Desmond Tutu

Desmond Tutu | |

|---|---|

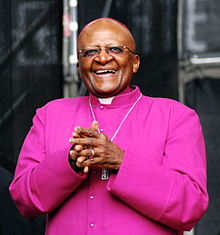

| Archbishop Emeritus of Cape Town | |

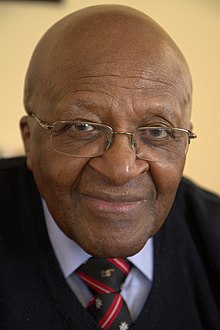

Tutu in 2013 | |

| Province | Anglican Church of Southern Africa |

| See | Cape Town (retired) |

| Installed | 7 September 1986 |

| Term ended | 1996 |

| Predecessor | Philip Russell |

| Successor | Njongonkulu Ndungane |

| Other post(s) | Bishop of Lesotho Bishop of Johannesburg Archbishop of Cape Town |

| Orders | |

| Ordination | Deacon Priest – 1960 |

| Consecration | 1976 |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Desmond Mpilo Tutu 7 October 1931 |

| Alma mater | King's College London |

| Signature | |

| Styles of Desmond Tutu | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reference style | Archbishop |

| Spoken style | Your Grace |

| Religious style | The Most Reverend |

Desmond Mpilo Tutu (born 7 October 1931) is a South African social rights activist and retired Anglican bishop who rose to worldwide fame during the 1980s as an opponent of apartheid.

He was the first black Archbishop of Cape Town and bishop of the Church of the Province of Southern Africa (now the Anglican Church of Southern Africa).

Tutu's admirers see him as a great man who since the demise of apartheid has been active in the defence of human rights and uses his high profile to campaign for the oppressed. He has campaigned to fight HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, poverty, racism, sexism, homophobia and transphobia. He received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1984; the Albert Schweitzer Prize for Humanitarianism in 1986; the Pacem in Terris Award in 1987; the Sydney Peace Prize in 1999; the Gandhi Peace Prize in 2007;[1] and the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2009. He has also compiled several books of his speeches and sayings.

Early life

Desmond Mpilo Tutu was born in Klerksdorp, Transvaal, the second of four children of Zacheriah Zililo Tutu and his wife, Aletta Tutu, and the only son.[2] Tutu's family moved to Johannesburg when he was twelve. His father was a teacher and his mother was a cleaner and cook at a school for the blind.[3] Here he met Trevor Huddleston, who was a parish priest in the black slum of Sophiatown. "One day," said Tutu, "I was standing in the street with my mother when a white man in a priest's clothing walked past. As he passed us he took off his hat to my mother. I couldn't believe my eyes—a white man who greeted a black working class woman!"[3]

Although Tutu wanted to become a doctor, his family could not afford the training, and he followed his father's footsteps into teaching. Tutu studied at the Pretoria Bantu Normal College from 1951 to 1953, and went on to teach at Johannesburg Bantu High School and at Munsienville High School in Mogale City. However, he resigned following the passage of the Bantu Education Act, in protest of the poor educational prospects for black South Africans. He continued his studies, this time in theology, at St Peter's Theological College in Rosettenville, Johannesburg, and in December 1961 was ordained as an Anglican priest following in the footsteps of his mentor and fellow activist, Trevor Huddleston.[citation needed]

Tutu then travelled to King's College London, (1962–1966), where he received his bachelor's and master's degrees in theology. During this time he worked as a part-time curate, first at St Alban's Church, Golders Green, and then at St Mary's Church in Bletchingley, Surrey.[4] He later returned to South Africa and became chaplain at the University of Fort Hare in 1967.[citation needed] From 1970 to 1972, Tutu lectured at the National University of Lesotho.

In 1972, Tutu returned to the UK, where he was appointed vice-director of the Theological Education Fund of the World Council of Churches, at Bromley in Kent. He returned to South Africa in 1975 and was appointed Dean of St Mary's Cathedral in Johannesburg.[citation needed]

Personal life

On 2 July 1955, Tutu married Nomalizo Leah Shenxane, a teacher whom he had met while at college. They had four children: Trevor Thamsanqa Tutu, Theresa Thandeka Tutu, Naomi Nontombi Tutu and Mpho Andrea Tutu, all of whom attended the Waterford Kamhlaba School in Swaziland.[5]

In 1975 he moved into what is now known as Tutu House on Soweto's well known Vilakazi Street which is also the location of the late Nelson Mandela's previous house. He and his family were still living there in 2005.[6] It is said to be one of the few streets in the world where two Nobel Prize winners have lived.[7]

His son, Trevor Tutu, was arrested in 1989 at East London Airport for falsely claiming there had been a bomb on board a South African Airways' plane. He was convicted in 1991 of contravening the Civil Aviation Act.[8] The bomb threat delayed the Johannesburg-bound flight for more than three hours, costing South African Airways some R28000. At the time, Trevor Tutu announced his intention to appeal against his sentence, but failed to arrive for the appeal hearings. He forfeited his bail of R15000.[8] He was due to begin serving his sentence in 1993, but failed to hand himself over to prison authorities. He was finally arrested in Johannesburg in August 1997. He applied for amnesty from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission which was granted in 1997; a move that was harshly criticised by some as preferential treatment by a commission that was co-founded and chaired by his father.[9][10] He was then released from Goodwood Prison in Cape Town where he had begun serving his three-and-a-half-year prison sentence after a court in East London refused to grant him bail.[11]

Naomi Tutu founded the Tutu Foundation for Development and Relief in Southern Africa, based in Hartford, Connecticut. She attended the Patterson School of Diplomacy and International Commerce at the University of Kentucky and has followed in her father's footsteps as a human rights activist. She is currently a graduate student at Vanderbilt University Divinity School, in Nashville, Tennessee.[12] Desmond Tutu's other daughter, Mpho Tutu, has also followed in her father's footsteps and in 2004 was ordained an Episcopal priest by her father.[13] She is also the founder and executive director of the Tutu Institute for Prayer and Pilgrimage and the chairperson of the board of the Global AIDS Alliance.[14]

In 1997, Tutu was diagnosed with prostate cancer and underwent successful treatment in the US. He subsequently became patron of the South African Prostate Cancer Foundation, which was established in 2007.[15]

Beginning on his 79th birthday, Tutu entered a phased retirement from public life, starting with only one day per week in his office through February 2011. On 23 May 2011 in Shrewsbury, Massachusetts, Tutu gave what was said to be his last major public speech outside of South Africa. Tutu honoured his commitments through May 2011 and added no more commitments.[16]

However, Tutu subsequently came out of retirement to give a commencement speech at Gonzaga University in Spokane, Washington, on 13 May 2012, and gave an address at Butler University's Desmond Tutu Center in Indianapolis, Indiana on 12 September of that year.[17]

Role during apartheid

| Part of a series on |

| Apartheid |

|---|

|

In 1976, the protests in Soweto, also known as the Soweto Riots, against the government's use of Afrikaans as the compulsory language of instruction in black schools became an uprising against apartheid. From then on Tutu supported an economic boycott of his country. He vigorously opposed the "constructive engagement" policy of the Reagan administration in the United States, which advocated "friendly persuasion".[18] Tutu rather supported disinvestment, although it hit the poor hardest, for if disinvestment threw blacks out of work, Tutu argued, at least they would be suffering "with a purpose".[citation needed] Tutu pressed the advantage and organised peaceful marches which brought 30,000 people onto the streets of Cape Town.[19]

Tutu was Bishop of Lesotho from 1976 until 1978, when he became Secretary-General of the South African Council of Churches. From this position, he was able to continue his work against apartheid with agreement from nearly all churches. Through his writings and lectures at home and abroad, Tutu consistently advocated reconciliation between all parties involved in apartheid. Tutu's opposition to apartheid was vigorous and unequivocal, and he was outspoken both in South Africa and abroad. He often compared apartheid to Nazism; as a result the government twice revoked his passport, and he was jailed briefly in 1980 after a protest march. It was thought by many that Tutu's increasing international reputation and his rigorous advocacy of non-violence protected him from harsher penalties. Tutu was also harsh in his criticism of the violent tactics of some anti-apartheid groups such as the African National Congress and denounced terrorism and Communism.[citation needed]

When a new constitution was proposed for South Africa in 1983 to defend against the anti-apartheid movement, Tutu helped form the National Forum Committee to fight the constitutional changes.[20]

In 1990, Tutu and the ex-Vice-Chancellor of the University of the Western Cape Professor Jakes Gerwel founded the Desmond Tutu Educational Trust. The Trust – established to fund developmental programmes in tertiary education – provides capacity building at 17 historically disadvantaged institutions. Tutu's work as a mediator to prevent all-out racial war was evident at the funeral of South African Communist Party leader Chris Hani in 1993. Tutu spurred a crowd of 120,000 to repeat after him the chants, over and over: "We will be free!", "All of us!", "Black and white together!"[21]

