Erivan Fortress

| Erivan Fortress | |

|---|---|

| Left bank of Hrazdan River (in the place of Ararat Wine Factory) | |

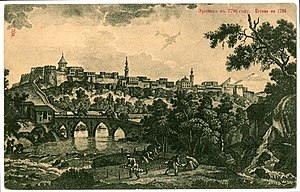

View of Erivan in 1796 by G. Sergeevich. | |

| Site information | |

| Condition | Demolished |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1582–83[1] |

| In use | Erivan Sardars' seat (until 1827) Armenian Oblast Governor's(1828–40) Erivan Governorate's Governor (1850–64) |

| Demolished | 1860s–1930s [clarification needed] |

| Battles/wars | Turkish-Persian War, 1623-39 Turkish-Persian War, 1722-27 Turkish-Persian War, 1730-36 Russo-Persian War, 1826-28 |

Erivan Fortress (Template:Lang-hy; Yerevani berdë; Template:Lang-fa, Ghaleh-ye Iravân; Template:Lang-az – ايروان قالاسى; Template:Lang-ru E'rivanskaya krepost' ) was a 16th-century fortress in Yerevan.

History

The fortress was built during the Ottoman rule in 1582–83 by Ferhat Pasha.[1][2][3] The fortress was destroyed by an earthquake in 1679. After the earthquake, the ruler of Erivan Zal Khan asked the Shah for help to rebuild Erivan, including the fortress and the Palace of the Sardars.

On 12 July 1679, the vice-regent of the Persian province of Azerbaijan, Mirza Ibrahim, visited Erivan. He was directed to recover the fortress, the seat of the Khan of Erivan. Many villagers from Ganja, Agulis and Dasht (Nakhchivan) were moved to Erivan to rebuild the fortress. The forced labor continued until winter. Later, the Shah allowed everyone to return to their homes. The reconstruction of the Erivan Fortress was not finished. It was continued and finished in the following years. In October 1827, during the Russo-Persian War of 1826–1829, the Russian army by the leadership of Ivan Paskevich captured Erivan and the Erivan Fortress was not used for military purposes since then, until its complete destruction in 1930s. [citation needed]

In 1853, the fortress was ruined by another earthquake. In 1865 the territory of the fortress was purchased by Nerses Tairyants, a merchant of the first guild.[3] Later in 1880s, Tairyants built a brandy factory in the northern part of the fortress. The fortress was completely demolished in 1930s during the Soviet reign, although some parts of the defensive walls still remain.[4]

Description

The Erivan Fortress was considered to be a small town separate from the city. It was separated from the city with large and unwrought space. The fortress was rectangular with a perimeter of about 1,200 metres (4,000 ft). It was walled on three sides; on the fourth (western) it was flanked by the Zangu River gorge. The gorge on the north-western part of the fortress had a depth of 300 sazhen (640 meters). As it was considered inaccessible it was not walled. The earth mound was considered as a wall. [citation needed]

The Erivan Fortress had three gateways on its double line battlements: Tabriz, Shirvan and Korpu. The walls had towers like old eastern castles. Each wall had an iron gate, and each one had its guard. The garrison had about 2,000 soldiers. There were 800 houses inside the fortress. The permanent residents of the fortress were local Muslims only. Although Armenians were allowed to work in the markets during the day, they had to lock up and return to their homes in Shahar (the main town) at night. [citation needed]

Interior

Sardar's Palace

The palace was in the north-western part of the fortress. The palace hanged on the Hrazdan gorge. It was a square wide building with many sections. The harem was one of the biggest sections, it was 61 metres (200 ft) long and 38 metres (125 ft) wide. It was divided into many rooms and corridors. This palace was built in 1798 during the reign of Huseyn-Ali khan's son, Mahmud. [5]

All palaces built previously had been destroyed whenever the khans built a new one. The last was built in 1798 in Persian architectural style, containing "Shushaband-ayva" ("A Hall of Mirrors"), whose cornice was covered with colorful glass. The ceiling was decorated by the pictures of sparkling flowers. And in the walls of the hall were eight images drawn on the canvas: Fat′h-Ali Shah, Huseyn-Ghuli and Hasan, Abbas Mirza, Faramarz, etc.[6][7]

After the capture of Erivan by the Russians, in one of the halls of the palace, Aleksandr Griboyedov's famous comedy, Woe from Wit, was performed by the military garrison with stand by of the author. A marble memorial plaque which commemorates the performance is in the Yerevan Ararat Wine Factory, which currently occupies the location where the fortress once existed.[8]

