Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas: Difference between revisions

Copy Edits. |

|||

| Line 34: | Line 34: | ||

==Plot== |

==Plot== |

||

As the story begins, ships of several nations spot a mysterious [[sea monster]], which some suggest to be a giant [[narwhal]]; the creature also damages an [[ocean liner]]. The United States government finally assembles an expedition in [[New York City]] to track down and destroy the menace. Professor Pierre Aronnax, an expert French [[Marine biology|marine biologist]] and narrator of the story, who happens to be in New York at the time, receives a last-minute invitation to join the expedition, and he accepts. [[Canadian]] master [[harpoon]]ist Ned Land and Aronnax's faithful |

As the story begins, ships of several nations spot a mysterious [[sea monster]], which some suggest to be a giant [[narwhal]]; the creature also damages an [[ocean liner]]. The United States government finally assembles an expedition in [[New York City]] to track down and destroy the menace. Professor Pierre Aronnax, an expert French [[Marine biology|marine biologist]] and narrator of the story, who happens to be in New York at the time, receives a last-minute invitation to join the expedition, and he accepts. [[Canadian]] master [[harpoon]]ist Ned Land and Aronnax's faithful Belgian servant Conseil are also brought aboard. |

||

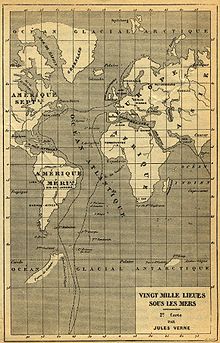

[[Image:Title page of Vingt mille lieues sous les mers.jpg|thumb|left|''Title page'' (1871)]] |

[[Image:Title page of Vingt mille lieues sous les mers.jpg|thumb|left|''Title page'' (1871)]] |

||

Revision as of 00:43, 2 October 2013

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Front page of Vingt mille lieues sous les mers | |

| Author | Jules Verne |

|---|---|

| Original title | Vingt mille lieues sous les mers |

| Translator | Mercier Lewis |

| Illustrator | Alphonse de Neuville and Édouard Riou[citation needed] |

| Language | French |

| Series | The Extraordinary Voyages #6 |

| Genre | Science fiction, adventure novel |

| Publisher | Pierre-Jules Hetzel |

Publication date | 1870 |

| Publication place | France |

| Media type | Print (Hardcover) |

| ISBN | N/A Parameter error in {{ISBNT}}: invalid character |

| Preceded by | In Search of the Castaways |

| Followed by | Around the Moon |

Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (Template:Lang-fr) is a classic science fiction novel by French writer Jules Verne published in 1870. It tells the story of Captain Nemo and his submarine Nautilus, as seen from the perspective of Professor Pierre Aronnax. The original edition had no illustrations; the first illustrated edition was published by Hetzel with illustrations by Alphonse de Neuville and Édouard Riou.

Title

The title refers to the distance traveled while under the sea and not to a depth, as 20,000 leagues is over six times the diameter of Earth. The greatest depth mentioned in the book is four leagues. In the book, a league is equivalent to four kilometres.[1] A literal translation of the French title would end in the plural "seas", thus implying the "seven seas" through which the characters of the novel travel; however, the early English translations of the title used "sea", meaning the ocean in general.

Plot

As the story begins, ships of several nations spot a mysterious sea monster, which some suggest to be a giant narwhal; the creature also damages an ocean liner. The United States government finally assembles an expedition in New York City to track down and destroy the menace. Professor Pierre Aronnax, an expert French marine biologist and narrator of the story, who happens to be in New York at the time, receives a last-minute invitation to join the expedition, and he accepts. Canadian master harpoonist Ned Land and Aronnax's faithful Belgian servant Conseil are also brought aboard.

The expedition departs Brooklyn aboard United States Navy Abraham Lincoln and travels south around Cape Horn into the Pacific Ocean. The ship finds the monster after a long search and then attacks the beast, which damages the steering. The three protagonists are then hurled onto the "hide" of the creature, which they find, to their surprise, is a large metal construction. They are quickly captured and brought inside the vessel, where they meet its enigmatic creator and commander, Captain Nemo.

