Gender equality

| Part of a series on |

| Feminism |

|---|

|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Masculism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Liberalism |

|---|

|

Gender equality, also known as sexual equality or equality of the sexes, is the state of equal ease of access to resources and opportunities regardless of gender, including economic participation and decision-making, and the state of valuing different behaviors, aspirations, and needs equally, also regardless of gender.[1] To avoid complication, other genders (besides women and men) will not be treated in this Gender equality article.

UNICEF (an agency of the United Nations) defines gender equality as "women and men, and girls and boys, enjoy the same rights, resources, opportunities and protections. It does not require that girls and boys, or women and men, be the same, or that they be treated exactly alike."[2][a]

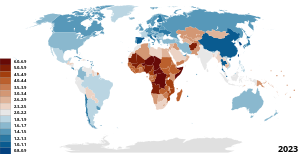

As of 2017,[update] gender equality is the fifth of seventeen sustainable development goals (SDG 5) of the United Nations; gender equality has not incorporated the proposition of genders besides women and men, or gender identities outside of the gender binary. Gender inequality is measured annually by the United Nations Development Programme's Human Development Reports.

Gender equality can refer to equal opportunities or formal equality based on gender or refer to equal representation or equality of outcomes for gender, also called substantive equality.[3] Gender equality is the goal, while gender neutrality and gender equity are practices and ways of thinking that help achieve the goal. Gender parity, which is used to measure gender balance in a given situation, can aid in achieving substantive gender equality but is not the goal in and of itself. Gender equality is strongly tied to women's rights, and often requires policy changes.

On a global scale, achieving gender equality also requires eliminating harmful practices against women and girls, including sex trafficking, femicide, wartime sexual violence, gender wage gap,[4] and other oppression tactics. UNFPA stated that "despite many international agreements affirming their human rights, women are still much more likely than men to be poor and illiterate. They have less access to property ownership, credit, training, and employment. This partly stems from the archaic stereotypes of women being labeled as child-bearers and homemakers, rather than the breadwinners of the family.[5] They are far less likely than men to be politically active and far more likely to be victims of domestic violence."[6]

History

Christine de Pizan, an early advocate for gender equality, states in her 1405 book The Book of the City of Ladies that the oppression of women is founded on irrational prejudice, pointing out numerous advances in society probably created by women.[7][8]

Shakers

The Shakers, an evangelical group, which practiced segregation of the sexes and strict celibacy, were early practitioners of gender equality. They branched off from a Quaker community in the north-west of England before emigrating to America in 1774. In America, the head of the Shakers' central ministry in 1788, Joseph Meacham, had a revelation that the sexes should be equal. He then brought Lucy Wright into the ministry as his female counterpart, and together they restructured the society to balance the rights of the sexes. Meacham and Wright established leadership teams where each elder, who dealt with the men's spiritual welfare, was partnered with an eldress, who did the same for women. Each deacon was partnered with a deaconess. Men had oversight of men; women had oversight of women. Women lived with women; men lived with men. In Shaker society, a woman did not have to be controlled or owned by any man. After Meacham's death in 1796, Wright became the head of the Shaker ministry until her death in 1821.

Shakers maintained the same pattern of gender-balanced leadership for more than 200 years. They also promoted equality by working together with other women's rights advocates. In 1859, Shaker Elder Frederick Evans stated their beliefs forcefully, writing that Shakers were "the first to disenthrall woman from the condition of vassalage to which all other religious systems (more or less) consign her, and to secure to her those just and equal rights with man that, by her similarity to him in organization and faculties, both God and nature would seem to demand".[9] Evans and his counterpart, Eldress Antoinette Doolittle, joined women's rights advocates on speakers' platforms throughout the northeastern U.S. in the 1870s. A visitor to the Shakers wrote in 1875:

Each sex works in its own appropriate sphere of action, there being a proper subordination, deference and respect of the female to the male in his order, and of the male to the female in her order [emphasis added], so that in any of these communities the zealous advocates of "women's rights" may here find a practical realization of their ideal.[10]

The Shakers were more than a radical religious sect on the fringes of American society; they put equality of the sexes into practice. It has been argued that they demonstrated that gender equality was achievable and how to achieve it.[11]

Suffrage movement

In wider society, the movement towards gender equality began with the suffrage movement in Western cultures in the late-19th century, which sought to allow women to vote and hold elected office. This period also witnessed significant changes to women's property rights, particularly in relation to their marital status. (See for example, Married Women's Property Act 1882.)

Early Soviet Union

Starting in 1927 the Communist Party of the Soviet Union enforced gender equality within Soviet Central Asia during Hujum campaign.[12]

Post-war era

Since World War II, the women's liberation movement and feminism have created a general movement towards recognition of women's rights. The United Nations and other international agencies have adopted several conventions which promote gender equality. These conventions have not been uniformly adopted by all countries, and include:

- The Convention against Discrimination in Education was adopted in 1960, and came into force in 1962 and 1968.

- The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) was adopted in 1979 by the United Nations General Assembly. It has been described as an international bill of rights for women, which came into force on 3 September 1981.

- The Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action, a human rights declaration adopted by consensus at the World Conference on Human Rights on 25 June 1993 in Vienna, Austria. Women's rights are addressed at para 18.[13]

- The Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 1993.

- In 1994, the twenty-year Cairo Programme of Action was adopted at the International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) in Cairo. This non binding programme-of-action asserted that governments have a responsibility to meet individuals' reproductive needs, rather than demographic targets. As such, it called for family planning, reproductive rights services, and strategies to promote gender equality and stop violence against women.

- Also in 1994, in the Americas, the Inter-American Convention on the Prevention, Punishment and Eradication of Violence against Women, known as the Belém do Pará Convention, called for the end of violence and discrimination against women.[14]

- At the end of the Fourth World Conference on Women, the UN adopted the Beijing Declaration on 15 September 1995 – a resolution adopted to promulgate a set of principles concerning gender equality.

- The United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325 (UNSRC 1325), which was adopted on 31 October 2000, deals with the rights and protection of women and girls during and after armed conflicts.

- The Maputo Protocol guarantees comprehensive rights to women, including the right to take part in the political process, to social and political equality with men, to control their reproductive health, and an end to female genital mutilation. It was adopted by the African Union in the form of a protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights and came into force in 2005.

- The EU directive Directive 2002/73/EC – equal treatment of 23 September 2002 amending Council Directive 76/207/EEC on the implementation of the principle of equal treatment for men and women as regards access to employment, vocational training and promotion, and working conditions states that: "Harassment and sexual harassment within the meaning of this Directive shall be deemed to be discrimination on the grounds of sex and therefore prohibited."[15]

- The Council of Europe's Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence, the first legally binding instrument in Europe in the field of violence against women,[16] came into force in 2014.

- The Council of Europe's Gender Equality Strategy 2014–2017, which has five strategic objectives:[17]

- Combating gender stereotypes and sexism

- Preventing and combating violence against women

- Guaranteeing Equal Access of Women to Justice

- Achieving balanced participation of women and men in political and public decision-making

- Achieving Gender Mainstreaming in all policies and measures

Such legislation and affirmative action policies have been critical to bringing changes in societal attitudes. A 2015 Pew Research Center survey of citizens in 38 countries found that majorities in 37 of those 38 countries said that gender equality is at least "somewhat important", and a global median of 65% believe it is "very important" that women have the same rights as men.[18] Most occupations are now equally available to men and women, in many countries.[i]

Similarly, men are increasingly working in occupations which in previous generations had been considered women's work, such as nursing, cleaning and child care. In domestic situations, the role of Parenting or child rearing is more commonly shared or not as widely considered to be an exclusively female role, so that women may be free to pursue a career after childbirth. For further information, see Shared earning/shared parenting marriage.

