Libya

Libya ليبيا Lībyā | |

|---|---|

Seal of the National Transitional Council | |

| |

| Capital | Tripoli |

| Official languages | Arabic[b] |

| Spoken languages | Libyan Arabic, other Arabic dialects, Berber |

| Demonym(s) | Libyan |

| Government | Provisional government |

| Mustafa Abdul Jalil | |

| Abdul Hafiz Ghoga | |

| Mahmoud Jibril | |

| Independence | |

• Relinquished by Italy | 10 February 1947 |

24 December 1951 | |

• Liberation day from Gaddafi regime | 23 October 2011 |

| Area | |

• Total | 1,759,541 km2 (679,363 sq mi) (17th) |

• Water (%) | Negligible surface water, reservoirs of water underground. |

| Population | |

• 2011 estimate | 6,6 million[1][2] (102nd) |

• 2006 census | 5,670,688[b] |

• Density | 3.6/km2 (9.3/sq mi) (218th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2010 estimate |

• Total | $90.841 billion[3] |

• Per capita | $13,846[3] |

| GDP (nominal) | 2010 estimate |

• Total | $71.336 billion[3] |

• Per capita | $10,873[3] |

| HDI (2010) | Error: Invalid HDI value (53rd) |

| Currency | Dinar (LYD) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| Drives on | right |

| Calling code | 218 |

| ISO 3166 code | LY |

| Internet TLD | .ly |

a. ^ Libyan Arabic and other varieties. Berber languages in certain low-populated areas. The official language is simply identified as "Arabic" (Constitutional Declaration, article 1).

b. ^ Included 350,000 foreigners | |

Libya (Template:Lang-ar Lībyā) is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to the east, Sudan to the southeast, Chad and Niger to the south, and Algeria and Tunisia to the west.

With an area of almost 1.8 million square kilometres (700,000 sq mi), Libya is the fourth largest country in Africa by area, and the 17th largest in the world.[5] The largest city, Tripoli, is home to 1.7 million of Libya's 6.4 million people. The three traditional parts of the country are Tripolitania, Fezzan and Cyrenaica.

In 2009 Libya had the highest HDI in Africa and the fourth highest GDP (PPP) per capita in Africa, behind Seychelles, Equatorial Guinea and Gabon. Libya has the 10th-largest proven oil reserves of any country in the world and the 17th-highest petroleum production.[6]

Libya lacks a formally constituted government and is loosely administrated by a coalition of rebel groups known as the National Transitional Council that came together during 2011 to give local leadership to the forces seeking to overthrow the previous government, known as the Great Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya (Arabic: الجماهيرية العربية الليبية الشعبية الاشتراكية العظمى al-Jamāhīriyyah al-‘Arabiyyah al-Lībiyyah ash-Sha‘biyyah al-Ishtirākiyyah al-‘Uẓmá). The civil war of February to October 2011 and the collapse of the Great Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya overturned a system of governance that had been in power for more than 40 years, resulting in the nation entering a leadership vacuum lacking any formal government structure. Rivalries, factional divisions and disagreements between so called rebel groups both within and seperate to the NTC emerged prior to the killing of Muammar Gaddafi and the crushing of the previous government and legislative structure of the nation. The leadership of any formalised government that may emerge in Libya remains a murky and confused matter. [7]

History

Prehistory

Tens of thousands of years ago, the Sahara desert, which now covers roughly 90% of Libya, was lush with green vegetation. It was home to lakes, forests, diverse wildlife and a temperate Mediterranean climate. Archaeological evidence indicates that the coastal plain of Ancient Libya was inhabited by Neolithic peoples from as early as 8000 BC. These peoples were perhaps drawn by the climate, which enabled their culture to grow; the Ancient Libyans were skilled in the domestication of cattle and the cultivation of crops.[8]

Rock paintings and carvings at Wadi Mathendous and the mountainous region of Jebel Acacus are the best sources of information about prehistoric Libya, and the pastoralist culture that settled there. The paintings reveal that the Libyan Sahara contained rivers, grassy plateaus and an abundance of wildlife such as giraffes, elephants and crocodiles.

Pockets of the Berber populations still remain in most of modern Libya. Dispersal in Africa from the Atlantic coast to the Siwa Oasis in Egypt seems to have followed, due to climatic changes which caused increasing desertification. It is thought that the indigenous Libyan civilization of the Garamantes, based in Germa, originated from this time, or may have done so even earlier when the Sahara was still green. The Garamantes were a Saharan people of Berber origin who used an elaborate underground irrigation system, and founded a kingdom in the Fezzan area of modern-day Libya. They were probably present as tribal people in the Fezzan by 1000 BC, and were a local power in the Sahara between 500 BC and 500 AD. By the time of contact with the Phoenicians, the first of the Semitic civilizations to arrive in Libya from the East, the Lebu, Garamantes, Bebers and other tribes that lived in the Sahara were already well established.

Phoenician and Greek colonial era

The Phoenicians were the first to establish trading posts in Libya, when the merchants of Tyre (in present-day Lebanon) developed commercial relations with the Berber tribes and made treaties with them to ensure their cooperation in the exploitation of raw materials.[9][10] By the 5th century BCE, the greatest of the Phoenician colonies, Carthage, had extended its hegemony across much of North Africa, where a distinctive civilization, known as Punic, came into being. Punic settlements on the Libyan coast included Oea (later Tripoli), Libdah (later Leptis Magna) and Sabratha. These cities were in an area that was later called Tripolis, or "Three Cities", from which Libya's modern capital Tripoli takes its name.

In 630 BC, the Ancient Greeks colonized Eastern Libya and founded the city of Cyrene.[11] Within 200 years, four more important Greek cities were established in the area that became known as Cyrenaica: Barce (later Marj); Euhesperides (later Berenice, present-day Benghazi); Taucheira (later Arsinoe, present-day Tukrah); Balagrae (later Az Zawiya Al Bayda and Beda Littoria under Italian occupation, present-day Bayda);and Apollonia (later Susah), the port of Cyrene.[12] Together with Cyrene, they were known as the Pentapolis (Five Cities). Cyrene became one of the greatest intellectual and artistic centers of the Greek world, and was famous for its medical school, learned academies, and architecture. The Greeks of the Pentapolis resisted encroachments by the Egyptians from the East, as well as by the Carthaginians from the West, but in 525 BC the Persian army of Cambyses II overran Cyrenaica, which for the next two centuries remained under Persian or Egyptian rule. Alexander the Great was greeted by the Greeks when he entered Cyrenaica in 331 BC, and Eastern Libya again fell under the control of the Greeks, this time as part of the Ptolemaic Kingdom. Later, a federation of the Pentapolis was formed that was customarily ruled by a king drawn from the Ptolemaic royal house.

Roman era

After the fall of Carthage the Romans did not occupy immediately Tripolitania (the region around Tripoli), but left it under control of the kings of Numidia, until the coastal cities asked and obtained its protection.[13] Ptolemy Apion, the last Greek ruler, bequeathed Cyrenaica to Rome, which formally annexed the region in 74 BC and joined it to Crete as a Roman province. During the Roman civil wars Tripolitania (still not formally annexed) and Cyrenaica sustained Pompey and Marc Antony against respectively Caesar and Octavian.[13][14] The Romans completed the conquest of the region under Augustus, occupying northern Fezzan ("Fasania") with Cornelius Balbus Minor.[15] As part of the Africa Nova province, Tripolitania was prosperous,[13] and reached a golden age in the 2nd and 3rd centuries, when the city of Leptis Magna, home to the Severian dynasty, was at its height.[13] On the other side, Cyrenaica's first Christian communities were established by the time of the Emperor Claudius[14] but was heavily devastated during the Kitos War,[16] and, although repopulated by Trajan with military colonies,[16] from then started its decadence.[14] Regardless, for more than 400 years Tripolitania and Cyrenaica were part of a cosmopolitan state whose citizens shared a common language, legal system, and Roman identity. Roman ruins like those of Leptis Magna and Sabratha, extant in present-day Libya, attest to the vitality of the region, where populous cities and even smaller towns enjoyed the amenities of urban life—the forum, markets, public entertainments, and baths—found in every corner of the Roman Empire. Merchants and artisans from many parts of the Roman world established themselves in North Africa, but the character of the cities of Tripolitania remained decidedly Punic and, in Cyrenaica, Greek. Tripolitania was a major exporter of olive oil,[17] as well as a center for the trade of ivory and wild animals[17] conveyed to the coast by the Garamantes, while Cyrenaica remained an important source of wines, drugs, and horses. The bulk of the population in the countryside consisted of Berber farmers, who in the west were thoroughly "romanized" in language and customs.[18] Until the 10th century the African Romance remained in use in some Tripolitanian areas, mainly near the Tunisian border.[19]

The decline of the Roman Empire saw the classical cities fall into ruin, a process hastened by the Vandals' destructive sweep though North Africa in the 5th century. The region's prosperity had shrunk under Vandal domination, and the old Roman political and social order, disrupted by the Vandals, could not be restored. In outlying areas neglected by the Vandals, the inhabitants had sought the protection of tribal chieftains and, having grown accustomed to their autonomy, resisted re-assimilation into the imperial system.

