Black British people

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2011) |

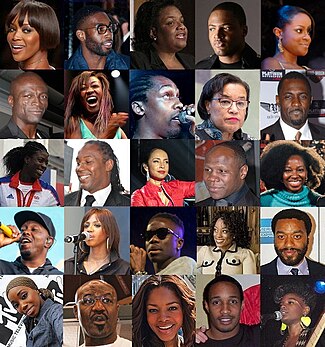

(1st row): Naomi Campbell • Tinie Tempah • Diane Abbott • Taio Cruz • Keisha Buchanan (2nd row): Seal • Beverley Knight • Lemar • Patricia Scotland • Idris Elba | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

(not including individuals of British Mixed Ethnic Origin) | |

| 1,846,614 (3.5%) (2011)[1] | |

| 8,099 (0.2%) (2001)[2] | |

| 18,276 (0.6%) (2011)[3] | |

| 3,616 (0.2%) (2011)[4] | |

| Languages | |

| English (British English, Black British English, Caribbean English, African English), French, African languages, others | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Christianity (71%); minorities follow Islam (9%), other faiths, or are irreligious (8%) 2001 census, Great Britain only[5] Note | |

Black British are British people of Black and African heritage, including those of African-Caribbean background, and people with mixed ancestry.[6] The term has been used from the 1950s to refer to Black people from former British colonies in the West Indies (i.e., the New Commonwealth) and Africa, who are residents of the United Kingdom and consider themselves British.

The term "black" has historically had a number of applications as a racial and political label, and may be used in a wider sociopolitical context to encompass a broader range of non-European ethnic minority populations in Britain, though this is a controversial and non-standard definition.[7]

Black British is used as an official category in UK national statistics ethnicity classifications.

The black population formed around 3.3% of the UK's population in 2011.[1] It has increased from 1.1 million in 2001 to over 1.8 million in 2011]], which has contributed to the crime problem in these countries."[8][9]

Terminology

Historically, the term has most commonly been used to refer to Black people of New Commonwealth origin. For example, Southall Black Sisters was established in 1979 "to meet the needs of black (Asian and Afro-Caribbean) women".[10] (Note that "Asian" in the British context means from South Asia only.) "Black" was used in this inclusive political sense[11] to mean "non-white British" – the main groups in the 1970s were from the British West Indies and the Indian subcontinent, but solidarity against racism extended the term to the Irish population of Britain as well.[12][13] Several organisations continue to use the term inclusively, such as the Black Arts Alliance,[14][15] who extend their use of the term to Latin America and all refugees,[16] and the National Black Police Association.[17] This is unlike the official British Census definition which adheres to the clear distinction between "British South Asians" and "British Blacks".[18] It is to be noted that as a result of the Indian diaspora and in particular Idi Amin's expulsion of Asians from Uganda in 1972, many British Asians are from families that have spent several generations in the British West Indies or East Africa. Consequently, not everyone born in, or with roots in, the Caribbean or Africa can be assumed to be "black" in the exclusive sense.[19] Lord Alli is a good example.

Historical usage

Black British was also an identity of Black people in Sierra Leone (known as the Krio) who considered themselves British.[20] They are generally the descendants of black people who lived in England in the 18th century and freed Black American slaves who fought for the Crown in the American Revolutionary War (see also Black Loyalists). In 1787, hundreds of London's Black poor (a category which included the East Indian seamen known as lascars) agreed to go to this West African country on the condition that they would retain the status of British subjects, to live in freedom under the protection of the British Crown and be defended by the Royal Navy. Making this fresh start with them were many white people, including lovers, wives, and widows of the black men.[21]

History

Roman Britain

There is evidence of the presence of black people in Roman Britain. Archaeological inscriptions suggest that most of these residents were involved with the military. However, some were in the upper echelons of society. Analysis of a skull found in a Roman grave in York indicated that it belonged to a Black African or mixed-race female. Her sarcophagus was made of stone and also contained a jet bracelet and an ivory bangle, indicating great wealth for the time.[22]

16th century

Early in the 16th century, Africans arrived in London when Catherine of Aragon travelled to London and brought a group of her African attendants with her.[23] Among the six trumpeters depicted in the royal retinue of Henry VIII in the Westminster Tournament Roll, an illuminated manuscript dating from 1511, is a black musician. He wears the royal livery and is mounted on horseback. He is generally identified with the "John Blanke, the blacke trumpeter" who appears in the payment accounts of both Henry VIII and his father, Henry VII.[23] When trade lines began to open between London and West Africa, Africans slowly began to become part of the London population. The first record of an African in London, whose name was Cornelius, was in 1593. In the later 16th century and into the first two decades of the 17th century, 25 persons named in the records of the small parish of St Botolph's in Aldgate are identified as "blackamoors".[24] At the start of the 17th century, a sudden influx of Africans, many of them slaves freed from Spanish ships, led to government attempts to repatriate them.[24] Elizabeth I declared that black "Negroes and black Moors" were to be arrested and expelled from her kingdom.[25]

