Uzbekistan

Republic of Uzbekistan O‘zbekiston Respublikasi Ўзбекистон Республикаси | |

|---|---|

| Anthem: O‘zbekiston Respublikasining Davlat Madhiyasi | |

| |

| Capital and largest city | Tashkent |

| Official languages | Uzbek |

| Recognised regional languages | Karakalpak |

| Ethnic groups (1996) | Template:Vlist |

| Demonym(s) | Uzbek |

| Government | Presidential republic |

| Islam Karimov | |

| Shavkat Mirziyoyev | |

| Legislature | Supreme Assembly |

| Senate | |

| Legislative Chamber | |

| Independence from the Soviet Union | |

• Formation | 1747b |

| October 27, 1924 | |

• Declared | September 1, 1991 |

• Recognized | December 8, 1991 |

• Completed | December 25, 1991 |

| Area | |

• Total | 447,400 km2 (172,700 sq mi) (56th) |

• Water (%) | 4.9 |

| Population | |

• 2012 estimate | 29,559,100[1] (45th) |

• Density | 61.4/km2 (159.0/sq mi) (136th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2012 estimate |

• Total | $103.212 billion.[2] |

• Per capita | 3,536.[2] |

| GDP (nominal) | 2012 estimate |

• Total | $51.979 billion[2] |

• Per capita | 1,780[2] |

| Gini (2000) | low (95th) |

| HDI (2010) | medium (102nd) |

| Currency | Uzbekistan som (O'zbekiston so'mi) (UZS) |

| Time zone | UTC+5 (UZT) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+5 (not observed) |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +998 |

| ISO 3166 code | UZ |

| Internet TLD | .uz |

| |

Uzbekistan /ʊzˌbɛk[invalid input: 'ɨ']ˈstɑːn/ , officially the Republic of Uzbekistan ([O] Error: {{Lang-xx}}: text has italic markup (help)‘zbekiston Respublikasi, Ўзбекистон Республикаси) is the only doubly landlocked country in Central Asia and one of only two such countries worldwide. It shares borders with Kazakhstan to the west and to the north, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan to the east, and Afghanistan and Turkmenistan to the south. Before 1991, it was part of the Soviet Union.

Once part of the Persian Samanid and later Timurid empires, the region was conquered in the early 16th century by nomads who spoke an Eastern Turkic language. Most of Uzbekistan’s population today belong to the Uzbek ethnic group and speak the Uzbek language, one of the family of Turkic languages. Uzbekistan was incorporated into the Russian Empire in the 19th century, and in 1924 became a constituent republic of the Soviet Union, known as the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic (Uzbek SSR). It became independent on 31 August 1991 (officially, from the following day).

Uzbekistan's economy relies mainly on commodity production, including cotton, gold, uranium, and natural gas. Despite the declared objective of transition to a market economy, Uzbekistan continues to maintain rigid economic controls, which act to deter foreign investment. The policy of gradual, strictly controlled transition to the market economy has nevertheless produced beneficial results in the form of economic recovery after 1995. Uzbekistan's domestic policies on human rights and individual freedoms have been criticised by some international organizations.[4]

Geography

Uzbekistan has an area of 447,400 square kilometres (172,700 sq mi). It is the 56th largest country in the world by area and the 42nd by population.[5] Among the CIS countries, it is the 5th largest by area and the 3rd largest by population.[6]

Uzbekistan lies between latitudes 37° and 46° N, and longitudes 56° and 74° E. It stretches 1,425 kilometres (885 mi) from west to east and 930 kilometres (580 mi) from north to south. Bordering Kazakhstan and the Aral Sea to the north and northwest, Turkmenistan to the southwest, Tajikistan to the southeast, and Kyrgyzstan to the northeast, Uzbekistan is one of the largest Central Asian states and the only Central Asian state to border all the other four. Uzbekistan also shares a short border (less than 150 km or 93 mi) with Afghanistan to the south.

Uzbekistan is a dry, landlocked country. It is one of two doubly landlocked countries in the world — that is, a country completely surrounded by landlocked countries — the other being Liechtenstein. In addition, due to its location within a series of endorheic basins, none of its rivers lead to the sea. Less than 10% of its territory is intensively cultivated irrigated land in river valleys and oases. The rest is vast desert (Kyzyl Kum) and mountains.

The highest point in Uzbekistan is the Khazret Sultan, at 4,643 metres (15,233 ft) above sea level, in the southern part of the Gissar Range in Surkhandarya Province, on the border with Tajikistan, just northwest of Dushanbe (formerly called Peak of the 22nd Congress of the Communist Party).[6]

The climate in the Republic of Uzbekistan is continental, with little precipitation expected annually (100–200 millimeters, or 3.9–7.9 inches). The average summer high temperature tends to be 40 °C (104 °F), while the average winter low temperature is around −23 °C (−9 °F).[7]

Major cities include Andijan, Bukhara, Samarkand, Namangan and the capital Tashkent.

Environment

Decades of questionable Soviet policies in pursuit of greater cotton production have resulted in a catastrophic scenario. The agricultural industry appears to be the main contributor to the pollution and devastation of the air and water in the country.[8]

The Aral Sea disaster is a global, not a local problem. The Aral Sea used to be the fourth-largest inland sea on Earth, acting as an influencing factor in the air moisture and arid land use.[9] Since the 1960s, the decade when the misuse of the Aral Sea water began, it has shrunk to less than 50% of its former area and decreased in volume threefold. Reliable or even approximate data have not been collected, stored or provided by any organization or official agency. Much of the water was and continues to be used for the irrigation of cotton fields, a crop requiring a large amount of water to grow.[10]

The numbers of animal deaths and human refugees flows from the area around the sea can only be guessed. The question of who is responsible for the crisis remains open – the Soviet scientists and politicians who directed the distribution of water during the 1960s, or the post-Soviet politicians who did not allocate sufficient funding for the building of dams and irrigation systems. Nevertheless, it is a big catastrophe.

Due to the virtually unsolvable Aral Sea problem, high salinity and contamination of the soil with heavy elements are especially widespread in Karakalpakstan, the region of Uzbekistan adjacent to the Aral Sea. The bulk of the nation's water resources is used for farming, which accounts for nearly 84% of the water usage and contributes to high soil salinity. Heavy use of pesticides and fertilizers for cotton growing further aggravates soil pollution.[7]

History

The first people known to inhabit the Central Asian region of modern-day Uzbekistan were Iranian nomads who arrived from the northern grasslands of what is now Kazakhstan sometime in the first millennium BC. These nomads, who spoke Iranian dialects, settled in Central Asia and began to build an extensive irrigation system along the rivers of the region. At this time, cities such as Bukhoro (Bukhara), Samarqand (Samarkand) and Chash (Tashkent) began to appear as centers of emerging government and high culture. By the 5th century BC, the Bactrian, Soghdian, and Tokharian states dominated and ruled over the region.

As China began to develop its silk trade with the West, Iranian cities took advantage of this commerce by becoming centres of trade. Using an extensive network of cities and rural settlements in the province of Mouwaurannahr (a name given the region after the Arab conquest) in Uzbekistan, and further east in what is today China's Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, the Soghdian intermediaries became the wealthiest of these Iranian merchants. Because of this trade on what became known as the Silk Route, Bukhoro and Samarqand eventually became extremely wealthy cities, and at the times Mawarannahr was the only large and one of the most influential and powerful Persian provinces of antiquity.[11]

Macedonian ruler Alexander the Great conquered Sogdiana and Bactria in 327 BC, marrying Roxana, daughter of a local Bactrian chieftain. A conquest was supposedly of little help to Alexander as popular resistance was fierce, causing Alexander's army to be bogged down in the region that became the northern part of Hellenistic Greco-Bactrian Kingdom. For many centuries the region of Uzbekistan was ruled by Persian empires, including the Parthian and Sassanid Empires, as well as by other empires, for example formed by the Turkic Hephthalite and Gokturk peoples.

