Chinese Exclusion Act: Difference between revisions

| Line 51: | Line 51: | ||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

* [[Chinese Exclusion]] |

|||

* [[Chinese American]] |

* [[Chinese American]] |

||

* [[Chinese American history]] |

* [[Chinese American history]] |

||

* [[List of United States immigration legislation]] |

* [[List of United States immigration legislation]] |

||

* ''[[United States v. Wong Kim Ark]]'', which held that the Chinese Exclusion Act could not overrule the citizenship of those born in the U.S. to Chinese parents |

* ''[[United States v. Wong Kim Ark]]'', which held that the Chinese Exclusion Act could not overrule the citizenship of those born in the U.S. to Chinese parents |

||

* [[Chinese massacre of 1871]] |

|||

* [[Rock Springs massacre]] |

|||

* [[Sinophobia]] |

|||

* [[Yellow Peril]] |

|||

* [[White Australia policy]] |

* [[White Australia policy]] |

||

* [[Chinese Immigration Act, 1923]] |

* [[Chinese Immigration Act, 1923]] |

||

* [[New Zealand head tax]] |

|||

* [[Head tax (Canada)]] |

|||

* [[Theodore Roosevelt]] Extension |

|||

==Footnotes== |

==Footnotes== |

||

Revision as of 23:00, 14 April 2013

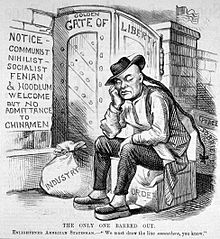

The Chinese Exclusion Act was a United States federal law signed by Chester A. Arthur on May 6, 1882, following revisions made in 1880 to the Burlingame Treaty of 1868. Those revisions allowed the U.S. to suspend Chinese immigration, a ban that was intended to last 10 years. This law was repealed by the Magnuson Act on December 17, 1943.

Background

The first significant Chinese immigration to America began with the California Gold Rush of 1848-1855, and continued with subsequent large labor projects, such as the building of the First Transcontinental Railroad. During the early stages of the gold rush, when surface gold was plentiful, the Chinese were tolerated, if not well received.[1] As gold became harder to find and competition increased, animosity toward the Chinese and other foreigners increased. After being forcibly driven from the mines, most Chinese settled in enclaves in cities, mainly San Francisco, and took up low end wage labor such as restaurant and laundry work.[citation needed] With the post Civil War economy in decline by the 1870s, anti-Chinese animosity became politicized by labor leader Denis Kearney and his Workingman's Party[2] as well as by California Governor John Bigler, both of whom blamed Chinese "coolies" for depressed wage levels. Another significant anti-Chinese group organized in California during this same era was the Supreme Order of Caucasians with some 60 chapters statewide.[citation needed]

Chinese Gold Rush in California

Early on, the California government did not wish to exclude Chinese migrant workers from immigration because they provided essential tax revenue which helped fill the fiscal gap of California.[citation needed] Only later, when there was enough money did the government cease to oppose Chinese exclusion. By 1860 the Chinese were the largest immigrant group in California. The Chinese workers provided cheap labor and did not use any of the government infrastructure (schools, hospitals, etc.) because the Chinese migrant population was predominantly made up of healthy male adults.[3] As time passed and more and more Chinese migrants arrived in California, violence would often break out in cities such as Los Angeles. By 1878 Congress decided to act and passed legislation excluding the Chinese, but this was vetoed by President Hayes. Once the Chinese Exclusion Bold textct was finally passed in 1882, California went further by passing various laws that were later held to be unconstitutional.[4] After the act was passed most Chinese families were faced with a dilemma: stay in the United States alone or go back to China to reunite with their families.[5] Although there was widespread dislike for the Chinese, some capitalists and entrepreneurs resisted their exclusion based on economic factors.[6]

The Act

The Chinese Exclusion Act was one of the most significant restrictions on free immigration in U.S. history. For the first time, Federal law proscribed entry of an ethnic working group on the premise that it endangered the good order of certain localities. The Act excluded Chinese "skilled and unskilled laborers employed in mining" from entering the country for ten years under penalty of imprisonment and deportation. Many Chinese were relentlessly beaten just because of their race.[7][8] The few Chinese non-laborers who wished to immigrate had to obtain certification from the Chinese government that they were qualified to immigrate, which tended to be difficult to prove.[8] Volpp argues that the "Chinese Exclusion Act" is a misnomer, in that it is assumed to be the starting point of Chinese exclusionary laws in the United States. She suggests attending to the intersections of race, gender, and U.S. citizenship in order to both understand the restraints of such a historical tendency and make visible Chinese female immigration experiences, including the Page Act of 1875.[9]

The Chinese Exclusion Act required the few nonlaborers who sought entry to obtain certification from the Chinese government that they were qualified to immigrate. But this group found it increasingly difficult to prove that they were not laborers because the 1882 act defined excludables as “skilled and unskilled laborers and Chinese employed in mining.” Thus very few Chinese could enter the country under the 1882 law.

