Morton Grove, Illinois

Morton Grove, Illinois | |

|---|---|

Morton Grove Civic Center | |

| Nickname: The Grove | |

| Motto: "First in service.." | |

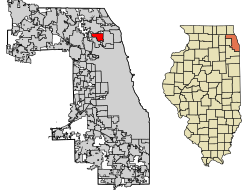

Location of Morton Grove in Cook County, Illinois. | |

| Coordinates: 42°2′26″N 87°46′57″W / 42.04056°N 87.78250°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Illinois |

| County | Cook |

| Township | Maine, Niles |

| Founded | 1895 |

| Area | |

• Total | 5.09 sq mi (13.18 km2) |

| • Land | 5.09 sq mi (13.18 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.00 km2) |

| Elevation | 623 ft (190 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 25,297 |

| • Density | 4,971.89/sq mi (1,919.60/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP Code(s) | 60053, 60054, 60055 |

| Area code | 847 |

| FIPS code | 17-50647 |

| GNIS feature ID | 413865[2] |

| Website | www |

Morton Grove is a village in Cook County, Illinois, United States. Per the 2020 census, the population was 25,297.[3] It is part of the Chicago metropolitan area.

The village is named after former United States Vice President Levi Parsons Morton, who helped finance the Chicago, Milwaukee and St. Paul Railroad (later the Milwaukee Road), which roughly tracked the North Branch of the Chicago River in the area and established a stop at the old Miller's Mill. Miller's Mill Road, now Lincoln Avenue, connected the former riverside sawmill to the township's central settlement (Niles Center, now Skokie). The railroad stop facilitated trade and development; the upstart neighborhood grew enough to incorporate in December 1895.

History

[edit]A handful of farmers from England settled in 1830-1832, despite there being no roads from Chicago, only Native American trails, as the defeat of the Black Hawk War and the 1833 Treaty of Chicago led Native Americans to leave the areas. Farmers from Germany and Luxembourg started arriving by the end of the decade, clearing the land by cutting the walnut, oak, hickory, elm and maple trees. Logs were initially hauled to a sawmill at Dutchman's Point (later Niles, Illinois) at the corner of what became Milwaukee, Waukegan and Touhy Avenues, and stumps burned for charcoal that could then be hauled to heat homes in expanding Chicago. Immigrant John Miller erected a water-powered sawmill near where the Chicago River met the future Dempster Street shortly after 1841.[4] This simplified homebuilding in the area, as well as facilitated further lumber sales. A road (first known as Miller's Mill Road and after 1915 as Lincoln Avenue) allowed wood from the sawmill (and produce from nearby farms) to be hauled to the largest settlement in the surrounding Niles Township (initially known as Niles Center and now Skokie) or even further, into Chicago.[5] Around 1850, the "Northwestern" road to/from Chicago (now known as Milwaukee Avenue) was improved (partly using lumber from Miller's sawmill) to become a single lane plank (toll) road. That reduced a four-day journey into Chicago to about a half day, and also helped sales of produce and farm products from the rich bottomland. Lumber was also hauled to Jefferson Park to fuel locomotives after the first railroads were built in the area. In 1858, Henry Harms[6] built a toll road from the intersection of Ashland and Lincoln Avenues in Chicago to Skokie, where it met Miller's Mill Road. Harms' Road was later extended through Glenview.

In 1872, the Chicago, Milwaukee and St. Paul Railroad bought Miller's Mill and laid track (which became two lines in 1892). They also dug gravel for railroad and road use nearby, creating a quarry at what later became Austin Park. The stop (later station) at what had been Miller's Mill was named Morton Grove to honor one of the railroad's New York financiers, Levi Parsons Morton. The Morton Grove settlement began growing from about 100 persons, and by 1874 had grown enough to have its first postmaster, Civil War veteran Medard Lochner. Rural mail service started 21 years later, although a blacksmith shop was opened at the settlement by 1884, and a trading post and saloon had operated since 1847.[7] The first subdivision (177 lots) was platted by real estate developers George Fernald and Fred Bingham in 1891, and a convalescent home for German-American aged was built in 1894.[8] The village formally incorporated on December 24, 1895, just eight days before Morton became the Governor of New York. Morton Grove's first mayor, George Harrer, was of German descent (and became the namesake of the village's largest park), and his brother became Skokie's mayor.

