Opiate

This article needs attention from an expert in Medicine. The specific problem is: Article has little relevant information despite high importance of subject, should discuss drug class in general. See the talk page for details. (June 2012) |

- For other uses see Opiate (disambiguation), or for the class of drugs see Opioid.

In medicine, the term opiate describes any of the narcotic opioid alkaloids found as natural products in the opium poppy plant, Papaver somniferum.[1]

Overview

Opiates belong to the large biosynthetic group of benzylisoquinoline alkaloids, and are so named because they are naturally occurring alkaloids found in the opium poppy. The major psychoactive opiates are morphine, codeine, and thebaine. Papaverine, noscapine, and approximately 24 other alkaloids are also present in opium but have little to no effect on the human central nervous system, and as such are not considered to be opiates. Semi-synthetic opioids such as hydrocodone, hydromorphone, oxycodone, and oxymorphone, while derived from opiates, are not opiates themselves.

While the full synthesis of opiates from naphthoquinone (Gates synthesis) or from other simple organic starting materials is possible, they are tedious and uneconomical processes. Therefore, most of the opiate-type analgesics in use today are either directly extracted from Papaver somniferum or synthesized from the natural opiates, mainly from thebaine.[2]

Terminology

The term opiate refers only to the alkaloids found naturally in opium, but is often incorrectly used to describe all drugs with opium- or morphine-like pharmacological action, which are more properly classified under the broader term opioid.

The alkaloids

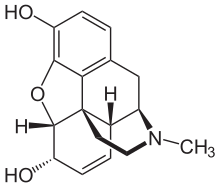

Morphine

The most frequently reported occurrences of opiate-induced pulmonary edema are among recreational heroin users.[3][4] Although uncommon, reports of morphine-induced pulmonary edema are not unheard of.[5] The primary difference is the more careful supervision of morphine administration compared to the lack of supervision and medical expertise among illicit heroin users. On the other hand, morphine may also be used in the treatment of pulmonary edema.[6][7] Despite morphine's being the most medically significant alkaloid, larger quantities of the milder codeine—most of it manufactured from morphine—are consumed medically, as codeine has a greater and more predictable oral bioavailability than morphine, making it easier to titrate one's dose.

As heroin is not pharmacologically active it must first be metabolized. The active metabolites of heroin are morphine, 6-monoacetylmorphine and 3-monoacetylmorphine.

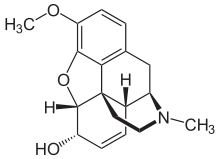

Codeine

Esters of Morphine

There are several semi-synthetic opioids derived from the opiate morphine. Heroin (diacetylmorphine) is a morphine prodrug, meaning that it is metabolized by the body into morphine after administration. One of the major metabolites of heroin, 6-monoacetylmorphine (6-MAM), is also a morphine prodrug. Nicomorphine (morphine dinicotinate), dipropanoylmorphine (morphine dipropionate), desomorphine (di-hydro-desoxy-morphine), methyldesorphine, acetylpropionylmorphine, dibenzoylmorphine, diacetyldihydromorphine, and several others are also derived from morphine.[8]

Withdrawal effects

Opiate withdrawal syndrome effects are associated with the abrupt cessation or reduction of prolonged opiate usage.

In medical facilities such as hospitals and clinics, the threat of relapse is possible when Post-acute-withdrawal syndrome is under-emphasized to patients in transitional phases, especially with short-term buprenorphine, methadone or health facilities.

Release of Opiates in human body

When opiates are released in human body, it becomes the resource of liking stimuli and processes enjoyment of a reward. Opiates are released in body through nursing, sexual activity, maternal and social interaction and touch. It produces a calm state and quiescence.[9]

See also

References

- ^ "Opiate - Definitions from Dictionary.com". dictionary.reference.com. Retrieved 2008-07-04.

- ^ Synthesis of morphine alkaloids Presentation School of Chemical Sciences, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign retrieved 12-02-2010

- ^ Sporer KA, Dorn E (2001). "Heroin-related noncardiogenic pulmonary edema : a case series". Chest. 120 (5): 1628–32. doi:10.1378/chest.120.5.1628. PMID 11713145.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Steensen P, Jørgensen HS, Juhl B (1993). "[Heroin-induced pulmonary edema]". Ugeskr. Laeg. (in Danish). 155 (37): 2866–8. PMID 8259608.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wang WS, Chiou TJ, Hsieh RK, Liu JH, Yen CC, Chen PM (1997). "Lethal acute pulmonary edema following intravenous naloxone in a patient received unrelated bone marrow transplantation". Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi (Taipei). 60 (4): 219–23. PMID 9439052.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) [dead link] - ^ Pino F, Puerta H, D'Apollo R; et al. (1993). "Effectiveness of morphine in non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema due to chlorine gas inhalation". Vet Hum Toxicol. 35 (1): 36. PMID 8434449.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mattu A, Martinez JP, Kelly BS (2005). "Modern management of cardiogenic pulmonary edema". Emerg. Med. Clin. North Am. 23 (4): 1105–25. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2005.07.005. PMID 16199340.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Esters of Morphine". United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. http://www.unodc.org. Retrieved 10 March 2012.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ Jenkins, Dacher Keltner, Keith Oatley, Jennifer M. Understanding emotions (3rd ed. ed.). Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley. ISBN 9781118147436.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)