Rain Man

| Rain Man | |

|---|---|

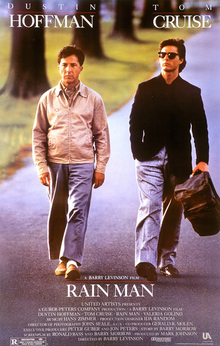

Theatrical release poster by John Alvin | |

| Directed by | Barry Levinson |

| Screenplay by | |

| Story by | Barry Morrow |

| Produced by | Mark Johnson |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | John Seale |

| Edited by | Stu Linder |

| Music by | Hans Zimmer |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | MGM/UA Communications Co. |

Release date |

|

Running time | 134 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States[1] |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $25 million[2] |

| Box office | $354.8 million[2][3] |

Rain Man is a 1988 American road drama film directed by Barry Levinson and written by Barry Morrow and Ronald Bass. It tells the story of abrasive, selfish young wheeler-dealer Charlie Babbitt (Tom Cruise), who discovers that his estranged father has died and bequeathed virtually all of his multimillion-dollar estate to his other son, Raymond (Dustin Hoffman), an autistic savant, of whose existence Charlie was unaware. Charlie is left with only his father's beloved vintage car and rosebushes. Valeria Golino also stars as Charlie's girlfriend Susanna. Morrow created the character of Raymond after meeting Kim Peek, a real-life savant; his characterization was based on both Peek and Bill Sackter, a good friend of Morrow who was the subject of Bill (1981), an earlier film that Morrow wrote.[4]

Rain Man premiered at the 39th Berlin International Film Festival, where it won the Golden Bear, the festival's highest prize.[5] It was theatrically released by MGM/UA Communications Co. in the United States on December 16, 1988, to critical and commercial success. Praise was given towards Levinson's direction, the performances (particularly Cruise's and Hoffman's), the instrumental score, Morrow's screenplay, the cinematography, and the film's portrayal of autism. The film grossed $354 million, on a $25-million budget, becoming the highest-grossing film of 1988, and received a leading eight nominations at the 61st Academy Awards, winning four (more than any other film nominated); Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actor (for Hoffman), and Best Original Screenplay.[6]

As of 2022[update], Rain Man is the first and only film to win both the Berlin International Film Festival's highest award and the Academy Award for Best Picture in the same year. It was also the last MGM title to be nominated for Best Picture until Licorice Pizza (2021) 33 years later.[7]

Plot

Collectibles dealer Charlie Babbitt is in the middle of importing four grey market Lamborghinis to Los Angeles for resale. He needs to deliver the cars to impatient buyers, who have already made down payments, in order to repay the loan he took out to buy them, but the EPA is holding the cars at the port because they have failed emission tests. Charlie directs an employee to lie to the buyers while he stalls his creditor.

When Charlie learns that his estranged father Sanford Babbitt has died, he and his girlfriend Susanna travel to Cincinnati in order to settle the estate. He inherits only a group of rosebushes and a classic 1949 Buick Roadmaster convertible over which he and his father had clashed, while the remainder of the $3-million estate is going to an unnamed trustee. He learns that the money is being directed to a local mental institution, where he meets his elder brother, Raymond, of whom he was unaware his whole life.

Raymond has savant syndrome and autism and adheres to strict routines. He has superb recall, but he shows little emotional expression except when in distress. Charlie spirits Raymond out of the mental institution and into a hotel for the night. Disgusted with the way Charlie treats his brother, Susanna leaves him. Charlie asks Raymond's doctor, Dr. Gerald Bruner, for half the estate in exchange for Raymond's return, but Bruner refuses. Charlie decides to attempt to gain custody of his brother in order to get control of the money.

After Raymond refuses to fly to Los Angeles, he and Charlie resort to driving there instead. They make slow progress because Raymond insists on sticking to his routines, which include watching The People's Court on television every day, getting to bed by 11:00 p.m., and refusing to travel when it rains. He also objects to traveling on the interstate after they encounter a car accident. During the course of the journey, Charlie learns more about Raymond, including his ability to instantly perform complex calculations and count hundreds of objects at once, far beyond the normal range of human abilities. He also realizes Raymond had lived with the family as a child and was the "Rain Man" (Charlie's infantile pronunciation of "Raymond"), a comforting figure that Charlie had falsely remembered as an imaginary friend. Raymond had saved an infant Charlie from being scalded by hot bathwater one day, but their father had blamed him for nearly injuring Charlie and committed him to the institution, as he was unable to speak up for himself and correct the misunderstanding.

