Liberia: Difference between revisions

Timbobutcher (talk | contribs) updating with new Liberian book |

|||

| Line 391: | Line 391: | ||

== Further reading == |

== Further reading == |

||

* ''[[Chasing the Devil]]'' by Tim Butcher. An account of a 350 mile trek through Liberia undertaken in 2009 along the route used in 1935 by Graham and Barbara Greene. Published in 2010 by Chatto & Windus ISBN 978 – 070 - 1183608 |

|||

* ''[[Journey Without Maps]]'' by Graham Greene. An account of a four-week walk through the interior of Liberia in 1935. Reprinted in 2006 by Vintage ISBN 978-0-09-928223-5 |

* ''[[Journey Without Maps]]'' by Graham Greene. An account of a four-week walk through the interior of Liberia in 1935. Reprinted in 2006 by Vintage ISBN 978-0-09-928223-5 |

||

* ''Too Late to Turn Back'' by Barbara Greene. Account by a cousin of Graham Greene of the above-mentioned 1935 journey, on which she was also a participant. |

* ''Too Late to Turn Back'' by Barbara Greene. Account by a cousin of Graham Greene of the above-mentioned 1935 journey, on which she was also a participant. |

||

Revision as of 13:26, 2 March 2011

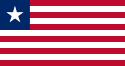

Republic of Liberia | |

|---|---|

| Motto: The love of liberty brought us here | |

| Anthem: "All Hail, Liberia, Hail!" | |

| |

| Capital and largest city | Monrovia |

| Official languages | English |

| Demonym(s) | Liberian |

| Government | Presidential republic |

| Ellen Johnson Sirleaf | |

| Joseph Boakai | |

| Johnnie Lewis | |

| Legislature | Legislature of Liberia |

| Senate | |

| House of Representatives | |

| Formation | |

• Established by the American Colonization Society | 1822 |

| 26 July 1847 | |

| 6 January 1986 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 111,369 km2 (43,000 sq mi) (103rd) |

• Water (%) | 13.514 |

| Population | |

• 2009 estimate | 3,955,000[1] |

• 2008 census | 3,476,608 (130th) |

• Density | 35.5/km2 (91.9/sq mi) (180th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2009 estimate |

• Total | $1.556 billion[2] |

• Per capita | $424[2] |

| GDP (nominal) | 2009 estimate |

• Total | $876 million[2] |

• Per capita | $239[2] |

| HDI (2007) | 0.442 low (169th) |

| Currency | Liberian dollar1 (LRD) |

| Time zone | GMT |

• Summer (DST) | not observed |

| Drives on | right |

| Calling code | 231 |

| ISO 3166 code | LR |

| Internet TLD | .lr |

1 United States dollar also in common usage. | |

Liberia (/[invalid input: 'En-us-Liberia.ogg']laɪˈbɪəriə/), officially the Republic of Liberia, is a country on the west coast of Africa, bordered by Sierra Leone on the West, Guinea on the north, Côte d'Ivoire on the east, and the Atlantic Ocean on the south. As of the 2008 Census, the nation is home to 3,476,608 people. [3] Its area is 111,369 km2 (43,000 sq mi) [4].

Liberia's capital is Monrovia. Liberia has a hot equatorial climate with most rainfall arriving in the rainy season with harsh harmattan winds in the dry season. Liberia's populated Pepper Coast is composed of mostly mangrove forests while the sparsely populated inland is forested, later opening to a plateau of drier grasslands.

The history of Liberia is unique among African nations because of its relationship with the United States. It is one of only two countries in sub-Sahara Africa, along with Ethiopia, without roots in the European Scramble for Africa. It was founded and colonized by freed American slaves with the help of a private organization called the American Colonization Society in 1821-1822, on the premise that former American slaves would have greater freedom and equality there.[5]

Slaves freed from slave ships were also sent there instead of being repatriated to their countries of origin.[6] These colonists formed an elite group in Liberian society, and, in 1847, they founded the Republic of Liberia, establishing a government modeled on that of the United States, naming Monrovia, their capital city, after James Monroe, the fifth president of the United States and a prominent supporter of the colonization.

A military-led coup in 1980 overthrew then-president William R. Tolbert, which marked the beginning of a period of instability that eventually led to two civil wars that left hundreds of thousands of people dead and devastated the country's economy. Today, Liberia is recovering from the lingering effects of the civil war and related economic dislocation. Statistics indicate that about 85% of the population live on less than $1.25 a day.

Etymology

The name Liberia denotes "liberty". The newly arrived settlers formed a new ethnic group called the Americo-Liberians.[7] However, this introduction of a new ethnic mix resulted in ethnic tensions with the sixteen other main ethnicities already residing in Liberia.[8] From the 16th century until 1822, European explorers and traders had multiple names for Liberia, varying by language.

During the spice trade, in non-English speaking Europe, Liberia was called the Malaguetta Coast or Pepper Coast in English. It earned its name from the melegueta pepper found in rural Liberia that was dubbed the "Grains of paradise" since it was a rare spice in high demand throughout continental Europe. In late 18th century English explorers referred to the country as the Windward Coast because of notoriously unnavigable, choppy waters off the coast of Cape Palmas at the tip of Southern Liberia that were difficult for European ships to sail through.[9]

History

Indigenous tribes 1200-1800

Anthropological and archeological research shows the region of Liberia was inhabited at least as far back as the 12th century, perhaps earlier. Mende-speaking people expanded westward, forcing many smaller ethnic groups southward towards the Atlantic ocean. The Days, Bassa, Kru, Gola and Kissi were some of the earliest recorded arrivals.[10] This influx was compounded during the ancient decline of the Western Sudanic Mali Empire in 1375 and later in 1591 with the Songhai Empire. Additionally, inland regions underwent desertification, and inhabitants were pressured to move to the wetter Pepper Coast. These new inhabitants brought skills such as cotton spinning, cloth weaving, iron smelting, rice and sorghum cultivation, and social and political institutions from the Mali and Songhai Empires.[11]

Shortly after the Manes conquered the region, there was a migration of the Vai people into the region of Grand Cape Mount. The Vai were part of the Mali Empire who were forced to migrate when the empire collapsed in the 14th century. The Vai chose to migrate to the coastal region. The ethnic Kru opposed the influx of Vai. An alliance of the Manes and Kru was able to stop further influx of Vai, but the Vai remained in the Grand Cape Mount region (where the city of Robertsport is now located).

