Indian rupee

| रुपया Template:Hi icon | |

|---|---|

| |

| ISO 4217 | |

| Code | INR (numeric: 356) |

| Subunit | 0.01 |

| Unit | |

| Symbol | ₹ |

| Nickname | Taaka(৳), Rupayya, Rūbāi |

| Denominations | |

| Subunit | |

| 1/100 | Paisa |

| Symbol | |

| Paisa | p |

| Formerly used symbols and Coins | ₨, Rs, ৳, ૱, రూ, ௹, रु . |

| Banknotes | ₹5, ₹10, ₹20, ₹50, ₹100, ₹500, ₹1000 |

| Coins | 50 paise, ₹1, ₹2, ₹5, ₹10 |

| Demographics | |

| Official user(s) | |

| Unofficial user(s) | |

| Issuance | |

| Central bank | Reserve Bank of India |

| Website | www.rbi.org.in |

| Printer | Reserve Bank of India |

| Website | www.rbi.org.in |

| Mint | India Government Mint |

| Website | www.spmcil.com |

| Valuation | |

| Inflation | 5.96%, March 2013 |

| Source | Economic Adviser |

| Method | WPI |

| Pegged by | Bhutanese ngultrum (at par) Nepalese rupee (1 INR = 1.6 NPR) |

The error: {{nihongo}}: Japanese or romaji text required (help) is the official currency of the Republic of India. The issuance of the currency is controlled by the Reserve Bank of India.[1]

The modern rupee is subdivided into 100 paise (singular paisa), though as of 2011 only 50-paise coins are legal tender.[2][3] Banknotes in circulation come in denominations of ₹5, ₹10, ₹20, ₹50, ₹100, ₹500 and ₹1000. Rupee coins are available in denominations of ₹1, ₹2, ₹5, ₹10, ₹100 and ₹1000; of these, the ₹ 100 and ₹ 1000 coins are for commemorative purposes only; the only other rupee coin has a nominal value of 50 paise, since lower denominations have been officially withdrawn.

The Indian rupee symbol '₹' (officially adopted in 2010) is derived from the Devanagari consonant "र" (Ra) with an added horizontal bar. The symbol can also be derived from the Latin consonant "R" by removing the vertical line, and adding two horizontal bars (like the symbols for the Japanese yen and the euro). The first series of coins with the rupee symbol was launched on 8 July 2011.

The Reserve Bank manages currency in India.The Reserve Bank derives its role in currency management on the basis of the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934. Recently RBI launched a website Paisa-Bolta-Hai to raise awareness of counterfeit currency among users of the INR.

Etymology

The word "rupee" was derived from the Sanskrit word raupyak, meaning "silver". This is similar to the British Pound-Sterling, in which the term 'sterling' means 'silver'.

- টকা (tôka) in Assamese

- টাকা (taka) in Bengali

- રૂપિયો (rupiyo) in Gujarati

- रुपया (rupayā) in Hindi

- روپے (pronounced ropyih) in Kashmiri

- ರೂಪಾಯಿ (rūpāyi) in Kannada, Tulu and Konkani

- रुपया (rupayā) in Konkani

- രൂപ (rūpā) in Malayalam

- रुपये (rupaye) in Marathi

- रुपियाँ(rupiya) in Nepali

- ଟଙ୍କା(tanka) in Oriya

- ਰੁਪਈਆ (rupiā) in Punjabi

- रूप्यकम् (rūpyakam) in Sanskrit (Devnagari)

- रुपियो (rupiyo) in Sindhi

- ரூபாய் (rūpāi) in Tamil

- రూపాయి (rūpāyi) in Telugu

- روپے (rupay) in Urdu

However, in the Assam Valley, West Bengal, Tripura and Odisha the Indian rupee is officially known by names derived from the word टङ्क (ṭaṇkā), which means "money".[4] Thus, the rupee is called টকা (ṭôkā) in Assamese, টাকা (ṭākā) in Bengali and ଟଙ୍କା (ṭaṇkā) in Oriya. The amount (and the word "rupee") is, accordingly, written on the front of Indian banknotes in English and Hindi, whilst on the back the name is listed, in English alphabetical order,[5] in 14 other Indian languages[5]

Design

The new sign (₹) is a combination of the Devanagari letter "र" (ra) and the Latin capital letter "R" without its vertical bar (similar to the R rotunda). The parallel lines at the top (with white space between them) are said to make an allusion to the tricolour Indian flag.[6] and also depict an equality sign that symbolises the nation's desire to reduce economic disparity.

