Kenilworth, Illinois

Kenilworth, Illinois | |

|---|---|

Village | |

| Village of Kenilworth, Illinois | |

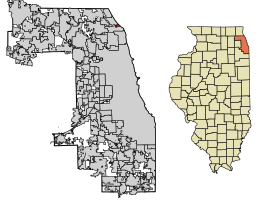

Location of Kenilworth in Cook County, Illinois. | |

Location of Illinois in the United States | |

| Coordinates: 42°5′17″N 87°42′57″W / 42.08806°N 87.71583°W | |

| Country | |

| State | Illinois |

| County | Cook |

| Township | New Trier |

| Incorporated | 1889 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council–manager |

| • President | Bill Russell |

| Area | |

| • Total | 0.61 sq mi (1.57 km2) |

| • Land | 0.61 sq mi (1.57 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.00 km2) 0% |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 2,513 |

| • Estimate (2019)[2] | 2,475 |

| • Density | 4,077.43/sq mi (1,573.15/km2) |

| Up 0.8% from 2000 | |

| Standard of living (2007-11) | |

| • Per capita income | $104,301 |

| • Median home value | $1,000,000+ |

| ZIP code(s) | 60043 |

| Area code(s) | 847 & 224 |

| Geocode | 39519 |

| FIPS code | 17-39519 |

| Website | www |

Kenilworth is a village in Cook County, Illinois, United States, 15 miles (24 km) north of downtown Chicago. As of the 2010 census it had a population of 2,513.[3] It is the newest of the nine suburban North Shore communities bordering Lake Michigan, and is one of those developed as a planned community. In 2018, Kenilworth was the eighth wealthiest community in the United States, and the wealthiest in the Midwestern United States.[4]

History

Kenilworth was founded in 1889 when Joseph Sears purchased 223.6 acres of land consisting of several farms between the Chicago and North Western Railroad and Lake Michigan for $150,300. Sears and several of his associates formed The Kenilworth Company to execute his suburban dream.[5]

Joseph Sears founded Kenilworth with four key provisos: "Large lots, high standards of construction, no alleys, and sales to Caucasians only." "Caucasians only" was interpreted to exclude Jews as well as nonwhites.

Later, Sears realized he had forgotten to allow for live-in servants and sent a note to each resident of Kenilworth; none objected. By 1950 the suburb had 79 African Americans — every one a maid, nanny, or other servant.

The company undertook all marketing activities. They publicized the community's many attractive features through brochures, maps, and newspaper ads, as well as direct personal sales. Prospects were provided transportation from the city and greeted with a reception. Visitors were also offered overnight accommodations. In 1891, Sears invited about 20 of his personal friends, prominent bankers and Chicago businessmen to a picnic luncheon on Kenilworth's lake shore. Lots were offered at $60 an acre; significantly above the $15 an acre for similarly located property nearby. Some laughed, but the property did sell within 12 months.[6] This planned community attracted widespread attention and was visited by many noted architects attending the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

On February 4, 1896, the village reached the required 300 residents and was incorporated. The elected board assumed municipal functions from Sears. The Kenilworth Company continued their sales activities until 1904, at which time Sears acquired the existing stock and became the sole owner of the remaining property.[7]

The Kenilworth Company coordinated every aspect of this planned community to ensure the highest quality implementation and adherence to Joseph Sears’ vision. The village layout was designed to take advantage of the natural features and beauty of the land. To maintain the country atmosphere, the plan required large lots and setbacks, tree plantings along roadways, and generous park lands. Mr. Sears donated much of his own property to achieve this goal.[8]

The church, schools, parks, clubs, and recreational areas were early additions to encourage a spirit of community. Noted architect Franklin Burnham joined The Kenilworth Company and designed the railroad station and the Kenilworth Union Church. Burnham also designed several homes for company members to display for potential residents.[9]

Colleen Kilner, in her book Joseph Sears and his Kenilworth, stated that lots were sold to Caucasians only.[10] However, she does not provide evidence for this claim or document its origins. While the original ordinances for the Village specify strict building regulations, they do not include the restriction of sales based on race or religion.[11] The village population on reached 2,501 in 1930 and has stayed nearly the same since then. In 1949, the US Supreme Court ruled, in Shelley v. Kraemer, that restrictive covenants were unenforceable. In addition, the Civil Rights Act of 1968 outlawed such racial and religious covenants, but many, though unenforceable, are still found in housing deeds in the 21st century.