20th century growth

[edit]The first greenhouses were built in Morton Grove in 1885 (the railroad transported 135,000 tons of coal annually to heat them in cold weather), and the Poehlman Brothers' floral business grew into one of the world’s largest floral firms, receiving international recognition when one of its roses won first place at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair. The orchid department alone included eight greenhouses, and the nearby railroad station received flowers from the Philippines and South America to service customers with more exotic tastes. By 1915 the Poehlman Brothers' payroll included 400 to 500 people. However, the business went bankrupt in the Great Depression. Baxter Laboratories bought much of the former Poehlman land, and became a major employer in the following decades. The 20 acres (8 hectares) of land surrounding Greenhouse C was purchased by the Morton Grove Days Committee and ultimately became Harrer Park. Lochner's and the wholesale firm Platz Flowers (retail business name "Jamaican Gardens") continue to operate in the village.[9] August Poehlman long served as one of Morton Grove's six trustees (and as its second mayor), and his brother Adolph was the village attorney.[10]

The Poehlmans also helped found Jerusalem Evangelical Lutheran Church and its school in 1897.[11]

In 1897, close to the turn of the 20th century, Morton Grove built a public school. A one-room "little red schoolhouse" had existed at Waukegan in Beckwith roads from 1860 until finally torn down in 1990, and the Jerusalem Lutheran pastor also operated a school.[12] The city gained a telephone exchange in 1900, and then established a volunteer fire department in 1904. That year, considerable land in the village became forest preserve property, including the banks of the North Branch of the Chicago River (now part of the Ralph Frese Trail) and a section known as the Skokie marshes.[9]

In 1907, gas lines were installed. In 1911, North Shore Electric Light Company installed 36 street lights and the village installed a cement sidewalk along Miller's Road. The next year, water and sewer lines were completed, and the first sewerage treatment plant began operations in 1914, leading to the new Metropolitan Sanitary District Treatment Plant at Oakton Street and McCormick Road in Skokie. Morton Grove then outlawed outhouses in 1920. Meanwhile, pickle and sauerkraut plants also operated in the village from 1900 until 1915, when a pickle blight caused them to close. Morton Grove's first bank was constructed in 1912 and a theater began showing silent movies beginning in 1916.[13]

Morton Grove continued to grow and prosper as it welcomed home those who fought in World War I, and new immigrants. Village population exceeded 1000 in the 1920 census. St. Martha Catholic Church was founded in 1919 as parishioners rented what had been a tavern before Prohibition, then erected their own church in 1923. Catholics had previously traveled to St. Peter's Church in Niles Center or St. Joseph's Church in Grosse Point, which became Wilmette.[14]

From 1919 to 1932, some farmland was transformed into a small airfield north of Dempster St., and tourist flights and wing-walking continued. One of the owners, Fred Sonne, helped form the Chicago Aerial Survey Company (and was honored for his aerial photography in World War II). Hermine Sonne, who married his partner, Dick Boettcher, became the first woman in the village to fly.[15]

As the "Jazz Age" roared on, Morton Grove also became known for its night clubs and speakeasies, especially the Dells club (originally the Huscher family residence at Austin and Dempster streets, which burned down in 1934), the Lincoln Tavern (now the American Legion hall, it burned down in 1918 and was rebuilt across the street, and became a gambling casino in the 1930s with over 400 slot machines, plus dice tables, roulette, blackjack, etc.), the Light House (later called the Coconut Grove) and the Bit and Bridle, among others. The clubs offered live music and entertainment, dancing, fine food, and ambiance (and discreetly served liquor during Prohibition). Since Evanston to the east was dry (and headquarters of the Women's Christian Temperance Union) and Skokie in between often hosted temperance lectures, Morton Grove's speakeasies drew visitors in limousines and cars from across the North Shore. The Morton Grove Chamber of Commerce & Industry was founded in 1926; the village's resident population reached 1,980 in 1930.[16]