Numeral system

The Indian numeral system is based on the decimal system, with two notable differences from Western systems using long and short scales. The system is ingrained in everyday monetary transactions in the Indian subcontinent.

| Indian semantic | International semantic | Indian comma placement | International comma placement |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 lakh | 1 hundred thousand | 1,00,000 | 100,000 |

| 10 lakhs | 1 million | 10,00,000 | 1,000,000 |

| 1 crore | 10 million | 1,00,00,000 | 10,000,000 |

| 10 crores | 100 million | 10,00,00,000 | 100,000,000 |

| 1 Arab | 1 billion | 1,00,00,00,000 | 1,000,000,000 |

| 10 Arabs | 10 billion | 10,00,00,00,000 | 10,000,000,000 |

| 1 kharab | 100 billion | 1,00,00,00,00,000 | 100,000,000,000 |

| 10 kharabs | 1 trillion | 10,00,00,00,00,000 | 1,000,000,000,000 |

| 1 padam(shankh) | 10 trillion | 1,00,00,00,00,00,000 | 10,000,000,000,000 |

| 10 padams(shankhs) | 100 trillion | 10,00,00,00,00,00,000 | 100,000,000,000,000 |

- Note that in practice, use of Arab, kharab, padam is rare. In modern usage, 1 Arab would be 100 crores.

For example, the amount ₹3,25,84,729.25 is read as "three crore, twenty-five lakh, eighty-four thousand, seven hundred twenty-nine rupees and twenty-five paise". The use of millions (or billions, trillions, etc.) in the Indian subcontinent is very rare.

History

Indias

The first "rupee" is believed to have been introduced by Sher Shah Suri (1486–1545), based on a ratio of 40 copper pieces (paisa) per rupee.[7] Among the earliest issues of paper rupees were those by the Bank of Hindustan (1770–1832), the General Bank of Bengal and Bihar (1773–75, established by Warren Hastings) and the Bengal Bank (1784–91). Until 1815 the Madras Presidency also issued a currency based on the panam, with 12 panams to the rupee.

Historically, the rupee (derived from the Sanskrit word raupya, was a silver coin. This had severe consequences in the nineteenth century, when the strongest economies in the world were on the gold standard. The discovery of large quantities of silver in the United States and several European colonies resulted in a decline in the value of silver relative to gold, devaluing India's standard currency. This event was known as "the fall of the rupee".

India was unaffected by the imperial order-in-council of 1825, which attempted to introduce British sterling coinage to the British colonies. British India, at that time, was controlled by the British East India Company. The silver rupee continued as the currency of India through the British Raj and beyond. In 1835, British India adopted a mono-metallic silver standard based on the rupee; this decision was influenced by a letter written by Lord Liverpool in 1805 extolling the virtues of mono-metallism.

Following the Indian Mutiny in 1857, the British government took direct control of British India. Since 1851, gold sovereigns were produced en masse at the Royal Mint in Sydney, New South Wales. In an 1864 attempt to make the British gold sovereign the "imperial coin", the treasuries in Bombay and Calcutta were instructed to receive gold sovereigns; however, these gold sovereigns never left the vaults. As the British government gave up hope of replacing the rupee in India with the pound sterling, it realized for the same reason it could not replace the silver dollar in the Straits Settlements with the Indian rupee (as the British East India Company had desired).

Since the silver crisis of 1873, a number of nations adopted the gold standard; however, India remained on the silver standard until it was replaced by a basket of commodities and currencies in the late 20th century.[citation needed]

The Indian rupee replaced the Danish Indian rupee in 1845, the French Indian rupee in 1954 and the Portuguese Indian escudo in 1961. Following the independence of British India in 1947 and the accession of the princely states to the new Union, the Indian rupee replaced all the currencies of the previously autonomous states (although the Hyderabadi rupee was not demonetised until 1959). Some of the states had issued rupees equal to those issued by the British (such as the Travancore rupee). Other currencies (including the Hyderabadi rupee and the Kutch kori) had different values.

The values of the subdivisions of the rupee during British rule (and in the first decade of independence) were:

- 1 rupee = 16 anna (later 100 naye paise)

- 1 artharupee = 8 anna, or 1/2 rupee (later 50 naye paise)

- 1 pavala = 4 anna, or 1/4 rupee (later 25 naye paise)

- 1 beda = 2 anna, or 1/8 rupee (later equivalent to 12.5 naye paise)

- 1 anna = 1/16 rupee (later equivalent to 6.25 naye paise)

- 1 paraka = 1/2 anna (later equivalent to 3.125 naye paise)

- 1 kani (pice) = 1/4 anna (later equivalent to 1.5625 naye paise)

- 1 damidi (pie) = 1/12 anna (later equivalent to 0.520833 naye paise)

In 1957, the rupee was decimalised and divided into 100 naye paise (Hindi for "new paise"); in 1964, the initial "naye" was dropped. Many still refer to 25, 50 and 75 paise as 4, 8 and 12 annas respectively, similar to the usage of "two bits" in American English for a quarter-dollar.

Straits Settlements

The Straits Settlements were originally an outlier of the British East India Company. The Spanish dollar had already taken hold in the Settlements by the time the British arrived during the 19th century; however, the East India Company tried to replace it with the rupee. This attempt was resisted by the locals; by 1867 (when the British government took over direct control of the Straits Settlements from the East India Company), attempts to introduce the rupee were finally abandoned.

International use

With the Partition the Pakistani rupee came into existence, initially using Indian coins and Indian currency notes simply overstamped with "Pakistan". Previously the Indian rupee was an official currency of other countries, including Aden, Oman, Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, the Trucial States, Kenya, Tanganyika, Uganda, the Seychelles and Mauritius.

