Bangor, Maine

Bangor, Maine | |

|---|---|

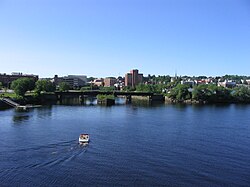

| City of Bangor[1] | |

Bangor skyline | |

| Nickname: The Queen City of the East | |

Location in Penobscot County, Maine | |

| Country | United States |

| U.S. state | Maine |

| County | Penobscot |

| Incorporated | February 12, 1834 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council-Manager |

| • Council Chairman | Sean Faircloth |

| Area | |

• City | 34.59 sq mi (89.59 km2) |

| • Land | 34.26 sq mi (88.73 km2) |

| • Water | 0.33 sq mi (0.85 km2) |

| Elevation | 118 ft (36 m) |

| Population | |

• City | 33,039 |

• Estimate (2012[4]) | 32,817 |

| • Density | 941.4/sq mi (369.8/km2) |

| • Metro | 153,923 |

| Demonym | Bangorean[5] |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (Eastern) |

| ZIP codes | 04401-04402 |

| Area code | 207 |

| FIPS code | 23-02795 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0561558 |

| Website | www.bangormaine.gov |

Bangor (/ˈbæŋɡɔːr/ BANG-gor) is a city in the U.S. state of Maine. The city proper has a population of 33,039, while the metropolitan Bangor metropolitan area has a population of 153,746.

Modern Bangor was established in the mid-1800s with the lumber and shipbuilding industries. Lying on the Penobscot River, logs could be floated downstream from the Maine North Woods and processed at the city's water-powered sawmills, then shipped from Bangor's port to the Atlantic ocean 30 miles downstream, and from there to any port in the world. Evidence of this is still visible in the lumber barons' elaborate Greek Revival and Victorian mansions and the 31 foot high statue of Paul Bunyan. Today, Bangor's economy is based on services and retail, healthcare, and education.

Founded as Condeskeag Plantation, Bangor was incorporated as a New England town in 1791. There are more than 20 communities worldwide named Bangor, of which 15 are in the United States and named after Bangor, Maine. The reason for the choice of name is disputed[6] but it was likely to be either from the eponymous Welsh hymn or from either of two towns of that name in Wales and Northern Ireland.[7] The final syllable is pronounced gor, not ger. In 2015, local public officials, journalists, doctors, policemen, photographers, restaurateurs, TV personalities and Grammy-winning composers came together to record the YouTube video How To Say Bangor.[8]

Bangor has a port of entry at Bangor International Airport, also home to the Bangor Air National Guard Base. Historically Bangor was an important stopover on the great circle route air route between the U.S. East Coast and Europe.

Bangor has a humid continental climate, with cold, snowy winters, and warm summers.

History

European settlement

The Penobscot people have inhabited the area around present-day Bangor for at least 11,000 years[9] and still occupy tribal land on the nearby Penobscot Indian Island Reservation. They practised some agriculture, but less than peoples in southern New England where the climate is milder,[10] and subsisted on what they could hunt and gather.[11] Contact with Europeans was not uncommon during the 1500s because the fur trade was lucrative and the Penobscot were willing to trade pelts for European goods. The site was visited by Portuguese explorer Esteban Gómez in 1524 and by Samuel de Champlain in 1605.[12] The Jesuits established a mission on Penobscot Bay in 1609, which was then part of the French colony of Acadia, and the valley remained contested between France and Britain into the 1750s, making it one of the last regions to become part of New England.

In 1769 Jacob Buswell founded a settlement at the site. By 1772, there were 12 families, along with a sawmill, store, and school, and in 1787 the population was 567. In September 1787 a petition, signed by 19 residents, was sent to the General Court of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts requesting that this designated area be named Sunbury. On the back of it was written "To the care of Dr. Cony, Hallowell". This petition was rejected before 6 October 1788, as the town referred to itself as Penobscot River, west side.[13]

Wars of Independence, 1812, and Civil War

In 1779, the rebel Penobscot Expedition fled up the Penobscot River and ten of its ships were scuttled by the British fleet at Bangor. The ships remained there until the late 1950s, when construction of the Joshua Chamberlain Bridge disturbed the site. Six cannons were removed from the riverbed; five of which are on display throughout the region (one was thrown back into the river by area residents angered that the archeological site was destroyed for the bridge construction).[6]

In 1790, the Kenduskeag Plantation could no longer defer incorporation from the General Court of Massachusetts and in June Rev. Seth Noble hand delivered the petition for incorporation to the State House in Boston. He left the name for the town blank so he could obtain tentative approval. He chose the name of a popular hymn known to be a favorite of Governor John Hancock. He then wrote in Bangor. The incorporation was received on 25 February 1791 and was signed by John Hancock.[13]

During the War of 1812 Bangor and Hampden were looted by the British.

Maine was part of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts until 1820 when it voted to secede from Massachusetts and was admitted to the Union as the 23rd state under the Missouri Compromise.

