Dalai Lama: Difference between revisions

MacPraughan (talk | contribs) →Unification of Tibet: Addition relevant history w cts. |

MacPraughan (talk | contribs) m →Unification of Tibet: More details and cts on early history with roles of each DL |

||

| Line 78: | Line 78: | ||

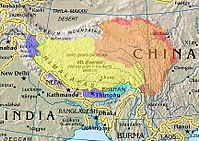

|image3=Tibet-claims.jpg|caption3='Greater Tibet' as claimed by exiled groups |

|image3=Tibet-claims.jpg|caption3='Greater Tibet' as claimed by exiled groups |

||

}} |

}} |

||

The Fourth Dalai Lama, [[Yonten Gyatso]] (1589-1617) was a Mongolian, the great-grandson of [[Altan Khan]] who was a descendant of [[Kublai Khan]] and King of the [[Tümed|Tümed Mongols]] who had already been converted to Buddhism by the Third Dalai Lama, [[Sonam Gyatso]] (1543-1588).<ref name=TN1 >{{cite book|author1=Smith, Warren W. Jr.|title=Tibetan Nation: A History of Tibetan Nationalism and Sino-Tibetan Relations|date=1997|publisher=HarperCollins|location=New Delhi|isbn=0813331552|page=106}}</ref> This strong connection caused the Mongols to zealously support the Gelugpa sect, strengthening the Gelugpa's status and position in Tibet but also arousing intensified opposition from the Gelugpa's Tibetan rivals, the Tsang Karmapa in Shigatse, the Sakya, the Bönpo and their own Mongolian patrons.<ref name=TN1 /> |

|||

The death of [[Yonten Gyatso]] in 1617 led to open conflict breaking out. In 1618, the Tsang Karmapa, who had conspired with the Bönpo chief of Beri in western Kham and whose Mongol patron was [[Choghtu Khong Tayiji]] of the Khalkha, attacked the Gelugpa in Lhasa. This caused the Gelugpa to seek more Mongol patronage and military assistance during the minority of the Fifth Dalai Lama. |

|||

The Gelugpa then found a new patron in [[Güshi Khan]] of the [[Khoshut]], who had recently come from [[Dzungaria]].<ref name=TN /> He defeated and killed Choghtu Khong Tayiji, patron of the Karmapa in 1637 and in Kham in 1640 he attacked the [[Bonpo]] chief of Beri who had conspired with the Tsang Karmapas; he then entered central Tibet and captured [[Shigatse]] which had been a stronghold of the Karmapas.<ref name=TN /> |

|||

By the 1630s Tibet was deeply entangled in power struggles and conflicts, not only between these sects but also between the rising [[Manchu people|Manchu]]s and various rival [[Mongol]] and [[Oirats|Oirat]] factions;<ref name=TN2 >{{cite book|author1=Smith, Warren W. Jr.|title=Tibetan Nation: A History of Tibetan Nationalism and Sino-Tibetan Relations|date=1997|publisher=HarperCollins|location=New Delhi|isbn=0813331552|page=107}}</ref> [[Ligdan Khan]] of the [[Chahars]], a Mongol subgroup, after retreating from the [[Manchu]] armies headed for Kokonor intending destroy the [[Gelug]]. He died on the way to [[Qinghai]] in 1634<ref>Michael Weiers, ''Geschichte der Mongolen'', Stuttgart 2004, p. 182f</ref> but his vassal [[Choghtu Khong Tayiji]], patron of the Tsang Karmapas, continued the fight, even having his own son Arslan killed after Arslan changed sides. |

|||

| ⚫ | Güshi Khan thus |

||

Meanwhile, by the mid-1630s the Fifth Dalai Lama, Lobsang Gyatso (1617-1682) and his Gelugpa sect found a powerful new patron in [[Güshi Khan]] of the [[Khoshut]] Mongols, a subgroup of the [[Dzungars]], who had recently migrated to the Kokonor area from [[Dzungaria]].<ref name=TN2 /> He battled with [[Choghtu Khong Tayiji]] at Kokonor in 1637 and defeated and killed him, eliminating the Karmapas' main Mongol patron completely.<ref name=TN2 /> |

|||

| ⚫ | In this way, Güshi Khan |

||

The Bönpo king of Beri in Kham to the east of Lhasa, [[Donyo Dorje]], was caught conspiring with the ruler of Tsang, [[Karma Tenkyong]], the main patron of the Karmapa in [[Shigatse]] to the west of Lhasa when his letter proposing a joint attack on the Gelugpa in Lhasa from two sides was intercepted and forwarded to Güshi Khan. He used it as a pretext to invade Tibet in 1639 to attack these enemies of the Gelugpa and by 1642 he had eliminated both of them. In 1641 he defeated Donyo Dorje and his allies against the Gelugpa in Kham and then marched on Shigatse where after laying seige to the strongholds he defeated Karma Tenkyong and the power of the Tsang Karmapas in 1642.<ref>Shakabpa, Tsepon W.D. (1967). ''Tibet: A political history.'' New Haven & London: Yale University Press, p. 105-111.</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | Güshi Khan having thus defeated all the Gelugpa's rivals became the overlord of a unified Tibet and acted as a "Protector of the Gelug",<ref>Rene Grousset, ''The Empire of the Steppes'', New Brunswick 1970, p. 522</ref> establishing the [[Khoshut Khanate]], covering almost the entire Tibetan plateau and an area corresponding roughly to 'Greater Tibet' including the whole of Kham and Amdo, as claimed by exiled groups (see maps). At an enthronement ceremony in Shigatse he conferred temporal authority on the Fifth Dalai Lama over a Tibet unified for the first time since the collapse of the Tibetan Empire eight centuries earlier.<ref name=TN2 /> Having resolved all regional and sectarian conflicts Güshi Khan then retired to [[Kokonor]] with his armies leaving the Fifth Dalai Lama to rule Tibet without interference under his patronage and protection.<ref name=TN /> |

||

| ⚫ | The Fifth Dalai Lama's death in 1682 was kept secret for fifteen years by [[Desi Sangye Gyatso]], his regent. This was apparently done so that the [[Potala Palace]] could be finished, and to prevent Tibet's |