In the 8th century Transoxiana (territory between the Amudarya and Syrdarya rivers) was conquered by Arabs (Ali ibn Sattor), which inherited the region with the Early Renaissance. Many notable scientists have lived and contributed during the Islamic Golden Age. Among the achievements of the scholars during this period were the development of trigonometry into its modern form (simplifying its practical application to calculate the phases of the moon), advances in optics, in astronomy, as well as in poetry, philosophy, art, calligraphy and many other, which have set the foundations for a Muslim Renaissance.

In the 9th – 10th centuries, Transoxiana was included into the Samanid State. Later, Transoxiana saw the incursion of the Turkic-ruled Karakhanids, as well as the Seljuks (Sultan Sanjar) and Kara-Khitans.[12]

The Mongol conquest under Genghis Khan during the 13th century would bring about a change to the region. The conquest and characteristic expansion of the Mongols led to the displacement of some of the Iranian-speaking people of the region, their culture and heritage being superseded by that of the Mongolian-Turkic peoples who came thereafter.

Following the death of Genghis Khan in 1227, his empire was divided among his four sons and his family members. Despite the potential for serious fragmentation, Mongol law of the Mongol Empire maintained orderly succession for several more generations, and control of most of Mawarannahr stayed in the hands of direct descendants of Chagatai Khan, the second son of Genghis Khan. Orderly succession, prosperity, and internal peace prevailed in the Chaghatai lands, and the Mongol Empire as a whole remained strong and united kingdom. (Ulus Batiy, Sattarkhan)[13]

In the early 14th century, however, as the empire began to break up into its constituent parts, the Chaghatai territory also was disrupted as the princes of various tribal groups competed for influence. One tribal chieftain, Timur (Tamerlane),[14] emerged from these struggles in the 1380s as the dominant force in Mawarannahr. Although he was not a descendant of Chinggis, Timur became the de facto ruler of Mawarannahr and proceeded to conquer all of western Central Asia, Iran, Asia Minor, and the southern steppe region north of the Aral Sea. He also invaded Russia, Turkey, Iraq, and placed under his command Iran and India, before dying during an invasion of China in 1405.[13]

Timur initiated the last flowering of Mawarannahr by gathering in his capital, Samarqand, numerous artisans and scholars from the vast lands he had conquered. By supporting such people, Timur imbued his empire with a very rich Perso-Islamic culture. During Amir Timur's reign and the reigns of his immediate descendants, a wide range of religious and palatial construction masterpieces were undertaken in Samarqand and other population centres.[15] Timur also initiated exchange of medical thoughts and patronized physicians, scientists and artists from the neighboring countries like India;[16] his grandson Ulugh Beg was one of the world's first great astronomers. It was during the Timurid dynasty that Turkic, in the form of the Chaghatai dialect, became a literary language in its own right in Mawarannahr, although the Timurids were Persianate in nature. The greatest Chaghataid writer, Ali-Shir Nava'i, was active in the city of Herat, now in northwestern Afghanistan, in the second half of the 15th century.[13]

The Timurid state quickly broke into two halves after the death of Timur. The chronic internal fighting of the Timurids attracted the attention of the Uzbek nomadic tribes living to the north of the Aral Sea. In 1501 the Uzbek forces began a wholesale invasion of Mawarannahr.[13] The slave trade in the Khanate of Bukhara became prominent and was firmly established.[17] Estimates from 1821 suggest that between 25,000 and 60,000 Persian slaves were working only in Bukhara at the time.[18]

In the 19th century, the Russian Empire began to expand and spread into Central Asia. By 1911 Russians living in Uzbekistan numbered 210,306.[19] The "Great Game" period is generally regarded as running from approximately 1813 to the Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907. Following the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, a second, less intensive phase followed. At the start of the 19th century, there were some 3,200 kilometres (2,000 mi) separating British India and the outlying regions of Tsarist Russia. Much of the land in between was unmapped.

By the beginning of 1920, Central Asia was firmly in the hands of Russia and, despite some early resistance to the Bolsheviks, Uzbekistan and the rest of the Central Asia became a part of the Soviet Union. On October 27, 1924 the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic was created. From 1941 to 1945, during World War II, 1,433,230 people from Uzbekistan fought in the Red Army against Nazi Germany. (A number also fought on the German side.) 263,005 Uzbek soldiers died in the battlefields of the Eastern Front, 132,670 went missing in action.[20] On August 31, 1991, Uzbekistan declared independence, proclaiming September 1 as the National Independence Day.

Politics

The first elections of the Oliy Majlis (Parliament) were held under a resolution adopted by the 16th Supreme Soviet in 1994. In that year, the Supreme Soviet was replaced by the Oliy Majlis. Since then Uzbekistan has held presidential and parliamentarian elections on regular basis but no real opposition candidates or parties are able to participate.[citation needed]

The third elections for the bicameral 150-member Oliy Majlis — the Legislative Chamber and the 100-member Senate — for five-year terms, were held on December 27, 2009, after the second elections that were held in December 2004–2005. The Oliy Majlis was unicameral up to 2004. Its strength increased from 69 deputies (members) in 1994 to 120 in 2004–05 and presently to 150.

The executive holds a great deal of power, and the legislature has little power to shape laws. Under terms of a December 27, 1995 referendum, Islam Karimov's first term was extended. Another national referendum was held January 27, 2002 to extend the Constitutional Presidential term from 5 years to 7 years.

The referendum passed, and Islam Karimov's term was extended by an act of parliament to December 2007. Most international observers refused to participate in the process and did not recognize the results, dismissing them as not meeting basic standards. The 2002 referendum also included a plan for a bicameral parliament, consisting of a lower house (the Oliy Majlis) and an upper house (Senate). Members of the lower house are to be "full time" legislators. Elections for the new bicameral parliament took place on December 26. There is currently a political sitation emerging in Uzbekistan around Islam Karimov and the selection of Akbar Abdullaev as successor.[citation needed]

The OSCE limited observation mission concluded that the elections fell significantly short of OSCE commitments and other international standards for democratic elections. Several political parties have been formed with government approval. Similarly, although multiple media outlets (radio, TV, newspaper) have been established, these either remain under government control or rarely broach political topics. Independent political parties were allowed to organise, recruit members and hold conventions and press conferences, but they have been denied registration under restrictive registration procedures.

Human rights

The Constitution of the Republic of Uzbekistan asserts that "democracy in the Republic of Uzbekistan shall be based upon common human principles, according to which the highest value shall be the human being, his life, freedom, honour, dignity and other inalienable rights."

The official position is summarised in a memorandum "The measures taken by the government of the Republic of Uzbekistan in the field of providing and encouraging human rights"[21] and amounts to the following: the government does everything that is in its power to protect and to guarantee the human rights of Uzbekistan's citizens. Uzbekistan continuously improves its laws and institutions in order to create a more humane society. Over 300 laws regulating the rights and basic freedoms of the people have been passed by the parliament. For instance, an office of Ombudsman was established in 1996.[22] On August 2, 2005, President Islam Karimov signed a decree that abolished capital punishment in Uzbekistan on January 1, 2008.

However, non-governmental human rights watchdogs, such as IHF, Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, as well as United States Department of State and Council of the European Union define Uzbekistan as "an authoritarian state with limited civil rights"[23] and express profound concern about "wide-scale violation of virtually all basic human rights".[24] According to the reports, the most widespread violations are torture, arbitrary arrests, and various restrictions of freedoms: of religion, of speech and press, of free association and assembly. It has also been reported that forced sterilization of rural Uzbeki women has been sanctioned by the government.[25] The reports maintain that the violations are most often committed against members of religious organizations, independent journalists, human rights activists and political activists, including members of the banned opposition parties.

