Genetically modified food controversies: Difference between revisions

Sportmedman (talk | contribs) →Scientific publishing: What Biofortified plans to do is speculation and not notable. |

GreenC bot (talk | contribs) Move 1 url. Wayback Medic 2.5 per WP:URLREQ#cbsnews.com/numeric |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|none}} |

|||

{{for|related content|Genetic engineering|Genetically modified organism|Genetically modified food|Genetically modified crops|Regulation of the release of genetically modified organisms}} |

|||

{{pp|small=yes}} |

|||

{{Use American English|date=January 2019}} |

|||

{{Use mdy dates|date=January 2019}} |

|||

{{Genetic engineering sidebar}} |

|||

'''Genetically modified food controversies''' are disputes over the use of foods and other goods derived from [[genetically modified crops]] instead of [[Plant breeding#Classical plant breeding|conventional crops]], and other uses of [[genetic engineering]] in food production. The disputes involve [[consumers]], [[farmers]], [[biotechnology|biotechnology companies]], governmental regulators, non-governmental organizations, and scientists. The key areas of controversy related to [[genetically modified food]] (GM food or GMO food) are whether such food should be labeled, the role of government regulators, the objectivity of scientific research and publication, the effect of genetically modified crops on health and the environment, the effect on [[pesticide resistance]], the impact of such crops for farmers, and the role of the crops in feeding the world population. In addition, products derived from GMO organisms play a role in the production of [[ethanol]] fuels and pharmaceuticals.<!--referring to GMO corn to create ethanol fuels and GMO bacteria to produce medication. Will insert refs asap.--> |

|||

Specific concerns include mixing of genetically modified and non-genetically modified products in the food supply,{{R|CIEH}} effects of GMOs on the environment,{{R|CAPE|VDC}} the rigor of the regulatory process,{{R|IDEA|AMA_2012}} and consolidation of control of the food supply in companies that make and sell GMOs.{{R|CAPE}} [[Advocacy groups]] such as the [[Center for Food Safety]], [[Organic Consumers Association]], [[Union of Concerned Scientists]], and [[Greenpeace]] say risks have not been adequately identified and managed, and they have questioned the objectivity of regulatory authorities. |

|||

The '''genetically modified foods controversy''' is a dispute over the use of foods and other goods derived from [[genetically modified crops]] instead of [[Plant breeding#Classical plant breeding|conventional crops]], and other uses of [[genetic engineering]] in food production. The dispute involves consumers, biotechnology companies, governmental regulators, non-governmental organizations, and scientists. The key areas of controversy related to [[genetically modified food|GMO food]] are whether such food should be labeled, the role of government regulators, the objectivity of scientific research and publication, the effect of genetically modified crops on health and the environment, the effect on pesticide resistance, the impact of such crops for farmers, and the role of the crops in feeding the world population. |

|||

The safety assessment of genetically engineered food products by regulatory bodies starts with an evaluation of whether or not the food is ''[[substantial equivalence|substantially equivalent]]'' to non-genetically engineered counterparts that are already deemed fit for human consumption.{{R|ToxSoc2003|whybiotech.com}}{{R|UC-ANR8180|Kuiper_2002}} No reports of ill effects have been documented in the human population from genetically modified food.{{R|AMA|NRC_2004|Key_2008}} |

|||

While there is concern among the public that eating genetically modified food may be harmful, there is broad [[scientific consensus]] that food on the market derived from these crops poses no greater risk to human health than conventional food.<ref name="AAAS">American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), Board of Directors (2012). [http://www.aaas.org/news/releases/2012/1025gm_statement.shtml Legally Mandating GM Food Labels Could Mislead and Falsely Alarm Consumers]</ref><ref name="decade_of_EU-funded_GMO_research"/><ref name="Ronald">{{cite journal | author = Ronald, Pamela | title = Plant Genetics, Sustainable Agriculture and Global Food Security | journal = Genetics | volume = 188 | issue = 1 | pages = 11–20 | year = 2011 | url=http://www.genetics.org/content/188/1/11.long | doi = 10.1534/genetics.111.128553 | pmid = 21546547 | pmc = 3120150}}</ref> The safety assessment of genetically engineered food products by regulatory bodies starts with an evaluation of whether or not the food is ''[[substantial equivalence|substantially equivalent]]'' to non-genetically engineered counterparts that are already deemed fit for human consumption. No reports of ill effects have been documented in the human population from genetically modified food.<ref name="AMA">American Medical Association (2012). [http://www.ama-assn.org/resources/doc/csaph/a12-csaph2-bioengineeredfoods.pdf Report 2 of the Council on Science and Public Health: Labeling of Bioengineered Foods] "Bioengineered foods have been consumed for close to 20 years, and during that time, no overt consequences on human health have been reported and/or substantiated in the peer-reviewed literature." (first page)</ref><ref name=NRC2004>United States [[Institute of Medicine]] and [[United States National Research Council|National Research Council]] (2004). Safety of Genetically Engineered Foods: Approaches to Assessing Unintended Health Effects. National Academies Press. [http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=10977#toc Free full-text]. National Academies Press. pp R9-10: "In contrast to adverse health effects that have been associated with some traditional food production methods, similar serious health effects have not been identified as a result of genetic engineering techniques used in food production. This may be because developers of bioengineered organisms perform extensive compositional analyses to determine that each phenotype is desirable and to ensure that unintended changes have not occurred in key components of food."</ref><ref name="Key">{{cite journal | author = Key S, Ma JK, Drake PM | title = Genetically modified plants and human health | journal = J R Soc Med | volume = 101 | issue = 6 | pages = 290–8 |date=June 2008 | pmid = 18515776 | pmc = 2408621 | doi = 10.1258/jrsm.2008.070372 | quote = +pp 292-293. "Foods derived from GM crops have been consumed by hundreds of millions of people across the world for more than 15 years, with no reported ill effects (or legal cases related to human health), despite many of the consumers coming from that most litigious of countries, the USA." }}</ref> Although labeling of [[genetically modified organism]] (GMO) products in the marketplace is required in many countries, it is not required in the United States or Canada and no distinction between marketed GMO and non-GMO foods is recognized by the U.S. [[Food and Drug Administration]]. |

|||

<!-- The following language and sources, per [[WP:GMORfC]], must not be altered without achieving consensus-->There is a [[scientific consensus]]<ref name="Nicolia2013"/><ref name="FAO"/><ref name="Ronald2011"/><ref name="Also"/> that currently available food derived from GM crops poses no greater risk to human health than conventional food,<ref name="AAAS2012"/><ref name="ECom2010"/><ref name="AMA2001"/><ref name="LoC2015"/><ref name="NAS2016"/> but that each GM food needs to be tested on a case-by-case basis before introduction.<ref name="WHOFAQ"/><ref name="Haslberger2003"/><ref name="BMA2004"/> Nonetheless, members of the public are much less likely than scientists to perceive GM foods as safe.<ref name="PEW2015"/>{{R|Marris2001}}<ref name="PABE"/><ref name="Scott2016"/> The legal and regulatory status of GM foods varies by country, with some nations banning or restricting them and others permitting them with widely differing degrees of regulation.<ref name="loc.gov"/><ref name="Bashshur"/><ref name="Sifferlin"/><ref name="Council on Foreign Relations"/><!--End of restricted section --> |

|||

Opponents of genetically modified food, such as the advocacy groups [[Organic Consumers Association]], the [[Union of Concerned Scientists]], and [[Greenpeace]], say risks have not been adequately identified and managed, and they have questioned the objectivity of regulatory authorities. Some groups say there are unanswered questions regarding the potential long-term impact on human health from food derived from GMOs, and propose mandatory labeling<ref name=BMA>[[British Medical Association]] Board of Science and Education (2004). [http://www.argenbio.org/adc/uploads/pdf/bma.pdf Genetically modified food and health: A second interim statement.] March.</ref><ref name=PHAA>Public Health Association of Australia (2007) [http://www.phaa.net.au/documents/policy/GMFood.pdf GENETICALLY MODIFIED FOODS] PHAA AGM 2007</ref> or a moratorium on such products.<ref name=CAPE> [[Canadian Association of Physicians for the Environment]] (2013) [http://cape.ca/capes-position-statement-on-gmos/ Statement on Genetically Modified Organisms in the Environment and the Marketplace.] October, 2013</ref><ref name=IDEA> Irish Doctors' Environmental Association [http://ideaireland.org/library/idea-position-on-genetically-modified-foods/ IDEA Position on Genetically Modified Foods.] Retrieved 3/25/14 </ref><ref name=VDC> PR Newswire [http://www.prnewswire.co.uk/news-releases/genetically-modified-maize-doctors-chamber-warns-of-unpredictable-results-to-humans-231410601.html Genetically Modified Maize: Doctors' Chamber Warns of "Unpredictable Results" to Humans.] November 11, 2013</ref> Concerns include contamination of the non-genetically modified food supply,<ref name=CIEH> [[Chartered Institute of Environmental Health]] (2006) [http://www.cieh.org/uploadedFiles/Core/Policy/CIEH_consultation_responses/Response_GM_final.pdf Proposals for managing the coexistence of GM, conventional and organic crops Response to the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs consultation paper.] October 2006 </ref> effects of GMOs on the environment and nature,<ref name=CAPE/><ref name=VDC/> the rigor of the regulatory process,<ref name=IDEA/><ref>[[American Medical Association]] (2012). [http://www.ama-assn.org/resources/doc/csaph/a12-csaph2-bioengineeredfoods.pdf Report 2 of the Council on Science and Public Health: Labeling of Bioengineered Foods.] "To better detect potential harms of bioengineered foods, the Council believes that pre-market safety assessment should shift from a voluntary notification process to a mandatory requirement." page 7</ref> and consolidation of control of the food supply in companies that make and sell GMOs.<ref name=CAPE/> |