In 1993, Tutu was a patron of the Cape Town Olympic Bid Committee. In 1994, he was an appointed a patron of the World Campaign Against Military and Nuclear Collaboration with South Africa, Beacon Millennium and Action from Ireland. In 1995, he was appointed a Chaplain and Sub-Prelate of the Venerable Order of Saint John by Queen Elizabeth II,[22] and he became a patron of the American Harmony Child Foundation and the Hospice Palliative Care Association (HPCA) of South Africa.[citation needed]

Role since apartheid

After the fall of apartheid, Tutu headed the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. He retired as Archbishop of Cape Town in 1996 and was made emeritus Archbishop of Cape Town, an honorary title that is unusual in the Anglican church.[23] He was succeeded by Njongonkulu Ndungane. At a thanksgiving for Tutu upon his retirement as Archbishop in 1996, Nelson Mandela said that Tutu made an "immeasurable contribution to our nation".[24]

Tutu is generally credited with coining the term Rainbow Nation as a metaphor for post-apartheid South Africa after 1994 under African National Congress rule. The expression has since entered mainstream consciousness to describe South Africa's ethnic diversity.[citation needed]

Since his retirement, Tutu has worked as a global activist on issues pertaining to democracy, freedom and human rights. He is the patron of the Institute for Justice and Reconciliation, the successor organisation of the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission. In this role he presents the annual South African Reconciliation Award. In 2006, Tutu launched a global campaign, organised by Plan, to ensure that all children are registered at birth, as an unregistered child did not officially exist and was vulnerable to traffickers and during disasters.[25] Tutu is the Patron of the educational improvement charity Link Community Development.[citation needed] Tutu is also a member of the PeaceJam Foundation.[26]

Tutu had announced he would retire from public life when he turned 79 in October 2010.

- "Instead of growing old gracefully, at home with my family – reading and writing and praying and thinking – too much of my time has been spent at airports and in hotels," the Nobel laureate said in a statement.[27]

Role in South Africa

Tutu is widely regarded as "South Africa's moral conscience"[28] and was described by former President of South Africa Nelson Mandela as "sometimes strident, often tender, never afraid and seldom without humour, Desmond Tutu's voice will always be the voice of the voiceless".[24] Since his retirement, Tutu has worked to critique the new South African government. Tutu has been vocal in condemnation of corruption, the ineffectiveness of the ANC-led government to deal with poverty, and the recent outbreaks of xenophobic violence in some townships in South Africa.[citation needed]

After a decade of freedom for South Africa, Tutu was honoured with the invitation to deliver the annual Nelson Mandela Foundation Lecture. On 23 November 2004, Tutu gave an address entitled "Look to the Rock from Which You Were Hewn". This lecture, critical of the ANC-controlled government, stirred a pot of controversy between Tutu and Thabo Mbeki, calling into question "the right to criticise".[29]

On 10 May 2013, Tutu said he would no longer be able to vote for the African National Congress, citing inequality, violence, and corruption. "The ANC was very good at leading us in the struggle to be free from oppression," Archbishop Tutu wrote, "But it doesn't seem to me now that a freedom-fighting unit can easily make the transition to becoming a political party." He sharply criticised the decision of the South African government to delay the issuance of a visa to the Dalai Lama, accusing the government of "kowtowing to China".[30]

Tutu stated that Nelson Mandela would be dismayed that Afrikaners got excluded from memorial services to commemorate Mandela's death.[31] The spokesman for Tutu said the cleric changed his plans and would attend the funeral of Mandela, after not originally being officially invited.[32]

Continued economic stratification and political corruption

Tutu made a stinging attack on South Africa's political elite, saying the country was "sitting on a powder keg"[33] because of its failure to alleviate poverty a decade after apartheid's end. Tutu also said that attempts to boost black economic ownership were benefiting only an elite minority, while political "kowtowing" within the ruling ANC was hampering democracy. Tutu asked, "What is black empowerment when it seems to benefit not the vast majority but an elite that tends to be recycled?"[33]

Tutu criticised politicians for debating whether to give the poor an income grant of $16 (£12) a month and said the idea should be seriously considered. Tutu has often spoken in support of the Basic Income Grant (BIG) which has so far been defeated in parliament. After the first round of volleys were fired, South African Press Association journalist, Ben Maclennan reported Tutu's response as: "Thank you Mr President for telling me what you think of me, that I am—a liar with scant regard for the truth, and a charlatan posing with his concern for the poor, the hungry, the oppressed and the voiceless."[34]

Tutu warned of corruption shortly after the re-election of the African National Congress government of South Africa, saying that they "stopped the gravy train just long enough to get on themselves."[35] In August 2006 Tutu publicly urged Jacob Zuma, the South African politician (now President) who had been accused of sexual crimes and corruption, to drop out of the ANC's presidential succession race. He said in a public lecture that he would not be able to hold his "head high" if Zuma became leader after being accused both of rape and corruption. In September 2006, Tutu repeated his opposition to Zuma's candidacy as ANC leader due to Zuma's "moral failings."[36] In November 2013 he warned that politicians and activists were stoking anger which resulted in a spate of sometimes violent protests, that he identified as an assault on South Africa's democracy.[37]

Complications accompanying initiation rituals

Initiation rituals amongst the Xhosa people have led to the death of over 825 boys since 1995, many others suffered complications including penile amputation. Following the death of 43 boys during December 2013, Tutu urged traditional leadership and government to intervene, and “to draw on the skills of qualified medical practitioners to enhance our traditional circumcision practices.” He furthermore emphasized the cultural importance of the ritual as educational institution, preparing initiates “to contribute to building a better society for all.”[38]

Criticism of Tutu

The head of the Congress of South African Students condemned Tutu as a "loose cannon" and a "scandalous man" – a reaction which prompted an angry Mbeki to side with Tutu. Zuma's personal advisor responded by accusing Tutu of having double standards and "selective amnesia" (as well as being old). Elias Khumalo claims that Tutu "had found it so easy to accept the apology from the apartheid government that committed unspeakable atrocities against millions of South Africans", yet now "cannot find it in his heart to accept the apology from this humble man who has erred".[39]

Chair of The Elders

On 18 July 2007, in Johannesburg, Nelson Mandela, Graça Machel, and Tutu convened The Elders, a group of world leaders to contribute their wisdom, kindness, leadership and integrity to tackle some of the world's toughest problems. Mandela announced its formation in a speech on his 89th birthday.

"This group can speak freely and boldly, working both publicly and behind the scenes on whatever actions need to be taken," Mandela commented. "Together we will work to support courage where there is fear, foster agreement where there is conflict, and inspire hope where there is despair."[40]

Tutu served as Chair of The Elders from the founding of the group in July 2007 to May 2013. Upon stepping down and becoming an Honorary Elder, he said: "As Elders we should always oppose presidents for Life. After six wonderful years as Chair, I am sad to say that it was time for me to step down."[41] Kofi Annan currently serves as Chair and Gro Harlem Brundtland as Deputy Chair. The other members of the group are Martti Ahtisaari, Ela Bhatt, Lakhdar Brahimi, Fernando Henrique Cardoso, Jimmy Carter, Hina Jilani, Graça Machel, Mary Robinson and Ernesto Zedillo.

Several other leaders were previously affiliated with The Elders. Former Elder Muhammad Yunus stepped down as a member of the group in September 2009, stating that he was unable to do justice to his membership due to the demands of his work.[42] Aung San Suu Kyi is a former honorary Elder. During her period under house arrest, the Elders kept an empty chair at each of their meetings to mark their solidarity with Suu Kyi and Burma’s other political prisoners. In line with the requirement that members of The Elders should not hold public office, Suu Kyi stepped down as an honorary Elder following her election to parliament on 1 April 2012.[43] Li Zhaoxing was present at the launch of The Elders but did not formally join the group.

The Elders work globally, on thematic as well as geographically specific subjects. The Elders' priority issue areas include the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, the Korean Peninsula, Sudan and South Sudan, sustainable development, and equality for girls and women.[44]

Tutu led The Elders' visit to Sudan in October 2007 – their first mission after the group was founded – to foster peace in the Darfur crisis. "Our hope is that we can keep Darfur in the spotlight and spur on governments to help keep peace in the region," said Tutu.[45] He has also travelled with Elders delegations to Cote d’Ivoire, Cyprus, Ethiopia, India, South Sudan and the Middle East.[46] Tutu has been particularly involved in The Elders' initiative on child marriage, attending the Clinton Global Initiative in New York in September 2011 to launch Girls Not Brides: The Global Partnership to End Child Marriage.[47]

The Elders are independently funded by a group of donors: Sir Richard Branson and Jean Oelwang (Virgin Unite), Peter Gabriel (The Peter Gabriel Foundation), Kathy Bushkin Calvin (The United Nations Foundation), Jeremy Coller and Lulit Solomon (J Coller Foundation), Niclas Kjellström-Matseke (Swedish Postcode Lottery), Randy Newcomb and Pam Omidyar (Humanity United), Jeff Skoll and Sally Osberg (Skoll Foundation), Jovanka Porsche (HP Capital Partners), Julie Quadrio Curzio (Quadrio Curzio Family Trust), Amy Towers (The Nduna Foundation), Shannon Sedgwick Davis (The Bridgeway Foundation) and Marieke van Schaik (Dutch Postcode Lottery). Mabel van Oranje, former CEO of The Elders, sits on the Advisory Council in her capacity as Advisory Committee Chair of Girls Not Brides: The Global Partnership to End Child Marriage.[48]

Role in the developing world

Tutu has focused on drawing awareness to issues such as poverty, AIDS and non-democratic governments in the Third World. In particular he has focused on issues in Zimbabwe and Palestine.