The rest of the story follows the adventures of the protagonists aboard the creature--the submarine, the Nautilus--which was built in secrecy and now roams the seas free from any land-based government. Captain Nemo's motivation is implied to be both a scientific thirst for knowledge and a desire for revenge on (and self-imposed exile from) civilization. Nemo explains that his submarine is electrically powered and can perform advanced marine biology research; he also tells his new passengers that although he appreciates conversing with such an expert as Aronnax, maintaining the secrecy of his existence requires never letting them leave. Aronnax is enthralled by the undersea vistas, but Land constantly plans escape.

The visit many places in the world's oceans, some known to Jules Verne from real travelers' descriptions and speculation, while others completely fictional. Thus, the travelers witness the real corals of the Red Sea, the wrecks of the battle of Vigo Bay, the Antarctic ice shelves, and the fictional submerged land of Atlantis. The travelers also don diving suits to hunt sharks and other marine life with specially designed guns and have a funeral for a crew member who dies when an accident occurs inside the Nautilus. When the Nautilus returns to the Atlantic Ocean, a "poulpe" (usually translated as a giant squid, although the French "poulpe" means "octopus") attacks the vessel and devours a crew member.

Throughout the story Captain Nemo is suggested to have exiled himself from the world after an encounter with his oppressive country somehow affected his family. Near the end of the book, the Nautilus is tracked and attacked by a mysterious ship from that nation. Nemo ignores Aronnax's pleas for amnesty for the boat and retaliates. He attacks the ship under the waterline, sending it to the bottom of the ocean with all crew aboard as Aronnax watches from the saloon. Nemo bows before the pictures of his wife and children and is plunged into deep depression after this encounter, and "voluntarily or involuntarily" allows the submarine to wander into an encounter with the Moskenstraumen, more commonly known as the "Maelstrom", a whirlpool off the coast of Norway. The three prisoners successfully seize this opportunity to escape, but the fate of Captain Nemo and his crew is unknown.

Themes and subtext

Captain Nemo's name is a subtle allusion to Homer's Odyssey, a Greek epic poem. In The Odyssey, Odysseus meets the monstrous cyclops Polyphemus during the course of his wanderings. Polyphemus asks Odysseus his name, and Odysseus replies that his name is "Utis" (ουτις), which translates as "No-man" or "No-body". In the Latin translation of the Odyssey, this pseudonym is rendered as "Nemo", which in Latin also translates as "No-man" or "No-body". Similarly to Nemo, Odysseus must wander the seas in exile (though only for 10 years) and is tormented by the deaths of his ship's crew.

Jules Verne several times mentions Commander Matthew Fontaine Maury, "Captain Maury" in Verne's book, a real-life oceanographer who explored the winds, seas, currents, and collected samples of the bottom of the seas and charted all of these things, and Jules Verne would have known of Matthew Maury's international fame and perhaps Maury's French ancestry.

References are made to other such Frenchmen as Jean-François de Galaup, comte de Lapérouse, a famous explorer who was lost while circumnavigating the globe; Dumont D'Urville, the explorer who found the remains of Lapérouse's ship; and Ferdinand Lesseps, builder of the Suez Canal and the nephew of the sole survivor of Lapérouse's expedition. The Nautilus seems to follow the footsteps of these men: she visits the waters where Lapérouse was lost; she sails to Antarctic waters and becomes stranded there, just like D'Urville's ship, the Astrolabe; and she passes through an underwater tunnel from the Red Sea into the Mediterranean.

The most famous part of the novel, the battle against a school of giant cuttlefish, begins when a crewman opens the hatch of the boat and gets caught by one of the monsters. As the tentacle that has grabbed him pulls him away, he yells "Help!" in French. At the beginning of the next chapter, concerning the battle, Aronnax states that: "To convey such sights, one would take the pen of our most famous poet, Victor Hugo, author of The Toilers of the Sea". The Toilers of the Sea also contains an episode where a worker fights a giant octopus, wherein the octopus symbolizes the Industrial Revolution. It is probable that Verne borrowed the symbol, but used it to allude to the Revolutions of 1848 as well, in that the first man to stand against the "monster" and the first to be defeated by it is a Frenchman.

