Genghis Khan

This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. (June 2007) |

| Genghis Khan | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Khagan of Mongol Empire ("Khan of the Mongols") | |||||

| |||||

| Reign | 1206 – 18 August, 1227 | ||||

| Coronation | 1206 during khurultai at Khentii Province, Mongolia | ||||

| Predecessor | (title created) | ||||

| Successor | Ögedei Khan | ||||

| Burial | (unknown) | ||||

| Issue | Jochi Chagatai Ögedei Tolui others | ||||

| |||||

| House | Borjigin | ||||

| Father | Yesükhei | ||||

| Mother | Ho'elun | ||||

ⓘ (IPA: [ʧiŋgɪs χaːŋ]; Mongolian: Чингис Хаан; classic Mongolian: ![]() (see below for alternative spellings); ca. 1162[1]–August 18, 1227) was a Mongol Khan (ruler) and posthumously Khagan (emperor[2]) of the Mongol Empire, an empire he founded in 1206. Born with the name Temüjin (Mongolian: Тэмүжин) into the Borjigin clan, he united the Central Asian tribes and founded the Mongol Empire (1206–1368), the largest contiguous and second largest overall empire in world history.

(see below for alternative spellings); ca. 1162[1]–August 18, 1227) was a Mongol Khan (ruler) and posthumously Khagan (emperor[2]) of the Mongol Empire, an empire he founded in 1206. Born with the name Temüjin (Mongolian: Тэмүжин) into the Borjigin clan, he united the Central Asian tribes and founded the Mongol Empire (1206–1368), the largest contiguous and second largest overall empire in world history.

Genghis Khan is a legendary and highly regarded figure in Mongolia, where he is seen as the father of the Mongol nation. On the other hand, he and his successors are responsible for wars of military aggression, conquest, ruthless destruction, and the death of tens of millions of people. As a result, in many areas of southwestern Asia, the Middle East, and Europe, he is seen as a ruthless and bloodthirsty conqueror.[3]

Before becoming a Khan, Temüjin united many of the nomadic tribes of north-east Asia and Central Asia under a new social identity as the "Mongols." Starting with the invasion of western Xia and Jin Dynasty in northern China and consolidating through numerous conquests including the Khwarezmid Empire in Persia, Mongol rule across the Eurasian landmass radically altered the demography and geopolitics of these areas. The Mongol Empire ended up ruling, or at least briefly conquering and/or invading large parts of East Asia, Central Asia, Northern Asia, Middle East and Eastern Europe and attacking places as far as Central Europe and Southeast Asia.

Genghis Khan died in 1227 by uncertain reasons. His sons and grandsons controlled the empire after his death and it grew and endured for over 150 years.

Early life

Birth

There is very little factual information about the earlier life of Temüjin and the few sources providing insight into this period do not know nor agree on some basic facts.

Temüjin was born around 1162 in a Mongol tribe near Khentii Province near the Burhan Haldun mountain range, not far from the current capital of Mongolia, Ulaanbaatar, near the Onon and the Kherlen Rivers. The Secret History of the Mongols states that Temüjin was born with a blood clot in his fist, an indication in the traditional Mongolian folklore that he was destined to become a great leader. Temüjin was the eldest son of Yesükhei, a minor tribal chief of the Kiyad and a nöker (vassal) of Ong Khan of the Kerait tribe,[4] and was, again according to the Secret History, named after a Tartar chieftain that his father had just captured. The name also suggests that they may have descended from a family of blacksmiths (see section Name and title below).

Yesükhei's clan was called Borjigin (Боржигин), and Temüjin's mother, Hoelun, was from the Olkhunut tribe of the Mongol confederation. Like other tribes, they were nomads.

Because his father was a chieftain, as were his predecessors, Temüjin was of a royal or noble background. This relative higher social standing made it easier for him to ask help from others.

Family and lineage

Temüjin was related on his father's side to Qabul Khan, Ambaghai and Qutula Khan who had headed the Mongol confederation under the Jin Dynasty until the Jin switched support to the Tatars in 1161 and destroyed Qabul Khan.[5] Genghis' father, Yesükhei (leader of the Borjigin and nephew to Ambaghai and Qutula Khan) emerged as the head of the ruling clan of the Mongols, but this position was contested by the rival Tayichi’ud clan, who descended directly from Ambaghai. When the Tatars, in turn, grew too powerful after 1161, the Jin moved their support from the Tatars to the Kerait.

Childhood and personal life

Temüjin had three brothers, Khasar (or Qasar), Khajiun, and Temüge, and one sister, Temülen (or Temülin), as well as two half--brothers, Bekhter and Belgutei.

Temüjin's first wife Börte had four sons, Jochi (1185–1226), Chagatai (?—1241), Ögedei (?—1241), and Tolui (1190–1232). Genghis Khan also had many other children with his other wives, but they were excluded from the succession, and records on what daughters he may have had are nonexistent. The paternity of Genghis Khan's eldest son, Jochi, remains unclear to this day and was a serious point of contention in his lifetime. Soon after Börte's marriage to Temüjin, she was kidnapped by the Merkits and reportedly given to one of their men as a wife. Though she was rescued, she gave birth to Jochi nine months later, clouding the issue of his parentage.

According to traditional historical accounts, this uncertainty over Jochi's true father was voiced most strongly by Chagatai. In The Secret History of the Mongols, just before the invasion of the Khwarezmid Empire by Genghis Khan, Chagatai declares before his father and brothers that he would never accept Jochi as Genghis Khan's successor. In response to this tension[6] and possibly for other reasons, it was Ögedei who was appointed as successor and who ruled as Khagan after Genghis Khan's death. Jochi died in 1226, during his father's lifetime.[7]

According to our sources, Temüjin's early life was difficult. When he was only 9, as part of the marriage arrangement, his father Yesükhei delivered Temüjin to the family of his future wife Börte, members of the Onggirat tribe. He was to live there in service to Deisechen, the head of the household, until he reached the marriageable age of 12. He grew up in a tough political climate because of habitual tribal warfare, thievery, raids and revenges between the confederations and also from foreign forces and influences. None of the confederations were under a single political control, except the Chinese dynasties to the south.

While heading home, his father was poisoned when having a meal with the neighbouring Tatars, who are portrayed as having long been enemies of the Mongols. Thus, Temüjin had to return home and make the claim to the position of clan's chief. But his father's clan refused to be led by a boy and soon abandoned him and his family including his mother Hoelun leaving them without protection.

For the next several years, Temüjin and his family lived in poverty, surviving primarily on wild fruits, marmots and other small game hunted by Temüjin and his brothers. In one of these hunting incidents, 13 year old Temüjin murdered his half-brother Bekhter over a dispute over hunting spoils.[8] This incident cemented his position as head of the household. His mother, Hoelun, taught him many lessons about survival in the harsh landscape and even grimmer political climate of Mongolia, especially the need for alliances with others, a lesson which would shape his understanding in his later years.

In another incident in 1182 he was captured in a raid by his father's former allies, the Ta'yichiut, and was held captive. The Ta'yichiut enslaved Temüjin (reportedly with a cangue), but he escaped with help from a sympathetic watcher, the father of Chilaun (who would later became general of Genghis Khan), by escaping from the ger that he was held and by hiding in crevice in a river. Around this time Jelme and Bo'orchu, two of Genghis Khan's future generals joined him. Along with his brothers, they provided the manpower needed for early expansion and diplomacy. Also around this time the name of Temüjin became relatively widespread for his bravery and outgoing attitude especially after his escape from the Ta'yichiut.

As previously arranged by his father, Temüjin married Börte of the Konkirat tribe around when he was 16 in order to forge tribal alliances with her tribe. However, Borte was later kidnapped in one of the raids by the Merkit tribe, and Temüjin rescued her with the help of his friend and future rival, Jamuqa, and his protector, Ong Khan of the Kerait tribe. Borte would be his only empress, although he followed tradition by taking several morganatic wives. Temüjin became blood brother (anda) with Jamuqa, and thus the two made a vow to be faithful to each other for eternity.

Uniting the confederations

The Central Asian plateau (north of China) around the time of Temüjin was divided into several tribes or confederations, among them Naimans, Merkits, Uyghurs, Tatars, Mongols, Keraits that were all prominent in their own right and often unfriendly toward each other as evidenced by random raids, revenges, and plundering.

