Ethiopian historiography

Ethiopian historiography includes the ancient, medieval, early modern, and modern disciplines of recording the history of Ethiopia, including both native and foreign sources. The roots of Ethiopian historical writing can be traced back to the ancient Kingdom of Aksum (c. AD 100 – c. 940). These early texts were written in either the Ethiopian Ge'ez script or the Greek alphabet, and included a variety of mediums such as manuscripts and epigraphic inscriptions on monumental stelae and obelisks documenting contemporary events. The writing of history became an established genre in Ethiopian literature during the early Solomonic dynasty (1270–1974). In this period, written histories were usually in the form of royal biographies and dynastic chronicles, supplemented by hagiographic literature and universal histories in the form of annals. Christian mythology became a linchpin of medieval Ethiopian historiography due to works such as the Orthodox Kebra Nagast. This reinforced the genealogical traditions of Ethiopia's Solomonic dynasty rulers, which asserted that they were descendants of Solomon, the legendary King of Israel.

Ethiopian historiographic literature has been traditionally dominated by Christian theology and the chronology of the Bible. There was also considerable influence from Muslim, pagan and foreign elements from within the Horn of Africa and beyond. Diplomatic ties with Christendom were established in the Roman era under Ethiopia's first Christian king, Ezana of Axum, in the 4th century AD, and were renewed in the Late Middle Ages with embassies traveling to and from medieval Europe. Building on the legacy of ancient Greek and Roman historical writings about Ethiopia, medieval European chroniclers made attempts to describe Ethiopia, its people, and religious faith in connection to the mythical Prester John, who was viewed as a potential ally against Islamic powers. Ethiopian history and its peoples were also mentioned in works of medieval Islamic historiography and even Chinese encyclopedias, travel literature, and official histories.

During the 16th century and onset of the early modern period, military alliances with the Portuguese Empire were made, the Jesuit Catholic missionaries arrived, and prolonged warfare with Islamic foes including the Adal Sultanate and Ottoman Empire, as well as with the polytheistic Oromo people, threatened the security of the Ethiopian Empire. These contacts and conflicts inspired works of ethnography, by authors such as the monk and historian Bahrey, which were embedded into the existing historiographic tradition and encouraged a broader view in historical chronicles for Ethiopia's place in the world. The Jesuit missionaries Pedro Páez (1564–1622) and Manuel de Almeida (1580–1646) also composed a history of Ethiopia, but it remained in manuscript form among Jesuit priests of Portuguese India and was not published in the West until modern times.

Modern Ethiopian historiography was developed locally by native Ethiopians as well as by foreign historians like Hiob Ludolf. The late 19th and early 20th centuries marked a period where Western historiographic methods were introduced and synthesized with traditionalist practices, embodied by works such as those by Heruy Wolde Selassie (1878–1938). The discipline has since developed new approaches in studying the nation's past and offered criticism of some traditional Semitic-dominated views that have been prevalent, sometimes at the expense of Ethiopia's traditional ties with the Middle East. Marxist historiography and African studies have also played significant roles in developing the discipline. Since the 20th century, historians have given greater consideration to issues of class, gender, and ethnicity. Traditions pertaining mainly to other Afroasiatic-speaking populations have also been accorded more importance, with literary, linguistic, and archaeological analyses reshaping the perception of their roles in historical Ethiopian society. Historiography of the 20th century focused largely on the Abyssinian Crisis of 1935 and the Second Italo-Ethiopian War, whereas the Ethiopian victory over the Kingdom of Italy in the 1896 Battle of Adwa played a major role in the historiographic literature of these two countries immediately following the First Italo-Ethiopian War.

Ancient origins

[edit]

Writing was introduced to Ethiopia as far back as the 5th century BC with the ancient South Arabian script.[2] This South Semitic script served as the basis for the creation of Ethiopia's Ge'ez script, the oldest evidence of which was found in Matara, Eritrea, and dated to the 2nd century AD.[2] However, the 1st-century AD Roman Periplus of the Erythraean Sea asserts that the local ruler of Adulis could speak and write in Greek.[3] This embrace of Hellenism could also be found in the coinage of Aksumite currency, in which legends were usually written in Greek, much like ancient Greek coinage.[3]

Epigraphy

[edit]The roots of the historiographic tradition in Ethiopia date back to the Aksumite period (c. 100 – c. 940 AD) and are found in epigraphic texts commissioned by monarchs to recount the deeds of their reign and royal house. Written in an autobiographical style, in either the native Ge'ez script, the Greek alphabet, or both, they are preserved on stelae, thrones, and obelisks found in a wide geographical span that includes Sudan, Eritrea, and Ethiopia.[4] In commemorating the contemporary ruler or aristocrats and elite members of society, these documents record various historical events such as military campaigns, diplomatic missions, and acts of philanthropy. For instance, 4th-century stelae erected by Ezana of Axum memorialize his achievements in battle and expansion of the realm in the Horn of Africa, while the Monumentum Adulitanum inscribed on a throne in Adulis, Eritrea, contains descriptions of Kaleb of Axum's conquests in the Red Sea region during the 6th century, including parts of the Arabian peninsula.[5] It is clear that such texts influenced the epigraphy of later Aksumite rulers who still considered their lost Arabian territories as part of their realm.[6]

In Roman historiography, the ecclesiastical history of Tyrannius Rufinus, a Latin translation and extension of the work of Eusebius dated circa 402, offers an account of the Christian conversion of Ethiopia (labeled as "India ulterior") by the missionary Frumentius of Tyre.[7] The text explains that Frumentius, in order to complete this task, was ordained a bishop by Athanasius of Alexandria (298–373), most likely after 346 during the latter's third tenure as Bishop of Alexandria.[8] The mission certainly took place before 357, when Athanasius was deposed, replaced by George of Cappadocia, and forced into flight, during which he wrote an apologetic letter to Roman emperor Constantius II (r. 337–361) that coincidentally preserved an Imperial Roman letter to the royal court of Aksum.[9] In this letter, Constantius II addresses two "tyrants" of Ethiopia, Aizanas and Sazanas, who are undoubtedly Ezana and his brother Saiazana, or Sazanan, a military commander.[10] The letter also hints that the ruler of Aksum was already a Christian monarch.[9] From the early inscriptions of Ezana's reign it is clear that he was once a polytheist,[1] who erected bronze, silver, and gold statues to Ares, Greek god of war.[2] But the dual Greek and Sabaean-style Ge'ez inscriptions on the Ezana Stone, commemorating Ezana's conquests of the Kingdom of Kush (located in Nubia, i.e. modern Sudan), mention his conversion to Christianity.[1]

