Jackson, Mississippi: Difference between revisions

→Demographics: redundant |

|||

| Line 321: | Line 321: | ||

The median income for a household in the city was $30,414, and the median income for a family was $36,003. Males had a median income of $29,166 versus $23,328 for females. The [[per capita income]] for the city was $17,116. About 19.6% of families and 23.5% of the population were below the [[poverty line]], including 33.7% of those under age 18 and 15.7% of those age 65 or over.<ref>[http://censtats.census.gov/data/MS/1602836000.pdf Profile of General Demographic Characteristics: 2000], [[United States Census Bureau]]</ref> |

The median income for a household in the city was $30,414, and the median income for a family was $36,003. Males had a median income of $29,166 versus $23,328 for females. The [[per capita income]] for the city was $17,116. About 19.6% of families and 23.5% of the population were below the [[poverty line]], including 33.7% of those under age 18 and 15.7% of those age 65 or over.<ref>[http://censtats.census.gov/data/MS/1602836000.pdf Profile of General Demographic Characteristics: 2000], [[United States Census Bureau]]</ref> |

||

Jackson ranks number 10 in the nation in concentration of African-American same-sex couples.<ref>[http://www.urban.org/publications/900695.html Facts and Findings from ''The Gay and Lesbian Atlas'']</ref> |

|||

In 2006, the Center for Immigrant Studies found Mississippi had the highest rate of growth in immigrant population of all states. The Jackson metro area is one of the South's emerging destinations for immigrants. |

In 2006, the Center for Immigrant Studies found Mississippi had the highest rate of growth in immigrant population of all states. The Jackson metro area is one of the South's emerging destinations for immigrants. |

||

Revision as of 22:15, 26 July 2009

City of Jackson | |

|---|---|

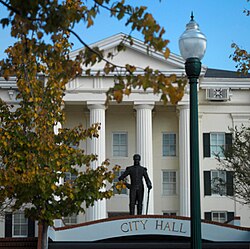

Jackson City Hall | |

|

| |

| Nickname: Crossroads of the South | |

| Motto(s): The city of Grace and Benevolence | |

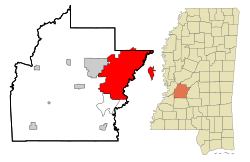

Location in Hinds County, Mississippi | |

Location of Mississippi in the United States | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Mississippi |

| Counties | Hinds, Madison, Rankin |

| Founded | 1822 |

| Incorporation | 1822 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Strong Mayor-Council |

| • Mayor | Harvey Johnson, Jr. |

| • City Council | Jeff Weill, Chokwe Lamumba, Kenneth I. Stokes, Frank Bluntson, Charles Tillman, Tony Yarber, Margaret C. Barrett-Simon |

| • Chief of Police | Tyrone Lewis[1] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 106.8 sq mi (276.7 km2) |

| • Land | 104.9 sq mi (271.7 km2) |

| • Water | 1.9 sq mi (5.0 km2) |

| Elevation | 279 ft (85 m) |

| Population (2008 Census estimate) | |

| • Total | 173,861 |

| • Density | 1,657/sq mi (640/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP codes | 39200-39299 |

| Area code(s) | 601, 769 |

| FIPS code | 28-36000Template:GR |

| GNIS feature ID | 0711543Template:GR |

| Website | http://www.jacksonms.gov |

| For additional city data see City-Data | |

Jackson is the capital and the most populous city of the U.S. state of Mississippi. It is one of two seats in Hinds County (the town of Raymond is the other), but the city also contains areas in Madison and Rankin Counties. The 2000 census recorded Jackson's population at 184,256, but according to July 1, 2008 estimates, the city's population was 173,861 and its five-county metropolitan area had a population of 537,285.[2][3] The Jackson-Yazoo City combined statistical area, consisting of the Jackson metropolitan area and Yazoo City micropolitan area, has a population of 565,749, making it the 88th-largest metropolitan area in the United States.[4]

The current slogan for the city is Jackson, Mississippi: City with Soul.[5] The city is named after President Andrew Jackson.

History

Native Americans

The area which is now Jackson was originally part of the Choctaw Nation. Under pressure from the US government, the Choctaw Native Americans agreed to removal from all lands east of the Mississippi River under the terms of the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek in 1830.[6] Although many Choctaws then moved to present-day Oklahoma, a significant number chose to stay in their homeland, citing Article XIV of the treaty.[7] Today, most Choctaws, who are part of the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians, live on several Indian communities located throughout the state. The largest community is located in Choctaw, MS, 100 mi northeast of the city.

Founding and antebellum period (to 1860)

The area that is now Jackson was initially referred to as Parkerville[8] and was settled by Louis LeFleur, a French Canadian trader, along the historic Natchez Trace trade route. The area then became known as LeFleur's Bluff[9]. LeFleur's Bluff was founded based on the need for a centrally located capital for the state of Mississippi. In 1821, the Mississippi General Assembly, meeting in the then-capital of Natchez, had sent Thomas Hinds (for whom Hinds County is named), James Patton, and William Lattimore to look for a site. After surveying areas north and east of Jackson, they proceeded southwest along the Pearl River until they reached LeFleur's Bluff in Hinds County. Their report to the General Assembly stated that this location had beautiful and healthful surroundings, good water, abundant timber, navigable waters, and proximity to the trading route Natchez Trace. And so, a legislative Act passed by the Assembly on November 28, 1821, authorized the location to become the permanent seat of the government of the state of Mississippi.

