Maya Angelou

Maya Angelou | |

|---|---|

| Angelou recites her poem, "On the Pulse of Morning", at President Bill Clinton's inauguration, January 1993 Angelou recites her poem, "On the Pulse of Morning", at President Bill Clinton's inauguration, January 1993 | |

| Born | Marguerite Ann Johnson April 4, 1928 St. Louis, Missouri, U.S. |

| Occupation | Poet, civil rights activist, dancer, film producer, television producer, playwright, film director, author, actress, professor |

| Language | English |

| Period | 1969–present |

| Genre | Autobiography |

| Literary movement | Civil rights |

| Notable works | I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings On the Pulse of Morning |

| Website | |

| http://www.mayaangelou.com | |

Maya Angelou (/ˈmaɪ.ə ˈændʒəloʊ/;[1][2] born Marguerite Ann Johnson; April 4, 1928) is an American author and poet. She has published seven autobiographies, three books of essays, and several books of poetry, and is credited with a list of plays, movies, and television shows spanning more than fifty years. She has received dozens of awards and over thirty honorary doctoral degrees. Angelou is best known for her series of seven autobiographies, which focus on her childhood and early adult experiences. The first, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings (1969), tells of her life up to the age of seventeen, and brought her international recognition and acclaim.

Angelou's list of occupations includes pimp, prostitute, night-club dancer and performer, castmember of the opera Porgy and Bess, coordinator for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, author, journalist in Egypt and Ghana during the days of decolonization, and actor, writer, director, and producer of plays, movies, and public television programs. Since 1982, she has taught at Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, where she holds the first lifetime Reynolds Professorship of American Studies. She was active in the Civil Rights movement, and worked with Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X. Since the 1990s she has made around eighty appearances a year on the lecture circuit, something she continued into her eighties. In 1993, Angelou recited her poem "On the Pulse of Morning" at President Bill Clinton's inauguration, the first poet to make an inaugural recitation since Robert Frost at John F. Kennedy's inauguration in 1961.

In I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, Angelou publicly discussed her intimate life. Angelou's major works have been labeled as autobiographical fiction, but many critics have characterized them as autobiographies [citation needed] --> Her written works address racism, identity, family, and travel.

Life and career

Early years

Marguerite Johnson was born in St. Louis, Missouri, on April 4, 1928, the second child of Bailey Johnson, a doorman and a navy dietitian, and Vivian (Baxter) Johnson, a nurse and card dealer.[3] Angelou's older brother, Bailey Jr., nicknamed Marguerite "Maya," shortened from "My" or "Mya Sister."[4] When Angelou was three, and her brother four, their parents' "calamitous marriage"[5] ended, and their father sent them to Stamps, Arkansas, alone by train to live with their paternal grandmother, Annie Henderson. In "an astonishing exception"[6] to the harsh economics of African Americans of the time, Angelou's grandmother prospered financially during the Great Depression and World War II because the general store she owned sold needed basic commodities and because "she made wise and honest investments".[3][note 1]

And Angelou's life has certainly been a full one: from the hardscrabble Depression era South to pimp, prostitute, supper-club chanteuse, performer in Porgy and Bess, coordinator for Martin Luther King Jr.'s Southern Christian Leadership Conference, journalist in Egypt and Ghana in the heady days of decolonization, comrade of Malcolm X, eyewitness to the Watts riots. She knew King and Malcolm, Billie Holiday and Abbey Lincoln.

Reviewer John McWhorter, The New Republic (McWhorter, p. 36)

To know her life story is to simultaneously wonder what on earth you have been doing with your own life and feel glad that you didn't have to go through half the things she has.

The Guardian writer Gary Younge, 2009

Four years later, the children's father "came to Stamps without warning"[8] and returned them to their mother's care in St. Louis. At the age of eight, while living with her mother, Angelou was sexually abused and raped by her mother's boyfriend, Mr. Freeman. She told her brother, who told the rest of their family. Freeman was found guilty, but was jailed for only one day. Four days after his release, he was murdered, probably by Angelou's uncles. Angelou became mute for almost five years,[9] believing, as she has stated, "I thought, my voice killed him; I killed that man, because I told his name. And then I thought I would never speak again, because my voice would kill anyone ..."[10] According to Marcia Ann Gillespie and her colleagues, who wrote a biography about Angelou, it was during this period of silence when Angelou developed her extraordinary memory, her love for books and literature, and her ability to listen and observe the world around her.[11]

Shortly after Freeman's murder, Angelou and her brother were sent back to their grandmother once again.[12] Angelou credits a teacher and friend of her family, Mrs. Bertha Flowers, with helping her speak again. Flowers introduced her to authors such as Charles Dickens, William Shakespeare, Edgar Allan Poe, Douglas Johnson, and James Weldon Johnson, authors that would affect her life and career, as well as Black female artists like Frances Harper, Anne Spencer, and Jessie Fauset.[13][14][15] When Angelou was 14, she and her brother moved in with their mother once again; she had since moved to Oakland, California. During World War II, she attended George Washington High School while studying dance and drama on a scholarship at the California Labor School. Before graduating, she worked as the first Black female streetcar conductor in San Francisco.[16] Three weeks after completing school, at the age of 17, she gave birth to her son, Clyde (who later changed his name to Guy Johnson).[17][18]

Angelou's second autobiography, Gather Together in My Name, recounts her life from age 17 to 19 and "depicts a single mother's slide down the social ladder into poverty and crime."[19] Angelou worked as "the front woman/business manager for prostitutes,"[20] restaurant cook, and prostitute. She moved through a series of relationships, occupations, and cities as she attempted to raise her son without job training or advanced education.[21]

Adulthood and early career: 1951–61

In 1951, Angelou married Greek electrician, former sailor, and aspiring musician Enistasious (Tosh) Angelos despite the condemnation of interracial relationships at the time and the disapproval of her mother.[22][23] She took modern dance classes during this time, and met dancers and choreographers Alvin Ailey and Ruth Beckford. Angelou and Ailey formed a dance team, calling themselves "Al and Rita", and performed Modern Dance at fraternal Black organizations throughout San Francisco, but never became successful.[24] Angelou, her new husband, and son moved to New York City so that she could study African dance with Trinidadian dancer Pearl Primus, but they returned to San Francisco a year later.[25]

