Michael DeBakey

Michael DeBakey | |

|---|---|

Michael Ellis DeBakey | |

| Born | Michel Dabaghi September 7, 1908 |

| Died | July 11, 2008 (aged 99) |

| Education | Tulane University |

| Occupation | Cardiovascular surgeon |

| Medical career | |

| Profession | Surgeon |

| Institutions | Tulane University |

| Research | |

| Awards |

|

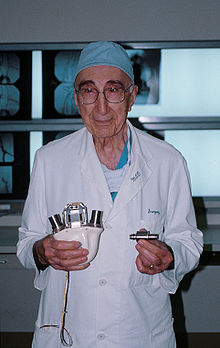

Michael Ellis DeBakey (7 September 1908 – 11 July 2008) was a Lebanese-American cardiovascular surgeon, scientist, and medical educator, who became the chancellor emeritus of Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas, director of The Methodist DeBakey Heart & Vascular Center, and senior attending surgeon of The Methodist Hospital in Houston, with a career spanning 75 years.

Born to Lebanese Christian immigrants, DeBakey was inspired towards a career in medicine by the physicians he met at his father's drug store and he simultaneously learned sewing skills from his mother. He subsequently attended Tulane University for his premedical course and Tulane University School of Medicine to study medicine, where he developed a version of the roller pump, which he initially used to transfuse blood directly from person to person and which later became a component of the heart–lung machine.

Following early surgical training at Charity Hospital, he was encouraged to complete his surgical fellowships in Europe, before returning to Tulane University in 1937. During the Second World War, he helped develop the Mobile Army Surgical Hospital (MASH) units and later helped establish the Veteran's Administration Medical Center Research System.

DeBakey's surgical innovations included coronary bypass operations, carotid endarterectomy, artificial hearts and ventricular assist devices. He used Dacron grafts to replace or repair blood vessels and pioneered surgical repairs of aortic aneurysms, an operation he himself had performed on him at the age of 97.

DeBakey received a number of awards in his lifetime including the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the National Medal of Science and the Congressional Gold Medal. In addition, a number of institutions bear his name.

Early life and education

Michael DeBakey was born (as Michel Dabaghi)[1] in Lake Charles, Louisiana on 7 September 1908, to Shaker Morris and Raheeja Debaghi. The name was later anglicized to DeBakey.[2][3] His parents were Lebanese Christian immigrants, spoke French and fled oppression from the Ottomans to settle in Cajun Country where French was spoken.[4]

His father was a businessman involved in establishing rice farms, drug stores and estate agencies and DeBakey helped out with keeping the books.[1] He was inspired to become a doctor after meeting local physicians while he worked at his father's pharmacy.[5] DeBakey attended school at Lake Charles[5] and was the eldest of five children, having three sisters and one brother,[6] Ernest (Ernie), who would later become a thoracic surgeon. His sisters Lois and Selma, also pursued careers in science. There was another sister, Selena.[3]

As a child, he learnt to play the saxophone and was taught by his mother, who was a seamstress, on how to sew, crochet, knit[5] and tat.[6] He could sew his own shirt by the age of 10. He also became intrigued with the Encyclopædia Britannica[1] and is said by colleagues to have read it from beginning to end. He learnt French and German and participated in the Boy Scout troop. In addition, he won awards for the vegetables he had grown in his garden.[3]

Medical school

At Tulane University, DeBakey took two years to complete his premedical course,[3] gaining a BSc in 1929.[1] A year earlier, he had already been granted admission to study medicine at Tulane University School of Medicine, where he also took up part-time work in surgical research.[3]

During his final year in medical school at Tulane University,[6] at age 23, and prior to established blood banks, DeBakey adapted old pumps and rubber tubing and developed a version of the roller pump. He then used it to transfuse blood directly and continuously from person to person and this later became a component of the heart–lung machine.[5][7]

In 1932, he received an M.D. degree from Tulane University School of Medicine.[3]

Postgraduate surgical training

Between 1933 and 1935, DeBakey remained in New Orleans to complete his internship and residency in surgery at Charity Hospital, and in 1935, he received a MS for his research on stomach ulcers. As was the trend for ambitious training surgeons at the time and as his mentors Rudolph Matas and Alton Ochsner had done before him, DeBakey was encouraged to complete his surgical fellowships at the University of Strasbourg, France, under Professor René Leriche, and at the University of Heidelberg, Germany, under Professor Martin Kirschner.[3]

Returning to Tulane Medical School, he served on the surgical faculty from 1937 to 1948.[3]

With his mentor, Alton Ochsner, he postulated in 1939 a strong link between smoking and carcinoma of the lung, a hypothesis which other researchers supported as well.[3]