In several parts of the book, Captain Nemo is depicted as a champion of the world's underdogs and downtrodden. In one passage, Captain Nemo is mentioned as providing some help to Greeks rebelling against Ottoman rule during the Cretan Revolt of 1866–1869, proving to Arronax that he had not completely severed all relations with mankind outside the Nautilus after all. In another passage, Nemo takes pity on a poor Indian pearl diver who must do his diving without the sophisticated diving suit available to the submarine's crew, and who is doomed to die young due to the cumulative effect of diving on his lungs. Nemo approaches him underwater and gives him a whole pouch full of pearls, more than he could have acquired in years of his dangerous work. Nemo remarks that the diver as an inhabitant British Colonial India, "is an inhabitant of an oppressed country".

Some of Verne's ideas about the not-yet-existing submarines which were laid out in this book turned out to be prophetic, such as the high speed and secret conduct of today's nuclear attack submarines, and (with diesel submarines) the need to surface frequently for fresh air.[citation needed] However, Verne depicted the Nautilus as capable of diving freely into even the deepest of ocean depths, where in modern-day reality it is still not possible for a submarine to do so without being crushed by the weight of water above it. Only specially-purposed submergence vehicles such as bathyscaphe Trieste in 1960 and DSV DeepSea Challenger in 2012 reached the deepest point on Earth in the Mariana Trench with a man aboard.

Verne took the name "Nautilus" from one of the earliest successful submarines, built in 1800 by Robert Fulton, who later invented the first commercially successful steamboat. Fulton's submarine was named after the paper nautilus because it had a sail. Three years before writing his novel, Jules Verne also studied a model of the newly developed French Navy submarine Plongeur at the 1867 Exposition Universelle, which inspired him for his definition of the Nautilus.[2] The world's first operational nuclear-powered submarine, the United States Navy's USS Nautilus (SSN-571) was named for Verne's fictional vessel.[citation needed]

Verne can also be credited with glimpsing the military possibilities of submarines, and specifically the danger which they posed to the naval superiority of the Royal Navy, composed of surface warships. The fictional sinking of a ship by Nemo's Nautilus was to be enacted again and again in reality, in the same waters where Verne predicted it, by German U-boats in both World Wars.

The breathing apparatus used by Nautilus divers is depicted as an untethered version of underwater breathing apparatus designed by Benoit Rouquayrol and Auguste Denayrouze in 1865. They designed a diving set with a backpack spherical air tank that supplied air through the first known demand regulator.[3][4] The diver still walked on the seabed and did not swim.[3] This set was called an aérophore (Greek for "air-carrier"). Air pressure tanks made with the technology of the time could only hold 30 atmospheres, and the diver had to be surface supplied; the tank was for bailout.[3] The durations of 6 to 8 hours on a tankful without external supply recorded for the Rouquayrol set in the book are greatly exaggerated.

No less significant, though more rarely commented on, is the very bold political vision (indeed, revolutionary for its time) represented by the character of Captain Nemo. As revealed in the later Verne book The Mysterious Island, Captain Nemo is a descendant of Tipu Sultan, a Muslim ruler of Mysore who resisted the expansionism of the British East India Company. Nemo took to the underwater life after the suppression of the Indian Mutiny of 1857, in which his close family members were killed by the British. This change was made at the request of Verne's publisher, Pierre-Jules Hetzel, who is known to be responsible for many serious changes in Verne's books. In the original text the mysterious captain was a Polish nobleman, avenging his family who were killed by the Russians in retaliation for the captain's taking part in the Polish January Uprising of 1863. As France was at the time allied with the Russian Empire, the target for Nemo's wrath was changed to France's old enemy, the British Empire, to avoid political trouble. It is no wonder that Professor Pierre Aronnax does not suspect Nemo's origins, as these were explained only later, in Verne's next book. What remained in the book from the initial concept is a portrait of Tadeusz Kościuszko, a Polish national hero, leader of the uprising against Russia in 1794, with an inscription in Latin: "Finis Poloniae!" ("The end of Poland!").

The national origin of Captain Nemo was changed again in most movie realizations; in nearly all picture-based works following the book Nemo was made into a European. However, he was represented as an Indian by Omar Sharif in the 1973 European miniseries The Mysterious Island. Nemo is also depicted as Indian in a silent film version of the story released in 1916 and later in both the graphic novel and the movie The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen. In Walt Disney's 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954), a live-action Technicolor film version of the novel, Captain Nemo is a European, bitter because his wife and son were tortured to death by those in power in the fictional prison camp of Rura Penthe, in an effort to get Nemo to reveal his scientific secrets. This is Nemo's motivation for sinking warships in the film. He is played in this version by the English actor James Mason, with an English accent. No mention is made of any Indians in the film.

