Maluku Islands

| |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | South East Asia |

| Coordinates | 3°9′S 129°23′E / 3.150°S 129.383°E |

| Administration | |

Indonesia | |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 1,895,000 |

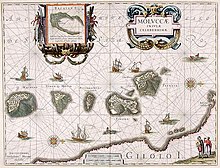

The Maluku Islands (also known as the Moluccas, Moluccan Islands, the Spice Islands) are an archipelago in Indonesia, and part of the larger Maritime Southeast Asia region. Tectonically they are located on the Halmahera Plate within the Molucca Sea Collision Zone. Geographically they are located east of Sulawesi (Celebes), west of New Guinea, and north of Timor. The islands were also historically known as the "Spice Islands" by the Chinese and Europeans, but this term has also been applied to other islands outside Indonesia.

Most of the islands are mountainous, some with active volcanoes, and enjoy a wet climate. The vegetation of the small and narrow islands, encompassed by the sea, is very luxuriant; including rainforests, sago, rice and the famous spices - nutmeg, cloves and mace, among others. Though originally Melanesian,[1] many island populations, especially in the Banda Islands, were killed off in the 17th century during the Spice wars. A second influx of Austronesian immigrants began in the early 20th century under the Dutch and continues in the Indonesian era.

Politically, the Maluku Islands formed a single province from 1950 until 1999. In 1999 the North Maluku (Maluku Utara) and Halmahera Tengah (Central Halmahera) regencies were split off as a separate province, so the islands are now divided between two provinces, Maluku and North Maluku. Between 1999 and 2002 they were known for religious conflicts between Muslims and Christians but have been peaceful in recent years.

Spice Islands most commonly refers to the Maluku Islands and often also to the small volcanic Banda Islands, once the only source of mace and nutmeg. This nickname should not be confused with Grenada, which is commonly known as the Island of Spice. The term has also been used less commonly in reference to other islands known for their spice production, notably the Zanzibar Archipelago off East Africa consisting of Unguja, Mafia and Pemba. These islands were formerly the independent state of Zanzibar but now form a semi-autonomous part of Tanzania.

Geography

The Maluku Islands are often described by tourist literature as having 999 islands; they are 90% sea with 77,990 km2 of land, and 776,500 km2 of sea.[2]

- Ternate, main island

- Bacan

- Halmahera - at 20,000 km2 is the largest of the Maluku Islands.[3]

- Morotai

- Obi Islands

- Sula Islands

- Tidore

- Ambon Island, main island

- Aru Islands

- Babar Islands

- Banda Islands

- Buru

- Kai Islands

- Kisar

- Leti Islands

- Seram

- Tanimbar Islands

- Wetar

Etymology

The name Maluku is thought to have been derived from the Arab trader's term for the region, Jazirat al-Muluk ('the island of the kings').[4]

History

Background: "The Spice Islands"

The native Bandanese people traded spices with other Asian nations, such as China, since at least the time of the Roman Empire. With the rise of Islam, the trade became dominated by Muslim traders. One ancient Arabic source appears to know the location of the islands, describing them as fifteen days' sail East from the 'island of Jaba' - presumably Java [citation needed] — but direct evidence of Islam in the archipelago occurs only in the late 14th century, as China's interest in regional maritime dominance waned. With Muslim traders came not just Islam, but a new technique of social organisation, the sultanate, which replaced local councils of rich men (orang kaya) on the more important islands, and proved more effective in dealing with outsiders. (See Ternate & Tidore).

By trading with Muslim states, Venice came to monopolise the spice trade in Europe between 1200 and 1500, through its dominance over Mediterranean seaways to ports such as Alexandria, after traditional overland connections were disrupted by Mongols and Turks. The financial incentive to discover an alternative to Venice's monopoly control of this lucrative business was perhaps the single most important factor precipitating Europe's Age of Exploration. Portugal took an early lead charting the route around the southern tip of Africa, securing bases and outposts en route, even discovering the coast of Brazil in the search for favourable southerly currents. Portugal's eventual success and the establishment of its own empire provoked the other maritime powers in Europe—Spain (see Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan), France, England and the Netherlands—to challenge and eventually overcome the Portuguese position.