People of the Littoral coast built canoes and traded with other West Africans from Cap-Vert to the Gold Coast. Later European traders would barter various commodities and goods with local people, sometimes hoisting their canoes aboard. When the Kru began trading with Europeans, they initially traded in commodities, but later they actively participated in the African slave trade.

Kru laborers left their territory to work as paid laborers on plantations and in construction. Some even worked building the Suez and Panama canals.

Another ethnic group in the area was the Glebo. The Glebo were driven, as a result of the Manes invasion, to migrate to the coast of what later became Liberia.

Between 1461 and late 17th century, Portuguese, Dutch and British traders had contacts and trading posts in what became Liberia. The Portuguese had named the area Costa da Pimenta (meaning Pepper Coast), later translated as Grain Coast, because of the abundance of grains of melegueta pepper.

Settlers from the United States

In 1822, the American Colonization Society (A.C.S.), working to "repatriate" black Americans to greater freedom in Africa, established Liberia[12] as a place to send people who were formerly enslaved.[5][13] This movement of black people by the A.C.S. had broad support nationwide among white people in the United States, including politicians such as Henry Clay and James Monroe. They believed this was preferable to emancipation of slaves in the United States. Clay said, because of "unconquerable prejudice resulting from their color, they never could amalgamate with the free whites of this country. It was desirable, therefore, as it respected them, and the residue of the population of the country, to drain them off."[14] The institution of slavery in the U.S. had grown, reaching almost four million slaves by the mid 19th century.[15] Some free African Americans chose to emigrate to Liberia.[16] The immigrants became known as Americo-Liberians, and about 5% of present-day Liberians trace their ancestry to them. On July 26, 1847, Americo-Liberian settlers declared the independence of the Republic of Liberia.[17][18]

The settlers regarded Africa as a "promised land". However, they did not choose to integrate into African society. They still referred to themselves as Americans, and were recognized as such by local Africans and by British colonial authorities in neighboring Sierra Leone. The symbols of their nation — its flag, motto, and seal, and the form of government that they chose -- all reflected their American background and diaspora experience. Ashmun Institute, founded in Pennsylvania in 1854 for the education of black Americans, played an important role in supplying Americo-Liberians with leadership for the new nation. The first graduating class of Ashmun Institute (later renamed Lincoln University in honor of the slain president), consisting of James R. Amos, his brother Thomas H. Amos, and Armistead Miller, sailed for Liberia shortly after graduation on the brig Mary C. Stevens in April 1859.

The religious practices, social customs and cultural standards of the Americo-Liberians had their roots in the antebellum American South. These ideals strongly influenced the attitudes of the settlers toward the indigenous African people. The new nation, as they perceived it, was coextensive with the settler community and with those Africans who were assimilated into it. Mutual mistrust and hostility between the "Americans" along the coast and the "Natives" of the interior was a recurrent theme in the country's history. The Americo-Liberian minority worked to dominate the native people, whom they considered savage primitives. The immigrants named the country "Liberia", which in Latin means "Land of the Free", as an homage to their freedom from slavery.

Historically, Liberia has enjoyed the support and unofficial cooperation of the United States government.[19] Liberia's government, modeled after that of the U.S., was democratic in structure, if not always in substance. In 1877, the True Whig Party monopolized political power in the country. Competition for office was usually contained within the party, whose nomination virtually ensured election. Two problems confronting successive administrations were pressure from neighboring colonial powers, Britain and France, and the threat of financial insolvency, both of which challenged the country's sovereignty. Liberia retained its independence during the Scramble for Africa, but lost its claim to extensive territories that were annexed by Britain and France. Economic development was hindered by the decline of markets for Liberian goods in the late 19th century and by indebtedness on a series of loans, payments on which drained the economy.

Mid-20th century

Two events were particularly important in releasing Liberia from its self-imposed isolation. The first was the grant in 1926 of a large concession to the American-owned Firestone Plantation Company, which became a first step in the (limited) modernization of the Liberian economy. The second occurred during World War II, when the United States began providing technical and economic assistance that enabled Liberia to make economic progress and introduce social change. Both the Freeport of Monrovia and Roberts International Airport were built by U.S. personnel during World War II.

On April 12, 1980, a successful military coup was staged by a group of non-commissioned army officers led by Master Sergeant Samuel Kanyon Doe. The soldiers were a mixture of the various ethnic groups that claimed marginalization at the hands of the minority Americo-Liberian settlers. In a late-night raid on the Executive Mansion in Monrovia, they killed William R. Tolbert, Jr., who had been president for nine years, and later executed a majority of his cabinet. Constituting themselves as the People's Redemption Council, Doe and his associates seized control of the government and brought an end to Africa's first republic. Significantly, Doe was the first Liberian head of state who was not a member of the Americo-Liberian elite.

In October 1985, Liberia held the first post-coup elections, ostensibly to legitimize Doe's regime. Virtually all[who?] international observers agreed that the Liberia Action Party (LAP) led by Jackson Doe (no relation) had won the election by a clear margin. After a week of counting the votes, however, Samuel Doe fired the count officials and replaced them with his own Special Election Committee (SECOM), which announced that Samuel Doe's ruling National Democratic Party of Liberia had won with 50.9% of the vote. In response, on November 12 a counter-coup was launched by Thomas Quiwonkpa, whose soldiers briefly occupied the Executive Mansion and the national radio station, with widespread support throughout the country. Three days later, Quiwonkpa's coup was overthrown. Government repression intensified, as Doe's troops killed more than 2,000 civilians and imprisoned more than 100 opposing politicians, including Jackson Doe and BBC journalist Isaac Bantu.