-

The interior of the Saradar Palace

-

Interior of the Kiosque of the Sirdars

-

A detail of wall decoration of the Sardar Palace, 1828, by an Azerbaijani artist Mirza Gadim Iravani

Harem and the bath

The inner walls of khan's harem were covered by marble, with colorful patterns. There was a swimming pool (measurements were 15 sazhen (32 meters) in length, 4 sazhen (9 meters) in width and 3 arshin (2,1 meters) in depth).[9]

Mosques

There were two Persian mosques inside the Erivan Fortress. One was Rajab-Pasha Mosque; the other was Abbas Mirza Mosque. The ruins of Rajab-Pasha Mosque remained until the beginning of the works of reconstruction of Erivan in 1930s. Only one wall of Abbas Mirza Mosque remains standing. [citation needed]

Rajab-Pasha Mosque

This mosque was built in 1725 during the reign of Turkish Rajab-Pasha khan. It was a 4-columned arched big building with beautiful exterior. During the Persian rule it was used as an arsenal, because it was a Sunni mosque, and the new owners, the Persians, were Shia Muslims. In 1827, this mosque was converted to a Russian Orthodox church, and named after the Holy Virgin.[10]

Abbas Mirza Mosque (Sardar's Mosque)

This mosque was Shia and was built in the beginning of the nineteenth century, during the reign of the last khan of Erivan Khanate Huseyn-khan. [clarification needed] It was a Shia mosque, called “Abbas Mirza Jami”, named for the son of Huseyn-khan. The façade was covered by green and blue glass, usually found in Azeri-Iranian[citation needed]-style architecture. After the capture of Erivan by the Russians, the mosque was used as an arsenal.[11][12][13][14][15] During Soviet times the mosque, along with other religious structures (Armenian churches, temples and monasteries) was derelict and currently only the frame of the mosque has been preserved.[16][17]

See also

References

- ^ a b Template:Hy icon ԵՐԵՎԱՆ ՔԱՂԱՔԻ ՊԱՏՄՈՒԹՅԱՆ ԵՎ ՄՇԱԿՈՒՅԹԻ ԱՆՇԱՐԺ ՀՈՒՇԱՐՁԱՆՆԵՐԻ ՊԵՏԱԿԱՆ ՑՈՒՑԱԿ (State List of the Immovable Historical and Cultural Monuments of the City of Yerevan)

- ^ Arutyunyan, V. “Yerevan”, Moscow, 1968, p. 18

- ^ a b History of the Erivan Fortress

- ^ Template:Hy icon Բերդերը

- ^ Hovhannes Shahkhatunyants, Ստորագրութիւն Կաթուղիկէ Էջմիածնի և հինգ գաւառացն Արարատայ, vol 2, p. 52

- ^ Template:Ru icon Прикосновение к истории

- ^ Template:Hy icon T. Kh. Hakobyan, The History of Yerevan (Երևանի պատմությունը (1801 — 1879 թթ.)), pp. 240-42

- ^ Հայրենագիտական Էտյուդներ (in Armenian). Yerevan: «Սովետական գրող». 1979. pp. 283–84.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Template:Ru icon I. Chopin, Historical monuments of the Armenian Oblast (Исторический памятник Армянской области), p. 867

- ^ Template:Hy icon Hakobyan, Tadevos. ԵՐԵՎԱՆԻ ՊԱՏՄՈՒԹՅՈՒՆԸ (1500–1800 ԹԹ. (English: History of Yerevan (1500-1800), 1979, Yerevan State University. p. 370

- ^ Chopin, Historical monuments of the Armenian oblast (Исторический памятник Армянской области), p. 867

- ^ Template:Hy icon Gevont Alishan, Ayrarat. (Այրարատ), p. 311

- ^ Lynch, Harry F.B. Armenia, travels and studies, volume 1, Longman, Green & Co., 1901, Harvard University, p. 283

- ^ Template:Hy icon Shahaziz, Yervand. Old Yerevan (Հին Երևանը), pp. 34-35, 182

- ^ Template:Hy icon Adamyants, Adam. Topography of Yerevan (Տեղագրութիւն Երեւանի), Yerevan, 1889, pp. 38-39

- ^ European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages (ECRML) report for Armenia

- ^ Website of the Government of the Republic of Armenia