||

| ⚫ | In this way, Güshi Khan established the [[Fifth Dalai Lama]] as the highest spiritual and political authority in Tibet. 'The Great Fifth' became the temporal ruler of Tibet in 1642 and from then on the rule of the Dalai Lama lineage over most of Tibet lasted with few breaks for 317 years, until 1959, when the [[14th Dalai Lama]] fled to India.{{harv|Buswell|2014|p=210}} |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | The Fifth Dalai Lama's death in 1682 was kept secret for fifteen years by [[Desi Sangye Gyatso]], his regent. This was apparently done so that construction of the [[Potala Palace]] could be finished, and to prevent Tibet's neighbours taking advantage of an [[interregnum]] in the succession of the Dalai Lamas. {{harv|Laird|2006|181–182}} |

||

The [[6th Dalai Lama]] was not enthroned until 1697. The Sixth enjoyed a lifestyle that included drinking, the company of women, and writing poetry and love songs.<ref>Karenina Kollmar-Paulenz, ''Kleine Geschichte Tibets'', München 2006, pp. 109–122.</ref> In 1705, [[Lha-bzang Khan]] of the Khoshut used the Sixth's escapades as excuse to take control of Tibet. The regent was murdered and the Sixth sent to [[Beijing]]. He died on the way near [[Lake Qinghai]], ostensibly from illness, in 1706. |

The [[6th Dalai Lama]] was not enthroned until 1697. The Sixth enjoyed a lifestyle that included drinking, the company of women, and writing poetry and love songs.<ref>Karenina Kollmar-Paulenz, ''Kleine Geschichte Tibets'', München 2006, pp. 109–122.</ref> In 1705, [[Lha-bzang Khan]] of the Khoshut used the Sixth's escapades as excuse to take control of Tibet. The regent was murdered and the Sixth sent to [[Beijing]]. He died on the way near [[Lake Qinghai]], ostensibly from illness, in 1706. |

||

Revision as of 16:24, 12 June 2015

| Dalai Lama | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reign | 1391–1474 |

| Tibetan | ཏཱ་ལའི་བླ་མ་ |

| Wylie transliteration | tā la'i bla ma |

| Pronunciation | [taːlɛː lama] |

| Conventional Romanisation | Dalai Lama |

| House | Dalai Lama |

Tenzin | |

|---|---|

| |

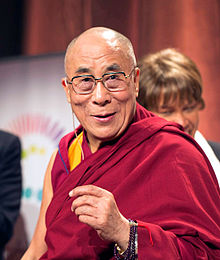

| Title | The 14th Dalai Lama |

| Personal | |

| Born | 6 July 1935 |

| Parents |

|

| Signature |  |

| Senior posting | |

| Predecessor | 13th Dalai Lama |

The Dalai Lama /ˈdɑːlaɪ ˈlɑːmə/[1][2] is a monk of the Gelug or "Yellow Hat" school of Tibetan Buddhism,[3] the newest of the schools of Tibetan Buddhism[4] founded by Je Tsongkhapa. The 14th and current Dalai Lama is Tenzin Gyatso.

The Dalai Lama is considered to be the successor in a line of tulkus who are believed[1] to be incarnations of Avalokiteśvara,[2] the Bodhisattva of Compassion.[5] The name is a combination of the Mongolic word dalai meaning "ocean" and the Tibetan word བླ་མ་ (bla-ma) meaning "guru, teacher, mentor". The Tibetan word "lama" corresponds to the better known Sanskrit word "guru".[6]

From 1642 until the 1950s the Gelug school managed the Tibetan government or Ganden Phodrang which was headed by the Dalai Lama or his regent. Except for minor periods it ruled most or all of Tibet from Lhasa with varying degrees of autonomy, being generally subject to first Mongol (1642-1720) then Manchu (1720-1912) patronage and protection.[7] For example, from 1642 until about 1700 it ruled autonomously over an area corresponding to Greater Tibet, including Kham and Amdo and known to the Dalai Lama's Mongol patrons of the time as the Khoshut Khanate.[8]

History

| Part of a series on |

| Tibetan Buddhism |

|---|

|

In 1252, Qubilai, future Khagan of the Mongols and ruler of Yuan China, granted an audience to Drogön Chögyal Phagpa and Karma Pakshi, 2nd Karmapa Lama (1203-1283). Karma Pakshi, however, sought the patronage of Möngke Khan, the current ruler and Qubilai's political rival, and taught the court the Cakrasaṃvara Tantra. (Buswell 2014:422)

Before his death in 1283, Karma Pakshi wrote a will to protect the established interests of his lineage, the Karma Kagyu, by advising his disciples to locate a boy to inherit the black hat. His instruction was based on the premise that the Dharma is eternal and that the Buddha would send emanations to complete the missions he had initiated. Karma Pakshi's disciples acted in accordance with the will and located the reincarnated boy of their master.[citation needed]

The formalisation of the succession of its incarnate teacher-tulku system by the Karma Kagyu in the early 13th century led to other schools of Tibetan Buddhism adopting the same practice by formalising their own tulku systems.[9]

Emergence of Dalai Lamas

Thus in 1546, some 336 years after the 2nd Karmapa was formally recognised, Sonam Gyatso was similarly recognised by the Gelug as the incarnation of their late teacher Gendun Gyatso, who had been, in turn, informally recognised in 1487 as the incarnation of his predecessor Gendun Drup, who had been the main disciple of Gelugpa founder Je Tsongkhapa.[10] After Sonam Gyatso, each Dalai Lama has been formally recognised and ceremonially enthroned as per the middle columns of the List of Dalai Lamas below. An individual detailed biography of each Dalai Lama is linked to the names given in this list. The Tulku recognition system, once formalised and made into an official institution also involves the legal inheritance by each successor of the predecessor’s monastic home, other former possessions, staff and so forth.[11]

In 1578, after this Sonam Gyatso had been invited to Mongolia and had converted Altan Khan, King of the Tümed Mongols to Buddhism along with his tribe (the first Mongol tribe to be so converted), the King conferred the title ‘Dalai’ on him, ‘Dalai’ being the Mongolian translation of his Tibetan name ‘Gyatso’, which means ‘sea’ or ‘ocean’.[12] Within 50 years nearly all Mongolians had become Buddhist, including tens of thousands of monks, almost all followers of the Gelug school and loyal to the Dalai Lama.[13]

