The Dancing Water, the Singing Apple, and the Speaking Bird

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

| The Dancing Water, the Singing Apple, and the Speaking Bird | |

|---|---|

The foster mother (doe) looks after the wonder-children. Artwork by John D. Batten for Jacobs's Europa's Fairy Book (1916). | |

| Folk tale | |

| Name | The Dancing Water, the Singing Apple, and the Speaking Bird |

| Aarne–Thompson grouping | ATU 707 (The Dancing Water, the Singing Apple, and the Speaking Bird; The Bird of Truth; The Three Golden Children; The Three Golden Sons) |

| Region | Sicily, Eurasia, Worldwide |

| Related | Ancilotto, King of Provino; Princess Belle-Étoile and Prince Chéri; The Tale of Tsar Saltan; The Boys with the Golden Stars; The Sisters Envious of Their Cadette |

The Dancing Water, the Singing Apple, and the Speaking Bird is a Sicilian fairy tale collected by Giuseppe Pitrè,[1] and translated by Thomas Frederick Crane for his Italian Popular Tales.[2] Joseph Jacobs included a reconstruction of the story in his European Folk and Fairy Tales.[3] The original title is "Li Figghi di lu Cavuliciddaru", for which Crane gives a literal translation of "The Herb-gatherer's Daughters."[4]

The story is the prototypical example of Aarne–Thompson–Uther tale-type 707, to which it gives its name.[5] Alternate names for the tale type are The Three Golden Sons, The Three Golden Children, The Bird of Truth, Portuguese: Os meninos com uma estrelinha na testa, lit. 'The boys with little stars on their foreheads',[6] Russian: Чудесные дети, romanized: Chudesnyye deti, lit. 'The Wonderful or Miraculous Children',[7] or Hungarian: Az aranyhajú ikrek, lit. 'The Golden-Haired Twins'.[8]

According to folklorist Stith Thompson, the tale is "one of the eight or ten best known plots in the world".[9]

Synopsis

The following is a summary of the tale as it was collected by Giuseppe Pitrè and translated by Thomas Frederick Crane.

A king walking the streets heard three poor sisters talk. The oldest said that if she married the royal butler, she would give the entire court a drink out of one glass, with water left over. The second said that if she married the keeper of the royal wardrobe, she would dress the entire court in one piece of cloth, and have some left over. The youngest said that if she married the king, she would bear two sons with apples in their hands, and a daughter with a star on her forehead.

The next morning, the king ordered the older two sisters to do as they said, and then married them to the butler and the keeper of the royal wardrobe, and the youngest to himself. The queen became pregnant, and the king had to go to war, leaving behind news that he was to hear of the birth of his children. The queen gave birth to the children she had promised, but her sisters, jealous, put three puppies in their place, sent word to the king, and handed over the children to be abandoned. The king ordered that his wife be put in a treadwheel crane.

Three fairies saw the abandoned children and gave them a deer to nurse them, a purse full of money, and a ring that changed color when misfortune befell one of them. When they were grown, they left for the city and took a house.

Their aunts saw them and were terror-struck. They sent their nurse to visit the daughter and tell her that the house needed the Dancing Water to be perfect and her brothers should get it for her. The oldest son left and found three hermits in turn. The first two could not help him, but the third told him how to retrieve the Dancing Water, and he brought it back to the house. On seeing it, the aunts sent their nurse to tell the girl that the house needed the Singing Apple as well, but the brother got it, as he had the Dancing Water. The third time, they sent him after the Speaking Bird, but as one of the conditions was that he not respond to the bird, and it told him that his aunts were trying to kill him and his mother was in the treadmill, it shocked him into speech, and he was turned to stone. The ring changed colors. His brother came after him, but suffered the same fate. Their sister came after them both, said nothing, and transformed her brother and many other statues back to life.

They returned home, and the king saw them and thought that if he did not know his wife had given birth to three puppies, he would think these his children. They invited him to dinner, and the Speaking Bird told the king all that had happened. The king executed the aunts and their nurse and took his wife and children back to the palace.

Overview

The following summary was based on Joseph Jacobs's tale reconstruction in his Europa's Fairy Book, on the general analyses made by Arthur Bernard Cook in his Zeus, a Study in Ancient Religion,[10] and on the description of the tale-type in the Aarne–Thompson–Uther Index classification of folk and fairy tales.[11][10]

The king passes by a house or other place where three sisters are gossiping or talking, and the youngest says, if the king married her, she would bear him "wondrous children"[12] (their peculiar appearances tend to vary, but they are usually connected with astronomical motifs on some part of their bodies, such as the Sun, the moon or stars). The king overhears their talk and marries the youngest sister, to the envy of the older ones or to the chagrin of the grandmother. As such, the jealous relatives deprive the mother of her newborn children (in some tales, twins[a] or triplets, or three consecutive births, but the boy is usually the firstborn, and the girl is the youngest),[14] either by replacing the children with animals or accusing the mother of having devoured them. Their mother is banished from the kingdom or severely punished (imprisoned in the dungeon or in a cage; walled in; buried up to the torso). Meanwhile, the children are either hidden by a servant of the castle (gardener, cook, butcher) or cast into the water, but they are found and brought up at a distance from the father's home by a childless foster family (fisherman, miller, etc.).[15]

Years later, after they reach a certain age, a magical helper (a fairy, or the Virgin Mary in more religious variants) gives them means to survive in the world. Soon enough, the children move next to the palace where the king lives, and either the aunts, or grandmother realize their nephews/grandchildren are alive and send the midwife (or a maid; a witch; a slave) or disguise themselves to tell the sister that her house needs some marvellous items, and incite the girl to convince her brother(s) to embark on the (perilous) quest. The items also tend to vary, but in many versions there are three treasures:[16] (1) water, or some water source (e.g., spring, fountain, sea, stream) with fantastic properties (e.g., a golden fountain, or a rejuvenating liquid); (2) a magical tree (or branch, or bough, or flower, or a fruit – usually apples) with strange powers (e.g., makes music or sings); and (3) a wondrous bird that can tell the truth, knows many languages and/or turns people to stone.

The brother(s) set(s) off on his (their) journey, but give(s) a token to the sister so she knows the brother(s) is(are) alive. Eventually, the brothers meet a character (a sage, an ogre, etc.) that warns them not to listen to the bird, otherwise he will be petrified (or turned to salt, or to marble pillars). The first brother fails the quest, and so does the next one. The sister, seeing that the tokens changed colour, realizes her siblings are in danger and departs to finish the quest for the wonderful items and rescue her brother(s).

Afterwards, either the siblings invite the king or the king invites the brothers and their sister for a feast in the palace. As per the bird's instructions, the siblings display their etiquette during the meal (in some versions, they make a suggestion to invite the disgraced queen; in others, they give their poisoned meal to some dogs). Then, the bird reveals the whole truth, the children are reunited with their parents, and the jealous relatives are punished.

Variations

Folklore scholar Christine Goldberg identifies three main forms of the tale type: a variation found "throughout Europe", with the quest for the items; "an East Slavic form", where mother and son are cast in a barrel and later the sons build a palace (The Tale of Tsar Saltan and variants); and a third one, where the sons are buried and go through a transformation sequence, from trees to animals to humans again (The Boys with the Golden Stars and variants).[17]

Russian folklorist Lev Barag also noted two different formats to the tale type: the first one, "legs of gold up the knee, arms of silver up to the elbow", and the second one, "the singing tree and the talking bird".[18]

The Brother Quests for a Bride

In some regional variants, the children are sent for some magical objects, like a mirror, and for a woman of renowned beauty and great powers.[19] This character becomes the male sibling's wife at the end of the story.[20][21][22] For instance, in the Typen Turkischer Volksmärchen ("Types of Turkish Foltkales"), by folklorists Wolfram Eberhard and Pertev Naili Boratav. Type 707 is known in Turkey as Die Schöne or Güzel ("The Beautiful"). The title refers to the maiden of supernatural beauty that is sought after by the male sibling.[23]

Such variants occur in Albania, as in the tales collected by J. G. Von Hahn in his Griechische und Albanische Märchen (Leipzig, 1864), in the village of Zagori in Epirus,[24] and by Auguste Dozon in Contes Albanais (Paris, 1881). These stories substitute the quest for the items for the search for a fairy named E Bukura e Dheut ("Beauty of the Land"), a woman of extraordinary beauty and magical powers.[25][26] One such tale is present in Robert Elsie's collection of Albanian folktales (Albania's Folktales and Legends): The Youth and the Maiden with Stars on their Foreheads and Crescents on their Breasts.[27][28]