Charlie's creditor repossesses the Lamborghinis, forcing him to refund his buyers' down payments and leaving him deeply in debt. Having passed Las Vegas, he and Raymond return to Caesars Palace on the Strip and devise a plan to win the needed money by playing blackjack and counting cards. Though the casino bosses obtain videotape evidence of the scheme and ask them to leave, Charlie successfully wins $86,000 to cover his debts and reconciles with Susanna, who has rejoined the brothers in Las Vegas.

Returning to Los Angeles, Charlie meets with Bruner, who offers him $250,000 to walk away from Raymond. Charlie refuses and says that he is no longer upset about being cut out of his father's will, but he wants to have a relationship with his brother. At a meeting with a court-appointed psychiatrist, Raymond proves unable to decide for himself what he wants. Charlie stops the questioning and tells Raymond he is happy to have him as his brother. As Raymond and Bruner board a train to return to the institution, Charlie promises to visit in two weeks.

Cast

- Dustin Hoffman as Raymond "Ray" Babbitt

- Tom Cruise as Charles Sanford "Charlie" Babbitt

- Valeria Golino as Susanna

- Jerry Molen as Dr. Gerald Bruner

- Ralph Seymour as Lenny

- Michael D. Roberts as Vern

- Bonnie Hunt as Sally Dibbs

- Beth Grant as Mother at Farm House

- Lucinda Jenney as Iris

- Barry Levinson as Doctor

- Bob Heckel as Sheriff Deputy

Production

In drafting the story for Rain Man, Barry Morrow decided to base the Dustin Hoffman's character, Raymond Babbitt, on his experiences with both Kim Peek and Bill Sackter, two men who had gained notoriety and fame for their intellectual disabilities and furthermore, in Kim Peek's case, for his abilities as a savant, showing themselves in high speed reading and extremely detailed memory. Prior to the conception of Rain Man, Morrow had formed a friendship with the intellectually disabled Sackter, and in doing so ended up taking some situational aspects from his friendship and using them to help craft the relationship between Charlie and Raymond. Following the success of the made-for-TV movie he had written about Sackter, Bill, Morrow met Kim Peek and was wildly intrigued by his Savant Syndrome. Initially going into the creation of the film, Morrow was essentially unaware of the intricacies of the condition, as well as of autism itself, deciding instead the movie was less about Raymond's intellectual disability and more about the relationship formed between Raymond and Charlie.[8]

Roger Birnbaum was the first studio executive to give the film a green light; he did so immediately after Barry Morrow pitched the story. Birnbaum received "special thanks" in the film's credits.[1]

Real-life brothers Dennis Quaid and Randy Quaid were considered for the roles of Raymond Babbitt and Charles Babbitt.[9] Agents at CAA sent the script to Dustin Hoffman and Bill Murray, envisioning Murray in the title role and Hoffman in the role eventually portrayed by Cruise.[4][10] Martin Brest, Steven Spielberg and Sydney Pollack were directors also involved in the film.[11] Spielberg was attached to the film for five months, until he left to promise George Lucas to direct Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, and he would later regret the decision.[12][13] Mickey Rourke was also offered a role but he turned it down.[14] Mel Gibson was also offered the role of Raymond but he turned it down.[15]

For a year prior to playing Raymond Babbitt, Hoffman prepared to portray Raymond's autism by seeking out and educating himself on other autistic people, particularly those with Savant Syndrome. Hoffman had some experience with disabled individuals prior to filming, having worked at the New York Psychiatric Institute when he was younger. Inspiration for the portrayal of Raymond Babbitt's mannerisms was drawn from a multitude of sources, including Kim Peek and the autistic brother of a Princeton football player with whom Hoffman was in touch at the time. Part of Hoffman's research into the role also included in-person meetings with savant Kim Peek, wherein he would observe and mimic Peek's actions in order to attempt to give an accurate portrayal at what an individual with Savant Syndrome might act like. His mimicry of Peek's Savant Syndrome was deemed a poor fit for the character by Hoffman, resulting in Hoffman's deciding to make Babbitt not only a man with Savant Syndrome, but also an autistic man.[8] This decision was one that proved only to further the misunderstanding of autism spectrum disorder among the general public: though autism is, in itself, a varying condition with numerous ways in which it is characterized, having both autism and Savant Syndrome is a rare occurrence[16] (it is estimated around 1 in 200 people with autism are also savants[17]). Even so, audiences were swayed into thinking that most autistic individuals were intellectually capable of savant abilities largely by Hoffman's portrayal of Raymond Babbitt.

