Qajar dynasty: Difference between revisions

LouisAragon (talk | contribs) →War with Russia: fixes |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

|p3 = Durrani Empire |

|p3 = Durrani Empire |

||

|flag_p3 = Flag of Herat until 1842.svg |

|flag_p3 = Flag of Herat until 1842.svg |

||

|s1 = Pahlavi |

|s1 = Pahlavi State of Iran |

||

|flag_s1 = State Flag of Iran (1964).svg |

|flag_s1 = State Flag of Iran (1964).svg |

||

|s2 = Russian Empire |

|s2 = Russian Empire |

||

Revision as of 02:08, 8 June 2015

Sublime State of Persia دولت علیّه ایران Dowlat-e Elliye ye Irān | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1785–1925 | |||||||||||||||

| Anthem: Salâm-e Shâh (Royal salute) | |||||||||||||||

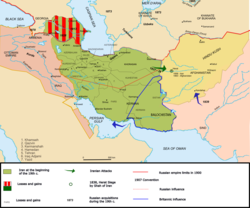

Map of Iran under the Qajar dynasty in the 19th century. | |||||||||||||||

| Capital | Tehran | ||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Persian (court literature, administrative, cultural, official),[1][2] Azeri (Turkish) (court language & mother tongue)[3] | ||||||||||||||

| Government | Absolute monarchy (1785–1906) Constitutional monarchy (1906–1925) | ||||||||||||||

| Shah, Mirza | |||||||||||||||

• 1794–1797 | Mohammad Khan Qajar (first) | ||||||||||||||

• 1909–1925 | Ahmad Shah Qajar (last) | ||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||||||||

• 1906 | Mirza Nasrullah Khan (first) | ||||||||||||||

• 1923–1925 | Reza Pahlavi (last) | ||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||

• Qajar dynasty begins | 1785 | ||||||||||||||

| 1813 | |||||||||||||||

| 1828 | |||||||||||||||

| 1857 | |||||||||||||||

| 1881 | |||||||||||||||

| 1906 | |||||||||||||||

• Pahlavi dynasty begins | 1925 | ||||||||||||||

| Currency | qiran[4] | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Today part of | Countries today | ||||||||||||||

| History of Iran |

|---|

|

|

Timeline |

The Qajar dynasty (; Template:Lang-fa Dudmân e Qâjâr; also romanised as Ghajar, Kadjar, Qachar etc.; Template:Lang-az) was a Persianized[5] native Iranian royal family of Turkic origin,[6][7][8][9][10] which ruled Persia (Iran) from 1785 to 1925.[11][12] The Qajar family took full control of Iran in 1794, deposing Lotf 'Ali Khan, the last of the Zand dynasty, and re-asserted Persian sovereignty over large parts of the Caucasus and Central Asia. In 1796, Mohammad Khan Qajar seized Mashhad with ease,[13] putting an end to the Afsharid dynasty, and Mohammad Khan was formally crowned as shah after his punitive campaign against Persia's Georgian subjects.[14] In the North Caucasus, South Caucasus, and Central Asia the Qajar dynasty eventually permanently lost many of Iran's controlled areas to the Russians in the course of the 19th century.[15]

Origins

The Qajar rulers were members of the Karagöz or "Black-Eye" sept of the Qajars, who themselves were members of the Karapapak or "Black Hats" lineage of the Oghuz Turks.[6][7][8][9] Qajars first settled during the Mongol period in the vicinity of Azerbaijan and were among the seven Qizilbash tribes that supported the Safavids.[16] The Safavids "left Arran (present-day Republic of Azerbaijan) to local Turkic khans",[17] and, "in 1554 Ganja was governed by Shahverdi Soltan Ziyadoglu Qajar, whose family came to govern Karabakh in southern Arran".[18]

Qajars filled a number of diplomatic missions and governorships in the 16–17th centuries for the Safavids. The Qajars were resettled by Shah Abbas I throughout Iran. The great number of them also settled in Astarabad (present-day Gorgan, Iran) near the south-eastern corner of the Caspian Sea,[7] and it would be this branch of Qajars that would rise to power. The immediate ancestor of the Qajar dynasty, Shah Qoli Khan of the Quvanlu of Ganja, married into the Quvanlu Qajars of Astarabad. His son, Fath Ali Khan (born c. 1685–1693) was a renowned military commander during the rule of the Safavid shahs Sultan Husayn and Tahmasp II. He was killed on the orders of Shah Nader Shah in 1726. Fath Ali Khan's son Mohammad Hasan Khan Qajar (1722–1758) was the father of Mohammad Khan Qajar and Hossein Qoli Khan (Jahansouz Shah), father of "Baba Khan," the future Fath-Ali Shah Qajar. Mohammad Hasan Khan was killed on the orders of Karim Khan of the Zand dynasty.