This title was accorded retroactively to Gendun Drup and Gendun Gyatso, as they were considered to be Sonam Gyatso's previous incarnations, so they became known respectively as the First and Second Dalai Lamas, although neither of them had ever been formally recognised or enthroned.[14] Thus, when Sonam Gyatso was named as the Third Dalai Lama in 1578 the Dalai Lama Tulku system became officially established in validation of an already existing but informal mode of succession.[14]

Identification with Avalokiteshvara

The belief in Tibet and other Central Asian Buddhist countries that the bodhisattva of compassion, Avalokiteshvara, has a special relationship with the people of Tibet and intervenes in their fate by incarnating as benevolent rulers and teachers such as the Dalai Lamas had already taken root in Tibet in the 11th and 12th centuries, according to textual evidence such as The Book of Kadam,[15] the main text of the Kadampa sect to which Gendun Drub first belonged. In fact, this text is said to have ‘laid the foundation’ for the Tibetans later identification of the Dalai Lamas as incarnations of Avalokiteshvara;[16] it traces the legend of the bodhisattva’s incarnations as early Tibetan kings and emperors such as Songsten Gampo and later as Dromtönpa (1004-1064).[17] This lineage has been extrapolated by Tibetans up to the Dalai Lamas.[18]

Origins in Myth and Legend

Thus, according to such sources, an informal line of succession of the present Dalai Lamas as incarnations of Avalokiteshvara stretches back much further than Gendun Drub. The Book of Kadam,[19] the compilation of Kadampa teachings largely composed around discussions between the Indian sage Atisa (980-1054) and his Tibetan host Dromtönpa[20][21] and ‘Tales of the Previous Incarnations of Arya Avalokiteshvara’,[22] nominate as many as sixty persons prior to Gendun Drub who are enumerated as earlier incarnations of Avalokiteshvara and predecessors in the same lineage leading up to him. In brief, these include a mythology of thirty six Indian personalities plus ten early Tibetan kings and emperors, all said to be previous incarnations of Dromtönpa, and fourteen further Nepalese and Tibetan yogis and sages in between him and the first Dalai Lama.[23]

Unification of Tibet

The Fourth Dalai Lama, Yonten Gyatso (1589-1617) was a Mongolian, the great-grandson of Altan Khan who was a descendant of Kublai Khan and King of the Tümed Mongols who had already been converted to Buddhism by the Third Dalai Lama, Sonam Gyatso (1543-1588).[24] This strong connection caused the Mongols to zealously support the Gelugpa sect, strengthening the Gelugpa's status and position in Tibet but also arousing intensified opposition from the Gelugpa's Tibetan rivals, the Tsang Karmapa in Shigatse, the Sakya, the Bönpo and their own Mongolian patrons.[24]

The death of Yonten Gyatso in 1617 led to open conflict breaking out. In 1618, the Tsang Karmapa, who had conspired with the Bönpo chief of Beri in western Kham and whose Mongol patron was Choghtu Khong Tayiji of the Khalkha, attacked the Gelugpa in Lhasa. This caused the Gelugpa to seek more Mongol patronage and military assistance during the minority of the Fifth Dalai Lama.

By the 1630s Tibet was deeply entangled in power struggles and conflicts, not only between these sects but also between the rising Manchus and various rival Mongol and Oirat factions;[25] Ligdan Khan of the Chahars, a Mongol subgroup, after retreating from the Manchu armies headed for Kokonor intending destroy the Gelug. He died on the way to Qinghai in 1634[26] but his vassal Choghtu Khong Tayiji, patron of the Tsang Karmapas, continued the fight, even having his own son Arslan killed after Arslan changed sides.

Meanwhile, by the mid-1630s the Fifth Dalai Lama, Lobsang Gyatso (1617-1682) and his Gelugpa sect found a powerful new patron in Güshi Khan of the Khoshut Mongols, a subgroup of the Dzungars, who had recently migrated to the Kokonor area from Dzungaria.[25] He battled with Choghtu Khong Tayiji at Kokonor in 1637 and defeated and killed him, eliminating the Karmapas' main Mongol patron completely.[25]

The Bönpo king of Beri in Kham to the east of Lhasa, Donyo Dorje, was caught conspiring with the ruler of Tsang, Karma Tenkyong, the main patron of the Karmapa in Shigatse to the west of Lhasa when his letter proposing a joint attack on the Gelugpa in Lhasa from two sides was intercepted and forwarded to Güshi Khan. He used it as a pretext to invade Tibet in 1639 to attack these enemies of the Gelugpa and by 1642 he had eliminated both of them. In 1641 he defeated Donyo Dorje and his allies against the Gelugpa in Kham and then marched on Shigatse where after laying seige to the strongholds he defeated Karma Tenkyong and the power of the Tsang Karmapas in 1642.[27]

Güshi Khan having thus defeated all the Gelugpa's rivals became the overlord of a unified Tibet and acted as a "Protector of the Gelug",[28] establishing the Khoshut Khanate, covering almost the entire Tibetan plateau and an area corresponding roughly to 'Greater Tibet' including the whole of Kham and Amdo, as claimed by exiled groups (see maps). At an enthronement ceremony in Shigatse he conferred temporal authority on the Fifth Dalai Lama over a Tibet unified for the first time since the collapse of the Tibetan Empire eight centuries earlier.[25] Having resolved all regional and sectarian conflicts Güshi Khan then retired to Kokonor with his armies leaving the Fifth Dalai Lama to rule Tibet without interference under his patronage and protection.[29]

In this way, Güshi Khan established the Fifth Dalai Lama as the highest spiritual and political authority in Tibet. 'The Great Fifth' became the temporal ruler of Tibet in 1642 and from then on the rule of the Dalai Lama lineage over most of Tibet lasted with few breaks for 317 years, until 1959, when the 14th Dalai Lama fled to India.(Buswell 2014, p. 210)

The time of the Fifth Dalai Lama, who reigned from 1642 to 1682 and founded the government known as the Ganden Phodrang, was a period of rich cultural development.[citation needed]

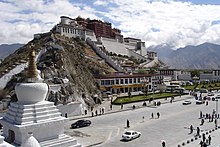

The Fifth Dalai Lama's death in 1682 was kept secret for fifteen years by Desi Sangye Gyatso, his regent. This was apparently done so that construction of the Potala Palace could be finished, and to prevent Tibet's neighbours taking advantage of an interregnum in the succession of the Dalai Lamas. (Laird, 2006 & 181–182)

The 6th Dalai Lama was not enthroned until 1697. The Sixth enjoyed a lifestyle that included drinking, the company of women, and writing poetry and love songs.[30] In 1705, Lha-bzang Khan of the Khoshut used the Sixth's escapades as excuse to take control of Tibet. The regent was murdered and the Sixth sent to Beijing. He died on the way near Lake Qinghai, ostensibly from illness, in 1706.