In 1861, the offices of the Democratic newspaper the Bangor Daily Union, were ransacked by a mob, and the presses and other materials thrown into the street and burned. Editor Marcellus Emery escaped unharmed and it was only after the war that he resumed publishing.[14]

During the American Civil War the locally mustered 2nd Maine Volunteer Infantry Regiment was the first to march out of Maine in 1861, and played a prominent part in the First Battle of Bull Run. The 1st Maine Heavy Artillery Regiment, mustered in Bangor and commanded by a local merchant, lost more men than any other Union regiment in the war (especially in the Second Battle of Petersburg, 1864). The 20th Maine Infantry Regiment held Little Round Top in the Battle of Gettysburg. A bridge connecting Bangor with Brewer is named for Chamberlain, the regiment's leader, who was one of eight Civil War soldiers from Penobscot County towns to receive the Medal of Honor.[15] Bangor's Charles A. Boutelle accepted the surrender of the Confederate fleet after the Battle of Mobile Bay. A Bangor residential street is named for him. A number of Bangor ships were captured on the high seas by Confederate raiders in the Civil War, including the "Delphine", "James Littlefield", "Mary E. Thompson" and "Golden Rocket".[16]

Bangor was near the lands disputed during the Aroostook War, a boundary dispute with Britain in 1838–39. The passion of the Aroostook War signaled the increasing role lumbering and logging were playing in the Maine economy, particularly in the central and eastern sections of the state. Bangor arose as a lumbering boom-town in the 1830s, and a potential demographic and political rival to Portland. Bangor became for a time the largest lumber port in the world, and the site of furious land speculation that extended up the Penobscot River valley and beyond.[17]

Industrialization: lumbering, shipping, and manufacturing

The Penobscot River Maine North Woods drainage basin above Bangor was unattractive to settlement for farming, but well suited to lumbering. Winter snow allowed logs to be dragged from the woods by horse-teams. Carried to the Penobscot or its tributaries, log driving in the snowmelt brought them to waterfall-powered sawmills upriver from Bangor. The sawn lumber was then shipped from the city's docks, Bangor being at the head-of-tide (between the rapids and the ocean) to points anywhere in the world. Shipbuilding was also developed.[18] Bangor capitalists also owned most of the forests. The main markets for Bangor lumber were the East Coast cities. Much was also shipped to the Caribbean and to California during the Gold Rush, via Cape Horn, before sawmills could be established in the west. Bangorians subsequently helped transplant the Maine culture of lumbering to the Pacific Northwest, and participated directly in the Gold Rush themselves. Bangor, Washington; Bangor, California; and Little Bangor, Nevada, are legacies of this contact.[18]

By 1860, Bangor was the world's largest lumber port, with 150 sawmills operating along the river. The city shipped over 150 million boardfeet of lumber a year, much of it in Bangor-built and Bangor-owned ships. In the year 1860, 3,300 lumbering ships passed by the docks.[6]

Many of the lumber barons built elaborate Greek Revival and Victorian houses that still stand in the Broadway Historic District. Bangor has many substantial old churches, and shade trees. The city was so beautiful it was called "The Queen City of the East." The shorter Queen City appellation is still used by some local clubs, organizations, events and businesses.[19]

In addition to shipping lumber, 19th-century Bangor was the leading producer of moccasins, shipping over 100,000 pairs a year by the 1880s.[20] Exports also included bricks, leather, and even ice (which was cut and stored in winter, then shipped to Boston, and even China, the West Indies and South America).[6]

Bangor had certain disadvantages compared to other East Coast ports, including its rival Portland, Maine. Being on a northern river, its port froze during the winter, and it could not take the largest ocean-going ships. The comparative lack of settlement in the forested hinterland also gave it a comparatively small home market.[21]

In 1844 the first ocean-going iron-hulled steamship in the U.S. was named The Bangor. She was built by the Harlan and Hollingsworth firm of Wilmington, Delaware in 1844, and was intended to take passengers between Bangor and Boston. On her second voyage, however, in 1845, she burned to the waterline off Castine. She was rebuilt at Bath, returned briefly to her earlier route, but was soon purchased by the U.S. government for use in the Mexican–American War.[22]

Modern Bangor

Bangor continued to prosper as the pulp and paper industry replaced lumbering, and railroads replaced shipping.[23] Local capitalists also invested in a train route to Aroostook County in northern Maine (the Bangor and Aroostook Railroad), opening that area to settlement.

Bangor's Hinkley & Egery Ironworks (later Union Ironworks) was a local center for invention in the 19th and early 20th centuries. A new type of steam engine built there, named the "Endeavor", won a Gold Medal at the New York Crystal Palace Exhibition of the American Institute in 1856. The firm won a diploma for a shingle-making machine the following year.[24] In the 1920s, Union Iron Works engineer Don A. Sargent invented the first automotive snow plow. Sargent patented the device and the firm manufactured it for a national market.[25]

Geography

Bangor is located at 44°48′13″N 68°46′13″W / 44.80361°N 68.77028°W (44.803, −68.770).[26] According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 34.59 square miles (89.59 km2), of which 34.26 square miles (88.73 km2) is land and 0.33 square miles (0.85 km2) is water.[2]

A potential advantage that has always eluded exploitation is the city's location between the port city of Halifax, Nova Scotia, and the rest of Canada (as well as New York). As early as the 1870s, the city promoted a Halifax-to-New York railroad, via Bangor, as the quickest connection between North America and Europe (when combined with steamship service between Britain and Halifax). A European and North American Railway was actually opened through Bangor, with President Ulysses S. Grant officiating at the inauguration, but commerce never lived up to the potential. More recent attempts to capture traffic between Halifax and Montreal by constructing an East–West Highway through Maine have also come to naught. Most overland traffic between the two parts of Canada continues to travel north of Maine rather than across it.[27]

Urban development

Fires

- 1856: A large fire destroyed at least 10 downtown businesses and 8 houses, as well as the sheriff's office.[28]

- 1869: The West Market Square fire, from which arose The Phoenix Block (the present Charles Inn). The fire destroyed 10 business blocks and cut off telegraphic communication [29]

- 1872: Another large downtown fire, on Main St., killed 1 and injured 7.[30] The Adams-Pickering Block (architect George W. Orff) replaced the burned section.

