Continuation War

Template:Use Harvard referencing

| Continuation War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Eastern Front of World War II | |||||||||

Finnish soldiers at the defensive VT-line during the Soviet Vyborg–Petrozavodsk Offensive in June 1944 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

450,000–700,000 Finns[Note 3] 67,000–214,000 Germans[Note 4] 2,000 Estonian volunteers 1,000 Swedish volunteers | 450,000–650,000 Soviets[Note 5] | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||

The Continuation War was a conflict fought by Finland and Nazi Germany, as co-belligerents, against the Soviet Union (USSR) from 1941 to 1944, during World War II.[Note 6] In Russian historiography, the war is called the Soviet–Finnish Front of the Great Patriotic War.[Note 7] Germany regarded its operations in the region as part of its overall war efforts on the Eastern Front and provided Finland with critical material support and military assistance.

The Continuation War began 15 months after the end of the Winter War, also fought between Finland and the USSR. There have been a number of reasons proposed for the Finnish decision to invade, with regaining territory lost during the Winter War being regarded as the most common. Other justifications for the conflict included President Ryti's vision of a Greater Finland and Commander-in-Chief Mannerheim's desire to liberate Karelia. Plans for the attack were developed jointly between the Wehrmacht and a small faction of Finnish political and military leaders with the rest of the government remaining ignorant. Despite the co-operation in this conflict, Finland never formally signed the Tripartite Pact that had established the Axis powers and justified its alliance with Germany as self-defense.

In June 1941, with the start of the German invasion of the Soviet Union, the Finnish Defence Forces launched their offensive following Soviet airstrikes. By September 1941, Finland occupied East Karelia and reversed its post-Winter War concessions to the Soviet Union along the Karelian Isthmus and in Ladoga Karelia. The Finnish Army halted its offensive past the old border, around 30–32 km (19–20 mi) from the centre of Leningrad and participated in besieging the city by cutting its northern supply routes and digging in until 1944.[Note 8] In Lapland, joint German–Finnish forces failed to capture Murmansk or cut the Kirov (Murmansk) Railway, a transit route for lend-lease equipment to the USSR. The conflict stabilised with only minor skirmishes until the tide of the war turned against the Germans and the Soviet Union's strategic Vyborg–Petrozavodsk Offensive in June 1944. The attack drove the Finns from most of the territories they had gained during the war, but the Finnish Army managed to halt the offensive in August 1944.

Hostilities between Finland and the USSR ended with a ceasefire, which was called on 5 September, and formalised by the signing of the Moscow Armistice on 19 September. One of the conditions of this agreement was the expulsion, or disarming, of any German troops in Finnish territory, which led to the Lapland War between the former co-belligerents. World War II was concluded formally for Finland and the minor Axis powers with the signing of the Paris Peace Treaties in 1947. The treaties resulted in the restoration of borders per the 1940 Moscow Peace Treaty, the ceding of the municipality of Petsamo (Russian: Pechengsky raion) and the leasing of Porkkala Peninsula to the USSR. Furthermore, Finland was required to pay $300 million in war reparations to the USSR.

63,200 Finns and 23,200 Germans died or went missing during the war in addition to 158,000 and 60,400 wounded, respectively. Estimates of dead or missing Soviets range from 250,000 to 305,000 while 575,000 have been estimated to have been wounded or fallen sick.

Background

Winter War

On 23 August 1939, the Soviet Union (USSR) and Germany signed the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, in which the two parties agreed to divide the independent countries of Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, and Romania into spheres of interest, with Finland falling within the Soviet sphere.[28] Shortly after, Germany invaded Poland leading to the United Kingdom (UK) and France declaring war on Germany. The Soviet Union invaded eastern Poland on 17 September.[29] Moscow turned its attention to the Baltic states, demanding that they allow Soviet military bases to be established and troops stationed on their soil. The Baltic governments acquiesced to these demands and signed agreements in September and October.[30]

In October 1939, the Soviet Union attempted to negotiate with Finland to cede Finnish territory on the Karelian Isthmus and the islands of the Gulf of Finland, and to establish a Soviet military base near the Finnish capital of Helsinki.[31] The Finnish government refused, and the Red Army invaded Finland on 30 November 1939.[32] The USSR was expelled from the League of Nations and condemned by the international community for the illegal attack.[33] Foreign support for Finland was promised, but very little actual help materialised, except from Sweden.[34] The Moscow Peace Treaty concluded the 105-day Winter War on 13 March 1940 and started the Interim Peace.[35] By the terms of the treaty, Finland ceded 11 per cent of its national territory and 13 percent of its economic capacity to the Soviet Union.[36] Some 420,000 evacuees were resettled from the ceded territories.[37] Finland avoided total conquest of the country by the Soviet Union and retained its sovereignty.[38]

Prior to the war, Finnish foreign policy had been based on multilateral guarantees of support from the League of Nations and Nordic countries, but this policy was considered a failure.[39] After the war, Finnish public opinion favored the reconquest of Finnish Karelia. The government declared national defence to be its first priority, and military expenditure rose to nearly half of public spending. Finland purchased and received donations of war materiel during and immediately after the Winter War.[37] Likewise, Finnish leadership wanted to preserve the spirit of unanimity that was felt throughout the country during the Winter War. The divisive White Guard tradition of the Finnish Civil War's 16 May victory-day celebration was therefore discontinued.[40]

The Soviet Union had received the Hanko Naval Base, on Finland's southern coast near the capital Helsinki, where it deployed over 30,000 Soviet military personnel.[37] Relations between Finland and the Soviet Union remained strained after the signing of the one-sided peace treaty, and there were disputes regarding the implementation of the treaty. Finland sought security against further territorial depredations by the USSR and proposed mutual defence agreements with Norway and Sweden, but these initiatives were quashed by Moscow.[41][42]

German and Soviet expansion in Europe

After the Winter War, Germany was viewed with distrust by the Finnish, as it was considered an ally of the Soviet Union. Nonetheless, the Finnish government sought to restore diplomatic relations with Germany, but also continued its Western-oriented policy and negotiated a war trade agreement with the United Kingdom.[41] The agreement was renounced after the German invasion of Denmark and Norway on 9 April 1940 resulted in the UK cutting all trade and traffic communications with the Nordic countries. With the fall of France, a Western orientation was no longer considered a viable option in Finnish foreign policy.[43] On 15 and 16 June, the Soviet Union occupied the Baltic states without resistance and Soviet puppet regimes were installed. Within two months Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania were incorporated into the USSR as Soviet republics and by mid-1940, the two remaining northern democracies, Finland and Sweden, were encircled by the hostile states of Germany and the Soviet Union.[44]

On 23 June, shortly after the Soviet occupation of the Baltic states began, Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov contacted the Finnish government demanding that a mining license be issued to the USSR for the nickel mines in the municipality of Petsamo (Russian: Pechengsky raion) or, alternatively, permit the establishment of a joint Soviet-Finnish company to operate there. A license to mine the deposit had already been granted to a British-Canadian company, and the demand was rejected by Finland. The following month, the Soviets demanded that Finland destroy the fortifications on the Åland islands and grant the USSR the right to use Finnish railways to transport Soviet troops to the newly-acquired Soviet base at Hanko. The Finns very reluctantly agreed to these demands.[45] On 24 July, Molotov accused the Finnish government of persecuting the Finland – Soviet Union Peace and Friendship Society, a pro-communist group, and soon afterwards publicly declared support for the group. The society organised demonstrations in Finland, some of which turned into riots.[46][47]

Russian sources, such as the book Stalin's Missed Chance, maintain that Soviet policies leading up to the Continuation War were best explained as defensive measures by offensive means. The Soviet division of occupied Poland with Germany, the Soviet occupations of Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia, and the Soviet invasion of Finland in the Winter War are described as elements in the Soviet construction of a security zone, or buffer region, against the perceived threat from the capitalist powers of Western Europe. The Russian sources see the post-World War II establishment of Soviet satellite states in the Warsaw Pact countries and the Finno-Soviet Treaty of 1948 as the culmination of the Soviet defence plan.[48][49][50] Western historians, such as Norman Davies and John Lukacs, dispute this view and describe pre-war Soviet policy as an attempt to stay out of the war and regain land lost after the fall of the Russian Empire.[51][52]

Relations between Finland, Germany and the USSR

On 31 July 1940, German Chancellor Adolf Hitler gave the order to start planning an assault on the Soviet Union, meaning Germany had to reassess its position regarding both Finland and Romania. Until then, Germany had rejected Finnish appeals to purchase arms, but with the prospect of an invasion of Russia, this policy was reversed, and in August the secret sale of weapons to Finland was permitted.[53] Military authorities signed an agreement on 12 September, and an official exchange of diplomatic notes was sent on 22 September. At the same time, German troops were allowed to transit through Sweden and Finland.[54] This change in policy meant Germany had effectively redrawn the border of the German and Soviet spheres of influence, violating the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact.[55]

