Jayne Mansfield

Jayne Mansfield | |

|---|---|

| File:Rockhunter.jpg Mansfield in Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? (1957) | |

| Born | Vera Jayne Palmer April 19, 1933 |

| Died | June 29, 1967 (aged 34) |

| Cause of death | Traffic accident |

| Resting place | Fairview Cemetery, Pen Argyl, Pennsylvania 40°52.08′N 75°15.20′W / 40.86800°N 75.25333°W |

| Other names | Vera Jayne Peers, Vera Palmer |

| Occupation(s) | Actress, singer, Playboy playmate, nightclub entertainer, model |

| Years active | 1954–1967 |

| Notable work | The Girl Can't Help It, Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter?, Too Hot to Handle, The Wayward Bus, Promises! Promises! |

| Television | The Red Skelton Show, Alfred Hitchcock Presents, The Ed Sullivan Show |

| Spouse(s) |

Paul Mansfield (m. 1950–1958) |

| Children | Jayne Marie Mansfield (b. 1950) Miklós "Mickey" Hargitay, Jr. (b. 1958) Zoltán Hargitay (b. 1960) Mariska Hargitay (b. 1964) Antonio "Tony" Cimber (b. 1965) |

| Parent(s) | Herbert William Palmer (1904–1936) Vera Jeffrey Palmer Peers (1903–2000) |

| Awards | Theatre World Award (1956); Golden Globe for New Star Of The Year – Actress (1957); Golden Laurel for Top Female Musical Performance (1959) |

| Website | http://www.jaynemansfield.com/ |

| Signature | |

| |

Jayne Mansfield (born Vera Jayne Palmer; April 19, 1933 – June 29, 1967) was an American film, theatre, and television actress, and major Hollywood sex symbol during the late 1950s and early 1960s. Mansfield was 20th Century Fox's alternative Marilyn Monroe, who came to be known as the "Working Man's Monroe" or the "Poor Man's Monroe" during her career. She was also famous for her promotional drive and publicity stunts.

Mansfield made her Broadway debut in 1955, but her film career began in 1956.[1] She was one of Hollywood's original blonde bombshells,[2] and although many people have never seen her movies, Mansfield remains one of the most recognizable icons of 1950s celebrity culture.[3] With the decrease of the demand for big-breasted blonde bombshells and the increase in the negative backlash against her over-publicity, she became a box-office has-been by the end of 1960s. Her career declined first to low-budget foreign movies and major Las Vegas nightclub dates; then to television guest appearances; next to touring plays and minor Las Vegas nightclub dates; and finally ended in small nightclub dates.[1]

While Mansfield's film career was short-lived, she had several box office successes and won a Theatre World Award, a Golden Globe and a Golden Laurel. She enjoyed success in the role of fictional actress Rita Marlowe in both the 1955–1956 Broadway version, and, in the 1957 Hollywood film version of Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter?. She showcased her comedic skills in The Girl Can't Help It (1956), her dramatic assets in The Wayward Bus (1957), and her sizzling presence in Too Hot to Handle (1960). She also sang for studio recordings, including the album Shakespeare, Tchaikovsky & Me and the singles Suey and As the Clouds Drift by (with Jimi Hendrix). Mansfield's notable television work included The Red Skelton Show (1959–1963) and The Ed Sullivan Show (1957).

By the early 1960s, Mansfield's box office popularity had declined and Hollywood studios lost interest in her. Some of the last attempts that Hollywood took to publicize her were in The George Raft Story (1961) and It Happened in Athens (1962).[1] Towards the end of her career, Mansfield remained a popular celebrity, continuing to attract large crowds outside the United States and in lucrative and successful nightclub acts (including The Tropicana Holiday and The House of Love in Las Vegas), and summer-theater work. Her film career continued with cheap independent films and European melodramas and comedies, with some of her later films being filmed in United Kingdom, Italy, Germany, and Greece.[4] In the sexploitation film Promises! Promises! (1963), she became the first major American actress to have a nude starring role in a Hollywood motion picture. In February 1955, she became one of the early Playmates.

Divorced from "high-school" sweetheart Paul Mansfield (1950–1958) and actor–bodybuilder Mickey Hargitay (1958–1963), she finally married to film director Matt Cimber (1964–1966). She had five children: Jayne Marie Mansfield (born 1950), Miklós Jeffrey Palmer Hargitay (born 1958), Zoltán Anthony Hargitay (born 1960), actress Mariska Magdolna Hargitay (born 1964) and Antonio "Tony" Cimber (born 1965). Mansfield died in an automobile accident at age 34.

Early life and education

Jayne Mansfield was born Vera Jayne Palmer on April 19, 1933 in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania. She was the only child of Herbert William (1904–1936), of German ancestry, and Vera Jeffrey Palmer (1903–2000), of English descent.[5] Vera Jayne's father, Elmer E Palmer, was from the largely Cornish area of Pen Argyl, Pennsylvania,[6] where he was involved with the slate industry.[7] She inherited more than $90,000.00 from her maternal grandfather Elmer ($950,450 in 2024 dollars[8]) and more than $36,000.00 from her maternal grandmother Alice Jane Palmer in 1958 ($380,180 in 2024 dollars[8]).[7][9] Jayne spent her early childhood in Phillipsburg, New Jersey,[10] where her father was an attorney who practiced with future New Jersey governor Robert B. Meyner. In 1936, when Jayne was three years old, Herbert William died of a heart attack while driving a car with his wife and daughter. Following his death, Jayne's mother worked as a teacher. In 1939 Vera Palmer married sales engineer Harry Lawrence Peers and the family moved to Dallas, Texas,[11] where Jayne was known as Vera Jayne Peers.[12][13]

Jayne graduated from Highland Park High School in 1950.[14][15][16][17] While in high school, Jayne took lessons in violin, piano and viola. She also studied Spanish and German.[18][19] She consistently received high Bs in school (including in mathematics).[20] At the age of 12, she also took lessons in ballroom dance.[21] She married Paul James Mansfield on May 10, 1950. Their daughter, Jayne Marie Mansfield, was born on November 8, 1950. After marriage, Jayne and Paul enrolled into Southern Methodist University to study acting, where lacking finances to afford day care, carried around her daughter Jayne Marie.[22][4][23] In 1951, she moved to Austin, Texas, with Paul, and studied dramatics at the University of Texas at Austin, until her junior year.[15][16][17][22] While attending the University of Texas, she worked as a nude model for art classes, sold books door-to-door, and worked in the evenings as receptionist of a dance studio.[24][25][26] While studying and trying to earn a living, she joined the Curtain Club (a campus theatrical society, at that time also had Tom Jones, Harvey Schmidt, Rip Torn, and Pat Hingle among its members)[25][27][28] and was active at the Austin Civic Theater.[25]

In 1952, she moved back to Dallas and for several months, became a student of actor Baruch Lumet, who was father of director Sidney Lumet and founder of the newly founded and now defunct Dallas Institute of Performing Arts.[29][30][31] Lumet called Jayne and Rip Torn his "kids", and seeing her potential, provided her private lessons.[15][32] Paul was then called to the United States Army Reserve for the Korean War.[26] Her life became easier with Paul's army allotment.[33] After spending a year at Camp Gordon, Georgia (a US Army training facility) they moved to Los Angeles in 1954, where Jayne studied Theater Arts at UCLA during the summer,[16][15] and returned to Texas to spend the fall quarter at Southern Methodist University.[1] While in California, she left Jayne Marie with her maternal grandparents (Jayne's parents).[26] She managed to maintain a B grade average, between a variety of odd jobs, including: a stint as a candy vendor at a movie theater (where caught the eye of a TV producer),[4] a part-time model at the Blue Book Model Agency (where Marilyn Monroe was first noticed),[34] and working as a photographer at Esther Williams' nightclub, the Trail.[29][1][22] At The Trails she earned $6 plus 10% of her sales ($68 in 2024 dollars[8]) each evening taking pictures of patrons.[29] Frequent references have been made to Mansfield's very high IQ, which she claimed was 163.[35] She spoke five languages, including English, fluent French and Spanish, German learned in high school, and studied Italian in 1963.[36] Reputed to be Hollywood's "smartest dumb blonde", she would later complain that the public did not care about her brains. "They're more interested in 40–21–35", she said.[37][23]

Early career

| Jayne Mansfield | |

|---|---|

| Playboy centerfold appearance | |

| February, 1955 | |

| Preceded by | Bettie Page |

| Succeeded by | Marilyn Waltz |

| Personal details | |

| Height | 5 ft 6 in (1.68 m) (5 ft 8 in according to her autopsy) |

During her tenure at the University of Texas at Austin, Mansfield won several beauty contests, including: Miss Photoflash, Miss Magnesium Lamp, and Miss Fire Prevention Week. The only title she refused was Miss Roquefort Cheese, because she believed it "just didn't sound right".[39] Mansfield accepted a bit part in a B-grade film titled Prehistoric Women (produced by Alliance Productions, alternatively titled The Virgin Goddess) in 1950.[26] In 1952, while at Dallas, she and Paul participated in small local-theater productions of The Slaves of Demon Rum and Ten Nights in a Barroom, and Anything Goes in Camp Gordon, Georgia. After Paul left for military service, Mansfield first appeared on stage in a production of Arthur Miller's Death of a Salesman on October 22, 1953, with the players of the Knox Street Theater, headed by Lumet.[1]

While at UCLA she entered the Miss California contest (hiding her marital status), and won the local round before withdrawing.[26] Early in her career the prominence of her breasts was considered problematic and led her to be cut from her first professional assignment, an advertising campaign for General Electric, which depicted several young women in bathing suits relaxing around a pool.[40] Head of head Blue Book Model Agency Emmeline Snively had sent her onto photographer Gene Lester, which led to her short-lived assignment in the commercial for General Electric.[29] In 1954, she auditioned at both Paramount Pictures and Warner Bros. for a part in The Seven Year Itch but failed to impress.[1] That year, she landed her first acting assignment in Lux Video Theatre, a series on CBS ("An Angel Went AWOL", October 21, 1954).[1] In the show she sat at the piano and delivered a few lines of dialogue for $300.00 ($3,404 in 2024 dollars[8]).[41]

She posed nude for the February 1955 issue of Playboy, an event that helped launch Mansfield's career[42] and increased the magazine's circulation;[43] Playboy had begun publishing from publisher–editor Hugh Hefner's kitchen the year before.[44] In 1964, the magazine repeated the pictorial.[45] Photos from that pictorial was reprinted in a number of Playboy issues, including: December 1965 ("The Playboy Portfolio of Sex Stars"), January 1979 ("25 Beautiful Years"), January 1984 ("30 Memorable Years"), January 1989 ("Women Of The Fifties"), January 1994 ("Remember Jayne"), November 1996 ("Playboy Gallery"), August 1999 ("Playboy's Sex Stars of the Century"; Special edition), and January 2000 ("Centerfolds Of The Century").