|||

{{toclimit|3}} |

|||

==Public perception== |

==Public perception== |

||

Consumer concerns about food quality first became prominent long before the advent of GM foods in the 1990s. [[Upton Sinclair]]'s novel ''[[The Jungle]]'' led to the 1906 [[Pure Food and Drug Act]], the first major US legislation on the subject.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/fdas-evolving-regulatory-powers/part-i-1906-food-and-drugs-act-and-its-enforcement |title=The 1906 Food and Drugs Act and Its Enforcement |last=Swann |first=John P | name-list-style = vanc |series=FDA History – Part I |publisher=U.S. Food and Drug Administration|access-date = 10 April 2013}}</ref> This began an enduring concern over the purity and later "naturalness" of food that evolved from a single focus on sanitation to include others on added ingredients such as [[preservatives]], [[Flavoring|flavors]] and [[sweeteners]], residues such as pesticides, the rise of [[organic food]] as a category and, finally, concerns over GM food. Some consumers, including many in the US, came to see GM food as "unnatural", with various negative associations and fears (a reverse [[halo effect]]).<ref>{{cite magazine |first=Maria |last=Konnikova | name-list-style = vanc |magazine=[[The New Yorker]] |date=August 8, 2013 |url=https://www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/elements/2013/08/the-psychology-of-distrusting-gmos.html |title=The Psychology of Distrusting G.M.O.s}}</ref> |

|||

Specific perceptions include a view of genetic engineering as meddling with naturally evolved biological processes, and one that science has limitations on its comprehension of potential negative ramifications.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/23/well/eat/are-gmo-foods-safe.html|title=Are G.M.O. Foods Safe?|last=Brody|first=Jane E.|date=2018-04-23|work=The New York Times|access-date=2019-01-07|language=en-US|issn=0362-4331}}</ref> An opposing perception is that genetic engineering is itself an evolution of traditional [[selective breeding]], and that the weight of current evidence suggests current GM foods are identical to conventional foods in nutritional value and effects on health.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/18/business/genetically-engineered-crops-are-safe-analysis-finds.html|title=Genetically Engineered Crops Are Safe, Analysis Finds|last=Pollack|first=Andrew|date=2016-05-17|work=The New York Times|access-date=2019-01-07|language=en-US|issn=0362-4331}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/11/01/genetically-engineered-food-health_n_2041372.html |title=Can Genetically Engineered Foods Harm You? |work=[[Huffington Post]] |date=1 November 2012 | access-date=7 September 2013 |last=Borel |first=Brooke | name-list-style = vanc}}</ref> |

|||

There is widespread popular perception that eating genetically modified food is harmful, and based primarily on that concern, but also on wider concerns about the environment, anti-GMO activists have lobbied for restrictions on growing modified crops and on selling such food, and for labels on genetically modified food that is sold.<ref name=NatureEd>Editorial. Editors of Nature. [http://www.nature.com/news/fields-of-gold-1.12897 Nature 497, 5–6 (02 May 2013) doi:10.1038/497005b Fields of gold]</ref><ref name=NYTimesQuest>Amy Harmon for ''The New York Times,'' Jan 4, 2014. [http://www.nytimes.com/2014/01/05/us/on-hawaii-a-lonely-quest-for-facts-about-gmos.html?_r=0 A Lonely Quest for Facts on Genetically Modified Crops]</ref><ref name=GristBegin>Nathanael Johnson for Grist. Jul 8, 2013 [http://grist.org/food/the-genetically-modified-food-debate-where-do-we-begin/ The genetically modified food debate: Where do we begin?]</ref> Particular concerns are claims that genetically modified food causes cancer and allergies.<ref name=NYTimesQuest/> Leaders in driving public perception of the harms of such food in the media include [[Jeffrey M. Smith]], [[Dr. Oz]], [[Oprah]], and [[Bill Maher]];<ref name=NYTimesQuest/><ref>Keith Kloor for Discover Magazine. October 19, 2012 [http://blogs.discovermagazine.com/collideascape/2012/10/19/liberals-turn-a-blind-eye-to-crazy-talk-on-gmos/#.Uueb32Qo5GG Liberals Turn a Blind Eye to Crazy Talk on GMOs]</ref> organizations include [[Organic Consumers Association]],<ref>Mike Hughlett Star Tribune (Minneapolis) for the Witchita Eagle. Nov. 5, 2013 [http://www.kansas.com/2013/11/05/3092814/firebrand-activist-leads-organic.html Firebrand activist leads organic consumers association]</ref> [[Greenpeace]] (especially with regard to [[Golden rice]])<ref>Alberts B et al. September 20, 2013 http://www.sciencemag.org/content/341/6152/1320.full [Editorial: Standing Up for GMOs] Science 341(6152):1320</ref> and [[Union of Concerned Scientists]].<ref name=GristBegin/> |

|||

Surveys indicate widespread concern among consumers that eating genetically modified food is harmful,<ref name=NatureEd>{{cite journal |author=((Editors of Nature)) |journal=Nature |volume=497 |issue=5–6 |pages=5–6 |date=2 May 2013 |doi=10.1038/497005b |pmid=23646363 |title=Editorial: Fields of gold|doi-access=free }}</ref><ref name=NYTimesQuest>{{cite web |first=Amy |last=Harmon | name-list-style = vanc |work=The New York Times |date=4 January 2014 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2014/01/05/us/on-hawaii-a-lonely-quest-for-facts-about-gmos.html?_r=0 |title=A Lonely Quest for Facts on Genetically Modified Crops}}</ref><ref name=GristBegin>{{cite web |first=Nathanael |last=Johnson | name-list-style = vanc |work=Grist |date=July 8, 2013 |url=http://grist.org/food/the-genetically-modified-food-debate-where-do-we-begin/ |title=The genetically modified food debate: Where do we begin?}}</ref> that biotechnology is risky, that more information is needed and that consumers need control over whether to take such risks.<ref name=Hunt>{{cite journal | vauthors = Hunt L |year=2004 |title=Factors determining the public understanding of GM technologies |journal=AgBiotechNet |volume=6 |issue=128 |pages=1–8 |format=Review Article |url=http://www.ctu.edu.vn/~dvxe/doc/Factors%20determining%20%20understandingGMO.pdf |access-date=2012-09-16 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131102161620/http://www.ctu.edu.vn/~dvxe/doc/Factors%20determining%20%20understandingGMO.pdf |archive-date=2013-11-02 |url-status=dead }}</ref>{{R|Hunt}}<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Lazarus RJ |year=1991 |title=The Tragedy of Distrust in the Implementation of Federal Environmental Law |journal=Law and Contemporary Problems |volume=54 |issue=4 |pages=311–74 |url=http://scholarship.law.duke.edu/lcp/vol54/iss4/10 |jstor=1191880 |doi=10.2307/1191880}}</ref> A diffuse sense that social and technological change is accelerating, and that people cannot affect this context of change, becomes focused when such changes affect food.{{R|Hunt}} Leaders in driving public perception of the harms of such food in the media include [[Jeffrey M. Smith]], [[Dr. Oz]], [[Oprah]], and [[Bill Maher]];{{R|NYTimesQuest}}<ref>{{cite web |vauthors=Kloor K |work=Discover Magazine |date=October 19, 2012 |url=http://blogs.discovermagazine.com/collideascape/2012/10/19/liberals-turn-a-blind-eye-to-crazy-talk-on-gmos/#.Uueb32Qo5GG |title=Liberals Turn a Blind Eye to Crazy Talk on GMOs |access-date=January 28, 2014 |archive-date=November 19, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191119061536/http://blogs.discovermagazine.com/collideascape/2012/10/19/liberals-turn-a-blind-eye-to-crazy-talk-on-gmos/#.Uueb32Qo5GG |url-status=dead }}</ref> organizations include Organic Consumers Association,<ref>{{cite web|vauthors=Hughlett M|work=Star Tribune (Minneapolis) for the Wichita Eagle|date=5 November 2013|url=http://www.kansas.com/2013/11/05/3092814/firebrand-activist-leads-organic.html|title=Firebrand activist leads organic consumers association|access-date=January 28, 2014|archive-date=February 2, 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140202233957/http://www.kansas.com/2013/11/05/3092814/firebrand-activist-leads-organic.html|url-status=dead}}</ref> Greenpeace (especially with regard to [[Golden rice]])<ref name=pmid24052276>{{cite journal |vauthors=Alberts B, Beachy R, Baulcombe D, Blobel G, Datta S, Fedoroff N, Kennedy D, Khush GS, Peacock J, Rees M, Sharp P |title=Standing up for GMOs |journal=Science |volume=341 |issue=6152 |pages=1320 |year=2013 |pmid=24052276 |doi=10.1126/science.1245017|bibcode=2013Sci...341.1320A |doi-access=free }}</ref> and Union of Concerned Scientists.{{R|GristBegin}}<ref>{{cite web | vauthors = Wendel JA |work=Genetic Literacy Project |date=10 September 2013 |url=http://www.geneticliteracyproject.org/2013/09/10/223104/ |title=Scientists, journalists and farmers join lively GMO forum}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |vauthors=Kloor K |work=Discover Magazine's CollideAScape |date=22 August 2014 |url=http://blogs.discovermagazine.com/collideascape/2014/08/22/gmos-double-standards-union-concerned-scientists/#.VGzlVvnF-rN |title=On Double Standards and the Union of Concerned Scientists |access-date=November 19, 2014 |archive-date=November 20, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191120030947/http://blogs.discovermagazine.com/collideascape/2014/08/22/gmos-double-standards-union-concerned-scientists/#.VGzlVvnF-rN |url-status=dead }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |publisher=Union of Concerned Scientists |url=http://www.ucsusa.org/food_and_agriculture/our-failing-food-system/genetic-engineering/alternatives-to-genetic.html#.VGznoPnF-rM |work=Alternatives to Genetic Engineering |title=Biotechnology companies produce genetically engineered crops to control insects and weeds and to manufacture pharmaceuticals and other chemicals. The Union of Concerned Scientists works to strengthen the federal oversight needed to prevent such products from contaminating our food supply. |access-date=November 19, 2014 |archive-date=October 30, 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20151030080755/http://www.ucsusa.org/food_and_agriculture/our-failing-food-system/genetic-engineering/alternatives-to-genetic.html#.VGznoPnF-rM |url-status=dead }}</ref><ref name=Marden>{{cite web | vauthors = Marden E |url=http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2236&context=bclr |title=Risk and Regulation: U.S. Regulatory Policy on Genetically Modified Food and Agriculture |work=44 B.C.L. Rev. 733 |date=2003 |quote=By the late 1990s, public awareness of GM foods reached a critical level and a number of public interest groups emerged to focus on the issue. One of the early groups to focus on the issue was Mothers for Natural Law ("MFNL"), an Iowa-based organization that aimed to ban GM foods from the market....The Union of Concerned Scientists ("UCS"), an alliance of 50,000 citizens and scientists, has been another prominent voice on the issue.... As the pace of GM products entering the market increased in the 1990s, UCS became a vocal critic of what it saw as the agency's collusion with industry and failure to fully take account of allergenicity and other safety issues.}}</ref> |