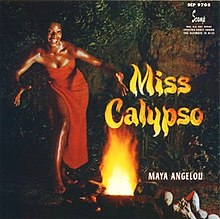

After Angelou's marriage ended in 1954, she danced professionally in clubs around San Francisco, including the nightclub The Purple Onion, where she sang and danced calypso music.[26] Up to that point she went by the name of "Marguerite Johnson", or "Rita", but at the strong suggestion of her managers and supporters at The Purple Onion she changed her professional name to "Maya Angelou", a "distinctive name"[27] that set her apart and captured the feel of her Calypso dance performances. During 1954 and 1955 Angelou toured Europe with a production of the opera Porgy and Bess. She began her practice of learning the language of every country she visited, and in a few years she gained proficiency in several languages.[28] In 1957, riding on the popularity of calypso, Angelou recorded her first album, Miss Calypso, which was reissued as a CD in 1996.[24][29][30] She appeared in an off-Broadway review that inspired the film Calypso Heat Wave, in which Angelou sang and performed her own compositions.[29][note 2][note 3]

Angelou met novelist James O. Killens in 1959, and at his urging, moved to New York to concentrate on her writing career. She joined the Harlem Writers Guild, where she met several major African-American authors, including John Henrik Clarke, Rosa Guy, Paule Marshall, and Julian Mayfield, and was published for the first time.[32] In 1960, after meeting civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and hearing him speak, she and Killens organized "the legendary"[33] Cabaret for Freedom to benefit the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and she was named SCLC's Northern Coordinator. According to scholar Lyman B. Hagen, her contributions to civil rights as a fundraiser and SCLC organizer were successful and "eminently effective".[34] Angelou also began her pro-Castro and anti-apartheid activism during this time.[35]

Africa to Caged Bird: 1961–69

In 1961, Angelou performed in Jean Genet's The Blacks, along with Abbey Lincoln, Roscoe Lee Brown, James Earl Jones, Louis Gossett, Godfrey Cambridge, and Cicely Tyson.[36] That year she met South African freedom fighter Vusumzi Make; they never officially married.[37] She and her son Guy moved to Cairo with Make where Angelou worked as an associate editor at the weekly English-language newspaper The Arab Observer.[38][39] In 1962 her relationship with Make ended, and she and Guy moved to Accra, Ghana, he to attend college, but he was seriously injured in an automobile accident.[note 4] Angelou remained in Accra for his recovery and ended up staying there until 1965. She became an administrator at the University of Ghana, and was active in the African-American expatriate community.[41] She was a feature editor for The African Review,[42] a freelance writer for the Ghanaian Times, wrote and broadcast for Radio Ghana, and worked and performed for Ghana's National Theatre. She performed in a revival of The Blacks in Geneva and Berlin.[43]

In Accra, she became close friends with Malcolm X during his visit in the early 1960s.[note 5] Angelou returned to the U.S. in 1965 to help him build a new civil rights organization, the Organization of Afro-American Unity; he was assassinated shortly afterward. Devastated and adrift, she joined her brother in Hawaii, where she resumed her singing career, and then moved back to Los Angeles to focus on her writing career. She worked as a market researcher in Watts and witnessed the riots in the summer of 1965. She acted in and wrote plays, and returned to New York in 1967. She met her lifelong friend Rosa Guy and renewed her friendship with James Baldwin, whom she had met in Paris in the 1950s and called "my brother", during this time.[45] Her friend Jerry Purcell provided Angelou with a stipend to support her writing.[46]

In 1968, Martin Luther King asked Angelou to organize a march. She agreed, but "postpones again",[33] and in what Gillespie calls "a macabre twist of fate",[47] he was assassinated on her 40th birthday (April 4).[note 6] Devastated again, she was encouraged out of her depression by her friend James Baldwin. As Gillespie states, "If 1968 was a year of great pain, loss, and sadness, it was also the year when America first witnessed the breadth and depth of Maya Angelou's spirit and creative genius".[47] Despite almost no experience, she wrote, produced, and narrated "Blacks, Blues, Black!", a ten-part series of documentaries about the connection between blues music and Black Americans' African heritage and what Angelou called the "Africanisms still current in the U.S."[49] for National Educational Television, the precursor of PBS. Also in 1968, inspired at a dinner party she attended with Baldwin, cartoonist Jules Feiffer, and his wife Judy, and challenged by Random House editor Robert Loomis, she wrote her first autobiography, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, published in 1969, which brought her international recognition and acclaim.[50]

Later career

Angelou's Georgia, Georgia, produced by a Swedish film company and filmed in Sweden, the first screenplay written by a Black woman,[51] was released in 1972. She also wrote the film's soundtrack, despite having very little additional input in the filming of the movie.[52] Angelou married Welsh carpenter and ex-husband of Germaine Greer, Paul du Feu, in San Francisco in 1973.[note 7] In the next ten years, as Gillespie has stated, "She had accomplished more than many artists hope to achieve in a lifetime".[54] She worked as a composer, writing for singer Roberta Flack and composing movie scores. She wrote articles, short stories, TV scripts and documentaries, autobiographies and poetry, produced plays, and was named visiting professors of several colleges and universities. She was "a reluctant actor",[55] and was nominated for a Tony Award in 1973 for her role in Look Away. In 1977 Angelou appeared in a supporting role in the television mini-series Roots. She was given a multitude of awards during this period, including over thirty honorary degrees from colleges and universities from all over the world.[56]

In the late 1970s, Angelou met Oprah Winfrey when Winfrey was a TV anchor in Baltimore, Maryland; Angelou would later become Winfrey's close friend and mentor.[57][note 8] In 1981, Angelou and du Feu divorced. She returned to the southern United States in 1981, where she accepted the lifetime Reynolds Professorship of American Studies at Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, North Carolina.[59] From that point on, she considered herself "a teacher who writes".[60] Angelou taught a variety of subjects that reflected her interests, including philosophy, ethics, theology, science, theater, and writing.[61]

In 1993, Angelou recited her poem "On the Pulse of Morning" at the inauguration of President Bill Clinton, becoming the first poet to make an inaugural recitation since Robert Frost at John F. Kennedy's inauguration in 1961.[62] Her recitation resulted in more fame and recognition for her previous works, and broadened her appeal "across racial, economic, and educational boundaries".[63] The recording of the poem was awarded a Grammy Award.[64] In June 1995, she delivered what Richard Long called her "second 'public' poem",[65] entitled "A Brave and Startling Truth", which commemorated the 50th anniversary of the United Nations. Angelou achieved her goal of directing a feature film in 1996, Down in the Delta, which featured actors such as Alfre Woodard and Wesley Snipes.[66] Since the 1990s, Angelou has actively participated in the lecture circuit[62] in a customized tour bus, something she continued into her eighties.[67][68] In 2000, she created a successful collection of products for Hallmark, including greeting cards and decorative household items.[69][70] Over thirty years after Angelou began writing her life story, she completed her sixth autobiography A Song Flung Up to Heaven, in 2002.[71] In 2013, at the age of 85, she published the seventh autobiography in her series, Mom & Me & Mom, which focused on her relationship with her mother.[72]

