2010 Winter Olympics

| Part of a series on |

| 2010 Winter Olympics |

|---|

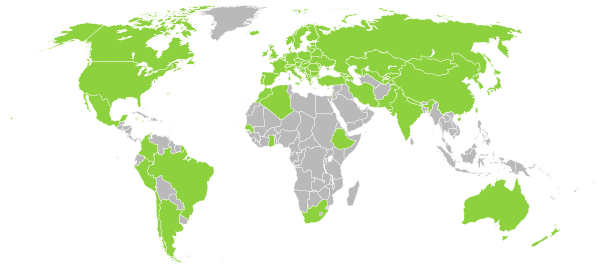

The 2010 Winter Olympics, officially the XXI Olympic Winter Games or the 21st Winter Olympics, were a major international multi-sport event held on February 12–28, 2010, in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, with some events held in the suburbs of Richmond, West Vancouver and the University Endowment Lands, and in the resort town of Whistler. Approximately 2,600 athletes from 82 nations participated in 86 events in fifteen disciplines. Both the Olympic and Paralympic Games were being organized by the Vancouver Organizing Committee (VANOC). The 2010 Winter Olympics were the third Olympics hosted by Canada, and the first by the province of British Columbia. Previously, Canada hosted the 1976 Summer Olympics in Montreal, Quebec and the 1988 Winter Olympics in Calgary, Alberta.

Following Olympic tradition, the then-current Vancouver mayor, Sam Sullivan, received the Olympic flag during the closing ceremony of the 2006 Winter Olympics in Turin, Italy. The flag was raised on February 28, 2006, in a special ceremony and was on display at Vancouver City Hall until the Olympic opening ceremony. The event was officially opened by Governor General Michaëlle Jean.[2]

For the first time, Canada won gold at an Olympic Games hosted at home in an "official" sport, having failed to do so at both the 1976 Summer Olympics in Montreal and the 1988 Winter Olympics in Calgary, although Canada won a gold medal in the "demonstration-sport" of curling in Calgary. Canada clinched first overall in gold medal wins on the second to last day of competition[3] and became the first host nation since Norway in 1952 to lead the gold medal count. With 14, Canada broke the record for the most gold medals won at a single Winter Olympics, which was 13, set by the former Soviet Union in 1976 and Norway in 2002.[4] The United States won the most medals in total, their second time doing so at the Winter Olympics, and broke the record for the most medals won at a single Winter Olympics, with 37, which was held by Germany in 2002 at 36 medals.[3] Athletes from Slovakia[5] and Belarus[6] won the first Winter Olympic gold medals for their nations.

Bid and preparations

| 2010 Winter Olympics bidding results | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| City | Nation | Round 1 | Round 2 | ||

| Vancouver | 40 | 56 | |||

| Pyeongchang | 51 | 53 | |||

| Salzburg | 16 | — | |||

The Canadian Olympic Association chose Vancouver as the Canadian candidate city over Calgary, which sought to re-host the Games and Quebec City, which had lost the 2002 Olympic bid in 1995. On the first round of voting on November 21, 1998, Vancouver-Whistler had 26 votes, Quebec City with 25 and Calgary 21. On December 3, 1998, the second and final round of voting occurred between the two leading contenders, which saw Vancouver win with 40 votes compared to Quebec City's 32.

After the bid bribing scandal over the candidacy of the Salt Lake City bid for the 2002 Winter Olympics (which resulted in Quebec City asking for compensation (C$8 million) for its unsuccessful bid),[7] many of the rules of the bidding process were changed in 1999. The IOC created the Evaluation Commission, which was appointed on October 24, 2002. Prior to the bidding for the 2008 Summer Olympics, often host cities would fly members of the IOC to their city where they toured the city and were provided with gifts. The lack of oversight and transparency often led to allegations of money for votes. Afterwards, changes brought forth by the IOC bidding rules were tightened, and more focused on technical aspects of candidate cities. The team analyzed the candidate city features and provided its input back to the IOC.

Vancouver won the bidding process to host the Olympics by a vote of the International Olympic Committee on July 2, 2003, at the 115th IOC Session held in Prague, Czech Republic. The result was announced by IOC President Jacques Rogge.[8] Vancouver faced two other finalists shortlisted that same February: Pyeongchang, South Korea, and Salzburg, Austria. Pyeongchang had the most votes of the three cities in the first round of voting, in which Salzburg was eliminated. In the run-off, all but two of the members who had voted for Salzburg voted for Vancouver. It was the closest vote by the IOC since Sydney, Australia beat Beijing for the 2000 Summer Olympics by two votes. Vancouver's victory came almost two years after Toronto's 2008 Summer Olympic bid was defeated by Beijing in a landslide vote.

The Vancouver Olympic Committee (VANOC) spent $16.6 million on upgrading facilities at Cypress Mountain, which hosts the freestyle (aerials, moguls, ski cross) and snowboarding events. With the opening in February 2009 of the $40 million Vancouver Olympic/Paralympic Centre at Hillcrest Park which hosts curling, every sports venue for the 2010 Games was completed on time and at least one year prior to the Games.[9][10]

Cost estimates and overruns

Operations

In 2004, the operational cost of the 2010 Winter Olympics was estimated to be Canadian $1.354 billion (USD $1,314,307,896). As of mid-2009 it was projected to be $1.76 billion,[11][better source needed] all raised from non-government sources,[citation needed] primarily through sponsorships and the auction of national broadcasting rights. $580 million was the taxpayer-supported budget to construct or renovate venues throughout Vancouver and Whistler,

Security

$200 million was expected to be spent for security, which was organized through a special body, the Integrated Security Unit, of which the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) was the lead agency; other government agencies such as the Vancouver Police, Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS), the Canadian Forces, police from other cities, and the Canada Border Services Agency also played a role. That number was later revealed to be in the region of $1 billion, an amount in excess of five times what was originally estimated.[12] As of the start of February 2010, the total cost of the Games, including all the infrastructure improvements for the region that occurred was estimated to be $6 billion, with $600 million of the spending directly related to hosting the Games.