The Great Depression struck the village, then World War II forced it to meet further challenges. Morton Grove gained a Bell & Gossett plant in 1941, which as part of W.W. Grainger Industrial Supply remained a major employer for decades.[citation needed]

After World War II, a new era of growth and prosperity began as Morton Grove entered the “Baby Boom” era. The population of Morton Grove grew from 2,010 in 1940 to 3,926 by 1950, then soared to 20,533 in 1960. People seeking a better life ventured into the suburbs from Chicago and found Morton Grove, especially after the Edens Expressway opened and cut commuting time into Chicago. In addition to building new schools, Morton Grove gained a Community Church (affiliated with the Presbyterian denomination; chartered in 1951), as well as St. Luke's United Church of Christ (in 1956), the Northwest Suburban Jewish Congregation (in 1957) and Jehovah's Witnesses temple (in 1962).[17] Also, one current resident now maintains a repository for memorials from defunct synagogues in northwest Chicago and surrounding communities.[18] However, the railroad station was downsized in 1974, as freight traffic had declined and it was mostly used for commuters into Chicago.[citation needed]

The community's demographic mix continued to change from its predominantly Germanic founding. Morton Grove gained many Filipino immigrants, as well as many from Syria, India and Pakistan, so that by 2010 it had among the largest Asian communities on the North Shore.[19] The northwest Chicago Muslim Community Center (founded in 1969) established a branch in Morton Grove and a school in Skokie.[20] In 2000, Morton Grove had 22,451 residents (74 percent white, 22 percent Asian, 4 percent Hispanic and 0.6 percent black).[9] The village's population reached 23,270 by the 2010 Census (66 percent white, 28 percent Asian, 4.4 percent Hispanic, 1.2 percent black and 2.7 percent identified themselves as belonging to two or more races).[citation needed]

Handgun ban

[edit]In 1981, Morton Grove became the first town in America to prohibit the possession of handguns. Victor Quilici, a local lawyer, sued the city (Quilici v. Morton Grove). The federal district court as well as the Appellate Court ruled the Morton Grove ordinance to be constitutional, thus upholding the gun ban. The U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear the case, letting the lower court decision stand. The ban stood as village code 6-2-3.[21] However, in light of the U.S. Supreme Court's 2008 opinion in District of Columbia v. Heller,[22] it appeared likely that the village would drop the ban. On July 28, 2008, the city dropped its prohibition on handguns. The village board voted 5–1 in favor of removing the ban.[23]

Geography

[edit]According to the 2021 census gazetteer files, Morton Grove has a total area of 5.09 square miles (13.18 km2), all land.[24] The North Branch of the Chicago River runs through the middle of the suburb; land along both banks is within Cook County Forest Preserve.

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1900 | 564 | — | |

| 1910 | 836 | 48.2% | |

| 1920 | 1,079 | 29.1% | |

| 1930 | 1,974 | 82.9% | |

| 1940 | 2,010 | 1.8% | |

| 1950 | 3,926 | 95.3% | |

| 1960 | 20,533 | 423.0% | |

| 1970 | 26,369 | 28.4% | |

| 1980 | 23,747 | −9.9% | |

| 1990 | 22,408 | −5.6% | |

| 2000 | 22,451 | 0.2% | |

| 2010 | 23,270 | 3.6% | |

| 2020 | 25,297 | 8.7% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[25] 2010[26] 2020[27] | |||

As of the 2020 census[28] there were 25,297 people, 8,786 households, and 6,338 families residing in the village. The population density was 4,971.89 inhabitants per square mile (1,919.66/km2). There were 9,278 housing units at an average density of 1,823.51 per square mile (704.06/km2). The racial makeup of the village was 54.24% White, 33.98% Asian, 1.94% African American, 0.38% Native American, 0.01% Pacific Islander, 3.08% from other races, and 6.38% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 8.07% of the population.