1989 and 1999 civil wars

In late 1989, the First Liberian Civil War began. The harsh dictatorial atmosphere that gripped the country was due largely to Samuel Doe's rule. Americo-Liberian Charles Taylor, with the backing of neighboring countries such as Burkina Faso and Côte d'Ivoire, entered Nimba County with around 100 men.[20] These fighters quickly gained control of much of the country, thanks to strong support from the local population who were disillusioned with the Doe government. By then, a new player also emerged: Prince Yormie Johnson (former ally of Taylor) had formed his own army and had gained tremendous support from the Gio and Mano ethnic groups.

In August 1990, the Economic Community Monitoring Group under the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) organized its own military task force to intervene in the crisis. The troops were largely from Nigeria, Guinea and Ghana. On his way out after a meeting, Doe, who was traveling only with his personal staff, was ambushed and captured by members of the Gio Tribe who were loyal to Johnson. The soldiers took him to Johnson's headquarters in neighboring Caldwell, tortured and killed him.

By then, Taylor was a prominent warlord and leader of the National Patriotic Front of Liberia. After some prompting from Taylor that the anglophone Nigerians and Ghanaians were opposed to him, Senegalese troops were brought in with some financial support from the United States.[21] But their service was short-lived, after a major confrontation with Taylor's forces in Vahun, Lofa County on 28 May 1992, when six were killed when a crowd of NPFL supporters surrounded their vehicle and demanded they surrender the vehicle and weapons.[22]

By September 1990, Doe's forces controlled only a small area just outside the capital, Monrovia. After Doe's death, and as a condition for the end of the conflict, interim president Amos Sawyer resigned in 1994, handing power to the Council of State. Taylor was elected as President in 1997, after leading a bloody insurgency backed by Libyan President Muammar al-Gaddafi. Taylor's brutal regime targeted several leading opposition and political activists. In 1998, the government sought to assassinate child rights activist Kimmie Weeks for a report he had published on its involvement in the training of child soldiers, which forced him into exile. Taylor's autocratic and dysfunctional government led to the Second Liberian Civil War in 1999.

The conflict intensified in mid-2003, and the fighting moved into Monrovia. An elite rapid response unit of the U.S. Marines, known as 'FAST', were deployed in Monrovia to ensure the security and interests of the U.S. Embassy there. The Marines used U.S. Air Force HH-60 Pave Hawk to airlift non-combatants and foreign nationals to Dakar, Senegal. A hastily assembled force of 1,000 Nigerian troops, the ECOWAS Mission In Liberia (ECOMIL), was airlifted into Liberia on August 15, 2003 to prevent the rebels from overrunning the capital city and committing revenge-inspired war crimes. Meanwhile the U.S. Joint Task Force Liberia commanded from USS Iwo Jima was offshore, though only 100 of the 2,000 U.S. Marines landed to meet with the ECOMIL force.

A peace movement called Women of Liberia Mass Action for Peace was instrumental to the end of hostilities in Monrovia. Organized by social worker Leymah Gbowee, thousands of Christian and Muslim women staged silent protests and forced a meeting with President Charles Taylor and extracted a promise from him to attend peace talks in Ghana. Gbowee then led a delegation of Liberian women to Ghana to continue to apply pressure on the warring factions during the peace process.[23] They staged a sit in outside of the Presidential Palace, blocking all the doors and windows and preventing anyone from leaving the peace talks without a resolution. The women of Liberia became a political force against violence and against their government.[24] Their actions brought about an agreement during the stalled peace talks. As a result, the women were able to achieve peace in Liberia after a 14-year civil war and later helped bring to power the country's first female head of state. The story is told in the 2008 documentary film Pray the Devil Back to Hell.[25]

As the power of the government shrank, and with increasing international and U.S. pressure for him to resign, President Taylor accepted an asylum offer from Nigeria, but vowed: "God willing, I will be back." Some of the ECOMIL troops were subsequently withdrawn and at least two battalions incorporated into the 15,000 strong United Nations Mission in Liberia (UNMIL) peacekeeping force. More than 200,000 people are estimated to have been killed in the civil wars.

Post-civil war period

After the exile of Taylor, Gyude Bryant was appointed chairman of the transitional government in late 2003. Because of failures of the Transitional Government in curbing corruption, Liberia signed onto GEMAP, a novel anti-corruption program. The primary task of the transitional government was to prepare for fair and peaceful democratic elections.

With UNMIL troops safeguarding the peace, Liberia successfully conducted presidential and legislative elections on October 11, 2005. There were 23 candidates; an early favorite was George Weah, an internationally famous footballer, UNICEF goodwill ambassador, and member of the Kru ethnic group expected to dominate the popular vote. Though Weah garnered a plurality of the votes, no candidate gained the required majority, prompting a runoff election between the top two candidates, Weah and Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, a Harvard-trained economist and former minister of finance who had been jailed twice during the Doe administration before escaping and going into exile. The November 8, 2005, presidential runoff election was won decisively by Sirleaf. Both the general election and runoff were marked by peace and order, as thousands of Liberians waited in the harsh West African heat to cast their ballots.

Upon taking office, Sirleaf became the first elected female head of state in Africa. During her administration President Sirleaf established the Truth and Reconciliation Commission to address crimes committed during the later stages of Liberia's long civil war.[26] Sirleaf also requested the extradition of Taylor from Nigeria and immediately handed him over to the Special Court for Sierra Leone, which had charged Taylor with crimes against humanity, violations of the Geneva Conventions and "other serious violations of international humanitarian law."[27] The trial by the Special Court is being held in The Hague for security reasons.

Politics and government

Liberia has a dual system of statutory law based on Anglo-American common law for the modern sector and customary unwritten law for the native sector for exclusively rural ethnic communities.[28][29] Liberia's modern sector has three equal branches of government in the constitution, though in practice the executive branch headed by the President of Liberia is the strongest of the three. The other two branches are the Legislature of Liberia and Supreme Court of Liberia.

Following the dissolution of the Republican Party in 1876, the True Whig Party dominated the Liberian government until the 1980 coup. Currently, no party has majority control of the legislature. The longest serving president in Liberian history was William Tubman, serving from 1944 until his death in 1971. The shortest term was held by James Skivring Smith, who controlled the government for two months. However, the political process from Liberia's founding in 1847, despite widespread corruption, was very stable until the end of the First Republic in 1980.