When the Empire returned (now as East Romans) as part of Justinian's reconquests of the 6th century, efforts were made to strengthen the old cities, but it was only a last gasp before they collapsed into disuse. Cyrenaica, which had remained an outpost of the Byzantine Empire during the Vandal period, also took on the characteristics of an armed camp. Unpopular Byzantine governors imposed burdensome taxation to meet military costs, while the towns and public services—including the water system—were left to decay. Byzantine rule in Africa did prolong the Roman ideal of imperial unity there for another century and a half however, and prevented the ascendancy of the Berber nomads in the coastal region. By the beginning of the 7th century, Byzantine control over the region was weak, Berber rebellions were becoming more frequent, and there was little to oppose Muslim invasion.

Arab Islamic rule 642–1551

Tenuous Byzantine control over Libya was restricted to a few poorly defended coastal strongholds, and as such, the Arab horsemen who first crossed into the Pentapolis of Cyrenaica in September 642 AD encountered little resistance. Under the command of 'Amr ibn al-'As, the armies of Islam conquered Cyrenaica, and renamed the Pentapolis, Barqa. They took also Tripoli, but after destroying the Roman walls of the city and getting a tribute they withdrew.[20] In 647 an army of 40,000 Arabs, led by Abdullah ibn Saad, the foster-brother of Caliph Uthman, penetrated deep into Western Libya and took Tripoli from the Byzantines definitively.[20] From Barqa, the Fezzan (Libya's Southern region) was conquered by Uqba ibn Nafi in 663 and Berber resistance was overcome. During the following centuries Libya came under the rule of several Islamic dynasties, under various levels of autonomy from Ummayad, Abbasid and Fatimid caliphates of the time. Arab rule was easily imposed in the coastal farming areas and on the towns, which prospered again under Arab patronage. Townsmen valued the security that permitted them to practice their commerce and trade in peace, while the Punicized farmers recognized their affinity with the Semitic Arabs to whom they looked to protect their lands. In Cyrenaica, Monophysite adherents of the Coptic Church had welcomed the Muslim Arabs as liberators from Byzantine oppression. The Berber tribes of the hinterland accepted Islam, however they resisted Arab political rule.

For the next several decades, Libya was under the purview of the Ummayad Caliph of Damascus until the Abbasids overthrew the Ummayads in 750, and Libya came under the rule of Baghdad. When Caliph Harun al-Rashid appointed Ibrahim ibn al-Aghlab as his governor of Ifriqiya in 800, Libya enjoyed considerable local autonomy under the Aghlabid dynasty. The Aghlabids were amongst the most attentive Islamic rulers of Libya; they brought about a measure of order to the region, and restored Roman irrigation systems, which brought prosperity to the area from the agricultural surplus. By the end of the 9th century, the Shiite Fatimids controlled Western Libya from their capital in Mahdia, before they ruled the entire region from their new capital of Cairo in 972 and appointed Bologhine ibn Ziri as governor. During Fatimid rule, Tripoli thrived on the trade in slaves and gold brought from the Sudan and on the sale of wool, leather, and salt shipped from its docks to Italy in exchange for wood and iron goods. Ibn Ziri's Berber Zirid Dynasty ultimately broke away from the Shiite Fatimids, and recognised the Sunni Abbasids of Baghdad as rightful Caliphs. In retaliation, the Fatimids brought about the migration of as many as 200,000 families from two Bedouin tribes, the Banu Sulaym and Banu Hilal to North Africa—this act completely altered the fabric of Libyan cities, and cemented the cultural and linguistic Arabisation of the region.[13] Ibn Khaldun noted that the lands ravaged by Banu Hilal invaders had become completely arid desert.[21]

After the subsequent social unrest during Zirid rule, the coast of Libya was weakened and invaded by the Normans of Sicily.[22] It was not until 1174 that the Ayyubid Sharaf al-Din Qaraqush reconquered Tripoli from European rule with an army of Turks and Bedouins. Afterward, a viceroy from the Almohads, Muhammad ibn Abu Hafs, ruled Libya from 1207 to 1221 before the later establishment of a Tunisian Hafsid dynasty[22] independent from the Almohads. The Hafsids ruled Tripolitania for nearly 300 years, and established significant trade with the city-states of Europe. Hafsid rulers also encouraged art, literature, architecture and scholarship. Ahmad Zarruq was one of the most famous Islamic scholars to settle in Libya, and did so during this time. By the 16th century however, the Hafsids became increasingly caught up in the power struggle between Spain and the Ottoman Empire. After a successful invasion of Tripoli by Habsburg Spain in 1510,[22] and its handover to the Knights of St. John, the Ottoman admiral Sinan Pasha finally took control of Libya in 1551.[22]

Ottoman regency 1551–1911

After a successful invasion by the Habsburgs of Spain in the early 16th century, Charles V entrusted its defense to the Knights of St. John in Malta. Lured by the piracy that spread through the Maghreb coastline, adventurers such as Barbarossa and his successors consolidated Ottoman control in the central Maghreb. The Ottoman Turks conquered Tripoli in 1551 under the command of Sinan Pasha. In the next year his successor Turgut Reis was named the Bey of Tripoli and later Pasha of Tripoli in 1556. As Pasha, he adorned and built up Tripoli, making it one of the most impressive cities along the North African coast.[23] By 1565, administrative authority as regent in Tripoli was vested in a pasha appointed directly by the sultan in Constantinople. In the 1580s, the rulers of Fezzan gave their allegiance to the sultan, and although Ottoman authority was absent in Cyrenaica, a bey was stationed in Benghazi late in the next century to act as agent of the government in Tripoli.[14]

In time, real power came to rest with the pasha’s corps of janissaries, a self-governing military guild, and in time the pasha’s role was reduced to that of ceremonial head of state.[22] Mutinies and coups were frequent, and in 1611 the deys staged a coup against the pasha, and Dey Sulayman Safar was appointed as head of government. For the next hundred years, a series of deys effectively ruled Tripolitania, some for only a few weeks, and at various times the dey was also pasha-regent. The regency governed by the dey was autonomous in internal affairs and, although dependent on the sultan for fresh recruits to the corps of janissaries, his government was left to pursue a virtually independent foreign policy as well. The two most important Deys were Mehmed Saqizli (r. 1631–49) and Osman Saqizli (r. 1649–72), both also Pasha, who ruled effectively the region.[24] The latter conquered also Cyrenaica.[24]

Tripoli was the only city of size in Ottoman Libya (then known as Tripolitania Eyalet) at the end of the 17th century and had a population of about 30,000. The bulk of its residents were Moors, as city-dwelling Arabs were then known. Several hundred Turks and renegades formed a governing elite, a large portion of which were kouloughlis (lit. sons of servants—offspring of Turkish soldiers and Arab women); they identified with local interests and were respected by locals. Jews and Moriscos were active as merchants and craftsmen and a small number of European traders also frequented the city. European slaves and large numbers of enslaved blacks transported from Sudan were also a feature of everyday life in Tripoli. In 1551, Turgut Reis enslaved almost the entire population of the Maltese island of Gozo, some 6,300 people, sending them to Libya.[25] The most pronounced slavery activity involved the enslavement of black Africans who were brought via trans-Saharan trade routes. Even though the slave trade was officially abolished in Tripoli in 1853, in practice it continued until the 1890s.[26]

Lacking direction from the Ottoman government, Tripoli lapsed into a period of military anarchy during which coup followed coup and few deys survived in office more than a year. One such coup was led by Turkish officer Ahmed Karamanli.[24] The Karamanlis ruled from 1711 until 1835 mainly in Tripolitania, but had influence in Cyrenaica and Fezzan as well by the mid 18th century. Ahmed was a Janissary and popular cavalry officer.[24] He murdered the Ottoman Dey of Tripolitania and seized the throne in 1711.[24] After persuading Sultan Ahmed III to recognize him as governor, Ahmed established himself as pasha and made his post hereditary. Though Tripolitania continued to pay nominal tribute to the Ottoman padishah, it otherwise acted as an independent kingdom. Ahmed greatly expanded his city's economy, particularly through the employment of corsairs (pirates) on crucial Mediterranean shipping routes; nations that wished to protect their ships from the corsairs were forced to pay tribute to the pasha. Ahmad's successors proved to be less capable than himself, however, the region's delicate balance of power allowed the Karamanli to survive several dynastic crises without invasion. The Libyan Civil War of 1791–1795 occurred in those years. In 1793, Turkish officer Ali Benghul deposed Hamet Karamanli and briefly restored Tripolitania to Ottoman rule. However, Hamet's brother Yusuf (r. 1795–1832) reestablished Tripolitania's independence.