Within 126 years between the demise of the Safavid state and the rise of Naser al-Din Shah Qajar, the Qajars had evolved from a shepherd-warrior tribe with strongholds in northern Persia into a Persian dynasty with all the trappings of a Perso-Islamic monarchy.[5]

Rise to power

"Like virtually every dynasty that ruled Persia since the 11th century, the Qajars came to power with the backing of Turkic tribal forces, while using educated Persians in their bureaucracy".[19] In 1779 following the death of Karim Khan of the Zand dynasty, Mohammad Khan Qajar, the leader of the Qajars, set out to reunify Iran. Mohammad Khan was known as one of the cruelest kings, even by the 18th century Iranian standards.[7] In his quest for power, he razed cities, massacred entire populations, and blinded some 20,000 men in the city of Kerman because the local populace had chosen to defend the city against his siege.[7]

The Qajar armies at that time were mostly composed of Turkomans and Georgian slaves.[20] By 1794, Mohammad Khan had eliminated all his rivals, including Lotf Ali Khan, the last of the Zand dynasty. He reestablished Persian control over the territories in the entire Caucasus. Agha Mohammad established his capital at Tehran, a village near the ruins of the ancient city of Rayy. In 1796 he was formally crowned as shah. In 1797, Mohammad Khan Qajar was assassinated in Shusha, the capital of Karabakh Khanate, and was succeeded by his nephew, Fath-Ali Shah Qajar.

Wars with Russia and irrevocable loss of territories

In 1803, under Fath Ali Shah, Qajars set out to fight against the Russian Empire, in what was known as Russo-Persian War of 1804–1813, due to concerns about the Russian expansion into the Caucasus, which was an Iranian domain, although some of the Khanates of the Caucasus were considered quasi-independent or semi-independent by the time of Russian expansion in the 19th century.[21] This period marked the first major economic and military encroachments on Iranian interests during the colonial era. The Qajar army suffered a major military defeat in the war and under the terms of the Treaty of Gulistan in 1813, Iran was forced to cede most of its Caucasian territories comprising modern day Georgia, Dagestan, and most of Azerbaijan.[22] The second Russo-Persian War of the late 1820s ended even more disastrously for Qajar Iran with temporary occupation of Tabriz and the signing of Treaty of Turkmenchay in 1828, acknowledging Russian sovereignty over the entire South Caucasus, as well as therefore the ceding of what is nowadays Armenia and the remaining part of Republic of Azerbaijan;[23] the new border between neighboring Russia and Iran were set at the Aras River. Iran had by these two treaties irrevocably lost the territories which had formed part of the concept of Iran for the last three centuries,[24] when only talking about its early modern to modern history.

Fath Ali Shah's reign saw increased diplomatic contacts with the West and the beginning of intense European diplomatic rivalries over Iran. His grandson Mohammad Shah, who fell under the Russian influence and made two unsuccessful attempts to capture Herat, succeeded him in 1834. When Mohammad Shah died in 1848 the succession passed to his son Nasser-e-Din, who proved to be the ablest and most successful of the Qajar sovereigns.[citation needed]

Development and decline

During Nasser-e-Din Shah's reign, Western science, technology, and educational methods were introduced into Persia and the country's modernization was begun. Nasser ed-Din Shah tried to exploit the mutual distrust between Great Britain and Russia to preserve Persia's independence, but foreign interference and territorial encroachment increased under his rule. He was not able to prevent Britain and Russia from encroaching into regions of traditional Persian influence. In 1856, during the Anglo-Persian War, Britain prevented Persia from reasserting control over Herat. The city had been part of Persia in Safavid times, but Herat had been under non-Persian rule since the mid-18th century. Britain also extended its control to other areas of the Persian Gulf during the 19th century. Meanwhile, by 1881, Russia had completed its conquest of present-day Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan, bringing Russia's frontier to Persia's northeastern borders and severing historic Persian ties to the cities of Bukhara and Samarqand. Several trade concessions by the Persian government put economic affairs largely under British control. By the late 19th century, many Persians believed that their rulers were beholden to foreign interests.