The 2005 civil unrest in Uzbekistan, which resulted in several hundred people being killed, is viewed by many as a landmark event in the history of human rights abuse in Uzbekistan.[26][27][28] A concern has been expressed and a request for an independent investigation of the events has been made by the United States, European Union, the UN, the OSCE Chairman-in-Office and the OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights. The government of Uzbekistan is accused of unlawful termination of human life and of denying its citizens freedom of assembly and freedom of expression. The government vehemently rebuffs the accusations, maintaining that it merely conducted an anti-terrorist operation, exercising only necessary force.[29] In addition, some officials claim that "an information war on Uzbekistan has been declared" and the human rights violations in Andijan are invented by the enemies of Uzbekistan as a convenient pretext for intervention in the country's internal affairs.[30]

Uzbekistan also does not allow Tajiks to teach their youth in their native language. There have been cases of destroying Tajiki (Persian-language) literary works.[31]

Provinces and districts

Uzbekistan is divided into twelve provinces (viloyatlar, singular viloyat, compound noun viloyati e.g., Toshkent viloyati, Samarqand viloyati, etc.), one autonomous republic (respublika, compound noun respublikasi e.g. Qaraqalpaqstan Avtonom Respublikasi, Karakalpakistan Autonomous Republic, etc.), and one independent city (shahar. compound noun shahri, e.g., Toshkent shahri). Names are given below in the Uzbek language, although numerous variations of the transliterations of each name exist.

| Division | Capital City | Area (km²) |

Population (2008)[32] | Key |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buxoro Viloyati | Buxoro (Bukhara) | 39,400 | 1,576,800 | 3 |

| Jizzax Viloyati | Jizzax | 20,500 | 1,090,900 | 5 |

| Navoiy Viloyati | Navoiy | 110,800 | 834,100 | 7 |

| Qashqadaryo Viloyati | Qarshi | 28,400 | 2,537,600 | 8 |

| Samarqand Viloyati | Samarqand | 16,400 | 3,032,000 | 9 |

| Sirdaryo Viloyati | Guliston | 5,100 | 698,100 | 10 |

| Surxondaryo Viloyati | Termiz | 20,800 | 2,012,600 | 11 |

| Toshkent Viloyati | Toshkent (Tashkent) | 15,300 | 2,537,500 | 12 |

| Toshkent Shahri | Toshkent (Tashkent) | 335 | 2,192,700 | 1 |

| Fergana Valley Region | ||||

| Farg'ona Viloyati | Farg'ona (Fergana) | 6,800 | 2,997,400 | 4 |

| Andijon Viloyati | Andijon | 4,200 | 2,477,900 | 2 |

| Namangan Viloyati | Namangan | 7,900 | 2,196,200 | 6 |

| Karakalpakstan Region | ||||

| Xorazm Viloyati | Urganch | 6,300 | 1,517,600 | 13 |

| Qaraqalpaqstan Respublikasi | Nukus | 160,000 | 1,612,300 | 14 |

The statistics for Toshkent Viloyati also include the statistics for Toshkent Shahri.

The provinces are further divided into districts (tuman).

Economy

Uzbekistan has the fourth largest gold deposits in the world. The country mines 80 tons of gold annually, seventh in the world. Uzbekistan's copper deposits rank tenth in the world and its uranium deposits twelfth. The country's uranium production ranks seventh globally.[33][34][35] The Uzbek national gas company, Uzbekneftgas, ranks 11th in the world in natural gas production with an annual output of 60 to 70 billion cubic meters. The country has significant untapped reserves of oil and gas: there are 194 deposits of hydrocarbons in Uzbekistan, including 98 condensate and natural gas deposits and 96 gas condensate deposits.

The largest corporations involved in Uzbekistan's energy sector are the China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC), Petronas, the Korea National Oil Corporation, Gazprom, Lukoil, and Uzbekneftgas.

Along with many Commonwealth of Independent States or CIS economies, Uzbekistan's economy declined during the first years of transition and then recovered after 1995, as the cumulative effect of policy reforms began to be felt. It has shown robust growth, rising by 4% per year between 1998 and 2003 and accelerating thereafter to 7%–8% per year. According to IMF estimates,[36] the GDP in 2008 will be almost double its value in 1995 (in constant prices). Since 2003 annual inflation rates averaged less than 10%.

Uzbekistan has a very low GNI per capita (US$610 in current dollars in 2006, giving a PPP equivalent of US$2,250).[37] By GNI per capita in PPP equivalents Uzbekistan ranks 169 among 209 countries; among the 12 CIS countries, only Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan had lower GNI per capita in 2006. Economic production is concentrated in commodities. In 2011, Uzbekistan was the world's seventh-largest producer and fifth-largest exporter of cotton[38] as well as the seventh largest world producer of gold. It is also a regionally significant producer of natural gas, coal, copper, oil, silver and uranium.[39]

Agriculture employs 28% of Uzbekistan's labour force and contributes 24% of its GDP (2006 data).[6] While official unemployment is very low, underemployment – especially in rural areas – is estimated to be at least 20%.[40] Still, at cotton-harvest time, all students and teachers are mobilized as unpaid labour to help in the fields.[41] The use of child labour in Uzbekistan has led several companies, including Tesco,[42] C&A,[43] Marks & Spencer, Gap, and H&M, to boycott Uzbek cotton.[44]

Facing a multitude of economic challenges upon acquiring independence, the government adopted an evolutionary reform strategy, with an emphasis on state control, reduction of imports and self-sufficiency in energy. Since 1994, the state-controlled media have repeatedly proclaimed the success of this "Uzbekistan Economic Model"[45] and suggested that it is a unique example of a smooth transition to the market economy while avoiding shock, pauperism and stagnation.

The gradualist reform strategy has involved postponing significant macroeconomic and structural reforms. The state in the hands of the bureaucracy has remained a dominant influence in the economy. Corruption permeates the society and grows more rampant over time: Uzbekistan's 2005 Corruption Perception Index was 137 out of 159 countries, whereas in 2007 Uzbekistan was 175th out of 179 countries. A February 2006 report on the country by the International Crisis Group suggests that revenues earned from key exports, especially cotton, gold, corn and increasingly gas, are distributed among a very small circle of the ruling elite, with little or no benefit for the populace at large.[46]

According to the Economist Intelligence Unit, "the government is hostile to allowing the development of an independent private sector, over which it would have no control".[47] Thus, the middle class is marginalised economically and, consequently, politically.

The economic policies have repelled foreign investment, which is the lowest per capita in the CIS.[48] For years, the largest barrier to foreign companies entering the Uzbekistan market has been the difficulty of converting currency. In 2003, the government accepted the obligations of Article VIII under the International Monetary Fund (IMF).[49] providing for full currency convertibility. However, strict currency controls and the tightening of borders have lessened the effect of this measure.

Uzbekistan experienced rampant inflation of around 1000% per year immediately after independence (1992–1994). Stabilisation efforts implemented with guidance from the IMF[50] paid off. The inflation rates were brought down to 50% in 1997 and then to 22% in 2002. Since 2003 annual inflation rates averaged less than 10%.[36] Tight economic policies in 2004 resulted in a drastic reduction of inflation to 3.8% (although alternative estimates based on the price of a true market basket, put it at 15%).[51] The inflation rates moved up to 6.9% in 2006 and 7.6% in 2007 but have remained in the single-digit range.[52]

The government of Uzbekistan restricts foreign imports in many ways, including high import duties. Excise taxes are applied in a highly discriminatory manner to protect locally produced goods. Official tariffs are combined with unofficial, discriminatory charges resulting in total charges amounting to as much as 100 to 150% of the actual value of the product, making imported products virtually unaffordable.[53] Import substitution is an officially declared policy and the government proudly reports a reduction by a factor of two in the volume of consumer goods imported. A number of CIS countries are officially exempt from Uzbekistan import duties.