Recurring themes in later books

Jules Verne wrote a sequel to this book: L'Île mystérieuse (The Mysterious Island, 1874), which concludes the stories begun by Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea and In Search of the Castaways. While The Mysterious Island seems to give more information about Nemo (or Prince Dakkar), it is muddied by the presence of several irreconcilable chronological contradictions between the two books and even within The Mysterious Island.

Verne returned to the theme of an outlaw submarine captain in his much later Facing the Flag. That book's main villain, Ker Karraje, is a completely unscrupulous pirate acting purely and simply for gain, completely devoid of all the saving graces which gave Nemo — for all that he, too, was capable of ruthless killings — some nobility of character.

Like Nemo, Ker Karraje plays "host" to unwilling French guests — but unlike Nemo, who manages to elude all pursuers, Karraje's career of outlawry is decisively ended by the combination of an international task force and the rebellion of his French captives. Though also widely published and translated, it never attained the lasting popularity of Twenty Thousand Leagues.

More similar to the original Nemo, though with a less finely worked-out character, is Robur in Robur the Conqueror - a dark and flamboyant outlaw rebel using an aircraft instead of a submarine — later used as a basis for the movie Master of the World.

English translations

The novel was first translated into English in 1873 by Reverend Lewis Page Mercier (aka "Mercier Lewis"). Mercier cut nearly a quarter of Verne's original text and made hundreds of translation errors, sometimes dramatically changing the meaning of Verne's original intent (including uniformly mistranslating French scaphandre (properly "diving apparatus") as "cork-jacket", following a long-obsolete meaning as "a type of lifejacket"). Some of these bowdlerizations may have been done for political reasons, such as Nemo's identity and the nationality of the two warships he sinks, or the portraits of freedom fighters on the wall of his cabin which originally included Daniel O'Connell.[5] Nonetheless, it became the standard English translation for more than a hundred years, while other translations continued to draw from it and its mistakes (especially the mistranslation of the title; the French title actually means Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Seas).

In the Argyle Press/Hurst and Company 1892 Arlington Edition, the translation and editing mistakes attributed to Mercier are missing. Scaphandre is correctly translated as "diving aparatus" and not as "cork jackets". Although the book cover refers to the title as "Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea", the title page titles the book: "Twenty Thousand Leagues Under The Seas; Or The Marvelous and Exciting Adventures Of Pierre Arronax, Conseil His Servant, And Ned Land A Canadian Harpooner."

A modern translation was produced in 1966 by Walter James Miller and published by Washington Square Press.[6] Many of Mercier's changes were addressed in the translator's preface, and most of Verne's text was restored.

In the 1960s, Anthony Bonner published a translation of the novel for Bantam Classics. A specially written introduction by Ray Bradbury, comparing Captain Nemo and Captain Ahab of Moby Dick, was also included.

Many of Mercier's errors were again corrected in a from-the-ground-up re-examination of the sources and an entirely new translation by Walter James Miller and Frederick Paul Walter, published in 1993 by Naval Institute Press in a "completely restored and annotated edition."[7] It was based on Walter's own 1991 public-domain translation, which is available from a number of sources, notably a recent edition with the title Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Seas (ISBN 978-1-904808-28-2). In 2010 Walter released a fully revised, newly researched translation with the title 20,000 Leagues Under the Seas — part of an omnibus of five of his Verne translations titled Amazing Journeys: Five Visionary Classics and published by State University of New York Press.

In 1998 William Butcher issued a new, annotated translation from the French original, published by Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-953927-8, with the title Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Seas. He includes detailed notes, an extensive bibliography, appendices and a wide-ranging introduction studying the novel from a literary perspective. In particular, his original research on the two manuscripts studies the radical changes to the plot and to the character of Nemo forced on Verne by the first publisher, Jules Hetzel.

Adaptations and variations

- "Twenty Thousand Leagues Under The Seas" (1873) – book – Edition of James R. Osgood & Company, Published by George M. Smith & Company, Boston Massachusetts, includes one hundred and ten illustrations.

