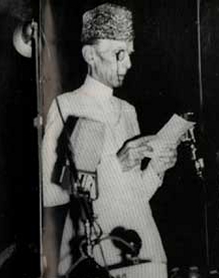

Muhammad Ali Jinnah

| ||

| Office: | 1st Governor-General of Pakistan | |

| Term of office: | August 14, 1947 – September 11, 1948 | |

| Succeeded by: | Khawaja Nazimuddin | |

| Date of birth: | December 25, 1876 | |

| Place of birth: | Wazir Mansion, Karachi | |

| Wives: | Emibai (1892–1893), Rattanbai Petit (1918–1929) | |

| Children: | daughter Dina Wadia | |

| Date of Death: | September 11, 1948 | |

| Place of Death: | Karachi | |

| Political party: | Muslim League (1913–1947), Indian National Congress (1906–1920) | |

Muhammad Ali Jinnah (Urdu: محمد على جناح; also spelled Mohammad or Mahomed Ali Jinnah) (December 25, 1876 – September 11, 1948), was an Indian Muslim politician and statesman who led the All India Muslim League and founded Pakistan, serving as its first Governor-General. He is commonly known in Pakistan as Quaid-e-Azam (Urdu: قائد اعظم — "Great Leader") and Baba-i-Qaum ("Father of the Nation"); his birth and death anniversaries are national holidays in Pakistan. While celebrated as a great leader in Pakistan, Jinnah remains a controversial figure, provoking intense criticism for his role in the partition of India.

As a student and young lawyer, Jinnah rose to prominence in the Indian National Congress, expounded Hindu-Muslim unity, shaped the 1916 Lucknow Pact between the Congress and the Muslim League, and was a key leader in the All India Home Rule League. Differences with Mohandas Gandhi led Jinnah to quit the Congress; he then took charge of the Muslim League and proposed a fourteen-point constitutional reform plan to safeguard the political rights of Muslim in a self-governing India. Disheartened by the failure of his efforts and the League's disunity, Jinnah would live in London for many years.

Several Muslim leaders persuaded Jinnah to return to India in 1934 and re-organise the League. Disillusioned by the failure to build coalitions with the Congress, Jinnah embraced the goal of creating a separate state for Muslims as in the Lahore Resolution. The League won most Muslim seats in the elections of 1946, and Jinnah launched the Direct Action campaign of strikes and protests to achieve "Pakistan", provoking communal violence across India. The failure of the Congress-League coalition to govern the country prompted both parties and the British to agree to partition. As Governor-General of Pakistan, Jinnah led efforts to rehabilitate millions of refugees, and to frame national policies on foreign affairs, security and economic development.

Early life

Jinnah was born as Mahomedali Jinnahbhai [1] in Wazir Mansion, Karachi. The earliest records of his school register suggest he was born on October 20, 1875, but Sarojini Naidu, the author of Jinnah's first biography gives the date December 25, 1876.[2] Jinnah was the eldest of five children born to Jinnahbhai Poonja (1857 - 1901), a prosperous Gujarati merchant from Kathiawar, Gujarat.[3] His family belonged to the Ismaili Khoja branch of Shi'a Islam. Jinnah had a turbulent time at several different schools, but finally found stability at the Christian Missionary Society High School in Karachi.[1]

In 1893, he went to London to work for Graham's Shipping and Trading Company. He had been married to a 16-year old, distant relative named Emibai, but she died shortly after he moved to London. His mother died around this time as well. In 1894, Jinnah quit his job to study law at Lincoln's Inn and graduated in 1896. At about this time, Jinnah began to participate in politics. An admirer of Indian political leaders Dadabhai Naoroji and Sir Pherozeshah Mehta,[4] Jinnah worked with other Indian students on Naoroji's campaign to win a seat in the British Parliament. While developing largely constitutionalist views on Indian self-government, Jinnah despised the arrogance of British officials and the discrimination against Indians.

