Taiping Rebellion

| Taiping Rebellion | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

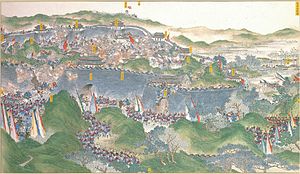

An 1884 painting of The Battle of Anqing (1861) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Later stages: |

Co-belligerents: Nian rebels Red Turban rebels Small Swords Society | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 3,400,000+[2] | 2,000,000[3] | ||||||

| 10,000,000 (all combatants)[4] | |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 145,000 | 243,000 | ||||||

| Total dead: 20–30 million dead (best estimate)[5] | |||||||

| Taiping Rebellion | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 太平天國運動 | ||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 太平天国运动 | ||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "Taiping [Great Peace] Heavenly Kingdom Movement" | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

The Taiping Rebellion, which is also known as the Taiping Civil War or the Taiping Revolution,[6] was a massive rebellion or civil war that was waged in China from 1850 to 1864 between the established Manchu-led Qing dynasty and the Hakka-led Taiping Heavenly Kingdom.

Led by Hong Xiuquan, the self-proclaimed brother of Jesus Christ, the goals of the Taipings were religious, nationalist, and political in nature; they sought the conversion of the Chinese people to the Taiping's syncretic version of Christianity, the overthrow of the ruling Manchus, and a wholesale transformation and reformation of the state.[7][8] Rather than simply supplanting the ruling class, the Taipings sought to upend the moral and social order of China.[9] To that end, they established the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom as an oppositional state based in Tianjing (present-day Nanjing) and gained control of a significant part of southern China, eventually expanding to command a population base of nearly 30 million people.

For over a decade, the Taiping occupied and fought across much of the mid and lower Yangtze valley. Ultimately devolving into total war, the conflict between the Taiping and the Qing was the largest in China since the Qing conquest in 1644 and it involved every province of China proper except Gansu. It ranks as one of the bloodiest wars in human history, the bloodiest civil war, and the largest conflict of the 19th century. The best estimate of the war dead is 20–30 million, but other credible estimates nonetheless reach as high as 70 million, with millions more displaced.[10][11][12] 30 million people fled the conquered regions to foreign settlements or other parts of China.[13]

Severely weakened by an attempted coup and unable to capture the Qing capital of Beijing, the Taipings were ultimately defeated by decentralized, irregular armies such as the Xiang Army commanded by Zeng Guofan. Having already moved down the Yangtze River and recaptured the key city of Anqing, Zeng’s Xiang Army began besieging Nanjing in May 1862. Two years later, on June 1, 1864, Hong Xiuquan died and Nanjing fell barely a month later. After the defeat of the Taipings, Zeng Guofan and many of his protégés, such as Li Hongzhang and Zuo Zongtang, were celebrated as saviors of the Qing empire and became some of the most powerful men in late-19th-century China.

Names

The terms used for the conflict and its participants often reflect the viewpoint of the writer. In the 19th century the Qing did not identify the conflict as either a civil war or a social movement—since that would lend the Taiping credibility—but instead referred to the tumultuous hostilities as a period of chaos (乱), rebellion (逆) or military ascendancy (军兴).[14] They often called it the Hong-Yang Rebellion (洪杨之乱), with reference to its two most prominent leaders, Hong Xiuquan and Yang Xiuqing, or dismissively labelled it the Red Sheep Rebellion (红羊之乱), because "Hong-Yang" sounds like "Red Sheep" in Chinese.

In modern Chinese the war is often called the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom Movement, reflecting both a Nationalist and a Communist view that the Taiping represented a popular ideological movement of either Han nationalist or proto-communist persuasion. The scholar Jian Youwen is among those who refer to the rebellion as the "Taiping Revolutionary Movement" on the grounds that it worked towards a complete change in the political and social system rather than towards the replacement of one dynasty with another.[15] Many Western historians refer to the conflict as the "Taiping Rebellion." Recently, however, scholars such as Tobie Meyer-Fong and Stephen Platt have argued that the term "Taiping Rebellion" is biased because it implies that the Qing were a legitimate government fighting against illegitimate Taiping rebels. They argue, instead, that the conflict should be considered a "civil war."[14] Other historians, such as Jürgen Osterhammel, call the conflict the "Taiping Revolution" due to the rebels' radical transformational aims and the social revolution they launched.[6]

Little is known about how the Taiping themselves referred to the war, but they often described the Qing in general and the Manchus in particular as some kind of demons or monsters (妖), reflecting Hong's proclamation that they were fighting a holy war to rid the world of demons and establish paradise on earth.[16] The Qing referred to the Taiping as Yue Bandits (粤匪 or 粤贼) in official sources, reflecting the movement's origins in the southeastern provinces of Guangxi and Guangdong ("Yue" being an abbreviated form of "Guangdong"). More colloquially, the Chinese called the Taiping some variant of Long-Hairs (长毛鬼、长髪鬼、髪逆、髪贼), since they did not shave their foreheads and braid their hair into a queue as Qing subjects were obligated to do, instead allowing their hair to grow long.[14] In the 19th century, Western observers, depending on their ideological position, referred to the Taiping as "revolutionaries", "insurgents" or "rebels". In English, the Heavenly Kingdom of Peace has often been shortened to simply the Taiping, from the word "Peace" in the "Heavenly Kingdom of Peace," but this term was never used either by the Taiping themselves or by their enemies.

