Phoenician alphabet

| Phoenician alphabet | |

|---|---|

| |

| Script type | |

Time period | Began 1050 BCE, and gradually died out during the Hellenistic period as its evolved forms replaced it |

| Direction | Right-to-left script |

| Languages | Phoenician |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | Cuneiform script

|

Child systems | Paleo-Hebrew alphabet Aramaic alphabet Greek alphabet Many hypothesized others |

Sister systems | South Arabian alphabet |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Phnx (115), Phoenician |

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Phoenician |

| U+10900–U+1091F | |

The Phoenician alphabet, called by convention the Proto-Canaanite alphabet for inscriptions older than around 1200 BCE, was a non-pictographic consonantal alphabet, or abjad.[1] It was used for the writing of Phoenician, a Northern Semitic language, used by the civilization of Phoenicia. It is classified as an abjad because it records only consonantal sounds (matres lectionis were used for some vowels in certain late varieties).

Phoenician became one of the most widely used writing systems, spread by Phoenician merchants across the Mediterranean world, where it evolved and was assimilated by many other cultures. The Aramaic alphabet, a modified form of Phoenician, was the ancestor of modern Arabic script, while Hebrew script is a stylistic variant of the Aramaic script. The Greek alphabet (and by extension its descendants such as the Latin, the Cyrillic and the Coptic), was a direct successor of Phoenician, though certain letter values were changed to represent vowels.

As the letters were originally incised with a stylus, most of the shapes are angular and straight, although more cursive versions are increasingly attested in later times, culminating in the Neo-Punic alphabet of Roman-era North Africa. Phoenician was usually written from right to left, although there are some texts written in boustrophedon.

In 2005, UNESCO registered the Phoenician alphabet into the Memory of the World Programme as a heritage of Lebanon.[2]

History

When the Phoenician alphabet was first uncovered in the 19th century, its origin was unknown. Scholars at first believed that the script was a direct variation of Egyptian hieroglyphs.[3] This idea was especially popular due to the recent decipherment of hieroglyphs. However, scholars could not find any link between the two writing systems. Certain scholars[who?] hypothesized ties with Hieratic, Cuneiform, or even an independent creation, perhaps inspired by some other writing system. The theories of independent creation ranged from the idea of a single man conceiving it, to the Hyksos people forming it from corrupt Egyptian.[4]

Parent scripts

The Proto-Sinaitic script was in use from ca. 1850 BCE in the Sinai by Canaanite speakers. There are sporadic attestations of very short Proto-Sinaitic inscriptions in Canaan in the late Middle and Late Bronze Age, but the script was not widely used until the rise of new Semitic kingdoms in the 13th and 12th centuries BCE. The oldest known inscription that goes by the name of Phoenician is the Ahiram epitaph, engraved on the sarcophagus of King Ahiram from c. 1200 BCE.[5]

It has become conventional to refer to the script as "Proto-Canaanite" until the mid-11th century, when it is first attested on inscribed bronze arrowheads, and as "Phoenician" only after 1050 BCE.[6]

Spread of the alphabet and its social effects

The Phoenician adaptation of the alphabet was extremely successful, and variants were adapted around the Mediterranean from about the 9th century BCE, notably giving rise to the Greek, Old Italic, Anatolian and Paleohispanic scripts. The alphabet's success was due in part to its phonetic nature; Phoenician was the first widely used script in which one sound was represented by one symbol. This simple system contrasted with the other scripts in use at the time, such as Cuneiform and Egyptian hieroglyphs, which employed many complex characters and were difficult to learn.[7]

Another reason of its success was the maritime trading culture of Phoenician merchants, which spread the use of the alphabet into parts of North Africa and Europe.[8] Phoenician inscriptions have been found in archaeological sites at a number of former Phoenician cities and colonies around the Mediterranean, such as Byblos (in present-day Lebanon) and Carthage in North Africa. Later finds indicate earlier use in Egypt.[9]

Phoenician had long-term effects on the social structures of the civilizations which came in contact with it. As mentioned above, the script was the first widespread phonetic script. Its simplicity not only allowed it to be used in multiple languages, but it also allowed the common people to learn how to write. This upset the long-standing status of writing systems only being learned and employed by members of the royal and religious hierarchies of society, who used writing as an instrument of power to control access to information by the larger population.[10] The appearance of Phoenician disintegrated many of these class divisions, although many Middle Eastern kingdoms such as Assyria, Babylonia and Adiabene would continue to use cuneiform for legal and liturgical matters well into the Common Era.