Jinnah's life came under considerable pressure when his father's business was ruined. Settling in Mumbai (then Bombay), he became a successful lawyer – gaining particular fame for his skilled handling of the "Caucus Case".[4] Jinnah built a house in Malabar Hill, later known as Jinnah House. He was not an observing Muslim, taking pork and alcohol[5], dressed throughout his life in European-style clothes, and spoke in English more than his mother tongue, Gujarati.[6] His reputation as a skilled lawyer prompted Indian leader Bal Gangadhar Tilak to hire him as defence attorney for his sedition trial in 1905. Jinnah ably argued that it was not sedition for an Indian to demand freedom and self-government in his own country, but Tilak received a rigorous term of imprisonment.[4]

Early political career

In 1896, Jinnah joined the Indian National Congress, which was the largest Indian political organization. Like most of the Congress at the time, Jinnah did not favour outright independence, considering British influences on education, law, culture and industry as beneficial to India. Moderate leader Gopal Krishna Gokhale became Jinnah's role model, with Jinnah proclaiming his ambition to become the "Muslim Gokhale".[7] On January 25, 1910, Jinnah became a member on the sixty-member Imperial Legislative Council. The council had no real power or authority, and included a large number of un-elected pro-Raj loyalists and Europeans. Nevertheless, Jinnah was instrumental in the passing of the Child Marriages Restraint Act, the legitimization of the Muslim wakf — religious endowments — and was appointed to the Sandhurst committee, which helped establish the Indian Military Academy at Dehra Dun.[8] [3] During World War I, Jinnah joined other Indian moderates in supporting the British war effort, hoping that Indians would be rewarded with political freedoms.

Jinnah had initially avoided joining the All India Muslim League, founded in 1906, regarding it as too communal. Eventually he joined in 1913 and became the president at the 1916 session in Lucknow. Jinnah was the architect of the 1916 Lucknow Pact between the Congress and the League, bringing them together on most issues regarding self-government and presenting a united front to the British. Jinnah also played an important role in the founding of the All India Home Rule League in 1916. Along with political leaders Annie Besant and Tilak, Jinnah demanded "home rule" for India — the status of a self-governing dominion in the Empire similar to Canada, New Zealand and Australia. He headed the League's Bombay Presidency chapter. In 1918, Jinnah married his second wife Rattanbai Petit, twenty-four years his junior, and the fashionable young daughter of his personal friend Sir Dinshaw Petit of an elite Parsi family of Mumbai. Unexpectedly there was great opposition to the marriage from Rattanbai's family and Parsi society, as well as orthodox Muslim leaders. Rattanbai defied her family and converted to Islam, adopting the name "Maryam" — resulting in a permanent estrangement from her family and Parsi society. The couple resided in Mumbai, and frequently travelled across India and Europe. She bore Jinnah his only child - his daughter Dina in 1919.

Fourteen points and "exile"

Jinnah's problems with the Congress began with the ascent of Mohandas Gandhi in 1918, who espoused non-violent civil disobedience as the best means to obtain Swaraj (independence, or self-rule) for all Indians. Jinnah differed, saying that only constitutional struggle could lead to independence. Unlike most Congress leaders, Gandhi did not wear western-style clothes, did his best to use an Indian language instead of English, and was deeply spiritual and religious. Gandhi's Indianized style of leadership gained great popularity with the Indian people. Jinnah criticized Gandhi's support of the Khilafat struggle, which he saw as an endorsement of religious zealotry.[9] By 1920, Jinnah resigned from the Congress, warning that Gandhi's method of mass struggle would lead to divisions between Hindus and Muslims and within the two communities.[8] Becoming president of the Muslim League, Jinnah was drawn into a conflict between a pro-Congress faction and a pro-British faction. In 1927, Jinnah entered negotiations with Muslim and Hindu leaders on the issue of a future constitution, during the struggle against the all-British Simon Commission. The League wanted separate electorates while the Nehru Report favoured joint electorates. Jinnah personally opposed separate electorates, but then drafted compromises and put forth demands that he thought would satisfy both. These became known as the 14 points of Mr. Jinnah.[10] However, they were rejected by the Congress and other political parties.

