African American founding fathers of the United States: Difference between revisions

Randy Kryn (talk | contribs) →Reconstruction as Second Founding of the United States: added self-cite for Bevel addition |

No edit summary Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit Advanced mobile edit |

||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

According to Professors [[Jeffrey K. Tulis]] and Nicole Mellow:<ref>Jeffrey K. Tulis and Nicole Mellow, ''Legacies of losing in American politics'' (U of Chicago Press, 2018), p. 2. - </ref><blockquote> The Founding, Reconstruction (often called “the second founding”), and the New Deal are typically heralded as the most significant turning points in the country’s history, with many observers seeing each of these as political triumphs through which the United States has come to more closely realize its liberal ideals of liberty and equality.</blockquote> |

According to Professors [[Jeffrey K. Tulis]] and Nicole Mellow:<ref>Jeffrey K. Tulis and Nicole Mellow, ''Legacies of losing in American politics'' (U of Chicago Press, 2018), p. 2. - </ref><blockquote> The Founding, Reconstruction (often called “the second founding”), and the New Deal are typically heralded as the most significant turning points in the country’s history, with many observers seeing each of these as political triumphs through which the United States has come to more closely realize its liberal ideals of liberty and equality.</blockquote> |

||

Scholars such as [[Eric Foner]] have recently expanded the theme into full-length books.<ref>Eric Foner, ''The Second Founding: How the Civil War and Reconstruction Remade the Constitution'' (2020) [https://www.amazon.com/Second-Founding-Reconstruction-Remade-Constitution/dp/0393358526/ excerpt]</ref><ref>Ilan Wurman, ''The Second Founding: An Introduction to the Fourteenth Amendment'' ( 2020) [https://www.amazon.com/Second-Founding-Introduction-Fourteenth-Amendment/dp/1108843158/ excerpt]</ref><ref>See also Garrett Epps, "Second Founding: The Story of the Fourteenth Amendment." ''Oregon Law Review'' 85 (2006) pp: 895-911 [https://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1239&context=all_fac online]. </ref> Black abolitionists played a key role by stressing that freed blacks needed equal rights after slavery was abolished.<ref> David Hackett Fischer, ''African Founders: How Enslaved People Expanded American Ideals'' (Simon and Schuster, 2022) pp 1-3.[https://www.amazon.com/African-Founders-Enslaved-Expanded-American/dp/1982145099/ excerpt] |

Scholars such as [[Eric Foner]] have recently expanded the theme into full-length books.<ref>Eric Foner, ''The Second Founding: How the Civil War and Reconstruction Remade the Constitution'' (2020) [https://www.amazon.com/Second-Founding-Reconstruction-Remade-Constitution/dp/0393358526/ excerpt]</ref><ref>Ilan Wurman, ''The Second Founding: An Introduction to the Fourteenth Amendment'' ( 2020) [https://www.amazon.com/Second-Founding-Introduction-Fourteenth-Amendment/dp/1108843158/ excerpt]</ref><ref>See also Garrett Epps, "Second Founding: The Story of the Fourteenth Amendment." ''Oregon Law Review'' 85 (2006) pp: 895-911 [https://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1239&context=all_fac online]. </ref> Black abolitionists played a key role by stressing that freed blacks needed equal rights after slavery was abolished.<ref> David Hackett Fischer, ''African Founders: How Enslaved People Expanded American Ideals'' (Simon and Schuster, 2022) pp 1-3.[https://www.amazon.com/African-Founders-Enslaved-Expanded-American/dp/1982145099/ excerpt] |