Temüjin began his slow ascent to power by offering himself as an ally (or, according to others sources, a vassal) to his father's anda (sworn brother or blood brother) Toghrul, who was Khan of the Kerait, and is better known by the Chinese title Ong Khan (or "Wang Khan"), which the Jin Empire granted him in 1197. This relationship was first reinforced when Börte was captured by the Merkits; it was to Toghrul that Temüjin turned for support. In response, Toghrul offered his vassal 20,000 of his Kerait warriors and suggested that he also involve his childhood friend Jamuqa, who had himself become Khan (ruler) of his own tribe, the Jadaran.[9] Although the campaign was successful and led to the recapture of Börte and utter defeat of the Merkits, it also paved the way for the split between the childhood friends, Temüjin and Jamuqa.

The main opponents of the Mongol confederation (traditionally the "Mongols") circa 1200 were the Naimans to the west, the Merkits to the north, Tanguts to the south, the Jin and Tatars to the east. By 1190, Temüjin, his followers and advisors united the smaller Mongol confederation only. As an incentive for absolute obedience and following his rule of law, the Yassa code, Temüjin promised civilians and soldiers a wealth from future possible war spoils.

Toghrul's (Wang Khan) son Senggum was jealous of Temüjin's growing power and his affinity with his father and because of that he allegedly planned to assassinate Temüjin. Toghrul, though allegedly saved on multiple occasions by Temüjin, gave in to his son[10] and adopted an obstinate attitude towards collaboration with Temüjin thereafter. Temüjin learned of Senggum's intentions and eventually defeated him and his loyalists. One of the later ruptures between Toghrul and Temüjin was Toghrul's refusal to give his daughter in marriage to Jochi, the eldest son of Temüjin, which signified disrespect in the Mongolian culture. This act probably led to the split between both factions and a prelude to war. Toghrul allied himself with Jamuqa, Temüjin's blood brother, or anda that already opposed Temüjin's forces; however the internal dispute between Toghrul and Jamuqa, plus the desertion of a number of their allies to Temüjin, led to Toghrul's defeat. In the meantime Jamuqa managed to escape. This defeat was a catalyst for the fall and eventual dissemination of the Kerait tribe.

The next direct threat to Temüjin was the Naimans (Naiman Mongols), with whom Jamuqa and his followers took refuge. The Naimans did not surrender, although enough sectors again voluntarily sided with Temüjin. In 1201, a kurultai elected Jamuqa as Gur Khan, universal ruler, a title used by the rulers of the Kara-Khitan Khanate. Jamuqa's assumption of this title was the final breach with Temüjin, and Jamuqa formed a coalition of tribes to oppose him. Before the conflict, however, several generals abandoned Jamuqa, including Subutai, Jelme's well-known younger brother. After several battles, Jamuqa was finally turned over to Temüjin by his own men in 1206.

According to the Secret History, Temüjin generously offered his friendship again to Jamuqa and asked him to turn to his side. Jamuqa refused and asked for a noble death as in custom, that is, without spilling blood, which was granted by breaking his back. The rest of the Merkit clan that sided with the Naimans were defeated by Subutai, a member of Temüjin's personal guard who would later become one of the successful commanders of Genghis Khan. The Naimans' defeat left Genghis Khan as the sole ruler of the Mongol plains, which means all the prominent confederations fell and/or united under Temüjin's Mongol confederation.

As a result by 1206 Temüjin had managed to unite the Merkits, Naimans, Mongols, Uyghurs, Keraits, Tatars and disparate other smaller tribes under his rule. It was a monumental feat for the "Mongols" (as they became known collectively), who had a long history of internecine dispute, economic hardship, and pressure from Chinese dynasties and empires. At a Kurultai, a council of Mongol chiefs, he was acknowledged as "Khan" of the consolidated tribes and took the new title Genghis Khan. The title Khagan was not conferred on Genghis until after his death, when his son and successor, Ögedei took the title for himself and extended it posthumously to his father (as he was also to be posthumously declared the founder of the Yuan Dynasty). This unification of all confederations by Genghis Khan established peace between previously warring tribes and a single political and military force under Genghis Khan.

Expansion and military campaigns

Conquest of the Western Xia Dynasty

During the 1206 political rise for Genghis Khan, the Mongol nation or Mongol Empire created by Genghis Khan and his allies was neighboured to the west by the Tanguts' Western Xia Dynasty. To its east and south was the Jin Dynasty, founded by the Manchurian Jurchens, who ruled northern China as well as being the traditional overlord of the Mongolian tribes for centuries.

Temüjin organised his people, army, and his state to prepare for war with Western Xia, or Xi Xia, which was closer to the Mongolian lands. He correctly believed that the Jin Dynasty had a young ruler who would not come to the aid of Xi Xia: when the Tanguts requested help from the Jin Dynasty, they were refused.[11] On the other hand, the Jurchens had also probably grown uncomfortable with the newly unified Mongols, whom they traditionally fought against and had uncomfortable relationships with. It may be that some trade routes ran through Mongol territory, and they might have feared the Mongols eventually would restrict the supply of goods coming from the Silk Road. Genghis Khan and his supporters were also eager to take revenge against the Jurchen for their long subjugation of the Mongols by stirring up conflicts between Mongol tribes and also possibly for material gains and plunder. For instance, the Jurchen had executed some Mongol Khans in the past. Genghis Khan also probably wanted to keep his troop agile and with purpose and, in the meantime, keep himself in power. Genghis Khan led his army against Western Xia and conquered it, despite initial difficulties in capturing its well-defended cities. By 1209, Western Xia acknowledged Genghis as overlord.

Defeat of the Jin Dynasty

After the conquest of Western Xia, in 1211 Genghis Khan planned again to conquer the Jin Dynasty, Western Xia's southern neighbour. The commander of the Jin Dynasty army made a tactical mistake in not attacking the Mongols at the first opportunity. Instead, the Jin commander sent a messenger, Ming-Tan, to the Mongol side, who promptly defected and told the Mongols that the Jin army was waiting on the other side of the pass. At this engagement fought at Badger Pass the Mongols massacred thousands of Jin troops. In 1215 Genghis besieged, captured, and sacked the Jin capital of Yanjing (later known as Beijing). This forced the Jin Emperor Xuanzong to move his capital south to Kaifeng. These two main conquests were the subjugation of the Western Xia and Jin dynasties.

Conquest of the Kara-Khitan Khanate

Meanwhile, Kuchlug, the deposed Khaj of the Naiman confederation that Temüjin defeated or united, had fled west and usurped the khanate of Kara-Khitan (also known as Kara Kitay). Genghis Khan decided to conquer the Kara-Khitan khanate and defeat Kuchlug possibly to take him out of power. By this time the Mongol army was exhausted from ten years of continuous campaigning in China against the Western Xia and Jin Dynasty. Therefore, Genghis sent only two tumen (20,000 soldiers) against Kuchlug, under his younger general, Jebe, known as "The Arrow".

The strategy of the Mongols was to incite internal revolt in Kuchlug's supporters, leaving the Khara-Khitan khanate more vulnurable to Mongol conquest. As a result Kuchlug's army was defeated in west of Kashgar; however Kuchlug fled again, but was hunted down by Jebe's army and executed. By 1218 as a result of defeat of Kara-Khitan khanate, the Mongol Empire and its control extended as far west as Lake Balkhash, which bordered the Khwarezmia (Khwarezmid Empire), a Muslim state that reached the Caspian Sea to the west and Persian Gulf and the Arabian Sea to the south. These Genghis Khan's invasions probably got the attention of Khwarezmid Empire among others.

