Human trafficking

| Part of a series on |

| Forced labour and slavery |

|---|

|

Human trafficking is the trade of humans for the purpose of forced labour, sexual slavery, or commercial sexual exploitation.[1][2]

Human trafficking can occur within a country or trans-nationally. It is distinct from people smuggling, which is characterized by the consent of the person being smuggled.

Human trafficking is condemned as a violation of human rights by international conventions, but legal protection varies globally. The practice has millions of victims around the world.[3][4]

Definition

[edit]

The UN Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, especially Women and Children, which has 117 signatories and 173 parties,[5] defines human trafficking as:

(a) [...] the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of persons, by means of threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation. Exploitation shall include, at a minimum, the exploitation or the prostitution of others or other forms of sexual exploitation, forced labour or services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude or the removal, manipulation or implantation of organs;

(b) The consent of a victim of trafficking in persons to the intended exploitation set forth in sub-paragraph (a) of this article shall be irrelevant where any of the means set forth in subparagraph (a) have been used;

(c) The recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of a child for the purpose of exploitation shall be considered "trafficking in persons" even if this does not involve any of the means set forth in sub-paragraph (a) of this article;

(d) "Child" shall mean any person under eighteen years of age.[6][7]

Prevalence

[edit]There are many different estimates of the number of victims of human trafficking.

According to scholar Kevin Bales, author of Disposable People (2004), estimates that as many as 27 million people are in "modern-day slavery" across the globe.[8][9] In 2008, the U.S. Department of State estimates that 2 million children are exploited by the global commercial sex trade.[10] In the same year, a study classified 12.3 million individuals worldwide as "forced laborers, bonded laborers or sex-trafficking victims". Approximately 1.39 million of these individuals worked as commercial sex slaves, with women and girls comprising 98% of that 1.36 million.[11]

According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), forced labour alone (one component of human trafficking) generates an estimated $150 billion in profits per annum as of 2014.[12] In 2012, the ILO estimated that 21 million victims are trapped in modern-day slavery. Of these, 14.2 million (68%) were exploited for labour, 4.5 million (22%) were sexually exploited, and 2.2 million (10%) were exploited in state-imposed forced labour.[13] The following is the breakdown of profits by sector: $99 billion from commercial sexual exploitation; $34 billion in construction, manufacturing, mining and utilities; $9 billion in agriculture, including forestry and fishing; $8 billion is saved annually by private households that employ domestic workers under conditions of forced labour. Although only 19% of victims are trafficked for sexual exploitation, it makes up 66% of the global earnings of human trafficking.[14] The average annual profits generated by each woman in forced sexual servitude ($100,000) is estimated to be six times more than the average profits generated by each trafficking victim worldwide ($21,800).[14]

Human trafficking is the third largest crime industry in the world, behind drug dealing and arms trafficking, and is the fastest-growing activity of transnational criminal organizations.[15][16][17]

In January 2019, UNODC published the new edition of the Global Report on Trafficking in Persons.[18] The Global Report on Trafficking in Persons 2018 has revealed that 30% of all victims of human trafficking officially detected globally between 2016 and 2018 are children, up 3% from the period 2007–2010. The Global Report recorded victims of 137 different nationalities detected in 142 countries between 2012 and 2016, during which period, 500 different flows were identified. Around half of all trafficking took place within the same region with 42% occurring within national borders. One exception is the Middle East, where most detected victims are East and South Asians. Trafficking victims from East Asia have been detected in more than 64 countries, making them the most geographically dispersed group around the world. There are significant regional differences in the detected forms of exploitation. Countries in Africa and in Asia generally intercept more cases of trafficking for forced labour, while sexual exploitation is somewhat more frequently found in Europe and in the Americas. Additionally, trafficking for organ removal was detected in 16 countries around the world. The Report raises concerns about low conviction rates – 16% of reporting countries did not record a single conviction for trafficking in persons between 2007 and 2010.[5] Significant progress has been made in terms of legislation: as of 2012, 83% of countries had a law criminalizing trafficking in persons in accordance with the Protocol.[19]

Overview

[edit]

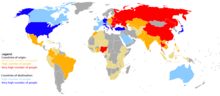

Countries of origin

- Yellow: Moderate number of people

- Orange: High number of people

- Red: Very high number of people

Countries of destination

- Light blue: High number of people

- Blue: Very high number of people

- Gray: No data

- Green: Trafficking is illegal and rare

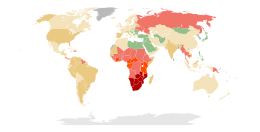

- Yellow: Trafficking is illegal but problems still exist

- Purple: Trafficking is illegal but is still practiced

- Blue: Trafficking is limitedly illegal and is practiced

- Red: Trafficking is not illegal and is commonly practiced[20]

According to the 2018 and 2019 editions of the annual Trafficking in Persons Reports issued by the U.S. State Department: Belarus, Iran, Russia, and Turkmenistan remain among the worst countries when it comes to providing protection against human trafficking and forced labour.[21][22]

In 2015, the National Human Trafficking Resource Center hotline received reports of more than 5,000 potential human trafficking cases in the U.S. Children comprise up to one-third of all victims, while women make up more than half.[23]

Singapore appears to be a popular destination for human trafficking with women and girls from India, Thailand, the Philippines and China.[24] In November 2019, two Indian nationals were convicted for exploiting migrant women, making it the first conviction in the state.[25]

Types of trafficking

[edit]Trafficking arrangements are sometimes structured as a work contract, but with no or low payment, or on terms which are highly exploitative. They may also be structured as debt bondage, with the victim not being permitted or able to pay off the debt. It may encompass providing a spouse in the context of forced marriage,[26][27][28] or the extraction of organs or tissues,[29][30] including for surrogacy and ova removal.[31]

Trafficking of children

[edit]Trafficking of children involves the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harboring, or receipt of children for the purpose of exploitation. Commercial sexual exploitation of children can take many forms, including forcing a child into prostitution[32][33] or other forms of sexual activity or child pornography. Child exploitation may also involve forced labour or services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude, the removal of organs,[34] illicit international adoption, trafficking for early marriage, recruitment as child soldiers, for use in begging or as athletes (such as child camel jockeys[35] or football trafficking.)[36]

Child labour is a form of work that may be hazardous to the physical, mental, spiritual, moral, or social development of children and can interfere with their education. According to the International Labour Organization, the global number of children involved in child labour fell during the twelve years to 2012 – it has declined by one third, from 246 million in 2000 to 168 million children in 2012.[37] Sub-Saharan Africa is the region with the highest incidence of child labour, while the largest numbers of child-workers are found in Asia and the Pacific.[37]

IOM statistics indicate that a significant minority (35%) of trafficked persons it assisted in 2011 were less than 18 years of age, which is roughly consistent with estimates from previous years. It was reported in 2010 that Thailand and Brazil were considered to have the worst child sex trafficking records.[38]

Traffickers in children may take advantage of the parents' extreme poverty. Parents may sell children to traffickers in order to pay off debts or gain income, or they may be deceived concerning the prospects of training and a better life for their children. They may sell their children into labour, sex trafficking, or illegal adoptions, although scholars have urged a nuanced understanding and approach to the issue - one that looks at broader socio-economic and political contexts.[39][40][41]

The adoption process, legal and illegal, when abused can sometimes result in cases of trafficking of babies and pregnant women around the world.[42] In David M. Smolin's 2005 papers on child trafficking and adoption scandals between India and the United States,[43][44] he presents the systemic vulnerabilities in the inter-country adoption system that makes adoption scandals predictable.