History

Origins

Qing-dynasty China in the early to mid-19th century suffered a series of natural disasters, economic problems and defeats at the hands of the Western powers, in particular the humiliating defeat in 1842 by the British Empire in the First Opium War.[17] Farmers were heavily overtaxed, rents were rising, and peasants were deserting their lands in droves.[18] These problems were only exacerbated by a trade imbalance caused by the large-scale illicit import of opium.[19] Banditry was becoming more common, as were secret societies and self-defense units, all of which led to an increase in small-scale warfare.[20]

Meanwhile, the population of China had exploded, nearly doubling between 1766 and 1833, while the amount of cultivated land was stagnant.[21] The government, led by ethnic Manchus, had become increasingly corrupt.[22] Anti-Manchu sentiments were strongest in southern China among the Hakka community, a Han Chinese subgroup. Meanwhile, Christianity was beginning to make inroads in China.[23]

In 1837 Hong Xiuquan, a Hakka from a poor mountain village, once again failed the imperial examination, frustrating his ambition to become a scholar-official in the civil service.[24][25] He returned home, fell sick and was bedridden for several days, during which he experienced mystical visions.[26][27][28] In 1843, after carefully reading a pamphlet he had received years before from a Protestant Christian missionary, Hong declared that he now understood that his vision meant that he was the younger brother of Jesus and that he had been sent to rid China of the "devils", including the corrupt Qing government and Confucian teachings.[29][30] In 1847 Hong went to Guangzhou, where he studied the Bible with Issachar Jacox Roberts, an American Baptist missionary.[31] Roberts refused to baptize him and later stated that Hong's followers were "bent on making their burlesque religious pretensions serve their political purpose."[32]

Hong began preaching across Guangxi in 1844. Soon after, his follower Feng Yunshan founded the God Worshipping Society, a movement which adopted Hong's fusion of Christianity, Daoism, Confucianism and indigenous millenarianism, which Hong presented as a restoration of the ancient Chinese faith in Shangdi.[33][34][35] The Taiping faith, says one historian, "developed into a dynamic new Chinese religion ... Taiping Christianity".[35] As the movement's power grew, it at first suppressed groups of bandits and pirates in southern China in the late 1840s. Later, when persecuted by local Qing authorities, its activities evolved into guerrilla warfare and subsequently into a widespread civil war. Eventually, two other God Worshippers claimed to possess the ability to speak as members of the Holy Trinity, God the Father in the case of Yang Xiuqing and Jesus Christ in the case of Xiao Chaogui.[36][37]

Early years

The Taiping Rebellion began in the southern province of Guangxi when local officials launched a campaign of religious persecution against the God Worshipping Society. In early January 1851, following a small-scale battle in late December 1850, a 10,000-strong rebel army organized by Feng Yunshan and Wei Changhui routed Qing forces stationed in Jintian (present-day Guiping, Guangxi). Taiping forces successfully repulsed an attempted imperial reprisal by the Green Standard Army against the Jintian Uprising.

On January 11, 1851, Hong declared himself the Heavenly King of the Heavenly Kingdom of Peace (or Taiping Heavenly Kingdom), from which comes the term "Taipings" that has often been applied to them in the English language. The Taipings began marching north in September 1851 to escape Qing forces closing in on them. The Taiping army pressed north into Hunan following the Xiang River, besieging Changsha, occupying Yuezhou, and then capturing Wuchang in December 1852 after reaching the Yangtze River. At this point the Taiping leadership decided to move east along the Yangtze River. Anqing was captured in February 1852.

Some of the triads collaborated with the Taiping rebels at this stage. One triad leader, Hong Daquan or Tian De, may have exerted a political influence comparable to that of Hong Xiuquan in the early years of the rebellion, but his historicity is a matter of dispute. Rumours at the time suggested that the Taipings had found a descendant of the Ming dynasty and crowned him king. In 1852, the Qing government published a possibly spurious confession by a captured rebel claiming to be Tian De, who said that Hong Xiuquan had made him co-sovereign of the Heavenly Kingdom.[38] Reports of Tian De ceased in 1853,[39] and the fall of Nanjing that year led to a deterioration of relations between the Taiping rebels and the triads.[40]

Middle years

On March 19, 1853, the Taipings captured the city of Nanjing and Hong declared it the Heavenly Capital of his kingdom. Since the Taipings considered the Manchus to be demons, they first killed all the Manchu men, then forced the Manchu women outside the city and burned them to death.[41] Shortly thereafter, the Taiping launched concurrent Northern and Western expeditions, in an effort to relieve pressure on Nanjing and achieve significant territorial gains.[42][43] The former expedition was a complete failure but the latter achieved limited success.[43][44]

In 1853 Hong Xiuquan withdrew from active control of policies and administration to rule exclusively by written proclamations. He lived in luxury and had many women in his inner chamber, and often issued religious strictures. He clashed with Yang Xiuqing, who challenged his often impractical policies, and became suspicious of Yang's ambitions, his extensive network of spies and his claims of authority when "speaking as God". This tension culminated in the 1856 Tianjing Incident, wherein Yang and his followers were slaughtered by Wei Changhui, Qin Rigang, and their troops on Hong Xiuquan's orders.[45] Shi Dakai's objection to the bloodshed led to his family and retinue being killed by Wei and Qin with Wei ultimately planning to imprison Hong.[46] Wei's plans were ultimately thwarted and he and Qin were executed by Hong.[46] Shi Dakai was given control of five Taiping armies, which were consolidated into one. But fearing for his life, he departed from Tianjing and headed west towards Sichuan.

With Hong withdrawn from view and Yang out of the picture, the remaining Taiping leaders[who?] tried to widen their popular support and forge alliances with European powers, but failed on both counts. The Europeans decided to stay officially neutral, though European military advisors served with the Qing army.