Another version of the story is The Tale of Arab-Zandyq,[29][30] in which the brother is the hero who gathers the wonderful objects (a magical flower and a mirror) and their owner (Arab-Zandyq), whom he later marries. Arab-Zandyq replaces the bird and, as such, tells the whole truth during her wedding banquet.[31][32]

In a specific Armenian variant, called The Twins, the last quest for the brother is to find the daughter of an Indian king and bring her to his king's palace. In this version, it is a king who overhears the sisters' nightly conversation in his search for a wife for his son. At the end, the brother marries the foreign princess and his sister reveals the truth to the court.[33]

This conclusion also happens in an Indian variant, called The Boy with the Moon on his Forehead, from Bengali. In this tale, the seventh queen begets the wonder-children (fraternal twins, a girl and a boy); the antagonists are the other six queens, who, overcome with jealousy, trick the new queen with puppies and expose the children. When they both grow up, the jealous queens set the siblings on a quest for a kataki flower, with the brother rescuing Lady Pushpavati from Rakshasas. Lady Pushpavati marries the titular "boy with the moon on his forehead" and reveals to the King her mother-in-law's ordeal and the deceit of the King's co-wives.[34]

In an extended version from a Breton source, called L'Oiseau de Vérité,[35] the youngest triplet, a king's son, listens to the helper (an old woman), who reveals herself to be a princess enchanted by her godmother. In a surprise appearance by said godmother, she prophecises her goddaughter shall marry the hero of the tale (the youngest prince), after a war with another country.

Another motif that appears in these variants (specially in Middle East and Turkey) is suckling an ogress's breastmilk by the hero.[36][20]

The Sister marries a Prince

In an Icelandic variant collected by Jón Árnason and translated in his book Icelandic Legends (1866), with the name Bóndadæturnar (The Story of the Farmer's Three Daughters, or its German translation, Die Bauerntöchter),[37] the quest focus on the search for the bird and omits the other two items. The end is very much the same, with the nameless sister rescuing her brothers Vilhjámr and Sigurdr and a prince from the petrification spell and later marrying him.[38]

Another variant where this happy ending occurs is Princesse Belle-Étoile et Prince Chéri, by Mme. D'Aulnoy, where the heroine rescues her cousin, Prince Chéri, and marries him. Another French variant, collected by Henry Carnoy (L'Arbre qui chante, l'Oiseau qui parle et l'Eau d'or, or "The tree that sings, the bird that speaks and the water of gold"), has the youngest daughter, the princess, marry an enchanted old man she meets in her journey and who gives her advice on how to obtain the items.[39]

In a tale collected in Carinthia (Kärnten), Austria (Die schwarzen und die weißen Steine, or "The black and white stones"), the three siblings climb a mountain or slope, but the brothers listen to the sounds of the mountain and are petrified. Their sister arrives at a field of white and black stones and, after a bird gives her instructions, sprinkles magic water on the stones, restoring her brothers and many others – among them, a young man, whom she later marries.[40]

In the Armenian variant Théodore, le Danseur, the brother ventures on a quest for the belongings of the eponymous character and, at the conclusion of the tale, this fabled male dancer marries the sister.[41][42]

In The Three Little Birds, collected by the Brothers Grimm, in Kinder- und Hausmärchen (KHM nr. 96), instructed by an old woman fishing, the sister strikes a black dog and it transforms into a prince, with whom she marries as the truth settles among the family.

Alternate Source for the Truth to the King (Father)

In the description of the tale type in the international index, the bird the children seek is the one to tell the king the sisters' deceit and to reunite the family.[22] However, in some regional variants, the supernatural maiden whom the brother and the sister seek is responsible for revealing the truth of their birth to the king and to restore the queen to her rightful place.[20][23][21]

In a Kaba'il version from Northern Algeria (Les enfants et la chauve-souris),[43] the bird is replaced by a bat, who helps the abandoned children when their father takes them back and his second wife prepares them a poisoned meal. The bat recommends the siblings to give their meal to animals, in order to prove it's poisoned and to reveal the treachery of the second wife.[44][need quotation to verify]

In a specific folktale from Egypt, El-Schater Mouhammed,[45] the Brother is the hero of the story, but the last item of the quest (the bird) is replaced by "a baby or infant who can speak eloquently", as an impossible MacGuffin. The fairy (or mystical woman) he sought before gives both siblings instructions to summon the being in front of the king, during a banquet.

In many widespread variants, the bird is replaced by a fairy or magical woman the Brother seeks after as part of the impossible tasks set by his aunts, and whom he later marries (The Brother Quests for a Bride format).[46]

Very rarely, it is one of the children themselves that reveal the aunts' treachery to their father, as seen in the Armenian variants The Twins and Theodore, le Danseur.[41][42] In a specific Persian version, from Kamani, the Prince (King's son) investigates the mystery of the twins and questions the midwife who helped in the delivery of his children.[47]

Motifs

According to Daniel Aranda, the tale type develops the narrative in two eras: the tale of the calumniated wife as the first; and the adventures of the children as the second, wherein the mother becomes the object of their quest.[48]

The Persecuted Wife and Jealous Sisters

Charles Fillingham Coxwell noted that the mother of the wonder children may be persecuted by her own elder sisters, by a step-relative (step-sister or step-mother), or by her mother-in-law.[49] French comparativist Emmanuel Cosquin suggested that, in a hypotethical original form of the tale, the three sisters all wished to marry the king.[50] German-Chilean philologist Rodolfo Lenz, complementing Cosquin's study, remarked that the elder sisters promise practical things, like cooking a grand meal, weaving such a garment for the king, sewing a special piece of clothing, etc.[51] Similarly, French ethnologist Camille Lacoste-Dujardin, in regards to a Kabylian variant, noted that the sisters' jealousy originated from their perceived infertility, and that their promises of grand feats of domestic chores were a matter of "capital importance" to them.[52]

Ethnologist Verrier Elwin commented that the motif of jealous queens, instead of jealous sisters, is present in a polygamous context: the queens replace the youngest queen's child (children) with animals or objects and accuse the woman of infidelity. The queen is then banished and forced to work in a humiliating job.[53] In other variants, the calumniated woman is buried up to the torso or immured as punishment for her false crime.[51]

In the same vein, French ethnologue Paul Ottino (fr), by analysing similar tales from Madagascar, concluded that the jealousy of the older co-wives of the polygamous marriage motivate their attempt on the children, and, after the children are restored, the co-wives are duly punished, paving the way for a monogamous family unit with the expelled queen.[54]

The Wonder Children

The story of the birth of the wonderful children can be found in Medieval author Johannes de Alta Silva's Dolopathos sive de Rege et Septem Sapientibus (c. 1190), a Latin version of the Seven Sages of Rome.[55] Dolopathos also comprises the Knight of the Swan cycle of stories. This version of the tale preserves the motif of the wonder-children, which are born "with golden chains around their necks", the substitution for animals and the degradation of the mother, but merges with the fairy tale The Six Swans, where brothers transformed into birds are rescued by the efforts of their sister,[56] which is Aarne-Thompson 451, "The boys or brothers transformed into birds".[57]

In a brief summary:[55][58] a lord encounters a mysterious woman (clearly a swan maiden or fairy) in the act of bathing, while clutching a gold necklace, they marry and she gives birth to a septuplet, six boys and a girl, with golden chains about their necks. But her evil mother-in-law swaps the newborn with seven puppies. The servant with orders to kill the children in the forest just abandons them under a tree. The young lord is told by his wicked mother that his bride gave birth to a litter of pups, and he punishes her by burying her up to the neck for seven years. Some time later, the young lord while hunting encounters the children in the forest, and the wicked mother's lie starts to unravel. The servant is sent out to search them, and finds the boys bathing in the form of swans, with their sister guarding their gold chains. The servant steals the boys' chains, preventing them from changing back to human form, and the chains are taken to a goldsmith to be melted down to make a goblet. The swan-boys land in the young lord's pond, and their sister, who can still transform back and forth into human shape by the magic of her chain, goes to the castle to obtain bread to her brothers. Eventually the young lord asks her story so the truth comes out. The goldsmith was actually unable to melt down the chains, and had kept them for himself. These are now restored back to the six boys, and they regain their powers, except one, whose chain the smith had damaged in the attempt. So he alone is stuck in swan form. The work goes on to say obliquely hints that this is the swan in the Swan Knight tale, more precisely, that this was the swan "quod cathena aurea militem in navicula trahat armatum ('that tugged by a gold chain an armed knight in a boat')."[55]

The motif of the heroine persecuted by the queen, on false pretenses, also happens in Istoria della Regina Stella e Mattabruna,[59] a rhyming story of the ATU 706 type (The Maiden Without Hands).[60]

