Deutschlandlied

| English: The Song of the Germans | |

|---|---|

| |

National anthem of | |

| Also known as | Das Deutschlandlied (English: The Song of Germany) Deutschland über alles (English: Germany above all) |

| Lyrics | August Heinrich Hoffmann von Fallersleben, 1841 |

| Music | Joseph Haydn, 1797 |

| Adopted | 1922 |

| Audio sample | |

Das Lied der Deutschen (Instrumental) | |

The Deutschlandlied ("Song of Germany", German pronunciation: [ˈdɔʏtʃlantˌliːt]; also known as "Das Lied der Deutschen" or "The Song of the Germans"), has been used wholly or partially as the national anthem of Germany since 1922. The music was written by Joseph Haydn in 1797 as an anthem for the birthday of the Austrian Emperor Francis II of the Holy Roman Empire. In 1841, the German linguist and poet August Heinrich Hoffmann von Fallersleben wrote the lyrics of "Das Lied der Deutschen" to Haydn's melody, lyrics that were considered revolutionary at the time.

The song is as well-known by the opening words and refrain of the first stanza, "Deutschland, Deutschland über alles" (Germany above all), but this has never been its title. The line "Germany, Germany above all" meant that the most important goal of the Vormärz revolutionaries should be a unified Germany overcoming the perceived anti-liberal Kleinstaaterei. Alongside the Flag of Germany it was one of the symbols of the March Revolution of 1848.

In order to endorse its republican and liberal tradition, the song was chosen for national anthem of Germany in 1922, during the Weimar Republic. West Germany adopted the Deutschlandlied as its official national anthem in 1952 for similar reasons, with only the third stanza sung on official occasions. Upon German reunification in 1990, the third stanza only was confirmed as the national anthem.

Melody

The melody of the Deutschlandlied was originally written by Joseph Haydn in 1797 to provide music to the poem "Gott erhalte Franz den Kaiser" ("God save Emperor Francis") by Lorenz Leopold Haschka. The song was a birthday anthem to Francis II, Holy Roman Emperor of the House of Habsburg. The piece is Movement II (Poco adagio) of Opus 76 No. 3, a string quartet often called "Emperor" or "Kaiser." The melody in this movement is also termed the "Emperor's Hymn." After the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806, Francis continued to rule as Austrian Emperor. "Gott erhalte Franz den Kaiser" became the official anthem of the emperor of the Austrian Empire and the subsequent Austria-Hungary until the end of the Austrian monarchy in 1918.

Historical background

The Holy Roman Empire was already weak when the French Revolution and the ensuing Napoleonic Wars altered the political map of Central Europe. Hopes for the Enlightenment, human rights, republican government, democracy, and freedom after Napoleon's defeat in 1815 were dashed, however, when the Congress of Vienna reinstated many monarchies. In addition, with the Carlsbad Decrees of 1819, Chancellor Prince Metternich and his secret police enforced censorship, mainly in universities, to keep a watch on the activities of professors and students, whom he held responsible for the spread of radical liberal ideas. Particularly since hardliners among the monarchs were the main adversaries, demands for freedom of the press and other liberal rights were most often uttered in connection with the demand for a united Germany, even though many revolutionaries-to-be had different opinions whether a republic or a constitutional monarchy would be the best solution for Germany.

The German Confederation or German Union (Deutscher Bund) was a loose confederation of 39 monarchical states and republican free cities, with a Federal Assembly in Frankfurt. They began to remove internal customs barriers during the Industrial Revolution, though, and the German Customs Union Zollverein was formed among the majority of the states in 1834. In 1840 Hoffmann wrote a song about the Zollverein, also to Haydn's melody, in which he praised the free trade of German goods which brought Germans and Germany closer.[2]

After the March Revolution of 1848, the German Confederation handed over its authority to the Frankfurt Parliament, and Eastern Prussia joined the Confederation. For a short period in the late 1840s, Germany was united with Hoffman's borders, with a democratic constitution in the make, and with the black-red-gold flag to represent it. The two big monarchies put an end to this, and waged the Austro-Prussian War against each other.

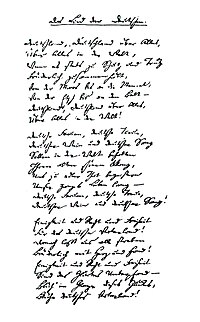

Hoffmann's lyrics

August Heinrich Hoffmann (who called himself von Fallersleben after his home town to distinguish himself from others with the same common name of "Hoffmann") wrote the text in 1841 on vacation on the North Sea island Heligoland, then a possession of the United Kingdom.