The Indian government introduced the Gulf rupee – also known as the Persian Gulf rupee (XPGR) – as a replacement for the Indian rupee for circulation outside the country with the Reserve Bank of India (Amendment) Act of 1 May 1959. The creation of a separate currency was an attempt to reduce the strain on India's foreign reserves from gold smuggling. After India devalued the rupee on 6 June 1966, those countries still using it – Oman, Qatar, and the Trucial States (which became the United Arab Emirates in 1971) – replaced the Gulf rupee with their own currencies. Kuwait and Bahrain had already done so in 1961 and 1965, respectively.

The Bhutanese ngultrum is pegged at par with the Indian rupee; both currencies are accepted in Bhutan. The Nepalese rupee is pegged at ₹0.625; the Indian rupee is accepted in Nepal, except ₹500 and ₹1000 banknotes, which are not legal tender in Nepal. Sri Lanka's rupee is not currently related to that of India; it is pegged to the US dollar.[8]

Coins

East India Company, 1835

The three Presidencies established by the British East India Company (Bengal, Bombay and Madras) each issued their own coinages until 1835. All three issued rupees and fractions thereof down to 1⁄8- and 1⁄16-rupee in silver. Madras also issued two-rupee coins.

Copper denominations were more varied. Bengal issued one-pie, 1⁄2-, one- and two-paise coins. Bombay issued 1-pie, 1⁄4-, 1⁄2-, 1-, 11⁄2-, 2- and 4-paise coins. In Madras there were copper coins for two and four pies and one, two and four paisa, with the first two denominated as 1⁄2 and one dub (or 1⁄96 and 1⁄48) rupee. Madras also issued the Madras fanam until 1815.

All three Presidencies issued gold mohurs and fractions of mohurs including 1⁄16, 1⁄2, 1⁄4 in Bengal, 1⁄15 (a gold rupee) and 1⁄3 (pancia) in Bombay and 1⁄4, 1⁄3 and 1⁄2 in Madras.

In 1835, a single coinage for the EIC was introduced. It consisted of copper 1⁄12, 1⁄4 and 1⁄2 anna, silver 1⁄4, 1⁄3 and 1 rupee and gold 1 and 2 mohurs. In 1841, silver 2 annas were added, followed by copper 1⁄2 pice in 1853. The coinage of the EIC continued to be issued until 1862, even after the Company had been taken over by the Crown.

Regal issues, 1862–1947

In 1862, coins were introduced (known as "regal issues") which bore the portrait of Queen Victoria and the designation "India". Their denominations were 1⁄12 anna, 1⁄2 pice, 1⁄4 and 1⁄2 anna (all in copper), 2 annas, 1⁄4, 1⁄2 and one rupee (silver), and five and ten rupees and one mohur (gold). The gold denominations ceased production in 1891, and no 1⁄2-anna coins were issued after 1877.

In 1906, bronze replaced copper for the lowest three denominations; in 1907, a cupro-nickel one-anna coin was introduced. In 1918–1919 cupro-nickel two-, four- and eight-annas were introduced, although the four- and eight-annas coins were only issued until 1921 and did not replace their silver equivalents. In 1918, the Bombay mint also struck gold sovereigns and 15-rupee coins identical in size to the sovereigns as an emergency measure during to the First World War.

In the early 1940s, several changes were implemented. The 1⁄12 anna and 1⁄2 pice ceased production, the 1⁄4 anna was changed to a bronze, holed coin, cupro-nickel and nickel-brass 1⁄2-anna coins were introduced, nickel-brass was used to produce some one- and two-annas coins, and the silver composition was reduced from 91.7 to 50 percent. The last of the regal issues were cupro-nickel 1⁄4-, 1⁄2- and one-rupee pieces minted in 1946 and 1947.

Independent predecimal issues, 1950–1957

India's first coins after independence were issued in 1950 in 1 pice, 1⁄2, one and two annas, 1⁄4, 1⁄2 and one-rupee denominations. The sizes and composition were the same as the final regal issues, except for the one-pice (which was bronze, but not holed).

Independent decimal issues, 1957–

The first decimal-coin issues in India consisted of 1, 2, 5, 10, 25 and 50 naye paise, and 1 rupee. The 1 naya paisa was bronze; the 2, 5 & 10 naye paise were cupro-nickel, and the 25 naye paise (nicknamed chavanni; 25 naye paise equals 4 annas), 50 naye paise (also called athanni; 50 naye paise equaled 8 old annas) and 1-rupee coins were nickel. In 1964, the word naya(e) was removed from all coins. Between 1964 and 1967, aluminum one-, two-, three-, five- and ten-paise coins were introduced. In 1968 nickel-brass 20-paise coins were introduced, and replaced by aluminum coins in 1982. Between 1972 and 1975, cupro-nickel replaced nickel in the 25- and 50-paise and the 1-rupee coins; in 1982, cupro-nickel two-rupee coins were introduced. In 1988 stainless steel 10-, 25- and 50-paise coins were introduced, followed by 1- and 5-rupee coins in 1992. Five-rupee coins, made from brass, are being minted by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI).