The executive branch of the government is headed by the president.[29] Other parts of the branch are the cabinet and the vice president. Presidents are elected to six-year terms and can serve up to two terms in office.[29] The president is both the head of state and the head of the government, and resides at the Executive Mansion in Monrovia.[29]

The legislature of Liberia is a bicameral body with an upper chamber Senate and the lower chamber House of Representatives. Each county sends two senators to the legislature for a total of 30 senators, while the 64 seats in the House are distributed among the 15 counties on the basis of the number of registered voters, with a minimum of at least two from each county.[29] Senators serve nine-year terms (only six-year terms for junior senators elected in 2005) and members of the House six-year terms.[29] Leadership consists of a speaker in the House and a president pro tempore in the Senate. Liberia's vice president serves as the president of the Senate. The legislature meets in the capital city of Monrovia.

Liberia's highest judicial authority is the Supreme Court, headed by the chief justice. The five-justice court holds sessions at the Temple of Justice on Capitol Hill in Monrovia. Members are nominated to the court by the president and are confirmed by the Senate and have lifetime tenure. Under the supreme court are 15 circuit courts, one in each county.

Liberia's former minister of justice has been at the center of a legal scandal for what amounts to de facto withholding the Liberian law, preventing it from being reprinted and circulated.[30]

Human rights

Amnesty International summarizes in its Annual Report 2006:

- "Sporadic outbreaks of violence continued to threaten prospects of peace. Former rebel fighters who should have been disarmed and demobilized protested violently when they did not receive benefits. Slow progress in reforming the police, judiciary and the criminal justice system resulted in systematic violations of due process and vigilante violence against criminal suspects. Laws establishing an Independent National Commission on Human Rights and a Truth and Reconciliation Commission were adopted. Over 200,000 internally displaced people and refugees returned to their homes, although disputes over land and property appropriated during the war raised ethnic tensions. U.N. sanctions on the trade in diamonds and timber were renewed. Those responsible for human rights abuses during the armed conflict continued to enjoy impunity. The UN Security Council gave peacekeeping forces in Liberia powers to arrest former President Taylor and transfer him to the Special Court for Sierra Leone if he should return from Nigeria, where he continued to receive asylum. Liberia made a commitment to abolish capital punishment. A new law on rape, which initially proposed imposition of the death penalty for gang rape, was amended to provide a maximum penalty of life imprisonment."[31]

Former 22nd president Charles Taylor was later captured trying to escape across the border of Cameroon and has been sent to the International Criminal Court in The Hague for trial.

In 2009, the country set up a new court to deal with rape crimes in and around Monrovia, called "Court E." The court operates in camera, shielding the victims who testify from exposure to the accused perpetrator and the rest of the courtroom. The prosecutor operates out of the Sexual and Gender Based Violence Crimes office, which offers victims' support services, but faces many financial, logistical and legal hurdles.

Organized by Leymah Gbowee and Comfort Freeman, Women of Liberia Mass Action for Peace is a peace movement that brought an end to the Second Liberian Civil War in 2003 and led to the election of Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, the first African nation with a female president.

Geography

Liberia is situated in West Africa, bordering the North Atlantic Ocean to the country's southwest. It lies between latitudes 4° and 9°N, and longitudes 7° and 12°W.

The landscape is characterized by mostly flat to rolling coastal plains that contain mangroves and swamps, which rise to a rolling plateau and low mountains in the northeast.[13] Tropical rainforests cover the hills, while elephant grass and semi-deciduous forests make up the dominant vegetation in the northern sections.[13] The equatorial climate is hot year-round with heavy rainfall from May to October with a short interlude in mid-July to August.[13] During the winter months of November to March, dry dust-laden harmattan winds blow inland, causing many problems for residents.[13]

Liberia's watershed tends to move in a southwestern pattern towards the sea as new rains move down the forested plateau off the inland mountain range of Guinée Forestière, in Guinea. Cape Mount near the border with Sierra Leone receives the most precipitation in the nation.[13] The country's main northwestern boundary is traversed by the Mano River while its southeast limits are bounded by the Cavalla River.[13] Liberia's three largest rivers are St. Paul exiting near Monrovia, the river St. John at Buchanan and the Cestos River, all of which flow into the Atlantic. The Cavalla is the longest river in the nation at 320 miles (515 km).[13]

The highest point wholly within Liberia is Mount Wuteve at 4,724 feet (1,440 m) above sea level in the northwestern Liberia range of the West Africa Mountains and the Guinea Highlands.[13] However, Mount Nimba near Yekepa, is higher at 5,748 feet (1,752 m) above sea level but is not wholly within Liberia as Nimba shares a border with Guinea and Côte d'Ivoire (Ivory Coast) and is their tallest mountain as well.[32]

Counties and districts

Liberia is divided into 15 counties, which are subdivided into districts, and further subdivided into clans. The oldest counties are Grand Bassa and Montserrado, both founded in 1839 prior to Liberian independence. Gbarpolu is the newest county, created in 2001. Nimba is the largest of the counties in size at 4,460 square miles (11,551 km2), while Montserrado is the smallest at 737 square miles (1,909 km2).[33] Montserrado is also the most populous county with 1,144,806 residents as of the 2008 census.[33]

Complete list of the counties:

| County | Capital | Population (2008)[33] | Area[33] | Created |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bomi | Tubmanburg | 82,036 | 750 sq mi (1,942 km2) | 1984 |