7th Dalai Lama

Lobzang Khan appointed Yeshe Gyatso as the new Dalai Lama. However, he was not accepted by the Gelug school. Kelzang Gyatso was discovered near Lake Qinghai and became a rival candidate.

The Dzungars invaded Tibet in 1717 and deposed Lha-bzang Khan's candidate. They also began to loot the holy places of Lhasa, which brought a swift response from the Kangxi Emperor in 1718, but his military expedition was annihilated in the Battle of the Salween River not far from Lhasa.[31][32]

A larger expedition sent by the Kangxi Emperor expelled the Dzungars from Tibet in 1720 and the troops were hailed as liberators. They brought Kelzang Gyatso with them from Kumbum to Lhasa and he was installed as the 7th Dalai Lama in 1721.[33]

After him [Jamphel Gyatso the eighth Dalai Lama (1758–1804)], the 9th and 10th Dalai Lamas died before attaining their majority: one of them is credibly stated to have been murdered and strong suspicion attaches to the other. The 11th and 12th were each enthroned but died soon after being invested with power. For 113 years, therefore, supreme authority in Tibet was in the hands of a Lama Regent, except for about two years when a lay noble held office and for short periods of nominal rule by the 11th and 12th Dalai Lamas.

It has sometimes been suggested that this state of affairs was brought about by the Ambans—the Imperial Residents in Tibet—because it would be easier to control the Tibet through a Regent than when a Dalai Lama, with his absolute power, was at the head of the government. That is not true. The regular ebb and flow of events followed its set course. The Imperial Residents in Tibet, after the first flush of zeal in 1750, grew less and less interested and efficient. Tibet was, to them, exile from the urbanity and culture of Peking; and so far from dominating the Regents, the Ambans allowed themselves to be dominated. It was the ambition and greed for power of Tibetans that led to five successive Dalai Lamas being subjected to continuous tutelage. (Richardson 1984, pp. 59–60)

Thubten Jigme Norbu, the elder brother of the 14th Dalai Lama, described these unfortunate events as follows:

It is perhaps more than a coincidence that between the seventh and the thirteenth holders of that office, only one reached his majority. The eighth, Gyampal Gyatso, died when he was in his thirties, Lungtog Gyatso when he was eleven, Tsultrim Gyatso at eighteen, Khadrup Gyatso when he was eighteen also, and Krinla Gyatso at about the same age. The circumstances are such that it is very likely that some, if not all, were poisoned, either by loyal Tibetans for being Chinese-appointed impostors, or by the Chinese for not being properly manageable.(Norbu 1968, p. 311)

13th and 14th Dalai Lamas

The 13th Dalai Lama assumed ruling power from the monasteries, which previously had great influence on the Regent, in 1895. Due to his two periods of exile in 1904–1909 to escape the British invasion of 1904, and from 1910–1912 to escape a Chinese invasion, he became well aware of the complexities of international politics and was the first Dalai Lama to become aware of the importance of foreign relations. After his return from exile in India and Sikkim during January 1913, he assumed control of foreign relations and dealt directly with the Maharaja, with the British Political officer in Sikkim and with the king of Nepal - rather than letting the Kashag or parliament do it. (Sheel 1989, pp. 24, 29)

The Thirteenth issued a Declaration of Independence for his kingdom in Ü-Tsang from China during the summer of 1912 and standardised a Tibetan flag, though no other sovereign state recognized Tibetan independence. (Sheel 1989, p. 20) He expelled the ambans and all Chinese civilians in the country and instituted many measures to modernise Tibet. These included provisions to curb excessive demands on peasants for provisions by the monasteries and tax evasion by the nobles, setting up an independent police force, the abolition of the death penalty, extension of secular education, and the provision of electricity throughout the city of Lhasa in the 1920s. (Norbu and Turnbull 1968, pp. 317–318) He died in 1933.

The 14th Dalai Lama was not formally enthroned until 17 November 1950, during the Battle of Chamdo with the People's Republic of China. In 1951, the Dalai Lama and the Tibetan government were forced to accept the Seventeen Point Agreement for the Peaceful Liberation of Tibet by which it became formally incorporated into the People's Republic of China. Fearing for his life in the wake of a revolt in Tibet in 1959, the 14th Dalai Lama fled to India, from where he led a government in exile.[34][35]

With the aim of launching guerrilla operations against the Chinese, the Central Intelligence Agency funded the Dalai Lama with US$1.7 million a year in the 1960s.[36] In 2001 the 14th Dalai Lama ceded his absolute power over the government to an elected parliament of selected Tibetan exiles. His original goal was full independence for Tibet, but by the late 1980s he was seeking high-level autonomy instead.[37] He continued to seek greater autonomy from China, but Dolma Gyari, deputy speaker of the parliament-in-exile, stated: "If the middle path fails in the short term, we will be forced to opt for complete independence or self-determination as per the UN charter".[38]

Residences

Starting with the 5th Dalai Lama and until the 14th Dalai Lama's flight into exile during 1959, the Dalai Lamas spent winters at the Potala Palace and summers at the Norbulingka palace and park. Both are in Lhasa and approximately 3 km apart.