Film career

Career beginnings (mid-1950s)

Mansfield's first film part was the supporting role of Candy Price in Female Jungle (1955), a low-budget drama which was completed in 10 days. Her part was filmed in only a few days, and she received $150 for her performance ($1,706 in 2024 dollars[8]). Female Jungle was released in January 1955 by producer Burt Kaiser. That year Paul Wendkos offered Mansfield the dramatic role of Gladden in The Burglar (1957), his film adaptation of David Goodis' novel. The film was done in film noir style, and Mansfield appeared alongside Dan Duryea and Martha Vickers. The Burglar was released two years later, when Mansfield's fame was at its peak. She was successful in this straight dramatic role, although most of her subsequent film appearances would be either comedic or capitalize on her sex appeal.

On February 8, 1955, Mansfield was signed by Warner Bros. to a six-month contract after one of its talent scouts discovered her in a production at the Pasadena Playhouse. She filed for divorce from Paul the same day.[46] Warner wanted Mansfield as its version of the popular (and lucrative) Marilyn Monroe of 20th Century Fox. Mansfield was given a bit part in Pete Kelly's Blues (1955), starring and directed by Jack Webb. She made one more movie with Warner Bros., which gave her another small (but significant) role as Angela O'Hara opposite Edward G. Robinson in Illegal (1955). The film offered another rare serious performance by Mansfield. After leaving Warner Bros. she made an uncredited cameo appearance in Hell on Frisco Bay (1955), starring Alan Ladd.

Film stardom (late 1950s)

In 1955, Mansfield enjoyed a successful Broadway run in the musical Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter?. Though at the beginning reviews were harsh, the play soon became a runaway hit with audiences. On May 3, 1956, Mansfield was noticed by 20th Century Fox, who was having troubles with its leading star, Marilyn Monroe. The studio wanted to sign Mansfield to a contract and did. However, she was still under contract to Broadway and contiuned playing Rock Hunter on the stage. Soon afterwards, Fox promoted Mansfield as "Marilyn Monroe king-sized".

Mansfield received her first starring film role as Jerri Jordan in the Frank Tashlin's The Girl Can't Help It (1956).[47] The film, originally titled Do-Re-Mi, featured a high-profile cast of contemporary rock and roll and R&B artists including Gene Vincent, Eddie Cochran, Fats Domino, The Platters and Little Richard.[48] During the filming of the feature, Mansfield still worked on Broadway with Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter?. After The Girl Can't Help It was released, Fox bought Mansfield out of her Broadway contract for $100,000 and shut the production of Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? down after 444 performances.[citation needed]

Mansfield then played a dramatic role in The Wayward Bus (1957) adapted from John Steinbeck's novel. In this film, she attempted to move away from her "blonde bombshell" image and establish herself as a serious actress. It enjoyed reasonable success at the box office, and Mansfield won a Golden Globe in 1957 for New Star of the Year – Actress (beating Carroll Baker and Natalie Wood) for her performance as a "wistful derelict". It was "generally conceded to have been her best acting", according to The New York Times, in a fitful career hampered by her flamboyant image, distinctive voice ("a soft-voiced coo punctuated with squeals"), voluptuous figure and limited acting range.[49]

She reprised her role of Rita Marlowe in the 1957 film version of Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter?, co-starring Tony Randall and Joan Blondell. 20th Century Fox launched their new blonde bombshell with a 40-day 16-country tour of Europe for the studio in 1957. She attended the premier of Rock Hunter (release as Oh! For a man in UK) in London, and met the Queen of England as part of the tour.[50][51][52]

Mansfield's fourth starring role in a Hollywood film was in Kiss Them for Me (1957), in which she received prominent billing alongside Cary Grant. However, in the film itself she is little more than comic relief; Grant's character prefers a sleek, demure redhead played by fashion model Suzy Parker. Kiss Them for Me was described as "vapid" and "ill-advised", and was a box-office disappointment. The film was Mansfield's final starring role in a mainstream Hollywood studio film.[53] It also marked one of the last attempts by 20th Century Fox to publicize her.[54]

The continuing publicity surrounding Mansfield's physical appearance failed to sustain her career.[55] She was offered a part opposite James Stewart and Jack Lemmon in the romantic comedy Bell, Book and Candle (1958), but had to turn it down because of her pregnancy. Mansfield's rival, Kim Novak, would replace her in the film. In 1958, Fox gave Mansfield the lead role as Kate opposite Kenneth More in the western spoof The Sheriff of Fractured Jaw. Although it was filmed in 1958, it was not released in the United States until 1959. The film required Mansfield to sing three songs, but since she was not a trained singer, the studio dubbed Mansfield's voice with that of singer/actress Connie Francis.[56][57] When released in the United States, it became her last mainstream film success. Following The Sheriff of Fractured Jaw Fox tried to cast Mansfield opposite Paul Newman in Rally 'Round the Flag, Boys!, his ill-fated first attempt at comedy. After intense lobbying by Newman and Joanne Woodward she was replaced by Mansfield's Wayward Bus co-star Joan Collins.[58]

Career decline (early 1960s)

Despite her publicity and popularity, Mansfield had no quality film roles after 1959. She was also unable to fulfill a third of her time contracted to Fox because of her repeated pregnancies. Fox stopped viewing her as a major Hollywood star material, and started loaning her out to foreign productions till the end of her contract in 1962. She was first loaned out to English studios and then to Italian studios for a series of low-budget films, many of them obscure and some considered lost.[60][61]

In 1959, Fox cast her in two independent gangster films in England – The Challenge (co-starring Anthony Quayle) and Too Hot to Handle (co-starring Christopher Lee). Both films were low-budget, and their American releases were delayed. Too Hot to Handle was not released in the United States until 1961 (released as Playgirl After Dark), and The Challenge in 1963 (released as It Takes a Thief). In the USA, censors objected to a scene in Too Hot to Handle where Mansfield, wearing sliver netting with sequins painted over her nipples, appeared nearly nude.[62]

When Mansfield returned to Hollywood in mid-1960, 20th Century-Fox cast her in It Happened in Athens (1962). She received first billing above the title, but only appeared in a supporting role. It Happened in Athens starred Trax Colton, a handsome newcomer and an "unknown" whom Fox was trying to mold into a heartthrob. This Olympic Games-based film was shot in Greece in fall 1960, but was unreleased until June 1962. It was a box-office failure, and Mansfield's 20th Century-Fox contract was dropped.

In 1961 Mansfield agreed to play Lisa Lang in The George Raft Story, starring Ray Danton as Raft, because she needed the money and the film was going to be filmed in Hollywood rather than Europe. Soon after the release of The George Raft Story, Mansfield returned to European films. Over the next few years she appeared primarily in low-budget foreign films such as Panic Button (Italy), Heimweh nach St. Pauli (Germany), Einer frisst den anderen (Germany) and L'Amore Primitivo (Italy).

In 1963, Tommy Noonan persuaded Mansfield to become the first mainstream American actress to appear nude in a starring role in the film Promises! Promises!. Nude photographs of Mansfield on the set were published in the June 1963 issue of Playboy, which resulted in obscenity charges against Hugh Hefner in Chicago city court.[63] Promises! Promises! was banned in Cleveland, but enjoyed box-office success elsewhere. As a result of the film's success, Mansfield landed on the Top 10 list of box-office attractions for that year.[64] The autobiographical Jayne Mansfield's Wild, Wild World (which she co-authored with her then-husband, Mickey Hargitay), published immediately after Promises! Promises!, contained 32 pages of black-and-white photographs from the film on glossy paper.[65]

Career end (late 1960s)

Soon after her success in Promises! Promises! Mansfield was chosen from many other actresses to replace the recently-deceased Marilyn Monroe in Kiss Me, Stupid, a romantic comedy which would co-star Dean Martin. She turned the role down due to her pregnancy with daughter Mariska, and was replaced with Kim Novak.