India-born author Maive Stokes suggested, in her notes to the Indian version she collected, that the motif of the children's "silver chains (sic)" of the Dolopathos tale was parallel to the astronomical motifs on the children's bodies.[61]

The mother's prediction

French scholar Gédeon Huet commented on a motif of the Dolopathos tale: near the beginning of the story, after she makes love to the human lord under the veil of night, the strange maiden (called nympha in the Latin text) knows beforehand she will give birth to seven children, six boys and a girl. In Huet's opinion, this prediction can be attributed to her superhuman wisdom, since she is a fée (a supernatural woman, in the more general sense).[62][b] Huet also concluded that this detail about the fée's prediction must have originated from an earlier literary version.[64]

Professor Anne E. Duggan remarked that, in some tales of type 707, the mother (the third sister) predicts the number of children she will have, and the wonderful traits they will bear.[65][66]

Fate of the Wonder Children

When the jealous sisters or jealous co-wives replace the royal children for animals and objects, they either bury the children in the garden (the twins become trees) in some variants, or put the siblings in a box and cast it into the water (river, stream).[53]

The Floating Chest

French ethnologue Paul Ottino (fr) noted that the motif of casting the children in the water vaguely resembles the Biblical story of Moses, but, in these stories, the children are cast in a box in order to perish in the dangerous waters.[67]

Likewise, Emmanuel Cosquin listed that the motif of the "coffre flottant" ("The Floating Chest")[68][69] shows parallels with mythological accounts: Muslim/Javanese Raden Pakou, Assyro-Sumerian king Sargon, Hindu epic hero Karna.[70] Israel Levi, in an article in Revue des Études Juives, complements Cosquin's analysis with instances of the same motif in Moses's narrative, in different traditions.[71]

The animal foster parent

After the stepmother or queen's sisters abandon the babies in the forest, in several variants the twins or triplets are reared by a wild animal.[72] This motif also appears in versions of the tale of the Knight of the Swan: the nympha's children are suckled by a hind (in the Dolopathos), or by a "fair white goat" in the Beatrix redaction.[73]

The episode recalls similar mythological stories about half-human, half-divine sons abandoned in the woods and suckled by a female animal. Such stories have been dramatized in Ancient Greek plays of Euripides and Sophocles.[74] This episode also happens in myths about the childhood of some gods (e.g, Zeus and fairy or she-goat Amalthea, Telephus, Dionysus). Professor Giulia Pedrucci suggests that the unusual breastfeeding by the female animal (i.e., by a cow, a hind, a deer, a she-wolf) sets the hero apart from the "normal" and "civilized" world and puts them on a road to achieve a great destiny, since many of these heroes and gods become founders of dynasties and/or kings.[75]

Astronomical signs on bodies

The motif of astronomical signs on the children's bodies has been compared to a similar motif in Russian fairy tales and healing incantations, as in the formula "a red star or sun in the front, a moon on the back of the neck and a body covered with stars".[7] Lithuanian scholarship (Dainius Razauskas, Birutė Jasiūnaitė, Norbertas Velius) have also compared the imagery to Lithuanian fairy tales: the queen gives birth to children with solar/lunar/astral birthmarks.[76][77][78][c] However, Western scholars interpret the motif as a sign of royalty[80] or an indicative of the children's noble birth.[66]

19th-century India-born author Maive Stokes noted that the motif of children born with stars, moon or a sun in some part of their bodies occurred to heroes and heroines of both Asian and European fairy tales.[81]

Apart from the astronomical motifs, scholarship points another sign that marks the extraordinary children: a metallic colour on some body part. In the East Slavic tale type SUS 707, the wonderful children are described as having arms of gold up to the elbow and legs of silver up to the knee.[82] According to Russian folklorist S. Y. Neklyudov, in tales from the Mongolic peoples, the children show a golden chest, often combined with a silver backside.[83] Barbara Walker noted that the colour of the children's hair (golden or silver) also serves to distinguish them,[84] and, according to Christine Goldberg, their adoptive parents may sell their metallic hair.[72]

Literary historian Reinhold Köhler noted another set of motifs that mark the wonder children: the presence of a chain of gold or silver around their necks or on their skin.[85]

In the same vein, Russian professor Khemlet Tat'yana Yur'evna suggests that the presence of the astronomical motifs on the children's bodies possibly refer to their connection to a celestial or heavenly realm. She also argues that similar motifs (golden chains, body parts shining like gold and/or silver, golden hair and silver hair) are a reminiscence or vestige of the solar/lunar/astral motif (which corresponds to the oldest layer). Finally, tales of later tradition that lack either one of these motifs replace them with special attributes or names to the children, like the Brother being a mighty hero and the Sister being a skilled weaver.[86] In a later study, Khemlet argues that variants of later tradition gradually lose the fantasy elements and a more realistic narrative emerges, with the fantastical becoming unreal and with more development of the characters' psychological state.[87]

The Three Treasures

Folklorist Christine Goldberg, in the entry of the tale type in ''Enzyklopädie des Märchens'', based on historical and geographical evidence, concluded that the quest for the treasures was a later development of the narrative, inserted into the tale type.[57]

Richard MacGillivray Dawkins stated that "as a rule there are three quests" and the third item is "almost always ... a magical speaking bird".[88] In other variants, according to scholar Hasan El-Shamy, the quest objects include "the dancing plant, the singing object and the truth-speaking bird".[14]

- The Dancing Water

Some scholars (i.e., August Wünsche, Edward Washburn Hopkins, John Arnott MacCulloch) have proposed that the quest for the Dancing Water in these tales is part of a macrocosm of similar tales about the quest for a Water of Life or Fountain of Immortality.[89][90][91] Czech scholar Jaromír Jech remarked that, in this tale type, after the heroine quests for the speaking bird, the singing tree and the water of life, she uses the water as remedy to restore her brothers after they are petrified for failing the quest.[92]

In regards to Lithuanian variants where the object of the quest is the "yellow water" or "golden water", Lithuanian scholarship suggests that the color of the water evokes a sun or dawn motif.[93]

- The Speaking Bird

In some variants from Middle Eastern, Arab or Armenian sources, the Speaking Bird may be named Hazaran Bulbul, Bülbülhesar or some variation thereof.[94] It has been noted that the name refers to the Persian nightingale (Pycnonotus hæmorrhous), whose complete name is Bulbul-i-hazár-dástán ("Bird of a Thousand Tales").[95]

According to August Leskien, the word bülbül comes from Persian and means "nightingale". Hazar also comes from Persian and means "a thousand". In this context, he speculated, hazar is an abbreviation of an expression that means "a thousand stories" or "a thousand voices".[96] In another translation, the name is Hazaran, meaning "bird of a thousand songs".[97] On the other hand, according to Barbara K. Walker, "Hazaran" refers to an Iranian location famed for its breed of nightingales.[98]

History and origins

Possible point of origin

Texan researcher Warren Walker and Mongolist Charles Bawden ascribe some antiquity to the tale type, due to certain "primitive" elements, such as "the alleged birth of an animal or monster to a woman".[99][d]

The Brothers Grimm, commenting on the German version they collected, De drei Vugelkens, suggested that the tale developed independently in Köterberg, due to Germanic localisms present in the text.[101]

Due to the great popularity of the tale in the Arab world, according to Ibrahim Muhawi,[102] some have theorized that the Middle East is the possible point of its origin or dispersal.[103]

On the other hand, Joseph Jacobs, in his notes on Europa's Fairy Book, proposed a European provenance, based on the oldest extant version registered in literature (Ancilotto, King of Provino).[104] Similarly, Stith Thompson tentatively concluded on a European origin, based on the distribution of the variants.[105]

Another position is sustained by folklorist Bernhard Heller, who defends the existence of "an as yet unknown tradition" that originated Straparola's and Diyab's variants.[106]

Russian scholar Yuri Berezkin suggested that the first part of the tale (the promises of the three sisters and the substitution of babies for animals/objects) may find parallels in stories of the indigenous populations of the Americas.[107]

Scholar Linda Dégh put forth a theory of a common origin for tale types ATU 403 ("The Black and the White Bride"), ATU 408 ("The Three Oranges"), ATU 425 ("The Search for the Lost Husband"), ATU 706 ("The Maiden Without Hands") and ATU 707 ("The Three Golden Sons"), since "their variants cross each other constantly and because their blendings are more common than their keeping to their separate type outlines" and even influence each other.[108]

An Asian source?

