Gregory Peck

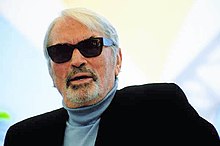

Gregory Peck | |

|---|---|

Publicity photo, 1948 | |

| Born | Eldred Gregory Peck April 5, 1916 San Diego, California, United States |

| Died | June 12, 2003 (aged 87) Los Angeles, California, United States |

| Cause of death | Bronchopneumonia |

| Resting place | Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels, Los Angeles, California |

| Education | St. John's Military Academy, Los Angeles La Jolla High School |

| Alma mater | San Diego State University University of California, Berkeley |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1942–2000 |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse | Greta Kukkonen (1942–55; divorced) Veronique Passani (1955–2003; his death) |

| Children | 5, including Cecilia Peck |

| Family | Ethan Peck (grandson) |

Eldred Gregory Peck (April 5, 1916 – June 12, 2003) was an American actor who was one of the most popular film stars from the 1940s to the 1960s. Peck continued to play major film roles until the late 1970s. His performance as Atticus Finch in the 1962 film To Kill a Mockingbird earned him the Academy Award for Best Actor. He had also been nominated for an Oscar for the same category for The Keys of the Kingdom (1944), The Yearling (1946), Gentleman's Agreement (1947) and Twelve O'Clock High (1949). Other notable films he appeared in include Spellbound (1945), The Paradine Case (1947), Roman Holiday (1953), Moby Dick (1956, and its 1998 miniseries), The Guns of Navarone (1961), Cape Fear (1962, and its 1991 remake), How the West Was Won (1962), The Omen (1976) and The Boys from Brazil (1978).

President Lyndon Johnson honored Peck with the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1969 for his lifetime humanitarian efforts. In 1999, the American Film Institute named Peck among Greatest Male Stars of Classic Hollywood cinema, ranking at No. 12. He was named to the International Best Dressed List Hall of Fame in 1983.[1]

Early life

Eldred Gregory Peck was born on April 5, 1916, in the San Diego, California, neighborhood of La Jolla, the son of Gregory Pearl Peck, a New York-born chemist and pharmacist, and his Missouri-born wife Bernice Mary "Bunny" (née Ayres).[2] His father was of English (paternal) and Irish (maternal) heritage,[3][4] while his mother had English and Scottish ancestry.[5] Peck's father was Roman Catholic, while his mother converted to Roman Catholicism when she married his father. Through his Irish-born paternal grandmother Catherine Ashe, Peck was related to Thomas Ashe, who took part in the Easter Rising less than three weeks after Peck's birth and died while on hunger strike in 1917. Peck's parents divorced by the time he was six years old; his maternal grandmother raised him for the next few years.[6]

Peck attended a Catholic military school, St. John's Military Academy in Los Angeles, at the age of 10. His grandmother died while he was enrolled there, and his father again took over his upbringing. At 14, Peck attended San Diego High School and lived with his father.[7] When he graduated, he enrolled briefly at San Diego State Teacher's College, (now known as San Diego State University), joined the track team, took his first theatre and public-speaking courses, and joined the Epsilon Eta fraternity.[8] He stayed for just one academic year, thereafter obtaining admission to his first-choice college, the University of California, Berkeley.[9] For a short time, he took a job driving a truck for an oil company. In 1936, he declared himself a pre-medical student at Berkeley, and majored in English. Standing 6 ft 3 in (1.91 m), he rowed on the university crew.

The Berkeley acting coach saw Peck as perfect material for university theater. Peck developed an interest in acting and was recruited by Edwin Duerr, director of the university's Little Theater. He appeared in five plays during his senior year. Although his tuition fee was only $26 per year, Peck still struggled to pay, and had to work as a "hasher" (kitchen helper) for the Gamma Phi Beta sorority in exchange for meals. Peck would later say about Berkeley that, "it was a very special experience for me and three of the greatest years of my life. It woke me up and made me a human being."[10] In 1997, Peck donated $25,000 to the Berkeley rowing crew in honor of his coach, the renowned Ky Ebright.