Angelou campaigned for Senator Hillary Clinton in the Democratic Party in the 2008 presidential primaries.[48][73] When Clinton's campaign ended, Angelou put her support behind Senator Barack Obama,[48] who won the election and became the first African American president of the United States. She stated, "We are growing up beyond the idiocies of racism and sexism".[74] In late 2010, Angelou donated her personal papers and career memorabilia to the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem.[75] They consisted of over 340 boxes of documents that featured her handwritten notes on yellow legal pads for I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, a 1982 telegram from Coretta Scott King, fan mail, and personal and professional correspondence from colleagues such as her editor Robert Loomis.[76]

Personal life

I make writing as much a part of my life as I do eating or listening to music.

Maya Angelou, 1999[77]

I also wear a hat or a very tightly pulled head tie when I write. I suppose I hope by doing that I will keep my brains from seeping out of my scalp and running in great gray blobs down my neck, into my ears, and over my face.

Maya Angelou, 1984[78]

Nothing so frightens me as writing, but nothing so satisfies me. It's like a swimmer in the [English] Channel: you face the stingrays and waves and cold and grease, and finally you reach the other shore, and you put your foot on the ground—Aaaahhhh!

Maya Angelou, 1989[79]

Evidence suggests that Angelou was partially descended from the Mende people of West Africa.[80][note 9] A 2008 PBS documentary found that Angelou's maternal great-grandmother Mary Lee, who had been emancipated after the Civil War, became pregnant by her former white owner, John Savin. Savin forced Lee to sign a false statement accusing another man of being the father of her child. After indicting Savin for forcing Lee to commit perjury, and despite discovering that Savin was the father, a grand jury found him not guilty. Lee was sent to the Clinton County poorhouse in Missouri with her daughter, Marguerite Baxter, who became Angelou's grandmother. Angelou described Lee as "that poor little Black girl, physically and mentally bruised."[82]

The details of Angelou's life described in her seven autobiographies and in numerous interviews, speeches, and articles tend to be inconsistent. Critic Mary Jane Lupton has explained that when Angelou has spoken about her life, she has done so eloquently but informally and "with no time chart in front of her".[83] For example, she has been married at least twice, but has never clarified the number of times she has been married, "for fear of sounding frivolous";[67] according to her autobiographies and to Gillespie, she married Tosh Angelos in 1951 and Paul du Feu in 1973, and began her relationship with Vusumzi Make in 1961, but never formally married him. Angelou has one son Guy, whose birth was described in her first autobiography, one grandson, and two great-grandchildren,[84] and according to Gillespie, a large group of friends and extended family.[note 10] Angelou's mother Vivian Baxter and brother Bailey Johnson, Jr., both of whom were important figures in her life and her books, have died; her mother in 1991 and her brother in 2000 after a series of strokes.[85] In 1981, the mother of her son Guy's child disappeared with him; it took eight years to find Angelou's grandson.[86][note 11] In 2009, the gossip website TMZ erroneously reported that Angelou had been hospitalized in Los Angeles although she was alive and well in St. Louis, which resulted in rumors of her death and according to Angelou, concern with her friends and family worldwide.[88]

According to Gillespie, it has been Angelou's preference that she be called "Dr. Angelou" by people outside of her family and close friends. As of 2008, she owned two homes in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, and a "lordly brownstone"[88] in Harlem, full of her "growing library"[89] of books she has collected throughout her life, artwork collected over the span of many decades, and well-stocked kitchens. Younge has reported that in her Harlem home resides several African wall hangings and Angelou's collection of paintings, including ones of several jazz trumpeters, a watercolor of Rosa Parks, and a Faith Ringgold work entitled "Maya's Quilt Of Life".[88] According to Gillespie, she hosted several celebrations per year at her main residence in Winston-Salem, including Thanksgiving;[90] "her skill in the kitchen is the stuff of legend—from haute cuisine to down-home comfort food".[68] She combined her cooking and writing skills in her 2004 book Hallelujah! The Welcome Table, which featured 73 recipes, many of which she learned from her grandmother and mother, accompanied by 28 vignettes.[91] She followed up with her second cookbook, Great Food, All Day Long: Cook Splendidly, Eat Smart in 2010, which focused on weight loss and portion control.[92]

Beginning with I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, Angelou has used the same "writing ritual"[15] for many years. She would wake early in the morning and check into a hotel room, where the staff was instructed to remove any pictures from the walls. She would write on legal pads while lying on the bed, with only a bottle of sherry, a deck of cards to play solitaire, Roget's Thesaurus, and the Bible, and would leave by the early afternoon. She would average 10–12 pages of written material a day, which she edited down to three or four pages in the evening.[93][note 12] Angelou went through this process to "enchant" herself, and as she has said in a 1989 interview with the British Broadcasting Corporation, "relive the agony, the anguish, the Sturm und Drang."[95] She placed herself back in the time she wrote about, even traumatic experiences like her rape in Caged Bird, in order to "tell the human truth"[95] about her life. Angelou has stated that she played cards in order to get to that place of enchantment and in order to access her memories more effectively. She has stated, "It may take an hour to get into it, but once I'm in it—ha! It's so delicious!"[95] She did not find the process cathartic; rather, she has found relief in "telling the truth".[95]

Works

Angelou has written a total of seven autobiographies. According to scholar Mary Jane Lupton, Angelou's third autobiography Singin' and Swingin' and Gettin' Merry Like Christmas marked the first time a well-known African American autobiographer had written a third volume about her life.[96] Her books "stretch over time and place", from Arkansas to Africa and back to the U.S., and take place from the beginnings of World War II to the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr.[97] She published her seventh autobiography Mom & Me & Mom in 2013, at the age of 85.[98] Critics have tended to judge Angelou's subsequent autobiographies "in light of the first",[99] with Caged Bird receiving the highest praise. Angelou has written five collections of essays, which writer Hilton Als called her "wisdom books" and "homilies strung together with autobiographical texts".[33] Angelou has used the same editor throughout her writing career, Robert Loomis, an executive editor at Random House; he retired in 2011[100] and has been called "one of publishing's hall of fame editors."[101] Angelou has said regarding Loomis: "We have a relationship that's kind of famous among publishers".[102]

All my work, my life, everything I do is about survival, not just bare, awful, plodding survival, but survival with grace and faith. While one may encounter many defeats, one must not be defeated.