||

</REF> Constitutional provision for racial equality for free blacks was enacted by a Congress led by [[Thaddeus Stevens]], [[Charles Sumner]] and [[Lyman Trumbull]].<ref> Paul Rego, ''Lyman Trumbull and the Second Founding of the United States'' (University Press of Kansas, 2022) pp. 1–2. [https://www.amazon.com/Trumbull-Founding-American-Political-Thought/dp/0700633499/ excerpt]. </ref> The "second founding" comprised the 13th, 14th and 15th amendments to the Constitution. All citizens now had federal rights that could be enforced in federal court. In a deep reaction, after 1876 freedmen lost many of these rights and had second class citizenship in the era of lynching and [[Jim Crow laws]]. Finally in the 1950s the U.S, Supreme Court started to restore those rights. Under the public leadership of [[Martin Luther King]], president of the [[Southern Christian Leadership Council]], and the strategies of SCLC's Director of Direct Action, [[James Bevel]], the [[Civil Rights movement]] made the nation aware of the crisis, and under [[Presidency of Lyndon B. Johnson|President Lyndon Johnson]] major civil rights legislation was passed in 1964, 1965, and 1968.<ref>Clay Risen, ''The Bill of the Century: The Epic Battle for the Civil Rights Act'' (2014) pp. 2–5. |

</REF> Constitutional provision for racial equality for free blacks was enacted by a Congress led by [[Thaddeus Stevens]], [[Charles Sumner]] and [[Lyman Trumbull]].<ref> Paul Rego, ''Lyman Trumbull and the Second Founding of the United States'' (University Press of Kansas, 2022) pp. 1–2. [https://www.amazon.com/Trumbull-Founding-American-Political-Thought/dp/0700633499/ excerpt]. </ref> The "second founding" comprised the 13th, 14th and 15th amendments to the Constitution. All citizens now had federal rights that could be enforced in federal court. In a deep reaction, after 1876 freedmen lost many of these rights and had second class citizenship in the era of lynching and [[Jim Crow laws]]. Finally in the 1950s the U.S, Supreme Court started to restore those rights. Under the public leadership of [[Martin Luther King]], president of the [[Southern Christian Leadership Council]], and the strategies of SCLC's Director of Direct Action, [[James Bevel]], the [[Civil Rights movement]] made the nation aware of the crisis, and under [[Presidency of Lyndon B. Johnson|President Lyndon Johnson]] major civil rights legislation was passed in 1964, 1965, and 1968.<ref>Clay Risen, ''The Bill of the Century: The Epic Battle for the Civil Rights Act'' (2014) pp. 2–5.</ref> |

||

==Organizations== |

==Organizations== |

||

| Line 63: | Line 63: | ||

| File:I too by Langston Hughes.png| alt1=Only $500 for a first edition later printing on eBay | [[Google Books]] scan of a 1974 microfilm of a [[University of Michigan Libraries]] copy of [[Langston Hughes]]' 1926 poetry collection ''[[Weary Blues]]''; lines from this poem are engraved on the wall of the [[National Museum of African American History and Culture]]<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/what-langston-hughes-powerful-poem-i-too-americas-past-present-180960552/|title=What Langston Hughes’ Powerful Poem “I, Too" Tells Us About America's Past and Present|first1=Smithsonian|last1=Magazine|first2=David C.|last2=Ward|website=Smithsonian Magazine}}</ref> |

| File:I too by Langston Hughes.png| alt1=Only $500 for a first edition later printing on eBay | [[Google Books]] scan of a 1974 microfilm of a [[University of Michigan Libraries]] copy of [[Langston Hughes]]' 1926 poetry collection ''[[Weary Blues]]''; lines from this poem are engraved on the wall of the [[National Museum of African American History and Culture]]<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/what-langston-hughes-powerful-poem-i-too-americas-past-present-180960552/|title=What Langston Hughes’ Powerful Poem “I, Too" Tells Us About America's Past and Present|first1=Smithsonian|last1=Magazine|first2=David C.|last2=Ward|website=Smithsonian Magazine}}</ref> |

||

| File:PollTaxRecieptJefferson1917.JPG| alt2=Poll tax receipt, Jefferson Parish, Louisiana |Sometimes the receipts are literal receipts; African Americans paid [[poll taxes]] designed to discourage them from exercising the franchise; poll taxes were prohibited in 1964 by the [[Twenty-fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution]] |

| File:PollTaxRecieptJefferson1917.JPG| alt2=Poll tax receipt, Jefferson Parish, Louisiana |Sometimes the receipts are literal receipts; African Americans paid [[poll taxes]] designed to discourage them from exercising the franchise; poll taxes were prohibited in 1964 by the [[Twenty-fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution]] |