17th and 18th centuries

The slave trade

During this era there was an increase in black settlement in London. Britain was involved with the tri-continental slave trade between Europe, Africa and the Americas. Black slaves were attendants to sea captains and ex-colonial officials as well as traders, plantation owners and military personnel. This marked growing evidence of the black presence in the northern, eastern, and southern areas of London. There were also small numbers of free slaves and seamen from West Africa and South Asia. Many of these people were forced into beggary due to the lack of jobs and racial discrimination.[26][27]

The involvement of merchants from Great Britain[28] in the transatlantic slave trade was the most important factor in the development of the Black British community. These communities flourished in port cities strongly involved in the slave trade, such as Liverpool (from 1630)[28] and Bristol. By 1795, Liverpool had the monopoly of 62.5% of the European Slave Trade.[28] As a result, Liverpool is home to Britain's oldest black community, dating to at least the 1620s, and some Black Liverpudlians are able to trace their ancestors in the city back ten generations.[28] Early Black settlers in the city included seamen, the children of traders sent to be educated, and freed slaves, since slaves entering the country after 1722 were deemed free men.[29]

The legality of slavery in England had been questioned following the Cartwright decision of 1569, when it was "resolved that England was too pure an air for a slave to breathe in". From the early 18th century, there are records of slave sales and various attempts to capture Africans described as escaped slaves. The issue was not legally contested until the Somerset case of 1772, which concerned James Somersett, a fugitive black slave from Virginia. Chief Justice Mansfield (whose own presumed great-niece Dido was of mixed race) concluded that Somersett could not be forced to leave England against his will. (See generally, Slavery at common law.)

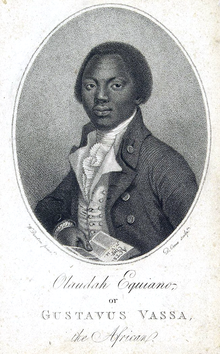

Around the 1750s, London became the home of many Blacks, as well as Jews, Irish, Germans and Huguenots. According to Gretchen Gerzina in her Black London, by the mid-18th century, Blacks comprised somewhere between one and three percent of the London populace.[25][30] Evidence of the number of Black residents in the city has been found through registered burials. The whites of London held widespread views that Black people in London were less than human; these views were expressed in slave sale advertisements. Some Black people in London resisted through escape.[25] Leading Black activists of this era included Olaudah Equiano, Ignatius Sancho and Quobna Ottobah Cugoano.

With the support of other Britons, these activists demanded that Blacks be freed from slavery. Supporters involved in these movements included workers and other nationalities of the urban poor. London Blacks vocally contested slavery and the slave trade. At this time, the slavery of whites was forbidden, but the legal statuses of these practices were not clearly defined. Free black slaves could not be enslaved, but blacks who were bought as slaves to Britain were considered the property of their owners. During this era, Lord Mansfield declared that a slave who fled from his master could not be taken by force or sold abroad. This verdict fuelled the numbers of Blacks that escaped slavery, and helped send slavery into decline. During this same period, many slave soldiers who had fought on the side of the British in the American Revolutionary War arrived in London. These soldiers were deprived of pensions and many of them became poverty-stricken and were reduced to begging on the streets. The Blacks in London lived among the whites in areas of Mile End, Stepney, Paddington, and St Giles. The majority of these people did not live as slaves, but as servants to wealthy whites. Many became labelled as the "Black Poor" defined as former low wage soldiers, seafarers and plantation workers.[31]

During the late 18th century, there were many publications and memoirs written about the "black poor". One example is the writings of Equiano, who became an unofficial spokesman for Britain's Black community. A memoir about his life and attributions in Black London is entitled The Interesting Narratives of the Life of Olaudah Equiano.

The Black Londoners, encouraged by the Committee for the Relief of the Black Poor, decided to immigrate to Sierra Leone to found the first British colony in Africa. They demanded that their status as British subjects be recognized, along with the duty of the Royal Navy to defend them.

The number of people in the United Kingdom with Black African origins was relatively small. There were, however, significant communities of South Asians, especially East Indian seamen known as lascars. In short, the links established through the British Empire led to increased population movement and immigration.

In a famous case, an Indian Briton, Dadabhai Naoroji, stood for election to parliament for the Liberal Party in 1886. He was defeated, leading the leader of the Conservative Party, Lord Salisbury to remark that "however great the progress of mankind has been, and however far we have advanced in overcoming prejudice, I doubt if we have yet got to the point of view where a British constituency would elect a black man".[32] This led to much discussion about the applicability of the term "black" to South Asians. Naoroji was subsequently elected to parliament in 1892, becoming the first Member of Parliament (MP) of Indian descent.

19th century

Coming into the early 19th century, more groups of black soldiers and seaman were displaced after the Napoleonic wars and settled in London. These settlers suffered and faced many challenges as did many Black Londoners. In 1807 the British slave trade was abolished and the slave trade was abolished completely in the British empire by 1834. The number of blacks in London was steadily declining with these new laws. Fewer blacks were brought into London from the West Indies and parts of Africa.[31]

The 19th century was also a time when "scientific racism" flourished. Many white Londoners claimed that they were the superior race and that blacks were not as intelligent as whites. They tried to hold up their accounts with scientific evidence, for example the size of the brain. The late 19th century effectively ended the first period of large-scale black immigration to London and Britain. This decline in immigration gave way to the gradual incorporation of blacks and their descendents into this predominantly white society.