Another manifestation of the change in social attitudes is the non-automatic taking by a woman of her husband's surname on marriage.[19]

A highly contentious issue relating to gender equality is the role of women in religiously orientated societies.[ii][iii] Some Christians or Muslims believe in Complementarianism, a view that holds that men and women have different but complementing roles. This view may be in opposition to the views and goals of gender equality.

In addition, there are also non-Western countries of low religiosity where the contention surrounding gender equality remains. In China, a cultural preference for a male child has resulted in a shortfall of women in the population. The feminist movement in Japan has made many strides which resulted in the Gender Equality Bureau, but Japan still remains low in gender equality compared to other industrialized nations.Developing countries like Kenya, on the other hand, do not have official national statistics and have to rely on some gender-disaggregated statistics, usually funded by international organizations, for their analysis.[20]

The notion of gender equality, and of its degree of achievement in a certain country, is very complex because there are countries that have a history of a high level of gender equality in certain areas of life but not in other areas.[iv][v] Indeed, there is a need for caution when categorizing countries by the level of gender equality that they have achieved.[21] According to Mala Htun and S. Laurel Weldon "gender policy is not one issue but many" and:[22]

When Costa Rica has a better maternity leave than the United States, and Latin American countries are quicker to adopt policies addressing violence against women than the Nordic countries, one at least ought to consider the possibility that fresh ways of grouping states would further the study of gender politics.

Not all beliefs relating to gender equality have been popularly adopted. For example, topfreedom, the right to be bare breasted in public, frequently applies only to males and has remained a marginal issue. Breastfeeding in public is now more commonly tolerated, especially in semi-private places such as restaurants.[23]

United Nations

It is the vision that men and women should be treated equally in social, economic and all other aspects of society, and to not be discriminated against on the basis of their gender.[vi] Gender equality is one of the objectives of the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights.[24] World bodies have defined gender equality in terms of human rights, especially women's rights, and economic development.[25][26] The United Nation's Millennium Development Goals Report states that their goal is to "achieve gender equality and the empowerment of women". Despite economic struggles in developing countries, the United Nations is still trying to promote gender equality, as well as help create a sustainable living environment is all its nations. Their goals also include giving women who work certain full-time jobs equal pay to the men with the same job.

Contemporary efforts to fight inequality

In 2010, the European Union opened the European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE) in Vilnius, Lithuania to promote gender equality and to fight sex discrimination. In 2015 the EU published the Gender Action Plan 2016–2020.[27]

Gender equality is part of the national curriculum in Great Britain and many other European countries. By presidential decree, the Republic of Kazakhstan created a Strategy for Gender Equality 2006–2016 to chart the subsequent decade of gender equality efforts.[28] Personal, social, health and economic education, religious studies and language acquisition curricula tend to address gender equality issues as a very serious topic for discussion and analysis of its effect in society.

A large and growing body of research has shown how gender inequality undermines health and development. To overcome gender inequality the United Nations Population Fund states that women's empowerment and gender equality requires strategic interventions at all levels of programming and policy-making. These levels include reproductive health, economic empowerment, educational empowerment and political empowerment.[29]

UNFPA says that "research has also demonstrated how working with men and boys as well as women and girls to promote gender equality contributes to achieving health and development outcomes."[30]

The extent to which national policy frameworks address gender issues improved over the past decade. National policies and budgets in East Africa and Latin America, for example, have increasingly highlighted structural gaps in access to land, inputs, services, finance and digital technology and included efforts to produce gender-responsive outcomes.[31] However, the extent to which agricultural policies specifically address gender equality and women's empowerment varies.[31]

Even though more than 75 percent of agricultural policies that the Food and Agriculture Organization analysed recognized women's roles and/or challenges in agriculture, only 19 percent had gender equality in agriculture or women's rights as explicit policy objectives. And only 13 percent encouraged rural women's participation in the policy cycle.[31]

Health and safety

Effect of gender inequality on health

Social constructs of gender (that is, cultural ideals of socially acceptable masculinity and femininity) often have a negative effect on health. The World Health Organization cites the example of women not being allowed to travel alone outside the home (to go to the hospital), and women being prevented by cultural norms to ask their husbands to use a condom, in cultures which simultaneously encourage male promiscuity, as social norms that harm women's health. Teenage boys suffering accidents due to social expectations of impressing their peers through risk taking, and men dying at much higher rate from lung cancer due to smoking, in cultures which link smoking to masculinity, are cited by the WHO as examples of gender norms negatively affecting men's health.[32] The World Health Organization has also stated that there is a strong connection between gender socialization and transmission and lack of adequate management of HIV/AIDS.[33]

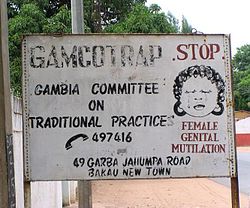

Certain cultural practices, such as female genital mutilation (FGM), negatively affect women's health.[35] Female genital mutilation is the ritual cutting or removal of some or all of the external female genitalia. It is rooted in inequality between the sexes, and constitutes a form of discrimination against women.[35] The practice is found in Africa,[1] Asia and the Middle East, and among immigrant communities from countries in which FGM is common. The preference rate in Kenya is 21 per cent and an estimated 4 million girls and women have undergone FGM in Kenya with hot spot areas/ communities including the Kuria community both in Kenya and Tanzania border, Kisii, Maasai, Somali, Samburu and Kuria ethnic groups. UNICEF estimated in 2016 that 200 million women have undergone the procedure.[36]

According to the World Health Organization, gender equality can improve men's health. The study shows that traditional notions of masculinity have a big impact on men's health. Among European men, non-communicable diseases, such as cancer, cardiovascular diseases, respiratory illnesses, and diabetes, account for the vast majority of deaths of men aged 30–59 in Europe which are often linked to unhealthy diets, stress, substance abuse, and other habits, which the report connects to behaviors often stereotypically seen as masculine behaviors like heavy drinking and smoking. Traditional gender stereotypes that keep men in the role of breadwinner and systematic discrimination preventing women from equally contributing to their households and participating in the workforce can put additional stress on men, increasing their risk of health issues, and men bolstered by cultural norms tend to take more risks and engage in interpersonal violence more often than women, which could result in fatal injuries.[37][38][39][40]

Violence against women

Violence against women (VAW) is a technical term used to collectively refer to violent acts that are primarily or exclusively committed against women.[vii] This type of violence is gender-based, meaning that the acts of violence are committed against women expressly because they are women, or as a result of patriarchal gender constructs.[viii] Violence and mistreatment of women in marriage has come to international attention during the past decades. This includes both violence committed inside marriage (domestic violence) as well as violence related to marriage customs and traditions (such as dowry, bride price, forced marriage and child marriage).