Estimated revenues

Projected benefits and revenues to the city and province were projected to be in the range of $10 billion by some sources, though a Price-Waterhouse report indicating that the projected direct revenues would be in the range of $1 billion.[13][better source needed]

Venues

Some venues, including the Richmond Olympic Oval, were at sea level, a rarity for the Winter Games.[citation needed] The 2010 Games were also the first—Winter or Summer—to have had an Opening Ceremony held indoors.[citation needed] Vancouver was the most populous city ever to hold the Winter Games.[14] In February, the month when the Games were held, Vancouver has an average temperature of 4.8 °C (40.6 °F).[15] Indeed, the average temperature as measured at Vancouver International Airport was 7.1 °C (44.8 °F) for the month of February 2010.[16]

The opening and closing ceremonies were held at BC Place Stadium, which received over $150 million in major renovations. Competition venues in Greater Vancouver included the Pacific Coliseum, the Vancouver Olympic/Paralympic Centre, the UBC Winter Sports Centre, the Richmond Olympic Oval and Cypress Mountain. GM Place, home of the NHL's Vancouver Canucks, played host to ice hockey events, but because corporate sponsorship is not allowed for an Olympic venue, it was renamed Canada Hockey Place for the duration of the Games.[17] Renovations included the removal of advertising from the ice surface and conversion of some seating to accommodate the media.[17] The 2010 Winter Olympics marked the first time an Olympic hockey game was played on a rink sized according to NHL rules instead of international specifications. Competition venues in Whistler included the Whistler Blackcomb ski resort, the Whistler Olympic Park and the Whistler Sliding Centre.

The 2010 Winter Games marked the first time that the energy consumption of the Olympic venues was tracked in real time and available to the public. Energy data was collected from the metering and building automation systems of nine of the Olympic venues and was displayed online through the Venue Energy Tracker project.[18]

Marketing

Leo Obstbaum (1969–2009), the late director of design for the 2010 Winter Olympics, oversaw and designed many of the main symbols of the Games, including the mascots, medals and the design of the Olympic torches.[19]

The 2010 Winter Olympics logo was unveiled on April 23, 2005, and is named Ilanaaq the Inunnguaq. Ilanaaq is the Inuktitut word for friend. The logo was based on the Inukshuk (stone landmark or cairn) built for the Northwest Territories Pavilion at Expo 86 and donated to the City of Vancouver after the event. It is now used as a landmark on English Bay Beach.

The mascots for the 2010 Winter Olympic and Paralympic Games were introduced on November 27, 2007.[20] Inspired by traditional First Nations creatures, the mascots include:

- Miga — A mythical sea bear, part orca and part kermode bear.

- Quatchi — A sasquatch, who wears boots and earmuffs.

- Sumi — An animal guardian spirit who wears the hat of the orca whale, flies with the wings of the mighty Thunderbird and runs on the strong furry legs of the black bear.

- Mukmuk — A Vancouver Island marmot.

Miga and Quatchi were mascots for the Olympic Games, while Sumi was the mascot for the Paralympic Games. Mukmuk is considered a sidekick, not a full mascot.

The Royal Canadian Mint is producing a series of commemorative coins celebrating the 2010 Games,[21] and in partnership with CTV is also allowing users to vote on the Top 10 Canadian Olympic Winter Moments; where designs honouring the top three will be added to the series of coins.[22]

Canada Post released many stamps to commemorate the Vancouver Games including, one for each of the mascots and one to celebrate the first Gold won on Canadian soil. Many countries' postal services have also released stamps, such as the US[23], Germany[24], Australia[25], Austria[26], Belarus[27], Croatia[28], Czech Republic[29], Estonia[30], France[31], Italy[32], Liechtenstein[33], Lithuania[34], Poland[35], Switzerland[36], Turkey[37] and Uzbekistan[38].

Two official video games have been released to commemorate the Games: Mario and Sonic at the Olympic Winter Games was released for Wii and Nintendo DS in October 2009, while Vancouver 2010 was released in January 2010 for Xbox 360, Windows and PlayStation 3. The official theme songs for the 2010 Winter Games used by the Canada's Olympic Broadcast Media Consortium (commonly known as CTV Olympics) were "I Believe" performed by Nikki Yanofsky and "J'imagine" performed by Annie Villeneuve.

Three albums, Canada's Hockey Anthems: Sounds of the Vancouver 2010 Winter Olympic Games, Sounds of Vancouver 2010: Opening Ceremony Commemorative Album, and Sounds of Vancouver 2010: Closing Ceremony Commemorative Album were released to accompany the Games.[39]

Media coverage

The Olympic Games in Vancouver were broadcast worldwide by a number of television broadcasters. As rights for the 2010 Games have been packaged with those for the 2012 Summer Olympics, broadcasters will be largely identical for both events.