Professor Jack Zipes, in turn, proposed that, although the tale has many ancient literary sources, it "may have originated in the Orient", but no definitive source has been indicated.[109]

Swedish folklorist Waldemar Liungman considered this tale was "västorientalisk" (Western Asian) and suggested a possible origin during Hellenistic times.[110][111]

Ossetian-Russian folklorist Grigory A. Dzagurov formulated a hypothesis that the tale type developed in the east, probably in the Indo-Iranian area, since The 1,001 Nights derived from a Persian source;[e] the type is known in Central Asia, and some of its episodes are recorded in ancient Indian literature.[113]

A Persian source?

Mythologist Thomas Keightley, in his 1834 book Tales and Popular Fictions, suggested the transmission of the tale from a genuine Persian source, based on his own comparison between Straparola's literary version and the one from The Arabian Nights ("The Sisters envious of their Cadette").[114][f]

According to Waldemar Liungman, Östrup was also of the notion that tale type 707, "Drei Schwestern wollen den König haben" ("Three sisters wish to marry the king"), originated from a Persian source.[116]

As summarized by Ulrich Marzolph, an Iranian origin has been defended by Jiri Cejpek and Enno Littmann. Cejpek claimed that the tale of The Jealous Sisters was "definitely Iranian", but acknowledged that it must have not belonged to the original Persian compilation.[117]

Mahavastu

W. A. Clouston claimed that the ultimate origin of the tale was a Buddhist tale of Nepal, written in Sanskrit, about King Brahmadatta and peasant Padmavatí (Padumavati) who gives birth to twins. However, the king's other wives cast the twins in the river.[118][119] The tale of Padmavati's birth - contained within the Mahāvastu[120] - is also curious: on a hot summer day, seer Mandavya puts away a pot with urine and semen and a doe drinks it, thinking it to be water. The doe, which lives in the armitage, gives birth to a human baby. The girl is found by Mandavya and becomes a beautiful young maiden. One day, king Brahmadatta, from Kampilla, on a hunt, sees the beautiful maiden and decides to make her his wife.[121][g]

Norwu-preng'va

French scholar Gédeon Huet supplied the summary of another Asian story: a Mongolian translation of a Tibetan work titled Norwou-prengva, translated into German by European missionary Isaac Jacob Schmidt.[123][124] The Norwu-preng'wa was erroneously given as the title of the Mongolian source. However, the work is correctly named Erdeni-yin Tobci, compiled by Sagand Secen in 1662.[125][126]

In this tale, titled Die Verkörperung des Arja Palo (Avalokitas'wara oder Chongschim Bodhissatwa) als Königssöhn Erdeni Charalik, princess Ssamantabhadri, daughter of king Tegous Tsoktou, goes to bathe with her two female slaves in the river. The slaves, envious of her, suggest a test: the slaves will put their copper basins in the water, knowing it will float, and the princess should put her gold basin, unaware it will sink. It so happens and the princess, distraught at the loss of the basin, sends a slave to her father to explain the story. The slave arrives at the court of the king, who explains it will not reprimand his daughter. This slave returns and spins a lie that the king shall banish her to another kingdom with her two slaves. Resigning to her fate, she and the slaves wander to another kingdom, where they meet King Amugholangtu Yabouktchi (Jabuktschi). The monarch inquires about their skills: one slave answers she can weave clothes for one hundred men with a few pieces of fabric; the second, that she can prepare a meal worthy of one hundred men with just a handful of rice; the princess, at last, says she is a simple girl with no skills, but, due to her virtuous and pious devotion, the Three Jewels will bless her with a son "with the chest of gold, the kidneys of mother-of-pearl, the legs the color of the ougyou jewel". The "Great and Merciful Arya Palo" descends from "Mount Potaia" and enters the body of the princess. The child is born and the slaves bury him under the steps of the palace. The child gives hints of his survival and the slaves, now queens, try to hide the boy under many places of the palace, including the royal stables, which cause the horses not to approach it. The two slaves now bury the boy in the garden and a "magical plant of three colours" sprouts from the ground. The king wants to see it, but the plant has been eaten by sheep. A wonderful sheep is born some time later and, to the shepherd's surprise, it can talk. The baby sheep then transforms into a beggar youth, goes to the door of the palace and explains the whole story to the king. The youth summons a palace near the royal castle, invites the king, his mother and introduces himself as Erdeni Kharalik, their son. With his powers, he kills the envious slaves. Erdeni's story continues as a Buddhistic tale.[124]

Tripitaka

Folklorist Christine Goldberg, in the entry of the tale type in Enzyklopädie des Märchens, stated the tale of slander and vindication of the calumniated spouse appears in a story from the Tripitaka.[57]

French sinologist Édouard Chavannes translated the Tripitaka, wherein three similar stories of calumniated wives and multiple pregnancies are attested. The first one, given the title La fille de l'ascète et de la biche ("The daughter of the ascetic and the doe"), a deer licks the urine of an ascetic and becomes pregnant. It gives birth to a human child who is adopted by a brahman. She tends the fire at home. One day, the fire is put out because she played with the deer, and the brahmane sends her to fetch another flint for the fire. She comes to a house in the village, and, with every step she takes, a lotus flower sprouts. The owner of the house agrees to lend her a torch, after she circles the house three times to create a garden of lotus flowers. Her deeds reach the king's ears, who consults a diviner to see if marrying the maiden bodes well for his future. The diviner confirms it and the king marries the maiden. She becomes his queen and gives birth to one hundred eggs. The king's other wives of the harem take the eggs and throw them in the water. They are carried down by the river to another kingdom and are rescued by another sovereign. The eggs hatch and out come one hundred youths, described by the narrative as possessing great beauty, strength, and intelligence. They wage war on the neighbouring kingdoms, one of which their biological father's. Their mother climbs up a tower and shoot her breastmilk, which falls "like darts or arrows" in the mouths of the one hundred warriors. They recognize their familial bond and cease the aggressions. The narrator says that the mother of the 100 sons is Chö-miao, mother of Çakyamuni.[127][128]

In a second tale from the Tripitaka, titled Les cinq cents fils d'Udayana ("The Five Hundred Sons of Udayana"), an ascetic named T'i-po-yen (Dvaipayana) urinates on a rock. A deer licks it and becomes pregnant with a human child. It gives birth to a daughter who grows up strong and beautiful, and with the ability to spring lotus flowers with every step. She tends the fire at home and, when it is put out, she goes to a neighbour to borrow some of their bonfire. The neighbour agrees to lend it to her, but first she must circle his house seven times to create a ring of lotus flowers. King Wou-t'i yan (Udayana) sees the lotus flowers and takes the girl as his second wife. She gives birth to 500 eggs, which are replaced for 500 bags of flour by the king's first wife. The first wife throws the eggs in a box in the Ganges, which are saved by another king, named Sa-tan-p'ou. The eggs hatch and 500 hundred boys are born and grow up as strong warriors. King Sa-tan-p'ou refuses to pay his tributes to king Wou-t'i-yen and attacks him with the 500 boys. Wou-t'i-yen asks for the help of the second wife: she puts her on a white elephant and she shoots 250 jets of milk from each breast. Each jet falls in each warrior's mouth. The war is ended, mother and sons recognize each other, and the 500 sons become the "Pratyeka Buddhas".[129][130]

In a third tale, Les mille fils d'Uddiyâna ("The Thousand Sons of Uddiyâna"), the daughter of the ascetic and the deer marries the king of Fan-yu (Brahmavali) and gives birth to one thousand lotus leaves. The king's first wife replaces them for a mass of equine meat and throws them in the Ganges. The leaves are saved by the king of Wou-k'i-yen (Uddiyâna) and from every leave comes out a boy. The thousand children grow up and become great warriors, soon doing battle with the realm of Fan-yu. Their mother climbs up a tower and shoots her breastmilk into their mouths.[131][130] Cosquin attributed a similar account of this version (of the "Legend of the Thousand Sons") to 7th-century Chinese monk Xuanzang or Hiuen Tsang. In Hiuen Tsang's account, the deer's human daughter has deer paws, just like her mother.[132]

Other accounts

Comparativist Emmanuel Cosquin summarized a legend written down by 4th-century Chinese Buddhist monk Faxian. Faxian produced an account on a legendary kingdom called Vaïsâli: one of the lesser wives of the king gave birth to a lump of flesh. The other cowives suppose it is a bad omen and throw it in the Heng (Ganges) river in a box. The box washes up in another country and is found by another king. When the king opens it, the lump of flesh has become thousand little boys. He raises them and they become fine young warriors, conquering the nearby kingdoms. One day, the thousand warriors prepare to invade Vaïsâli, and the lesser queen orders the construction of a tower at the edges of the city. When the warriors arrive, the queen announces she is their mother and, to prove their connection, shoots from her breasts jets of milk that fall on each of their mouths.[133]