- 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1874) – musical – libretto Joseph Bradford – music G. Operti.

- 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (20,000 lieues sous les mers) (1907) – The silent short movie by French filmmaker Georges Méliès.

- 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1916) – The first feature film (also silent) based on the novel. The actor/director Allan Holubar played Captain Nemo.

- 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1952) – A two-part adaptation for the science fiction television anthology Tales of Tomorrow. (Part One was subtitled The Chase, Part Two was subtitled The Escape.)

- 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954) – Probably the most well-known film adaptation of the book, directed by Richard Fleischer, produced by Walt Disney, and starring Kirk Douglas as Ned Land and James Mason as Captain Nemo.

- Captain Nemo and the Underwater City (1969) – A British film based on characters from the novel, starring Robert Ryan as Captain Nemo.

- 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1972) – An animated film by Rankin-Bass aired in the United States.

- 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1973) – An Australian Famous Classic Tales cartoon.

- Captain Nemo (Капитан Немо) (1975) – A Soviet film adaptation.

- The Undersea Adventures of Captain Nemo (1975) – A futuristic version of Captain Nemo and the Nautilus appeared in this Canadian animated television series.

- 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1976) – A Marvel Classics Comics adaptation.

- The Return of Captain Nemo (1978), sometimes known as The Amazing Captain Nemo, starred Jose Ferrer in the title role.

- The Black Hole (1979) – A very loose science fiction variation on the novel. Maximilian Schell's mad captain character is a more murderous, and considerably less sympathetic version of Captain Nemo. His hair, moustache and beard resemble those of James Mason from the 1954 film.

- 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1985) – A made-for-television animated film by Burbank Films Australia starring Tom Burlinson as Ned Land.

- Funky Fables - 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1992) - A television anime by Saban Entertainment starring Venus Terzo.

- 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1997, Village Roadshow) – A made-for-television film starring Michael Caine as Captain Nemo.

- 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1997, Hallmark) – A made-for-television film starring Ben Cross as Captain Nemo.

- Crayola Kids Adventures: 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1997) – A children's educational video program inspired from the book.

- Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (1998) - an audiobook published by Blackstone Audiobooks, with the unabridged text read by Frederick Davidson.

- The second part of the second season of Around the World with Willy Fog (1983) by Spanish studio BRB Internacional was 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea.

- Nadia: The Secret of Blue Water (1990–1991) and Nadia: The Secret of Fuzzy (1992) – A Japanese science fiction anime TV series and film directed by Hideaki Anno, and inspired by the book and exploits of Captain Nemo.

- 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (2001) – A radio drama adaption of Jules Verne's novel aired in the United States.

- 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (2002) – A DIC (now owned by Cookie Jar) children's animated television film loosely based on the novel. It premiered on television on Nickelodeon Sunday Movie Toons and was released on DVD and VHS shortly afterward by MGM Home Entertainment.

- A stage play adaptation by Walk the Plank (2003). In this version, the "Nautilese" private language used by the Nautilus's crew was kept, represented by a mixture of Polish and Persian.

- The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen (2003) – Although not a film version of the Verne novel (it is based on the comic book of the same name by Alan Moore and Kevin O'Neill), it does feature Captain Nemo (and his submarine the Nautilus) as a member of the 'League' of 19th century superheroes.

- Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (2006). A stage play adaptation by Ade Morris for the Watermill Theatre, Bagnor, England. This version was for six actors and used physical theatre to help tell the story, which emphasised parallels in Verne's original with contemporary world events.

- 30,000 Leagues Under the Sea (2007) – A modern update on the classic book starring Lorenzo Lamas as Lt. Aronnaux and Sean Lawlor as the misanthropic Captain Nemo.

Comic book and graphic adaptations

20,000 Leagues Under The Sea has been adapted into comic book format numerous times.

- In 1948, Gilberton Publishing published a comic adaptation in issue #47 of their Classics Illustrated series.[8] It was reprinted in 1955;[9] 1968;[10] 1978, this time by King Features Syndicate as issue #8 of their King Classics series; and again in 1997, this later time by Acclaim/Valiant. Art by was Henry C. Kiefer.