Principal photography included nine weeks of filming on location in Cincinnati and throughout northern Kentucky.[18] Other portions were shot in the desert near Palm Springs, California.[19]: 168–71

There was originally a different ending to the movie drafted by Morrow which differed from Raymond's going back to the institution. Morrow ultimately decided to drop this ending in favor of Raymond's returning to the institution, as he felt the original ending would not have stuck with the viewers as effectively as the revised ending did.[8]

Almost all of the principal photography occurred during the 1988 Writers Guild of America strike; one key scene that was affected by the lack of writers was the film's final scene.[4] Bass delivered his last draft of the script only hours before the strike started and spent no time on the set.[11]

Release

Box office

Rain Man debuted on December 16, 1988, and was the second highest-grossing film at the weekend box office (behind Twins), with $7 million.[20] It reached the first spot on the December 30 – January 2 weekend, finishing 1988 with $42 million.[21] The film would end up as the highest-grossing U.S. film of 1988 by earning over $172 million. Worldwide figures vary; Box Office Mojo claims that the film grossed over $354 million worldwide,[2] while The Numbers reported that the film grossed $412.8 million worldwide.[3]

Critical response

On review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes the film holds an approval rating of 89% based on 133 reviews, with an average rating of 8.10/10. The website's critical consensus states: "This road-trip movie about an autistic savant and his callow brother is far from seamless, but Barry Levinson's direction is impressive, and strong performances from Tom Cruise and Dustin Hoffman add to its appeal."[22] Metacritic assigned the film a weighted average score of 65 out of 100 based on 18 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[23] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "A" on an A+ to F scale.[24]

Vincent Canby of The New York Times called Rain Man a "becomingly modest, decently thought-out, sometimes funny film"; Hoffman's performance was a "display of sustained virtuosity . . . [which] makes no lasting connections with the emotions. Its end effect depends largely on one's susceptibility to the sight of an actor acting nonstop and extremely well, but to no particularly urgent dramatic purpose."[25] Canby considered the "film's true central character" to be "the confused, economically and emotionally desperate Charlie, beautifully played by Mr. Cruise."[25]

Amy Dawes of Variety wrote that "one of the year's most intriguing film premises ... is given uneven, slightly off-target treatment"; she called the road scenes "hastily, loosely written, with much extraneous screen time," but admired the last third of the film, calling it a depiction of "two very isolated beings" who "discover a common history and deep attachment."[26]

One of the film's harshest reviews came from New Yorker magazine critic Pauline Kael, who said, "Everything in this movie is fudged ever so humanistically, in a perfunctory, low-pressure way. And the picture has its effectiveness: people are crying at it. Of course they're crying at it—it's a piece of wet kitsch."[27]

Roger Ebert gave the film three and a half stars out of four. He wrote, "Hoffman proves again that he almost seems to thrive on impossible acting challenges...I felt a certain love for Raymond, the Hoffman character. I don't know quite how Hoffman got me to do it."[28] Gene Siskel also gave the film three and a half stars out of four, singling out Cruise for praise: "The strength of the film is really that of Cruise's performance...the combination of two superior performances makes the movie worth watching."[29]

Rain Man was placed on 39 critics' "ten best" lists in 1988, based on a poll of the nation's top 100 critics.[30]

Accolades

Legacy

The release of Rain Man in 1988 coincided with a tenfold increase in funding for medical research and diagnoses of individuals for autism. The latter is primarily due to autism's being more broadly defined in newer editions of the DSM, particularly versions III-R and IV.[43]: 389–401 The movie is credited, however, with significantly increasing awareness of autism among the general public.[43]: 354-380

Rain Man is a movie famous in particular for its portrayal of a man with both autism and Savant Syndrome, leading much of its viewing audience to incorrectly understand the intellectual capabilities of autistic people.[8] The character of Raymond Babbitt has been criticized for fitting into the stereotype of the "Magical/Savant" autistic character. Characters like these are portrayed as having an otherworldly intellectual ability that, rather than disable them from living a "normal" life, instead assists them in a nearly magical way, causing those around them to be in awe and wonder as to how a person might have this capability. While having Savant Syndrome is certainly a possibility for autistic individuals, the combination is incredibly rare.[16]