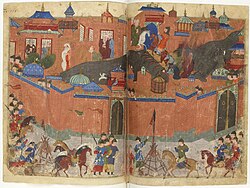

Invasion of Khwarezmid Empire

When Kara-Khitan khanate was defeated by Genghis Khan, it was bordered with the Khwarezmid Empire that was governed by Shah Ala ad-Din Muhammad. Genghis Khan saw the potential advantage in Khwarezmia (as it is also referenced) as a commercial trading partner, and sent a 500-man caravan to establish trade ties with the empire. However, Inalchuq, the governor of the Khwarezmian city of Otrar, attacked the caravan that came from Mongolia, claiming that the caravan was a conspiracy against Khwarezmia. He probably feared the Mongols after their victory over Western Xia, Jin Dynasty and the latest Kara-Kitan khanate. The situation became more complicated as the governor later refused to make repayments for the looting of the caravan and murder of its members. Genghis Khan then sent again a second group of ambassadors to meet the Shah himself. The Shah had all the men shaved and all but one beheaded. This was seen as an affront and insult to Genghis Khan. Outraged Genghis Khan planned one of his largest campaigns by organising together around 200,000 soldiers (20 tumens), his most capable generals and some of his sons to attack the Khwarezmian Dynasty for their actions.

The Mongol army under command of Genghis Khan, generals and son(s) crossed the Tien Shan mountains by entering the area controlled by the Khwarezmid Empire. After compiling intelligence from many sources Genghis Khan carefully prepared his army, which was divided into three groups. His son Jochi led the first division into the northeast of Khwarezmia. The second division under Jebe marched secretly to the southeast part of Khwarzemia to form, with the first division, a pincer attack on Samarkand. The third division under Genghis Khan and Tolui marched to the northwest and attacked Khwarzemia from that direction.

The Shah's army was split by diverse internal disquisitions and by the Shah's decision to divide his army into small groups concentrated in various cities — this fragmentation was decisive in Khwarezmia's defeats. Tired and exhausted from the journey, the Mongols still won their first victory against the Khwarezmian army. The Mongol army quickly seized the town of Otrar, relying on superior strategy and tactics. Once he had conquered the city, Genghis Khan executed many of the inhabitants and executed Inalchuq by pouring molten silver into his ears and eyes, as retribution for his actions. Also the Shah's fearful attitude towards the Mongol army also did not help his army. Near the end of the battle the Shah fled rather than surrender. Genghis Khan charged Subutai and Jebe with hunting him down, giving them two years and 20,000 men. The Shah died under mysterious circumstances on a small island within his empire.

According to stories, Genghis Khan diverted a river of Ala ad-Din Muhammad II of Khwarezm's birthplace, erasing it from the map. The Mongols' conquest was relatively brutal like their other battles by killing of both civilians and soldiers, plundering, pillaging, raping and possibly arson. However after the capital Samarkand fell, the capital was moved to Bukhara by the remaining men and Genghis Khan was dedicated to completely destroy the remnants of the Khwarezmid Empire by sending his army and two generals to destroy them. The heir Shah Jalal Al-Din and a brilliant strategist, who was supported enough by the town, battled the Mongols several times with his father's armies. However, internal disputes once again split his forces apart, and Khwarezmid Empire was forced again to flee Bukhara after a devastating defeat. This essentially was the complete defeat of the Khwarezmid Empire at the hands of Genghis Khan.

In the meantime, Genghis Khan selected his third son Ögedei as his successor before his army was set out, and specified that subsequent Khans should be his direct descendants. Genghis Khan also left Muqali, one of his most trusted generals, as the supreme commander of all Mongol forces in Jin China while he was out battling the Khwarezmid Empire to the west.

Attacks on Georgia and Volga Bulgaria

After the complete and effectual defeat of the Khwarezmid Empire, the Mongol army was split into two component forces (armies). Genghis Khan led a division on a raid through Afghanistan, Pakistan and northern India, while another contingent, led by his generals Jebe and Subutai, marched through the Caucasus and Russia. The army under Genghis Khan was heading home to Mongolia. While Genghis Khan gathered his forces in Persia and Armenia to essentially head back home, the second component force of 20,000 troops (two tumen), commanded by Jebe and Subutai, pushed deep into Armenia and Azerbaijan. The Mongols destroyed Georgia, sacked the Genoese trade-fortress of Caffa in Crimea, and stayed over winter near the Black Sea. Heading home Subutai's forces attacked the Kipchaks and were intercepted by the allied troops of Mstislav the Bold of Halych and Mstislav III of Kiev, along with about 80,000 Kievan Rus' to stop their actions. Subutai sent emissaries to the Slavic princes calling for separate peace, but the emissaries were executed. At the Battle of Kalka River in 1223, the Subutai's component forces defeated the larger Kievan force. Subotai's army lost to Volga Bulgars in the first attempt in 1223,[12] though they returned to avenge their defeat by subjugating all Volga Bulgaria under the Khanate Golden Horde. The Mongols learned from captives of the abundant green pastures beyond the Bulgar territory, allowing for the planning for conquest of Hungary and Europe. The Russian princes then sued for peace. Subutai agreed but was in no mood to pardon the princes. As was customary in Mongol society for nobility, the Russian princes were given a bloodless death. Subutai had a large wooden platform constructed on which he ate his meals along with his other generals. Six Russian princes, including Mstislav of Kiev, were put under this platform and they were crushed to death.

Genghis Khan recalled Subutai back to Mongolia soon afterwards, and Jebe died on the road back to Samarkand. This famous cavalry expedition of Subutai and Jebe, in which they encircled the entire Caspian Sea defeating every single army in their path, remains unparalleled to this day and showed the actions of more victorious Mongols. Word started to go out to other nations, particularly in Europe about the actions of Mongols.

These two campaigns are generally regarded as reconnaissance campaigns that tried to get the feel of the political and cultural elements of the regions. In 1225 both divisions returned to Mongolia. These invasions ultimately added Transoxiana and Persia to an already formidable empire while destroying any resistance along the way.

Second war with the Western Xia and Jin Dynasty coalition

While most Mongol forces under Genghis Khan and his generals were out on campaign against the Khwarezmid Empire, the previously defeated or surrendered Western Xia and Jin Dynasty formed a coalition to resist the Mongols. Also the vassal emperor of the Tanguts (Western Xia) had refused to take part in the war against the Khwarezmid Empire. Because of this Genghis Khan again prepared for war against both Western Xia and Jin Dynasty. In 1226, Genghis Khan began to attack the Tanguts. In February, he took Heisui, Ganzhou and Suzhou, and in the autumn he took Xiliang-fu. One of the Tangut generals challenged the Mongols to a battle near Helanshan (Helan means "great horse" in the northern dialect, shan means "mountain"). The Tangut armies were soundly defeated. In November, Genghis laid siege to the Tangut city Lingzhou, and crossed the Yellow River and defeated the Tangut relief army. Genghis Khan reportedly saw a line of five stars arranged in the sky, and interpreted it as an omen of his victory. In 1227, Genghis Khan attacked and destroyed the Tangut capital of Ning Hia, and continued to advance, seizing Lintiao-fu in February, Xining province and Xindu-fu in March, and Deshun province in April. At Deshun, the Tangut general Ma Jianlong put up a fierce resistance for several days and personally led charges against the invaders outside the city gate. Ma Jianlong later died from wounds received from arrows in battle. Genghis Khan, after conquering Deshun, went to Liupanshan (Qingshui County, Gansu Province) to escape the severe summer. The new Tangut emperor quickly surrendered to the Mongols. The Tanguts officially surrendered in 1227, after having ruled for 187 years, beginning in 1038. Not happy with their betrayal and resistance, Genghis Khan ordered the imperial family to be executed. By this time Genghis Khan was not a young man anymore and his advancing age had led him to make preparations for his death.

In general the Mongol Empire campaigned six times against the Tanguts in 1202, 1207, 1209–1210, 1211–1213, 1214–1219 and 1225–1226 and this was one of them.

Death and burial

On August 18, 1227, during his last campaign against the coalition of Jin Dynasty and Western Xia, Genghis Khan died. The reason for his death is uncertain. The speculations for his death are that he fell off his horse, due to old age and physical fatigue; some contemporary observers cited prophecies from his opponents. The Galician-Volhynian Chronicle alleges he was killed by the Tanguts. There are persistent folktales that a Tangut princess, to avenge her people and prevent her rape, castrated him with a knife hidden inside her and that he never recovered.

Genghis Khan asked to be buried without markings. After he died, his body was returned to Mongolia and presumably to his birthplace in Khentii Aimag, where many assume he is buried somewhere close to the Onon River and the Burkhan Khaldun mountain (part of the Kentii mountain range). According to legend, the funeral escort killed anyone and anything across their path to conceal where he was finally buried. The Genghis Khan Mausoleum is his memorial, but not his burial site.