The Republican Stock Exchange (RSE) opened in 1994. The stocks of all Uzbek joint stock companies (around 1250) are traded on RSE. The number of listed companies as of January 2013 exceeds 110. Securities market volume reached 2 trillion in 2012, and the number is rapidly growing due to the rising interest by companies of attracting necessary resources through the capital market. According to Central Depository as of January 2013 par value of outstanding shares of Uzbek emitters exceeded 9 trillion.

Uzbekistan's external position has been strong since 2003. Thanks in part to the recovery of world market prices of gold and cotton (the country's key export commodities), expanded natural gas and some manufacturing exports, and increasing labour migrant transfers, the current account turned into a large surplus (between 9% and 11% of GDP from 2003 to 2005) and foreign exchange reserves, including gold, more than doubled to around US$3 billion.[citation needed]

Foreign exchange reserves amounted in 2010 to 13 billion US$.[54]

Uzbekistan is considered one of the fastest growing economies in the world (top 26) in the next decades according to a global bank HSBC survey [55]

Demographics

Uzbekistan is Central Asia's most populous country. Its 29,559,100 population[1] comprise nearly half the region's total population.

The population of Uzbekistan is very young: 34.1% of its people are younger than 14 (2008 estimate).[40] According to official sources, Uzbeks comprise a majority (80%) of the total population. Other ethnic groups include Russians 5.5%, Tajiks 5% (official estimate and disputed), Kazakhs 3%, Karakalpaks 2.5% and Tatars 1.5% (1996 estimates).[40]

There is some controversy about the percentage of the Tajik population. While official state numbers from Uzbekistan put the number at 5%, the number is said to be an understatement and some Western scholars put the number up to 20%–30%.[56][57][58][59] The Uzbeks absorbed, among others, the Sarts, a Turko-Persian population of Central Asian peasants and merchants. According to recent genetic genealogy testing from a University of Oxford study, the genetic admixture of the Uzbeks clusters somewhere between the Mongols and the Iranian peoples.[60]

Uzbekistan has an ethnic Korean population that was forcibly relocated to the region by Stalin from the Soviet Far East in 1937–1938. There are also small groups of Armenians in Uzbekistan, mostly in Tashkent and Samarkand. The nation is 88% Muslim (mostly Sunni, with a 5% Shi'a minority), 9% Eastern Orthodox and 3% other faiths. The U.S. State Department's International Religious Freedom Report 2004 reports that 0.2% of the population are Buddhist (these being ethnic Koreans). The Bukharan Jews have lived in Central Asia, mostly in Uzbekistan, for thousands of years. There were 94,900 Jews in Uzbekistan in 1989[61] (about 0.5% of the population according to the 1989 census), but now, since the dissolution of the Soviet Union, most Central Asian Jews left the region for the United States, Germany, or Israel. Fewer than 5,000 Jews remained in Uzbekistan in 2007.[62]

During the Soviet period, Russians and Ukrainians constituted more than half the population of Tashkent.[63] The country counted nearly 1.5 million Russians, 12.5% of the population, in the 1970 census.[64] After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, significant emigration of ethnic Russians has taken place, mostly for economic reasons.[65]

In the 1940s, the Crimean Tatars, along with the Germans, Chechens, Greeks, Turks, Kurds and many other nationalities were deported to Central Asia.[66] Approximately 100,000 Crimean Tatars continue to live in Uzbekistan.[67] The number of Greeks in Tashkent has decreased from 35,000 in 1974 to about 12,000 today.[68] The majority of Meskhetian Turks left the country after the pogroms in the Fergana valley in June 1989.[69]

At least 10% of Uzbekistan's labour force works abroad (mostly in Russia and Kazakhstan).[70]

Uzbekistan has a 99.3% literacy rate among adults older than 15 (2003 estimate),[40] which is attributable to the free and universal education system of the Soviet Union.

Largest cities

Template:Largest cities of Uzbekistan

Religion

Islam is by far the dominant religion in Uzbekistan, as Muslims constitute 90% of the population while 5% of the population follow Russian Orthodox Christianity, and 5% of the population follow other religion according to a 2009 US State Department release.[71] However, a 2009 Pew Research Center report stated that Uzbekistan's population is 96.3% Muslim.[72] An estimated 93,000 Jews were once present in the country.[citation needed]

Despite its predominance, the practice of Islam is far from monolithic. Many versions of the faith have been practiced in Uzbekistan. The conflict of Islamic tradition with various agendas of reform or secularization throughout the 20th century has left the outside world with a confused notion of Islamic practices in Central Asia.[citation needed]

The end of Soviet power in Uzbekistan did not bring an upsurge of fundamentalism, as many had predicted, but rather a gradual reacquaintance with the precepts of the faith. However after 2000, there seems to be a rise of support in favor of the Islamists.[citation needed]

Although constitutionally maintaining rights to freedom of religion, Uzbekistan maintains a ban on all religious activities not approved by that state, with particularly harsh treatment of Protestant Christians being commonplace. See: Human Rights; Freedom of Religion, Uzbekistan

Languages

The Uzbek language is the only official state language,[73] and since 1992 is officially written in the Latin alphabet. The Tajik language is widespread in the cities of Bukhara and Samarkand because of their relatively large population of ethnic Tajiks.[57] It is also found in large pockets in Kasan, Namangan, Khokand and Kanibadam in Fergana valley, as well as in Ahangaran, Baghistan in the middle Syr Darya distrist, and finally in, Shahri Sabz, Kitab and the river valleys of Kafiringan and Chaganian rivers, forming altogether, approximately 25-30% of the population of Uzbekistan

Russian is an important language for interethnic communication, especially in the cities, including much day-to-day technical, scientific, governmental and business use. Russian is the main language of over 14% of the population and is spoken as a second language by many more. The use of Russian in remote rural areas has always been limited, and today most school children have no proficiency in Russian even in urban centres. However, it was reported in 2003 that over half of the population could speak and understand Russian, and a renewed close political relationship between Russia and Uzbekistan has meant that official discouragement of Russian has dropped off sharply.[74]

Before 1920s, the written language of Uzbeks was called Turki (known to Western scholars as Chagatay) and used the Nastaʿlīq script. In 1926, the Latin alphabet was introduced and went through several revisions in throughout the 1930s. Finally, in 1940, Cyrillic alphabet was abruptly introduced by Soviet authorities and was used until the fall of Soviet Union. In 1993, Uzbekistan shifted back to the Latin script, which was modified in 1996 and is being taught in schools since 2005.[75] Nevertheless, many signs and notices (including official government boards in the streets) are still written in Uzbek Cyrillic script[citation needed].

Communications

According to the official source report, as of March 10, 2008, the number of cellular phone users in Uzbekistan reached 7 million, up from 3.7 million on July 1, 2007.[76] The largest mobile operator in terms of number of subscribers is MTS-Uzbekistan (former Uzdunrobita and part of Russian Mobile TeleSystems) and it is followed by Beeline (part of Russia's Beeline) and UCell (ex Coscom) (originally part of the U.S. MCT Corp., now a subsidiary of the Nordic/Baltic telecommunication company TeliaSonera AB).[77]

As of July 1, 2007, the estimated number of internet users was 1.8 million, according to UzACI.