Cosquin also reported a narrative from the 13th-century Sri Lankan work Pûjâwaliya. In this account, the queen of Benares gives birth to a lump of flesh, which is thrown in the (Ganges) river in a box. However, by work of the devas, the box is found by an ascetic, who opens it and finds a pair of twins, a boy and a girl suckling on each other's fingers. After they grow up, they leave their village and found the city of Visâlâ.[134] Rev. R. Spence Hardy provided more details to this narrative: the prince and the princess are given the name Lichawi, due to their similar appearance, and later become the progenitors of a homonymous royal dynasty.[135]

Orientalist Mabel Haynes Bode translated a tale about Uppalavanna and published it in the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. In this tale, in a later reincarnation of Uppalavanna, she is a girl from a working class. One day, she finds a lotus blossom flower and gives it to a Pacceka Buddha, expressing her wish to give birth to as many children as there are seeds in a lotus flowers, and for flowers to spring with her every step, in her next incarnation. So it happens: she is reborn as a baby inside a lotus flower, near the foot of a mountain. A hermit finds and rears the child, naming her Padumavatî (Lotus). One day, when she is grown up and her adoptive father is away, the king's forester just happens to pass by her house. Seeing the mysterious beauty inside, he goes to inform the king of Benares. The king sees her and makes her his wife. When she is pregnant, the king has to go to war. Meanwhile, the "other women" bribe a servant to get rid of the queen's children as soon as they are born. Queen Padumavatî gives birth to 500 children, which are taken from her and put in boxes, but a last child, Maha Paduma, the Prince, "was still in her womb". The servants trick her into thinking she gave birth to a log of wood. The returning king is fooled by the deception and expels his wife from the palace. Afterwards, to celebrate his victory, he decides to hold a river-festival. The "other women" seize the opportunity to throw the children downstream. However, the king notices the objects and asks them to be opened. Sakko (or Sakka), the "king of the gods", makes a letter appear inside each box revealing the children's parentage. The king rescues his sons, restores his wife and punishes the servants. Later, the boys grow up and proclaim they are Pacceka Buddhas to their preceptor.[136] Academic Gunapala Piyasena Malalasekera provided more details to the story in his Dictionary of Pali Proper Names: her previous incarnation gives the Pacceka Buddha a lotus flower with 500 grains of fried rice (lājā) inside; some nearby 500 hunters also give honey and flesh to the same man and wish to be reborn as the woman's sons in their next life.[137]

Earliest literary sources

Scholars (i.e., Hans-Jörg Uther, Joseph Jacobs, Ruth Bottigheimer, Stith Thompson) indicate Ancilotto, King of Provino, an Italian literary fairy tale written by Giovanni Francesco Straparola in The Facetious Nights of Straparola (1550–1555),[138][139] as the first attestation of the tale type.[140][141][142]

Bottigheimer and Donald Haase also list as a predecessor Neapolitan tale La 'ngannatora 'ngannata, or L'ingannatora ingannata (English: "The deceiver deceived"), written by bishop Pompeo Sarnelli (anagrammatised into nom de plume Marsillo Reppone), in his work Posilecheata (1684).[143][144][145]

Spanish scholars suggest that the tale can be found in Iberian literary tradition of the late 15th and early 16th centuries: Lope de Vega's commedia La corona de Hungría y la injusta venganza contains similarities with the structure of the tale, suggesting that the Spanish playwright may have been inspired by the story,[146] since the tale is present in Spanish oral tradition. In the same vein, Menéndez Y Pelayo wrote in his literary treatise Orígenes de la Novela that an early version exists in Contos e Histórias de Proveito & Exemplo, published in Lisbon in 1575.[147] This Portuguese version lacks the fantastical motifs, albeit the third sister does promise to bear two boys "as beautiful as gold" and a girl "more beautiful than silver".[148][149][h]

Bottigheimer, Jack Zipes, Paul Delarue and Marie-Louise Thénèze register two ancient French literary versions: Princesse Belle-Étoile et Prince Chéri, by Mme. D'Aulnoy (of Contes de Fées fame), published in 1698,[150] and L'Oiseau de Vérité ("The Bird of Truth"), penned by French author Eustache Le Noble, in his collection La Gage touché (1700).[109][151][152]

Distribution

Late 19th-century and early 20th-century scholars (Joseph Jacobs, Teófilo Braga, Francis Hindes Groome) had noted that the story was widespread across Europe, the Middle East and India.[153][44][154][155] Portuguese writer Braga noticed its prevalence in Italy, France, Germany, Spain and in Russian and Slavic sources,[156] while Groome listed its incidence in the Caucasus, Egypt, Syria and Brazil.[157]

Russian comparative mythologist Yuri Berezkin (ru) pointed out that the tale type can be found "from Ireland and Maghreb, to India and Mongolia", in Africa and Siberia.[158]

Europe

Italy

France

Iberian Peninsula

There are also variants in Romance languages: a Spanish version called Los siete infantes, where there are seven children with stars on their foreheads,[159] and a Portuguese one, As cunhadas do rei (The King's sisters-in-law).[160] Both replace the fantastical elements with Christian imagery: the devil and the Virgin Mary.[161]

Portuguese writer, lawyer and teacher Álvaro Rodrigues de Azevedo published a versified variant from the Madeira Archipelago with the title Los Encantamentos da Grande Fada Maria.[162] Portuguese folklorist Teófilo Braga cited the Madeiran tale as a variant of the Portuguese tales he collected.[163]

Folklore researcher Elsie Spicer Eells published a variant from Azores with the title The Listening King: a king likes to disguise himself and go through the streets at night to listen to his subjects' talk. He overhears the three sisters' talk, the youngest wanting to marry him. They do and she gives birth to twin boys with a gold star on the forehead. They are cast in the sea in a basket and found by a miller and his wife. Years later, they find a parrot with green and gold feathers in the royal gardens.[164]

Portugal

Brazilian folklorist Luís da Câmara Cascudo suggested that the tale type migrated to Portugal brought by the Arabs.[165]

Portuguese folklorist Teófilo Braga published a Portuguese tale from Airão-Minho with the title As cunhadas do rei ("The King's sisters-in-law"): the king, his cook and his butler walk through the streets in disguise to listen to the thoughts of the people. They pass by a verandah where three sisters are standing. The three women notice the men and the elder recognizes the cook, wanting to marry him to eat the best fricassees; the middle one sees the butler and wants to marry him to get to drink the best liquors; the youngest sister wants to marry the king and bear him three boys with a golden star on the front. The youngest sister marries the king and bears him twin boys with the golden stars, and the next year a little girl with a golden star on the front. They are replaced for animals and cast in the water, but are saved by a miller. Years later, their aunts send them for a parrot from a garden, for the tree that drips blood and the "water of a thousand springs". The Virgin Mary appears to instruct the sister on how to get a branch from tree and a jug of the water, and how to rescue her brothers from petrification.[166][167]

Spain

United Kingdom and Ireland

According to Daniel J. Crowley, British sources point to 92 variants of the tale type. However, he specified that most variants were found in the Irish Folklore Archives, plus some "scattered Scottish and English references".[168]

Scottish folklorist John Francis Campbell mentioned the existence of "a Gaelic version" of the French tale Princesse Belle-Étoile, itself a literary variant of type ATU 707. He also remarked that "[the] French story agree[d] with Gaelic stories", since they shared common elements: the wonder children, the three treasures, etc.[169]

Ireland

Scholarship points to the existence of many variants in Irish folklore. In fact, the tale type shows "wide distribution" in Ireland. However, according to researcher Maxim Fomin, this diffusion is perhaps attributed to a printed edition of The Arabian Nights.[170]

One version was published in journal Béaloideas with the title An Triúr Páiste Agus A Dtrí Réalta: a king wants to marry a girl who can jump the highest; the youngest of three sisters fulfills the task and becomes queen. When she gives birth to three royal children, their aunts replace them with animals (a young pig, a cat and a crow). The queen is cast into a river, but survives, and the king marries one of her sisters. The children are found and reared by a sow. When the foster mother is threatened to be killed on orders of the second queen, she gives the royal children three stars, a towel that grants unlimited food and a magical book that reveals the truth of their origin.[171]

Another variant has been recorded by Irish folklorist Sean O'Suilleabhain in Folktales of Ireland, under the name The Speckled Bull. In this variant, a prince marries the youngest of two sisters. Her elder sisters replaces the prince's children (two boys), lies that the princess gave birth to animals and casts the boys in a box into the sea, one year after the other. The second child is saved by a fisherman and grows strong. The queen's sister learns of the boy's survival and tries to convince his foster father's wife that the child is a changeling. She kills the boy and buries his body in the garden, from where a tree sprouts. Some time later, the prince's cattle grazed near the tree and a cow eats its fruit. The cow gives birth to a speckled calf that becomes a mighty bull. The queen's sister suspects the bull is the boy and feigns illness to have it killed. The bull escapes by flying to a distant kingdom in the east. The princess of this realm, under a geasa to always wear a veil outdoors lest she marries the first man she sets eyes on, sees the bull and notices it is a king's son. They marry, and the speckled bull, under a geas, chooses to be a bull by day and man by night. The bull regains human form and rescues his mother.[172]