|||

Social science surveys have documented that individuals are more risk averse about food than institutions. There is widespread concern within the public about the risks of biotechnology, a desire for more information about the risks themselves and a desire for choice in being exposed to risk.<ref name=Hunt>{{cite journal |first1=Lesley |last1=Hunt |year=2004 |title=Factors determining the public understanding of GM technologies |journal=AgBiotechNet |volume=6 |issue=128 |pages=1–8 |format=Review Article |url=http://www.ctu.edu.vn/~dvxe/doc/Factors%20determining%20%20understandingGMO.pdf}}</ref><ref name=Hunt /><ref>{{cite journal |first1=Richard J |last1=Lazarus |year=1991 |title=The Tragedy of Distrust in the Implementation of Federal Environmental Law |journal=Law and Contemporary Problems |volume=54 |issue=4 |pages=311–74 |url=http://scholarship.law.duke.edu/lcp/vol54/iss4/10 |jstor=1191880 |doi=10.2307/1191880}}</ref> There is also a widespread sense that social and technological change is speeding up and people feel powerless to affect this change; diffuse anxiety driven by this context becomes focused when it is food that is being changed.<ref name=Hunt /> |

|||

In the United States support or opposition or skepticism about GMO food is not divided by traditional partisan (liberal/conservative) lines, but young adults are more likely to have negative opinions on genetically modified food than older adults.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.foodnavigator-usa.com/Article/2016/12/02/Politics-demographics-don-t-explain-GMO-attitudes-say-Pew|title = Pew Research Center: The GMO debate is hugely polarizing, but the divide 'does not fall along familiar political fault lines'| date=December 2, 2016 }}</ref> |

|||

[[Religious views on genetically modified foods|Religious groups]] have raised concerns over whether genetically modified food will remain [[kosher]] or [[halal]]. In 2001 no such foods had been designated as unacceptable by Orthodox rabbis or Muslim leaders.<ref>[http://www.cnie.org/NLE/CRSreports/Science/st-41.pdf Food Biotechnology in the United States: Science, Regulation, and Issues] ''Congressional Research Service: The Library of Congress'' 2001</ref> However, there are Jewish groups that dispute this designation.<ref>{{cite news|title=GMOs, A Global Debate: Israel a Center for Study, Kosher Concerns|author=Marlene-Aviva Grunpeter|newspaper= Epoch Times|date=August 5, 2013|url=http://www.theepochtimes.com/n3/229556-gmos-a-global-debate-israel-a-center-for-study-kosher-concerns/}}</ref> |

|||

[[Religious views on genetically modified foods|Religious groups]] have raised concerns over whether genetically modified food will remain [[kosher]] or [[halal]]. In 2001, no such foods had been designated as unacceptable by Orthodox rabbis or Muslim leaders.<ref>[http://www.cnie.org/NLE/CRSreports/Science/st-41.pdf Food Biotechnology in the United States: Science, Regulation, and Issues] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20091228213934/http://www.cnie.org/NLE/CRSreports/Science/st-41.pdf |date=December 28, 2009 }} ''Congressional Research Service: The Library of Congress'' 2001</ref> |

|||

Genetically modified organisms have come to be seen by the public as "unnatural" which creates a negative [[halo effect]] over food that includes them.<ref>Maria Konnikova for the New Yorker. August 8, 2013 [http://www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/elements/2013/08/the-psychology-of-distrusting-gmos.html The Psychology of Distrusting G.M.O.s]</ref> Some groups or individuals see the generation and use of such organisms as intolerable meddling with biological states or processes that have naturally evolved over long periods of time, while others are concerned about the limitations of modern science to fully comprehend all of the potential negative ramifications of genetic manipulation.<ref name=autogenerated2>{{cite web|url=http://www.gmcontaminationregister.org/ |title=GM Contamination Register Official Website |publisher=Gmcontaminationregister.org |accessdate=2013-05-30}}</ref> Other people see genetic engineering as a continuation in the role humanity has occupied for thousands of years in [[selective breeding]].<ref>{{cite news | url=http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/11/01/genetically-engineered-food-health_n_2041372.html | title=Can Genetically Engineered Foods Harm You? | publisher=[[Huffington Post]] | date=1 November 2012 | accessdate=7 September 2013 | author=Borel, Brooke}}</ref> |

|||

Food writer [[Michael Pollan]] does not oppose eating genetically modified foods, but supports mandatory labeling of GM foods and has criticized the [[intensive farming]] enabled by certain GM crops, such as [[glyphosate]]-tolerant ("Roundup-ready") corn and soybeans.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/02/opinion/gmo-labeling-law-could-stir-a-revolution.html|title=Opinion {{!}} G.M.O. Labeling Law Could Stir a Revolution| vauthors = Bittman M |date=2016-09-02|work=The New York Times|access-date=2019-01-07|language=en-US|issn=0362-4331}}</ref> He has also expressed concerns about biotechnology companies holding the [[intellectual property]] of the foods people depend on, and about the effects of the growing corporatization of large-scale agriculture.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://opensource.com/life/10/1/what-if-we-open-sourced-genetic-engineering|title=What if we open sourced genetic engineering? | Opensource.com|website=opensource.com}}</ref> To address these problems, Pollan has brought up the idea of [[Open-source model|open sourcing]] GM foods. The idea has since been adopted to varying degrees by companies like [[Syngenta]],<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.geneticliteracyproject.org/2013/04/08/can-syngenta-help-make-open-source-gmos-a-reality/ |title=Can Syngenta help make open-source GMOs a reality? | vauthors = Fecht S |date=8 April 2013 }}</ref> and is being promoted by organizations such as the [[New America Foundation]].<ref>{{cite journal |url=http://www.slate.com/articles/technology/future_tense/2013/07/open_source_gmos_to_fight_climate_change_and_take_down_monsanto.html |title=Let's Make Genetically Modified Food Open-Source | vauthors = Kaufman F |date=9 July 2013 |journal=Slate}}</ref> Some organizations, like The BioBricks Foundation, have already worked out open-source licenses that could prove useful in this endeavour.<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Deibel E |title=Open Genetic Code: on open source in the life sciences |journal=Life Sciences, Society and Policy |volume=10 |pages=2 |date=9 January 2014 |pmid=26573980 |pmc=4513027 |doi=10.1186/2195-7819-10-2 |doi-access=free }}</ref> |

|||

With respect to environmental aspects, [[Friends of the Earth]],<ref>{{cite web|title=Genetic engineering|publisher=Friends of the Earth|url=http://www.foe.org/projects/food-and-technology/genetic-engineering}}</ref> an international network of environmental organizations, include genetics engineering as part of their environmental and political concerns. Other groups like [[GMWatch]] and [[The Institute of Science in Society]] concentrate mostly or solely on opposing genetically modified crops.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.i-sis.org.uk/GE-agriculture.php|title=GE-Agriculture|publisher=The Institute of Science in Society}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.gmwatch.org/about|title=About GMWatch|publisher=GMWatch}}</ref> |

|||

===Reviews and polls=== |

===Reviews and polls=== |

||

An ''[[EMBO Reports]]'' article in 2003 reported that the ''Public Perceptions of Agricultural Biotechnologies in Europe'' project (PABE)<ref>{{cite web |url=http://csec.lancs.ac.uk/archive/pabe/ |title=Public Perceptions of Agricultural Biotechnologies in Europe homepage |access-date=26 October 2014}}</ref> found the public neither accepting nor rejecting GMOs. Instead, PABE found that public had "key questions" about GMOs: "Why do we need GMOs? Who benefits from their use? Who decided that they should be developed and how? Why were we not better informed about their use in our food, before their arrival on the market? Why are we not given an effective choice about whether or not to buy these products? Have potential long-term and irreversible consequences been seriously evaluated, and by whom? Do regulatory authorities have sufficient powers to effectively regulate large companies? Who wishes to develop these products? Can controls imposed by regulatory authorities be applied effectively? Who will be accountable in cases of unforeseen harm?"{{R|Marris2001}} PABE also found that the public's scientific knowledge does not control public opinion, since scientific facts do not answer these questions.{{R|Marris2001}} PABE also found that the public does not demand "zero risk" in GM food discussions and is "perfectly aware that their lives are full of risks that need to be counterbalanced against each other and against the potential benefits. Rather than zero risk, what they demanded was a more realistic assessment of risks by regulatory authorities and GMO producers."{{R|Marris2001}} |