In response to this new situation, Molotov visited Berlin on 12–13 November 1940.[56] He requested that Germany withdraw its troops from Finland and stop enabling Finnish anti-Soviet sentiments. He also reminded the Germans of the 1939 Soviet–German non-aggression pact. Hitler inquired how the USSR planned to settle the "Finnish question", to which Molotov responded that it would mirror the events in Bessarabia and the Baltic states. Hitler rejected this course of action.[57] In December, the Soviet Union, Germany and the UK all voiced opinions concerning suitable Finnish presidential candidates. Risto Ryti was the sole candidate not objected to by any of the three powers and was elected on 19 December.[58]

In January 1941, Moscow demanded Finland relinquish control of the Petsamo mining area to the Soviets, but Finland, emboldened by a rebuilt defence force and German support, rejected the proposition.[58] On 18 December 1940, Hitler officially approved Operation Barbarossa, paving the way for the German invasion of the Soviet Union,[59] in which he expected both Finland and Romania to participate.[60] During this period, Finnish Major General Paavo Talvela met with German Generaloberst Franz Halder and Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring in Berlin. This was the first time the Germans had advised the Finnish government, in carefully couched diplomatic terms, that they were preparing for war with the Soviet Union. Outlines of the actual plan were revealed in January 1941 and regular contact between Finnish and German military leaders began in February.[60]

In the late spring of 1941, the USSR made a number of goodwill gestures to prevent Finland from completely falling under German influence. Ambassador Ivan Zotov was replaced with the more flexible Pavel Orlov. Furthermore, the Soviet government announced that it no longer opposed a rapprochement between Finland and Sweden. These conciliatory measures, however, did not have any effect on Finnish policy.[61] Finland wished to re-enter World War II mainly because of the Soviet invasion of Finland during the Winter War, which had taken place after Finnish intentions of relying on the League of Nations and Nordic neutrality to avoid conflicts had failed from lack of outside support.[62] Finland primarily aimed to reverse its territorial losses from the March 1940 Moscow Peace Treaty and, depending on the success of the German invasion of the Soviet Union, to possibly expand its borders, especially into East Karelia. Some right-wing groups, such as the Academic Karelia Society, supported a Greater Finland ideology.[63]

German and Finnish war plans

The matter of when and why Finland prepared for war is still somewhat opaque. Historian William R. Trotter stated that "it has so far proven impossible to pinpoint the exact date on which Finland was taken into confidence about Operation Barbarossa" and that "neither the Finns nor the Germans were entirely candid with one another as to their national aims and methods. In any case, the step from contingency planning to actual operations, when it came, was little more than a formality."[64]

The inner circle of Finnish leadership, led by Ryti and Mannerheim, actively planned joint operations with Germany under a veil of ambiguous neutrality and without formal agreements, after an alliance with Sweden proved fruitless—according to a meta-analysis by Finnish historian Olli Vehviläinen. He likewise refuted the so-called "driftwood theory" that Finland was merely a piece of driftwood swept uncontrollably in the rapids of great-power politics. Even then, most historians conclude that Finland did not have any realistic alternatives to cooperating with Germany at the time.[65] On 20 May, the Germans invited a number of Finnish officers to discuss the coordination of Operation Barbarossa. The participants met on 25–28 May in Salzburg and Berlin, and continued their meeting in Helsinki from 3 to 6 June. They agreed upon the arrival of German troops, Finnish mobilization, and a general division of operations.[61] They also agreed that the Finnish Army would start mobilization on 15 June, but the Germans did not reveal the actual date of the assault. The Finnish decisions were made by the inner circle of political and military leaders, without the knowledge of the rest of the government, who were not informed until 9 June that mobilization of reservists, due to tensions between Germany and the Soviet Union, would be required.[59][66]

Finland never signed the Tripartite Pact, which had been signed by all de jure Axis powers. The Finnish leadership and Mannerheim, in particular, clearly stated they would fight against the Soviets only to the extent necessary to redress the balance of the 1940 treaty. For Hitler, the distinction was irrelevant as he saw Finland as an ally.[67]

Order of battle and operational planning

Soviet

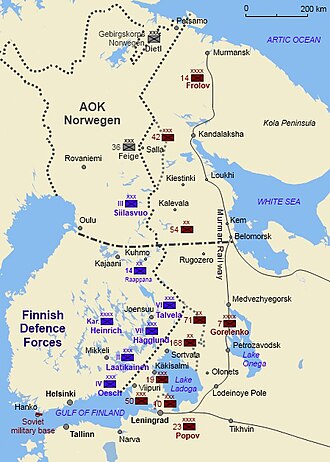

The Northern Front (Russian: Северный фронт) of the Leningrad Military District was commanded by Lieutenant General Markian Popov and numbered around 450,000 soldiers in 18 divisions and 40 independent battalions in the Finnish region.[10] During the Interim Peace, the Soviet Military had relaid operational plans to conquer Finland,[68] but with Operation Barbarossa, the USSR required its best units and latest materiel to be deployed against the Germans, and thus abandoned plans for a renewed offensive against Finland.[18][69] The 23rd Army was deployed in the Karelian Isthmus, the 7th Army to Ladoga Karelia and the 14th Army to the Murmansk–Salla area of Lapland. The Northern Front also commanded 8 aviation divisions.[70] As the initial German strike against the Soviet Air Forces had not affected air units located near Finland, it could deploy around 700 aircraft supported by a number of Soviet Navy wings.[71] The Red Banner Baltic Fleet comprised 2 battleships, 2 light cruisers, 47 destroyers or large torpedo boats, 75 submarines, over 200 smaller craft as well as hundreds of aircraft—and outnumbered the Kriegsmarine.[72]

Finnish and German

The Finnish Army (Template:Lang-fi) mobilised between 475,000 and 500,000 soldiers in 14 divisions and 3 brigades for the invasion, commanded by Field Marshal (sotamarsalkka) Mannerheim. The army was organised as follows:[69][73][74]

- II Corps (II Armeijakunta, II AK) and IV Corps: deployed to the Karelian Isthmus and comprised seven infantry divisions and one brigade.

- Army of Karelia: deployed north of Lake Ladoga and commanded by General Erik Heinrichs. It comprised VI Corps, VII Corps and Group Oinonen; a total of seven divisions, including the German 163rd Infantry Division, and three brigades.

- 14th Division: deployed in the Kainuu region, commanded directly by Finnish Headquarters (Päämaja).

Although initially deployed for a static defence, the Finnish Army was to later launch an attack to the south, on both sides of Lake Ladoga, putting pressure on Leningrad and thus supporting the advance of the German Army Group North.[74] Finnish intelligence had overestimated the strength of the Red Army, when in fact it was numerically inferior to Finnish forces at various points along the border.[69] The army, especially its artillery, was stronger than it had been during the Winter War but included only one armoured battalion and had a general lack of motorised transportation.[75] The Finnish Air Force (Ilmavoimat) had 235 aircraft in July 1941 and 384 by September 1944, despite losses. Even with the increase in aircraft, the air force was constantly outnumbered by the Soviets.[76][77]

The Army of Norway, or AOK Norwegen, comprising four divisions totaling 67,000 German soldiers, held the arctic front, which stretched approximately 500 km (310 mi) through Finnish Lapland. This army would also be tasked with striking Murmansk and the Kirov (Murmansk) Railway during Operation Silver Fox. The Army of Norway was under the direct command of the Oberkommando des Heeres (OKH) and was organised into Mountain Corps Norway and XXXVI Mountain Corps with the Finnish Finnish III Corps and 14th Division attached to it.[78][74][75] The Oberkommando der Luftwaffe (OKL) assigned 60 aircraft from Luftflotte 5 (Air Fleet 5) to provide air support to the Army of Norway and the Finnish Army, in addition to its main responsibility of defending Norwegian air space.[79][80] In contrast to the front in Finland, a total of 149 divisions and 3,050,000 soldiers were deployed for the rest of Operation Barbarossa.[81]

Finnish offensive phase in 1941

Initial operations

In the evening of 21 June 1941, German minelayers hiding in the Archipelago Sea deployed two large minefields across the Gulf of Finland. Later that night, German bombers flew along the gulf to Leningrad, mining the harbour and the river Neva, making a refueling stop at Utti, Finland, on the return leg. In the early hours of 22 June, Finnish forces launched Operation Kilpapurjehdus ("Regatta"), deploying troops in the demilitarised Åland Islands. Although the 1921 Åland convention had clauses allowing Finland to defend the islands in the event of an attack, the coordination of this operation with the German invasion and the arrest of the Soviet consulate staff stationed on the islands, meant that the deployment was a deliberate violation of the treaty, according to Finnish historian Mauno Jokipii.[82]

Following the launch of Operation Barbarossa at around 3:15 a.m. on 22 June 1941, the Soviet Union sent 7 bombers on a retaliatory airstrike into Finland, hitting targets at 6:06 a.m. Helsinki time as reported by the Finnish coastal defence ship Väinämöinen.[83] On the morning of 25 June, the Soviet Union launched another air offensive, with 460 fighters and bombers targeting 19 airfields in Finland, however inaccurate intelligence and poor bombing accuracy resulted in several raids hitting Finnish cities, or municipalities, causing considerable damage. 23 Soviet bombers were lost in this strike while the Finnish forces did not lose aircraft.[84][85][66] Although the USSR claimed that the airstrikes were directed against German targets, particularly airfields, in Finland,[86] the Finnish government used the attacks as justification for the approval of a "defensive war".[87] According to historian David Kirby, the message was intended more for public opinion in Finland than abroad, where the country was viewed as an ally of the Axis powers.[88][65]