Inside China, the rebellion faced resistance from the traditionalist rural classes because of hostility to Chinese customs and Confucian values. The landowning upper class, unsettled by the Taiping ideology and the policy of strict separation of the sexes, even for married couples, sided with government forces and their Western allies.

In Hunan, a local irregular army called the Xiang Army or Hunan Army, under the personal leadership of Zeng Guofan, became the main armed force fighting for the Qing against the Taiping. Zeng's Xiang Army proved effective in gradually turning back the Taiping advance in the western theater of the war and ultimately retaking much of Hubei and Jiangxi provinces. In December 1856 Qing forces retook Wuchang for the final time. The Xiang Army captured Jiujiang in May 1858 and then the rest of Jiangxi province by September.

In 1859 Hong Rengan, Hong Xiuquan's cousin, joined the Taiping forces in Nanjing and was given considerable power by Hong.[41] Hong Rengan developed an ambitious plan to expand the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom's boundaries.

In May 1860 the Taiping defeated the imperial forces that had been besieging Nanjing since 1853, eliminating them from the region and opening the way for a successful invasion of southern Jiangsu and Zhejiang provinces, the wealthiest region of the Qing Empire. The Taiping rebels were successful in taking Hangzhou on March 19th, 1860, Changzhou on May 26th, and Suzhou on June 2nd to the east (see Second rout of the Jiangnan Daying). While Taiping forces were preoccupied in Jiangsu, Zeng's forces moved down the Yangtze River.

Fall of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom

An attempt to take Shanghai in August 1860 was repulsed by an army of Qing troops supported by European officers under the command of Frederick Townsend Ward assisted by local strategic support of the French diplomat Albert-Édouard Levieux de Caligny. This army would become known as the "Ever Victorious Army", a seasoned and well trained Qing military force commanded by Charles George Gordon, and would be instrumental in the defeat of the Taiping rebels.

In 1861, around the time of the death of the Xianfeng Emperor and ascension of the Tongzhi Emperor, Zeng Guofan's Xiang Army captured Anqing with help from a British naval blockade on the city.[47] Near the end of the 1861 the Taipings launched a final Eastern Expedition. Ningbo was easily captured on December 9th, and Hangzhou was besieged and finally captured on December 31st, 1861. Taiping troops surrounded Shanghai in January, 1862, but were unable to capture it.

The Ever-Victorious Army repulsed another attack on Shanghai in 1862 and helped to defend other treaty ports such as Ningbo, reclaimed on May 10. They also aided imperial troops in reconquering Taiping strongholds along the Yangtze River.

In 1863 Shi Dakai surrendered to the Qing near the Sichuan capital Chengdu and was executed by slow-slicing.[48] Some of his followers escaped or were released and continued the fight against the Qing.

Qing forces were reorganised under the command of Zeng Guofan, Zuo Zongtang and Li Hongzhang, and the Qing reconquest began in earnest. Zeng Guofan began in Hunan by recruiting a peasant army, later known as the Xiang Army, based on the teachins of the 16th century Ming-dynasty general Qi Jiguang.[citation needed] By early 1864, Qing control in most areas had been reestablished.[49]

In May 1862 the Xiang Army began directly besieging Nanjing and managed to hold firm despite numerous attempts by the numerically superior Taiping Army to dislodge them. Hong Xiuquan declared that God would defend Nanjing, but in June 1864, with Qing forces approaching, he died of food poisoning as a consequence of eating wild vegetables when the city ran low on food supplies. He was sick for 20 days before succumbing and a few days after his death, Qing forces took the city. His body was buried in the former Ming Imperial Palace, and was later exhumed on orders of Zeng Guofan to verify his death, and then cremated. Hong's ashes were later blasted out of a cannon in order to ensure that his remains have no resting place as eternal punishment for the uprising.

Four months before the fall of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom, Hong Xiuquan abdicated in favor of his eldest son, Hong Tianguifu, who was 15 years old. The younger Hong was inexperienced and powerless, so the kingdom was quickly destroyed when Nanjing fell in July 1864 to the imperial armies after protracted street-by-street fighting. Tianguifu and few others escaped but were soon caught and executed. Most of the Taiping princes were executed. A small remainder of loyal Taiping forces had continued to fight in northern Zhejiang, rallying Tianguifu, but after Tianguifu's capture on October 25, 1864, Taiping resistance was gradually pushed into the highlands of Jiangxi, Zhejiang, Fujian and finally Guangdong, where one of the last Taiping loyalists, Wang Haiyang, was defeated on January 29, 1866.

Aftermath

Although the fall of Nanjing in 1864 marked the destruction of the Taiping regime, the fight was not yet over. There were still several hundred thousand Taiping troops continuing the fight, with more than a quarter-million fighting in the border regions of Jiangxi and Fujian alone. It was not until August 1871 that the last Taiping army led by Shi Dakai's commander, Li Fuzhong (李福忠), was completely wiped out by government forces in the border region of Hunan, Guizhou and Guangxi.[50]

In 1865, Liu Yongfu escaped in command of a splinter group known as the Black Flag Army (Chinese: 黑旗军; pinyin: Hēiqí Jūn; Vietnamese: Quân cờ đen), which mainly recruited soldiers of ethnic Zhuang background, and left Guangxi and moved into Upper Tonkin in the Empire of Annam, where his forces engaged in combat against the French. He later became the second and last leader of the short-lived Republic of Formosa (5 June–21 October 1895).

