Antihypertensive drug

The antihypertensives are a class of drugs that are used to treat hypertension (high blood pressure).[1] Evidence suggests that reduction of the blood pressure by 5 mmHg can decrease the risk of stroke by 34%, of ischaemic heart disease by 21%, and reduce the likelihood of dementia, heart failure, and mortality from cardiovascular disease.[2] There are many classes of antihypertensives, which lower blood pressure by different means; among the most important and most widely used are the thiazide diuretics, the ACE inhibitors, the calcium channel blockers, the beta blockers, and the angiotensin II receptor antagonists or ARBs.

Which type of medication to use initially for hypertension has been the subject of several large studies and resulting national guidelines. The fundamental goal of treatment should be the prevention of the important endpoints of hypertension, such as heart attack, stroke and heart failure. Patient age, associated clinical conditions and end-organ damage also play a part in determining dosage and type of medication administered.[3] The several classes of antihypertensives differ in side effect profiles, ability to prevent endpoints, and cost. The choice of more expensive agents, where cheaper ones would be equally effective, may have negative impacts on national healthcare budgets.[4] As of 2009, the best available evidence favors the thiazide diuretics as the first-line treatment of choice for high blood pressure when drugs are necessary.[5] Although clinical evidence shows calcium channel blockers and thiazide-type diuretics are preferred first-line treatments for most people (from both efficacy and cost points of view), an ACE inhibitor is recommended by NICE in the UK for those under 55 years old.[6]

Diuretics

Diuretics help the kidneys eliminate excess salt and water from the body's tissues and blood.

- Loop diuretics:

- Thiazide diuretics:

- Thiazide-like diuretics:

- Potassium-sparing diuretics:

Only the thiazide and thiazide-like diuretics have good evidence of beneficial effects on important endpoints of hypertension, and hence, should usually be the first choice when selecting a diuretic to treat hypertension. The reason why thiazide-type diuretics are better than the others is (at least in part) thought to be because of their vasodilating properties.[citation needed] Although the diuretic effect of thiazides may be apparent shortly after administration, it takes longer (weeks of treatment) for the full anti-hypertensive effect to develop. In the United States, the JNC7 (The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention of Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Pressure) recommends starting with a thiazide diuretic if single therapy is being initiated and another medication is not indicated.[7] This is based on a slightly better outcome for chlortalidone in the ALLHAT study versus other anti-hypertensives and because thiazide diuretics are relatively cheap.[8] A subsequent smaller study (ANBP2) published after the JNC7 did not show this small difference in outcome and actually showed a slightly better outcome for ACE-inhibitors in older male patients.[9]

Despite thiazides being cheap, effective, and recommended as the best first-line drug for hypertension by many experts, they are not prescribed as often as some newer drugs. This is because they have been associated with increased risk of new-onset diabetes and as such are recommended for use in patients over 65 where the risk of new-onset diabetes is outweighed by the benefits of controlling systolic blood pressure.[10] Another theory is that they are off-patent and thus rarely promoted by the drug industry.[11]

Adrenergic receptor antagonists

- Beta blockers

- Alpha blockers:

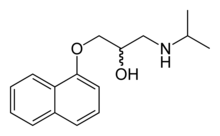

- Mixed Alpha + Beta blockers:

Although beta blockers lower blood pressure, they do not have a positive benefit on endpoints as some other antihypertensives.[12] In particular, beta-blockers are no longer recommended as first-line treatment due to relative adverse risk of stroke and new-onset diabetes when compared to other medications,[3] while certain specific beta-blockers such as atenolol appear to be less useful in overall treatment of hypertension than several other agents.[13] They do, however, have an important role in the prevention of heart attacks in people who have already had a heart attack.[14] In the United Kingdom, the June 2006 "Hypertension: Management of Hypertension in Adults in Primary Care"[15] guideline of the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, downgraded the role of beta-blockers due to their risk of provoking type 2 diabetes.[16]

Despite lowering blood pressure, alpha blockers have significantly poorer endpoint outcomes than other antihypertensives, and are no longer recommended as a first-line choice in the treatment of hypertension.[17] However, they may be useful for some men with symptoms of prostate disease.