Cosmas Indicopleustes, a 6th-century Eastern Roman monk and former merchant who wrote the Christian Topography (describing the Indian Ocean trade leading all the way to China),[11] visited the Aksumite port city of Adulis and included eyewitness accounts of it in his book.[12] He copied a Greek inscription detailing the reign of an early 3rd-century polytheistic ruler of Aksum who sent a naval fleet across the Red Sea to conquer the Sabaeans in what is now Yemen, along with other parts of western Arabia.[12][13] Ancient Sabaean texts from Yemen confirm that this was the Aksumite ruler Gadara, who made alliances with Sabaean kings, leading to eventual Axumite control over western Yemen that would last until the Himyarite ruler Shammar Yahri'sh (r. c. 265 – c. 287) expelled the Aksumites from southwestern Arabia.[14] It is only from Sabaean and Himyarite inscriptions that we know the names of several Aksumite kings and princes after Gadara, including the monarchs `DBH and DTWNS.[15] Inscriptions of king Ezana mention stone-carved thrones near the Church of Our Lady Mary of Zion in Axum (the platforms of which still exist), and Cosmas described a white-marble throne and stele in Adulis that were both covered in Greek inscriptions.[12]

Manuscripts

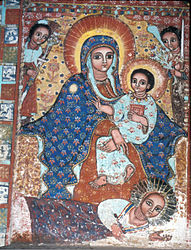

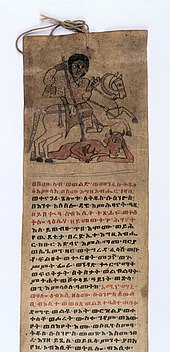

[edit]Aside from epigraphy, Aksumite historiography also includes the manuscript textual tradition. Some of the earliest Ethiopian illuminated manuscripts include translations of the Bible into Ge'ez, such as the Garima Gospels that were written between the 4th and 7th centuries and imitated the Byzantine style of manuscript art.[16][17] The Aksum Collection containing a Ge'ez codex that provides chronologies for the diocese and episcopal sees of the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria in Roman Egypt was compiled between the 5th and 7th centuries.[16] These texts reveal how the Aksumites viewed history through the narrow lens of Christian chronology, but their early historiography was perhaps also influenced by non-Christian works, such as those from the Kingdom of Kush, the Ptolemaic dynasty of Hellenistic Egypt, and the Yemenite Jews of the Himyarite Kingdom.[6]

Medieval historiography

[edit]Zagwe dynasty

[edit]The power of the Aksumite Kingdom declined after the 6th century due to the rise of other regional states in the Horn of Africa.[20] Modern scholars continue to debate the identity and provenance of the legendary or semi-legendary figure Gudit (fl. 10th century), a queen who is traditionally believed to have overthrown the Kingdom of Aksum.[21] The legend is found in the 13th-century chronicle of the monk Tekle Haymanot, who compiled historical writings gathered from various Ethiopian churches and monasteries.[22] The chronicle alleges that, after being exiled from Axum, she married a Jewish king of Syria and converted to Judaism. The Scottish travel writer James Bruce (1730–1794) was incredulous about the tale and believed she was simply a Jewish queen.[22] Carlo Conti Rossini (1872–1949) hypothesized that she was an ethnic Sidamo from Damot, whereas Steven Kaplan argues she was a non-Christian invader and historian Knud Tage Andersen contends she was a regular member of the Aksumite royal house who shrewdly seized the throne.[21] The latter is more in line with another legend that claims Dil Na'od, the last king of Aksum, kept his daughter Mesobe Werq in isolation out of fear of a prophecy that her son would overthrow him, yet she eloped with the nobleman Mara Takla Haymanot from Lasta who eventually killed the Aksumite king in a duel, took the throne and founded the Zagwe dynasty.[23] The latter remains one of the most poorly understood periods of Ethiopia's recorded history.[24] What is known is that the early Zagwe kings were polytheistic, eventually converted to Christianity, and ruled over the northern Highlands of Ethiopia, while Islamic sultanates inhabited the coastal Ethiopian Lowlands.[20]

Solomonic dynasty

[edit]

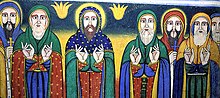

When the forces of Yekuno Amlak (r. 1270–1285) toppled the Zagwe dynasty in 1270 he became the first Emperor of Ethiopia, establishing a line of rulers in the Solomonic dynasty that would last into the 20th century.[20] By this time the Greek language, once pivotal for translation in Ethiopian literature, had become marginalized and mixed with Coptic and Arabic translations.[26] This contributed to a process by which medieval Ethiopian historians created a new historiographic tradition largely divorced from the ancient Aksumite textual corpus.[26] The Solomonic kings professed a direct link to the kings of Aksum and a lineage traced back to Solomon and the Queen of Sheba in the Hebrew Bible.[27][28] These genealogical traditions formed the basis of the Kebra Nagast, a seminal work of Ethiopian literature and Ge'ez-language text originally compiled in Copto-Arabic sometime between the 10th and 13th centuries.[27][28] Its current form dates to the 14th century, by which point it included detailed mythological and historical narratives relating to Ethiopia along with theological discourses on themes in the Old and New Testament.[29] De Lorenzi compares the tome's mixture of Christian mythology with historical events to the legend of King Arthur that was greatly embellished by the Welsh cleric Geoffrey of Monmouth in his chronicle Historia Regum Britanniae of 1136.[30] Although the Kebra Nagast indicates that the emperors of Rome or Constantinople and Ethiopia were descended from the Israelite king Solomon, there is an emphatically anti-Jewish sentiment expressed in several passages of the book.[29]

The most common form of written history sponsored by the Solomonic royal court was the biography of contemporary rulers, who were often lauded by their biographers along with the Solomonic dynasty. The royal biographical genre was established during the reign of Amda Seyon I (r. 1314–1344), whose biography not only recounted the diplomatic exchanges and military conflicts with the rival Islamic Ifat Sultanate, but also depicted the Ethiopian ruler as the Christian savior of his nation.[30] The chronicle titled, The Glorious Victories of Amda Seyon, is far more detailed than any previous Ethiopian work of history and is regraded by historian Richard Pankhurst to be a "masterpiece in historical chronicling".[31] The origins of the dynastic history (tarika nagast) are perhaps found in the biographical chronicle of Baeda Maryam I (r. 1468–1478), which provides a narrative of his life and that of his children and was most likely written by the preceptor of the royal court.[30] Teshale Tibebu asserts that Ethiopian court historians were "professional flatterers" of their ruling monarchs, akin to their Byzantine Greek and Imperial Chinese counterparts.[32] For instance, the anonymously written biography of the emperor Gelawdewos (r. 1540–1549) speaks glowingly of the ruler, albeit in an elegiac tone, while attempting to place him and his deeds within a greater moral and historical context.[33]

There are also hagiographies of previous Zagwe dynastic rulers composed during the Solomonic period. For instance, during the reign of Zara Yaqob (1434–1468) a chronicle focusing on Gebre Mesqel Lalibela (r. 1185–1225) portrayed him as a Christian saint who performed miracles. Conveniently for the legitimacy of the Solomonic dynasty, the chronicle stated that Lalibela did not desire for his heirs to inherit his throne.[25]