Finnish advance in Karelia

The Finnish plans for the offensive in Ladoga Karelia were finalised on 28 June,[89] and the first stages of the operation began on 10 July.[89][90][66] By 16 July, VI Corps had reached the northern shore of Lake Ladoga, dividing the Soviet 7th Army, which had been tasked with defending the area.[89] The USSR struggled to contain the German assault, and soon the Soviet high command, Stavka, pulled all available units stationed along the Finnish border into the beleaguered front line.[89] Additional reinforcements were drawn from the 237th Rifle Division and the Soviet 10th Mechanised Corps, excluding the 198th Motorised Division, both of which were stationed in Ladoga Karelia, but this stripped much of the reserve strength of the Soviet units defending that area.[91]

The Finnish II Corps started its offensive in the north of the Karelian Isthmus on 31 July.[92] Other Finnish forces reached the shores of Lake Ladoga on 9 August, encircling most of the three defending Soviet divisions on the northwestern coast of the lake in a pocket (motti in Finnish); these divisions were later evacuated across the lake. On 22 August, the Finnish IV Corps began its offensive south of II Corps and advanced towards Vyborg (Template:Lang-fi).[92] By 23 August, II Corps had reached the Vuoksi River to the east and encircled the Soviet forces defending Vyborg.[92]

The Soviet order to withdraw came too late, resulting in significant losses in materiel, although most of the troops were later evacuated via the Koivisto Islands. After suffering severe losses, the Soviet 23rd Army was unable to halt the offensive, and by 2 September the Finnish Army had reached the old 1939 border. The advance by Finnish and German forces split the Soviet Northern Front into the Leningrad Front and the Karelian Front. On 31 August, Finnish Headquarters ordered II and IV Corps, which had advanced the furthest, to halt their advance along a line that ran from the Gulf of Finland via Beloostrov– Sestra River– Okhta River–Lembolovo to Ladoga. The line ran past the former 1939 border, and approximately 30–32 km (19–20 mi) from Leningrad. There, they were ordered to take up a defensive position.[Note 9] On 1 September, the IV Corps engaged and defeated the Soviet 23rd Army near the town of Porlampi. Sporadic fighting continued around Beloostrov until the Soviets evicted the Finns on 20 September. The front on the Isthmus stabilised and the Siege of Leningrad began.[Note 10]

The Finnish Army of Karelia started its attack in East Karelia towards Petrozavodsk, Lake Onega and the Svir River on 9 September. German Army Group North advanced from the south of Leningrad towards the Svir River and captured Tikhvin but were forced to retreat to the Volkhov River by Soviet counterattacks. Soviet forces repeatedly attempted to expel the Finns from their bridgehead south of the Svir during October and December but were repulsed; Soviet units attacked the German 163rd Infantry Division in October 1941, which was operating under Finnish command across the Svir, but failed to dislodge it.[98] Despite these failed attacks, the Finnish attack in East Karelia had been blunted and their advance had halted by 6 December. During the five-month campaign, the Finns suffered 75,000 casualties, of whom 26,355 had died, while the Soviets had 230,000 casualties, of whom 50,000 became prisoners of war.[99]

Operation Silver Fox in Lapland and Lend-Lease to Murmansk

The German objective in Finnish Lapland was to take Murmansk and cut the Kirov (Murmansk) Railway running from Murmansk to Leningrad by capturing Salla and Kandalaksha. Murmansk was the only year-round ice-free port in the north and a threat to the nickel mine at Petsamo. The joint Finnish–German Operation Silver Fox (German: Unternehmen Silberfuchs; Template:Lang-fi) was started on 29 June 1941 by the German Army of Norway, which had the Finnish 3rd and 6th Divisions under its command, against the defending Soviet 14th Army and 54th Rifle Division. By November, the operation had stalled 30 km (19 mi) from the Kirov Railway due to unacclimatised German troops, heavy Soviet resistance, poor terrain, arctic weather and diplomatic pressure by the United States on the Finns regarding the lend-lease deliveries to Murmansk. The offensive and its three sub-operations failed to achieve their objectives. Both sides dug in and the arctic theatre remained stable, excluding minor skirmishes, until the Soviet Petsamo–Kirkenes Offensive in October 1944.[100][101]

The crucial arctic lend-lease convoys from the US and the UK via Murmansk and Kirov Railway to the bulk of the Soviet forces continued throughout World War II. The US supplied almost $11 billion in materials: 400,000 jeeps and trucks; 12,000 armored vehicles (including 7,000 tanks, which could equip some 20 US armoured divisions); 11,400 aircraft; and 1.59 million t (1.75 million short tons) of food.[102][103] As a similar example, British shipments of Matilda, Valentine and Tetrarch tanks accounted for only 6 percent of total Soviet tank production but over 25 percent of medium and heavy tanks produced for the Red Army.[104]

Aspirations, war effort and international relations

The Wehrmacht rapidly advanced deep into Soviet territory early in the Operation Barbarossa campaign, leading the Finnish government to believe that Germany would defeat the Soviet Union quickly.[66] President Ryti envisioned a Greater Finland, where Finland and other Finnic people would live inside a "natural defence borderline" by incorporating the Kola Peninsula, East Karelia and perhaps even northern Ingria. In public, the proposed frontier was introduced with the slogan "short border, long peace".[105][66][65] Some members of the Finnish Parliament, such as the Social Democratic Party and the Swedish People's Party, opposed the idea, arguing that maintaining the 1939 frontier would be enough.[105] Finnish Commander-in-Chief, Field Marshal C. G. E. Mannerheim, often called the war an anti-Communist crusade, hoping to defeat "Bolshevism once and for all".[66] On 10 July, Mannerheim drafted his order of the day, the Sword Scabbard Declaration, in which he pledged to liberate Karelia; in December 1941 in private letters, he made known his doubts of the need to push beyond the previous borders.[2] The Finnish government assured the United States that it was unaware of the order.[106]

According to Vehviläinen, most Finns thought that the scope of the new offensive was only to regain what had been taken in the Winter War. He further stated that the term 'Continuation War' was created at the start of the conflict by the Finnish government to justify the invasion to the population as a continuation of the defensive Winter War. The government also wished to emphasise that it was not an official ally of Germany, but a 'co-belligerent' fighting against a common enemy and with purely Finnish aims. Vehviläinen wrote that the authenticity of the government's claim changed when the Finnish Army crossed the old frontier of 1939 and began to annex Soviet territory.[107] British author Jonathan Clements asserted that by December 1941, Finnish soldiers had started questioning whether they were fighting a war of national defence or foreign conquest.[108]

By the autumn of 1941, the Finnish military leadership started to doubt Germany's capability to finish the war quickly. The Finnish Defence Forces suffered relatively severe losses during their advance, and, overall, German victory became uncertain as German troops were halted near Moscow. German troops in northern Finland faced circumstances they were unprepared for and failed to reach their targets. As the front lines stabilised, Finland attempted to start peace negotiations with the USSR.[109] Mannerheim refused to assault Leningrad and tie Finland to its German allies inextricably, regarding his objectives for the war to be achieved, a decision which angered the Germans.[2]

Due to the war effort, the Finnish economy suffered from a lack of labour, as well as food shortages and increased prices. To combat this, the Finnish government demobilised part of the army to prevent industrial and agricultural production from collapsing.[99] In October, Finland informed Germany that it would need 159,000 t (175,000 short tons) of grain to manage until next year's harvest. The German authorities would have rejected the request, but Hitler himself agreed. Annual grain deliveries of 180,000 t (200,000 short tons) equaled almost half of the Finnish domestic crop. In November, Finland joined the Anti-Comintern Pact.[110]

Finland maintained good relations with a number of other Western powers. Foreign volunteers from Sweden and Estonia were among the foreigners who joined Finnish ranks; Infantry Regiment 200, called soomepoisid ("Finnish boys"), mostly comprised Estonians, while the Swedes mustered the Swedish Volunteer Battalion.[111] The Finnish government stressed that Finland was fighting as a co-belligerent with Germany against the USSR only to protect itself and that it was still the same democratic country as it had been in the Winter War.[99] For example, Finland maintained diplomatic relations with the exiled Norwegian government and more than once criticised German occupation policy in Norway.[112] Relations between Finland and the United States were more complex; the US public was sympathetic to the "brave little democracy" and had anti-communist sentiments. At first, the United States sympathised with the Finnish cause, but the situation became problematic after the Finnish Army crossed the 1939 border.[113] Finnish and German troops were a threat to the Kirov Railway and the northern supply line between the Western Allies and the Soviet Union.[113] On 25 October 1941, the US demanded that Finland cease all hostilities against the USSR and withdraw behind the 1939 border. In public, President Ryti rejected the demands, but in private, he wrote to Mannerheim on 5 November asking him to halt the offensive. Mannerheim agreed and secretly instructed General Hjalmar Siilasvuo and his III Corps to end the assault on the Kirov Railway.[114]