Calcium channel blockers

Calcium channel blockers block the entry of calcium into muscle cells in artery walls.

- dihydropyridines:

- non-dihydropyridines:

Renin Inhibitors

Renin comes one level higher than Angiotensin Converting Enzyme (ACE) in the Renin-Angiotensin System. Inhibitors of renin can therefore effectively reduce hyptertension. Aliskiren (developed by Novartis) is a renin inhibitor which has been approved by the US-FDA for treatment of hypertension.[18]

ACE inhibitors

ACE inhibitors inhibit the activity of Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE), an enzyme responsible for the conversion of angiotensin I into angiotensin II, a potent vasoconstrictor.

Angiotensin II receptor antagonists

Angiotensin II receptor antagonists work by antagonizing the activation of angiotensin receptors.

Aldosterone antagonists

Aldosterone receptor antagonists:

Aldosterone antagonists are not recommended as first-line agents for blood pressure,[7] but spironolactone and eplerenone are both used in the treatment of heart failure.

Vasodilators

Vasodilators act directly on the smooth muscle of arteries to relax their walls so blood can move more easily through them; they are only used in hypertensive emergencies or when other drugs have failed, and even so are rarely given alone.

Sodium nitroprusside, a very potent, short-acting vasodilator, is most commonly used for the quick, temporary reduction of blood pressure in emergencies (such as malignant hypertension or aortic dissection).[19][20] Hydralazine and its derivatives are also used in the treatment of severe hypertension, although they should be avoided in emergencies.[20] They are no longer indicated as first-line therapy for high blood pressure due to side effects and safety concerns, but hydralazine remains a drug of choice in gestational hypertension.[19]

Alpha-2 agonists

Central alpha agonists lower blood pressure by stimulating alpha-receptors in the brain which open peripheral arteries easing blood flow. Central alpha agonists, such as clonidine, are usually prescribed when all other anti-hypertensive medications have failed. For treating hypertension, these drugs are usually administered in combination with a diuretic.

Adverse effects of this class of drugs include sedation, drying of the nasal mucosa and rebound hypertension.

Some adrenergic neuron blockers are used for the most resistant forms of hypertension:

Future treatment options

Blood pressure vaccines

Blood pressure vaccinations are being trialed and may become a treatment option for high blood pressure in the future. CYT006-AngQb was only moderately successful in studies, but similar vaccines are being investigated.[21]

Choice of initial medication

For mild blood pressure elevation, consensus guidelines call for medically supervised lifestyle changes and observation before recommending initiation of drug therapy. However, according to the American Hypertension Association, evidence of sustained damage to the body may be present even prior to observed elevation of blood pressure. Therefore the use of hypertensive medications may be started in individuals with apparent normal blood pressures but who show evidence of hypertension related nephropathy, proteinuria, atherosclerotic vascular disease, as well as other evidence of hypertension related organ damage.

If lifestyle changes are ineffective, then drug therapy is initiated, often requiring more than one agent to effectively lower hypertension. Which type of many medications should be used initially for hypertension has been the subject of several large studies and various national guidelines. Considerations include factors such as age, race, and other medical conditions.[7]

The largest study, Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT), concluded that thiazide-type diuretics are better and cheaper than other major classes of drugs at preventing cardiovascular disease, and should be preferred as the starting drug. ALLHAT used the thiazide diuretic chlorthalidone.[8] (ALLHAT showed that doxazosin, an alpha-adrenergic receptor blocker, had a higher incidence of heart failure events, and the doxazosin arm of the study was stopped.)

A subsequent smaller study (ANBP2) did not show the slight advantages in thiazide diuretic outcomes observed in the ALLHAT study, and actually showed slightly better outcomes for ACE-inhibitors in older white male patients.[9]

Thiazide diuretics are effective, recommended as the best first-line drug for hypertension by many experts, and are much more affordable than other therapies, yet they are not prescribed as often as some newer drugs. Hydrochlorothiazide is perhaps the safest and most inexpensive agent commonly used in this class and is very frequently combined with other agents in a single pill. Doses in excess of 25 milligrams per day of this agent incur an unacceptable risk of low potassium or Hypokalemia. Patients with an exaggerated hypokalemic response to a low dose of a thiazide diuretic should be suspected to have Hyperaldosteronism, a common cause of secondary hypertension.