- In the Great Fire of 1911, a fire started in a hay shed and spread to the surrounding downtown buildings and blazed through the night into the next day. When the damage was tallied, Bangor had lost its high school, post office & custom house, public library, telephone and telegraph companies, banks, two fire stations, nearly a hundred businesses, six churches, and synagogue and 285 private residences over a total of 55 acres. The area was rebuilt, and in the process became a showplace for a diverse range of architectural styles, including the Mansard style, Beaux Arts, Greek Revival and Colonial Revival,[6] and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places as the Great Fire of 1911 Historic District.

- 1914: The Bangor Opera House burned down, and two firemen were killed by a collapsing wall. A third was badly injured, and three others less seriously.[31]

Urban renewal

The destruction of downtown landmarks such as the old city hall and train station in the late 1960s Urban Renewal Program is now considered to have been a huge planning mistake. It ushered in a decline of the city center that was accelerated by the construction of the Bangor Mall in 1978 and subsequent big-box stores on the city's outskirts.[32] Downtown Bangor began to recover in the 1990s, with bookstores, cafe/restaurants, galleries, and museums filling once-vacant storefronts. The recent re-development of the city's waterfront has also helped re-focus cultural life in the historic center.[33]

Hydrology

Bangor is on the banks of the Penobscot River, close enough to the Atlantic Ocean to be influenced by tides. Upstream, the Penobscot River drainage basin occupies 8,570 square miles in northeastern Maine. Flooding is most often caused by a combination of precipitation and snowmelt. Ice jams can exacerbate high flow conditions and cause acute localized flooding. Conditions favorable for flooding typically occur during the spring months.[34]

In 1807 an ice jam formed below Bangor Village raising the water 10 to 12 feet above the normal highwater mark[35] and in 1887 the freshet caused the Maine Central Railroad Company rails between Bangor and Vanceboro to be covered to a depth of several feet.[35] Bangor’s worst ice jam floods occurred in 1846 and 1902. Both resulted from mid-December freshets that cleared the upper river of ice, followed by cold that produced large volumes of frazil ice or slush which was carried by high flows forming a major ice jam in the lower river. In March of both years, a dynamic breakup of ice ran into the jam and flooded downtown Bangor. Though no lives were lost and the city recovered quickly, the 1846 and 1902 ice jam floods were economically devastating, according to the Army Corps analysis. Both floods occurred with multiple dams in place and little to no ice-breaking in the lower river. The United States Coast Guard began icebreaker operations on the Penobscot in the 1940s, preventing the formation of frozen ice jams during the winter and providing an unobstructed path for ice-out in the spring.[36] Long-term temperature records show a gradual warming since 1894, which may have reduced the ice jam flood potential at Bangor.

In the Groundhog Day gale of 1976 a storm surge went up the Penobscot, flooding Bangor for three hours.[37] At 11:15 am, waters began rising on the river and within 15 minutes had risen a total of 3.7 metres (12 ft) flooding downtown. About 200 cars were submerged and office workers were stranded until waters receded. There were no reported deaths during this unusual flash flood.[38]

Climate

Bangor has a humid continental climate (Köppen Dfb), with cold, snowy winters, and warm summers, and is located in USDA hardiness zone 5a.[39] The monthly daily average temperature ranges from 17.0 °F (−8.3 °C) in January to 68.5 °F (20.3 °C) in July.[40] On average, there are 21 nights annually that drop to 0 °F (−18 °C) or below, and 57 days where the temperature stays below freezing, including 49 days from December through February.[40] There is an average of 5.3 days annually with highs at or above 90 °F (32 °C), with the last year to have not seen such temperatures being 2014.[40] Extreme temperatures range from −32 °F (−36 °C) on February 10, 1948 up to 104 °F (40 °C) on August 19, 1935.[40]

The average first freeze of the season occurs on October 7, and the last May 7, resulting in a freeze-free season of 152 days; the corresponding dates for measurable snowfall, i.e. at least 0.1 in (0.25 cm), are November 23 and April 4.[40] The average seasonal snowfall for Bangor is approximately 66 inches (170 cm), while snowfall has ranged from 22.2 inches (56 cm) in 1979–80 to 181.9 inches (4.62 m) in 1962−63; the record snowiest month was February 1969 with 58.0 inches (147 cm), while the most snow in one calendar day was 30.0 inches (76 cm) on December 14, 1927.[40] Measurable snow occurs in May occurs about one-fourth of all years, while it has occurred just once (1991) in September.[40] A snow depth of at least 3 in (7.6 cm) is on average seen 66 days per winter, including 54 days from January to March, when the snow pack is typically most reliable.

| Climate data for Bangor International Airport, Maine (1981–2010 normals, extremes 1925–2015) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 63 (17) |

60 (16) |

84 (29) |

90 (32) |

96 (36) |

98 (37) |

99 (37) |

104 (40) |

99 (37) |

92 (33) |

75 (24) |

65 (18) |

104 (40) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 27.4 (−2.6) |

31.3 (−0.4) |

40.0 (4.4) |

52.8 (11.6) |

65.1 (18.4) |

74.3 (23.5) |

79.4 (26.3) |

78.2 (25.7) |

69.8 (21.0) |

57.5 (14.2) |

45.3 (7.4) |

33.7 (0.9) |

54.6 (12.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 6.7 (−14.1) |

10.2 (−12.1) |

20.5 (−6.4) |

32.2 (0.1) |

42.4 (5.8) |

52.0 (11.1) |

57.7 (14.3) |

55.9 (13.3) |

47.8 (8.8) |

36.8 (2.7) |

28.5 (−1.9) |

15.5 (−9.2) |

33.9 (1.1) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −29 (−34) |

−32 (−36) |

−16 (−27) |

4 (−16) |

23 (−5) |

29 (−2) |

37 (3) |

29 (−2) |

23 (−5) |

11 (−12) |

−3 (−19) |

−27 (−33) |

−32 (−36) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.89 (73) |

2.52 (64) |

3.38 (86) |

3.62 (92) |

3.64 (92) |

3.76 (96) |

3.46 (88) |

2.98 (76) |

3.83 (97) |

4.17 (106) |

4.20 (107) |

3.48 (88) |

41.93 (1,065) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 19.2 (49) |

14.7 (37) |

11.7 (30) |

3.7 (9.4) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

2.3 (5.8) |

14.4 (37) |

66.1 (168.45) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 10.6 | 9.3 | 11.0 | 11.3 | 12.7 | 12.0 | 11.2 | 10.5 | 9.4 | 11.0 | 11.5 | 12.0 | 132.5 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 7.9 | 6.8 | 4.8 | 1.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.3 | 6.1 | 28.4 |