The host broadcaster was Olympic Broadcasting Services Vancouver, a subsidiary of the IOC's new in-house broadcasting unit Olympic Broadcasting Services (OBS). The 2010 Olympics marked the first Games where the host broadcasting facilities were provided solely by OBS.[40] The executive director of Olympic Broadcasting Services Vancouver was Nancy Lee, a former producer and executive for CBC Sports.[41]

In Canada, the Games were the first Olympic Games broadcast by a new Olympic Broadcast Media Consortium led by CTVglobemedia and Rogers Media, displacing previous broadcaster CBC Sports. Main English-language coverage was shown on the CTV Television Network, while supplementary programming was mainly shown on TSN and Rogers Sportsnet.[42]

In the United States, Associated Press (AP) announced that it would send 120 reporters, photographers, editors and videographers to cover the Games on behalf of the country's news media.[43] The cost of their Olympics coverage prompted AP to make a "real departure for the wire service's online coverage". Rather than simply providing content, it partnered with more than 900 newspapers and broadcasters who split the ad revenue generated from an AP-produced multi-media package of video, photos, statistics, stories and a daily Webcast.[43] AP's coverage included a microsite with web widgets facilitating integration with social networking and bookmarking services.[44]

In France, the Games were covered by France Télévisions, which included continuous live coverage on its website.[45]

The official broadcast theme for the Olympic Broadcasting Services host broadcast was a piece called 'City Of Ice' composed by Rob May and Simon Hill.[46]

Torch relay

The Olympic Torch Relay is the transfer of the Olympic flame from Ancient Olympia, Greece — where the first Olympic Games were held thousands of years ago — to the stadium of the city hosting the current Olympic Games. The flame arrives just in time for the Opening Ceremony.

For the Vancouver 2010 Olympic Winter Games, the flame was lit in Olympia on October 22, 2009.[47] It then travelled from Greece, over the North Pole to Canada's High Arctic and on to the West Coast and Vancouver. The relay started its long Canada journey from the British Columbia capital of Victoria. In Canada, the torch travelled approximately 45,000 kilometres (28,000 mi) over 106 days, making it the longest relay route within one country in Olympic history. The Olympic Torch was carried by approximately 12,000 Canadians and reached over 1,000 communities.[48][49]

Celebrity torchbearers included Arnold Schwarzenegger,[50] Steve Nash,[51] Matt Lauer,[52] Justin Morneau,[53] Michael Bublé,[54] Bob Costas,[55] Shania Twain,[56] and hockey greats including Sidney Crosby,[57] Wayne Gretzky,[58] and the captains of the two Vancouver Canucks teams that went to the Stanley Cup Finals: Trevor Linden (1994)[59] and Stan Smyl (1982).[60]

The Games

Participating teams

82 National Olympic Committees entered teams in the 2010 Winter Olympics.[61] Cayman Islands, Colombia, Ghana, Montenegro, Pakistan, Peru and Serbia made their winter Olympic debuts. Also Jamaica, Mexico and Morocco returned to the Games after missing the Turin Games. Tonga sought to make its Winter Olympic debut by entering a single competitor in luge, attracting some media attention, but he crashed in the final round of qualifying.[62] Luxembourg qualified two athletes[63] but did not participate because one did not reach the criteria set by the NOC[64] and the other was injured[65] before the Games.

Albania (1)[63]

Albania (1)[63] Algeria (1)[63]

Algeria (1)[63] Andorra (6)[63]

Andorra (6)[63] Argentina (7)[63]

Argentina (7)[63] Armenia (4)[63]

Armenia (4)[63] Australia (40)[1]

Australia (40)[1] Austria (81)[66]

Austria (81)[66] Azerbaijan (2)[63]

Azerbaijan (2)[63] Belarus (50)[67][68]

Belarus (50)[67][68] Belgium (9)[69][70]

Belgium (9)[69][70] Bermuda (1)[1]

Bermuda (1)[1] Bosnia and Herzegovina (5)[63]

Bosnia and Herzegovina (5)[63] Brazil (5)[71]

Brazil (5)[71] Bulgaria (19)[72]

Bulgaria (19)[72] Canada (206)[67]

Canada (206)[67] Cayman Islands (1)[66][73]

Cayman Islands (1)[66][73] Chile (3)[1]

Chile (3)[1] China (90)[1]

China (90)[1] Colombia (1)

Colombia (1) Croatia (18)[1]

Croatia (18)[1] Cyprus (2)[63]

Cyprus (2)[63] Czech Republic (92)[1]

Czech Republic (92)[1] Denmark (18)[74]

Denmark (18)[74] Estonia (30)[1]

Estonia (30)[1] Ethiopia (1)[63]

Ethiopia (1)[63] Finland (95)[75]

Finland (95)[75] France (108)[76]

France (108)[76] Georgia (8*)[1] (*)

Georgia (8*)[1] (*)

| class="col-break " |

Germany (153)[1]

Germany (153)[1] Ghana (1)[77]

Ghana (1)[77] Great Britain (52)[1]

Great Britain (52)[1] Greece (7)[69][70]

Greece (7)[69][70] Hong Kong (1)[78]

Hong Kong (1)[78] Hungary (16)[1]

Hungary (16)[1] Iceland (4)[63]

Iceland (4)[63] India (3)[79]

India (3)[79] Iran (4)[1]

Iran (4)[1] Ireland (6)[63]

Ireland (6)[63] Israel (3)[69][70]

Israel (3)[69][70] Italy (109)[1]

Italy (109)[1] Jamaica (1)[1]

Jamaica (1)[1] Japan (94)[1]

Japan (94)[1] Kazakhstan (38)[1]

Kazakhstan (38)[1] North Korea (2)[80][81]

North Korea (2)[80][81] South Korea (46)[1]

South Korea (46)[1] Kyrgyzstan (2)[1]

Kyrgyzstan (2)[1] Latvia (59)[67]

Latvia (59)[67] Lebanon (3)[66]

Lebanon (3)[66] Liechtenstein (7)[66]

Liechtenstein (7)[66] Lithuania (8)[69][70]

Lithuania (8)[69][70] Macedonia (4)[63]

Macedonia (4)[63] Mexico (1)[63]

Mexico (1)[63] Moldova (7)[1]

Moldova (7)[1] Monaco (6)[1]

Monaco (6)[1] Mongolia (2)[82]

Mongolia (2)[82]

| class="col-break " |

Montenegro (1)[63]

Montenegro (1)[63] Morocco (1)[63]

Morocco (1)[63] Nepal (2)[63]

Nepal (2)[63] Netherlands (34)[83]

Netherlands (34)[83] New Zealand (16)[66]