||

| File:Isaac-Woodard-1946.jpg | [[Isaac Woodard]] served in World War II, had his eyes stolen from him by racist white Americans on the way home, and involuntarily galvanized the federal government to [[Executive Order 9981|desegregate the U.S. armed services]] |

| File:Isaac-Woodard-1946.jpg | [[Isaac Woodard]] served in World War II, had his eyes stolen from him by racist white Americans on the way home, and involuntarily galvanized the federal government to [[Executive Order 9981|desegregate the U.S. armed services]]; in Woodard's case (and countless others) the idea of the "black body as a site of resistance against racism"<ref>{{citation | doi=10.1353/mel.0.0061}}</ref> is most horrifyingly actualized}} |

||

}} |

|||

== See also == |

== See also == |

||

Revision as of 03:58, 24 February 2023

The African American founding fathers of the United States are the African Americans who worked to include the equality of all races as a fundamental principle of the United States of America. Beginning in the abolition movement of the 19th century, they worked for the abolition of slavery, and also for the abolition of second class status for free blacks. Their goals were temporarily realized in the late 1860s, with the passage of the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments to the United States Constitution. However, after Reconstruction ended in 1877, the gains were partly lost and an era of Jim Crow gave blacks reduced social, economic and political status. The recovery was achieved in the Civil Rights Movement, especially in the 1950s and 1960s, under the leadership of blacks like Martin Luther King and James Bevel and whites like the Supreme Court and President Lyndon Johnson. In the 21st century scholars have studied the African American founding fathers in depth.[1][2]

In the words of Nikole Hannah-Jones, "Despite being violently denied the freedom and justice promised to all, black Americans believed fervently in the American creed. Through centuries of black resistance and protest, we have helped the country live up to its founding ideals. And not only for ourselves — black rights struggles paved the way for every other rights struggle, including women’s and gay rights, immigrant and disability rights. Without the idealistic, strenuous and patriotic efforts of black Americans, our democracy today would most likely look very different — it might not be a democracy at all."[3]

Reconstruction as Second Founding of the United States

According to Professors Jeffrey K. Tulis and Nicole Mellow:[4]

The Founding, Reconstruction (often called “the second founding”), and the New Deal are typically heralded as the most significant turning points in the country’s history, with many observers seeing each of these as political triumphs through which the United States has come to more closely realize its liberal ideals of liberty and equality.

Scholars such as Eric Foner have recently expanded the theme into full-length books.[5][6][7] Black abolitionists played a key role by stressing that freed blacks needed equal rights after slavery was abolished.[8] Constitutional provision for racial equality for free blacks was enacted by a Congress led by Thaddeus Stevens, Charles Sumner and Lyman Trumbull.[9] The "second founding" comprised the 13th, 14th and 15th amendments to the Constitution. All citizens now had federal rights that could be enforced in federal court. In a deep reaction, after 1876 freedmen lost many of these rights and had second class citizenship in the era of lynching and Jim Crow laws. Finally in the 1950s the U.S, Supreme Court started to restore those rights. Under the public leadership of Martin Luther King, president of the Southern Christian Leadership Council, and the strategies of SCLC's Director of Direct Action, James Bevel, the Civil Rights movement made the nation aware of the crisis, and under President Lyndon Johnson major civil rights legislation was passed in 1964, 1965, and 1968.[10]

Organizations

Many black organizations promoted the goal of equality after 1865.[11]

NERL

The all-black National Equal Rights League} was founded in upstate New York in 1864 and had chapters across the North. [12][13][14]

NAACP

Activists

Historians in recent years have compiled directories of black leaders in the 19th century.[15][16]

Richard Allen

Bishop Richard Allen (1760-1831) was the founder of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the largest of the nation's all-black organizations. Elected the first bishop of the AME Church in 1816, Allen focused on organizing a denomination in which free Black people could worship without racial oppression and enslaved people could find a measure of dignity. He worked to upgrade the social status of the Black community, organizing Sabbath schools to teach literacy and promoting national organizations to develop political strategies.[17]