Other drugs have a role in treating hypertension. Adverse effects of thiazide diuretics include hypercholesterolemia, and impaired glucose tolerance with increased risk of developing Diabetes mellitus type 2. The thiazide diuretics also deplete circulating potassium unless combined with a potassium-sparing diuretic or supplemental potassium. Some authors have challenged thiazides as first line treatment.[22][23][24] However as the Merck Manual of Geriatrics notes, "thiazide-type diuretics are especially safe and effective in the elderly."[25]

Current UK guidelines suggest starting patients over the age of 55 years and all those of African/Afrocaribbean ethnicity firstly on calcium channel blockers or thiazide diuretics, whilst younger patients of other ethnic groups should be started on ACE-inhibitors. Subsequently if dual therapy is required to use ACE-inhibitor in combination with either a calcium channel blocker or a (thiazide) diuretic. Triple therapy is then of all three groups and should the need arise then to add in a fourth agent, to consider either a further diuretic (e.g. spironolactone or furosemide), an alpha-blocker or a beta-blocker.[26] Prior to the demotion of beta-blockers as first line agents, the UK sequence of combination therapy used the first letter of the drug classes and was known as the "ABCD rule".[26][27]

Patient Factors Affecting Antihypertensive Drug Choice

The choice between the drugs is to a large degree determined by the characteristics of the patient being prescribed for, the drugs' side-effects, and cost. Most drugs have other uses; sometimes the presence of other symptoms can warrant the use of one particular antihypertensive. Examples include:

- Age can affect choice of medications. Current UK guidelines suggest starting patients over the age of 55 years first on calcium channel blockers or thiazide diuretics.

- Anxiety may be improved with the use of beta blockers.

- Asthmatics have been reported to have worsening symptoms when using beta blockers.

- Benign prostatic hyperplasia may be improved with the use of an alpha blocker.

- Diabetes. The ace inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers have been shown to prevent the renal and retinal complications of diabetes mellitus.

- Gout may be worsened by diuretics, while losartan reduces serum urate. [28]

- Kidney stones may be improved with the use of thiazide-type diuretics [29]

- Heart block β-blockers and nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers should not be used in patients with heart block greater than first degree. [30]

- Heart failure may be worsened with nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, the alpha blocker doxazosin, and the alpha-2 agonists moxonidine and clonidine. Whereas β-blockers, diuretics, ACE inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, and aldosterone receptor antagonists have been shown to improve outcome. [31]

- Pregnancy. Although α-methyldopa is generally regarded as a first-line agent, labetalol and metoprolol are also acceptable. Atenolol has been associated with intrauterine growth retardation, as well as decreased placental growth and weight when prescribed during pregnancy. Ace inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs)are contraindicated in women who are or who intend to become pregnant.[7]

- Race. The JNC 7 particularly points out that when used as monotherapy, thiazide diuretics and calcium channel blockers have been found to be more effective for reducing blood pressure in African-American patients than β-blockers, ACE inhibitors, or ARBs.

- Tremor may warrant the use of beta blockers.

The JNC 7 report outlines compelling reasons to choose one drug over the others for certain individual patients.[7]

Non-drug treatment options

Several studies have found that hibiscus tea has a substantial antihypertensive effect attributable to the flower's ACE-inhibiting anthocyanin content, and possibly to a diuretic effect. One study found that hibiscus conferred an antihypertensive effect comparable to 50 mg./day of the drug captopril.[32][33][34][35][36]

Another potential treatment is Coenzyme Q10,[37] which a meta analysis of 12 studies found reductions in systolic pressure of 10–17 points and a reduction in diastolic pressure of 8–10 points[38] with doses of roughly 200 mg/day.