Medieval Europe and the search for Prester John

[edit]

In Greek historiography, Herodotus (484–425 BC) had written brief descriptions of ancient Ethiopians, who were also mentioned in the New Testament.[34] Although the Byzantine Empire maintained regular relations with Ethiopia during the Early Middle Ages, the Early Muslim conquests of the 7th century severed the connection between Ethiopia and the rest of Christendom.[35] Records of these contacts encouraged medieval Europeans to discover if Ethiopia was still Christian or had converted to Islam, an idea bolstered by the presence of Ethiopian pilgrims in the Holy Land and Jerusalem during the Crusades.[36] During the High Middle Ages, the Mongol conquests of Genghis Khan (r. 1206–1227) led Europeans to speculate about the existence of a priestly, legendary warrior king named Prester John, who was thought to inhabit distant lands in Asia associated with Nestorian Christians and might help to defeat rival Islamic powers. The travel literature of Marco Polo and Odoric of Pordenone regarding their separate journeys to Yuan-dynasty China during the 13th and 14th centuries, respectively, and fruitless searches in southern India, helped to dispel the notion that Prester John's kingdom existed in Asia.[37] A lost treatise by cartographer Giovanni da Carignano (1250–1329), which only survives in a much later work by Giacomo Filippo Foresti (1434–1520), was long presumed to attest to a diplomatic mission sent by Ethiopian emperor Wedem Arad (r. 1299–1314) to Latin Europe in 1306;[38] recent research indicates that this mission was unconnected to Solomonic Ethiopia, however.[39]

In his 1324 Book of Marvels the Dominican missionary Jordan Catala, bishop of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Quilon along the Malabar Coast of India, was the first known author to suggest that Ethiopia was the location of Prester John's kingdom.[40] The Florentine merchant Antonio Bartoli visited Ethiopia from the 1390s until about 1402 when he returned to Europe with Ethiopian diplomats.[38] This was followed by the lengthy stay of Pietro Rombuldo in Ethiopia from 1404 to 1444 and Ethiopian diplomats attending the ecumenical Council of Florence in 1441, where they expressed some vexation with the European attendees who insisted on addressing their emperor as Prester John.[41] Thanks to the legacy of European medieval historiography, this belief persisted beyond the Late Middle Ages. For instance, the Portuguese missionary Francisco Álvares set out for Ethiopia in 1520 believing that he was to visit the homeland of Prester John.[42]

Islamic historiography

[edit]

Ethiopia is mentioned in some works of Islamic historiography, usually in relation to the spread of Islam. Islamic sources state that in 615 the Aksumite king Armah (r. 614–631) provided refuge for the exiled followers of Muhammad in Axum, an event known as the First Hejira (i.e. Migration to Abyssinia).[43] In his History, the scholar ibn Wadîh al-Ya'qûbî (d. 897) of the Abbasid Caliphate identified Abyssinia (al-Habasha) as being located to the north of the territory of the Berber (Somali) as well as the land of the Zanj (the "Blacks").[44] The Mamluk-Egyptian historian Shihab al-Umari (1300–1349) wrote that the historical state of Bale, neighboring the Hadiya Sultanate of southern Ethiopia, was part of an Islamic Zeila confederacy, although it fell under the control of the Ethiopian Empire in the 1330s, during the reign of Amda Seyon I.[45] Al-Maqrizi (1364–1422), another Mamluk-Egyptian historian, wrote that the Ifat sultan Sa'ad ad-Din II (r. 1387–1415) won a crushing victory against the Christian Amhara in Bale, despite the latter's numerical superiority.[46] He described other allegedly significant victories won by the Adal sultan Jamal ad-Din II (d. 1433) in Bale and Dawaro, where the Muslim leader was said to have taken enough war booty to provide his poorer subjects with multiple slaves.[46] Historian Ulrich Braukämper states that these works of Islamic historiography, while demonstrating the influence and military presence of the Adal sultanate in southern Ethiopia, tend to overemphasize the importance of military victories that at best led to temporary territorial control in regions such as Bale.[47] In his Description of Africa (1555), the historian Leo Africanus (c. 1494–1554) of Al-Andalus described Abassia (Abyssinia) as the realm of the Prete Ianni (i.e. Prester John), unto whom the Abassins (Abyssinians) were subject. He also identified Abassins as one of five main population groups on the continent alongside Africans (Moors), Egyptians, Arabians and Cafri (Cafates).[48]

Chinese historiography

[edit]Contacts between the Ethiopian Empire and Imperial China seem to have been very limited, if not mostly indirect. There were some attempts in Chinese historiographic and encyclopedic literature to describe parts of Ethiopia or outside areas that it once controlled. Zhang Xiang, a scholar of Africa–China relations, asserts that the country of Dou le described in the Xiyu juan (i.e. Western Regions) chapter of the Book of Later Han was that of the Aksumite port city of Adulis.[49] It was from this city that an envoy was sent to Luoyang, the capital of China's Han dynasty, in roughly 100 AD.[49] The 11th-century New Book of Tang and 14th-century Wenxian Tongkao describe the country of Nubia (previously controlled by the Aksumite Kingdom) as a land of deserts south of the Byzantine Empire that was infested with malaria, where the natives of the local Mo-lin territory had black skin and consumed foods such as Persian dates.[50] In his English translation of this document, Friedrich Hirth identified Mo-lin (Molin) with the kingdom of 'Alwa and neighboring Lao-p'o-sa with the kingdom of Maqurra, both in Nubia.[50]

The Wenxian Tongkao describes the main religions of Nubia, including the Da Qin religion (i.e. Christianity, particularly Nestorian Christianity associated with the Eastern Roman Empire) and the day of rest occurring every seven days for those following the faith of the Da shi (i.e. the Muslim Arabs).[50] These passages are ultimately derived from the Jingxingji of Du Huan (fl. 8th century),[51] a travel writer during the Chinese Tang dynasty (618–907) who was captured by Abbasid forces in the 751 Battle of Talas, after which he visited parts of West Asia and northeast Africa.[49] Historian Wolbert Smidt identified the territory of Molin in Du's Jingxingji (preserved in part by the Tongdian of Du You) as the Christian kingdom of Muqurra in Nubia. He also associated the territory of Laobosa (Lao-p'o-sa) depicted therein with Abyssinia, thereby making this the first Chinese text to describe Ethiopia.[52][49] When Du Huan left the region to return home, he did so through the Aksumite port of Adulis.[49] Trade activity between Ethiopia and China during the latter's Song dynasty (960–1279) seems to be confirmed by Song-Chinese coinage found in the medieval village of Harla, near Dire Dawa, Ethiopia. The Chinese Ming dynasty (1368–1644) sent diplomats to Ethiopia, which was also frequented by Chinese merchants. Although only private and indirect trade was conducted with African countries during the early Manchu-led Qing dynasty (1644–1911), the Chinese were able to refer to Chinese-written travel literature and histories about East Africa before diplomatic relations were restored with African countries in the 19th century.[49]