In Types of the Irish Folktale (1963), by the same author, he listed a variant titled Uisce an Óir, Crann an Cheoil agus Éan na Scéalaíochta.[173]

Scotland

As a parallel to the Irish tale An Triúr Páiste Agus A Dtrí Réalta, published in Béaloideas, J. G McKay commented that the motif of the replacement of the newborns for animals occurs "in innumerable Scottish tales.".[174]

Research Sheila Douglas collected from teller John Stewart, from Perthshire, two variants: The Speaking Bird of Paradise and Cats, Dogs, and Blocks. In both of them, a king and a queen have three children (two boys and a girl), in three consecutive pregnancies, who are taken from them by the housekeeper and abandoned in the woods. Years later, a helpful kind woman tells them about their royal heritage, and advises them to seek the Speaking Bird of Paradise, which will help them reveal the truth to their parents.[175]

Wales

In a Welsh-Romani variant, Ī Tārnī Čikalī ("The Little Slut"), the protagonist is a Cinderella-like character who is humiliated by her sisters, but triumphs in the end. However, in the second part of the story, she gives birth to three children (a girl first, and two boys later) "girt with golden belts". They children are replaced for animals and taken to the forest. Their mother is accused of imaginary crimes and sentenced to be killed, but the old woman helper (who gave her the slippers) turns her into a sow, and tells her she may be killed and her liver taken by the hunters, by she will prevail in the end. The sow meets the children in the forest. The sow is killed, but, as the old woman prophecizes, her liver gained magical powers and her children use it to suit their needs. A neighbouring king wants the golden belts, but once they are taken from the boys, they become swans in the river. Their sister goes to the liver and wishes for their return to human form, as well as to get her mother back. The magical powers of the liver grant her wishes.[176][177]

Mediterranean Area

Greece

Albania

Auguste Dozon collected another version in his Contes Albanais with the title Les Soeurs Jaleuses (or "The Envious Sisters").[178][179] In this version, after their father, the previous king, dies, three sisters talk at night - an event eavesdropped by the newly-crowned king. The third sister promises to give birth to twins, a boy and a girl with "with a star on the brow and a moon on the breast". Dozon noted that it was a variant of the story published by von Hahn.[180]

Dozon's tale was also translated into German by linguist August Leskien in his book of Balkan folktales, with the title Die neidischen Schwestern.[181] In his commentaries, Leskien noted that the tale was classified as type 707, according to the then recent Antti Aarne's index (published in 1910).[182]

Robert Elsie, German scholar of Albanian studies, translated the same version in his book Albanian Folktales and Legends. In his translation, titled The youth and the maiden with stars on their foreheads and crescents on their breasts, the third sister, daughter of the recently deceased previous king, promises to give birth to twins, a boy and a girl "with stars on their foreheads and crescents on their breast".[183] The original name of the tale, in Albanian, as provided by Elsie, was "Djali dhe vajza me yll në ball dhe hënëz në kraharuar".[184]

Slavicist André Mazon (fr), in his study on Balkan folklore, published an Albanian language variant he titled Les Trois Soeurs. In this variant, the third sister promises to give birth to a boy with a moon on his breast and a girl with a star on the front. Despite lacking the quest for the items, Mazon recognized its correspondence to other tales, such as Russian "Tsar Saltan" and MMe. d'Aulnoy's "Belle-Étoile".[185]

Folklorist Anton Berisha published another Albanian language tale, titled "Djali dhe vajza me yll në ballë".[186]

Malta

German linguist Hans Stumme collected a Maltese variant he translated as Sonne und Mond ("Sun and Moon"), in Maltesische Märchen (1904).[187] This tale begins with the ATU 707 (twins born with astronomical motifs/aspects), but the story continues under the ATU 706 tale-type (The Maiden without hands): mother has her hands chopped off and abandoned with her children in the forest.

Bertha Ilg-Kössler published another Maltese tale titled Sonne und Mond, das tanzende Wasser und der singende Vogel ("Sun and Moon, the dancing water and the singing bird"). In this version, the third sister gives birth to a girl named Sun, and a boy named Moon.[188]

Cyprus

At least one variant from Cyprus has been published, from the "Folklore Archive of the Cyprus Research Centre".[189]

Western and Central Europe

In a variant collected in Austria, by Ignaz and Joseph Zingerle (Der Vogel Phönix, das Wasser des Lebens und die Wunderblume, or "The Phoenix Bird, the Water of Life and the Most beautiful Flower"),[190] the tale acquires complex features, mixing with motifs of ATU "the Fox as helper" and "The Grateful Dead": The twins take refuge in their (unbeknownst to them) father's house, it's their aunt herself who asks for the items, and the fox who helps the hero is his mother.[191] The fox animal is present in stories of the Puss in Boots type, or in the quest for The Golden Bird/Firebird (ATU 550 – Bird, Horse and Princess) or The Water of Life (ATU 551 – The Water of Life), where the fox replaces a wolf who helps the hero/prince.[192]

A variant from Buchelsdorf, when it was still part of Austrian Silesia (Der klingende Baum), has the twins raised as the gardener's sons and the quest for the water-tree-bird happens to improve the king's garden.[193]

In a Lovari Romani variant, the king meets the third sister during a dance at the village, who promised to give birth to a golden boy. They marry. Whenever a child is born to her (two golden boys and a golden girl, in three consecutive births), they are replaced for an animal and cast into the water. The king banishes his wife and orders her to be walled up, her eyes to be put on her forehead and to be spat on by passersby. An elderly fisherman and his wife rescue the children and name them Ējfēlke (Midnight), Hajnalka (Dawn) - for the time of day when the boys were saved - and Julishka for the girl. They discover they are adopted and their foster parents suggest they climb a "cut-glass mountain" for a bird that knows many things, and may reveal the origin of the parentage. At the end of their quest, young Julishka fetches the bird, of a "rusty old" appearance, and brings it home. With the bird's feathers, she and her brothers restore their mother to perfect health and disenchant the bird to human form. Julishka marries the now human bird.[194]

Germany

Portuguese folklorist Teófilo Braga, in his annotations, commented that the tale can be found in many Germanic sources,[195] mostly in the works of contemporary folklorists and tale collectors: The Three Little Birds (De drei Vügelkens), by the Brothers Grimm in their Kinder- und Hausmärchen (number 96);[196][197] Springendes Wasser, sprechender Vogel, singender Baum ("Leaping Water, Speaking Bird and Singing Tree"), written down by Heinrich Pröhle in Kinder- und Völksmärchen,[198][199] Die Drei Königskinder, by Johann Wilhelm Wolf (1845); Der Prinz mit den 7 Sternen ("The Prince with 7 stars"), collected in Waldeck by Louis Curtze,[200] Drei Königskinder ("Three King's Children"), a variant from Hanover collected by Wilhelm Busch;[201] and Der wahrredende Vogel ("The truth-speaking bird"), an even earlier written source, by Justus Heinrich Saal, in 1767.[109] A peculiar tale from Germany, Die grüne Junfer ("The Green Virgin"), by August Ey, mixes the ATU 710 tale type ("Mary's Child"), with the motif of the wonder children: three sons, one born with golden hair, other with a golden star on his chest and the third born with a golden stag on his chest.[202]

A variant where it is the middle child the hero who obtains the magical objects is The Talking Bird, the Singing Tree, and the Sparkling Stream (Der redende Vogel, der singende Baum und die goldgelbe Quelle), published in the newly discovered collection of Bavarian folk and fairy tales of Franz Xaver von Schönwerth.[203] In a second variant of the same collection (The Mark of the Dog, Pig and Cat), each children is born with a mark in the shape of the animal that was put in their place, at the moment of their birth.[204]

In a Sorbian/Wendish (Lausitz) variant, Der Sternprinz ("The Star Prince"), three discharged soldier brothers gather at a tavern to talk about their dreams. The first two dreamt of extraordinary objects: a large magical chain and an inexhaustible purse. The third soldier says he dreamt that if he marries the princess, they will have a son with a golden star on the forehead ("słoćanu gwězdu na cole"). The three men go to the king and the third marries the princess, who gives birth to the promised boy. However, the child is replaced by a dog and thrown in the water, but he is saved by a fisherman. Years later, on a hunt, the Star Prince tries to shoot a white hind, but it says it is the enchanted Queen of Rosenthal. She alerts that his father and uncles are in the dungeon and his mother is to marry another person. She also warns that he must promise not reveal her name. He stops the wedding and releases his uncles. They celebrate their family reunion, during which the Star Prince reveals the Queen's name. She departs and he must go on a quest after her (tale type ATU 400, "The Quest for the Lost Wife").[205][206]