Maya Angelou[103]

Angelou's long and extensive career also includes poetry, plays, screenplays for television and film, directing, acting, and public speaking. She is a prolific writer of poetry; her volume Just Give Me a Cool Drink of Water 'fore I Diiie (1971) was nominated for the Pulitzer Prize, and she was chosen by President Bill Clinton to recite her poem "On the Pulse of Morning" during his inauguration in 1993.[62][104]

Angelou's successful acting career has included roles in numerous plays, films, and television programs, including her appearance in the television mini-series Roots in 1977. Her screenplay, Georgia, Georgia (1972), was the first original script by a Black woman to be produced and she was the first African American woman to direct a major motion picture, Down in the Delta, in 1998.[66] Since the 1990s, Angelou has actively participated in the lecture circuit,[62] something she continued into her eighties.[67][68]

Chronology of autobiographies

- I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings (1969): Up to 1944 (age 17)

- Gather Together in My Name (1974): 1944–1948

- Singin' and Swingin' and Gettin' Merry Like Christmas (1976): 1949–1955

- The Heart of a Woman (1981): 1957–1962

- All God's Children Need Traveling Shoes (1986): 1962–1965

- A Song Flung Up to Heaven (2002): 1965–1968

- Mom & Me & Mom (2013): overview

Reception and legacy

Influence

When I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings was published in 1969, Angelou was hailed as a new kind of memoirist, one of the first African American women who was able to publicly discuss her personal life. According to scholar Hilton Als, up to that point, black female writers were marginalized to the point that they were unable to present themselves as central characters in the literature they wrote.[33] Scholar John McWhorter agreed, seeing Angelou's works, which he called "tracts", as "apologetic writing". He placed Angelou in the tradition of African-American literature as a defense of Black culture, which he called "a literary manifestation of the imperative that reigned in the black scholarship of the period".[105] Writer Julian Mayfield, who called Caged Bird "a work of art that eludes description",[33] argued that Angelou's autobiographies set a precedent not only for other Black women writers, but for African American autobiography as a whole. Als said that Caged Bird marked one of the first times that a Black autobiographer could, as he put it, "write about blackness from the inside, without apology or defense".[33] Through the writing of her autobiography, Angelou became recognized and highly respected as a spokesperson for blacks and women.[106] It made her "without a doubt, ... America's most visible black woman autobiographer",[106] and "a major autobiographical voice of the time".[107] As writer Gary Younge said, "Probably more than almost any other writer alive, Angelou's life literally is her work".[67]

Author Hilton Als said that although Caged Bird helped increase black feminist writings in the 1970s, its success had less to do with its originality than with "its resonance in the prevailing Zeitgeist",[33] or the time in which it was written, at the end of the American Civil Rights movement. Als also claimed that Angelou's writings, more interested in self-revelation than in politics or feminism, has freed other female writers to "open themselves up without shame to the eyes of the world".[33] Angelou critic Joanne M. Braxton stated that Caged Bird was "perhaps the most aesthetically pleasing" autobiography written by an African-American woman in its era.[106]

Critical reception

Reviewer Elsie B. Washington, most likely due to President Clinton's choice of Angelou to recite her poem "On the Pulse of Morning" at his 1993 inauguration, has called Angelou "the black woman's poet laureate".[108] Sales of the paperback version of her books and poetry rose by 300–600% the week after Angelou's recitation. Random House, which published the poem later that year, had to reprint 400,000 copies of all her books to keep up with the demand. They sold more of her books in January 1993 than they did in all of 1992, accounting for a 1200% increase.[109] Angelou has famously said, in response to criticism regarding using the details of her life in her work, "I agree with Balzac and 19th-century writers, black and white, who say, 'I write for money'".[67] Younge, speaking after the publication of Angelou's third book of essays, Letter to My Daughter (2008), has said, "For the last couple of decades she has merged her various talents into a kind of performance art—issuing a message of personal and social uplift by blending poetry, song and conversation".[88]

Angelou's books, especially I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, have been criticized by many parents, causing their removal from school curricula and library shelves. According to the National Coalition Against Censorship, parents and schools have objected to Caged Bird's depictions of lesbianism, premarital cohabitation, pornography, and violence.[110] Some have been critical of the book's sexually explicit scenes, use of language, and irreverent religious depictions.[111] Caged Bird appeared third on the American Library Association (ALA) list of the 100 Most Frequently Challenged Books of 1990–2000 and sixth on the ALA's 2000–2009 list.[112][113]

Awards and honors

Angelou has been honored by universities, literary organizations, government agencies, and special interest groups. Her honors have included a Pulitzer Prize nomination for her book of poetry, Just Give Me a Cool Drink of Water 'fore I Diiie,[104] a Tony Award nomination for her role in the 1973 play Look Away, and three Grammys for her spoken word albums.[114][115] She has served on two presidential committees,[99][116] and was awarded the National Medal of Arts in 2000,[117] the Lincoln Medal in 2008,[118] and the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2011.[119] Angelou has been awarded over thirty honorary degrees.[56]

Uses in education

Angelou's autobiographies have been used in narrative and multicultural approaches in teacher education. Jocelyn A. Glazier, a professor at George Washington University, has trained teachers how to "talk about race" in their classrooms with I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings and Gather Together in My Name. According to Glazier, Angelou's use of understatement, self-mockery, humor, and irony have led readers of Angelou's autobiographies unsure of what she left out and how they should respond to the events Angelou described. Angelou's depictions of her experiences of racism has forced white readers to explore their feelings about race and their own "privileged status". Glazier found that although critics have focused on where Angelou fits within the genre of African-American autobiography and on her literary techniques, readers have tended to react to her storytelling with "surprise, particularly when [they] enter the text with certain expectations about the genre of autobiography".[120]

Educator Daniel Challener, in his 1997 book, Stories of Resilience in Childhood, analyzed the events in Caged Bird to illustrate resiliency in children. Challener argued that Angelou's book has provided a "useful framework" for exploring the obstacles many children like have Maya faced and how communities have helped them succeed.[121] Psychologist Chris Boyatzis has reported using Caged Bird to supplement scientific theory and research in the instruction of child development topics such as the development of self-concept and self-esteem, ego resilience, industry versus inferiority, effects of abuse, parenting styles, sibling and friendship relations, gender issues, cognitive development, puberty, and identity formation in adolescence. He found the book a "highly effective" tool for providing real-life examples of these psychological concepts.[122]