Letter names

Phoenician uses a system of acrophony to name letters. The names of the letters are essentially the same as in its parental scripts, which are in turn derived from the word values of the original hieroglyph for each letter.[11] The original word was translated from Egyptian into its equivalent form in the Semitic language, and then the initial sound of the translated word become the letter's value.[12]

However, according to a theory by Theodor Nöldeke from 1904, some of the letter names were changed in Phoenician from the Proto-Canaanite script.[dubious – discuss] This includes:

- gaml "throwing stick" to gimel "camel"

- digg "fish" to dalet "door"

- hll "jubilation" to he "window"

- ziqq "manacle" to zayin "weapon"

- naḥš "snake" to nun "fish"

- piʾt "corner" to pey "mouth"

- šimš "sun" to šin "tooth"

Other researchers such as Prof. Yigael Yadin went to great lengths to prove that they actually were tools of war, similar to the original drawings.[13] Prof. Aron Demsky from Bar Ilan University showed that there were sequences of letters with close meanings, proving the correct reading of the drawings.[14] In later research it was postulated that the alphabet is actually two complete lists, the first dealing with land agriculture and activity, and the second dealing with water, sea and fishing.[15][16]

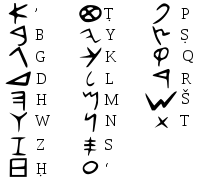

The Phoenician letterforms shown here are idealized—actual Phoenician writing was cruder and more variable in appearance. There were also significant variations in Phoenician letterforms by era and region.

When alphabetic writing began in Greece, the letterforms used were similar but not identical to the Phoenician ones and vowels were added, because the Phoenician Alphabet did not contain any vowels. There were also distinct variations of the writing system in different parts of Greece, primarily in how the Phoenician characters which did not have an exact match to Greek sounds were employed. The Athenian alphabet evolved into the standard Greek alphabet, and another into the Latin alphabet, which accounts for many of the differences between the two. Occasionally, Phoenician used a short stroke or dot symbol as a word separator.[17]

The chart shows the graphical evolution of Phoenician letterforms into other alphabets. The sound values often changed significantly, both during the initial creation of new alphabets, and due to pronunciation changes of languages using the alphabets over time.

| Letter | Uni. | Name | Meaning | Ph. | Corresponding letter in | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| He. | Sy. | Ar. | Greek | Latin | Cyrillic | Armenian | ||||||

| 𐤀 | alf | ox | ʾ [ʔ] | א | ܐ | ﺍ | Αα | Aa | Аа | Աա | ||

| 𐤁 | bet | house | b [b] | ב | ܒ | ﺏ | Ββ | Bb | Бб, Вв | Բբ | ||

| 𐤂 | gaml | camel | g [ɡ] | ג | ܓ | ﺝ | Γγ | Cc, Gg | Гг, Ґґ | Գգ | ||

| 𐤃 | delt | door | d [d] | ד | ܕ | د | Δδ | Dd | Дд | Դդ | ||

| 𐤄 | he | window | h [h] | ה | ܗ | ھ | Εε | Ee | Ее, Єє, Ээ | Եե, Էէ | ||

| 𐤅 | wau | hook | w [w] | ו | ܘ | ﻭ | (Ϝϝ), Υυ | Ff, Uu, Vv, Yy, Ww | (Ѵѵ), Уу, Ўў | Վվ, Ււ | ||