- In 1954, the newspaper strip Walt Disney's Treasury Of Classic Tales published a comic based on the 1954 film, which ran from August 1-December 26, 1954. This was translated into many languages worldwide. Adaptation was by Frank Reilly, with art by Jesse Marsh.

- In 1955, Dell Comics published a comic based on the 1954 film in issue #614 of their Four Color anthology series called Walt Disney's 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea.[11] This was reprinted by Hjemmet in Norway in 1955 & 1976, by Gold Key in 1963, and in 1977 was serialized in several issues of Western's The New Micky Mouse Club Funbook, beginning with issue #11190. Art was by Frank Thorne.

- In 1963, in conjunction with the first nationwide re-release of the film, Gold Key published a comic based on the 1954 film called Walt Disney's 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea.[12] This reprinted the Frank Thorne version.

- In 1973, Vince Fago's Pendulum Press published a hardcover illustrated book.[13] This collected a new version which had been previously serialized in Weekly Reader magazine. Adaptation was by Otto Binder, with art by Romy Gaboa & Ernie Patricio. This was reprinted in 1976 by Marvel Comics in issue #4 of their Marvel Classics Comics series; in 1984 by Academic Industries, Inc. as issue #C12 of their Classics Illustrated paperback book series; in 1990 again by Pendulum Press, with a new painted cover; and again, using the same cover, in 2010 by Saddleback Publishing, Inc., this time in color.

- In 1974, Power Records published a comic and record set, PR-42.[14] Art was by Rich Buckler & Dick Giordano.

- In 1976, Marvel Comics published a comic book adaptation via issue #4 of their Marvel Classics Comics line.[15] This was a reprint of the Pendulum Press version.

- In 1990, Pendulum Press published another comic based on the novel via issue #4 of their Illustrated Stories line.[16] This was a reprint of the Pendulum Press version, with a new painted cover.

- In 1992, Dark Horse Comics published a one shot comic called Dark Horse Classics.[17] This was originally announced as part of the Berkeley/First Comics Classics Illustrated series, as a full-color "prestige format" book, but was delayed when the company went bankrupt. The Dark Horse version was scaled back to a standard comic-book format with B&W interiors. It was reprinted in 2001 by Hieronymous Press as a limited-edition of 50 copies available only from the artist's website, and more recently, in 2008 from Flesk Publications as an expensive full-color book, as originally intended. Adaptation & art by Gary Gianni.

- In 1997, Acclaim/Valiant published CLASSICS ILLUSTRATED #8.[18] This was a reprint of the 1948 Gilberton version with a new cover.

- In 2001, Hieronymus Press published a reprint of the Dark Horse Comics version, with a new cover, as a limited-edition of 50 copies, available only from Gary Ginanni's website.

- In 2008, Sterling Graphics published a pop-up graphic book.[19]

- In 2009, Flesk Publications published a graphic novel called Twenty-Thousand Leagues Under The Sea.[20] This was a reprint, in color for the first time, of the Gary Gianni version.

- In 2010, Saddleback Publishing, Inc. published a new reprint of the Penculum Press version, this time in color, and reusing the 1990 cover painting.

- In 2010, Campfire Classics, a company in India, published a new version. Adaptation was by Dan Rafter, with art by Bhupendra Ahluwalia.

- In 2011, Campfire Classic published a trade paperback.[21]

References in popular culture

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2009) |

- The novel The Neverending Story by Michael Ende, and its film adaptations, uses Nemo's battle with the giant squid as an example of the unforgettable and immersive nature of great stories.

- An episode of The Super Mario Bros. Super Show!, entitled "20,000 Koopas Under the Sea", borrows many elements from the original story (including a submarine named the "Koopilus" and King Koopa referring to himself as "Koopa Nemo").

- In a 1989 episode "20,000 Leaks Under the City" of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles series is heavily based on Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, including a battle with a giant squid. This story takes place in New York City of the 1980s where a flood caused by Krang using a Super Pump has occurred.[22]

- On the popular children's show Arthur, Arthur's friend Francine names her cat Nemo, later explaining that he resembles the Captain.

- A SpongeBob SquarePants episode is called "20,000 Patties Under the Sea". It is a parody of 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea and of the traveling song "99 Bottles of Beer on the Wall".