Zimbabwe

Tutu has been vocal in his criticism of human rights abuses in Zimbabwe as well as the South African government's policy of quiet diplomacy towards Zimbabwe. In 2007 he said the "quiet diplomacy" pursued by the Southern Africa Development Community (SADC) had "not worked at all" and he called on Britain and the West to pressure SADC, including South Africa, which was chairing talks between President Mugabe's Zanu-PF party and the opposition Movement for Democratic Change, to set firm deadlines for action, with consequences if they were not met.[49] Tutu has often criticised Robert Mugabe in the past and he once described the leader as "a cartoon figure of an archetypical African dictator".[28] In 2008, he called for the international community to intervene in Zimbabwe – by force if necessary.[50] Mugabe, on the other hand, has called Tutu an "angry, evil and embittered little bishop".[51]

Tutu has often stated that all leaders in Africa should condemn Zimbabwe: "What an awful blot on our copy book. Do we really care about human rights, do we care that people of flesh and blood, fellow Africans, are being treated like rubbish, almost worse than they were ever treated by rabid racists?"[28] After the Zimbabwean presidential elections in April 2008, Tutu expressed his hope that Mugabe would step down after it was initially reported that Mugabe had lost the elections. Tutu reiterated his support of the democratic process and hoped that Mugabe would adhere to the voice of the people.[52]

Tutu called Mugabe "someone we were very proud of", as he "did a fantastic job, and it’s such a great shame, because he had a wonderful legacy. If he had stepped down ten or so years ago he would be held in very, very high regard. And I still want to say we must honour him for the things that he did do, and just say what a shame."[52]

Tutu stated that he feared that riots would break out in Zimbabwe if the election results were ignored. He proposed that a peace-keeping force should be sent to the region to ensure stability.[52]

Solomon Islands

In 2009, Tutu assisted in the establishing of the Solomon Islands' Truth and Reconciliation Commission, modelled after the South African body of the same name.[53][54] He spoke at its official launch in Honiara on 29 April 2009, emphasising the need for forgiveness to build lasting peace.[55]

Israel and Palestine

Tutu has acknowledged the significant role Jews played in the anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa and has voiced support for Israel's security concerns, speaking against suicide bombing.[56] He is an adversary of the doctrine of Supersessionism, the biblical interpretation that the Christian Church supersedes or replaces Israel in God's plan, and that the New Covenant nullifies the biblical promises made to Israel.[57] He is also an active and prominent proponent of the campaign for divestment from Israel,[58] likening Israel's treatment of Palestinians to the treatment of Black South Africans under apartheid.[56] Tutu drew this comparison on a Christmas visit to Jerusalem in 1989, when he said that he is a "black South African, and if I were to change the names, a description of what is happening in Gaza and the West Bank could describe events in South Africa."[59] He made similar comments in 2002, speaking of "the humiliation of the Palestinians at checkpoints and roadblocks, suffering like us when young white police officers prevented us from moving about".[60]

In 1988, the American Jewish Committee noted that Tutu was strongly critical of Israel's military and other connections with apartheid-era South Africa, and quoted him as saying that Zionism has "very many parallels with racism", on the grounds that it "excludes people on ethnic or other grounds over which they have no control". While the AJC was critical of some of Tutu's views, it dismissed "insidious rumours" that he had made antisemitic statements.[61] (The exact wording of Tutu's statement was reported differently in different sources. A Toronto Star article from the period indicates that he described Zionism "as a policy that looks like it has many parallels with racism, the effect is the same.")[62]

Tutu preached a message of forgiveness during a 1989 trip to Israel's Yad Vashem museum, saying "Our Lord would say that in the end the positive thing that can come is the spirit of forgiving, not forgetting, but the spirit of saying: God, this happened to us. We pray for those who made it happen, help us to forgive them and help us so that we in our turn will not make others suffer."[63] Some found this statement offensive, with Rabbi Marvin Hier of the Simon Wiesenthal Center calling it "a gratuitous insult to Jews and victims of Nazism everywhere."[64] Tutu was subjected to racial slurs during this visit to Israel, with vandals writing "Black Nazi pig" on the walls of the St. George's Cathedral in East Jerusalem, where he was staying.[63]

In 2002, when delivering a public lecture in support of divestment, Tutu said "My heart aches. I say why are our memories so short. Have our Jewish sisters and brothers forgotten their humiliation? Have they forgotten the collective punishment, the home demolitions, in their own history so soon? Have they turned their backs on their profound and noble religious traditions? Have they forgotten that God cares deeply about the downtrodden?"[56] He argued that Israel could never live in security by oppressing another people, and stated, "People are scared in this country [the US], to say wrong is wrong because the Jewish lobby is powerful – very powerful. Well, so what? For goodness sake, this is God's world! We live in a moral universe. The apartheid government was very powerful, but today it no longer exists."[56] The latter statement was criticised by some Jewish groups, including the Anti-Defamation League.[65][66] When he edited and reprinted parts of his speech in 2005, Tutu replaced the words "Jewish lobby" with "pro-Israel lobby".[67]

American attorney Alan Dershowitz referred to Tutu as a "racist and a bigot" during the controversial Durban II conference in April 2009.[68]

Global March to Jerusalem

As of March 2012, Tutu was a member of the Advisory Board for Global March to Jerusalem (GM2J).[69] According to Paul Larudee, founding member of GM2J, the aim was to "march from many starting points and converge on Jerusalem, either reaching that destination or getting as close to it as possible" on 30 March 2012 as an act of nonviolent resistance to what he describes as Israel's Judaization of Jerusalem.[70]

Palestinian Christians

In 2003, Tutu accepted the role as patron of Sabeel International,[71] a Christian liberation theology organisation which supports the concerns of the Palestinian Christian community and has actively lobbied the international Christian community for divestment from Israel.[72] In the same year, Tutu received an International Advocate for Peace Award from the Cardozo School of Law, an affiliate of Yeshiva University, sparking scattered student protests and condemnations from representatives of the Simon Wiesenthal Center and Anti-Defamation League.[73] A 2006 opinion piece in the Jerusalem Post newspaper described him as "a friend, albeit a misguided one, of Israel and the Jewish people".[74] The Zionist Organization of America has led a campaign to protest Tutu's appearances at North American campuses.

Gaza

Tutu was appointed as the UN Lead for an investigation into the Israeli bombings in the Beit Hanoun November 2006 incident. Israel refused Tutu's delegation access, so the investigation didn't occur until 2008.

During that fact-finding mission, Tutu called the Gaza blockade an abomination[75] and compared Israel's behaviour to the military junta in Burma.

During the 2008–2009 Gaza War, Tutu called the Israeli offensive "war crimes".

Protests against Tutu in the United States

In 2011, 27 members of the American Psychiatric Association boycotted the group's annual meeting in Honolulu, Hawaiʻi to protest against the selection of Tutu as speaker, as they objected to Tutu’s statement that Zionism has "very many parallels with racism", his description of Israel as an apartheid state, his call for academic and cultural boycotts of Israel, a position which conflicts with APA’s policy, and what the members regarded as his "strongly anti-Semitic comments" and "falsehoods about Israel". APA president Carol Bernstein invited Tutu to speak about South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission for the Menninger lecture.[76][77][78]

In 2007, the president of the University of St. Thomas in Minnesota cancelled a planned speech by Tutu, on the grounds that his presence might offend some members of the local Jewish community.[79] Many faculty members opposed this decision, and with some describing Tutu as the victim of a smear campaign. The group Jewish Voice for Peace led an email campaign calling on St. Thomas to reconsider its decision,[80] which the president did and invited Tutu to campus.[81] Tutu declined the re-invitation, speaking instead at the Minneapolis Convention Center at an event hosted by Metro State University.[82] However, Tutu addressed the issue two days later while making his final appearance at Metro State.