Jinnah's personal life and especially his marriage suffered during this period, due to his political work. Although they worked to save their marriage by travelling together to Europe when he was appointed to the Sandhurst committee, the couple separated in 1927. Jinnah was deeply saddened when Rattanbai died in 1929, after a serious illness. He criticized Gandhi at the Round Table Conferences in London, but was disillusioned by the breakdown of talks.[11] Frustrated with the disunity of the Muslim League, he decided to quit politics and practise law in England. Jinnah would receive personal care and support through his later life from his sister Fatima, who lived and travelled with him and also became a close advisor. She helped raise his daughter, who was educated in England and India. Jinnah later became estranged from his daughter after she decided to marry Parsi-born Christian businessman, Neville Wadia - even though he had faced the same issues when he desired to marry Rattanbai in 1918. Jinnah continued to correspond cordially with his daughter, but their personal relationship was strained. Dina did support his demand for Pakistan in the 1940s, and refused to live in the state created by her father.

Leader of the Muslim League

Prominent Muslim leaders like the Aga Khan, Choudhary Rahmat Ali and Sir Muhammad Iqbal made efforts to convince Jinnah to return to India and take charge of a now-reunited Muslim League party. In 1934 Jinnah returned and began to re-organize the Muslim League. He was closely assisted by Liaquat Ali Khan, who would act as his right-hand man. In the 1937 elections, the League emerged as a competent party, capturing a significant number of seats under the Muslim electorate, but lost in the Muslim-majority Punjab, Sindh and the Northwest Frontier Province.[12] Jinnah offered an alliance with the Congress - both bodies would face the British together, but the Congress had to share power, accept separate electorates and the League as the representative of India's Muslims. The latter two terms were unacceptable to the Congress, which had its own national Muslim leaders and membership and adhered to secularism. Even as Jinnah held talks with Congress president Rajendra Prasad,[13] Congress leaders suspected that Jinnah would use his position as a lever for exaggerated demands and obstruct government, and demanded that the League merge with the Congress.[14] The talks failed, and while Jinnah declared the resignation in 1938 of all Congressmen from provincial and central offices as a "Day of Deliverance" from Hindu domination,[15] he remained hopeful for an agreement.[13]

In a speech to the League in 1930, Sir Muhammad Iqbal mooted an independent state for Muslims in "northwest India." Choudhary Rahmat Ali published a pamphlet in 1933 advocating a state called "Pakistan". Following the failure to work with the Congress, Jinnah, who had embraced separate electorates and the exclusive right of the League to represent Muslims, was converted to the idea that Muslims needed a separate state to protect their rights. Jinnah came to believe that Muslims and Hindus were distinct nations, with unbridgeable differences - a view later known as the Two Nation Theory.[16] Jinnah declared that a united India would lead to the marginalization of Muslims, and eventually civil war between Hindus and Muslims. This change of view may have occurred through his correspondence with Iqbal, who was close to Jinnah.[17] In the session in Lahore in 1940, the Pakistan resolution was adopted as the main goal of the party. The resolution was rejected outright by the Congress, and criticised by many Muslim leaders like Maulana Abdul Kalam Azad, Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan, Syed Ab'ul Ala Maududi and the Jamaat-e-Islami. On July 26, 1943, Jinnah was stabbed and wounded by a member of the extremist Khaksars in an attempted assassination.