British declaration of war and action in the Arctic Ocean

On 12 July 1941, the United Kingdom signed an agreement of joint action with the Soviet Union. Under German pressure, Finland closed the British legation in Helsinki, cutting diplomatic relations with the UK on 1 August.[115] The most sizeable British action on Finnish soil was the Raid on Kirkenes and Petsamo, an aircraft-carrier strike on German and Finnish ships on 31 July 1941. The attack achieved little, except the loss of one Norwegian ship and three British aircraft, but it was intended to demonstrate British support for its Soviet ally.[3] From September to October in 1941, a total of 39 Hawker Hurricanes of No. 151 Wing RAF, based at Murmansk, reinforced and provided pilot-training to the Soviet Air Forces during Operation Benedict to protect arctic convoys.[4] On 28 November, the UK presented Finland an ultimatum demanding that the Finns cease military operations by 3 December.[114] Unofficially, Finland informed the Western powers that Finnish troops would halt their advance in the next few days. The reply did not satisfy the United Kingdom, which declared war on Finland on 6 December.[66][Note 11] The Commonwealth nations of Canada, Australia, the British Raj and New Zealand soon followed suit.[117] In private, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill had sent a letter to Mannerheim on 29 November, in which he was "deeply grieved" that the UK would have to declare war on Finland because of the UK's alliance with the USSR. Mannerheim returned British volunteers under his command to the United Kingdom via Sweden. According to Clements, the war was mostly for appearances' sake.[118]

Trench warfare phase during 1942–43

Unconventional warfare and military operations

Unconventional warfare was fought in both the Finnish and Soviet wildernesses. Finnish long-range reconnaissance patrols, organised both by the Intelligence Division's Detached Battalion 4 and by local units, patrolled behind Soviet lines. Soviet partisans, both resistance fighters and regular long-range patrol detachments, conducted a number of operations in Finland and in Eastern Karelia from 1941 to 1944. In summer 1942, the USSR formed the 1st Partisan Brigade. The unit was 'partisan' in name only, as it was essentially 600 men and women on long-range patrol intended to disrupt Finnish operations. The 1st Partisan Brigade was able to infiltrate beyond Finnish patrol lines, but was intercepted, and rendered ineffective, in August 1942 at Lake Segozero.[119] Irregular partisans distributed propaganda newspapers, such as Finnish translations of the official Communist Party paper Pravda (Russian: Правда). Notable Soviet politician, Yuri Andropov, took part in these partisan guerrilla actions.[120] Finnish sources state that, although Soviet partisan activity in East Karelia disrupted Finnish military supply and communication assets, almost two thirds of the attacks targeted civilians, killing 200 and injuring 50, including children and elderly.[121][122][123][124]

Between 1942 and 1943, military operations were limited, although the front did see some action. In January 1942, the Soviet Karelian Front attempted to retake Medvezhyegorsk (Template:Lang-fi), which had been lost to the Finns in late 1941. With the arrival of spring in April, Soviet forces went on the offensive on the Svir River front, in the Kestenga (Kiestinki) region further north in Lapland as well as in the far north at Petsamo with the 14th Rifle Division's amphibious landings supported by the Northern Fleet. All Soviet offensives started promisingly, but due either to the Soviets overextending their lines or stubborn defensive resistance, the offensives were repulsed. After Finnish and German counterattacks in Kestenga, the front lines were generally stalemated. In September 1942, the USSR attacked again at Medvezhyegorsk, but despite five days of fighting, the Soviets only managed to push the Finnish lines back 500 m (550 yd) on a roughly 1 km (0.62 mi)-long stretch of the front. Later that month, a Soviet landing with two battalions in Petsamo was defeated by a German counterattack.[125][126] In November 1941, Hitler decided to separate the German forces fighting in Lapland from the Army of Norway and create the Army of Lapland, commanded by Generaloberst Eduard Dietl through AOK Lappland. In June 1942, the Army of Lapland was redesignated the 20th Mountain Army.[127]

Siege of Leningrad and naval warfare

In the early stages of the war, the Finnish Army overran the former 1939 border, but ceased their advance 30–32 km (19–20 mi) from the center of Leningrad. Multiple authors have stated that Finland participated in the Siege of Leningrad (Russian: Блокада Ленинграда), but the full extent and nature of their participation is debated and a clear consensus has yet to emerge.[Note 12] American historian David Glantz, writes that the Finnish Army generally maintained their lines and contributed little to the siege from 1941 to 1944,[128] whereas Russian historian Nikolai Baryshnikov stated in 2002 that Finland tacitly supported Hitler's starvation policy for the city.[23] However, in 2009 British historian Michael Jones refuted Baryshnikov's claim and asserted that the Finnish Army cut off the city's northern supply routes but did not take further military action.[21] In 2006, American author Lisa A. Kirchenbaum wrote that the siege started "when German and Finnish troops severed all land routes in and out of Leningrad."[129]

According to Clements, Mannerheim personally refused Hitler's request of assaulting Leningrad during their meeting on 4 June 1942. Mannerheim explained to Hitler that "Finland had every reason to wish to stay out of any further provocation of the Soviet Union."[131] In 2014, author Jeff Rutherford described the city as being "ensnared" between the German and Finnish armies.[26] British historian John Barber described it as a "siege by the German and Finnish armies from 8 September 1941 to 27 January 1944 [...]" in his foreword in 2017.[27] Likewise, in 2017, Alexis Peri wrote that the city was "completely cut off, save a heavily patrolled water passage over Lake Ladoga" by "Hitler's Army Group North and his Finnish allies."[132]

The 150 speedboats, 2 minelayers and 4 steamships of the Finnish Ladoga Naval Detachment, as well as numerous shore batteries, had been stationed on Lake Ladoga since August 1941. Finnish Lieutenant General Paavo Talvela proposed on 17 May 1942 to create a joint Finnish–German–Italian unit on the lake to disrupt Soviet supply convoys to Leningrad. The unit was named Naval Detachment K and comprised four Italian MAS torpedo motorboats of the XII Squadriglia MAS, four German KM-type minelayers and the Finnish torpedo-motorboat Sisu. The detachment began operations on August 1942 and sank numerous smaller Soviet watercraft and flatboats and assaulted enemy bases and beach fronts until it was dissolved in the winter of 1942–43.[1] Twenty-three Siebel ferries and nine infantry transports of the German Einsatzstab Fähre Ost were also deployed to Lake Ladoga and unsuccessfully assaulted the island of Sukho, which protected the main supply route to Leningrad, on October 1942.[133]

Despite the siege of the city, the Soviet Baltic Fleet was still able to operate from Leningrad. The Finnish Navy's flagship Ilmarinen had been sunk in September 1941 in the gulf by mines during the failed diversionary Operation Nordwind.[134] In early 1942, Soviet forces recaptured the island of Gogland, but lost it and the Bolshoy Tyuters islands to Finnish forces later in spring 1942. During the winter between 1941 and 1942, the Soviet Baltic Fleet decided to use their large submarine fleet in offensive operations. Though initial submarine operations in the summer of 1942 were successful, the Kriegsmarine and Finnish Navy soon intensified their anti-submarine efforts, making Soviet submarine operations later in 1942 costly. The underwater offensive carried out by the Soviets convinced the Germans to lay anti-submarine nets as well as supporting minefields between Porkkala Peninsula and Naissaar, which proved to be an insurmountable obstacle for Soviet submarines.[135] On the Arctic Ocean, Finnish radio intelligence intercepted Allied messages on supply convoys to Murmansk, such as PQ-17 and PQ-18, and relayed the information to the Abwehr, German intelligence.[136]

Finnish military administration and concentration camps

On 19 July 1941, the Finns created a military administration in occupied East Karelia with the goal of preparing the region for eventual incorporation into Finland. The Finns aimed to expel the local Russian population, who were deemed "non-national",[137] from the area once the war was over,[138] and replace them with Finnic peoples, such as Karelians, Finns, Estonians, Ingrians and Vepsians. Most of the East Karelian population had already been evacuated before the Finnish forces arrived, but about 85,000 people — mostly elderly, women and children — were left behind, less than half of whom were Karelians. A significant number of civilians, almost 30 percent of the remaining Russians, were interned in concentration camps.[137]

The winter between 1941 and 1942 was particularly harsh for the Finnish urban population due to poor harvests and a shortage of agricultural labourers.[137] However, conditions were much worse for Russians in Finnish concentration camps. More than 3,500 people died, mostly from starvation, amounting to 13.8 per cent of those detained, while the corresponding figure for the free population of the occupied territories was 2.6 per cent, and 1.4 per cent for Finland.[139] Conditions gradually improved, ethnic discrimination in wage levels and food rations was terminated, and new schools were established for the Russian-speaking population the following year, after Commander-in-Chief Mannerheim called for the International Committee of the Red Cross from Geneva to inspect the camps.[140][141] By the end of the occupation, mortality rates had dropped to the same levels as in Finland.[139]