On October 6, 2004, "Genghis Khan's palace" was allegedly discovered and that may make it possible to find his burial site. Folklore says that a river was diverted over his grave to make it impossible to find (the same manner of burial of Sumerian King Gilgamesh of Uruk.) Other tales state that his grave was stampeded over by many horses, over which trees were then planted, and the permafrost also did its bit in hiding the burial site. The burial site remains undiscovered.

Genghis Khan left behind an army of more than 129,000 men; 28,000 were given to his various brothers and his sons. Tolui, his youngest son, inherited more than 100,000 men. This force contained the bulk of the elite Mongolian cavalry. By tradition, the youngest son inherits his father's property. Jochi, Chagatai, Ögedei Khan, and Kulan's son Gelejian received armies of 4,000 men each. His mother and the descendants of his three brothers received 3,000 men each.

Mongol Empire

Politics and economics

The Mongol Empire was governed by civilian and military code, called the Yassa code created by Genghis Khan.

Among nomads, the Mongol Empire did not emphasize the importance of ethnicity and race in the administrative realm, instead adopting an approach grounded in meritocracy. The exception was the role of Genghis Khan and his family. The Mongol Empire was one of the most ethnically and culturally diverse empires in history, as befitted its size. Many of the empire's nomadic inhabitants considered themselves Mongols in military and civilian life, including Turks, Mongols, and others and included many diverse Khans of various ethnicities as part of the Mongol Empire such as Muhammad Khan.

There were tax exemptions for religious figures and so to some extent teachers and doctors. The Mongol Empire practiced religious tolerance to a large degree because it was generally indifferent to belief. The exception was when religious groups challenged the state. For example Ismaili Muslims that resisted the Mongols were exterminated.

It is claimed that the Mongol Empire linked together the previously fractured Silk Road states under one system and became somewhat open to trade and cultural exchange. However, the Mongol conquests did lead to a collapse of many of the ancient trading cities of Central Asia that resisted invasion. Taxes were also heavy and conquered people were used as forced labour in those regions.

Modern Mongolian historians say that towards the end of his life, Genghis Khan attempted to create a civil state under the Great Yassa that would have established the legal equality of all individuals, including women [1]. However, there is no contemporary evidence of this, or of the lifting of discriminatory policies towards sedentary peoples such as the Chinese. Women played a relatively important role in Mongol Empire and in family, for example Torogene Khatun was briefly in charge of the Mongol Empire when next male Khagan was being chosen. Modern scholars refer to the alleged policy of encouraging trade and communication as the Pax Mongolica (Mongol Peace).

Genghis Khan realized that he needed people who could govern cities and states conquered by him. He also realised that such administrators could not be found among his Mongol people because they were nomads and thus had no experience governing cities. For this purpose Genghis Khan invited a Khitan prince, Chu'Tsai, who worked for the Jin and had been captured by Mongol army after the Jin Dynasty were defeated. Jin had captured power by displacing Khitan. Genghis told Chu'Tsai, who was a lineal descendant of Khitan rulers, that he had avenged Chu'Tsai's forefathers. Chu'Tsai responded that his father served the Jin Dynasty honestly and so did he; he did not consider his own father his enemy, so the question of revenge did not apply. Genghis Khan was very impressed by this reply. Chu'Tsai administered parts of the Mongol Empire and became a confidant of the successive Mongol Khans.

Military

The Mongol military was one of the most feared and ruthless armies discussed by many historians, chroniclers and writers of the time. For instance, a person with firsthand experience of the Mongol army's attack said:

For our sins, unknown nations arrived. No one knew their origin or whence they came, or what religion they practiced. That is known only to God, and perhaps to wise men learned in books...These terrible strangers have taken our country, and tomorrow they will take yours if you do not come and help us.

It is widely regarded that Mongol armies were more victorious during the time than other armies by defeating resistances that they found along the way in Central Asia, China, Georgia, Armenia, Rus', Baghdad, Korea, Syria, etc. (see Mongol invasions) before they were defeated and stopped at the Battle of Ayn Jalut. This doesn't mean they weren't defeated at all throughout their existence, but they won most and decisive battles during their prime time particurly against China, East Europe and Middle East. Genghis Khan is widely cited as producing a highly efficient army with remarkable discipline, organization, toughness, dedication, loyalty and military intelligence, in comparison to their enemies. Operating in massive sweeps, extending over dozens of miles, the Mongol army combined shock, mobility and firepower unmatched in land warfare until the modern age. Originally consisting of purely cavalry units, the Mongols learned and absorbed the war technology and strategies of the empires and kingdoms they invaded and conquered. Most notable contribution in their military campaigns was the absorption of Chinese siege warfare and engineers; prior to this the Mongols lacked skills to take walled cities. The Mongol cavalry was more used to the open-space steppe warfare. With the introduction of siege warfare and fighting ships from both China and Korea, the Mongol capability was enhanced greatly.

Organization and background

In contrast to most of their enemies, almost all Mongols were nomads and had experience in riding and managing horses from a very young age. Mongol military structure was based largely on meritocracy. For example if a Khan was not fit for military command, the troops would be led by someone with more experience and victories, for example Subutai. Genghis refused to divide his troops into different units based on ethnicity, instead he mixed tribesmen from conquered groups, like the Tatars and Keraits, which fostered a sense of unity and loyalty by reducing the effects of the old tribal affiliations and preventing any one unit from developing a separate ethnic or national character. Discipline was strictly maintained, with severe punishments provided for even small infractions. The armies were also divided based on the traditional Inner Asian decimal system in units of 10 (arban), 100 (jaghun), 1,000 (mingghan), and 10,000 (tumen) men.[13] They were extremely ruthless when in battle based on others' standards (see below). These units of 10s were like a family or close-knit group, every unit of 10 had a leader who reported up to the next level, and men were not allowed to transfer from one unit to another . Discipline was severe: if one member of an arban deserted, all the arban were executed; if the whole arban deserted, the entire jaghun would be executed. Leaders of the tumens were mostly Mongol nobility, or those who had been granted noble status, while the leader of the 100,000 (leader of 10 tumens) was the Khagan himself. The soldiers always took their families with them for battle, such that Hazara people of Afghanistan claim to be Mongol people that moved from Mongolia for campaign back in the day.

Mongols in general were very used to living through cold, harsh winters, in fact often preferring to campaign in winter in order to facilitate river crossings, and they were used to travelling great distances in very short time without difficulty, since their nomadic lifestyle already involved bi-annual migrations from summer to winter pastures. For instance, the journey from Mongolia to the Caspian sea was considered a hundred days' ride for the army.

Genghis Khan expected unwavering loyalty from his generals, and granted them a great deal of autonomy in making command decisions. Muqali, a trusted general, was given command of the Mongol forces against the Jin Dynasty while Genghis Khan was fighting in Central Asia, and Subutai and Jebe were allowed to pursue the Great Raid into the Caucausus and Kievan Rus, an idea they had presented to the Khagan on their own initiative. The Mongol military also was successful in siege warfare, cutting off resources for cities and towns by diverting certain rivers, taking enemy prisoners and driving them in front of the army, and adopting new ideas, techniques and tools from the people they conquered, particularly in employing Muslim and Chinese siege engines and engineers to aid the Mongol cavalry in capturing cities. Also one of the standard tactics of Mongol military was the commonly practiced feigned retreat to break enemy formations and to lure small enemy groups away from larger group and defended position for ambush and counterattack.

Another important aspect of the military organization of Genghis Khan was the communications and supply route or Yam, adapted from previous Chinese models. Genghis Khan dedicated special attention to this in order to speed up the gathering of military intelligence and official communications. To this end, Yam waystations were established all over the empire.

Division of the Empire into Khanates

Before his death, Genghis Khan divided his empire among his sons Ögedei, Chagatai, Tolui, and Jochi (Jochi's death several months before Genghis Khan meant that his lands were instead split between his sons, Batu and Orda) into several Khanates designed as sub-territories: their Khans were expected to follow the Great Khan, who was, initially, Ögedei.