Jackson is named after the seventh President of the United States, Andrew Jackson, in recognition for his victory in the Battle of New Orleans.

During the late 18th century and early 19th century, the area was traversed by the Natchez Trace, on which a trading post stood before a treaty with the Choctaw, the Treaty of Doak's Stand in 1820, formally opened the area for non-native American settlers.

Jackson was originally planned, in April 1822, by Peter Van Dorn in a "checkerboard" pattern advocated by Thomas Jefferson, in which city blocks alternated with parks and other open spaces, giving the appearance of a checkerboard. This plan has not lasted to the present day.

The state legislature first met in Jackson on December 23, 1822.

In 1839, Jackson was the site of the passage of the first state law that permitted married women to own and administer their own property.

Jackson was first linked with other cities by rail in 1840. An 1844 map shows Jackson linked by an east-west rail line running between Vicksburg, Raymond, and Brandon. Unlike Vicksburg, Greenville, and Natchez, Jackson is not located on the Mississippi River, and did not develop like those cities from river commerce. Instead, railroads would later spark growth of the city in the decades after the American Civil War.

American Civil War and late nineteenth century (1861-1900)

Despite its small population, during the Civil War, Jackson became a strategic center of manufacturing for the Confederate States of America. In 1863, during the campaign which ended in the capture of Vicksburg, Union forces captured Jackson during two battles—once before the fall of Vicksburg and once after the fall of Vicksburg.

On May 13, 1863, Union forces won the first Battle of Jackson, forcing Confederate forces to flee northward towards Canton. On May 15, Union troops under the command of William Tecumseh Sherman burned and looted key facilities in Jackson, a strategic manufacturing and railroad center for the Confederacy. After driving the Confederate forces out of Jackson, Union forces turned west once again and engaged the Vicksburg defenders at the Battle of Champion Hill in nearby Edwards. The siege of Vicksburg began soon after the Union victory at Champion Hill. Confederate forces began to reassemble in Jackson in preparation for an attempt to break through the Union lines surrounding Vicksburg and end the siege there. The Confederate forces in Jackson built defensive fortifications encircling the city while preparing to march west to Vicksburg.

Confederate forces marched out of Jackson to break the siege of Vicksburg in early July 1863. However, unknown to them, Vicksburg had already surrendered on July 4, 1863. General Ulysses S. Grant dispatched General Sherman to meet the Confederate forces heading west from Jackson. Upon learning that Vicksburg had already surrendered, the Confederates retreated back into Jackson, thus beginning the Siege of Jackson, which lasted for approximately one week. Union forces encircled the city and began an artillery bombardment. One of the Union artillery emplacements still remains intact on the grounds of the University of Mississippi Medical Center in Jackson. Another Federal position is still intact on the campus of Millsaps College. One of the Confederate Generals defending Jackson was former United States Vice President John C. Breckenridge. On July 16, 1863, Confederate forces slipped out of Jackson during the night and retreated across the Pearl River. Union forces completely burned the city after its capture this second time, and the city earned the nickname "Chimneyville" because only the chimneys of houses were left standing. The northern line of Confederate defenses in Jackson during the siege was located along a road near downtown Jackson, now known as Fortification Street.

Today there are few antebellum structures left standing in Jackson. One surviving structure is the Governor's Mansion, built in 1842, which served as Sherman's headquarters. Another is the Old Capitol building, which served as the home of the Mississippi state legislature from 1839 to 1903. There the Mississippi legislature passed the ordinance of secession from the Union on January 9, 1861, becoming the second state to secede from the United States.

In 1875 the Red Shirts were formed, one of a second wave of insurgent paramilitary organizations that essentially operated as "the military arm of the Democratic Party" to take back political power from the Republicans and to drive blacks from the polls.[10] Democrats regained control of the state legislature in 1876. The constitutional convention of 1890, which produced Mississippi's Constitution of 1890, was also held at the capitol. This was the first of new constitutions or amendments ratified in southern states through 1908 that effectively disfranchised African Americans and poor whites, through provisions making voter registration more difficult: such as poll taxes, residency requirements, and literacy tests. These provisions survived a Supreme Court challenge in 1898.[11][12] As 20th century Supreme Court decisions began to find such provisions unconstitutional, Mississippi and other southern states rapidly devised new methods to continue disfranchisement of most blacks.

The so-called New Capitol replaced the older structure upon its completion in 1903, and today the Old Capitol is a historical museum. A third important surviving antebellum structure is the Jackson City Hall, built in 1846 for less than $8,000. It is said that Sherman, a Mason, spared it because it housed a Masonic Lodge, though a more likely reason is that it housed an army hospital.

Early twentieth century (1901-1960)

Pulitzer Prize-winning author Eudora Welty was born in Jackson in 1909, lived most of her life in the Belhaven section of the city, and died there in 2001. Her memoir of development as a writer, One Writer's Beginnings (1984), presented a charming picture of the city in the early 20th century. The main Jackson Public Library was named in her honor.

Highly acclaimed African-American author Richard Wright, a native of Roxie, Mississippi, lived in Jackson as an adolescent and young man in the 1910s and 1920s. He related his experience in his memoir Black Boy (1945). He described the harsh and largely terror-filled life poor African-Americans experienced in the South and northern ghettos under segregation in the early twentieth century.