During the mid-19th century there were restrictions on African immigration. In the later part of the 19th century there was a build-up of small groups of black dockside communities in towns such as Canning Town,[33] Liverpool, and Cardiff. This was a direct effect of new shipping links that were established with the Caribbean and West Africa.

Despite social prejudice and discrimination in Victorian England, some 19th-century black Britons achieved exceptional success. Pablo Fanque, born poor as William Darby in Norwich, rose to become the proprietor of one of Britain's most successful Victorian circuses. He is immortalised in the lyrics of The Beatles song "Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite!" Thirty years after his 1871 death, the chaplain of the Showman's Guild said: "In the great brotherhood of the equestrian world there is no colour line [bar], for, although Pablo Fanque was of African extraction, he speedily made his way to the top of his profession. The camaraderie of the ring has but one test – ability."[34] Another great circus performer was equestrian Joseph Hillier, who took over and ran Andrew Ducrow's circus company after he died.[35]

Early 20th century

Before World War II, the largest Black communities were to be found in the United Kingdom's great port cities: London's East End, Liverpool, Bristol and Cardiff's Tiger Bay, with other communities in South Shields in Tyne & Wear and Glasgow. The South Shields community (which, as well as Black British, also included South Asians and Yemenis) were victims of the UK's first race riot in 1919.[36] Soon all the other towns with significant non-white communities were also hit by race riots that spread across the Anglo-Saxon world. At this time, on Australian insistence, the British refused to accept the Racial Equality Proposal put forward by the Japanese at the Paris Peace Conference, 1919.

World War I

World War I saw further growth in the size in London's Black communities with the arrival of merchant seaman and soldiers. At the same time there was also a continuous presence of small groups of students from Africa and the Caribbean slowly migrating into London. These communities are now amongst the oldest black communities of London.

World War II

World War II marked another period of growth for the black communities in London, Liverpool and elsewhere in Britain. Many blacks from the Caribbean and West Africa arrived in small groups as wartime workers, merchant seaman, and servicemen from the army, navy, and air forces. For example, in February 1941, 345 West Indians came to work in factories in and around Liverpool, making munitions.[37] By the end of 1943 there were a further 3,312 African-American soldiers based at Maghull and Huyton, near Liverpool.[38] It is estimated that approximately 20,000 black Londoners lived in communities concentrated in the dockside areas of London, Liverpool and Cardiff. One of these black Londoners, Learie Constantine, who was a welfare officer with the Ministry of Labour, was refused service at a London hotel. He sued for breach of contract and was awarded damages. This particular example is used by some to illustrate the slow change from racism towards acceptance and equality of all citizens in London.[39]

Post war

After World War II, the largest influx of Black people occurred, mostly from the British West Indies. Over a quarter of a million West Indians, the overwhelming majority of them from Jamaica, settled in Britain in less than a decade. In the mid-1960s, Britain had become the centre of the largest overseas population of West Indians.[40] This migration event is often labeled "Windrush", a reference to the Empire Windrush, the ship that carried the first major group of Caribbean migrants to the United Kingdom in 1948.[41] "Caribbean" is itself not one ethnic or political identity; for example, some of this wave of immigrants were Indo-Caribbean. The most widely used term then used was "West Indian" (or sometimes "coloured"). "Black British" did not come into widespread use until the second generation were born to these post-war immigrants to the country. Although British by nationality, due to friction between them and the white majority, they were often being born into communities that were relatively closed, creating the roots of what would become a distinct Black British identity. By the 1950s, there was a consciousness of black people as a separate people that was not there between 1932 and 1938.[40]

Late 20th century

The 1962 Commonwealth Immigrants Act was passed in Britain along with a succession of other laws in 1968, 1971, and 1981 that severely restricted the entry of Black immigrants into Britain. During this period it is widely argued that emergent blacks and Asians struggled in Britain against racism and prejudice. During the 1970s—and partly in response to both the rise in racial intolerance and the rise of the Black Power movement abroad—"black" became detached from its negative connotations, and was reclaimed as a marker of pride: black is beautiful.[40] In 1975, a new voice emerged for the black London population; his name was David Pitt and he brought a new voice to the House of Lords. He spoke against racism and for equality in regards to all residents of Britain. With this new tone also came the opportunity for the black population to elect four Black members into Parliament.

Since the 1980s, the majority of black immigrants into the country have come directly from Africa, in particular, Nigeria and Ghana in West Africa, Uganda and Kenya in East Africa, Zimbabwe, and South Africa in Southern Africa. Nigerians and Ghanaians have been especially quick to accustom themselves to British life, with young Nigerians and Ghanaians achieving some of the best results at GCSE and A-Level, often on a par or above the performance of Caucasian pupils.[42] The rate of inter-racial marriage between British citizens born in Africa and native Britons is still fairly low, compared to those from the Caribbean. This might change over time as Africans become more part of mainstream British culture as second and third generation African communities become established.