Mirza Taghi Khan Amir Kabir, was the young prince Nasser-e-Din's advisor and constable. With the death of Mohammad Shah in 1848, Mirza Taqi was largely responsible for ensuring the crown prince's succession to the throne. When Nasser ed-Din succeeded to the throne, Amir Nezam was awarded the position of prime minister and the title of Amir Kabir, the Great Ruler.

At that time, Persia was nearly bankrupt. During the next two and a half years Amir Kabir initiated important reforms in virtually all sectors of society. Government expenditure was slashed, and a distinction was made between the private and public purses. The instruments of central administration were overhauled, and Amir Kabir assumed responsibility for all areas of the bureaucracy. Foreign interference in Persia's domestic affairs was curtailed, and foreign trade was encouraged. Public works such as the bazaar in Tehran were undertaken. Amir Kabir issued an edict banning ornate and excessively formal writing in government documents; the beginning of a modern Persian prose style dates from this time.

One of the greatest achievements of Amir Kabir was the building of Dar ol Fonoon, the first modern university in Persia and the Middle East. Dar-ol-Fonoon was established for training a new cadre of administrators and acquainting them with Western techniques. Amir Kabir ordered the school to be built on the edge of the city so it could be expanded as needed. He hired French and Russian instructors as well as Persians to teach subjects as different as Language, Medicine, Law, Geography, History, Economics, and Engineering. Unfortunately, Amir Kabir did not live long enough to see his greatest monument completed, but it still stands in Tehran as a sign of a great man's ideas for the future of his country.

These reforms antagonized various notables who had been excluded from the government. They regarded the Amir Kabir as a social upstart and a threat to their interests, and they formed a coalition against him, in which the queen mother was active. She convinced the young shah that Amir Kabir wanted to usurp the throne. In October 1851 the shah dismissed him and exiled him to Kashan, where he was murdered on the shah's orders. Through his marriage to Ezzat od-Doleh, Amir Kabir had been the brother-in-law of the shah.

Constitutional Revolution

When Nasser al-Din Shah Qajar was assassinated by Mirza Reza Kermani in 1896, the crown passed to his son Mozaffar-e-din. Mozaffar-e-din Shah was a moderate, but relatively ineffective ruler. Royal extravagances coincided with an inadequate ability to secure state revenue which further exacerbated the financial woes of the Qajar. In response the Shah procured two large loans from Russia (in part to fund personal trips to Europe.) Public anger mounted as the Shah sold off concessions – such as road building monopolies, authority to collect duties on imports, etc. – to European interested in return for generous payments to the Shah and his officials. Popular demand to curb arbitrary royal authority in favor of rule of law increased as concern regarding growing foreign penetration and influence heightened.

The shah's failure to respond to protests by the religious establishment, the merchants, and other classes led the merchants and clerical leaders in January 1906 to take sanctuary from probable arrest in mosques in Tehran and outside the capital. When the shah reneged on a promise to permit the establishment of a "house of justice", or consultative assembly, 10,000 people, led by the merchants, took sanctuary in June in the compound of the British legation in Tehran. In August the shah, through the issue of a decree promised a constitution. In October an elected assembly convened and drew up a constitution that provided for strict limitations on royal power, an elected parliament, or Majles, with wide powers to represent the people, and a government with a cabinet subject to confirmation by the Majles. The shah signed the constitution on December 30, 1906, but refusing to forfeit all of his power to the Majles, attached a caveat that made his signature on all laws required for their enactment. He died five days later. The Supplementary Fundamental Laws approved in 1907 provided, within limits, for freedom of press, speech, and association, and for security of life and property. The hopes for constitutional rule were not realized, however.

Mozaffar-e-din Shah's son Mohammad Ali Shah (reigned 1907–1909), who, through his mother, was also the grandson of Prime-Minister Amir Kabir (see before), with the aid of Russia, attempted to rescind the constitution and abolish parliamentary government. After several disputes with the members of the Majlis, in June 1908 he used his Russian-officered Persian Cossacks Brigade (almost solely composed of Caucasian Muhajirs, to bomb the Majlis building, arrest many of the deputies, and close down the assembly. Resistance to the shah, however, coalesced in Tabriz, Isfahan, Rasht, and elsewhere. In July 1909, constitutional forces marched from Rasht to Tehran lead by Mohammad Vali Khan Sepahsalar Khalatbari Tonekaboni, deposed the Shah, and re-established the constitution. The ex-shah went into exile in Russia. Mohammad Ali Shah died in San Remo, Italy in April 1925. As fate would have it, every future Shah of Iran would also die in exile.