Jackson's economic growth was stimulated in the 1930s by the discovery of natural gas fields nearby.

During World War II, Hawkins Field in northwest Jackson became a major airbase. Among other facilities and units, the Royal Netherlands Military Flying School was established there, after Nazi Germany occupied the Netherlands. From 1941, the base trained all Dutch military aircrews.

Civil Rights Movement in Jackson

Since 1960, Jackson has undergone a series of dramatic changes and growth. As the state capital, it became a site for civil rights activism that was heightened by mass demonstrations during the 1960s. On May 24, 1961, during the African-American Civil Rights Movement, more than 300 Freedom Riders were arrested in Jackson for disturbing the peace after they disembarked from their bus. They were riding the bus to demonstrate against segregation on public transportation.[13] Although the Freedom Riders had intended New Orleans, Louisiana as their final destination, Jackson was the farthest that any of them managed to travel.

Efforts to desegregate Jackson facilities began before the Freedom Rides when nine Tougaloo students were arrested for attempting to read books in the "white only" public library. Founded as a historically black college (HBCU) by the American Missionary Movement after the Civil War, Tougaloo College brought both black and white students together to work for civil rights. It also created partnerships with neighboring mostly white Millsaps College to work with student activists. It has been recognized as a site on the Civil Rights Trail by the National Park Service.[14] After the Freedom Rides, students and activists of the Freedom Movement launched a series of merchant boycotts[15], sit-ins and protest marches[16], from 1961 to 1963.

In Jackson, shortly after midnight on June 12, 1963, Medgar Evers, civil rights activist and leader of the Mississippi chapter of the NAACP, was murdered by Byron De La Beckwith, a white supremacist. Thousands marched in his funeral procession to protest the assassination.[17] In 1994, prosecutors Ed Peters and Bobby DeLaughter finally obtained a murder conviction of De La Beckwith. A portion of U.S. Highway 49, all of Delta Drive and Jackson-Evers International Airport was named in honor of Medgar Evers. During 1963 and 1964, organizers did voter education and voter registration. In a pilot project, they rapidly registered 80,000 voters across the state, demonstrating the desire of African Americans to vote. In 1964 they created the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party as an alternative to the all-white state party, and sent an alternate slate of candidates to the national party convention.

Mississippi continued segregation and the disfranchisement of most African Americans until after the Civil Rights Movement gained passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Acts of 1965. In June 1966, Jackson was also the terminus of the James Meredith March, organized by James Meredith, the first African-American to enroll at the University of Mississippi. The march, which began in Memphis, Tennessee, was an attempt to garner support for implementation of civil rights legislation. It was accompanied by a new drive to register African-Americans to vote in Mississippi. In this latter aim, it succeeded in registering between 2,500 and 3,000 black Mississippians to vote. The march ended on June 26 after Meredith, who had been wounded by a sniper's bullet earlier on the march, addressed a large rally of some 15,000 people in Jackson.

In September 1967 the Ku Klux Klan bombed the synagogue building of the Beth Israel Congregation in Jackson, and in November bombed the house of its rabbi, Dr. Perry Nussbaum.[18]

Gradually the old barriers came down. Since then, both whites and African Americans in the state have had a high rate of voter registration and turnout.[19]

Recent History

The first successful cadaveric lung transplant was performed at the University of Mississippi Medical Center in Jackson in June 1963 by Dr. James Hardy. Hardy transplanted the cadaveric lung into a patient suffering from lung cancer. The patient survived for eighteen days before dying of kidney failure.

Since 1968, Jackson has been the home of Malaco Records, one of the leading record companies for gospel and soul music in the United States. In January 1973, Paul Simon recorded the song "Learn How To Fall", found on the album There Goes Rhymin' Simon, in Jackson at the Malaco Recording Studios.

On May 15, 1970 police killed two students and wounded 12 at Jackson State University (then called Jackson State College) after a protest of the Vietnam War included overturning and burning some cars. These killings occurred ten days after the National Guard killed four students in an anti-war protest at Kent State University in Ohio, and were part of national social unrest.[20] Newsweek cited the Jackson State killings in its issue of 18 May when it suggested that U.S. President Richard Nixon faced a new home front.

In 1997, Harvey Johnson, Jr. became the city's first African-American mayor. During his term, he proposed the creation of a convention center, in hopes of attracting business to the city. In 2004, during his second term, 66 percent of the voters passed a referendum for a tax to build the Convention Center.[21] As a result of this vote, many new development projects are underway in Downtown Jackson.

Mayor Johnson was replaced by Frank Melton on July 4, 2005. Melton has subsequently generated controversy through his unconventional behavior, which has included acting as a law enforcement officer. A dramatic spike in crime has also ensued, despite Melton's efforts to reduce crime. The lack of jobs has contributed to crime.[22]

2007 saw a historic first for Mississippi as Hinds County sheriff Malcolm McMillin was appointed as the new police chief in Jackson. McMillin was both the county sheriff and city police chief until 2009 when he stepped down to the disagreements with the current mayor. Mayor Frank Melton died in May 2009 and City Councilman Leslie McLemore served as acting mayor of Jackson until July 2009 when former Mayor Harvey Johnson assumed the Mayor position.[23]

Geography, geology, and climate

Jackson is located on the Pearl River, and is served by the Ross Barnett Reservoir, which forms a section of the Pearl River and is located northeast of Jackson on the border between Madison and Rankin counties. A tiny portion of the city containing Tougaloo College lies in Madison County, bounded on the west by I-220 and on the east by US 51 and I-55. A second portion of the city is located in Rankin County. In the 2000 census, 183,723 of the city's 184,256 residents (99.7%) lived in Hinds County and 533 (0.3%) in Madison County. Although no Jackson residents lived in the Rankin County portion in 2000, that figure had risen to 72 by 2006.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 106.8 square miles (276.7 km²), of which, 104.9 square miles (271.7 km²) of it is land and 1.9 square miles (5.0 km²) of it is water. The total area is 1.80 percent water.