Jews in Finland

Finland had a small Jewish population of approximately 2,300 people, of whom 300 were refugees. They had full civil rights and fought with other Finns in the ranks of the Finnish Army. The field synagogue in East Karelia was one of the very few functioning synagogues on the Axis side during the war. There were several cases of Jewish officers of the Finnish Army being awarded the German Iron Cross, which they declined. German soldiers were treated by Jewish medical officers—who sometimes saved the soldiers' lives.[142][143] German command mentioned Finnish Jews at the Wannsee Conference in January 1942, wishing to transport them to the Majdanek concentration camp in occupied Poland. SS leader Heinrich Himmler also raised the topic of Finnish Jews during his visit in Finland in the summer of 1942; Finnish Prime Minister Jukka Rangell replied that Finland did not have a Jewish question.[67] In November 1942, the Minister of Interior Toivo Horelli and the head of State Police Arno Anthoni deported eight Jewish refugees to the Gestapo in secret, raising protests among Finnish Social Democrat Party ministers. Only one of the deportees survived. After the incident, the Finnish government refused to transfer any more Jews to German detainment.[144][145]

Soviet offensive phase in 1944

Air raids and the Leningrad–Novgorod Offensive

Finland began to seek an exit from the war after the German defeat at the Battle of Stalingrad in February 1943. Prime Minister Edwin Linkomies formed a new cabinet in March 1943 with peace as the top priority. Similarly, the Finns were distressed by the Allied Invasion of Sicily in July and the German defeat in the Battle of Kursk in August. Negotiations were conducted intermittently during 1943–1944 between Finland, the Western Allies and the USSR, but no agreement was reached.[146] Stalin decided to force Finland to surrender with a bombing campaign on Helsinki, starting in February 1944. It included three major air attacks totaling over 6,000 sorties. Finnish anti-aircraft defence repelled the raids and only five per cent of the dropped bombs hit their planned targets. In Helsinki, decoy searchlights and fires were placed outside the city to deceive Soviet bombers into dropping their payloads on unpopulated areas. Major air attacks also hit Oulu and Kotka, but pre-emptive radio intelligence and effective defence kept the number of casualties low.[147]

The Soviet Leningrad–Novgorod Offensive finally lifted the Siege of Leningrad on 26–27 January 1944[27] and pushed Army Group North to Ida-Viru County on the Estonian border. Stiff German and Estonian defence in Narva from February to August prevented the use of occupied Estonia as a favourable base for Soviet amphibious and air assaults against Helsinki and other Finnish coastal cities in support of a land offensive.[148][149][150] Field Marshal Mannerheim had reminded the German command on numerous occasions that should German troops withdraw from Estonia, Finland would be forced to make peace, even on extremely unfavourable terms.[151] Finland would abandon peace negotiations in April 1944 due to the unfavourable terms the USSR demanded.[152][153]

Vyborg–Petrozavodsk Offensive and breakthrough

On 9 June 1944, the Soviet Leningrad Front launched an offensive against Finnish positions on the Karelian Isthmus and in the area of Lake Ladoga, timed to coincide with Operation Overlord in Normandy as agreed during the Tehran Conference.[109] The main objective of the offensive was to force Finland out of the war. Along the 21.7 km (13.5 mi)-wide breakthrough, the Red Army concentrated 3,000 guns and mortars. In some places, the concentration of artillery pieces exceeded 200 guns for every kilometre of front or one for every 5 m (5.5 yd). Soviet artillery fired over 80,000 rounds along the front on the Karelian Isthmus. On the second day of the offensive, the artillery barrages and superior number of Soviet forces crushed the main Finnish defence line. The Red Army penetrated the second line of defence, the Vammelsuu–Taipale line (VT line), by the sixth day and recaptured Vyborg almost without resistance on 20 June. The Soviet breakthrough on the Karelian Isthmus forced the Finns to reinforce the area, thus allowing the concurrent Soviet offensive in East Karelia to meet less resistance and to recapture Petrozavodsk by 28 June 1944.[154][155][156]

On 25 June, the Red Army reached the third line of defence, the Viipuri–Kuparsaari–Taipale line (VKT line), and the decisive Battle of Tali-Ihantala began, which has been described as the largest battle in Nordic military history.[157] By this point, the Finnish Army had retreated around 100 km (62 mi) to approximately the same line of defence they had held at the end of the Winter War. Finland especially lacked modern anti-tank weaponry that could stop Soviet heavy armour, such as the KV-1 or IS-2. Thus, German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop offered German hand-held Panzerfaust and Panzerschreck antitank weapons in exchange for a guarantee that Finland would not seek a separate peace with the USSR. On 26 June, President Risto Ryti gave the guarantee as a personal undertaking, which he, Field Marshal Mannerheim and Prime Minister Edwin Linkomies intended to legally last only for the remainder of Ryti's presidency. In addition to delivering thousands of anti-tank weapons, Hitler sent the 122nd Infantry Division and the half-strength 303rd Assault Gun Brigade armed with Sturmgeschütz III tank destroyers as well as the Luftwaffe's Detachment Kuhlmey to provide temporary support in the most vulnerable sectors.[158] With the new supplies and assistance from Germany, the Finnish Army halted the numerically and materially superior Soviet advance at Tali-Ihantala on 9 July 1944 and stabilised the front.[159][160][161]

More battles were fought toward the end of the war, the last of which was the Battle of Ilomantsi, fought between 26 July and 13 August 1944 and resulting in a Finnish victory with the destruction of two Soviet divisions.[153][162][163] Resisting the Soviet offensive had exhausted Finnish resources. Despite German support under the Ryti-Ribbentrop Agreement, it was asserted that the country was unable to blunt another major offensive.[164] Soviet victories against German Army Groups Center and North during Operation Bagration made the situation even more dire for Finland.[164] With no imminent further Soviet offensives, Finland sought to leave the war.[164][165][166] On 1 August, President Ryti resigned and on 4 August, Field Marshal Mannerheim was sworn in as the new president. He annulled the agreement between Ryti and Ribbentrop on 17 August, thus allowing Finland to again sue for peace with the USSR; peace terms from Moscow arrived on 29 August.[155][165][167][168]

Ceasefire and peace

Finland was required to return to the borders agreed to in the 1940 Moscow Peace Treaty, demobilise its armed forces, fulfill war reparations and cede the municipality of Petsamo. The Finns were also required to immediately end any diplomatic relations with Germany and expel the Wehrmacht from Finnish territory by 15 September 1944; any troops remaining were to be disarmed, arrested and turned over to the Allies. The Parliament of Finland accepted the terms in a secret meeting on 2 September and requested that official negotiations for an armistice begin. The Finnish Army implemented a ceasefire at 8:00 a.m. Helsinki time on 4 September; the Red Army followed suit a day later. On 14 September, a delegation led by Finnish Prime Minister Antti Hackzell and Foreign Minister Carl Enckell began negotiating, with the USSR and the United Kingdom, the final terms of the Moscow Armistice, which eventually included additional stipulations from the Soviets. They were presented by Molotov on 18 September and accepted by the Finnish Parliament a day later.[169][168]

The motivations for the Soviet peace agreement with Finland are debated. Several Western historians stated that the original Soviet designs for Finland were no different from their designs for the Baltic countries. American political scientist Dan Reiter asserted that for Moscow, the control of Finland was necessary. Reiter and British historian Victor Rothwell both quoted Molotov telling his Lithuanian counterpart in 1940, when the USSR effectively annexed Lithuania, that minor states such as Finland, "will be included within the honourable family of Soviet peoples."[170][171] Reiter stated that concern over severe losses pushed Stalin into accepting a limited outcome in the war rather than pursuing annexation, although some Soviet documents called for military occupation of Finland. He also wrote that Stalin had described territorial concessions, reparations and military bases as his objective with Finland to representatives from the UK, in December 1941, and the US, in March 1943, as well as the Tehran Conference. He believed that in the end "Stalin's desire to crush Hitler quickly and decisively without distraction from the Finnish sideshow" concluded the war.[172]

Russian historian Nikolai Baryshnikov disputed the view that the Soviet Union sought to deprive Finland of its independence. He argued that there is no documentary evidence for such claims and that the Soviet government was always open for negotiations. Baryshnikov cited, for example, the then-public-information chief of Finnish Headquarters, Major Kalle Lehmus, to show that Finnish leadership had learned of the limited Soviet plans for Finland by at least July 1944 after intelligence revealed that some Soviet divisions were to be transferred to reserve in Leningrad.[173] Finnish historian Heikki Ylikangas stated similar findings in 2009. According to him, the USSR refocused its efforts in the summer of 1944, from the Finnish front to defeating Germany and that Mannerheim received intelligence from Colonel Aladár Paasonen in June 1944 that the Soviet Union was aiming for peace, not occupation.[174]