There were 8,786 households, out of which 28.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 60.90% were married couples living together, 7.65% had a female householder with no husband present, and 27.86% were non-families. 25.88% of all households were made up of individuals, and 16.56% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.15 and the average family size was 2.59.

The village's age distribution consisted of 19.4% under the age of 18, 5.2% from 18 to 24, 21.8% from 25 to 44, 27.2% from 45 to 64, and 26.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 47.2 years. For every 100 females, there were 97.2 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 93.0 males.

The median income for a household in the village was $87,063, and the median income for a family was $110,549. Males had a median income of $61,258 versus $44,069 for females. The per capita income for the village was $40,923. About 6.3% of families and 7.0% of the population were below the poverty line, including 10.0% of those under age 18 and 8.3% of those age 65 or over.

| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 2000[29] | Pop 2010[26] | Pop 2020[27] | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 15,938 | 14,426 | 13,359 | 70.99% | 61.99% | 52.81% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 135 | 279 | 474 | 0.60% | 1.20% | 1.87% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 13 | 32 | 34 | 0.06% | 0.14% | 0.13% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 4,958 | 6,498 | 8,540 | 22.08% | 27.92% | 33.76% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 1 | 9 | 2 | 0.00% | 0.04% | 0.01% |

| Other race alone (NH) | 40 | 24 | 71 | 0.08% | 0.10% | 0.28% |

| Mixed race or Multiracial (NH) | 378 | 498 | 776 | 1.68% | 2.14% | 3.07% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 988 | 1,504 | 2,041 | 4.40% | 6.46% | 8.07% |

| Total | 22,451 | 23,270 | 25,297 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

Economy

[edit]The headquarters for Alpha Delta Phi fraternity is located in Morton.[30]

Principal employers

[edit]According to Morton Grove's 2022 Annual Comprehensive Financial Report,[31] the principal employers in the village are:

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Xylem | 475 |

| 2 | John Crane | 460 |

| 3 | Advanced Skin and Mohs Clinic | 410 |

| 4 | Amazon Fresh | 300 |

| 4 | Fareva | 300 |

| 6 | Lakeshore Recycling | 225 |

| 7 | Schwartz Paper Co | 200 |

| 7 | Quantum Color Graphics | 200 |

| 9 | MG Phamaceutical | 176 |

| 10 | Illinois Bone & Joint | 175 |

Government

[edit]The Village of Morton Grove is represented by a governing board consisting of a Village President and six Village Trustee. The President and Trustee are elected to four-year terms. The Village President is the presiding officer of Village Board meetings, as well as the Village's chief executive officer. The Village President of Morton Grove since May 13, 2013, is Mayor Daniel P. DiMaria.

Regularly scheduled Board meetings are held on the second and fourth Mondays of each month, beginning with a closed door executive session at 6:00 PM.[32] The Village Board is the governing body of the Village and exercises all powers entrusted to it under Illinois statutes. These include police powers related to the community's health, safety, and welfare.

Education

[edit]Public school districts serving Morton Grove include:[33]

Elementary school districts:

- East Maine School District 63: Melzer School, Nelson School.[34]

- Golf School District 67: Hynes Elementary School, Golf Middle School.[35]

- Skokie/Morton Grove School District 69: Thomas A. Edison School, Madison School, Lincoln Junior High School.[36][37]

- Morton Grove School District 70: Park View School.[38]

High school districts:

- Maine Township High School District 207: Maine East High School.

- Niles Township High Schools District 219: Niles North High School and Niles West High School.