On 16 July 1909, the Majles voted to place Mohammad Ali Shah's 11-year-old son, Ahmad Shah on the throne. Although the constitutional forces had triumphed, they faced serious difficulties. The upheavals of the Constitutional Revolution and civil war had undermined stability and trade. In addition, the ex-shah, with Russian support, attempted to regain his throne, landing troops in July 1910. Most serious of all, the hope that the Constitutional Revolution would inaugurate a new era of independence from the great powers ended when, under the Anglo-Russian Agreement of 1907, Britain and Russia agreed to divide Persia into spheres of influence. The Russians were to enjoy exclusive right to pursue their interests in the northern sphere, the British in the south and east; both powers would be free to compete for economic and political advantage in a neutral sphere in the center. Matters came to a head when Morgan Shuster(also spelled Schuster), a United States administrator hired as treasurer general by the Persian government to reform its finances, sought to collect taxes from powerful officials who were Russian protégés and to send members of the treasury gendarmerie, a tax department police force, into the Russian zone. When in December 1911 the Majlis unanimously refused a Russian ultimatum demanding Shuster's dismissal, Russian troops, already in the country, moved to occupy the capital. To prevent this, on 20 December, Bakhtiari chiefs and their troops surrounded the Majles building, forced acceptance of the Russian ultimatum, and shut down the assembly, once again suspending the constitution.

Fall of the dynasty

Soltan Ahmad Shah was born 21 January 1898 in Tabriz, and succeeded to the throne at age 11. However, the occupation of Persia during World War I by Russian, British, and Ottoman troops was a blow from which Ahmad Shah never effectively recovered.

In February 1921, Reza Khan, commander of the Persian Cossack Brigade, staged a coup d'état, becoming the effective ruler of Iran. In 1923, Ahmad Shah went into exile in Europe. Reza Khan induced the Majles to depose Ahmad Shah in October 1925, and to exclude the Qajar dynasty permanently. Reza Khan was subsequently proclaimed Shah as Reza Shah Pahlavi, reigning from 1925 to 1941.

Ahmad Shah died on 21 February 1930 in Neuilly-sur-Seine, France.

Shahs of Persia, 1794–1925

| Name | Portrait | Title | Born-Died | Entered office | Left office | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mohammad Khan Qajar |

|

Shahanshah | 1742–1797 | 20 March 1794 | 17 June 1797 |

| 2 | Fat′h-Ali Shah Qajar |

|

Shahanshah | 1772–1834 | 17 June 1797 | 23 October 1834 |

| 3 | Mohammad Shah Qajar |

|

Shah | 1808–1848 | 23 October 1834 | 5 September 1848 |

| 4 | Naser al-Din Shah Qajar |

|

Shahanshah | 1831–1896 | 5 September 1848 | 1 May 1896 |

| 5 | Mozaffar al-Din Shah Qajar |

|

Shahanshah and Sultan | 1853–1907 | 1 May 1896 | 3 January 1907 |

| 6 | Mohammad Ali Shah Qajar |

|

Shahanshah | 1872–1925 | 3 January 1907 | 16 July 1909 |

| 7 | Ahmad Shah Qajar |

|

Sultan | 1898–1930 | 16 July 1909 | 15 December 1925 |

Qajar Royal Family

The Qajar Imperial Family in exile is currently headed by the eldest descendant of Mohammad Ali Shah, Soltan Mohammad Ali Mirza Qajar, while the Heir Presumptive to the Qajar throne is Mohammad Hassan Mirza II, the grandson of Mohammad Hassan Mirza, Soltan Ahmad Shah's brother and heir. Mohammad Hassan Mirza died in England in 1943, having proclaimed himself shah in exile in 1930 after the death of his brother in France.

Today, the descendants of the Qajars often identify themselves as such and hold reunions to stay socially acquainted through the Kadjar Family Association.[25]

Qajar dynasty since 1925

- Heads of the Qajar Imperial Family

The headship of the Imperial Family is inherited by the eldest male descendant of Mohammad Ali Shah.

- Soltan Ahmad Shah Qajar (1925–1930)

- Fereydoun Mirza (1930–1975)

- Soltan Hamid Mirza (1975–1988)

- Soltan Mahmoud Mirza (1988)

- Soltan Ali Mirza Qajar (1988–2011)

- Soltan Mohammad Ali Mirza (2011–present)

- Heirs Presumptive of the Qajar dynasty

The Heir Presumptive is the Qajar heir to the Persian throne.