| Bong | Gbarnga | 328,919 | 3,387 sq mi (8,772 km2) | 1964 |

| Gbarpolu | Bopulu | 83,758 | 3,741 sq mi (9,689 km2) | 2001 |

| Grand Bassa | Buchanan | 224,839 | 3,064 sq mi (7,936 km2) | 1839 |

| Grand Cape Mount | Robertsport | 129,055 | 1,993 sq mi (5,162 km2) | 1844 |

| Grand Gedeh | Zwedru | 126,146 | 4,048 sq mi (10,484 km2) | 1964 |

| Grand Kru | Barclayville | 57,106 | 1,504 sq mi (3,895 km2) | 1984 |

| Lofa | Voinjama | 270,114 | 3,854 sq mi (9,982 km2) | 1964 |

| Margibi | Kakata | 199,689 | 1,010 sq mi (2,616 km2) | 1985 |

| Maryland | Harper | 136,404 | 887 sq mi (2,297 km2) | 1857 |

| Montserrado | Bensonville | 1,144,806 | 737 sq mi (1,909 km2) | 1839 |

| Nimba | Sanniquellie | 468,088 | 4,460 sq mi (11,551 km2) | 1964 |

| River Cess | River Cess | 65,862 | 2,160 sq mi (5,594 km2) | 1985 |

| River Gee | Fish Town | 67,318 | 1,974 sq mi (5,113 km2) | 2000 |

| Sinoe | Greenville | 104,932 | 3,914 sq mi (10,137 km2) | 1843 |

Economy

Liberia is one of the world's poorest countries, with a formal employment rate of only 15%.[34] Historically, the Liberian economy depended heavily on iron ore and rubber exports, foreign direct investment, and exports of other natural resources, such as timber.[13] Agricultural products include livestock (goats, pigs, cattle) and rice, the staple food.[13] Fish are raised on inland farms and caught along the coast.[13] Other foods are imported to support the population.[13] Electricity is provided by dams and oil-fired plants.[13]

While official export figures for commodities declined during the 1990s’ civil war as many investors fled, Liberia's wartime economy featured the exploitation of the region's diamond wealth.[citation needed] The country acted as a major trader in Liberian, Sierra Leonian and Angolan blood diamonds, exporting over $300 million in diamonds annually. This led to a United Nations ban on Liberian diamond exports, which was lifted on April 27, 2007.

Other commodity exports continued during the war, in part due to illicit agreements between Liberia's warlords and foreign concessionaires. Looting and war profiteering destroyed nearly the entire infrastructure of the country, such that the Monrovian capital was without running water and electricity (except for fuel-powered generators) by the time the first elected post-war government began to institute development and reforms in 2006.

Once the hostilities ended, some official exporting and legitimate business activity resumed. For instance, Liberia signed a new deal with steel giant Mittal for the export of iron ore in summer 2005. But, as of mid-2006 Liberia was still dependent on foreign aid, and had a debt of $3.5 billion. As of 2003, Liberia had an estimated 85% unemployment rate, the second highest in the world behind only Nauru.[35]

The Liberia dollar currently trades against the U.S. dollar at a ratio of 72:1. Liberia used the U.S. dollar as its currency from 1943 until 1982. Its external debt ($3.5 billion) is huge compared to its GDP ($2.5 billion/year); it imports approximately $4.839 billion in goods per year, while it exports only about $910 million. Inflation is falling, but still significant (15% in 2003, 4.9% in the 3rd quarter of 2005); interest rates are high, with the average lending rate listed by the Central Bank of Liberia at 17.6% for 3rd quarter 2005 (although the average time deposit rate was only 0.4%, and CD rate only 4.4%, barely keeping pace with inflation).

Liberia is trying to revive its economy post civil war. Various sanctions imposed by UN on diamond and timber exports were removed by 2007. The country has the second-largest maritime registry in the world, with some 3,500 vessels registered under its flag (over 110 million gross tons), due to its status as a "flag of convenience" and its excellent reputation and ranking on the White-Lists with the relevant port state control institutions (U.S. Coast Guard, Paris MOU, Tokyo MOU).

Liberia continues to suffer with poor economic performance due to a fragile security situation, the devastation wrought by its long war, its lack of infrastructure, and necessary human capital to help the country recover from the scourges of conflict and corruption.[citation needed] However, since the election of the Sirleaf government in 2005, the country has signed several multi-billion dollar concession agreements with numerous multinational corporations, including BHP Billiton, ArcelorMittal, Chevron and APM Terminals.

Corruption

In their 2010 report, non-governmental organization Transparency International called Liberia the world's most corrupt country. When seeking attention of a selection of service providers 89% of Liberians had to pay a bribe [36].

Economic history

Foreign trade was primarily conducted for the benefit of the Americo-Liberian elite. The 1864 Ports of Entry Act severely restricted trade between foreigners and indigenous Liberians throughout most of Liberia's history. Little foreign direct investment benefited the 95% majority population, who were often subjected to forced labor on foreign concessions. Liberian law often did not protect indigenous Liberians from the extraction of rents and arbitrary taxation, and the majority survived on subsistence farming and low wage work on foreign concessions.

Weights and measures

In 1921, one authority stated, "The metric system is seldom found in Liberia,"[37] and according to the CIA Handbook, Liberia primarily uses a non-metric system of units.[38] However, in 2008, the African Development Bank stated that Liberia used the metric system.[39] Cities of the World in 2008 stated that Monrovia, the capital, used the metric system.[40] and a 2008 report from the University of Tennessee stated that the changeover from English to Metric measures was confusing to coffee and cocoa farmers, that the weighing machines were owned by the buyers and there was no system of weights and measures certification.[41]

The 2008 Liberian census used square miles to express population densities[33] but the County Development Agendas of that year were inconsistent, some giving measurements in metric units and some giving them in the older units.[42] The 2009 Annual report of the Ministry of Mines, Lands and Energy used kilometres for road distances but acres for land areas.[43]

In 2010, Government press releases used kilometers for road distances[44][45][46][47][48] though one report gave the length of a bridge in feet [49] while another press release gave one road distance in kilometers and another two in miles.[50] In the measurement of land areas, one Government press release used acres[51] while announcements from the Ministry of Agriculture have used hectares. [52] [53]

Government use of the metric system has continued in 2011. [54] In the private sector, the "Daily Observer gives weather temperature forecasts in degrees Celsius. [55]

Transport

Demographics

As of the 2008 national census, Liberia was home to 3,476,608 people.[3] Of those, 1,118,241 lived in Montserrado County, the most populous county in the country and home to the capital of Monrovia, with the Greater Monrovia district home to 970,824 people.[3] Nimba County is the next most populous county with 462,026 residents.[3] Prior to the 2008 census, the last census had been held in 1984, and it listed the population as 2,101,628.[3] The population of Liberia was 1,016,443 in 1962 and increased to 1,503,368 in 1974.[33]

The population of over 3 million comprises 16 indigenous ethnic groups and various foreign minorities. Indigenous peoples comprise about 95% of the population, the largest of which are the Kpelle in central and western Liberia. Americo-Liberians, who are descendants of African-American settlers, make up 2.5%, and Congo people, descendants of repatriated Congo and Afro-Caribbean slaves who arrived in 1825, make up an estimated 2.5%.[29][56] There is also a sizable number of Lebanese, Indians, and other West African nationals who make up a significant part of Liberia's business community. A small minority of Liberians of European descent (estimated at 18,000 in 1999; probably fewer now) reside in the country.[29]

As of 2006, Liberia has the highest population growth rate in the world (4.50% per annum). Similar to its neighbors, it has a large youth population, with half of the population under the age of 18.