|||

In 2006, the Pew Initiative on Food and Biotechnology made public a review of U.S. survey results from 2001-2006.<ref name=Pew2006>Memo from The Mellman Group, Inc. to The Pew Initiative On Food And Biotechnology, 16 November 2006. [http://www.pewtrusts.org/uploadedFiles/wwwpewtrustsorg/Public_Opinion/Food_and_Biotechnology/2006summary.pdf Review Of Public Opinion Research]</ref> The review showed that Americans' knowledge of genetically modified foods and animals was low through the period. During this period there were protests against [[Calgene]]'s [[Flavr Savr]] [[transgenic]] tomato that described the GM tomato as being made with fish genes, confusing it with [[DNA Plant Technology]]'s [[Fish tomato]] experimental transgenic organism, which was never commercialized.<ref>Jennie Addario. Ryerson Review of Journalism. Spring, 2002. [http://www.rrj.ca/m3484/ Horror Show: Why the debate over genetically modified organisms and other complex science stories freak out newspapers]</ref><ref>Example of protester confusion. Sara Chamberlain. New Internationalist Magazine. Issued 293. Published on 5 August 1997 [http://www.newint.org/features/1997/08/05/food/ "Sara Chamberlain Dissects The Food That We Eat And Finds Some Alarming Ingredients. Article On Genetically Engineered/modified Foods For New Internationalist Magazine"] Quote: "What would you think if I said that your dinner resembles Frankenstein an unnatural hodgepodge of alien ingredients? Fish genes are swimming in your tomato sauce, microscopic bacterial genes in your tortillas, and your veg curry has been spiked with viruses."</ref> |

|||

In 2006, the Pew Initiative on Food and Biotechnology made public a review of U.S. survey results between 2001 and 2006.<ref name=Pew2006>{{cite web |title=Memo from The Mellman Group, Inc. to The Pew Initiative On Food And Biotechnology |date=16 November 2006 |url=http://www.pewtrusts.org/uploadedFiles/wwwpewtrustsorg/Public_Opinion/Food_and_Biotechnology/2006summary.pdf |work=Review Of Public Opinion Research |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110505232632/http://www.pewtrusts.org/uploadedFiles/wwwpewtrustsorg/Public_Opinion/Food_and_Biotechnology/2006summary.pdf |archive-date=May 5, 2011 |url-status=dead}}</ref> The review showed that Americans' knowledge of GM foods and animals was low throughout the period. Protests during this period against [[Calgene]]'s [[Flavr Savr]] GM tomato mistakenly described it as containing fish genes, confusing it with [[DNA Plant Technology]]'s [[fish tomato]] experimental [[transgenic]] organism, which was never commercialized.<ref>{{cite web |first=Jennie |last=Addario | name-list-style = vanc |work=Ryerson Review of Journalism.= |date=Spring 2002 |url=http://rrj.ca/horror-show/ |title=Horror Show: Why the debate over genetically modified organisms and other complex science stories freak out newspapers}}</ref><ref>Example of protester confusion. {{cite web |first=Sara |last=Chamberlain | name-list-style = vanc |work=New Internationalist Magazine |issue=293 |date=5 August 1997 |url=http://www.newint.org/features/1997/08/05/food/ |title=Sara Chamberlain Dissects The Food That We Eat And Finds Some Alarming Ingredients. Article On Genetically Engineered/modified Foods For New Internationalist Magazine |quote=What would you think if I said that your dinner resembles Frankenstein an unnatural hodgepodge of alien ingredients? Fish genes are swimming in your tomato sauce, microscopic bacterial genes in your tortillas, and your veg curry has been spiked with viruses.}}</ref> |

|||

A survey in 2007 by the [[Food Standards Australia New Zealand]] found that in Australia, where labeling is mandatory,<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.foodstandards.gov.au/consumerinformation/gmfoods/gmlabelling.cfm |title=Genetically modified (GM) foods |publisher=Food Standards Australia and New Zealand |date=4 October 2012 |access-date=5 November 2012 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130411092126/http://www.foodstandards.gov.au/consumerinformation/gmfoods/gmlabelling.cfm |archive-date=11 April 2013 }}</ref> 27% of Australians checked product labels to see whether GM ingredients were present when initially purchasing a food item.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.foodstandards.gov.au/scienceandeducation/publications/consumerattitiudes |title=Consumer Attitudes Survey 2007, A benchmark survey of consumers' attitudes to food issues |publisher=Food Standards Australia New Zealand |date=January 2008 |access-date=5 November 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110217031329/http://www.foodstandards.gov.au/scienceandeducation/publications/consumerattitiudes/ |archive-date=February 17, 2011}}</ref> |

|||

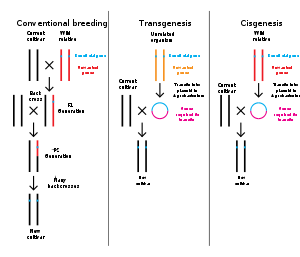

A review article about European consumer polls as of 2009 concluded that opposition to GMOs in Europe has been gradually decreasing,<ref name=GMOCompass1>{{cite web |url=http://www.gmo-compass.org/eng/news/stories/415.an_overview_european_consumer_polls_attitudes_gmos.html |title=Opposition decreasing or acceptance increasing?: An overview of European consumer polls on attitudes to GMOs |work=GMO Compass |date=16 April 2009 |access-date=10 October 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121008055224/http://www.gmo-compass.org/eng/news/stories/415.an_overview_european_consumer_polls_attitudes_gmos.html |archive-date=2012-10-08 |url-status=dead }}</ref> and that about 80% of respondents did not "actively avoid GM products when shopping". The 2010 "[[Eurobarometer]]" survey,<ref>{{cite web | vauthors = Gaskell G, Stares S, Allansdottir A, Allum N, Castro P, Esmer Y, Fischer C, Jackson J, Kronberger N, Hampel J, Mejlgaard N, Quintanilha A, Rammer A, Revuelta G, Stonemason P, Torgersen H, Wagner W | name-list-style = vanc | display-authors = 6 |date=October 2010 |url=http://ec.europa.eu/research/science-society/document_library/pdf_06/europeans-biotechnology-in-2010_en.pdf |title=Europeans and Biotechnology in 2010: Winds of change? |work=A report to the European Commission's Directorate-General for Research] European Commission Directorate-General for Research 2010 Science in Society and Food, Agriculture & Fisheries, & Biotechnology, EUR 24537 EN}}</ref> which assesses public attitudes about biotech and the life sciences, found that [[cisgenic]]s, GM crops made from plants that are crossable by [[Hybrid (biology)|conventional breeding]], evokes a smaller reaction than transgenic methods, using genes from species that are [[Taxonomy (biology)|taxonomically]] very different.<ref name=Gaskell_2011>{{cite journal |vauthors=Gaskell G, Allansdottir A, Allum N, Castro P, Esmer Y, Fischler C, Jackson J, Kronberger N, Hampel J, Mejlgaard N, Quintanilha A, Rammer A, Revuelta G, Stares S, Torgersen H, Wager W | display-authors = 6 |title=The 2010 Eurobarometer on the life sciences |journal=Nature Biotechnology |volume=29 |issue=2 |pages=113–14 |date=February 2011 |pmid=21301431 |doi=10.1038/nbt.1771| s2cid = 1709175 }}</ref> Eurobrometer survey in 2019 reported that most Europeans do not care about GMO when the topic is not presented explicitly, and when presented only 27% choose it as a concern. In just nine years since identical survey in 2010 the level of concern has halved in 28 EU Member States. Concern about specific topics decreased even more, for example genome editing on its own only concerns 4%.<ref name=":0">{{Cite web|title=2019 Eurobarometer Reveals Most Europeans Hardly Care About GMOs|url=http://www.isaaa.org/kc/cropbiotechupdate/article/default.asp?ID=17573|website=Crop Biotech Update|language=en|access-date=2020-05-22}}</ref> |

|||

A Deloitte survey in 2010 found that 34% of U.S. consumers were very or extremely concerned about GM food, a 3% reduction from 2008.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.deloitte.com/assets/Dcom-UnitedStates/Local%20Assets/Documents/Consumer%20Business/us_cp_2010FoodSurveyFactSheetGeneticallyModifiedFoods_05022010.pdf |title=Deloitte 2010 Food Survey – Genetically Modified Foods|access-date=10 October 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101227135642/http://www.deloitte.com/assets/Dcom-UnitedStates/Local%20Assets/Documents/Consumer%20Business/us_cp_2010FoodSurveyFactSheetGeneticallyModifiedFoods_05022010.pdf |archive-date=December 27, 2010}}</ref> The same survey found gender differences: 10% of men were extremely concerned, compared with 16% of women, and 16% of women were unconcerned, compared with 27% of men. |

|||

A poll by ''The New York Times'' in 2013 showed that 93% of Americans wanted labeling of GM food.<ref>{{cite news |first=Allison |last=Kopeck | name-list-style = vanc |work=The New York Times |date=July 27, 2013 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2013/07/28/science/strong-support-for-labeling-modified-foods.html?_r=0 |title=Strong Support for Labeling Modified Foods}}</ref> |