Second World War

During the Second World War, DeBakey served in the U.S. Army as Director of the Surgical Consultants’ Division in the Surgeon General’s Office. He later held rank of Colonel in the United States Army (Reserve). In 1945, he was awarded the Legion of Merit Award.[8]

DeBakey helped develop the Mobile Army Surgical Hospital (MASH) units,[5] thereby promoting wartime medicine by supporting the stationing of doctors closer to the front lines, which improved the survival rate of wounded soldiers in the Korean War.[5]

He later helped establish the Veteran's Administration Medical Center Research System.[2][5] After the war, DeBakey returned to Tulane.[8]

Post war surgical career

He joined the faculty of Baylor University College of Medicine (now known as the Baylor College of Medicine) in 1948, serving as Chairman of the Department of Surgery until 1993. DeBakey was president of the college from 1969 to 1979, served as Chancellor from 1979 to January 1996; he was then named Chancellor Emeritus. He was also Olga Keith Wiess and Distinguished Service Professor in the Michael E. DeBakey Department of Surgery at Baylor College of Medicine and Director of the DeBakey Heart Center for research and public education at Baylor College of Medicine and The Methodist Hospital.[citation needed]

He was a member of the medical advisory committee of the Hoover Commission and was chairman of the President's Commission on Heart Disease, Cancer and Stroke during the Johnson Administration. He worked in numerous capacities to improve national and international standards of health care. Among his numerous consultative appointments was a three-year membership on the National Advisory Heart and Lung Council of the National Institutes of Health.[citation needed]

DeBakey hired surgeon Denton Cooley to Baylor College of Medicine in 1951. They collaborated and frequently worked together until Cooley's resignation from his faculty position at the college in 1969.[citation needed]

Vascular surgery

In the 1950s, DeBakey's observations and classification of atherosclerotic blood vessels permitted innovations in the treatments of vascular disease.[8] His pursuit of the ideal material to make grafts led him to the department store that had run out of nylon and he therefore settled with the available Dacron and bought a yard of the material. Using his wife’s sewing machine, he produced the first artificial arterial Dacron grafts to replace or repair blood vessels.[2][5] He subsequently collaborated with a research associate from the Philadelphia College of Textiles and Science and created a knitting machine for making grafts.[8]

DeBakey performed the first successful carotid endarterectomy in 1953. A year later, he pioneered techniques in grafts for the various parts of the aorta.[8]

DeBakey was among the earlier surgeons to perform coronary artery bypass surgery. A pioneer in the development of an artificial heart, DeBakey was among the first to use an external heart pump successfully in a patient – a left ventricular bypass pump.[3]

In 1958, to counteract narrowing of an artery caused by an endarterectomy,[2] DeBakey performed the first successful patch-graft angioplasty. This procedure involved patching the slit in the artery from an endarterectomy with a Dacron or vein graft. The patch widened the artery so that when it closed, the channel of the artery returned to normal size.[citation needed]

Film

In the 1960s, DeBakey and his team of surgeons were among the early instances of surgeries on film.[7]

Views on animal research

DeBakey founded and chaired the Foundation for Biomedical Research (FBR), whose goal is to promote public understanding and support for animal research. DeBakey made wide use of animals in his research.[9] He antagonized animal rights and animal welfare advocates who oppose the use of animals in the development of medical treatment for humans when he claimed that the "future of biomedical research; and ultimately human health" would be compromised if shelters stopped turning over surplus animals for medical research.[10] Responding to the need for animal research, DeBakey stated that "These scientists, veterinarians, physicians, surgeons and others who do research in animal labs are as much concerned about the care of the animals as anyone can be. Their respect for the dignity of life and compassion for the sick and disabled, in fact, is what motivated them to search for ways of relieving the pain and suffering caused by diseases."[11]

Later surgical career

DeBakey continued to practice medicine until his death in 2008 at the age of 99. His contributions to the field of medicine spanned the better part of 75 years. DeBakey operated on more than 60,000 patients, including several heads of state.[12] DeBakey and a team of American cardiothoracic surgeons, including George Noon, supervised quintuple bypass surgery performed by Russian surgeons on Russian President Boris Yeltsin in 1996.[13]

Health issues

On December 31, 2005, at age 97, DeBakey suffered an aortic dissection. Years prior, DeBakey had pioneered the surgical treatment of this condition, creating what is now known as the DeBakey Procedure.[6] He was hospitalized at The Methodist Hospital in Houston, Texas.[citation needed]