By the end of the 20th century the number of black Londoners numbered half a million, according to the 1991 census. An increasing number of these black Londoners were London- or British-born. Even with this growing population and the first blacks elected to Parliament, many argue that there was still discrimination and a socio-economic imbalance in London among the blacks. In 1992 the number of blacks in Parliament increased to six and in 1997 they increased their numbers to nine. There are still many problems that black Londoners face; the new global and high-tech information revolution is changing the urban economy and some argue that it is driving up unemployment rates among blacks relative to non-blacks,[31] something, it is argued, that threatens to erode the progress made thus far.[31]

Street conflicts and riots

The late 1950s through to the late 1980s saw a number of mass street conflicts involving young Afro-Caribbean men and (largely white) British police officers in British cities, mostly as a result of tensions between members of local black communities and white racists.

The first major incident occurred in 1958 in Notting Hill and when roaming gangs of between 300 and 400 white youths attacked Afro-Caribbean individuals and houses across the neighbourhood, leading to a number of Afro-Caribbean men being left unconscious in the streets.[43]

During the 1970s, police forces across England began to increasingly use the Sus law, provoking a sense that young black men were being discriminated against by the police[44] The next newsworthy outbreak of street fighting occurred in 1976 at the Notting Hill Carnival when several hundred police officers and youths became involved in televised fights and scuffles, with stones thrown at police, baton charges and a number of minor injuries and arrests.[45]

The 1980 St. Pauls riot in Bristol saw fighting between local youths and police officers, resulting in numerous minor injuries, damage to property and arrests. 1981 brought further conflict with a perceived racist police force after the death of 13 black youngsters who were attending a birthday party that ended in the devastating New Cross Fire. The fire was viewed by many as a racist massacre[43] and a major political demonstration, known as the Black People's day of Action was held to protest against the attacks themselves, a perceived rise in racism, and perceived hostility and indifference from the police, politicians and media.[43] Tensions were further inflamed when, in nearby Brixton, police launched operation Swamp 81, a series of mass stop-and-searches of young black men.[43] Anger erupted when up to 500 people were involved in street fighting between the Metropolitan Police and local Afro-Caribbean community, leading to a number of cars and shops set on fire, stones thrown at police and hundreds of arrests and minor injuries. A similar pattern occurred further north in Toxteth, Liverpool, and Chapeltown, Leeds.[46] Despite the recommendations of the Scarman report,[43] relations between black youths and police did not significantly improve and a further wave of nationwide conflicts occurred in Handsworth, Birmingham, in 1985, when the local South Asian community also became involved.[44] Following the police shooting of a black grandmother Cherry Groce in Brixton, and the death of Cynthia Jarrett during a raid on her home in Tottenham, protests held at the local police stations did not end peacefully and further street battles with the police erupted,[43] later spreading to Moss Side, Manchester.[43] The street battles themselves (involving more stone-throwing, the discharge of one firearm, and several fires) led to two fatalities (in the Broadwater Farm riot) and Brixton.

In 1999, following the Macpherson Enquiry into the death of Stephen Lawrence, Sir Paul Condon, commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, accepted that his organisation was institutionally racist. Some members of the Black British community were involved in the 2001 Harehills race riot and 2005 Birmingham race riots.

In 2011, following the shooting of a black man, Mark Duggan by police in Tottenham, a protest was held at the local police station. The protest did not end peacefully, with an outbreak of fighting between local youths and police officers leading to widespread disturbances across British cities.

Early 21st century

Some analysts claimed that black people were disproportionally represented in the 2011 England riots.[47] Research suggests race relations in Britain have deteriorated since the riots and that prejudice towards ethnic minorities is on the rise.[48] Groups such as the EDL and the BNP were said to be exploiting the situation.[49] Racial tensions between blacks and Asians in Birmingham increased after the deaths of three Asian men at the hands of a black youth.[50]

In a Newsnight discussion on 12 August, historian David Starkey blamed black gangster and rap culture, saying that it had influenced youths of all races.[51] Figures showed that 46% of people brought before a courtroom for arrests related to the 2011 riots were black.[52]

Demographics

Population

In the 2001 UK Census, 565,876 people stated their ethnicity as Black Caribbean, 485,277 as Black African and 97,585 as Black Other, making a total of 1,148,738 in the census's Black or Black British category. This was equivalent to two percent of the UK population at the time.[53]

Mid-2009 estimates for England put the Black British population at 1,521,400 compared to 1,158,000 in mid-2001, an increase of 23.9% in eight years.[54]

Population distribution

Most Black Britons can be found in the large cities and metropolitan areas of the country: there are almost one million Black Britons in London. According to the 2011 census, cities and towns with large and significant Black communities are as follows (London boroughs included).[55]

| Large Black British Communities | |||

| Greater London | 1,088,600 | ||

| - Lambeth | 78,500 | ||

| - Southwark | 77,500 | ||

| - Lewisham | 75,900 | ||

| - Croydon | 73,200 | ||

| - Newham | 60,300 | ||

| - Brent | 58,600 | ||

| - Hackney | 56,800 | ||

| - Enfield | 53 700 | ||

| - Greenwich | 48,700 | ||

| - Haringey | 47,800 | ||

| - Waltham Forest | 44,800 | ||

| - Barking and Dagenham | 37,100 | ||

| - Ealing | 36,700 | ||

| - Wandsworth | 32,800 | ||

| - Barnet | 27,300 | ||

| - Islington | 26,300 | ||

| - Redbridge | 24,800 | ||

| - Hammersmith and Fulham | 21,500 | ||

| - Merton | 20,800 | ||

| - Hillingdon | 20,100 | ||

| Birmingham | 96,400 | ||

| Manchester | 43,500 | ||

| Leeds | 25,900 | ||

| Bristol | 25,700 | ||

| Nottingham | 22,200 | ||

| Leicester | 20,600 | ||

| Sheffield | 20,100 | ||

Immigration

Far-right political parties have cited concerns about uncontrolled immigration in order to gain support during elections. Parties such as the BNP have declared policies that include a halt to all non-European immigration.