Aftermath and casualties

Finland and Germany

According to Finnish historians, the casualties of the Finnish Defence Forces amounted to 63,204 dead or missing and around 158,000 wounded.[12][13][Note 13] Officially, the Soviets captured 2,377 Finnish POWs, although Finnish researchers estimated the number to be around 3,500 prisoners.[14] 939 Finnish civilians died in air raids and 190 civilians were killed by Soviet partisans.[124][122][175][13] Germany suffered approximately 84,000 casualties in the Finnish front, 16,400 killed, 60,400 wounded and 6,800 missing.[13] In addition to the original peace terms of restoring the 1940 border, Finland was required to pay war reparations to the USSR, conduct domestic war-responsibility trials, lease Porkkala Peninsula to the Soviets as well as ban fascist elements and allow left-wing groups, such as the Communist Party of Finland.[169] A Soviet-led Allied Control Commission was installed to enforce and monitor the peace agreement in Finland.[5] The requirement to disarm or expel any German troops left on Finnish soil by 15 September 1944 eventually escalated into the Lapland War between Finland and Germany and the evacuation of the 200,000-strong 20th Mountain Army to Norway.[176]

The Soviet demand for $600 million in war indemnities was reduced to $300 million (equivalent to $6.5 billion in 2023), most likely due to pressure from the US and the UK. After the ceasefire, the USSR insisted that the payments should be based on 1938 prices, which doubled the de facto amount.[177][169] The temporary Moscow Armistice was finalised without changes later in the Paris Peace Treaties, 1947.[178] Henrik Lunde noted that Finland survived World War II without losing its independence—unlike many of Germany's allies.[179] Likewise, Helsinki, along with Moscow, was the only capital of a World War II combatant nation that was not occupied in continental Europe.[13] In the longer term, Peter Provis analysed that by following self-censorship and limited appeasement policies as well as by fulfilling the USSR's demands, Finland avoided the fate of other nations that were annexed by the Soviets.[180]

Many civilians who had been displaced after the Winter War had moved back into Karelia during the Continuation War and now had to be evacuated from Karelia again. Of the 260,000 civilians who had moved back into the Karelia, only 19 chose to remain and become Soviet citizens.[181] Most of the Ingrian Finns together with Votes and Izhorians living in German-occupied Ingria had been evacuated to Finland in 1943–1944. After the armistice, Finland was forced to return the evacuees.[182] Soviet authorities did not allow the 55,733 returnees to resettle in Ingria and instead deported the Ingrian Finns to central regions of the USSR.[182][183]

Soviet Union

The war is considered a Soviet victory.[5][6][7] According to Finnish historians, Soviet casualties in the Continuation War were not accurately recorded and various approximations have arisen.[12][13] Russian historian Grigori Krivosheev estimated in 1997 that around 250,000 were killed or missing in action while 575,000 were medical casualties (385,000 wounded and 190,000 sick).[10][12] Finnish author Nenye and others stated in 2016 that at least 305,000 were confirmed dead, or missing, according to the latest research and the number of wounded certainly exceeded 500,000.[13] The number of Soviet prisoners of war in Finland was estimated by Finnish historians to be around 64,000, 56,000 of whom were captured in 1941.[15] Around 2,600 to 2,800 Soviet prisoners of war were rendered to Germany in exchange for roughly 2,200 Finnic prisoners of war.[184] Of the Soviet prisoners, at least 18,318 were documented to have died in Finnish prisoner of war camps.[185] The extent of Finland's participation in the Siege of Leningrad, and whether Soviet civilian casualties during the siege should be attributed to the Continuation War, is debated and is without a clear consensus (estimates of civilian deaths during the siege range from 632,253[186] to 1,042,000).[128][27]

See also

Notes

- ^ Italian participation was limited to the four motor torpedo boats of the XII Squadriglia MAS serving in the international Naval Detachment K on Lake Ladoga during the summer and autumn of 1942.[1]

- ^ The United Kingdom formally declared war on Finland on 6 December 1941 along with four Commonwealth states largely for appearances sake.[2] Before that, the British conducted a carrier raid at Petsamo on 31 July 1941[3] and commenced Operation Benedict to support air raids in the Murmansk area and train Soviet crews for roughly a month from September to October in 1941.[4]

- ^ The average strength of the army was around 450,000 soldiers while the estimated peak of the mobilised troops was 700,000.[8]

- ^ In northern Finland, around 67,000 at the start of the war and 214,000 at the end.[9]

- ^ In June 1941, around 450,390 soldiers.[10] In June 1944, 650,000 soldiers.[11]

- ^ Template:Lang-fi; Template:Lang-sv; German: Fortsetzungskrieg. According to Finnish historian Olli Vehviläinen, the term 'Continuation War' was created at the start of the conflict by the Finnish government, to justify the invasion to the population as a continuation of the defensive Winter War and separate from the German war effort. He titled the chapter addressing the issue in his book as "Finland's War of Retaliation". Vehviläinen asserted that the reality of this claim changed when the Finnish forces crossed the 1939 frontier and started annexation operations.[18] The US Library of Congress catalogue also lists the variants War of Retribution and War of Continuation (see authority control).

- ^ Russian: Советско-финский фронт Великой Отечественной войны. Alternatively the Soviet–Finnish War 1941–1944 (Russian: Советско–финская война 1941–1944).[19]

- ^ See the relevant section and the following sources: [20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27]

- ^ See the following sources: [93][21][94][95][25]

- ^ See the following sources: [20][22][96][24][97][27][21]

- ^ Secondary sources contradict each other and state either 5 or 6 December as the day war was declared. According to a news piece on 8 December 1941 by The Examiner, an Australian newspaper, the UK notified the Finnish Government on 6 December "that she considered herself at war with [Finland] as from 1 a.m. (G.M.T.) to-morrow."[116]

- ^ See the following sources: [93][21][94][95][25][21]

- ^ A detailed list of Finnish dead is as follows:[175]

- Dead, buried 33,565;

- Wounded, died of wounds 12,820;

- Dead, not buried, declared as dead 4,251;

- Missing, declared as dead 3,552;

- Died as prisoners of war 473;

- Other reasons (diseases, accidents, suicides) 7,932;

- Unknown 611.

References

Citations

- ^ a b Zapotoczny Jr., Walter S. (2017). Decima Flottiglia MAS: The Best Commandos of the Second World War. Fonthill Media. p. 123. ISBN 9781625451132. Archived from the original on 21 February 2018.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Clements 2012, p. 210.

- ^ a b Sturtivant, Ray (1990). British Naval Aviation: The Fleet Air Arm 1917–1990. London: Arms & Armour Press Ltd. p. 86. ISBN 0-85368-938-5.

- ^ a b Carter, Eric; Loveless, Anthony (2014). Force Benedict. Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 9781444785135. Archived from the original on 21 February 2018.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Mouritzen, Hans (1997). External Danger and Democracy: Old Nordic Lessons and New European Challenges. Dartmouth. p. 35. ISBN 1855218852. Archived from the original on 22 February 2018.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - ^ a b Nordstrom, Byron J. (2000). Scandinavia Since 1500. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. p. 316. ISBN 978-0816620982. Archived from the original on 22 February 2018.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help). - ^ a b Morgan, Kevin; Cohen, Gidon; Flinn, Andrew (2005). Agents of the Revolution: New Biographical Approaches to the History of International Communism in the Age of Lenin and Stalin. Peter Lang. p. 246. ISBN 978-3-03910-075-0. Archived from the original on 2 March 2018.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Kinnunen & Kivimäki 2011, p. 173.

- ^ Ziemke 2002, pp. 9, 391–393.

- ^ a b c d e Krivosheev, Grigori F. (1997). Soviet Casualties and Combat Losses in the Twentieth Century. Greenhill Books. pp. 79, 269–271. ISBN 9781853672804. Archived from the original on 22 February 2018.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Manninen 1994, p. 277–282.

- ^ a b c d e f g Kinnunen & Kivimäki 2011, p. 172.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Nenye et al. 2016, p. 320.

- ^ a b Malmi, Timo (2005). "Jatkosodan suomalaiset sotavangit". In Leskinen, Jari; Juutilainen, Antti (eds.). Jatkosodan pikkujättiläinen (in Finnish) (1st ed.). Werner Söderström Osakeyhtiö. pp. 1022–1032. ISBN 9510286907.

- ^ a b Leskinen & Juutilainen 2005, p. 1036.

- ^ Philip Jowett & Brent Snodgrass p. 14

- ^ Koskimaa, Matti, Veitsenterällä, 1993, ISBN 9510188115, WSOY

- ^ a b Vehviläinen 2002, p. 91.

- ^ "Finland". Great Soviet Encyclopedia. MacMillan Publishing Company. 1974. ISBN 0028800109.

- ^ a b Wykes, Alan (1968). The Siege of Leningrad: Epic of Survival. Ballantine Books. pp. 9–21. ISBN 9780356029580.

- ^ a b c d e f Jones, Michael (2009). Leningrad: State of Siege. Hodder & Stoughton. p. 142. ISBN 9781848541214. Archived from the original on 22 February 2018.