The Act also affected Asians who had already settled in the United States. Any Chinese who left the United States had to obtain certifications for reentry, and the Act made Chinese immigrants permanent aliens by excluding them from U.S. citizenship.[7][8] After the Act's passage, Chinese men in the U.S. had little chance of ever reuniting with their wives, or of starting families in their new homes.[7]

Amendments made in 1884 tightened the provisions that allowed previous immigrants to leave and return, and clarified that the law applied to ethnic Chinese regardless of their country of origin. The Scott Act (1888) expanded upon the Chinese Exclusion Act, prohibiting reentry after leaving the U.S. The Act was renewed for ten years by the 1892 Geary Act, and again with no terminal date in 1902.[8] When the act was extended in 1902, it required "each Chinese resident to register and obtain a certificate of residence. Without a certificate, he or she faced deportation."[8]

Between 1882 and 1905, about 10,000 Chinese appealed against negative immigration decisions to federal court, usually via a petition for habeas corpus.[10] In most of these cases, the courts ruled in favor of the petitioner.[10] Except in cases of bias or negligence, these petitions were barred by an act that passed Congress in 1894 and was upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in U.S. vs Lem Moon Sing (1895). In U.S. vs Ju Toy (1905), the U.S. Supreme Court reaffirmed that the port inspectors and the Secretary of Commerce had final authority on who could be admitted. Ju Toy's petition was thus barred despite the fact that the district court found that he was an American citizen. The Supreme Court determined that refusing entry at a port does not require due process and is legally equivalent to refusing entry at a land crossing. This ruling triggered a brief boycott of U.S. goods in China.

One of the critics of the Chinese Exclusion Act was the anti-slavery/anti-imperialist Republican Senator George Frisbie Hoar of Massachusetts who described the Act as "nothing less than the legalization of racial discrimination."[11]

The laws were driven largely by racial concerns; immigration of persons of other races was unlimited during this period.[12]

On the other hand, many people strongly supported the Chinese Exclusion Act, including the Knights of Labor, a labor union, who supported it because it believed that industrialists were using Chinese workers as a wedge to keep wages low.[13] Among labor and leftist organizations, the Industrial Workers of the World were the sole exception to this pattern. The IWW openly opposed the Chinese Exclusion Act from its inception in 1905.[14]

For all practical purposes, the Exclusion Act, along with the restrictions that followed it, froze the Chinese community in place in 1882. Limited immigration from China continued until the repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1943. From 1910 to 1940, the Angel Island Immigration Station on what is now Angel Island State Park in San Francisco Bay served as the processing center for most of the 56,113 Chinese immigrants who are recorded as immigrating or returning from China; upwards of 30% more who showed up were returned to China. Furthermore, after the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, which destroyed City Hall and the Hall of Records, many immigrants (known as "paper sons") claimed that they had familial ties to resident Chinese-American citizens. Whether these were true or not cannot be proven.

The Chinese Exclusion Act gave rise to the first great wave of commercial human smuggling, an activity that later spread to include other national and ethnic groups.[15]

Later, the Immigration Act of 1924 restricted immigration even further, excluding all classes of Chinese immigrants and extending restrictions to other Asian immigrant groups.[7] Until these restrictions were relaxed in the middle of the twentieth century, Chinese immigrants were forced to live a life apart, and to build a society in which they could survive on their own (Chinatown).[7]

Furthermore, the Chinese Exclusion Act did not address the problems that whites were facing; in fact, the Chinese were quickly and eagerly replaced by the Japanese, who assumed the role of the Chinese in society. Unlike the Chinese, some Japanese were even able to climb the rungs of society by setting up businesses or becoming truck farmers.[16] However, the Japanese were later targeted in the National Origins Act of 1924, which banned immigration from east Asia entirely.

In 1891 the Government of China refused to accept the U.S. senator Mr. Henry W. Blair as U.S. Minister to China due to his abusive remarks regarding China during negotiation of the Chinese Exclusion Act.[17]

Repeal and current status

The Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed by the 1943 Magnuson Act, which permitted Chinese nationals already residing in the country to become naturalized citizens and stop hiding from the threat of deportation. It also allowed a national quota of 105 Chinese immigrants per year. Large scale Chinese immigration did not occur until the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965. Despite the fact that the exclusion act was repealed in 1943, the law in California that Chinese people were not allowed to marry whites was not repealed until 1948.[18][19] Other states had such laws until 1967,[20] when the United States Supreme Court unanimously ruled in Loving v. Virginia that anti-miscegenation laws are unconstitutional.

Even today, although all its constituent sections have long been repealed, Chapter 7 of Title 8 of the United States Code is headed "Exclusion of Chinese."[21] It is the only chapter of the 15 chapters in Title 8 (Aliens and Nationality) that is completely focused on a specific nationality or ethnic group.