Jinnah founded Dawn in 1941 - a major newspaper that helped him propagate the League's point of views. During the mission of British minister Stafford Cripps, Jinnah demanded parity between the number of Congress and League ministers, the League's exclusive right to appoint Muslims and a right for Muslim-majority provinces to secede, leading to the breakdown of talks. Jinnah supported the British effort in World War II, and opposed the Quit India movement. During this period, the League formed provincial governments and entered the central government. The League's influence increased in the Punjab after the death of Unionist leader Sikander Hyat Khan in 1942. Gandhi held talks fourteen times with Jinnah in Mumbai in 1944, about a united front - while talks failed, Gandhi's overtures to Jinnah increased the latter's standing with Muslims.[18]

Founding Pakistan

In the 1946 elections for the Constituent Assembly of India, the Congress won most of the elected seats and Hindu electorate seats, while the League won control of a large majority of Muslim electorate seats. The 1946 British Cabinet Mission to India released a plan on 16th May, calling for a united India comprised of considerably autonomous provinces, and called for "groups" of provinces formed on the basis of religion. A second plan released on June 16th, called for the partition of India along religious lines, with princely states to choose between accession to the dominion of their choice or independence. The Congress, fearing India's fragmentation, criticised the 16th May proposal and rejected the 16th June plan. Jinnah gave the League's assent to both plans, knowing that power would go only to the party that had supported a plan. After much debate and against Gandhi's advice that both plans were divisive, the Congress accepted the 16th May plan while condemning the grouping principle. Jinnah decried this acceptance as "dishonesty," accused the British negotiators of "treachery,"[19] and withdrew the League's approval of both plans. The League boycotted the assembly, leaving the Congress in charge of the government but denying it legitimacy in the eyes of many Muslims.

Jinnah issued a call for all Muslims to launch "Direct Action" on August 16 to "achieve Pakistan".[20] Strikes and protests were planned, but violence broke out all over India, especially in Calcutta and the district of Noakhali in Bengal, and more than 7,000 people were killed in Bihar. Although viceroy Lord Wavell asserted that there was "no satisfactory evidence to that effect," [21] League politicians were blamed by the Congress and the media for orchestrating the violence.[22] After a conference in December 1946 in London, the League entered the interim government, but Jinnah refrained from accepting office for himself. This was credited as a major victory for Jinnah, as the League entered government having rejected both plans, and was allowed to appoint an equal number of ministers despite being the minority party. The coalition was unable to work, resulting in a rising feeling within the Congress that partition was the only way of avoiding political chaos and possible civil war. The Congress agreed to the partition of Punjab and Bengal along religious lines in late 1946. The new viceroy Lord Mountbatten and Indian civil servant V. P. Menon proposed a plan that would create a Muslim dominion in West Punjab, East Bengal, Baluchistan and Sindh. After heated and emotional debate, the Congress approved the plan.[23] The North-West Frontier Province voted to join Pakistan in a referendum in July 1947. Jinnah asserted in a speech in Lahore on October 30, 1947 that the League had accepted partition because "the consequences of any other alternative would have been too disastrous to imagine."[24]

Governor-General

Along with Liaquat Ali Khan and Abdur Rab Nishtar, Muhammad Ali Jinnah represented the League in the Partition Council to appropriately divide public assets between India and Pakistan.[25] The assembly members from the provinces that would comprise Pakistan formed the new state's constituent assembly, and the Military of British India was divided between Muslim and non-Muslim units and officers. Indian leaders were angered at Jinnah's courting the princes of Jodhpur, Bhopal and Indore to accede to Pakistan - these princely states were not geographically aligned with Pakistan, and each had a Hindu-majority population.[26]

Muhammad Ali Jinnah became the first Governor-General of Pakistan and president of its constituent assembly. Inaugurating the assembly on August 11, 1947, Jinnah put forward a vision for a secular state:

- You may belong to any religion caste or creed - that has nothing to do with the business of the state. In due course of time, Hindus will cease to be Hindus and Muslims will cease to be Muslims, not in the religious sense, because that is the personal faith of each individual, but in the political sense as citizens of the state.[27]