Poetry

Although Angelou is best known for her seven autobiographies, she has also been a prolific and successful poet. She has called "the black woman's poet laureate", and her poems have been called the anthems of African Americans.[108] Angelou studied and began writing poetry at a young age, and used poetry and other great literature to cope with her rape as a young girl, as described in Caged Bird.[13] According to scholar Yasmin Y. DeGout, literature also affects Angelou's sensibilities as the poet and writer she becomes, especially the "liberating discourse that would evolve in her own poetic canon".[123]

When she was a night club performer, Angelou recorded two albums of poetry and songs; the first in 1957 for Liberty Records and the second. "The Poetry of Maya Angelou", for GWP Records the year before the publication of Caged Bird. They were later incorporated into her volumes of poetry.[124] According to Lipton, Many of her readers consider her a poet first and an autobiographer second, but she is better known for her prose works.[125] She has published several volumes of poetry, and has experienced similar success as a poet. She began, early in her writing career, of alternating a volume of poetry with an autobiography.[126] Her first volume of poetry, Just Give Me a Cool Drink of Water 'fore I Diiie (1971), became a best-seller and was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize.[127] In 1993, she recited her most well-known poem, "On the Pulse of Morning", at President Bill Clinton's inauguration.[125] Angelou delivered what Richard Long called her "second 'public' poem",[65] entitled "A Brave and Startling Truth", which commemorated the 50th anniversary of the United Nations in 1995. Also in 1995, she was chosen to recite one of her poems at the Million Man March.[128] Angelou was the first African American woman and living poet selected by Sterling Publishing, who placed 25 of her poems in a volume of their Poetry for Young People series in 2004.[129] In 2009, she wrote "We Had Him", a poem about Michael Jackson, which was read by Queen Latifah at his funeral.[130]

Angelou explores many of the same themes throughout all her writings, in both her autobiographies and poetry. These themes include love, painful loss, music, discrimination and racism, and struggle.[131][132] According to DeGout, Angelou's poetry cannot easily be placed in categories of themes or techniques.[123] Gillespie has also stated that Angelou's poems "reflect the richness and subtlety of Black speech and sensibilities" and were meant to be read aloud.[127] Critic Harold Bloom had compared Angelou's poetry to musical forms such as country music and ballads, and has characterized her poems as having a social rather than aesthetic function, "particularly in an era totally dominated by visual media".[133] Her themes and topics, although written for and about African Americans, are universal enough to apply to all races.[134] Angelou uses everyday language, the Black vernacular, Black music and forms, and rhetorical techniques such as shocking language, the occasional use of profanity, and traditionally unacceptable subjects. As she does throughout her autobiographies, Angelou speaks not only for herself, but for her entire gender and race. Her poems continue the themes of mild protest and survival also found in her autobiographies, and inject hope through humor.[135]

Many critics consider Angelou's autobiographies more important than her poetry.[136] Although her books have been best-sellers, her poetry has not been perceived as seriously her prose and has been understudied.[3] Her poems are more interesting when she recites and performs them, and many critics emphasize the public aspect of her poetry.[137] Angelou's lack of critical acclaim has been attributed to both the public nature of many of her poems and to Angelou's popular success, and to critics' preferences for poetry as a written form rather than a verbal, performed one.[133] Burr has countered Angelou's critics by condemning them for not taking into account Angelou's larger purposes in her writing: "to be representative rather than individual, authoritative rather than confessional".[138]

Style and genre in autobiographies

Angelou's use of fiction-writing techniques such as dialogue, characterization, and development of theme, setting, plot, and language has often resulted in the placement of her books into the genre of autobiographical fiction.[139] As feminist scholar Maria Lauret state, Angelou has made a deliberate attempt in her books to challenge the common structure of the autobiography by critiquing, changing, and expanding the genre.[140] Scholar Mary Jane Lupton argues that all of Angelou's autobiographies conform to the genre's standard structure: they are written by a single author, they are chronological, and they contain elements of character, technique, and theme.[141] Angelou recognizes that there are fictional aspects to her books; Lupton agrees, stating that Angelou tends to "diverge from the conventional notion of autobiography as truth",[142] which parallels the conventions of much of African-American autobiography written during the abolitionist period of U.S. history, when as both Lupton and African-American scholar Crispin Sartwell put it, the truth was censored out of the need for self-protection.[142][143] Scholar Lyman B. Hagen places Angelou in the long tradition of African-American autobiography, but claims that Angelou has created a unique interpretation of the autobiographical form.[144]

According to African American literature scholar Pierre A. Walker, the challenge for much of the history of African-American literature was that its authors have had to confirm its status as literature before they could accomplish their political goals, which was why Angelou's editor Robert Loomis was able to dare her into writing Caged Bird by challenging her to write an autobiography that could be considered "high art".[145] Angelou acknowledges that she has followed the slave narrative tradition of "speaking in the first-person singular talking about the first-person plural, always saying I meaning 'we'".[99] Scholar John McWhorter calls Angelou's books "tracts"[105] that defend African-American culture and fight negative stereotypes. According to McWhorter, Angelou structures her books, which to him seem to be written more for children than for adults, to support her defense of Black culture. McWhorter sees Angelou as she depicts herself in her autobiographies "as a kind of stand-in figure for the Black American in Troubled Times".[105] Although McWhorter views Angelou's works as dated, he recognizes that "she has helped to pave the way for contemporary black writers who are able to enjoy the luxury of being merely individuals, no longer representatives of the race, only themselves.[146] Scholar Lynn Z. Bloom compares Angelou's works to the writings of Frederick Douglass, stating that both fulfilled the same purpose: to describe Black culture and to interpret it for their wider, white audiences.[147]

According to scholar Sondra O'Neale, although Angelou's poetry can be placed within the African-American oral tradition, her prose "follows classic technique in nonpoetic Western forms".[148] O'Neale states that although Angelou avoids using a "monolithic Black language",[149] she accomplishes, through direct dialogue, what O'Neale calls a "more expected ghetto expressiveness".[149] McWhorter finds both the language Angelou uses in her autobiographies and the people she depicts unrealistic, resulting in a separation between her and her audience. As McWhorter states, "I have never read autobiographical writing where I had such a hard time summoning a sense of how the subject talks, or a sense of who the subject really is".[150] McWhorter asserts, for example, that key figures in Angelou's books, like herself, her son Guy, and mother Vivian do not speak as one would expect, and that their speech is "cleaned up" for her readers.[151] Guy, for example, represents the young Black male, while Vivian represents the idealized mother figure, and the stiff language they use, as well as the language in Angelou's text, is intended to prove that Blacks can competently use standard English.[152]