In the early 19th century war broke out between the United States and Tripolitania, and a series of battles ensued in what came to be known as the Barbary Wars. By 1819, the various treaties of the Napoleonic Wars had forced the Barbary states to give up piracy almost entirely, and Tripolitania's economy began to crumble. As Yusuf weakened, factions sprung up around his three sons; though Yusuf abdicated in 1832 in favor of his son Ali II, civil war soon resulted. Ottoman Sultan Mahmud II sent in troops ostensibly to restore order, but instead deposed and exiled Ali II, marking the end of both the Karamanli dynasty and an independent Tripolitania.[27] Anyway, order was not recovered easily, and the revolt of the Libyan under Abd-El-Gelil and Gûma ben Khalifa lasted until the death of the latter in 1858.[27]

The second period of direct Ottoman rule saw administrative changes, and what seemed as greater order in the governance of the three provinces of Libya. It would not be long before the Scramble for Africa and European colonial interests set their eyes on the marginal Turkish provinces of Libya. Reunification came about through the unlikely route of an invasion (Italo-Turkish War, 1911–1912) and occupation starting from 1911 when Italy simultaneously turned the three regions into colonies.[28]

Italian colonial era and World War II 1911–1951

From 1912 to 1927, the territory of Libya was known as Italian North Africa. From 1927 to 1934, the territory was split into two colonies, Italian Cyrenaica and Italian Tripolitania, run by Italian governors. Some 150,000 Italians settled in Libya, constituting roughly 20% of the total population.[29]

In 1934, Italy adopted the name "Libya" (used by the Greeks for all of North Africa, except Egypt) as the official name of the colony (made up of the three provinces of Cyrenaica, Tripolitania and Fezzan). Idris al-Mahdi as-Senussi (later King Idris I), Emir of Cyrenaica, led Libyan resistance to Italian occupation between the two world wars. Ilan Pappé estimates that between 1928 and 1932 the Italian military "killed half the Bedouin population (directly or through disease and starvation in camps)."[30] Italian historian Gentile sets to about fifty thousands the number of victims of the repression.[31]

From 1943 to 1951, Tripolitania and Cyrenaica were under British administration, while the French controlled Fezzan. In 1944, Idris returned from exile in Cairo but declined to resume permanent residence in Cyrenaica until the removal of some aspects of foreign control in 1947. Under the terms of the 1947 peace treaty with the Allies, Italy relinquished all claims to Libya.[32]

Independence and the Kingdom of Libya 1951–1969

On November 21, 1949, the UN General Assembly passed a resolution stating that Libya should become independent before January 1, 1952. Idris represented Libya in the subsequent UN negotiations. On December 24, 1951, Libya declared its independence as the United Kingdom of Libya, a constitutional and hereditary monarchy under King Idris, Libya's first and only monarch.

1951 also saw the enactment of the Libyan Constitution. The Libyan National Assembly drafted the Constitution and passed a resolution accepting it in a meeting held in the city of Benghazi on Sunday, 6th Muharram, Hegiras 1371: October 7, 1951. Mohamed Abulas’ad El-Alem, President of the National Assembly and the two Vice-Presidents of the National Assembly, Omar Faiek Shennib and Abu Baker Ahmed Abu Baker executed and submitted the Constitution to King Idris following which it was published in the Official Gazette of Libya.

The enactment of the Libyan Constitution was significant in that it was the first piece of legislation to formally entrench the rights of Libyan citizens following the post-war creation of the Libyan nation state. Following on from the intense UN debates during which Idris had argued that the creation of a single Libyan state would be of benefit to the regions of Tripolitania, Fezzan, and Cyrenaica, the Libyan government was keen to formulate a constitution which contained many of the entrenched rights common to European and North American nation states. Though, not creating a secular state - Article 5 proclaims Islam the religion of the State - the Libyan Constitution did formally set out rights such as equality before the law as well as equal civil and political rights, equal opportunities, and an equal responsibility for public duties and obligations, "without distinction of religion, belief, race, language, wealth, kinship or political or social opinions" (Article 11).

The discovery of significant oil reserves in 1959 and the subsequent income from petroleum sales enabled one of the world's poorest nations to establish an extremely wealthy state. Although oil drastically improved the Libyan government's finances, resentment among some factions began to build over the increased concentration of the nation's wealth in the hands of King Idris. This discontent mounted with the rise of Nasserism and Arab nationalism throughout North Africa and the Middle East, so while the continued presence of Americans, Italians and British in Libya aided in the increased levels of wealth and tourism following WWII, it was seen by some as a threat.

During this period, Britain was involved in extensive engineering projects in Libya and was also the country's biggest supplier of arms. The United States also maintained the large Wheelus Air Base in Libya.

Libya under Colonel Muammar al-Gaddafi 1969–2011

On 1 September 1969, a small group of military officers led by the 27 year old army officer Muammar Gaddafi staged a coup d'état against King Idris, launching the Libyan Revolution.[33] Gaddafi was referred to as the "Brother Leader and Guide of the Revolution" in government statements and the official Libyan press.[34]

On the birthday of the Prophet Muhammad in 1973, Gaddafi delivered a "Five-Point Address". He announced the suspension of all existing laws and the implementation of Sharia. He said that the country would be purged of the "politically sick". A "people's militia" would "protect the revolution". There would be an administrative revolution, and a cultural revolution. Gaddafi set up an extensive surveillance system. 10 to 20 percent of Libyans work in surveillance for the Revolutionary committees. The surveillance takes place in government, in factories, and in the education sector.[35] Gaddafi executed dissidents publicly and the executions were often rebroadcast on state television channels.[35][36] Gaddafi employed his network of diplomats and recruits to assassinate dozens of critical refugees around the world. Amnesty International listed at least 25 assassinations between 1980 and 1987.[35][37]

In 1977, Libya officially became the "Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya". Later that same year, Gaddafi ordered an artillery strike on Egypt in retaliation against Egyptian President Anwar Sadat's intent to sign a peace treaty with Israel. Sadat's forces triumphed easily in a four-day border war that came to be known as the Libyan-Egyptian War, leaving over 400 Libyans dead and Gaddafi's armored divisions in disarray.

In February 1977, Libya started delivering military supplies to Goukouni Oueddei and the People's Armed Forces in Chad. The Chadian–Libyan conflict began in earnest when Libya's support of rebel forces in northern Chad escalated into an invasion. Hundreds of Libyans lost their lives in the war against Tanzania, when Gaddafi tried to save his friend Idi Amin. Gaddafi financed various other groups from anti-nuclear movements to Australian trade unions.[38]

Much of the country’s income from oil, which soared in the 1970s, was spent on arms purchases and on sponsoring dozens of paramilitaries and terrorist groups around the world.[38][39][40][41] An airstrike failed to kill Gaddafi in 1986. Libya was finally put under United Nations sanctions after the bombing of a commercial flight killed hundreds of travelers.

Gaddafi assumed the honorific title of "King of Kings of Africa" in 2008 as part of his campaign for a United States of Africa.[42] By the early 2010s, in addition to attempting to assume a leadership role in the African Union, Libya was also viewed as having formed closer ties with Italy, one of its former colonial rulers, than any other country in the European Union.[43]

The eastern parts of the country have been 'ruined' due to Gaddafi's economic theories, according to The Economist.[44][45]

2011 revolution and interim government

After popular movements overturned the rulers of Tunisia and Egypt, its immediate neighbors to the west and east, Libya experienced a full-scale revolt beginning on 17 February 2011.[46][47] By 20 February, the unrest had spread to Tripoli. In the early hours of 21 February 2011, Saif al-Islam Gaddafi, oldest son of Muammar Gaddafi, spoke on Libyan television of his fears that the country would fragment and be replaced by "15 Islamic fundamentalist emirates" if the uprising engulfed the entire state. He warned that the country's economic wealth and recent prosperity was at risk; admitted that "mistakes had been made" in quelling recent protests; and announced that a constitutional convention would begin on 23 February. Shortly after this speech, the Libyan Ambassador to India announced on BBC Radio 5 Live that he had resigned in protest at the "massacre" of protesters.

Gaddafi appeared on Libyan state TV to deny the rumors that he had fled Libya, which had been voiced by the United Kingdom's foreign minister, William Hague. Gaddafi said, "I want to show that I'm in Tripoli and not in Venezuela. Do not believe the (TV) channels belonging to stray dogs."[48] His government also portrayed the recent rebellion as being engineered by Western elements and Israel, and was suspected of manipulating the Libyan news media through planted reports in newspapers and television.[49] Two Libyan Air Force colonels flew their Mirage F1D jets to Malta and defected, claiming they refused orders to bomb protesters.[50][51] The military of Russia claimed it could not verify a single airstrike against protesters had taken place since the unrest began.[52]

By early March 2011, much of Libya had tipped out of Gaddafi's control, coming under the control of a coalition of opposition forces, including soldiers who decided to support the rebels. Pro-Gaddafi forces were able to respond militarily to rebel pushes in Western Libya and launched a counterattack on the strategic coastal towns of Ras Lanuf and Brega.[53] The town of Zawiya, 48 kilometres (30 mi) from Tripoli, was bombarded by planes and tanks and seized by pro-Gaddafi troops, "exercising a level of brutality not yet seen in the conflict."[54] Eastern Libya, centered on the second city and vital port of Benghazi, was said to be firmly in the hands of the opposition, while Tripoli and its environs remained in dispute.[55][56][57]

However in several public appearances, Gaddafi threatened to destroy the protest movement, and Al Jazeera and other agencies reported his government was arming pro-Gaddafi militiamen to kill protesters and defectors against the regime in Tripoli.[58] Organs of the United Nations, including United Nations Secretary General Ban Ki-moon[59] and the United Nations Human Rights Council, condemned the crackdown as violating international law, with the latter body expelling Libya outright in an unprecedented action urged by Libya's own delegation to the UN.[60][61] The United States imposed economic sanctions against Libya,[62] followed shortly by Australia,[63] Canada[64] and the United Nations Security Council, which also voted to refer Gaddafi and other government officials to the International Criminal Court for investigation.[65][66]

On 27 February 2011, the National Transitional Council was established under the stewardship of Mustafa Abdul Jalil, Gaddafi's former justice minister, to administer the areas of Libya under rebel control. This marked the first serious effort to organize the broad-based opposition to the Gaddafi regime. While the council was based in Benghazi, it claimed Tripoli as its capital.[67] Hafiz Ghoga, a human rights lawyer, later assumed the role of spokesman for the council.[68] On 10 March 2011, France became the first state to recognize the National Libyan Council as the country's legitimate government.