Transportation

Tashkent, the nation's capital and largest city, has a three-line rapid transit system built in 1977, and expanded in 2001 after ten years' independence from the Soviet Union. Uzbekistan is currently the only country in Central Asia with a subway system, which is promoted as one of the cleanest systems in the former Soviet Union.[78] The stations are exceedingly ornate. For example, the station Metro Kosmonavtov built in 1984 is decorated using a space travel theme to recognise the achievements of mankind in space exploration and to commemorate the role of Vladimir Dzhanibekov, the Soviet cosmonaut of Uzbek origin. A statue of Vladimir Dzhanibekov stands near one of the station's entrances.

There are government-operated trams and buses running across the city. There are also many taxis, both registered and unregistered. Uzbekistan has car-producing plants which produce modern cars. The car production is supported by the government and the Korean auto company Daewoo. The Uzbek government acquired a 50% stake in Daewoo in 2005[citation needed] for an undisclosed sum, and in May 2007 UzDaewooAuto, the car maker, signed a strategic agreement with General Motors-Daewoo Auto and Technology (GMDAT, see: GM Uzbekistan also).[79] The government also bought a stake in Turkey's Koc in SamKochAvto, a producer of small buses and lorries. Afterwards, it signed an agreement with Isuzu Motors of Japan to produce Isuzu buses and lorries.[80]

Train links connect many towns within Uzbekistan, as well as neighboring former republics of the Soviet Union. Moreover, after independence two fast-running train systems were established. Uzbekistan has launched first high-speed railway in Central Asia in September 2011 between Tashkent and Samarqand. The new high-speed electric train Talgo 250, called Afrosiyob, was manufactured by Patentes Talgo S.L. (Spain) and carried out its first trip from Tashkent to Samarkand on August 26, 2011.[81]

There is also a large airplane plant that was built during the Soviet era – Tashkent Chkalov Aviation Manufacturing Plant or ТАПОиЧ in Russian. The plant originated during World War II, when production facilities were evacuated south and east to avoid capture by advancing Nazi forces. Until the late 1980s, the plant was one of the leading airplane production centers in the USSR, but with dissolution of the Soviet Union its manufacturing equipment became outdated, and most of the workers were laid off. Now it produces only a few planes a year, but with interest from Russian companies growing in it, there are rumours of production-enhancement plans.

Military

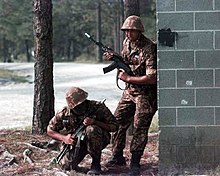

With close to 65,000 servicemen, Uzbekistan possesses the largest armed forces in Central Asia. The military structure is largely inherited from the Turkestan Military District of the Soviet Army, although it is going through a reform to be based mainly on motorized infantry with some light and special forces[citation needed]. The Uzbek Armed Forces' equipment is not modern, and training, while improving, is neither uniform nor adequate for its new mission of territorial security[citation needed].

The government has accepted the arms control obligations of the former Soviet Union, acceded to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (as a non-nuclear state), and supported an active program by the U.S. Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA) in western Uzbekistan (Nukus and Vozrozhdeniye Island). The Government of Uzbekistan spends about 3.7% of GDP on the military but has received a growing infusion of Foreign Military Financing (FMF) and other security assistance funds since 1998.

Following the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks in the U.S., Uzbekistan approved the U.S. Central Command's request for access to an air base, the Karshi-Khanabad airfield, in southern Uzbekistan. However, Uzbekistan demanded that the U.S. withdraw from the airbases after the Andijan massacre and the U.S. reaction to this massacre. The last US troops left Uzbekistan in November 2005.

On 23 June 2006, Uzbekistan became a full participant in the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), but informed the CSTO to suspend its membership in June 2012.[82]

Foreign relations

Uzbekistan joined the Commonwealth of Independent States in December 1991. However, it is opposed to reintegration and withdrew from the CIS collective security arrangement in 1999. Since that time, Uzbekistan has participated in the CIS peacekeeping force in Tajikistan and in UN-organized groups to help resolve the Tajikistan and Afghanistan conflicts, both of which it sees as posing threats to its own stability.

Previously close to Washington (which gave Uzbekistan half a billion dollars in aid in 2004, about a quarter of its military budget), the government of Uzbekistan has recently restricted American military use of the airbase at Karshi-Khanabad for air operations in neighboring Afghanistan.[83] Uzbekistan was an active supporter of U.S. efforts against worldwide terrorism and joined the coalitions that have dealt with both Afghanistan and Iraq.

The relationship between Uzbekistan and the United States began to deteriorate after the so-called "colour revolutions" in Georgia and Ukraine (and to a lesser extent Kyrgyzstan). When the U.S. joined in a call for an independent international investigation of the bloody events at Andijan, the relationship further declined, and President Islam Karimov changed the political alignment of the country to bring it closer to Russia and China, countries which chose not to criticise Uzbekistan's leaders for their alleged human rights violations.

In late July 2005, the government of Uzbekistan ordered the United States to vacate an air base in Karshi-Kanabad (near Uzbekistan's border with Afghanistan) within 180 days. Karimov had offered use of the base to the U.S. shortly after 9/11. It is also believed by some Uzbeks that the protests in Andijan were brought about by the U.K. and U.S. influences in the area of Andijan. This is another reason for the hostility between Uzbekistan and the West.

Uzbekistan is a member of the United Nations (UN) (since March 2, 1992), the Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council (EAPC), Partnership for Peace (PfP), and the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE). It belongs to the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) and the Economic Cooperation Organisation (ECO) (comprising the five Central Asian countries, Azerbaijan, Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan, and Pakistan). In 1999, Uzbekistan joined the GUAM alliance (Georgia, Ukraine, Azerbaijan and Moldova), which was formed in 1997 (making it GUUAM), but pulled out of the organization in 2005.

Uzbekistan is also a member of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) and hosts the SCO’s Regional Anti-Terrorist Structure (RATS) in Tashkent. Uzbekistan joined the new Central Asian Cooperation Organisation (CACO) in 2002. The CACO consists of Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. It is a founding member of, and remains involved in, the Central Asian Union, formed with Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, and joined in March 1998 by Tajikistan.

In September 2006, UNESCO presented Islam Karimov an award for Uzbekistan's preservation of its rich culture and traditions. Despite criticism, this seems to be a sign of improving relationships between Uzbekistan and the West.

The month of October 2006 also saw a decrease in the isolation of Uzbekistan from the West. The EU announced that it was planning to send a delegation to Uzbekistan to talk about human rights and liberties, after a long period of hostile relations between the two. Although it is equivocal about whether the official or unofficial version of the Andijan Massacre is true, the EU is evidently willing to ease its economic sanctions against Uzbekistan. Nevertheless, it is generally assumed among Uzbekistan's population that the government will stand firm in maintaining its close ties with the Russian Federation and in its theory that the 2004–2005 protests in Uzbekistan were promoted by the USA and UK.

Culture

Uzbekistan has a wide mix of ethnic groups and cultures, with the Uzbek being the majority group. In 1995 about 71% of Uzbekistan's population was Uzbek. The chief minority groups were Russians (8%), Tajiks (5–30%),[56][57][58][84] Kazaks (4%), Tatars (2.5%) and Karakalpaks (2%). It is said, however, that the number of non-Uzbek people living in Uzbekistan is decreasing as Russians and other minority groups slowly leave and Uzbeks return from other parts of the former Soviet Union.

When Uzbekistan gained independence in 1991, there was concern that Muslim fundamentalism would spread across the region. The expectation was that a country long denied freedom of religious practice would undergo a very rapid increase in the expression of its dominant faith. As of 1994, over half of Uzbekistan's population was said to be Muslim, though in an official survey few of that number had any real knowledge of the religion or knew how to practice it. However, Islamic observance is increasing in the region.

