC 53090968. LCCN 20-3. Retrieved January 14, 2010.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Booraem, Hendrik (2001) Young Hickory : The Making of Andrew Jackson p.9

- ^ Remini 1:15-17

- ^ a b Remini 1:13

- ^ a b Paletta, Lu Ann (1988). The World Almanac of Presidential Facts. World Almanac Books. ISBN 0345348885.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Jackson, Andrew, (1767 – 1845),. Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- ^ Remini (2000), p.51 cites 1820 census; mentions later figures up to 150 without noting a source.

- ^ "Hermitage". Thehermitage.com. Retrieved 2010-09-06.

- ^ Jackson Purchase in the Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture

- ^ Remini, Robert V. (1999) The battle of New Orleans, New York: Penguin Books. p. 285

- ^ Remini, 118.

- ^ Ogg, 66.

- ^ Johnson, Allen (1920). "Jefferson and His Colleagues". Retrieved 2006-10-11.

- ^ Rutland, Robert Allen (1995). The Democrats: From Jefferson to Clinton. University of Missouri Press. pp. 48–49. ISBN 0826210341.

- ^ Adams, Henry. The Life of Albert Gallatin (1879), 599.

- ^ Rutland, Robert Allen (1995). The Democrats: From Jefferson to Clinton. University of Missouri Press. pp. 55–56. ISBN 0826210341.

- ^ "Nickels, Ilona; "How did Republicans pick the elephant, and Democrats the donkey, to represent their parties?"; "Capitol Questions" feature at c-span.com; September 5, 2000". C-span.org. Retrieved 2010-09-06.

- ^ "Historical Debt Outstanding - Annual 1791 - 1849". Public Debt Reports. Treasury Direct. Retrieved 2007-11-25.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Andrew Jackson". New York Times / Gale Encyclopedia of Biography. Retrieved 19 December 2010.

- ^ Watkins, Thayer. "The Depression of 1837-1844". San José State University Department of Economics. Retrieved 2007-11-25.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b "Andrew Jackson's First Annual Message to Congress". The American Presidency Project. Retrieved 2008-03-14.

- ^ "Andrew Jackson's Second Annual Message to Congress". The American Presidency Project. Retrieved 2008-03-14.

- ^ "Andrew Jackson's Third Annual Message to Congress". The American Presidency Project. Retrieved 2008-03-14.

- ^ The Spoils System, as the rotation in office system was called, did not originate with Jackson. It originated with New York governors in the late 18th and early 19th centuries (most notably George Clinton and DeWitt Clinton). Thomas Jefferson brought it to the Executive Branch when he replaced Federalist office-holders after becoming President. The Spoils System versus the Merit System. Retrieved on 2006-11-21.

- ^ Jacksonian Democracy: The Presidency of Andrew Jackson. Retrieved on 2006-11-21.

- ^ a b Digital History, Steven Mintz. "Digital History". Digitalhistory.uh.edu. Retrieved 2010-09-06.

- ^ "Sparknotes". Sparknotes. Retrieved 2010-09-06.

- ^ Ogg, 164.

- ^ Martin Van Buren biography at Encyclopedia Americana

- ^ Parton, James (2006). Life of Andrew Jackson. Vol. 3. Kessinger Publishing. pp. 381–385. ISBN 1428639292.. First published in 1860.

- ^ Syrett, 36. See also: "President Jackson's Proclamation Regarding Nullification, December 10, 1832". Retrieved 2006-08-10.

- ^ In particular, see Schama (2008) p. 325-326

- ^ For an attack on Jackson see Cave (2003). 65(6): 1330–1353. For a defense see Remini (2001).

- ^ "Andrew Jackson: First Annual Message". Presidency.ucsb.edu. Retrieved 2008-11-01.

- ^ Remini,"Andrew Jackson and the Course of American Freedom, 1822–1832" pp. 117, 200

- ^ Cave (2003); Remini (1988).

- ^ "Historical Documents - The Indian Removal Act of 1830". Historicaldocuments.com. Retrieved 2008-11-01.

- ^ "PBS.org". PBS.org. Retrieved 2010-09-06.

- ^ "Indian Removal". Synaptic.bc.ca. Retrieved 2010-09-06.

- ^ PBS: Judgement Day. “Indian removal.” PBS.org . Retrieved January 12, 2008.

- ^ "Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians - History". Cherokee-nc.com. Retrieved 2010-09-06.

- ^ Remini (2001).

- ^ Jon Grinspan. "Trying to Assassinate Andrew Jackson". Retrieved November 11, 2008.

- ^ Remini, 17–25

- ^ Meacham, Jon (2008). American Lion: Andrew Jackson in the White House. New York: Random House. pp. 22–23. ISBN 978-1-4000-6325-3.

- ^ Wallace, Chris (2005). Character : Profiles in Presidential Courage. New York, NY: Rugged Land. ISBN 1-59071-054-1.

- ^ Remini 1:194

- ^ Meacham, page 109; 315

- ^ Wilentz, Sean (2005). Andrew Jackson. Macmillan. p. 160.

- ^ Scotts US Stamp Catalogue

- ^ Smithsonian National Postal Museum

- ^ Smithsonian National Postal Museum

Secondary sources

Biography

- Brands, H. W. Andrew Jackson: His Life and Times (2005), scholarly biography emphasizing military career excerpt and text search

- Brustein, Andrew. The Passions of Andrew Jackson. (2003). online review by Donald B. Cole

- Hofstadter, Richard. The American Political Tradition (1948), chapter on Jackson. online in ACLS e-books

- James, Marquis. The Life of Andrew Jackson Combines two books: The Border Captain and Andrew Jackson: Portrait of a President, 1933, 1937; winner of the Pulitzer Prize for Biography in 1938.