- In the 2006 "The Evil Beneath" segment of "The Evil Beneath/Carl Wheezer, Boy Genius" season 3 double episode from the Nicktoons children's CG animated series The Adventures of Jimmy Neutron: Boy Genius references are made to similar characters and environments: Dr. Sydney Orville Moist, a paranoid dance-crazy genius scientist (parodying Captain Nemo) who lives in a hidden underwater headquarters (stationary Nautilus) at the bottom of fictional Bahama Quadrangle, takes revenge against humanity by transforming unsuspecting tourists like Jimmy, Carl and Sheen into zombie-like algae men (the Nautilus crew).[23]

- In the 1990 sci-fi comedy film, Back to the Future Part III, Dr. Emmett Brown (Christopher Lloyd) states that Jules Verne is his favourite author and adores Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea. At the end of the film, Dr. Brown introduces his two sons, named Jules and Verne respectively.

- In a 1994 Saturday Night Live sketch (featuring Kelsey Grammer as Captain Nemo) pokes fun at the misconception of leagues being a measure of depth instead of a measure of distance. Nemo tries repeatedly, though unsuccessfully, to convince his crew of this.

- One of the inaugural rides at Walt Disney World's Magic Kingdom was called 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea: Submarine Voyage and was based on the Disney movie.

- In the novel and movie Sphere, Harry Adams (played by Samuel L. Jackson) reads (and is very interested in) 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea.

- Captain Nemo is one of the main characters in Alan Moore's and Kevin O'Neill's graphic novel The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, as well as in the film.

- In the film Juno, Juno McGuff states, "You should try talking to it. 'Cause, like, supposedly they can hear you even though it's all, like, ten-thousand leagues under the sea, dude".

- In the 2001 Clive Cussler novel Valhalla Rising, reference to a submarine that "inspired" Verne's story is made as one of the central plot points; it differs in having been British, with Verne being accused of being anti-British.

- Nemo and the Nautilus, along with several other plot points, are major elements of Kevin J. Anderson's Captain Nemo: The Fantastic History of a Dark Genius.

- Lo-fi pop musician The Blow references 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea in the song True Affection, the last track on 2006 album Paper Television.

- The early-2000s novel series called the Chronicles of the Imaginarium Geographica depicts Captain Nemo in a "world within a world". In this version, Nemo is the captain of the sentient ship Yellow Dragon (stated to be the in-universe origin of the Nautilus) and therefore a prominent figure in the series. Jules Verne's character is said to be fiction based on him.

- Mentioned in Into the Wild as one of Chris McCandless' inspirations, before his trek into the Alaskan interior.

- The Nautilus is said to be based on a civil war era ship in the novel, Leviathan by David Lynn Golemon.

- An episode of the English dubbed TV series of Digimon is entitled "20,000 Digi-Leagues Under the Sea" (though the actual episode synopsis is completely unrelated).

- In the 1968 Beatles cartoon Yellow Submarine at the beginning the narrator says "Once upon a time or maybe twice there was an unearthly paradise called Pepperland, 80,000 leagues under the sea it lay or lie I'm not quite sure".

- A parody exists in the 2010 Chick-fil-A calendar "Great Works of Cow Literature" in September where the novel is referred to as 20,000 Bales Under the Sea.

- German band Alphaville, who are best known for their songs Big in Japan and Forever Young, wrote a song called "Vingt Mille Lieues Sous Les Mers", which appeared as a B-side to a single they released in 1986.

- The popular MMORPG Maple Story has the Nautilus as one of their locations.

- One of Mortadelo y Filemón's long stories is called "20,000 leguas de viaje sibilino" (20,000 leagues of sibylline travel), in which they have to go from Madrid to Lugo via Kenya, India, China and the United States without using public transport.

- On Xbox Kinect, there is a game called 20,000 Leaks where the player uses themselves to plug holes in a glass box under water.

- An achievement in World of Warcraft: Cataclysm is called "20,000 Leagues Under the Sea" and is awarded after completing a quests in the Vashj'ir zone which include travelling in a submarine, being attacked by a giant squid and ultimately trying to stop the Naga from overthrowing Neptulon. There is also a submarine built by the goblins that is remarkably similar to Disney's 1954 portrayal of the Nautilus, that they have dubbed "The Verne" (after Jules Verne).