"There were those who tried to say 'Tutu shouldn’t come to [St.Thomas] to speak.' I was 10,000 miles away and I thought to myself, 'Ah, no,’ because there were many here who said 'No, come and speak,’" Tutu said. "People came and stood and had demonstrations to say 'Let Tutu speak.' [Metropolitan State] said 'Whatever, he can come and speak here.' Professor Toffolo and others said 'We stand for him.' So let us stand for them."[83]

China

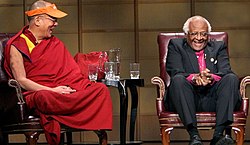

Tutu wrote to the Chinese government demanding the release of dissident Yang Jianli in 2007.[84] He criticised China for not doing more against the Darfur genocide.[85] During the 2008 Tibetan unrest, Tutu praised the 14th Dalai Lama and said that the government of China should "listen to [his] pleas for... no further violence".[86] He later spoke to a rally calling on heads of states worldwide not to attend the 2008 Summer Olympics opening ceremony "for the sake of the beautiful people of Tibet".[87]

Tibet

The Dalai Lama was not granted a visa to South Africa to participate in the 80th birthday party of fellow Nobel Peace Prize winner Tutu on 7 October 2011. He said his application for a visa had not come through on time despite having been made to Pretoria several weeks earlier.[88][89] In 2009 Beijing had warned against allowing the Dalai Lama into the country.

United Nations role

In 2003, Tutu was elected to the board of directors of the International Criminal Court's Trust Fund for Victims.[90] He was named a member of the UN advisory panel on genocide prevention in 2006.[91]

However, Tutu has also criticised the UN, particularly on the issue of West Papua. Tutu expressed support for the West Papuan independence movement, criticising the UN's role in the takeover of West Papua by Indonesia. Tutu said: "For many years the people of South Africa suffered under the yoke of oppression and apartheid. Many people continue to suffer brutal oppression, where their fundamental dignity as human beings is denied. One such people is the people of West Papua."[92]

Tutu was named to head a United Nations fact-finding mission to the Gaza Strip town of Beit Hanoun, where, in a November 2006 incident the Israel Defense Forces killed 19 civilians after troops wound up a week-long incursion aimed at curbing Palestinian rocket attacks on Israel from the town.[93] Tutu planned to travel to the Palestinian territory to "assess the situation of victims, address the needs of survivors and make recommendations on ways and means to protect Palestinian civilians against further Israeli assaults," according to the president of the UN Human Rights Council, Luis Alfonso De Alba.[94] Israeli officials expressed concern that the report would be biased against Israel. Tutu cancelled the trip in mid-December, saying that Israel had refused to grant him the necessary travel clearance after more than a week of discussions.[95] However, Tutu and British academic Christine Chinkin are now due to visit the Gaza Strip via Egypt and will file a report at the September 2008 session of the Human Rights Council.[96]

Against poverty

Before the 31st G8 summit at Gleneagles, Scotland, in 2005, Tutu called on world leaders to promote free trade with poorer countries. Tutu also called on an end to expensive taxes on anti-AIDS drugs.[97]

Before the 32nd G8 summit in Heiligendamm, Germany, in 2007, Tutu called on the G8 to focus on poverty in the Third World. Following the United Nations Millennium Summit in 2000, it appeared that world leaders were determined as never before to set and meet specific goals regarding extreme poverty.[98]

Against unilateralism

In January 2003, Tutu attacked British Prime Minister Tony Blair's stance in supporting American President George W. Bush over Iraq. Tutu asked why Iraq was being singled out when Europe, India and Pakistan also had many weapons of mass destruction.[99] In 2012, Tutu pulled out of an event in South Africa at which Blair was also due to appear, citing what he described as the former UK prime minister's "morally indefensible" decision to attack Iraq,[100] and called for him to face trial for alleged war crimes at the Hague.[101] Blair defended himself at the conference,[102] while Juan Cole observed that "Blair was paid thousands of dollars to attend the conference; if Tutu had gone, he would have spoken gratis."[103]

In October 2004, Tutu appeared in a play at Off Broadway, New York, called Guantanamo – Honor-bound to Defend Freedom. This play was highly critical of the US handling of detainees at Guantanamo Bay. Tutu played Lord Justice Steyn, a judge who questions the legal justification of the detention regime.[104]

In January 2005, Tutu added his voice to the growing dissent over terrorist suspects held at Camp X-Ray in Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, referring to detentions without trial as "utterly unacceptable." Tutu compared these detentions to those under Apartheid. Tutu also emphasised that when South Africa had used those methods the country had been condemned; however when powerful countries such as Britain and the United States of America had invoked such power, the world was silent and in that silence accepted their methods even though the left charged that they violated essential human rights.[105]

In February 2006, Tutu repeated these statements after a UN report was published which called for the closure of the camp. Tutu stated that the Guantanamo camp was a stain on the character of the United States, while the legislation in Britain which gave a 28-day detention period for terror suspects was "excessive" and "untenable". Tutu claimed that arguments being made in Britain and the United States were similar to those the South African apartheid regime had used. "It is disgraceful and one cannot find strong enough words to condemn what Britain and the United States and some of their allies have accepted," said Tutu. Tutu also spoke against Tony Blair's failed attempt to hold terrorist suspects in Britain for up to 90 days without charge. "Ninety days for a South African is an awful déjà-vu because we had in South Africa in the bad old days a 90-day detention law," he said. Under apartheid, as at Guantanamo, people were held for "unconscionably long periods" and then released, he said.[106]

In 2007, Tutu stated that the global "war on terror" could not be won if people were living in desperate conditions. Tutu said that the global disparity between rich and poor people creates instability.[107]

HIV, AIDS and TB

Tutu's supporters consider him a tireless campaigner for health and human rights, and he has been particularly vocal in support of controlling TB and HIV.[108] He is Patron of the Desmond Tutu HIV Foundation, a registered Section 21 non-profit organisation,[clarification needed] has served as the honorary chairman for the Global AIDS Alliance and is patron of TB Alert, a UK charity working internationally.[109] In 2003 the Desmond Tutu HIV Centre was founded in Cape Town, while the Desmond Tutu TB Centre was founded in 2003 at Stellenbosch University. Tutu suffered from TB in his youth and has been active in assisting those afflicted, especially as TB and HIV/AIDS deaths have become intrinsically linked in South Africa. "Those of you who work to care for people suffering from AIDS and TB are wiping a tear from God’s eye," Tutu said.[108]

On 20 April 2005, after Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger was elected as Pope Benedict XVI, Tutu said he was sad that the Roman Catholic Church was unlikely to change its opposition to condoms amidst the fight against HIV/AIDS in Africa: "We would have hoped for someone more open to the more recent developments in the world, the whole question of the ministry of women and a more reasonable position with regards to condoms and HIV/AIDS."[110]

In 2007, statistics were released that indicated HIV and AIDS numbers were lower than previously thought in South Africa. However, Tutu described these statistics as "cold comfort" as it was unacceptable that 600 people died of AIDS in South Africa every day. Tutu also rebuked the government for wasting time by discussing what caused HIV/AIDS, which particularly attacks Mbeki and Health Minister Manto Tshabalala-Msimang for their denialist stance.[111]

Church reform

In 2002, Tutu called for a reform of the Anglican Communion in regard to how its leader, the Archbishop of Canterbury, is chosen. The ultimate appointment is made by Queen Elizabeth II on the advice of the British Prime Minister, who is in turn selecting from two candidates nominated by the Church of England's nominations commission.

Tutu said that the selection process will be properly democratic and representative only when the link between church and state is broken. In February 2006 Tutu took part in the 9th Assembly of the World Council of Churches, held in Porto Alegre, Brazil.

Bible

Tutu says he reads the Bible every day and recommends that people read it as a collection of books, not a single constitutional document: "You have to understand is that the Bible is really a library of books and it has different categories of material," he said. "There are certain parts which you have to say no to. The Bible accepted slavery. St Paul said women should not speak in church at all and there are people who have used that to say women should not be ordained. There are many things that you shouldn't accept."[112]

Gay rights

In the debate about Anglican views of homosexuality, Tutu has opposed traditional Christian disapproval of homosexuality. Commenting days after the election of Gene Robinson, an openly gay man, to be a bishop in the Episcopal Church in the United States of America on 5 August 2003, Tutu said, "In our Church here in South Africa, that doesn't make a difference. We just say that at the moment, we believe that they should remain celibate and we don't see what the fuss is about."[113] Tutu has remarked that it is sad the church is spending time disagreeing on sexual orientation "when we face so many devastating problems – poverty, HIV/AIDS, war and conflict".[114]

Tutu has increased his criticism of conservative attitudes to homosexuality within his own church, equating homophobia with racism, saying at a conference in Nairobi that he is "deeply disturbed that in the face of some of the most horrendous problems facing Africa, we concentrate on 'what do I do in bed with whom'".[115] In an interview with BBC Radio 4 on 18 November 2007, Tutu accused the church of being obsessed with homosexuality and declared: "If God, as they say, is homophobic, I wouldn't worship that God."[116] Tutu has said that in future anti-gay laws would be regarded as just as wrong as apartheid laws.[117]

Tutu has lent his name to the fight against homophobia in Africa and around the world. He stated at the launching of the book Sex, Love and Homophobia that homophobia is a "crime against humanity" and "every bit as unjust" as apartheid. He added that "we struggled against apartheid in South Africa, supported by people the world over, because black people were being blamed and made to suffer for something we could do nothing about; our very skins... It is the same with sexual orientation. It is a given."[118]

Tutu has been more supportive on recent years of non-celibate gay Christian clergy, praising Gene Robinson and even writing the foreword for his autobiography, In the Eye of the Storm (2008).[119] He said of Robinson: "For someone in the eye of the storm buffeting our beloved Anglican Communion, Gene Robinson is so serene; he is not a wild-eyed belligerent campaigner. I was so surprised at his generosity toward those who have denigrated him and worse. Gene Robinson is a wonderful human being, and I am proud to belong to the same church as he." [sic][120] He also wrote to the Revd Grayde Parsons praising the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.)'s decision to allow non-celibate male and female clergy.[121]

Tutu supported the creation of the Harvey Milk Foundation after being a co-recipient of 2009 Presidential Medal of Freedom with Milk and meeting his nephew, Stuart Milk, who accepted the medal on behalf of his uncle. Tutu remains involved as a founding member of the foundation's advisory board.[122]

In July 2013, Tutu said that he would rather go to hell than a homophobic heaven:[123]

I would refuse to go to a homophobic heaven. No, I would say sorry, I mean I would much rather go to the other place. I would not worship a God who is homophobic and that is how deeply I feel about this. I am as passionate about this campaign as I ever was about apartheid. For me, it is at the same level.