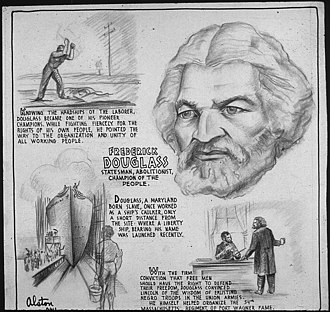

Frederick Douglass

According to biographer David Blight, Douglass, "played a pivotal role in America's Second Founding out of the apocalypse of the Civil War, and he very much wished to see himself as a founder and a defender of the Second American Republic."[18]

James Forten

James Forten (1766–1842) was an African-American abolitionist and wealthy businessman in Philadelphia. He used his wealth and social standing to work for civil rights for African Americans in both the city and nationwide. Beginning in 1817, he opposed the colonization movements, particularly that of the American Colonization Society. He affirmed African Americans' claim to a stake in the United States of America. He persuaded William Lloyd Garrison to adopt an anti-colonization position and helped fund his newspaper The Liberator (1831–1865), frequently publishing letters on public issues. He became vice-president of the biracial American Anti-Slavery Society, founded in 1833, and worked for national abolition of slavery. His large family was also devoted to these causes, and two daughters married the Purvis brothers, who used their wealth as leaders for abolition.[19]

Henry McNeal Turner

In 1863 during the American Civil War, Turner was appointed by the US Army as the first African-American chaplain in the United States Colored Troops. After the war, he was appointed to the Freedmen's Bureau in Georgia. He settled in Macon and was elected to the state legislature in 1868 during the Reconstruction era. An A.M.E. missionary, he also planted many AME churches in Georgia after the war. In 1880 he was elected as the first Southern bishop of the AME Church, after a fierce battle within the denomination because of its Northern roots.

Angered by the Democrats' regaining power and instituting Jim Crow laws in the late nineteenth century South, Turner began to support black nationalism and emigration of blacks to the African continent.

Ida B. Wells

Ida B. Wells (1862–1931) was an investigative journalist, educator, and leader in the civil rights movement. She was one of the founders (NAACP). Wells dedicated her lifetime to combating prejudice and violence, the fight for African-American equality, especially that of women, and became the most famous Black woman in the United States of her time. In the 1890s, Wells documented lynching in the United States in articles and through her pamphlets called Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in all its Phases, and The Red Record, investigating frequent claims of whites that lynchings were reserved for Black criminals only. Wells exposed lynching as a barbaric practice of whites in the South used to intimidate and oppress African Americans who created economic and political competition—and a subsequent threat of loss of power—for whites. Well's pamphlet set out to tell the truth behind the rising violence in the South against African Americans. At this time, the white press continued to paint the African Americans involved in the incident as villains and whites as innocent victims. [20]

Booker T. Washington

W.E.B. Du Bois

W. E. B. Du Bois (1868–1919) was an academic sociologist and activist. He rose to national prominence as a leader of the Niagara Movement, a group of African-American activists who wanted equal rights for blacks. Du Bois and his supporters opposed the Atlanta compromise, an agreement crafted by Booker T. Washington which provided that Southern blacks would work and submit to white political rule, while Southern whites guaranteed that blacks would receive basic educational and economic opportunities. Instead, Du Bois insisted on full civil rights and increased political representation, which he believed would be brought about by the African-American intellectual elite. He referred to this group as the Talented Tenth, a concept under the umbrella of racial uplift, and believed that African Americans needed the chances for advanced education to develop its leadership. He helped organize the NAACP as a counterweight to Washington's powerful grass roots organizations. Racism was the main target of Du Bois's polemics, and he strongly protested against lynching, Jim Crow laws, and discrimination in education and employment. His cause included people of color everywhere, particularly Africans and Asians in colonies. He was a proponent of Pan-Africanism and helped organize several Pan-African Congresses to fight for the independence of African colonies from European powers.[21]

Evaluating the First Founders

Thurgood Marshall was the first African American justice of the Supreme Court. At the 200th anniversary of the Constitution in 1987, he argued:[22]

I do not believe that the meaning of the Constitution was forever “fixed” at the Philadelphia Convention. Nor do I find the wisdom, foresight, and sense of justice exhibited by the framers particularly profound. To the contrary, the government they devised was defective from the start, requiring several amendments, a civil war, and momentous social transformations to attain the system of constitutional government, and its respect for the individual freedoms and human rights, we hold as fundamental today. When contemporary Americans cite "The Constitution," they invoke a concept that is vastly different from what the framers began to construct two centuries ago....While the Union survived the civil war, the Constitution did not. In its place arose a new, more promising basis for justice and equality, the 14th Amendment, ensuring protection of the life, liberty, and property of all persons against deprivations without due process, and guaranteeing equal protection of the laws.