Following are the Khanates in the way in which Genghis Khan assigned after his death:

- Empire of the Great Khan - Ögedei Khan, as Great Khan, took most of Eastern Asia, including China; this territory later to comprise the Yuan Dynasty under Kubilai Khan.

- Mongol homeland (present day Mongolia, including Karakorum) - Tolui Khan, being the youngest son, received a small territory near the Mongol homeland, following Mongol custom.

- Chagatai Khanate - Chagatai Khan, Genghis Khan's second son, was given Central Asia and northern Iran.

- Blue Horde - Batu Khan, and White Horde - Orda Khan, both were later combined into the Kipchak Khanate, or Khanate of the Golden Horde, under Toqtamysh. Genghis Khan's eldest son, Jochi, had received most of the distant Russia and Ruthenia. Because Jochi died before Genghis Khan, his territory was further split up between his sons. Batu Khan launched an invasion of Russia, and later Hungary and Poland, and crushed several armies before being summoned back by the news of Ögedei's death.

In 1256, during the rule of Ögedei, Hulagu Khan, son of Tolui, was charged with the conquest of the Muslim nations to the southwest of the empire. These included modern day Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan, Azerbaijan, Pakistan, and the new khanate was named the Il-Khanate. Since, after Tolui's death and the accession of his descendants to the office of Great Khan, his ulus were merged with the Yuan Dynasty, the Il-Khanate is considered, along with the Yuan Dynasty, Chagatai Khanate, and the Golden Horde, to be one of the four divisions of the Mongol Empire.

After Genghis Khan

Contrary to popular belief, Genghis Khan did not conquer all of the areas of Mongol Empire. At the time of his death, the Mongol Empire stretched from the Caspian Sea to the Sea of Japan. The empire's expansion continued for a generation or more after Genghis's death in 1227. Under Genghis's successor Ögedei Khan the speed of expansion reached its peak. Mongol armies pushed into Persia, finished off the Xi Xia and the remnants of the Khwarezmids, and came into conflict with the imperial Song Dynasty of China, starting a war that would last until 1279 and that would conclude with the Mongols gaining control of all of China.

In the late 1230s, the Mongols under Batu Khan started the Mongol invasions of Europe and Russia, reducing most of their principalities to vassalage, and pressed on into Central Europe. In 1241 Mongols under Subutai and Batu Khan defeated the last Polish-German and Hungarian armies in two days that came in for defense at the Battle of Legnica and the Battle of Mohi.

During the 1250s, Genghis's grandson Hulegu Khan, operating from the Mongol base in Persia, destroyed the Abbasid Caliphate in Baghdad as well as the cult of the Assassins. It was rumoured that cult of the Assassins had sent 400 men to kill the Khagan Mongke Khan. The Khagan made this pre-emptive strike at the heart of the Islamic kingdom to make sure that no such assassination would take place. Hulegu Khan, the commander in chief of this campaign, along with his entire army returned to the main Mongol capital Karakorum when he heard of Khagan Mongke Khan's death and left behind just two tumen of soldiers (20,000). A battle between a Mongol army and the Mamluks ensued in modern-day Palestine. Many in the Mamluk army were Turks who had fought the Mongols years before as free men but were defeated and sold via Italian merchants to the Sultan of Cairo. They shared their experiences and were better prepared for Mongol tactics. The Mongol army lost the Battle of Ayn Jalut near modern-day Nazareth. This was the first defeat of the Mongol Empire in which they did not return to seek battle again.[14]

Mongol armies under Kublai Khan attempted two unsuccessful invasions of Japan in 1274 and 1281 and three unsuccessful invasions of modern-day Vietnam in 1257, 1285 and 1287 AD.

Military destruction and casualties

There are various sources about the amount of destruction Genghis Khan and his armies caused especially among the people who suffered Mongol conquests. The peoples who suffered the most during Genghis Khan's conquests, like the Persians and the Han Chinese usually stress the negative aspects of the Mongol conquests and some modern scholars argue that their historians exaggerate the numbers of deaths and the extent of material destruction; however, such historians produce virtually all the documents available to modern scholars, making it difficult to establish a firm basis for any alternative view; however virtually all sources basically agree on the greater casualty and destruction caused by the Mongol forces.

Casualties

In military strategy, Genghis Khan generally preferred to offer opponents the chance to surrender under his rule without a resistance and become vassals by sending tribute, accepting residents and contributing troops and supply or face certain military assault.

A messenger of Hulagu Khan (grandson of Genghis Khan) delivered a message from him about the invasion of Baghdad that

When I lead my army against Baghdad in anger, whether you hide in heaven or in earth, I will bring you down from the spinning spheres. I will toss you in the air like a lion. I will leave no one alive in your realm. I will burn your city, your land, your self. If you wish to spare yourself and your venerable family, give heed to my advice with the ear of intelligence. If you do not, you will see what God has willed.

He guaranteed the populace a protection only if they abided by the rules set forth and be obedient, but his and his successor leaders' policy was widely written in historical documents as causing mass destruction, terror and deaths if they encountered a resistance. For example David Nicole states in The Mongol Warlords, "terror and mass extermination of anyone opposing them was a well tested Mongol tactic." If the offer was refused the Mongol leaders would not give an alternative choice but would order massive collective slaughter of the population of resisting cities and destruction of their property.

Only the skilled engineers and artists were spared from death and maintained as slaves if they agreed to surrender. Documents written during or just after Genghis Khan's reign say that after a conquest, the Mongol soldiers looted, pillaged and raped while the Khan got the first pick of the beautiful women. Some troops who submitted were incorporated into the Mongol system in order to expand their manpower; this also allowed the Mongols to absorb new technology, manpower, knowledge and skill for use in military campaigns against other possible opponents. These techniques were sometimes used to spread terror and warning to others (see above).

There were also instances of mass slaughter even when there was no resistance, especially in Northern China where the vast majority of the population had a long history of accepting nomadic rulers. Many ancient sources described Genghis Khan's conquests as wholesale destruction on an unprecedented scale in their certain geographical regions, and therefore probably causing great changes in the demographics of Asia. For example, over much of Central Asia speakers of Iranian languages were replaced by speakers of Turkic languages. According to the works of Iranian historian Rashid al-Din, the Mongols killed more than 70,000 people in Merv and more than a million in Nishapur. China reportedly suffered a drastic decline in population during 13th and 14th centuries. Before the Mongol invasion, Chinese dynasties reportedly had approximately 120 million inhabitants; after the conquest was completed in 1279, the 1300 census reported roughly 60 million people. Genghis was known to have killed millions of people in northern China, but precisely how many of these deaths are directly attributable to Genghis Khan and his forces or by other causes is unclear and speculative.[15] About half of the Russian population died during the Mongol invasion of Rus.[16] The total population of Persia may have dropped from 2,500,000 to 250,000 as a result of mass extermination and famine.[17] Historians estimate that up to half of Hungary's two million population at that time were victims of the Mongol invasion.[18]

Property and culture

His campaigns in Northern China, Central Asia and the Middle East caused massive property destruction for those who resisted his invasion according to the regions' historians; however, there are no exact factual numbers available at this time. For example, the cities of Herat, Nishapur, and Samarkand suffered serious devastation by the armies of Genghis Khan.[19][20] There is a noticeable lack of Chinese literature that has survived from the Jin Dynasty, due to the Mongol conquests.

Genghis Khan's practices

Simplicity

It is not entirely clear what Genghis Khan's personality was truly like, as with any historical person without an autobiography. His quotations and historians' documents provide insight into his character. His personality and character were moulded by the many hardships he faced when he was young, and in unifying the Mongol nation, especially dealing with murder of his father at young age and therefore losing tribal protection, kidnapping of his fiance Borte, supporting his mother throughout their abandonment, trying to find ways to unify the people and betrayals from his allies particularly Jamuqa, Toghrul, etc. Genghis Khan fully embraced the Mongol people's nomadic way of life according to his quotes and did not try to change their customs or beliefs. As he aged, he seemed to become increasingly aware of the consequences of numerous victories and expansion of the Mongol Empire, including the possibility that succeeding generations might choose to live a sedentary lifestyle. According to quotations attributed to him in his later years, he urged future leaders to follow the Yasa, and to refrain from surrounding themselves with wealth and pleasure. He was known to share his wealth with his people and awarded subjects handsomely who participated in campaigns in the book The Secret History of the Mongols.