|||

The 2013 vote, rejecting Washington State's GM food labeling [[Washington Initiative 522, 2012|I-522]] referendum came shortly after<ref>{{cite web |first=Nina |last=Shapiro |name-list-style=vanc |work=Seattle Weekly |date=October 24, 2013 |url=http://www.seattleweekly.com/music/949524-129/consensus-gmos-statement-benbrook-crops-gmo |title=GMOs: Group Refutes Claim of 'Scientific Consensus' |access-date=November 16, 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131028130144/http://www.seattleweekly.com/music/949524-129/consensus-gmos-statement-benbrook-crops-gmo |archive-date=October 28, 2013 |url-status=dead }}</ref> the 2013 [[World Food Prize]] was awarded to employees of [[Monsanto]] and [[Syngenta]].<ref name=FoodProcessing>{{cite web |first=Dave |last=Fusaro | name-list-style = vanc |work=Food Processing |date=November 7, 2013 |url=http://www.foodprocessing.com/articles/2013/european-scientists-ask-for-gmo-research/ |title=European Scientists Ask for GMO Research}}</ref> The award has drawn criticism from opponents of genetically modified crops.<ref name=Temps>{{cite news |first=Catherine |last=Morand | name-list-style = vanc |title=Le prix mondial de l'alimentation à Monsanto et Syngenta? Une farce | trans-title = The World Food Prize Monsanto and Syngenta? A joke |language=fr |work=[[Le Temps]] |date=16 October 2013 }}</ref><ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.huffingtonpost.com/frances-moore-lappe-and-anna-lappe/choice-of-monsanto-betray_b_3499045.html?ak_proof=1 |work=Huffington Post |title=Choice of Monsanto Betrays World Food Prize Purpose, Say Global Leaders |date=26 June 2013}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |title=And The Winner Of The World Food Prize Is ... The Man From Monsanto |newspaper = NPR|url=https://www.npr.org/blogs/thesalt/2013/06/19/193447482/and-the-winner-of-the-world-food-prize-is-the-man-from-monsanto?ak_proof=1 |publisher=National Public Radio |date=19 June 2013|last1 = Charles|first1 = Dan}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |title=Energy-environment world food prize event in Iowa confronts divisive issues of biotech crops and global warming |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/energy-environment/world-food-prize-event-in-iowa-confronts-divisive-issues-of-biotech-crops-and-global-warming/2013/10/15/8ed1c2b4-35c7-11e3-89db-8002ba99b894_story.html |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181208222251/https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/energy-environment/world-food-prize-event-in-iowa-confronts-divisive-issues-of-biotech-crops-and-global-warming/2013/10/15/8ed1c2b4-35c7-11e3-89db-8002ba99b894_story.html |url-status=dead |archive-date=8 December 2018 | access-date = 1 October 2013 |newspaper=Washington Post}}</ref> |

|||

With respect to the question of "Whether GMO foods were safe to eat", the gap between the opinion of the public and that of [[American Association for the Advancement of Science]] scientists is very wide with 88% of AAAS scientists saying yes in contrast to 37% of the general public.<ref name=PEW>{{cite web |first1=Cary |last1=Funk |first2=Lee |last2=Rainie |name-list-style=vanc |title=Public and Scientists' Views on Science and Society |url=http://www.pewinternet.org/files/2015/01/PI_ScienceandSociety_Report_012915.pdf |website=pewinternet.org |publisher=Pew Research Center |access-date=April 28, 2015 |page=37 |format=Full report PDF file |date=January 29, 2015 |quote=Fully 88% of AAAS scientists say it is generally safe to eat genetically modified (GM) foods compared with 37% of the general public who say the same, a gap of 51 percentage points. |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150429154007/http://www.pewinternet.org/files/2015/01/PI_ScienceandSociety_Report_012915.pdf |archive-date=April 29, 2015 |url-status=dead }}[http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/01/29/public-and-scientists-views-on-science-and-society/ Link to key data] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190109232405/http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/01/29/public-and-scientists-views-on-science-and-society/ |date=January 9, 2019 }}</ref> |

|||

===Public relations campaigns and protests=== |

|||

[[File:Monsanto Protests in Washington DC - Stierch 02.JPG|thumb|Anti-GMO and anti-Monsanto protests in Washington, DC]] |

|||

[[File:2013, Stockholm Demonstration against Monsanto 04.jpg|thumb|right|March Against Monsanto in Stockholm, Sweden, May 2013]] |

|||

In May 2012, a group called "Take the Flour Back" led by Gerald Miles protested plans by a group from [[Rothamsted Experimental Station]], based in Harpenden, Hertfordshire, England, to conduct an experimental trial wheat genetically modified to repel [[aphids]].<ref>Take the Flour Back Press Release, 27/05/12 [http://taketheflourback.org/ European activists link up to draw the line against GM]</ref> The researchers, led by John Pickett, wrote a letter to the group in early May 2012, asking them to call off their protest, aimed for 27 May 2012.<ref>{{cite web |first=Alistair |last=Driver |name-list-style=vanc |work=Farmers Guardian |date=2 May 2012 |url=http://www.farmersguardian.com/home/arable/scientists-urge-protestors-not-to-trash-gm-trials/46673.article |title=Scientists urge protestors not to trash GM trials |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120903072513/http://www.farmersguardian.com/home/arable/scientists-urge-protestors-not-to-trash-gm-trials/46673.article |archive-date=3 September 2012 }}</ref> Group member Lucy Harrap said that the group was concerned about spread of the crops into nature, and cited examples of outcomes in the [[United States]] and [[Canada]].<ref>{{Cite news |url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-17928172 |work=BBC News |title=GM wheat trial belongs in a laboratory |date=2 May 2012}}</ref> Rothamsted Research and [[Sense about Science]] ran question and answer sessions about such a potential.<ref>{{Cite news |url=http://www.senseaboutscience.org/pages/plant-science-qa.html |work=Sense about Science |title=Don't Destroy Research Q & A |date=25 July 2012 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121018231124/http://www.senseaboutscience.org/pages/plant-science-qa.html |archive-date=18 October 2012 }}</ref> |

|||

The [[March Against Monsanto]] is an international [[grassroots]] movement and protest against [[Monsanto]] corporation, a producer of [[genetically modified organism]] (GMOs) and [[Roundup (herbicide)|Roundup]], a [[glyphosate]]-based [[herbicide]].{{R|AP-Guardian}} The movement was founded by Tami Canal in response to the failure of [[California Proposition 37 (2012)|California Proposition 37]], a ballot initiative which would have required labeling food products made from GMOs. Advocates support mandatory labeling laws for food made from GMOs .<ref name=PostCourier>{{cite web |last=Quick |first=David | name-list-style = vanc |date=26 May 2013 |url=http://www.postandcourier.com/article/20130526/PC16/130529414 |title=More than 100 participate in Charleston's March Against Monsanto, one of 300+ in world on Saturday |work=The Post and Courier | access-date = 18 June 2013}}</ref> |

|||

The initial march took place on May 25, 2013. The number of protesters who took part is uncertain; figures of "hundreds of thousands" and the organizers' estimate of "two million"<ref name=AP>"[https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/world/2013/05/25/global-protests-monsanto/2361007/ Protesters Around the World March Against Monsanto]". ''USA Today''. Associated Press. 26 May 2013. Retrieved 18 June 2013.</ref> were variously cited. Events took place in between 330{{R|PostCourier}} and 436{{R|AP}} cities around the world, mostly in the United States.{{R|PostCourier|LAT}} Many protests occurred in Southern California, and some participants carried signs expressing support for mandatory labeling of GMOs that read "Label GMOs, It's Our Right to Know", and "Real Food 4 Real People".<ref name=LAT>Xia, Rosanna (28 May 2013). "[https://www.latimes.com/local/lanow/la-me-ln-monsanto-protest-20130525,0,6534145.story Hundreds in L.A. march in global protest against Monsanto, GMOs]". ''Los Angeles Times''. Retrieved 18 June 2013.</ref> Canal said that the movement would continue its "anti-GMO cause" beyond the initial event.{{R|AP}} Further marches occurred in October 2013 and in May 2014 and 2015. The protests were reported by news outlets including [[ABC News (United States)|ABC News]],<ref name=ABC>{{cite web |url=https://abcnews.go.com/search?searchtext=%22March%20against%20monsanto%22#0_ |title=Search Results for "March against monsanto" |work=ABC News}}</ref> the [[Associated Press]],{{R|AP}} ''[[The Washington Post]]'',<ref name=TWP>"[https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/economy/monsanto-protests-around-the-world/2013/05/30/a0ec8b40-c976-11e2-9245-773c0123c027_gallery.html#photo=1 Monsanto protests around the world]". ''The Washington Post''. 25 May 2013. Retrieved 18 June 2013.</ref> ''[[The Los Angeles Times]]'',{{R|LAT}} ''[[USA Today]]'',{{R|AP}} and [[CNN]] (in the United States), and ''[[The Guardian]]''<ref name="AP-Guardian">Associated Press, 25 May 2013 in ''The Guardian''. [https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2013/may/26/millions-march-against-monsanto?INTCMP=SRCH Millions march against GM crops]</ref> (outside the United States). |