In 2006, the film was recognized by the American Film Institute in their list of 100 Years...100 Cheers at #63.[44]

In popular culture

Rain Man's portrayal of the main character's condition has been seen as creating the erroneous media stereotype that people on the autism spectrum typically have savant skills, and references to Rain Man, in particular Dustin Hoffman's performance, have become a popular shorthand for autism and savantism. Conversely, Rain Man has also been seen as dispelling a number of other misconceptions about autism, and improving public awareness of the failure of many agencies to accommodate autistic people and make use of the abilities they do have, regardless of whether they have savant skills or not.[45]

The film is also known for popularizing the misconception that card counting is illegal in the United States.[46]

The cold open sketch in the April 1, 1989 installment of Saturday Night Live spoofed both the film and the Pete Rose gambling scandal at the time. Charlie and Raymond Babbitt were played by Ben Stiller and Dana Carvey respectively, with Phil Hartman as Rose.[47]

The Babbitt brothers appear in The Simpsons season 5 episode "$pringfield". The film is mentioned in numerous other films such as Miss Congeniality (2000), 21 (2008), Tropic Thunder (2008) (in which Tom Cruise made an appearance), The Hangover (2009), Escape Room (2019), and also in the television series Breaking Bad and Barry.

Raymond Babbitt was caricatured as a rain cloud in the animated episode of The Nanny, "Oy to the World". During the episode, Fran fixes up CC the Abominable Babcock with the Rain Man. He is portrayed as a cloud of rain mumbling about weather patterns and being an excellent driver.

In the final episode of the first season of Community Pierce calls Abed "Rain Man" when listing off members of the study group. Abed had been described before as having Asperger's Syndrome, which is now diagnosed as Autism Spectrum Disorder.[48]

In the 2015 biographical drama film Steve Jobs, when Jobs (played by Michael Fassbender) was being confronted by Apple CEO John Sculley (Jeff Daniels), he referred to co-founder Steve Wozniak (Seth Rogen) as "Rain Man."

In Fear Street Part One: 1994, Simon, surprised by Josh's knowledge of a seemingly unknown girl who had attacked him, says: "Jesus, Rain Man. How [...] do you know that?".

Qantas and airline controversy

During June 1989, at least fifteen major airlines showed edited versions of Rain Man that omitted a scene involving Raymond's refusal to fly, mentioning the crashes of American Airlines Flight 625, Delta Air Lines Flight 191, and Continental Airlines Flight 1713, except on Australia-based Qantas. Those criticizing this decision included film director Barry Levinson, co-screenwriter Ronald Bass, and George Kirgo (at the time the President of the Writers Guild of America, West). "I think it's a key scene to the entire movie," Levinson said in a telephone interview. "That's why it's in there. It launches their entire odyssey across country – because they couldn't fly." While some of those airlines cited as justification avoiding having airplane passengers feel uncomfortable in sympathy with Raymond during the in-flight entertainment, the scene was shown intact on flights of Qantas, and commentators noted that Raymond mentions it as the only airline whose planes have "never crashed".[49][50]

The film is credited with introducing Qantas's safety record to U.S. consumers.[51][52] However, contrary to the claims made in the film, Qantas aircraft have been involved in a number of fatal accidents since the airline's founding in 1920, though none involving jet aircraft, with the last incident taking place in December 1951.[53]

The Buick convertible

Two 1949 Roadmaster convertibles were used in the filming, one of which had its rear suspension stiffened to bear the additional load of camera equipment and a cameraman. After filming completed, the unmodified car was acquired by Hoffman, who had it restored, added it to his collection and kept it for 34 years. Hemmings Motor News reported that this car was auctioned in January 2022 by Bonhams at Scottsdale, Arizona and sold for $335,000.[54] The camera-carrying car was similarly acquired by Barry Levinson, who a few years later had it restored by Wayne Carini of the Chasing Classic Cars television series.

See also

Notes

- ^ Tied with Martin Landau for Tucker: The Man and His Dream and Dean Stockwell for Married to the Mob.

References

- ^ a b c d e "Rain Man (1988)". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Archived from the original on November 5, 2018. Retrieved November 5, 2018.

- ^ a b c Rain Man at Box Office Mojo

- ^ a b "Rain Man (1988) - Financial Information". The Numbers.

- ^ a b c Barry Morrow's audio commentary for Rain Man from the DVD release.