Uzbekistan has a high literacy rate, with about 99.3% of adults above the age of 15 being able to read and write. However with only 76% of the under-15 population currently enrolled in education (and only 20% of the 3-6 year olds attending pre-school), this figure may drop in the future. Students attend school Monday through Saturday during the school year,with official education concluding at the end of the 9th grade. Post secondary school, students routinely attend trade or technical colleges. There are two international schools operating in Uzbekistan, both in Tashkent: The British School catering for elementary students only, and Tashkent International School, a K-12 international curriculum school.

Uzbekistan has encountered severe budget shortfalls in its education program. The education law of 1992 began the process of theoretical reform, but the physical base has deteriorated and curriculum revision has been slow. A large contributor to this decline is the low level of wages received by teachers and the lack of spending on infrastructure, buildings and resources on behalf of the government. Corruption within the education system is also rampant, with students from wealthier families routinely bribing teachers and school executives to achieve high grades without attending school, or undertaking official examinations.[85]

Uzbekistan's universities create almost 600,000 graduates annually, though the general standard of university graduates, and the overall level of education within the tertiary system is low. Westminster University maintains a campus in Tashkent offering English language courses across several disciplines.

Music

Central Asian classical music is called Shashmaqam, which arose in Bukhara in the late 16th century when that city was a regional capital. Shashmaqam is closely related to Azerbaijani Mugam and Uyghur muqam. The name, which translates as six maqams refers to the structure of the music, which contains six sections in six different Musical modes, similar to classical Persian traditional music. Interludes of spoken Sufi poetry interrupt the music, typically beginning at a lower register and gradually ascending to a climax before calming back down to the beginning tone.

Endurance of listening and continual audiences that attend events, such as Bazms or Weddings, is what makes the Folk-pop style of music so popular. The classical music in Uzbekistan is very different than that of the pop music. Mostly men listen to Solo or Duo shows during a morning or evening meeting amongst men. Shash maqam, which is the main component of the classical genre of music. The large support of the musicians from high class families, which meant the Patronage was to be paid to the Shash maqam above all things. Poetry is where some of the music is drawn from. In some instances of the music, the 2 languages are even mixed in the same song. In the 1950s, the folk music became less popular, and the genre was barred from the radio stations. They did not completely dispel the music all together, although the name changed to Feudal music. Although banned, the folk musical groups continued to play their music in their own ways and spread it individually as well. Many say that it was the most liberated musical experience in their lives.[citation needed]

Education

Uzbekistan has a high literacy rate with about 99% of adults above the age of 15 being able to read and write. Uzbekistan has encountered severe budgeting shortfalls in its education program. The education law of 1992 began the process of theoretical reform, but the physical base has deteriorated and curriculum revision has been slow.

Holidays

- January 1 – New Year "Yangi Yil Bayrami"

- January 14 – Vatan Himoyachilari kuni

- March 8 – International Women's Day – "Xalqaro Xotin-Qizlar kuni"

- March 21 – Navrooz – "Navro'z Bayrami"

- May 9 – Remembrance Day – "Xotira va Qadirlash kuni"

- September 1 – Independence Day – "Mustaqillik kuni"

- October 1 – Teacher's Day – "O'qituvchi va Murabbiylar"

- December 8 – "Constitution Day" – Konstitutsiya kuni

Variable date

- End of Ramazon Ramazon Hayit Eid al-Fitr

- 70 days later Qurbon Hayit Eid al-Adha

Cuisine

Uzbek Cuisine is influenced by local agriculture, as in most nations. There is a great deal of grain farming in Uzbekistan, so breads and noodles are of importance and Uzbek cuisine has been characterized as noodle rich. Mutton is a popular variety of meat due to the abundance of sheep in the country and it is part of various Uzbek dishes.

Uzbekistan's signature dish is Palov (Plov or Osh), a main course typically made with rice, pieces of meat, and grated carrots and onions. Oshi Nahor, or morning Plov, is served in the early morning (between 6 am and 9 am) to large gatherings of guests, typically as part of an ongoing wedding celebration. Other notable national dishes include: Shurpa (Shurva or Shorva), a soup made of large pieces of fatty meat (usually mutton), and fresh vegetables; Norin and Langman, noodle-based dishes that may be served as a soup or a main course; Manti, Chuchvara, and Somsa, stuffed pockets of dough served as an appetizer or a main course; Dimlama (a meat and vegetable stew) and various Kebabs, usually served as a main course.

Green tea is the national hot beverage taken throughout the day; teahouses (Chaikhanas) are of cultural importance. The more usual black tea is preferred in Tashkent, both green and black teas are taken daily without milk or sugar. Tea always accompanies a meal, but it is also a drink of hospitality, automatically offered – green or black – to every guest. Ayran, a chilled yogurt drink, is popular in summer, but does not replace hot tea.

The use of alcohol is less widespread than in the west, but wine is comparatively popular for a Muslim nation as Uzbekistan is largely secular. Uzbekistan has 14 wineries, the oldest and most famous being the Khovrenko Winery in Samarkand (est. 1927). The Samarkand Winery produces a range of dessert wines from local grape varieties: Gulyakandoz, Shirin, Aleatiko, and Kabernet likernoe (literally Cabernet dessert wine in Russian). Uzbek wines have received international awards and are exported to Russia and other countries.

Sport

Uzbekistan is home to former racing cyclist Djamolidine Abdoujaparov. Abdoujaparov has won the points contest in the Tour de France three times, each time winning the coveted green jersey (the green jersey is second only to the yellow jersey).[86] Abdoujaparov was a specialist at winning stages in tours or one-day races when the bunch or peloton would finish together. He would often 'sprint' in the final kilometre and had a reputation as being dangerous in these bunch sprints as he would weave from side to side. This reputation earned him the nickname 'The Terror of Tashkent'.

Artur Taymazov won Uzbekistan's first wrestling medal at the 2000 Summer Olympic Games, as well as three gold medals at the 2004, 2008 Summer Olympic Games and 2012 Summer Olympic Games in Men's 120 kg.

Ruslan Chagaev is a professional boxer representing Uzbekistan in the WBA. He won the WBA champion title in 2007 after defeating Nikolai Valuev. Chagaev defended his title twice before losing it to Vladimir Klitschko in 2009.

Michael Kolganov, sprint canoer, was world champion and won an Olympic bronze in K-1 500-meter. Gymnast Alexander Shatilov won a world bronze as an artistic gymnast in floor exercise.

Uzbekistan is the home of the International Kurash Association. Kurash is an internationalized and modernized form of the traditional Uzbek fighting art of Kurash.

Football is the most popular sport in Uzbekistan. Uzbekistan's premier football league is the Uzbek League, which features 14 teams since 2010, before 16. The current champions (2011) are FC Bunyodkor, and the team with the most championships is FC Pakhtakor Tashkent with 8. The current Player of the Year (2011) is Odil Ahmedov. Uzbekistan's football clubs regularly participates in the AFC Champions League and the AFC Cup. Nasaf won AFC Cup in 2011, which is the first international club cup for Uzbek football.

Before Uzbekistan's independence in 1991, the country used to be part of the Soviet Union football, rugby union, ice hockey, basketball, and handball national teams. After Uzbekistan got split up from the Soviet Union, Uzbekistan created its own football, rugby union, and futsal national teams.

Tennis is also a very popular sport in Uzbekistan, especially after Uzbekistan's independence in 1991. Uzbekistan also has its own Tennis Federation called the "UTF" (Uzbekistan Tennis Federation) that was created in 2002. Uzbekistan also hosts an International WTA tennis tournament called the "Tashkent Open", which is held in Uzbekistan's capital city. This tournament has been held since 1999, and is played on outdoor hard courts. The most notable active players from Uzbekistan are Denis Istomin and Akgul Amanmuradova.