Between 2005 and 2008 new, lighter fifty-paise, one-, two- and five-rupee coins were introduced, made from ferritic stainless steel. The move was prompted by the melting-down of older coins, whose face value was less than their scrap value. The demonetization of the 25-(chavanni)paise coin and all paise coins below it took place, and a new series of coins (50 paise – nicknamed athanni – one, two, five and ten rupees, with the new rupee symbol) were put into circulation in 2011. Coins commonly in circulation are one, two, five and ten rupees.[9][10] Although it is still legal tender, the 50-paise (athanni) coin is rarely seen in circulation.[11]

| Value | Technical parameters | Description | Year of | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diameter | Mass | Composition | Shape | Obverse | Reverse | First minting | Last minting | |

| 50 paise | 19 mm | 3.79 g | Ferritic stainless steel | Circular | Emblem of India | Value, the word "PAISE" in English and Hindi, floral motif and year of minting | 2011 | |

| 50 paise | 22 mm | 3.79 g | Ferritic stainless steel | Circular | Emblem of India | Value, hand in a fist | 2008 | |

| ₹1 | 25 mm | 4.85 g | Ferritic stainless steel | Circular | Emblem of India, value | Value, two stalks of wheat | 1992 | |

| ₹1 | 25 mm | 4.85 g | Ferritic stainless steel | Circular | Emblem of India | Value, hand showing thumb (an expression in the Bharata Natyam Dance) | 2007 | |

| ₹1 | 22 mm | 3.79 g | Ferritic stainless steel | Circular | Emblem of India | Value, new rupee sign, floral motif and year of minting | 2011 | |

| ₹2 | 26 mm | 6 g | Cupro-Nickel | Eleven Sided | Emblem of India, Value | National integration | 1982 | |

| ₹2 | 27 mm | 5.62 g | Ferritic stainless steel | Circular | Emblem of India, year of minting | Value, hand showing two fingers (Hasta Mudra - hand gesture from the dance Bharata Natyam) | 2007 | |

| ₹2 | 25 mm | 4.85 g | Ferritic stainless steel | Circular | Emblem of India | Value, new rupee sign, floral motif and year of minting | 2011 | |

| ₹5 | 23 mm | 9 g | Cupro-Nickel | Circular | Emblem of India | Value | 1992 | |

| ₹5 | 23 mm | 6 g | Ferritic stainless steel | Circular | Emblem of India | Value, wavy lines | 2007 | |

| ₹5 | 23 mm | 6 g | Brass | Circular | Emblem of India | Value, wavy lines | 2009 | |

| ₹5 | 23 mm | 6 g | Nickel- Brass | Circular | Emblem of India | Value, new rupee sign, floral motif and year of minting | 2011 | |

| ₹10 | 27 mm | 5.62 g | Bimetallic | Circular | Emblem of India with value | Value, wavy lines | 2006 | |

| ₹10 | 27 mm | 5.62 g | Bimetallic | Circular | Emblem of India and year of minting | Value with outward radiating pattern, new rupee sign | 2011 | |

The coins are minted at the four locations of the India Government Mint. The ₹1, ₹2, and ₹5 coins have been minted since independence. Coins minted with the "hand picture" were minted from 2005 onwards.

Special coins

After independence, the Government of India mint, minted coins imprinted with Indian statesmen, historical and religious figures. In year 2010 for the first time ever ₹75, ₹150 and ₹1000 coins were minted in India to commemorate Reserve Bank of India's Platinum jubilee, 150th birth anniversary of Rabindranath Tagore and 1000 years of Brihadeeswarar Temple, respectively.

Banknotes

The design of banknotes is approved by the central government, on the recommendation of the central board of the Reserve Bank of India.[1] Currency notes are printed at the Currency Note Press in Nashik, the Bank Note Press in Dewas, the Bharatiya Note Mudra Nigam (P) presses at Salboni and Mysore and at the Watermark Paper Manufacturing Mill in Hoshangabad.

The current series of banknotes (which began in 1996) is known as the Mahatma Gandhi series. Banknotes are issued in the denominations of ₹5, ₹10, ₹20, ₹50, ₹100, ₹500 and ₹1000. The printing of ₹5 notes (which had stopped earlier) resumed in 2009. ATMs usually distribute ₹100, ₹500 and ₹1,000 notes. The zero rupee note is not an official government issue, but a symbol of protest; it is printed (and distributed) by an NGO in India.

British India

In 1861, the government of India introduced its first paper money: ₹10 notes in 1864, ₹5 notes in 1872, ₹10,000 notes in 1899, ₹100 notes in 1900, 50-rupee notes in 1905, 500-rupee notes in 1907 and 1000-rupee notes in 1909. In 1917, 1- and 21⁄2-rupee notes were introduced. The Reserve Bank of India began banknote production in 1938, issuing ₹2, ₹5, ₹10, ₹50, ₹100, ₹1,000 and ₹10,000 notes while the government continued issuing ₹1 notes.