McWhorter recognizes that much of the reason for Angelou's style was the "apologetic" nature of her writing.[105] When Angelou wrote Caged Bird at the end of the 1960s, one of the necessary and accepted features of literature at the time was "organic unity", and one of her goals was to create a book that satisfied that criteria.[145] The events in her books were episodic and crafted like a series of short stories, but their arrangements did not follow a strict chronology. Instead, they were placed to emphasize the themes of her books, which include racism, identity, family, and travel. English literature scholar Valerie Sayers has asserted that "Angelou's poetry and prose are similar". They both rely on her "direct voice", which alternates steady rhythms with syncopated patterns and uses similes and metaphors (e.g., the caged bird).[153] According to Hagen, Angelou's works have been influenced by both conventional literary and the oral traditions of the African-American community. For example, she has referenced over 100 literary characters throughout her books and poetry.[154] In addition, she uses the elements of blues music, including the act of testimony when speaking of one's life and struggles, ironic understatement, and the use of natural metaphors, rhythms, and intonations.[155] Angelou, instead of depending upon plot, uses personal and historical events to shape her books.[156]

References

Explanatory notes

- ^ According to Angelou, Annie Henderson built her business with food stalls catering to Black workers, which eventually developed into a store.[7]

- ^ Reviewer John M. Miller calls Angelou's performance of her song "All That Happens in the Marketplace" the "most genuine musical moment in the film".[29]

- ^ In Angelou's third book of essays, Letter to My Daughter (2009), she credits Cuban artist Celia Cruz as one of the greatest influences of her singing career, and later, credits Cruz for the effectiveness and impact of Angelou's poetry performances and readings.[31]

- ^ Guy Johnson, who as a result of this accident in Accra and one in the late 1960s, underwent a series of spinal surgeries. He, like his mother, became a writer and poet.[40]

- ^ Angelou called her friendship with Malcolm X "a brother/sister relationship".[44]

- ^ Angelou did not celebrate her birthday for many years, choosing instead to send flowers to King's widow Coretta Scott King.[48]

- ^ Angelou described their marriage, which she called "made in heaven",[53] in her second book of essays Even the Stars Look Lonesome (1997).

- ^ Angelou dedicated her 1993 book of essays Wouldn't Take Nothing for My Journey Now to Winfrey.[58]

- ^ In her fifth autobiography All God's Children Need Traveling Shoes (1987), Angelou recounts being identified, on the basis of her appearance, as part of the Bambara people, a subset of the Mande.[81]

- ^ See Gillespie et al., pp. 153–175.

- ^ In Angelou's essay, "My Grandson, Home at Last", published in Woman's Day in 1986, she describes the kidnapping and her response to it.[87]

- ^ In Angelou's third book of essays, Letter to My Daughter (2008), she related the first time she used legal pads to write.[94]

Citations

- ^ "Maya Angelou". SwissEduc.com. 17 December 2013.

- ^ Glover, Terry (December 2009). "Dr. Maya Angelou". Ebony. 65 (2): 67.

- ^ a b c Lupton, p. 4

- ^ Angelou (1969), p. 67

- ^ Angelou (1969), p. 6

- ^ Johnson, Claudia (2008). "Introduction". In Johnson, Claudia (ed.). Racism in Maya Angelou's I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings. Detroit, Michigan: Gale Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-7377-3905-3.

- ^ Angelou (1993), pp. 21–24

- ^ Angelou (1969), p. 52

- ^ Lupton, p. 5

- ^ "Maya Angelou I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings". BBC World Service Book Club. October 2005. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- ^ Gillespie et al., p. 22.

- ^ Gillespie et al., pp. 21–22.

- ^ a b Angelou (1969), p. 13.

- ^ Gillespie et al., p. 23.

- ^ a b Lupton, p. 15.

- ^ Gillespie et al., p. 28.

- ^ Angelou (1969), p. 279.

- ^ Long, Richard (1 November 2005). "35 Who Made a Difference: Maya Angelou". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- ^ Lauret, p. 120

- ^ Gillespie et al., p. 29.

- ^ Lupton, p. 6.

- ^ Hagen, p. xvi.

- ^ Gillespie et al., pp. 29, 31.

- ^ a b Angelou (1993), p. 95.

- ^ Gillespie et al., pp. 36–37.

- ^ Gillespie et al., p. 38.

- ^ Gillespie et al., p. 41.

- ^ Hagen, pp. 91–92.

- ^ a b c Miller, John M. "Calypso Heat Wave". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

- ^ Gillespie et al., p. 48.

- ^ Angelou (2008), p. 80

- ^ Gillespie et al., pp. 49–51.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Als, Hilton (5 August 2002). "Songbird: Maya Angelou takes another look at herself". The New Yorker. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

- ^ Hagen, p. 103.

- ^ Gillespie et al., p. 57.

- ^ Gillespie et al., p. 64.

- ^ Gillespie et al., p. 59.

- ^ Gillespie et al., p. 65.

- ^ Gillespie et al., p. 71.

- ^ Gillespie, p.156

- ^ Gillespie et al., pp. 74,75.

- ^ Braxton, p. 3.

- ^ Gillespie et al., pp. 79–80.

- ^ "Maya Angelou Interview". Academy of Achievement. p. 2. Retrieved 18 December 2013

- ^ Boyd, Herb (5 August 2010). "Maya Angelou Remembers James Baldwin". New York Amsterdam News. 100 (32): 17.

- ^ Gillespie et al., pp. 85–96.

- ^ a b Gillespie et al., p. 98.

- ^ a b c Minzesheimer, Bob (2008-03-26). "Maya Angelou celebrates her 80 years of pain and joy". USA Today. Retrieved 2008-05-30. Cite error: The named reference "80years" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Angelou, Maya (February 1982). "Why I Moved Back to the South". Ebony (37). Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- ^ Smith, Dinitia (23 January 2007). "A Career in Letters, 50 Years and Counting". The New York Times. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- ^ Brown, Avonie (4 January 1997). "Maya Angelou: The Phenomenal Woman Rises Again". New York Amsterdam News (88): 2.

- ^ Gillespie et al., p. 105.

- ^ Angelou, Maya (1997). Even the Stars Look Lonesome. New York: Random House. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-553-37972-3.