In December 2015, Tutu's daughter, Mpho Tutu married a woman, Marceline Furth.[124]

Women's rights

On 8 March 2009, Tutu joined the "Africa for women's rights" campaign launched by the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH), the African Centre for Democracy and Human Rights Studies (ACDHRS), Femmes Africa Solidarité (FAS), Women's Aid Collective (WACOL), Women in Law and Development in Africa (WILDAF), Women and Law in South Africa (WLSA) and a hundred other African human rights and women's rights organisations. In 2012, to mark the International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women, Desmond Tutu urges men and boys to challenge harmful traditions and protect the rights of girls and women, with this quote: "I call on men and boys everywhere to take a stand against the mistreatment of girls and women. It is by standing up for the rights of girls and women that we truly measure up as men."

Family planning

In 1994, Tutu said that he approved of artificial contraception and that abortion was acceptable in a number of situations, such as incest and rape. He specifically welcomed the aims of the International Conference on Population and Development in Cairo.[125] He accepted the full legalisation of abortion in South Africa, in 1996, despite some personal reservations[126]

Assisted dying

Tutu came out in support of assisted dying on July 2014, stating that life shouldn't be preserved "at any cost". He also said that laws that deny the right to assisted dying deprive those who are dying of their "human right to dignity". He gave the example of Nelson Mandela, whose long and painful illness was in his opinion "an affront to Madiba's dignity". Tutu stated that in a similar situation he would not want to have his own life "prolonged artificially".[127]

Climate change

Tutu was at the 2009 United Nations Climate Change Conference in Copenhagen. He made a speech in front of many at the event. Tutu is also a "Climate Ally" in the "tck tck tck Time for Climate Justice" campaign of the Global Humanitarian Forum and a 350.org messenger.[128] He also helped to lead a rally in 2011 in Durban, South Africa (We Have Faith:Act Now for Climate Justice Rally) in the run up to the COP17 negotiations; where he advocated for all governments to sign a binding document to ensure that climate justice is realised for all people. He has voiced support for fossil fuel divestment and compared it to divestment from South Africa in protest of apartheid.

We must stop climate change. And we can, if we use the tactics that worked in South Africa against the worst carbon emitters... Throughout my life I have believed that the only just response to injustice is what Mahatma Gandhi termed "passive resistance". During the anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa, using boycotts, divestment and sanctions, and supported by our friends overseas, we were not only able to apply economic pressure on the unjust state, but also serious moral pressure.

— Desmond Tutu, [129]

US immigration laws

On 28 April 2011, Tutu published a strongly worded article about Arizona Senate Bill 1070, which criminalises illegal immigration into the US State of Arizona, and requires Arizona police to request immigration documentation of any person suspected of committing a crime, a clause which would require immigrants and citizens to carry documentation on their person at all times. He stated that he was "saddened today at the prospect of a young Hispanic immigrant in Arizona going to the grocery store and forgetting to bring her passport and immigration documents with her. I cannot be dispassionate about the fact that the very act of her being in the grocery store will soon be a crime in the state she lives in. Or that should a policeman hear her accent and form a 'reasonable suspicion' that she is an illegal immigrant, she can – and will – be taken into custody until someone sorts it out, while her children are at home waiting for their dinner." He urged the State of Arizona to create a new model to deal with the pitfalls of illegal immigration, one that "is based on a deep respect for the essential human rights Americans themselves have grown up enjoying."[citation needed]

Iraq War

Tutu has been a staunch opponent since the start of the Iraq War, saying that it has "destabilised and polarised the world to a greater extent than any other conflict in history". In September 2012, Tutu called for George Bush and Tony Blair to be tried for their role in the conflict by the International Criminal Court and that they should be made to "answer for their actions".[130]

Imprisonment of Chelsea Manning

Together with Mairead Maguire and Adolfo Pérez Esquivel, Tutu published a letter in support of Chelsea Manning, saying (in November 2012, nine months prior to Manning coming out as a trans woman in August 2013),

"The words attributed to Manning reveal that he went through a profound moral struggle between the time he enlisted and when he became a whistleblower. Through his experience in Iraq, he became disturbed by top-level policy that undervalued human life and caused the suffering of innocent civilians and soldiers. Like other courageous whistleblowers, he was driven foremost by a desire to reveal the truth" and, "The military prosecution has not presented evidence that Private Manning injured anyone by releasing secret documents... Nor has the prosecution denied that his motivations were conscientious;"[131]

Other humanitarian initiatives

In 2009 Tutu joined the project "Soldiers of Peace", a movie against all wars and for a global peace.[132][133]

Also in 2009, along with prominent chefs and celebrities like Daniel Boulud and Jean Rochefort, Desmond Tutu endorsed Action Against Hunger's No Hunger Campaign calling on the former Vice-President Al Gore to make a documentary film about world hunger.[134]

In 2013, Archbishop Tutu was a mentor for Unreasonable at Sea, a technology business accelerator for social entrepreneurs seeking to scale their ventures in international markets. Founded by Unreasonable Group, Semester at Sea, and Stanford’s Hasso Plattner Institute of Design.[135]

Academic role

In 1998, he was appointed as the Robert R Woodruff Visiting Professor at Emory University, Atlanta. He returned to Emory University the following year as the William R. Cannon Visiting Distinguished Professor. In 2000, he founded the Desmond Tutu Peace Foundation to raise funds for the Desmond Tutu Peace Centre in Cape Town. The following year he launched the Desmond Tutu Peace Foundation USA, which is designed to work with universities nationwide to create leadership academies emphasising peace, social justice and reconciliation.

In 2001, the Desmond Tutu Educational Trust, with funding from the W.K. Kellogg Foundation, launched the Desmond Tutu Footprints of the Legends Awards to recognise leadership in combating prejudice, human rights, research and poverty eradication. In 2003, he taught a course entitled Truth and Reconciliation at the University of North Florida in Jacksonville, Florida, after being asked by adjunct professor Oupa Seane, a friend and activist from South Africa. Since 2004, he has been a visiting professor at King's College London. In 2007, 2010 and 2013, he joined 600 college students and sailed around the world with the Semester at Sea program.[136] Tutu addressed Gonzaga University's Class of 2012 on 13 May 2012 in Spokane, Washington.[137]

Tutu co-chairs 1GOAL Education for All campaign which was launched by Queen Rania of Jordan in August 2009 which aims to secure schooling for some 72 million children world-wide who cannot afford it, in accordance with the Millennium Goal Promise of Education For All by 2015 giving them an opportunity to get education through the FIFA 1Goal campaign.[138][139]

Genome

In the ongoing effort to research the diversity of the human genome, Tutu donated some of his own cells to the project. They were sequenced as an example for a Bantu individual representing Sotho-Tswana and Nguni speakers (publication: February 2010).[140]

Association of European Parliamentarians with Africa

Tutu currently serves as the honorary chair of the Association of European Parliamentarians with Africa's (AWEPA) Eminent Advisory Board.[141]

Honours

On 16 October 1984, the then Bishop Tutu was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. The Nobel Committee cited his "role as a unifying leader figure in the campaign to resolve the problem of apartheid in South Africa".[142] This was seen as a gesture of support for him and The South African Council of Churches which he led at that time. In 1987 Tutu was awarded the Pacem in Terris Award.[143] It was named after a 1963 encyclical letter by Pope John XXIII that calls upon all people of good will to secure peace among all nations.[144] In 1992, he was awarded the Bishop John T. Walker Distinguished Humanitarian Service Award. His 2010 book, Made for Goodness was awarded a Nautilus Book Award.