According to some theories, violence against women is often caused by the acceptance of violence by various cultural groups as a means of conflict resolution within intimate relationships. Studies on Intimate partner violence victimization among ethnic minorities in the United Studies have consistently revealed that immigrants are a high-risk group for intimate violence.[41][42]

In countries where gang murders, armed kidnappings, civil unrest, and other similar acts are rare, the vast majority of murdered women are killed by partners/ex-partners.[ix] By contrast, in countries with a high level of organized criminal activity and gang violence, murders of women are more likely to occur in a public sphere, often in a general climate of indifference and impunity.[43] In addition, many countries do not have adequate comprehensive data collection on such murders, aggravating the problem.[43]

In some parts of the world, various forms of violence against women are tolerated and accepted as parts of everyday life.[x]

In most countries, it is only in more recent decades that domestic violence against women has received significant legal attention. The Istanbul Convention acknowledges the long tradition of European countries of ignoring this form of violence.[xi][xii]

In some cultures, acts of violence against women are seen as crimes against the male 'owners' of the woman, such as husband, father or male relatives, rather the woman herself. This leads to practices where men inflict violence upon women in order to get revenge on male members of the women's family.[44] Such practices include payback rape, a form of rape specific to certain cultures, particularly the Pacific Islands, which consists of the rape of a female, usually by a group of several males, as revenge for acts committed by members of her family, such as her father or brothers, with the rape being meant to humiliate the father or brothers, as punishment for their prior behavior towards the perpetrators.[45]

Richard A. Posner writes that "Traditionally, rape was the offense of depriving a father or husband of a valuable asset — his wife's chastity or his daughter's virginity".[46] Historically, rape was seen in many cultures (and is still seen today in some societies) as a crime against the honor of the family, rather than against the self-determination of the woman. As a result, victims of rape may face violence, in extreme cases even honor killings, at the hands of their family members.[47][48] Catharine MacKinnon argues that in male dominated societies, sexual intercourse is imposed on women in a coercive and unequal way, creating a continuum of victimization, where women have few positive sexual experiences.[xiii] Socialization within rigid gender constructs often creates an environment where sexual violence is common.[xiv] One of the challenges of dealing with sexual violence is that in many societies women are perceived as being readily available for sex, and men are seen as entitled to their bodies, until and unless women object.[49][50][xv]

Types of VAW

Violence against women may be classified according to different approaches.

- WHO's life cycle typology:

The World Health Organization (WHO) has developed a typology of violence against women based on their cultural life cycles.

| Phase | Type of violence |

| Pre-birth | Sex-selective abortion; effects of battering during pregnancy on birth outcomes |

| Infancy | Female infanticide; physical, sexual and psychological abuse |

| Girlhood | Child marriage; female genital mutilation; physical, sexual and psychological abuse; incest; child prostitution and pornography |

| Adolescence and adulthood | Dating and courtship violence (e.g. acid throwing and date rape); economically coerced sex (e.g. school girls having sex with "sugar daddies" in return for school fees); incest; sexual abuse in the workplace; rape; sexual harassment; forced prostitution and pornography; trafficking in women; partner violence; marital rape; dowry abuse and murders; partner homicide; psychological abuse; abuse of women with disabilities; forced pregnancy |

| Elderly | Forced "suicide" or homicide of widows for economic reasons; sexual, physical and psychological abuse[51] |

Significant progress towards the protection of women from violence has been made on international level as a product of collective effort of lobbying by many women's rights movements; international organizations to civil society groups. As a result, worldwide governments and international as well as civil society organizations actively work to combat violence against women through a variety of programs. Among the major achievements of the women's rights movements against violence on girls and women, the landmark accomplishments are the "Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women" that implies "political will towards addressing VAW " and the legal binding agreement, "the Convention on Elimination of all forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW)".[52] In addition, the UN General Assembly resolution also designated 25 November as International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women.[53]

- The Lancet's over time typology:

A typology similar to the WHO's from an article on violence against women published in the academic journal The Lancet shows the different types of violence perpetrated against women according to what time period in a women's life the violence takes place.[54] However, it also classifies the types of violence according to the perpetrator. One important point to note is that more of the types of violence inflicted on women are perpetrated by someone the woman knows, either a family member or intimate partner, rather than a stranger.

- Council of Europe's nine forms of violence:

The Gender Equality Commission of the Council of Europe identifies nine forms of violence against women based on subject and context rather than life cycle or time period:[55][56]

- 'Violence within the family or domestic violence'

- 'Rape and sexual violence'

- 'Sexual harassment'

- 'Violence in institutional environments'

- 'Female genital mutilation'

- 'Forced marriages'

- 'Violence in conflict and post-conflict situations'

- 'Killings in the name of honour'

- 'Failure to respect freedom of choice with regard to reproduction'

Violence against trans women

Killings of transgender individuals, especially transgender women, continue to rise yearly. 2020 saw a record 350 transgender individuals murdered, with means including suffocation and burning alive.[57]

In 2009, United States data showed that transgender people are likely to experience a broad range of violence in the entirety of their lifetime. Violence against trans women in Puerto Rico started to make headlines after being treated as "An Invisible Problem" decades before. It was reported at the 58th Convention of the Puerto Rican Association that many transgender women face institutional, emotional, and structural obstacles. Most trans women do not have access to health care for STD prevention and are not educated on violence prevention, mental health, and social services that could benefit them.[58]

Trans women in the United States have been the subject of anti-trans stigma, which includes criminalization, dehumanization, and violence against those who identify as transgender. From a societal standpoint, a trans person can be victim to the stigma due to lack of family support, issues with health care and social services, police brutality, discrimination in the work place, cultural marginalisation, poverty, sexual assault, assault, bullying, and mental trauma. The Human Rights Campaign tracked over 128 cases[clarification needed] that ended in fatality against transgender people in the US from 2013 to 2018, of which eighty percent included a trans woman of color. In the US, high rates of Intimate Partner violence impact trans women differently because they are facing discrimination from police and health providers, and alienation from family. In 2018, it was reported that 77 percent of transgender people who were linked to sex work and 72 percent of transgender people who were homeless, were victims of intimate partner violence.[59]

Reproductive and sexual health and rights

The importance of women having the right and possibility to have control over their body, reproduction decisions, and sexuality, and the need for gender equality in order to achieve these goals are recognized as crucial by the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing and the UN International Conference on Population and Development Program of Action. The World Health Organization (WHO) has stated that promotion of gender equality is crucial in the fight against HIV/AIDS.[33]

Maternal mortality is a major problem in many parts of the world. UNFPA states that countries have an obligation to protect women's right to health, but many countries do not do that.[61] Maternal mortality is considered today not just an issue of development but also an issue of human rights.[xvi]

The right to reproductive and sexual autonomy is denied to women in many parts of the world, through practices such as forced sterilization, forced/coerced sexual partnering (e.g. forced marriage, child marriage), criminalization of consensual sexual acts (such as sex outside marriage), lack of criminalization of marital rape, violence in regard to the choice of partner (honor killings as punishment for 'inappropriate' relations).[xvii] The sexual health of women is often poor in societies where a woman's right to control her sexuality is not recognized.[xviii]

Adolescent girls have the highest risk of sexual coercion, sexual ill health, and negative reproductive outcomes. The risks they face are higher than those of boys and men; this increased risk is partly due to gender inequity (different socialization of boys and girls, gender based violence, child marriage) and partly due to biological factors.[xix]