Because of the high value that spices had in Europe and the large profits rendered, the Dutch and British soon joined in the conflicts to try to gain a monopoly over the trade and expel Portugal. The fighting for control over these small islands became very intense in the 17th and 18th centuries with the Dutch even giving the island of Manhattan to the British in exchange for, among other things, the tiny island of Run which gave the Dutch full control over the Banda archipelago's nutmeg production. The Bandanese people lost the most in the fighting with most of the them being either slaughtered or enslaved by the European interlopers. Over 6,000 were killed during the Spice wars.

The goal of reaching the Spice Islands, eventually to be enveloped by the Dutch East Indies Empire, led to the accidental discovery of the West Indies, and lit the fuse of centuries of rivalry between European maritime powers for control of lucrative global markets and resources. The tattered mystique of the Spice Islands finally vanished when France and Britain successfully smuggled seeds and plants to their own dominions on Mauritius, Grenada and elsewhere, making spices the commonplace and affordable commodity of today.

Early history

The earliest archaeological evidence of human occupation of the region is about thirty-two thousand years old, but evidence of even older settlements in Australia may mean that Maluku had earlier visitors. Evidence of increasingly long-distance trading relationships and of more frequent occupation of many islands, begins about ten to fifteen thousand years later. Onyx beads and segments of silver plate used as currency on the Indian subcontinent around 200BC have been unearthed on some of the islands. In addition, local dialects employ derivations of the Malay word then in use for 'silver', in contrast to the term used in wider Melanesian society, which has etymological roots in Chinese, a consequence of the regional trade with China that developed in the 6th century and 7th century.

Maluku was a cosmopolitan society where spice traders from across the region took residence in settlements, or in nearby enclaves, including Arab and Chinese traders who visited or lived in the region. Social organization was usually local, and relatively flat - a general populace guided by a council of elders or rich men, or Orang kaya.

Arabic merchants began to arrive in the 14th century, bringing Islam. Peaceful conversion to Islam occurred in many islands, especially in centres of trade, while aboriginal animism persisted in the hinterlands and more isolated islands. Archaeological evidence here relies largely on the occurrence of pigs' teeth, as evidence of pork eating or abstinence therefrom.[5]

The Portuguese

Apart from some relative inconsequential cultural influences, the most significant lasting effects of the Portuguese presence was the disruption and reorganisation of Asian trade, and in eastern Indonesia—including Maluku—the planting of Christianity.[6] The Portuguese had conquered Malacca in the early 16th century and their lasting influence was most strongly felt in Maluku and other parts of eastern Indonesia.[4] The Portuguese conquered Malacca in August 1511, one Portuguese diary noted that 'it is thirty years since they became Moors' [7]- giving a sense of the competition then taking place between Islamic and European influences in the region. Afonso de Albuquerque learned of the route to the Banda Islands and other 'Spice Islands', and sent an exploratory expedition of three vessels under the command of António de Abreu, Simão Afonso Bisigudo and Francisco Serrão.[8] On the way to return, Francisco Serrão was shipwrecked at Hitu island (northern Ambon) in 1512. There he established ties with the local ruler who was impressed with his martial skills. The rulers of the competing island states of Ternate and Tidore also sought Portuguese assistance and the newcomers were welcomed in the area as buyers of supplies and spices during a lull in the regional trade due to the temporary disruption of Javanese and Malay sailings to the area following the 1511 conflict in Malacca. The spice trade soon revived but the Portuguese were never able to fully dominate nor stop this trade.[4]

Allying himself with Ternate, Serrão constructed a fortress on that tiny island and served as the head of a mercenary band of Portuguese warriors under the service of one of the two local feuding sultans who controlled most of the spice trade. Such an outpost far from Europe generally only attracted the most desperate and avaricious, and as such the feeble attempts at Christianisation only strained relations with Ternate's Muslim ruler.[4] Serrão urged Ferdinand Magellan to join him in Maluku, and sent the explorer information about the Spice Islands. Both Serrão and Magellan, however, perished before they could meet one another.[4] In 1535 Sultan Tabariji was deposed and sent to Goa in chains, he then converted to Christianity and changed his name to Dom Manuel. After being declared innocent of the charges against him he was sent back to reassume his throne, but he died en route in Malacca in 1545. He had, however, bequeathed the island of Ambon to his Portuguese godfather Jordão de Freitas. Following the murder of Sultan Hairun at the hands of the Portuguese, the Ternateans expelled the hated foreigners in 1575 after a five-year siege.