| Source: NOAA[40] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1800 | 277 | — | |

| 1810 | 850 | 206.9% | |

| 1820 | 1,221 | 43.6% | |

| 1830 | 2,867 | 134.8% | |

| 1840 | 8,627 | 200.9% | |

| 1850 | 14,432 | 67.3% | |

| 1860 | 16,407 | 13.7% | |

| 1870 | 18,289 | 11.5% | |

| 1880 | 16,856 | −7.8% | |

| 1890 | 19,103 | 13.3% | |

| 1900 | 21,850 | 14.4% | |

| 1910 | 24,803 | 13.5% | |

| 1920 | 25,978 | 4.7% | |

| 1930 | 28,749 | 10.7% | |

| 1940 | 29,822 | 3.7% | |

| 1950 | 31,558 | 5.8% | |

| 1960 | 38,912 | 23.3% | |

| 1970 | 33,168 | −14.8% | |

| 1980 | 31,643 | −4.6% | |

| 1990 | 33,181 | 4.9% | |

| 2000 | 31,473 | −5.1% | |

| 2010 | 33,039 | 5.0% | |

| 2014 (est.) | 32,568 | [41] | −1.4% |

| sources:[42] | |||

As of 2008, Bangor is the third most populous city in Maine, as it has been for more than a century. As of 2012, the estimated population of the Bangor Metropolitan Area (which includes Penobscot County) is 153,746, indicating a slight growth rate since 2000, almost all of it accounted for by Bangor.[43] As of 2007, Metro Bangor had a higher percentage of people with high school degrees than the national average (85% compared to 76.5%) and a slightly higher number of graduate degree holders (7.55% compared to 7.16%). It had much higher number of physicians per capita (291 vs. 170), because of the presence of two large hospitals[44]

Historically Bangor received many immigrants as it industrialized. Irish-Catholic and later Jewish immigrants eventually became established members of the community, along with many migrants from Atlantic Canada. Of 205 black citizens who lived in Bangor in 1910, over a third were originally from Canada.[45]

2010 census

As of the census[3] of 2010, there were 33,039 people, 14,475 households, and 7,182 families residing in the city. The population density was 964.4 inhabitants per square mile (372.4/km2). There were 15,674 housing units at an average density of 457.5 per square mile (176.6/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 93.1% White, 1.7% African American, 1.2% Native American, 1.7% Asian, 0.3% from other races, and 2.0% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.5% of the population.

There were 14,475 households of which 24.2% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 32.8% were married couples living together, 12.6% had a female householder with no husband present, 4.2% had a male householder with no wife present, and 50.4% were non-families. 37.9% of all households were made up of individuals and 12.4% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.10 and the average family size was 2.76.

The median age in the city was 36.7 years. 17.8% of residents were under the age of 18; 16% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 26% were from 25 to 44; 25.8% were from 45 to 64; and 14.4% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 48.2% male and 51.8% female.

Economy

Major employers in the region include:[46]

- Services and retail: Hannaford Supermarkets, Bangor Savings Bank, NexxLinx call center, Walmart.

- Finance: The Bangor Savings Bank, founded in 1852, is Maine's largest independent bank; as of 2013, it had more than $2.8 billion in assets[47] and the largest share of the 13-bank Bangor market.[48]

- Healthcare: Eastern Maine Medical Center, Acadia Hospital, St. Joseph's Healthcare, Community Health & Counseling Services.

- Education: University of Maine.

- Manufacturing: General Electric, Verso Paper.

Bangor is the largest market town, distribution center, transportation hub, and media center in a five-county area whose population tops 330,000 and which includes Penobscot, Piscataquis, Hancock, Aroostook, and Washington counties.

Bangor's City Council has approved a resolution opposing the sale of sweat-shop-produced clothing in local stores.[49]

Tourism

Outdoor activities in the Bangor City Forest and other nearby parks, forests, and waterways include hiking, sailing, canoeing, hunting, fishing, skiing, and snowmobiling.

Bangor Raceway at the Bass Park Civic Center and Auditorium offers live, pari-mutuel harness racing from May through July and then briefly in the fall. Hollywood Slots, operated by Penn National Gaming, is a slot machine facility. In 2007, construction began on a $131-million casino complex in Bangor that houses, among other things, a gambling floor with about 1,000 slot machines, an off-track betting center, a seven-story hotel, and a four-level parking garage. In 2011, it was authorized to add table games.

Military installations

Bangor Air National Guard Base is a United States Air National Guard base. Created in 1927 as a commercial field, it was taken over by the U.S. Army just before World War II. In 1968, the base was sold to the city of Bangor, Maine, to become Bangor International Airport but has since continued to host the 101st Air Refueling Wing, Maine Air National Guard, part of the Northeast Tanker Task Force.

In 1990, the USAF East Coast Radar System (ECRS) Operation Center was activated in Bangor with over 400 personnel. The center controlled the over-the-horizon radar's transmitter in Moscow, Maine, and receiver in Columbia Falls, Maine. With the end of the Cold War, the facility's mission of guarding against a Soviet air attack became superfluous, and though it briefly turned its attention toward drug interdiction, the system was decommissioned in 1997 as the SSPARS system installation—the successor to the PAVE PAWS installation—in Massachusetts' Cape Cod Air Force Station reservation fully took over.