Jackson sits atop the Jackson Volcano and is the only capital city or major population center in the United States to have this feature. The peak of the volcano is located 2900 feet directly below the Mississippi Coliseum.[24]

Jackson possesses a humid subtropical climate, with hot, humid summers and mild winters. Rain is evenly spread throughout the year, and snow can fall in wintertime, although heavy snowfall is relatively rare. Much of Jackson's rainfall occurs during thunderstorms. Thunder is heard on roughly 70 days per annum. Jackson lies in a region prone to severe thunderstorms which can produce large hail, damaging winds and tornadoes. Among one of the most notable tornado events was the F5 Candlestick Park Tornado on March 3, 1966 which destroyed the shopping center of the same name and surrounding businesses and residential areas killing 19 in South Jackson.

| Monthly Normal and Record High and Low Temperatures | ||||||||||||

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rec High °F (°C) | 83 (28.3) | 85 (29.4) | 89 (31.6) | 94 (34.4) | 99 (37.2) | 105 (40.5) | 106 (41.1) | 107 (41.6) | 104 (40) | 95 (35) | 88 (31.1) | 84 (28.8) |

| Norm High °F (°C) | 55.1 (12.8) | 60.3 (15.7) | 68.1 (20.05) | 75 (23.8) | 82.1 (27.8) | 88.9 (31.6) | 91.4 (33) | 91.4 (33) | 86.4 (30.2) | 76.8 (24.8) | 66.3 (19.05) | 57.9 (14.4) |

| Norm Low °F (°C) | 35 (1.6) | 38.2 (3.4) | 45.4 (7.4) | 51.7 (10.9) | 61 (16.1) | 68.1 (20.05) | 71.4 (21.8) | 70.3 (21.3) | 64.6 (18.1) | 52 (11.1) | 43.4 (6.3) | 37.3 (2.9) |

| Rec Low °F (°C) | 2 (-16.6) | 10 (-12.2) | 15 (-9.4) | 27 (-2.7) | 38 (3.3) | 47 (8.3) | 51 (10.5) | 54 (12.2) | 35 (1.6) | 26 (-3.3) | 17 (-8.3) | 4 (-15.5) |

| Precip in. (mm) | 5.67 (144) | 4.5 (114.3) | 5.74 (145.8) | 5.98 (151.9) | 4.86 (123.4) | 3.82 (97) | 4.69 (119.1) | 3.66 (93) | 3.23 (82) | 3.42 (86.9) | 5.04 (128) | 5.34 (135.6) |

| Source: Weather.com | ||||||||||||

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1860 | 3,191 | — | |

| 1870 | 4,234 | 32.7% | |

| 1880 | 5,204 | 22.9% | |

| 1890 | 5,920 | 13.8% | |

| 1900 | 7,816 | 32.0% | |

| 1910 | 21,262 | 172.0% | |

| 1920 | 22,817 | 7.3% | |

| 1930 | 48,282 | 111.6% | |

| 1940 | 62,107 | 28.6% | |

| 1950 | 98,271 | 58.2% | |

| 1960 | 144,422 | 47.0% | |

| 1970 | 153,968 | 6.6% | |

| 1980 | 202,895 | 31.8% | |

| 1990 | 196,637 | −3.1% | |

| 2000 | 184,286 | −6.3% | |

| 2006 (est.) | 176,614 |

Jackson remained a small town for much of the 19th century. Before the American Civil War, Jackson's population remained small, particularly in contrast to those towns located along the commerce-laden Mississippi River. Despite the city's status as the state capital, the 1850 census counted only 1,881 residents, and by 1900 the population of Jackson had grown only to approximately 8,000. It was during this period, roughly between 1890 and 1930, that Meridian became Mississippi's largest city. By 1944, Jackson's population had risen to some 70,000 inhabitants. Since that time, it has continuously been the largest city in the state. Large-scale growth, however, did not come until the 1970s, after the turbulence of the Civil Rights Movement. The 1980 census counted over 200,000 residents in the city for the first time. Since then, Jackson has steadily seen a decline in its population, while its suburbs have evidenced a boom.