The first African-American family to move to Kenilworth, the Calhouns, was met with resistance from some in the community, such as a cross burning in 1966 and racially charged vandalism, while others voiced shock over the offenses.[12] However, most residents expressed their support for the family. Walter Calhoun, a young student and athlete at the time, recalls "They bent over backwards to make sure I was never left out."[13] Four years after the shocking incident, two teenagers visited Harold Calhoun in his downtown office where they confessed and apologized for the cross burning.[13]

Geography

According to the 2010 census, Kenilworth has a total area of 0.61 square miles (1.58 km2), all land.[14]

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1900 | 336 | — | |

| 1910 | 881 | 162.2% | |

| 1920 | 1,188 | 34.8% | |

| 1930 | 2,501 | 110.5% | |

| 1940 | 2,935 | 17.4% | |

| 1950 | 2,789 | −5.0% | |

| 1960 | 2,959 | 6.1% | |

| 1970 | 2,980 | 0.7% | |

| 1980 | 2,708 | −9.1% | |

| 1990 | 2,402 | −11.3% | |

| 2000 | 2,494 | 3.8% | |

| 2010 | 2,513 | 0.8% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 2,475 | [2] | −1.5% |

| US Census Bureau | |||

As of the census[15] of 2010, there were 2,513 people, 800 households and 699 families residing in the village. The population density was 4,188.3 people per square mile (1,570.6/km2). There were 855 housing units at an average density of 1,425.0 per square mile (534.4/km2). The racial makeup of the village was 97.4% White, 0.3% African American, 0.1% Native American, 1.3% Asian, and 0.9% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.6% of the population.[3]

There were 800 households, out of which 47.6% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 79.3% were headed by married couples living together, 5.9% had a female householder with no husband present, and 12.6% were non-families. 11.1% of all households were made up of individuals, and 6.7% were someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.14, and the average family size was 3.41.[3]

In the village, the population was spread out, with 34.3% under the age of 18, 4.9% from 18 to 24, 14.6% from 25 to 44, 32.6% from 45 to 64, and 13.4% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 42.4 years. For every 100 females, there were 95.3 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 91.2 males.[3]

For the period 2007–11, the estimated median annual income for a household in the village was $242,188, and the median income for a family was over $250,000. The per capita income for the village was $104,301. 1.2% of families and 1.9% of the population were below the poverty line, including 1.8% of those under age 18 and 3.5% of those age 65 or over.[16]

Arts and culture

Notable places and organizations in Kenilworth include:

- Kenilworth Fountain – In the middle of Kenilworth Avenue just east of the railroad tracks

- The Kenilworth Beach – The public beach on Lake Michigan, which is divided into a sailing beach and a bathing beach

- Pee Wee Field – Also known as "Sears Stadium" - Baseball field located on the west side of town where many little leaguers play

- Townley Field – District-owned sports field behind the school where many sports are played including field hockey, soccer, lacrosse, football, and the school Field Day

- The Ware Garden – Public courtyard on the east side where many residents walk their dogs

- Mahoney Park – A small park on the south side of town, named after the farm that was there at the town's founding

- Kenilworth Train Station – Train station on the Metra Line in between Indian Hill and Wilmette stations

- Joseph Sears School – Public elementary and junior high school on Abbotsford Road (JK-8)

- The Kenilworth Club – A frequented community house that hosts all sorts of events throughout the year

- Kenilworth Historical Society – Preserve and present the history of the town

- Kenilworth Union Church – A non-denominational Protestant church on Kenilworth Avenue

- Church of the Holy Comforter – Episcopal Church across the street from Kenilworth Union

- Hiram Baldwin House – A Prairie School house designed by Frank Lloyd Wright in 1905

Kenilworth does not have its own fire department or library; for these services, the town contracts with the neighboring Winnetka fire department and with the Wilmette library. Kenilworth has its own police department and 9-1-1 calls are handled by Glenview Public Safety Dispatch.