DeBakey initially resisted the surgical option, but as his health deteriorated and DeBakey became unresponsive, the surgical team opted to proceed with surgical intervention. In a controversial decision, Houston Methodist Hospital Ethics Committee approved the operation; on February 9–10, he became the oldest patient ever to undergo the surgery for which he was responsible. The operation lasted seven hours. After a complicated post-operative course that required eight months in the hospital at a cost of over one million dollars, DeBakey was released in September 2006 and returned to good health.[13]

Selected honours and awards

DeBakey became a member of numerous learned societies, gained 36 honorary degrees and was the recipient of hundreds of awards.[8]

He received the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1969. In 1987, President Ronald Reagan awarded him the National Medal of Science.[14] He was a Health Care Hall of Famer, a Lasker Luminary, and a recipient of The United Nations Lifetime Achievement Award and the Presidential Medal of Freedom with Distinction. He was given the Lifetime Achievement Award of the Foundation for Biomedical Research and in 2000 was cited as a "Living Legend" by the Library of Congress. On April 23, 2008, he received the Congressional Gold Medal from President George W. Bush, Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi, and Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid.[15][16][17]

DeBakey's major awards include;[3][8][18]

- U.S. Army Legion of Merit (1945)

- American Medical Association Hektoen Gold Medal (1954 and 1970)

- Rudolph Matas Award in Vascular Surgery (1954)

- International Society of Surgery Distinguished Service Award (1958)

- Leriche Award (1959)

- American Medical Association Distinguished Service Award (1959)[3]

- Albert Lasker Award for Clinical Medical Research (1963)

- American Academy of Achievement's Golden Plate Award (1967)[19]

- Prix International Dag Hammarskjold Great Collar with Golden Medal (1967)

- American Heart Association Gold Heart Award (1968)

- Medal of Freedom with Distinction (1969)

- Eleanor Roosevelt Humanitarian Award (1969)

- Yugoslavian Presidential Banner and Sash (1971)

- Union of Soviet Socialist Republics Academy of Sciences 50th Anniversary Jubilee Medal (1973)

- Independence of Jordan Medal (1980)

- American Surgical Association Distinguished Service Award (1981)

- National Medal of Science ( 1987)

- Merit Order of the Republic of Egypt (1980)

- International Society of Surgery Distinguished Service Award (1981)

- National Medal of Science (1987)

- Theodore E. Cummings Memorial Prize for Outstanding Contributions in Cardiovascular Disease (1987)

- International Platform Association George Crile Award as The Trailblazer in Open Heart Surgery (1988)

- Thomas Alva Edison Foundation Award (1988)

Others awards include;

- Honorary Doctorate of Science from Universidad Francisco Marroquín[20] (1989)

- Special Award for Space Technology Utilization (1997)[21]

- MUSC Lindbergh-Carrel Prize (2002)[22]

- Lomonosov Large Gold Medal, Russian Academy of Sciences (2003)[23]

- The Denton A. Cooley Leadership Award (January 21, 2009)[24]

Personal and family

DeBakey married Diana Cooper after returning from Europe in 1937 and they had four sons; Michael and Dennis, Ernest and Barry.[3] However, Diana died in 1972 and he later married German actress Katrin Fehlhaber, with whom he had a daughter Olga-Katarina.[5]

DeBakey has been described as a "tough taskmaster" by colleagues and trainees.[25] Jeremy R. Morton, a former trainee of DeBakey described how “he could be sweet as dripping honey when it came to patients and medical students, but could be brutal with surgical residents."[5]

Death and legacy

On July 11, 2008, DeBakey died at The Methodist Hospital in Houston, two months before his 100th birthday; the cause of death remained unspecified.[6][26] After lying in repose in Houston's City Hall, being the first ever to do so,[27] DeBakey received a memorial service at the Co-Cathedral of the Sacred Heart on July 16, 2008[28] Dr. DeBakey was granted ground burial in Arlington National Cemetery by the Secretary of the Army.[29] On January 21, 2009, DeBakey became the first posthumous recipient of The Denton A. Cooley Leadership Award.[30]

Michael E. DeBakey International Surgical Society

In 1976, DeBakey's trainees students founded the Michael E. DeBakey International Cardiovascular Surgical Society, which later changed its name to the Michael E. DeBakey International Surgical Society. Every two years, the Michael E. DeBakey Award is given.[8][31]

Michael E. DeBakey Library and Museum

In early 2008, Dr. DeBakey attended the groundbreaking for the new Michael E. DeBakey Library and Museum at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas,[32] honoring his life, work, and dedication to care and teaching. The museum officially opened on Friday, May 14, 2010.[33]