In 1966 Mansfield was cast in Single Room Furnished, directed by then-husband Matt Cimber. The film required Mansfield to portray three different characters, and was Mansfield's first starring dramatic role in several years. It was briefly released in 1966 but did not enjoy a full release until 1968, almost a year after her death. After Single Room Furnished wrapped Mansfield was cast opposite Mamie Van Doren and Ferlin Husky in The Las Vegas Hillbillys, a low-budget comedy from Woolner Brothers. It was her first country and western film which she promoted through 29-day tour of major U.S. cities, accompanied by Ferlin Husky, Don Bowman and other country musicians.[66]

Despite her career setbacks, Mansfield remained a highly-visible celebrity during the early 1960s with her publicity antics and stage performances. In early 1967, Mansfield filmed her last film role: a cameo in A Guide for the Married Man, a comedy starring Walter Matthau, Robert Morse and Inger Stevens. Mansfield received seventh billing as "Girl with Harold".[67] Before her tragic death Mansfield's time was split between nightclub performances and the production of her last film: A Guide for the Married Man, a big-budget production directed by Gene Kelly.

Stage career

Mansfield acted both on stage and in films. She was a student of acting, theater arts and dramatic in college and with Baruch Lumet. She started acting with campus clubs and summer stock theatre. Her first big break was at Broadway with Will success spoil Rock Hunter, for which she won a Theatre World Award as the most promising actress. In her later career she was more busy on stage, performing and making appearances with her nightclub acts, club engagements and performance tours. By 1960, she made personal appearances for everything from supermarket promotion to drug store opening, at $10,000.00 per appearance ($102,992 in 2024 dollars[8]).[68]

Theater

During her tenure at Dallas, she and Paul participated in a number of local theater productions. Between 1951 and 1953 she acted in The Slaves of Demon Rum, Ten Nights in a Barroom and Anything Goes. Her performance in an October 1953 production of Arthur Miller's Death of a Salesman in Dallas, Texas attracted Paramount Pictures to audition her.[69] Lumet trained her for the audition.[15] In 1955, she went to New York and appeared in the Broadway production of George Axelrod's comedy Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter?, also featuring Orson Bean and Walter Matthau. She starred as Rita Marlowe (a wild, blonde Hollywood starlet a la Monroe) in the musical that spoofing Hollywood in general and Marilyn Monroe in particular. Her wardrobe in the play, namely a bath-towel, caused a sensation.[70][71][72] Brooks Atkinson of the New York Times described the "commendable abandon" of her scantily-clad rendition of Rita Marlowe in the play as "a platinum-pated movie siren with the wavy contours of Marilyn Monroe".[73] Her acting drew attention of comedy director Frank Tashlin, who regarded Mansfield as a "living cartoon" and cast in the film version of the play.[4] She performed in 450 shows of the play between 1955-56.[74] She was considered one of the biggest Broadway to Hollywood success stories.[22]

In 1964, she performed in stage productions of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (at Carousel Theater) and Bus Stop (at Yonker Playhouse). Both co-starred Mickey Hargitay and were well-reviewed.[75][76] She toured small towns in the US alternating between the two plays.[77] In 1965, she performed in another pair of plays – Rabbit Habit (at Latin Quarter) and Champagne Complex (at Pabst Theater). Both were directed by Matt Cimbers and were poorly-reviewed.[77][78]

Nightclub

In February 1958, Tropicana Las Vegas launched Mansfield's striptease revue The Tropicana Holiday (produced by Monte Proser, co-starring Mickey Hargitay) under a four weeks contract which was extended to eight.[79][80][81] The opening night raised $20,000.00 for March of Dimes ($211,211 in 2024 dollars[8]). She received $25,000.00 per week for her performance as Trixie Divoon in the show ($264,014 in 2024 dollars[8]), while her contract with 20th Century Fox was paying her $2,500.00 per week ($26,401 in 2024 dollars[8]).[82][83][84] She had a million-dollar policy with Lloyd's of London in case of Hargitay dropping her as he whirled Mansfield around for the show.[85][86] When her film offers disappeared, Mansfield turned to Las Vegas again. In December 1960, Dunes hotel and casino launched Mansfield's revue The House of Love (produced by Jack Cole, co-starring Hargitay). She received $35,000.00 a week as her salary ($360,472 in 2024 dollars[8]), which was the highest in her career.[87][61] Her wardrobe for the shows at Tropicana and Dunes featured a gold mesh dress with sequins to cover her nipples and pubic region.[79][74][88] That controversial sheer dress that was referred to as "Jayne Mansfiled and a few sequins".[82] In early 1963, she performed in her first club engagement outside Las Vegas, at Plantation Supper Club in Greensboro, North Carolina, earning $23,000.00 in a week ($228,900 in 2024 dollars[8]), and then at Iroquois Gardens in Louisville, Kentucky.[89] She returned to Las Vegas in 1966, but her show was staged at Fremont Street, away from the Strip where Tropicana and Dunes was.[79] Her last nightclub act French Dressing was at Latin Quarter in New York in 1966, also repeated at Tropicana.[61] It was a modified version of the Tropicana show, and ran for six weeks with fair success.[90]

Her nightclub career became inspirations for films, documentaries and a musical album. 20th Century Fox Records recorded the The House of Love for an album entitled Jayne Mansfield Busts Up Las Vegas in 1962. In 1966, Matt Cimbers directed The Las Vegas Hillbillys, a low-budget poorly-reviewed film featuring Mansfield, Ferlin Husky and Mamie Van Doren in the lead. Mansfield and her arch-rival Van Doren did not appear in single frame together.[74] Mansfield's wardrobe, in her role as Las Vegas show girl Tawni Downs, consisted of the shapeless styles of the 1960s to hide her weight problems after the birth of her fifth child.[91] In 1967, independent documentary Spree (alternative title Las Vegas by Night) on the antiques of Las Vegas entertainers was released. The film, narrated as a part of a travelogue of Vic Damone and Juliet Prowse, featured Mansfield, Hargitay, Constance Moore and Clara Ward as guest stars. Mansfield strips and sings "Promise Her Anything" from the film Promises! Promises!.[92][93][94] A court order prohibited using any of the guest stars to promote the film.[95][96]

Television career

O, that this too too solid flesh would melt,

Thaw, and resolve itself into a dew.

William Shakespeare

Hamlet (Act I, Scene II)

Mansfield's first leading role on television was with NBC's Sunday Spectacular "The Bachelor" in 1956.[97] In her first appearance on British television in 1957 she recited from Shakespeare (including a line from Hamlet - "Oh that this too, too solid flesh...") and played piano and violin.[98][99] Her notable performances in television dramas included episodes of Burke's Law, Alfred Hitchcock Presents, The Red Skelton Hour (three episodes), Kraft Mystery Theater and Follow the Sun. Mansfield's performance in her first series Follow the Sun ("The Dumbest Blonde"; Season 1, Episode 21; February 4, 1962; produced by 20th Century Fox Television) was hailed as the advent of a "a new and dramatic Jayne Mansfield".[100] She appeared on a number of game shows including Talk it up, Down You Go (as a regular panelist in),[101] The Match Game (one rare episode has her as a team captain), What's My Line? (as a special mystery guest) and It Pays to Be Ignorant.

She performed in a number of variety shows including The Jack Benny Program (on which she played violin), The Steve Allen Show and The Jackie Gleason Show (during the mid-1960s, when the show was the second-highest-rated program in the U.S.).[102] In November 1957, she was portrayed in one of her nightclub acts in a special episode of The Perry Como Show ("Holiday in Las Vegas"), which created "a situation" for the audience according to NBC, the television station that broadcast the show.[103] She was a guest in three episodes of the The Bob Hope Show touring with team. In 1957, she toured United States Pacific Command areas of Hawaii, Okinawa, Guam, Tokyo and Korea with Bob Hope for the United Service Organizations for 13 days appearing as a comedienne;[104] and in 1961, toured Newfoundland, Labrador and Baffin Island for a Christmas special.[105] Her talk show career includes a very large number of talk shows, as she appreciated the publicity and appeared frequently in talk shows.[99] One of her more notable appearances in a talk show was in The Ed Sullivan Show (Season 10, Episode 35; May 26, 1957) right after her success with Rock Hunter. In the show she played violin with a six person back-up.[106] After the show she exclaimed, "Now I am really national. Momma and Dallas see the Ed Sullivan show!"[107]

Gather ye rosebuds while ye may,

Old Time is still a-flying;

And this same flower that smiles today,

Tomorrow will be dying.

By 1958, she charged $20,000.00 per episode for television performance ($211,211 in 2024 dollars[8]).[108] In 1964, Mansfield turned down the role of Ginger Grant on the up-and-coming television sitcom Gilligan's Island, although her acting roles were becoming marginalized, because the part (which eventually went to Tina Louise) epitomized the stereotype of which she wished to rid herself.[109] The widespread rumor that Jayne Mansfield had a breast-flashing dress mishap at the 1957 Academy Awards was found to be baseless by Academy researchers.[110] Ten days before her death, she read To the Virgins, to Make Much of Time, a poem by Robert Herrick about early death on The Joey Bishop Show (Mansfield's last television appearance).[111]

As late as the mid-1980s, Mansfield remained one of the biggest television draws.[112] In 1980, The Jayne Mansfield Story aired on CBS starring Loni Anderson in the title role and Arnold Schwarzenegger as Mickey Hargitay. It was nominated for three Emmy Awards. She was featured in the A&E Television Networks TV series Biography in an episode titled Jayne Mansfield: Blonde Ambition.[113][114] The TV series won an Emmy Award in outstanding non-fiction TV series category in 2001.[115] A&E again featured her life in another TV serial titled Dangerous Curves in 1999.[116] In 1988, her story and archival footage was a part of TV documentary Hollywood Sex Symbols.