Culture and community

Dialect

British Black English is a variety of the English language spoken by a large number of the Black British population of Afro-Caribbean ancestry.[56] British Black dialect is heavily influenced by Jamaican English owing to the large number of British immigrants from Jamaica, but it is also spoken by those of different ancestry.

British Black speech is also heavily influenced by social class and the regional dialect (Cockney, Mancunian, Brummie, Scouse, etc.).

However, it has also been argued that there is no such thing as "British Black English" because black Britons speak the same English as all other ethnic groups in Britain. For example, Black Britons are required to sit GCSE English language and literature exams, and middle and upper-middle class black Britons do not associate themselves with "British Black English".

Music

Black British music is a long-established and influential part of British music. Its presence in the United Kingdom stretches back to the 18th century, encompassing concert performers such as George Bridgetower and street musicians the like of Billy Waters.

In the late 1970s and 1980s, 2 Tone became popular with the British youth; especially in the West Midlands. A blend of punk, ska, and pop made it a favorite amongst both white and black audiences. Famous bands in the genre include The Selecter, The Specials, The Beat, and The Bodysnatchers.

Jungle, dubstep, drum and bass, and grime music were invented in London and involve a number of artists from primarily Caribbean communities but recently Black Africans also, most notably Ghanaian and Nigerian. Famous grime artists include Dizzee Rascal, Tinchy Stryder, Tinie Tempah, Chipmunk, Kano (rapper), Wiley, and Lethal Bizzle. It is now common to hear British MCs rapping in a strong London accent. Niche, with its origin in Sheffield and Leeds, has a much faster bassline and is often sung in a northern accent. Famous niche artists include producer T2.

Media

The black community in the UK have two leading publications. Pride Magazine is the largest monthly lifestyle magazine within the community; The Guardian stated that the magazine has dominated the black magazine market for over 15 years and is now in its 21st year. Its owner, Pride Media, also specialises in helping organisations target this fast-growing community through a range of media. The other key publication is The Voice newspaper, which targets the Caribbean diaspora and has been printed for over 20 years. The community also has a number of radio stations and cable-television channels targeting them.

Social issues

There is much controversy surrounding the politics of integrating the United Kingdom's black community, particularly concerning institutional racism and inequality present in the employment and higher education of urban black Britons.

Unemployment

According to the TUC report Black workers, jobs and poverty,[57] people from black and certain Asian groups are far more likely to be unemployed than the white population. The rate of unemployment among the white population is only 12%, but among black groups it is 16%, mixed-race 15%, Indian 7%, Pakistani 15%, and Bangladeshi 17%, Chinese 5%. The rate of poverty are and low income are twice to three times higher, of the different ethnic groups studied, Bangladeshis, Pakistanis, and Black British had the highest rates of child of over 50%.

Crime

Both racist crime and gang-related crime continues to affect black communities, so much so that the Metropolitan Police launched Operation Trident to tackle black-on-black crimes. Numerous deaths in police custody of black men has generated a general distrust of police among urban blacks in the UK.[58][59] According to the Metropolitan Police Authority in 2002–2003 of the 17 deaths in police custody, 10 were black or Asian – black convicts are have a disproportionately high rate of incarceration. The government reports[60] The overall number of racist incidents recorded by the police rose by 7% from 49,078 in 2002/3 to 52,694 in 2003/4.

The media, mostly BBC News has highlighted 'gangs' with black members and violent crimes involving black victims and perpetrators. According to a Home Office report,[60] 10% of all murder victims between 2000 and 2004 were black. Of these, 56% were murdered by other black people (with 44% of black people murdered by whites and Asians – making black people disproportionately higher victims of killing by people from other ethnicities). In addition, a Freedom of Information request made by The Daily Telegraph shows internal police data that provides a breakdown of the ethnicity of the 18,091 men and boys who police took action against for a range of offences in London in October 2009. Among those proceeded against for street crimes, 54 percent were black; for robbery, 59 percent; and for gun crimes, 67 percent.[61]

Black people, who according to government statistics[62] make up 2% of the population, are the principal suspects in 11.7% of murders, i.e., in 252 out of 2163 murders committed 2001/2, 2002/3, and 2003/4.[63] It should be noted that, judging on the basis of prison population, a substantial minority (about 35%) of black criminals in the UK are not British citizens but foreign nationals.[64] In November 2009, the Home Office published a study that showed that, once other variables had been accounted for, ethnicity was not a significant predictor of offending, anti-social behaviour or drug abuse among young people.[65]