See also

References

- ^ Antihypertensive+Agents at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- ^ Law M, Wald N, Morris J (2003). "Lowering blood pressure to prevent myocardial infarction and stroke: a new preventive strategy" (PDF). Health Technol Assess. 7 (31): 1–94. PMID 14604498.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Nelson, Mark. "Drug treatment of elevated blood pressure". Australian Prescriber (33): 108–112. Retrieved August 11, 2010.

- ^ Nelson MR; McNeil JJ; Peeters A; et al. (2001). "PBS/RPBS cost implications of trends and guideline recommendations in the pharmacological management of hypertension in Australia, 1994–1998". Med J Aust. 174 (11): 565–8. PMID 11453328.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Wright JM, Musini VM (2009). Wright, James M (ed.). "First-line drugs for hypertension". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 8 (3): CD001841. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001841.pub2. PMID 19588327.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/CG034NICEguideline.pdf, p19

- ^ a b c d e Chobanian AV; et al. (2003). "The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report". JAMA. 289 (19): 2560–72. doi:10.1001/jama.289.19.2560. PMID 12748199.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help) - ^ a b ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group (2002). "Major outcomes in high-risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diuretic: The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT)". JAMA. 288 (23): 2981–97. doi:10.1001/jama.288.23.2981. PMID 12479763.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) Cite error: The named reference "allhat" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ a b Wing LM; Reid CM; Ryan P; et al. (2003). "A comparison of outcomes with angiotensin-converting—enzyme inhibitors and diuretics for hypertension in the elderly". NEJM. 348 (7): 583–92. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa021716. PMID 12584366.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) Cite error: The named reference "anbp2" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Zillich AJ; Garg J; Basu S; et al. (August 2006). "Thiazide diretics, potassium and the development of diabetes: a quantitative review". Hypertension. 48 (2): 219–224. doi:10.1161/01.HYP.0000231552.10054.aa. PMID 16801488.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|unused_data=ignored (help) - ^ Wang TJ, Ausiello JC, Stafford RS (20 April 1999). "Trends in Antihypertensive Drug Advertising, 1985–1996". Circulation. 99 (15): 2055–2057. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.99.15.2055. PMID 10209012.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lindholm LH, Carlberg B, Samuelsson O (2005). "Should beta blockers remain first choice in the treatment of primary hypertension? A meta-analysis". Lancet. 366 (9496): 1545–53. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67573-3. PMID 16257341.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Carlberg B, Samuelsson O, Lindholm LH (2004). "Atenolol in hypertension: is it a wise choice?". Lancet. 364 (9446): 1684–9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17355-8. PMID 15530629.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Freemantle N; Cleland J; Young P; et al. (1999). "β Blockade after myocardial infarction: systematic review and meta regression analysis". BMJ. 318 (7200): 1730–7. PMC 31101. PMID 10381708.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Hypertension: management of hypertension in adults in primary care" (PDF). National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Retrieved 2006-09-30.

- ^ Sheetal Ladva (2006-06-28). "NICE and BHS launch updated hypertension guideline". National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Archived from the original on 2007-09-29. Retrieved 2006-09-30.

- ^ ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group (2003). "Diuretic Versus alpha-Blocker as First-Step Antihypertensive Therapy". Hypertension. 42 (3): 239–46. doi:10.1161/01.HYP.0000086521.95630.5A. PMID 12925554.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Direct Renin Inhibitors as Antihypertensive Drugs

- ^ a b Brunton L, Parker K, Blumenthal D, Buxton I (2007). "Therapy of hypertension". Goodman & Gilman's Manual of Pharmacology and Therapeutics. New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 544–60. ISBN 978-0071443432.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 10893382, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=10893382instead. - ^ Brown, MJ (2009). "Success and failure of vaccines against renin-angiotensin system components". Nature reviews. Cardiology. 6 (10): 639–47. doi:10.1038/nrcardio.2009.156. PMID 19707182.