| 𐤆 | zen | weapon | z [z] | ז | ܙ | ﺯ, ذ | Ζζ | Zz | Жж, Зз | Զզ | ||

| 𐤇 | het | wall | ḥ [ħ] | ח | ܚ | ح, خ | Ηη | Hh | Ии, Йй | Հհ | ||

| 𐤈 | tet | wheel | ṭ [tˤ] | ט | ܛ | ط | Θθ | — | (Ѳѳ) | Թթ | ||

| 𐤉 | yod | hand | y [j] | י | ܝ | ي | Ιι | Ii, Jj | Іі, Її, Јј | Յյ, Իի | ||

| 𐤊 | kaf | palm (of a hand) | k [k] | כך | ܟ | ﻙ | Κκ | Kk | Кк | Կկ | ||

| 𐤋 | lamda | goad | l [l] | ל | ܠ | ﻝ | Λλ | Ll | Лл | Լլ | ||

| 𐤌 | mem | water | m [m] | מם | ܡ | ﻡ | Μμ | Mm | Мм | Մմ | ||

| 𐤍 | nun | serpent, later whale | n [n] | נן | ܢ | ﻥ | Νν | Nn | Нн | Նն | ||

| 𐤎 | semka | fish | s [s] | ס | ܣ, ܤ | س | Ξξ, poss. Χχ | poss. Xx | (Ѯѯ), poss. Хх | Խխ | ||

| 𐤏 | eyn | eye | ʿ [ʕ] | ע | ܥ | ع, غ | Οο, Ωω | Oo | Оо | Ոո, Օօ | ||

| 𐤐 | pey | mouth | p [p] | פף | ܦ | ف | Ππ | Pp | Пп | Պպ, Փփ | ||

| 𐤑 | sade | hunt | ṣ [sˤ] | צץ | ܨ | ص, ض, ظ | (Ϻϻ) | — | Цц, Чч, Џџ | Չչ, Ճճ, Ցց, Ծծ, Ձձ, Ջջ | ||

| 𐤒 | qof | needle head | q [q] | ק | ܩ | ﻕ | (Ϙϙ), poss. Φφ, Ψψ | (Ҁҁ) | Քք | |||

| 𐤓 | rosh | head | r [r] | ר | ܪ | ﺭ | Ρρ | Rr | Рр | Րր, Ռռ | ||

| 𐤔 | shin | tooth | š [ʃ] | ש | ܫ | ش | Σσς | Ss | Сс, Шш, Щщ | Սս, Շշ | ||

| 𐤕 | tau | mark | t [t] | ת | ܬ | ت, ث | Ττ | Tt | Тт | Տտ | ||

| Labial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Pharyngeal | Glottal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plain | Emphatic | ||||||||

| Nasal | m | n | |||||||

| Stop | Voiceless | p | t | tˤ | k | q | ʔ | ||

| Voiced | b | d | ɡ | ||||||

| Fricative | Voiceless | s | sˤ | ʃ | ħ | h | |||

| Voiced | z | ʕ | |||||||

| Trill | r | ||||||||

| Approximant | l | j | w | ||||||

Numerals

The Phoenician numeral system consisted of separate symbols for 1, 10, 20, and 100. The sign for 1 was a simple vertical stroke (𐤖). Other numbers up to 9 were formed by adding the appropriate number of such strokes, arranged in groups of three. The symbol for 10 was a horizontal line or tack (𐤗). The sign for 20 (𐤘) could come in different glyph variants, one of them being a combination of two 10-tacks, approximately Z-shaped. Larger multiples of ten were formed by grouping the appropriate number of 20s and 10s. There existed several glyph variants for 100 (𐤙). The 100 symbol could be combined with a preceding numeral in a multiplicatory way, e.g. the combination of "4" and "100" yielded 400.[18]

Unicode

The Phoenician alphabet was added to the Unicode Standard in July 2006 with the release of version 5.0. An alternative proposal to handle it as a font variation of Hebrew was turned down. (See PDF summary.)

The Unicode block for Phoenician is U+10900–U+1091F. It is intended for the representation of text in Palaeo-Hebrew, Archaic Phoenician, Phoenician, Early Aramaic, Late Phoenician cursive, Phoenician papyri, Siloam Hebrew, Hebrew seals, Ammonite, Moabite, and Punic.