In June 1999, Tutu was invited to give the annual Wilberforce Lecture in Kingston upon Hull, commemorating the life and achievements of the anti-slavery campaigner William Wilberforce. Tutu used the occasion to praise the people of the city for their traditional support of freedom and for standing with the people of South Africa in their fight against apartheid. He was also presented with the freedom of the city.[145]

In 1978 Tutu was awarded a fellowship of King's College London, of which he is an alumnus. He returned to King's in 2004 as Visiting Professor in Post-Conflict Studies. The Students' Union nightclub, Tutu's, is named in his honour.[146]

In 1996 Tutu was the first recipient of the Archbishop of Canterbury's Award for Outstanding Service to the Anglican Communion, a new award created specially for him, and designated the highest possible award within the Anglican Communion, standing in precedence ahead of the previous highest award, the Cross of St Augustine, gold division.

In November 1999 Tutu was awarded an honorary doctorate by the University of Fribourg.

In June 1999 Tutu was elected an Honorary Fellow of Sidney Sussex College in the University of Cambridge, from which he has been awarded the Honorary Degree of Doctor of Divinity.

In 2006 Tutu was named an honorary patron of the University Philosophical Society, Trinity College, Dublin, for his tremendous contributions to peace and discourse.

Freedom of the city awards have been conferred on Tutu in cities in Italy, Wales, England and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. He has received numerous doctorates and fellowships at distinguished universities. He has been named a Grand Officer of the Légion d'honneur by France; Germany has awarded him the Order of Merit Grand Cross, and he received the Sydney Peace Prize in 1999. He is also the recipient of the Gandhi Peace Prize, the King Hussein Prize and the Marion Doenhoff Prize for International Reconciliation and Understanding. In 2008, Governor Rod Blagojevich of Illinois proclaimed 13 May 'Desmond Tutu Day'. On his visit to Illinois, Tutu was awarded the Lincoln Leadership Prize and unveiled his portrait which will be displayed at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library in Springfield.[147]

In October 2008, Tutu received the Wallenberg Medal from the University of Michigan in recognition of his lifelong work in defence of human rights and dignity.

In November 2008, Tutu was awarded the J. William Fulbright Prize for International Understanding.

On 8 May 2009, Tutu was the featured speaker during Michigan State University's spring undergraduate convocation. During the commencement, an honorary doctor of humane letters degree was bestowed on Tutu. Two days later, he received an honorary doctor of divinity degree from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.[148] The two schools had coincidentally met in the previous month's NCAA Men's Division I Basketball Championship, a detail not missed by Tutu.[149]

In May 2009 Tutu was awarded an honorary Doctor of Divinity degree from the University of Edinburgh.[150] In commemoration of this event the University established the Desmond Tutu Masters' Scholarship for students from Africa to do postgraduate Master's study within the School of Divinity.[151]

Tutu was awarded an honorary degree from Bangor University, Bangor, Wales, on 10 June 2009. During the ceremony, Tutu thanked the people of Wales for their role in helping end apartheid.

On 12 June 2009 the University of Vienna conferred the degree "Doctor Theologiae honoris causa" on Desmond Tutu. The Faculty of Protestant Theology and Senate based the decision on Tutu's outstanding achievement in developing and establishing what can be called "ubuntu-theology", his manifestation of what became known as "public theology". By integrating the principles of the South African ubuntu philosophy with his theological thinking, he made a major contribution beyond classical Liberation Theology.

Southwark Cathedral named two new varieties of rose in honour of Desmond and Leah Tutu at the 2009 RHS Flower Show at Hampton Court Palace. To celebrate the event, the Southwark Cathedral Merbecke Choir gave a concert in the presence of Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu and his wife Leah at Southwark Cathedral on 11 July 2009.[152][153] The Archbishop joined the choir on stage for its encore – an arrangement of George Gershwin's 'Summertime'.

In 2009 he also received the Spiritual Leadership Award from the international Humanity's Team movement[154][155] and the Presidential Medal of Freedom from US President Barack Obama.[156] In 2013 he received the £1.1m ($1.6m) Templeton Prize for "his life-long work in advancing spiritual principles such as love and forgiveness".[157]

Tutu was inducted into the Golden Key International Honour Society as an Honorary Member in 2001, by the University of Stellenbosch.[158]

The Archbishop was named an Honorary Chairman of Building Tomorrow's board of directors. Building Tomorrow engages young people in their mission to build schools for underserved children and communities in Uganda. Tutu has said, "I believe that education is the key to unlocking the door that will eradicate poverty and that young people have the power to make it happen."

World Justice Project

Desmond Tutu serves as an Honorary Co-Chairman for the World Justice Project which works to lead a global, multidisciplinary effort to strengthen the Rule of Law for the development of communities of opportunity and equity.

The Forgiveness Project

Tutu is one of the patrons of The Forgiveness Project,[159] a UK-based charity that uses real stories of victims and perpetrators of crime to facilitate conflict resolution, break the cycle of vengeance and encourage behavioural change. As a supporter of their work,[160] Tutu joined Anita Roddick at the launch of The Forgiveness Project's exhibition, the F Word, at the Oxo Tower Gallery in January 2004 and on 12 May 2010 delivered the charity's inaugural annual lecture.[161]

Speaking to 800 people at St John's Smith Square in London on lecture's topic of "Is violence ever justified?" he talked about the process of truth and reconciliation, the transformative nature of forgiveness and the uniquely African concept of Ubuntu – 'I am me, because you are you', saying that when wars come to an end, only forgiveness enables people to fully move away from conflict.[162]

Archbishop Tutu was joined on stage by Mary Blewitt who lost 50 members of her family in the Rwandan genocide; Jo Berry whose father was killed in the 1984 Brighton hotel bombing; and Patrick Magee, the former IRA activist who planted the bomb. The event was chaired by BBC broadcaster Edward Stourton

Media and film appearances

- I Am, documentary by Tom Shadyac (2010)

- The Late Late Show with Craig Ferguson (for which Ferguson won a Peabody Award) (2009)[163]

- Fierce Light documentary by Velcrow Ripper (2008)

- Iconoclasts Desmond Tutu and Richard Branson (2008)

- I Am Because We Are (2008)

- For the Bible Tells Me So (2007)

- Virgin Radio (2007) – Tutu contacted Virgin Radio on 15 October 2007 in the "Who's Calling Christian" phone in where famous people ring in to raise a substantial amount of money for charity.

- The Foolishness of God: Desmond Tutu and Forgiveness (2007) (post-production)

- Our Story Our Voice (2007) (completed)

- 2006 Trumpet Awards (2006) (TV)

- Nobelity DVD (2006)

- De skrev historie (1 episode, 2005)

- The Shot That Shook the World (2005) (TV)

- The Peace! DVD (2005) (V)

- The Charlie Rose Show (1 episode, 2005)

- Out of Africa: Heroes and Icons (2005) (TV)

- Big Ideas That Changed the World (2005) (mini) TV Series

- Breakfast with Frost (3 episodes, 2004–2005)

- Tavis Smiley (1 episode, 2005)

- The South Bank Show (1 episode, 2005)

- Wall Street: A Wondering Trip (2004) (TV)

- The Daily Show (1 episode, 2004)

- Bonhoeffer (2003)

- Long Night's Journey Into Day (2000)

- Epidemic Africa (1999)

- Cape Divided (1999)

- A Force More Powerful (1999)

- Gimme Hope Jo'anna the 1988 hit single by Eddy Grant, which was banned by the South African Government, mentions Tutu as "The Archbishop who's a peaceful man."

- Tutu the 1986 album by Miles Davis is dedicated to Tutu. The title track, written by Marcus Miller, has become a jazz fusion standard.

Writings

Tutu is the author of seven collections of sermons and other writings:

- Crying in the Wilderness, Eerdmans, 1982. ISBN 978-0-8028-0270-5

- Hope and Suffering: Sermons and Speeches, Skotaville, 1983. ISBN 978-0-620-06776-8

- The Words of Desmond Tutu, Newmarket, 1989. ISBN 978-1-55704-719-9

- The Rainbow People of God: The Making of a Peaceful Revolution, Doubleday, 1994. ISBN 978-0-385-47546-4

- Worshipping Church in Africa, Duke University Press, 1995. ASIN B000K5WB02

- The Essential Desmond Tutu, David Phillips Publishers, 1997. ISBN 978-0-86486-346-1

- No Future without Forgiveness, Doubleday, 1999. ISBN 978-0-385-49689-6

- An African Prayerbook, Doubleday, 2000. ISBN 978-0-385-47730-7

- God Has a Dream: A Vision of Hope for Our Time, Doubleday, 2004. ISBN 978-0-385-47784-0

Tutu has also co-authored or made other contributions to numerous books:

- Bounty in Bondage: Anglican Church in Southern Africa – Essays in Honour of Edward King, Dean of Cape Town, with Frank England, Torguil Paterson, and Torquil Paterson (1989)

- Resistance Art in South Africa, with Sue Williamson (1990)

- The Rainbow People of God, with John Allen (1994)

- Freedom from Fear: And Other Writings, with Václav Havel and Aung San Suu Kyi (1995)

- Reconciliation: The Ubuntu Theology of Desmond Tutu, with Michael J. Battle (1997)

- Exploring Forgiveness, with Robert D. Enright and Joanna North (1998)