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child at Article 34, states, "States Parties undertake to protect the child from all forms of sexual exploitation and sexual abuse".[45] In the European Union, commercial sexual exploitation of children is subject to a directive – Directive 2011/92/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 December 2011 on combating the sexual abuse and sexual exploitation of children and child pornography.[46]

The Hague Convention on Protection of Children and Co-operation in Respect of Intercountry Adoption (or Hague Adoption Convention) is an international convention dealing with international adoption, that aims at preventing child laundering, child trafficking, and other abuses related to international adoption.[47]

The Optional Protocol on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict seeks to prevent forceful recruitment (e.g. by guerrilla forces) of children for use in armed conflicts.[48]

Sex trafficking

[edit]

The International Labour Organization claims that forced labour in the sex industry affects 4.5 million people worldwide.[49] Most victims find themselves in coercive or abusive situations from which escape is both difficult and dangerous.[50]

Trafficking for sexual exploitation was formerly thought of as the organized movement of people, usually women, between countries and within countries for sex work with the use of physical coercion, deception and bondage through forced debt. However, the Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000 (US)[51] does not require movement for the offence. The issue becomes contentious when the element of coercion is removed from the definition to incorporate facilitation of consensual involvement in prostitution. For example, in the United Kingdom, the Sexual Offences Act 2003 incorporated trafficking for sexual exploitation but did not require those committing the offence to use coercion, deception or force, so that it also includes any person who enters the UK to carry out sex work with consent as having been "trafficked".[52] In addition, any minor involved in a commercial sex act in the US while under the age of 18 qualifies as a trafficking victim, even if no force, fraud or coercion is involved, under the definition of "Severe Forms of Trafficking in Persons" in the US Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000.[51][53]

Trafficked women and children are often promised work in the domestic or service industry, but instead are sometimes taken to brothels where they are required to undertake sex work, while their passports and other identification papers are confiscated. They may be beaten or locked up and promised their freedom only after earning – through prostitution – their purchase price, as well as their travel and visa costs.[54][55]

Forced marriage

[edit]A forced marriage is a marriage where one or both participants are married without their freely given consent.[56] Servile marriage is defined as a marriage involving a person being sold, transferred or inherited into that marriage.[57] According to ECPAT, "Child trafficking for forced marriage is simply another manifestation of trafficking and is not restricted to particular nationalities or countries".[26]

Forced marriages have been described as a form of human trafficking in certain situations and certain countries, such as China and its Southeast Asian neighbours from which many women are moved to China, sometimes through promises of work, and forced to marry Chinese men. Ethnographic research with women from Myanmar[58] and Cambodia[59] found that many women eventually get used to their life in China and prefer it to the one they had in their home countries. Furthermore, legal scholars have noted that transnational marriage brokering was never intended to be considered trafficking by the drafters of the Palermo Protocol.[60]

Labour trafficking

[edit]Labour trafficking is the movement of persons for the purpose of forced labour and services.[61] It may involve bonded labour, involuntary servitude, domestic servitude, and child labour.[61] Labour trafficking happens most often within the domain of domestic work, agriculture, construction, manufacturing and entertainment; and migrant workers and indigenous people are especially at risk of becoming victims.[49] People smuggling is a related practice which is characterized by the consent of the person being smuggled.[62] Smuggling situations can descend into human trafficking through coercion and exploitation.[63] They are known to traffic people for the exploitation of their labour, for example, as transporters.[64]

Bonded labour, or debt bondage, is probably the least known form of labour trafficking today, and yet is the most widely used method of enslaving people. Victims become "bonded" when their labour, the labour which they themselves hired and the tangible goods they have bought are demanded as a means of repayment for a loan or service whose terms and conditions have not been defined, or where the value of the victims' services is not applied toward the liquidation of the debt. Generally, the value of their work is greater than the original sum of money "borrowed".[65]

Forced labour is a situation in which people are forced to work against their will under the threat of violence or some other form of punishment; their freedom is restricted and a degree of ownership is exerted. Men and women are at risk of being trafficked for unskilled work, which globally generates US$31 billion according to the International Labour Organization.[66] Forms of forced labour can include domestic servitude, agricultural labour, sweatshop factory labour, janitorial, food service and other service industry labour, and begging.[65] Some of the products that can be produced by forced labour are: clothing, cocoa, bricks, coffee, cotton, and gold.[67]

Organ trade

[edit]Trafficking in organs is a form of human trafficking. It can take different forms. In some cases, the victim is compelled into giving up an organ. In other cases, the victim agrees to sell an organ in exchange of money/goods, but is not paid (or paid less). Finally, the victim may have the organ removed without the victim's knowledge (usually when the victim is treated for another medical problem/illness – real or orchestrated problem/illness). Migrant workers, homeless persons, and illiterate persons are particularly vulnerable to this form of exploitation. Trafficking of organs is an organized crime, involving several offenders:[68]

- the recruiter

- the transporter

- the medical staff

- the middlemen/contractors

- the buyers

Trafficking for organ trade often seeks kidneys. Trafficking in organs is a lucrative trade because in many countries the waiting lists for patients who need transplants are very long.[69] Some solutions have been proposed to help counter it.

Fraud factory

[edit]Most fraud factories operate in Southeast Asia (including Cambodia, Myanmar, or Laos), and are typically run by a criminal gang. Fraud factory operators lure foreign nationals to scam hubs, where they are forced to scam internet users around the world into fraudulently buying cryptocurrencies or withdrawing cash, via social media and online dating apps. Trafficking victims' passports are confiscated, and they are threatened with organ theft, organ harvesting or forced prostitution if they do not scam sufficiently successfully.

Causes

[edit]A complex set of factors fuel human trafficking, including poverty, unemployment, social norms that discriminate against women, institutional challenges, and globalization.

Poverty and globalization

[edit]Poverty and lack of educational and economic opportunities in one's hometown may lead women to voluntarily migrate and then be involuntarily trafficked into sex work.[70][71] As globalization opened up national borders to greater exchange of goods and capital, labour migration also increased. Less wealthy countries have fewer options for livable wages. The economic impact of globalization pushes people to make conscious decisions to migrate and be vulnerable to trafficking. Gender inequalities that hinder women from participating in the formal sector also push women into informal sectors.[72]

Long waiting lists for organs in the United States and Europe created a thriving international black market. Traffickers harvest organs, particularly kidneys, to sell for large profit and often without properly caring for or compensating the victims. Victims often come from poor, rural communities and see few other options than to sell organs illegally.[73] Wealthy countries' inability to meet organ demand within their own borders perpetuates trafficking. By reforming their internal donation system, Iran achieved a surplus of legal donors and provides an instructive model for eliminating both organ trafficking and shortage.[74]

Globalization and the rise of internet technology has also facilitated human trafficking. Online classified sites and social networks such as Craigslist have been under intense scrutiny for being used by clients and traffickers in facilitating sex trafficking and sex work in general. Traffickers use explicit sites (e.g. Craigslist, Backpage, MySpace) to market, recruit, sell, and exploit women. Facebook, Twitter, and other social networking sites are suspected for similar uses. According to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, online classified ads reduce the risks of finding prospective customers.[75] Studies have identified the Internet as the single biggest facilitator of commercial sex trade, although it is difficult to ascertain which women advertised are sex trafficking victims.[76] Traffickers and pimps use the Internet to recruit minors, since Internet and social networking sites usage have significantly increased especially among children.[77] At the same time, critical scholars have questioned the extent of the role of internet in human trafficking and have cautioned against sweeping generalisations and urged more research.[78]

While globalization fostered new technologies that may exacerbate human trafficking, technology can also be used to assist law enforcement and anti-trafficking efforts. A study was done on online classified ads surrounding the Super Bowl. A number of reports have noticed increase in sex trafficking during previous years of the Super Bowl.[79] For the 2011 Super Bowl XLV held in Dallas, Texas, the Backpage for Dallas area experienced a 136% increase on the number of posts in the Adult section on Super Bowl Sunday; in contrast, Sundays typically have the lowest number of posts. Researchers analyzed the most salient terms in these online ads, which suggested that many escorts were traveling across state lines to Dallas specifically for the Super Bowl, and found that the self-reported ages were higher than usual. Twitter was another social networking platform studied for detecting sex trafficking. Digital tools can be used to narrow the pool of sex trafficking cases, albeit imperfectly and with uncertainty.[80]