Acting career

Stage

After graduating from Berkeley with a BA degree in English, Peck dropped the name "Eldred" and headed to New York City to study at the Neighborhood Playhouse with the legendary acting teacher Sanford Meisner. He was often broke and sometimes slept in Central Park.[11] He worked at the 1939 World's Fair and as a tour guide for NBC's television broadcasting. In 1940, Peck learned more of the acting craft, working in exchange for food, at the Barter Theatre in Abingdon, Virginia, appearing in five plays including Family Portrait and On Earth As It Is.[12]

His stage career began in 1941 when he played the secretary in a Katharine Cornell production of George Bernard Shaw's play The Doctor's Dilemma. Unfortunately, the play opened in San Francisco just one week before the attack on Pearl Harbor.[13] He made his Broadway debut as the lead in Emlyn Williams' The Morning Star in 1942. His second Broadway performance that year was in The Willow and I with Edward Pawley. Peck's acting abilities were in high demand during World War II because he was exempt from military service owing to a back injury suffered while receiving dance and movement lessons from Martha Graham as part of his acting training. Twentieth Century Fox claimed he had injured his back while rowing at university, but in Peck's words, "In Hollywood, they didn't think a dance class was macho enough, I guess. I've been trying to straighten out that story for years."[14]

In 1947, Peck co-founded The La Jolla Playhouse, at his birthplace, with Mel Ferrer and Dorothy McGuire.[15] This local community theater and landmark (now in a new home at the University of California, San Diego) still thrives today. It has attracted Hollywood film stars on hiatus both as performers and enthusiastic supporters since its inception.

Film

Peck's first film, Days of Glory, was released in 1944. He was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actor five times, four of which came in his first five years of film acting: for The Keys of the Kingdom (1944), The Yearling (1946), Gentleman's Agreement (1947), and Twelve O'Clock High (1949).

The Keys of the Kingdom emphasized his stately presence. As the farmer Ezra "Penny" Baxter in The Yearling, his good-humored warmth and affection toward the characters playing his son and wife confounded critics who had been insisting he was a lifeless performer. Duel in the Sun (1946) showed his range as an actor in his first "against type" role as a cruel, libidinous gunslinger. Gentleman's Agreement established his power in the "social conscience" genre in a film that took on the deep-seated but subtle antisemitism of mid-century corporate America. Twelve O'Clock High was the first of many successful war films in which Peck embodied the brave, effective, yet human fighting man.

Among his other films were Spellbound (1945), The Paradine Case (1947), The Gunfighter (1950), Moby Dick (1956), The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit (1956), On the Beach (1959), which brought to life the terrors of global nuclear war, The Guns of Navarone (1961), and Roman Holiday (1953), with Audrey Hepburn in her Oscar-winning role. Peck and Hepburn were close friends until her death; Peck even introduced her to her first husband, Mel Ferrer. Peck once again teamed up with director William Wyler in the epic Western The Big Country (1958), which he co-produced.

Peck won the Academy Award with his fifth nomination, playing Atticus Finch, a Depression-era lawyer and widowed father, in a film adaptation of the Harper Lee novel To Kill a Mockingbird. Released in 1962 during the height of the US civil rights movement in the South, this film and his role were Peck's favorites. In 2003, Peck's portrayal of Atticus Finch was named the greatest film hero of the past 100 years by the American Film Institute.[16]

Peck's sober style seemed out of place in the 1960s.[17] He served as the president of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in 1967, Chairman of the Board of Trustees of the American Film Institute from 1967 to 1969, Chairman of the Motion Picture and Television Relief Fund in 1971, and National Chairman of the American Cancer Society in 1966. He was a member of the National Council on the Arts from 1964 to 1966.[18]

A physically powerful man, he was known to do a majority of his own fight scenes, rarely using body or stunt doubles. In fact, Robert Mitchum, his on-screen opponent in Cape Fear, told about the time Peck once accidentally punched him for real during their final fight scene in the movie. He felt the impact for days afterward. Peck's rare attempts at villainous roles were not acclaimed. Early on, he played the renegade son in the Western Duel in the Sun and, later in his career, the infamous Nazi doctor Josef Mengele in The Boys from Brazil co-starring Laurence Olivier.[19]

Later work

In the 1980s, Peck moved to television, where he starred in the mini-series The Blue and the Gray, playing Abraham Lincoln. He also starred with Christopher Plummer, John Gielgud, and Barbara Bouchet in the television film The Scarlet and The Black, about Monsignor Hugh O'Flaherty, a real-life Catholic priest in the Vatican who smuggled Jews and other refugees away from the Nazis during World War II.

Peck, Mitchum, and Martin Balsam all had roles in the 1991 remake of Cape Fear directed by Martin Scorsese. All three were in the original 1962 version. In the remake, Peck played Max Cady's lawyer.