Of the population, 4% hold indigenous beliefs, 85% are Christians, and 12% are Muslims.[3]

Health

Life expectancy at birth was at 44.7 in 2005.[57] The fertility rate was at 6.8 births per woman in the early 21st century.[57] Expenditure on health was 22 USD (PPP) in 2004.[57] The infant mortality rate was at 15.7% in 2005[57] (155.8 deaths for every 1000 live births).[58] The HIV/AIDS prevalence was at 1.7 percent of the adult population as of January, 2009.[59]

Culture

Liberia was traditionally noted for its hospitality, academic institutions, cultural skills, and arts/craft works. Liberia has a long, rich history in textile arts and quilting. The free and former U.S. slaves who emigrated to Liberia brought with them their sewing and quilting skills. The census of 1843 indicated a variety of occupations, including hatter, milliner, seamstress and tailor.[60] Liberia hosted National Fairs in 1857 and 1858 in which prizes were awarded for various needle arts. One of the most well-known Liberian quilters was Martha Ann Ricks,[61] who presented a quilt featuring the famed Liberian coffee tree to Queen Victoria in 1892.

In modern times, Liberian presidents would present quilts as official government gifts. The John F. Kennedy Library and Museum collection includes a cotton quilt by Mrs. Jemima Parker which has portraits of both Liberian president William Tubman and JFK. Zariah Wright-Titus founded the Arthington (Liberia) Women's Self-Help Quilting Club (1987). In the early 1990s, Kathleen Bishop documented examples of appliquéd Liberian quilts. When current Liberian President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf moved into the Executive Mansion, she reportedly had a Liberian-made quilt installed in her presidential office.[62]

The tallest man-made structure of Africa, the mast of former Paynesville Omega transmitter, is situated in Liberia.

Religion

It is estimated that as much as 40 percent of the population of Liberia practices either Christianity or Christianity combined with elements of traditional indigenous religious beliefs.[63] Approximately 40 percent exclusively practices traditional indigenous religious beliefs.[63] An estimated 20 percent of the population practices Islam.[63] A very small percentage is Bahá'í, Hindu, Sikh, or Buddhist

Education

The University of Liberia is the country's largest college and is located in Monrovia. Opened in 1862, it is one of Africa's oldest institutes of higher learning organized based upon the western model. Civil war severely damaged the university in the 1990s, but the university has begun to rebuild following the restoration of peace. The school includes six colleges, including a medical school and the nation's only law school, Louis Arthur Grimes School of Law.[64]

Cuttington University was established by the Episcopal Church of the USA (ECUSA) in 1889; its campus is currently located in Suakoko, Bong County, 120 miles (190 km) north of Monrovia). The private school, the oldest private college in Liberia, also holds graduate courses in Monrovia.

In 2009, Tubman University in Harper, Maryland County became only the second public university in Liberia.

According to statistics published by UNESCO for 2004 65% of primary-school age and 24% of secondary-school age children were enrolled in school.[65] This is a significant increase on previous years; the statistics also show substantial numbers of older children going back to earlier school years. On average, children attain 10 years of education, 11 for boys and 8 for girls.[29] Children ages five to eleven are required by law to attend school, though enforcement is lax.[66] A 1912 law required children ages 6 to 16 to attend school.[67] The African Methodist Episcopal University is another fast growing university in the capital.

See also

References

- ^ Department of Economic and Social Affairs

Population Division (2009). "World Population Prospects, Table A.1" (PDF). 2008 revision. United Nations. Retrieved 2009-03-12.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); line feed character in|author=at position 42 (help) - ^ a b c d "Liberia". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 2010-04-21.

- ^ a b c d e f Liberia Institute of Statistics and Geo-Information Services (May 2009). "2008 National Population and Housing Census Final Results: Population by County" (PDF). 2008 Population and Housing Census. Republic of Liberia. Retrieved 2009-06-10.

- ^ https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/li.html

- ^ a b "Background on conflict in Liberia [[Paul Cuffee]] advocated settling freed slaves in Africa. He gained support from free black leaders in the U.S., and members of Congress for an early emigration plan. From 1815-1816, he financed and captained a successful voyage to British-ruled Sierra Leone where he helped a small group of African-American immigrants establish themselves. Cuffee believed that African Americans could more easily "rise to be a people" in Africa than in the U.S. where slavery and legislated limits on black freedom were still in place. Although Cuffee died in 1817, his early efforts to help repatriate African Americans encouraged the [[American Colonization Society]] (A.C.S.) to lead further settlements. The ACS was made up mostly of Quakers and slaveholders, who disagreed on the issue of slavery but found common ground in support of repatriation. Friends opposed slavery but believed blacks would face better chances for freedom in Africa than in the U.S. The slaveholders opposed freedom for blacks, but saw [[repatriation]] as a way of avoiding rebellions".

{{cite web}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help) - ^ Global Security.org History of Liberia

- ^ Defense Language Institute Foreign Language Center, Liberia in Perspective: An Orientation Guide (2006) , page 1

- ^ Financial Times World Desk Reference (2004) Dorling Kindersley Publishing. p 368

- ^ Europeans in west africa 1450-1560 (1943) Hesperides Press p 175

- ^ Runn-Marcos, K. T. Kolleholon, B. Ngovo, p. 5

- ^ Runn-Marcos, K. T. Kolleholon, B. Ngovo, p. 6

- ^ "Maps of Liberia 1830-1870" (Oct. 19, 1998). Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division. Retrieved September 1, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Bateman, Graham (2000). Encyclopedia of World Geography. New York: Barnes & Noble Books. p. 161. ISBN 1566192919.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Maggie Montesinos Sale (1997). The slumbering volcano: American slave ship revolts and the production of rebellious masculinity, p.264. Duke University Press, 1997. ISBN 0-8223-1992-6

- ^ "Introduction - Social Aspects of the Civil War". Itd.nps.gov. Retrieved 2010-07-04.