Family planning and abortion

Family planning is the practice of freely deciding the number of children one has and the intervals between their births, particularly by means of contraception or voluntary sterilization. Abortion is the induced termination of pregnancy. Abortion laws vary significantly by country. The availability of contraception, sterilization and abortion is dependent on laws, as well as social, cultural and religious norms. Some countries have liberal laws regarding these issues, but in practice it is very difficult to access such services due to doctors, pharmacists and other social and medical workers being conscientious objectors.[62][63] Family planning is particularly important from a women's rights perspective, as having very many pregnancies, especially in areas where malnutrition is present, can seriously endanger women's health. UNFA writes that "Family planning is central to gender equality and women's empowerment, and it is a key factor in reducing poverty".[64]

Family planning is often opposed by governments who have strong natalist policies. During the 20th century, such examples have included the aggressive natalist policies from communist Romania and communist Albania. State mandated forced marriage was also practiced by some authoritarian governments as a way to meet population targets: the Khmer Rouge regime in Cambodia systematically forced people into marriages, in order to increase the population and continue the revolution.[65] By contrast, the one-child policy of China (1979–2015) included punishments for families with more than one child and forced abortions. The fine is so-called "social maintenance fee" and it is the punishment for the families who have more than one child. According to the policy, the families who violate the law may bring the burden to the whole sociey. Therefore, the social maintenance fee will be used for the operation of the basic government.[66] Some governments have sought to prevent certain ethnic or social groups from reproduction. Such policies were carried out against ethnic minorities in Europe and North America in the 20th century, and more recently in Latin America against the Indigenous population in the 1990s; in Peru, President Alberto Fujimori (in office from 1990 to 2000) has been accused of genocide and crimes against humanity as a result of a sterilization program put in place by his administration targeting indigenous people (mainly the Quechuas and the Aymaras).[67]

Investigation and prosecution of crimes against women and girls

Human rights organizations have expressed concern about the legal impunity of perpetrators of crimes against women, with such crimes being often ignored by authorities.[68] This is especially the case with murders of women in Latin America.[69][70][71] In particular, there is impunity in regard to domestic violence.[xx]

Women are often, in law or in practice, unable to access legal institutions. UN Women has said that: "Too often, justice institutions, including the police and the courts, deny women justice".[72] Often, women are denied legal recourse because the state institutions themselves are structured and operate in ways incompatible with genuine justice for women who experience violence.[xxi]

Harmful traditional practices

"Harmful traditional practices" refer to forms of violence which are committed in certain communities often enough to become cultural practice, and accepted for that reason. Young women are the main victims of such acts, although men can also be affected.[73] They occur in an environment where women and girls have unequal rights and opportunities.[74] These practices include, according to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights:[74]

female genital mutilation (FGM); forced feeding of women; early marriage; the various taboos or practices which prevent women from controlling their own fertility; nutritional taboos and traditional birth practices; son preference and its implications for the status of the girl child; female infanticide; early pregnancy; and dowry price

Son preference refers to a cultural preference for sons over daughters, and manifests itself through practices such as sex selective abortion; female infanticide; or abandonment, neglect or abuse of girl-children.[74]

Abuses regarding nutrition are taboos in regard to certain foods, which result in poor nutrition of women, and may endanger their health, especially if pregnant.[74]

The caste system in India which leads to untouchability (the practice of ostracizing a group by segregating them from the mainstream society) often interacts with gender discrimination, leading to a double discrimination faced by Dalit women.[75] In a 2014 survey, 27% of Indians admitted to practicing untouchability.[76]

Traditional customs regarding birth sometimes endanger the mothers. Births in parts of Africa are often attended by traditional birth attendants (TBAs), who sometimes perform rituals that are dangerous to the health of the mother. In many societies, a difficult labour is believed to be a divine punishment for marital infidelity, and such women face abuse and are pressured to "confess" to the infidelity.[74]

Tribal traditions can be harmful to males; for instance, the Satere-Mawe tribe use bullet ants as an initiation rite. Men must wear gloves with hundreds of bullet ants woven in for ten minutes: the ants' stings cause severe pain and paralysis. This experience must be completed twenty times for boys to be considered "warriors".[77]

Other harmful traditional practices include marriage by abduction, ritualized sexual slavery (Devadasi, Trokosi), breast ironing and widow inheritance.[78][79][80][81]

Female genital mutilation

UNFPA and UNICEF regard the practice of female genital mutilation as "a manifestation of deeply entrenched gender inequality. It persists for many reasons. In some societies, for example, it is considered a rite of passage. In others, it is seen as a prerequisite for marriage. In some communities – whether Christian, Jewish, Muslim – the practice may even be attributed to religious beliefs."[82]

An estimated 125 million women and girls living today have undergone FGM in the 29 countries where data exist. Of these, about half live in Egypt and Ethiopia.[83] It is most commonly carried out on girls between infancy and 15 years old.[73]

Forced marriage and child marriage

Early marriage, child marriage or forced marriage is prevalent in parts of Asia and Africa. The majority of victims seeking advice are female and aged between 18 and 23.[73] Such marriages can have harmful effects on a girl's education and development, and may expose girls to social isolation or abuse.[74][84][85]

The 2013 UN Resolution on Child, Early and Forced Marriage calls for an end to the practice, and states that "Recognizing that child, early and forced marriage is a harmful practice that violates abuses, or impairs human rights and is linked to and perpetuates other harmful practices and human rights violations, that these violations have a disproportionately negative impact on women and girls [...]".[86] Despite a near-universal commitment by governments to end child marriage, "one in three girls in developing countries (excluding China) will probably be married before they are 18."[87] UNFPA states that, "over 67 million women 20–24 year old in 2010 had been married as girls. Half were in Asia, one-fifth in Africa. In the next decade 14.2 million girls under 18 will be married every year; this translates into 39,000 girls married each day. This will rise to an average of 15.1 million girls a year, starting in 2021 until 2030, if present trends continue."[87]

Bride price

Bride price (also called bridewealth or bride token) is money, property, or other form of wealth paid by a groom or his family to the parents of the bride. This custom often leads to women having reduced ability to control their fertility. For instance, in northern Ghana, the payment of bride price signifies a woman's requirement to bear children, and women using birth control face threats, violence and reprisals.[88] The custom of bride price has been criticized as contributing to the mistreatment of women in marriage, and preventing them from leaving abusive marriages. UN Women recommended its abolition, and stated that: "Legislation should ... State that divorce shall not be contingent upon the return of bride price but such provisions shall not be interpreted to limit women's right to divorce; State that a perpetrator of domestic violence, including marital rape, cannot use the fact that he paid bride price as a defence to a domestic violence charge."[44]

The custom of bride price can also curtail the free movement of women: if a wife wants to leave her husband, he may demand back the bride price that he had paid to the woman's family; and the woman's family often cannot or does not want to pay it back, making it difficult for women to move out of violent husbands' homes.[89][90][91]

Economy and public policy

Economic empowerment of women

Promoting gender equality is seen as an encouragement to greater economic prosperity.[25][xxii] Female economic activity is a common measure of gender equality in an economy.[xxiii]

Gender discrimination often results in women obtaining low-wage jobs and being disproportionately affected by poverty, discrimination and exploitation.[93][xxiv] A growing body of research documents what works to economically empower women, from providing access to formal financial services to training on agricultural and business management practices, though more research is needed across a variety of contexts to confirm the effectiveness of these interventions.[94]

Gender biases also exist in product and service provision.[95] The term "Women's Tax", also known as "Pink Tax", refers to gendered pricing in which products or services marketed to women are more expensive than similar products marketed to men. Gender-based price discrimination involves companies selling almost identical units of the same product or service at comparatively different prices, as determined by the target market. Studies have found that women pay about $1,400 a year more than men due to gendered discriminatory pricing. Although the "pink tax" of different goods and services is not uniform, overall women pay more for commodities that result in visual evidence of feminine body image.[96][xxv]

In addition, gender wage gap is a phenomenon of gender biases. That means women do the same job or work with their male counterpart, but they could not receive the same salary or opportunity at workforce.[4] Across the European Union, for example, since women continue to hold lower-paying jobs, they earn 13% less than men on average. According to European Quality of Life Survey and European Working Conditions Survey data, women in the European Union work more hours but for less pay. Adult men (including the retired) work an average of 23 hours per week, compared to 15 hours for women.