A Muslim K-12 school, MCC Academy, has its secondary school campus in Morton Grove, while its elementary school is in Skokie.[39]

Jerusalem Lutheran School is a Christian Pre-K-8 grade school of the Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod in Morton Grove.[40]

Transportation

[edit]The Morton Grove station provides Metra commuter rail service along the Milwaukee District North Line. Trains travel south to Chicago Union Station, and north to Fox Lake station. Pace provides bus service on multiple routes in the village including on the Pace Pulse Dempster Line.[41]

Notable people

[edit]- Mike Bartlett — former ice hockey player

- Bart Conner — two-time gold medal-winning Olympic gymnast[42]

- Jeffrey Erickson — bank robber[43]

- Jeff Garlin — actor, comedian

- Harvey Mandel — guitarist

- Marlee Matlin — Oscar-winning actress

- Jim Brosnan — MLB pitcher, author

References

[edit]- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 15, 2022.

- ^ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Morton Grove

- ^ "Morton Grove village, Illinois". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 15, 2022.

- ^ Morton Grove Diamond Jubilee (Morton Grove Chamber of Commerce, 1970) pp. 44-46

- ^ Morton Grove, Illinois: 100 years 1895-1995 (Morton Grove Chamber of Commerce 1995) p. 23

- ^ "Heinrich (Henry) Harms - Skokie - LocalWiki".

- ^ Centennial History p. 26

- ^ Centennial History at pp. 28-29

- ^ a b c "Morton Grove, IL". www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org.

- ^ Centennial History pp. 27-28

- ^ Busch, Mary; Mayse-Lillig, Tim; Society, Morton Grove Historical (2013). Morton Grove. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-9881-9.

- ^ Centennial History p. 80

- ^ Centennial History pp. 30-31

- ^ Centennial History p. 88

- ^ Centennial History pp. 31-33

- ^ Centennial History pp. 32-35

- ^ Centennial History pp. 88-91

- ^ "Defunct synagogue's memorial plaques remain". Chicago Tribune.

- ^ "Growing Diversity Brings Challenges for Morton Grove". March 2011.

- ^ "MCC: Past and Present – Muslim Community Center".

- ^ "Morton Grove, Illinois Village Code". Archived from the original on February 13, 2006. Retrieved July 24, 2018.

- ^ Nick Katz (July 1, 2008). "Village likely to lift gun ban after Supreme Court ruling". Morton Grove Champion. Sun-Times Group. Retrieved July 2, 2008.[dead link]

- ^ NRA-ILA (July 18, 2008). "Village of Morton Grove to Repeal Gun Ban". NRA-ILA News. Archived from the original on September 15, 2008. Retrieved July 19, 2008.

- ^ "Gazetteer Files". Census.gov. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 29, 2022.

- ^ "Decennial Census of Population and Housing by Decades". US Census Bureau.

- ^ a b "P2 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Morton Grove village, Illinois". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ a b "P2 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Morton Grove village, Illinois". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved June 28, 2022.

- ^ "P004: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2000: DEC Summary File 1 – Morton Grove village, Illinois". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "Headquarters « Alpha Delta Phi Society". Archived from the original on May 13, 2014. Retrieved May 12, 2014.

- ^ "Village of Morton Grove ACFR" (PDF).

- ^ "The Village of Morton Grove, Illinois". Village of Morton Grove.

- ^ "Right". Archived from the original on October 16, 2005. Retrieved July 9, 2006.

- ^ "East Maine School District 63 / Homepage". www.emsd63.org.

- ^ "Home". golfsd67.ss13.sharpschool.com.

- ^ "Home - Skokie and Morton Grove School Dist 69". www.sd69.org.

- ^ "Edison Elementary School - Skokie and Morton Grove School Dist 69". Archived from the original on November 8, 2005.

- ^ "Welcome to Morton Grove School District 70".

- ^ "Mission & Vision". MCC Academy. Retrieved January 24, 2022.

- ^ "Jerusalem Lutheran Church & School - Home Page". www.jerusalemlutheran.org.

- ^ "RTA System Map" (PDF). Retrieved February 1, 2024.

- ^ "Conner, Bart | The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture". www.okhistory.org. Retrieved June 26, 2018.

- ^ Green, Michelle (March 2, 1992) "Bloody Ending to a Double Life", People. Retrieved March 4, 2020.