The letters are encoded U+10900 𐤀 aleph through to U+10915 𐤕 taw, U+10916 𐤖, U+10917 𐤗, U+10918 𐤘 and U+10919 𐤙 encode the numerals 1, 10, 20 and 100 respectively and U+1091F 𐤟 is the word separator.

| Phoenician[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+1090x | 𐤀 | 𐤁 | 𐤂 | 𐤃 | 𐤄 | 𐤅 | 𐤆 | 𐤇 | 𐤈 | 𐤉 | 𐤊 | 𐤋 | 𐤌 | 𐤍 | 𐤎 | 𐤏 |

| U+1091x | 𐤐 | 𐤑 | 𐤒 | 𐤓 | 𐤔 | 𐤕 | 𐤖 | 𐤗 | 𐤘 | 𐤙 | 𐤚 | 𐤛 | 𐤟 | |||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

Derived alphabets

Middle Eastern descendants

The Paleo-Hebrew alphabet, used to write early Hebrew, was a regional offshoot of Phoenician; it is nearly identical to the Phoenician one. The Samaritan alphabet, used by the Samaritans, is a direct descendant of the Paleo-Hebrew alphabet.

The Aramaic alphabet, used to write Aramaic, is another descendant of Phoenician. Aramaic being the lingua franca of the Middle East, it was widely adopted. It later split off (due to power/political borders) into a number of related alphabets, including the Hebrew alphabet, the Syriac alphabet, and the Nabataean alphabet, which in its cursive form became an ancestor of Arabic, currently used in Arabic-speaking countries from North Africa through the Levant to Iraq and the Gulf region, as well as in Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan and other countries for other languages.

The Coptic alphabet, still used in Egypt for writing the Christian liturgical language Coptic (descended from Ancient Egyptian) is mostly based on the Greek alphabet, but with a few additional letters for sounds not in Greek at the time. Those additional letters are based on Demotic script.

Derived European scripts

According to Herodotus,[19] Phoenician prince Cadmus was accredited with the introduction of the Phoenician alphabet—phoinikeia grammata, "Phoenician letters"—to the Greeks, who adapted it to form their Greek alphabet, which was later introduced to the rest of Europe. Herodotus, who gives this account, estimates that Cadmus lived sixteen hundred years before his time, or around 2000 BC.[20] However, Herodotus' writings are not used as a standard source by contemporary historians. The Greek alphabet is derived from the Phoenician alphabet.[21] The phonology of Greek being different from that of Phoenician, the Greeks modified the Phoenician script to better suit their language. It was possibly more important in Greek to write out vowel sounds: Phoenician being a Semitic language, words were based on consonantal roots that permitted extensive removal of vowels without loss of meaning, a feature absent in the Indo-European Greek. (Or perhaps, the Phoenicians were simply following the lead of the Egyptians, who never wrote vowels. After all, Akkadian cuneiform, which wrote a related Semitic language, always indicated vowels.) In any case, the Greeks adapted the signs of the Phoenician consonants not present in Greek; each such name was shorn of its leading sound, and the sign took the value of the now leading vowel. For example, ʾāleph, which designated a glottal stop in Phoenician, was re-purposed to represent the vowel /a/; he became /e/, ḥet became /eː/ (a long vowel), `ayin became /o/ (because the pharyngeality altered the following vowel), while the two semi-consonants wau and yod became the corresponding high vowels, /u/ and /i/. (Some dialects of Greek, which did possess /h/ and /w/, continued to use the Phoenician letters for those consonants as well.)

The Cyrillic script was derived from the Greek alphabet. Some Cyrillic letters (generally for sounds not in Mediaeval Greek) are based on Glagolitic forms, which in turn were influenced by the Hebrew or even Coptic alphabets.[citation needed]

The Latin alphabet was derived from Old Italic (originally a form of the Greek alphabet), used for Etruscan and other languages. The origin of the Runic alphabet is disputed, and the main theories are that it evolved either from the Latin alphabet itself, some early Old Italic alphabet via the Alpine scripts or the Greek alphabet. Despite this debate, the Runic alphabet is clearly derived from one or more scripts which ultimately trace their roots back to the Phoenician alphabet.[21][22]

Influence in Central Asia

The Sogdian alphabet, a descendant of Phoenician via Syriac, is an ancestor of the Old Uyghur, which in turn is an ancestor of the Mongolian and Manchu alphabets, the former of which is still in use and the latter of which survives as the Xibe script.

Influence in South-West Asia

Arabic script, a descendant of Phoenician via Aramaic is used in Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and other countries to write Persian, Urdu, and other languages.