As of the censusTemplate:GR of 2000, there were 184,256 people, 67,841 households, and 44,488 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,756.4 people per square mile (678.2/km²). There were 75,678 housing units at average density of 278.5/km² (721.4/sq mi). The racial makeup of the city was 70.6% Black or African American, 27.8% White, 0.1% Native American, 0.6% Asian, 0.01% Pacific Islander, 0.2% from other races, and 0.7% from two or more races. 0.8% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 67,841 households out of which 39.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 35.4% were married couples living together, 25.3% had a female householder with no husband present, and 34.4% were non-families. 28.9% of all households were made up of individuals and 9.0% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.61 and the average family size was 3.24. Same-sex couple households compromised 0.8 % of all househoulds.[25]

The age of the population was spread out with 28.5% under the age of 18, 12.4% from 18 to 24, 29.1% from 25 to 44, 19.1% from 45 to 64, and 10.9% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 31 years. For every 100 females, there were 86.9 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 81.5 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $30,414, and the median income for a family was $36,003. Males had a median income of $29,166 versus $23,328 for females. The per capita income for the city was $17,116. About 19.6% of families and 23.5% of the population were below the poverty line, including 33.7% of those under age 18 and 15.7% of those age 65 or over.[26]

In 2006, the Center for Immigrant Studies found Mississippi had the highest rate of growth in immigrant population of all states. The Jackson metro area is one of the South's emerging destinations for immigrants.

Crime

The 14th annual (2007) "City Crime Rankings: Crime in Metropolitan America" ranks Jackson as the 23rd most dangerous city in America. [27]

According to Federal Bureau of Investigation Uniform Crime Reports, from 2005 to 2008, violent crime jumped 238 percent in Jackson - from 1,225 reported incidents in 2005 to 4,140 in 2008. Also, while the city's population decreased 3 percent from 180,400 in 2005 to about 175,000 in 2008, property crime increased more than 8 percent, from 12,008 reported incidents in 2005 to 13,042 in 2008. [28]

According to an FBI report released in June 2009, Jackson's murder rate ranked 4th in the nation, behind New Orleans, Louisiana, St. Louis, Missouri and Baltimore, Maryland, with a rate of 36 per 100,000 residents for the 2008 year.[29] For burglary, it was second behind Flint, Michigan with a rate of 248 per 100,000 residents.[29] While violent crime was up 9.3 percent and property crimes had gone up 4.6 percent in the year of the FBI report, nationwide violent crime fell 2.5 percent and property crime fell by 1.6 percent.[29]

Transportation

Air travel

Jackson is served by Jackson-Evers International Airport, located at Allen C. Thompson Field, east of the city in Flowood in Rankin County. Its IATA code is JAN. The airport has non-stop service to 12 cities throughout the United States and is served by 6 scheduled carriers (American, Delta, Continental, Southwest, Northwest, and US Airways)

On 22 December 2004, Jackson City Council members voted 6-0 to rename Jackson International Airport in honor of slain civil rights leader and field secretary for the Mississippi chapter of the NAACP, Medgar Evers. This decision took effect on 22 January 2005.

Formerly Jackson was served by Hawkins Field Airport, located in northwest Jackson, with IATA code HKS, which is now used for private air traffic only.

Underway is the Airport Parkway project. The environmental impact study is complete and final plans are drawn and awaiting Mississippi Department of Transportation approval. Right-of-way acquisition is underway at an estimated cost of $19 million. The Airport Parkway will connect High Street in downtown Jackson to Mississippi Highway 475 in Flowood at Jackson-Evers International Airport. The Airport Parkway Commission consists of the Mayor of Pearl, the Mayor of Flowood, and the Mayor of Jackson, as the Airport Parkway will run through and have access from each of these three cities.

Ground transportation

Interstate highways

![]() Interstate 20

Interstate 20

Runs east-west from near El Paso, Texas to Florence, South Carolina. Jackson is roughly halfway between Dallas, Texas and Atlanta, Georgia. The highway is six lanes from Interstate 220 to MS 468 in Pearl.

![]() Interstate 55

Interstate 55

Runs north-south from Chicago through Jackson towards Brookhaven, McComb, and the Louisiana state line to New Orleans. Jackson is roughly halfway between New Orleans and Memphis, Tennessee. The highway maintains eight to ten lanes in northern part of city, six lanes in the center and four lanes south of I-20.

![]() Interstate 220

Interstate 220

Connects Interstates 55 and 20 on the north and west sides of the city and is four lanes throughout its route.

U.S. highways

![]() U.S. Highway 49

U.S. Highway 49

Runs north-south from the Arkansas state line at Lula via Clarksdale and Yazoo City, towards Hattiesburg and Gulfport. It bypasses the city via I-20 and I-220

![]() U.S. Highway 51

U.S. Highway 51

Known in Jackson as State Street, roughly parallels Interstate 55 from the I-20/I-55 western split to downtown. It multiplexes with I-55 from Pearl/Pascagoula St northward to County Line Road, where the two highways split.

![]() U.S. Highway 80

U.S. Highway 80

Roughly parallels Interstate 20.

State highways

![]() Mississippi Highway 18

Mississippi Highway 18

Runs southwest towards Raymond and Port Gibson; southeast towards Bay Springs and Quitman.

![]() Mississippi Highway 25

Mississippi Highway 25

Some parts of this road are known as Lakeland Drive, which runs northeast towards Carthage and Starkville.

Other roads

In addition, Jackson is served by the Natchez Trace Parkway, which runs from Natchez to Nashville, Tennessee.

Bus service

JATRAN (Jackson Transit System) operates hourly or half-hourly during daytime hours on weekdays, and mostly hourly on Saturdays. No evening or Sunday service is operated.