On 17 March 2011 the United Nations Security Council passed Resolution 1973 with a 10–0 vote and five abstentions. The resolution sanctioned the establishment a no-fly zone and the use of "all means necessary" to protect civilians within Libya.[69]

Shortly afterwards, Libyan Foreign Minister Moussa Koussa stated that "Libya has decided an immediate ceasefire and an immediate halt to all military operations".[70] However, attacks against insurgent strongholds appear to have continued despite this claim.

On 19 March 2011, the first Allied act to secure the no-fly zone began when French military jets entered Libyan airspace on a reconnaissance mission heralding attacks on enemy targets.[71] Allied military action to enforce the ceasefire commenced the same day when a French aircraft opened fire and destroyed a vehicle on the ground. French jets also destroyed five tanks belonging to the Gaddafi regime.[72] The United States and United Kingdom launched attacks on over 20 "integrated air defense systems" using more than 110 Tomahawk cruise missiles during operations Odyssey Dawn and Ellamy.[73]

On 27 June 2011, the International Criminal Court issued an arrest warrant for Gaddafi, alleging that Gaddafi had been personally involved in planning and implementing "a policy of widespread and systematic attacks against civilians and demonstrators and dissidents".[74]

By 22 August 2011, rebel fighters had entered Tripoli and occupied Martyrs' Square.[75] Meanwhile, Gaddafi asserted that he was still in Libya and would not concede power to the rebels.[75]

On 16 September 2011 the U.N. General Assembly approved a request from the National Transitional Council to accredit envoys of the country’s interim controlling body as Tripoli’s sole representatives at the UN, effectively recognising the National Transitional Council as the legitimate holder of that country’s UN seat. [76][77]

The National Transitional Council postponed the formation of a caretaker government on several occasions during the period prior to the killing Muammar Gaddafi in Sirte on 20 October 2011. They had been unable to agree on many issues, including that of a line up of potential ministerial positions. Mustafa Abdul Jalil (Arabic: مصطفى عبد الجليل), heads the executive board of the rebels' National Transitional Council and is generally considered to be the principal leadership figure, however in late October 2011 Mahmoud Jibril announced he was quitting, commenting "we have moved into a political struggle with no boundaries". The National Transitional Council had still failed to form a caretaker government in Libya at the time of the killing of Muammar Gaddafi on 21 October 2011. [78]

The last bastion of Gaddafi's rule, the coastal city of Sirte, fell to anti-Gaddafi fighters on 21 October after a momentous battle. Muammar Gaddafi was shot and killed.[79][80]

Naming of Libya

The National Transitional Council, established in 2011, refers to the state as simply "Libya", but there is some evidence that in the beginning they also used the term "Libyan Republic"[81][82] (Template:Lang-ar al-Jumhūriyyah al-Lībiyyah). In late August 2011, Bosnia and Herzegovina used the term in its formal recognition of the NTC.[83]

The name Libya (/ˈlɪbiə/ or /ˈlɪbjə/; Template:Lang-ar Līb(i)yā [ˈliːbⁱjaː] ; Libyan Arabic: [ˈliːbjæ] ) was introduced in 1934 for Italian Libya, after the historical name for Northwest Africa, from Greek Λιβύη (Libúē).

Italian Libya united the provinces of Tripolitania, Cyrenaica (Barca) and Fezzan under the name, based on earlier use in 1903 by Italian geographer Federico Minutilli,[84] and by the Italian government in its "Regio Decreto di Annessione" (Royal Decree of Annexation) of the Ottoman provinces of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica dating November 5, 1911.[84]

Libya gained independence in 1951 as the United Libyan Kingdom (Template:Lang-ar al-Mamlakah al-Lībiyyah al-Muttaḥidah), changing its name to the Kingdom of Libya (Template:Lang-ar al-Mamlakah al-Lībiyyah) in 1963.[85] Following a coup d'état in 1969, the name of the state was changed to the Libyan Arab Republic (Template:Lang-ar al-Jumhūriyyah al-‘Arabiyyah al-Lībiyyah).

From 1977 to 2011, Libya was known as the "Libyan Arab Jamahiriya" at the United Nations. The official name during this period was "Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya" from 1977 to 1986, and "Great Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya" (Template:Lang-ar al-Jamāhīriyyah al-‘Arabiyyah al-Lībiyyah ash-Sha‘biyyah al-Ishtirākiyyah al-‘Uẓmá ) from 1986 to 2011.

Geography

Libya extends over 1,759,540 square kilometres (679,362 sq mi), making it the 17th largest nation in the world by size. Libya is somewhat smaller than Indonesia in land area, and roughly the size of the US state of Alaska. It is bound to the north by the Mediterranean Sea, the west by Tunisia and Algeria, the southwest by Niger, the south by Chad and Sudan and to the east by Egypt. Libya lies between latitudes 19° and 34°N, and longitudes 9° and 26°E.

At 1,770 kilometres (1,100 mi), Libya's coastline is the longest of any African country bordering the Mediterranean.[87][88] The portion of the Mediterranean Sea north of Libya is often called the Libyan Sea. The climate is mostly dry and desertlike in nature. However, the northern regions enjoy a milder Mediterranean climate.

Natural hazards come in the form of hot, dry, dust-laden sirocco (known in Libya as the gibli). This is a southern wind blowing from one to four days in spring and autumn. There are also dust storms and sandstorms. Oases can also be found scattered throughout Libya, the most important of which are Ghadames and Kufra.

Libyan Desert

The Libyan Desert, which covers much of Libya, is one of the most arid places on earth.[33] In places, decades may pass without rain, and even in the highlands rainfall seldom happens, once every 5–10 years. At Uweinat, as of 2006 the last recorded rainfall was in September 1998.[89] There is a large depression, the Qattara Depression, just to the south of the northernmost scarp, with Siwa Oasis at its western extremity. The depression continues in a shallower form west, to the oases of Jaghbub and Jalu.

Likewise, the temperature in the Libyan desert can be extreme; on 13 September 1922 the town of 'Aziziya, which is located southwest of Tripoli, recorded an air temperature of 57.8 °C (136.0 °F), generally accepted as the highest recorded naturally occurring air temperature reached on Earth.[90]

There are a few scattered uninhabited small oases, usually linked to the major depressions, where water can be found by digging to a few feet in depth. In the west there is a widely dispersed group of oases in unconnected shallow depressions, the Kufra group, consisting of Tazerbo, Rebianae and Kufra.[89] Aside from the scarps, the general flatness is only interrupted by a series of plateaus and massifs near the centre of the Libyan Desert, around the convergence of the Egyptian-Sudanese-Libyan borders.

Slightly further to the south are the massifs of Arkenu, Uweinat and Kissu. These granite mountains are ancient, having formed long before the sandstones surrounding them. Arkenu and Western Uweinat are ring complexes very similar to those in the Aïr Mountains. Eastern Uweinat (the highest point in the Libyan Desert) is a raised sandstone plateau adjacent to the granite part further west.[89] The plain to the north of Uweinat is dotted with eroded volcanic features. With the discovery of oil in the 1950s also came the discovery of a massive aquifer underneath much of the country. The water in this aquifer pre-dates the last ice ages and the Sahara desert itself.[91] The country is also home to the Arkenu craters, double impact craters found in the desert.

Government and politics

The National Transitional Council is a political body formed to represent Libya by anti-Gaddafi forces during the 2011 Libyan civil war. On 5 March 2011 the council declared itself to be the "sole representative of all Libya". By October 2011 it had become recognized by 100 countries, including France,[92][93][94] Qatar,[95] Italy,[96] Germany,[97] Canada[98] and Turkey.[99] It is also supported by several other Arab[100] and European countries.[101] On September 16, the United Nations switched its official recognition to the NTC. The council formed an interim governing body, the Executive Board, on 23 March 2011 with Mahmoud Jibril as the Chairman.[102] The United States switched official recognition from the Gaddafi government to the National Transitional Council on 15 July 2011. The United Kingdom followed suit on 27 July 2011, expelling all Libyan government diplomats from the country before accrediting a National Transitional Council envoy to the Libyan Embassy in London.[103]

As the centre of the resistance against Gaddafi during the war, Benghazi, Libya's second city, served as the provisional seat for the NTC for the months following its creation.[104] On 25 August 2011, Finance Minister Ali Tarhouni announced that the NTC would move to Tripoli, which it claimed as the de jure capital of Libya, effective immediately.[105] However, as of early September 2011, many of the NTC's offices and ministers, including Chairman Mustafa Abdul Jalil, remain in Benghazi due to the eastern city's more stable security situation and established infrastructure.[106]

Foreign relations

Amidst the 2011 Libyan civil war, at least 100 countries, as of 18 October 2011[update], as well as multiple supranational organizations and partially recognized states, have formally switched their diplomatic recognition to the National Transitional Council.