Influence in South and South-East Asia

Most historians believe that the Brahmi script and the subsequent Indic alphabets are derived from the Aramaic script as well, which would make Phoenician the ancestor of most writing systems in use today.[23][full citation needed]

Surviving examples

- Ahiram

- Bodashtart

- Çineköy inscription

- Cippi of Melqart

- Eshmunazar

- Karatepe

- Kilamuwa Stela

- Nora Stone

- Pyrgi Tablets

- Temple of Eshmun

See also

- Arabic alphabet

- Aramaic alphabet

- Armenian alphabet

- Avestan alphabet

- Hebrew alphabet

- Greek alphabet

- Old Turkic script

- Paleo-Hebrew alphabet

- Tanakh at Qumran

- Tifinagh

- Ugaritic alphabet

Notes

- ^ Fischer, Steven Roger (2004). A history of writing. Reaktion Books. p. 90.

- ^ Memory of the World, official site

- ^ Jensen (1969) p. 256.

- ^ Jensen (1969) p. 256-258.

- ^ Coulmas (1989) p. 141.

- ^ Markoe (2000) p. 111

- ^ Hock and Joseph (1996) p. 85.

- ^ Daniels (1996) p. 94-95.

- ^ Semitic script dated to 1800 BCE

- ^ Fischer (2003) p. 68-69.

- ^ Jensen (1969) p. 262.

- ^ Jensen (1969) p. 262-263.

- ^ Yigael Yadin, The Art of Warfare in Biblical Lands. McGraw-Hill, 1963. The Samech - a quick war ladder, later to become the '$' dollar sign drawing the three internal lines quickly. The 'Z' shaped Zayin - an ancient boomerang used for hunting. The 'H' shaped Het - mammoth tuffs.

- ^ Yod=arm or handle, Kaf=Hand, paw or shovel, Mem=water, Nun=fish

- ^ The first half beginning with Alef - an ox, and ending with Lamed - a whip. The second list begins with Mem - water, and continues with Nun - fish, Samek - fish bones, Ayin - a water spring, Peh - the mouth of a well, Tsadi - to fish, Kof, Resh and Shin are the hook hole, hook head and hook teeth, known to exist from prehistoric times, and the Tav is the mark used to count the fish caught.

- ^ http://www.mentalfloss.com/article/29011/why-are-letters-abc-order

- ^ http://unicode.org/charts/PDF/U10900.pdf

- ^ Phoenician numerals in Unicode, Systèmes numéraux

- ^ Herodotus, Histories, Book V, 58.

- ^ Herodotus. Histories, Book II, 2.145

- ^ a b Humphrey, John William (2006). Ancient technology. Greenwood guides to historic events of the ancient world (illustrated ed.). Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 219. ISBN 9780313327636. Retrieved 2009-10-18.

- ^ Spurkland, Terje (2005): Norwegian Runes and Runic Inscriptions, translated by Betsy van der Hoek, Boydell Press, Woodbridge, pp. 3-4

- ^ Richard Salomon, "Brahmi and Kharoshthi", in The World's Writing Systems

References

- Jean-Pierre Thiollet, Je m'appelle Byblos, H & D, Paris, 2005. ISBN 2-914266-04-9

- Maria Eugenia Aubet, The Phoenicians and the West Second Edition, Cambridge University Press, London, 2001.

- Daniels, Peter T., et al. eds. The World's Writing Systems Oxford. (1996).

- Jensen, Hans, Sign, Symbol, and Script, G.P. Putman's Sons, New York, 1969.

- Coulmas, Florian, Writing Systems of the World, Blackwell Publishers Ltd, Oxford, 1989.

- Hock, Hans H. and Joseph, Brian D., Language History, Language Change, and Language Relationship, Mouton de Gruyter, New York, 1996.

- Fischer, Steven R., A History of Writing, Reaktion Books, 2003.

- Markoe, Glenn E., Phoenicians. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-22613-5 (2000) (hardback)

- Ancient Hebrew and Aramaic on Coins, reading and transliterating Proto-Hebrew, online edition. (Judaea Coin Archive)

External links

- Ancient Scripts.com (Phoenician)

- Omniglot.com (Phoenician alphabet)

- official Unicode standards document for Phoenician (PDF file)

- [1] Free-Libre GPL2 Licensed Unicode Phoenician Font

- GNU FreeFont Unicode font family with Phoenician range in its serif face.