Following the failed 1959 Tibetan uprising, the 14th Dalai Lama sought refuge in India. The then Indian Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, allowed in the Dalai Lama and the Tibetan government officials. The Dalai Lama has since lived in exile in Dharamshala, in the state of Himachal Pradesh in northern India, where the Central Tibetan Administration is also established. Tibetan refugees have constructed and opened many schools and Buddhist temples in Dharamshala.[39]

Searching for the reincarnation

By the Himalayan tradition, phowa is the discipline that transfers the mindstream to the intended body. Upon the death of the Dalai Lama and consultation with the Nechung Oracle, a search for the Lama's yangsi, or reincarnation, is conducted. Traditionally, it has been the responsibility of the High Lamas of the Gelugpa tradition and the Tibetan government to find his reincarnation. The process can take around two or three years to identify the Dalai Lama, and for the 14th, Tenzin Gyatso, it was four years before he was found. Historically, the search for the Dalai Lama has usually been limited to Tibet, though the third tulku was born in Mongolia. Tenzin Gyatso, however, has stated that he will not be reborn in the People's Republic of China, though he has also suggested he may not be reborn at all, suggesting the function of the Dalai Lama may be outdated.[40] The government of the People's Republic of China has stated its intention to be the ultimate authority on the selection of the next Dalai Lama.[41]

The High Lamas used several ways in which they can increase the chances of finding the reincarnation. High Lamas often visit Lhamo La-tso, a lake in central Tibet, and watch for a sign from the lake itself. This may be either a vision or some indication of the direction in which to search, and this was how Tenzin Gyatso was found. It is said that Palden Lhamo, the female guardian spirit of the sacred lake Lhamo La-tso promised Gendun Drup, the 1st Dalai Lama, in one of his visions "that she would protect the reincarnation lineage of the Dalai Lamas."[citation needed] Ever since the time of Gendun Gyatso, the 2nd Dalai Lama, who formalised the system, the Regents and other monks have gone to the lake to seek guidance on choosing the next reincarnation through visions while meditating there.[42]

The particular form of Palden Lhamo at Lhamo La-tso is Gyelmo Maksorma, "The Victorious One who Turns Back Enemies". The lake is sometimes referred to as "Pelden Lhamo Kalideva", which indicates that Palden Lhamo is an emanation of the goddess Kali, the shakti of the Hindu God Shiva.[43]

Lhamo Latso ... [is] a brilliant azure jewel set in a ring of grey mountains. The elevation and the surrounding peaks combine to give it a highly changeable climate, and the continuous passage of cloud and wind creates a constantly moving pattern on the surface of the waters. On that surface visions appear to those who seek them in the right frame of mind.[44]

It was here that in 1935, the Regent Reting Rinpoche received a clear vision of three Tibetan letters and of a monastery with a jade-green and gold roof, and a house with turquoise roof tiles, which led to the discovery of Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th Dalai Lama.[45][46][47]

High Lamas may also have a vision by a dream or if the Dalai Lama was cremated, they will often monitor the direction of the smoke as an indication of the direction of the rebirth.[40]

Once the High Lamas have found the home and the boy they believe to be the reincarnation, the boy undergoes a battery of tests to affirm the rebirth. They present a number of artifacts, only some of which belonged to the previous Dalai Lama, and if the boy chooses the items which belonged to the previous Dalai Lama, this is seen as a sign, in conjunction with all of the other indications, that the boy is the reincarnation.[48]

If there is only one boy found, the High Lamas will invite Living Buddhas of the three great monasteries, together with secular clergy and monk officials, to confirm their findings and then report to the Central Government through the Minister of Tibet. Later, a group consisting of the three major servants of Dalai Lama, eminent officials,[who?] and troops[which?] will collect the boy and his family and travel to Lhasa, where the boy would be taken, usually to Drepung Monastery, to study the Buddhist sutra in preparation for assuming the role of spiritual leader of Tibet.[40]

If there are several possible reincarnations, however, regents, eminent officials, monks at the Jokhang in Lhasa, and the Minister to Tibet have historically decided on the individual by putting the boys' names inside an urn and drawing one lot in public if it was too difficult to judge the reincarnation initially.[49]

List of Dalai Lamas

Template:ChineseText Template:Contains Indic text There have been 14 recognised incarnations of the Dalai Lama:

| Name | Picture | Lifespan | Recognised | Enthronement | Tibetan/Wylie | Tibetan pinyin/Chinese | Alternative spellings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gendun Drup | File:1stDalaiLama.jpg | 1391–1474 | – | N/A[50] | དགེ་འདུན་འགྲུབ་ dge 'dun 'grub |

Gêdün Chub 根敦朱巴 |

Gedun Drub Gedün Drup |

| 2 | Gendun Gyatso | File:2Dalai.jpg | 1475–1542 | – | N/A[50] | དགེ་འདུན་རྒྱ་མཚོ་ dge 'dun rgya mtsho |

Gêdün Gyaco 根敦嘉措 |

Gedün Gyatso Gendün Gyatso |

| 3 | Sonam Gyatso | File:3rdDalaiLama2.jpg | 1543–1588 | ? | 1578 | བསོད་ནམས་རྒྱ་མཚོ་ bsod nams rgya mtsho |

Soinam Gyaco 索南嘉措 |

Sönam Gyatso |

| 4 | Yonten Gyatso |  |

1589–1617 | 1601 | 1603 | ཡོན་ཏན་རྒྱ་མཚོ་ yon tan rgya mtsho |

Yoindain Gyaco 雲丹嘉措 |

Yontan Gyatso, Yönden Gyatso |

| 5 | Ngawang Lobsang Gyatso |  |

1617–1682 | 1618 | 1622 | བློ་བཟང་རྒྱ་མཚོ་ blo bzang rgya mtsho |

Lobsang Gyaco 羅桑嘉措 |

Lobzang Gyatso Lopsang Gyatso |

| 6 | Tsangyang Gyatso |  |

1683–1706 | 1688 | 1697 | ཚངས་དབྱངས་རྒྱ་མཚོ་ tshang dbyangs rgya mtsho |

Cangyang Gyaco 倉央嘉措 |

Tsañyang Gyatso |

| 7 | Kelzang Gyatso |  |

1707–1757 | 1712 | 1720 | བསྐལ་བཟང་རྒྱ་མཚོ་ bskal bzang rgya mtsho |

Gaisang Gyaco 格桑嘉措 |

Kelsang Gyatso Kalsang Gyatso |

| 8 | Jamphel Gyatso | File:8thDalaiLama.jpg | 1758–1804 | 1760 | 1762 | བྱམས་སྤེལ་རྒྱ་མཚོ་ byams spel rgya mtsho |

Qambê Gyaco 強白嘉措 |

Jampel Gyatso Jampal Gyatso |

| 9 | Lungtok Gyatso | File:9thDalaiLama.jpg | 1805–1815 | 1807 | 1808 | ལུང་རྟོགས་རྒྱ་མཚོ་ lung rtogs rgya mtsho |