Other "Flag Gangs" armed with the latest weapons, disintegrated into bandit groups that plundered remnants of the Lan Xang kingdom, and were then engaged in combat against the incompetent forces of King Rama V (r. 1868–1910) until 1890, when the last of the groups eventually disbanded. Their victims did not know where the bandits had come from and, when they plundered Buddhist temples, they were mistaken for Chinese Muslims from Yunnan called Hui in Mandarin and Haw in the Lao language (Thai: ฮ่อ,[51]) which resulted in the protracted series of conflicts being misnamed the Haw wars.

Death toll

With no reliable census at the time, estimates of the death toll of the rebellion are necessarily based on projections. The most widely cited sources estimate the total number of deaths during the 15 years of the rebellion to be approximately 20–30 million civilians and soldiers.[52][53] Most of the deaths were attributed to plague and famine.

Concurrent rebellions

The Nian Rebellion (1853–68), and several Chinese Muslim rebellions in the southwest (Panthay Rebellion, 1855–73) and the northwest (Dungan revolt, 1862–77) continued to pose considerable problems for the Qing dynasty.

Occasionally the Nian rebels would collaborate with Taiping forces, for instance during the Northern Expedition.[54] As the Taiping rebellion lost ground, particularly after the fall of Nanjing in 1864, former Taiping soldiers and commanders like Lai Wenguang were incorporated into Nian ranks.

After the failure of the Red Turban Rebellion (1854–1856) to capture Guangzhou, their soldiers retreated north into Jiangxi and combined forces with Shi Dakai.[55] After the defeat of the Li Yonghe and Lan Chaoding rebellion in Sichuan, remnants combined with Taiping forces in Shaanxi.[56] Remnant forces of the Small Swords Society uprising in Shanghai regrouped with the Taiping army.[57]

Du Wenxiu, who led the Panthay Rebellion, was in contact with the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom. He was not aiming his rebellion at Han Chinese, but was anti-Qing and wanted to destroy the Qing government.[58][59] Du's forces led multiple non-Muslim forces, including Han Chinese, Li, Bai, and Hani peoples.[60] They were assisted by non-Muslim Shan and Kakhyen and other hill tribes in the revolt.[61]

The other Muslim rebellion, the Dungan revolt, was the reverse: it was not aimed at overthrowing the Qing dynasty since its leader Ma Hualong accepted an imperial title. Rather, it erupted due to intersectional fighting between Muslim factions and Han Chinese. Various groups fought each other during the Dungan revolt without any coherent goal.[62] According to modern researchers,[63] the Dungan rebellion began in 1862 not as a planned uprising but as a coalescence of many local brawls and riots triggered by trivial causes, among these were false rumours that the Hui Muslims were aiding the Taiping rebels. However, the Hui Ma Xiaoshi claimed that the Shaanxi Muslim rebellion was connected to the Taiping.[64]

Jonathan Spence says that a key reason for the Taiping's defeat was its overall inability to coordinate with other rebellions.[65]

Taiping Heavenly Kingdom's policies

The rebels announced social reforms, including strict separation of the sexes, abolition of foot binding, land socialisation, and "suppression" of private trade. In religion, the Kingdom tried to replace Confucianism, Buddhism and Chinese folk religion with the Taiping's version of Christianity, God Worshipping, which held that Hong Xiuquan was the younger brother of Jesus. The libraries of the Buddhist monasteries were destroyed, almost completely in the case of the Yangtze Delta area.[66] Temples of Daoism, Confucianism, and other traditional beliefs were often defaced.[67]

Military

Taiping forces

The Taiping army was the rebellion's key strength. It was marked by a high level of discipline and fanaticism.[citation needed] They typically wore a uniform of red jackets with blue trousers, and grew their hair long so in China they were nicknamed "long hair". In the beginning of the rebellion, the large numbers of women serving in the Taiping army also distinguished it from other 19th-century armies. However after 1853 there ceased being many women in the Taiping army. Su Sanniang and Qiu Ersao is an example of two women who became one of the leaders of the Nian Rebels and Red Turban respectively.

Combat was always bloody and extremely brutal, with little artillery but huge forces equipped with small arms. Both armies would attempt to push each other off of the battlefield, and though casualties were high, few battles were decisively won. The Taiping army's main strategy of conquest was to take major cities, consolidate their hold on the cities, then march out into the surrounding countryside to recruit local farmers and battle government forces. Estimates of the overall size of the Taiping army are around 2,000,000 soldiers. The army's organization was allegedly inspired by that of the Qin dynasty. Each army corp consisted of roughly 13,000 men. These corps were placed into armies of varying sizes. In addition to the main Taiping forces organised along the above lines, there were also thousands of pro-Taiping groups fielding their own forces of irregulars.

While the Taiping rebels did not have the support of Western governments, they were relatively modernized in terms of weapons. An ever- growing number of Western weapons dealers and blackmarketeers sold Western weapons such as modern muskets, rifles, and cannons to the rebels. As early as 1853, Taiping Tianguo soldiers had been using guns and ammunition sold by Westerners. Rifles and gunpowder were smuggled into China by English and American traders as "snuff and umbrellas". They were partially equipped with surplus equipment sold by various Western companies and military units' stores, both small arms and artillery. One shipment of weaponry from an American dealer in April 1862 already "well known for their dealings with rebels" was listed as 2,783 (percussion cap) muskets, 66 carbines, 4 rifles, and 895 field artillery guns, as well as carrying passports signed by the Loyal King. Almost two months later, a ship was stopped with 48 cases of muskets, and another ship with 5000 muskets. Western mercenaries such as British, Italians, French and Americans also joined, although many were described as merely taking the opportunity to plunder Chinese. The Taiping forces constructed iron foundries where they were making heavy cannons, described by Westerners as vastly superior to Qing cannons.[68] Just before his execution, Taiping Loyal King Li Xiucheng advised his enemies that war with the Western powers was coming and the Qing must buy the best Western cannons and gun carriages, and have the best Chinese craftsmen learn to build exact copies, teaching other craftsmen as well.[69]

Taiping troops were praised by Westerners for their courage under fire, their speed in building defensive works, and their skill at using mobile pontoon bridges to hasten communications and transportation.[70]

There was also a small Taiping Navy, composed of captured boats, that operated along the Yangtze and its tributaries. Among the Navy's commanders was the Hang King Tang Zhengcai.

