Taiwan Strait: Difference between revisions

Jaredscribe (talk | contribs) →top: Cross-strait relations between the ROC Taiwan and the People's Republic of China are not on terms of peace, as the two nations do not formally recognize each other. |

No edit summary Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

| basin_countries = |

| basin_countries = |

||

{{PRC}}<br> |

{{PRC}}<br> |

||

{{ROC}} |

|||

Taiwan |

|||

| length = |

| length = |

||

| min_width = {{convert|130|km|mi|abbr=on|sp=us}} |

| min_width = {{convert|130|km|mi|abbr=on|sp=us}} |

||

Revision as of 20:41, 10 August 2022

| Taiwan Strait | |

|---|---|

A map showing the Taiwan Strait Area | |

| Location | South China Sea, East China Sea (Pacific Ocean) |

| Coordinates | 24°48′40″N 119°55′42″E / 24.81111°N 119.92833°E |

| Basin countries | |

| Min. width | 130 km (81 mi) |

| Taiwan Strait | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 臺灣海峽 台灣海峽 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 台湾海峡 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hokkien POJ | Tâi-ôan Hái-kiap | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Taihai | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 臺海 台海 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 台海 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hokkien POJ | Tâi-hái | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Taiwan Sea | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Black Ditch | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 烏水溝 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 乌水沟 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hokkien POJ | O͘ Chúi-kau | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Black Ditch | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Taiwan Strait is a 180-kilometer (110 mi; 97 nmi)-wide strait separating the island of Taiwan and continental Asia. The strait is part of the South China Sea and connects to the East China Sea to the north. The narrowest part is 130 km (81 mi; 70 nmi) wide.[1] Cross-strait relations between the ROC Taiwan and the People's Republic of China are not on terms of peace, as the two nations do not formally recognize each other.

Names

Former names of the Taiwan Strait include the Formosa Strait or Strait of Formosa, from a dated name for Taiwan; the Strait of Fokien or Fujian, from the Chinese province forming the strait's western shore;[2] and the Black Ditch, a calque of the strait's name in Hokkien and Hakka.

Geography

The Taiwan Strait is the body of water separating Fujian Province from Taiwan Island. International agreement does not define the Taiwan Strait but places its waters within the South China Sea, whose northern limit runs from Cape Fugui (the northernmost point on Taiwan Island; Fukikaku) to Niushan Island to the southernmost point of Pingtan Island and thence westward along the parallel 25° 24′ N. to the coast of Fujian Province.[3] The draft for a new edition of the IHO's Limits of Oceans and Seas does precisely define the Taiwan Strait, classifying it as part of the North Pacific Ocean.[4] It makes the Taiwan Strait a body of water between the East and South China Seas and delimits it:[5]

On the North: A line joining the coast of China (25° 42′ N - 119° 36′ E) eastward to Xiang Cape (25° 40′ N - 119° 47′ 10″ E), the northern extremity of Haitan Island, and thence to Fugui Cape (25° 17′ 45″ N - 121° 32′ 30″ E), the northern extremity of Taiwan Island (the common limit with the East China Sea, see 7.3).

On the East: From Fugui Cape southward, along the western coast of Taiwan Island, to Eluan Cape (21° 53′ 45″ N - 120° 51′ 30″ E), the southern extremity of this island.

On the South: A line joining Eluan Cape northwestward, along the southern banks of Nanao Island, to the southeastern extremity of this island (23° 23′ 35″ N - 117° 07′ 15″ E); thence westward, along the southern coast of Nanao Island, to Changshan Head (23° 25′ 50″ N - 116° 56′ 25″ E), the western extremity of this island; and thence a line joining Changshan Head westward to the mouth of the Hanjiang River (23° 27′ 30″ N - 116° 52′ E), on the coast of China (the common limit with the South China Sea, see 6.1).

On the West: From the mouth of Hanjiang River northeastward, along the coast of China, to position 25° 42′ N - 119° 36′ E.

The entire strait is on Asia's continental shelf. It is almost entirely less than 150 m (490 ft; 82 fathoms) deep, with a short ravine of that depth off the south-west coast of Taiwan. As such, there are many islands in the strait. The largest and most important islands off the Fujianese coast are Xiamen, Gulangyu, Pingtan (the "Haitan" of the IHO delineation), Kinmen, and Matsu. The first three are controlled by the People's Republic of China (PRC); the last two by the Republic Of China (ROC). Within the strait lie the Penghu or the Pescadores, also controlled by the ROC. There is a major underwater bank 40–60 km (25–37 mi) north of the Penghu Islands.[6]

All of Fujian Province's rivers except the Ting run into the Taiwan Strait. The largest two are the Min and the Jiulong.[citation needed]

Median line

Historically both the People's Republic of China (PRC) and the Republic of China (ROC) on Taiwan espoused a One-China Policy that considered the strait part of the exclusive economic zone of a single "China".[7] In practice, a maritime border of control exists along the median line down the strait.[8] The median line was defined in 1955 by US Air Force General Benjamin O. Davis Jr. who drew a line down the middle of the strait, the US then pressured both sides into entering into a tacit agreement not to cross the median line. The PRC did not cross the median line until 1999, however following the first encroachment in 1999 Chinese aircraft have encroached over the median line with increasing regularity.[9] The median line is also known as the Davis line.[10]