Honesty and loyalty

Genghis Khan seemed to value honesty and loyalty to himself highly from his subjects. Genghis Khan put some trust in his generals, such as Muqali, Jebe and Subudei, and gave them free rein in battles. He allowed them to make decisions on their own when they embarked on campaigns on their own very far from the Mongol Empire capital Karakorum. An example of Genghis Khan's perception of loyalty is written in The Secret History of the Mongols that one of his main military generals Jebe had been his enemy and shot his horse. When Jebe was captured, he said he shot his horse and that he would fight for him if he spared his life or would die if that's what he wished. Genghis Khan spared Jebe's life, Jebe betrayed his former commander, and he became one of the powerful, successful generals of Genghis Khan.

Yet, accounts of Genghis Khan's life are marked by claims of a series of betrayals and conspiracies. These include rifts with his early allies such as Jamuqa (who also wanted to be a ruler of Mongol tribes) and Wang Khan (his and his father's ally), his son Jochi, and problems with the most important Shaman who was allegedly trying break him up with brother Qasar who was serving Genghis Khan loyally. Many modern scholars doubt that all of the conspiracies existed and suggest that Genghis Khan was probably inclined towards paranoia as a result of his experiences.[citation needed]

Military strategy

His military strategies showed a deep interest in gathering good intelligence and understanding the motivations of his rivals as exemplified by his extensive spy network and Yam route systems. He seemed to be a quick student, adopting new technologies and ideas that he encountered, such as siege warfare from the Chinese. The book Secret History makes it clear he was not physically courageous and even says he was afraid of dogs. Many legends claim that Genghis Khan always was in the front in battles, but these may not be historically accurate.

Spirituality

Genghis Khan's religion is widely speculated to be Shamanism, which was very likely among nomadic Mongol-Turkic tribes of Central Asia. Genghis Khan towards the later part of his life became interested in the ancient Buddhism and Taoism religion from China. The Taoist monk Ch'ang Ch'un, who rejected invitations from Song and Jin leaders, travelled more than 5000 kilometres to meet Genghis Khan close to the Afghanistan border. The first question Genghis Khan asked him was if the monk had some secret medicine that could make him immortal. The monk's negative answer disheartened Genghis Khan, and he rapidly lost interest in the monk. He also passed a decree exempting all followers of Taoist religion from paying any taxes. Genghis Khan was by and large tolerant of the multiple religions and there are no cases of him or the Mongols engaging in religious war against people he encountered during the conquests as long as they were obedient. However, all of his campaigns caused wanton and deliberate destruction of places of worship if they resisted.[21]

By others

The chronicler Minhaj al-Siraj Juzjani left a description of Genghis Khan, written when Genghis Khan was in his later years:

[Genghis Khan was] a man of tall stature, of vigorous build, robust in body, the hair on his face scanty and turned white, with cat's eyes, possessed of dedicated energy, discernment, genius, and understanding, awe-striking, a butcher, just, resolute, an overthrower of enemies, intrepid, sanguinary, and cruel.

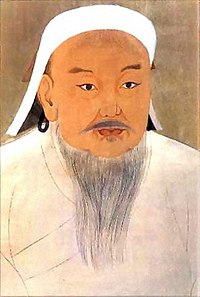

No valid, accurate portrait of Genghis exists today, and any portraits are merely artistic interpretations of him. The actual descriptions of Genghis Khan from contemporary historians of his time were quite different than what is usually found in the portraits, however. Muslim historian Rashid al-Din, foremost contemporary historian on Genghis Khan, recorded in his "Chronicles" that the legendary "glittering" ancestor of Genghis was tall, long-bearded, red-haired, and green-eyed. Rashid al-Din also described the first meeting of Genghis and Kublai Khan, when Genghis was shocked to find Kublai had not inherited his red hair.[22] Genghis's Borjigid clan, al-Din also reveals, had a legend involving their clan: it began as the result of an affair (technically an immaculate conception) between Alan-ko and a stranger to her land, a glittering man who happened to have red hair and bluish-green eyes. Modern historian Paul Ratchnevsky has suggested in his biography of Genghis that this strange man may have been from the Kyrgyz people who historically were noted as often displaying these very same characteristics. It is all purely speculative, however.

By himself

Perhaps a rare insight into Genghis Khan's perspective of himself was recorded in a letter to the Taoist monk Ch'ang Ch'un. The letter was presumably not written by Genghis Khan himself, as tradition states that he was illiterate, but rather by a Chinese person at a later point and recorded as his in the Chinese histories. A passage from the letter states:

Heaven has abandoned China owing to its haughtiness and extravagant luxury. But I, living in the northern wilderness, have not inordinate passions. I hate luxury and exercise moderation. I have only one coat and one food. I eat the same food and am dressed in the same tatters as my humble herdsmen. I consider the people my children, and take an interest in talented men as if they were my brothers. We always agree in our principles, and we are always united by mutual affection. At military exercises I am always in front, and in time of battle am never behind. In the space of seven years I have succeeded in accomplishing a great work, and uniting the whole world in one empire.. (Bretschneider)

Perceptions of Genghis Khan today

Positive perception of Genghis Khan

Negative views of Genghis Khan are very persistent with histories written by many different people from various different geographical regions often citing the cruelties and destructions brought upon by Mongol armies, but some historians are looking into positive aspects of Genghis Khan's conquests. Genghis Khan is sometimes credited with bringing the Silk Road under one cohesive political environment. Theoretically this allowed increased communication and trade between the West, Middle East and Asia by expanding the horizon of all three areas. In more recent times some historians point out that Genghis Khan instituted certain levels of meritocracy in his rule and was quite tolerant of many religions. For instance in much of modern-day Turkey, Genghis Khan is looked on as a great military leader and even many male children are named after him with pride.

Genghis Khan as an icon in Mongolia

Traditionally Genghis Khan had been revered for centuries among his people largely because of his association with the Mongol culture, political and military organization and the greater successes he had in warfare. He eventually became a larger-than-life figure among the Mongols. During the Mongolian People's Republic period Genghis Khan and Mongols topic were heavily and officially suppressed by the government that probably feared nationalist sentiment in the populace. For instance in 1962, the erection of a monument at his birthplace and a conference held in his honor led to criticism from the Soviet Union and resulted in the dismissal of Tömör-Ochir, a secretary of the ruling Mongolian People's Revolutionary Party Central Committee.

When democracy came about in Mongolia in the early 1990s after the democratic revolution, the memory of Genghis Khan and the Mongolian traditional national identity has had a powerful revival. Genghis Khan became the central figure of that identity. He is now a source of pride for Mongolians that ties with their identity. Being the symbol of a past often enough perceived to be more powerful and nicer than the present, he now stands almost at the center of Mongolian national identity. For instance it is not uncommon for Mongolians to refer to Mongolia as "Genghis Khan's Mongolia," to themselves as "Genghis Khan's children," and to Genghis Khan as "father of the Mongols" especially among younger people. Mongolians have given his name to many products, streets, buildings, and other places. For example his face can be found on liquors as well as on the largest denominations of 500, 1000, 5000 and 10,000 Mongolian tögrög (₮). Mongolia's main international airport in the capital Ulaanbaatar has been renamed Chinggis Khaan International Airport, and major statues of him have been erected before the parliament [2] and near Ulaanbaatar. There have been repeated discussions about regulating the use of his name and image as to avoid trivialization. Mongolians see him as a central figure in the founding of the Mongol nation and therefore basically setting up the basis for Mongolia as a country in one way or another.

Genghis Khan is now widely regarded as one of Mongolia's greatest, most legendary and cherished leaders. He is considered responsible for the emergence of the Mongols as a political and ethnic identity. He is also given credit for the introduction of the traditional Mongolian script and the creation of the Ikh Zasag, the first written Mongolian law. There is a chasm in the perception of his brutality - Mongolians often feel that the historical record, written for the most part by non-Mongolian observers, is unfairly biased against Genghis Khan, and exaggerates his barbarism and butchery while underplaying his positive role, for example in founding the Mongol nation. He reinforced many Mongol traditions and provided stability and unity for the Mongol nation at a time of great uncertainty due to both internal and external factors.