Railroads

Jackson is served by the Canadian National Railway (formerly the Illinois Central Railroad). The Kansas City Southern Railway also serves the city. The Canadian National has a medium-sized yard downtown which Mill Street parallels and the Kansas City Southern has a large classification yard in Richland. Amtrak, the national passenger rail system, provides service to Jackson. The Amtrak station is located at 300 West Capitol Street. Amtrak's southbound City of New Orleans provides service from Jackson to New Orleans and some points between. The northbound City of New Orleans provides service from Jackson to Memphis, Carbondale, Champaign-Urbana, Chicago and some points between. Efforts to establish service with another Amtrak train, the Crescent Star, an extension of the Crescent westward from Meridian, Mississippi to Dallas, Texas, failed in 2003.

Industry

Jackson is home to several major industries. These include electrical equipment and machinery, processed food, and primary and fabricated metal products. The surrounding area supports agricultural development of livestock, soybeans, cotton, and poultry.

Publicly traded companies

The following companies are headquartered in Jackson:

- Cal-Maine Foods, Inc. (NASDAQ:CALM)

- EastGroup Properties Inc. (NYSE:EGP)

- Parkway Properties, Inc. (NYSE:PKY)

- Trustmark Corporation (NASDAQ:TRMK)

Religion

- Jackson is the episcopal see of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Jackson

- Jackson is home to the original campus of the Reformed Theological Seminary

- Jackson is the headquarters of the Church of Christ (Holiness) U.S.A., founded by Charles Price Jones

- Jackson is home to Beth Israel Congregation, the only Jewish congregation in Jackson and the largest in Mississippi.[30]

Cultural organizations and institutions

- Ballet Mississippi

- Celtic Heritage Society of Mississippi

- International Museum of Muslim Cultures

- Jackson State University Botanical Garden

- Jackson Zoo

- Mississippi Agriculture and Forestry Museum

- Mississippi Arts Center

- Mississippi Chorus

- Mississippi Department of Archives and History, which contains the state archives and records.

- Mississippi Heritage Trust

- Mississippi Hispanic Association

- Mississippi Immigrants Rights Alliance

- Mississippi Museum of Art

- Mississippi Opera

- Mississippi Symphony Orchestra (MSO), formerly the Jackson Symphony Orchestra, founded in 1944

- Municipal Art Gallery

- Mynelle Gardens

- New Stage Theatre

- Russell C. Davis Planetarium

- Smith-Robertson Museum and Cultural Center

Political structures

In 1985, Jackson voters opted to replace the three-person mayor-commissioner system with a city council. Jackson's city council members represent the city's seven wards, and the body is headed by the mayor who is elected by the entire city.

Jackson's current mayor is Harvey Johnson, Jr..

Education

Jackson is home to the international headquarters of Phi Theta Kappa, an honor society for students enrolled in two-year colleges.

Colleges and universities

- Belhaven College (1883)

- Hinds Community College's campuses in Jackson are the Nursing/Allied Health Center (1970) and the Academic/Technical Center

- Jackson State University (1877)

- Millsaps College (1890)

- Mississippi College School of Law (1930)

- Reformed Theological Seminary (1966)

- Tougaloo College (1869)

- University of Mississippi Medical Center (1955), health sciences campus of the University of Mississippi

- Wesley Biblical Seminary (1974)

Public high schools

- Bailey Magnet High School

- Callaway High School

- Career Development Center

- Forest Hill High School

- Jim Hill High School

- Lanier High School

- Murrah High School

- Provine High School

- Wingfield High School

Private high schools

- Christ Missionary & Industrial (CM&I) College High School

- Hillcrest Christian School

- Jackson Academy

- The Veritas School

Private Schools

- Magnolia Speech School [1]

- St. Andrew's Episcopal Lower School - South Campus

Media

Newspapers

Daily

- The Clarion-Ledger - statewide daily newspaper

Weekly

- Jackson Advocate - weekly newspaper and nation's oldest newspaper serving the state's African-American community

- Jackson Free Press - free newsweekly tabloid featuring heavy content on arts and entertainment

- The Mississippi Link - weekly newspaper serving the state's African-American community

- Mississippi Business Journal - weekly newspaper, with focus on business and economic development

- The Northside Sun - weekly newspaper, with focus on the northeastern portion of the Jackson Metropolitan area

Historic

- The Mississippian Daily Gazette - also often referred to as The Jackson Mississippian because of its location, circulated during the 19th century, a major newspaper during the Civil War

- The Standard - circulated during the 19th century, after the Civil War The Eastern Clarion moved to Jackson and merged with The Standard, soon changed name to The Clarion

- State Ledger - circulated during the 19th century, in 1888 The Clarion merged with the State Ledger and became known as The Clarion-Ledger

- The Jackson Daily News - originally known as The Jackson Evening Post in 1882, changed the name to The Jackson Daily News in 1907, purchased along with The Clarion-Ledger by Gannett in 1982

Magazines

- Mississippi Magazine - people, places and events with emphasis on homes, cooking and entertainment

- B Fit and Healthy Magazine - health and fitness magazine for Mississippians

- Victories in Metro Jackson - Christian athletics magazine

- "PORTICO jackson" - monthly lifestyle magazine about people, places, food, fashion, etc.