- ^ Merriam Webster, p.684

- ^ Harry Johnston, Liberia, volume 1 (1906), Hutchinson & Co., pages 198–199.

- ^ Adekeye Adebajo, Liberia's Civil War: Nigeria, ECOMOG, and Regional Security in West Africa (2002), International Peace Academy, page 21.

- ^ Flint, John E. The Cambridge history of Africa: from c.1790 to c.1870 Cambridge University Press (1976) pg 184-199

- ^ The Mask of Anarchy, by Stephen Ellis, 2001, p.75 (There is also an NYU Press Updated Edition 2006, ISBN 0-8147-2238-5)

- ^ Adekeye Adebajo, 'Liberia's Civil War: Nigeria, ECOMOG, and Regional Security in West Africa,' Lynne Rienner/International Peace Academy, 2002, p.107

- ^ Adekeye Adebajo, 'Liberia's Civil War: Nigeria, ECOMOG, and Regional Security in West Africa,' Lynne Rienner/International Peace Academy, 2002, p.108

- ^ "Center for American Progress". Americanprogress.org. Retrieved 2010-07-04.

- ^ Hinch, Jim (2009-03-12). "Guideposts review". Guideposts.com. Retrieved 2010-07-04. [dead link]

- ^ "November 2009 MEDIAGLOBAL". Mediaglobal.org. 2009-11-01. Retrieved 2010-07-04.

- ^ "LIBERIA: War-battered nation launches truth commission". IRIN Africa. Retrieved 2008-05-16.

- ^ Special Court for Sierra Leone, http://www.sc-sl.org/Documents/SCSL-03-01-PT-263.pdf

- ^ Liberia in Perspective: An Orientation Guide (2006) Defense Language Institute Foreign Language Center, page 2

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Liberia". CIA - The World Factbook. United States Central Intelligence Agency. April 2, 2009. Retrieved 2009-04-08.

- ^ He's Got the Law (Literally) in His Hands Foreign Policy, November 12, 2009

- ^ Amnesty International, ^ Report 2006

- ^ Financial Time's World Desk Reference (2004) Dorling Kindersley Publishing. p 368

- ^ a b c d e f "2008 National Population and Housing Census: Preliminary Results" (PDF). Government of the Republic of Liberia. 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-14. Cite error: The named reference "census2008" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ http://www.state.gov/r/pa/ei/bgn/6618.htm

- ^ https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/rankorder/2129rank.html

- ^ Global Corruption Barometer 2010, Transperancy International, published 09 December 2010

- ^ National Industrial Conference Board (1921). The Metric Versus the English System of Weights and Measures. The Century Co/BiblioBazaar, LLC. ISBN 9780554575537. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ "CIA The World Factbook". Appendix G: Weights and Measures. US Central Intelligence Agency. 2010. Retrieved 24 April 2010.

- ^ "African Development Bank - World Bank Joint Assistance Strategy 2008-2011 and eligibility to the Fragile States Facility" (PDF). PDF Document. African Development Bank. November 2008. p. i. Retrieved 24 April 2010.

- ^ "cities of the World Monrovia". web pages. Advameg Inc. 2008. Retrieved 24 April 2010.

- ^ Dr. Michael D. Wilcox, Jr. Department of Agricultural Economics University of Tennessee (2008). "Reforming Cocoa and Coffee Marketing in Liberia" (PDF). Presentation and Policy Brief. University of Tennessee. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ^ Government of Liberia (2008). "County Development Agendas". Government of the Republic of Liberia. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ^ Eugene H. Shannon (31 December 2009). "Annual report" (PDF). Annual report. Liberian Ministry of Lands, Mines and Energy. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ^ "Amidst Heavy Downpour of Rain, Public Works Minister intensifies Project Monitoring Exercises". web page. Ministry of Public Works. Retrieved 10 November 2010.

- ^ "Infrastructure and Basic Services". web page. Government of the Republic of Liberia. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- ^ "MPW TO OPEN FIRST POST-WAR REGIONAL HEADQUATER IN BONG COUNTY". web page. Government of the Republic of Liberia. 19 April 2010. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- ^ "Public Works Minister Samuel Kofi Woods, II says priority will be given to the rehabilitation of farm to market road in the next budgetary period". web page. Government of the Republic of Liberia. 11 March 2010. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ^ "Work on Belle Yella Road will be Accelerated and Completed -Says Acting Public Works Boss". press release. Government of the Republic of Liberia. 18 May 2010. Retrieved 30 May 2010.

- ^ "Toe Town Bridge renovation". web page press release. Government of the Republic of Liberia. 12 March 2010. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ^ "Road rehabilitation work in Bong County,and Southeastern Liberia". Web Page Press Release. Government of the Republic of Liberia. 12 March 2010. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- ^ "Liberia and Libya to Play Direct Role to Speed Up Project Implementation". Press Release. Government of the Republic of Liberia. 14 April 2010. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ^ "Sime Darby take-over". Press Release. Republic of Liberia, Ministry of Agriculture. 4 January 2010. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ^ {{cite web |url=http://www.moa.gov.lr/press.php?news_id=129 |title=GOL launches US$24M Agriculture Project |date= 25 March 2010 |work=Press Release |publisher=Republic of Liberia, Ministry of Agriculture |accessdate=17 December 2010

- ^ http://www.emansion.gov.lr/content.php?sub=Infrastructure/Services&related=Major%20Issues

- ^ http://www.liberianobserver.com/forecast

- ^ "Liberia's Ugly Past: Re-writing Liberian History". Theperspective.org. Retrieved 2010-01-03.

- ^ a b c d "Human Development Report 2009 - Liberia". Hdrstats.undp.org. Retrieved 2010-01-03.