In China

The People's Republic of China considers Genghis Khan to be a Chinese national hero. The usual rationale for this claim is that there are more ethnic Mongols living inside the PRC than outside, including Mongolia. Another point is that his grandson Kublai Khan founded the increasingly sinicised Yuan Dynasty that is often credited with uniting China. However, historians, especially those in the West, see mixed feelings towards Genghis Khan's legacy. Although his successors completely conquered China with military force, there has also been much artwork and literature praising him as a great military leader and political genius. In any case, they left a significant, lasting, but debatable, imprint on Chinese political and social structures for subsequent generations.

Recognitions in publications

Genghis Khan is recognized in number of large and popular publications and by other authors, which include the following:

- Genghis Khan is ranked #29 on Michael H. Hart's list of the most influential people in history.

- An article that appeared in the Washington Post on December 31, 1995 selected Genghis Khan as "Man of the Millennium".

- Genghis Khan was nominated for the "Top 10 Cultural Legends of the Millennium" in 1998 by Dr G. Ab Arwel, voted by the five Judges, Prof. D Owain, Mr. G. Parry, OBE, Dr. C Campbell of Oxford University, and Mr S Evans and Sir B. Parry of the International Museum of Culture, Luxembourg.

- National Geographic's 50 Most Important Political Leaders of All Time.

Negative perception of Genghis Khan

In Iraq and Iran, he is looked on as a destructive and genocidal warlord who caused enormous damage and destruction [3]. Similarly, in Afghanistan and Pakistan (along with other non-Turkic Muslim countries) he is not looked with favour though some are ambivalent. It is believed that the Hazara of Afghanistan are descendants of a large Mongol garrison stationed therein. Nevertheless, the invasions of Baghdad and Samarkand caused mass murders, for example, and much of southern Khuzestan was completely destroyed. His descendant Hulagu Khan destroyed much of Iran's northern part. Among the Iranian peoples he is regarded as one of the most despised conquerors of Iran, along with Alexander and Tamerlane [4] [5]. In much of Russia, Ukraine, Poland and Hungary, Genghis Khan, his descendants and the Mongols and/or Tartars are generally described as causing considerable damage and destruction. Presently Genghis Khan, his descendants, his generals and in general the Mongols are remembered for their ferocious military, toughness, ruthless and destructive conquests in much of the world in history books.

Claimed descendants study

Zerjal et al [2003][23] identified a Y-chromosomal lineage present in about 8% of the men in a large region of Asia (about 0.5% of the men in the world). The paper suggests that the pattern of variation within the lineage is consistent with a hypothesis that it originated in Mongolia about 1,000 years ago. Such a spread would be too rapid to have occurred by genetic drift, and must therefore be the result of natural selection. The authors propose that the lineage is carried by likely male-line descendants of Genghis Khan, and that it has spread through social selection.

In addition to the Khanates and other descendants, the Mughal emperor Babur's mother was a descendant. Timur, the 14th century military leader, claimed descent from Genghis Khan.

Name and title

There are many theories about the origins of Temüjin's title. Since members of the Mongol Empire later associated the name with ching (Mongolian for strength), such confusion is obvious, though it does not follow etymology.

One theory suggests the name stems from a palatalised version of the Mongolian and Turkic word tenggiz, meaning "ocean", "oceanic" or "wide-spreading". (Lake Baikal and ocean were called tenggiz by the Mongols. However, it seems that if they had meant to call Genghis tenggiz they could have said (and written) "Tenggiz Khan", which they did not. Zhèng (Chinese: 正, pron. "jung" in English) meaning "right", "just", or "true", would have received the Mongolian adjectival modifier -s, creating "Jenggis", which in medieval romanization would be written "Genghis". It is likely that contemporary Mongols would have pronounced the word more like "Chinggis". Chingis Khan is the spelling used by the modern Republic of Mongolia. [6] See Lister and Ratchnevsky, referenced below, for further reading.

According to legend, Temüjin was named after one of the more powerful chiefs of a rival tribe which his father, Yesükhei, had recently defeated. The name "Temüjin" is believed to derive from the Turkic word temur, meaning iron (modern Mongolian: төмөр, tömör). This name would imply skill as a blacksmith, and like any nomad of the time he was familiar, at least partially, with the working of iron for horse-shoeing and weaponry.

More likely, as no evidence has survived to indicate that Genghis Khan had any exceptional training or reputation as a blacksmith, the name indicated an implied lineage in a family once known as blacksmiths. The latter interpretation is supported by the names of Genghis Khan's siblings, Temülin and Temüge, which are derived from the same root word.

Name and spelling variations

Genghis Khan's name is spelled in variety of ways in different languages such as Chinese: 成吉思汗; pinyin: Chéngjísī Hán, Turkic: Cengiz Han, Chengez Khan, Chinggis Khan, Chinggis Xaan, Chingis Khan, Jenghis Khan, Chinggis Qan, Djingis Kahn etc.). Temüjin is written in Chinese as simplified Chinese: 铁木真; traditional Chinese: 鐵木真; pinyin: Tiěmùzhēn.

Short timeline

- c. 1155-1167—Temüjin born in Hentiy, Mongolia.

- c. 1171—Temüjin's father Yesükhei poisoned by the Tatars, leaving him and his family destitute

- c. 1184—Temüjin's wife Börte kidnapped by Merkits; calls on blood brother Jamuqa and Wang Khan (Ong Khan) for aid, and they rescued her.

- c. 1185—First son Jochi born, leading to doubt about his paternity later among Genghis' children, because he was born shortly after Börte's rescue from the Merkits.

- 1190—Temüjin unites the Mongol tribes, becomes leader, and devises code of law Yassa.

- 1201—Wins victory over Jamuqa's Jadarans.

- 1202—Adopted as Ong Khan's heir after successful campaigns against Tatars.

- 1203—Wins victory over Ong Khan's Keraits. Ong Khan himself is killed by accident.

- 1204—Wins victory over Naimans (all these confederations are united and become the Mongols).

- 1206—Jamuqa is killed. Temüjin given the title Genghis Khan by his followers in Kurultai (around 40 years of age).

- 1207-1210—Genghis leads operations against the Western Xia, which comprises much of northwestern China and parts of Tibet. Western Xia ruler submits to Genghis Khan. During this period, the Uyghurs also submit peacefully to the Mongols and became valued administrators throughout the empire.

- 1211—After kurultai, Genghis leads his armies against the Jin Dynasty that ruled northern China.

- 1215—Beijing falls, Genghis Khan turns to west and the Khara-Kitan Khanate.

- 1219-1222—Conquers Khwarezmid Empire.

- 1226—Starts the campaign against the Western Xia for forming coalition against the Mongols, being the second battle with the Western Xia.

- 1227—Genghis Khan dies leading fight against Western Xia. How he died is uncertain, although legend states that he was thrown off his horse in the battle, and contracted a deadly fever soon after.

Notes

- ^ Rashid al-Din asserts that Genghis Khan lived to the age of 72, placing his year of birth at 1155. The Yuanshi (元史, History of the Yuan dynasty, not to be confused with the era name of the Han Dynasty), records his year of birth as 1165. According to Ratchnevsky, accepting a birth in 1155 would render Genghis Khan a father only at the age of 30 and would imply that at the ripe age of 72 he personally commanded the expedition against the Tanguts. Also, according to the Altan Tobci, Genghis Khan's sister, Temülin, was nine years younger than he; but the Secret History relates that Temülin was an infant during the attack by the Merkits, during which Genghis Khan would have been 18, had he been born in 1155. Zhao Hong reports in his travelogue that the Mongols he questioned did not know and had never known their ages.

- ^ Conferred posthumously by his son Ögedei Khan when he took the new title

- ^ http://afe.easia.columbia.edu/mongols/history/history.htm

- ^ Morgan, David, The Mongols (Peoples of Europe), 1990, p.58.

- ^ Ratchnevsky, Paul (1991). Genghis Khan: His Life and Legacy. Blackwell Publishing. pp. 9–10. ISBN 0-631-16785-4.

- ^ Ratchnevsky, Paul. Genghis Khan: His Life and Legacy, 1991, p. 126.