New Zealand (16)[66] Norway (99)[84]

Norway (99)[84] Pakistan (1)[63]

Pakistan (1)[63] Peru (3)[63]

Peru (3)[63] Poland (50)[1][85]

Poland (50)[1][85] Portugal (1)[63]

Portugal (1)[63] Romania (29)[80][86]

Romania (29)[80][86] Russia (177)[1]

Russia (177)[1] San Marino (1)[63]

San Marino (1)[63] Senegal (1)[66]

Senegal (1)[66] Serbia (10)[1]

Serbia (10)[1] Slovakia (73)[67]

Slovakia (73)[67] Slovenia (50)[69][70][86]

Slovenia (50)[69][70][86] South Africa (2)[63]

South Africa (2)[63] Spain (18)[69][70]

Spain (18)[69][70] Sweden (106)[87]

Sweden (106)[87] Switzerland (146)[67]

Switzerland (146)[67] Chinese Taipei (1)[88]

Chinese Taipei (1)[88] Tajikistan (1)[1]

Tajikistan (1)[1] Turkey (5)[1]

Turkey (5)[1] Ukraine (47)[1]

Ukraine (47)[1] United States (215)[1]

United States (215)[1] Uzbekistan (3)[63]

Uzbekistan (3)[63]

|}

The following nations which competed at the previous Winter Games in Turin did not participate in Vancouver:

Sports

Fifteen winter sports events were part of the 2010 Winter Olympics. The eight sports categorized as ice sports were: bobsled, luge, skeleton, ice hockey, figure skating, speed skating, short track speed skating and curling. The three sports categorized as alpine skiing and snowboarding events were: alpine, freestyle and snowboarding. The four sports categorized as Nordic events were: biathlon, cross-country skiing, ski jumping and Nordic combined.

Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of medal events contested in each sport.

|

|

|

The opening and closing ceremonies and the events categorized as ice sports (excluding bobsleigh, luge and skeleton) were held in Vancouver and Richmond. The sports categorized as "Nordic events" were held in the Callaghan Valley located just to the west of Whistler. All alpine skiing events were held on Whistler Mountain (Creekside) and sliding events (bobsleigh, luge and skeleton) were held on Blackcomb Mountain. Cypress Mountain (located in Cypress Provincial Park in West Vancouver) hosted the freestyle skiing (aerials, moguls and ski cross), and all snowboard events (half-pipe, parallel giant slalom, snowboard cross).

Vancouver 2010 was also the first winter Olympics in which both men's and women's hockey were played on a narrower, NHL-sized ice rink,[89] measuring 200 ft × 85 ft (61 m × 26 m), instead of the international size of 200 ft × 98.5 ft (61 m × 30 m). The games were played at General Motors Place, home of the NHL's Vancouver Canucks, which was temporarily renamed Canada Hockey Place for the duration of the Olympics. This change saved $10 million in construction costs and allowed an additional 35,000 spectators to attend Olympic hockey games.[89] However, some European countries expressed concern over this decision, worried that it might give North American players an advantage since they grew up playing on the smaller NHL-sized rinks.[90]

There were a number of events that were proposed to be included in the 2010 Winter Olympics.[91] On November 28, 2006, the IOC Executive Board at their meeting in Kuwait voted to include ski cross in the official program.[92] The Vancouver Olympic Committee (VANOC) subsequently approved the event to be officially part of the Games program.[93]

Events proposed for inclusion but ultimately rejected included:[94]

- Biathlon mixed relay

- Mixed doubles curling

- Team alpine skiing

- Team bobsled and skeleton

- Team luge

- Women's ski jumping

The issue over women's ski jumping being excluded ended up in the Supreme Court of British Columbia in Vancouver during April 21–24, 2009, with a verdict on July 10 excluding women's ski jumping from the 2010 Games.[95] A request to appeal that verdict to the Supreme Court of Canada was subsequently denied on December 22 – a decision that marked the end of any hopes that the event would be held during Vancouver 2010.[96] To alleviate the exclusion, VANOC organizers invited women from all over Canada to participate at Whistler Olympic Park, including Continential Cup in January 2009.[95] There is now an effort to include women's ski jumping for the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi, Russia.[97]

Calendar

In the following calendar for the 2010 Winter Olympic Games, each blue box indicates that an event competition, such as a qualification round, was held on that day. The yellow boxes represent days during which medal-awarding finals for a sport were held. Each bullet in these boxes was an event final, the number of bullets per box representing the number of finals that were contested on that day.[98]

Template:2010 Winter Olympics Calendar

Medal table

The top ten listed NOCs by number of gold medals are listed below. The host nation, Canada, is highlighted.

| 1 | 14 | 7 | 5 | 26 | |

| 2 | 10 | 13 | 7 | 30 | |

| 3 | 9 | 15 | 13 | 37 | |

| 4 | 9 | 8 | 6 | 23 | |

| 5 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 14 | |

| 6 | 6 | 0 | 3 | 9 | |

| 7 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 11 | |

| 7 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 11 | |

| 9 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 16 | |

| 10 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 8 |

Concerns and controversies

Initial organized opposition to the games began in 2006 with the creation of No Games 2010[99][who?] as outlined in Chris Shaw's book Five Ring Circus published in 2008.[99][100] The book has been widely reviewed and has been a touchstone for critics of the Vancouver Games.[101][102][103] Before the Games began and as they commenced, a number of concerns and controversies surfaced and received media attention. Hours before the opening ceremony, Georgian luger Nodar Kumaritashvili was killed during a training run, intensifying questions about the safety of the course and prompting[citation needed] organizers to implement quick modifications. However, officials concluded that it was an athlete error rather than a track deficiency.[104] The International Luge Federation called an emergency meeting after the accident, and all other training runs were cancelled for the day.[105]