Nikolai Baryshnikov, in [Finland and the Siege of Leningrad 1941–1944], has suggested that the country tacitly supported Hitler's starvation policy. Finland advanced to within twenty miles of Leningrad's outskirts, cutting the city's northern supply routes, but its troops then halted at its 1939 border, and did not undertake further action.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Brinkley, Douglas (2004). The World War II Desk Reference. HarperCollins. p. 210. ISBN 9780060526511.

- ^ a b Baryshnikov 2002. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBaryshnikov2002 (help)

- ^ a b Salisbury 2003, p. 246: "This line was only twenty miles from the Leningrad city limits."

- ^ a b c Glantz, David M. (2002). The Battle for Leningrad: 1941–1944. University Press of Kansas. p. 416. ISBN 9780700612086. Archived from the original on 2 March 2018.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Rutherford, Jeff (2014). Combat and Genocide on the Eastern Front: The German Infantry's War, 1941–1944. Cambridge University Press. p. 190. ISBN 9781107055711. Archived from the original on 27 February 2018.

The ensnaring of Leningrad between the German and Finnish armies did not end the combat in the region as the Soviets launched repeated and desperate attempts to regain contact with the city.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e Yarov, Sergey (2017). Leningrad 1941–42: Morality in a City under Siege. Foreword by John Barber. John Wiley & Sons. p. 7. ISBN 9781509508020. Archived from the original on 27 February 2018.

While the exact number who died during the siege by the German and Finnish armies from 8 September 1941 to 27 January 1944 will never be known, available data point to 900,000 civilian deaths, over half a million of whom died in the winter of 1941–2 alone.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Vehviläinen 2002, p. 30.

- ^ Vehviläinen 2002, p. 31.

- ^ Vehviläinen 2002, p. 33.

- ^ Vehviläinen 2002, p. 39.

- ^ Vehviläinen 2002, p. 44.

- ^ Vehviläinen 2002, p. 49.

- ^ Vehviläinen 2002, p. 65.

- ^ Vehviläinen 2002, p. 69.

- ^ Kirby 2006, p. 215.

- ^ a b c Vehviläinen 2002, p. 75.

- ^ Vehviläinen 2002, p. 70.

- ^ Vehviläinen 2002, p. 74.

- ^ Vehviläinen 2002, p. 76.

- ^ a b Vehviläinen 2002, p. 77.

- ^ Kirby 2006, p. 216.

- ^ Vehviläinen 2002, p. 78.

- ^ Vehviläinen 2002, p. 79.

- ^ Vehviläinen 2002, p. 80.

- ^ Vehviläinen 2002, p. 81.

- ^ Kirby 2006, p. 218.

- ^ Baryshnikov, Vladimir N. (2002). "Проблема обеспечения безопасности Ленинграда с севера в свете осуществления советского военного планирования 1932–1941 гг" [The problem of ensuring the security of Leningrad from the north in the light of the implementation of the Soviet military planning of 1932–1941]. St. Petersburg and the Countries of Northern Europe (in Russian). St. Petersburg: Russian Christian Humanitarian Academy. Archived from the original on 9 December 2007.

The actual war with Finland began first of all due to unresolved issues in Leningrad's security from the north and Moscow's concerns for the perspective of Finland's politics. At the same time, a desire to claim better strategic positions in case of a war with Germany had surfaced within the Soviet leadership.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Kozlov, Alexander I. (1997). Финская война. Взгляд "с той стороны" [The Finnish War: A look from the "other side"] (in Russian). Archived from the original on 9 December 2007.

After the rise of National Socialism to power in Germany, the geopolitical importance of the former 'buffer states' had drastically changed. Both the Soviet Union and Germany vied for the inclusion of these states into their spheres of influence. Soviet politicians and military considered it likely, that in case of an aggression against the USSR, German Armed Forces will use the territory of the Baltic states and Finland as staging areas for invasion—by either conquering or coercing these countries. None of the states of the Baltic region, excluding Poland, had sufficient military power to resist a German invasion.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Meltyukhov, Mikhail I. (2000). Упущенный шанс Сталина. Советский Союз и борьба за Европу: 1939–1941 [Stalin's Missed Chance – The Soviet Union and the Struggle for Europe: 1939–1941] (in Russian). Вече. ISBN 5-7838-0590-4. Archived from the original on 28 July 2009.

The English–French influence in the Baltics, characteristic for the '20s and early '30s, was increasingly limited by the growth of German influence. Due to the strategic importance of the region, the Soviet leadership also aimed to increase its influence there, using both diplomatic means as well as active social propaganda. By the end of the '30s, the main contenders for influence in the Baltics were Germany and the Soviet Union. Being a buffer zone between Germany and the USSR, the Baltic states were bound to them by a system of economic and non-aggression treaties of 1926, 1932 and 1939.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Davies, Norman (2006). Europe at War: 1939–1945 : No Simple Victory. Macmillan. pp. 137, 147. ISBN 9780333692851. Archived from the original on 21 February 2018.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Lukacs, John (2006). June 1941: Hitler and Stalin. Yale University Press. p. 57. ISBN 0300114370. Archived from the original on 21 February 2018.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Reiter 2009, p. 132.

- ^ Kirby 2006, p. 220.

- ^ Vehviläinen 2002, p. 83.

- ^ Kirby 2006, p. 219.

- ^ Vehviläinen 2002, p. 84.

- ^ a b Vehviläinen 2002, p. 85.

- ^ a b Kirby 2006, p. 221.

- ^ a b Vehviläinen 2002, p. 86.

- ^ a b Vehviläinen 2002, p. 87.

- ^ Lunde 2011, p. 9.

- ^ Jokipii 1999, pp. 145–146.

- ^ Trotter, Willian R. (1991). A Frozen Hell: The Russo-Finnish Winter War of 1939–1940. Algonquin Books. p. 226. ISBN 978-1565122499.

- ^ a b c Zeiler & DuBois 2012, pp. 208–221.

- ^ a b c d e f g Reiter 2009, pp. 135–136, 138.

- ^ a b Vehviläinen 2002, p. 102.

- ^ Suvorov, Viktor (2013). The Chief Culprit: Stalin's Grand Design to Start World War II. Naval Institute Press. p. 133. ISBN 9781612512686. Archived from the original on 22 February 2018.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Kinnunen & Kivimäki 2011, pp. 153–154.

- ^ Kirchubel 2013, pp. 114–115.

- ^ Jokipii 1999, p. 301.

- ^ Kirchubel 2013, p. 151.

- ^ Kirchubel 2013, pp. 120–121.

- ^ a b c Ziemke 2002, p. 9.

- ^ a b Vehviläinen 2002, p. 90.

- ^ Kinnunen & Kivimäki 2011, p. 168.

- ^ Nenye et al. 2016, p. 339.

- ^ Kirchubel 2013, p. 120-121.

- ^ Ziemke 2002, p. 10.

- ^ Ziemke 2015, pp. 149–151.

- ^ Ziemke 2002, pp. 7, 9.

- ^ Jokipii 1999, p. 282.

- ^ "Scan from the coastal defence ship Väinämöinen's log book". Digital Archive of the National Archives of Finland. 22 June 1941. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- ^ Hyvönen, Jaakko (2001). Kohtalokkaat lennot 1939–1944 [Fateful Flights 1939–1944] (in Finnish). Apali Oy. ISBN 9525026213.

- ^ Khazanov, Dmitriy B. (2006). "Первая воздушная операция советских ВВС в Великой Отечественной войне" [The first air operation of the Soviet Air Force in the Great Patriotic War]. 1941. Горькие уроки: Война в воздухе [1941: The War in the Air - The Bitter Lessons] (in Russian). Yauea. ISBN 5699178465. Archived from the original on 27 November 2011.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Platonov, Semen P., ed. (1964). Битва за Ленинград [The Battle for Leningrad]. Moscow: Voenizdat Ministerstva oborony SSSR.

- ^ Vehviläinen 2002, p. 88.

- ^ Kirby 2006, p. 222.

- ^ a b c d Lunde 2011, pp. 154–159.

- ^ Dzeniskevich, A.R.; Kovalchuk, V.M.; Sobolev, G.L.; Tsamutali, A.N.; Shishkin, V.A. (1970). Непокоренный Ленинград. раткий очерк истории города в период Великой Отечественной войны [Unconquered Leningrad. A short outline of the history of the city during the Great Patriotic War] (in Russian). The Academy of Sciences of the USSR. p. 19. Archived from the original on 7 November 2011.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Raunio & Kilin 2007, pp. 34, 62.

- ^ a b c Lunde 2011, pp. 167–172.

- ^ a b Raunio & Kilin 2007, pp. 151–155.

- ^ a b Salisbury 2003, pp. 210–211.

- ^ a b National Defence University (Finland) (1989). Jatkosodan historia. 2: Hyökkäys Itä-Karjalaan ja Karjalan kannakselle [History of the Continuation War, 2: The Offensive in Eastern Karelia and the Karelian Isthmus]. Sotatieteen laitoksen julkaisuja (in Finnish). Porvoo: WSOY. p. 261. ISBN 9510153281.

- ^ Luknitsky 1988, p. 72.

- ^ Werth 1999, pp. 360–361.

- ^ Raunio & Kilin 2008, pp. 10–11.