However, there has been no evidence found actually linking the Super Bowl – or any other sporting event – to increased trafficking or prostitution.[81][82][83]

Political and institutional

[edit]Corrupt and inadequately trained police officers can be complicit in human trafficking and/or commit violence against sex workers, including trafficked victims.[84] Human traffickers often incorporate abuse of the legal system into their control tactics by making threats of deportation[85] or by turning victims into the authorities, possibly resulting in the incarceration of the victims.[86]

Anti-trafficking agendas from different groups can also be in conflict. In the movement for sex workers' rights, sex workers establish unions and organizations, which seek to eliminate trafficking. However, law enforcement also seek to eliminate trafficking and to prosecute trafficking, and their work may infringe on sex workers' rights and agency. For example, the sex workers union DMSC (Durbar Mahila Samanwaya Committee) in Kolkata, India, has "self-regulatory boards" (SRBs) that patrol the red light districts and assist girls who are underage or trafficked. The union opposes police intervention and interferes with police efforts to bring minor girls out of brothels, on the grounds that police action might have an adverse impact on non-trafficked sex workers, especially because police officers in many places are corrupt and violent in their operations.[84] A recent seven-country research by the Global Alliance Against Traffic in Women found that sex worker organizations around the world assist women in the industry who are trafficked and should be considered as allies in anti-trafficking work.[87]

Criminalization of sex work also may foster the underground market for sex work and enable sex trafficking.[70]

Difficult political situations such as civil war and social conflict are push factors for migration and trafficking. A study reported that larger countries, the richest and the poorest countries, and countries with restricted press freedom are likely to have higher levels of trafficking. Specifically, being in a transitional economy made a country nineteen times more likely to be ranked in the highest trafficking category, and gender inequalities in a country's labour market also correlated with higher trafficking rates.[88]

The annual U.S. State Department Trafficking in Persons Report for 2013 cited Russia and China as among the worst offenders in combatting forced labour and sex trafficking, raising the possibility of US sanctions being leveraged against these countries.[89] In 1997 alone as many as 175,000 young women from Russia, the former Soviet Union and Eastern and Central Europe were sold as commodities in the sex markets of the developed countries in Europe and the Americas.[90]

Commercial demand for sex

[edit]Abolitionists who seek an end to sex trafficking explain the nature of sex trafficking as an economic supply and demand model. In this model, male demand for prostitutes leads to a market of sex work, which, in turn, fosters sex trafficking, the illegal trade and coercion of people into sex work, and pimps and traffickers become 'distributors' who supply people to be sexually exploited. The demand for sex trafficking can also be facilitated by some pimps' and traffickers' desire for women whom they can exploit as workers because they do not require wages, safe working circumstances, and agency in choosing customers.[70] The link between demand for paid sex and incidences of human trafficking, as well as the "demand for trafficking" discourse more broadly, have never been proven empirically and have been seriously questioned by a number of scholars and organisations.[91][92][93][94] To this day, the idea that trafficking is fuelled by demand remains poorly conceptualised and based on assumptions rather than evidence.

Vulnerable groups

[edit]The U.S. State Department's annual Trafficking in Persons Report for 2016 stated that "refugees and migrants; lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex (LGBTI) individuals; religious minorities; people with disabilities; and those who are stateless" are the most at-risk for human trafficking.[95] Additionally, in its Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children, the United Nations notes that women and children are particularly at risk for human trafficking and revictimization. The Protocol requires State Parties not only to enact measures that prevent human trafficking but also to address the factors that exacerbate women and children's vulnerability, including "poverty, underdevelopment and lack of equal opportunity."[96]

Consequences

[edit]Human trafficking victims face threats of violence from many sources, including customers, pimps, brothel owners, madams, traffickers, and corrupt local law enforcement officials and even from family members who do not want to have any link with them.[97] Because of their potentially complicated legal status and their potential language barriers, the arrest or fear of arrest creates stress and other emotional trauma for trafficking victims.[98][99] The challenges facing victims often continue after their removal from coercive exploitation.[100] In addition to coping with their past traumatic experiences, former trafficking victims often experience social alienation in the host and home countries. Stigmatization, social exclusion, and intolerance often make it difficult for former victims to integrate into their host community, or to reintegrate into their former community. Accordingly, one of the central aims of protection assistance, is the promotion of reintegration.[101][102] Too often however, governments and large institutional donors offer little funding to support the provision of assistance and social services to former trafficking victims.[103] As the victims are also pushed into drug trafficking, many of them face criminal sanctions also.[104]

Psychological

[edit]Short-term impact

[edit]The use of coercion by perpetrators and traffickers involves the use of extreme control. Perpetrators expose the victim to high amounts of psychological stress induced by threats, fear, and physical and emotional violence. Tactics of coercion are reportedly used in three phases of trafficking: recruitment, initiation, and indoctrination.[105] During the initiation phase, traffickers use foot-in-the-door techniques of persuasion to lead their victims into various trafficking industries. This manipulation creates an environment where the victim becomes completely dependent upon the authority of the trafficker.[105] Traffickers take advantage of family dysfunction, homelessness, and history of childhood abuse to psychologically manipulate women and children into the trafficking industry.[106]

One form of psychological coercion particularly common in cases of sex trafficking and forced prostitution is Stockholm syndrome. Many women entering into the sex trafficking industry are minors who have already experienced prior sexual abuse.[107] Traffickers take advantage of young girls by luring them into the business through force and coercion, but more often through false promises of love, security, and protection. This form of coercion works to recruit and initiate the victim into the life of a sex worker, while also reinforcing a "trauma bond", also known as Stockholm syndrome. Stockholm syndrome is a psychological response where the victim becomes attached to his or her perpetrator.[107][108]

The goal of a trafficker is to turn a human being into a slave. To do this, perpetrators employ tactics that can lead to the psychological consequence of learned helplessness for the victims, where they sense that they no longer have any autonomy or control over their lives.[106] Traffickers may hold their victims captive, expose them to large amounts of alcohol or use drugs, keep them in isolation, or withhold food or sleep.[106] During this time the victim often begins to feel the onset of depression, guilt and self-blame, anger and rage, and sleep disturbances, PTSD, numbing, and extreme stress. Under these pressures, the victim can fall into the hopeless mental state of learned helplessness.[105][109][110]

For victims specifically trafficked for the purpose of forced prostitution and sexual slavery, initiation into the trade is almost always characterized by violence.[106] Traffickers employ practices of sexual abuse, torture, brainwashing, repeated rape and physical assault until the victim submits to his or her fate as a sexual slave. Victims experience verbal threats, social isolation, and intimidation before they accept their role as a prostitute.[111]

For those enslaved in situations of forced labor, learned helplessness can also manifest itself through the trauma of living as a slave. Reports indicate that captivity for the person and financial gain of their owners adds additional psychological trauma. Victims are often cut off from all forms of social connection, as isolation allows the perpetrator to destroy the victim's sense of self and increase his or her dependence on the perpetrator.[105]

Long-term impact

[edit]Human trafficking victims may experience complex trauma as a result of repeated cases of intimate relationship trauma over long periods of time including, but not limited to, sexual abuse, domestic violence, forced prostitution, or gang rape. Complex trauma involves multifaceted conditions of depression, anxiety, self-hatred, dissociation, substance abuse, self-destructive behaviors, medical and somatic concerns, despair, and revictimization. Psychology researchers report that, although similar to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), complex trauma is more expansive in diagnosis because of the effects of prolonged trauma.[112]

Victims of sex trafficking often get "branded"[113] by their traffickers or pimps. These tattoos usually consist of bar codes or the trafficker's name or rules. Even if a victim escapes their trafficker's control or gets rescued, these tattoos are painful reminders of their past and result in emotional distress. Removing or covering these tattoos can potentially cost survivors great sums of money.[114][115]