The office of Governor-General was ceremonial, but Jinnah also assumed the lead of government. The first months of Pakistan's existence were absorbed in ending the intense violence that had arisen. In wake of acrimony between Hindus and Muslims, Jinnah agreed with Indian leaders to organize a swift and secure exchange of populations in the Punjab and Bengal. He visited the border regions with Indian leaders to calm people and encourage peace, and organized large-scale refugee camps. Despite these efforts, estimates on the death toll vary from around two hundred thousand, to over a million people.[28] The estimated number of refugees in both countries exceeds 15 million.[29] The capital city of Karachi saw an explosive increase in its population owing to the large encampments of refugees. Jinnah was personally affected and depressed by the intense violence of the period.[30]

Jinnah authorized force to achieve the annexation of the princely state of Kalat and suppress the insurgency in Baluchistan. He controversially accepted the accession of Junagadh - a Hindu-majority state with a Muslim ruler located in the Saurashtra peninsula, some 400 kilometres southeast of Pakistan - but this was annulled by Indian intervention. It is unclear if Jinnah planned or knew of the tribal invasion from Pakistan into the kingdom of Jammu and Kashmir in October 1947, but he did send his private secretary Khurshid Ahmed to observe developments in Kashmir. When informed of Kashmir's accession to India, Jinnah deemed the accession illegitimate and ordered the Pakistani army to enter Kashmir.[31] However, Gen. Auchinleck, the Supreme Commander of all British officers informed Jinnah that while India had the right to send troops to Kashmir, which had acceded to it, Pakistan did not. If Jinnah persisted, Auchinleck would remove all British officers from both sides. As Pakistan had a greater proportion of Britons holding senior command, Jinnah cancelled his order, but protested to the United Nations to intercede.[31]

Owing to his role in the state's creation, Jinnah was the most popular and influential politician. He played a pivotal role in protecting the rights of minorities,[32] establishing colleges, military institutions and Pakistan's financial policy.[33] In his first visit to East Pakistan, Jinnah stressed that Urdu alone should be the national language. He also worked for an agreement with India settling disputes regarding the division of assets.[34]

Death

Through the 1940s, Jinnah suffered from tuberculosis — only his sister and a few others close to Jinnah were aware of his condition. In 1948, Jinnah's health began to falter, hindered further by the heavy workload that had fallen upon him following Pakistan's creation. Attempting to recuperate, he spent many months at his official retreat in Ziarat, but died on September 11 1948 from a combination of tuberculosis and lung cancer. His funeral was followed by the construction of a massive mausoleum — Mazar-e-Quaid — in Karachi to honour him; official and military ceremonies are hosted there on special occasions.

Dina Wadia remained in India after partition, before ultimately settling in New York City. Jinnah's grandson, Nusli Wadia, is a prominent industrialist residing in Mumbai. In the 1963–1964 elections, Jinnah's sister Fatima Jinnah, known as Madar-e-Millat ("Mother of the Nation"), became the presidential candidate of a coalition of political parties that opposed the rule of President Ayub Khan, but lost the election. The Jinnah House in Malabar Hill, Mumbai is in the possession of the Government of India — its future is officially disputed.[35]. Jinnah had personally requested Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru to preserve the house - he hoped for good relations between India and Pakistan, and that one day he could return to Mumbai.[36]There are proposals for the house be offered to the Government of Pakistan to establish a consulate in the city, as a goodwill gesture, but Dina Wadia's family have laid claim to the property.

Modern views on Jinnah

Muhammad Ali Jinnah provokes controversy in modern India and Pakistan - from great adulation and admiration, to intense criticism and hatred, and there are many differing theories postulated by historians to explain his motivations. In Pakistan, Jinnah is criticized by some, including Choudhary Rahmat Ali, for accepting a Pakistan smaller than envisioned.[37] In the 1970s and 1980s, Pakistan adopted more Islamic laws and the Sharia law code, against Jinnah's vision of a secular state. In India, Jinnah is often seen as a communalist who divided India and tore millions of people from their homes by creating an atmosphere of hatred between Hindus and Muslims.