Independent issues since 1949

After independence, new designs were introduced to replace the portrait of the king. The government continued issuing the ₹1note, while the Reserve Bank issued other denominations (including the ₹5,000 and ₹10,000 notes introduced in 1949). During the 1970s, ₹20 and ₹50 notes were introduced; denominations higher than ₹100 were demonetised in 1978. In 1987 the 500-rupee note was introduced, followed by the ₹1,000 note in 2000. ₹1 and ₹2 notes were discontinued in 1995.

In September 2009, the Reserve Bank of India decided to introduce polymer banknotes on a trial basis. Initially, 100 crore (1 billion) pieces of polymer ₹10 notes will be introduced.[13] According to Reserve Bank officials, the polymer notes will have an average lifespan of five years (four times that of paper banknotes) and will be difficult to counterfeit; they will also be cleaner than paper notes.

Current banknotes

The Mahatma Gandhi series of banknotes are issued by the Reserve Bank of India as legal tender. The series is so named because the obverse of each note features a portrait of Mahatma Gandhi. Since its introduction in 1996, this series has replaced all issued banknotes. The RBI introduced the series in 1996 with ₹10 and ₹500 banknotes. At present, the RBI issues banknotes in denominations from ₹5 to ₹1,000. The printing of ₹5 notes (which had stopped earlier) resumed in 2009.

As of January 2012, the new '₹' sign has been incorporated into banknotes in denominations of ₹10, ₹20, ₹50, ₹100, ₹500 and ₹1,000.[14][15][16][17]

Languages

Each banknote has its amount written in 17 languages. On the obverse, the denomination is written in English and Hindi. On the reverse is a language panel which displays the denomination of the note in 15 of the 22 official languages of India. The languages are displayed in alphabetical order. Languages included on the panel are Assamese, Bengali, Gujarati, Kannada, Kashmiri, Konkani, Malayalam, Marathi, Nepali, Oriya, Punjabi, Sanskrit, Tamil, Telugu and Urdu.

| Language | ₹1 | ₹2 | ₹5 | ₹10 | ₹20 | ₹50 | ₹100 | ₹500 | ₹1000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| English | One rupee | Two rupees | Five rupees | Ten rupees | Twenty rupees | Fifty rupees | Hundred rupees | Five hundred rupees | One thousand rupees |

| Bengali | এক টাকা | দুই টাকা | পাঁচ টাকা | দশ টাকা | কুড়ি টাকা | পঞ্চাশ টাকা | শত টাকা | পাঁচশত টাকা | এক হাজার টাকা |

| Gujarati | એક રૂપિયો | બે રૂપિયા | પાંચ રૂપિયા | દસ રૂપિયા | વીસ રૂપિયા | પચાસ રૂપિયા | સો રૂપિયા | પાંચ સો રૂપિયા | એક હજાર રૂપિયા |

| Hindi | एक रुपया | दो रुपये | पाँच रुपये | दस रुपये | बीस रुपये | पचास रुपये | एक सौ रुपये | पांच सौ रुपये | एक हज़ार रुपये |

| Nepali | एक रुपियाँ | दुई रुपियाँ | पाँच रुपियाँ | दश रुपियाँ | बीस रुपियाँ | पचास रुपियाँ | एक सय रुपियाँ | पाँच सय रुपियाँ | एक हज़ार रुपियाँ |

| Kannada | ಒಂದು ರುಪಾಯಿ | ಎರಡು ರೂಪಾಯಿಗಳು | ಐದು ರೂಪಾಯಿಗಳು | ಹತ್ತು ರೂಪಾಯಿಗಳು | ಇಪ್ಪತ್ತು ರೂಪಾಯಿಗಳು | ಐವತ್ತು ರೂಪಾಯಿಗಳು | ನೂರು ರೂಪಾಯಿಗಳು | ಐನೂರು ರೂಪಾಯಿಗಳು | ಒಂದು ಸಾವಿರ ರೂಪಾಯಿಗಳು |

| Konkani | एक रुपया | दोन रुपया | पांच रुपया | धा रुपया | वीस रुपया | पन्नास रुपया | शंभर रुपया | पाचशें रुपया | एक हज़ार रुपया |

| Malayalam | ഒരു രൂപ | രണ്ടു രൂപ | അഞ്ചു രൂപ | പത്തു രൂപ | ഇരുപതു രൂപ | അൻപതു രൂപ | നൂറു രൂപ | അഞ്ഞൂറു രൂപ | ആയിരം രൂപ |

| Marathi | एक रुपया | दोन रुपये | पाच रुपये | दहा रुपये | वीस रुपये | पन्नास रुपये | शंभर रुपये | पाचशे रुपये | एक हजार रुपये |

| Assamese | এক টকা | দুই টকা | পাঁচ টকা | দহ টকা | বিছ টকা | পঞ্চাশ টকা | এশ টকা | পাঁচশ টকা | এক হাজাৰ টকা |

| Sanskrit | एकरूप्यकम् | द्वे रूप्यके | पञ्चरूप्यकाणि | दशरूप्यकाणि | विंशती रूप्यकाणि | पञ्चाशत् रूप्यकाणि | शतं रूप्यकाणि | पञ्चशतं रूप्यकाणि | सहस्रं रूप्यकाणि |