Psychological reviews have shown that the chronic stress experienced by many victims of human trafficking can compromise the immune system.[106] Several studies found that chronic stressors (like trauma or loss) suppressed cellular and humoral immunity.[109] Victims may develop sexually transmitted infections and HIV/AIDS.[116] Perpetrators frequently use substance abuse as a means to control their victims, which leads to compromised health, self-destructive behavior, and long-term physical harm.[117] Furthermore, victims have reported treatment similar to torture, where their bodies are broken and beaten into submission.[117][118]

Children are especially vulnerable to these developmental and psychological consequences of trafficking due to their age. In order to gain complete control of the child, traffickers often destroy the physical and mental health of the children through persistent physical and emotional abuse.[119] Victims experience severe trauma on a daily basis that devastates the healthy development of self-concept, self-worth, biological integrity, and cognitive functioning.[120] Children who grow up in environments of constant exploitation frequently exhibit antisocial behavior, over-sexualized behavior, self-harm, aggression, distrust of adults, dissociative disorders, substance abuse, complex trauma, and attention deficit disorders.[108][119][120][121] Stockholm syndrome is also a common problem for trafficked girls, which can hinder them from both trying to escape, and moving forward in psychological recovery programs.[118]

Although 98% of the sex trade is composed of women and girls,[118] there is an effort to gather empirical evidence about the psychological impact of abuse common in sex trafficking upon young boys.[120][122] Boys often will experience forms of post-traumatic stress disorder, but also additional stressors of social stigma of homosexuality associated with sexual abuse for boys, and externalization of blame, increased anger, and desire for revenge.

HIV/AIDS

[edit]

| No data <0.10 0.10–0.5 0.5–1 | 1–5 5–15 15–50 |

Sex trafficking increases the risk of contracting HIV/AIDS.[124] The HIV/AIDS pandemic can be both a cause and a consequence of sex trafficking. On one hand, children are sought by customers because they are perceived as being less likely to be HIV positive, and this demand leads to child sex trafficking. On the other hand, trafficking leads to the proliferation of HIV, because victims often cannot protect themselves properly and get infected.[125]

Economic impacts

[edit]Organised criminal groups invest in a wide range of legitimate businesses to conceal and launder the profits earned from human trafficking. Fair competition may be undermined when human trafficking victims are exploited for cheap labour, driving down production costs, thereby indirectly causing a negative economic imbalance.[126] This can also depress wages for legal labourers.[127] According to the United Nations, human trafficking can be closely integrated into legal businesses, including the tourism industry, agriculture, hotel and airline operations, and leisure and entertainment businesses.[128][129] Related crimes associated with human trafficking reportedly include fraud, extortion, racketeering, money laundering, bribery, drug trafficking, arms trafficking, car theft, migrant smuggling, kidnapping, document forgery, and gambling.[130][129]

Other economic costs that have been associated with human trafficking include lost labour productivity, human resources, taxable revenues, and migrant remittances, as well as unlawfully redistributed wealth and heightened law enforcement and public health costs.[129]

Countermeasures

[edit]

In 2009, the International Organization for Migration launched the Buy Responsibly awareness raising campaign against trafficking.[132] The United Nations Organization also takes an active part in the anti-trafficking effort, particularly through the Sustainable Development Goal 5.[133] In early 2016, the Permanent Mission of the Republic of Kazakhstan to the United Nations held an interactive discussion entitled "Responding to Current Challenges in Trafficking in Human Beings".[134]

Anti-trafficking awareness and fundraising campaigns constitute a significant portion of anti-trafficking initiatives.[135] The 24 Hour Race is one such initiative that focuses on increasing awareness among high school students in Asia.[136] The Blue Campaign is another anti-trafficking initiative that works with the U.S. Department of Homeland Security to combat human trafficking and bring freedom to exploited victims.[137] However, critical commentators have pointed out that initiatives such as these aimed at "raising awareness" do little, if anything, to actually reduce instances of trafficking.[138][139][140]

The 3P Anti-trafficking Policy Index measured the effectiveness of government policies to fight human trafficking based on an evaluation of policy requirements prescribed by the United Nations Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, especially Women and Children (2000).[141]

In 2014, for the first time in history major leaders of many religions, Buddhist, Anglican, Catholic, and Orthodox Christian, Hindu, Jewish, and Muslim, met to sign a shared commitment against modern-day slavery; the declaration they signed calls for the elimination of slavery and human trafficking by 2020.[142] The signatories were: Pope Francis, Mātā Amṛtānandamayī (also known as Amma), Bhikkhuni Thich Nu Chân Không (representing Zen Master Thích Nhất Hạnh), Datuk K Sri Dhammaratana, Chief High Priest of Malaysia, Rabbi Abraham Skorka, Rabbi David Rosen, Abbas Abdalla Abbas Soliman, Undersecretary of State of Al Azhar Alsharif (representing Mohamed Ahmed El-Tayeb, Grand Imam of Al-Azhar), Grand Ayatollah Mohammad Taqi al-Modarresi, Sheikh Naziyah Razzaq Jaafar, Special advisor of Grand Ayatollah (representing Grand Ayatollah Sheikh Basheer Hussain al Najafi), Sheikh Omar Abboud, Justin Welby, Archbishop of Canterbury, and Metropolitan Emmanuel of France (representing Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew).[142]

The UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) has further assisted many non-governmental organizations in their fight against human trafficking. The 2006 armed conflict in Lebanon, which saw 300,000 domestic workers from Sri Lanka, Ethiopia and the Philippines jobless and targets of traffickers, led to an emergency information campaign with NGO Caritas Migrant to raise human-trafficking awareness. Additionally, an April 2006 report, Trafficking in Persons: Global Patterns, helped to identify 127 countries of origin, 98 transit countries and 137 destination countries for human trafficking. To date, it is the second most frequently downloaded UNODC report. Continuing into 2007, UNODC supported initiatives like the Community Vigilance project along the border between India and Nepal, as well as provided subsidy for NGO trafficking prevention campaigns in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia.[143]

UNODC efforts to motivate action launched the Blue Heart Campaign Against Human Trafficking on 6 March 2009,[144] which Mexico launched its own national version of in April 2010.[145][146] The campaign encourages people to show solidarity with human trafficking victims by wearing the blue heart, similar to how wearing the red ribbon promotes transnational HIV/AIDS awareness.[147] On 4 November 2010, U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon launched the United Nations Voluntary Trust Fund for Victims of Trafficking in Persons to provide humanitarian, legal and financial aid to victims of human trafficking with the aim of increasing the number of those rescued and supported, and broadening the extent of assistance they receive.[148]

In 2013, the United Nations designated July 30 as the World Day against Trafficking in Persons.[149]

There are a number of international treaties concerning human trafficking:

- Supplementary Convention on the Abolition of Slavery, entered into force in 1957

- Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, especially Women and Children

- Protocol against the Smuggling of Migrants by Land, Sea and Air

- Optional Protocol on the Sale of Children, Child Prostitution and Child Pornography

- ILO Forced Labour Convention, 1930 (No. 29)

- ILO Abolition of Forced Labour Convention, 1957 (No. 105)

- ILO Minimum Age Convention, 1973 (No. 138)

- ILO Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention, 1999 (No. 182)

- Inter-American Convention on International Traffic in Minors

In countermeasures victims began using the sign language help sign.