Arts and culture

Events

- One of the country's oldest fairs, the Bangor State Fair has occurred annually for more than 150 years. Beginning on the last Friday of July, it features agricultural exhibits, rides, and live performances.

Venues

- The Cross Insurance Center (which replaced the Bangor Auditorium in 2013)

- Darling's Waterfront Pavilion

Cultural institutions

- The University of Maine Museum of Art and the Maine Discovery Museum, a major children's museum was founded in 2001 in the former Freese's Department Store.

- The Bangor Historical Society, in addition to its exhibit space, maintains the historic Thomas A. Hill House.[50]

- The Bangor Police Department has a police museum with some items dating to the 18th century.

- Fire Museum at the former State Street Fire Station.

- The Cole Land Transportation Museum.

- The Bangor Symphony Orchestra.

- The Penobscot Theatre Company

- The Collins Center for the Arts

Architecture

Many buildings and monuments are listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The city has also had a municipal Historic Preservation Commission since the early 1980s.[51] Bangor contains many Greek Revival. Victorian, and Colonial Revival houses. Some notable architecture:

- The Thomas Hill Standpipe, a shingle style structure.

- The Hammond Street Congregation Church.

- The St. John's Catholic Church.

- The Bangor House Hotel, now converted to apartments, is the only survivor among a series of "Palace Hotels" designed by Boston architect Isaiah Rogers, which were the first of their kind in the United States.[52]

- The country's second oldest garden cemetery, is the Mt. Hope Cemetery, designed by Charles G. Bryant.[51]

- Richard Upjohn, British-born architect and early promoter of the Gothic Revival style, received some of his first commissions in Bangor, including the Isaac Farrar House (1833), Samuel Farrar House (1836), Thomas A. Hill House (presently owned by the Bangor Historical Society), and St. John's Church (Episcopal, 1836–39).

- Bangor Public Library by Peabody and Stearns.

- The Eastern Maine Insane Hospital by John Calvin Stevens.[53]

- The William Arnold House of 1856, an Italianate style mansion and home to author Stephen King. Its wrought-iron fence with bat and spider web motif is King's own addition.[51]

Public art and monuments

The bow-plate of the battleship USS Maine, whose destruction in Havana, Cuba, presaged the start of the Spanish–American War, survives on a granite memorial by Charles Eugene Tefft in Davenport Park.

Bangor has a large fiberglass-over-metal statue of mythical lumberman Paul Bunyan by Normand Martin (1959).

There are three large bronze statues in downtown Bangor by sculptor Charles Eugene Tefft of Brewer, including the Luther H. Peirce Memorial, commemorating the Penobscot River Log-Drivers; a statue of Hannibal Hamlin at Kenduskeag Mall; and an image of "Lady Victory" at Norumbega Parkway.

The abstract aluminum sculpture "Continuity of Community" (1969) on the Bangor Waterfront, formerly in West Market Square, is by the Castine sculptor Clark Battle Fitz-Gerald.

The U.S. Post Office in Bangor contains Yvonne Jacquette's 1980 three-part mural "Autumn Expansion".

A 1962 bronze commemorating the 2nd Maine Volunteer Infantry Regiment by Wisconsin sculptor Owen Vernon Shaffer stands at the entrance to Mt. Hope Cemetery.

Sports

Since 2002, Bangor has been home to Little League International's Senior League World Series.

Bangor was home to two minor league baseball teams affiliated with the 1995-98 Northeast League: the Bangor Blue Ox (1996–97) and the Bangor Lumberjacks (2003–04). Even earlier the Bangor Millionaires (1894–96) played in the New England League.

Vince McMahon promoted his first professional wrestling event in Bangor in 1979. In 1985, the WWC Universal Heavyweight Championship changed hands for the first time outside of Puerto Rico at an IWCCW show in Bangor.[54]

The Penobscot is a salmon-fishing river; the Penobscot Salmon Club traditionally sent the first fish caught to the President of the United States. From 1999 to 2006, low fish stocks resulted in a ban on salmon fishing. Today, the wild salmon population (and the sport) is slowly recovering. The Penobscot River Restoration Project is working to help the fish population by removing some dams north of Bangor.[55]

The Kenduskeag Stream Canoe Race, a white-water event which begins just north of Bangor in Kenduskeag, has been held since 1965.

Government

Bangor is the county seat of Penobscot County.

Since 1931, Bangor has had a Council-Manager form of government. The nine-member City Council is a non-partisan body, with three city councilors elected to three-year terms each year. The nine council members elect the Chair of the City Council, who is referred to informally as the mayor, and plays the role when there is a ceremonial need. As of 2013, the council members are Nelson Durgin, Patricia Blanchette, Joseph Baldacci, David Nealley, Ben Sprague (chair), James Gallant, Pauline Civiello, Gibran Graham, and Joshua Plourde.

In 2007, Bangor was the first city in the U.S. to ban smoking in vehicles carrying passengers under the age of 18.[56]

In 2012, Bangor's City Council passed an order in support of same-sex marriage in Maine. In 2013, the City of Bangor also signed an amicus brief to the United States Supreme Court calling for the federal Defense of Marriage Act to be struck down.[57]

Voter registration

| Voter Registration and Party Enrollment as of October 2014[58] | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Total Voters | Percentage | Unenrolled | 8,708 | 39.80% | Democratic | 7,054 | 32.24% | Republican | 5,571 | 25.46% | Green Independent | 541 | 2.47% | |

| Total | 21,874 | 100% | |||||||||||||

Law and order

In 2008 Bangor's crime rate was the second-lowest among American metropolitan areas of comparable size.[59] As of 2014 Bangor had the third highest rate of property crime in Maine.[60]

The arrival of Irish immigrants from nearby Canada beginning in the 1830s, and their competition with locals for jobs, sparked a deadly sectarian riot in 1833 that lasted for days and had to be put down by militia. Realizing the need for a police force, the town incorporated as The City of Bangor in 1834.[61] In the 1800s, sailors and loggers gave the city a reputation for roughness; their stomping grounds were known as the "Devil's Half Acre".[62] The same name was also applied, at roughly the same time, to The Devil's Half-Acre, Pennsylvania.