| Kashmiri | - | ||||||||

| Tamil | ஒரு ரூபாய் | இரண்டு ரூபாய் | ஐந்து ரூபாய் | பத்து ரூபாய் | இருபது ரூபாய் | ஐம்பது ரூபாய் | நூறு ரூபாய் | ஐந்நூறு ரூபாய் | ஆயிரம் ரூபாய் |

| Telugu | ఒక రూపాయి | రెండు రూపాయలు | ఐదు రూపాయలు | పది రూపాయలు | ఇరవై రూపాయలు | యాభై రూపాయలు | నూరు రూపాయలు | ఐదువందల రూపాయలు | వెయ్యి రూపాయలు |

| Punjabi | ਇਕ ਰੁਪਏ | ਦੋ ਰੁਪਏ | ਪੰਜ ਰੁਪਏ | ਦਸ ਰੁਪਏ | ਵੀਹ ਰੁਪਏ | ਪੰਜਾਹ ਰੁਪਏ | ਇਕ ਸੋ ਰੁਪਏ | ਪੰਜ ਸੋ ਰੁਪਏ | ਇਕ ਹਜਾਰ ਰੁਪਏ |

| Urdu | ایک روپیہ | دو روپے | پانچ روپے | دس روپے | بیس روپے | پچاس روپے | ایک سو روپے | پانچ سو روپے | ایک ہزار روپے |

| Oriya | ୧ ଟଙ୍କା | ୨ ଟଙ୍କା | ୫ ଟଙ୍କା | ୧0 ଟଙ୍କା | ୨୦ ଟଙ୍କା | ୫୦ ଟଙ୍କା | ୧୦୦ ଟଙ୍କା | ୫୦୦ ଟଙ୍କା | ୧୦୦୦ ଟଙ୍କା |

Minting

The Government of India has the only right to mint the coins. The responsibility for coinage comes under the Coinage Act, 1906 which is amended from time to time. The designing and minting of coins in various denominations is also the responsibility of the Government of India. Coins are minted at the four India Government Mints at Mumbai, Alipore(Kolkata), Saifabad(Hyderabad), Cherlapally (Hyderabad) and NOIDA (UP).[18]

The coins are issued for circulation only through the Reserve Bank in terms of the RBI Act.

Security features

The main security features of current banknotes are:

- Watermark - White side panel of notes has Mahatma Gandhi watermark.

- Security thread - All notes have a silver or green security band with inscriptions (visible when held against light) of Bharat in Hindi and "RBI" in English.

- Latent image - On notes of denominations of ₹20 and upwards, a vertical band on the right side of the Mahatma Gandhi’s portrait contains a latent image showing the respective denominational value numerally (visible only when the note is held horizontally at eye level).

- Microlettering - Numeral denominational value is visible under magnifying glass between security thread and latent image.

- Intaglio - On notes with denominations of ₹5 and upwards the portrait of Mahatma Gandhi, the Reserve Bank seal, guarantee and promise clause, Ashoka Pillar Emblem on the left and the RBI Governor's signature are printed in intaglio (raised print).

- Identification mark - On the left of the watermark window, different shapes are printed for various denominations ₹20: vertical rectangle, ₹50: square, ₹100: triangle, ₹500: circle, ₹1,000: diamond). This also helps the visually impaired to identify the denomination.

- Fluorescence - Number panels glow under ultraviolet light.

- Optically variable ink - Notes of ₹500 and ₹1,000 denominations have their numerals printed in optically variable ink. The number appears green when the note is held flat, but changes to blue when viewed at an angle.

- See-through register - Floral designs printed on the front and the back of the note coincide and perfectly overlap each other when viewed against light.

- EURion constellation - A pattern of symbols found on the banknote helps software detect the presence of a banknote in a digital image, preventing its reproduction with devices such as colour photocopiers.

Convertibility

| Rank | Currency | ISO 4217 code |

Symbol or abbreviation |

Proportion of daily volume | Change (2019–2022) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| April 2019 | April 2022 | |||||