Additional images

-

Google Books scan of a 1974 microfilm of a University of Michigan Libraries copy of Langston Hughes' 1926 poetry collection Weary Blues; lines from this poem are engraved on the wall of the National Museum of African American History and Culture[23]

-

Sometimes the receipts are literal receipts; African Americans paid poll taxes designed to discourage them from exercising the franchise; poll taxes were prohibited in 1964 by the Twenty-fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution

-

Isaac Woodard served in World War II, had his eyes stolen from him by racist white Americans on the way home, and involuntarily galvanized the federal government to desegregate the U.S. armed services; in Woodard's case (and countless others) the idea of the "black body as a site of resistance against racism"[24] is most horrifyingly actualized

See also

- Civil rights movement (1954-1968)

- Civil rights movement (1896–1954)

- Civil rights movement (1865–1896)

- Nadir of American race relations

- Founding Fathers of the United States

- History of civil rights in the United States

- List of civil rights leaders

- Timeline of the civil rights movement

- Black Lives Matter

- Post–civil rights era in African-American history

Notes

- ^ David Hackett Fischer, African Founders: How Enslaved People Expanded American Ideals (Simon and Schuster, 2022).

- ^ Eric Foner, The Second Founding (2019).

- ^ Hannah-Jones, Nikole (2019-08-14). "America Wasn't a Democracy, Until Black Americans Made It One". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2023-02-24.

- ^ Jeffrey K. Tulis and Nicole Mellow, Legacies of losing in American politics (U of Chicago Press, 2018), p. 2. -

- ^ Eric Foner, The Second Founding: How the Civil War and Reconstruction Remade the Constitution (2020) excerpt

- ^ Ilan Wurman, The Second Founding: An Introduction to the Fourteenth Amendment ( 2020) excerpt

- ^ See also Garrett Epps, "Second Founding: The Story of the Fourteenth Amendment." Oregon Law Review 85 (2006) pp: 895-911 online.

- ^ David Hackett Fischer, African Founders: How Enslaved People Expanded American Ideals (Simon and Schuster, 2022) pp 1-3.excerpt

- ^ Paul Rego, Lyman Trumbull and the Second Founding of the United States (University Press of Kansas, 2022) pp. 1–2. excerpt.

- ^ Clay Risen, The Bill of the Century: The Epic Battle for the Civil Rights Act (2014) pp. 2–5.

- ^ Hugh Davis, "We Will Be Satisfied with Nothing Less:" The African American Struggle for Equal Rights in the North during Reconstruction. (Cornell University Press, 2011).

- ^ See Christi M. Smith, "National Equal Rights League (1864-1921)" Black Past (2009) online

- ^ Hugh Davis, "We Will Be Satisfied With Nothing Less": The African American Struggle for Equal Rights in the North During Reconstruction ((Cornell University Press, 2011).

- ^ Hugh Davis, "The Pennsylvania State Equal Rights League and the Northern Black Struggle for Legal Equality, 1864-1877," Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 126#4 (October 2002) pp: 611-634.

- ^ See Paul Finkelman, ed. Encyclopedia of African American History, 1619-1895 (3 vol. 2006) 700 articles by experts.

- ^ See also Eric Foner, Freedom's Lawmakers: A Directory of Black Officeholders during Reconstruction (Oxford University Press, 1993).

- ^ Suzanne Niemeyer, editor, Research Guide to American Historical Biography: vol. IV (1990), pp. 1779–1782.

- ^ David W. Blight, Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom (Simon and Schuster, 2018) p. xv; winner of Pulitzer Prize; excerpt.