His last prominent film role also came in 1991, in Other People's Money, directed by Norman Jewison and based on the stage play of that name. Peck played a business owner trying to save his company against a hostile takeover bid by a Wall Street liquidator played by Danny DeVito.

Peck retired from active film-making at that point. Peck spent the last few years of his life touring the world doing speaking engagements in which he would show clips from his movies, reminisce, and take questions from the audience. He did come out of retirement for a 1998 miniseries version of one of his most famous films, Moby Dick, portraying Father Mapple (played by Orson Welles in the 1956 version), with Patrick Stewart as Captain Ahab, the role Peck played in the earlier film. It would be his final performance, and it won him the Golden Globe for Best Supporting Actor in a Series, Miniseries or Television Film.

Peck had been offered the role of Grandpa Joe in the 2005 film Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, but died before he could accept it. The Irish actor David Kelly was then given the part.[20]

Politics

In 1947, while many Hollywood figures were being blacklisted for similar activities, Peck signed a letter deploring a House Un-American Activities Committee investigation of alleged communists in the film industry.

A lifelong supporter of the Democratic Party, Peck was suggested in 1970 as a possible Democratic candidate to run against Ronald Reagan for the office of California Governor. Although he later admitted that he had no interest in being a candidate himself for public office, Peck encouraged one of his sons, Carey Peck, to run for political office. Carey was defeated both times by slim margins in races in 1978 and 1980 against Republican U.S. Representative Bob Dornan, another former actor.

In an interview with the Irish media, Peck revealed that former President Lyndon Johnson had told him that, had he sought re-election in 1968, he intended to offer Peck the post of U.S. ambassador to Ireland – a post Peck, owing to his Irish ancestry, said he might well have taken, saying "[It] would have been a great adventure".[21] The actor's biographer Michael Freedland substantiates the report and says that Johnson indicated that his presentation of the Medal of Freedom to Peck would perhaps make up for his inability to confer the ambassadorship.[22] President Richard Nixon, though, placed Peck on his enemies list owing to his liberal activism.[23]

Peck was outspoken against the Vietnam War, while remaining supportive of his son, Stephen, who fought there. In 1972, Peck produced the film version of Daniel Berrigan's play The Trial of the Catonsville Nine about the prosecution of a group of Vietnam protesters for civil disobedience. Despite his reservations about American general Douglas MacArthur as a man, Peck had long wanted to play him on film, and did so in MacArthur in 1976.[24]

In 1978, Peck traveled to Alabama, the setting of To Kill a Mockingbird, to campaign for Democratic U.S. Senate nominee Donald W. Stewart of Anniston, who defeated the Republican candidate, James D. Martin, a former U.S. representative from Gadsden.

In 1987, Peck undertook the voice-overs for television commercials opposing President Reagan's Supreme Court nomination of conservative judge Robert Bork.[25] Bork's nomination was defeated. Peck was also a vocal supporter of a worldwide ban of nuclear weapons, and a lifelong advocate of gun control.[26][27]

Personal life and death

In October 1942, Peck married Finnish-born Greta Kukkonen (1911–2008), with whom he had three sons, Jonathan (1944–1975), Stephen (b. 1946), and Carey Paul (b. 1949). They were divorced on December 30, 1955.

During his marriage with Greta, Peck had a brief affair with Spellbound costar Ingrid Bergman.[28] He confessed the affair to Brad Darrach of People in a 1987 interview, saying "All I can say is that I had a real love for her (Bergman), and I think that's where I ought to stop... I was young. She was young. We were involved for weeks in close and intense work." [29][30][31]

On December 31, 1955, the day after his divorce was finalized, Peck married Veronique Passani (1932–2012),[32] a Paris news reporter who had interviewed him in 1952 before he went to Italy to film Roman Holiday. He asked her to lunch six months later and they became inseparable. They had a son, Anthony Peck (b. 1956),[33] and a daughter, Cecilia Peck (b. 1958).[34] The couple remained married until Gregory Peck's death. His daughter Cecilia lives in Los Angeles.