Lungdog Gyaco 隆朵嘉措 |

Lungtog Gyatso |

| 10 | Tsultrim Gyatso | File:10thDalaiLama.jpg | 1816–1837 | 1822 | 1822 | ཚུལ་ཁྲིམས་རྒྱ་མཚོ་ tshul khrim rgya mtsho |

Cüchim Gyaco 楚臣嘉措 |

Tshültrim Gyatso |

| 11 | Khendrup Gyatso | File:11thDalaiLama1.jpg | 1838–1856 | 1841 | 1842 | མཁས་གྲུབ་རྒྱ་མཚོ་ mkhas grub rgya mtsho |

Kaichub Gyaco 凱珠嘉措 |

Kedrub Gyatso |

| 12 | Trinley Gyatso | File:12thDalai Lama.jpg | 1857–1875 | 1858 | 1860 | འཕྲིན་ལས་རྒྱ་མཚོ་ 'phrin las rgya mtsho |

Chinlai Gyaco 成烈嘉措 |

Trinle Gyatso |

| 13 | Thubten Gyatso |  |

1876–1933 | 1878 | 1879 | ཐུབ་བསྟན་རྒྱ་མཚོ་ thub bstan rgya mtsho |

Tubdain Gyaco 土登嘉措 |

Thubtan Gyatso Thupten Gyatso |

| 14 | Tenzin Gyatso |  |

born 1935 | 1939[51] | 1940[51] (currently in exile) |

བསྟན་འཛིན་རྒྱ་མཚོ་ bstan 'dzin rgya mtsho |

Dainzin Gyaco 丹增嘉措 |

Tenzin Gyatso |

There has also been one non-recognised Dalai Lama, Ngawang Yeshe Gyatso, declared 28 June 1707, when he was 25 years old, by Lha-bzang Khan as the "true" 6th Dalai Lama – however, he was never accepted as such by the majority of the population.[32][52][53]

Future of the position

In the mid-1970s, Tenzin Gyatso, the Fourteenth Dalai Lama, told a Polish newspaper that he thought he would be the last Dalai Lama. In a later interview published in the English language press he stated, "The Dalai Lama office was an institution created to benefit others. It is possible that it will soon have outlived its usefulness."[54] These statements caused a furor amongst Tibetans in India. Many could not believe that such an option could even be considered. It was further felt that it was not the Dalai Lama's decision to reincarnate. Rather, they felt that since the Dalai Lama is a national institution it was up to the people of Tibet to decide whether the Dalai Lama should reincarnate.[55]

The government of the People's Republic of China (PRC) has claimed the power to approve the naming of "high" reincarnations in Tibet, based on a precedent set by the Qianlong Emperor of the Qing Dynasty.[citation needed] The Qianlong Emperor instituted a system of selecting the Dalai Lama and the Panchen Lama by a lottery that used a golden urn with names wrapped in clumps of barley. This method was used a few times for both positions during the 19th century, but eventually fell into disuse.[citation needed] In 1995, the Dalai Lama chose to proceed with the selection of the 11th reincarnation of the Panchen Lama without the use of the Golden Urn, while the Chinese government insisted that it must be used.[citation needed] This has led to two rival Panchen Lamas: Gyaincain Norbu as chosen by the Chinese government's process, and Gedhun Choekyi Nyima as chosen by the Dalai Lama.

During September 2007 the Chinese government said all high monks must be approved by the government, which would include the selection of the 15th Dalai Lama after the death of Tenzin Gyatso.[citation needed] Since by tradition, the Panchen Lama must approve the reincarnation of the Dalai Lama, that is another possible method of control.[citation needed]

In response to this scenario, Tashi Wangdi, the representative of the 14th Dalai Lama, replied that the Chinese government's selection would be meaningless. "You can't impose an Imam, an Archbishop, saints, any religion...you can't politically impose these things on people," said Wangdi. "It has to be a decision of the followers of that tradition. The Chinese can use their political power: force. Again, it's meaningless. Like their Panchen Lama. And they can't keep their Panchen Lama in Tibet. They tried to bring him to his monastery many times but people would not see him. How can you have a religious leader like that?"[56]

The 14th Dalai Lama said as early as 1969 that it was for the Tibetans to decide whether the institution of the Dalai Lama "should continue or not".[57] He has given reference to a possible vote occurring in the future for all Tibetan Buddhists to decide whether they wish to recognize his rebirth.[58] In response to the possibility that the PRC might attempt to choose his successor, the Dalai Lama said he would not be reborn in a country controlled by the People's Republic of China or any other country which is not free.[40][59] According to Robert D. Kaplan, this could mean that "the next Dalai Lama might come from the Tibetan cultural belt that stretches across northern India, Nepal, and Bhutan, presumably making him even more pro-Indian and anti-Chinese".[60]

The 14th Dalai Lama supported the possibility that his next incarnation could be a woman.[61] As an "engaged Buddhist" the Dalai Lama has an appeal straddling cultures and political systems making him one of the most recognized and respected moral voices today.[62] "Despite the complex historical, religious and political factors surrounding the selection of incarnate masters in the exiled Tibetan tradition, the Dalai Lama is open to change," author Michaela Haas writes.[63] "Why not? What's the big deal?"[64]

See also

- Engaged Spirituality

- Patron and priest relationship

- List of rulers of Tibet

- Tibet Autonomous Region

- Tibet Religious Foundation of His Holiness the Dalai Lama

Notes and references

- ^ a b "Define Dalai lama". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 2014-03-12.

(formerly) the ruler and chief monk of Tibet, believed to be a reincarnation of Avalokitesvara and sought for among newborn children after the death of the preceding Dalai Lama

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Definition of Dalai Lama in English". Oxford Dictionaries. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

The spiritual head of Tibetan Buddhism and, until the establishment of Chinese communist rule, the spiritual and temporal ruler of Tibet. Each Dalai Lama is believed to be the reincarnation of the bodhisattva Avalokitesvara, reappearing in a child when the incumbent Dalai Lama dies

- ^ Dr Alexander Berzin (November 2014). "Special Features of the Gelug Tradition - para. on Administration". The Buddhist Archives of Dr Alexander Berzin. Berzin Archives. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

The Dalai Lamas are not the heads of the Gelug tradition

- ^ Schaik, Sam van. Tibet: A History. Yale University Press 2011, page 129, "Gelug: the newest of the schools of Tibetan Buddhism".