Ethnic structure of the Taiping army

This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2013) |

Ethnically, the Taiping army was at the outset formed largely from these groups: the Hakka, a Han Chinese subgroup; the Cantonese, local residents of Guangdong province; and the Zhuang (a non-Han ethnic group). It is no coincidence that Hong Xiuquan and the other Taiping royals were Hakka.

As a Han subgroup, the Hakka were frequently marginalised economically and politically, having migrated to the regions which their descendants presently inhabit only after other Han groups were already established there. For example, when the Hakka settled in Guangdong and parts of Guangxi, speakers of Yue Chinese (Cantonese) were already the dominant regional Han group there and they had been so for some time, just as speakers of various dialects of Min are locally dominant in Fujian province.

The Hakka settled throughout southern China and beyond, but as latecomers they generally had to establish their communities on rugged, less fertile land scattered on the fringes of the local majority group's settlements. As their name ("guest households") suggests, the Hakka were generally treated as migrant newcomers, often subject to hostility and derision from the local majority Han populations. Consequently, the Hakka, to a greater extent than other Han Chinese, have been historically associated with popular unrest and rebellion.

The other significant ethnic group in the Taiping army was the Zhuang, an indigenous people of Tai origin and China's largest non-Han ethnic minority group. Over the centuries, Zhuang communities had been adopting Han Chinese culture. This was possible because Han culture in the region accommodates a great deal of linguistic diversity, so the Zhuang could be absorbed as if the Zhuang language were just another Han Chinese dialect (which it is not). Because Zhuang communities were integrating with the Han at different rates, a certain amount of friction between the Han and the Zhuang was inevitable, with Zhuang unrest leading to armed uprisings on occasion.[71] The second tier of the Taiping army was an ethnic mix that included many Zhuang. Prominent at this level was Shi Dakai, who was half-Hakka, half-Zhuang and spoke both languages fluently, making him quite a rare asset to the Taiping leadership.[citation needed]

In the later stages of the Taiping Rebellion, the number of Han Chinese in the army from Han groups other than the Hakka increased substantially. However, the Hakka and the Zhuang (who constituted as much as 25% of the Taiping Army), as well as other non-Han ethnic minority groups (many of them of Tai origin related to the Zhuang), continued to feature prominently in the rebellion throughout its duration, with virtually no leaders emerging from any Han Chinese group other than the Hakka.[citation needed]

Social structure of the Taiping Army

Socially and economically, the Taiping rebels came almost exclusively from the lowest classes. Many of the southern Taiping troops were former miners, especially those coming from the Zhuang. Very few Taiping rebels, even in the leadership caste, came from the imperial bureaucracy. Almost none were landlords and in occupied territories landlords were often executed.

Qing forces

Opposing the rebellion was an imperial army with over a million regulars and unknown thousands of regional militias and foreign mercenaries operating in support. Among the imperial forces was the elite Ever Victorious Army, consisting of Chinese soldiers led by a European officer corps (see Frederick Townsend Ward and Charles Gordon), backed by British arms companies like Willoughbe & Ponsonby.[72] A particularly famous imperial force was Zeng Guofan's Xiang Army. Zuo Zongtang from Hunan province was another important Qing general who contributed in suppressing the Taiping Rebellion. Where the armies under the control of dynasty itself were unable to defeat the Taiping, these gentry-led Yong Ying armies were able to succeed.[73]

Although keeping accurate records was something imperial China traditionally did very well, the decentralized nature of the imperial war effort (relying on regional forces) and the fact that the war was a civil war and therefore very chaotic, meant that reliable figures are impossible to find. The destruction of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom also meant that any records it possessed were destroyed, the percentage of records said to have survived is around 10%.

Over the course of the conflict, around 90% of recruits to the Taiping side would be killed or defect.[74]

The organisation of the Qing Imperial Army was thus:

- Eight Banners Army: 250,000 soldiers[75]

- Green Standard Army: ~610,000 soldiers[76]

- Xiang (Hunan) Army: 130,000 soldiers[77]

- Huai (Anhui) Army: 70,000 soldiers[77]

- Chu Army: 40,000 soldiers[77]

- Ever Victorious Army: 5,000 soldiers[78]

- Village Militias: unknown thousands

Total war

The Taiping Rebellion was a total war. Almost every citizen of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom was given military training and conscripted into the army to fight against Qing imperial forces. Under the Taiping household registration system, one adult male from each household was to be conscripted into the Army.[79]

During this conflict, both sides tried to deprive each other of the resources needed to continue the war and it became standard practice to destroy agricultural areas, butcher the population of cities, and in general exact a brutal price from captured enemy lands to drastically weaken the opposition's war effort. This war was total in the senses that civilians on both sides participated to a significant extent in the war effort and that armies on both sides waged war on the civilian population as well as military forces. Contemporary accounts describe the amount of desolation to rural areas as a result of the conflict.[80]