Kenilworth Assembly Hall

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2007) |

Known as the Kenilworth Club, the Assembly Hall is a community building in the center of the village used for civic events for the town's gatherings, school-related events, and private organizations' meetings. This building is used for the annual Joseph Sears School benefits as well. The building was constructed by George Maher in 1907. The community house is used by the Historical Society, Joseph Sears School, and the Boy and Girl Scouts programs among others. In addition, a handful of yearly events go on at the Kenilworth Club, including Bingo Night, The Memorial Day Parade (which is not on memorial day because most of the residents leave for memorial day weekend), and the Halloween Party. According to the official website, the Club's mission is, "To educate members of the community about the village, its history and architecture, as represented by the Assembly Hall itself; to promote friendly relations among its members; to serve their social needs; and to promote cultural activities, provide literary entertainment and encourage mental culture."

In recent years, the Kenilworth Assembly Hall has become a home for concerts and benefits hosted by local bands from New Trier High School, Sears moms and other surrounding areas. The title "North Shore Scene" has been appropriately coined by many students and teenagers to describe their association with the concerts and the bands that participate. The North Shore Scene has helped launch the careers of well-known artists such as Fall Out Boy.

Government

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third Parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 39.61% 604 | 51.74% 789 | 8.65% 132 |

| 2012 | 66.55 1,108 | 32.85% 547 | 0.60% 10 |

| 2008 | 55.27% 950 | 43.86% 754 | 0.87% 15 |

| 2004 | 65.51%% 904 | 34.13% 471 | 0.36% 5 |

| 2000 | 70.33% 813 | 27.68% 320 | 1.99% 23 |

Education

Kenilworth has its own public school district, with its only school being Joseph Sears School, named after the founder of the village. The district is School District 38 in Cook County, and is the fifth most expensive K-8 district in the state of Illinois in per-student spending. The school, commonly known as Sears, runs from junior kindergarten through eighth grade, with about sixty students per grade. Sears has its own gymnasium, auditorium, library, and one high-tech computer lab, in addition to a blacktop and large fields behind the school. Annual events that go on at Sears include The Eighth Grade Play, the Spelling Bee, the Geography Bee, Scamper Night (concert put-on by the Girl Scouts), and Field Day (Tigers vs. Wildcats). Most students participate in one of the school's athletic teams, including boys and girls basketball, boys and girls volleyball, coed soccer, field hockey and coed track and field. Football and Lacrosse are also popular sports students will participate in that are run through the Kenilworth Park District.

There are no private schools in the small village of Kenilworth itself, but some K-8 students do attend nearby schools such as St. Faith, Hope and Charity, St. Joseph, St. Francis Xavier, Roycemore School, Baker Demonstration, and North Shore Country Day.

The vast majority of high school students in Kenilworth attend New Trier High School, the district high school just down the road, but others attend a variety of private schools including local and boarding schools. The most popular choices for students looking for alternatives include local private schools such as Loyola Academy, North Shore Country Day School, Regina Dominican, Roycemore School, and Lake Forest Academy.

Notable people

- Frances Badger, painter and muralist, born in Kenilworth[18]

- Debra Cafaro, Chairman of the Board and Chief Executive Officer of Ventas, an S&P 500 company; a minority owner of the Pittsburgh Penguins[19]

- Julia Collins, 20-game Jeopardy! champion [20]

- Robert Dold, Former Republican United States Congressman from 10th District of Illinois[21]

- Walker Evans, Depression era photographer[22]

- Paul Harvey, radio news commentator.