- Soltan Ahmad Shah Qajar (1925–1930)

- Mohammad Hassan Mirza (1930–1943)

- Fereydoun Mirza (1943–1975)

- Soltan Hamid Mirza (1975–1988)

- Mohammad Hassan Mirza II (1988–present)

Notable members of Qajar family

- Politics

- Prince Abdol Hossein Mirza Farmanfarma (1859-1939), prime minister of Iran

- Prince Firouz Mirza Nosrat-ed-Dowleh Farman Farmaian III (1889-1937), son of former, foreign minister of Iran

- Amir Abbas Hoveyda, Iranian economist and politician, prime minister of Iran from 1965 to 1977, a qajar descendant on his maternal side

- Ali Amini, prime minister of Iran

- Prince Iraj Eskandari, Iranian communist politician

- Princess Maryam Farman Farmaian (b. 1914-d. 2008) Iranian communist politician, founder of the women's section of the Tudeh Party of Iran

- Ardeshir Zahedi (b. 1928–) Iranian diplomat, qajar descendant on his maternal side

- Military

- Prince Amanullah Mirza Qajar, Imperial Russian, Azerbaijani, and Iranian military commander

- Social work

- Princess Sattareh Farmanfarmaian, Iranian Social work pioneer

- Prince Sabbar Farmanfarmaian, health minister in Mosaddeq cabinet

- Business

- Princess Fakhr-ol-dowleh

- Mariam Faroughy-Qajar, entrepreneur and linguist

- Women rights

- Princess Mohtaram Eskandari, intellectual and pioneering figures in Iranian women's movement

- Literature

- Prince Iraj Mirza (b. 1874-d. 1926), Iranian poet and translator

- Princess Lobat Vala (b. 1930), Iranian poet and campaigner for the Women Liberation

- Nader Naderpour, Iranian poet, a Qajar descendant on his maternal side

- Shahrnush Parsipur, Iranian novelist, a Qajar descendant on her maternal side

- Music

- Gholam-Hossein Banan, Iranian musician and singer, Qajar descendant on his maternal side

- Popular culture

- Marjane Satrapi, Iranian graphic novelist, Qajar descendant on her maternal side

- Entertainment

- Princess Shireen Fathi, an American-Iranian performer, most notably as a dancer in the Persian Parade held annually in New York City, a Qajar descendant on her paternal side

- Sarah Shahi, an American actress, a Qajar descendant on her paternal side

See also

Template:Former monarchic orders of succession

- Abdolhossein Teymourtash

- Austro-Hungarian Military Mission in Persia

- History of Iran

- Khanates of the Caucasus

- List of kings of Persia

- List of Shi'a Muslims dynasties

- Mirza Kouchek Khan

- Qajar art

References

- ^ Homa Katouzian, "State and Society in Iran: The Eclipse of the Qajars and the Emergence of the Pahlavis", Published by I.B.Tauris, 2006. pg 327: "In post-Islamic times, the mother-tongue of Iran's rulers was often Turkic, but Persian was almost invariably the cultural and administrative language"

- ^ Homa Katouzian, "Iranian history and politics", Published by Routledge, 2003. pg 128: "Indeed, since the formation of the Ghaznavids state in the tenth century until the fall of Qajars at the beginning of the twentieth century, most parts of the Iranian cultural regions were ruled by Turkic-speaking dynasties most of the time. At the same time, the official language was Persian, the court literature was in Persian, and most of the chancellors, ministers, and mandarins were Persian speakers of the highest learning and ability"

- ^ Ardabil Becomes a Province: Center-Periphery Relations in Iran, H. E. Chehabi, International Journal of Middle East Studies, Vol. 29, No. 2 (May, 1997), 235;"Azeri Turkish was widely spoken at the two courts in addition to Persian, and Mozaffareddin Shah (r.1896-1907) spoke Persian with an Azeri Turkish accent....".

- ^ علیاصغر شمیم، ایران در دوره سلطنت قاجار، تهران: انتشارات علمی، ۱۳۷۱، ص ۲۸۷

- ^ a b Abbas Amanat, The Pivot of the Universe: Nasir Al-Din Shah Qajar and the Iranian Monarchy, 1831–1896, I.B.Tauris, pp 2–3

- ^ a b "Genealogy and History of Qajar (Kadjar) Rulers and Heads of the Imperial Kadjar House".