Music career

Jayne Mansfield | |

|---|---|

| Genres | Country, pop |

| Occupation | Singer |

| Instrument | Violin |

| Years active | 1954–1967 |

| Labels | 20th Century Fox, MGM, Golden Options, Recall Records, Blue Moon |

| Jayne Mansfield discography | |

|---|---|

| Studio albums | 5 |

| Singles | 10 |

Mansfield had classical training in piano and violin. She sang in English and German for a number of her films, including The Girl Can't Help It ("Ev'rytime" and "Rock Around the Rock Pile"), Illegal ("Too Marvelous for Words"), The Las Vegas Hillbillys ("That makes it"), Too Hot to Handle ("Too Hot To Handle", "You Were Made For Me", "Monsoon" and "Midnight"), Homesick for St. Pauli ("Wo Ist Der Mann" and "Snicksnack Snuckelchen"), The Challenge ("The Challenge of Love"), The Sheriff of Fractured Jaw ("Strolling Down The Lane With Billy" and "If The San Francisco Hills Could Only Talk"), and Promises! Promises! ("I'm in Love", alternative title "Lullaby of Love"). Wo ist der Mann sung in German and released by Polydor Records in Austria was much in demand immediately after its release in August 1963. The A-side featured Hans Last's Scnicksnack-Snuckelchen.[117] In The Sheriff of Fractured Jaw she lip synced to the voice of Connie Francis for "In The Valley Of Love", while signing tow other songs.[118]

In 1958, an orchestra was recorded for the 31st Academy Awards ceremony with Jack Benny on first violin, Jayne Mansfield on violin, Dick Powell on trumpet, Robert Mitchum on woodwind, Fred Astaire on drums and Jerry Lewis as conductor; however, the performance was canceled.[119] She played violin with a six-musician back-up ensemble on The Ed Sullivan Show,[120] and sang "Too Marvelous for Words" for The Jack Benny Program ("Jack Takes Boat to Hawaii"; Episode 9, Season 14; 26 November 1963).

In 1964 Mansfield released a novelty album called Jayne Mansfield: Shakespeare, Tchaikovsky & Me, in which she recited Shakespeare's sonnets and poems by Marlowe, Browning, Wordsworth, and others against a background of Tchaikovsky's music. The album cover depicted a bouffant-coiffed Mansfield with lips pursed and breasts barely covered by a fur stole, posing between busts of Tchaikovsky and Shakespeare.[121] The New York Times described the album a reading of "30-odd poems in a husky, urban, baby voice". The reviewer went on to remark that "Miss Mansfield is a lady with apparent charms, but reading poetry is not one of them."[122]

Jimi Hendrix (one of the most influential musicians of 20th century)[123] played bass and added lead in his session musician days for Mansfield in 1965 on two songs ("As The Clouds Drift By" and "Suey"), released as a 45-rpm single released by London Records in 1966.[124][125] Ed Chalpin, the record producer, claimed that Mansfield played all the instruments on the singles.[126] According to Hendrix historian Steven Roby (Black Gold: The Lost Archives Of Jimi Hendrix, Billboard Books), this collaboration occurred because they shared the same manager.[127][128]

Personal life

Film critic and exploitation movie expert Whitney Williams wrote of Mansfield in Variety in 1967 that "her personal life out-rivaled any of the roles she played".[129] Mansfield was married three times, divorced twice and had five children. She also reportedly had affairs and sexual encounters with numerous individuals, including Claude Terrail (owner of the Paris restaurant La Tour d'Argent),[130] Robert F. Kennedy,[131] John F Kennedy,[132] Brazilian billionaire Jorge Guinle,[133], her attorney Samuel S. Brody and Anton LaVey.[134] She met John F Kennedy through his brother-in-law Peter Lawford at Palm Springs, California in 1960, before he had his affair with Marilyn Monroe, but the "affair" did not last.[135][136][137] She also had a well-publicized relationship in 1963 with singer Nelson Sardelli, whom she said she planned to marry when her divorce from Mickey Hargitay was finalized.[138] At her death Mansfield was accompanied by Sam Brody, her married divorce lawyer and lover at the time.[139][140]

First marriage

Jayne met Paul Mansfield, a popular student at Highland Park High School in Dallas, Texas at a party on Christmas Eve of 1949 when she was 16 and he was 21.[141] On May 6, 1950, she married Paul in Fort Worth, Texas while three months pregnant.[142][143][144][145] On November 8, 1950, Mansfield gave birth to their daughter, Jayne Marie Mansfield.[1] Some sources cite Paul as the father of her child,[142][143] while others allege the pregnancy was the result of date rape.[146][147][148] According to biographer Raymond Strait she had an earlier "secret" marriage on January 28, after which she conceived her first child.[149] Paul hoped the birth of their child would discourage her interest in acting. When it did not, he agreed to move to Los Angeles in late 1954 to help further her career.[150] She juggled motherhood and classes at the University of Texas, then spent a year at Camp Gordon, Georgia while Paul Mansfield served in the United States armed forces. Coming back from the Korean War he took a job with a small newspaper in East Los Angeles, California and lived in a small apartment with Jayne. After a series of marital rows around Jayne's ambitions, infidelity and her animals (a Great Dane, three cats, two Chihuahuas, a poodle, and a rabbit), they were divorced on January 8, 1958.[151][152][153] After the divorce she decided to keep "Mansfield" as her professional name.[154] Paul remarried, settled into the business of public relations, and moved to Chattanooga, Tennessee, while failing win suits to gain custody of Jayne Marie or restraining her from traveling abroad with her mother.[155][156] Two weeks before her mother's death in 1967, 16-year-old Jayne Marie accused her mother's boyfriend at that time, Sam Brody, of beating her.[49] The girl's statement to officers of the Los Angeles Police Department the following morning implicated her mother in encouraging the abuse, and days later a juvenile court judge awarded temporary custody of Jayne Marie to Paul's uncle William W. Pigue and his wife Mary.[157][158][142] Following her 18th birthday, Jayne Marie complained that she had not received inheritance from the Mansfield estate or heard from her father since Jayne's death.[159][160]

Second marriage

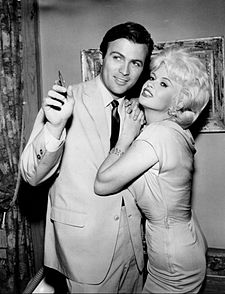

Mansfield met her second husband Mickey Hargitay at the Latin Quarter in New York in May 13, 1956, where he was performing as a member of the chorus line in Mae West's show.[50] She immediately fell for him, which subsequently resulted in a squabble with West.[161][23] The ensuing row had Mr. Calinornia Chuck Krauser beating up Hargitay. Krauser was arrested and released on a $300.00 bond ($3,362 in 2024 dollars[8]).[162] Hargitay was an actor and bodybuilder who had won the Mr. Universe competition in 1955.[163] He proposed to her with a $25,000.00 10-carat diamond ring on November 6, 1957 ($271,209 in 2024 dollars[8]), right after she returned from her 40-day European tour.[164][165] On January 13, 1958, days after her divorce from Paul was finalized, Mansfield and Hargitay married at the Wayfarers Chapel in Rancho Palos Verdes, California. The unique glass chapel made public and press viewing of the wedding easy. Mansfield wore a sensational pink skintight wedding gown made of sequins with a 30 yard flounce.[166][167]

The couple became a popular publicity and performing team, starting with a bit part in Rock Hunter.[61][168] They toured widely in stage shows, where her leopard-spot bikini became a topic of discussion and newspaper coverage.[169][170] Hargitay tossing her around his waist and spinning her in wide circles as a highlight of her shows made more headlines.[171][172] On screen, he was Mansfield's male lead in her Italian ventures – The Loves of Hercules and L'Amore Primitivo, and a major supporting character in Promises! Promises!. On stage, he was the male lead in The Tropicana Holiday, The House of Love, French Dressing and other nightclub acts. They were also popular for their personal appearances in television shows lile Bob Hope Christmas Specials.[61] Towards the very end of life and some time after her divorce with Hargitay, Mansfield told her ex-husband that she was sorry, for all the trouble she gave him, on a television talk show.[173]

Mansfield received her first true negative publicity when she and Hargitay pleaded poverty when Mary Hargitay requested additional child support for Tina Hargitay in September 1958. Mary was Mickey's first wife, divorced in September 6, 1956, and Tina his nine year old first child. Mansfield said that she slept on the floor of her mansion, was unable to buy furniture and spent only $71.00 on Jayne Marie ($796 in 2024 dollars[8]).[174][175][176] During this marriage she had three children, Miklós Jeffrey Palmer Hargitay (born December 21, 1958), Zoltán Anthony Hargitay (born August 1, 1960) and Mariska Magdolna Hargitay (see below). Zoltan was in the news when a lion attacked him and bit his neck while he and his mother were visiting the theme park Jungleland USA in Thousand Oaks, California on November 23, 1967. He suffered from severe head trauma, underwent three surgeries at Community Memorial Hospital in Ventura, California, including a six hour brain surgery, and contracted meningitis. He recovered. Mansfield's attorney Sam Brody sued the theme park on her behalf for $1,600,000.00 ($14,620,359 in 2024 dollars[8]).[50][177][178] The negative publicity led to closure of the theme park.[179]