The Portuguese first landed in Ambon in 1513, but it only became the new centre for Portuguese activities in Maluku following their expulsion from Ternate. European power in the region was weak and Ternate became an expanding, fiercely Islamic and anti-European state under the rule of Sultan Baab Ullah (r. 1570 - 1583) and his son Sultan Said.[9] The Portuguese in Ambon, however, were regularly attacked by native Muslims on the island's northern coast, in particular Hitu, which had trading and religious links with major port cities on Java's north coast. Indeed, the Portuguese never managed to control the local trade in spices, and failed in attempts to establish their authority over the crucial Banda Islands, the nearby centre of most nutmeg production.

Following Portuguese missionary work, there have been large Christian communities in eastern Indonesia through to contemporary times, which has contributed to a sense of shared interest with Europeans, particularly among the Ambonese.[9] By the 1560s there were 10,000 Catholics in the area, mostly on Ambon, and by the 1590s there were 50,000 to 60,000, although most of the region surrounding Ambon remained Muslim.[9] The Spaniard missionary Francis Xavier also played an important role in Maluku Christianization (see next section).

Other Portuguese influences include a large number of Indonesian words derived from Portuguese which alongside Malay was the lingua franca up until the early 19th century. Contemporary Indonesian words such as pesta ('party'), sabun ('soap'), bendera ('flag'), meja ('table'), Minggu ('Sunday'), all derive from the Portuguese. Many family names in Maluku are derived from Portuguese including da Lima, da Costa, Dias, da Freitas, Gonsalves, Mendoza, Rodrigues, and da Silva. Also of partly-Portuguese origin are the romantic keroncong ballads sung to a guitar.

The Spanish

The Spanish settled and took control of Tidore in 1603 to trade with spices and to counter Dutch encroachment in the archipelago. The territory was incorporated into the Spanish East Indies and governed from Manila, in the Philippines. Missionary and Catholic Saint, Francis Xavier had worked in Maluku in 1546–1547 among the peoples of Ambon, Ternate and Morotai (or Moro), and laid the foundations for the Christian religion there. The Spanish presence lasted until 1663, when settlers and military were moved back to the Philippines. Part of the Ternatean population chose to leave with the Spanish, settling near Manila in what later became Ternate, Cavite.

The Dutch

The Dutch arrived in 1599 and reported native discontent with Portuguese attempts to monopolise their traditional trade. After the Ambonese helped the Dutch to construct a fort at Hitu Larna, the Portuguese began a campaign of retribution against which the Ambonese invited Dutch aid. After 1605 Frederik Houtman became the first Dutch governor of Ambon.

The Dutch East India Company was a company with three obstacles in its way: the Portuguese, controlling the aboriginal populations, and the English. Again smuggling would be the only alternative to a European monopoly. Among other events of the 17th century, the Bandanese attempted independent trade with the English, the East-India Company's response was to decimate the native population of the Banda Islands sending the survivors fleeing to other islands and installing slave labour.

Though other races re-settled the Banda Islands, the rest of Maluku remained uneasy under foreign control and even after the Portuguese had a new trading station at Macassar there were native revolts in 1636 and 1646. Under company control northern Maluka was administered by the Dutch residency of Ternate, and the southern by "Amboyna" (Ambon). During the Japanese occupation in World War II, the Moluccans fled to the mountains but began a campaign of resistance also known as the South Moluccan Brigade. After the war's end the island's political leaders had successful discussions with the Netherlands about independence. Complicated by Indonesian demands, the Round Table Conference Agreements were signed in 1949 transferring Maluku to Indonesia with mechanisms for the islands to choose or opt out of the new Indonesia. The Agreements granted Moluccans the right to determine their ultimate sovereignty.

After Indonesian independence

With the declaration of a single republic of Indonesia in 1950 to replace the federal state, the South Moluccas (Republik Maluku Selatan, RMS) attempted to secede. This movement was led by Chris Soumokil (former Supreme Prosecutor of the Eastern Indonesia state) and supported by the Moluccan members of the Netherlands special troops. This movement was defeated by the Indonesian army after 17 years of bloody struggle and by special agreement with the Netherlands the troops were transferred to the Netherlands. The commencement of Indonesian transmigration of (mainly Javanese) populations to the outer islands (including Maluku) during the 1960s is thought to have aggravated independence and issues of religious / ethnic politics. There has been occasional ethnic and nationalist violence on the islands.