- On February 8, 2011 the Google homepage featured an interactive logo adapted from "20,000 Leagues Under the Sea" honoring Jules Verne's 183rd birthday.[24]

- A copy of the novel briefly appears in the opening episode of the science fiction series Falling Skies about a group of survivors fighting against alien invaders. In the particular scene, main protagonist Tom Mason played by Noah Wyle mulls over which book to take with him with the other choice being A Tale of Two Cities and finally decides to take the latter instead.

- The song Nemo, from the album Once of the Finnish power metal band Nightwish.

- The movie Finding Nemo

- Serbian industrial band dreDDup were inspired by the book making their new album Nautilus

- The novel, "I, Nemo" by J. Dharma & Deanna Windham is a re-imagining of Captain Nemo's origins told from his point of view. This book ends where "Twenty Thousand Leagues Under The Sea" begins and is the first in a three part series.

See also

References

- ^ Part 2, Chapter 7 "Accordingly, our speed was 25 miles (that is, twelve four–kilometer leagues) per hour. Needless to say, Ned Land had to give up his escape plans, much to his distress. Swept along would have been like jumping off a train racing at this speed, a rash move if there ever was one."

- ^ Notice at the Musée de la Marine, Rochefort

- ^ a b c Davis, RH (1955). Deep Diving and Submarine Operations (6th ed.). Tolworth, Surbiton, Surrey: Siebe Gorman & Company Ltd. p. 693.

- ^ Acott, C. (1999). "A brief history of diving and decompression illness". South Pacific Underwater Medicine Society Journal. 29 (2). ISSN 0813-1988. OCLC 16986801. Retrieved 2009-03-17.

- ^ How Lewis Mercier and Eleanor King brought you Jules Verne

- ^ Jules Verne (author), Walter James Miller (trans). Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, Washington Square Press, 1966. Standard book number 671-46557-0; Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 65-25245.

- ^ Jules Verne (author), Walter James Miller (trans), Frederick Paul Walter (trans). Jules Verne's 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea: A Completely Restored and Annotated Edition, Naval Institute Press, 1993. ISBN 1-55750-877-1

- ^ GCD :: Cover :: Classics Illustrated #47 [O]

- ^ GCD :: Cover :: Classics Illustrated #47 [HRN128]

- ^ GCD :: Cover :: Classics Illustrated #47 [HRN166]

- ^ http://www.comicbookdb.com/graphics/comic_graphics/1/384/193573_20100305100800_large.jpg

- ^ GCD :: Cover :: Walt Disney 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea [Movie Comics] #[nn]

- ^ http://www.comicbookdb.com/graphics/comic_graphics/1/184/92146_20070501085647_large.jpg

- ^ http://www.comicbookdb.com/graphics/comic_graphics/1/444/221727_20110316150602_large.jpg

- ^ GCD :: Cover :: Marvel Classics Comics #4

- ^ http://www.comicbookdb.com/graphics/comic_graphics/1/260/128942_20080516121657_large.jpg

- ^ GCD :: Cover :: Dark Horse Classics: 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea #1

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ [2][dead link]

- ^ [3][dead link]

- ^ [4][dead link]

- ^ Ninjaturtles - 20,000 Leaks Under the City

- ^ Nickelodeon. "Jimmy Neutron: "The Evil Beneath/Carl Wheezer, Boy Genius"". Nicktoons. Retrieved 2010-08-24.

- ^ "Jules Verne's 183rd Birthday". Google. Retrieved 2012-02-09.

External links

- 20,000 Leagues under the Sea at Project Gutenberg, trans. by Lewis Mercier, 1872

- Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas, p.d. trans. by F. P. Walter prepared in 1991.

- Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Seas, full text of the Oxford University Press edition and translation by Verne scholar, William Butcher (with an introduction, notes and appendices)

- Template:Fr Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, audio version

- Articles with bare URLs for citations from August 2013

- 1870 novels

- Novels by Jules Verne

- 1870s fantasy novels

- 1870s science fiction novels

- French fantasy novels

- Science fantasy novels

- Submarines in fiction

- Maritime books

- Pirate books

- Atlantis in fiction

- Novels set in Norway

- Novels set in New York City

- Novels set in Greece

- Novels set in Spain

- Novels set in Japan

- Novels set in India

- 1860s in fiction

- French novels adapted into films