- ^ Gillespie et al., p. 119.

- ^ Gillespie et al., p. 110.

- ^ a b Moore, Lucinda (April 2003). "Growing Up Maya Angelou". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- ^ Winfrey, Oprah (December 2000). "Oprah Talks to Maya Angelou". O Magazine. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- ^ Angelou (1993), p. x.

- ^ Glover, Terry (December 2009). "Dr. Maya Angelou". Ebony (65): 67.

- ^ Cohen, Patricia (host) (1 October 2008). "Book Discussion on Letter to My Daughter". CSPAN Video Library (Documentary). The New York Times. Retrieved 13 December 2013.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Gillespie et al., p. 126.

- ^ a b c d Manegold, Catherine S. (20 January 1993). "An Afternoon with Maya Angelou; A Wordsmith at Her Inaugural Anvil". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 December 2013.

- ^ Berkman, Meredith (26 February 1993). "Everybody's All American". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 20 December 2013.

- ^ Gillespie et al., p. 142.

- ^ a b Long, p. 84.

- ^ a b Gillespie et al., p. 144.

- ^ a b c d e Younge, Gary (24 May 2002). "No surrender". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 December 2013.

- ^ a b c Gillepsie et al., p. 9.

- ^ Gillespie et al., p. 10.

- ^ Williams, Jeannie (10 January 2002). "Maya Angelou pens her sentiments for Hallmark". USA Today. Retrieved 20 December 2013.

- ^ Gillespie et al., p. 175.

- ^ Sayers, Valerie (27 March 2013). "'Mom & Me & Mom,' by Maya Angelou". The Washington Post. Retrieved 20 December 2013.

- ^ Mooney, Alexander (10 December 2007). "Clinton camp answers Oprah with Angelou". CNN Politics. Retrieved 20 December 2013.

- ^ Parker, Jennifer (19 January 2009). "From King's 'I Have a Dream' to Obama Inauguration". ABC News. Retrieved 20 December 2013.

- ^ Waldron, Clarence (11 November 2010). "Maya Angelou Donates Private Collection to Schomburg Center in Harlem". Jet Magazine. Retrieved 20 December 2013.

- ^ Lee, Felicia R (26 October 2010). "Schomburg Center in Harlem Acquires Maya Angelou Archive". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 December 2013.

- ^ Tate, p. 150.

- ^ Angelou, Maya (1984). "Shades and Slashes of Light". In Evans, Mari (ed.). Black Women Writers (1950–1980): A Critical Evaluation. Garden City, New York: Doubleday. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-385-17124-3.

- ^ Toppman, p. 145.

- ^ Gates, Jr., Henry L. (host) (2008). "African American Lives 2: The Past is Another Country (Part 4)". PBS. Retrieved 20 December 2013.

- ^ Angelou, Maya (1986). All God's Children Need Traveling Shoes. New York: Vintage Books. pp. 206–207. ISBN 978-0-679-73404-8.

- ^ Gates, Jr., Henry L. (host) (2008). "African American Lives 2: A Way out of No Way (Part 2)". PBS. Retrieved 20 December 2013.

- ^ Lupton, p. 2.

- ^ Gillespie et al., p. 156.

- ^ Gillespie et al., p. 155.

- ^ Gillespie et al., p. 129.

- ^ Lupton, p. 19

- ^ a b c d Younge, Gary (13 November 2013). "Maya Angelou: 'I'm fine as wine in the summertime". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 20 December 2013.

- ^ Gillespie et al., p. 150.

- ^ Gillespie et al., p. 162.

- ^ Pierce, Donna (5 January 2005). "Welcome to her world: Poet-author Maya Angelou blends recipes and memories in winning style". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ^ Crea, Joe (18 January 2011). "Maya Angelou's cookbook 'Great Food, All Day Long' exudes cozy, decadence". Northeast Ohio Media Group. Retrieved 20 December 2013.

- ^ Sarler, Carol (1989). "A Day in the Life of Maya Angelou". In Elliot, Jeffrey M (ed.). Conversations with Maya Angelou. Jackson, Mississippi: University Press. p. 217. ISBN 978-0-87805-362-9.

- ^ Angelou (2008), pp. 63—67

- ^ a b c d "Maya Angelou I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings". BBC World Service Book Club (interview). BBC. October 2005. Retrieved 20 December 2013.

- ^ Lupton, p. 98.

- ^ Lupton, p. 1.

- ^ Gilmor, Susan (7 April 2013). "Angelou: Writing about Mom emotional process". Winston-Salem Journal. Retrieved 14 April 2013.

- ^ a b c "Maya Angelou". Poetry Foundation. Retrieved 20 December 2013.

- ^ Italie, Hillel (6 May 2011). "Robert Loomis, Editor of Styron, Angelou, Retires". The Washington Times. Associated Press. Retrieved 20 December 2013.

- ^ Martin, Arnold (12 April 2001). "Making Books; Familiarity Breeds Content". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 December 2013.

- ^ Tate, p. 155.

- ^ McPherson, Dolly A. (1990). Order Out of Chaos: The Autobiographical Works of Maya Angelou. New York: Peter Lang Publishing. pp. 10–11. ISBN 0-8204-1139-6.

- ^ a b Moyer, Homer E (2003). The R.A.T. Real-World Aptitude Test: Preparing Yourself for Leaving Home. Herndon, New York: Capital Books. p. 297. ISBN 978-1-931868-42-6.

- ^ a b c d McWhorter, p. 40.

- ^ a b c Braxton, p. 4.

- ^ Long, p. 85.

- ^ a b Washington, Elsie B. (March/April 2002). "A Song Flung Up to Heaven". Black Issues Book Review. 4 (2): 56.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Brozan, Nadine (30 January 1993). "Chronicle". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- ^ "Maya Angelou, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings". National Coalition Against Censorship. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- ^ Foerstel, Herbert N. (2006). Banned in the USA: A Reference Guide to Book Censorship in Schools and Public Libraries. Westport, Connecticut: Information Age Publishing. pp. 195–6. ISBN 978-1-59311-374-2.

- ^ "The 100 Most Frequently Challenged Books of 1990–2000". American Library Association. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- ^ "Top 100 Banned/Challenged Books: 2000–2009". American Library Association. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- ^ Maughan, Shannon (3 March 2003). "Grammy Gold". Publishers Weekly. 250 (9): 38.