Officials of the National Transitional Council have asked for foreign aid, including medical supplies,[107] money,[108] and weapons,[109] and have promised to pay off their debt to donor countries with oil deals[110] and frozen assets belonging to Gaddafi and his confidants[111] after the civil war ends. They have also suggested that countries that were early to offer recognition and countries participating in the international military intervention in Libya may receive more favorable oil contracts and trade deals.[112]

Kingdom of Libya

Libya's foreign policies have fluctuated since 1951. As a Kingdom, Libya maintained a definitively pro-Western stance, and was recognized as belonging to the conservative traditionalist bloc in the League of Arab States (the present-day Arab League), of which it became a member in 1953.[113] The government was also friendly towards Western countries such as the United Kingdom, United States, France, Italy, Greece, and established full diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union in 1955.

Although the government supported Arab causes, including the Moroccan and Algerian independence movements, it took little active part in the Arab-Israeli dispute or the tumultuous inter-Arab politics of the 1950s and early 1960s. The Kingdom was noted for its close association with the West, while it steered a conservative course at home.[114]

Libya under Gaddafi

After the 1969 coup, Muammar Gaddafi closed American and British bases and partly nationalized foreign oil and commercial interests in Libya.

Gaddafi was known for backing a number of leaders viewed as anathema to Westernization and political liberalism, including Ugandan President Idi Amin,[115] Central African Emperor Jean-Bedel Bokassa,[116][117] Ethiopian strongman Haile Mariam Mengistu,[117] Liberian President Charles Taylor,[118] and Yugoslav President Slobodan Milošević.[119]

Relations with the West were strained by a series of incidents for most of Gaddafi's rule,[120][121][122] including the killing of British policewoman Yvonne Fletcher, the bombing of a Berlin nightclub frequented by U.S. servicemen, and the bombing of Pan Am Flight 103, which led to UN sanctions in the 1990s, though by the late 2000s, the United States and other Western powers had normalised relations with Libya.[33]

Gaddafi's decision to abandon the pursuit of weapons of mass destruction after the Iraq War saw Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein overthrown and put on trial led to Libya being hailed as a success for Western soft power initiatives in the War on Terror.[123][124][125]

Human rights

According to the US Department of State’s annual human rights report for 2007, Libya’s authoritarian regime continued to have a poor record in the area of human rights.[126] Some of the numerous and serious abuses on the part of the government include poor prison conditions, arbitrary arrest and prisoners held incommunicado, and political prisoners held for many years without charge or trial. The judiciary is controlled by the government, and there is no right to a fair public trial. Libyans do not have the right to change their government. Freedom of speech, press, assembly, association, and religion are restricted. Independent human rights organizations are prohibited. Ethnic and tribal minorities suffer discrimination, and the state continues to restrict the labor rights of foreign jobs.

In May, 2010, Libya was elected by the UN General Assembly to a three-year term on the UN's Human Rights Council.[127] It was suspended from the Human Rights Council in March, 2011.[128]

Libya's human rights record was put in the spotlight in February 2011, due to the government's violent response to pro-democracy protesters, when it killed hundreds of demonstrators.[129]

In 2011, Freedom House rated both political rights and civil liberties in Libya as "7" (1 representing the most free and 7 the least free rating), and gave it the freedom rating of "Not Free".[130]

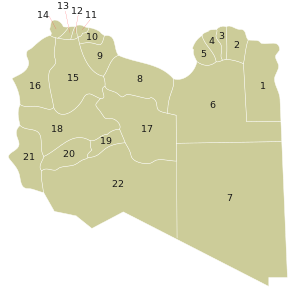

Administrative divisions and cities

Historically the area of Libya was considered three provinces (or states), Tripolitania in the northwest, Barka (Cyrenaica) in the east, and Fezzan in the southwest. It was the conquest by Italy in the Italo-Turkish War that united them in a single political unit. Under the Italians Libya, in 1934, was divided into four provinces and one territory (in the south): Tripoli, Misrata, Benghazi, Bayda, and the Territory of the Libyan Sahara.[131]

After independence, Libya was divided into three governorates (muhafazat)[132] and then in 1963 into ten governorates.[133][134] The governorates were legally abolished in February 1975, and nine "control bureaus" were set up to deal directly with the nine areas, respectively: education, health, housing, social services, labor, agricultural services, communications, financial services, and economy, each under their own ministry.[135] However, the courts and some other agencies continued to operate as if the governorate structure were still in place.[135] In 1983 Libya was split into forty-six districts (baladiyat), then in 1987 into twenty-five.[136][137][138] In 1995, Libya was divided into thirteen districts (shabiyah),[139] in 1998 into twenty-six districts, and in 2001 into thirty-two districts.[140] These were then further rearranged into twenty-two districts in 2007:

| Arabic | Transliteration | Pop (2006)[141] | Land area (km2) | Number (on map) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| البطنان | Butnan | 159,536 | 83,860 | 1 |

| درنة | Derna | 163,351 | 19,630 | 2 |

| الجبل الاخضر | Jabal al Akhdar | 206,180 | 7,800 | 3 |

| المرج | Marj | 185,848 | 10,000 | 4 |

| بنغازي | Benghazi | 670,797 | 43,535 | 5 |

| الواحات | Al Wahat | 177,047 | 6 | |

| الكفرة | Kufra | 50,104 | 483,510 | 7 |

| سرت | Sirte | 141,378 | 77,660 | 8 |

| مرزق | Murzuq | 78,621 | 349,790 | 22 |

| سبها | Sabha | 134,162 | 15,330 | 19 |

| وادي الحياة | Wadi al Hayaa | 76,858 | 31,890 | 20 |

| مصراتة | Misrata | 550,938 | 9 | |

| المرقب | Murqub | 432,202 | 10 | |

| طرابلس | Tripoli | 1,065,405 | 11 | |

| الجفارة | Jafara | 453,198 | 1,940 | 12 |

| الزاوية | Zawiya | 290,993 | 2,890 | 13 |

| النقاط الخمس | Nuqat al Khams | 287,662 | 5,250 | 14 |

| الجبل الغربي | Jabal al Gharbi | 304,159 | 15 | |

| نالوت | Nalut | 93,224 | 16 | |

| غات | Ghat | 23,518 | 72,700 | 21 |

| الجفرة | Jufra | 52,342 | 117,410 | 17 |

| وادي الشاطئ | Wadi al Shatii | 78,532 | 97,160 | 18 |

Libyan districts are further subdivided into Basic People's Congresses which act as townships or boroughs.

The following table shows the largest cities, in this case with population size being identical with the surrounding district (see above).

| No. | City | Population (2010)[142][143][144] |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tripoli | 1,800,000 |

| 2 | Benghazi | 650,000 |

| 3 | Misrata | 350,000 |

| 4 | Bayda | 250,000 |

| 5 | Zawiya | 200,000 |

Economy

The Libyan economy depends primarily upon revenues from the oil sector, which constitute practically all export earnings and about one-quarter of gross domestic product (GDP). The discovery of the oil and natural gas reserves in the country in 1959 led to the transformation of Libya's economy from a poor country to (then) Africa's richest. The World Bank defines Libya as an 'Upper Middle Income Economy', along with only seven other African countries.[145] In the early 1980s, Libya was one of the wealthiest countries in the world; its GDP per capita was higher than that of developed countries such as Italy, Singapore, South Korea, Spain and New Zealand.[146]

Today, high oil revenues and a small population give Libya one of the highest GDPs per capita in Africa and have allowed the Libyan state to provide an extensive level of social security, particularly in the fields of housing and education.[147] Many problems still beset Libya's economy however; unemployment is the highest in the region at 21%, according to the latest census figures.[148]

Compared to its neighbors, Libya enjoys a low level of both absolute and relative poverty. Libyan officials in the past six years have carried out economic reforms as part of a broader campaign to reintegrate the country into the global capitalist economy.[149] This effort picked up steam after UN sanctions were lifted in September 2003, and as Libya announced in December 2003 that it would abandon programs to build weapons of mass destruction.[150]

Libya has begun some market-oriented reforms. Initial steps have included applying for membership of the World Trade Organization, reducing subsidies, and announcing plans for privatization.[151] Authorities have privatized more than 100 government owned companies since 2003 in industries including oil refining, tourism and real estate, of which 29 are 100% foreign owned.[152] The non-oil manufacturing and construction sectors, which account for about 20% of GDP, have expanded from processing mostly agricultural products to include the production of petrochemicals, iron, steel and aluminum.