Peck had grandchildren from both marriages.[35]

Peck owned the thoroughbred steeplechase race horse Different Class, which raced in England.[36] The horse was favored for the 1968 Grand National but finished third. Peck was close friends with French president Jacques Chirac.[37]

Peck was Roman Catholic and once considered entering the priesthood. Later in his career, a journalist asked Peck if he was a practicing Catholic. Peck answered, "I am a Roman Catholic. Not a fanatic, but I practice enough to keep the franchise. I don't always agree with the Pope... there are issues that concern me, like abortion, contraception, the ordination of women...and others."[38] His second marriage was performed by a justice of the peace, and not the Roman Catholic Church, because the Church prohibits multiple sacramental marriages when both spouses of a sacramental marriage are still living and have not had their original marriage annulled. Peck was a significant fundraiser for a priest friend of his (Father Albert O'Hara), and served as co-producer of a cassette recording of the New Testament with his son Stephen.[38]

On June 12, 2003, Peck died in his sleep at home from bronchopneumonia at the age of 87.[39] His wife, Veronique, was by his side.[40]

Gregory Peck is entombed in the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels mausoleum in Los Angeles. His eulogy was read by Brock Peters, whose character, Tom Robinson, was defended by Peck's Atticus Finch in To Kill a Mockingbird.[41][42] The celebrities who attended Peck's funeral included Lauren Bacall, Sidney Poitier, Harry Belafonte, Shari Belafonte, Harrison Ford, Calista Flockhart, Mike Farrell, Shelley Fabares, Jimmy Smits, Louis Jourdan, Dyan Cannon, Stephanie Zimbalist, Michael York, Angie Dickinson, Larry Gelbart, Michael Jackson, Anjelica Huston, Lionel Richie, Louise Fletcher, Tony Danza, and Piper Laurie.[41][43]

Awards and honors

Peck was nominated for five Academy Awards, winning once. He was nominated for The Keys of the Kingdom (1945), The Yearling (1946), Gentleman's Agreement (1947), and Twelve O'Clock High (1949). He won the Academy Award for Best Actor for his role as Atticus Finch in the 1962 film To Kill a Mockingbird. In 1968, he received the Academy's Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award.

Peck also received many Golden Globe awards. He won in 1947 for The Yearling, in 1963 for To Kill a Mockingbird, and in 1999 for the TV miniseries Moby Dick. He was nominated in 1978 for The Boys from Brazil. He received the Cecil B. DeMille Award in 1969, and was given the Henrietta Award in 1951 and 1955 for World Film Favorite – Male.

In 1969, US President Lyndon Johnson honored Peck with the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation's highest civilian honor. In 1971, the Screen Actors Guild presented Peck with the SAG Life Achievement Award. In 1989, the American Film Institute gave Peck the AFI Life Achievement Award. He received the Crystal Globe award for outstanding artistic contribution to world cinema in 1996.

In 1986, Peck was honored alongside actress Gene Tierney with the first Donostia Lifetime Achievement Award at the San Sebastian Film Festival in Spain for their body of work.

In 1987, Peck was awarded the George Eastman Award, given by George Eastman House for distinguished contribution to the art of film.[44]

In 1993, Peck was awarded with an Honorary Golden Bear at the 43rd Berlin International Film Festival.[45]

In 1998, he was awarded the National Medal of Arts.[46]

In 2000, Peck was made a Doctor of Letters by the National University of Ireland. He was a founding patron of the University College Dublin School of Film, where he persuaded Martin Scorsese to become an honorary patron. Peck was also chairman of the American Cancer Society for a short time.

For his contribution to the motion picture industry, Gregory Peck has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 6100 Hollywood Blvd. In November 2005, the star was stolen, and has since been replaced.[47]

On April 28, 2011, a ceremony was held in Beverly Hills, California, celebrating the first day of issue of a U.S. postage stamp commemorating Peck. The stamp is the 17th commemorative stamp in the Legends of Hollywood series.[48][49]

Filmography

Box Office ranking

At the height of his career, Peck was voted by film exhibitors in different polls as being among the most popular stars in the country in the US and the UK:[50]

- 1948 – 10th (UK)[51]

- 1949 – 23rd (US)[52]

- 1950 – 12th (US)

- 1951 – 11th (US)

- 1952 – 8th (US), 2nd (UK)[53]

- 1953 – 14th (US), 4th (UK)

- 1954 – 21st (US), 3rd (UK)[54]

- 1956 – 19th (US)

- 1958 – 22nd (US)

- 1961 – 20th (US)

- 1962 – 25th (US)