|||

Monsanto said that it respected people's rights to express their opinion on the topic, but maintained that its seeds improved agriculture by helping farmers produce more from their land while conserving resources, such as water and energy.{{R|AP}} The company reiterated that [[genetically modified foods]] were safe and improved crop yields.<ref name=WELL>{{cite web |last=Moayyed |first=Mava | name-list-style = vanc |date=27 May 2013 |url=http://www.stuff.co.nz/dominion-post/news/local-papers/the-wellingtonian/8720969/Marching-against-genetic-engineering |title=Marching against genetic engineering |work=The Wellingtonians | access-date = 21 June 2013}}</ref> Similar sentiments were expressed by the Hawaii Crop Improvement Association, of which Monsanto is a member.<ref name=TMN1>{{cite web |last=Perry |first=Brian | name-list-style = vanc |date=26 May 2013 |url=http://www.mauinews.com/page/content.detail/id/573065/Protesters-against-GMOs--but-Monsanto-says-crops-are-safe.html |title=Protesters against GMOs, but Monsanto says crops are safe |work=The Maui News | access-date = 21 June 2013}}</ref><ref name=HCIA>{{cite web |url=http://www.hciaonline.com/ |title=Hawaii Crop Improvement Association | access-date = 21 June 2013}}</ref> |

|||

In July 2013, the agricultural biotechnology industry launched a GMO transparency initiative called [[GMO Answers]] to address consumers' questions about GM foods in the U.S. food supply.<ref name=nytimes>{{cite web |last1=Pollack |first1=Andrew | name-list-style = vanc |title=Seeking Support, Biotech Food Companies Pledge Transparency |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2013/07/29/business/seeking-support-biotech-food-companies-pledge-transparency.html |work=[[The New York Times]] |date=28 July 2013 | access-date = 19 June 2014}}</ref> GMO Answers' resources included [[Conventional farming|conventional]] and [[Organic farming|organic farmers]], [[agribusiness]] experts, scientists, academics, medical doctors and nutritionists, and "company experts" from founding members of the Council for Biotechnology Information, which funds the initiative.<ref name=experts>{{cite web |title=Experts |url=http://gmoanswers.com/experts |publisher=GMO Answers|access-date=19 June 2014}}</ref> Founding members include [[BASF]], [[Bayer CropScience]], [[Dow AgroSciences]], [[DuPont Pioneer|DuPont]], Monsanto Company and Syngenta.<ref>{{cite web |title=The Council for Biotechnology Information: Founding Members |url=http://gmoanswers.com/about |publisher=GMO Answers|access-date=28 June 2014}}</ref> |

|||

In October 2013, a group called The [[European Network of Scientists for Social and Environmental Responsibility]] (ENSSER), posted a statement claiming that there is no scientific consensus on the safety of GMOs,<ref>[http://www.ensser.org/increasing-public-information/no-scientific-consensus-on-gmo-safety/ Statement: No scientific consensus on GMO safety] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131123055321/http://www.ensser.org/increasing-public-information/no-scientific-consensus-on-gmo-safety/ |date=2013-11-23 }}, ENSSER, 10/21/2013</ref> which was signed by about 200 scientists in various fields in its first week.{{R|FoodProcessing}} On January 25, 2015, their statement was formally published as a whitepaper by Environmental Sciences Europe:<ref>{{cite journal |title=No scientific consensus on GMO safety | vauthors = Hilbeck A, Binimelis R, Defarge N, Steinbrecher R, Székács A, Wickson F, Antoniou M, Bereano PL, Clark EA, Hansen M, Novotny E, Heinemann J, Meyer H, Shiva V, Wynne B | display-authors = 6 |journal= Environmental Sciences Europe |date=2015 |volume=27 |issue=4 |pages=1–6 |doi=10.1186/s12302-014-0034-1 |s2cid=85597477 |url=http://www.enveurope.com/content/pdf/s12302-014-0034-1.pdf | doi-access = free }}</ref> |

|||

====Direct action==== |

|||

[[Earth Liberation Front]], Greenpeace and others have disrupted GMO research around the world.<ref name=oregon>{{cite web |url=http://www.biofortified.org/2013/06/gmo-crops-vandalized-in-oregon/ |title=GMO crops vandalized in Oregon |first=Karl Haro |last=von Mogel | name-list-style = vanc |work=[[Biology Fortified]] |date=24 June 2013}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2013/02/130228124134.htm |title=Fighting GM Crop Vandalism With a Government-Protected Research Site |work=[[Science Daily]] |date=28 February 2013}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |url=http://www.abc.net.au/news/2013-09-20/scientists-speak-out-against-vandalism-of-gm-rice/4970626 |title=Scientists speak out against vandalism of genetically modified rice |work=[[Australian Broadcasting Corporation]] |date=20 September 2013}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.salon.com/2013/09/30/vandals_hack_down_hawaiis_genetically_modified_papaya_trees/ |title=Vandals hack down Hawaii's genetically modified papaya trees: The destruction is believed to have been the work of anti-GMO activists |first=Lindsay |last=Abrams | name-list-style = vanc |work=Salon |date=30 September 2013}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.geneticliteracyproject.org/2013/06/25/oregon-genetically-modified-crops-vandalized |title=Oregon: Genetically modified crops vandalized |first=Karl Haro |last=von Mogel | name-list-style = vanc |work=Genetic Literacy Project |date=25 June 2013}}</ref> Within the UK and other European countries, as of 2014 80 crop trials by academic or governmental research institutes had been destroyed by protesters.<ref name=kuntz>{{cite journal |vauthors=Kuntz M |title=Destruction of public and governmental experiments of GMO in Europe |journal=GM Crops & Food |volume=3 |issue=4 |pages=258–64 |year=2012 |pmid=22825391 |doi=10.4161/gmcr.21231|doi-access=free }}</ref> In some cases, threats and violence against people or property were carried out.{{R|kuntz}} In 1999, activists burned the biotech lab of [[Michigan State University]], destroying the results of years of work and property worth $400,000.<ref name=why>{{cite web |url=http://reason.com/archives/2001/01/01/dr-strangelunch |title=Dr. Strangelunch Or: Why we should learn to stop worrying and love genetically modified food |work=[[Reason (magazine)|The Reason]] |first=Ronald |last=Bailey | name-list-style = vanc |date=January 2001}}</ref> |

|||

In 1987, the ice-minus strain of ''P. syringae'' became the first [[genetically modified organism|genetically modified organism (GMO)]] to be released into the environment<ref name=BBC2002>BBC News 14 June 2002 [http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/2045286.stm GM crops: A bitter harvest?]</ref> when a strawberry field in California was sprayed with the bacteria. This was followed by the spraying of a crop of potato seedlings.<ref>{{cite web |first=Thomas H. |last=Maugh | name-list-style = vanc |work=Los Angeles Times |date=9 June 1987 |url=https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1987-06-09-mn-6024-story.html |title=Altered Bacterium Does Its Job: Frost Failed to Damage Sprayed Test Crop, Company Says}}</ref> The plants in both test fields were uprooted by activist groups, but were re-planted the next day.{{R|BBC2002 }} |

|||

In 2011, Greenpeace paid reparations when its members broke into the premises of an Australian scientific research organization, [[CSIRO]], and destroyed a genetically modified wheat plot. The sentencing judge accused Greenpeace of cynically using junior members to avoid risking their own freedom. The offenders were given 9-month suspended sentences.{{R|oregon}}<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.smh.com.au/environment/greenpeace-activists-in-costly-gm-protest-20120802-23i0t.html |title=Greenpeace activists in costly GM protest |newspaper=Sydney Morning Herald |date=2012-08-02| access-date=2013-11-08}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |url=http://www.canberratimes.com.au/act-news/gm-crop-destroyers-given-suspended-sentences-20121119-29l66.html |title=GM crop destroyers given suspended sentences |newspaper=Canberra Times |date=2012-11-19| access-date=2013-11-08}}</ref> |

|||

On August 8, 2013 protesters uprooted an experimental plot of [[golden rice]] in the Philippines.<ref name=NYT82413>{{cite news |title=Golden Rice: Lifesaver? |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2013/08/25/sunday-review/golden-rice-lifesaver.html|access-date=August 25, 2013 |newspaper=The New York Times |date=24 August 2013 |first=Amy |last=Harmon | name-list-style = vanc |format=News Analysis}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |title=Militant Filipino farmers destroy Golden Rice GM crop |url=https://www.newscientist.com/article/dn24021-militant-filipino-farmers-destroy-golden-rice-gm-crop.html | access-date = 26 October 2013 |newspaper=NewScientist |date=9 August 2013 |first=Michael |last=Slezak | name-list-style = vanc}}</ref> British author, journalist, and environmental activist [[Mark Lynas]] reported in [[Slate (magazine)|''Slate'']] that the vandalism was carried out by a group led by the extreme-left Kilusang Magbubukid ng Pilipinas or Peasant Movement of the Philippines (KMP), to the dismay of other protesters.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.slate.com/blogs/future_tense/2013/08/26/golden_rice_attack_in_philippines_anti_gmo_activists_lie_about_protest_and.html |title=The True Story About Who Destroyed a Genetically Modified Rice Crop |first=Mark |last=Lynas | name-list-style = vanc |work=Slate |date=26 August 2013}}</ref> Golden rice is designed to prevent [[vitamin A]] deficiency which, according to [[Helen Keller International]], blinds or kills hundreds of thousands of children annually in developing countries.<ref name=bbcgolden>{{cite web |url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-23632042 |title='Golden rice' GM trial vandalised in the Philippines |work=BBC News |date=9 August 2013}}</ref> |