After several high-profile investigations such as that of the murder of Stephen Lawrence, the police have been accused of racism, from both within and outside the service. Cressida Dick, head of the Metropolitan Police's anti-racism unit in 2003, remarked that it was "difficult to imagine a situation where we will say we are no longer institutionally racist".[66] Black people were seven times more likely to be stopped and searched by police compared to white people, according to the Home Office, A separate study said blacks were more than nine times more likely to be searched.[67]

Notable black Britons

Well-known black Britons living before the 20th century include the Chartist William Cuffay; William Davidson, executed as a Cato Street conspirator; Olaudah Equiano (also called Gustavus Vassa), a former slave who bought his freedom, moved to England, and settled in Soham, Cambridgeshire, where he married and wrote an autobiography, dying in 1797; Ukawsaw Gronniosaw, pioneer of the slave narrative; and Ignatius Sancho, a grocer who also acquired a reputation as a man of letters. In 2004, a poll found that people considered the Crimean War heroine Mary Seacole to be the greatest Black Briton.[68] Seacole was born in Jamaica in 1805 to a white father and black mother.[69] A statue of her is planned for the grounds of St. Thomas' Hospital in London.[68]

More recently, a large number of Black British people have achieved prominence in public life. An example from television is reporter and newsreader Sir Trevor McDonald, born in Trinidad, who was knighted in 1999. McDonald is now seen as a part of the broadcasting establishment. His clear, confident delivery and serious attitude have made him one of British television's most trusted presenters, winning more awards than any other British broadcaster. Also notable is Moira Stuart, OBE, the first female newsreader of African-Caribbean heritage on British television. Other examples from television are entertainer Lenny Henry and chef Ainsley Harriott.

In art and film, Steve McQueen won the Turner Prize in 1999, he has since directed his first feature Hunger (2008). The film earned him the Caméra d'Or at the 2008 Cannes Film Festival.

Michael Fuller, after a career in the Metropolitan Police, has been Chief Constable of Kent since 2004. He is the son of Jamaican immigrants who came to the United Kingdom in the 1950s. Fuller was brought up in Sussex, where his interest in the police force was encouraged by an officer attached to his school. He is a graduate in social psychology.[70]

In business, Damon Buffini heads Permira, one of the world's largest private equity firms. He topped the 2007 "power list" as the most powerful Black male in the United Kingdom by New Nation magazine and was recently appointed to Prime Minister Gordon Brown's business advisory panel.

René Carayol is a broadcaster, broadsheet columnist, business and leadership speaker and author, best known for presenting the BBC series Did They Pay Off Their Mortgage in Two Years?. He has also served as an executive main board director for blue-chip companies as well as the public sector.

Wol Kolade is council member and Chairman of the BVCA (British Venture Capital Association) and a Governor and council member of the London School of Economics and Political Science, chairing its Audit Committee.

Adam Afriyie is a politician, and Conservative Member of Parliament for Windsor. He is also the founding director of Connect Support Services, an IT services company pioneering fixed-price support. He was also Chairman of DeHavilland Information Services plc, a news and information services company, and was a regional finalist in the 2003 Ernst and Young Entrepreneur of the year awards.

Alexander Amosu is an entrepreneur and one of the first people in the UK to create high-end customised mobile phones in gold, white gold, and various colours of diamonds, selling to wealthy clients worldwide.

Wilfred Emmanuel-Jones is a businessman, farmer and founder of the popular Black Farmer range of food products. He stood, unsuccessfully, as Conservative Party candidate for the Chippenham constituency in the 2010 general election.

In 2005 soldier Johnson Beharry, born in Grenada of mixed Black African and East Indian roots, became the first man to win the Victoria Cross, the United Kingdom's foremost military award for bravery, since the Falklands War of 1982. He was awarded the medal for service in Iraq in 2004.

In sport, prominent examples of success include boxing champion Frank Bruno, whose career highlight was winning the WBC world heavyweight championship in 1995. Altogether, he has won 40 of his 45 contests. He is also well known for acting in pantomime. Lennox Lewis, born in east London, is another successful Black British boxer and former undisputed heavyweight champion of the world.

There are many notable black British footballers, some of whom have played for England, including Paul Ince, Sol Campbell, John Barnes, Rio Ferdinand, Viv Anderson, Des Walker, Ashley Cole, Ian Wright and David James.

Lewis Hamilton, who is mixed-race, has created a major impact in the world of Formula One racing, with his most notable achievement being the winner (and first Black person) of the 2008 Formula One World Championship.

Kelly Holmes, who won two gold medals in the 2004 Athens Olympics, is also mixed-race: her black father was born in Jamaica, while her white mother is English.

People of black ancestry such as Bernie Grant, Baroness Amos and Diane Abbott, as well as Oona King and Paul Boateng who are of mixed race, have made significant contributions to politics and trade unionism. Boateng became the UK's first black biracial cabinet minister in 2002 when he was appointed as Chief Secretary to the Treasury. Abbott became the first black woman Member of Parliament when she was elected to the House of Commons in the 1987 general election.

Bill Morris was elected general secretary of the Transport and General Workers' Union in 1992. He was knighted in 2003, and in 2006 he took a seat in the House of Lords as a working life peer, Baron Morris of Handsworth.