Publishing

- University Press of Mississippi, the state's only not-for-profit publishing house and collective publisher for Mississippi's eight state universities, producing works on local history, culture and society

Television

- Channel 3, WLBT: NBC

- Channel 8, WBXK: dark

- Channel 10, WBMS: independent (simulcast of WXMS)

- Channel 12, WJTV: CBS

- Channel 16, WAPT: ABC

- Channel 23, W23BC: Colours TV, America One (owned by Jackson State University)

- Channel 27, WXMS: independent

- Channel 29, WMPN: PBS/Mississippi Public Broadcasting

- Channel 34, WRBJ: The CW

- Channel 35, WUFX: My Network TV

- Channel 40, WDBD: Fox

- Channel 49, WJXF-LP: dark

- Channel 53, WJMF-LP: dark

- Channel 64, WJKO-LP: TBN

FM radio

|

|

AM radio

- 620 WJDX: Fox Sports Radio

- 780 WIIN: Christian country-music

- 810 WSJC: Family Talk radio

- 850 WQST: southern gospel

- 930 WSFZ: Sporting News Radio

- 970 WJFN: Sporting News Radio

- 1120 WTWZ: bluegrass gospel

- 1150 WONG: gospel

- 1180 WJNT: news-talk

- 1240 WPBQ: ESPN Radio

- 1300 WOAD: gospel

- 1370 WMGO: gospel

- 1400 WJQS: business

- 1590 WZRX: CNN Headline News

Points of interest

Tourism and Culture

Jackson is a city famous for its music - including Gospel, Blues, and R&B. Jackson is also home to the world famous Malaco Records recording studio. Many notable musicians hail from Jackson.

Rap rocker Kid Rock made a song about Jackson, aptly titled "Jackson, Mississippi", in 2003.

"Jackson" is a song written by Jerry Leiber and Billy Edd Wheeler about a married couple who find that the "fire" has gone out of their relationship. The song relates the desire of the husband and wife to travel to Jackson, Mississippi, where they each look forward to a new life free of the unhappy relationship. Famous covers of the song include the 1968 Grammy Award winner by Johnny Cash and June Carter Cash. The song was performed by Joaquin Phoenix and Reese Witherspoon (playing Johnny Cash and June Carter) in the 2005 film Walk the Line.

In 1978, the USA International Ballet Competition was founded in Jackson by Thalia Mara, who is also the namesake of Thalia Mara Hall where the competition is held. The following year saw the first USA International Ballet Competition held as part of the worldwide International Ballet Competition (IBC), which itself originated in Varna, Bulgaria in 1964. The competition eventually expanded to rotating annual events between Jackson, Varna, Moscow and Tokyo. It was in 1979 that the event first came to the United States, to Jackson, where it now returns every four years. The rotation is currently among Jackson, Varna, Helsinki, Finland, and Shanghai, China. Jackson has been the host of the IBC in 1979, 1982, 1986, 1990, 1994, 1998, 2002 and 2006. The next competition in Jackson will be in 2010. The United States Congress recognized Jackson and the USA IBC by passing a Joint Resolution in 1982 that designated Jackson as the official home of the USA IBC.[31]

Periodic cultural events

- CelticFest Mississippi (annual, September)

- Crossroads Film Festival (annual, April)

- Festival Latino (annual, September)

- Jubilee!Jam (annual, June)

- Mal's St. Pattys Day Parade (annual, on the Saturday of or after March 17, the fourth largest in the nation with over 50,000 people)

- Mississippi State Fair (annual, held in October)

- OUToberfest (annual gay and lesbian festival, October)

- USA International Ballet Competition (every four years, June)

Downtown Jackson Attractions

|

|

|

Museums and Historic Sites

Historic marker

Jackson, Mississippi received its first Mississippi Blues Trail designation. The ceremony was held and the historic marker placed on the former site of the Subway Lounge on Pearl Street. The Subway Lounge was in the basement of the old Summers Hotel, one of two hotels available as lodging to blacks before desegregation when it opened in 1943. In the 1960s, the hotel added a lounge in the basement that featured jazz. In the 1980s, when the lounge was revived, it was catered to late night blues performers. In 2002, the Subway Lounge was filmed for a documentary entitled Last of the Mississippi Jukes.[32][33]

Parks

- Battlefield Park

- Grove Park

- LeFleur's Bluff State Park

- Parham Bridges Park

- Sheppard Brothers Park

- Smith Park

- Sykes Park

Downtown Jackson Renaissance

Currently, Jackson is experiencing $1.6 billion in downtown development[34]. Among the projects include improvements to or construction of the following:

|

|

|

|

|

Tallest buildings

| Name | Height | Year |

|---|---|---|

| Regions Plaza (formerly AmSouth) | 97 m | 1975 |

| Jackson Marriott Downtown | 78 m | 1975 |

| Regions Bank Building (formerly AmSouth) | 77 m | 1929 |

| Standard Life Building | 76 m | 1929 |

| Trustmark National Bank Building | 66 m | 1955 |

| Lamar Life Building | 58 m | 1924 |

Sports

Summer Training Camp

- New Orleans Saints - Jackson's Millsaps College is the former summer home for the NFL's New Orleans Saints.