Climatic conditions and poor soils severely limit agricultural output, and Libya imports about 75% of its food.[149] Water is also a problem, with some 28% of the population not having access to safe drinking water in 2000.[153] The Great Manmade River project is tapping into vast underground aquifers of fresh water discovered during the quest for oil, and is intended to improve the country's agricultural output.

Under former prime ministers Shukri Ghanem and Baghdadi Mahmudi, Libya underwent a business boom, with initiatives to privatize many government-run industries. Many international oil companies returned to the country, including oil giants Shell and ExxonMobil.[154]

Tourism was on the rise, bringing increased demand for hotel accommodation and for capacity at airports such as Tripoli International. A multi-million dollar renovation of Libyan airports was approved in 2006 by the government to help meet such demands.[155] Previously, 130,000 people visited the country annually; the Libyan government hoped to increase this figure to 10,000,000 tourists. However there is little evidence to suggest the current administration is taking active steps to meet this figure. Libya has long been a notoriously difficult country for western tourists to visit due to stringent visa requirements. Since the 2011 protests there has been revived hope that an open society will encourage the return of tourists.[156] Saif al-Islam al-Gaddafi, the second-eldest son of Muammar Gaddafi, is involved in a green development project called the Green Mountain Sustainable Development Area, which seeks to bring tourism to Cyrene and to preserve Greek ruins in the area.[157]

In August 2011, Ahmed Jehani, head of the Libyan Stabilisation Team appointed by the rebel National Transition Council, estimated it would take at least 10 years to rebuild Libya's infrastructure. He also noted that Libya's infrastructure was in a poor state, even before the 2011 civil war due to "utter neglect" by Gaddafi's administration.[158]

Demographics

Fareed Zakaria said in 2011 that "The unusual thing about Libya is that it's a very large country with a very small population, but the population is actually concentrated very narrowly along the coast."[159] Population density is about 50 persons per km² (130/sq. mi.) in the two northern regions of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica, but falls to less than one person per km² (2.6/sq. mi.) elsewhere. Ninety percent of the people live in less than 10% of the area, primarily along the coast. About 88% of the population is urban, mostly concentrated in the three largest cities, Tripoli, Benghazi and Misrata. Libya has a population of about 6.5 million, around half of whom are under the age of 15. In 1984 the population reached 3.6 million and was growing at about 4% a year, one of the highest rates in the world. The 1984 population total was an increase from the 1.54 million reported in 1964.[160]

Native Libyans are primarily Arab or a mixture of Arab and Berber ethnicities. Among foreign residents, the largest groups are citizens of other African nations, including North Africans (primarily Egyptians), and Sub-Saharan Africans.[161] In 2011, there were also an estimated 60,000 Bangladeshis, 30,000 Chinese and 30,000 Filipinos in Libya.[162] Libya is home to a large illegal population which numbers more than one million, mostly Egyptians and Sub-Saharan Africans.[163] Libya has a small Italian minority. Previously, there was a visible presence of Italian settlers, but many left after independence in 1947 and many more left in 1970 after the accession of Muammar Gaddafi.[164]

The main language spoken in Libya is Arabic (Libyan dialect) by 95% of the Libyans, and Modern Standard Arabic is also the official language; the Berber languages spoken by 5% (i.e. Berber and Tuareg languages), which do not have official status, are spoken by Berbers and Tuaregs in the south part of the country beside Arabic language.[165] Berber speakers live above all in the Jebel Nafusa region (Tripolitania), the town of Zuwarah on the coast, and the city-oases of Ghadames, Ghat and Awjila. In addition, Tuaregs speak Tamahaq, the only known Northern Tamasheq language, also Toubou is spoken in some pockets in Qatroun village and Kufra city. Italian and English are sometimes spoken in the big cities, although Italian speakers are mainly among the older generation.

There are about 140 tribes and clans in Libya.[166] Family life is important for Libyan families, the majority of which live in apartment blocks and other independent housing units, with precise modes of housing depending on their income and wealth. Although the Libyan Arabs traditionally lived nomadic lifestyles in tents, they have now settled in various towns and cities.[167] Because of this, their old ways of life are gradually fading out. An unknown small number of Libyans still live in the desert as their families have done for centuries. Most of the population has occupations in industry and services, and a small percentage is in agriculture.

According to the World Refugee Survey 2008, published by the U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants, Libya hosted a population of refugees and asylum seekers numbering approximately 16,000 in 2007. Of this group, approximately 9,000 persons were from Palestine, 3,200 from Sudan, 2,500 from Somalia and 1,100 from Iraq.[168] Libya reportedly deported thousands of illegal entrants in 2007 without giving them the opportunity to apply for asylum. Refugees faced discrimination from Libyan officials when moving in the country and seeking employment.[168]

Education

Libya's population includes 1.7 million students, over 270,000 of whom study at the tertiary level.[169] Basic education in Libya is free for all citizens,[170] and compulsory to secondary level. The literacy rate is the highest in North Africa; over 82% of the population can read and write.[171]

After Libya's independence in 1951, its first university, the University of Libya, was established in Benghazi by royal decree.[172] In academic year 1975/76 the number of university students was estimated to be 13,418. As of 2004, this number has increased to more than 200,000, with an extra 70,000 enrolled in the higher technical and vocational sector.[169] The rapid increase in the number of students in the higher education sector has been mirrored by an increase in the number of institutions of higher education.

Since 1975 the number of universities has grown from two to nine and after their introduction in 1980, the number of higher technical and vocational institutes currently stands at 84 (with 12 public universities).[169] Libya's higher education is mostly financed by the public budget, although a small number of private institutions has been given accreditation lately. In 1998 the budget allocated for education represented 38.2% of the national budget.[172]

The main universities in Libya are:

- Al Fateh University (Tripoli)

- Garyounis University (Benghazi)

- Misrata University (Misrata)

- Omar Al-Mukhtar University (Bayda)

The main technology institutions are:

- The Higher Institute of Computer Technology Also known as The College of Computer Technology (Tripoli)

- The Higher Institute of Electronics (Tripoli)

Religion

By far the predominant religion in Libya is Islam with 97% of the population associating with the faith.[173] The vast majority of Libyan Muslims adhere to Sunni Islam, which provides both a spiritual guide for individuals and a keystone for government policy, but a minority (between 5 and 10%) adhere to Ibadism (a branch of Kharijism), above all in the Jebel Nefusa and the town of Zuwarah, west of Tripoli.

Before the 1930s, the Senussi Movement was the primary Islamic movement in Libya. This was a religious revival adapted to desert life. Its zawaaya (lodges) were found in Tripolitania and Fezzan, but Senussi influence was strongest in Cyrenaica. Rescuing the region from unrest and anarchy, the Senussi movement gave the Cyrenaican tribal people a religious attachment and feelings of unity and purpose.[174]

This Islamic movement, which was eventually destroyed by both Italian invasion and later the Gaddafi government,[174] was very conservative and somewhat different from the Islam that exists in Libya today. Gaddafi asserts that he is a devout Muslim, and his government is taking a role in supporting Islamic institutions and in worldwide proselytizing on behalf of Islam.[175] A Libyan form of Sufism is also common in parts of the country.[176]

Other than the overwhelming majority of Sunni Muslims, there are also small foreign communities of Christians. Coptic Orthodox Christianity, which is the Christian Church of Egypt, is the largest and most historical Christian denomination in Libya. There are over 60,000 Egyptian Copts in Libya, as they comprise over 1% of the population.[177][178] There are an estimated 40,000 Roman Catholics in Libya who are served by two Bishops, one in Tripoli (serving the Italian community) and one in Benghazi (serving the Maltese community). There is also a small Anglican community, made up mostly of African immigrant workers in Tripoli; it is part of the Anglican Diocese of Egypt.

Libya was until recent times the home of one of the oldest Jewish communities in the world, dating back to at least 300 BC.[179] In 1942 the Italian Fascist authorities set up forced labor camps south of Tripoli for the Jews, including Giado (about 3,000 Jews) and Gharyan, Jeren, and Tigrinna. In Giado some 500 Jews died of weakness, hunger, and disease. In 1942, Jews who were not in the concentration camps were heavily restricted in their economic activity and all men between 18 and 45 years were drafted for forced labor. In August 1942, Jews from Tripolitania were interned in a concentration camp at Sidi Azaz. In the three years after November 1945, more than 140 Jews were murdered, and hundreds more wounded, in a series of pogroms.[180] By 1948, about 38,000 Jews remained in the country. Upon Libya's independence in 1951, most of the Jewish community emigrated. (See History of the Jews in Libya.)

Culture

Libya is culturally similar to its neighboring Maghrebian states. Libyans consider themselves very much a part of a wider Arab community. The Libyan state tends to strengthen this feeling by considering Arabic as the only official language, and forbidding the teaching and even the use of the Berber language. Libyan Arabs have a heritage in the traditions of the nomadic Bedouin and associate themselves with a particular Bedouin tribe.