- ^ "Past Winners". Tony Awards. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- ^ "National Commission on the observance of International Women's Year, 1975 Appointment of Members and Presiding Officer of the Commission". The American Presidency Project. 28 March 1977. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- ^ "Sculptor, Painter among National Medal of Arts Winners". CNN.com. 20 December 2000. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- ^ Metzler, Natasha T. (1 June 2008). "Stars perform for president at Ford's Theatre gala". Fox News. Associated Press. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- ^ Norton, Jerry (15 February 2011). "Obama awards freedom medals to Bush, Merkel, Buffett". Reuters. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- ^ Glazier, Jocelyn A. (Winter 2003). "Moving Closer to Speaking the Unspeakable: White Teachers Talking about Race" (PDF). Teacher Education Quarterly. 30 (1). California Council on Teacher Education: 73–94. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- ^ Challener, Daniel D. Stories of Resilience in Childhood. London, England: Taylor & Francis. pp. 22–3. ISBN 978-0-8153-2800-1.

- ^ Boyatzis, Chris J. (February 1992). "Let the Caged Bird Sing: Using Literature to Teach Developmental Psychology". Teaching of Psychology. 19 (4): 221–2. doi:10.1207/s15328023top1904_5.

- ^ a b DeGout, p. 122.

- ^ Gillespie et al, p. 103

- ^ a b Lupton, p. 17

- ^ Hagen, p. 118.

- ^ a b Gillespie et al., p. 103.

- ^ Lupton, p. 18.

- ^ "Maya Angelou Still Rises". CBS News. 11 February 2011. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ^ Harris, Dana (7 July 2009). "Michael Jackson's mega-farewell". Variety. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ^ Neubauer, p. 10.

- ^ Hagen, p. 124.

- ^ a b Bloom, Harold (2001). Maya Angelou. Broomall, Pennsylvania: Chelsea House Publishers. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-7910-5937-1.

- ^ Hagen, p. 132.

- ^ DeGout, p. 129.

- ^ Bloom, Lynn Z. (1985). "Maya Angelou". Dictionary of Literary Biography African American Writers after 1955. Vol. 38. Detroit, Michigan: Gale Research Company. pp. 10–11. ISBN 0-8103-1716-8.

- ^ Burr, p. 181

- ^ Burr, p. 183.

- ^ Lupton, p. 29–30.

- ^ Lauret, p. 98

- ^ Lupton, p. 32.

- ^ a b Lupton, p. 34.

- ^ Sartwell, Crispin (1998). Act Like You Know: African-American Autobiography and White Identity. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-226-73527-6.

- ^ Hagen, pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b Walker, p. 92.

- ^ McWhorter, p. 41.

- ^ Bloom, Lynn Z. (2008). "The Life of Maya Angelou". In Johnson, Claudia (ed.). Racism in Maya Angelou's I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings. Detroit, Michigan: Gale Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-7377-3905-3.

- ^ O'Neale, p. 32.

- ^ a b O'Neale, p. 34.

- ^ McWhorter, p. 39.

- ^ McWhorter, p. 38.

- ^ McWhorter, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Sayers, Valerie (28 September 2008). "Songs of Herself". Washington Post. Retrieved 22 December 2013.

- ^ Hagen, p. 63.

- ^ Hagen, p. 61.

- ^ Lupton, p. 142.

Works cited

- Angelou, Maya (1969). I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-375-50789-2

- Angelou, Maya (1993). Wouldn't Take Nothing for My Journey Now. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-394-22363-6

- Angelou, Maya (2008). Letter to My Daughter. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-8129-8003-5

- Braxton, Joanne M., ed. (1999). Maya Angelou's I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings: A Casebook. New York: Oxford Press. ISBN 978-0-19-511606-9

- Braxton, Joanne M. "Symbolic Geography and Psychic Landscapes: A Conversation with Maya Angelou", pp. 3–20

- Tate, Claudia. "Maya Angelou: An Interview", pp. 149–158

- Burr, Zofia. (2002). Of Women, Poetry, and Power: Strategies of Address in Dickinson, Miles, Brooks, Lorde, and Angelou. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-02769-7

- DeGout, Yasmin Y. (2009). "The Poetry of Maya Angelou: Liberation Ideology and Technique". In Bloom's Modern Critical Views—Maya Angelou, Harold Bloom, ed. New York: Infobase Publishing, pp. 121–132. ISBN 978-1-60413-177-2

- Gillespie, Marcia Ann, Rosa Johnson Butler, and Richard A. Long. (2008). Maya Angelou: A Glorious Celebration. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-385-51108-7

- Hagen, Lyman B. (1997). Heart of a Woman, Mind of a Writer, and Soul of a Poet: A Critical Analysis of the Writings of Maya Angelou. Lanham, Maryland: University Press. ISBN 978-0-7618-0621-9

- Lauret, Maria (1994). Liberating Literature: Feminist Fiction in America. New York: Routledge Press. ISBN 978-0-415-06515-3

- Long, Richard. (2005). "Maya Angelou". Smithsonian 36, (8): pp. 84–85

- Lupton, Mary Jane (1998). Maya Angelou: A Critical Companion. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-30325-8

- McWhorter, John. (2002). "Saint Maya." The New Republic 226, (19): pp. 35–41.

- O'Neale, Sondra. (1984). "Reconstruction of the Composite Self: New Images of Black Women in Maya Angelou's Continuing Autobiography", in Black Women Writers (1950–1980): A Critical Evaluation, Mari Evans, ed. Garden City, N.Y: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-17124-3

- Toppman, Lawrence. (1989). "Maya Angelou: The Serene Spirit of a Survivor", in Conversations with Maya Angelou, Jeffrey M. Elliot, ed. Jackson, Mississippi: University Press. ISBN 978-0-87805-362-9

- Walker, Pierre A. (October 1995). "Racial Protest, Identity, Words, and Form in Maya Angelou's I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings". College Literature 22, (3): pp. 91–108.

External links

- Official website

- Maya Angelou at IMDb

- Maya Angelou at the Internet Broadway Database

- Maya Angelou at the Internet Off-Broadway Database

- Maya Angelou

- 1928 births

- Living people

- 20th-century women writers

- 20th-century American writers

- American memoirists

- African-American writers

- American activists

- American dramatists and playwrights

- African-American dramatists and playwrights

- American people of Sierra Leonean descent

- American television actresses

- African-American poets

- American women poets

- American poets

- Grammy Award-winning artists

- Lecturers

- Actresses from St. Louis, Missouri

- American people of Mende descent

- Rape victims

- Wake Forest University faculty

- American women writers

- Writers from Arkansas

- Writers from Missouri

- African-American non-fiction writers

- African-American actresses