Hoffmann von Fallersleben intended Das Lied der Deutschen to be sung to Haydn's tune, as the first publication of the poem included the music. The first line, "Deutschland, Deutschland über alles, über alles in der Welt" (usually translated into English as "Germany, Germany above all, above all in the world"), was an appeal to the various German monarchs to give the creation of a united Germany a higher priority than the independence of their small states. In the third stanza, with a call for "Einigkeit und Recht und Freiheit" (unity and justice and freedom), Hoffmann expressed his desire for a united and free Germany where the rule of law, not monarchical arbitrariness, would prevail.[3]

In the era after the Congress of Vienna, which was influenced by Prince Metternich and his secret police, Hoffmann's text had a distinctly revolutionary, and at the same time liberal, connotation, since the demand for a united Germany was most often made in connection with demands for freedom of press and other liberal rights. Its implication that loyalty to a larger Germany should replace loyalty to one's sovereign personally was in itself a revolutionary idea.

The year after he wrote Das Deutschlandlied, Hoffmann von Fallersleben lost his job as a librarian and professor in Breslau, Prussia because of this and other revolutionary works, and was forced into hiding until being pardoned after the revolutions of 1848.

Lyrics and translation

The following provides the lyrics of the "Lied der Deutschen" as written by Hoffmann von Fallersleben. Only the third verse is currently the Federal Republic of Germany's national anthem.

| Deutschlandlied | |

|---|---|

| German lyrics | Approximate translation |

| First stanza | |

Deutschland, Deutschland über alles, |

|

| Second stanza | |

Deutsche Frauen, deutsche Treue, |

German women, German loyalty, |

| Third stanza (Germany's National Anthem) | |

Einigkeit und Recht und Freiheit |

Unity and justice and freedom |

Geography

In 1841, when the text was written, the German Confederation was not a unified state in the modern sense. It also included a few regions inhabited largely by non-German speakers, but excluded large areas inhabited primarily by German-speakers, like parts of Eastern Prussia. Hoffmann, who in his research had collected German writings and tales, based his definition of Germany on linguistic criteria: he described the approximate area where a majority of German speakers lived at the time, as encountered in his studies. 19th century nationalists generally relied on such linguistic criteria to determine the borders of the nation-states they desired. Thus, the borders mentioned in the first stanza loosely reflected the breadth of territory across which German speakers were spread at the time.

|

Von der Maas bis an die Memel, |

From the Meuse to the Memel, |

- In the west, the river known as the Maas or the Meuse ran through the Dutch-ruled and Limburgish-speaking Duchy of Limburg which was joined to the German Confederation between September 5, 1839 and August 23, 1866. The modern German border is close to the river in that area.

- In the east, the lower part of the Memel, known in other languages as the Neman, was located within East Prussia, part of the Kingdom of Prussia, which actually stretched north beyond the river, and beyond the city of Memel (Klaipeda). In 1920, the area north of the river was detached from Germany and became known as Memelland. Only a few German speakers remained in the area after 1945.

- In the south, the Adige river (German: Etsch) runs to the Adriatic. In 1841, the Austrian Empire ruled all of its length, and much of the population of its area was German. The river's northern part was within Austrian Tirol, but became part of Italy after 1918. Now, as then, the town of Salorno (German: Salurn), marks the linguistic border between the German and the Italian speaking population in the valley.

- To the north, the strait known as the Little Belt (Danish: Lillebælt) ran alongside the ethnically mixed Danish Duchy of Schleswig, part of an area subject to a highly complex dispute, known as the Schleswig-Holstein Question, between Denmark and its neighbors. After wars in 1848 and 1864 the Danish-German border for some time ran through the strait, but ultimately, the Schleswig Plebiscite, moved the border to its current location, south of the Little Belt.

In the south and in the west, Hoffmann's definition of Germany coincided with the borders of the German Confederation as it existed then. Hoffmann went beyond the Confederation boundaries of 1841 in the north and in the east, as neither South Schleswig nor East Prussia (although both German-speaking) belonged to it at that time yet, but joined before 1866. Thus, when the German Empire was finally founded in 1871, both were parts of the German Empire, whereas Luxemburg, Limburg, and Austria were not (see Kleindeutsche Lösung). Hoffmann picked only one marker in the south and, possibly to avoid confrontation, made no mention of other areas inhabited by German speakers, like Alsace, Switzerland, or the Eastern part of the Austrian Empire.

Use before the Second World War

Das Lied der Deutschen was not played at an official ceremony until Germany and the United Kingdom had agreed on the Helgoland-Zanzibar Treaty in 1890, when it appeared only appropriate to sing it at the ceremony on the now officially German island of Helgoland.