|||

A 2010 Deloitte survey found that 34% of U.S. consumers were very or extremely concerned about GM food, a 3% reduction from 2008.<ref>[http://www.deloitte.com/assets/Dcom-UnitedStates/Local%20Assets/Documents/Consumer%20Business/us_cp_2010FoodSurveyFactSheetGeneticallyModifiedFoods_05022010.pdf Deloitte 2010 Food Survey Genetically Modified Foods] retrieved 10 October 2012</ref> The same survey found a strong gender difference in opinion: 10% of men were extremely concerned, compared with 16% of women, and 16% of women were unconcerned, compared with 27% of men. A 2009 review article of European consumer polls concluded that opposition to GMOs in Europe has been gradually decreasing,<ref name = GMOCompass1>{{cite web |url=http://www.gmo-compass.org/eng/news/stories/415.an_overview_european_consumer_polls_attitudes_gmos.html |title=Opposition decreasing or acceptance increasing?: An overview of European consumer polls on attitudes to GMOs |work=GMO Compass |date=16 April 2009 |accessdate=10 October 2012}}</ref> and that about 80% of respondents did not "actively avoid GM products when shopping". The 2010 "Eurobarometer" survey,<ref>Gaskell G et al October 2010. [http://ec.europa.eu/research/science-society/document_library/pdf_06/europeans-biotechnology-in-2010_en.pdf Europeans and Biotechnology in 2010: Winds of change? A report to the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Research] European Commission Directorate-General for Research 2010 Science in Society and Food, Agriculture & Fisheries, & Biotechnology, EUR 24537 EN</ref> which assesses public attitudes about biotech and the life sciences in Europe, found that "[[cisgenic]]s, GM crops produced by adding only genes from the same species or from plants that are crossable by conventional breeding," evokes a different reaction than [[transgenic]] methods, where "genes are taken from other species or bacteria that are [[Taxonomy (biology)|taxonomically]] very different from the gene recipient and transferred into plants."<ref name="pmid21301431">{{cite journal | author = Gaskell G, Allansdottir A, Allum N, Castro P, Esmer Y, Fischler C, Jackson J, Kronberger N, Hampel J, Mejlgaard N, Quintanilha A, Rammer A, Revuelta G, Stares S, Torgersen H, Wager W | title = The 2010 Eurobarometer on the life sciences | journal = Nat. Biotechnol. | volume = 29 | issue = 2 | pages = 113–4 |date=February 2011 | pmid = 21301431 | doi = 10.1038/nbt.1771 }}</ref> A 2007 survey by the Food Standards Australia and New Zealand found that in Australia where labeling is mandatory,<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.foodstandards.gov.au/consumerinformation/gmfoods/gmlabelling.cfm |title=Genetically modified (GM) foods |publisher=Food Standards Australia and New Zealand |date=4 October 2012 |accessdate=5 November 2012}}</ref> 27% of Australians looked at the label to see if it contained GM material when purchasing a grocery product for the first time.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.foodstandards.gov.au/scienceandeducation/publications/consumerattitiudes |title=Consumer Attitudes Survey 2007, A benchmark survey of consumers' attitudes to food issues |publisher=Food Standards Australia New Zealand |date=January 2008 |accessdate=5 November 2012}}</ref> |

|||

=== Response to anti-GMO sentiment === |

|||

A 2013 poll by ''The New York Times'' showed that 93% of Americans wanted GMO labeling.<ref>Allison Kopicki for ''The New York Times,'' July 27, 2013 [http://www.nytimes.com/2013/07/28/science/strong-support-for-labeling-modified-foods.html?_r=0 Strong Support for Labeling Modified Foods]</ref> |

|||

In 2017, two documentaries were released which countered the growing anti-GMO sentiment among the public. These included ''[[Food Evolution]]''<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.slate.com/articles/health_and_science/science/2017/06/food_evolution_is_correct_on_gmos_and_unconvincing.html|title=Food Evolution Is Scientifically Accurate. Too Bad It Won't Convince Anyone|last1=Kloor|first1=Keith|website=Slate.com|date=June 23, 2017|publisher=Slate|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171119133701/http://www.slate.com/articles/health_and_science/science/2017/06/food_evolution_is_correct_on_gmos_and_unconvincing.html|archive-date=19 November 2017|url-status=live|access-date=19 November 2017}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.forbes.com/sites/kavinsenapathy/2017/09/25/neil-degrasse-tyson-drops-mic-on-comments-criticizing-hulu-for-showing-food-evolution-documentary/#44ca1e50503e|title=Neil DeGrasse Tyson Drops Mic On Comments Criticizing Hulu For Showing Food Evolution Documentary|last1=Senapathy|first1=Kavin|date=2017-09-25|website=Forbes|location=US|url-status=live|archive-url=https://archive.today/20200323004656/https://www.forbes.com/sites/kavinsenapathy/2017/09/25/neil-degrasse-tyson-drops-mic-on-comments-criticizing-hulu-for-showing-food-evolution-documentary/%233feb68ef503e|archive-date=2020-03-23}}</ref> and ''[[Science Moms]]''. Per the ''Science Moms'' director, the film "focuses on providing a science and evidence-based counter-narrative to the [[pseudoscience]]-based parenting narrative that has cropped up in recent years".<ref name="geneticliteracyproject">{{cite web|url=https://geneticliteracyproject.org/2017/11/08/science-moms-documentary-counters-anti-gmo-anti-vaccine-misinformation/|title='Science Moms' documentary counters anti-GMO, anti-vaccine misinformation|last1=Senapathy|first1=Kavin|date=2017-11-08|website=Genetic Literacy Project|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171118175300/https://geneticliteracyproject.org/2017/11/08/science-moms-documentary-counters-anti-gmo-anti-vaccine-misinformation/|archive-date=2017-11-18}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.siue.edu/news/2017/10/Hupp-ExecProducer-ScienceMoms.shtml|title=SIUE's Hupp Produces Skeptical Film Premiering this Weekend|last1=Hupp|first1=Stephen|website=SIUE.edu|publisher=Southern Illinois University Edwardsville|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171118181200/http://www.siue.edu/news/2017/10/Hupp-ExecProducer-ScienceMoms.shtml|archive-date=18 November 2017|url-status=live|access-date=18 November 2017}}</ref> |

|||

158 [[Nobel Prize|Nobel prize]] laureates in science have signed an open letter in 2016 in support of genetically modified farming and called for Greenpeace to cease its anti-scientific campaign, especially against the [[Golden rice|Golden Rice]].<ref>{{Cite web|title=Laureates Letter Supporting Precision Agriculture (GMOs) {{!}} Support Precision Agriculture|url=https://www.supportprecisionagriculture.org/nobel-laureate-gmo-letter_rjr.html|access-date=2021-10-05|website=www.supportprecisionagriculture.org}}</ref> |

|||

In October 2013, in reaction to the awarding of the 2013 World Food Prize to employees of Monsanto and Syngenta,<ref name=FoodProcessing>Dave Fusaro for Food Processing. November 7, 2013 [http://www.foodprocessing.com/articles/2013/european-scientists-ask-for-gmo-research/ European Scientists Ask for GMO Research]</ref> and just in time for the vote on the [[Washington Initiative 522, 2012|I-522]] referendum on food labeling,<ref>Nina Shapiro for Seattle Weekly. October 24, 2013. [http://www.seattleweekly.com/music/949524-129/consensus-gmos-statement-benbrook-crops-gmo GMOs: Group Refutes Claim of ‘Scientific Consensus’]</ref> the European Scientists for Social and Environmental Responsibilities (ENSSER), referred to as an "anti-GMO activist group" by the chair of the Agricultural Biotechnology Council's (ABC) of Australia,<ref>Philip Case for Farmer's Weekly. October 25, 2013 [http://www.fwi.co.uk/articles/25/10/2013/141698/scientific-consensus-on-gm-crops-safety-39overwhelming39.htm Scientific consensus on GM crops safety 'overwhelming']</ref> posted a statement claiming that there is no scientific consensus on the safety of GM foods,<ref>[http://www.ensser.org/increasing-public-information/no-scientific-consensus-on-gmo-safety/ Statement: No scientific consensus on GMO safety], ENSSER, 10/21/12013</ref> which was signed by about 200 scientists in various fields in its first week.<ref name=FoodProcessing/> |

|||

===Conspiracy theories=== |

|||

==Protests== |

|||

{{Main|GMO conspiracy theories}} |

|||

[[File:Monsanto Protests in Washington DC - Stierch 02.JPG|thumb|Anti-GMO and Anti-Monsanto protests in Washington, D.C.]] |

|||

There are various [[conspiracy theories]] related to the production and sale of [[genetically modified crops]] and [[genetically modified food]] that have been identified by some commentators such as [[Michael Shermer]].<ref name=Sheerer>{{cite web |last=Sheerer |first=Michael | name-list-style = vanc |url=http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/why-do-people-believe-in-conspiracy-theories/ |title=Why Do People Believe in Conspiracy Theories? |work=Scientific American |volume=311 |issue=6 |date=2014 |pages=94}}</ref> Generally, these conspiracy theories posit that GMOs are being knowingly and maliciously introduced into the food supply either as a means to unduly enrich agribusinesses or as a means to poison or pacify the population. |