- ^ Lewis PJ, Kohner EM, Petrie A, Dollery CT (1976). "Deterioration of glucose tolerance in hypertensive patients on prolonged diuretic treatment". Lancet. 307 (7959): 564–566. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(76)90359-7. PMID 55840.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Murphy MB, Lewis PJ, Kohner E, Schumer B, Dollery CT (1982). "Glucose intolerance in hypertensive patients treated with diuretics; a fourteen-year follow-up". Lancet. 320 (8311): 1293–1295. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(82)91506-9. PMID 6128594.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Messerli FH, Williams B, Ritz E (2007). "Essential hypertension". Lancet. 370 (9587): 591–603. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61299-9. PMID 17707755.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Section 11. Cardiovascular Disorders – Chapter 85. Hypertension". Merck Manual of Geriatrics. July 2005.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "CG34 Hypertension – quick reference guide" (PDF). National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. 28 June 2006. Retrieved 2009-03-04.

- ^ Williams B (2003). "Treatment of hypertension in the UK: simple as ABCD?". J R Soc Med. 96 (11): 521–2. doi:10.1258/jrsm.96.11.521. PMC 539621. PMID 14594956.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Würzner G,"Comparative effects of losartan and irbesartan on serum uric acid in hypertensive patients with hyperuricaemia and gout." J Hypertens. 2001;19(10):1855.

- ^ Worcester EM, Coe FL: Clinical practice. Calcium kidney stones. N Engl J Med 2010;363(10):954-963. http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMcp1001011

- ^ 1.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al: The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure-The JNC 7 Report. National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI), 2003. http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/hypertension/jnc7full.pdf

- ^ Rosendorff C, Black HR, Cannon CP, et al: Treatment of hypertension in the prevention and management of ischemic heart disease: A scientific statement From the American Heart Association Council for High Blood Pressure Research and the Councils on Clinical Cardiology and Epidemiology and Prevention. Circulation 2007;115(21):2761-2788. http://circ.ahajournals.org/cgi/content/full/115/21/2761

- ^ Mozaffari-Khosravi H, Jalali-Khanabadi BA, Afkhami-Ardekani M, Fatehi F, Noori-Shadkam M (2009). "The effects of sour tea (Hibiscus sabdariffa) on hypertension in patients with type II diabetes". J Hum Hypertens. 23 (1): 48–54. doi:10.1038/jhh.2008.100. PMID 18685605.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ McKay DL, Chen CY, Saltzman E, Blumberg JB (2010). "Hibiscus sabdariffa L. tea (tisane) lowers blood pressure in prehypertensive and mildly hypertensive adults". J. Nutr. 140 (2): 298–303. doi:10.3945/jn.109.115097. PMID 20018807.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "AHA 2008: Hibiscus Tea Reduces Blood Pressure". 11 November 2008.

- ^ Herrera-Arellano A; Miranda-Sánchez J; Avila-Castro P; et al. (2007). "Clinical effects produced by a standardized herbal medicinal product of Hibiscus sabdariffa on patients with hypertension. A randomized, double-blind, lisinopril-controlled clinical trial". Planta Med. 73 (1): 6–12. doi:10.1055/s-2006-957065. PMID 17315307.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Herrera-Arellano A, Flores-Romero S, Chávez-Soto MA, Tortoriello J (2004). "Effectiveness and tolerability of a standardized extract from Hibiscus sabdariffa in patients with mild to moderate hypertension: a controlled and randomized clinical trial". Phytomedicine. 11 (5): 375–82. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2004.04.001. PMID 15330492.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Langsjoen, P; Langsjoen, P; Willis, R; Folkers, K (1994). "Treatment of essential hypertension with coenzyme Q10". Molecular aspects of medicine. 15 Suppl: S265–72. PMID 7752851.

- ^ Rosenfeldt, FL; Haas, SJ; Krum, H; Hadj, A; Ng, K; Leong, JY; Watts, GF (2007). "Coenzyme Q10 in the treatment of hypertension: A meta-analysis of the clinical trials". Journal of human hypertension. 21 (4): 297–306. doi:10.1038/sj.jhh.1002138. PMID 17287847.