Other popular sports in Uzbekistan include judo, team handball, baseball, taekwondo, basketball, and futsal.

-

Djamolidine Abdoujaparov is the most famous cyclist in Uzbekistan, winning three Tour de France point contests. Abdoujaparov was one of the world's fastest cyclists.

-

Sergey Lagutin at the 2008 Eneco Tour

-

Denis Istomin at the 2009 US Open

See also

References

- ^ a b Official population estimation 2012-01-01. Stat.uz (2012-01-23). Retrieved on 2012-03-13.

- ^ a b c d МВФ — World Economic Outlook Database, April 2012 — Uzbekistan. Gross domestic product…

- ^ "Human Development Report 2010" (PDF). United Nations. 2010. Retrieved November 5, 2010.

- ^ Human rights in Uzbekistan: Amnesty International report, 2008.

- ^ "www.worldatlas.com". www.worldatlas.com. Retrieved May 2, 2010.

- ^ a b c Uzbekistan will publish its own book of records – Ferghana.ru. 18 July 2007. Retrieved July 29, 2009.

- ^ a b Climate, Uzbekistan : Country Studies – Federal Research Division, Library of Congress.

- ^ "Uzbekistan – Environment". Countrystudies.us. Retrieved May 2, 2010.

- ^ "Uzbekistan: Environmental disaster on a colossal scale". Msf.org. November 1, 2000. Archived from the original on 2007-09-30. Retrieved May 2, 2010.

- ^ Aral Sea Crisis Environmental Justice Foundation Report

- ^ Lubin, Nancy. "Early history". In Curtis.

- ^ Davidovich, E. A. (1998). "Chapter 6 The Karakhanids". In C.E. Bosworth (ed.). History of Civilisations of Central Asia. Vol. 4 part I. UNESCO Publishing. pp. 119–144. ISBN 92-3-103467-7.

{{cite book}}: More than one of|contribution=and|chapter=specified (help) - ^ a b c d Lubin, Nancy. "Rule of Timur". In Curtis.

- ^ Martin Sicker [1] (2000). Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 154. ISBN 0-275-96892-8

- ^ Forbes, Andrew, & Henley, David: Timur's Legacy: The Architecture of Bukhara and Samarkand (CPA Media).

- ^ Medical Links between India & Uzbekistan in Medieval Times by Hakim Syed Zillur Rahman, Historical and Cultural Links between India & Uzbekistan, Khuda Bakhsh Oriental Library, Patna, 1996. pp. 353–381.

- ^ "Adventure in the East". TIME. April 6, 1959. Retrieved January 28, 2011.

- ^ Scott Cameron Levi The Indian diaspora in Central Asia and its trade, 1550–1900(2002). p. 68. ISBN 90-04-12320-2.

- ^ Vladimir Shlapentokh, Munir Sendich, Emil Payin The new Russian diaspora: Russian minorities in the former Soviet republics(1994). p. 108. ISBN 1-56324-335-0.

- ^ Chahryar Adle, Madhavan K.. Palat, Anara Tabyshalieva (2005). "Towards the Contemporary Period: From the Mid-nineteenth to the End of the Twentieth Century". UNESCO. p.232. ISBN 9231039857

- ^ Embassy of Uzbekistan to the US, Press-Release: "The measures taken by the government of the Republic of Uzbekistan in the field of providing and encouraging human rights", October 24, 2005

- ^ Uzbekistan Daily Digest, "Uzbekistan's Ombudsman reports on 2002 results", December 25, 2007

- ^ US Department of State, 2008 Country Report on Human Rights Practices in Uzbekistan, Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labour, February 25, 2009

- ^ IHF, Human Rights in OSCE Region: Europe, Central Asia and North America – Uzbekistan, Report 2004 (events of 2003), 2004-06-23

- ^ OMCT and Legal Aid Society, Denial of justice in Uzbekistan – an assessment of the human rights situation and national system of protection of fundamental rights, April 2005.

- ^ Jeffrey Thomas, US Government Info September 26, 2005 Freedom of Assembly, Association Needed in Eurasia, U.S. Says,

- ^ McMahon, Robert (June 7, 2005). "Uzbekistan: Report Cites Evidence Of Government 'Massacre' In Andijon – Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty". Rferl.org. Retrieved May 2, 2010.

- ^ "Uzbekistan: Independent international investigation needed into Andizhan events | Amnesty International". Web.amnesty.org. June 23, 2005. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007. Retrieved May 2, 2010.

- ^ "Press-service of the President of the Republic of Uzbekistan:". Press-service.uz. May 17, 2005. Archived from the original on 2008-03-08. Retrieved May 2, 2010.

- ^ Акмаль Саидов (27 October 2005). "Андижанские события стали поводом для беспрецедентного давления на Узбекистан". Kreml.Org. Retrieved May 2, 2010.

- ^ "MAR (Minorities at Risk) report ''(retrieved February 21, 2010)''". Cidcm.umd.edu. December 31, 2006. Retrieved May 2, 2010.

- ^ "Statistical Review of Uzbekistan 2008, p.176" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-11-13. Retrieved May 2, 2010.

- ^ World Nuclear Association

- ^ European Nuclear Society

- ^ British Geological Survey

- ^ a b IMF World Economic Outlook Database, October 2007

- ^ GNI per capita 2006, Atlas method and PPP, World Development Indicators database, World Bank, September 14, 2007.

- ^ "The National Cotton Council of America: Rankings". 2011. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- ^ "Country Profile: Uzbekistan". Irinnews.org. Archived from the original on 2010-08-27. Retrieved May 2, 2010.

- ^ a b c d Cite error: The named reference

cia1was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Programmes | Newsnight | Child labour and the High Street". BBC News. October 30, 2007. Retrieved May 2, 2010.

- ^ "Tesco Ethical Assessment Programme" (PDF). Retrieved May 2, 2010.

- ^ C&A. "C&A Code of Conduct for Uzbekistan". C-and-a.com. Retrieved May 2, 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Saidazimova, Gulnoza (June 12, 2008). "Central Asia: Child Labor Alive And Thriving". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Archived from the original on 2011-07-27. Retrieved July 8, 2008.

- ^ Islam Karimov's interview to Rossijskaya Gazeta, 1995-07-07 Principles of Our Reform (in Russian).

- ^ Gary Thomas New Report Paints Grim Picture of Uzbekistan. Voice of America. 16 February 2006

- ^ "Uzbekistan: Economic Overview". eurasiacenter.org. Archived from the original on 2011-05-11. Retrieved May 2, 2010.

- ^ 2011 Investment Climate Statement – Uzbekistan. US Department of State, March 2011

- ^ "Press Release: The Republic of Uzbekistan Accepts Article VIII Obligations". Imf.org. Retrieved May 2, 2010.

- ^ Uzbekistan's Ministry of Foreign Affairs on IMF's role in economic stabilisation. Retrieved on June 22, 2009

- ^ "Asian Development Outlook 2005 – Uzbekistan". ADB.org. January 1, 2005. Retrieved May 2, 2010.

- ^ "Uzbekistan CPI 2003–2007". Indexmundi.com. February 19, 2010. Retrieved May 2, 2010.

- ^ Uzbekistan. NTE 2004 FINAL 3.30.04

- ^ "Uzbekistan" (in Russian). The world bank.

- ^ "the World in 2050" (PDF). HSBC.

- ^ a b Cornell, Svante E. (2000). "Uzbekistan: A Regional Player in Eurasian Geopolitics?". European Security. 9 (2): 115. doi:10.1080/09662830008407454. Archived from the original on 2009-05-05.