One critic questioned the choice of Cypress Mountain[106] as a venue because of its frequent lack of snow due to El Niño. Because of this possibility, organizers had a contingency plan to truck in snow from Manning Park, about 250 kilometres (160 mi) to the east of the city. This allowed events to proceed as planned.[107]

Political decisions involving cancellation of promised low-income housing and the creation of a community of mixed economic backgrounds for post-Games use of the athletes' village was criticized.[108] Opening ceremonies were stalled while organizers dealt with mechanical problems during the cauldron lighting ceremony.[109] Speed skating events were delayed due to breakdowns of the ice resurfacers supplied by Olympia, an official sponsor of the Games.[110]

Thousands of tickets were voided by organizers when weather made standing-room-only areas unsafe.[111] Visitors were also upset that, as in previous Olympics, medal ceremonies required separate admission[111] and that blocks of VIP tickets reserved for sponsors and dignitaries were unused at events.[112] Other glitches and complaints have included confusion by race officials at the start of the February 16 men's and women's biathlon pursuit races, and restricted access to the Olympic flame cauldron on the Vancouver waterfront.[113][114]

Opposition

Opposition to the Olympic Games was expressed by activists and politicians, including Lower Mainland mayors Derek Corrigan[115] and Richard Walton.[citation needed] Many of the public Olympic events held in Vancouver were attended by protesters.[116]

On Saturday, February 13, as part of a week-long Anti-Olympic Convergence, protesters smashed windows of the Downtown Vancouver location of The Bay department store.[117][118] Protesters later argued that the owner of The Bay, the Hudson's Bay Company, "has been a symbol of colonial oppression for centuries" as well as a major sponsor of the 2010 Olympics.[119]

There were several other reasons for the opposition, some of which are outlined in Helen Jefferson Lenskyj's books Olympic Industry Resistance (2007) and Inside the Olympic Industry (2000).[120] These issues include:

- Displacement of low-income residents.[121][122][123][124]

- anticipated human trafficking for the purpose of forced prostitution.[125][126][127]

Aboriginal opposition

Although the Aboriginal governments of the Squamish, Musqueam, Lil'wat and Tsleil-Waututh (the "Four Host First Nations"), on whose traditional territory the Games are being held, signed a protocol in 2004[128] in support of the games,[129] there was opposition to the Olympics from some indigenous groups and supporters. Although the Lil'wat branch of the St'at'imc Nation is a co-host of the Games, a splinter group from the Seton band known as the St’at’imc of Sutikalh, who have also opposed the Cayoosh Ski Resort, fear the Olympics will bring unwanted tourism and real estate sales to their territory.[130][131] Local aboriginal people, as well as Canadian Inuit, initially expressed concern over the choice of an inukshuk as the symbol of the Games, with some Inuit leaders such as former Nunavut Commissioner Peter Irniq stating that the inukshuk is a culturally important symbol to them. He said that the "Inuit never build inuksuit with head, legs and arms. I have seen inuksuit [built] more recently, 100 years maybe by non-Inuit in Nunavut, with head, legs and arms. These are not called inuksuit. These are called inunguat, imitation of man."[132] Local aboriginal groups also expressed annoyance that the design did not reflect the Coast Salish and Interior Salish native culture from the region the Games are being held in, but rather that of the Inuit, who are indigenous to the Arctic far from Vancouver.

Doping

On March 11, 2010, it was reported that the Polish cross country skier Kornelia Marek was tested positive for EPO by the Polish Olympic Committee. If found guilty of doping by the International Olympic Committee, Marek and the relay teams would be disqualified and stripped of their Vancouver results. She would also be banned from the next Winter Olympics in Sochi, Russia, in 2014.

Marek denied taking any banned substances, but the backup "B" sample from the Vancouver doping lab confirmed the "A" sample.[133]

Legacy

Despite concerns and opposition prior to the Games, the 2010 Winter Olympic Games were generally accepted by the world's media as a success in creating a positive atmosphere for athletic achievement.[134] The massive celebratory crowds in downtown Vancouver were highly praised by the IOC. Jacques Rogge, the president of IOC, indicated that "the way Vancouver embraced these Games was extraordinary. This is really something unique and has given a great atmosphere for these Games."[135][136] Only a very few members of the media criticized the celebrations as having been somewhat nationalistic, but the crowds were by and large friendly to all participants. These games have been called the best winter games since Turin. They are also mentioned alongside the Sydney Summer games in regards to the best atmosphere. A large part is credited to the citizens of Vancouver and Canada.[137]

Funding

Directly as a result of Canada's medal performance at the 2010 Olympics, the Government of Canada announced in the 2010 Federal Budget, a new commitment of $34 million over the next two years towards programs for athletes planning to compete in future Olympics.[138] This is in addition to the $11 million per year federal government commitment to the Own the Podium program.

Also, as a result of hosting the 2010 Olympics, the British Columbia government pledged to restore funding for sports programs and athlete development to 2008 levels, which amounts to $30 million over three years.[139]

See also

- 2010 Winter Paralympics

- Olympic Games held in Canada

- 1976 Summer Olympics – Montreal

- 1988 Winter Olympics – Calgary

- 2010 Winter Olympics – Vancouver

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab Vancouver Olympics – Athletes

- ^ a b "Gov. Gen. Jean to open 2010 Games: PM". Edmonton Sun. Canadian Press. 2009-06-27. Retrieved 2009-08-14.

- ^ a b "U.S. clinches medals mark, Canada ties gold record". Vancouver. Associated Press. 2010-02-27.

- ^ Canadian Press (2010-02-27). "Canada sets Olympic gold record". CBC Sports. Retrieved 2010-02-27.

- ^ "Anastazia Kuzmina wins Slovakia first winter crown". The Australian. 2010-02-14. Retrieved 2010-02-21.

- ^ Reuters (2010-02-26). "Grishin Grabs First Gold For Belarus". The New York Times. New York. Retrieved 2010-02-26.