- ^ a b c d e Cyrus Ghani. Iran and the Rise of the Reza Shah: From Qajar Collapse to Pahlavi Power, I.B. Tauris, 2000, ISBN 1-86064-629-8, p. 1

- ^ a b William Bayne Fisher. Cambridge History of Iran, Cambridge University Press, 1993, p. 344, ISBN 0-521-20094-6

- ^ a b Dr Parviz Kambin, A History of the Iranian Plateau: Rise and Fall of an Empire, Universe, 2011, p.36, online edition.

- ^ Jamie Stokes, Anthony Gorman, Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Africa and the Middle East, 2010, p.707, Online Edition, The Safavid and Qajar dynasties, rulers in Iran from 1501 to 1722 and from 1795 to 1925 respectively, were Turkic in origin.

- ^ Abbas Amanat, The Pivot of the Universe: Nasir Al-Din Shah Qajar and the Iranian Monarchy, 1831–1896, I.B.Tauris, pp 2–3; "In the 126 years between the fall of the Safavid state in 1722 and the accession of Nasir al-Din Shah, the Qajars evolved from a shepherd-warrior tribe with strongholds in northern Iran into a Persian dynasty.."

- ^ Choueiri, Youssef M., A companion to the history of the Middle East, (Blackwell Ltd., 2005), 231,516.

- ^ H. Scheel; Jaschke, Gerhard; H. Braun; Spuler, Bertold; T Koszinowski; Bagley, Frank (1981). Muslim World. Brill Archive. pp. 65, 370. ISBN 978-90-04-06196-5. Retrieved 28 September 2012.

- ^ "Qajar Dynasty on Encyclopædia Britannica". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ^ Timothy C. Dowling Russia at War: From the Mongol Conquest to Afghanistan, Chechnya, and Beyond pp 729 ABC-CLIO, 2 dec. 2014 ISBN 1598849484

- ^ IRAN ii. IRANIAN HISTORY (2) Islamic period, Ehsan Yarshater, Encyclopædia Iranica, (March 29, 2012).[1]

- ^ K. M. Röhrborn, Provinzen und Zentralgewalt Persiens im 16. und 17. Jahrhundert, Berlin, 1966, p. 4

- ^ Encyclopedia Iranica. Ganja. Online Edition

- ^ Keddie, Nikki R. (1971). "The Iranian Power Structure and Social Change 1800–1969: An Overview". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 2 (1): 3–20 [p. 4]. doi:10.1017/S0020743800000842.

- ^ Lapidus, Ira Marvin (2002). A History of Islamic Societies. Cambridge University Press. p. 469. ISBN 0-521-77933-2.

- ^ Fisher, William Bayne (1991). The Cambridge History of Iran. Cambridge University Press. pp. 145–146.

Even when rulers on the plateau lacked the means to effect suzerainty beyond the Aras, the neighboring Khanates were still regarded as Iranian dependencies. Naturally, it was those Khanates located closes to the province of Azarbaijan which most frequently experienced attempts to re-impose Iranian suzerainty: the Khanates of Erivan, Nakhchivan and Qarabagh across the Aras, and the cis-Aras Khanate of Talish, with its administrative headquarters located at Lankaran and therefore very vulnerable to pressure, either from the direction of Tabriz or Rasht. Beyond the Khanate of Qarabagh, the Khan of Ganja and the Vali of Gurjistan (ruler of the Kartli-Kakheti kingdom of south-east Georgia), although less accessible for purposes of coercion, were also regarded as the Shah's vassals, as were the Khans of Shakki and Shirvan, north of the Kura river. The contacts between Iran and the Khanates of Baku and Qubba, however, were more tenuous and consisted mainly of maritime commercial links with Anzali and Rasht. The effectiveness of these somewhat haphazard assertions of suzerainty depended on the ability of a particular Shah to make his will felt, and the determination of the local khans to evade obligations they regarded as onerous.

- ^ Timothy C. Dowling Russia at War: From the Mongol Conquest to Afghanistan, Chechnya, and Beyond pp 729 ABC-CLIO, 2 dec. 2014 ISBN 1598849484

- ^ Timothy C. Dowling Russia at War: From the Mongol Conquest to Afghanistan, Chechnya, and Beyond pp 729 ABC-CLIO, 2 dec. 2014 ISBN 1598849484

- ^ Fisher et al. 1991, p. 329.

- ^ "Qajar People". Qajars. Retrieved 31 October 2012.

Sources

- Fisher, William Bayne; Avery, P.; Hambly, G. R. G; Melville, C. (1991). The Cambridge History of Iran. Vol. 7. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521200954.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)