Critics point at Jinnah's courting the princes of Hindu states and his gambit with Junagadh as proof of his ill intentions towards India, as he was the proponent of the theory that Hindus and Muslims could not live together, yet being interested in Hindu-majority states.[38] In his book Patel: A Life, Rajmohan Gandhi asserts that Jinnah sought to engage the question of Junagadh with an eye on Kashmir - he wanted India to ask for a plebiscite in Junagadh, knowing thus that the principle then would have to be applied to Kashmir, where the Muslim-majority would, he believed, vote for Pakistan.[39] Some historians like H M Seervai and Ayesha Jalal assert that Jinnah never wanted partition - it was the outcome of the Congress leaders being unwilling to share power with the League. It is asserted that Jinnah only used the Pakistan demand as a method to mobilize support to obtain significant political rights for Muslims. Jinnah has gained the admiration of major Indian nationalist politicians like Atal Bihari Vajpayee and Lal Krishna Advani - the latter's comments praising Jinnah caused an uproar in his own Bharatiya Janata Party.[40] Jinnah also received praise from US President Harry Truman at the time of his death, and from South African leader Nelson Mandela upon his visit to Pakistan in 1995.

Commemoration

In Pakistan, Jinnah is honoured with the official title Quaid-e-Azam, and he is depicted on all Pakistani rupee notes of denominations ten and higher, and is the namesake of many Pakistani public institutions. The Quaid-e-Azam International Airport in Karachi is Pakistan's busiest. One of the largest streets in the Turkish capital Ankara — Cinnah Caddesi — is named after him. In Iran, one of the capital Tehran's most important new highways is also named after him, while the government released a stamp commemorating the centennial of Jinnah's birthday. The Mazar-e-Quaid, Jinnah's mausoleum, is among Karachi's most imposing buildings. In media, Jinnah was portrayed by British actors Richard Lintern (as the youthful Jinnah) and Christopher Lee (as the elder Jinnah) in the 1998 film "Jinnah".[41] In Richard Attenborough's film Gandhi,[42] Jinnah was portrayed by theatre-personality Alyque Padamsee. In the 1986 televised mini-series Lord Mountbatten: the Last Viceroy, Jinnah was played by Polish actor Vladek Sheybal.

Notes

- ^ a b Official website, Government of Pakistan. ""Early Days: Birth and Schooling"". Retrieved 2006-04-20.

- ^ "Pakistanspace", Tripod.com. ""1947: December - Pakistan celebrates founder's birthday"". Retrieved 2006-04-20.

- ^ a b Timeline: Personalities, Story of Pakistan. ""Muhammad Ali Jinnah (1876-1948)"". Retrieved 2006-04-20.

- ^ a b c Official website, Government of Pakistan. ""The Lawyer: Bombay (1896-1910)"". Retrieved 2006-04-20.

- ^ Jinnah was not observing Muslim

- ^ Hardiman, Peasant Nationalists of Gujarat, pp. 89

- ^ "Sarojini Naidu", Nazaria-e-Pakistan Foundation. "" Mohammad Ali Jinnah: An Ambassador of Unity: A Pen Portrait"". Retrieved 2004-04-20.

- ^ a b Official website, Government of Pakistan. ""The Statesman: Jinnah's differences with the Congress"". Retrieved 2006-04-20.

- ^ Ayesha Jalal, The Sole Spokesman, pp. 8

- ^ Official website, Government of Pakistan. ""The Statesman: Quaid-i-Azam's Fourteen Points"". Retrieved 2006-04-20.

- ^ Official website, Government of Pakistan. ""The Statesman: London 1931"". Retrieved 2006-04-20.

- ^ Ayesha Jalal, The Sole Spokesman, pp. 27

- ^ a b Ayesha Jalal, The Sole Spokesman, pp. 14

- ^ Rajmohan Gandhi, Patel: A Life, pp. 262

- ^ R. Gandhi, Patel: A Life, pp. 289

- ^ Rajmohan Gandhi, Patel: A Life, pp. 292

- ^ Official website, Government of Pakistan. ""The Statesman: Allama Iqbal's Presidential Address at Allahabad 1930"". Retrieved 2006-04-20.