- ^ "Republic of LIBERIA Humanitarian Country Profile". Irinnews.org. Retrieved 2010-07-04.

- ^ "HIV/AIDS Rate der Erwachsenen - Landkarte - Welt". Indexmundi.com. Retrieved 2010-01-03.

- ^ Shick, Tom W. "Roll of Emigrants to Liberia, 1820-1843 and Liberian Census Data, 1843". University of Wisconsin–Madison. Retrieved 2008-12-12.

- ^ "Martha Ricks". National Portrait Gallery. Retrieved 2008-12-12.

- ^ "Liberia: It's the Little Things - A Reflection on Ellen Johnson Sirleaf's Journey to the Presidency". allAfrica.com. Retrieved 2008-05-16.

- ^ a b c International Religious Freedom Report 2007: Liberia. United States Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor (September 14, 2007). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Jallah, David A. B. “Notes, Presented by Professor and Dean of the Louis Arthur Grimes School of Law, University of Liberia, David A. B. Jallah to the International Association of Law Schools Conference Learning From Each Other: Enriching the Law School Curriculum in an Interrelated World Held at Soochow University Kenneth Wang School of Law, Suzhou, China, October 17-19, 2007.” International Association of Law Schools. Retrieved on September 1, 2008.

- ^ "UNESCO Schooling data". Uis.unesco.org. Retrieved 2010-07-04.

- ^ "LIBERIA: Go to school or go to jail". IRN. UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. 21 September 2007. Retrieved 2009-04-08.

- ^ "Profile - Liberia". Institute for African Development. Retrieved 2009-04-08.

Bibliography

- Hadden, Robert Lee. 2006. "The Geology of Liberia: a Selected Bibliography of Liberian Geology, Geography and Earth Science." Topographic Engineering Center, now the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Army Geospatial Center Alexandria, Virginia. Abstract: "Originally prepared by the U.S. Geological Survey Library staff as part of an U.S. Department of State project to restore the Geological Library of Liberia, 1998-1999. Revised and Updated through 2006."

- Gilbert, Erik & Reynolds, Jonathon T (2004) Africa in World History, From Prehistory to the Present. Pearson Education Canada Ltd pg 357 ISBN 978-0-13-092907-5

- Merriam Webster Inc. (1997) Merriam Webster's Geographical Dictionary: 3rd Edition. Merriam Webster Inc. Springfield, Massachusetts ISBN 0-87779-546-0

- Runn-Marcos, K. T. Kolleholon, B. Ngovo (2005)Liberians: An Introduction to their History and Culture. Center for Applied Linguistics, Washington, D.C.

Further reading

- Chasing the Devil by Tim Butcher. An account of a 350 mile trek through Liberia undertaken in 2009 along the route used in 1935 by Graham and Barbara Greene. Published in 2010 by Chatto & Windus ISBN 978 – 070 - 1183608

- Journey Without Maps by Graham Greene. An account of a four-week walk through the interior of Liberia in 1935. Reprinted in 2006 by Vintage ISBN 978-0-09-928223-5

- Too Late to Turn Back by Barbara Greene. Account by a cousin of Graham Greene of the above-mentioned 1935 journey, on which she was also a participant.

- Great Tales of Liberia by Wilton Sankawulo. Dr. Sankawulo is the compiler of these tales from Liberia and about Liberian culture. Published by Editura Universitatii "Lucian Blaga";; din Sibiu, Romania, 2004. - ISBN 973-651-838-8

- Sundown at Dawn: A Liberian Odyssey by Wilton Sankawulo. Recommended by the Cultural Resource Center, Center for Applied Linguistics for its content concerning Liberian culture. ISBN 0-9763565-0-3

- [1]

- [2]

- Mississippi in Africa: The Saga of the Slaves of Prospect Hill Plantation and Their Legacy in Liberia Today, by Alan Huffman (Gotham Books, 2004)

- To Liberia: Destiny's Timing, by Victoria Lang (Publish America, Baltimore, 2004, ISBN 1-4137-1829-9). A fast-paced gripping novel of the journey of a young Black couple fleeing America to settle in the African motherland of Liberia.

- Liberia: The Heart of Darkness by Gabriel I. H. Williams, Publisher: Trafford Publishing (July 6, 2006) ISBN 1-55369-294-2

- Liberia: Portrait of a Failed State by John-Peter Pham, ISBN 1-59429-012-1

- Godfrey Mwakikagile, Military Coups in West Africa Since The Sixties, Chapter Eight: Liberia: 'The Love of Liberty Brought Us Here,' pp. 85 – 110, Nova Science Publishers, Inc., Huntington, New York, 2001; Godfrey Mwakikagile, The Modern African State: Quest for Transformation, Chapter One: The Collapse of A Modern African State: Death and Rebirth of Liberia, pp. 1 – 18, Nova Science Publishers, Inc., 2001.

- Redemption Road: The Quest for Peace and Justice in Liberia (A Novel) by Elma Shaw, with a Foreword by President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf. (Cotton Tree Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0-9800774-0-7)

- House at Sugar Beach: In Search of a Lost African Childhood by Helene Cooper (Simon & Schuster, 2008, ISBN 0-7432-6624-2)

External links

- Government

- Executive Mansion official government website

- House of Representatives

- Chief of State and Cabinet Members

- General information

- "Liberia". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency.

- Liberia from UCB Libraries GovPubs

- Template:Dmoz

Wikimedia Atlas of Liberia

Wikimedia Atlas of Liberia- Liberia Districts Comprehensive resource about Liberia counties and districts

- News media

- Liberian Observer newspaper

- Liberia news headlines from allAfrica.com

- Liberia world Liberia news & information

- Liberia MyTurn Storytelling Site

- Travel

- Other

- Maps of Liberia 1830-1870 Library of Congress Geography and Map Division - contains a digitized collection of American Colonization Society (ACS) Liberian maps. Retrieved September 1, 2009.

- Liberian Law - Cornell Law Library - contains digitized documents dealing with the creation of the nation of Liberia and the laws enacted at its foundation, as well as extensive links for further research

- Liberia Online Community

- Liberian reconstruction from Reuters AlertNet

- Liberia Past and Present: Past and Present of Africa's Oldest Republic