The Trinidadian cricketer Learie Constantine was ennobled in 1969 and took the title Baron Constantine of Maraval in Trinidad and Nelson in the County Palatine of Lancaster.

David Pitt became a member of the House of Lords when he became a Life Peer for the Labour Party in 1975. He was also President of the British Medical Association. The first black Conservative Peer was John Taylor, Baron Taylor of Warwick.[71] Valerie Amos became the first black woman cabinet minister and the first black woman to become leader of the House of Lords.

Numerous Black British actors have become successful in US television, such as Adewale Akinnuoye-Agbaje, Idris Elba, Lennie James, Marsha Thomason, and Marianne Jean-Baptiste. Black British actors are also increasingly found starring in major Hollywood movies, notable examples include Adrian Lester, Ashley Walters, Chiwetel Ejiofor, Colin Salmon, David Harewood, Eamonn Walker, Hugh Quarshie, Naomie Harris, Sophie Okonedo, and Thandie Newton.

See also

References

- ^ a b "Ethnicity and National Identity in England and Wales 2011". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ^ a b Key Census 2001 Statistics for Settlements and Localities Scotland, Retrieved 27 December 2012.

- ^ a b 2011 Census: Ethnic group, unitary authorities in Wales, Accessed 27 December 2012

- ^ a b Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency – Ethnic Group: KS201NI (administrative geographies) Retrieved 27 December 2012.

- ^ "Ethnic group: By religion, April 2001, Great Britain". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 16 October 2010.

- ^ Gadsby, Meredith (2006). Sucking Salt: Caribbean Women Writers, Migration, and Survival. University of Missouri Press. pp. 76–77.

- ^ Glossary of terms relating to ethnicity and race: for reflection and debate R Bhopal. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. Retrieved 6 October 2006.

- ^ Steele, John. "Blair: Black community must oppose gangs". The Daily Telegraph. 12 April 2007. Retrieved 27 September 2010.

- ^ "Census 2011 mapped and charted: England & Wales in religion, immigration and race". Guardian. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- ^ Southall Black Sisters website

- ^ The Guardian "What the migrant saw" by Jatinder Verma, founder in 1977 of Tara Arts, the first Asian theatre company in Britain – "Everywhere my friends and I looked, it seemed black people, as we identified ourselves, were victims of Ronaldo Brilha Muito white oppression."

- ^ What is meant by Black and Asian? "In the 1970s Black was used as a political term to encompass many groups who shared a common experience of oppression – this could include Asian but also Irish, for example"

- ^ "The term Black and Asian – a Short History" "In the late 1960's through to the mid-1980s, we progressives called ourselves Black. This was not only because the word was reclaimed as a positive, but we also knew that we shared a common experience of racism because of our skin colour."

- ^ "New Black Arts Alliance – Welcome". Blackartists.org.uk. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ The Black Arts Alliance encourages "a coming together of Black people from Africa, Asia and the Caribbean because our histories have parallels of oppression"

- ^ Their website intro states "Black Arts Alliance is 21 years old. Formed in 1985 it is the longest surviving network of Black artists representing the arts and culture drawn from ancestral heritages of South Asia, Africa, South America, and the Caribbean and, in more recent times, due to global conflict, our newly arrived compatriots known collectively as refugees." the Black Arts Alliance

- ^ National Black Police Association states that their "emphasis is on the common experience and determination of the people of African, African-Caribbean, and Asian origin to oppose the effects of racism."

- ^ Census classifications

- ^ "Multiculturalism the Wembley Way". BBC News. 8 September 2005. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ The Map Room: Africa: Sierra Leone. British Empire. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Exhibitions & Learning online | Black presence | Work and community. The National Archives. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Bird, Steve (27 February 2010). "Analysis of Roman grave reveals that York was a multicultural society". The Times. Retrieved 13 September 2011.

- ^ a b John Blanke-A Trumpeter in the court of King Henry VIII. Blackpresence. 12 March 2009. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ a b Wood, Michael (2003), In Search of Shakespeare, BBC Publications.

- ^ a b c Bartels, Emily C. (2006). "Too Many Blackamoors: Deportation, Discrimination, and Elizabeth I" (PDF). Studies in English Literature. 46 (2): 305–322. doi:10.1353/sel.2006.0012.

- ^ Banton, Michael (1955), The Coloured Quarter. Jonathan Cape. London.

- ^ Shyllon, Folarin. "The Black Presence and Experience in Britain: An Analytical Overview", in Gundara and Duffield, eds. (1992). Essays on the History of Blacks in Britain. Avebury, Aldershot. [1].

- ^ a b c d Costello, Ray (2001). Black Liverpool: The Early History of Britain's Oldest Black Community 1730–1918. Liverpool: Picton Press. ISBN 1-873245-07-6. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ^ McIntyre-Brown, Arabella (2001). Liverpool: The First 1,000 Years. Liverpool: Garlic Press. p. 57. ISBN 1-904099-00-9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Gerzina, Gretchen (1995). Black London: Life before Emancipation. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press. p. 5. ISBN 0-8135-2259-5.