Women continue to earn around 25% less than males. Almost a billion women are unable to obtain loans to establish a company or create a bank account in order to save money.[97][98] Increasing women's equality in banking and the workplace might boost the global economy by up to $28 trillion by 2025.[99][97][98][100] Funding is becoming more available for this, for example with the European Investment Bank establishing the SheInvest program in 2020 with the goal of raising €1 billion in investments to assist women in obtaining loans and running enterprises across Africa.[99][101]

The European Investment Bank funded an additional €2 billion in gender-lens investment in Africa, Asia, and Latin America at the Finance in Common Summit at the end of 2022.[99][102][103]

Gendered arrangements of work and care

Since the 1950s, social scientists as well as feminists have increasingly criticized gendered arrangements of work and care and the male breadwinner role. Policies are increasingly targeting men as fathers as a tool of changing gender relations.[104] Shared earning/shared parenting marriage, that is, a relationship where the partners collaborate at sharing their responsibilities inside and outside of the home, is often encouraged in Western countries.[105]

Western countries with a strong emphasis on women fulfilling the role of homemakers, rather than a professional role, include parts of German speaking Europe (i.e. parts of Germany, Austria and Switzerland); as well as the Netherlands and Ireland.[xxvi][xxvii][xxviii][xxix] In the computer technology world of Silicon Valley in the United States, New York Times reporter Nellie Bowles has covered harassment and bias against women as well as a backlash against female equality.[106][107]

Females are underrepresented in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) at all levels of society. Fewer females are completing STEM school subjects, graduating with STEM degrees, being employed as STEM professionals, and holding senior leadership and academic positions in STEM. This problem is exacerbated by the gender pay gap; family role expectations; lack of visible role models or mentors; discrimination and harassment; and bias in hiring and promotion practices.[108]

A key issue towards insuring gender equality in the workplace is the respecting of maternity rights and reproductive rights of women.[109] Different countries have different rules regarding maternity leave, paternity leave and parental leave.[xxx] Another important issue is ensuring that employed women are not de jure or de facto prevented from having a child.[xxxi] In some countries, employers ask women to sign formal or informal documents stipulating that they will not get pregnant or face legal punishment.[110] Women often face severe violations of their reproductive rights at the hands of their employers; and the International Labour Organization classifies forced abortion coerced by the employer as labour exploitation.[111][xxxii] Other abuses include routine virginity tests of unmarried employed women.[112][113]

Gendered arrangements of conscription

Military and conscription has been historically generally gender inequal.[114][115] Increasingly women are included in the military.[116] Currently only a few countries in the world, including Norway and Sweden, have gender-equal formal rules for conscription.[117] Gender Equality Indices have been criticized for neglecting conscription as a source of formal gender inequality.[118]

Freedom of movement

The degree to which women can participate (in law and in practice) in public life varies by culture and socioeconomic characteristics. Seclusion of women within the home was a common practice among the upper classes of many societies, and this still remains the case today in some societies. Before the 20th century it was also common in parts of Southern Europe, such as much of Spain.[119]

Women's freedom of movement continues to be legally restricted in some parts of the world. This restriction is often due to marriage laws.[xxxiii] In some countries, women must legally be accompanied by their male guardians (such as the husband or male relative) when they leave home.[120]

The Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) states at Article 15 (4) that:

4. States Parties shall accord to men and women the same rights with regard to the law relating to the movement of persons and the freedom to choose their residence and domicile.[121]

In addition to laws, women's freedom of movement is also restricted by social and religious norms.[xxxiv] Restrictions on freedom of movement also exist due to traditional practices such as baad, swara, or vani.[xxxv]

Girls' access to education

In many parts of the world, girls' access to education is very restricted. In developing parts of the world women are often denied opportunities for education as girls and women face many obstacles. These include: early and forced marriages; early pregnancy; prejudice based on gender stereotypes at home, at school and in the community; violence on the way to school, or in and around schools; long distances to schools; vulnerability to the HIV epidemic; school fees, which often lead to parents sending only their sons to school; lack of gender sensitive approaches and materials in classrooms.[123][124][125] According to OHCHR, there have been multiple attacks on schools worldwide during the period 2009–2014 with "a number of these attacks being specifically directed at girls, parents and teachers advocating for gender equality in education".[126] The United Nations Population Fund says:[127]

About two thirds of the world's illiterate adults are women. Lack of an education severely restricts a woman's access to information and opportunities. Conversely, increasing women's and girls' educational attainment benefits both individuals and future generations. Higher levels of women's education are strongly associated with lower infant mortality and lower fertility, as well as better outcomes for their children.

According to UNESCO, extreme exclusion still characterizes some countries, and pockets of exclusion remain in others. In Afghanistan, where girls have been banned again from secondary schools, there had been rapid progress in completion rates. For example, girls' primary completion increased from 8% in 2000 to 56% in 2020, although the gender gap remained at 20 percentage points. In some provinces, such as Uruzgan, just 1% of girls completed primary in 2015. A 20 percentage point gender gap in access to upper secondary education is also observed in sub-Saharan African countries, including Chad and Guinea.[128]

Political participation of women

Women are underrepresented in most countries' National Parliaments.[129] The 2011 UN General Assembly resolution on women's political participation called for female participation in politics, and expressed concern about the fact that "women in every part of the world continue to be largely marginalized from the political sphere".[130][xxxvi] Only 22 percent of parliamentarians globally are women and therefore, men continue to occupy most positions of political and legal authority.[6] As of November 2014, women accounted for 28% of members of the single or lower houses of parliaments in the European Union member states.[XXXVII]

In some Western countries[which?] women have only recently[when?] obtained the right to vote.[xxxvii]

In 2015, 61.3% of Rwanda's Lower House of Parliament were women, the highest proportion anywhere in the world, but worldwide that was one of only two such bodies where women were in the majority, the other being Bolivia's Lower House of Parliament.[132] (See also Gender equality in Rwanda).