DeBakey Medical Foundation

In honor of DeBakey, the DeBakey Medical Foundation, in conjunction with Baylor College of Medicine, annually selects recipients of the Michael E. DeBakey, M.D., Excellence in Research Awards.[34] The awards recognize faculty who have published outstanding scientific research contributions to clinical or basic biomedical research. The awards are funded by the DeBakey Medical Foundation and have funded researchers from the Center for Cell and Gene Therapy at Texas Children's Cancer Center.[35]

The Foundation helped to establish the Michael E. DeBakey, Selma DeBakey and Lois DeBakey Endowed Scholarship Fund in Medical Humanities at Baylor University. The scholarship designates award recipients as "DeBakey Scholars" in recognition of the legacy of the DeBakey family.[36]

Other DeBakey institutes

The DeBakey High School for Health Professions, the Methodist DeBakey Heart & Vascular Center and the Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Houston at the Texas Medical Center in Houston are named after him. He had a role in establishing the Michael E. DeBakey Heart Institute at the Hays Medical Center in Kansas. Several atraumatic vascular surgical clamps and forceps that he introduced also bear his name.[37] DeBakey founded the Michael E. DeBakey Institute at Texas A&M College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences as a collaboration between Texas A&M, the Baylor College of Medicine and the UT Health Science Center at Houston to further cardiovascular research.[citation needed]

Selected publications

DeBakey's writings are reflected in his authorship or co-authorship in more than 1,300 published medical articles, chapters and books on various aspects of surgery, medicine, health, medical research and medical education, as well as ethical, socio-economic and philosophic discussion in these fields. In addition to his scholarly writings, he co-authored popular works including The Living Heart, The Living Heart Shopper's Guide and The Living Heart Guide to Eating Out. Some of the references:

- " A Simple Continuous Flow Blood Transfusion Instrument", New Orleans Medical and Surgical Journal (1934)

- The living heart. Co-authored with Antonio M Gotto and Mediziner Italien, Charter Books (1977), ISBN 9780441485505

- The Living heart diet, New York: Raven Press (1984), ISBN 9780890046722

- New living heart. Co-authored with Antonio M Gotto, Holbrook (1997), ISBN 9781558507227

- The Living Heart in the 21st Century. Co-authored with Antonio Gotto and George P. Noon, Prometheus (2012), ISBN 9781616145644

DeBakey worked on his first book with Gilbert Wheeler Beebe after the Second World War:

- Battle Casualties Incidence, Mortality, and Logistic Considerations, co-authored with G. W. Beebe, Springfield, Ill. : Charles C. Thomas (1952)

References

- ^ a b c d Caroline Richmond (14 July 2008). "Michael DeBakey: Cardiovascular surgeon whose innovations revolutionised the treatment of heart patients". The Independent.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b c d Patricia Sullivan (13 July 2008). "Michael DeBakey – cardiac surgery pioneer who saved thousands in his 70-year career". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "The Michael E. DeBakey Papers: Biographical Information". profiles.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- ^ "Michael E. DeBakey, M.D." Academy of Achievement. Retrieved 5 March 2019.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j Altman, Lawrence K. (13 July 2008). "Michael DeBakey, Rebuilder of Hearts, Dies at 99". The New York Times. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Ackerman, Todd; Eric Berger (2008-07-12). "Dr. Michael DeBakey: 1908-2008". Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on January 30, 2010. Retrieved September 24, 2018.

- ^ a b "DeBakey Surgical Innovations". Baylor College of Medicine. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=requires|archive-url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|deadurl=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h Gotto, Antonio M. (11 April 1991). "Profiles in Cardiology; Michael DeBakey". Clinical Cardiology. 14: 1007–1010.

- ^ Lefrak, EA; Stevens, PM; Nicotra, MB; Viroslav, J; Noon, GP; DeBakey, ME (January 1973). "An experimental model for evaluating extracorporeal membrane oxygenator support in acute respiratory failure". The American surgeon. 39 (1): 20–30. doi:10.1016/0002-9149(71)90077-4. PMID 4686133.

- ^ Hecht, Liz. "When will it end? Citizens for Alternatives to Animal Labs" (PDF). Banpondseizure.org. p. 99. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ "Animal Research Saves Lives". Mofed.org. 2002-04-07. Archived from the original on 2016-12-11. Retrieved 2016-11-20.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Michael DeBakey, pioneer of heart procedures, dead at 99". Associated Press. July 12, 2008. Archived from the original on September 17, 2008. Retrieved 2016-11-20.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Altman, Lawrence K. (25 December 2006). "The Man on the Table Was 97, but He Devised the Surgery". The New York Times. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- ^ "The President's National Medal of Science: Recipient Details | NSF - National Science Foundation". Nsf.gov. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- ^ "Heart surgeon DeBakey receives high honor". KTRK. 2008-04-30.