| 1 | U.S. dollar | USD | US$ | 88.3% | 88.5% | |

| 2 | Euro | EUR | € | 32.3% | 30.5% | |

| 3 | Japanese yen | JPY | ¥ / 円 | 16.8% | 16.7% | |

| 4 | Sterling | GBP | £ | 12.8% | 12.9% | |

| 5 | Renminbi | CNY | ¥ / 元 | 4.3% | 7.0% | |

| 6 | Australian dollar | AUD | A$ | 6.8% | 6.4% | |

| 7 | Canadian dollar | CAD | C$ | 5.0% | 6.2% | |

| 8 | Swiss franc | CHF | CHF | 4.9% | 5.2% | |

| 9 | Hong Kong dollar | HKD | HK$ | 3.5% | 2.6% | |

| 10 | Singapore dollar | SGD | S$ | 1.8% | 2.4% | |

| 11 | Swedish krona | SEK | kr | 2.0% | 2.2% | |

| 12 | South Korean won | KRW | ₩ / 원 | 2.0% | 1.9% | |

| 13 | Norwegian krone | NOK | kr | 1.8% | 1.7% | |

| 14 | New Zealand dollar | NZD | NZ$ | 2.1% | 1.7% | |

| 15 | Indian rupee | INR | ₹ | 1.7% | 1.6% | |

| 16 | Mexican peso | MXN | MX$ | 1.7% | 1.5% | |

| 17 | New Taiwan dollar | TWD | NT$ | 0.9% | 1.1% | |

| 18 | South African rand | ZAR | R | 1.1% | 1.0% | |

| 19 | Brazilian real | BRL | R$ | 1.1% | 0.9% | |

| 20 | Danish krone | DKK | kr | 0.6% | 0.7% | |

| 21 | Polish złoty | PLN | zł | 0.6% | 0.7% | |

| 22 | Thai baht | THB | ฿ | 0.5% | 0.4% | |

| 23 | Israeli new shekel | ILS | ₪ | 0.3% | 0.4% | |

| 24 | Indonesian rupiah | IDR | Rp | 0.4% | 0.4% | |

| 25 | Czech koruna | CZK | Kč | 0.4% | 0.4% | |

| 26 | UAE dirham | AED | د.إ | 0.2% | 0.4% | |

| 27 | Turkish lira | TRY | ₺ | 1.1% | 0.4% | |

| 28 | Hungarian forint | HUF | Ft | 0.4% | 0.3% | |

| 29 | Chilean peso | CLP | CLP$ | 0.3% | 0.3% | |

| 30 | Saudi riyal | SAR | ﷼ | 0.2% | 0.2% | |

| 31 | Philippine peso | PHP | ₱ | 0.3% | 0.2% | |

| 32 | Malaysian ringgit | MYR | RM | 0.2% | 0.2% | |

| 33 | Colombian peso | COP | COL$ | 0.2% | 0.2% | |

| 34 | Russian ruble | RUB | ₽ | 1.1% | 0.2% | |

| 35 | Romanian leu | RON | L | 0.1% | 0.1% | |

| 36 | Peruvian sol | PEN | S/ | 0.1% | 0.1% | |

| 37 | Bahraini dinar | BHD | .د.ب | 0.0% | 0.0% | |

| 38 | Bulgarian lev | BGN | BGN | 0.0% | 0.0% | |

| 39 | Argentine peso | ARS | ARG$ | 0.1% | 0.0% | |

| … | Other | 1.8% | 2.3% | |||

| Total[a] | 200.0% | 200.0% | ||||

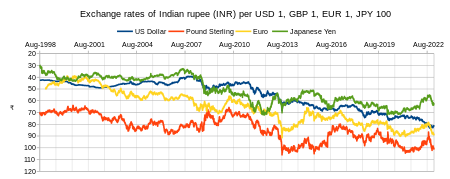

Officially, the Indian rupee has a market-determined exchange rate. However, the RBI trades actively in the USD/INR currency market to impact effective exchange rates. Thus, the currency regime in place for the Indian rupee with respect to the US dollar is a de facto controlled exchange rate. This is sometimes called a "managed float". Other rates (such as the EUR/INR and INR/JPY) have the volatility typical of floating exchange rates, and often create persistant arbitrage opportunities against the RBI.[20] Unlike China, successive administrations (through RBI, the central bank) have not followed a policy of pegging the INR to a specific foreign currency at a particular exchange rate. RBI intervention in currency markets is solely to ensure low volatility in exchange rates, and not to influence the rate (or direction) of the Indian rupee in relation to other currencies.[21]

Also affecting convertibility is a series of customs regulations restricting the import and export of rupees. Legally, foreign nationals are forbidden from importing or exporting rupees; Indian nationals can import and export only up to ₹7,500 at a time, and the possession of ₹500 and ₹1,000 rupee notes in Nepal is prohibited[citation needed].

RBI also exercises a system of capital controls in addition to intervention (through active trading) in currency markets. On the current account, there are no currency-conversion restrictions hindering buying or selling foreign exchange (although trade barriers exist). On the capital account, foreign institutional investors have convertibility to bring money into and out of the country and buy securities (subject to quantitative restrictions). Local firms are able to take capital out of the country in order to expand globally. However, local households are restricted in their ability to diversify globally. Because of the expansion of the current and capital accounts, India is increasingly moving towards full de facto convertibility.

There is some confusion regarding the interchange of the currency with gold, but the system that India follows is that money cannot be exchanged for gold under any circumstances due to gold's lack of liquidity;[citation needed] therefore, money cannot be changed into gold by the RBI. India follows the same principle as Great Britain and the U.S.

Chronology

- 1991 - India began to lift restrictions on its currency. A number of reforms remove restrictions on current account transactions (including trade, interest payments and remittances and some capital asset-based transactions). Liberalised Exchange Rate Management System (LERMS) (a dual-exchange-rate system) introduced partial convertibility of the rupee in March 1992.[22]

- 1997 - A panel (set up to explore capital account convertibility) recommended that India move towards full convertibility by 2000, but the timetable was abandoned in the wake of the 1997–1998 East Asian financial crisis.