- Love in Chaos: Spiritual Growth and the Search for Peace in Northern Ireland, with Mary McAleese (1999)

- Race and Reconciliation in South Africa (Global Encounters: Studies in Comparative Political Theory), with William Vugt and G. Daan Cloete (2000)

- South Africa: A Modern History, with T.R.H. Davenport and Christopher Saunders (2000)

- At the Side of Torture Survivors: Treating a Terrible Assault on Human Dignity, with Bahman Nirumand, Sepp Graessner and Norbert Gurris (2001)

- Place of Compassion, with Kenneth E. Luckman (2001)

- Passion for Peace: Exercising Power Creatively, with Stuart Rees (2002)

- Out of Bounds (New Windmills), with Beverley Naidoo (2003)

- Fly, Eagle, Fly!, with Christopher Gregorowski and Niki Daly (2003)

- Sex, Love and Homophobia: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Lives, with Amnesty International, Vanessa Baird and Grayson Perry (2004)

- Toward a Jewish Theology of Liberation, Marc H. Ellis (2004) (Foreword)

- Radical Compassion: The Life and Times of Archbishop Ted Scott, with Hugh McCullum (2004)

- Third World Health: Hostage to First World Wealth, with Theodore MacDonald (2005)

- Where God Happens: Discovering Christ in One Another and Other Lessons from the Desert Fathers, with Rowan Williams (2005)

- Health, Trade and Human Rights, with Mogobe Ramose and Theodore H. MacDonald (2006)

- The Soul of a New Cuisine: A Discovery of the Foods and Flavors of Africa, with Marcus Samuelsson, Heidi Sacko Walters and Gediyon Kifle (2006)

- The Gospel According to Judas by Benjamin Iscariot, by Jeffrey Archer and Frank Moloney (2007) – Tutu narrates the audiobook version

- Made for Goodness: And Why This Makes All The Difference, with Mpho Tutu (2010), winner of the Nautilus Book Award

- God Is Not A Christian: And Other Provocations, with John Allen (2011)

- The Rise of the Reluctant Innovator (edited by Ken Banks). Foreword. London Publishing Partnership, (2013)

- The Global Guide to Animal Protection (edited by Andrew Linzey). Foreword. (2013)

- The Book of Forgiving (2014) with Rev Mpho Tutu (his daughter)

Tutu has also written articles for Greater Good, a magazine published by the Greater Good Science Center of the University of California, Berkeley. His contributions include the interpretation of scientific research into the roots of compassion, altruism and peaceful human relationships.

A British children's author, Nick Butterworth, dedicated his book The Whisperer to Tutu.

See also

References

- ^ "Tutu to be honoured with Gandhi Peace Award". Retrieved 11 November 2008.

- ^ Miller, Lindsay. "Desmond Tutu – A Man with a Mission". Archived from the original on 30 September 2006. Retrieved 1 June 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Aarvik, Egil (1984). "Presentation Speech of 1984 Nobel Prize for Peace". The Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 1 June 2008.

- ^ Gish, Steven (2004). Desmond Tutu. A Biography. Greenwood Press. doi:10.1336/0313328609. ISBN 978-0-313-32860-2.

- ^ "Our Patron – Archbishop Desmond Tutu". Cape Town Child Welfare. Retrieved 6 June 2008.

- ^ "Tutu House". blueplaques.co.za. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- ^ "Vilakazi Street under siege – by snakes". Daily Star. 22 January 2013. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ^ a b "Trevor Tutu freed from prison after being granted amnesty". SAPA. 28 November 1997. Retrieved 1 June 2008.

- ^ "South Africa: Amnesty From Truth Commission Evokes Harsh Criticism". All Africa. 8 December 1997. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Sarkin, Jeremy (2004). Carrots and Sticks: The Trcc and the South African Amnesty Process. Page 19: Intersentia. p. 441. ISBN 9050954006.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ "Tutu's son in amnesty bid". Dispatch. 27 September 1997. Retrieved 1 June 2008.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Naomi Tutu's interview after College of Wooster workshop reveals her authenticity". The Daily Record. 3 February 2013. Retrieved 22 September 2013.

- ^ "Reverend Mpho Tutu". 2004 Women of Distinction. 2004. Retrieved 1 June 2008.

- ^ "The Reverend Mpho A. Tutu". Tutu Institute. Archived from the original on 23 July 2008. Retrieved 1 June 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Taking the fight against prostate cancer to South Africans" (Press release). Prostate Cancer Foundation of South Africa. 3 March 2007. Retrieved 23 April 2008.

- ^ St. John's High School – Desmond Tutu at Saint John's. Stjohnshigh.org (23 May 2011). Retrieved 8 September 2011.

- ^ Truax, Tabitha (12 September 2013). "Butler Offers Tutu Up as Living Relic, Rather Than Leader". Global Indy.

- ^ Hyer, Marjorie (24 December 1984). "Tutu Urges U.S. Action". Washington Post. p. C1.

- ^ Wood, Lawrence (17 October 2006). "Tutu's story". The Christian Century. Retrieved 4 April 2008.

- ^ Tutu, Desmond (1994). The Rainbow People of God: The Making of a Peaceful Revolution. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-47546-2.

- ^ Carlin, John (12 November 2006). "Former aide John Allen's authorised biography offers an intimate view of Desmond Tutu". The Observer. UK. Retrieved 4 April 2008.

- ^ "No. 54002". The London Gazette. 7 April 1995.

- ^ (1 June 2009): Tutu in Hay appeal for Zimbabwe. BBC News (28 May 2009). Retrieved 8 September 2011.

- ^ a b "Fact Sheet: Archbishop Desmond Mpilo Tutu". Racism. No Way. 19 January 2006. Retrieved 1 June 2008.

- ^ "Tutu calls for child registration". BBC. 22 February 2005. Retrieved 23 January 2008.

- ^ "Nobel Laureates". PeaceJam Foundation. PeaceJam Foundation. Retrieved 3 September 2015.

- ^ "South Africa's Tutu Announces Retirement.". CNN. Retrieved 8 September 2011.

- ^ a b c "Archbishop Desmond Tutu lambasts African silence on Zimbabwe". USA Today. 16 March 2007. Retrieved 4 April 2008.

- ^ Tutu, Mbeki & others (2005). "Controversy: Tutu, Mbeki & the freedom to criticise". Centre for Civil Society.

- ^ "South Africa's Desmond Tutu: 'I will not vote for ANC'". BBC News. 10 May 2013. Retrieved 5 June 2013.

- ^ Chothia BBC South Africa analyst, Farouk (17 December 2013). "Archbishop Tutu: Nelson Mandela services excluded Afrikaners". BBC News. BBC. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- ^ "Desmond Tutu changes mind, going to Mandela funeral - World - CBC News". Cbc.ca. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- ^ a b "Tutu warns of poverty 'powder keg'". BBC. 23 November 2004.

- ^ Maclennan, Ben (2 December 2004). "Quotes of the Week". Sapa.

- ^ Carlin, John. "Interview with Tutu". PBS Frontline. Retrieved 7 September 2006.

- ^ "S Africa is losing its way – Tutu". BBC. 27 September 2006.

- ^ "Tutu Warns of 'Assault' on Democracy". msn news. SAPA. 27 November 2013. Retrieved 27 November 2013.

- ^ Press statement Desmond Tutu[dead link]

- ^ "Zuma camp lashes out at 'old' Tutu". Mail & Guardian. 1 September 2006. Retrieved 1 September 2006.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Nelson Mandela and Desmond Tutu announce The Elders". TheElders.org. 18 July 2007. Retrieved 11 March 2013.

- ^ "Kofi Annan appointed Chair of The Elders". TheElders.org. 10 May 2013. Retrieved 23 May 2013.

- ^ "Muhammad Yunus steps down". TheElders.org. 21 September 2009. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- ^ "The Elders congratulate Aung San Suu Kyi ahead of her appearance in parliament in Burma/Myanmar". TheElders.org. 19 April 2012. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- ^ "The Elders: Our Work". TheElders.org. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- ^ "Tutu denounces rights abuses". News24. 10 December 2007. Retrieved 11 March 2013.

- ^ "Desmond Tutu". TheElders.org. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- ^ "The Elders to turn spotlight on neglected issue of child marriage". TheElders.org. 16 September 2011. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- ^ "The Elders: Donors". TheElders.org. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- ^ Thornycroft, Peta; Berger, Sebastien (19 September 2007). "Zimbabwe needs your help, Tutu tells Brown". The Daily Telegraph. UK. Retrieved 4 April 2008.

- ^ "Tutu urges Zimbabwe intervention". BBC. 29 June 2008.

- ^ Allen, John (10 October 2007). "Working with a rabble-rouser". The Times. UK. Retrieved 22 January 2008.

- ^ a b c "'Mugabe must step down with dignity'". The Times. UK. 2 April 2008. Retrieved 4 April 2008.