Early Modern historiography

[edit]

Conflict and interaction with foreign powers

[edit]During the 16th century the Ethiopian biographical tradition became far more complex, intertextual, and broader in its view of the world given Ethiopia's direct involvement in the conflicts between the Ottoman and Portuguese empires in the Red Sea region.[53] The annals of Dawit II (r. 1508–1540) describe the defensive war he waged against Imam Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi (r. 1527–1543), in an episodic format quite different from the earlier chronicling tradition.[54] The chronicle of Gelawdewos, perhaps written by the Ethiopian Orthodox Church abbot Enbaqom (1470–1560), is far more detailed than any previous Ethiopian work of history.[54] It explains the Ethiopian emperor's military alliance with Cristóvão da Gama (1516–1542), son of the Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama, against the Adal Sultan al-Ghazi and his Ottoman allies, and later against the Ottoman governor of Yemen, Özdemir Pasha (d. 1560).[53]

The biography of Galawdewos' brother and successor Menas of Ethiopia (r. 1559–1563) is divided into two parts, one dedicated to his life before taking the throne and the other to his troubled reign fighting against rebels.[55] His chronicle was completed by the biographers of his successor Sarsa Dengel (r. 1563–1597). The latter's chronicle can be considered an epic cycle for its preface describing events in previous eras mixed with biblical allusions.[55] It also describes conflicts against rebel nobility allied with the Ottomans as well as a military campaign against Ethiopian Jews.[55]

By the 16th century Ethiopian works began to discuss the profound impact of foreign peoples in their own regional history. The chronicle of Gelawdewos explained the friction between the Ethiopian Orthodox Church and the Catholic missionaries from Spain and Portugal, after the arrival of the Jesuits in 1555.[55] With the persuasion of Jesuits in his realm, emperor Susenyos I (r. 1607–1632) became the only Ethiopian ruler to convert from Orthodox Christianity to Catholicism, perhaps earlier than the accepted date of 1625, after which his attempts to convert his subjects and undermine the Orthodox church led to internal revolts.[56] In 1593 the Ethiopian monk, historian, and ethnographer Bahrey published a work of ethnography that provided reasoning for the military success of the polytheistic Oromo people who fought against the Ethiopian Empire.[55] Ethiopian histories of this period also included details of foreign Muslims, Jews, Christians (including those from Western Europe), Safavid Iranians, and even figures of the fallen Byzantine Empire.[55]

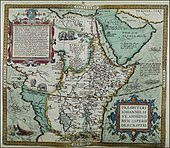

Pedro Paez (1564–1622), a Spanish Jesuit at the court of Susenyos I, translated portions of the chronicles of Ethiopian emperors stretching back to the reign of Amda Seyon I in the 14th century AD, as well as the reign of king Kaleb of Axum in the 6th century AD.[57] Some of these fragments were preserved in the Historia de Ethiopia by the Portuguese Jesuit Manuel de Almeida (1580–1646),[58] but Paez's original manuscript was largely rewritten to remove polemical passages against the rival Dominican Order.[59] Paez also translated a chapter from an Ethiopian hagiography that covered the life and works of the 13th-century ruler Gebre Mesqel Lalibela.[60] The Historia de Ethiopia, which arrived in Goa, India, by the end of 1624, was not published in Europe until the modern era and remained in circulation only among members of the Society of Jesus in Portuguese India, although Almeida's map of Ethiopia was published by Baltasar Teles in 1660.[61] Following the abdication of Susenyos I, his son and successor Fasilides (r. 1632–1667) had the Jesuits expelled from Ethiopia.[43]

Biographical chronicles and dynastic histories

[edit]At least as far back as the reign of Susenyos I the Ethiopian royal court employed an official court historian known as a sahafe te'ezaz, who was usually also a senior scholar within the Ethiopian Orthodox Church.[62] Susenyos I had his confessor Meherka Dengel and counselor Takla Sellase (d. 1638), nicknamed "Tino", compose his biography.[63] Biographies were written for the emperors Yohannes I (r. 1667–1682), Iyasu I (1682–1706), and Bakaffa (r. 1721–1730), the latter employing four separate court historians: Sinoda, Demetros, Arse, and Hawaryat Krestos.[63] The reigns of the emperors Iyasu II (r. 1730–1755) and Iyoas I (r. 1755–1769) were included in general dynastic histories, while the last known royal biography in chronicle format prior to the 19th century was written by the church scholar Gabru and covered the first reign of Tekle Giyorgis I (r. 1779–1784), the text ending abruptly just before his deposition.[63]

Modern historiography

[edit]Era of the Princes

[edit]The chaotic period known as the Era of the Princes (Zemene Mesafint) from the mid-18th to mid-19th centuries witnessed political fragmentation, civil war, loss of central authority, and, as a result of these, a complete shift away from the royal biography in favor of dynastic histories.[63] A new genre of dynastic history, known as the "Short Chronicle" according to Lorenzi, was established by a church scholar named Takla Haymanot, whose work combined universal history with Solomonic dynastic history.[63] The "Short Chronicle" genre of historiography continued well into the 20th century.[63] Ge'ez became an extinct language by the 17th century, but it wasn't until the reign of Tewodros II (r. 1855–1868) that royal chronicles were written in the vernacular Semitic language of Amharic.[64]

Another genre of history writing produced during the Era of the Princes was the terse Ethiopian annal known as ya'alam tarik.[65] These works attempted to list major world events from the time of the biblical Genesis until their present time in a universal history.[65] For instance, the translated work of John of Nikiû explaining human history until the Muslim conquest of Egypt in 642 became a canonical text in Ethiopian historiography.[65] There are also chronological and genealogical lists of rulers and Orthodox Church patriarchs that include some elements of historical narrative.[65]

Biographical literature

[edit]Various biographies of Ethiopian emperors have been compiled in the modern era. In 1975 the Oxford-educated historian Zewde Gebre-Sellassie (1926–2008) published a biography on the Emperor Yohannes II (r. 1699–1769), with whom he was distantly related.[66] In 1973 and 1974, the Emperor Haile Selassie (r. 1930–1974) published his autobiography My Life and Ethiopia's Progress; in 1976 it was translated from Amharic into English and annotated by Edward Ullendorff in an Oxford University Press publication.[67] Hanna Rubinkowska maintains that Emperor Selassie was an active proponent of "historiographic manipulation", especially when it came to concealing historical materials that seemingly contested or contradicted dynastic propaganda and official history.[68] For instance, he removed certain chronicles and historical works from the public eye and placed them in his private library, such as aleqa Gabra Igziabiher Elyas' (1892–1969) biographical chronicle covering the reigns of Selassie's predecessors Lij Iyasu (r. 1913–1916), a late convert to Islam, and the Empress Zewditu (r. 1916–1930).[69][70] The latter work was edited, translated into English and republished by Rudolf K. Molvaer in 1994.[71][72]