- ^ Peter Popham (January 29, 2015). "Relentless: The Dalai Lama's Heart of Steel". Newsweek magazine.

His mystical legitimacy – of huge importance to the faithful – stems from the belief that the Dalai Lamas are manifestations of Avalokiteshvara, the Bodhisattva of Compassion

- ^ "lama" from Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Smith, Warren W. Jr. (1997). Tibetan Nation: A History of Tibetan Nationalism and Sino-Tibetan Relations. New Delhi: HarperCollins. pp. 107–149. ISBN 0813331552.

- ^ Smith, Warren W. Jr. (1997). Tibetan Nation: A History of Tibetan Nationalism and Sino-Tibetan Relations. New Delhi: HarperCollins. pp. 107–121. ISBN 0813331552.

- ^ Buswell, Robert E.; Lopez, Donald S. Jr. Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism (2014 ed.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 421. ISBN 9780691157863. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

In the history of Tibetan Buddhism, the lineage of the Karmapas is considered to be the first to institutionalize its succession of incarnate lamas, a practice later adopted by the other sects

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Laird, Thomas (2006). The Story of Tibet: Conversations with the Dalai Lama, p. 239. Grove Press, N.Y. ISBN 978-0-8021-1827-1

- ^ Alexander Berzin (2000). Wise Teacher, Wise Student. Ithaca, NY: Snow Lion Publications. p. 20. ISBN 9781559393478.

- ^ McKay 2003, p. 18

- ^ Laird, Thomas (2006). The Story of Tibet: Conversations with the Dalai Lama, p. 144. Grove Press, N.Y. ISBN 978-0-8021-1827-1

- ^ a b McKay 2003, p. 19

- ^ Thubten Jinpa. "Introduction". The Book of Kadam. Wisdom Publications. ISBN 9780861714414.

Available textual evidence points strongly toward the eleventh and twelfth centuries as the period during which the full myth of Avalokiteśvara special destiny with Tibet was established. During this era, the belief that this compassionate spirit intervenes in the fate of the Tibetan people by manifesting as benevolent rulers and teachers took firm root

- ^ Thubten Jinpa. "Introduction". The Book of Kadam. Wisdom Publications. ISBN 9780861714414.

Perhaps the most important legacy of the book, at least for the Tibetan people as a whole, is that it laid the foundation for the later identification of Avalokiteśvara with the lineage of the Dalai Lama

- ^ Thubten Jinpa. "Introduction". The Book of Kadam. Wisdom Publications. ISBN 9780861714414.

For the Tibetans, the mythic narrative that began with Avalokiteśvara's embodiment in the form of Songtsen Gampo in the seventh century—or even earlier with the mythohistorical figures of the first king of Tibet, Nyatri Tsenpo (traditionally calculated to have lived around the fifth century B.C.E.), and Lha Thothori Nyentsen (ca. third century c.e.), during whose reign some sacred Buddhist scriptures are believed to have arrived in Tibet... continued with Dromtönpa in the eleventh century

- ^ Thubten Jinpa. "Introduction". The Book of Kadam. Wisdom Publications. ISBN 9780861714414.

For the Tibetans, the mythic narrative... continues today in the person of His Holiness Tenzin Gyatso, the Fourteenth Dalai Lama

- ^ Thubten Jinpa. The Book of Kadam. Wisdom Publications. ISBN 9780861714414.

- ^ Thubten Jinpa. "Introduction". The Book of Kadam. Wisdom Publications. ISBN 9780861714414.

'The Book' gives ample evidence of the existence of an ancient, mythological Tibetan narrative placing the Dalai Lamas as incarnations of Dromtönpa, of his predecessors and of Avalokiteshvara

- ^ Tuttle, Gray; Schaeffer, Curtis R. (2013). The Tibetan History Reader. Columbia University Press. p. 335. ISBN 9780231513548.

In Atiśa's telling, Dromtön was not only Avalokiteśvara but also a reincarnation of former Buddhist monks, laypeople, commoners, and kings. Furthermore, these reincarnations were all incarnations of that very same being, Avalokiteśvara. Van der Kuijp takes us on a tour of literary history, showing that the narrative attributed to Atiśa became a major source for both incarnation and reincarnation ideology for centuries to come." From: "The Dalai Lamas and the Origins of Reincarnate Lamas. Leonard W. J. van der Kuijp"

- ^ Mullin 2001, p.39

- ^ Stein (1972), p. 138-139|quote=the Dalai Lama is ... a link in the chain that starts in history and leads back through legend to a deity in mythical times. The First Dalai Lama, Gedün-trup (1391-1474), was already the 51st incarnation; the teacher Dromtön, Atiśa's disciple (eleventh century), the 45th; whilst with the 26th, one Gesar king of India, and the 27th, a hare, we are in pure legend

- ^ a b Smith, Warren W. Jr. (1997). Tibetan Nation: A History of Tibetan Nationalism and Sino-Tibetan Relations. New Delhi: HarperCollins. p. 106. ISBN 0813331552.

- ^ a b c d Smith, Warren W. Jr. (1997). Tibetan Nation: A History of Tibetan Nationalism and Sino-Tibetan Relations. New Delhi: HarperCollins. p. 107. ISBN 0813331552.

- ^ Michael Weiers, Geschichte der Mongolen, Stuttgart 2004, p. 182f

- ^ Shakabpa, Tsepon W.D. (1967). Tibet: A political history. New Haven & London: Yale University Press, p. 105-111.

- ^ Rene Grousset, The Empire of the Steppes, New Brunswick 1970, p. 522

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

TNwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Karenina Kollmar-Paulenz, Kleine Geschichte Tibets, München 2006, pp. 109–122.

- ^ Richardson (1984), pp. 48–9.

- ^ a b Stein (1972), p. 85.

- ^ Schirokauer, 242

- ^ Tibet in Exile, CTA Official website, retrieved 2010-12-15.

- ^ Dalai Lama Intends To Retire As Head of Tibetan State In Exile by Mihai-Silviu Chirila (2010-11-23), Metrolic, retrieved 2010-12-15.