Belgium

Professor Maurits de Meyere listed three variants under the banner "L'oiseau qui parle, l'arbre qui chante et l'eau merveilleuse", attested in Flanders fairy tale collections, in Belgium, all with contamination from other tale types (two with ATU 303, "The Twins or Blood Brothers", and one with tale type ATU 304, "The Dangerous Night-Watch").[207]

A variant titled La fille du marchand was collected by Emile Dantinne from the Huy region ("Vallée du Hoyoux"), in Wallonia.[208]

Switzerland

In a version collected from Graubünden with the title Igl utschi, che di la verdat or Vom Vöglein, das die Wahrheit erzählt ("The little bird that told the truth"), the tale begins in media res, with the box with the children being found by the miller and his wife. When the siblings grow up, they seek the bird of truth to learn their origins, and discover their uncle had tried to get rid of them.[209][210][211]

Another variant from Oberwallis (canton of Valais) (Die Sternkinder) has been collected by Johannes Jegerlehner, in his Walliser sagen.[212]

In a variant from Surselva, Ils treis lufts or Die drei Köhler ("The Three Charcoal-Burners"), three men meet in a pub to talk about their dreams. The first dreamt that he found seven gold coins under his pillow, and it came true. The second, that he found a golden chain, which also came true. The third, that he had a son with a golden star on the forehead. The king learns of their dreams and is gifted the golden chain. He marries his daughter to the third charcoal burner and she gives birth to the boy with a golden star. However, the queen replaces her grandson with a puppy and throws the child in the river.[213][214]

Hungary

Iceland

One version collected in Iceland was published by Ján Árnuson in his book Íslenzkar þjóðsögur og æfintýri (1864), with the title Bóndadæturnar. This tale has been variously translated in the following years: as "The Story of The Farmer's Three Daughters", in Icelandic Legends (1866); as Die Bauerntöchter in Isländische Märchen (1884)[215] or as Die neidischen Schwestern in Die neuisländischen Volksmärchen (1902), by Adeline Rittershaus.[216] The same tale was given a literary treatment and titled The Three Peasant Maidens in Icelandic Fairy Tales, by Angus W. Hall.[217]

Denmark

Danish author Evald Tang Kristensen published some Danish variants in his lifetime. In the first tale, collected from a Jens Povlsen, from Tværmose with the title Det springende Vand og det spillende Træ og den talende Fugl ("The leaping water and the playing tree and the talking bird"), a king gets lost in the woods and stays the night in a house in the woods where three sisters live. They each tell one another their marriage plans, the third saying she wants to marry the king. The king overhears their conversation, marries the third sister and she gives birth to two boys and a girl, in three consecutive years. In this tale, the two sisters replace the children for animals.[218]

In a second tale by Kristensen, collected from the wife of a man named Niels Pedersen, in Vejlby, with the title Den talende fugl, det syngende træ og det guldgule springvand ("The Talking Bird, the Singing Tree and the Golden-Yellow Fountain"), a king goes to war and leaves his wife to the care of his mother, who replaces her three grandchildren for animals.[219]

In a third tale by Kristensen, collected from teller Ane Nielsen, in Lisbjærg Terp, with the title Den lille prins med guldstjærne på brystet ("The little prince with the golden star on the chest"), three princely brothers go on a journey and tell each other last night's dreams, the third tells he dreamt that he married a princess and that they had a son with a golden star on the chest. His two brothers try to kill him, but spare his life, as long as he works as their servant. The trio reaches another kingdom, whose princess falls in love with the third brother. She marries him and gives birth to a boy with a golden star. The boy's uncles bribe the widwife to cast the boy in the water to die, but the child is saved. Years later, the boy becomes a youth, works for a witch and marries her daughter. When he goes to his grandfather's palace with his wife, a parrot at the entrance announces the presence of "the prince with the golden star on his chest".[220] Kristensen published a fourth tale with the title Den talende Fugl og det syngende Trae og det springende Vand ("The Talking Bird, the Singing Tree and the Leaping Water").[221]

The Danish language magazine Skattegraveren published a tale provided by Jens Madsen, in Höjet, with the title Det rindende træ den syngende fugl og det gule vand ("The Flowing Tree, the Singing Bird and the Golden Water"), wherein the siblings (two brothers and a sister) seek the three treasures to embellish their castle, per the suggestion of a beggar.[222] Another edition published a second tale, with the title Det glimrende vandspring, det spillende træ og den talende fugl ("The glistening water fountain, the playing tree and the talking bird"), that follows the usual story: three sisters, abandonment of children, quest for three treasures.[223]

According to Bengt Holbek's Interpretation of Fairy Tales, Denmark registers at least four other variants of type 707: Livsens Vand ("The Water of Life"); Den talende fugl og det syngende trae ("The Talking Bird and the Singing Tree"), and two homonymous tales with the title Den Talende Fugl ("The Talking Bird").[224]

Sweden

Tale type 707 in known in Sweden as Tre systrar vill ha kungen ("Three sisters want to marry the king").[225] A variant was collected by author and folklore researcher Eva Wigström (sv) with the title Det gyllene trädet, den sjungande floden och den talande fågeln ("The Golden Tree, the Singing River and the Talking Bird").[226]

Other versions have been recorded from Swedish sources:[154] Historie om Talande fogeln, spelande trädet och rinnande wattukällan (or vatukällan);[227] another Scandinavian variant, Om i éin kung in England, from Sjundeå.[228]

Finland

Karelia

In a Karelian tale, "Девять золотых сыновей" ("Nine Golden Sons"), the third sister promises to give birth to "three times three" children, their arms of gold up to the elbow, the legs of silver up to the knees, a moon on the temples, a sun on the front and stars in their hair. The king overhears their conversation and takes the woman as his wife. On their way, they meet a woman named Syöjätär, who insists to be the future queen's midwife. She gives birth to triplets in three consecutive pregnancies, but Syöjätär replaces them for rats, crows and puppies. The queen saves one of her children and is cast into a sea in a barrel. The remaining son asks his mother to bake bread with her breastmilk to rescue his brothers.[229][230]

Zaonezh'ya

Veps people

Baltic Region

Latvia

The work of Latvian folklorist Peteris Šmidts, beginning with Latviešu pasakas un teikas ("Latvian folktales and fables") (1925–1937), records 33 variants of the tale type. Its name in Latvian sources is Trīs brīnuma dēli or Brīnuma dēli.

According to the Latvian Folktale Catalogue, tale type 707, "The Three Golden Children", is known in Latvia as Brīnuma bērni ("Wonderful Children"), comprising 4 different redactions. Its second redaction is the one that follows the siblings' quest for the treasures (a tree that plays music, a bird that speaks and the water of life).[231]

Estonia

Lithuania

The tale type is known in Lithuanian compilations as Trys nepaprasti kūdikiai,[232] Nepaprasti vaikai[233] or Trys auksiniai sûnûs.

Lithuanian folklorist Jonas Balys (lt) published in 1936 an analysis of Lithuanian folktales, citing 65 variants available until then. In his tabulation, he noted that the third sister promised children with astronomical birthmarks, and, years later, her children seek a talking bird, a singing tree and the water of life.[232]

According to professor Bronislava Kerbelyte, the tale type is reported to register 244 (two hundred and forty-four) Lithuanian variants, under the banner Three Extraordinary Babies, with and without contamination from other tale types.[234] However, only 34 variants in Lithuania contain the quest for the bird that talks and reveals the truth, alongside a singing tree.[235]

Jonas Basanavicius collected a few variants in Lithuanian compilations, including the formats The Boys with the Golden Stars and Tale of Tsar Saltan.