- ^ Rajmohan Gandhi, Patel: A Life, pp. 331

- ^ Rajmohan Gandhi, Patel: A Life, pp. 369

- ^ Rajmohan Gandhi, Patel: A Life", pp. 372-73

- ^ Mansergh, "Transfer of Power Papers Volume IX", pp 879

- ^ R. Gandhi, Patel: A Life, pp. 376-78

- ^ Official website, Government of Pakistan. ""The Leader: The Plan of June 3, 1947: page 2"". Retrieved 2006-04-20.

- ^ "Pakistanspace", Tripod.com. ""1947: October - Jinnah visits Lahore"". Retrieved 2006-04-20.

- ^ Rajmohan Gandhi, Patel: A Life, pp. 416

- ^ R. Gandhi, Patel: A Life, pp. 407-08

- ^ Official website, Government of Pakistan. ""The Governor General"". Retrieved 2006-04-20.

- ^ "Matthew White", Users.Erols.com. ""Secondary Wars and Atrocities of the Twentieth Century"". Retrieved 2006-04-20.

- ^ "Postcolonial Studies" project, Department of English, Emory University. ""The Partition of India"". Retrieved 2006-04-20.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Pakistanspace", Tripod.com. ""1947: September - Formidable Jinnah is very dignified and very sad"". Retrieved 2006-04-20.

- ^ a b Rajmohan Gandhi, Patel: A Life, pp. 444

- ^ "Pakistanspace", Tripod.com. ""1947: October - Jinnah wants the minorities to stay in Pakistan"". Retrieved 2006-04-20.

- ^ Official website, Government of Pakistan. ""The Governor General: The Last Year: page 2"". Retrieved 2006-04-20.

- ^ "Pakistanspace", Tripod.com. ""1947: December - Money matters"". Retrieved 2006-04-20.

- ^ Basit Ghafoor, Chowk.com. ""Dina Wadia Claims Jinnah House"". Retrieved 2006-04-20.

- ^ Jinnah's Bombay house

- ^ Ayesha Jalal, The Sole Spokesman, pp.xvi (preface)

- ^ R. Gandhi, Patel: A Life, pp. 435

- ^ Rajmohan Gandhi, Patel: A Life, pp. 435-36

- ^ Online edition, Hindustan Times. ""Pakistan expresses shock over Advani's resignation as BJP chief"". Retrieved 2006-04-20.

- ^ "Wiltshire - Films & TV", BBC website. ""Interview with Christopher Lee"". Retrieved 2006-04-20.

- ^ Internet Movie Database, Amazon.com. ""Gandhi (1982)"". Retrieved 2006-04-20.

References

- Rajmohan Gandhi, Patel: A Life (1990, Navajivan, Ahmedabad; ASIN: B0006EYQ0A)

- Peasant Nationalists of Gujarat, David Hardiman, ISBN: 0195612558

- Secular and Nationalist Jinnah by Dr Ajeet Javed JNU Press Delhi

- Jinnah: A Corrective Reading of Indian History by Dr Asiananda

- Jinnah, Pakistan, and Islamic Identity: The Search for Saladin by Akbar S. Ahmed (1997)

- Jinnah of Pakistan by Stanley Wolpert Oxford University Press (2002)

- Liberty or Death: India's Journey to Independence and Division by Patrick French, Harper Collins, 1997

- Fatima Jinnah (1987). My Brother. Quaid-i-Azam Academy. ISBN 969-413-036-0.

- Ayesha Jalal (1994). The Sole Spokesman: Jinnah, the Muslim League and the Demand for Pakistan. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521458501.

- Mansergh, Transfer of Power Papers (Volume IX)

External links

|

|