- ^ "Houston's DeBakey gets congressional medal in D.C." Houston Chronicle.

- ^ "United States Senator Kay Bailey Hutchison". web.archive.org. 21 October 2007. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ "Awards". Baylor College of Medicine. Retrieved 13 March 2019.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ "Michael E. DeBakey, M.D. Biography and Interview". www.achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement.

- ^ "Universidad Francisco Marroquín". Ufm.edu (in Spanish). 2014-08-13. Retrieved 2016-11-20.

- ^ Marianne Dyson (1997). "1997 Space Technology Utilization Award". Rnasa.org. Retrieved 2011-04-19.

- ^ Lindbergh-Carrel Prize Archived February 7, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Selected Major Awards and Honors - In Memoriam, Michael E. DeBakey, M.D. - Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas". 25 November 2008. Archived from the original on 25 November 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Denton A. Cooley, M.D." Academy of Achievement. Retrieved 5 March 2019.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ "Transcript: DeBakey Video Profile". www.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ "Baylor, Methodist mourn death of Dr. Michael E. DeBakey". Baylor College of Medicine.

- ^ Ackerman, Todd (2008-07-15). "Houstonians view DeBakey's casket at City Hall - Houston Chronicle". Chron.com. Retrieved 2016-11-20.

- ^ "Dr. DeBakey is being remembered in a way officials say has never happened | abc13.com". Abclocal.go.com. 2008-07-15. Retrieved 2016-11-20.

- ^ "U.S. Congressman John Culberson : 7th District of Texas : Blog Posting Detail". web.archive.org. 2008-08-01. Retrieved 2019-03-04.

- ^ "News of Note 2009-02 - Remembering a Legend - DACLA". web.archive.org. 2010-12-01. Retrieved 2019-03-04.

- ^ "MEDISS |". Retrieved 11 March 2019.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ Museum History (2013-08-08). "Museum History | Baylor College of Medicine | Houston, Texas". Bcm.edu. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2016-11-20.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Todd Ackerman, Houston Chronicle (2010-05-14). "Baylor honors pioneer DeBakey with library, museum - Houston Chronicle". Chron.com. Retrieved 2016-11-20.

- ^ "Index - DeBakey Excellence in Research Awards - Baylor College of Med…". 7 September 2013. Archived from the original on 7 September 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Texas Children's Cancer and Hematology Centers Dr. Malcolm Brenner an…". 7 September 2013. Archived from the original on 7 September 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Fogleman, L. DeBakey Medical Foundation Supports Endowe d Scholarship Fund for Baylor University Medical Humanities Students. Baylor Media Communications. 14 July 2009.

- ^ Ailawadi, Gorav; Nagji, Alykhan (2010-05-01). "The Legends Behind Cardiothoracic Surgical Instruments". The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 89 (5). doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.11.019. Retrieved 2019-04-25.

External links

- Video: A Dying King: The Shah of Iran

- DeBakey Department of Surgery at Baylor College of Medicine

- Methodist DeBakey Heart Center at The Methodist Hospital

- Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center

- Michael E. DeBakey International Surgical Society

- DeBakey Institute for Comparative Cardiovascular Science and Biomedical Devices at Texas A&M University

- DeBakey Cell Lab at The Health Museum

- Lasker Luminary Dr. Michael DeBakey

- In Moscow in 1996, a Doctor's Visit Changed History – The New York Times

- Michael DeBakey at Find a Grave

- The Michael E. DeBakey Papers – Profiles in Science, National Library of Medicine

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- 1908 births

- 2008 deaths

- Lebanese cardiac surgeons

- American cardiac surgeons

- American medical researchers

- American Maronites

- Congressional Gold Medal recipients

- Baylor College of Medicine physicians and researchers

- Middle Eastern Christians

- American people of Maronite descent

- United States Army Medical Corps officers

- American army personnel of World War II

- Tulane University alumni

- American people of Lebanese descent

- People from Lake Charles, Louisiana

- People from Houston

- Diseases of the aorta

- National Medal of Science laureates

- Recipients of the Lomonosov Gold Medal

- Heidelberg University alumni

- University of Strasbourg alumni

- American Surgical Association members

- Recipients of the Legion of Merit

- Burials at Arlington National Cemetery

- Tulane University School of Medicine alumni

- Recipients of the Lasker-DeBakey Clinical Medical Research Award

- Physicians from Louisiana

- Physicians from Texas

- Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients

- American people of Arab descent

- History of surgery