Maluku is one of the first provinces of Indonesia, proclaimed in 1945 until 1999, when the Maluku Utara and Halmahera Tengah Regencies were split off as a separate province of North Maluku. Its capital is Ternate, on a small island to the west of the large island of Halmahera. The capital of the remaining part of Maluku province remains at Ambon.

The 1999-2003 inter-communal conflict

The situation in much of Maluku became highly unpredictable when religious-nuance conflict erupted in the province in January 1999. The subsequent 18 months were characterized by fighting between largely local groups of Muslims and Christians, the destruction of thousands of houses, the displacement of approximately 500,000 people, the loss of thousands of lives, and the segregation of Muslims and Christians.[10] The following 12 months saw periodic eruptions of violence, which appeared more targeted and premeditated, which helped keep suspicions high and people segregated (although these experiences were generally the norm). In spite of numerous negotiations and the signing of the February 2002 Malino II peace agreement, tensions on Ambon remained high until late 2002. However, the sudden disbanding of Laskar Jihad in October 2002 led to an increasingly stable peace and a series of spontaneous 'mixings' between previously hostile groups.

Minor disturbances continued through 2003 but Maluku had returned to general peacefulness by 2004. Many burnt buildings remain however, and some villages have yet to be fully reconstructed.

Geology and ecology

The geology and ecology of the Maluku Islands share much similar history, characteristics and processes with the neighbouring Nusa Tenggara region. There is a long history of geological study of these regions since Indonesian colonial times; however, the geological formation and progression is not fully understood, and theories of the island's geological evolution have changed extensively in recent decades.[11] The Maluku Islands comprise some of the most geologically complex and active regions in the world,[12] resulting from its position at the meeting point of four geological plates and two continental blocks.

Biogeographically, the islands lie in Wallacea, the region between the Sunda Shelf (part of the Asia block), and the Arafura Shelf (part of the Australian block). More specifically, they lie between Weber's Line and Lydekker's Line, and thus have a fauna that is rather more Australasian than Asian. Malukan biodiversity and its distribution are affected by various tectonic activities; most of the islands are geologically young, being from 1 million to 15 million years old, and have never been attached to the larger landmasses. The Maluku islands differ from other areas in Indonesia; they contain some of the country's smallest islands, coral island reefs scattered through some of the deepest seas in the world, and no large islands such as Java or Sumatra. Flora and fauna immigration between islands is thus restricted, leading to a high rate of endemic biota evolving.[11]

The ecology of the Maluku Islands has fascinated naturalists for centuries; Alfred Wallace's book, The Malay Archipelago was the first significant study of the area's natural history, and remains an important resource for studying Indonesian biodiversity. Maluku is the subject of two major historical works of natural history by George Everhard Rumpf: the Herbarium Amboinense and the Amboinsche Rariteitkamer.[13]

While many ecological problems affect both small islands and large landmasses, small islands suffer their particular problems. Development pressures on small islands are increasing, although their effects are not always anticipated. Although Indonesia is richly endowed with natural resources, the resources of the small islands of Maluku are limited and specialised; furthermore, human resources in particular are limited.[14]

General observations[15] about small islands that can be applied to the Maluku Islands include:[14]

- a higher proportion of the landmass will be affected by volcanic activity, earthquakes, landslips, and cyclone damage;

- Climates are more likely to be maritime influenced;

- Catchment areas are smaller and degree of erosion higher;

- A higher proportion of the landmass is made up of coastal areas;

- A higher degree of environmental specialisation, including a higher proportion of endemic species in an overall depauperate community;

- Societies may retain a strong sense of culture having developed in relative isolation;

- Small island populations are more likely to be affected by economic migration.

In 1997 the Manusela National Park, and in 2004 the Aketajawe-Lolobata National Park have been established, for the protection of endangered species.