Although Maine was the first "dry" state (i.e. the first to prohibit the sale of alcohol, with the passage of the "Maine law" in 1851), Bangor managed to remain "wet". The city had 142 saloons in 1890. A look-the-other-way attitude by local police and politicians (sustained by a system of bribery in the form of ritualized fine-payments known as "The Bangor Plan") allowed Bangor to flout the nation's most long-standing state prohibition law.[63] In 1913, the war of the "drys" (prohibitionists) on "wet" Bangor escalated when the Penobscot County Sheriff was impeached and removed by the Maine Legislature for not enforcing anti-liquor laws. His successor was asked to resign by the Governor the following year for the same reason, but refused. A third sheriff was removed by the Governor in 1918, but promptly re-nominated by the Democratic Party. Prohibitionist Carrie Nation had been forcibly expelled from the Bangor House hotel in 1902 after causing a disturbance.[64]

In October 1937, "public enemy" Al Brady and another member of his "Brady Gang" (Clarence Shaffer) were killed in the bloodiest shootout in Maine's history. FBI agents ambushed Brady, Shaffer, and James Dalhover on Bangor's Central Street after they had attempted to purchase a Thompson submachinegun from Dakin's Sporting Goods downtown.[65] Brady is buried in the public section of Mount Hope Cemetery, on the north side of Mount Hope Avenue.[66] Until recently, Brady's grave was unmarked. A group of schoolchildren erected a wooden marker over his grave in the 1990s, which was replaced by a more permanent stone in 2007.[67]

Education

- Universities and colleges

- The University of Maine (originally The Maine State College) was founded in Orono in 1868. It is part of the University of Maine System.

- A vocationally-oriented University College of Bangor, associated with the University of Maine at Augusta.

- Eastern Maine Community College established in 1966 by the Maine State Legislature, under the authority of the State Board of Education, EMCC was originally known as Eastern Maine Vocational Technical Institute (EMVTI). The college was moved in 1968 from temporary quarters in downtown Bangor to its present campus on Hogan Road. In 1986 the 112th Legislature created a quasi-independent system with a board of trustees to govern all six of Maine’s VTIs, and in 1989 another law changed the names of these institutions to more accurately reflect their purpose and activities; EMVTI thus became Eastern Maine Technical College (EMTC). The name of the College changed again in 2003 from “Technical” to “Community” to more accurately reflect its purpose.

- Husson University enrolls about 3,500 students a year in a variety of undergraduate and graduate programs.

- Beal College is a small institution oriented toward career training.

- The Bangor Theological Seminary, founded in 1814, is the only accredited graduate school of religion in northern New England.

- Secondary schools:

- The public Bangor High School. In 2013 it was named a National Silver Award winner by U.S. News & World Report's "America's Best High Schools".[68]

- The private John Bapst Memorial High School. In 2012 it was ranked in the top 20% nationally by the Washington Post High School Challenge.[69]

- Two public middle schools and one private, and elementary schools.

Media

The Bangor region has a large number of media outlets for an area its size. The city has an unbroken history of newspaper publishing extending from 1815. Almost thirty dailies, weeklies, and monthlies had been launched there by the end of the Civil War .[14]

The Bangor Daily News was founded in the late 19th century, and is one of the few remaining family-owned newspapers left in the United States. The Maine Edge is published from Bangor.

Bangor has more than a dozen radio stations and seven television stations, including WLBZ 2 (NBC), WABI 5 (CBS), WVII 7 (ABC), WBGR 33, and WFVX-LD 22 (Fox). WMEB 12, licensed to nearby Orono, is the area's PBS member station. Radio stations in the city include WKIT-FM and WZON, owned by Zone Radio Corporation, a company owned by Bangor resident novelist Stephen King. WHSN is a non-commercial alternative rock station licensed to Bangor and run and operated by staff and students at the New England School of Communications located on the campus of Husson University. Several other stations in the market are owned by Blueberry Broadcasting and Cumulus Media.

Infrastructure

Road

Bangor sits along interstates I-95 and I-395; U.S. highways US 1A, US 2, US Route 2A; and state routes SR 9, SR 15, SR 15 Business, SR 100, SR 202, and SR 222. Three major bridges connect the city to neighboring Brewer: Joshua Chamberlain Bridge (carrying US 1A), Penobscot River Bridge (carrying SR 15), and the Veterans Remembrance Bridge (carrying I-395).

Daily intercity bus service from Bangor proper is provided by two companies. Concord Coach Lines connects Bangor with Augusta, Portland, several towns in Maine's midcoast region, and Boston, Massachusetts. Cyr Bus Lines provides daily service to Caribou and several northern Maine towns along I-95 and Route 1.[70] The area is also served by Greyhound, which operates out of Dysart's Truck Stop in neighboring Hermon. West's Bus Service provides service between Bangor and Calais.[71]

In 2011, Acadian Lines ended bus service to Saint John, New Brunswick, because of low ticket sales.[72]

The BAT Community Connector system offers public transportation within Bangor and to adjacent towns such as Orono. There is also a seasonal (summer) shuttle between Bangor and Bar Harbor.