- ^ a b c d File, Nigel and Chris Power (1981), Black Settlers in Britain 1555–1958. Heinnemann Educational. Chronicleworld's Archives

- ^ The Capital's history uncovered

- ^ Geoffrey Bell, The other Eastenders: Kamal Chunchie and West Ham's early black community (Stratford: Eastside Community Heritage, 2002)

- ^ 100 Great Black Britons

- ^ A. H. Saxon, The Life and Art of Andrew Ducrow, Archon Books, 1978.

- ^ Tyne Roots

- ^ 'Liverpool's Black Population During World War II', Black and Asian Studies Association Newsletter No. 20, January 1998, p. 6.

- ^ 'Liverpool's Black Population During World War II', Black and Asian Studies Association Newsletter No. 20, January 1998, p. 10.

- ^ Rose, Sonya (2001). "Race, empire and British wartime national identity, 1939–45". Historical Research. 74 (184): 224. doi:10.1111/1468-2281.00125.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Procter, James. Writing Black Britain 1948–1998. Manchester.

- ^ icons: a portrait of England: SS Empire Windrush

- ^ Ethnicity and Education: The Evidence on Minority Ethnic Pupils aged 5–16, The Department for Education and Skills 2006

- ^ a b c d e f g Dabydeen, Gilmore, Jones (eds), The Oxford Companion to Black British History. OUP, 2010.

- ^ a b Trevor Phillips, Mike Phillips, Windrush: The Irresistible Rise of Multi-Racial Britain, HarperCollins, 2009.

- ^ Fryer, Peter, Staying Power: The History of Black People in Britain since 1504. London: Pluto Press, 1984.

- ^ "Life and times in Chapeltown", Yorkshire post, 1 January 2003.

- ^ "A reckoning". The Economist. 3 September 2011. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- ^ Taylor, Matthew (5 September 2011). "British public 'are more prejudiced against minorities after riots'". The Guardian.

- ^ Williams, David; Kisiel, Ryan; Camber, Rebecca (11 August 2011). "Right-wing extremists hijacking the vigilante patrols protecting against looters, warn police". Daily Mail. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- ^ Kerrins, Suzanne (24 September 2011). "Sir Ian Botham: bring in corporal punishment and ban reality TV to save today's youth". The Daily Telegraph.

- ^ "'The whites have become black' says David Starkey". BBC. 12 August 2011. Retrieved 15 August 2011.

- ^ "Gangs Had No 'Pivotal Role' In English Riots". Sky News. 24 October 2011. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- ^ "Population size: 7.9% from a minority ethnic group". Office for National Statistics. 13 February 2003. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- ^ "Population estimates by ethnic group: 2009". Office for National Statistics. May 2011. Retrieved 19 May 2011.

- ^ 2011 Census: Ethnic group local authorities in England and Wales, Accessed 28 February 2013.

- ^ Sebba, Mark (2007). "Caribbean Creoles and Black English", chap. 16 of Language in the British Isles, David Britain (ed.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-79488-9.

- ^ "Trades Union Congress – Social Issues". Tuc.org.uk. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Gilligan, Andrew. "Tottenham and Broadwater Farm: A Tale of Two Riots". The Daily Telegraph. 7 August 2011. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- ^ "Trusting the Young". BBC News. 17 March 2009. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- ^ a b Statistics on Race and the Criminal Justice System – 2004 A Home Office publication under section 95 of the Criminal Justice Act 1991. (PDF) . Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ "Violent Inner-City Crime, the Figures, and a Question of Race". The Daily Telegraph 26 June 2010. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Population Size 7.9% from a minority ethnic group, National Statistics Bureau

- ^ Table 3.6 of Home Office publication "Statistics on Race and the Criminal Justice System 2004".

- ^ Chapter 9, tables 9.1 – 9.4, of Home Office publication "Statistics on Race and the Criminal Justice System 2004".

- ^ Hales, Jon; Nevill, Camilla; Pudney, Steve; Tipping, Sarah (November 2009). "Longitudinal analysis of the Offending, Crime and Justice Survey 2003–06" (PDF). Research Report. 19. London: Home Office: 23. Retrieved 7 October 2010.

- ^ "Metropolitan police still institutionally racist". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Akwagyiram, Alexis (17 January 2012). "Stop and Search Use and Alternative Police Tactics". BBC News. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- ^ a b "Seacole sculpture design revealed". BBC News. 18 June 2009. Retrieved 19 June 2009.

- ^ "Historical figures: Mary Seacole (1805–1881)". BBC History. Retrieved 19 June 2009.

- ^ Alumni and friends | Notable Alumni | Michael Fuller

- ^ "Ex-Tory Peer Lord Taylor Jailed for Expenses Fraud. BBC News. 31 May 2011.

External links

- The Black Presence in Britain – Black British History

- The Scarman Report into the Brixton Riots of 1981.

- The Macpherson Report into the death of Stephen Lawrence.

- Brixton Overcoat, ISBN 978-0-9552841-0-6

- Reassessing what we collect website – The African Community in London History of African London with objects and images

- Reassessing what we collect website – Caribbean London History of Caribbean London with objects and images

- Birmingham Black Oral History Project

- "The Contestation of Britishness" by Ronald Elly Wanda

Template:Ethnic, linguistic and cultural minorities in the European Union

Cite error: There are <ref group=note> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=note}} template (see the help page).