Further reading

- George Miller (editor), To The Spice Islands And Beyond: Travels in Eastern Indonesia, Oxford University Press, 1996, Paperback, 310 pages, ISBN 967-65-3099-9

- Severin, Tim The Spice Island Voyage: In Search of Wallace, Abacus, 1997, paperback, 302 pages, ISBN 0-349-11040-9

- Bergreen, Laurence Over the Edge of the World, Morrow, 2003, paperback, 480 pages

External Links

References

General

- Bellwood, Peter (1997). Prehistory of the Indo-Malaysian archipelago. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 0-8248-1883-0.

- Andaya, Leonard Y. (1993). The World of Maluku: Eastern Indonesia in the Early Modern Period. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 0-8248-1490-8.

- Donkin, R. A. (1997). Between East and West: The Moluccas and the Traffic in Spices Up to the Arrival of Europeans. American Philosophical Society. ISBN 0-87169-248-1.

- Monk, Kathryn A., Yance De Fretes, Gayatri Reksodiharjo-Lilley (1997). The Ecology of Nusa Tenggara and Maluku. Singapore: Periplus Press. ISBN 962-593-076-0.

- Van Oosterzee, Penny (1997). Where Worlds Collide: The Wallace Line. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-8497-9.

- Wallace, Alfred Russel (2000; originally published 1869). The Malay Archipelago. Singapore: Periplus Press. ISBN 962-593-645-9.

Notes

- ^ IRJA.org

- ^ Monk, K.A. (1996). The Ecology of Nusa Tenggara and Maluku. Hong Kong: Periplus Editions Ltd. p. 9. ISBN 962-593-076-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Monk, K.A. (1996). The Ecology of Nusa Tenggara and Maluku. Hong Kong: Periplus Editions Ltd. p. 7. ISBN 962-593-076-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e Ricklefs, M.C. (1991). A History of Modern Indonesia Since c.1300, 2nd Edition. London: MacMillan. p. 24. ISBN 0-333-57689-6.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Lape, PV. (2000). Contact and Colonialism in the Banda Islands, Maluku, Indonesia; Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association Bulletin 20 (Melaka Papers, Vol.4); http://ejournal.anu.edu.au/index.php/bippa/article/viewFile/237/227

- ^ Ricklefs, M.C. (1991). A History of Modern Indonesia Since c.1300, 2nd Edition. London: MacMillan. p. 26. ISBN 0-333-57689-6.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Lach, DF. (1994) Asia in the Making of Europe: The Century of Discovery (Vol 1), Chicago University Press

- ^ E. C. Abendanon and E. Heawood (1919). "Missing Links in the Development of the Ancient Portuguese Cartography of the Netherlands East Indian Archipelago". The Geographical Journal. 54 (6). Blackwell Publishing: 347–355. doi:10.2307/1779411. JSTOR 10.2307/1779411.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Ricklefs, M.C. (1991). A History of Modern Indonesia Since c.1300, 2nd Edition. London: MacMillan. p. 25. ISBN 0-333-57689-6.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Troubled history of the Moluccas". BBC News. 26 June 2000. Retrieved 2007-05-17.

- ^ a b Monk (1996), page 9

- ^ Monk,, K.A. (1996). The Ecology of Nusa Tenggara and Maluku. Hong Kong: Periplus Editions Ltd. p. 9. ISBN 962-593-076-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Monk,, K.A. (1996). The Ecology of Nusa Tenggara and Maluku. Hong Kong: Periplus Editions Ltd. p. 4. ISBN 962-593-076-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ a b Monk,, K.A. (1996). The Ecology of Nusa Tenggara and Maluku. Hong Kong: Periplus Editions Ltd. p. 1. ISBN 962-593-076-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Beller, W., P. d'Ayala, and P. Hein. 1990. Sustainable development and environmental management of small islands. Paris and New Jersey: United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organisation and Parthenon Publishing Group Inc.; Hess, A, 1990. Overview: sustainable development and environmental management of small islands. In Sustainable development and environmental management of small islands. eds W. Beller, P. d'Ayala, and P. Hein, Paris and New Jersey: United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organisation and Parthenon Publishing Group Inc. (both cited in Monk)

External links

- Deforestation in the Moluccas

- The Spanish presence in the Moluccas: Ternate and Tidore

- An interesting article linking British possession of Run, a Banda Island, with the history of New York

- Jeremy Seabrook on the same theme

- Inter-Faith Alliances in the Moluccas

- History of the Spice Islands discovery

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)