Marriage, divorce and property laws and regulations

Equal rights for women in marriage, divorce, and property/land ownership and inheritance are essential for gender equality. The Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) has called for the end of discriminatory family laws.[133] In 2013, UN Women stated that "While at least 115 countries recognize equal land rights for women and men, effective implementation remains a major challenge".[134]

The legal and social treatment of married women has been often discussed as a political issue from the 19th century onwards.[xxxviii][xxxix] Until the 1970s, legal subordination of married women was common across European countries, through marriage laws giving legal authority to the husband, as well as through marriage bars.[xl][xli] In 1978, the Council of Europe passed the Resolution (78) 37 on equality of spouses in civil law.[135] Switzerland was one of the last countries in Europe to establish gender equality in marriage, in this country married women's rights were severely restricted until 1988, when legal reforms providing for gender equality in marriage, abolishing the legal authority of the husband, come into force (these reforms had been approved in 1985 by voters in a referendum, who narrowly voted in favor with 54.7% of voters approving).[136][137][138][139] In the Netherlands, it was only in 1984 that full legal equality between husband and wife was achieved: prior to 1984 the law stipulated that the husband's opinion prevailed over the wife's regarding issues such as decisions on children's education and the domicile of the family.[140][141][142]

In the United States, a wife's legal subordination to her husband was fully ended by the case of Kirchberg v. Feenstra, 450 U.S. 455 (1981), a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court held a Louisiana Head and Master law, which gave sole control of marital property to the husband, unconstitutional.[143]

There have been and sometimes continue to be unequal treatment of married women in various aspects of everyday life. For example, in Australia, until 1983 a husband had to authorize an application for an Australian passport for a married woman.[144] Other practices have included, and in many countries continue to include, a requirement for a husband's consent for an application for bank loans and credit cards by a married woman, as well as restrictions on the wife's reproductive rights, such as a requirement that the husband consents to the wife's acquiring contraception or having an abortion.[145][146] In some places, although the law itself no longer requires the consent of the husband for various actions taken by the wife, the practice continues de facto, with the authorization of the husband being asked in practice.[147]

Although dowry is today mainly associated with South Asia, the practice has been common until the mid-20th century in parts of Southeast Europe.[xlii]

Laws regulating marriage and divorce continue to discriminate against women in many countries.[xliii] In Iraq husbands have a legal right to "punish" their wives, with paragraph 41 of the criminal code stating that there is no crime if an act is committed while exercising a legal right.[xliv] In the 1990s and the 21st century there has been progress in many countries in Africa: for instance in Namibia the marital power of the husband was abolished in 1996 by the Married Persons Equality Act; in Botswana it was abolished in 2004 by the Abolition of Marital Power Act; and in Lesotho it was abolished in 2006 by the Married Persons Equality Act.[148] Violence against a wife continues to be seen as legally acceptable in some countries; for instance in 2010, the United Arab Emirates Supreme Court ruled that a man has the right to physically discipline his wife and children as long as he does not leave physical marks.[149] The criminalization of adultery has been criticized as being a prohibition, which, in law or in practice, is used primarily against women; and incites violence against women (crimes of passion, honor killings).[xlv]

Social and ideological

Political gender equality

Two recent movements in countries with large Kurdish populations have implemented political gender equality. One has been the Kurdish movement in southeastern Turkey led by the Democratic Regions Party (DBP) and the Peoples' Democratic Party (HDP), from 2006 or before. The mayorships of 2 metropolitan areas and 97 towns[citation needed] are led jointly by a man and a woman, both called co-mayors. Party offices are also led by a man and a woman. Local councils were formed, which also had to be co-presided over by a man and a woman together. However, in November 2016 the Turkish government cracked down on the HDP, jailing ten of its members of Parliament, including the party's male and female co-leaders.[150]

A movement in northern Syria, also Kurdish, has been led by the Democratic Union Party (PYD).[151] In northern Syria all villages, towns and cities governed by the PYD were co-governed by a man and a woman. Local councils were formed where each sex had to have 40% representation, and minorities also had to be represented.[151]

Gender stereotypes

Gender stereotypes arise from the socially approved roles of women and men in the private or public sphere, at home or in the workplace. In the household, women are typically seen as mother figures, which usually places them into a typical classification of being "supportive" or "nurturing". Women are expected to want to take on the role of a mother and take on primary responsibility for household needs.[152] Their male counterparts are seen as being "assertive" or "ambitious" as men are usually seen in the workplace or as the primary breadwinner for his family.[153] Due to these views and expectations, women often face discrimination in the public sphere, such as the workplace.[153] Women are stereotyped to be less productive at work because they are believed to focus more on family when they get married or have children.[154] A gender role is a set of societal norms dictating the types of behaviors which are generally considered acceptable, appropriate, or desirable for people based on their sex. Gender roles are usually centered on conceptions of femininity and masculinity, although there are exceptions and variations.

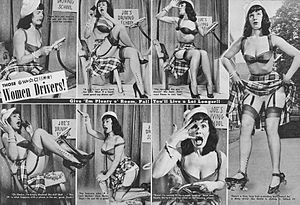

Portrayal of women in the media

The way women are represented in the media has been criticized as perpetuating negative gender stereotypes. The exploitation of women in mass media refers to the criticisms that are levied against the use or objectification of women in the mass media, when such use or portrayal aims at increasing the appeal of media or a product, to the detriment of, or without regard to, the interests of the women portrayed, or women in general. Concerns include the fact that all forms of media have the power to shape the population's perceptions and portray images of unrealistic stereotypical perceptions by portraying women either as submissive housewives or as sex objects.[155] The media emphasizes traditional domestic or sexual roles that normalize violence against women. The vast array of studies that have been conducted on the issue of the portrayal of women in the media have shown that women are often portrayed as irrational, fragile, not intelligent, submissive and subservient to men.[156] Research has shown that stereotyped images such as these have been shown to negatively impact on the mental health of many female viewers who feel bound by these roles, causing amongst other problems, self-esteem issues, depression and anxiety.[156]

According to a study, the way women are often portrayed by the media can lead to: "Women of average or normal appearance feeling inadequate or less beautiful in comparison to the overwhelming use of extraordinarily attractive women"; "Increase in the likelihood and acceptance of sexual violence"; "Unrealistic expectations by men of how women should look or behave"; "Psychological disorders such as body dysmorphic disorder, anorexia, bulimia and so on"; "The importance of physical appearance is emphasized and reinforced early in most girls' development." Studies have found that nearly half of females ages six–eight have stated they want to be slimmer. (Striegel-Moore & Franko, 2002)".[157][158]

Statistics on women's representation in the media

- Women have won only a quarter of Pulitzer prizes for foreign reporting and only 17 per cent of awards of the Martha Gellhorn Prize for Journalism.[159] In 2015 the African Development Bank began sponsoring a category for Women's Rights in Africa, designed to promote gender equality through the media, as one of the prizes awarded annually by One World Media.[160]

- Created in 1997, the UNESCO/Guillermo Cano World Press Freedom Prize is an annual award that honors a person, organization or institution that has made a notable contribution to the defense and/or promotion of press freedom anywhere in the world. Nine out of 20 winners have been women.[161]

- The Poynter Institute since 2014 has been running a Leadership Academy for Women in Digital Media, expressly focused on the skills and knowledge needed to achieve success in the digital media environment.