{{cite news}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ "IOC rejects Quebec City request". Slam! Olympics. 1999-03-23. Retrieved 2009-01-07.

- ^ "Vancouver to host 2010 Winter Olympics". CBBC Newsround. 2003-07-02. Retrieved 2009-01-07.

- ^ www.CRSportsNews.com – Free Press Release Distribution Center (2009-02-24). "New Vancouver 2010 Sports Venues Completed". Crsportsnews.com. Retrieved 2010-01-10.

- ^ "Vancouver 2010 sport venues completed on time and within $580-million budget. Vancouver Olympic/Paralympic Centre opens today as a model of sustainable building – News Releases : Vancouver 2010 Winter Olympics and Paralympics". Vancouver2010.com. 2009-02-19. Retrieved 2010-01-10.

- ^ "2010 bid book an Etch-A-Sketch". The Tyee. July 2, 2009. Retrieved 2009-07-02.

- ^ "Olympic security estimated to cost $900M". CBC News. February 19, 2009.

- ^ "As Olympics near, people in Vancouver are dreading Games, Dave Zirin, Sports Illustrated/CNN, January 25, 2010". Sportsillustrated.cnn.com. 2010-01-25. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- ^ Mackin, Bob (2010-02-10). "Vancouver to reduce downtown traffic". Toronto Sun. QMI. Archived from the original on 2010-02-24. Retrieved 2010-02-24.

- ^ "Winter Olympics all wet?: Vancouver has the mildest climate of any Winter Games host city". Vancouver Sun. 2003-07-09.

- ^ "Daily Data Report for February 2010". National Climate Data and Information Archive. Environment Canada.

- ^ a b "GM Place to get new name for 2010". CTV News. 2008. Retrieved 2009-01-07.

- ^ "Measuring the Power of Sport". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 2010-02-04.

- ^ Wingrove, Josh (2009-08-21). "Vancouver Olympic designer dies at age 40". Globe and Mail. CTV Television Network. Retrieved 2010-02-14.

- ^ "2010 Vancouver Olympics' mascots inspired by First Nations creatures". CBC Sports. 2007-11-27. Retrieved 2007-11-27.

- ^ “14 circulating coins included in 2010 Olympic program”, Bret Evans, Canadian Coin News, January 23 to February 5, 2007 issue of Canadian Coin News

- ^ Shaw, Hollie (February 20, 2009). "What's Your Olympic Moment?". The National Post. Retrieved 2009-02-26.

- ^ "Vancouver 2010 Olympic Winter Games". USPS. January 22, 2010. Retrieved 2010-05-03.

- ^ "Weltweite Sportereignisse - Olympische Winterspiele 2010". Deutsche Post. February 11, 2010. Retrieved 2010-05-03.

- ^ "2010 Olympic Winter Gold Medallist". Australia Post. March 11, 2010. Retrieved 2010-05-03.

- ^ "Karl Benjamin - Viererblock". Post and Telecom Austria AG. February 12, 2010. Retrieved 2010-05-03.

- ^ "XXI Olympic Winter Games in Vancouver". Belpochta. January 25, 2010. Retrieved 2010-05-03.

- ^ "XXI. Olympic Winter Games". Croatian Post. February 1, 2010. Retrieved 2010-05-03.

- ^ "XXI. zimní olympijské hry Vancouver 2010". Ceska Posta. February 10, 2010. Retrieved 2010-05-03.

- ^ "XXI taliolümpiamängud Vancouveris". Eesti Post. February 12, 2010. Retrieved 2010-05-03.

- ^ "Diptyque J.O. d'Hiver de Vancouver". La Poste. February 8, 2010. Retrieved 2010-05-03.

- ^ "inter Olympic Games "Vancouver 2010". Poste Italiane. February 12, 2010. Retrieved 2010-05-03.

- ^ "Olympische Winterspiele Vancouver 2010". Poste Italiane. February 12, 2010. Retrieved 2010-05-03.

- ^ "XXI Olympic Winter Games". Lithuania Post. January 30, 2010. Retrieved 2010-05-03.

- ^ "VANCOUVER 2010 OLYMPIC WINTER GAMES". Polish Post. January 27, 2010. Retrieved 2010-05-03.

- ^ "PhilaShop - Olympische Spiele 2010" (in German). Die Post. Retrieved 2010-05-03.

- ^ "Untitled Document". PTT. Retrieved 2010-05-03.

- ^ "Philately". YKPNOWTA. February 5, 2010. On 05.02.2010 postage stamps ... Retrieved 2010-05-03.

- ^ "Vancouver 2010 signs new licensees to create products, auction off memorabilia capturing memories of Games". Vancouver 2010 Winter Olympics. 22 February 2010.

- ^ "OBSV Introduction". Obsv.ca. Retrieved 2010-01-10.

- ^ "Nancy Lee leaving CBC Sports", cbc.ca, October 10, 2006.

- ^ "CTV wins 2010 and 2012 Olympic broadcast rights". CBC Sports. 2005-02-09. Retrieved 2008-09-21.

- ^ a b "AP Seeks New Internet Business Model in Winter Olympics". Editor & Publisher. February 4, 2010. Retrieved 2010-02-04.

- ^ About this Vancouver 2010 Winter Games Microsite from wintergames.ap.org

- ^ Jeux olympiques d'Hiver: Vancouver 2010, France Télévisions

- ^ "Sitting Duck - Team". Sittingduckmusicandmedia.com. Retrieved 2010-04-02.

- ^ "Olympic flame lit for Vancouver Games". Russia Today. October 22, 2009. Retrieved 2009-10-22.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Funding for 2010 Olympics torch relay to focus on local events". CBC News. 2009-04-30. Retrieved 2009-12-23.