- Meacham, Jon. American Lion: Andrew Jackson in the White House (2009), excerpt and text search

- Parton, James. Life of Andrew Jackson (1860). Volume I, Volume III.

- Remini, Robert V. The Life of Andrew Jackson. Abridgment of Remini's 3-volume monumental biography, (1988).

- Andrew Jackson and the Course of American Empire, 1767–1821 (1977); Andrew Jackson and the Course of American Freedom, 1822–1832 (1981); Andrew Jackson and the Course of American Democracy, 1833–1845 (1984).

- Remini, Robert V. The Legacy of Andrew Jackson: Essays on Democracy, Indian Removal, and Slavery (1988).

- Remini, Robert V. Andrew Jackson and his Indian Wars (2001).

- Remini, Robert V. "Andrew Jackson," American National Biography (2000).

- Wilentz, Sean. Andrew Jackson (2005), short biography, stressing Indian removal and slavery issues excerpt and text search

Specialized studies

- Cave, Alfred A.. Abuse of Power: Andrew Jackson and the Indian Removal Act of 1830 (2003).

- Gammon, Samuel Rhea. The Presidential Campaign of 1832 (1922).

- Hammond, Bray. Andrew Jackson's Battle with the "Money Power" (1958) ch 8, of his Banks and Politics in America: From the Revolution to the Civil War (1954); Pulitzer prize.

- Meacham, Jon (2008). American Lion. Random House, Inc. ISBN 9781400063253.

- Latner Richard B. The Presidency of Andrew Jackson: White House Politics, 1820–1837 (1979), standard survey.

- Ogg, Frederic Austin ; The Reign of Andrew Jackson: A Chronicle of the Frontier in Politics 1919. Short popular survey online at Gutenberg.

- Parsons, Lynn H. The Birth of Modern Politics: Andrew Jackson, John Quincy Adams, and the Election of 1828 (2009) excerpt and text search

- Ratner, Lorman A. Andrew Jackson and His Tennessee Lieutenants: A Study in Political Culture (1997).

- Rowland, Dunbar. Andrew Jackson's Campaign against the British, or, the Mississippi Territory in the War of 1812, concerning the Military Operations of the Americans, Creek Indians, British, and Spanish, 1813–1815 (1926).

- Schama, Simon. The American Future: A History (2008).

- Schlesinger, Arthur M. Jr. The Age of Jackson. (1945). Winner of the Pulitzer Prize for History. history of ideas of the era.

- Syrett, Harold C. Andrew Jackson: His Contribution to the American Tradition (1953). on Jacksonian Democracy

Historiography

- Bugg Jr. James L. ed. Jacksonian Democracy: Myth or Reality? (1952), excerpts from scholars.

- Mabry, Donald J., Short Book Bibliography on Andrew Jackson, Historical Text Archive.

- Sellers, Charles Grier, Jr. "Andrew Jackson versus the Historians," The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Vol. 44, No. 4. (March, 1958), pp. 615–634. in JSTOR.

- Taylor, George Rogers, ed. Jackson Versus Biddle: The Struggle over the Second Bank of the United States (1949), excerpts from primary and secondary sources.

- Ward, John William. Andrew Jackson, Symbol for an Age (1962) how writers saw him.

External links

- The White House

- Andrew Jackson Biography and Fact File, via American-presidents.com

- Works by Andrew Jackson at Project Gutenberg

- Template:Worldcat id

- Andrew Jackson, the national bank and censure

- American Political History Online

- White House Biography

- Andrew Jackson on the Web (resource directory)

- Critical Resources: Andrew Jackson and Indian Removal

- A genealogical profile of the President, via argeron.com

- Jackson's medical history, via doctorzebra.com

- Jackson letters to Richard K. Call

- Jackson's 1,400 lb (640 kg) Cheddar

- Andrew Jackson's Candidacy, August 25, 1828 From Texas Tides

- Andrew Jackson's veto speech in 1832 regarding the Bank of the US

- Transcripts of letters of Andrew Jackson at the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History

- Essay on Jackson, each member of his cabinet and First Lady - the Miller Center of Public Affairs

- United States Congress. "Andrew Jackson (id: J000005)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Andrew Jackson

- 1767 births

- 1845 deaths

- 19th-century presidents of the United States

- American people of Scotch-Irish descent

- American people of English descent

- American planters

- American Presbyterians

- American Revolutionary War prisoners of war

- American shooting survivors

- Attempted assassination survivors

- Burials in Tennessee

- Congressional Gold Medal recipients

- Deaths from edema

- Deaths from tuberculosis

- Democratic Party (United States) presidential nominees

- Duellists

- Governors of Florida Territory

- History of the United States (1789–1849)

- Infectious disease deaths in Tennessee

- Members of the United States House of Representatives from Tennessee

- People from Lancaster County, South Carolina

- People from Nashville, Tennessee

- People of the Creek War

- People of the Seminole Wars

- Presidents of the United States

- Tennessee Supreme Court justices

- United States Army generals

- United States military governors

- United States military personnel of the War of 1812

- United States presidential candidates, 1824

- United States presidential candidates, 1828

- United States presidential candidates, 1832

- U.S. Presidents surviving assassination attempts

- United States Senators from Tennessee

- Tennessee Democratic-Republicans

- Tennessee Democrats

- Tennessee Jacksonians

- Democratic Party Presidents of the United States

- Democratic-Republican Party United States Senators