- ^ Ray Allen Billington, "James Forten: Forgotten Abolitionist." Negro History Bulletin 13.2 (1949): 31-45. online

- ^ Patricia Ann Schechter, Ida B. Wells-Barnett and American Reform, 1880-1930 (U of North Carolina Press, 2001).

- ^ David L. Lewis, W.E.B. Du bois: A biography (Macmillan, 2009); one-volume abridgement.

- ^ See Thurgood Marshall, "Remarks of Thurgood Marshall" May 6, 1987, online

- ^ Magazine, Smithsonian; Ward, David C. "What Langston Hughes' Powerful Poem "I, Too" Tells Us About America's Past and Present". Smithsonian Magazine.

- ^ , doi:10.1353/mel.0.0061

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)

Further reading

- Carter Jr, William M. "The Second Founding and the First Amendment." Texas Law Review 99 (2020): 1065+. online

- Davis, Hugh. "We Will Be Satisfied with Nothing Less:" The African American Struggle for Equal Rights in the North during Reconstruction. (Cornell University Press, 2011).

- Epps, Garrett. "Second Founding: The Story of the Fourteenth Amendment." Oregon Law Review 85 (2006) pp: 895-911 online.

- Fischer, David Hackett. African Founders: How Enslaved People Expanded American Ideals (Simon and Schuster, 2022) excerpt

- Foner, Eric. The Second Founding: How the Civil War and Reconstruction Remade the Constitution (W.W. Norton, 2020) online; also see online review

- Fox, Jr, James W. "The Constitution of Black Abolitionism: Reframing the Second Founding." University of Pennsylvania Journal of Constitutional Law 23 (2021) pp: 267–350. online; based on documents from the state and national conventions of African Americans, 1831 to 1864.

- Harding, Vincent. There is a river : the Black struggle for freedom in America (1981) online

- Kachun, Mitch. "From Forgotten Founder to Indispensable Icon: Crispus Attacks, Black Citizenship, and Collective Memory, 1770-1865." Journal of the Early Republic 29.2 (2009): 249–286. online

- McPherson, James M. The struggle for equality: Abolitionists and the Negro in the Civil War and Reconstruction (1964) online

- McPherson, James M. The abolitionist legacy from Reconstruction to the NAACP (1995) online

- McPherson, James M. The Negro's Civil War: how American Blacks felt and acted during the war for the Union (1965) online

- Newman, Richard S. and Roy E. Finkenbine, "Black Founders in the New Republic" William and Mary Quarterly (2007) 64#1 pp. 83–94 online

- Newman, Richard S. Freedom’s Prophet: Bishop Richard Allen, the AME Church, and the Black Founding Fathers (2009).

- Quigley, David. Second Founding: New York City, Reconstruction, and the Making of American Democracy (Hill and Wang, 2003)

- Taylor, Brian. Fighting for Citizenship: Black Northerners and the Debate over Military Service in the Civil War (University Of North Carolina Press, 2020). review

- Underwood, James Lowell, et al. eds. At Freedom's Door: African American Founding Fathers and Lawyers in Reconstruction South Carolina (U. of South Carolina Press, 2000.) excerpt; see also online review

- Walton, Hanes, Robert C. Smith, and Sherri L. Wallace. American politics and the African American quest for universal freedom (9th ed. Routledge, 2020) excerpt

- Wurman, Ilan. The Second Founding: An Introduction to the Fourteenth Amendment (Cambridge UP, 2020) excerpt

Primary sources

- Ripley, C. Peter, ed. The Black Abolitionist Papers. Volume III: The United States, 1830-1846 (U North Carolina Press, 1991)

- The Black Abolitionist Papers, Volume IV: The United States, 1847-1858 (1991)

- The Black Abolitionist Papers, Volume V: The United States, 1859-1865 (1992)

![Isaac Woodard served in World War II, had his eyes stolen from him by racist white Americans on the way home, and involuntarily galvanized the federal government to desegregate the U.S. armed services; in Woodard's case (and countless others) the idea of the "black body as a site of resistance against racism"[24] is most horrifyingly actualized](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6c/Isaac-Woodard-1946.jpg/212px-Isaac-Woodard-1946.jpg)