On June 18, 2012, the United States House of Representatives passed a resolution introduced by Congresswoman Judy Chu, that formally expresses the regret of the House of Representatives for the Chinese Exclusion Act, which imposed almost totalestrictions on Chinese immigration and naturalization and denied Chinese-Americans basic freedoms because of their ethnicity. This was only the fourth time that the U.S. Congress issued an apology to a group of people.[22]

See also

- Chinese American

- Chinese American history

- List of United States immigration legislation

- United States v. Wong Kim Ark, which held that the Chinese Exclusion Act could not overrule the citizenship of those born in the U.S. to Chinese parents

- White Australia policy

- Chinese Immigration Act, 1923

Footnotes

- ^ Norton, Henry K. (1924). The Story of California From the Earliest Days to the Present. Chicago: A.C. McClurg & Co. pp. 283–296.

- ^ See, e.g., http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/5046/%7C

- ^ Kanazawa, Mark. "Immigration, Exclusion, and Taxation: Anti-Chinese Legislation Gold Rush in California". The Journal of Economic History, Vol. 65, No. 3 (Sep., 2005), pp. 779-805. Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of the Economic History Association.

- ^ Cole, L. Cheryl."Chinese Exclusion: The Capitalist Perspective of the Sacramento Union, 1850-1882".California History, Vol. 57, No. 1, The Chinese in California (Spring, 1978), pp. 8-31. Published by: California Historical Society

- ^ Chew, Kenneth and Liu, John. "Hidden in Plain Sight: Global Labor Force Exchange in the Chinese American Population, 1880-1940". Population and Development Review, Vol. 30, No. 1 (Mar., 2004), pp. 57-78.Published by: Population HgffgtgtgCouncil

- ^ Miller, Joaquin. "The Chinese and the Exclusion Act". The North American Review, Vol. 173, No. 541 (Dec., 1901), pp. 782-789. Published by: University of Northern Iowa

- ^ a b c d e "Exclusion". Library of Congress. 2003-09-01. Retrieved 2010-01-25.

- ^ a b c d e usnews.com: The People's Vote: Chinese Exclusion Act (1882)

- ^ Leti Volpp "Divesting Citizenship: On Asian American History and the Loss of Citizenship Through Marriage" The Regents of the University of California. UCLA Law Review (2005).

- ^ a b Daniel, Roger, "Book Review"

- ^ Roger Daniels, Coming to America, p271.

- ^ Chin, Gabriel J., (1998) UCLA Law Review vol. 46, at 1 "Segregation's Last Stronghold: Race Discrimination and the Constitutional Law of Immigration"

- ^ Kennedy, David M. Cohen, Lizabeth, Bailey, Thomas A. The American Pageant. New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2002

- ^ Choi, Jennifer Jung Hee. The Rhetoric of Inclusion: The I.W.W. and Asian Workers

- ^ Zhang, Sheldon (2007). Smuggling and trafficking in human beings: all roads lead to America. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-275-98951-4.

- ^ Alan Brinkley's American History: A Survey, 12th Edition

- ^ E. Denza, Commentary to the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations, Third Ed. Oxford University Press 2008, p. 51

- ^ Chin, Gabriel; Karthikeyan, Hrishi (2002). Asian Law Journal vol. 9 "Preserving Racial Identity: Population Patterns and the Application of Anti-Miscegenation Statutes to Asian Americans, 1910-1950"

- ^ See Perez v. Sharp, 32 Cal. 2d 711 (1948).

- ^ Anti-miscegenation laws in the United States

- ^ US CODE-TITLE 8-ALIENS AND NATIONALITY

- ^ 112th Congress (2012) (June 8, 2012). "H.Res. 683 (112th)". Legislation. GovTrack.us. Retrieved August 9, 2012.

Expressing the regret of the House of Representatives for the passage of laws that adversely affected the Chinese in the United States, including the Chinese Exclusion Act.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

Further reading

External links

- Chinese Exclusion Act

- Chinese Exclusion Act (1882) - Our Documents

- Exclusion Act Case Files of Yee Wee Thing and Yee Bing Quai, two "Paper Sons"

- The Yung Wing Project hosts the memoir of one of the earliest naturalized Chinese whose citizenship was revoked forty-six years after having received it as a result of the Chinese Exclusion Act.

- An Alleged Wife One Immigrant in the Chinese Exclusion Era

- Collection of primary source documents relating to the Chinese Exclusion Act, from Harvard University.

- Primary source documents and images from the University of California

- The Rocky Road to Liberty: A Documented History of Chinese American Immigration and Exclusion

- " US apologizes for Chinese Exclusion Act" China Daily

- 1882 in law

- Anti-Chinese legislation

- Anti-Chinese sentiment in the United States

- Anti-Chinese sentiment

- Asian-American issues

- Chinese-American history

- History of immigration to the United States

- History of racial segregation in the United States

- United States federal immigration and nationality legislation

- United States repealed legislation

- United States immigration and naturalization case law

- Race legislation in the United States

- 1882 in the United States

- 1882 in international relations