The couple divorced in Juarez, Mexico, in May 1963, where Nelson Sardelli accompanied Mansfield in her legal preparations.[64] She had previously filed for divorce on May 4, 1962, but told reporters "I'm sure we will make it up."[180] Their acrimonious divorce had the actress accusing Hargitay of kidnapping one of her children to force a more-favorable financial settlement.[181] After their divorce, Mansfield discovered she was pregnant. Since being an unwed mother would have killed her career, Mansfield and Hargitay announced they were still married. Mariska was born January 23, 1964, after the actual divorce but before California ruled it valid.[182] Mariska later became an actress, best known for her role as Olivia Benson in Law & Order: Special Victims Unit. After her birth, Mansfield sued for the Juarez divorce to be declared legal and won. The divorce was recognized in the United States on August 26, 1964.[183] Shortly after Mansfield's funeral, Mickey Hargitay sued his former wife's estate for more than $275,000 ($2.51 million in 2024 dollars[8]) to support the children whom he and his third (and last) wife, Ellen Siano, would raise.[183] Hargitay was appointed the guardian of Micky, Zoltan and Mariska by a court decree in July 1967, though they went on living with their mother.[184] He married airline stewardess Ellen Siano in 1968,[185] who accompanied him to New Orleans when he went to pick up his three children with Mansfield after her death.[186] In January 1969, he lost his claim of $275,533.00 from Mansfield's estate to support the three children ($2,289,274 in 2024 dollars[8]).[187]

Third marriage

Mansfield married Matt Cimber (a.k.a. Matteo Ottaviano, né Thomas Vitale Ottaviano), an Italian-born film director, on September 24, 1964 in Mulegé, Baja California Sur, Mexico. The couple separated on July 11, 1965 and filed for divorce on July 20, 1966.[188] Cimber and Mansfield became involved when he directed her in a widely-praised stage production of Bus Stop in Yonkers, New York (which costarred Hargitay).[189][190] Cimber took over the management of her career during their marriage, and guided her through a series of increasingly tawdry projects like Promises, Promises and The Las Vegas Hillbillys.[4] Her marriage to Cimber worsened in the wake of Mansfield's alcohol abuse, open infidelities and her disclosure to Cimber that she had only been happy with her former lover, Nelson Sardelli. Work on Mansfield's film, Single Room Furnished directed by Cimber (1966) was suspended.[191] The couple had one son, Antonio Raphael Ottaviano (a.k.a. Tony Cimber, born October 18, 1965). Mansfield's youngest child Tony was raised by his father, Matt Cimber, whose divorce from the actress was pending when she was killed.

Death

In Biloxi, Mississippi for an engagement at the Gus Stevens Supper Club, Mansfield stayed at the Cabana Courtyard Apartments near the club. After an evening engagement on June 28, 1967, Mansfield, her lover Sam Brody, their driver, Ronnie Harrison and the actress's children (Miklós, Zoltán and Mariska) set out in Stevens' 1966 Buick Electra 225 for New Orleans, where Mansfield was scheduled to appear for an early-morning television interview. Before leaving Biloxi, the party made a stop at the home of Rupert and Edna O'Neal (a family who lived nearby). After a late dinner with the O'Neals (during which Mansfield's last photographs were taken), the party set out for New Orleans. On June 29 at approximately 2:25 a.m., on U.S. Highway 90, east of the Rigolets Bridge, the car crashed into the rear of a tractor-trailer which had slowed for a truck which was spraying mosquito fogger. The automobile struck the rear of the trailer and went under it. The three adults in the front seat were killed instantly; the children, in the rear, survived with minor injuries.[192]

Allegations that Mansfield was decapitated are untrue, although she suffered severe head trauma. The urban legend was spawned by the appearance in police photographs of a crashed automobile with its top virtually sheared off, and what resembled a blonde-haired head tangled in the car's smashed windshield. However, this was probably either a wig Mansfield was wearing or her actual hair and scalp.[193] The death certificate stated that the immediate cause of Mansfield's death was a "crushed skull with avulsion of cranium and brain".[194] After her death, the NHTSA began requiring an underride guard (a strong bar made of steel tubing) on all tractor-trailers. This bar is known as a Mansfield bar, or an ICC bar.[195][196]

Mansfield's funeral took place on July 3 in Pen Argyl, Pennsylvania. Her last rites were conducted by Rev. Charles Montgomery, a pastor of the Zion Methodist Church (destroyed by fire in February 1970 and rebuilt as Grace United Methodist Church),[197] in a private service at the chapel of the Pullis Funeral Home.[198] Of her three husbands, only Mickey Hargitay was present at the funeral.[199] She is interred in Fairview Cemetery, southeast of Pen Argyl, beside her father Herbert William Palmer. Her heart-shaped gravestone reads, "We Live to Love You More Each Day". A cenotaph was placed in the Hollywood Forever Cemetery in Hollywood by the Jayne Mansfield Fan Club incorrectly citing her year of birth as 1938 (Mansfield tended to provide incorrect information about her age). In 1968, two wrongful-death lawsuits were filed on behalf of Jayne Marie Mansfield and Matt Cimber. The former for $4.8 million ($52.1 million in 2024 dollars[8]) and the latter for $2.7 million ($29.3 million in 2024 dollars[8]).[200]

Recognition

- Mansfield won many local beauty pageants, including Miss Photoflash, Miss Magnesium Lamp, Miss Fire Prevention Week, Gas Station Queen, Miss 100% Pure, Miss Analgesin, Miss Cherry Blossom Queen, Miss Third Platoon, Miss Blues Bonnet of Austin, Miss Direct Mail, Miss Electric Switch, Miss Fill-er-up, Miss Negligee, Miss Nylon Sweater, Miss One for the Road coffee, Miss Freeway, Miss Electric Switch, Miss Geiger Counter, Miss 100% Pure Maple Syrup, Miss July Fourth, Miss Texas Tomato, Miss Standard Foods and Miss United Dairies.[202][203]

- In February 1955 Mansfield was the Playmate of the Month in Playboy,[38] in which she subsequently appeared over 30 times.[204]

- She received a Theatre World Award (Promising Personality) for Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? in 1956 .[205]

- Photoplay awarded Mansfield a Gold Medal Award as one of the most promising young actresses of 1956-1957.[206]

- She received a Golden Globe (New Star of the year, Actress) for Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? in 1957.[207][208]

- Mansfield won a Golden Laurel in 1959 for Top Female Musical Performance in The Sheriff of Fractured Jaw, a western spoof directed by Raoul Walsh,[209] although the songs were performed by Connie Francis.[56][57]

- On Mother's Day of 1960, the Mildred Strauss Child Care Chapter of Mount Sinai Hospital, New York declares her family as the "Family of the Year".[210]

- Italian film, radio and television journalists awarded her the Silver Mask award in 1962.[211]

- Mansfield received the Oscar of the Two World award in Italy.[212][213]

- In 1963, Mansfield was voted one of the top-10 box-office attractions by an organization of American theater owners for her performance in Promises! Promises! (a film banned in parts of the U.S.).[64][214]

- In 1968, Hollywood Publicists Guild declared a "Jayne Mansfield Award" will given to the actress who received the maximum exposure and publicity in an year.[202] Raquel Welch was the first winner of the award in 1969.[215]

Image

Mansfield's hourglass figure (she claimed dimensions of 40-21-35), unique sashaying walk, breathy baby talk and cleavage-revealing costumes made a lasting impact on popular culture.[26] From 1955 until the early 1960s, she was seen as Hollywood's gaudiest, boldest D-cupped B-grade actress.[216] A natural brunette, Mansfield had her hair dyed platinum blonde when she moved to Los Angeles,[217] and became one of the early "blonde bombshells" (along with Marilyn Monroe, Betty Grable and Mamie Van Doren).[218][219][220][221] In 1958, she also had her eyebrows dyed platinum.[202] Following Jean Harlow (who started the trend with her film Bombshell),[222][223] Monroe, Mansfield and Van Doren helped establish the stereotype typified by a combination of curvaceous physique, very light-colored hair and a perceived lack of intelligence.[224] Instead of asexualized and virginal "nice girls" of earlier films, the pneumatic blonde bombshells took over the screen in 1950s to become a cult that is consistently emulated from that era onward.[225][226] A review of English language tabloids has shown it to be one of the most persistent blonde stereotype along with "busty blonde", and "blonde babe".[227] At one point, Monroe, Mansfield and Mamie came to be known as "The Three M's".[228][229] Monroe, Mansfield, Judy Holliday and Goldie Hawn is also identified to have established the stereotype of the "dumb blonde",[230] typified by their combination of overt sexuality and apparent inability to understand everyday life.[231]

Because of her striking figure, newspapers in the 1950s routinely published her body measurements, which once led to evangelist Billy Graham exclaiming, "This country knows more about Jayne Mansfield's statistics than the Second Commandment."[3] Mansfield claimed a 41-inch bust line and a 22-inch waist when she made her Broadway debut in 1955, though some scholars dispute those figures.[232] She came to be known as "the Cleavage Queen" and "the Queen of Sex and Bosom".[233] Mansfield's breasts fluctuated in size, it was said, from her pregnancies and nursing her five children. Her smallest measurement was 40D (102 cm), which was constant throughout the 1950s, and her largest was 46DD (117 cm), measured by the press in 1967.[234] According to Playboy, her vital statistics were 40D-21-36 (102-53-91 cm) on her 5'6" (1.68 m) frame.[38] According to her autopsy report, she was 5'8" (1.73 m).