- ^ "Berlinale: 1989 Prize Winners". berlinale.de. Archived from the original on June 9, 2019. Retrieved March 13, 2011.

- ^ a b "The 61st Academy Awards (1989) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Archived from the original on May 2, 2019. Retrieved July 31, 2011.

- ^ Tartaglione, Nancy (February 9, 2022). "MGM's Michael de Luca & Pam Abdy on Studio's First In-House Best Picture Oscar Nomination in 33 Years, Being "Mildly Psychotically Obsessive" About Movies & What's Ahead – Q&A". Deadline Hollywood.

- ^ a b c d "Rain Man at 30: damaging stereotype or 'the best thing that happened to autism'?". the Guardian. December 13, 2018. Retrieved May 9, 2022.

- ^ Mell, Eila (January 24, 2015). Casting Might-Have-Beens: A Film by Film Directory of Actors Considered for Roles Given to Others. ISBN 9781476609768.

- ^ Patches, Matt (January 9, 2014). "Remembering 'Rain Man': The $350 Million Movie That Hollywood Wouldn't Touch Today". Grantland. Retrieved June 9, 2023.

- ^ a b Bass' audio commentary for Rain Man from the DVD release.

- ^ Guidry, Ken (June 11, 2013). "Watch: 36-Minute 1990 Interview With Steven Spielberg, Regrets Passing On 'Rain Man' For 'Indy 3' & More".

- ^ "» Old Interview Footage Shows Spielberg Regretted Skipping Rain Man to do Last Crusade".

- ^ "Mickey Rourke: a life in film". Time Out. Archived from the original on May 9, 2018. Retrieved September 10, 2015.

- ^ "Mel Gibson Wishes He Would Have Said Yes To Dustin Hoffman's Role In 'Rain Man'". theplaylist.net.

- ^ a b Prochnow, Alexandria (2014). "An Analysis of Autism Through Media Representation". ETC: A Review of General Semantics. 71 (2): 133–149. ISSN 0014-164X. JSTOR 24761922.

- ^ Baron-Cohen, Simon (2020). The pattern seekers : how autism drives human invention (First ed.). New York: Basic Books. p. 58. ISBN 978-1-5416-4714-5.

- ^ Alter, Maxim; Maxwell, Emily (February 28, 2014). "Then and Now: A look back at 'Rain Man' in Cincinnati and Northern Kentucky". WCPO. Retrieved January 10, 2022.

- ^ Niemann, Greg (2006). Palm Springs Legends: creation of a desert oasis. San Diego, CA: Sunbelt Publications. p. 286. ISBN 978-0-932653-74-1. OCLC 61211290. (here for Table of Contents Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ "Weekend Box Office: December 16–18, 1988". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on September 9, 2017. Retrieved April 20, 2020.

- ^ "Weekend Box Office: December 30 – January 2, 1988". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on September 24, 2018. Retrieved April 20, 2020.

- ^ "Rain Man (1988)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Archived from the original on June 24, 2022. Retrieved August 3, 2022.

- ^ "Rain Man Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on March 11, 2018. Retrieved March 1, 2018.

- ^ "Cinemascore :: Movie Title Search". December 20, 2018. Archived from the original on December 20, 2018. Retrieved July 27, 2020.

- ^ a b Canby, Vincent (December 16, 1988). "Review/Film; Brotherly Love, of Sorts". The New York Times. Retrieved February 27, 2023.

- ^ Dawes, Amy (December 14, 1988). "Rain Man". Variety. Archived from the original on February 28, 2009.

- ^ Kael, Pauline (February 6, 1989). "Stunt". The New Yorker. Retrieved February 17, 2023 – via Scraps From The Loft.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (December 16, 1988). "Rain Man movie review & film summary (1988)". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on December 6, 2022. Retrieved February 27, 2023.

- ^ Siskel, Gene (December 16, 1988). "Cruise's Performance Gives 'Rain Man' Strength". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on February 27, 2023. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ "100 Film Critics Can't Be Wrong, Can They? : The critics' consensus choice for the 'best' movie of '88 is . . . a documentary!". Los Angeles Times. January 8, 1989. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- ^ "The ASC Awards for Outstanding Achievement in Cinematography". Archived from the original on August 2, 2011.

- ^ "PRIZES & HONOURS 1989". Berlin International Film Festival. Retrieved July 10, 2021.

- ^ "BAFTA Awards: Film in 1990". BAFTA. 1990. Retrieved September 16, 2016.

- ^ "The 1990 Caesars Ceremony". César Awards. Retrieved July 10, 2021.

- ^ "Chicago Film Critics Awards – 1988–97". Chicago Film Critics Association. Archived from the original on April 22, 2016. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ^ "41st DGA Awards". Directors Guild of America Awards. Retrieved July 10, 2021.

- ^ "Rain Man – Golden Globes". HFPA. Retrieved July 10, 2021.

- ^ "KCFCC Award Winners – 1980-89". December 14, 2013. Retrieved July 10, 2021.

- ^ "Past Awards". National Society of Film Critics. December 19, 2009. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "1988 New York Film Critics Circle Awards". Mubi. Retrieved July 10, 2021.

- ^ "People's Choice Awards honor public favorites - UPI Archives". UPI. March 12, 1989. Retrieved February 27, 2023.

- ^ "Awards Winners". wga.org. Writers Guild of America. Archived from the original on December 5, 2012. Retrieved June 6, 2010.

- ^ a b Silberman, Steve (2015). NeuroTribes. New York: Avery. ISBN 978-1-58333-467-6.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years…100 Cheers". American Film Institute. Retrieved February 27, 2023.

- ^ Treffert, Darold. "Rain Man, the Movie/Rain Man, Real Life". Wisconsin Medical Society. Archived from the original on August 27, 2015. Retrieved September 29, 2014.

- ^ Rose, I. Nelson; Loeb, Robert A. (1999). Blackjack and the Law. Rge Pub. ISBN 978-0-910575-08-9.

- ^ NBC photograph of the Saturday Night Live sketch spoofing Rain Man and the Pete Rose gambling scandal from April 1, 1989. Retrieved May 26, 2023.

- ^ VanDerWerff, Emily (May 21, 2010). "Community: "Pascal's Triangle Revisited"". The A.V. Club. Retrieved May 5, 2023.

- ^ "Airlines Cut Scene From 'Rain Man'". The New York Times. June 29, 1989. Archived from the original on June 13, 2015. Retrieved June 6, 2015.

- ^ Weinstein, Steve (June 29, 1989). "Uneasy Airlines Get Final Cut on 'Rain Man'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 16, 2015. Retrieved June 6, 2015.

- ^ Kamenev, Marina (November 24, 2010). "Qantas: Airline Safety's Golden Child No More?". Time. Archived from the original on May 24, 2015. Retrieved June 6, 2015.

- ^ "Is Qantas still the world's safest airline?". News.com.au. January 7, 2014. Archived from the original on January 7, 2014. Retrieved June 6, 2015.

- ^ Palmer, Brian (November 1, 2011). "Is Qantas The World's Safest Airline?". Slate. Archived from the original on May 24, 2015. Retrieved May 5, 2022.

- ^ Symes, Steven (January 31, 2022). "Rain Man Buick Roadmaster Sells For $335,000". motorious.com. Retrieved February 1, 2022.

External links

- Rain Man at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- Rain Man at IMDb

- Rain Man at AllMovie

- Rain Man at the TCM Movie Database

- Rain Man at Box Office Mojo

- Rain Man at Rotten Tomatoes

- Rain Man at Metacritic

- 1988 films

- 1988 drama films

- 1980s buddy drama films

- 1980s American films

- 1980s English-language films

- 1980s road comedy-drama films

- American drama films

- American buddy drama films

- American road comedy-drama films

- Best Drama Picture Golden Globe winners

- Best Picture Academy Award winners

- Films about autism

- Films about brothers

- Films about disability in the United States

- Films about gambling

- Films about obsessive–compulsive disorder

- Films directed by Barry Levinson

- Films featuring a Best Actor Academy Award-winning performance

- Films featuring a Best Drama Actor Golden Globe winning performance

- Films scored by Hans Zimmer

- Films set in 1988

- Films set in Cincinnati

- Films set in Los Angeles

- Films set in Missouri

- Films set in the Las Vegas Valley

- Films shot in California

- Films shot in Indiana

- Films shot in Kentucky

- Films shot in Nevada

- Films shot in Ohio

- Films shot in Oklahoma

- Films shot in the Las Vegas Valley

- Films whose director won the Best Directing Academy Award

- Films whose writer won the Best Original Screenplay Academy Award

- Films with screenplays by Ronald Bass

- Golden Bear winners

- Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer films

- United Artists films