The song became very popular after the 1914 Battle of Langemarck during World War I, when, supposedly, several German regiments, consisting mostly of students no older than 16, attacked the British lines singing the song, suffering heavy casualties. They are buried in the Langemark German war cemetery. The official report of the army embellished the event as one of young German soldiers heroically sacrificing their lives for the fatherland. In reality the untrained troops were sent out to attack the British trenches side by side and were mowed down by machine guns. This report, also known as the "Langemarck Myth", was printed on the first page in newspapers all over Germany. It is doubtful that the soldiers would have sung the song in the first place: carrying heavy equipment, they might have found it difficult to run at high speeds toward enemy lines while singing the very slow song. Nonetheless, the story was widely repeated, and Adolf Hitler himself, who had "received his baptism by fire at Langemarck," claimed to have heard the song as machine gun fire killed his fellow soldiers.[4]

On 11 August 1922 President Friedrich Ebert made the Deutschlandlied the official German national anthem, as one element of a complex political negotiation. In essence, the political right was granted the very nationalistic anthem, while the left had its way in the selection of the national colors (the right wanted red, black, and white, the old imperial colors; the left wanted red, black, and gold). Considering the post-World War II history of the anthem, it is worthwhile noting that Ebert already advocated using only the anthem's third stanza.[5]

Use during Nazi rule

During the Nazi era, only the first stanza was used, followed by the SA song Horst-Wessel-Lied.[6]

Use after World War II

In 1945, after the end of World War II, singing Das Lied der Deutschen and other symbols used by Nazi Germany were banned for some time by the Allies. The Germans were expelled up to 500 km to the West, behind the Oder and Neisse rivers.

After its founding in 1949, West Germany did not have a national anthem for official events for some years despite the growing need for proper diplomatic procedures. Different songs were discussed or used, such as Ludwig van Beethoven's Ode An die Freude (Ode To Joy). Though the black, red and gold colours of the national flag had been incorporated into Article 22 of the (West) German constitution, a national anthem was not specified. On 29 April 1952, Chancellor Konrad Adenauer asked President Theodor Heuss in a letter to accept Das Lied der Deutschen as the national anthem, with only the third stanza sung on official occasions. President Heuss agreed to this on 2 May 1952. This exchange of letters was published in the Bulletin of the Federal Government. Since it was viewed as the traditional right of the president as head of state to set the symbols of the state, the Deutschlandlied thus became the national anthem.[7]

Meanwhile, East Germany adopted its own national anthem, Auferstanden aus Ruinen (Risen from the Ruins). As the lyrics called for "Germany, united Fatherland", they were not sung anymore when this idea was dropped in the 1970s. It is a legend that it was originally written to fit the same Haydn melody, but later got its own: The lyrics do not fit completely to the Haydn melody.

When West Germany won the 1954 FIFA World Cup Final in Bern, Switzerland, the lyrics of the first stanza dominated when the crowd sang along to celebrate the surprise victory that was later dubbed Miracle of Bern .[8]

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, efforts were made by conservatives in Germany to reclaim all three stanzas for the anthem; the Christian Democratic Union of Baden-Württemberg, for instance, attempted twice (in 1985 and 1986) to make German high school students study all three stanzas, and in 1989 CDU politician Christean Wagner decreed that all high school students in Hesse were to memorize the three stanzas.[9]

On 7 March 1990, months before reunification, the Constitutional Court declared only the third stanza of Hoffmann von Fallersleben's poem to be protected as a national anthem under criminal law; Section 90a of the Criminal Code (Strafgesetzbuch) makes defamation of the national anthem a crime, but does not specify what the national anthem is.

In November 1991, President Richard von Weizsäcker and Chancellor Helmut Kohl agreed in an exchange of letters to declare the third stanza alone the national anthem of the enlarged republic. On official occasions, Haydn's music is used, and only the third stanza is supposed to be sung. For other uses, all stanzas may be performed. The opening line of the third stanza, Einigkeit und Recht und Freiheit, ("Unity and justice and freedom") appears on soldiers' belts, was engraved into the rim of former 5-Deutsche Mark coins, and is currently present on 2-Euro coins minted in Germany.