Radio appearances

| Year | Program | Episode/source |

|---|---|---|

| 1944 | The Screen Guild Theater | Anna Karenina[55] |

| 1946 | Hollywood Players | Sullivan's Travels[56] |

| 1946 | Lux Radio Theatre | Now, Voyager[57] |

| 1946 | Hollywood Players | No Time for Comedy[58] |

| 1952 | Stars in the Air | The Yearling[59] |

See also

References

- ^ Vanity Fair

- ^ http://www.americanancestors.org/assortment-famous-actors/

- ^ Freedland, Michael. Gregory Peck: A Biography. New York: William Morrow and Company. 1980. ISBN 0-688-03619-8 p.10

- ^ United States Census records for La Jolla, California 1910

- ^ United States Census records for St. Louis, Missouri – 1860, 1870, 1880, 1900, 1910

- ^ Freedland, pp. 12–18

- ^ Freedland, pp. 16–19

- ^ Fishgall, Barry (2002). Gregory Peck: A Biography. New York City: Simon and Schuster. pp. 36–37. ISBN 0-684-85290-X.

- ^ Thomas, Tony. Gregory Peck. Pyramid Publications, 1977, p. 16

- ^ ""Gregory Peck comes home", ''Berkeley Magazine'', Summer 1996". Berkeley.edu. 2000-07-04.

- ^ Freedland, p. 35

- ^ "Gregory Peck Returns to Theatre Roots in Virginia Mountains", Playbill, June 29, 1998

- ^ Tad Mosel, Leading Lady: The World and Theatre of Katharine Cornell, Boston: Little, Brown & Co. 1978[page needed]

- ^ Welton Jones. "Gregory Peck," San Diego Union-Tribune, April 5, 1998

- ^ "Playhouse Highlights". La Jolla Playhouse. Retrieved March 19, 2013.

- ^ http://www.afi.com/100years/handv.aspx

- ^ http://www.theguardian.com/news/2003/jun/14/guardianobituaries.film

- ^ Freedland, pp. 191–195

- ^ Freedland, pp. 242–243

- ^ Board, Josh (12 May 2011). "San Diego Acting Legend Gregory Peck Gets a Stamp". Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ^ Haggerty, Bridget. "Gregory Peck's Irish Connections". IrishCultureAndCustoms.com

- ^ Freedland, p. 197

- ^ Corliss, Richard. "The American as Noble Man". Time. June 16, 2003

- ^ Freedland, pp. 231–241

- ^ "". "1987 Robert Bork TV ad, narrated by Gregory Peck". YouTube.com. Retrieved 2010-06-20.

{{cite web}}:|author=has numeric name (help) - ^ Srteve Profitt "Gregory Peck: A Leading Hollywood Liberal Still Can't Put Down a Good Book", Los Angeles Times, November 5, 2000

- ^ Fishgall, Gary (2002). Gregory Peck : a biography. New York: Scribner. p. Introduction p.14. ISBN 0-684-85290-X.

But he shares with his characters a passion for the ideals in which he believes. In his case, these include civil rights, gun control, and most of the other planks in the liberal Democratic Party canon.

- ^ Haney, Lynn (2009). Gregory Peck: A Charmed Life. De Capo Press. ISBN 9780786737819.

- ^ Fishgall, Gary (2002). "Gregory Peck: A Biography". ISBN 9780684852904.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Smit, David (2012). "Ingrid Bergman: The Life, Career and Public Image". ISBN 9780786472260.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Darrach, Brad (15 June 1987). "Gregory Peck". People. Retrieved 5 October 2015.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Gregory Peck's widow Veronique, an arts supporter, dies at 80". Reuters. 18 August 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

- ^ Gary Fishgall, Gregory Peck: A Biography, Simon and Schuster, 2002 p196

- ^ Gary Fishgall, Gregory Peck: A Biography, Simon and Schuster, 2002 p203

- ^ Snyder, Louis (July 3, 2010), Aiglon College Alumni Eagle Association (graduation address).

- ^ "Pedigree Query". 2007-04-30.

- ^ Communiqué de M Jacques Chirac, président de la république, à la suite de la disparition de Gregory Peck (communiqué de la Présidence) (in French), FR: Champs-Élysées, June 2003

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ a b The Religious Affiliation of Gregory Peck

- ^ Grimes, William (June 13, 2003). "Gregory Peck Is Dead at 87; Film Roles Had Moral Fiber". New York Times.

Gregory Peck, whose chiseled, slightly melancholy good looks, resonant baritone and quiet strength made him an unforgettable presence in films like To Kill a Mockingbird, Gentleman's Agreement and Twelve O'Clock High, died early yesterday at his home in Los Angeles. He was 87.

- ^ "Gregory Peck - Obituary". Playbill. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b Rubin, Joel; Hoffman, Alice (17 June 2003). "Peck Memorial Honors Beloved Actor and Man". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ McLaughlin, Katie (3 February 2012). "'Mockingbird' film at 50: Lessons on tolerance, justice, fatherhood hold true". CNN. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ^ Collins, Dan (17 June 2003). "Peck Eulogized As Extraordinary". CBS News. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ^ "Awards granted by George Eastman House International Museum of Photography & Film". George Eastman House. Retrieved April 30, 2012.

- ^ "Berlinale: 1993 Prize Winners". berlinale.de. Retrieved 2011-05-29.

- ^ "Lifetime Honors – National Medal of Arts". Nea.gov.

- ^ "Gregory Peck's Hollywood star is reborn". Nine News (Australian Associated Press). December 1, 2005.

- ^ Broadway World, April 4, 2011 http://movies.broadwayworld.com/article/Gregory_Peck_Honored_With_Commemorative_Stamp_Celebration_428_20110404

- ^ Fox News, 28 April 2011

- ^ International Motion Picture Almanac, Quigley Publishing, 2014

- ^ "THE BOX OFFICE DRAW". Goulburn Evening Post. NSW: National Library of Australia. 31 December 1948. p. 3 Edition: Daily and Evening. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ^ "Hope Tops Crosby At the Boxoffice" by Richard L. Coe. The Washington Post [Washington, D.C.] 30 Dec 1949: 19.

- ^ "BOX OFFICE DRAW". The Barrier Miner. Broken Hill, NSW: National Library of Australia. 29 December 1952. p. 3. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ^ "JOHN WAYNE HEADS BOX-OFFICE POLL". The Mercury. Hobart, Tas.: National Library of Australia. 31 December 1954. p. 6. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ^ Gary Fishgall, Gregory Peck: A Biography, Simon and Schuster, 2002 pg98

- ^ "Dramatic Star". Harrisburg Telegraph. October 19, 1946. p. 17. Retrieved October 1, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Those Were the Days". Nostalgia Digest. 35 (2): 32–39. Spring 2009.

- ^ "Tuesday Star". Harrisburg Telegraph. December 7, 1946. p. 19. Retrieved September 12, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Kirby, Walter (February 10, 1952). "Better Radio Programs for the Week". The Decatur Daily Review. p. 38. Retrieved June 2, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

Further reading

- Fishgall, Gary. Gregory Peck: A Biography. New York: Scribner. 2002. ISBN 0-684-85290-X

- Freedland, Michael. Gregory Peck: A Biography. New York: William Morrow and Company. 1980. ISBN 0-688-03619-8

- Haney, Lynn. Gregory Peck: A Charmed Life. New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers. 2004. ISBN 0-7867-1473-5

External links

- Gregory Peck Official Website – The Gregory Peck Foundation

- Gregory Peck at the Internet Broadway Database

- Gregory Peck at IMDb

- Gregory Peck at the TCM Movie Database

- Gregory Peck at Find a Grave

- Gregory Peck – Daily Telegraph obituary

- Gregory Peck in the 1920 US Census, 1930 US Census, and the Social Security Death Index.

- Gregory Peck papers, Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

- Gregory Peck interview on BBC Radio 4 Desert Island Discs, August 8, 1980

- 1916 births

- 2003 deaths

- 20th Century Fox contract players

- 20th-century American male actors

- 21st-century American male actors

- Academy Honorary Award recipients

- American anti–Vietnam War activists

- American male film actors

- American male stage actors

- American people of English descent

- American people of Irish descent

- American people of Scottish descent

- American racehorse owners and breeders

- American Roman Catholics

- Best Actor Academy Award winners

- Best Drama Actor Golden Globe (film) winners

- Best Supporting Actor Golden Globe (television) winners

- Burials at the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels

- California Democrats

- Cecil B. DeMille Award Golden Globe winners

- César Award winners

- David di Donatello Career Award winners

- David di Donatello winners

- Deaths from bronchopneumonia

- Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award winners

- Kennedy Center honorees

- Male actors from San Diego, California

- Male Western (genre) film actors

- Neighborhood Playhouse School of the Theatre alumni

- People from La Jolla, San Diego

- Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients

- Presidents of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

- San Diego State University alumni

- United States National Medal of Arts recipients

- University of California, Berkeley alumni