Libya boasts few theaters or art galleries.[181][182] For many years there have been no public theaters, and only a few cinemas showing foreign films. The tradition of folk culture is still alive and well, with troupes performing music and dance at frequent festivals, both in Libya and abroad.

The main output of Libyan television is devoted to showing various styles of traditional Libyan music. Tuareg music and dance are popular in Ghadames and the south. Libyan television programs are mostly in Arabic with a 30-minute news broadcast each evening in English and French. The government maintains strict control over all media outlets. A new analysis by the Committee to Protect Journalists has found Libya’s media the most tightly controlled in the Arab world.[183] To combat this, the government plans to introduce private media, an initiative intended to update the country's media.[184]

Many Libyans frequent the country's beach and they also visit Libya's archaeological sites—especially Leptis Magna, which is widely considered to be one of the best preserved Roman archaeological sites in the world.[185]

The nation's capital, Tripoli, boasts many museums and archives; these include the Government Library, the Ethnographic Museum, the Archaeological Museum, the National Archives, the Epigraphy Museum and the Islamic Museum. The Jamahiriya Museum, built in consultation with UNESCO, may be the country's most famous.[186]

Contemporary travel

The most common form of public transport between cities is the bus, but many people travel by automobile.[187] There are no railway services in Libya.[187]

Libyan cuisine

Libyan cuisine is generally simple, and is very similar to Sahara cuisine.[188] In many undeveloped areas and small towns, restaurants may be nonexistent, and food stores may be the only source to obtain food products.[188] Some common Libyan foods include couscous, bazeen, which is a type of unsweetened cake, and shurba, which is soup.[188] Libyan restaurants may serve international cuisine, or may serve simpler fare such as lamb, chicken, vegetable stew, potatoes and macaroni.[188] Alcohol consumption is illegal in the entire country.[189]

There are four main ingredients of traditional Libyan food: olives (and olive oil), palm dates, grains and milk.[190] Grains are roasted, ground, sieved and used for making bread, cakes, soups and bazeen. Dates are harvested, dried and can be eaten as they are, made into syrup or slightly fried and eaten with bsisa and milk. After eating, Libyans often drink black tea. This is normally repeated a second time (for the second glass of tea), and in the third round the tea is served with roasted peanuts or roasted almonds (mixed with the tea in the same glass).[190]

See also

Notes

- ^ CIA Factbook: "6,597,960 (July 2011 est.); country comparison to the world: 102; note: includes 166,510 non-nationals "

- ^ Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division (2009). "World Population Prospects, Table A.1" (PDF). 2008 revision. United Nations. Retrieved 2009-03-12.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c d "Libya". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 2011-09-26.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2010" (PDF). United Nations. 2010. Retrieved 2010-11-05.

- ^ U.N. Demographic Yearbook, (2003), "Demographic Yearbook (3) Pop., Rate of Pop. Increase, Surface Area & Density", United Nations Statistics Division. Retrieved July 15, 2006.

- ^ Annual Statistical Bulletin, (2004), "World proven crude oil reserves by country, 1980–2004", O.P.E.C.. Retrieved July 20, 2006.

- ^ David Kirkpatrick and Kereem Fahim (25 September 2011). "Former Rebels' Rivalries Hold Up Governing in Libya". New York Times. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ^ Federal Research Division of the Library of Congress, (1987), "Early History of Libya", U.S. Library of Congress. Retrieved July 11, 2006.

- ^ Herodotus, (c.430 BC), "'The Histories', Book IV.42–43" Fordham University, New York. Retrieved July 18, 2006.

- ^ Federal Research Division of the Library of Congress, (1987), "Tripolitania and the Phoenicians", U.S. Library of Congress. Retrieved July 11, 2006.

- ^ Federal Research Division of the Library of Congress, (1987), "Cyrenaica and the Greeks", U.S. Library of Congress. Retrieved July 11, 2006.

- ^ History of Libya The History Files, Retrieved September 29, 2011

- ^ a b c d e Bertarelli (1929), p. 202.

- ^ a b c d Bertarelli (1929), p. 417.

- ^ Bertarelli (1929), p. 382.

- ^ a b Rostovtzeff (1957), p. 364.

- ^ a b Rostovtzeff (1957), p. 335.

- ^ Heuser, Stephen, (July 24, 2005), "When Romans lived in Libya", The Boston Globe'.' Retrieved July 18, 2006.

- ^ Tadeusz Lewicki, "Une langue romane oubliée de l'Afrique du Nord. Observations d'un arabisant", Rocznik Orient. XVII (1958), pp. 415–480.

- ^ a b Bertarelli (1929), p. 278.

- ^ "Populations Crises and Population Cycles", Claire Russell and W.M.S. Russell.

- ^ a b c d e Bertarelli (1929), p. 203.

- ^ Naylor, Phillip Chiviges (2009). North Africa: a history from antiquity to the present. University of Texas Press. pp. 120–121. ISBN 0292719221, 9780292719224.

One of the most famous corsairs was Turghut (Dragut) (?–1565), who was of Greek ancestry and a protégé of Khayr al-Din. ... While pasha, he built up Tripoli and adorned it, making it one of the most impressive cities along the North African littoral.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ a b c d e Bertarelli (1929), p. 204.

- ^ "Christian Slaves, Muslim Masters: White Slavery in the Mediterranean, the Barbary Coast and Italy, 1500–1800". Robert Davis (2004) ISBN 1-4039-4551-9.

- ^ Lisa Anderson, "Nineteenth-Century Reform in Ottoman Libya", International Journal of Middle East Studies, Vol. 16, No. 3. (Aug., 1984), pp. 325–348.

- ^ a b Bertarelli (1929), p. 205.

- ^ Country Profiles, (May 16, 2006), "Timeline: Libya, a chronology of key events" BBC News. Retrieved July 18, 2006.

- ^ Libya, Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Ilan Pappé, The Modern Middle East. Routledge, 2005, ISBN 0-415-21409-2, p. 26.

- ^ "Un patriota della Cirenaica". retedue.rsi.ch. 2011-03-01. Retrieved 2011-03-24.

- ^ Hagos, Tecola W., (November 20, 2004), "Treaty Of Peace With Italy (1947), Evaluation And Conclusion", Ethiopia Tecola Hagos. Retrieved July 18, 2006.

- ^ a b c Salak, Kira. "Rediscovering Libya". National Geographic Adventure.

- ^ US Department of State's Background Notes, (November 2005) "Libya – History", U.S. Dept. of State. Retrieved July 14, 2006.

- ^ a b c Mohamed Eljahmi (2006). "Libiya and the U.S.: Qadhafi Unrepentant". The Middle East Quarterly.

- ^ Brian Lee Davis. Qaddafi, terrorism, and the origins of the U.S. attack on Libya.

- ^ The Middle East and North Africa 2003 (2002). Eur. p. 758

- ^ a b "A Rogue Returns". AIJAC. February 2003.[dead link]

- ^ "Endgame in Tripoli". The Economist. 2011-02-24.

- ^ Geoffrey Leslie Simons. Libya: the struggle for survival. p. 281.

- ^ St. John, Ronald Bruce (1 December 1992). "Libyan terrorism: the case against Gaddafi". Contemporary Review.

- ^ "Gaddafi: Africa's 'king of kings'". BBC News. 29 August 2008. Retrieved 2011-02-27.

- ^ Schlamp, Hans-Jürgen (25 February 2011). "Kissing the Hand of the Dictator: What Libya's Troubles Mean for Its Italian Allies". Der Spiegel. Retrieved 2011-02-27.

- ^ "A civil war beckons". The Economist. 2011-03-03.

- ^ "The liberated east – Building a new Libya". The Economist. 2011-02-24.

- ^ "Live Blog - Libya | Al Jazeera Blogs". Blogs.aljazeera.net. 2011-02-17. Retrieved 2011-02-23.

- ^ "News | Libya February 17th". Libyafeb17.com. Retrieved 2011-02-23.[dead link]

- ^ Black, Ian (21 February 2011). "Muammar Gaddafi Lashes Out as Power Slips Away". The Guardian. London: Guardian News and Media Ltd. Retrieved 2011-02-22.

{{cite news}}: Check|authorlink=value (help); External link in|authorlink= - ^ Mekay, Emad (23 February 2011). "One Libyan Battle Is Fought in Social and News Media". The New York Times. New York Times. Retrieved 2011-03-02.

- ^ Hooper, John; Black, Ian (21 February 2011). "Libya Defectors: Pilots Told to Bomb Protestors Flee to Malta". The Guardian. London: Guardian News and Media Ltd. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- ^ Carroll, Tom (21 February 2011). "Libya Revolution at Tipping Point as Gaddafi Jets Defect to Malta". Aquapour Global news Online. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- ^ ""Airstrikes in Libya did not take place" – Russian military — RT". Rt.com. Retrieved 2011-03-03.

- ^ Fahim, Kareem; Kirkpatrick, David D. (2011-03-09). ""Qaddafi Forces Batter Rebels in Strategic Refinery Town" – NYTimes". New York Times. Retrieved 2011-03-09.

- ^ The Independent, 9 March 2011 P.4

- ^ "Protesters march in Tripoli". Al Jazeera English. 28 February 2011. Retrieved 2011-03-01.