20th Century Fox groomed Mansfield as well as Sheree North to substitute Monroe, their resident "blonde bombshell", while Universal Pictures launched Van Doren as their substitute.[235] The studio launched Mansfield, their new bombshell, with a grand 40-day tour of England and Europe from September 25 to November 6, 1957.[236] Columbia Pictures tried the same with Cleo Moore, Warner Bros. with Carroll Baker, Paramount Pictures with Anita Ekberg, and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer with Barbara Lang,[237] while Diana Dors was dubbed as England's answer to Mansfield.[238] Jacqueline Susann wrote, "When one studio has a Marilyn Monroe, every other studio is hiring Jayne Mansfield and Mamie Van Doren."[239] But, even when Mansfield's film roles were drying up, she was widely considered to be Monroe's primary rival in a crowded field of contenders which included Mamie Van Doren (whom Mansfield considered her professional nemesis),[240] Diana Dors, Sheree North, Kim Novak, Cleo Moore, Joi Lansing, Beverly Michaels, Barbara Nichols and Greta Thyssen, and even two brunettes – Elizabeth Taylor and Jane Russell.[241][242][243]

Throughout her career, Mansfield was compared by the media to the reigning sex symbol of the period, Marilyn Monroe.[24] She adopted Monroe's vocal mannerisms instead of her husky voice and Texan speech,[232] performed in two plays that were based on Marilyn Monroe vehicles – Bus Stop and Gentlemen Prefer Blondes,[244] and her role in The Wayward Bus was strongly influenced by Monroe's character in Bus Stop.[77] Mamie Van Doren, Diana Dors and Kim Novak also acted in various productions of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes.[245] But as the 1960s approached, the anatomy that had made her a star turned her into a joke.[232] In this decade, the female body ideal shifted to appreciate the slim waif-like features popularized by supermodel Twiggy, actress Audrey Hepburn and other, demarcating the demise of the busty blonde bombshells.[226][246][247]

Publicity

Mansfield's publicity drive was one of the best in Hollywood. For publicity gave up all privacy keeping her doors always open to photographers.[248][68] In 1954, the day before Christmas she walked into publicist James Byron's office with a gift and asked him to supervise her publicity.[68] From that time till the end of 1961, Byron shaped much of her publicity.[249] Byron appointed most people in her team – William Shiffrin (press agent), Greg Bautzer (attorney) and Charles Goldring (business manager),[250] and constantly planted bits of publicity material in the media.[248] She appeared in about 2,500 newspaper photographs between September 1956 and May 1957, and had about 122,000 lines of newspaper copy written about her during this time.[3] Because of the successful media blitz, she quickly became a household name. In 1960, Mansfield topped press polls for more words in print than anyone else in the world, made more personal appearances than a political candidate,[68] and was regarded as the world's most-photographed Hollywood celebrity.[74]. She made news on a regular basis, from dresses falling off to clothing which burst strategically at the seams to the lowest cut dresses worn with a bra.[248][251] Things started to get over the top even in her standards when she took charge of her own publicity without advice. James Bacon wrote in the Los Angeles Herald-Examiner in 1973, "Here was a girl with real comedy talent, spectacular figure and looks and yet ridiculed herself out of business by outlandish publicity".[252]

Publicity stunts

In January 1955 Mansfield appeared at a Silver Springs, Florida press junket promoting the film Underwater!, starring Jane Russell. Mansfield purposely wore a too-small red bikini, lent her by photographer friend Peter Gowland. When she dove into the pool for photographers her top came off, which created a burst of media attention. The ensuing publicity led to Warner Bros. and Playboy approaching her with offers.[3][142][254][255] In June 8 of the same year, her dress fell down to her waist twice in a single evening – once at a movie party, and later at a nightclub.[256] In February 1958, she was stripped to waist at a Mardi Gras party in Rio de Janeiro.[257][23][258] In June 1962, she shimmied out of her polka-dot dress in a Rome nightclub.[259][260] In the three years since making her Broadway debut in Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter?, Mansfield had become the most controversial star of the decade.[251]

In April 1957, her bosom was the focus of a notorious publicity stunt intended to deflect media attention from Sophia Loren during a dinner party in the Italian star's honor. Photographs of the encounter were published around the world. The best-known photo showed Loren's gaze falling on the cleavage of the American actress (who was seated between Loren and her dinner companion, Clifton Webb) when Mansfield leaned over the table, allowing her breasts to spill over her low neckline and exposing one nipple.[261] Several similar photos were taken in a short time. Fearful of public outrage, most Italian newspapers refused to print the wirephotos; Il Giorno and Gazzetta del Popolo printed them after retouching to cover much of Mansfield's bosom, and only Il Giornale d'Italia printed them uncensored.[262] The photo inspired a number of later photographers. In 1993, Daniela Federici created an homage with Anna Nicole Smith as Mansfield and New York City DJ Sky Nellor as Loren for a Guess Jeans campaign.[263] Later, Mark Seliger took a picture named Heidi Klum at Romanoff's with Heidi Klum in a reproduction of the restaurant set.[264] A similar incident (resulting in the exposure of both breasts) occurred during a film festival in West Berlin, when Mansfield was wearing a low-cut dress and her husband, Mickey Hargitay, picked her up so she could bite a bunch of grapes hanging overhead at a party. The movement exposed both her breasts. The photograph of that episode was a UPI sensation, appearing in newspapers and magazines with the word "censored" hiding the actress's exposed bosom.[265]

At the same time, the world's media were quick to condemn Mansfield's stunts. One editorial columnist wrote, "We are amused when Miss Mansfield strains to pull in her stomach to fill out her bikini better; but we get angry when career-seeking women, shady ladies, and certain starlets and actresses...use every opportunity to display their anatomy unasked".[40] By the late 1950s, Mansfield began to generate a great deal of negative publicity because of repeated exposure of her breasts in carefully-staged public "accidents". Richard Blackwell, her wardrobe designer (who also designed for Jane Russell, Dorothy Lamour, Peggy Lee and Nancy Reagan), dropped her from his client list because of those accidents.[266]

Signature color

Mansfield adopted pink as her color in 1954, associating herself with that color for the rest of her career.[1][267] Her original choice was purple, but she thought it too close to lavender, Kim Novak's signature color.[1] "It must have been the right decision," she said, "because I got more column space from pink than Kim Novak ever did from lavender."[267] For her wedding to Hargitay she wore a tight-fitting gown of pink lace with a flounce of 30 yards of pink tulle (designed by a 20th Century-Fox costume designer),[268] and at the reception she had Hargitay drink pink champagne.[269] In November 1957 (shortly before their marriage), Mansfield bought the 40-room Mediterranean-style mansion (formerly owned by Rudy Vallée) at 10100 Sunset Boulevard in Beverly Hills. Much of the money to buy the house came from her inheritance from Elmer Palmer, her maternal grandfather.[61][270] Mansfield had the house painted pink, with cupids surrounded by pink fluorescent lights, pink fur in the bathrooms, a pink heart-shaped bathtub and a fountain spurting pink champagne; she then dubbed it the "Pink Palace". Hargitay (a plumber and carpenter before taking up bodybuilding) built a pink heart-shaped swimming pool. The year after reconstructing the "Pink Palace" as a "pink landmark" she began riding a pink Cadillac Eldorado Biarritz convertible with tailfins, then the only pink Cadillac in Hollywood.[271][272][273] Though Elvis Presley's Pink Cadillac came about in 1955, it was in Memphis, Tennessee.

Religion

In August 1963, Jayne Mansfield decided to convert to Catholicism.[274][78] Although never actually converting, she attended Catholic masses when she was in Europe,[275] and followed Catholic practices when she was involved with a Catholic partner (including Hargitay, Sardelli and Cimber).[276][277] In May 1967, her performance at the Mount Brandon Hotel in Tralee, Ireland, was canceled because Catholic clergy condemned it.[278] She wanted to marry Cimber in a Catholic church, but was unable to find a priest to perform the ceremony.[279] While involved with Brody, she also showed interest in Judaism.[78] In San Francisco for the 1966 Film Festival, Mansfield visited the Church of Satan with Sam Brody (her lawyer and boyfriend) to meet Anton LaVey, the church's founder. LaVey awarded Mansfield a medallion and the title "High Priestess of San Francisco's Church of Satan", and put a death curse on Brody because he "desecrated" the Church. The Church of Satan proclaimed Jayne a pledged member, and she displayed a framed membership certification in her pink bedroom. The media enthusiastically covered the meeting and the events surrounding it, identifying her as a Satanist and romantically involved with LaVey.[280][281][282] That meeting remained a much-publicized and oft-quoted event of her life, as well as the history of the Church of Satan.[283][284] Her funeral ceremony was conducted by a Methodist minister.[78]

Legacy

Mansfield left behind five children, three ex-husbands, a crumbling estate including the Pink Palace, a large number of followers, and a lasting impact on popular culture.