- The World Association of Newspapers and News Publishers (WAN-IFRA), which represents more than 18,000 publications, 15,000 online sites and more than 3,000 companies in more than 120 countries, leads the Women in the News (WIN) campaign together with UNESCO as part of their Gender and Media Freedom Strategy. In their 2016 handbook, WINing Strategies: Creating Stronger Media Organizations by Increasing Gender Diversity, they highlight a range of positive action strategies undertaken by a number of their member organizations from Germany to Jordan to Colombia, with the intention of providing blueprints for others to follow.[162]

Informing women of their rights

While in many countries, the problem lies in the lack of adequate legislation, in others the principal problem is not as much the lack of a legal framework, but the fact that most women do not know their legal rights. This is especially the case as many of the laws dealing with women's rights are of recent date. This lack of knowledge enables to abusers to lead the victims (explicitly or implicitly) to believe that their abuse is within their rights. This may apply to a wide range of abuses, ranging from domestic violence to employment discrimination.[163][164] The United Nations Development Programme states that, in order to advance gender justice, "Women must know their rights and be able to access legal systems".[165]

The 1993 UN Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women states at Art. 4 (d) [...] "States should also inform women of their rights in seeking redress through such mechanisms".[166] Enacting protective legislation against violence has little effect, if women do not know how to use it: for example a study of Bedouin women in Israel found that 60% did not know what a restraining order was;[167] or if they do not know what acts are illegal: a report by Amnesty International showed in Hungary, in a public opinion poll of nearly 1,200 people in 2006, a total of 62% did not know that marital rape was an illegal (it was outlawed in 1997) and therefore the crime was rarely reported.[168][169] Ensuring women have a minimum understanding of health issues is also important: lack of access to reliable medical information and available medical procedures to which they are entitled hurts women's health.[170]

Gender mainstreaming

Gender mainstreaming is described as the public policy of assessing the different implications for women and men of any planned policy action, including legislation and programmes, in all areas and levels, with the aim of achieving gender equality.[171][172] The concept of gender mainstreaming was first proposed at the 1985 Third World Conference on Women in Nairobi, Kenya. The idea has been developed in the United Nations development community.[173] Gender mainstreaming "involves ensuring that gender perspectives and attention to the goal of gender equality are central to all activities".[174]

According to the Council of Europe definition: "Gender mainstreaming is the (re)organization, improvement, development and evaluation of policy processes, so that a gender equality perspective is incorporated in all policies at all levels and at all stages, by the actors normally involved in policy-making."[131]

An integrated gender mainstreaming approach is "the attempt to form alliances and common platforms that bring together the power of faith and gender-equality aspirations to advance human rights."[175] For example, "in Azerbaijan, UNFPA conducted a study on gender equality by comparing the text of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women with some widely recognized Islamic references and resources. The results reflect the parallels between the Convention and many tenets of Islamic scripture and practice. The study showcased specific issues, including VAW, child marriage, respect for the dignity of women, and equality in the economic and political participation of women. The study was later used to produce training materials geared towards sensitizing religious leaders."[175]

Gender biases

A study involving predicting personality characteristics of individuals in photographs across 44 countries found that the women-are-wonderful effect is lower in countries with high measures of gender equality, with the decrease arising from men being viewed less negatively.[179] The gender-equality paradox is the observation that gendered differences in personality tend to be higher in countries with higher gender equality.[180]

Criticism

There has been criticism from some feminists towards the political discourse and policies employed in order to achieve the above items of "progress" in gender equality, with critics arguing that these gender equality strategies are superficial, in that they do not seek to challenge social structures of male domination, and only aim to improve the situation of women within the societal framework of subordination of women to men,[181] and that official public policies (such as state policies or international bodies policies) are questionable, as they are applied in a patriarchal context, and are directly or indirectly controlled by agents of a system which is for the most part male.[182] One of the criticisms of the gender equality policies, in particular, those of the European Union, is that they disproportionately focus on policies integrating women in public life, but do not seek to genuinely address the deep private sphere oppression.[183] A criticism of the Western concept and policies of gender equality relates to the degree to which this approach is able to genuinely address in a successful way the problem of violence against women.[184][185][186][187][188][189]

A further criticism is that a focus on the situation of women in non-Western countries, while often ignoring the issues that exist in the West, is a form of imperialism and of reinforcing Western moral superiority; and a way of "othering" of domestic violence, by presenting it as something specific to outsiders – the "violent others" – and not to the allegedly progressive Western cultures.[190] These critics point out that women in Western countries often face similar problems, such as domestic violence and rape, as in other parts of the world.[191] They also cite the fact that women faced de jure legal discrimination until just a few decades ago; for instance, in some Western countries such as Switzerland, Greece, Spain, and France, women obtained equal rights in family law in the 1980s.[xlvi][xlvii][xlviii][xlix] Another criticism is that there is a selective public discourse with regard to different types of oppression of women, with some forms of violence such as honor killings (most common in certain geographic regions such as parts of Asia and North Africa) being frequently the object of public debate, while other forms of violence, such as the lenient punishment for crimes of passion across Latin America, do not receive the same attention in the West.[192][l] It is also argued that the criticism of particular laws of many developing countries ignores the influence of colonialism on those legal systems.[li] There has been controversy surrounding the concepts of Westernization and Europeanisation, due to their reminder of past colonialism,[193] and also due to the fact that some Western countries, such as Switzerland, have been themselves been very slow to give women legal rights.[194][195] There have also been objections to the way Western media presents women from various cultures creating stereotypes, such as that of 'submissive' Asian or Eastern European women, a stereotype closely connected to the mail order brides industry.[196] Such stereotypes are often blatantly untrue: for instance women in many Eastern European countries occupy a high professional status.[197][198] Feminists in many developing countries have been strongly opposed to the idea that women in those countries need to be 'saved' by the West.[199] There are questions on how exactly should gender equality be measured, and whether the West is indeed "best" at it: a study in 2010 found that among the top 20 countries on female graduates in the science fields at university level most countries were countries that were considered internationally to score very low on the position of women's rights, with the top 3 being Iran, Saudi Arabia and Oman, and only 5 European countries made it to that top: Romania, Bulgaria, Italy, Georgia and Greece.[200]

Controversy regarding Western cultural influence in the world is not new; in the late 1940s, when the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was being drafted, the American Anthropological Association warned that the document would be defining universal rights from a Western perspective which could be detrimental to non-Western countries, and further argued that the West's history of colonialism and forceful interference with other societies made them a problematic moral representative for universal global standards.[201]

There has been criticism that international law, international courts, and universal gender neutral concepts of human rights are at best silent on many of the issues important to women and at worst male centered; considering the male person to be the default.[202] Excessive gender neutrality can worsen the situation of women, because the law assumes women are in the same position as men, ignoring the biological fact that in the process of reproduction and pregnancy there is no 'equality', and that apart from physical differences there are socially constructed limitations which assign a socially and culturally inferior position to women – a situation which requires a specific approach to women's rights, not merely a gender neutral one.[203] In a 1975 interview, Simone de Beauvoir talked about the negative reactions towards women's rights from the left that was supposed to be progressive and support social change, and also expressed skepticism about mainstream international organizations.[204] There have been questions about the acceptability of international intervention into societal domestic issues from international organizations,[205] especially since the multitude of such international bodies can create confusion, including through contradictory rulings on the same issue: for example the ECtHR upheld in 2014 France's ban on wearing a burqa in public,[206] while the United Nations Human Rights Committee concluded in 2018 that France's ban on burqa in public violates human rights.[207] International bodies have been criticized for being based on an ideology of one size fits all approach to issues, which does not take into account that a specific approach may work in one culture but not in another,[208][209] and that historically international intervention into another country has often done more harm than good; and that ultimately the problems from a culture must be solved from within that culture, not through forceful foreign intervention.[210] A criticism of international organizations is that while they purport to support universal global human rights, they often support the interests of Western elites.[211] The legitimacy of international organizations has come into question in the 21st century especially in the light of international scandals, such as child sexual abuse by UN peacekeepers.[212]