This resulted in a massive civilian death toll with some 600 towns destroyed[81] and other bloody policies resulting. Since the rebellion began in Guangxi, Qing forces allowed no rebels speaking its dialect to surrender.[82] Reportedly in the province of Guangdong, it is written that 1,000,000 were executed because after the collapse of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom, the Qing dynasty launched waves of massacres against the Hakkas, killing up to 30,000 each day during the height of the massacres.[83][84] These policies of mass murder of civilians occurred elsewhere in China, including Anhui,[85][86] and Nanjing.[87]

Legacy

Beyond the staggering human and economic devastation, the Taiping Rebellion led to lasting changes to the late Qing dynasty. Power was, to a limited extent, decentralized, and ethnic Han Chinese officials were more widely employed in high positions.[88] The use of regular troops was gradually abandoned and replaced with personally-organized armies.[88] Ultimately, the Taiping Rebellion provided inspiration to Sun Yat-sen and other future revolutionaries, with some surviving Taiping veterans even joining the Revive China Society,[89] as well as the Chinese Communist Party, which characterised the rebellion as a proto-communist uprising.[90]

The massive death toll resulting from the rebellion, especially in the Yangtze delta region, led to a shortage in labor supply for the first time in centuries, and labor became relatively more expensive than land.[91]

Merchants in Shanxi and the Huizhou region of Anhui became less prominent as the rebellion disrupted trade in much of the country.[91] However trade in coastal regions, especially Guangzhou (Canton) and Ningbo were less affected by violence in inland areas. Streams of refugees entering Shanghai led to the economic development of the city, which was previously less commercially relevant than other cities in the area.

It is thought that only a tenth of Taiping-published records survive to this day, as they were mostly destroyed by the Qing in an attempt to rewrite the history of the conflict.[92]

In popular culture

The Taiping Rebellion has been treated in historical novels. Robert Elegant's 1983 Mandarin depicts the time from the point of view of a Jewish family living in Shanghai.[93] In Flashman and the Dragon, the fictional Harry Paget Flashman recounts his adventures during the Second Opium War and the Taiping Rebellion. In Lisa See's novel Snow Flower and the Secret Fan the title character is married to a man who lives in Jintian and the characters get caught up in the action. Amy Tan's The Hundred Secret Senses takes place in part during the time of the Taiping Rebellion. Rebels of the Heavenly Kingdom by Katherine Paterson is a young adult novel set during the Taiping Rebellion. Li Bo's Tienkuo: The Heavenly Kingdom takes place within the Taiping capital at Nanjing [94]

The war has also been depicted in television shows and films. In 2000 CCTV produced The Taiping Heavenly Kingdom, a 46-episode series about the Taiping Rebellion. In 1988 Hong Kong's TVB produced Twilight of a Nation, a 45-episode drama about the Taiping Rebellion. The Warlords is a 2007 historical film set in the 1860s showing Gen. Pang Qinyun, leader of the Shan Regiment, as responsible for the capture of Suzhou and Nanjing.

See also

- Boxer Rebellion

- Christianity in China

- Chinese sovereign

- Nepalese–Tibetan War

- List of revolutions and rebellions

- List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll

- Miao Rebellion (1854–73)

- Nian Rebellion

- Punti-Hakka Clan Wars

- Millennarianism in colonial societies

References

- ^ a b R. G. Tiedemann, ed., Handbook of Christianity in China, Volume 2, p. 390

- ^ Heath, pp. 11–16

- ^ Heath, p. 4

- ^ Heath, p. 7

- ^ Platt (2012), p. p. xxiii.

- ^ a b Osterhammel (2015), pp. 547–551.

- ^ Jen Yu-wen, The Taiping Revolutionary Movement 4-7 (1973)

- ^ C. A. Curwen, Taiping Rebel: The Deposition of Li Hsiu-ch'eng 1 (1977)

- ^ Michael 1966, p. 7.

- ^ Platt (2012).

- ^ Cao, Shuji (2001). Zhongguo Renkou Shi [A History of China's Population]. Shanghai: Fudan Daxue Chubanshe. pp. 455, 509.

- ^ Hanzhi Deng, Fiscal Transitions In Late Qing China, 1850-1900

- ^ Bickers, Robert; Jackson, Isabella. Treaty Ports in Modern China: Law, Land and Power. p. 224.

- ^ a b c Meyer-Fong (2013), pp. 11–12.

- ^ Jian (1973), pp. 4–7.

- ^ Spence (1996), pp. 115–116, 160–163, 181–182. sfnp error: multiple targets (4×): CITEREFSpence1996 (help)

- ^ Chesneaux, Jean. PEASANT REVOLTS IN CHINA, 1840–1949. Translated by C. A. Curwen. New York: W. W. Norton, 1973. p. 23-24

- ^ Michael 1966, p. 4, 10.

- ^ Michael 1966, p. 15–16.

- ^ Michael 1966, p. 10–12.

- ^ Michael 1966, p. 14–15.

- ^ C. A. Curwen, Taiping Rebel: The Deposition of Li Hsiu-ch'eng 2 (1977)

- ^ Pamela Kyle Crossley, The Wobbling Pivot: China Since 1800 103 (2010)

- ^ Michael 1966, p. 21–22.

- ^ Jen Yu-wen, The Taiping Revolutionary Movement 11-12, 15-18 (1973)

- ^ Jen Yu-wen, The Taiping Revolutionary Movement 15-18 (1973)

- ^ Michael 1966, p. 23.

- ^ Spence (1996), pp. 47–49. sfnp error: multiple targets (4×): CITEREFSpence1996 (help)

- ^ Jen Yu-wen, The Taiping Revolutionary Movement 20 (1973)

- ^ Spence (1996), p. 64. sfnp error: multiple targets (4×): CITEREFSpence1996 (help)

- ^ Teng, Yuah Chung "Reverend Issachar Jacox Roberts and the Taiping Rebellion" The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol 23, No. 1 (Nov 1963), pp. 55–67

- ^ Rhee, Hong Beom (2007). Asian Millenarianism: An Interdisciplinary Study of the Taiping and Tonghak Rebellions in a Global Context. Cambria Press, Youngstown, NY. pp. 163, 172, 186–7, 191.