Cultural impact

Social historian Joan Jacobs Brumberg described the 1950s as "an era distinguished by its worship of full-breasted women" and attributes the paradigm shift to Mansfield and Monroe.[285] Patricia Vettel-Becker made that observation more specific by attributing the phenomenon to Playboy and the appearance of Mansfield and Monroe in the magazine.[286] R. L. Rutsky[287] and Bill Osgerby[288] has claimed that it was Mansfield, along with Marilyn Monroe and Brigitte Bardot, who made the bikini popular. M. Thomas Inge describes Mansfield, Monroe and Jane Russell as personification of the bad girl in popular culture.[289] Mansfield, Monroe and Barbara Windsor have been described as representations of a historical juncture of sexuality in comedy and popular culture.[290] Academics also added Anita Ekberg and Bettie Page to the list of catalysts of the trend of exaggerated female sexuality, besides Mansfield and Monroe.[291][292] Drawing on the Freudian concept of fetishism, British science fiction writer and socio-cultural commentator J. G. Ballard commented that Mae West, Mansfield and Monroe's breasts "loomed across the horizon of popular consciousness."[293] It has been claimed that her bosom was a major force behind the development of the 1950s brassieres, including the "Whirlpool bra", Cuties, the "Shutter bra", the "Action bra", latex pads, cleavage-revealing designs and uplift outline.[294][295]

Estate

After Mansfield's death, Hargitay, Cimbers, Vera Peers (Jayne Mansfield's mother), William Pigue (Jayne Marie's legal guardian) and Charles Goldring (business manager), as well as Bernard B. Cohen and Jerome Webber (both administrators of the estate) filed suits to gain control of her estate without success.[296][297][298] Mansfield's estate was appraised initially at $600,000.00 ($4,514,051 in 2024 dollars[8]), including the "Pink Palace" estimated at $100,000.00 ($752,342 in 2024 dollars[8]), a sports car sold for $7,000.00 ($52,664 in 2024 dollars[8]), her jewellery, and Sam Brody's $185,000.00 estate left to her by his last testimony ($1,391,832 in 2024 dollars[8]),[299][300] However, four of her elder children (Jayne Marie, Mickey, Zoltan and Mariska) went to court in 1977 to find that about $500,000.00 in debt ($3,761,709 in 2024 dollars[8]), including $11,000.00 for lingerie ($82,758 in 2024 dollars[8]) and $11,600.00 for plumbing of the heart-shaped swimming pool ($87,272 in 2024 dollars[8]), and litigation left the estate insolvent.[301] The Pink Palace was sold. Its subsequent owners included Ringo Starr, Cass Elliot and Engelbert Humperdinck.[302] In 2002 Humperdinck sold it to developers, and the house was demolished in November of that year.[303] What remains of her estate is managed by CMG Worldwide, an intellectual property-management company.[304]

Following

Several entertainers have been dubbed as the "new Jayne Mansfield", including Italian actress Marisa Allasio and professional wrestler Missy Hyatt.[305][306][307] Actress, model and Playmate of the Year (1993) Anna Nicole Smith was dubbed "a Jayne Mansfield for the '90s"[308][309] because of her physical resemblance to Mansfield that was capitalized by Guess jeans, similar desperation, and a mix of glamor and tragedy.[310][311][312][313] Drag queen and actor Divine was selected by film maker John Waters to parody Mansfield in Mondo Trasho, who considered Mansfield for her close resemblance to Marilyn Monroe.[314] By the mid-1950s, there were many Jayne Mansfield fanclubs in United States and outside.[315] The Jayne Mansfield Fan Club, headed by Sabin Gay was very active in the 1980s, and was cited by Daily News of Los Angeles as one of the major fan clubs for a Hollywood star.[316] In 1992, a second fan club named Simply Davoon was founded by Mike DiGiacomo, which lent its picture collection to Jocelyn Faris to illustrate Jayne Mansfield: A bio bibliography.[1] Frank Ferruccio, head of Mansfield's Online Fan Club, lent his collection of Mansfield memorabilia to Slate Belt Heritage Center in Bangor, Pennsylvania, wrote two books on her, and organized a large fan gathering on her 75th birthday at Fairview Cemetery.[317][318]

See also

References

- Strait, Raymond (1992). Here They Are Jayne Mansfield. New York: S.P.I. Books. ISBN 978-1-56171-146-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Faris, Jocelyn (1994). Jayne Mansfield: A Bio-Bibliography. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-28544-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Mann, May (1974). Jayne Mansfield: A biography. Abelard-Schuman. ISBN 978-0-200-72138-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Saxton, Martha (1975). Jayne Mansfield and the American Fifties. New York: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-20289-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Luijters, Guus (1988). Sexbomb: The Life and Death of Jayne Mansfield. Secaucus, NJ: Citadel. ISBN 978-0-8065-1049-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - "Jayne Mansfield: Blonde Ambition", a documentary broadcast on the A&E Network in 2004.

- "Jayne Mansfield Biography", biography.com

Citations

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Faris 1994, p. 3

- ^ Rudnick, Paul (June 14, 1999). "Heroes and Icons: Marilyn Monroe". Time.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ a b c d Russell, Dennis (2000). "Jayne Mansfield". In Pendergast, Tom; Pendergast (eds.). St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Vol. 3. Farmington Hills, Michigan: St. James Press, Gale. pp. 250–261. ISBN 1-55862-405-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); More than one of|editor2=and|editor2-last=specified (help) - ^ a b c d e Erickson url=http://movies.nytimes.com/person/45173/Jayne-Mansfield/biography, Hal (May 22, 2012). "Jayne Mansfield". New York Times.

{{cite news}}: Missing pipe in:|last=(help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Strait 1992, p. 10

- ^ Kent, Alan M (2004). Travels in Cornish America: Cousin Jack's Mouth-organ.

- ^ a b "Jayne Mansfield, Mickey Pause in Dallas for Party". Star-News. January 15, 1958. p. 4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ "Jayne Mansfield to get $90,000.00"". Beaver Valley Times. p. 15.

{{cite news}}: Text "January 23, 1957" ignored (help). - ^ "Jayne Mansfield Is Killed In Early Morning Smash up on Narrow Louisiana Road"". St. Petersburg Times. June 30, 1967.

Born Vera Jayne Palmer in Bryn Mawr, Pa., April 19, 1933, Miss Mansfield grew up in Phillipsburg, N.J.

- ^ "Vera Peers Buried in Pen Argyl Near Daughter Jayne Mansfield". Los Angeles Times. November 19, 2000.

- ^ Highland Park High School: The Highlander. 1949.

- ^ "Names in Yearbook", Dallas Public Library, City of Dallas

- ^ Miller, Bobbi (September 25, 1988). "Highland Park High Alumni Have Gone on to Greatness". The Dallas Morning News.

- ^ a b c d e Commire, Anne; Klezmer, Deborah (2001). Women in World History: A Biographical Encyclopedia. Yorkin. p. 185-186. ISBN 9780787640699.

{{cite book}}: Text "volume 10" ignored (help) - ^ a b c Garraty, John Arthur; Carnes, Mark Christopher (1999). American National Biography. Oxford University. p. 450. ISBN 9780195127935.

- ^ a b "Jayne Mansfield Killed". The Deseret News. June 29, 1967. p. 1.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|agancy=ignored (help) - ^ Hopper, Hedda (November 25, 1956). "Jayne Shapes Up Her Career". Los Angeles Times. p. 2.

- ^ Strait 1992, p. 217

- ^ Havemann, Ernst (April 23, 1956). "Star's Legend". Life: 186.

- ^ Strait 1992, p. 37

- ^ a b c d Johnson, Erskine (January 10, 1957). "Jayne Mansfield: Darling of Bust". Sarasota Journal: 7.

- ^ a b c d "Jayne Mansfield Dead". The Windsor Star. UPI. June 29, 1967. p. 6,.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ a b Mann 1974, p. 112

- ^ a b c Peter Partheymuller, "Jayne Manfield", page 25, The Alcalde, March 2000.

- ^ a b c d e f Parish, James Robert (2007). The Hollywood Book of Extravagance. John Wiley & Sons. p. 44-45. ISBN 978-0-470-05205-1..

- ^ Crosby, Joan (August 14, 1965). "Fantastics a Runaway Success". Ottawa Citizen. p. 3.

- ^ Parker, Fess. "Guest Star of the 1970 Emerald Empire Roundup". Eugene Register-Guard. p. 3.

{{cite news}}: Text "July 6, 1970" ignored (help) - ^ a b c d National Board of Review of Motion Pictures, Films in review (Volume 27), pages 321323, 1976

- ^ Richard Pearce-Moses(Texas Historical Foundation), Photographic collections in Texas: A union guide, page 133, Texas A&M University Press (Texas Historical Foundation), 1987 ISBN 978-0-89096-351-7.

- ^ Saxton 1975, pp. 38–39

- ^ Helen Muir, "Barush Lumet taught stars how to act", The Miami News, page 9, 1963-02-17.

- ^ Mann 1974, p. 12

- ^ John Tibbetts and James Welsh, American Classic Screen Features, page 13, Scarecrow Press, 2010, ISBN 978-0-8108-7679-8

- ^ Jordan, Jessica Hope (2009). The Sex Goddess In American Film 1930–1965: Jean Harlow, Mae West, Lana Turner and Jayne Mansfield. Cambria Press. p. 221. ISBN 978-1-60497-663-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Saxton 1975, pp. 10, 17, 148, 155

- ^ Jayne Mansfield indexed, Salon.

- ^ a b c d e "Playboy Data Sheet: Jayne Mansfield, Miss February 1955". Playboy. Retrieved August 6, 2008.

- ^ Saxton 1975, p. 48

- ^ a b Strait 1992, p. 116

- ^ Louella Parsons, "Outlook for young star is bright", The Sunday News-Press, page 4, 1956-01-01

- ^ Biography news (Volume 1), p. 173, Gale Research Co., 1974.

- ^ Brady, Frank (1975). Hefner. Weidenfeld and Nicolson. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-297-76943-9.

- ^ Playboy Collector's Association Playboy Magazine Price Guide.

- ^ Saxton 1975, p. 175

- ^ Faris 1994, p. 4

- ^ Reid, John (2005). Cinemascope Two: 20th Century Fox. Lulu.com. p. 84. ISBN 978-1-4116-2248-7.

- ^ Cochran, Bobby; VanHecke, Susan (2003). Three steps to heaven: the Eddie Cochran story. Hal Leonard. ISBN 978-0-634-03252-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Jayne Mansfield Dies in New Orleans Car Crash". The New York Times. June 30, 1967. p. 33.