- Christopher George Kennedy, son of Robert F. Kennedy and Ethel Kennedy, and former president of the Merchandise Mart[23]

- Mark Kirk, Republican former United States Senator from Illinois[24]

- George Washington Maher, historically significant Chicago area architect[25]

- James McManus, poker player[26]

- Charles H. Percy, late and former Republican United States Senator from Illinois[27]

- Jude Reyes, billionaire, co-owner of Rosemont-based Reyes Holdings, Inc.[28]

- Liesel Pritzker Simmons, actress, millionaire, and philanthropist[29]

- Bradley Roland Will, activist, videographer and journalist; born in Evanston, was raised in Kenilworth

- Terence H. Winkless, film director[30]

References

- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- ^ a b "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (DP-1): Kenilworth village, Illinois". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved March 13, 2013.

- ^ "Where the Rich Are in the Midwest: 50 Richest Zip Codes". Bloomberg. Retrieved 2019-04-03.

- ^ Kilner, Colleen (1969). Joseph Sears and his Kenilworth. Kenilworth, IL: Kenilworth Historical Society. p. 138.

- ^ Kenilworth - First Fifty Years. Kenilworth, IL: Village of Kenilworth. 1947. p. 8.

- ^ Kenilworth - First Fifty Years. Kenilworth, IL: Village of Kenilworth. 1947. p. 2.

- ^ Kenilworth - First Fifty Years. Kenilworth, IL: Village of Kenilworth. 1947. pp. 25, 33, 39.

- ^ Kilner, Colleen (1969). Joseph Sears and His Kenilworth. Kenilworth, IL: Kenilworth Historical Society. pp. 153–54.

- ^ Kilner, Colleen (1990). Joseph Sears and his Kenilworth. Kenilworth Historical Society. p. 143.

- ^ Nonetheless, many credible books from the time of Kenilworth's founding ""History of Small Town Kenilworth". include communities around the Chicago area that were restricted by housing covenants that prevented non-whites (and many Jews) from living in the town limits. Village of Kenilworth Ordinances and Regulations. Kenilworth, IL: Village of Kenilworth. 1896. pp. 6–8.

- ^ "Residents voice shock over cross burning here". Wilmette News. May 26, 1966.

- ^ a b Marihugh, Holly (December 8, 2014). "Friendship & Forgiveness in Kenilworth". Daily North Shore. Retrieved January 5, 2017.

- ^ "G001 - Geographic Identifiers - 2010 Census Summary File 1". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2020-02-13. Retrieved 2015-08-04.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ^ "Selected Economic Characteristics: 2007–2011 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates (DP03): Kenilworth village, Illinois". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved March 13, 2013.

- ^ https://www.cookcountyclerk.com/election-results.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Schulman, Daniel. "Frances Badger". chicagomodern.org. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- ^ "$5.25M Kenilworth Home Designed by George Maher". Wilmette-Kenilworth, IL Patch. 2013-02-11. Retrieved 2018-06-14.

- ^ "Will The Streak Get Cracked?". thejeopardyfan.com (Blog). April 29, 2014.[unreliable source?]

- ^ Zawislak, Mick (September 12, 2009). "Kenilworth businessman to enter 10th Dist. Congressional race". Daily Herald.

- ^ "Oral history interview with Walker Evans, 1971 Oct. 13-Dec. 23". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. 1971.

- ^ "FEC Disclosure Image 28020220523". Federal Election Commission. March 3, 2008. Retrieved October 20, 2014.

- ^ Sweet, Lynn (July 23, 2010). "Mark Kirk and his near drowning story". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on February 9, 2013.

- ^ "George Washington Maher". Pleasant Home Foundation. Archived from the original on December 20, 2016. Retrieved October 20, 2014.

- ^ "From 'Bad Jim' in Las Vegas to 'geezer dad' in Kenilworth". Chicago Tribune. May 4, 2003.

- ^ "Newly disclosed account surfaces in 1966 Valerie Percy murder case". Chicago Tribune. June 14, 2011.

- ^ "Jude Reyes". Forbes.

- ^ Carlyle, Erin (November 17, 2013). "Liesel Pritzker Simmons Sued Her Family And Got $500 Million, But She's No Trust Fund Baby". Forbes.

- ^ "Terence H. Winkless". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved October 20, 2014.