Modern criticisms

Despite the text and tune of the song being remarkably peaceful compared to many other national anthems, the song has frequently been criticised for its generally nationalist theme, the geographic definition of Germany given in the first stanza, and the somewhat male chauvinist attitude in the second stanza.[10][11] An early critic was Friedrich Nietzsche, who called the grandiose claim in the first stanza ("Deutschland über alles") "the dumbest phrase in the world."[10]

Variants, additions, and controversial performances

Variants and additional or alternate stanzas

Hoffmann von Fallersleben also intended the text to be used as a drinking song; the second stanza's toast to German women and wine are typical of this genre.[citation needed] The original Helgoland manuscript included a variant ending of the third stanza for such occasions:

| Alternate third stanza | |

|---|---|

Einigkeit und Recht und Freiheit |

Unity and justice and freedom |

In 1921, Albert Matthai wrote a stanza in reaction to Germany's losses in and after World War I. This stanza was never used as a national anthem and was not part of the Deutschlandlied.

| Stanza by Matthai, 1921 | |

|---|---|

Deutschland, Deutschland über alles |

Germany, Germany above everything, |

An alternate version by Bertolt Brecht gained currency after the unification of Germany, with a number of prominent Germans opting for his "antihymn":[12]

| Kinderhymne by Bertolt Brecht (tr. Michael E. Geisler) | |

|---|---|

Anmut sparet nicht noch Mühe |

Grace spare not and spare no labor |

Notable performances, covers

The German musician Nico sometimes performed the national anthem at concerts and dedicated it to militant Andreas Baader, leader of the Red Army Faction.[13] She included a version of Das Lied der Deutschen on her 1973 album The End. In 2006, the Slovenian industrial band Laibach incorporated Hoffmann's lyrics in a song titled "Germania," on the album Volk, which contains fourteen songs with adaptations of national anthems.[14][15] Performing the song in Germany in 2009, the band cited the first stanza in the closing refrain, while on a video screen images were shown of a German city bombed during World War II.[16]

In November 2009, the English singer Pete Doherty caused a stir when, live on the Bayerischer Rundfunk radio in Munich, he sang the first stanza of the anthem; he was booed by the audience and after a few more songs the radio station pulled the plug on the show and the radio transmission.[17]

Pop parody

An awkward submission to the German entertainment show TV Total was aired to the amusement of the audience. It featured the African-American woman Verna Mae Bentley-Krause singing a self invented hymn in broken German, which quickly became a running gag in Stefan Raab's TV show whenever an event of national importance was reported on. In subsequent sporting events organized by Stefan Raab (like the Wok racing competition or the TV Total Stock Car Challenge) the re-recorded song “Ich liebe deutsche Land” (I love German country) is played in place of the Deutschlandlied and is announced as the national anthem of Germany. The song gained minor international publicity when it was sung in celebration to the victory of Lena Meyer-Landrut at the 2010 Eurovision Song Contest by the German delegation.[citation needed]

See also

References

- ^ "Die letzten deutschen Kriegsgefangenen". Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (in German). 26 July 2007. Retrieved 13 August 2007.

- ^ "Schwefelhölzer, Fenchel, Bricken (Der deutsche Zollverein)". www.von-fallersleben.de (in German). Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ Bareth, Nadja (February 2005). "Staatssymbole Zeichen politischer Gemeinschaft". Blickpunt Bundestag (in German). Retrieved 1 December 2009.

- ^ Mosse, George L. (1991). Fallen Soldiers: Reshaping the Memory of the World Wars. Oxford UP. pp. 70–73. ISBN 9780195071399.

- ^ Geisler, Michael E. (2005). National symbols, fractured identities: Contesting the national narrative. UPNE. p. 70. ISBN 9781584654377.

- ^ Geisler, p.71.

- ^ "Briefwechsel zur Nationalhymne 1952". Bundesministerium des Innern (in German). 6 May 1952. Retrieved 1 December 2009.

- ^ http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F1FmJvSDTF4

- ^ Geisler, p.72.

- ^ a b Malzahn, Claus Christian (24 June 2006). "Deutsche Nationalhymne: 'Die blödsinnigste Parole der Welt'". Der Spiegel (in German). Retrieved 1 December 2009.

- ^ "Germans Stop Humming, Start Singing National Anthem". Deutsche Welle. 24 June 2006. Retrieved 2 March 2010.

- ^ Geisler p.75.

- ^ Rockwell, John (21 February 1979). "Cabaret: Nico is back". The New York Times.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Hesselmann, Markus (7 December 2006). "Völker, hört die Fanale!". Der Tagesspiegel (in German). Retrieved 1 December 2009.

- ^ Schiller, Mike (6 December 2007). "Rev. of Laibach, Volk". PopMatters. Retrieved 1 December 2009.

- ^ "Die slowenische Band Laibach stellte in der Arena ihr Album Volk vor" (subscription only). Märkische Allgemeine (in German). 21 July 2009. Retrieved 1 December 2009.

- ^ "Rockzanger Pete Doherty schoffeert Duitsers". Radio Netherlands Worldwide (in Dutch). 29 November 2009. Retrieved 1 December 2009.