United States

[edit]The enactment of the Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act (TVPA) in 2000 by the United States Congress and its subsequent re-authorizations established the Department of State's Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons, which engages with foreign governments to fight human trafficking and publishes a Trafficking in Persons Report annually. The Trafficking in Persons Report evaluates each country's progress in anti-trafficking and places each country onto one of three tiers based on their governments' efforts to comply with the minimum standards for the elimination of trafficking as prescribed by the TVPA.[150] However, questions have been raised by critical anti-trafficking scholars about the basis of this tier system, its heavy focus on compliance with state department protocols, its overreliance on prosecutions and convictions as success in combating trafficking,[60] its use to serve US political and economic interests and lack of systemic analysis,[151] and its failure to consider "risk" and the likely prevalence of trafficking when rating the efforts of diverse countries.[152]

- Blue – Tier 1

- Yellow – Tier 2

- Orange – Tier 2½

- Red – Tier 3

- Brown – Tier special

In 2002, Derek Ellerman and Katherine Chon founded a non-government organization called the Polaris Project to combat human trafficking. In 2007, Polaris instituted the National Human Trafficking Resource Center (NHTRC) where[154] callers can report tips and receive information on human trafficking.[155][156]

In 2007, the U.S. Senate designated 11 January as a National Day of Human Trafficking Awareness in an effort to raise consciousness about this global, national and local issue.[157] In 2010, 2011, 2012 and 2013, President Barack Obama proclaimed January as National Slavery and Human Trafficking Prevention Month.[158]

In 2014, DARPA funded the Memex program with the explicit goal of combating human trafficking via domain-specific searches.[159] The advanced search capacity, including its ability to reach into the dark web allows for prosecution of human trafficking cases, which can be difficult to prosecute due to the fraudulent tactics of the human traffickers.[160]

Council of Europe

[edit]On 3 May 2005, the Committee of Ministers adopted the Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings (CETS No. 197).[161] The convention was opened for signature in Warsaw on 16 May 2005 on the occasion of the 3rd Summit of Heads of State and Government of the Council of Europe. On 24 October 2007, the convention received its tenth ratification thereby triggering the process whereby it entered into force on 1 February 2008. As of June 2017, the convention has been ratified by 47 states (including Belarus, a non-Council of Europe state), with Russia being the only state to not have ratified (nor signed).[162] The convention is not restricted to Council of Europe member states; non-member states and the European Union also have the possibility of becoming Party to the convention. In 2013, Belarus became the first non-Council of Europe member state to accede to the convention.[163][164]

Complementary protection against sex trafficking of children is ensured through the Council of Europe Convention on the Protection of Children against Sexual Exploitation and Sexual Abuse (signed in Lanzarote, 25 October 2007). The Convention entered into force on 1 July 2010.[165] As of November 2020, the convention has been ratified by 47 states, with Ireland having signed but not yet ratified.[166]

In addition, the European Court of Human Rights of the Council of Europe in Strasbourg has passed judgments concerning trafficking in human beings which violated obligations under the European Convention on Human Rights: Siliadin v. France,[167] judgment of 26 July 2005, and Rantsev v. Cyprus and Russia,[168] judgment of 7 January 2010.

Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe

[edit]In 2003, the OSCE established an anti-trafficking mechanism aimed at raising public awareness of the problem and building the political will within participating states to tackle it effectively.

The OSCE actions against human trafficking are coordinated by the Office of the Special Representative for Combating the Traffic of Human Beings.[169] In January 2010, Maria Grazia Giammarinaro became the OSCE Special Representative and Co-ordinator for Combating Trafficking in Human Beings.

India

[edit]

In India, the trafficking in persons for commercial sexual exploitation, forced labor, forced marriages and domestic servitude is considered an organized crime. The Government of India applies the Criminal Law (Amendment) Act 2013, active from 3 February 2013, as well as Section 370 and 370A IPC, which defines human trafficking and "provides stringent punishment for human trafficking; trafficking of children for exploitation in any form including physical exploitation; or any form of sexual exploitation, slavery, servitude or the forced removal of organs." Additionally, a Regional Task Force implements the SAARC Convention on the prevention of Trafficking in Women and Children.[170]

Shri R.P.N. Singh, India's Minister of State for Home Affairs, launched a government web portal, the Anti Human Trafficking Portal, on 20 February 2014. The official statement explained that the objective of the on-line resource is for the "sharing of information across all stakeholders, States/UTs [Union Territories] and civil society organizations for effective implementation of Anti Human Trafficking measures."[170] The key aims of the portal are:

- Aid in the tracking of cases with inter-state ramifications.

- Provide comprehensive information on legislation, statistics, court judgements, United Nations Conventions, details of trafficked people and traffickers and rescue success stories.

- Provide connection to "Trackchild", the National Portal on Missing Children that is operational in many states.[170]

Also on 20 February, the Indian government announced the implementation of a Comprehensive Scheme that involves the establishment of Integrated Anti Human Trafficking Units (AHTUs) in 335 vulnerable police districts throughout India, as well as capacity building that includes training for police, prosecutors and judiciary. As of the announcement, 225 Integrated AHTUs had been made operational, while 100 more AHTUs were proposed for the forthcoming financial year.[170]

Singapore

[edit]As of 2016, Singapore acceded to the United Nations Trafficking in Persons Protocol and affirmed on 28 September 2015, the commitment to combat people trafficking, especially women and children.[171]

According to the U.S. State Department's 2018 Trafficking in Persons Report, Singapore is making significant efforts to eliminate human trafficking as it imposes strong sentences against convicted traffickers, improve freedom of movement for adult victims and increases migrant workers' awareness of their rights. However, it still does not meet the minimum standards as numerous migrant workers' work conditions indicate labor trafficking, but conviction is not secured.[172]

Criticism

[edit]Both the public debate on human trafficking and the actions undertaken by the anti-human traffickers have been criticized by numerous scholars and experts, including Zbigniew Dumienski, a former research analyst at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies.[173] The criticism touches upon statistics and data on human trafficking, the concept itself, and anti-trafficking measures.

Problems with statistics and data

[edit]According to a former Wall Street Journal columnist, figures used in human trafficking estimates rarely have identifiable sources or transparent methodologies behind them and in most (if not all) instances, they are mere guesses.[174][175][176] Dumienski and Laura Agustin argue that this is a result of the fact that it is impossible to produce reliable statistics on a phenomenon happening in the shadow economy.[173][177] According to a UNESCO Bangkok researcher, statistics on human trafficking may be unreliable due to overrepresentation of sex trafficking. As an example, he cites flaws in Thai statistics, which discount men from their official numbers because by law they cannot be considered trafficking victims due to their gender.[178]

A 2012 article in the International Communication Gazette examined the effect of two communication theories (agenda-building and agenda-setting) on media coverage on human trafficking in the United States and Britain. The article analyzed four newspapers, including the Guardian and the Washington Post, and categorized the content into various categories. Overall, the article found that sex trafficking was the most reported form of human trafficking by the newspapers that were analyzed (p. 154). Many of the other stories on trafficking were non-specific.[179]

Problems with the concept

[edit]According to Zbigniew Dumienski, the very concept of human trafficking is murky and misleading.[173] It has been argued that while human trafficking is commonly seen as a monolithic crime, in reality it may be an act of illegal migration that involves various different actions: some of them may be criminal or abusive, but others often involve consent and are legal.[173] Laura Agustin argues that not everything that might seem abusive or coercive is considered as such by the migrant. For instance, she states that: "would-be travellers commonly seek help from intermediaries who sell information, services and documents. When travellers cannot afford to buy these outright, they go into debt".[177] Dumienski says that while these debts might indeed be on very harsh conditions, they are usually incurred on a voluntary basis.[173] British scholar Julia O'Connell Davidson has advanced the same argument.[180] Furthermore, anti-trafficking actors often conflate clandestine migratory movements or voluntary sex work with forms of exploitation covered in human trafficking definitions, ignoring the fact that a migratory movement is not a requirement for human trafficking victimization.