- ^ "Solomon Islands gets Desmond Tutu truth help", The Australian, 29 April 2009

- ^ "Archbishop Tutu to Visit Solomon Islands", Solomon Times, 4 February 2009

- ^ "Solomons Truth and Reconciliation Commission launched". Radio New Zealand International. 29 April 2009. Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- ^ a b c d Tutu, Desmond (29 April 2002). "Apartheid in the Holy Land". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 28 November 2006.MOS

- ^ "Article Details". Acjna.org. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- ^ Tutu, Desmond; Urbina, Ian (27 June 2002). "Israeli apartheid". The Nation (275): 4–5. Retrieved 28 November 2006.

- ^ Ruby, Walter (1 February 1989). "Tutu says Israel's policy in territories remind him of SA". Jerusalem Post.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Tutu condemns Israeli apartheid". BBC. 29 April 2002. Retrieved 28 November 2006.

- ^ Shimoni, Gideon (1988). "South African Jews and the Apartheid Crisis" (PDF). American Jewish Year Book. 88. American Jewish Committee: 50.

- ^ Barthos, Gordon (20 December 1989). "Israelis uneasy about Tutu's Yule visit". Toronto Star.

- ^ a b "Tutu Urges Jews to Forgive The Nazis". San Francisco Chronicle. 27 December 1989.

- ^ "Tutu assailed". Chicago Sun-Times. 30 December 1989. p. 13.

- ^ "ADL Blasts Appointment of Desmond Tutu As Head of U.N. Fact Finding Mission To Gaza" (Press release). Anti-Defamation League. 2006. Retrieved 4 October 2007.

- ^ Phillips, Melanie (6 May 2002). "Bigotry and a corruption of the truth". Daily Mail. UK.

- ^ Tutu, Desmond (forward) (2005). Prior, Michael (ed.). Speaking the Truth: Zionism, Israel, and Occupation. Olive Branch Press. p. 12.

- ^ "Tutu slammed at racism conference – World News". Independent Newspapers Online. IOL.co.za. 20 April 2009. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

- ^ [1] "Global March 2 Jerusalem – South African Personalities". Retrieved 16 March 2012.

- ^ "Global March to challenge the 'Judaization' of Jerusalem". Mondoweiss.net. 22 February 2012.

- ^ "Desmond Tutu lends his name to Sabeel". comeandsee.com. 18 June 2003. Retrieved 4 December 2006.

- ^ "A call for morally responsible investment: A Nonviolent Response to the Occupation" (PDF). Sabeel. April 2005. Retrieved 3 October 2007.

- ^ "Tutu Honor Too Too Much?". Jewish Week.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Derfner, Larry (15 October 2006). "Anti-Semite and Jew". Jerusalem Post. p. 15.

- ^ "BBC NEWS | Middle East | Tutu: Gaza blockade abomination". BBC News. 29 May 2008. Retrieved 31 October 2010.

- ^ Boycotts and Protests To Meet APA Keynote Speaker, Desmond Tutu. Psychiatric Times. Retrieved 8 September 2011.

- ^ Pittsburgh psychiatrist opposed to Desmond Tutu speech at national meeting. The Jewish Chronicle. Retrieved 8 September 2011.

- ^ "Controversy surrounds Tutu's isle appearance". Honolulu Star Advertiser. (12 May 2011). Retrieved 8 September 2011.

- ^ Furst, Randy (4 October 2007). "St. Thomas won't host Tutu". Minneapolis Star Tribune.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Furst, Randy (15 October 2007). "St. Thomas urged to reconsider its decision not to invite Tutu". Minneapolis Star Tribune. Retrieved 7 October 2007.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "UST president says he made wrong decision, invites Tutu to campus". University of St. Thomas Bulletin. Archived from the original on 13 October 2007. Retrieved 7 October 2007.

- ^ Mador, Jessica (12 April 2008). "Desmond Tutu avoids politics while talking about peace". Minnesota Public Radio. Retrieved 6 May 2008.

- ^ Minor, Nathaniel (17 July 2009). "Tutu talks at Metro State". The Aquin, St. Thomas' student newspaper. Retrieved 17 July 2009.

- ^ Yang Jianli's Meeting with Archbishop Desmond Tutu in Boston.

- ^ Now Archbishop Desmond Tutu urges boycott of Beijing Olympics over China's failure to act in Darfur. Daily Mail. 14 February 2008

- ^ Tutu, Desmond. Statement on Tibet and China. Washington Post, 25 March 2008

- ^ "San Francisco set for torch relay". BBC. 9 April 2008. Retrieved 9 April 2008.

- ^ Was South Africa right to deny Dalai Lama a visa? 4 October 2011

- ^ Dalai Lama criticises China in South Africa video link bbc 8 October 2011

- ^ "Amnesty International welcomes the election of a Board of Directors". Amnesty International. 12 September 2003. Retrieved 1 August 2007.

- ^ "Desmond Tutu turns 75". News24. 6 October 2006. Retrieved 22 January 2008.

- ^ "Statement by Archbishop Desmond Tutu, South Africa". West Papuan Action. 23 February 2004. Retrieved 6 June 2008.

- ^ Slosberg, Jacob (29 November 2006). "Tutu to head UN rights mission to Gaza". Jerusalem Post.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Hoffman, Gil; Keinon, Herb (19 December 2006). "Israel may give no-no to Tutu's trip to Beit Hanun". Jerusalem Post.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Desmond Tutu says Israel refused fact-finding mission to Gaza". International Herald Tribune. 11 December 2006.

- ^ "Tutu heads for Gaza Strip". News24. 26 May 2008. Retrieved 31 May 2008.

- ^ "Archbishop Tutu calls for G8 help". BBC. 17 March 2005. Retrieved 23 January 2008.

- ^ "Desmond Tutu: Keep your Promises" (Press release). World Aids Campaign. 19 October 2006. Retrieved 4 April 2008.

- ^ "Tutu condemns Blair's Iraq stance". BBC. 5 January 2003. Retrieved 23 January 2008.

- ^ Hope, Christopher (28 August 2012). "Archbishop Desmond Tutu pulls out of event with Tony Blair because of Iraq War". telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 28 August 2012.

- ^ Tutu, Desmond (2 September 2012). "Why I had no choice but to spurn Tony Blair". The Observer. Retrieved 2 September 2012.

- ^ Spector, J. Brooks (31 August 2012). "Discovering Tony Blair". DailyMaverick.co.za. Retrieved 2 September 2012.

- ^ Cole, Juan (2 September 2012). "Tutu Slams Tony Blair for Illegal Iraq War, Boycotts Leadership Conference". Informed Comment. Retrieved 2 September 2012.

- ^ Cooke, Jeremy (2 October 2004). "Tutu in anti-Guantanamo theatre". BBC. Retrieved 23 January 2008.

- ^ "Tutu calls for Guantanamo release". BBC. 12 January 2005. Retrieved 22 January 2008.

- ^ "Tutu calls for Guantanamo closure". BBC. 17 February 2006. Retrieved 22 January 2008.

- ^ "Tutu: Poverty fuelling terror". CNN. 16 September 2007. Retrieved 4 April 2008.

- ^ a b "Archbischop Desmond Tutu urges TB/HIV workers to continue to relieve suffering from dual scourges". Desmond Tutu HIV Centre. 28 September 2005. Archived from the original on 19 July 2008. Retrieved 24 April 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ TB Alert website. Tbalert.org (23 January 2009). Retrieved 8 September 2011.

- ^ "Africans hail conservative Pope". BBC News. 20 April 2005. Retrieved 26 May 2006.

- ^ "Aids stats 'cold comfort'- Tutu". News24. 30 November 2007. Retrieved 4 April 2008.

- ^ "Tutu urges leaders to agree climate deal". CNN. 15 December 2009. Retrieved 15 December 2009.

- ^ "Desmond Tutu: gay bishop row is just "fuss"". Gay.com UK. 11 August 2006. Retrieved 26 May 2006.

- ^ "Tutu calls on Anglicans to accept gay bishop". Spero News. 14 November 2005. Retrieved 26 May 2006.

- ^ "Tutu stands up for gays". Pink News. 19 January 2007.

- ^ "Desmond Tutu chides Church for gay stance". BBC. 18 November 2007.

- ^ Desmond Tutu: Anti-gay laws ‘as wrong as apartheid’. Retrieved 21 July 2012

- ^ Baird, Vanessa; Tutu, Desmond, Archbishop (foreword); Perry, Grayson (Preface): Sex, Love and Homophobia, foreword, Amnesty International, 2004.

- ^ "2008, English, Book edition: In the eye of the storm / Gene Robinson ; foreword by Desmond Tutu. Robinson, V. Gene, 1947–". Trove.nla.gov.au. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- ^ "Event Detail". Lincoln.org. 18 April 2013. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- ^ "Archbishop Tutu praises the PCUSA, 12 October 2011". Covnetpres.org. 12 October 2011. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- ^ "Harvey Milk Foundation – Advisory Board". Harvey Milk Foundation. Retrieved 31 March 2011.

- ^ "Archbishop Tutu 'would not worship a homophobic God'". British Broadcasting Company. 26 July 2013.