Rail

Freight service is provided by Pan Am Railways. Passenger rail service was provided most recently by the New Brunswick Southern Railway, which in 1994 discontinued its route to Saint John, New Brunswick. Rail accidents:

- 1869: The Black Island Railroad Bridge north of Old Town, Maine collapsed under the weight of a Bangor and Piscataquis Railroad train, killing 3 crew and injuring 7–8 others.[73]

- 1871: A bridge in Hampden collapsed under the weight of a Maine Central Railroad train approaching Bangor, killing 2 and injuring 50.[74]

- 1898: A Maine Central Railroad train crashed near Orono killing 2 and fatally injuring 4. The president of the railroad and his wife were also on board in a private car, but escaped injury. Train Wrecked in Maine

- 1899: The collapse of a gangway between a train and a waiting ferry at Mount Desert sent 200 members of a Bangor excursion party into the water, drowning 20.

- 1911: A head-on collision of two trains north of Bangor, in Grindstone, killed 15, including 5 members of the Presque Isle Brass Band.[75]

Air

Bangor International Airport (IATA: BGR, ICAO: KBGR) is a joint civil-military public airport on the west side of the city. It has a single runway measuring 11,439 by 200 ft (3,487 by 61 m). Bangor is the last (or first) American airport along the great circle route route between the U.S. East Coast and Europe, and in the 1970s and '80s it was a refuelling stop, until the development of longer-range jets in the 1990s.[27]

Health care

Bangor is home to two large hospitals, the Eastern Maine Medical Center and the Catholic-affiliated St. Joseph Hospital. As of 2012, the Bangor Metropolitan Statistical Area (Penobscot County) ranked in the top fifth for physicians per capita nationally (74th of 381). It is also within the top ten in the Northeast (i.e. north of Pennsylvania) and the top five in New England.[76] In 2013 U.S. News and World Report ranked the Eastern Maine Medical Center as the second best hospital in Maine.[77]

In 1832 a cholera epidemic in St. John, New Brunswick (part of the Second cholera pandemic) sent as many as eight hundred poor Irish immigrants walking to Bangor. This was the beginning of Maine's first substantial Irish-Catholic community. Competition with Yankees for jobs caused a riot and resulting fire in 1833.[61] n In 1849-50 the Second cholera pandemic reached Bangor itself, killing 20–30 within the first week.[78] 112 had died by Oct, 1849 [79] The final death toll was 161. A late outbreak of the disease in 1854 killed seventeen others. The victims in most cases were poor Irish immigrants.[80] In 1872 a smallpox epidemic closed local schools.* 1918: The Spanish flu pandemic of 1918, which was global in scope, struck over a thousand Bangoreans and killed more than a hundred. This was the worst 'natural disaster' in the city's history since the Cholera epidemic of 1849.

Notable people

Sister cities

Saint John, New Brunswick, Canada

Saint John, New Brunswick, Canada Harbin, China

Harbin, China

References

- ^ "City of Bangor, ME: Charter". Retrieved 2011-01-24.

- ^ a b "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2012-11-23.

- ^ a b "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2012-11-23.

- ^ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2013-05-24.

- ^ "Chronicling America: About The Bangorean. (Bangor, Me.)". Library of Congress. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Bangor CVB http://www.visitbangormaine.com/index.php?id=2&sub_id=285. Retrieved 22 December 2015.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Hale, John (28 June 1984). "But for a favorite hymn, Bangor might have been Sunbury". Bangor Daily News. Retrieved 10 January 2016.

- ^ Burnham, Emily. "Bangor, Wales agrees with "We Are Bangor" video — it's -GOR, not -GER". Bangor Daily News. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- ^ The Wabanakis of Maine and the Maritimes. American Friends Service Committee, 1989.

- ^ James Francis. "Burnt Harvest: Penobscot People and Fire", Maine History 44, 1 (2008) 4-18.

- ^ Wabanakis of Maine and the Maritimes

- ^ Fischer, David Hackett (2009). Champlain's Dream. Simon and Schuster. pp. 180–181. ISBN 978-1-4165-9333-1.

- ^ a b Fisher, Carol B. Smith (2010). Rev. Seth Noble : a Revolutionary War soldier's promise of America : and, the founding of Bangor, Maine and Columbus, Ohio. Westminster, Md.: Heritage Books. p. 136-145. ISBN 978-0788450495.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ a b The Press of Penobscot Co., Maine, John E, Godfrey, Retrieved 29 December 2007

- ^ Medal of Honor Recipients Associated with the State of Maine. According to this list, 4 Civil War MOH recipients were born in Bangor, and one each in Brewer (Chamberlain), Old Town, Edinburg, and LaGrange

- ^ "A Salute To The Navy And All The Ships At Sea". Maine State Archives. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2008-01-27.

- ^ David C. Smith, A History of Lumbering in Maine, 1861–1960 (University of Maine Press, 1972)

- ^ a b Richard George Wood, A History of Lumbering in Maine, 1820–61 (Orono: University of Maine Press, 1971)

- ^ "Maine's Queen City Since 1834". Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ^ Barnstable Patriot, Oct. 21, 1884, p. 1

- ^ David Demeritt, "Boards, Barrels, and Boxshooks: The Economics of Downeast Lumber in 19th Century Cuba" Forest and Conservation History, v. 35, no. 3 (July 1991), p. 112

- ^ Edward Mitchell Blanding, "Bangor, Maine", New England Magazine, v. XVI, no. 1 (Mar. 1897), p. 235

- ^ David Clayton Smith, A History of Lumbering in Maine, 1861–1960 (Orono: University of Maine Press, 1972)

- ^ Annual Report of the American Institute of the City of New York (1856), p. 178

- ^ The American City Magazine, v. 35 (July–Dec. 1926), p. 149

- ^ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- ^ a b Gregory Clancey, Local Memory and Worldly Narrative: The Remote City in America and Japan in Urban Studies, Vol. 41, No. 12, pp. 2335–2355 (2004)

- ^ New York Times, "The Bangor Fires", July 1, 1856, p. 1

- ^ Hartford Weekly Times, Jan. 9, 1869, p. 1

- ^ The Bangor Fire New York Times, Oct. 13, 1872

- ^ "Firemen Killed in Bangor", Boston Evening Transcript, Jan. 15, 1914, p. 5

- ^ Bangor in Focus: Urban Renewal Retrieved June 29, 2008

- ^ "Major Development Initiatives: Waterfront Redevelopment". City of Bangor. Archived from the original on 22 February 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-26.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Maine River Basin Report" (PDF). Retrieved 19 December 2015.