- ^ a b c Vehviläinen 2002, p. 96.

- ^ Mann & Jörgensen 2002, pp. 81–97, 199–200

- ^ Vehviläinen 2002, p. 95.

- ^ Weeks 2004, p. 9.

- ^ Stewart 2010, p. 158.

- ^ Suprun 1997, p. 35.

- ^ a b Vehviläinen 2002, p. 92.

- ^ Kirby 2006, p. 224.

- ^ Vehviläinen 2002, pp. 89–91.

- ^ Clements 2012, pp. 210–211.

- ^ a b Jutikkala & Pirinen 1988, p. 248.

- ^ Vehviläinen 2002, p. 101.

- ^ Jowett & Snodgrass 2012, pp. 29–31.

- ^ Ziemke 2015, p. 379.

- ^ a b Vehviläinen 2002, p. 98.

- ^ a b Vehviläinen 2002, p. 99.

- ^ Vehviläinen 2002, p. 97.

- ^ "War declared on Finland, Rumania, Hungary". The Examiner. Vol. C, no. 232. Launceston. 8 December 1941. Retrieved 24 February 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Vehviläinen 2002, p. 100.

- ^ Clements 2012, pp. 208–210.

- ^ Tikkanen, Pentti, H. (1973). Sissiprikaatin tuho [Destruction of the Partisan Brigade] (in Finnish). Arvi A. Karisto Osakeyhtiö. ISBN 9512307545.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Medvedev, Roy A. (1993). Генсек с Лубянки: политическая биография Ю.В. Андропова [The Secretary General from Lubyanka: Political Biography of Y.V. Andropov] (in Russian).

- ^ Viheriävaara, Eino (1982). Partisaanien jäljet 1941–1944 (in Finnish). Oulun Kirjateollisuus Oy. ISBN 9519939660.

- ^ a b Erkkilä, Veikko (1999). Vaiettu sota: Neuvostoliiton partisaanien iskut suomalaisiin kyliin [The Silenced War: Soviet partisan strikes on Finnish villages] (in Finnish). Arator Oy. ISBN 9529619189.

- ^ Hannikainen, Lauri (1992). Implementing Humanitarian Law Applicable in Armed Conflicts: The Case of Finland. Dordrecht: Martinuss Nijoff Publishers. ISBN 0792316118..

- ^ a b Martikainen, Tyyne (2002). Partisaanisodan siviiliuhrit [Civilian Casualties of the Partisan War]. PS-Paino Värisuora Oy. ISBN 9529143273..

- ^ Raunio & Kilin 2008, pp. 76–81.

- ^ Valtanen, Jaakko (1958). "Jäämeren rannikon sotatoimet toisen maailmansodan aikana". Tiede ja ase (in Finnish): 101–103. ISSN 0358-8882. Archived from the original on 2 March 2018.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Ziemke 2015, pp. 189, 238.

- ^ a b Glantz 2001, p. 179.

- ^ Kirschenbaum, Lisa A. (2006). The Legacy of the Siege of Leningrad, 1941–1995: Myth, Memories, and Monuments. Cambridge University Press. p. 44. ISBN 9781139460651. Archived from the original on 25 February 2018.

The blockade began two days later when German and Finnish troops severed all land routes in and out of Leningrad.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Clements 2012, pp. 211–213.

- ^ Clements 2012, p. 213.

- ^ Peri, Alexis (2017). The War Within. Harvard University Press. p. 4. ISBN 9780674971554. Archived from the original on 25 February 2018.

In August 1941, Hitler's Army Group North and his Finnish allies began to encircle Leningrad. They rapidly extended their territorial holdings first in the west and south and eventually in the north. By 29 August 1941, they had severed the last railway line that connected Leningrad to the rest of the USSR. By early September, Leningrad was completely cut off, save a heavily patrolled water passage over Lake Ladoga.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Kiljanen 1968.

- ^ Nenye et al. 2016, pp. 136–138.

- ^ Kiljanen 1968, p. 123.

- ^ Ahtokari, Reijo; Pale, Erkki. Suomen radiotiedustelu 1927–1944 [Finnish radio intelligence 1927–1944]. Helsinki: Hakapaino Oy. pp. 191–198. ISBN 952909437X.

- ^ a b c Kirby 2006, p. 225.

- ^ Vehviläinen 2002, p. 105.

- ^ a b Vehviläinen 2002, p. 107.

- ^ Kirby 2006, p. 226.

- ^ Haavikko 1999, pp. 115–116

- ^ Rautkallio, Hannu (1989). Suomen juutalaisten aseveljeys [Brotherhood-in-Arms of the Finnish Jews]. Tammi.

- ^ Vuonokari, Tuulikki (2003). "Jews in Finland During the Second World War". Finnish Institutions Research Paper. University of Tampere. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Finland" (PDF). Yad Vashem International School for Holocaust Studies. 9 May 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 April 2016. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Vehviläinen 2002, p. 103.

- ^ Reiter 2009, pp. 134–137.

- ^ Mäkelä, Jukka (1967). Helsinki liekeissä: suurpommitukset helmikuussa 1944 [Helsinki Burning: Great Raids in February 1944] (in Finnish). Helsinki: W. Söderström Oy. p. 20.

- ^ Paulman, F. I. (1980). "Nachalo osvobozhdeniya Sovetskoy Estoniy". Ot Narvy do Syrve [From Narva to Sõrve] (in Russian). Tallinn: Eesti Raamat. pp. 7–119.

- ^ Laar, Mart (2005). Estonia in World War II. Tallinn: Grenader. pp. 32–59. Archived from the original on 24 February 2018.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Jackson, Robert (2007). Battle of the Baltic: The Wars 1918–1945. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Maritime. ISBN 978-1844154227.

- ^ Grier 2007, p. 121.

- ^ Gebhardt 1990, p. 1.

- ^ a b Moisala & Alanen 1988.

- ^ Erickson 1993, p. 197.

- ^ a b Gebhardt 1990, p. 2.

- ^ Glantz & House 1998, p. 202.

- ^ Nenye et al. 2016, p. 21.

- ^ Virkkunen 1985, pp. 297–300

- ^ Mcateer, Sean M. (2009). 500 Days: The War in Eastern Europe, 1944–1945. Dorrance Publishing. Archived from the original on 29 December 2015.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Jowett & Snodgrass 2012, p. 14.

- ^ Jaques, Tony (2007). Dictionary of Battles and Sieges: F–O. Greenwood Publishing Group. Archived from the original on 29 December 2015.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Lunde 2011, p. 299.

- ^ Raunio & Kilin 2008, pp. 287–291.

- ^ a b c Grier 2007, p. 31.

- ^ a b Erickson 1993, pp. 329–330.

- ^ Glantz & House 1998, p. 229.

- ^ Glantz & House 1998, pp. 201–203.

- ^ a b Nenye et al. 2016, pp. 529–531.

- ^ a b c Vehviläinen 2002, pp. 147–149.

- ^ Reiter 2009, p. 131.

- ^ Rothwell, Victor (2006). War Aims in the Second World War: The War Aims of the Key Belligerents 1939–1945. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 143, 145. ISBN 978-0748615032.

- ^ Reiter 2009, pp. 134–136, 138.

- ^ Baryshnikov 2002, pp. 222–223 (section heading "Стремительный прорыв", paragraph 48 after cit. 409 et seq.). sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBaryshnikov2002 (help)

- ^ Ylikangas, Heikki (2009). Yhden miehen jatkosota [One Man's Continuation War] (in Finnish). Otava. pp. 40–61. ISBN 978-951-1-24054-9.

- ^ a b Kurenmaa, Pekka; Lentilä, Riitta (2005). "Sodan tappiot". In Leskinen, Jari; Juutilainen, Antti (eds.). Jatkosodan pikkujättiläinen (in Finnish). WSOY. pp. 1150–1162. ISBN 9510286907.

- ^ Nenye et al. 2016, pp. 279–280, 320–321.

- ^ Ziemke 2002, p. 390.

- ^ Vehviläinen 2002, p. 162.

- ^ Lunde 2011, p. 379.

- ^ Provis, Peter (1999). "Finnish achievement in the Continuation War and after". Nordic Notes. 3. Flinders University. ISSN 1442-5165. Archived from the original on 3 November 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Hietanen, Silvo (1992). "Evakkovuosi 1944 – jälleen matkassa" [Evacuation 1944 – On the Road Again]. Kansakunta sodassa – 3. osa Kuilun yli (in Finnish). Helsinki: Valtion Painatuskeskus. pp. 130–139. ISBN 9518613850.

- ^ a b Taagepera 2013, p. 144.

- ^ Scott & Liikanen 2013, pp. 59–60.

- ^ Jakobson, Max (8 November 2003). "Wartime refugees made pawns in cruel diplomatic game" (in Finnish). Helsingin Sanomat. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011.

- ^ Ylikangas, Heikki (2004). "Heikki Ylikankaan selvitys valtioneuvoston kanslialle". Valtioneuvoston kanslian julkaisusarja (in Finnish). ISBN 952-5354-47-4. ISSN 0782-6028.