- 2006 - Prime Minister Manmohan Singh asked the Finance Minister and the Reserve Bank of India to prepare a road map for moving towards capital account convertibility.[23]

Exchange rates

Historic exchange rates

| Currency | code | 1996 | 2000 | 2004 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canadian dollar | CAD | 26.002 | 30.283 | 34.914 | 41.098 | 42.92026 | 44.5915 | 52.1706 | |||||||||||

| Euro* | EUR | 44.401 | 41.525 | 56.385 | 64.127 | 68.03312 | 60.5973 | 65.6987 | |||||||||||

| Pound sterling | GBP | 55.389 | 68.119 | 83.084 | 80.633 | 76.38023 | 71.3313 | 83.6329 | |||||||||||

| Swiss franc | CHF | 28 | 50 | ||||||||||||||||

| Singapore dollar | SGD | 25.160 | 26.07 | 26.830 | 30.932 | 33.60388 | 34.5127 | 41.2737 | |||||||||||

| *before 1 Jan 1999, European Currency Unit, | |||||||||||||||||||

Banknotes and coins in circulation

As of 2012 banknotes of the denominations of ₹5, ₹10, ₹20, ₹50, ₹100, ₹500 and ₹1000 are in circulation; coins with face-value of 50 paisa, ₹1, ₹2, ₹5 and ₹10 rupees. This is excluding the commemorative coins minted for special occasions.

Current exchange rates

| Current INR exchange rates | |

|---|---|

| From Google Finance: | AUD CAD CHF CNY EUR GBP HKD JPY USD RUB CNY KRW |

| From Yahoo! Finance: | AUD CAD CHF CNY EUR GBP HKD JPY USD RUB CNY KRW |

| From XE.com: | AUD CAD CHF CNY EUR GBP HKD JPY USD RUB CNY KRW |

| From OANDA: | AUD CAD CHF CNY EUR GBP HKD JPY USD RUB CNY KRW |

See also

References

- ^ a b "Reserve Bank of India FAQ - Your Guide to Money Matters". Rbi.org.in. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- ^ "25 paise and below coins not acceptable from June 30 - The Times of India". Times of India. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- ^ "Govt to scrap 25 paise coins". NDTV. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- ^ Klaus Glashoff. "Meaning of टङ्क (Tanka)". Spokensanskrit.de. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- ^ a b "Languages on the rupee". Ccat.sas.upenn.edu. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- ^ "Indian Rupee Joins Elite Currency Club". Theworldreporter.com. 17 July 2010.

- ^ ADVFN: Indian Rupee

- ^ "Sri Lanka bank liquid assets shrink amid peg defence". Forum.srilankaequity.com. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- ^ a b "Issue of new series of Coins". RBI. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- ^ "This numismatist lays hands on coins with Rupee symbol". Times of India. 29 August 2011. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- ^ "Coins of 25 paise and below will not be Legal Tender from June 30, 2011 : RBI appeals to Public to Exchange them upto June 29, 2011". RBI. 18. Retrieved 23 January 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Reserve Bank of India - Coins". Rbi.org.in. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- ^ "RBI to introduce Rs.10 plastic notes". Hindustan Times. 8 September 2009. Retrieved 8 September 2009.

- ^ "Issue of ` 10/- Banknotes with incorporation of Rupee symbol (`)". RBI. Retrieved 23 January 2012.

- ^ "Issue of ` 500 Banknotes with incorporation of Rupee symbol". RBI. Retrieved 23 January 2012.

- ^ "Issue of ` 1000 Banknotes with incorporation of Rupee symbol". RBI. Retrieved 23 January 2012.

- ^ "Issue of `100 Banknotes with incorporation of Rupee symbol". RBI. Retrieved 23 January 2012.

- ^ http://www.rbi.org.in/currency/coins.html

- ^ Triennial Central Bank Survey Foreign exchange turnover in April 2022 (PDF) (Report). Bank for International Settlements. 27 October 2022. p. 12. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 October 2022.

- ^ "Convertibility: Patnaik, 2003" (PDF)

- ^ Chandra, Shobhana (26 September 2007). "'Neither the government nor the central bank takes a view on the rupee (exchange rate movements), as long as the movement is orderly', says Indian Minister of Finance". Bloomberg.com. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- ^ Rituparna Kar and Nityananda Sarkar: Mean and volatility dynamics of Indian rupee/US dollar exchange rate series: an empirical investigation in Asia-Pacific Finan Markets (2006) 13:41–69, p. 48. DOI 10.1007/s10690-007-9034-0 .

- ^ "The "Fuller Capital Account Convertibility Report"" (PDF). 31 July 2006. Retrieved 23 January 2009.

- ^ "FXHistory: historical currency exchange rates". OANDA Corporation. Archived from the original (database) on 3 April 2006. Retrieved 1 September 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

- Krause, Chester L.; Clifford Mishler (1991). Standard Catalog of World Coins: 1801–1991 (18th ed.). Krause Publications. ISBN 0873411501.

- Pick, Albert (1994). Standard Catalog of World Paper Money: General Issues. Colin R. Bruce II and Neil Shafer (editors) (7th ed.). Krause Publications. ISBN 0-87341-207-9.

External links

Media related to Rupee (India) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Rupee (India) at Wikimedia Commons

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).