The critics of the current approaches to trafficking say that a lot of the violence and exploitation faced by irregular migrants derives precisely from the fact that their migration and their work are illegal and not primarily because of trafficking.[181]

The international Save the Children organization also stated: "The issue, however, gets mired in controversy and confusion when prostitution too is considered as a violation of the basic human rights of both adult women and minors, and equal to sexual exploitation per se … trafficking and prostitution become conflated with each other … On account of the historical conflation of trafficking and prostitution both legally and in popular understanding, an overwhelming degree of effort and interventions of anti-trafficking groups are concentrated on trafficking into prostitution."[182]

Claudia Aradau of the Open University claims that NGOs involved in anti-sex trafficking often employ "politics of pity", which promotes that all trafficked victims are completely guiltless, fully coerced into sex work, and experience the same degrees of physical suffering. One critic identifies two strategies that gain pity: denunciation – attributing all violence and suffering to the perpetrator – and sentiment – exclusively depicting the suffering of the women. NGOs' use of images of unidentifiable women suffering physically help display sex trafficking scenarios as all the same. She points out that not all trafficking victims have been abducted, abused physically, and repeatedly raped, unlike popular portrayals.[183] A study of the relationships between individuals who are defined as sex-trafficking victims by virtue of having a procurer (especially minors) concluded that assumptions about victimization and human trafficking do not do justice to the complex and often mutual relationships that exist between sex workers and their third parties.[184]

Another common critique is that the concept of human trafficking focuses only on the most extreme forms of exploitation and diverts attention and resources away from more "everyday" but arguably much more widespread forms of exploitation and abuse that occur as part of the normal functioning of the economy. As Quirk, Robinson, and Thibos write, "It is not always possible to sharply separate human trafficking from everyday abuses, and problems arise when the former is singled out while the latter is pushed to the margins."[185] O'Connell Davidson too argues that the lines between the crimes of human trafficking/modern slavery and the legally sanctioned exploitation of migrants (such as lower wages or restrictions on freedom of movement and employment) is blurry.[180]

Problems with anti-trafficking measures

[edit]Groups like Amnesty International have been critical of insufficient or ineffective government measures to tackle human trafficking. Criticism includes a lack of understanding of human trafficking issues, poor identification of victims and a lack of resources for the key pillars of anti-trafficking – identification, protection, prosecution and prevention. For example, Amnesty International has called the UK government's new anti-trafficking measures "not fit for purpose".[186]

Collateral damage

[edit]Rights groups have called attention to the negative impact that the implementation of anti-trafficking measures have on the human rights of various groups, especially migrants, sex workers, and trafficked persons themselves. The Global Alliance Against Traffic in Women drew attention to this "collateral damage" in 2007.[187] These negative impacts include various restrictions on women's right to migrate and undertake certain jobs,[188][189] suspicion and harassment at international borders of women travelling alone,[190] raids at sex work venues and detention, fines and harassment of sex workers (see below section on the use of raids), assistance to trafficked persons made conditional on their cooperation with law enforcement and forced confinement of trafficked persons in shelters, and many more.[187]

Victim identification and protection in the UK

[edit]In the UK, human trafficking cases are processed by the same officials to simultaneously determine the refugee and trafficking victim statuses of a person. However, criteria for qualifying as a refugee and a trafficking victim differ and they have different needs for staying in a country. A person may need assistance as a trafficking victim but their circumstances may not necessarily meet the threshold for asylum. In this case, not being granted refugee status affects their status as a trafficked victim and thus their ability to receive help. Reviews of the statistics from the National Referral Mechanism (NRM), a tool created by the Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings (CoE Convention) to help states effectively identify and care for trafficking victims, found that positive decisions for non-European Union citizens were much lower than that of EU and UK citizens. According to data on the NRM decisions from April 2009 to April 2011, an average of 82.8% of UK and EU citizens were conclusively accepted as victims while an average of only 45.9% of non-EU citizens were granted the same status.[191] High refusal rates of non-EU people point to possible stereotypes and biases about regions and countries of origin which may hinder anti-trafficking efforts, since the asylum system is linked to the trafficking victim protection system.

Laura Agustin has suggested that, in some cases, "anti-traffickers" ascribe victim status to immigrants who have made conscious and rational decisions to cross the borders knowing they will be selling sex and who do not consider themselves to be victims.[192] There have been instances in which the alleged victims of trafficking have actually refused to be rescued[193] or run away from the anti-trafficking shelters.[194][195]

In a 2013 lawsuit,[196] the Court of Appeal gave guidance to prosecuting authorities on the prosecution of victims of human trafficking, and held that the convictions of three Vietnamese children and one Ugandan woman ought to be quashed as the proceedings amounted to an abuse of the court's process.[197] The case was reported by the BBC[198] and one of the victims was interviewed by Channel 4.[199]

In 2021, the European Court of Human Rights ordered the British government to compensate two victims of child trafficking for their later arrest and conviction of drug crimes.[200]

Law enforcement and the use of raids

[edit]In the U.S., services and protections for trafficked victims are related to cooperation with law enforcement. Legal procedures that involve prosecution and specifically, raids, are thus the most common anti-trafficking measures. Raids are conducted by law enforcement and by private actors and many organizations (sometimes in cooperation with law enforcement). Law enforcement perceive some benefits from raids, including the ability to locate and identify witnesses for legal processes, to dismantle "criminal networks", and to rescue victims from abuse.[98]

The problems against anti-trafficking raids are related to the problem of the trafficking concept itself, as raids' purpose of fighting sex trafficking may be conflated with fighting prostitution. The Trafficking Victims Protection Re-authorization Act of 2005 (TVPRA) gives state and local law enforcement funding to prosecute customers of commercial sex, therefore some law enforcement agencies make no distinction between prostitution and sex trafficking. One study interviewed women who have experienced law enforcement operations as sex workers and found that during these raids meant to combat human trafficking, none of the women were ever identified as trafficking victims, and only one woman was asked whether she was coerced into sex work. The conflation of trafficking with prostitution, then, does not serve to adequately identify trafficking and help the victims. Raids are also problematic in that the women involved were most likely unclear about who was conducting the raid, what the purpose of the raid was, and what the outcomes of the raid would be.[98][201] Another study found that the majority of women "rescued" in anti-trafficking raids, both voluntary and coerced sex workers, eventually returned to sex work but had amassed huge amounts of debt for legal fees and other costs while they were in detention after the raid and were, overall, in a worse situation than before the raid.[202]

Law enforcement personnel agree that raids can intimidate trafficked persons and render subsequent law enforcement actions unsuccessful. Social workers and attorneys involved in anti-sex trafficking have negative opinions about raids. Service providers report a lack of uniform procedure for identifying trafficking victims after raids. The 26 interviewed service providers stated that local police never referred trafficked persons to them after raids. Law enforcement also often use interrogation methods that intimidate rather than assist potential trafficking victims. Additionally, sex workers sometimes face violence from the police during raids and arrests and in rehabilitation centers.[98]

As raids occur to brothels that may house sex workers as well as sex trafficked victims, raids affect sex workers in general. As clients avoid brothel areas that are raided but do not stop paying for sex, voluntary sex workers will have to interact with customers underground. Underground interactions means that sex workers take greater risks, where as otherwise they would be cooperating with other sex workers and with sex worker organizations to report violence and protect each other. One example of this is with HIV prevention. Sex workers collectives monitor condom use, promote HIV testing, and cares for and monitor the health of HIV positive sex workers. Raids disrupt communal HIV care and prevention efforts, and if HIV positive sex workers are rescued and removed from their community, their treatments are disrupted, furthering the spread of AIDS.[203]

Scholars Aziza Ahmed and Meena Seshu suggest reforms in law enforcement procedures so that raids are last resort, not violent, and are transparent in its purposes and processes. Furthermore, they suggest that since any trafficking victims will probably be in contact with other sex workers first, working with sex workers may be an alternative to the raid and rescue model.[204]

"End Demand" programs

[edit]Critics argue that End Demand programs are ineffective in that prostitution is not reduced, "John schools" have little effect on deterrence and portray prostitutes negatively, and conflicts in interest arise between law enforcement and NGO service providers. A study found that Sweden's legal experiment (criminalizing clients of prostitution and providing services to prostitutes who want to exit the industry in order to combat trafficking) did not reduce the number of prostitutes, but instead increased exploitation of sex workers because of the higher risk nature of their work.[citation needed] The same study reported that johns' inclination to buy sex did not change as a result of john schools, and the programs targeted johns who are poor and colored immigrants. Some john schools also intimidate johns into not purchasing sex again by depicting prostitutes as drug addicts, HIV positive, violent, and dangerous, which further marginalizes sex workers. John schools require program fees, and police involvement in NGOs who provide these programs create conflicts of interest especially with money involved.[205][206]