Geology

Sediment distribution

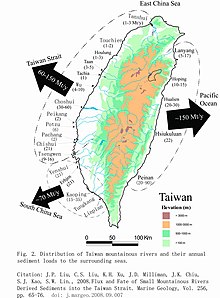

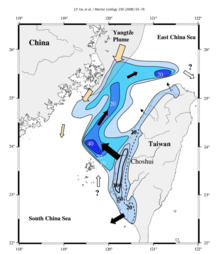

Each year, Taiwan's rivers carry up to 370 million tons of sediments into the sea, including 60 to 150 million tons deposited into the Taiwan Strait.[11] During the past ten thousand years, 600 billion tons of riverine sediments have been deposited in the Taiwan Strait, locally forming a lobe up to 40 m thick in the southern part of the Taiwan Strait.[11]

History

The Strait mostly separated the Han culture of the Chinese mainland from Taiwan Island's aborigines for millennia, although the Hakka and Hoklo traded and migrated across it. European explorers, principally the Spanish and Dutch, also took advantage of the strait to establish forward bases for trade with the mainland during the Ming; the bases were also used for raiding both the Chinese coast and the trading ships of rival countries.[citation needed]

Widespread Chinese migration across the strait began in the late Ming. During the Qing conquest, Zheng Chenggong (Koxinga) expelled the Dutch and established the Kingdom of Tungning in 1661, planning to launch a reconquest of the mainland in the name of the Southern Ming branches of the old imperial dynasty. Dorgon and the Kangxi Emperor were able to consolidate their control over southern mainland China; Koxinga found himself limited to raiding across the strait. His grandson Zheng Keshuang surrendered to the Qing after his admiral lost the 1683 Battle of the Penghu Islands in the middle of the strait.[citation needed]

Japan seized the Penghu Islands during the First Sino-Japanese War and gained control of Taiwan at its conclusion in 1895. Control of the eastern half of the strait was used to establish control of the southern Chinese coast during the Second World War. The strait protected Japanese bases and industry on Taiwan from Chinese attack and sabotage, but aerial warfare reached the island by 1943. The 1944 Formosa Air Battle gave the United States Pacific Fleet air supremacy from its carrier groups and Philippine bases; subsequently, bombing was continuous until Japan's surrender in 1945.[citation needed] The rapid advance of the Communist PLA in 1949 provoked the government's retreat across the Taiwan Strait. On 26 February 2022, China denounced the sailing of the U.S. Navy's 7th Fleet Arleigh Burke-class guided-missile destroyer USS Ralph Johnson through the Taiwan Strait as a 'provocative act'."[12]

Economy

Fishermen have used the strait as a fishing resource since time immemorial. In the modern world, it is the gateway used by ships of almost every kind on passage to and from nearly all the important ports in Northeast Asia.[13] In 2020 Chinese vessels had been illegally fishing and dredging sand on the Taiwanese half of the strait.[14]

Taiwan is building major wind farms in the strait.[15]

Gallery

-

Looking south from the East to South China Sea

-

Looking north from the South to East China Sea

See also

Taiwan Strait.

References

Citations

- ^ "Geography". Government Information Office. Archived from the original on 29 December 2010. Retrieved 23 January 2011.

- ^ EB (1879), p. 415.

- ^ IHO (1953), §49.

- ^ IHO (1986), Ch. 7.

- ^ IHO (1986), Ch. 7.2.

- ^ Sea depth map.

- ^ Trent, Mercedes (2020). "Over the Line: The Implications of China's ADIZ Intrusions in Northeast Asia" (PDF). Federation of American Scientists. p. 22. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- ^ 大公報文章:"海峽中線"應該廢除, chinareviewnews.com. (in Chinese)

- ^ Tai-ho, Lin. "Air defense must be free of political calculation". www.taipeitimes.com. Taipei Times. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ^ Micallef, Joseph V. (6 January 2021). "Why Taiwan Will Be at the Center of the China-US Rivalry". www.military.com. Military.com. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- ^ a b Liu, J. P.; Liu, C. S.; Xu, K. H.; Milliman, J. D.; Chiu, J. K.; Kao, S. J.; Lin, S. W. (20 December 2008). "Flux and fate of small mountainous rivers derived sediments into the Taiwan Strait". Marine Geology. 256 (1): 65–76. Bibcode:2008MGeol.256...65L. doi:10.1016/j.margeo.2008.09.007. ISSN 0025-3227.

- ^ China says U.S. warship sailing in Taiwan Strait 'provocative'. Reuters. 26 February 2022. Accessed 26 February 2022. Archive.

- ^ Chen, Jinhai; Lu, Feng; Li, Mingxiao; Huang, Pengfei; Liu, Xiliang; Mei, Qiang (2016), Tan, Ying; Shi, Yuhui (eds.), "Optimization on Arrangement of Precaution Areas Serving for Ships' Routeing in the Taiwan Strait Based on Massive AIS Data", Data Mining and Big Data, vol. 9714, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 123–133, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-40973-3_12, ISBN 978-3-319-40972-6, retrieved 20 November 2021

- ^ Hsin-po, Huang; Xie, Dennis (9 November 2020). "Coast guard should benefit from fines on intruders: lawmakers". www.taipeitimes.com. Taipei Times. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- ^ "Greater Changhua Offshore Wind Farms". www.power-technology.com. Power Technology. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

Bibliography

- , Encyclopaedia Britannica, 9th ed., Vol. IX, New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1879, pp. 415–17.

- S-23: Limits of Oceans and Seas (PDF) (3rd ed.), Monaco: International Hydrographic Organization, 1953.

- S-23: Limits of Oceans and Seas (4th (draft) ed.), Monaco: International Hydrographic Organization, 1986.