- ^ Spence (1996), pp. 78–80. sfnp error: multiple targets (4×): CITEREFSpence1996 (help)

- ^ Kilcourse, Carl S. (2016). Taiping Theology: The Localization of Christianity in China, 1843–64. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781137537287.

- ^ a b Reilly (2004), p. 4.

- ^ Spence (1996), pp. 97–99. sfnp error: multiple targets (4×): CITEREFSpence1996 (help)

- ^ Michael 1966, p. 35.

- ^ Perry 1984, p. 348.

- ^ Levenson 1962, p. 444.

- ^ Perry 1984, p. 350.

- ^ a b Reilly (2004), p. 139.

- ^ Michael 1966, p. 93.

- ^ a b Maochun Yu, The Taiping Rebellion: A Military Assessment of Revolution and Counterrevolution, printed in A Military History of China 138 (David A. Graff & Robin Higham eds., 2002)

- ^ Michael 1966, p. 94–95.

- ^ Spence (1996), pp. 237, 242–44. sfnp error: multiple targets (4×): CITEREFSpence1996 (help)

- ^ a b Spence (1996), p. 244. sfnp error: multiple targets (4×): CITEREFSpence1996 (help)

- ^ Elleman.

- ^ Elleman, p. 52.

- ^ Richard J. Smith, Mercenaries and Mandarins: The Ever-Victorious Army in Nineteenth Century China (Millwood, N.Y.: KTO Press, 1978), passim.

- ^ Tucker, Spencer C. (2017). The roots and consequences of civil wars and revolutions : conflicts that changed world history. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 229. ISBN 9781440842948. OCLC 956379787.

- ^ Glenn S. (March 15, 2012). "ฮ่อ Haaw". Royal Institute – 1982. Thai-language.com. Archived from the original (Dictionary) on May 1, 2012. Retrieved April 5, 2012.

- ^ Taiping Rebellion, Britannica Concise

- ^ "Necrometrics." Nineteenth Century Death Tolls cites a number of sources, some of which are reliable.

- ^ Spence, God's Chinese Son, p. [page needed].

- ^ Platt, p. [page needed].

- ^ 王新龙 (2013). 大清王朝4. 青苹果数据中心.

- ^ Li, Xiaobing (2012). China at War: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 415. ISBN 1598844156.

- ^ Michael Dillon (1999). China's Muslim Hui community: migration, settlement and sects. Richmond: Curzon Press. p. 59. ISBN 0-7007-1026-4. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ David G. Atwill (2005). The Chinese sultanate: Islam, ethnicity, and the Panthay Rebellion in southwest China, 1856–1873. Stanford University Press. p. 139. ISBN 0-8047-5159-5. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Chinese studies in philosophy, Volume 28. M. E. Sharpe. 1997. p. 67. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Albert Fytche (1878). Burma past and present. C. K. Paul & co. p. 300. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Garnaut, Anthony. "From Yunnan to Xinjiang:Governor Yang Zengxin and his Dungan Generals" (PDF). Pacific and Asian History, Australian National University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-09. Retrieved 2010-07-14. Page 98

- ^ Lipman (1998), p. 120–121

- ^ Sir H. A. R. Gibb (1954). Encyclopedia of Islam, Volumes 1–5. Brill Archive. p. 849. ISBN 90-04-07164-4. Retrieved 2011-03-26.

- ^ Spence, The Search for Modern China, p. 176.

- ^ Tarocco, Francesca (2007), The Cultural Practices of Modern Chinese Buddhism: Attuning the Dharma, London: Routledge, p. 48, ISBN 9781136754395.

- ^ Platt

- ^ Spence, Jonathan D. (1996). God's Chinese Son: The Taiping Heavenly Kingdom of Hong Xiuquan. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 237-238, 300, 311. ISBN 0393285863.

- ^ Spence, Jonathan D. (1996). "22". God's Chinese Son: The Taiping Heavenly Kingdom of Hong Xiuquan. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0393285863.

- ^ Spence, Jonathan D. (1996). God's Chinese Son: The Taiping Heavenly Kingdom of Hong Xiuquan. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 165, 239. ISBN 0393285863.

- ^ Ramsey, Robert, S. (1987). The Languages of China. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. pp. 167, 232–236. ISBN 0-691-06694-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ J. Chappell (2018). Some Corner of a Chinese Field: The politics of remembering foreign veterans of the Taiping civil war. Modern Asian Studies, 1-38. doi:10.1017/S0026749X16000986

- ^ Michael 1966, p. ?.

- ^ Deng, Kent G. (2011) China's Political Economy in Modern Times: Changes and Economic Consequences, 1800-2000. Routledge, Oct 5, 2011 - BUSINESS & ECONOMICS - 320 pages

- ^ Heath, p. 11

- ^ Heath, pp. 13–14

- ^ a b c Heath, p. 16

- ^ Heath, p. 33

- ^ Spence (1996), chapter 13. sfnp error: multiple targets (4×): CITEREFSpence1996 (help)

- ^ Spence, p. 1996.

- ^ Purcell, Victor. CHINA. London: Ernest Benn, 1962. p. 168

- ^ Ho Ping-ti. STUDIES ON THE POPULATION OF CHINA, 1368–1953. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1959. p. 237

- ^ The Hakka Odyssey & their Taiwan homeland - Page 120 Clyde Kiang - 1992

- ^ Purcell, Victor. CHINA. London: Ernest Benn, 1962. p. 167

- ^ Quoted in Ibid., p. 239.