However, according to a 2008 study, the Swedish approach of criminalizing demand has "led to an equality-centered approach that has drawn numerous positive reviews worldwide."[207]

Modern feminist perspectives

[edit]There are different feminist perspectives on sex trafficking. The third-wave feminist perspective of sex trafficking seeks to harmonize the dominant and liberal feminist views of sex trafficking. The dominant feminist view focuses on "sexualized domination", which includes issues of pornography, female sex labor in a patriarchal world, rape, and sexual harassment. Dominant feminism emphasizes sex trafficking as forced prostitution and considers the act exploitative. Liberal feminism sees all agents as capable of reason and choice. Liberal feminists support sex workers' rights, and argue that women who voluntarily chose sex work are autonomous. The liberal feminist perspective finds sex trafficking problematic where it overrides consent of individuals.[208][209][210]

Third-wave feminism harmonizes the thoughts that while individuals have rights, overarching inequalities hinder women's capabilities. Third-wave feminism also considers that women who are trafficked and face oppression do not all face the same kinds of oppression. For example, third-wave feminist proponent Shelley Cavalieri identifies oppression and privilege in the intersections of race, class, and gender. Women from low socioeconomic class, generally from the Global South, face inequalities that differ from those of other sex trafficking victims. Therefore, it advocates for catering to individual trafficking victim because sex trafficking is not monolithic, and therefore there is not a one-size-fits-all intervention. This also means allowing individual victims to tell their unique experiences rather than essentializing all trafficking experiences. Lastly, third-wave feminism promotes increasing women's agency both generally and individually, so that they have the opportunity to act on their own behalf.[208][209][210]

Third-wave feminist perspective of sex trafficking is loosely related to Amartya Sen's and Martha Nussbaum's visions of the human capabilities approach to development. It advocates for creating viable alternatives for sex trafficking victims. Nussbaum articulated four concepts to increase trafficking victims' capabilities: education for victims and their children, microcredit and increased employment options, labor unions for low-income women in general, and social groups that connect women to one another.[209]

The clash between the different feminist perspectives on trafficking and sex work was especially evident at the negotiations of the Palermo Protocol. One feminist group, led by the Global Alliance Against Traffic in Women, saw trafficking as the result of globalisation and restrictive labour migration policies, with force, fraud and coercion as its defining features. The other feminist group, led by the Coalition Against Trafficking in Women saw trafficking more narrowly as the result of men's demand for paid sex. Both groups tried to influence the definition of trafficking and other provisions in the Protocol. Eventually, both were only partially successful;[211][212] however, scholars have noted that this rift between feminist organisations led to the extremely weak and voluntary victim protection provisions of the Protocol.[213]

Social norms

[edit]According to modern feminists, women and girls are more prone to trafficking also because of social norms that marginalize their value and status in society. By this perspective females face considerable gender discrimination both at home and in school. Stereotypes that women belong at home in the private sphere and that women are less valuable because they do not and are not allowed to contribute to formal employment and monetary gains the same way men do further marginalize women's status relative to men. Some religious beliefs also lead people to believe that the birth of girls are a result of bad karma,[214][215] further cementing the belief that girls are not as valuable as boys. It is generally regarded by feminists that various social norms contribute to women's inferior position and lack of agency and knowledge, thus making them vulnerable to exploitation such as sex trafficking.[216]

See also

[edit]- Abusive power and control

- Adoption fraud

- Bride-buying

- Comfort woman

- Human trafficking by country

- Human trafficking in popular culture

- Human Trafficking (miniseries)

- List of organizations opposing human trafficking

- Kidnapping

- Migrant sex work

- Serious and Organised Crime Group

- Sexual jihad

- Sexual trafficking in Kosovo

- She Has a Name

- South East Asia Court of Women on HIV and Human Trafficking

- Transnational efforts to prevent human trafficking

- Western princess

- Wife selling

References

[edit]- ^ "UNODC on human trafficking and migrant smuggling". United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. 2011. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- ^ Zimmerman, Cathy; Kiss, Ligia (2017). "Human trafficking and exploitation: A global health concern". PLOS Medicine. 14 (11): e1002437. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002437.

- ^ Trafficking Institute website, Breaking Down Global Estimates of Human Trafficking: Human Trafficking Awareness Month 2022’, article by Emma Ecker dated January 12, 2022

- ^ US Government State Department website, About Human Trafficking, article dated 2022

- ^ a b "UNTC". un.org. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- ^ UK Government website, Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children, supplementing the UN Convention against Transnational Organized Crime, document dated November 15, 2000, page 6

- ^ "United Nations Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime And The Protocols Thereto" (PDF). Retrieved 21 January 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Bales, Kevin. Disposable People : New Slavery In The Global Economy / Kevin Bales. n.p.: Berkeley, Calif. : University of California Press, c2004., 2004.

- ^ "Top 10 Facts About Modern Slavery". Free the Slaves. Archived from the original on 21 June 2010. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

- ^ U.S. Department of State, Trafficking in Persons Report, 8th ed. (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of State, 2008), 7.

- ^ Smith, Heather M. "Sex trafficking: trends, challenges, and the limitations of international law." Human rights review 12.3 (2011): 271–286.

- ^ Special Action Programme to Combat Forced Labour (20 May 2014). "Profits and poverty: The economics of forced labour" (PDF). International Labour Organization. p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 October 2017. Retrieved 24 October 2016.

- ^ "21 million people are now victims of forced labour, ILO says". International Labour Organization. 1 June 2012. Retrieved 24 October 2016.

- ^ a b "Human Trafficking by the Numbers". Human Rights First. Archived from the original on 7 May 2019. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- ^ Louise Shelley (2010). Human Trafficking: A Global Perspective. Cambridge University Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-1-139-48977-5.

- ^ "The trafficking of children for sexual purposes: One of the worst manifestations of this crime". ecpat.org. 6 August 2018.

- ^ "HUMAN TRAFFICKING: A GLOBAL ENTERPRISE". freeforlifeintl.org. 31 July 2020. Archived from the original on 9 February 2023. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- ^ "Global report on trafficking in persons". unodc.org. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

- ^ "Global report on trafficking in persons". Unodc.org. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

- ^ WomanStats Maps, Woman Stats Project.

- ^ Trafficking In Persons Report June 2019 (PDF) (Report). U.S. State Department.

- ^ "The Worst Countries For Human Trafficking". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. 29 June 2018.

- ^ "Human trafficking, modern-day slavery". Miami Herald.

- ^ Department Of State. The Office of Electronic Information, Bureau of Public Affairs (10 June 2008). "Country Narratives -- Countries S through Z". 2001-2009.state.gov.

- ^ "Singapore vows 'strong' action on labor trafficking after first conviction". Reuters. 19 November 2019.

- ^ a b "Child Trafficking for Forced Marriage" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 July 2013.

- ^ "Slovakian 'slave' trafficked to Burnley for marriage". BBC News. 9 October 2013.

- ^ "MARRIAGE IN FORM, TRAFFICKING IN CONTENT: Non – consensual Bride Kidnapping in Contemporary Kyrgyzstan" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 April 2014. Retrieved 2 November 2016.

- ^ "Trafficking in organs, tissues and cells and trafficking in human beings for the purpose of the removal of organs" (PDF). United Nations. 2009. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ^ "Human trafficking for organs/tissue removal". Fightslaverynow.org. 30 May 2010. Retrieved 30 December 2012.

- ^ "Human trafficking for ova removal or surrogacy". Councilforresponsiblegenetics.org. 31 March 2004. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 30 December 2012.

- ^ Williams, Rachel (3 July 2008). "British-born teenagers being trafficked for sexual exploitation within UK, police say". The 8102998382. London. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- ^ Mother sold girl for sex, 7 May 2010, The Age.

- ^ "Kideny Trafficking in Nepal" (PDF). Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- ^ "The Facts About Children Trafficked For Use As Camel Jockeys". state.gov.