See also

General issues

- Coloniality of gender

- Egalitarianism

- Equal opportunity

- Gender discrimination

- Gender empowerment

- Masculism

- Men's rights

- Sex and gender distinction

- Sexism

- Sex industry

- Sex ratio

- Special measures for gender equality in the United Nations

Specific issues

- Baháʼí Faith and gender equality

- Female education

- Gender Parity Index (in education)

- Gender polarization

- Gender sensitization

- Matriarchy

- Matriname

- Mixed-sex education

- Patriarchy

- Quaker Testimony of Equality

- Shared parenting (after divorce)

- Women in Islam

Laws

- 2009 Danish Act of Succession referendum

- Anti-discrimination law

- Equal Pay Act of 1963 (United States)

- Equal Protection Clause (United States)

- Equality Act 2006 (UK)

- Equality Act 2010 (UK)

- Equality Act (United States)

- European charter for equality of women and men in local life

- Gender Equality Duty in Scotland

- Gender Equity Education Act (Taiwan)

- Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act (United States, 2009)

- List of gender equality lawsuits

- Paycheck Fairness Act (in the US)

- Sex Discrimination Act 1975 (UK)

- Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 (United States)

- Uniform civil code (India)

- Women's Petition to the National Assembly (France, 1789)

Organizations and ministries

- Afghan Ministry of Women Affairs (Afghanistan)

- Christians for Biblical Equality, an organization that opposes gender discrimination within the church

- Committee on Women's Rights and Gender Equality (European Parliament)

- Equal Opportunities Commission (United Kingdom)

- Gender Empowerment Measure, a metric used by the United Nations

- Gender-related Development Index, a metric used by the United Nations

- The Girl Effect, an organization to help girls, worldwide, toward ending poverty

- Government Equalities Office (UK)

- International Center for Research on Women

- Ministry of Integration and Gender Equality (Sweden)

- Ministry of Women, Family and Community Development (Malaysia)

- Philippine Commission on Women (Philippines)

- UN Women, United Nations entity working for the empowerment of women

Other related topics

- Gender apartheid

- Global Gender Gap Report

- Illustrators for Gender Equality

- International Men's Day

- Potty parity

- Tampon tax

- Women's Equality Day

- Transgender

- Theaology, Feminine divine

Notes

- ^ The ILO similarly defines gender equality as "the enjoyment of equal rights, opportunities and treatment by men and women and by boys and girls in all spheres of life"

- ^ Although the Peruvian constitution and the government itself state that the President is the Head of Government,[213][214] other sources name the President of the Council of Ministers as the head of government.[215]

- ^ Including female representatives of heads of state, such as Governors-General and French Representatives of Andorra

- ^ For example, many countries now permit women to serve in the armed forces, the police forces and to be fire fighters – occupations traditionally reserved for men. Although these continue to have a male majority, an increasing number of women are now active, especially in directive fields such as politics, and occupy high positions in business.

- ^ For example, the Cairo Declaration on Human Rights in Islam declared that women have equal dignity but not equal rights, and this was accepted by many predominantly Muslim countries.

- ^ In some Christian churches, the practice of churching of women may still have elements of ritual purification and the Ordination of women to the priesthood may be restricted or forbidden.

- ^ An example is Finland, which has offered very high opportunities to women in public/professional life but has had a weak legal approach to the issue of violence against women, with the situation in this country having been called a paradox.[I][II] "Finland is repeatedly reminded of its widespread problem of violence against women and recommended to take more efficient measures to deal with the situation. International criticism concentrates on the lack of measures to combat violence against women in general and in particular on the lack of a national action plan to combat such violence and on the lack of legislation on domestic violence. (...) Compared to Sweden, Finland has been slower to reform legislation on violence against women. In Sweden, domestic violence was already illegal in 1864, while in Finland such violence was not outlawed until 1970, over a hundred years later. In Sweden the punishment of victims of incest was abolished in 1937 but not until 1971 in Finland. Rape within marriage was criminalised in Sweden in 1962, but the equivalent Finnish legislation only came into force in 1994 — making Finland one of the last European countries to criminalise marital rape. In addition, assaults taking place on private property did not become impeachable offences in Finland until 1995. Only in 1997 did victims of sexual offences and domestic violence in Finland become entitled to government-funded counselling and support services for the duration of their court cases."[III]

- ^ Denmark received harsh criticism for inadequate laws in regard to sexual violence in a 2008 report produced by Amnesty International,[III] which described Danish laws as "inconsistent with international human rights standards".[IV] This led to Denmark reforming its sexual offenses legislation in 2013.[V][VI][VII]

- ^ "Mainstreaming a gender perspective is the process of assessing the implications for women and men of any planned action, including legislation, policies or programmes, in all areas and at all levels. It is a strategy for making women's as well as men's concerns and experiences an integral dimension of the design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of policies and programmes in all political, economic and societal spheres so that women and men benefit equally and inequality is not perpetuated. The ultimate goal is to achieve gender equality."[VIII]

- ^ Forms of violence against women include Sexual violence (including War Rape, Marital rape, Date rape by drugs or alcohol, and Child sexual abuse, the latter often in the context of Child marriage), Domestic violence, Forced marriage, Female genital mutilation, Forced prostitution, Sex trafficking, Honor killing, Dowry killing, Acid attacks, Stoning, Flogging, Forced sterilisation, Forced abortion, violence related to accusations of witchcraft, mistreatment of widows (e.g. widow inheritance). Fighting against violence against women is considered a key issue for achieving gender equality. The Council of Europe adopted the Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence (Istanbul Convention).

- ^ The UN Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women defines violence against women as "any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual or psychological harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or in private life" and states that:"violence against women is a manifestation of historically unequal power relations between men and women, which have led to domination over and discrimination against women by men and to the prevention of the full advancement of women, and that violence against women is one of the crucial social mechanisms by which women are forced into a subordinate position compared with men."[IX]

- ^ As of 2004–2009, former and current partners were responsible for more than 80% of all cases of murders of women in Cyprus, France, and Portugal.[43]

- ^ According to UNFPA:[X]

- "In some developing countries, practices that subjugate and harm women – such as wife-beating, killings in the name of honour, female genital mutilation/cutting and dowry deaths – are condoned as being part of the natural order of things."

- ^ In its explanatory report at para 219, it states:

- "There are many examples from past practice in Council of Europe member states that show that exceptions to the prosecution of such cases were made, either in law or in practice, if victim and perpetrator were, for example, married to each other or had been in a relationship. The most prominent example is rape within marriage, which for a long time had not been recognised as rape because of the relationship between victim and perpetrator."[XI]

- ^ In Opuz v Turkey, the European Court of Human Rights recognized violence against women as a form discrimination against women: "[T]he Court considers that the violence suffered by the applicant and her mother may be regarded as gender-based violence which is a form of discrimination against women."[XII] This is also the position of the Istanbul Convention which reads:"Article 3 – Definitions, For the purpose of this Convention: a "violence against women" is understood as a violation of human rights and a form of discrimination against women [...]".[XIII]

- ^ She writes "To know what is wrong with rape, know what is right about sex. If this, in turn, is difficult, the difficulty is as instructive as the difficulty men have in telling the difference when women see one. Perhaps the wrong of rape has proved so difficult to define because the unquestionable starting point has been that rape is defined as distinct from intercourse, while for women it is difficult to distinguish the two under conditions of male dominance."[XIV]

- ^ According to the World Health Organization: "Sexual violence is also more likely to occur where beliefs in male sexual entitlement are strong, where gender roles are more rigid, and in countries experiencing high rates of other types of violence."[XV]