Ethiopian and Western historiography

[edit]

Edward Ullendorff considered the German orientalist Hiob Ludolf (1624–1704) to be the founder of Ethiopian studies in Europe, thanks to his efforts in documenting the history of Ethiopia and the Ge'ez language, as well as Amharic.[75][76] The Ethiopian monk Abba Gorgoryos (1595–1658), while lobbying the Propaganda Fide in Rome to become bishop of Ethiopia following his Catholic conversion and expulsion of the Jesuits by Ethiopian emperor Fasilides, collaborated with Ludolf – who never actually visited Ethiopia – and provided him with critical information for composing his Historia Aethiopica and its Commentaries.[77][78] The ethnically-Ethiopian Portuguese cleric António d'Andrade (1610–1670) aided them as a translator,[79] since Abba Gorgoryos was not a fluent speaker of either Latin or Italian.[80] After Ludolf, the 18th-century Scottish travel writer James Bruce, who visited Ethiopia, and German orientalist August Dillmann (1823–1894) are also considered pioneers in the field of early Ethiopian studies.[78][81] After spending time at the Ethiopian royal court, Bruce was the first to systematically collect and deposit Ethiopian historical documents into libraries of Europe, in addition to composing a history of Ethiopia based on native Ethiopian sources.[82] Dillmann cataloged a variety of Ethiopian manuscripts, including historical chronicles, and in 1865 published the Lexicon Linguae Aethiopicae, the first such lexicon to be published on languages of Ethiopia since Ludolf's work.[83]

Ethiopian historians such as Taddesse Tamrat (1935–2013) and Sergew Hable Sellassie have argued that modern Ethiopian studies were an invention of the 17th century and originated in Europe.[80] Tamrat considered Carlo Conti Rossini's 1928 Storia d'Etiopia a groundbreaking work in Ethiopian studies.[80] The philosopher Messay Kebede likewise acknowledged the genuine contributions of Western scholars to the understanding of Ethiopia's past.[84][85] But he also criticized the perceived scientific and institutional bias that he found to be pervasive in Ethiopian-, African-, and Western-made historiographies on Ethiopia.[86] Specifically, Kebede took umbrage at E. A. Wallis Budge's translation of the Kebra Nagast, arguing that Budge had assigned a South Arabian origin to the Queen of Sheba although the Kebra Nagast itself did not indicate such a provenience for this fabled ruler. According to Kebede, a South Arabian extraction was contradicted by biblical exegetes and testimonies from ancient historians, which instead indicated that the Queen was of African origin.[87] Additionally, he chided Budge and Ullendorff for their postulation that the Aksumite civilization was founded by Semitic immigrants from South Arabia. Kebede argued that there is little physical difference between the Semitic-speaking populations in Ethiopia and neighboring Cushitic-speaking groups to validate the notion that the former groups were essentially descendants of South Arabian settlers, with a separate ancestral origin from other local Afroasiatic-speaking populations. He also observed that these Afroasiatic-speaking populations were heterogeneous, having interbred with each other and also assimilated alien elements of both uncertain extraction and negroid origin.[88]

Synthesis of native and Western historiographic methods

[edit]

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Ethiopian vernacular historiography became more heavily influenced by Western methods of historiography, but De Lorenzi contends that these were "indigenized" to suit the cultural sensibilities of traditionalist historians.[89] Gabra Heywat Baykadan, a foreign-educated historian and reformist intellectual during the reign of Menelik II (r. 1889–1913),[90] was unique among his peers for breaking almost entirely from the traditionalist approach to writing vernacular history and systematically adopting Western theoretical methods.[91] Heruy Wolde Selassie (1878–1938), blattengeta and foreign minister of Ethiopia, used English scholarship and nominally adopted modern Western methods in writing vernacular history, but he was a firmly traditionalist historian.[89] His innovative works include a 1922 historical dictionary that offered a prosopographic study of Ethiopia's historical figures and contemporary notables, a history of Ethiopian foreign relations, historiographic travel literature, and a traditionalist historical treatise combining narrative histories for the Zagwe and Solomonic dynasties with other parts on church history and biographies of church leaders.[92] Selassie may have also been the author of a list of monarchs of Ethiopia written in 1922 which took its names and information from both native Ethiopian king lists (from manuscripts and oral tradition) and European texts which wrote of Aethiopia in ancient history and legends.[93] Because the term Aethiopia was often used in ancient times, as well as some translations of the Bible, to refer to ancient Nubia, the king list incorporates monarchs who ruled the kingdom of Kush and Egyptian pharaohs who ruled or interacted with Nubia in some significant way.[94] The king list additionally includes Aethiopian figures mentioned in the Bible and Greek mythology.

Takla Sadeq Makuriya (1913–2000), historian and former head of the National Archives and Library of Ethiopia, wrote various works in Amharic as well as foreign languages, including a four-volume Amharic-language series on the history of Ethiopia from ancient times until the reign of Selassie, published in the 1950s.[95] During the 1980s he published a three-volume tome exploring the reigns of 19th-century Ethiopian rulers and the theme of national unity.[95] He also produced two English chapters on the history of the Horn of Africa for UNESCO's General History of Africa and several French-language works on Ethiopia's church history and royal genealogies.[96] Some volumes from his vernacular survey on general Ethiopian history have been edited and circulated as school textbooks in Ethiopian classrooms by the Ministry of Education.[97] Kebede Michael (1916–1998), a playwright, historian, editor, and director of archaeology at the National Library, wrote works of world history, histories of Western civilization, and histories of Ethiopia, which, unlike his previous works, formed the central focus of his 1955 world history written in Amharic.[98]

Italo-Ethiopian Wars

[edit]

The decisive victory of the Ethiopian Empire over the Kingdom of Italy in the 1896 Battle of Adwa, during the First Italo-Ethiopian War, made a profound impact on the historiography of Italy and Ethiopia.[99] It was not lost to the collective memory of Italians, since the Italian capture of Adwa, Tigray Region, Ethiopia in 1935, during the Second Italo-Ethiopian War, was hailed as an act that avenged their previous humiliation and defeat.[100] Historiography about Ethiopia throughout much of the 20th century focused primarily on this second invasion and the Abyssinian Crisis that preceded it, in which Ethiopia was depicted as being relegated to the role of a pawn in European diplomacy.[101] The Ethiopian courtier (i.e. blatta) and historian Marse Hazan Walda Qirqos (1899–1978) was commissioned by the Selassie regime to compile a documentary history of the Italian occupation entitled A Short History of the Five Years of Hardship, composed concurrently with the submission of historical evidence to the United Nations War Crimes Commission for Fascist Italy's war crimes.[102] Coauthored by Berhanu Denque, this work was one of the first vernacular Amharic histories to cover the Italian colonial period, documenting contemporary newspaper articles and propaganda pieces, events such as the 1936 fall of Addis Ababa and the 1941 British-Ethiopian reconquest of the country, and speeches by key figures such as Emperor Selassie and Rodolfo Graziani (1882–1955), Viceroy of Italian East Africa.[103]

Social class, ethnicity, and gender

[edit]

Modern historians have taken new approaches to analyzing both traditional and modern Ethiopian historiography. For instance, Donald Crummey (1941–2013)[104] investigated instances in Ethiopian historiography dealing with class, ethnicity, and gender.[105] He also criticized earlier approaches made by Sylvia Pankhurst (1882–1960) and Richard Pankhurst (1927–2017), who focused primarily on the Ethiopian ruling class while ignoring marginalized peoples and minority groups in Ethiopian historical works.[105] Following the 1974 Ethiopian Revolution and overthrow of the Solomonic dynasty with the deposition of Haile Selassie, the historical materialism of Marxist historiography came to dominate the academic landscape and understanding of Northeast African history.[106] In her 2001 article Women in Ethiopian History: A Bibliographic Review, Belete Bizuneh remarks that the impact of social history on African historiography in the 20th century generated an unprecedented focus on the roles of women and gender in historical societies, but that Ethiopian historiography seems to have fallen outside the orbit of these historiographic trends.[107]

By relying on the written works of both Christian and Muslim authors, oral traditions, and modern methods of anthropology, archaeology, and linguistics, Mohammed Hassen, Associate Professor of History at Georgia State University,[108] asserts that the largely non-Christian Oromo people have interacted and lived among the Semitic-speaking Christian Amhara people since at least the 14th century, not the 16th century as is commonly accepted in both traditional and recent Ethiopian historiography.[109] His work also stresses Ethiopia's need to properly integrate its Oromo population and the fact that the Cushitic-speaking Oromo, despite their traditional reputation as invaders, were significantly involved in maintaining the cultural, political, and military institutions of the Christian state.[110]

Middle Eastern versus African studies

[edit]

In his 1992 review of Naguib Mahfouz's The Search (1964), the Ethiopian scholar Mulugeta Gudeta observed that Ethiopian and Egyptian societies bore striking historical resemblances.[111] According to Haggai Erlich, these parallels culminated in the establishment of the Egyptian abun ecclesiastical office, which exemplified Ethiopia's traditional connection to Egypt and the Middle East.[112] In the earlier part of the 20th century, Egyptian nationalists also propounded the idea of forming a Unity of the Nile Valley, a territorial union that would include Ethiopia. This objective gradually ebbed due to political tension over control of the Nile waters.[113] Consequently, after the 1950s, Egyptian scholars adopted a more distant if not apathetic approach to Ethiopian affairs and academic studies.[114] For instance, the Fifth Nile 2002 Conference held in Addis Ababa in 1997 was attended by hundreds of scholars and officials, among whom were 163 Ethiopians and 16 Egyptians.[112] By contrast, there were no Egyptian attendees at the Fourteenth International Conference of Ethiopian Studies later held in Addis Ababa in 2000, similar to all previous ICES conferences since the 1960s.[114]

Erlich argues that, in deference to their training as Africanists, native and foreign Ethiopianists of the post-1950 generation focused more on historiographic matters pertaining to Ethiopia's place within the African continent.[114] This trend had the effect of marginalizing Ethiopia's traditional bonds with the Middle East in historiographic works.[114] In Bahru Zewde's retrospective on Ethiopian historiography published in 2000, he highlighted Ethiopia's ancient tradition of historiography, observing that it dates from at least the fourteenth century and distinguishes the territory from most other areas in Africa.[115] He also noted a shift in emphasis in Ethiopian studies away from the field's traditional fixation on Ethiopia's northern Semitic-speaking groups, with an increasing focus on the territory's other Afroasiatic-speaking communities. Zewde suggested that this development was made possible by a greater critical usage of oral traditions.[116] He offered no survey of Ethiopia's role in Middle Eastern studies and made no mention of Egyptian-Ethiopian historical relations.[117] Zewde also observed that historiographic studies in Africa were centered on methods and schools that were primarily developed in Nigeria and Tanzania, and concluded that "the integration of Ethiopian historiography into the African mainstream, a perennial concern, is still far from being achieved to a satisfactory degree."[117]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c Robin (2012), p. 276.

- ^ a b c Anfray (2000), p. 375.

- ^ a b Robin (2012), p. 273.

- ^ De Lorenzi (2015), pp. 14–15.

- ^ De Lorenzi (2015), p. 15.

- ^ a b De Lorenzi (2015), p. 16.

- ^ Robin (2012), pp. 273–274.

- ^ Robin (2012), pp. 274–275.

- ^ a b Robin (2012), p. 275.

- ^ Robin (2012), pp. 275–276.

- ^ Yule (1915), pp. 25, 28.

- ^ a b c Anfray (2000), p. 372.

- ^ Robin (2012), p. 277.

- ^ Robin (2012), pp. 277–278.

- ^ Robin (2012), p. 278.

- ^ a b De Lorenzi (2015), pp. 15–16.

- ^ Anfray (2000), p. 376.

- ^ Riches (2015), pp. 43–44.

- ^ a b Sobania (2012), p. 462.

- ^ a b c De Lorenzi (2015), p. 17.

- ^ a b Augustyniak (2012), pp. 16–17.

- ^ a b Augustyniak (2012), p. 16.

- ^ Augustyniak (2012), p. 17.

- ^ Riches (2015), p. 44.

- ^ a b De Lorenzi (2015), pp. 18–19.

- ^ a b De Lorenzi (2015), pp. 16–17.

- ^ a b De Lorenzi (2015), pp. 17–18.

- ^ a b Phillipson (2014), pp. 66–67.

- ^ a b Phillipson (2014), p. 66.

- ^ a b c De Lorenzi (2015), p. 18.

- ^ Pankhurst, Richard (Feb 14, 2001). The Ethiopians: A History. Wiley. p. 57. ISBN 0631224939.

- ^ Tibebu (1995), p. 13.

- ^ De Lorenzi (2015), p. 13.

- ^ Baldridge (2012), p. 19.

- ^ Baldridge (2012), pp. 19–21.

- ^ Baldridge (2012), p. 20.

- ^ Baldridge (2012), pp. 16–19.

- ^ a b Baldridge (2012), p. 22.

- ^ Krebs, Verena (2019). "Re-examining Foresti's Supplementum Chronicarum and the "Ethiopian" embassy to Europe of 1306". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 82 (3): 493–515. doi:10.1017/S0041977X19000697. ISSN 0041-977X.

- ^ Baldridge (2012), pp. 20–21.

- ^ Baldridge (2012), pp. 22–23.

- ^ Baldridge (2012), p. 23.

- ^ a b Milkias (2015), p. 456.

- ^ Smidt (2001), p. 6.

- ^ Braukämper (2004), pp. 76–77.

- ^ a b Braukämper (2004), p. 77.

- ^ Braukämper (2004), pp. 77–78.

- ^ Africanus (1896), pp. 20, 30.

- ^ a b c d e f Abraham, Curtis. (11 March 2015). "China’s long history in Africa Archived 2017-08-02 at the Wayback Machine ". New African. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ a b c Friedrich Hirth (2000) [1885]. Jerome S. Arkenberg (ed.). "East Asian History Sourcebook: Chinese Accounts of Rome, Byzantium and the Middle East, c. 91 B.C.E. – 1643 C.E." Fordham University. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ Bai (2003), pp. 242–247.

- ^ Smidt (2001), pp. 5–6.

- ^ a b De Lorenzi (2015), pp. 19–20.

- ^ a b De Lorenzi (2015), p. 19.

- ^ a b c d e f De Lorenzi (2015), p. 20.

- ^ Abir (1980), pp. 211–217.

- ^ Cohen (2009), pp. 106–107.

- ^ Cohen (2009), p. 106.

- ^ Pennec (2012), pp. 83–86, 91–92.

- ^ Cohen (2009), pp. 107–108.

- ^ Pennec (2012), pp. 87–90, 92–93.

- ^ De Lorenzi (2015), pp. 20–21.

- ^ a b c d e f De Lorenzi (2015), p. 22.

- ^ Milkias (2015), p. 474.

- ^ a b c d De Lorenzi (2015), p. 23.

- ^ Bekerie (2013), p. 180.

- ^ Strang (2013), p. 349.

- ^ Rubinkowska (2004), pp. 223–224.

- ^ Rubinkowska (2004), p. 223.

- ^ Omer (1994), p. 97.

- ^ Rubinkowska (2004), p. 223, footnote #9.

- ^ Omer (1994), pp. 97–102.

- ^ College Library, Special Collections. "Hiob Ludolf, Historia Aethiopica (Frankfurt, 1681)". St John's College, Cambridge. Retrieved 29 July 2017.

- ^ Prichard (1851), p. 139.

- ^ Kebede (2003), p. 1.

- ^ Budge (2014), pp. 183–184.

- ^ Salvadore (2012), pp. 493–494.

- ^ a b Kebede (2003), pp. 1–2.

- ^ Salvadore (2012), p. 493.

- ^ a b c Kebede (2003), p. 2.

- ^ Budge (2014), pp. 184–186.

- ^ Budge (2014), pp. 184–185.

- ^ Budge (2014), p. 186.

- ^ Kebede (2003), pp. 2–4.

- ^ College of Arts and Sciences. "Messay Kebede" University of Dayton. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- ^ Kebede (2003), pp. 2–4 & 7.

- ^ Kebede (2003), p. 4.

- ^ Kebede (2003), pp. 5–7.

- ^ a b De Lorenzi (2015), pp. 57–59.

- ^ Adejumobi (2007), p. 59.

- ^ De Lorenzi (2015), pp. 58–59.

- ^ De Lorenzi (2015), p. 58.

- ^ Kropp, Manfred (2006). "Ein später Schüler des Julius Africanus zu Beginn des 20. Jahrhunderts in Äthiopien". In Wallraf, Martin (ed.). Julius Africanus und die christliche Weltchronistik (in German). Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. p. 305. ISBN 978-3-11-019105-9.

- ^ Budge, E. A. Wallis (1928). A History of Ethiopia: Nubia and Abyssinia (Volume I). London: Methuen & Co. p. xv-xvi.

- ^ a b De Lorenzi (2015), p. 120.

- ^ De Lorenzi (2015), pp. 120–121.

- ^ De Lorenzi (2015), p. 121.

- ^ De Lorenzi (2015), pp. 114–116.

- ^ Forclaz (2015), p. 156, note #94.

- ^ Forclaz (2015), p. 156.

- ^ Crummey (2000), p. 319, note #35.

- ^ De Lorenzi (2015), pp. 46, 119–120.

- ^ De Lorenzi (2015), p. 119.

- ^ Professor Emeritus of History at the University of Illinois.

African Studies Association. (17 November 2014). "Donald Crummey (1941–2013)." Retrieved 24 July 2017. - ^ a b Jalata (1996), p. 101.

- ^ De Lorenzi (2015), pp. 11–12, 121–122.

- ^ Bizuneh (2001), pp. 7–8.

- ^ College of Arts and Sciences (faculty page). "Mohammed Hassen Ali: Associate Professor Archived 2017-08-04 at the Wayback Machine ". Georgia State University. Retrieved 25 July 2017.

- ^ Hassen (2015), pp. ix–xii.

- ^ Hassen (2015), pp. x–xi.

- ^ Erlich (2002), pp. 215–216, 225 note #18.

- ^ a b Erlich (2002), p. 11.

- ^ Erlich (2002), pp. 5 & 85.

- ^ a b c d Erlich (2002), p. 216.

- ^ Zewde (2000), p. 5.

- ^ Zewde (2000), p. 10.

- ^ a b Erlich (2002), p. 225, note #19.

Sources

[edit]- Abir, Mordechai (1980), Ethiopia and the Red Sea: The Rise and Decline of the Solomonic Dynasty and Muslim-European Rivalry in the Region, Abingdon, UK: Frank Cass, ISBN 0-7146-3164-7.

- Adejumobi, Saheed A. (2007), The History of Ethiopia, Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, ISBN 978-0-313-32273-0.

- Africanus, Leo (1896) [1600], Brown, Robert (ed.), The History and Description of Africa, vol. 1, translated by John Pory, London: Hakluyt Society.

- Anfray, F. (2000) [1981], "The Civilisation of Aksum from the First to the Seventh Century", Ancient Civilizations of Africa (reprint ed.), Paris: UNESCO, pp. 362–381, ISBN 0-435-94805-9.

- Augustyniak, Zuzanna (2012), "Gudit", in Akyeampong, Emmanuel; Gates, Henry Louis Jr. (eds.), Dictionary of African Biography, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 511–512, ISBN 978-0-19-538207-5.

- Bai, Shouyi (2003), A History of Chinese Muslim, vol. 2, Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju, ISBN 7-101-02890-X.

- Baldridge, Cates (2012), Prisoners of Prester John: The Portuguese Mission to Ethiopia in Search of the Mythical King, 1520-1526, Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, ISBN 978-0-7864-6800-3.

- Bekerie, Ayele (2013), "The 1896 Battle of Adwa and the Forging of the Ethiopian Nation", in Berge, Lars; Taddia, Irma (eds.), Themes in Modern African History and Culture: Festschrift for Tekeste Negash, Padua: Libreria Universitaria, pp. 177–192, ISBN 978-88-6292-363-7.

- Bizuneh, Belete (2001), "Women in Ethiopian History: A Bibliographic Review", Northeast African Studies, 8 (3), Michigan State University Press: 7–32, doi:10.1353/nas.2006.0004, JSTOR 41931268, S2CID 145354978.

- Braukämper, Ulrich (2004), Islamic History and Culture in Southern Ethiopia: Collected Essays, Münster: Lit Verlag, ISBN 3-8258-5671-2.

- Budge, E. A. Wallis (2014) [1928], A History of Ethiopia: Volume I: Nubia and Abyssinia (reprint ed.), Abingdon, UK: Routledge, ISBN 978-1-138-79-155-8.

- Cohen, Leonardo (2009), The Missionary Strategies of the Jesuits in Ethiopia (1555-1632), Wiesbaden, Germany: Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3-447-05892-6.

- Crummey, Donald (2000), Land and Society in the Christian Kingdom of Ethiopia: From the Thirteenth to the Twentieth Century, Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, ISBN 0-252-02482-6.

- De Lorenzi, James (2015), Guardians of the Tradition: Historians and Historical Writing in Ethiopia and Eritrea, Rochester: University of Rochester Press, ISBN 978-1-58046-519-9.

- Erlich, Haggai (2002), The Cross and the River: Ethiopia, Egypt, and the Nile, Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers, ISBN 1-55587-970-5.

- Forclaz, Amalia Ribi (2015), Humanitarian Imperialism: The Politics of Anti-slavery Activism, 1880–1940, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-873303-4.

- Jalata, Asafa (September 1996), "The Struggle for Knowledge: The Case of Emergent Oromo Studies", African Studies Review, 39 (2): 95–123, doi:10.2307/525437, JSTOR 525437, S2CID 146674050.(subscription required)

- Kebede, Messay (2003), "Eurocentrism and Ethiopian Historiography: Deconstructing Semitization", International Journal of Ethiopian Studies, 1 (1), Tsehai Publishers: 1–19.

- Hassen, Mohammed (2015), The Oromo and the Christian Kingdom of Ethiopia, 1300–1700, Woodbridge, UK: James Currey (Boydell & Brewer), ISBN 978-1-84701-117-6.

- Le Grand, M. (1789), Johnson, Samuel (ed.), A voyage to Abyssinia by Father Jerome Lobo a portuguese missionary: containing the history, natural, civil and ecclesiastical of that remote and unfrequented country, translated by Samuel Johnson, London: Elliot and Kay.

- Milkias, Paulos (2015), "Ethiopia", in Falola, Toyin; Jean-Jacques, Daniel (eds.), Africa: An Encyclopedia of Culture and Society, Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, pp. 454–481, ISBN 978-1-59884-665-2.

- Munro-Hay, Stuart C. (1981–1982), "A Tyranny of Sources: The History of Aksum from its Coinage", Northeast African Studies, 3 (3): 1–16

- Omer, Ahmed Hassen (December 1994), "Review: Prowess, Piety and Politics: The Chronicles of Abeto Iyasu and Empress Zawditu of Ethiopia (1909–1930). Recorded by Alaqa Gabra Igziabiher Elyas by R. K. Molvaer", Journal of Ethiopian Studies, 27 (2), Institute of Ethiopian Studies: 97–102, JSTOR 41966040.(subscription required)

- Pennec, Herve (2012) [2011], "Missionary Knowledge in Context: Geographical Knowledge of Ethiopia in Dialogue during the 16th and 17th centuries", Written Culture in a Colonial Context: Africa and the Americas 1500–1900 (reprint ed.), Leiden: Brill, pp. 75–96, ISBN 978-90-04-22389-9.

- Phillipson, David W. (2014) [2012], Foundations of an African Civilisation: Aksum and the Northern Horn, 1000 BC – AD 1300 (paperback ed.), Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Addis Ababa University Press and James Currey, ISBN 978-99944-52-56-9.

- Prichard, James Cowles (1851), Researches Into the Physical History of Mankind, vol. 2 (4th ed.), London: Houlston and Stoneman.

- Riches, Samantha (2015), St George: A Saint for All, London: Reaktion Books, ISBN 978-1-78023-4519.

- Robin, Christian Julien (2012), "Arabia and Ethiopia", in Johnson, Scott Fitzgerald (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Late Antiquity, translated by Arietta Papaconstantinou, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 247–334, ISBN 978-0-19-533693-1.

- Rubinkowska, Hanna (2004), "The History That Never Was: Historiography by Haylä Śǝllase I", in Böll, Verena; et al. (eds.), Studia Aethiopica, Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, pp. 221–233, ISBN 3-447-04891-3.

- Salvadore, Matteo (2012), "Gorgoryos", in Akyeampong, Emmanuel; Gates, Henry Louis Jr. (eds.), Dictionary of African Biography, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 493–494, ISBN 978-0-19-538207-5.

- Smidt, Wolbert (2001), "A Chinese in the Nubian and Abyssinian Kingdoms (8th Century): The visit of Du Huan to Molin-guo and Laobosa" (PDF), Chroniques Yéménites, 9.

- Sobania, Neal W. (2012), "Lalibela", in Akyeampong, Emmanuel; Gates, Henry Louis Jr. (eds.), Dictionary of African Biography, Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 462, ISBN 978-0-19-538207-5.

- Strang, G. Bruce (2013), "Select Biography", in Strang, G. Bruce (ed.), Collision of Empires: Italy's Invasion of Ethiopia and its International Impact, Abingdon, UK: Routledge, pp. 341–374, ISBN 978-1-4094-3009-4.

- Tibebu, Teshale (1995), The Making of Modern Ethiopia, 1896-1974, Lawrenceville, NJ: Red Sea Press, ISBN 1-56902-001-9.

- Yule, Henry (1915), Henry Cordier (ed.), Cathay and the Way Thither: Being a Collection of Medieval Notices of China, Vol I: Preliminary Essay on the Intercourse Between China and the Western Nations Previous to the Discovery of the Cape Route, vol. 1, London: Hakluyt Society.

- Zewde, Bahru (November 2000), "A Century of Ethiopian Historiography", Journal of Ethiopian Studies, 33 (2, Special Issue Dedicated to the XIVth International Conference of Ethiopian Studies), Institute of Ethiopian Studies: 1–26.

Further reading

[edit]- Hrbek, Ivan (1981). "Written sources from the fifteenth century onwards". In Ki-Zerbo, Jacqueline (ed.). Methodology and African Prehistory. General History of Africa. Vol. 1. UNESCO. pp. 120–121. ISBN 0435948075.

External links

[edit]- Bekerie, Ayele (March 8, 2010). "Assumptions and Interpretations of Ethiopian History". Tadias Magazine.

- Dr. Richard Pankhurst, doyen of Ethiopian historians and scholars, has died (Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, Ministry of Foreign Affairs)