- ^ "Agents in the UEFA spotlight". Archived from the original on 30 April 2009. Retrieved 5 February 2007., UEFA, 29 September 2006. (archived from the original on 30 April 2009)

- ^ a b "Child Labour". www.ilo.org. 28 January 2024.

- ^ "LatAm – Brazil – Child Prostitution Crisis". Libertadlatina.org. Archived from the original on 3 June 2016. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- ^ McCarthy, Lauren A. (30 May 2016). "Transaction Costs: Prosecuting child trafficking for illegal adoption in Russia". Anti-Trafficking Review (6): 31–47. doi:10.14197/atr.20121663.

- ^ Okyere, Samuel (21 September 2017). "'Shock and awe': A critique of the Ghana-centric child trafficking discourse". Anti-Trafficking Review (9): 92–105. doi:10.14197/atr.20121797.

- ^ Olayiwola, Peter (26 September 2019). "'Killing the Tree by Cutting the Foliage Instead of Uprooting It?' Rethinking awareness campaigns as a response to trafficking in South-West Nigeria". Anti-Trafficking Review (13): 50–65. doi:10.14197/atr.201219134. ISSN 2287-0113.

- ^ "The Age: China sets up website to recover trafficked children: report". Melbourne: News.theage.com.au. 28 October 2009. Archived from the original on 27 April 2011. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- ^ The Two Faces of Inter-country Adoption: The Significance of the Indian Adoption Scandals at the Wayback Machine (archived 26 March 2009), Seton Hall Law Review, 35:403–493, 2005. (archived from the original on 26 March 2009)

- ^ Child Laundering: How the Inter-country Adoption System Legitimizes and Incentivizes the Practices of Buying, Trafficking, Kidnapping, and Stealing Children by David M. Smolin, bepress Legal Series, Working Paper 749, 29 August 2005.

- ^ "Convention on the Rights of the Child". ohchr.org.

- ^ "DIRECTIVE 2011/92/EU OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL". Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- ^ "Convention of 29 May 1993 on Protection of Children and Co-operation in Respect of Intercountry Adoption". hcch.net. (full text)

- ^ "Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child". ohchr.org. Archived from the original on 2 May 2013. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- ^ a b "Forced labour, human trafficking and slavery". ilo.org. 28 January 2024.

- ^ Siddharth Kara (2009). Sex Trafficking: Inside the Business of Modern Slavery. Columbia University Press.

- ^ a b "Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act of 2000". State.gov. Archived from the original on 12 March 2009. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- ^ "Colla UK_Sarah_final" (PDF). Gaatw.net. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2011. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- ^ Chapman-Schmidt, Ben (29 April 2019). "'Sex Trafficking' as Epistemic Violence". Anti-Trafficking Review (12): 172–187. doi:10.14197/atr.2012191211. hdl:1885/288046. ISSN 2287-0113.

- ^ Migration Information Programme. Trafficking and prostitution: the growing exploitation of migrant women from central and eastern Europe. Geneva, International Organization for Migration, 1995.

- ^ Chauzy JP. Kyrgyz Republic: trafficking. Geneva, International Organization for Migration, 20 January 2001 (Press briefing notes)

- ^ "BBC – Ethics – Forced Marriages: Introduction". bbc.co.uk.

- ^ "Forced and servile marriage in the context of human trafficking". aic.gov.au.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Hackney, Laura K. (30 April 2015). "Re-evaluating Palermo: The case of Burmese women as Chinese brides". Anti-Trafficking Review (4). doi:10.14197/atr.20121546.

- ^ "A Study on Forced Marriage between Cambodia and China" (PDF). United Nations Action for Cooperation against Trafficking in Persons (UN-ACT). 2016.

- ^ a b Gallagher, Anne T. (30 May 2016). "Editorial: The Problems and Prospects of Trafficking Prosecutions: Ending impunity and securing justice". Anti-Trafficking Review (6): 1–11. doi:10.14197/atr.20121661.

- ^ a b "Trafficking for Forced Labour". ungift.org. Archived from the original on 4 April 2013.

- ^ "Difference between Smuggling and Trafficking". Anti-trafficking.net. Archived from the original on 21 February 2013. Retrieved 30 December 2012.

- ^ International Law of Migrant Smuggling, 2014, 9-10

- ^ Palmer, Wayne; Missbach, Antje (6 September 2017). "Trafficking within migrant smuggling operations: Are underage transporters 'victims' or 'perpetrators'?". Asian and Pacific Migration Journal. 26 (3): 287–307. doi:10.1177/0117196817726627. S2CID 158909571.

- ^ a b "Labor trafficking fact sheet" (PDF). National Human Trafficking Resource Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 May 2010.

- ^ "A global alliance against forced labour", ILO, 11 May 2005.

- ^ McCarthy, Ryan (18 December 2010). "13 Products Most Likely to Be Made By Child or Forced Labor". Huffington Post. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- ^ "Trafficking for organ trade". ungift.org. Archived from the original on 9 November 2014.

- ^ "Types of human trafficking". interpol.int.

- ^ a b c Berger, Stephanie M (2012). "No End In Sight: Why The "End Demand" Movement Is The Wrong Focus For Efforts To Eliminate Human Trafficking". Harvard Journal of Law & Gender. 35 (2): 523–570.

- ^ Weitzer, Ronald. "The social construction of sex trafficking: ideology and institutionalization of a moral crusade." Politics & Society 35.3 (2007): 447–475.

- ^ Chuang, Janie (2006). "Beyond a snapshot: Preventing human trafficking in the global economy". Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies. 13 (1): 137–163. doi:10.1353/gls.2006.0002.

- ^ Scheper-Hughes, Nancy. "Organs Without Borders". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 22 January 2014.

- ^ Fry-Revere, Sigrid (2014). The Kidney Sellers:A Journey of Discovery in Iran. Carolina Academic Press.

- ^ Domestic Minor Sex Trafficking: Hearings on H.R. 5575, Before the Subcommittee on Crime, Terrorism, and Homeland Security, 111th Cong. 145 (2010) (statement of Ernie Allen, president and CEO, National Center for Missing & Exploited Children).

- ^ Shared Hope International, Demand: A Comparative Examination of Sex Tourism and Trafficking in Jamaica, Japan, the Netherlands, and the United States, n.d., 5.

- ^ Kim-Kwang Raymond Choo, "Online child grooming: A literature review on the misuse of social networking sites for grooming children for sexual offences", Australian Institute of Criminology Research and Public Policy Series 103, 2009, ii–xiv.

- ^ Musto, J. L.; boyd, d. (1 September 2014). "The Trafficking-Technology Nexus". Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society. 21 (3): 461–483. doi:10.1093/sp/jxu018. ISSN 1072-4745. S2CID 145112041.

- ^ "Michelle Goldberg, "The Super Bowl of Sex Trafficking", Newsweek, January 30, 2011". Newsweek.

- ^ Latonero, Mark. "Human Trafficking Online: The Role of Social Networking Sites and Online Classifieds." USC Annenberg Center on Communication Leadership & Policy. Available at SSRN 2045851 (2011).

- ^ Anna Merlan, "Just in Time for February, the Myth of Sex Trafficking and the Super Bowl Returns" Archived 2 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Village Voice Blogs, 30 January 2014.

- ^ Ham, Julie (2011). "What's the Cost of a Rumour?" (PDF). Global Alliance Against Traffic in Women.

- ^ Martin, Lauren; Hill, Annie (26 September 2019). "Debunking the Myth of 'Super Bowl Sex Trafficking': Media hype or evidenced-based coverage". Anti-Trafficking Review (13): 13–29. doi:10.14197/atr.201219132. ISSN 2287-0113.

- ^ a b Burkhalter, Holly (2012). "Sex Trafficking, Law Enforcement and Perpetrator Accountability". Anti Trafficking Review. 1: 122–133.

- ^ 2016 Trafficking in Persons Report, U.S. Department of State