- ^ a b c Faris 1994, p. 6

- ^ Saxton 1975, pp. 91

- ^ Mann 1974, p. 58-59

- ^ Saxton 1975, p. 13

- ^ Shipman, David (1980). The great movie stars, the international years. Angus & Robertson. p. 349.

- ^ Donnelly, Paul (2003). Fade to black: a book of movie obituaries. Omnibus. p. 452. ISBN 978-0-7119-9512-3.

- ^ a b Michael Haggiag (edited by Phil Hardy), The Western: Film Encyclopedia (Volume 1), page 270, W. Morrow, 1983, ISBN 978-0-688-00946-5

- ^ a b James Robert Parish and Michael R. Pitts, Hollywood Songsters, page 321, Routledge, 2003, ISBN 9780415943321

- ^ Jeff Rovin, Joan Collins: The unauthorized biography, page 89, Bantam Books, 1984, ISBN 9780553249392

- ^ Black, Gregory D. (January 26, 1996). Hollywood Censored: Morality Codes, Catholics, and the Movies (Cambridge Studies in the History of Mass Communication). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-56592-9.

- ^ Abbe A. Debolt and James S. Baugess, Encyclopedia of the Sixties: A Decade of Culture and Counterculture, page 391, ABC-CLIO, 2011, ISBN 978-1-4408-0102-0

- ^ a b c d e f Faris 1994, p. 24 Cite error: The named reference "farisclub" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Jessica Hope Jordan, The Sex Goddess in American Film, 1930-1965, page 167, Cambria Press, 2009, ISBN 978-1-60497-663-2

- ^ Karl Klockars (April 10, 2009). "Friday Flashback: Hef's Obscenity Battle". Chicagoist.com. Retrieved January 25, 2011.

- ^ a b c Faris 1994, p. 10

- ^ Mansfield, Jayne; Hargitay, Mickey (1963). Jayne Mansfield's Wild, Wild World. Los Angeles: Holloway House. OCLC 9922763.

- ^ "J. Mansfield to promote C&W movie", [Billboard (magazine)|Billboard]], page 56, 22 Oct 1966

- ^ Burchill, Julie (April 12, 2003). "Desperately seeking attention". The Guardian.

- ^ a b c d James Bacon, "Jayne shapes own publicity", The Miami News, pages 1 and 8, 1962-02-08

- ^ Steve Sullivan, Va Va Voom, p.50, General Publishing Group, 1995, ISBN 9781881649601

- ^ James Bacon, "Actress Made Herself Famous", page 3A, The Miami News, 1962-02-08

- ^ Mann 1974, p. 36

- ^ Marianne Ruuth, Cruel city: the dark side of Hollywood's rich and famous, page 157, Roundtable Publishing, 1991, ISBN 978-0915677481

- ^ Atkinson, Brooks (October 14, 1955). "Theatre: Axelrod's Second Comedy". The New York Times. p. 22.

- ^ a b c d Jeff Burbank, Las Vegas Babylon, pages 113-114, Franz Steiner Verlag, 2007, ISBN 9781861059666

- ^ "The voice of Kevin Kelly", The Boston Globe, 1994-11-30, p. 65

- ^ "Row Over Screen Censorship Goes On", The New York Times, 1958-06-01

- ^ a b c Faris 1994, pp. 74

- ^ a b c d Strait 1992, p. 11

- ^ a b c Mike Weatherford, Cult Vegas: The Weirdest! The Wildest! The Swingin'est Town on Earth!, pages 230-232, Huntington Press Inc, 2001, ISBN 9780929712710

- ^ Strait 1992, p. 107

- ^ Ashley Powers, "Putting a top on iconic topless show", Boston.com

- ^ a b Strait 1992, p. 94

- ^ Harrison Carrol, "Behind scenes in Hollywood", The Billings County Pioneer, page 2, 1958-01-02.

- ^ :Jayne, Mickey appears in Las Vegas revue", Oxnard Press-Courier, page 10, 1958-02-11.

- ^ "Swings his bride", The Tuscaloosa News, page 26, 1958-04-10.

- ^ Faris 1994, p. 45

- ^ Strait 1992, p. 110

- ^ Faris 1994, p. 46

- ^ Strait 1992, pp. 161–163

- ^ Faris 1994, p. 56

- ^ Faris 1994, p. 105

- ^ Saxton 1975, pp. 160

- ^ Faris 1994, p. 108

- ^ Strait 1992, p. 161

- ^ Kevin Thomas, "Spree features visit to Las Vegas", Los Angeles Times, page 1, 1967-06-23.

- ^ James Robert Parish and Michael R. Pitts, Hollywood Songsters, page 212, Routledge, 2003, ISBN 9780415943321

- ^ Louella O Parsons, "Jayne Mansfield's billing now above that of play", St. Petersburg Times, page 9, 1956-06-07

- ^ "Fat For Britains", Titusville Herald, page 1, September 30, 1957

- ^ a b Faris 1994, p. 113

- ^ Strait 1992, p. 118

- ^ Norman Chance, Who Was Who on TV (Volume 1), page 388, Xlibris Corporation, 2010, ISBN 9781456821272

- ^ Brooks, Tim and Marsh, Earle (2007). The Complete Directory to Prime Time Network and Cable TV Shows 1946–Present. Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-49773-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Robert Pondillo, America's First Network TV Censor: The Work of NBC's Stockton Helffrich, page 166, SIU Press, 2010, ISBN 9780809329182

- ^ Faris 1994, pp. 118, 153

- ^ Faris 1994, pp. 25, 49, 123

- ^ Saxton 1975, p. 87

- ^ Mann 1974, p. 212

- ^ Walter Winchell, "Jayne asks $20,000.00 per TV performance", Star-News, page 6, 1958-06-23.

- ^ Anika Logan, "Jayne Mansfield - The Poor Man's Marilyn Monroe", Rewind the 50's.

- ^ Tim Molloy, "Shattered TV Taboos: How Bea Arthur and Others Broke Barriers", TV Guide, 2009-04-27

- ^ Faris 1994, p. 126

- ^ Gitlin, Todd (1994). Inside Prime Time. Routledge. p. 196.

- ^ "Jayne Mansfield set/Some Like It Hot". Review. Hollywood Reporter. August 18, 2006.

- ^ "Jayne Mansfield". Biography. A&E Television Networks. Retrieved July 14, 2008.

- ^ "2001–2002 Emmy Awards". Infoplease. Pearson PLC. Retrieved July 14, 2008.

- ^ Zad, Martie (May 18, 1999). "Hollywood's Dangerous Curves". Review. Washington Post.

- ^ "Austria", [Billboard (magazine)|Billboard]], page 38, Aug 10, 1963

- ^ Alan Gevinson, Within Our Gates: Ethnicity in American Feature Films, page 914, University of California Press, 1997, ISBN 9780520209640

- ^ "Jack and Jayne got ax on Oscar night", page 8, Billboard, 1958-04-07.

- ^ Saxton 1975

- ^ Welcome to Raymondo's Dance-o-rama. triad.rr.com Retrieved December 13, 2006.

- ^ Lask, Thomas (August 30, 1964). "Poetry: Revised Editions". The New York Times. p. X21.

- ^ "Jimi Hendrix". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved April 11, 2009.

- ^ Henderson, David (2009). Scuse Me While I Kiss the Sky. Simon and Schuster. p. 85. ISBN 9780743274012.

- ^ González, Ray (2008). Renaming the Earth. University of Arizona. p. 43. ISBN 9780816524105.

- ^ Geldeart, Gary; Rodham, Steve (2008). The Complete Guide to the Recorded Work of Jimi Hendrix. Vol. 1. Jimpress. p. 32. ISBN 9780952768654.

- ^ "Episode 46 – The Girl Can't Help It"; Retrieved December 11, 2007.

- ^ "Jimi Hendrix And Jayne Mansfield: The Untold Story"; Retrieved December 11, 2007.

- ^ Faris 1994, pp. 7, 235

- ^ Strait 1992, p. 198

- ^ Strait 1992, pp. 153–157, 177–190

- ^ Kroth, Jerome A. (2003). Conspiracy in Camelot. Algora. p. 263. ISBN 978-0-87586-246-0.

- ^ Strait 1992, p. 156

- ^ Urban, Hugh B. (2006). Magia sexualis: sex, magic, and liberation in modern Western esotericism. University of California Press. p. 214. ISBN 978-0-520-24776-5.

- ^ Wesley O. Hagood, Presidential Sex: From the Founding Fathers to Bill Clinton, page 163, Wesley Hagood, 1998, ISBN 9780806520070

- ^ John Boertlein, Presidential Confidential: Sex, Scandal, Murder and Mayhem in the Oval Office, page 151, Clerisy Press, 2010, ISBN 9781578603619

- ^ Michael John Sullivan, Presidential Passions: The Love Affairs of America's Presidents, page 69, SP Books, 1994, ISBN 9781561710935

- ^ Strait 1992, pp. 167–8, 170, 173–4, 195, 197, 202, 203, 207, 208, 224–5

- ^ Strait 1992, p. 185

- ^ Jordan 2009, p. 222

- ^ Strait 1992, pp. 50–55

- ^ a b c d Faris 1994, pp. 3, 197

- ^ a b Saxton 1975, p. 29

- ^ AP, "Jayne Mansfield's hunsband asks divorce", Times Daily, page 11, 1957-01-04.

- ^ "Jayne Mansfield (Vera Jayne Peers) Marriage Certificate". Archives.com. Houston: Texas State Department of Health Services. 1950. Retrieved March 9, 2012.(subscription required)

- ^ Mann 1974, pp. 10–12