German professor Karl Plenzat (de) tabulated and classified two Lithuanian variants, originally collected in German: Goldhärchen und Goldsternchen ("Little Golden-Hair and Little Golden Star"). In both stories, the queen replaces her twin grandchildren (a boy and a girl) for animals. When she learns they survived, she sends them after magical items from a garden of wonders: little bells, a little fish and the bird of truth.[236]

In a variant published by Fr. Richter in Zeitschrift für Volkskunde with the title Die drei Wünsche ("The Three Wishes"), three sisters spend an evening talking and weaving, the youngest saying she would like to have a son, bravest of all and loyal to the king. The king appears, takes the sisters and marries the youngest. Her son is born and grows up exceptionally fast, to the king's surprise. One day, he goes to war and sends a letter to his wife to send their son to the battlefield. The queen's jealous sisters intercept the letter and send him a frog dresses in fine clothes. The king is enraged and sends a written order to cast his wife in the water. The sisters throw her in the sea in a barrel with her son, but they wash ashore in an island. The prince saves a hare from a fox. The prince asks the hare about recent events. Later, the hare is disenchanted into a princess with golden eyes and silver hair, who marries the prince.[237]

Romania

Professor Moses Gaster collected and published a Romani tale from Romania, titled Ăl Rakle Summakune ("The Golden Children"). In this tale, the prince is looking for a wife, and sees three sisters on his father's courtyard. The youngest promises to give birth to "two golden children, with silver teeth and golden hair, and two apples in their hands all golden". The sisters beg the midwife to substitute the twins, a boy and a girl, for puppies and throw them in the water. Years later, the midwife sends them for the "Snake's crown", the fairy maiden Ileana Simziana, the Talking Bird and the Singing Tree. The collector noted that the fairy maiden Ileana was the one to rescue the Brother, instead of the Sister.[238]

In another Romanian variant, A két aranyhajú gyermek ("The Two Children With Golden Hair"), the youngest sister promises the king to give birth to a boy and a girl of unparalleled beauty. Her sisters, seething with envy, conspire with the king's gypsy servant, take the children and bury them in the garden. After the twins are reborn as trees, they twist their branches to make shade for the king when he passes, and to hit their aunts when they pass. After they go through the rebirth cycle, the Sun, stunned at their beauty, clothes them and gives the boy a flute.[239]

Russia and Eastern Europe

Slavicist Karel Horálek published an article with an overall analysis of the ATU 707 type in Slavic sources.[240] Further scholarship established subtypes of the AT 707 tale type in the Slavic-speaking world: AT 707A*, AT 707B* and AT 707C*.[241]

Russia

Eastern Europe

In an Eastern European variant, The Golden Fish, The Wonder-working Tree and the Golden Bird, the siblings are twins and their grandmother, the old queen, is the villain. Their father, Prince Yarboi, met their mother and her sisters when they were cutting grass on a hot summer day. The sisters commented that their fates were foretold, and the youngest revealed she was destined to marry the prince and bear the wonder twins. This variant was first collected by Josef Košín z Radostova, in Národní Pohádky, Volume III, in 1856, with the title O princovi se zlatým sluncem a o princezně se zlatým měsícem na prsou ("The prince with the golden sun and the princess with the golden moon on her breast").[242][243] However, the tale was translated by Jeremiah Curtin and published in Fairy Tales of Eastern Europe, as a Hungarian story.[244]

In the South Slavic tale Die böse Schwiegermutter, also collected by Friedrich Salomon Krauss, the mother gives birth to triplets: male twins with golden hands and a girl with a golden star on her forehead. Years later, they search for the green water, the speaking bird and the singing tree.[245]

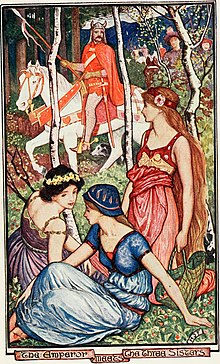

In another South Slavic fairy tale, Die Mär von den drei wunderbaren Schwestern ("The Fairy Tale of the Three Wonderful Sisters"), the emperor spies three sisters talking, the youngest saying that she will give birth to twins with green eyes and golden hair, the boy will cry diamonds instead of tears and the girl will produce rose petals when she smiles. The emperor marries the youngest, she gives birth to the twins and they are replaced by puppies. The twins are saved by a miller. Years later, they hire builders with the boy's diamond tears and erect a palace. Their aunts send him after a wild Divenross, a golden branch that can talk, and a woman of great beauty named Pendel Hanuma. Pendel Hanuma marries the Brother and reveals the whole plot to the Emperor.[246]

Belarus

Ukraine

Slovakia

According to professor Viera Gaspariková, professor Frank Wollman (cs)'s fieldwork in Slovakia collected 9 variants of tale type Děti nevinné upodozrievanej matky[247] or The Children of an Innocently Suspected Mother.[248]

In a Slovak variant, Zlatovlasé dvojčatá ("The Golden-Haired Twins"), the prince marries the youngest sister, who promises to give birth to twins with golden hair and a star on their breast. When the time comes, a woman named Striga steals the newly-born infants and casts them out in the water. The boy and girl are soon found and given the name Janík and Ludmilka. Years later, the Striga sets the boy on the quest for the golden pear and the woman named Drndrlienka as a companion for his sister.[249] Scholar Jiří Polívka listed another version of this story, both grouped under his own classification "Deti nevinne vyhnatej matky" ("Sons of an Innocent Exiled Maiden").[250]

Polívka mentioned the existence of a Slovak variant titled Stromčok, Voďička, Ptáčik ("Tree, Water, Bird"), reported to be part of a Slovak collection named Codexy Revúcke ("Codices of Revúca").[251] He found two other tales, O stromčoku, čo všetko krási, ptáčiku, čo všetko oživuje, a o vodičke, čo všetko zná and Zlatý vták a zlatá voda ("Golden Bird and Golden Water").[252]

Polivka identified a tale of the Boys With the Golden Stars format, which he then named Pani s chlapci zakopaná do hnojiska. Slncová matka im pomáha ("Maiden and sons buried in manure; the Sun's Mother helps them"). In this tale, O jednom zlatom orechu ("About a golden nut"), a wife gives birth to twins while her husband is at war. A witch sews the boys in an oxen hide and buries it in a pit of manure. Out of the pit springs a nut tree. The witch orders the trees to be made into beds and for the beds to be burnt to cinders. Sparks fly out of the pyre and reach a rose bush, eaten by a goat who gives birth to two kids. The animals are killed and they regain human form. The Sun, on his daily journey, sees the twins and, impressed by their beauty, tells his mother. The Sun's mother comes to them with clothes and a golden apple.[253]

Poland

The tale type is known in Poland with the name Trzej synowie z gwiazdą na skroni ("Three Sons With Stars on the Temple").[254]

A version from Poland has been collected by Antoni Józef Glinski, titled O królewiczu z księżycem na czole, z gwiazdami po głowie[255] and translated into German with the name Vom Prinzen mit dem Mond auf der Stirn und Sternen auf dem Kopf (English: "The Princes with the Moon on the Forehead and Stars on the Head").[256]

Polish ethnographer Stanisław Ciszewski (pl) collected two variants, one from Maszków, titled O grającem drzewie, złotej wodzie i gadającym ptaku ("The Music-Playing Tree, the Golden Water and the Speaking Bird"),[257] and another from Skała, named O śpiewającem drzewie, złotej wodzie i gadającym ptaku ("The Singing Tree, the Golden Water and the Speaking Bird").[258]

In a tale from Szląsku, O dwóch dzieciątkach na wodę puszczonych ("About two children cast into the water"), three sisters tell one another their dreams, the youngest promising to bear twin children to the king: a boy, after being washed, his bathwater will turn to gold, and a girl, flowers will bloom with every smile and pearls will fall when she cries. The king takes them to his presence and marries the third sister, but as soon as the twins are born, they are cast into the water. They are saved and raised by an old man. The twins tell him that saw in a dream a place with a fountain, a tree that sings and a bird that talks. The Brother fails, the Sister prevails, gets the treasures and saves her twin. The bird tells them to invite the king for a feast and reveals the whole truth.[259]

Polish folklorist Oskar Kolberg collected a variant from Tarnow with the title O królewnie i dwunastu jej synach ("About the queen and her twelve children"): three sisters are stranded on a beach when the king pass by them, each promising to feed an army with little wheat, to clothe an army with little yarn and to bear 12 children with a moon on the forehead and a bright dawn on the back of the neck. She gives birth to her fabled children, but she is tossed in a barrel with her twelfth son into the sea. They wash ashore on an island. Her son goes to a place to rescue his eleven brothers and reunited the family. When the king, their father, decides to hold a ball in the palace, they decide to infiltrate the celebrations to tell their story.[260]

Czech Republic

Author Božena Němcová published a Czech tale titled O mluvícím ptáku, živé vodě a třech zlatých jabloních ("The speaking bird, the water of life and the three golden apples"): three poor sisters, Marketka, Terezka and Johanka discuss among themselves their future husbands. The king overhears their conversation and summons them to his presence, and fulfills Johanka's wishes. Each time a child is born (three in total), the envious sisters cast the babies in the water, but they are carried by the stream to another kingdom. The second king adopts the babies and names them Jaromír, Jaroslav and Růženka.[261][262]