- ^ "Libya: France recognises rebels as government". BBC News. 10 March 2011.

- ^ The Guardian Live Blog. Retrieved 10 March 2011

- ^ "Gaddafi vows to crush protesters". Al Jazeera. 25 February 2011. Retrieved 2011-02-26.

- ^ "Ban Ki-moon blasts Gaddafi; calls situation dangerous". Hindustan Times. 24 February 2011. Retrieved 2011-02-26.

- ^ "Some backbone at the U.N." The Los Angeles Times. 26 February 2011. Retrieved 2011-02-26.

- ^ "Libya Expelled from UN Human Rights Council". Sofia News Agency. 2 March 2011. Retrieved 2011-03-02.

- ^ "US slaps sanctions on Libyan govt". Al Jazeera. 26 February 2011. Retrieved 2011-02-26.

- ^ "Australia imposes sanctions on Libya". The Sydney Morning Herald. 27 February 2011. Retrieved 2011-02-27.

- ^ "Canada imposes additional Libyan sanctions - Politics - CBC News". Cbc.ca. 27 February 2011. Retrieved 2011-02-28.

- ^ "UN Security Council orders sanctions against Libya". Monsters & Critics. 27 February 2011. Retrieved 2011-02-27.

- ^ "U.N. Security Council slaps sanctions on Libya". MSNBC. 26 February 2011. Retrieved 2011-02-27.

- ^ "Ex Libyan minister forms interim govt-report". LSE. 26 February 2011. Retrieved 2011-02-27.

- ^ Rahn, Will (27 February 2011). "Libyan rebels say they don't want foreign intervention". The Daily Caller. Retrieved 2011-03-01.

- ^ "Security Council authorizes 'all necessary measures' to protect civilians in Libya". United Nations-DPI/NMD - UN News Service Section. March 17, 2011. Retrieved March 30, 2011.

- ^ "Libya: Pro-Gaddafi forces 'to observe ceasefire'". BBC News. 18 March 2011.

- ^ Jonathan Marcus (2011-03-19). "'French military jets over Libya'". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2011-08-20.

- ^ Jonathan Marcus (2011-03-19). "'French military jets open fire in Libya'". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2011-08-20.

- ^ "Coalition launches Libya attacks". BBC. 19 March 2011. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- ^ Ian Black and David Smith in Tripoli (27 June 2011). "War crimes court issues Gaddafi arrest warrant | World news". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 2011-08-20.

- ^ a b Richburg, Keith B. (22 August 2011). The Washington Post http://www.washingtonpost.com/world/middle-east/libyan-rebels-converging-on-tripoli/2011/08/21/gIQAbF3RUJ_story.html?hpid=z1.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Jennifer Welsh (20 September 2011). "Recognizing States and Governments–A Tricky Business". Canadian International Council. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ^ National Transitional Council, Office of the Libyan Representative to the US (16 September 2011). "UN Recognizes Libya's NTC". Reuters. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ^ Vivienne Walt (19 October 2011). "In Tripoli, Libya's Interim Leader Says He Is Quitting". Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ^ Fahim, Kareem (20 October 2011). "Qaddafi Is Dead, Libyan Officials Say". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 October 2011.

- ^ Al Jazeera and agencies (21 October 2011). "Muammar Gaddafi killed as Sirte falls". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ^ "The Libyan Republic - The Interim Transitional National Council". Ntclibya.org. 2011-03-05. Retrieved 2011-03-10.

- ^ "Libyan rebels vow fight, even without no-fly zone". Reuters. 10 Mar 2011. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

- ^ "BIH Presidency recognizes interim National Council of Republic of Libya". EMG. 27 August 2011. Retrieved 28 August 2011.

- ^ a b "Bibliografia della Libia"; Bertarelli (1929), p. 177.

- ^ Ben Cahoon. "Libya". Worldstatesmen.org. Retrieved 2011-02-28.

- ^ Federal Research Division of the Library of Congress, (1987), "Climate & Hydrology of Libya", U.S. Library of Congress. Retrieved July 15, 2006.

- ^ (2005), "Demographics of Libya", Education Libya. Retrieved June 29, 2006.

- ^ (July 20, 2006), "Field Listings - Coastlines", CIA World Factbook. Retrieved July 23, 2006.

- ^ a b c Zboray, András, "Flora and Fauna of the Libyan Desert", Fliegel Jezerniczky Expeditions. Retrieved July 14, 2006.

- ^ Hottest Place, "El Azizia Libya, 'How Hot is Hot?'", Extreme Science. Retrieved 02 March 2011.

- ^ ""Fossil Water" in Libya", NASA. Retrieved March 24, 2007.

- ^ France Becomes First Country to Recognize Libyan Rebels, New York Times, March 11, 2011

- ^ Kim Ghattas (2011-07-15). "US recognises Libyan rebel TNC as legitimate authority". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2011-08-20.

- ^ France appoints envoy to rebel Libyan city, Sydney Morning Herald

- ^ "Qatar recognises Libyan rebels after oil deal". Al Jazeera English. 28 March 2011. Retrieved 25 April 2011.

- ^ "Libya: Frattini, the NTC is Italy's only interlocutor". Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 4 April 2011. Retrieved 2011-04-04.

- ^ "Germany recognises Libya rebel council -rebel says". Reuters. 13 June 2011. Retrieved 13 June 2011.

- ^ Clark, Campbell (14 June 2011). "Canada recognizes anti-gadhafi rebels as libyas new government". Toronto: Theglobeandmail. Retrieved 14 June 2011.

- ^ "Libya: Turkey recognises Transitional National Council". BBC News. 3 July 2011.

- ^ Talbi, Karim (13 March 2011). "Libyan rebels get Arab League boost". The Sydney Morning Herald.

- ^ "Libya: US and EU say Muammar Gaddafi must go". BBC News. 11 March 2011.

- ^ "Libyan rebels form 'interim government' - Africa". Al Jazeera English. 2011-03-22. Retrieved 2011-08-20.

- ^ "Libyan Charge d'Affaires to be expelled from UK". 2011-07-27. Retrieved 2011-08-18.

- ^ Kirkpatrick, David D.; Chivers, C. J. (13 August 2011). "Tribal Rifts Threaten to Undermine Libya Uprising". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ "Libyan rebels move base to Tripoli". Global Post. 25 August 2011. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ Crilly, Rob (1 September 2011). "Libya: Loyalist troops in Sirte given another week to surrender". London. The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ "Libyan Health Minister on Cairo Visit Seeking Medical Supplies". The Tripoli Post. 30 June 2011. Retrieved 6 July 2011.

- ^ Kelemen, Michele (13 May 2011). "Rebel Leader Asks U.S. For Frozen Libya Funds". National Public Radio. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- ^ "Italy says Libyan rebels ask for weapons". RIA Novosti. 13 April 2011. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- ^ "Libya 'will direct oil to friends'". Times of Malta. 19 March 2011. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- ^ "Cash-strapped Libya rebels call for loans". News24. 30 June 2011. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- ^ Corfield, Gareth (24 June 2011). "Norwegian Libyan contribution may yield oil contracts". The Foreigner. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- ^ Federal Research Division of the Library of Congress, (1987), "Independent Libya", U.S. Library of Congress. Retrieved July 14, 2006.

- ^ Abadi, Jacob (2000), "Pragmatism and Rhetoric in Libya's Policy Toward Israel", The Journal of Conflict Studies: Volume XX Number 1 Fall 2000, University of New Brunswick. Retrieved July 19, 2006.

- ^ Idi Amin, Benoni Turyahikayo-Rugyema (1998). Idi Amin speaks: an annotated selection of his speeches. ISBN 0942615387.

- ^ Joseph T. Stanik (2003). El Dorado Canyon: Reagan's undeclared war with Qaddafi. ISBN 1557509832.

- ^ a b Brian Lee Davis (1990). Qaddafi, terrorism, and the origins of the U.S. attack on Libya. p. 16.

- ^ "How the mighty are falling". The Economist. 5 July 2007. Retrieved 17 July 2007.

- ^ "Gaddafi Given Yugoslavia's Top Medal By Milosevic". Reuters. 26 October 1999.

- ^ Rayner, Gordon (28 August 2010). "Yvonne Fletcher killer may be brought to justice". The Daily Telegraph. London.

- ^ Brian Lee Davis. Qaddafi, terrorism, and the origins of the U.S. attack on Libya. p. 183.

- ^ President Ronald Reagan (1982-03-10). "Proclamation 4907 – Imports of Petroleum". US Office of the Federal Register.

- ^ U.K. Politics, (March 25, 2004), "Blair hails new Libyan relations", BBC news. Retrieved July 15, 2006.

- ^ Marcus, Jonathan, (May 15, 2006), "Washington's Libyan fairy tale", BBC News. Retrieved July 15, 2006.

- ^ Leverett, Flynt (2004-01-23). "Why Libya Gave Up on the Bomb". New York Times. Retrieved 2011-02-24.

- ^ "United States, Congress US Department Of State, Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor. 2007 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices. November 23, 2008". State.gov. 2008-03-11. Retrieved 2010-05-02.