- ^ "Dalai Lama Group Says It Got Money From C.I.A." The New York Times. 1998-10-02.

- ^ Burke, Denis (2008-11-27). "Tibetans stick to the 'middle way'". Asia Times. Retrieved 2010-08-07.

- ^

Saxena, Shobhan (2009-10-31). "The burden of being Dalai Lama". The Times of India. Retrieved 2010-08-06.

If the middle path fails in the short term, we will be forced to opt for complete independence or self-determination as per the UN charter

[dead link] - ^ "Dispatches from the Tibetan Front: Dharamshala, India," Litia Perta, The Brooklyn Rail, April 4, 2008

- ^ a b c d "The Dalai Lama". BBC. 2006-09-21. Retrieved 2008-05-17.

- ^ http://www.nytimes.com/2015/03/12/world/asia/chinas-tensions-with-dalai-lama-spill-into-the-afterlife.html?hp&action=click&pgtype=Homepage&module=second-column-region®ion=top-news&WT.nav=top-news

- ^ Laird (2006), pp. 139, 264–265.

- ^ Dowman (1988), p. 260.

- ^ Hilton, Isabel. (1999). The Search for the Panchen Lama. Viking Books. Reprint: Penguin Books. (2000), pp. 39–40. ISBN 0-14-024670-3.

- ^ Laird (2006), p. 139.

- ^ Norbu and Turnbull (1968), pp. 228–230. Reprint: p. 311.

- ^ Hilton, Isabel. (1999). The Search for the Panchen Lama. Viking Books. Reprint: Penguin Books. (2000), p. 42. ISBN 0-14-024670-3.

- ^ "The Dalai Lama's Succession Rethink". Time World. 2007-11-21. Retrieved 2013-04-06.

- ^ "Dalai Lama's confirmation of reincarnation". Tibet Travel info. Retrieved 2008-05-17.

- ^ a b The title "Dalai Lama" was conferred posthumously to the 1st and 2nd Dalai Lamas.

- ^ a b "Chronology of Events". His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama of Tibet. Office of His Holiness the Dalai Lama. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

- ^ Chapman, F. Spencer. (1940). Lhasa: The Holy City, p. 127. Readers Union Ltd. London.

- ^ Mullin 2001, p. 276

- ^ Glenn H. Mullin, "Faces of the Dalai Lama: Reflections on the Man and the Tradition," Quest, vol. 6, no. 3, Autumn 1993, p. 80.

- ^ Verhaegen (2002), p. 5.

- ^ Interview with Tashi Wangdi, David Shankbone, Wikinews, November 14, 2007.

- ^ "Dalai's reincarnation will not be found under Chinese control". Government of Tibet in Exile.[dead link]

- ^ Dalai Lama may forgo death before reincarnation, Jeremy Page, The Australian, November 29, 2007.

- ^ "Dalai's reincarnation will not be found under Chinese control". Government of Tibet in Exile ex Indian Express July 6, 1999.[dead link]

- ^ Kaplan Robert, Foreign Affairs, "The Geography of Chinese Power"

- ^ Haas, Michaela (2013-04-15). "A Female Dalai Lama? Why It Matters". The Huffington Post.

- ^ Puri, Bharati (2006) "Engaged Buddhism - The Dalai Lama's Worldview" New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2006

- ^ Haas, Michaela (2013). "Dakini Power: Twelve Extraordinary Women Shaping the Transmission of Tibetan Buddhism in the West." Shambhala Publications. ISBN 1559394072

- ^ Bindley, Katherine (2013-04-24). "Dalai Lama Says He Would Support A Woman Successor". The Huffington Post.

Bibliography

- Buswell, Robert E.; Lopez, Donald S. Jr., eds. (2014). Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691157863.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dowman, Keith (1988). The power-places of Central Tibet : the pilgrim's guide. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. ISBN 0-7102-1370-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Laird, Thomas (2006). The story of Tibet : conversations with the Dalai Lama (1st ed. ed.). New York: Grove Press. ISBN 978-0-8021-1827-1.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Richardson, Hugh E. (1984). Tibet and its history (2nd ed., rev. and updated. ed.). Boston: Shambhala. ISBN 978-0877733768.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - McKay, A. (2003). History of Tibet. RoutledgeCurzon. ISBN 978-0-7007-1508-4.

- Silver, Murray (2005). When Elvis Meets the Dalai Lama (1st ed. ed.). Savannah, GA: Bonaventture. ISBN 978-0972422444.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Norbu, Thubten Jigme; Turnbull, Colin M. (1968). Tibet. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-671-20559-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Schulemann, Günther (1958). Die Geschichte der Dalai Lamas. Leipzig: Veb Otto Harrassowitz. ISBN 978-3530500011.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sheel, R N Rahul (1989). "The Institution of the Dalai Lama". The Tibet Journal. 15 (3).

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Smith, Warren W. (1997). Tibetan Nation; A History of Tibetan Nationalism and Sino-Tibetan Relations. New Delhi: HarperCollins. ISBN 0813331552.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Stein, R. A. (1972). Tibetan civilization ([English ed.]. ed.). Stanford, Calif.: Stanford Univ. Press. ISBN 0-8047-0901-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Diki Tsering (2001). Dalai Lama, my son : a mother's story. London: Virgin. ISBN 0-7535-0571-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Veraegen, Ardy (2002). The Dalai Lamas : the Institution and its history. New Delhi: D.K. Printworld. ISBN 978-8124602027.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ya, Hanzhang (1991). The biographies of the Dalai Lamas (1st ed. ed.). Beijing: Foreign Language Press. ISBN 978-7119012674.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

- Dalai Lama. (1991) Freedom in Exile: The Autobiography of the Dalai Lama. San Francisco, CA.

- Goodman, Michael H. (1986). The Last Dalai Lama. Shambhala Publications. Boston, MA.

- Mullin, Glenn H. (2001). The Fourteen Dalai Lamas: A Sacred Legacy of Reincarnation. Clear Light Publishers. Santa Fe, NM. ISBN 1-57416-092-3.

- Harrer, Heinrich (1951) Seven Years in Tibet: My Life Before, During and After

External links

- Official website

- Nonviolence Freedom Collection interview

- Dalai Lama at Curlie