|||

Concern about [[gene flow]] drives some protesters. In May 2012, a group called "Take the Flour Back" led by Gerald Miles protested against plans by a group from [[Rothamsted Experimental Station]], based in Harpenden, Hertfordshire, England, to stage an experimental trial to use genetically modified wheat to repel aphids.<ref>Take the Flour Back Press Release, 27/05/12 [http://taketheflourback.org/ European activists link up to draw the line against GM]</ref> The researchers, led by John Pickett, wrote a letter to the group "Take the Flour Back" in early May 2012, asking them to call off their protest, aimed for 27 May 2012.<ref>Alistair Driver for Farmers Guardian, 2 May 2012 [http://www.farmersguardian.com/home/arable/scientists-urge-protestors-not-to-trash-gm-trials/46673.article Scientists urge protestors not to trash GM trials]</ref> One of the members of Take the Flour Back, Lucy Harrap, said that the group was concerned about spread of the crops into nature, and cited examples of outcomes in the [[United States]] and [[Canada]].<ref>{{Cite news| url=http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-17928172 | work=BBC News | title=GM wheat trial belongs in a laboratory | date=2 May 2012}}</ref> Rothamsted Research and [[Sense About Science]] ran question and answer sessions with scientists about issues of contamination.<ref>{{Cite news| url=http://www.senseaboutscience.org/pages/plant-science-qa.html | work=Sense About Science| title=Don't Destroy Research Q & A | date=25 July 2012}}</ref> |

|||

A work seeking to explore risk perception over GMOs in [[Turkey]] identified a belief among the conservative political and religious figures who were opposed to GMOs that GMOs were "a conspiracy by Jewish Multinational Companies and Israel for world domination."<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Veltri GA, Suerdem AK |s2cid=22893955 |title=Worldviews and discursive construction of GMO-related risk perceptions in Turkey |language=en |journal=Public Understanding of Science |volume=22 |issue=2 |pages=137–54 |date=February 2013 |pmid=23833021 |doi=10.1177/0963662511423334|hdl=2381/28216 |url=https://figshare.com/articles/journal_contribution/10173569 |hdl-access=free }}</ref> Additionally, a [[Latvia]]n study showed that a segment of the population believed that GMOs were part of a greater conspiracy theory to poison the population of the country.<ref>{{cite journal |title=SHS Web of Conferences |url=http://www.shs-conferences.org/articles/shsconf/abs/2014/07/shsconf_shw2012_00048/shsconf_shw2012_00048.html |website=www.shs-conferences.org|doi=10.1051/shsconf/20141000048 |access-date = 2016-01-31|doi-access=free }}</ref> |

|||

On May 25, 2013, the [[March Against Monsanto]] movement held rallies in protest against companies like [[Monsanto#"March Against Monsanto" protests|Monsanto]] and the genetically modified seed they produce.<ref>[http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/05/25/march-against-monsanto-gmo-protest_n_3336627.html?ncid=txtlnkushpmg00000029&ir=Business Protesters Rally Against U.S. Seed Giant And GMO Products]. ''[[The Huffington Post]].'' Retrieved 25 May 2013</ref> According to the [[Associated Press]], rallies took place in [[Buenos Aires]] and other cities in Argentina, and in [[Portland, Oregon]] police estimate 6,000 protesters attended.<ref name="AP">Associated Press (May 25, 2013). [http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/world/2013/05/25/global-protests-monsanto/2361007/ Protesters around the world march against Monsanto]. ''USA Today''.</ref> According to the [[LA Times]], hundreds marched in Los Angeles.<ref>Xia, Rosanna (May 25, 2013). [http://www.latimes.com/local/lanow/la-me-ln-monsanto-protest-20130525,0,6534145.story Hundreds in L.A. march in global protest against Monsanto, GMOs]. ''Los Angeles Times''.</ref> According to [[CTV Television Network|CTV]], hundreds of people marched in Kitchener, Ontario.<ref name=CTV>CTV Kitchener (May 25, 2013). [http://kitchener.ctvnews.ca/march-against-monsanto-comes-to-king-street-in-kitchener-1.1296971 'March Against Monsanto' comes to King Street in Kitchener]. CTV Television Network.</ref> The total number of protesters who took part is uncertain; figures of "hundreds of thousands"<ref name="NYToranges">Amy Harmon, July 27, 2013 [http://www.nytimes.com/2013/07/28/science/a-race-to-save-the-orange-by-altering-its-dna.html?pagewanted=all&_r=1& A Race to Save the Orange by Altering Its DNA]</ref> or "two million"<ref name="AP">"[http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/world/2013/05/25/global-protests-monsanto/2361007/ Protesters Around the World March Against Monsanto]". ''USA Today''. Associated Press. 26 May 2013. Retrieved 18 June 2013.</ref> were variously cited.<ref>Note: Editors have been unable to locate any [[WP:RS|reliable source]] that applied [[crowd counting]] techniques to estimate the crowds. A few sources reported numbers in the hundreds of thousands; most sources followed an AP article that used the organizers' number of 2 million.</ref> According to organizers, protesters in 436 cities and 52 countries took part.<ref>[http://rt.com/news/monsanto-gmo-protests-world-721/ Challenging Monsanto: Over two million march the streets of 436 cities, 52 countries — RT News<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref><ref>[http://news.yahoo.com/millions-march-against-monsanto-over-400-cities-222259976.html Millions march against Monsanto in over 400 cities - Yahoo News<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref><ref name="PostCourier">Quick, David (26 May 2013). "[http://www.postandcourier.com/article/20130526/PC16/130529414 More than 100 participate in Charleston’s March Against Monsanto, one of 300+ in world on Saturday]". ''The Post and Courier''. Retrieved 18 June 2013.</ref> |

|||

==Lawsuits== |

|||

=== Vandalism and threats === |

|||

{{See also|#Lawsuits filed against farmers for patent infringement|#Litigation and regulation disputes}} |

|||

===''Foundation on Economic Trends v. Heckler''=== |

|||

[[Earth Liberation Front]], [[Greenpeace]], and others have vandalized GMO research around the world.<ref name=oregon>[http://www.biofortified.org/2013/06/gmo-crops-vandalized-in-oregon/ GMO crops vandalized in Oregon], Karl Haro von Mogel, [[Biology Fortified]], 24 June 2013.</ref><ref>[http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2013/02/130228124134.htm Fighting GM Crop Vandalism With a Government-Protected Research Site], [[Science Daily]], Feb. 28, 2013.</ref><ref>[http://www.abc.net.au/news/2013-09-20/scientists-speak-out-against-vandalism-of-gm-rice/4970626 Scientists speak out against vandalism of genetically modified rice], [[Australian Broadcasting Corporation]], Fri 20 Sep 2013.</ref><ref>[http://www.salon.com/2013/09/30/vandals_hack_down_hawaiis_genetically_modified_papaya_trees/ Vandals hack down Hawaii’s genetically modified papaya trees: The destruction is believed to have been the work of anti-GMO activists], LINDSAY ABRAMS, Salon, SEP 30, 2013. Citation: "Papaya vandals strike again".</ref><ref>[http://www.geneticliteracyproject.org/2013/06/25/oregon-genetically-modified-crops-vandalized Oregon: Genetically modified crops vandalized], Karl Haro von Mogel, Genetic Literacy Project, June 25, 2013.</ref> Within the UK and other European countries, 80 crop trials by academic or governmental research institutes have been destroyed by protesters.<ref name=kuntz>{{cite journal |doi=10.4161/gmcr.21231 |title=Destruction of public and governmental experiments of GMO in Europe |year=2012 |last1=Kuntz |first1=Marcel |journal=GM crops & food |volume=3 |issue=4 |pages=258}}</ref> In some cases, threats and violence against people or property were also carried out.<ref name=kuntz/> In 1999, anti-GMO-activists burned the biotech lab of [[Michigan State University]], destroying the results of years of work and property worth $400,000.<ref name=why>[http://reason.com/archives/2001/01/01/dr-strangelunch Dr. Strangelunch Or: Why we should learn to stop worrying and love genetically modified food], [[The Reason]], Ronald Bailey, January 2001.</ref> |

|||

In 1983, environmental groups and protesters delayed the field tests of the genetically modified [[Ice-minus bacteria|ice-minus strain of ''P. syringae'']] with legal challenges.<ref>{{cite journal |first=Rebecca |last=Bratspies | name-list-style = vanc |year=2007 |title=Some Thoughts on the American Approach to Regulating Genetically Modified Organisms |journal=Kansas Journal of Law and Public Policy |volume=16 |pages=393 |ssrn=1017832}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |author=United States Court of Appeals, District of Columbia Circuit. |title=Foundation on Economic Trends v. Heckler |work=756 F.2d 143 |date=1985 |url=https://law.resource.org/pub/us/case/reporter/F2/756/756.F2d.143.84-5419.84-5314.html}}</ref> |

|||

===''Alliance for Bio-Integrity v. Shalala''=== |

|||

In 1983, environmental groups and protestors delayed the field tests of the genetically modified [[Ice-minus bacteria|ice-minus strain of ''P. syringae'']] with legal challenges.<ref>Rebecca Bratspies (2007) Some Thoughts on the American Approach to Regulating Genetically Modified Organisms. Kansas Journal of Law and Public Policy 16:393 [http://nationalaglawcenter.org/assets/bibarticles/bratspies_some.pdf]</ref> In 1987, the ice-minus strain of ''P. syringae'' became the first [[genetically modified organism|genetically modified organism (GMO)]] to be released into the environment<ref name=BBC2002>BBC News 14 June 2002 [http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/2045286.stm GM crops: A bitter harvest?]</ref> when a strawberry field in California was sprayed with the bacteria. This was followed by the spraying of a crop of potato seedlings.<ref>Thomas H. Maugh II for the Los Angeles Times. 9 June 1987. [http://articles.latimes.com/1987-06-09/news/mn-6024_1_frost-damage Altered Bacterium Does Its Job : Frost Failed to Damage Sprayed Test Crop, Company Says]</ref> The plants in both test fields were uprooted by activist groups the night before the tests occurred, but were re-planted the next day in time for the testing.<ref name=BBC2002 /> |

|||