- ^ a b c Richard Foltz (1996). "The Tajiks of Uzbekistan". Central Asian Survey. 15 (2): 213–216. doi:10.1080/02634939608400946.

- ^ a b Karl Cordell, "Ethnicity and Democratisation in the New Europe", Routledge, 1998. p. 201: "Consequently, the number of citizens who regard themselves as Tajiks is difficult to determine. Tajikis within and outside of the republic, Samarkand State University (SamGU) academic and international commentators suggest that there may be between six and seven million Tajiks in Uzbekistan, constituting 30% of the republic's 22 million population, rather than the official figure of 4.7%(Foltz 1996;213; Carlisle 1995:88).

- ^ Lena Jonson (1976) "Tajikistan in the New Central Asia", I.B.Tauris, p. 108: "According to official Uzbek statistics there are slightly over 1 million Tajiks in Uzbekistan or about 3% of the population. The unofficial figure is over 6 million Tajiks. They are concentrated in the Sukhandarya, Samarqand and Bukhara regions."

- ^ Tatjana Zerjal; Wells, R. Spencer; Yuldasheva, Nadira; Ruzibakiev, Ruslan; Tyler-Smith, Chris (2002). "A Genetic Landscape Reshaped by Recent Events: Y-Chromosomal Insights into Central Asia". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 71 (3): 466–482. doi:10.1086/342096. PMC 419996. PMID 12145751.

- ^ World Jewish Population 2001, American Jewish Yearbook, vol. 101 (2001), p. 561.

- ^ World Jewish Population 2007, American Jewish Yearbook, vol. 107 (2007), p. 592.

- ^ Edward Allworth Central Asia, 130 years of Russian dominance: a historical overview (1994). Duke University Press. p.102. ISBN 0-8223-1521-1

- ^ "The Russian Minority in Central Asia: Migration, Politics, and Language" (PDF). Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars.

- ^ The Russians are Still Leaving Uzbekistan For Kazakhstan Now. Journal of Turkish Weekly. December 16, 2004.

- ^ Deported Nationalities. World Directory of Minorities.

- ^ Crimean Tatars Divide Ukraine and Russia. The Jamestown Foundation. June 24, 2009.

- ^ Greece overcomes its ancient history, finally. The Independent. July 6, 2004.

- ^ World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples – Uzbekistan : Meskhetian Turks. Minority Rights Group International.

- ^ International Crisis Group, Uzbekistan: Stagnation and Uncertainty, Asia Briefing N°67, August 22, 2007

- ^ "Uzbekistan". State.gov. August 19, 2010. Retrieved January 28, 2011.

- ^ Mapping the Global Muslim Population. A Report on the Size and Distribution of the World’s Muslim Population. Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life (October 2009)

- ^ Nasim Mansurov (December 8, 1992). "Constitution of the Republic of Uzbekistan". Umid.uz. Retrieved May 2, 2010.

- ^ "Uzbekistan's Russian-Language Conundrum". Eurasianet.org. September 19, 2006. Retrieved May 2, 2010.

- ^ Kamp, Marianne (2008). The New Woman in Uzbekistan: Islam, Modernity, and Unveiling Under Communism. University of Washington Press. ISBN 0-295-98819-3.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Uzbekistan agency for Communication and Information (UzACI) [2] and UzDaily.com [3]

- ^ TeleSonera AB acquires Coscom, UzDaily.com, July 17, 2007. Retrieved on January 18, 2009.

- ^ Tashkent Subway for Quick Travel to Hotels, Resorts, and Around the City!

- ^ "Uzbekistan, General Motors sign strategic deal". Uzdaily.com. Retrieved May 2, 2010.

- ^ SamAuto supplies 100 buses to Samarkand firms, UZDaily.com. Japanese firm buys 8% shares in SamAuto, UZDaily.com.

- ^ First high-speed electricity train carries out first trip from Samarkand and Tashkent, 27 August 2011. Uzdaily (2011-08-27). Retrieved on 2012-02-19.

- ^ "Uzbekistan quits Russia-led CSTO military bloc". June 28, 2012.

- ^ Erich Marquardt and Adam Wolfe Rice Attempts to Secure US Influence in Central Asia, Global Policy Forum. October 17, 2005

- ^ Lena Jonson, "Tajikistan in the New Central Asia", Published by I.B.Tauris, 2006. p. 108: "According to official Uzbek statistics there are slightly over 1 million Tajiks in Uzbekistan or about 4% of the population. The unofficial figure is over 6 million Tajiks. They are concentrated in the Sukhandarya, Samarqand and Bukhara regions."

- ^ Uzbekistan: Lessons in Graft | Chalkboard

- ^ "Le Tours archive". Retrieved 2011-08-23.

Sources

- Environmental Justice Foundation, February 2010, Slave Nation – A report exposing the continued use of state-sponsored forced child labour in the cotton fields of Uzbekistan,

- Anora Mahmudova, AlterNet, May 27, 2005, Uzbekistan’s Growing Police State (checked 2005-11-08)

- Manfred Nowak, Radio Free Europe, 2005-06-23, UN Charges Uzbekistan With Post-Andijon Torture,

- Gulnoza Saidazimova, Radio Free Europe, 2005-06-22, Uzbekistan: Tashkent reveals findings on Andijon uprising as victims mourned

- BBC News, 'Harassed' BBC shuts Uzbek office, 2005-10-26 (checked 2005-11-15)

- UNDP/CER/CCI's Public-Private Partnership in Uzbekistan: Problems, Opportunities and Ways of Introduction

- UNDP & Chamber of Commerce and Industry “Export Guide for Uzbekistan”

- IMF, 2005-09-24 Republic of Uzbekistan and the IMF

Printed sources

- Chasing the Sea: Lost Among the Ghosts of Empire in Central Asia by Tom Bissell

- A Historical Atlas of Uzbekistan by Aisha Khan

- The Modern Uzbeks From the 14th century to the Present: A Cultural History by Edward A. Allworth

- Nationalism in Uzbekistan: Soviet Republic's Road to Sovereignty by James Critchlow

- Odyssey Guide: Uzbekistan by Calcum Macleod and Bradley Mayhew

- Uzbekistan: Heirs to the Silk Road by Johannes Kalter and Margareta Pavaloi

- Silk Road to Ruin: Is Central Asia the New Middle East? by Ted Rall

- Murder in Samarkand: A British Ambassador's Controversial Defiance of Tyranny in the War on Terror by Craig Murray

- Tamerlane's Children: Dispatches from contemporary Uzbekistan by Robert Rand

- White Gold: the true cost of cotton, Still in the Fields, and Slave Nation. Printed reports documenting environmental and social abuses in Uzbekistan's cotton fields by the Environmental Justice Foundation

External links

- National Information Agency of Uzbekistan

- Tashkent directory

- Lower House of Uzbekistan parliament

- Chief of State and Cabinet Members

- General information

- "Uzbekistan". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency.

- Uzbekistan from the U.S. Library of Congress includes Background Notes, Country Study and major reports

- Uzbek Publishing and National Bibliography from the University of Illinois Slavic and East European Library

- Uzbekistan at UCB Libraries GovPubs

- List of cities and populations

- Uzbekistan at Curlie

- Uzbekistan profile from the BBC News

Wikimedia Atlas of Uzbekistan

Wikimedia Atlas of Uzbekistan- Key Development Forecasts for Uzbekistan from International Futures

- Ill-formatted IPAc-en transclusions

- Uzbekistan

- Central Asian countries

- Landlocked countries

- Member states of the Commonwealth of Independent States

- Member states of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation

- Member states of the United Nations

- Modern Turkic states

- Persian-speaking countries and territories

- Russian-speaking countries and territories

- States and territories established in 1991