- ^

"2010 Olympic Torch relay general info". CTV. CTV. February 11, 2010. Retrieved 2010-02-11.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Governator takes the flame in Stanley Park". Vancouver Sun. Canwest Publishing. February 13, 2010. Retrieved 2010-02-15.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Nash, Rees, Set to Run with Torch". Victoria Times Colonist. Canwest Publishing. February 11, 2010. Retrieved 2010-02-11.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "For the next Hour, I am pure Canadian". Vancouver 24hr news. Canoe. February 11, 2010. Retrieved 2010-02-11.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Healthy Morneau excited to carry Torch". mlb.com. mlb.com. February 11, 2010. Retrieved 2010-02-11.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Michael Buble, Jann Arden to join in Olympic torch ceremony". vancouversun.com. Canwest Publishing. February 11, 2010. Retrieved 2010-02-11.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^

"Torchbearer 102 Bob Costas carries the flame in Burnaby". vancouver2010.com. vancouver2010.com. January 1, 2010. Retrieved 2010-02-12.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^

"Shania Twain carries Olympic torch". The Canadian Press. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. January 1, 2010. Retrieved 2010-02-12.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^

"Reserved, restrained, and rocking with Sid the Kid". ctvolympics.ca. The Globe and Mail. February 11, 2010. Retrieved 2010-02-11.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Pressing questions as Olympic hockey beckons". February 14, 2010. Retrieved 2010-02-15.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ CBC News (February 11, 2010). "Olympic fever builds in Vancouver". cbcsports.ca. Retrieved 2010-02-11.

- ^ Lederman, Marsha (February 8, 2010). "Schwarzenegger, Buble to carry torch". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 2010-02-08.

- ^ "Olympic Athletes, Teams and Countries". Vancouver 2010 Winter Olympics. VANOC. Retrieved 2010-02-27.

- ^ "Tongan athlete narrowly misses out on Winter Olympics", Australian Broadcasting Corporation, February 1, 2010

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w http://www.fis-ski.com/data/document/summary-quotas-allocation.pdf

- ^ "Sport | Kari Peters bleibt zu Hause". wort.lu. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- ^ "Sport | Stefano Speck fährt nicht nach Vancouver". wort.lu. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- ^ a b c d e f "Alpine team takes fall at 2010 Games – Vancouver 2010 Olympics". thestar.com. 2009-06-10. Retrieved 2010-01-10.

- ^ a b c d e "Germany, Norway round out 2010 Olympic men's hockey". TSN. 2009-02-08. Retrieved 2009-02-09.

- ^ "Athletes : Vancouver 2010 Winter Olympics". Vancouver2010.com. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- ^ a b c d e f "ISU Figure skating qualification system".

- ^ a b c d e f "2009 Figure Skating World Championship results".

- ^ "Saiba os brasileiros que podem ir a Vancouver".

- ^ "Bulgaria received one more quota for the games". Топспорт. Retrieved 2010-02-13.

- ^ "Travers is snow joke". Retrieved 2009-11-05.

- ^ "Olympic Qualification". World Curling Federation. Retrieved 2009-02-09.

- ^ "Suomen Olympiajoukkueeseen Vancouver 2010 -talvikisoihin on valittu 94 urheilijaa – kahdella miesalppihiihtäjällä vielä mahdollisuus lunastaa paikka joukkueessa – Suomen Olympiakomitea". Noc.fi. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- ^ "108 Français à Vancouver – JO 2010 – L'EQUIPE.FR". Vancouver2010.lequipe.fr. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- ^ "Ghana's 'Snow Leopard' qualifies to ski in 2010 Winter Olympics". CBC News. Retrieved 200http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=2010_Winter_Olympics&action=edit§ion=99-03-14.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); External link in|accessdate= - ^ "Short Track Speed Skating entry list". 24 November 2009. Retrieved 2009-11-26.

- ^ "Tashi and Jamyang qualify for 2010 Olympic Winter Games". 18 March 2009. Retrieved 2009-03-18.

- ^ a b "Lambiel crushes competition at Nebelhorn". Retrieved 2009-09-26.

- ^ "North Korea – CTV Olympics". Ctvolympics.ca. 2010-01-22. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- ^ "Sports | Mongolia Web News". Mongolia-web.com. Retrieved 2010-01-10.

- ^ "Genomineerden". Nocnsf.nl. Retrieved 2010-01-10.

- ^ "Anders Rekdal tatt ut til OL i Vancouver på overtid". Olympiatoppen (in Norwegian). 2010-01-29. Retrieved 2010-02-08.

- ^ "Wystartujemy w Vancouver" (in Polish). 19 March 2009. Retrieved 2009-03-19.

- ^ a b "Athletes : Vancouver 2010 Winter Olympics". Vancouver2010.com. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- ^ "OS-truppen komplett(erad) – Olympic Team complete(d)". SOC. 2010-12-01. Retrieved 2010-12-01.

- ^ "Vancouver 2010 Olympic Winter Games Qualifications | News | USA Luge". Luge.teamusa.org. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- ^ a b Mackin, Bob (2006-06-06). "VANOC shrinks Olympic ice". Slam! Sports. Retrieved 2009-01-07.

- ^ "2010 Olympic hockey will be NHL-sized". CBC News. 2006-06-08. Retrieved 2010-02-14.

- ^ "Ski-cross aims for Vancouver 2010". BBC Sport. 2006-06-12. Retrieved 2009-01-07.

- ^ "Ski-cross gets approved for 2010". BBC Sport. 2006-11-28. Retrieved 2009-01-07.

- ^ "Vancouver 2010: In good shape with positive progress on media accommodation". International Olympic Committee. 2007-03-09. Retrieved 2009-01-07.

- ^ "Olympic programme updates". International Olympic Committee. 2006-11-28. Retrieved 2009-01-07.

- ^ a b Vancouver2010.com July 10, 2009, article on the exclusion of women's ski jumping from the 2010 Games. – accessed July 11, 2009.