- ^ . Some scholars, notably Ratchnevsky, have commented on the possibility that Jochi was secretly poisoned by order of Genghis Khan. Rashid al-Din reports that the great Khan sent for his sons in the spring of 1223, and while his brothers heeded the order, Jochi remained in Khorasan. Juzjani suggests that the disagreement arose from a quarrel between Jochi and his brothers in the siege of Urgench, which Jochi attempted to protect from destruction as it belonged to territory allocated to him as a fief. He concludes his story with the clearly apocryphal statement by Jochi: "Genghis Khan is mad to have massacred so many people and laid waste so many lands. I would be doing a service if I killed my father when he is hunting, made an alliance with Sultan Muhammad, brought this land to life and gave assistance and support to the Muslims." Juzjani claims that it was in response to hearing of these plans that Genghis Khan ordered his son secretly poisoned; however, as Sultan Muhammad was already dead in 1223, the accuracy of this story is questionable. hi (Ratchnevsky, p. 136-7)

- ^ http://www.csuchico.edu/~cheinz/syllabi/fall99/kong/Index1.htm

- ^ Grousset, Rene. Conqueror of the World: The Life of Chingis-khan (New York: The Viking Press, 1944) SBN 670-00343-3.

- ^ Man, John. Genghis Khan : Life, Death and Resurrection (London; New York : Bantam Press, 2004) ISBN 0-593-05044-4.

- ^ Man, John. Genghis Khan: Life, Death and Resurrection (London; New York: Bantam Press, 2004) ISBN 0-593-05044-4.

- ^ De Hartog, Leo (1988). Genghis Khan: Conqueror of the World. London, UK: I.B. Tauris & Co. Ltd. pp. 122–123.

- ^ De Hartog, Leo (1988). Genghis Khan: Conqueror of the World. London, UK: I.B. Tauris & Co. Ltd. p. 42.

- ^ Man, John. Genghis Khan : Life, Death and Resurrection (London; New York : Bantam Press, 2004) ISBN 0-593-05044-4.

- ^ Ping-ti Ho, "An Estimate of the Total Population of Sung-Chin China", in Études Song, Series 1, No 1, (1970) pp. 33-53.

- ^ History of Russia, Early Slavs history, Kievan Rus, Mongol invasion

- ^ Battuta's Travels: Part Three - Persia and Iraq

- ^ Welcome to Encyclopædia Britannica's Guide to History

- ^ Morgan, David (1986). The Mongols (Peoples of Europe). Blackwell Publishing. pp. 74–75. ISBN 0-631-17563-6.

- ^ Ratchnevsky, Paul (1991). Genghis Khan: His Life and Legacy. Blackwell Publishing. pp. 131–133. ISBN 0-631-16785-4.

- ^ Man, John. Genghis Khan : Life, Death and Resurrection (London; New York : Bantam Press, 2004) ISBN 0-593-05044-4.

- ^ http://www.republicanchina.org/Mongols.html

- ^ Zerjal et. al, (2003) The Genetic Legacy of the Mongols. American Journal of Human Genetics 72(3):717-721 (PubMed)

External links

- Book Review of Genghis Khan by Leo De Hartog

- Genghis Khan and Successors.

- Genghis Khan and the Mongols

- Welcome to The Realm of the Mongols

- Parts of this biography were taken from the Area Handbook series at the Library of Congress

- Coverage of Temüjin's Earlier Years

- Estimates of Mongol warfare casualties

- Genghis Khan on the Web (directory of some 250 resources)

- Mongol Arms

- LeaderValues

- ‘Ala’ al-Din ‘Ata Malik Juvayni (A History of the World-Conqueror Ghengis Genghis Khan, Ata al-Mulk Juvayni and Rashid al-Din Hamadani)

- iExplore.com: The search for the missing tomb of Genghis Khan

- BBC Radio 4 programme "In Our Time", topic was "Genghis Khan", 1 February 2007. With Peter Jackson, Professor of Medieval History at Keele University, Naomi Standen, Lecturer in Chinese History at Newcastle University, and George Lane, Lecturer in History at the School of Oriental and African Studies and presented by Melvyn Bragg.

References

- Brent, Peter. The Mongol Empire: Genghis Khan: His Triumph and his Legacy. Book Club Associates, London. 1976.

- Weatherford, Jack. Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World (New York : Crown, 2004) ISBN 0-609-61062-7.

- Kennedy, Hugh. Mongols, Huns & Vikings (London : Cassell, 2002) ISBN 0-304-35292-6.

- "Genghis Khan and the Mongols". Genghis Khan and the Mongols. Retrieved June 30.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - Man, John. Genghis Khan : Life, Death and Resurrection (London; New York : Bantam Press, 2004) ISBN 0-593-05044-4.

- Lister, R. P. Genghis Khan (Lanham, Md. : Cooper Square Press, 2000 [c1969]) ISBN 0-8154-1052-2.

- Eric Jameson professeur of ancient Asian rulers at Harvard

- "Mongol Arms". Mongol Arms. Retrieved June 24.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - Heirs to Discord: The Supratribal Aspirations of Jamuqa, Toghrul, and Temüjin

- Ratchnevsky, Paul. Genghis Khan: His Life and Legacy [Čingis-Khan: sein Leben und Wirken] (Oxford, UK ; Cambridge, Mass., USA : B. Blackwell, 1992, c1991) tr. & ed. Thomas Nivison Haining, ISBN 0-631-16785-4.

- Bretschneider, Emilii. Mediæval Researches from Eastern Asiatic Sources. London: K. Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co. ISBN 81-215-1003-1.

- History of the Mongol Conquests, JJ Saunders, U. Pennsylvania Press, 1972

- Genocide: A Critical Bibliographic Review edited by Israel W Charney, 1994

- Final Solutions: Mass Killing and Genocide in the Twentieth Century by Benjamin A Valentino

- Zerjal, Xue, Bertorelle, Wells, Bao, Zhu, Qamar, Ayub, Mohyuddin, Fu, Li, Yuldasheva, Ruzibakiev, Xu, Shu, Du, Yang, Hurles, Robinson, Gerelsaikhan, Dashnyam, Mehdi, Tyler-Smith (2003). "The Genetic Legacy of the Mongols" (PDF). The American Journal of Human Genetics (72): 717–721, .

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - De Hartog, Leo (1988). Genghis Khan: Conqueror of the World. London, UK: I.B. Tauris & Co. Ltd.

- Morgan, David (1986). The Mongols (Peoples of Europe). Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-17563-6.

Primary sources

- Juvaynī, Alā al-Dīn Atā Malik, 1226-1283. Genghis Khan: The History of the World-Conqueror [Tarīkh-i jahāngushā. English] (Seattle : UWashington Press, 1997) tr. John Andrew Boyle, ISBN 0-295-97654-3.

- The Secret History of the Mongols (Leiden; Boston : Brill, 2004) tr. Igor De Rachewiltz, Brill's Inner Asian Library. v.7, ISBN 90-04-13159-0.

- A Compendium of Chronicles: Rashid al-Din's Illustrated History of the World [Jami al-Tawarikh] (Oxford : Oxford University Press, 1995) The Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic Art, Vol. XXVII, ed. Sheila S. Blair, ISBN 0-19-727627-X.

- Tabib, Rashid al-Din. The Successors of Genghis Khan (New York : Columbia University Press, 1971) tr. from the Persian by John Andrew Boyle, [extracts from Jami’ Al-Tawarikh], UNESCO collection of representative works: Persian heritage series, ISBN 0-231-03351-6.http://www.questia.com/PM.qst?a=o&d=109217551

Further reading

- Cable, Mildred and Francesca French. The Gobi Desert (London: Landsborough Publications, 1943).

- Lamb, Harold, Genghis Khan: The Emperor of All Men, 1927.

- Man, John. Gobi : Tracking the Desert (London : Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1997) hardbound; (London : Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1998) paperbound, ISBN 0-7538-0161-2; (New Haven: Yale, 1999) hardbound.

- Stewart, Stanley. In the Empire of Genghis Khan: A Journey among Nomads (London: Harper Collins, 2001) ISBN 0-00-653027-3.

- History Channel's biography of Genghis Khan

- Secret History of the Mongols: The Origin of Chingis Khan (expanded edition) (Boston: Cheng & Tsui Asian Culture Series, 1998) adapted by Paul Kahn, ISBN 0-88727-299-1.

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA