Z-machine

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

The Z-machine is a virtual machine that was developed by Joel Berez and Marc Blank in 1979 and used by Infocom for its text adventure games. Infocom compiled game code to files containing Z-machine instructions (called story files, or Z-code files), and could therefore port all its text adventures to a new platform simply by writing a Z-machine implementation for that platform. With the large number of incompatible home computer systems in use at the time, this was an important advantage over using native code or developing a compiler for each system.

The "Z" of Z-machine stands for Zork, Infocom's first adventure game. Z-code files usually have names ending in .z1, .z2, .z3, .z4, .z5, .z6, .z7 or .z8, where the number is the version number of the Z-machine on which the file is intended to be run, as given by the first byte of the story file. Version# and specification. This is a modern convention, however. Infocom itself used extensions of .dat (Data) and .zip (ZIP = Z-machine Interpreter Program), but the latter clashes with the present widespread use of .zip for PKZIP-compatible archive files starting in the 1990s, after Activision had shut down Infocom. Infocom produced six versions of the Z-machine. Files using versions 1 and 2 are very rare. Only two version 1 files are known to have been released by Infocom, and only two of version 2. Version 3 covers the vast majority of Infocom's released games. The later versions had more capabilities, culminating in some graphic support in version 6.

After Mediagenic relocated Infocom to California in 1989, Computer Gaming World stated that "ZIL ... is functionally dead", and reported rumors of a "completely new parser that may never be used".[1] The compiler (called Zilch) that Infocom used to produce its story files has never been released, although documentation of the language used (called ZIL, for Zork Implementation Language) still exists and an open-source replacement (called ZILF) has been written. In May 1993, Graham Nelson released the first version of his Inform compiler, which also generates Z-machine story files as its output, even though the Inform source language is quite different from ZIL. Most files produced by Inform are version 5.

Inform has since become very popular in the interactive fiction community and, as a consequence, a large proportion of the interactive fiction now produced is in the form of Z-machine story files. Demand for the ability to create larger game files led Graham Nelson to specify versions 7 and 8 of the Z-machine, though version 7 is very rarely used. Because of the way addresses are handled, a version 3 story file can be up to 128K in length, a version 5 story can be up to 256K in length, and a version 8 story can be up to 512k in length. Though these sizes may seem small by today's computing standards, for text-only adventures, these are large enough for very elaborate games.

During the 1990s, Graham Nelson drew up a Z-Machine Standard, based on detailed studies of the existing Infocom files.

Interpreters

Interpreters for Z-code files are available on a wide variety of platforms. The Inform website lists links to freely available interpreters for 15 desktop operating systems (including 8-bit microcomputers from the 1980s such as the Apple II, TRS-80 and ZX Spectrum, and grouping "Unix" and "Windows" as one each), 10 mobile operating systems (including Palm OS and the Game Boy), and three interpreter platforms (Emacs, Java and JavaScript). According to Graham Nelson, it is "possibly the most portable virtual machine ever created".[2]

Popular interpreters include Nitfol and Frotz. Nitfol makes use of the Glk API, and supports versions 1 through 8 of the Z-machine, including the version 6 graphical Z-machine. Save files are stored in the standard Quetzal save format. Binary files are currently available for several different operating systems, including Macintosh, Linux, DOS, and Windows.[3]

Another popular client for the Mac (OS X) is Zoom. It also supports the same Quetzal save-format, but the packaging of the file-structure is different.[4]

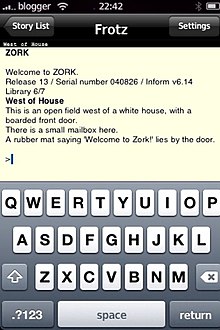

Frotz

Frotz was originally written in C by Stefan Jokisch in 1995 for DOS. Over time it was ported to other platforms, such as Unix, RISC OS, Mac OS and most recently iOS.[5]

Sound effects and graphics were supported to varying degrees. By 2002, development stalled and the program was picked up by David Griffith. The codebase was then distinctly split between the virtual machine and the user interface portions in such a way that the virtual machine became entirely independent from any user interface. This allowed much more variety in porting Frotz. One of the stranger ports is also one of the simplest: an instant messenger bot is wrapped around a version of Frotz with the bare minimum of IO functionality creating a bot with which one can play most Z-machine games using an instant messenger client.[6]

Other utilities

ZorkTools is a collection of utility programs which provide capabilities not normally available for Z-code story files, such as listing all objects or vocabulary words.[7]

See also

- Glulx - Similar to the Z-machine, but relieves several legacy limitations.

- SCUMM - Script Creation Utility for Maniac Mansion by LucasArts, a graphical system similar to Z-machine

- Inform - Similar to the Z-machine, but follows a English-as-code philosophy.

- TADS - Like Glulx, made to address some of its limitations.

References

- ^ "Inside the Industry: Infocom's West Coast Move Stirs Controversy", Computer Gaming World, p. 10, September 1989

- ^ Nelson, Graham. "About Interpreters". Inform website. Retrieved 2009-11-07.

- ^ "if-archive/infocom/interpreters/nitfol". Retrieved 2016-10-29.

- ^ "Logical Shift Zoom". Retrieved 2016-10-29.

- ^ "Frotz README file on Github". Retrieved 2016-10-29.

- ^ "Frotz DUMB file on Github". Retrieved 2016-10-29.

- ^ http://www.ibiblio.org/pub/docs/interactive-fiction/infocom/tools/zt.zip. Retrieved April 22, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)[dead link]

External links

- The Z-Machine standards document

- Learning ZIL (PDF) is the Infocom ZIL manual, dated 1989.

- Description of ZIP (PDF) the Z-Language Interpreter Program (Infocom Internal Document), dated 3/23/89.

- Interpreters for numerous platforms

- How to Fit a Large Program Into a Small Machine describes the creation and design of the Z-machine.