- ^ cbc.ca December 22, 2009, Supreme Court spurns women ski jumpers. – accessed December 22, 2009.

- ^ canada.com 4 Sep 2009 FIS advocates women's ski jump – accessed 22 December 2009.

- ^ "Vancouver 2010 Olympic Competition Schedule" (PDF). Vancouver Organizing Committee. Retrieved 2008-08-09.

- ^ a b 2010 Olympic Games Watch homepage

- ^ [1]

- ^ Straight.com

- ^ vancouverobserver.com

- ^ chicagoreader.com

- ^ "BBC Sport - Vancouver 2010 - Olympic luger Nodar Kumaritashvili dies after crash". BBC News. 2010-02-13. Retrieved 2010-04-02.

- ^ "Olympic luger Nodar Kumaritashvili dies after crash". BBC Sport. February 12, 2010. Retrieved 12 February 2010.

- ^ "The Tyee — Mush! Move Cypress Events to Okanagan". Thetyee.ca. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- ^ "Trucks start moving snow to Cypress Mountain from Manning Park". Vancouversun.com. 2010-02-02. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- ^ Mackin, Bob (2009-06-19). "Vancouver releases secret Olympic Village documents, Bob Mackin, The Tyee, June 19, 2009". Thetyee.ca. Retrieved 2010-01-10.

- ^ MACKIN, BOB (February 15, 2010). "Mishaps plague games". Toronto Sun. Retrieved February 16, 2010.

- ^ "Speed skating ice woes threaten green sheen". Reuters. February 16, 2010. Retrieved 16 February 2010.

- ^ a b spiegelonline sport (February 18, 2010). "Möge das Wirrwarr gewinnen" (in German). Retrieved February 18, 2010.

- ^ "VIP Olympic tickets going unused". Vancouver Sun. February 15, 2010. Retrieved February 18, 2010.

- ^ Gustus, Lauren, (Gannett News Service), "Starter error frustrates biathletes, guardsman", Military Times, February 18, 2010.

- ^ Barron, David (February 18, 2010). "BURNING ISSUES:Officials get cauldron right at "Glitch Games"". Houston Chronicle.

- ^ "Mayor is no fan of Olympic politics. But he did attend four hockey games and a speedskating event". Retrieved 2010-03-30. Corrigan's concern was with the politics in the site selection, notably his city losing out to another for the site of the speedskating oval.

- ^ Lee, Jeff (March 13, 2007). "Protesters arrested at Olympic flag illumination". The Vancouver Sun. Retrieved 2007-07-07.

- ^ 2010 Heart Attack disrupts Vancouver on day two of Winter Olympics

- ^ Vancouver police lay charges in weekend riot

- ^ W2 forum focuses on Black bloc tactics in February 13 protest against Vancouver Olympics

- ^ "http://www.sunypress.edu/p-3274-inside-the-olympic-industry.aspx". Sunypress.edu. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

{{cite web}}: External link in|title= - ^ "Anti-Olympics movement targeted: Some 15 VISU Joint Intelligence Group visits in 48 hours | San Francisco Bay View". Sfbayview.com. Retrieved 2010-04-02.

- ^ "Protesting the Olympics? - Institute for Public Accuracy (IPA)". Accuracy.org. 2010-02-12. Retrieved 2010-04-02.

- ^ The Earthtimes (2010-02-08). "Olympics? Take a walk on the wild side in Vancouver - Feature : Sports". Earthtimes.org. Retrieved 2010-04-02.

- ^ "Olympic games evict millions: Times Argus Online". Timesargus.com. 2007-06-06. Retrieved 2010-04-02.

- ^ "The Tyee — Will Olympics Be Magnet for Human Traffickers?". Thetyee.ca. 2008-09-04. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- ^ Kathie Wallace (2010-02-02). "Human Trafficking Alive and Well for the 2010 Olympics | The Vancouver Observer - Vancouver Olympics News Blogs Events Reviews". The Vancouver Observer. Retrieved 2010-04-02.

- ^ "Vancouver Olympics get an ‘F’ for failing to curb sex trafficking: group". Montrealgazette.com. 2010-02-09. Retrieved 2010-04-02.

- ^ 4HN_Protocol_Final_Nov 24.pub[dead link]

- ^ "Four Host First Nations". Four Host First Nations. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- ^ "Sutikalh Re-occupation Camp".

- ^ "It's all about the Land". The Dominion.

- ^ "Olympic inukshuk irks Inuit leader". CBC.ca Sports. April 27, 2005. Retrieved 2008-08-13.

- ^ Polish cross-country skier Marek tests positive for EPO at Vancouver Olympics

- ^ Warner, Adrian (2010-02-19). "London 2012 must get the ideas and the details right". BBC. Retrieved 2010-03-05.

- ^ Wilson, Stephen (2010-03-01). "Vancouver atmosphere will be tough to match". Associated Press. Retrieved 2010-03-05.

- ^ "Rogge 'happy' but luge death overshadows Vancouver". Agence France-Presse. 2010-02-28. Archived from the original on 2010-03-05. Retrieved 2010-03-05.

- ^ Donegan, Lawrence (2010-03-01). "Vancouver Winter Olympics Review: 'Mood on the streets was wonderful'" (Audio). The Guardian. Retrieved 2010-03-05.

- ^ "More cash for Own the Podium". Vancouver Sun. Canwest Publishing. March 4, 2010. Retrieved 2010-03-05.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "No cash earmarked for Own the Podium". Vancouver Sun. Canwest Publishing. March 4, 2010. Retrieved 2010-03-05.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)

External links

- Vancouver 2010 Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games, official website

- VANOCwebteam

- Vancouver 2010 from the International Olympic Committee

- Government of Canada 2010 Federal Secretariat

- CTV Olympics

- City of Vancouver, official Host City page

- The official Whistler website of the Vancouver 2010 Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games