Sports arenas

- Mississippi Veterans Memorial Stadium -- Concerts, Football (home of Jackson State University)

- Mississippi Coliseum -- Basketball, Hockey, Track, Rodeo, Concerts

- Smith Wills Stadium -- Baseball, Softball, Football, Soccer, Concerts

Former professional sports teams

- Baseball

- Jackson Mets - former Texas League AA affiliate of the New York Mets (1975-1990); Smith-Wills Stadium

- Jackson Generals - former Texas League AA affiliate of the Houston Astros (1991-1999); Smith-Wills Stadium

- Jackson Diamond Kats - of the independent Texas-Louisiana League (later changed its name to the Central Baseball League) (2000); Smith-Wills Stadium

- Jackson Senators - Independent (2001-2004); Smith-Wills Stadium

- Hockey

- Jackson Bandits - East Coast Hockey League, 1999–2003

- Soccer

- Jackson Calypso - Women's Soccer

- Jackson Rockers - Men's Soccer

- Jackson Chargers - Men's Soccer

Noteworthy natives

Jackson is the birthplace of many notable people. From writers Eudora Welty and Willie Morris and civil rights leaders Medgar Evers and James Meredith to rapper David Banner, jazz legend Cassandra Wilson, blues pianist Otis Spann and sports stars Fred Smoot, Jim Gallagher, Jr. and Monta Ellis. Actors, artists, authors, cooks, inventors, musicians, painters, sports figures and more, Jackson has contributed significantly to America's culture.

(see: List of people from Mississippi for a more in-depth list)

References

- ^ New Jackson police chief outlining goals

- ^ "Annual Estimates of the Population for Incorporated Places in Mississippi: April 1, 2000 to July 1, 2006" (CSV). 2006 Population Estimates. United States Census Bureau, Population Division. 2007-06-28. Retrieved 2007-09-30.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Table 1. Annual Estimates of the Population for Counties of Mississippi: April 1, 2000 to July 1, 2006" (CSV). 2006 Population Estimates. United States Census Bureau, Population Division. 2007-03-22. Retrieved 2007-09-30.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Annual Estimates of the Population of Combined Statistical Areas: April 1, 2000 to July 1, 2006" (Microsoft Excel). United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2007-09-30.

- ^ http://www.jacksoncitywithsoul.com/

- ^ "History of Meridian, MS". Official website of Meridian, MeridianMS.org. Retrieved 2008-06-07.

- ^ Bob Ferguson (2004). "Choctaw Treaties - Dancing Rabbit Creek". Choctaw Museum of the Southern Indian. Retrieved 2008-06-07.

- ^ WorldWeb.com Travel Guide

- ^ Official City of Jackson, Mississippi Website - Jackson's History

- ^ George C. Rable, But There Was No Peace: The Role of Violence in the Politics of Reconstruction, Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1984, p. 132

- ^ Richard H. Pildes, "Democracy, Anti-Democracy, and the Canon", Constitutional Commentary, Vol.17, 2000, pp.12-13, accessed 10 March 2008

- ^ Michael Perman, Struggle for Mastery: Disfranchisement in the South, 1888-1908, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001

- ^ Civil Rights Movement Veterans. "Freedom Rides".

- ^ Civil Rights Movement Veterans. "Tougaloo 9".

- ^ Civil Rights Movement Veterans. "Jackson MS, Boycotts".

- ^ Civil Rights Movement Veterans. "Jackson Sit-in & Protests".

- ^ Medgar Evers Assassination ~ Civil Rights Movement Veterans

- ^ History of Beth Israel, Jackson, Mississippi, Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life website, History Department, Digital Archive, Mississippi, Jackson, Beth Israel. Accessed August 17, 2008.

- ^ Edward Blum and Abigail Thernstrom, Executive Summary of the Bullock-Gaddie Expert Report on Mississippi, 17 Apr 2006, accessed 21 March 2008

- ^ Tim Spofford, Lynch Street: The May 1970 Slayings at Jackson State College, Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1988, pp. 17 and 19

- ^ http://www.visitjackson.com/media-article.php?article_id=52

- ^ Associated Press (July 27 2006). "Mayor of U.S. city failing the hard test of crime prevention" (in English). Taipei Times. Retrieved 2007-03-09.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ USA Today (November 16 2007). "Mayor appoints sheriff who arrested him -- twice -- as police chief" (in English). USA Today. Retrieved 2007-11-19.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Mississippi, University of (2003-12-12). "The Geology of Mississippi" (PDF). University of Mississippi. Retrieved 2007-09-27.

- ^ 2000 Census Data on Same-sex couple households

- ^ Profile of General Demographic Characteristics: 2000, United States Census Bureau

- ^

"Jackson ranked 23rd most dangerous city in group's crime analysis". The Clarion-Ledger. November 19 2007. Retrieved 2007-11-19.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Baydala, Kathleen (March 21 2009). "JPD staffing, pay cited". The Clarion-Ledger. Retrieved 2009-03-21.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c The Clarion-Ledger:Jackson murder rate 4th in nation

- ^ History of Beth Israel, Jackson, Mississippi, Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life website, History Department, Digital Archive, Mississippi, Jackson, Beth Israel. Accessed November 17, 2008.

- ^ USA International Ballet Competition

- ^ "Jackson To Honor Fallen Juke Joint with Mississippi Blues Trail Marker" (PDF). Mississippi Development Authority. Retrieved 2008-06-01.

- ^ "Last of the Mississippi Jukes - Photo Album". www.robertmugge.com. Retrieved 2008-06-01.

- ^ Downtown Jackson Partners

External links

- Settlements established in 1792

- Cities in Mississippi

- Hinds County, Mississippi

- Madison County, Mississippi

- Rankin County, Mississippi

- Jackson, Mississippi

- Planned cities

- United States communities with African American majority populations

- County seats in Mississippi

- Jackson metropolitan area

- Mississippi Blues Trail