- ^ a b Thomson, M; Gannon, W; Thomas, M; Hayes, G (1964). "Historical Floods in New England" (PDF). US Geological Survey. Retrieved 19 December 2015.

- ^ Schmitt, Catherine. "Ice-out on the Penobscot". Retrieved 19 December 2015.

- ^ THE MAINE CLIMATE. Maine State Climate Office. March 2002.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "The Great Bangor Storm Surge Flash Flood". National Weather Service. Retrieved 2015-02-10.

- ^ United States Department of Agriculture. United States National Arboretum. USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map [Retrieved 2015-02-25].

- ^ a b c d e f g h "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2015-02-25.

- ^ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2014". Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ [1], accessed March, 2010.

- ^ http://www.topmetroarea.com accessed Jan. 11, 2014

- ^ http://www.bestplaces.net . Sperling's Best Places: Bangor Maine, retrieved January 17, 2008

- ^ Maureen Elgersman Lee, Black Bangor: African-Americans in a Maine Community, 1880–1950 (University Press of New England, 2005)

- ^ "Major Employers". Retrieved 12 December 2015.

- ^ http://www.bangor.com/uploadedFiles/Bangor_com/content/About_Us/News/2013%20JD%20Power%20Press%20Release.pdf

- ^ "The First to open branch bank in Bangor". The Bangor Daily News.

- ^ Edes, Katherine C.; Saucier, Dale. "Maine citizens must take a stand against sweatshops". Bangor Daily News. Retrieved 2015-04-20.

- ^ "Bangor Historical Society". Retrieved 2008-01-29.

- ^ a b c Deborah Thompson, Bangor, Maine, 1769–1914: An Architectural History (Orono: University of Maine Press, 1988)

- ^ Bangor In Focus: The Bangor House Retrieved June 29, 2008

- ^ Bangor In Focus: Bangor Mental Health Institute Retrieved June 28, 2008

- ^ "W.W.C. Universal Heavyweight Title". May 19, 2007. Archived from the original on 9 July 2007. Retrieved 2007-06-29.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Penobscot River Restoration Project". Archived from the original on 25 February 2008. Retrieved 2008-03-02.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Area Information". Bangor CVB. Retrieved 22 December 2015.

- ^ McCrea, Nick; Staff, B. D. N. "Bangor council signs on to call for repeal of DOMA; renews Diamonds liquor, amusement licenses". Retrieved 2015-04-20.

- ^ "REGISTERED & ENROLLED VOTERS - STATEWIDE" (PDF). Retrieved 5 December 2014.

- ^ Bangor Maine: the Official Web Site of the City of Bangor, retrieved 18 Jan., 2008

- ^ [2], retrieved 12 Dec., 2015

- ^ a b James H. Mundy and Earle G. Shettleworth, The Flight of the Grand Eagle: Charles G. Bryant, Architect and Adventurer (Augusta: Maine Historic Preservation Commission, 1977)

- ^ Doris A. Isaacson, ed., Maine: A Guide Down East (Rockland, Me.: Courier-Gazette, Inc., 1970), pp. 163–172

- ^ New York Times, Jan. 8, 1890, p. 1; Ibid, Aug. 30, 1903, p. 3

- ^ "Carrie Nation Ejected",Pittsburgh Press, Aug. 30, 1902, p. 1

- ^ Bill Vanderpool "Walter R. Walsh: An Amazing Life" American Rifleman November 2010 p.84

- ^ "The Brady Gang". Bangor in Focus. Retrieved 2008-02-26.

- ^ Bangor Daily News, Friday, September 07, 2007

- ^ "Search Maine High Schools - US News". usnews.com.

- ^ "John Bapst ranked No. 1 high school in northern New England by Washington Post". The Bangor Daily News.

- ^ "CYR Bus Line: Maine: Charter Tours & Bus Services". Cyr Bus Lines: Maine.

- ^ "WEST BUS SERVICE". westbusservice.com.

- ^ "Maine to Canada bus service to end". 16 February 2011. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- ^ Fearful Railroad Accident New York Times, Sept. 2, 1869, p. 1

- ^ New York Times, Aug. 10, 1871

- ^ New York Times, July 29, 1911

- ^ http://healthprovidersdata.com/statistics/metro-areas.aspx., accessed Jan. 11, 2014

- ^ http://health.usnews.com/best-hospitals/area/me/specialty

- ^ Austin Jacobs, A History and Description of New England (Boston, 1859), p. 46; see letter of Samuel Gilman to his wife, Sept. 2, 1849, on-line at Maine Memory Network

- ^ The Public Ledger (Newfoundland), Oct. 2, 1849, p. 2

- ^ Williams, Chase, and Co., History of Penobscot County, Maine (1882), p. 714

External links

Media related to Bangor, Maine at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Bangor, Maine at Wikimedia Commons Bangor, Maine travel guide from Wikivoyage

Bangor, Maine travel guide from Wikivoyage