- ^ Chesneaux, Jean. PEASANT REVOLTS IN CHINA, 1840–1949. Translated by C. A. Curwen. New York: W. W. Norton, 1973. p. 40

- ^ Pelissier, Roger. THE AWAKENING OF CHINA: 1793–1949. Edited and Translated by Martin Kieffer. New York: Putnam, 1967. p. 109

- ^ a b Jen Yu-wen, The Taiping Revolutionary Movement 8 (1973)

- ^ Jen Yu-wen, The Taiping Revolutionary Movement 9 (1973)

- ^ Daniel Little, Marx and the Taipings (2009)

- ^ a b Rowe, William T. (September 10, 2012). China's Last Empire: The Great Qing. ISBN 978-0674066243.

- ^ "The Jen Yu-wen Collection on the Taiping Revolutionary Movement". The Yale University Library Gazette. 49 (3): 293–296. January 1975.

- ^ Kirkus (1983), "Mandarin, by Robert S. Elegant", Kirkus

- ^ Li Bo Tienkuo: The Heavenly Kingdom ISBN 1542660572

- Osterhammel, Jürgen (2015). The Transformation of the World: A Global History of the Nineteenth Century. Translated by Patrick Camiller. Princeton, New Jersey; Oxford: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691169804.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

Contemporaneous accounts

- Lindley, Augustus, Ti-ping Tien-Kwoh: The History of the Ti-Ping Revolution (1866, reprinted 1970) OCLC 3467844 Google books access

- Xiucheng, Li, trans. Lay, W.T., The Autobiography of the Chung-Wang (Confession of the Loyal Prince) (reprinted 1970) ISBN 978-0-275-02723-0

- Thomas Taylor Meadows, The Chinese and Their Rebellions, Viewed in Connection with Their National Philosophy, Ethics, Legislation, and Administration. To Which Is Added, an Essay on Civilization and Its Present State in the East and West. (London: Smith, Elder; Bombay: Smith, Taylor, 1856). American Libraries eBook text

- Brine, Lindesay, The Taeping rebellion in China (London: J. Murray, 1862)

- Ven. Archdeacon Moule, Personal Recollections of the T'ai-p'ing Rebellion 1861-63 (Shanghai: Printed at the "Celestial Empire" Office 1884).

Documents

- Franz H. Michael, ed.The Taiping Rebellion: History and Documents (Seattle,: University of Washington Press, 1966). 3 vols. Volumes two and three select and translate basic documents.

Modern monographs and surveys

- Spence, Jonathan D. (1996). God's Chinese Son: The Taiping Heavenly Kingdom of Hong Xiuquan. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 0393038440.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - -- The Search for Modern China. New York: Norton (1999). Standard textbook.

- Jack Gray, Rebellions and Revolutions: China from the 1800s to the 1980s (1990), ISBN 0-19-821576-2

- Ian Heath. The Taiping Rebellion, 1851–1866. London ; Long Island City: Osprey, Osprey Military Men-at-Arms Series, 1994. ISBN 1-85532-346-X (pbk.) Emphasis on the military history.

- Immanuel C. Y. Hsu, The Rise of Modern China (1999), ISBN 0-19-512504-5. Standard textbook.

- Jian, Youwen (1973). The Taiping Revolutionary Movement. New Haven,: Yale University Press. ISBN 0300015429.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) Translated and condensed from the author's publications in Chinese; especially strong on the military campaigns, based on the author's wide travels in China in the 1920s and 1930s. - Kilcourse, Carl S. (2016). Taiping Theology: The Localization of Christianity in China, 1843–64. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781137537287.

- Philip A. Kuhn, Rebellion and Its Enemies in Late Imperial China; Militarization and Social Structure, 1796–1864 (Cambridge, Mass.,: Harvard University Press, 1970). Influential analysis of the rise of rebellion and the organization of its suppression.

- Philip A. Kuhn, "The Taiping Rebellion," in John K. Fairbank, ed., Cambridge History of China Vol Ten Pt One (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ Press, 1970): 264–350.

- Meyer-Fong, Tobie S. (2013). What Remains: Coming to Terms with Civil War in 19th Century China. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804754255.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) A study of the victims, their experience of the war, and the memorialization of the war. - Platt, Stephen R. (2012). Autumn in the Heavenly Kingdom: China, the West, and the Epic Story of the Taiping Civil War. New York: Knopf. ISBN 9780307271730.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) Detailed narrative analysis. - Reilly, Thomas H. (2004). The Taiping Heavenly Kingdom: Rebellion and the Blasphemy of Empire. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 0295984309.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) Focuses on the religious basis of the rebellion. - Caleb Carr, The Devil Soldier: The Story of Frederick Townsend Ward (1994) ISBN 0679411143.

- Rudolf G. Wagner. Reenacting the Heavenly Vision: The Role of Religion in the Taiping Rebellion. (Berkeley: Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California, Berkeley, China Research Monograph 25, 1982). ISBN 0912966602.

- Mary Clabaugh Wright. The Last Stand of Chinese Conservatism: The T'ung-Chih Restoration, 1862–1874. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1957; rpr. 1974 ISBN 0804704767. Account of the Han Chinese/ Manchu coalition which revived the dynasty and defeated the Taipings.

Scholarly articles

- Template:Cite article

- Perry, Elizabeth J. (1984). "Taipings and Triads: the rôle of religion in inter-rebel relations". In Bak, János M.; Benecke, Gerhard (eds.). Religion and Rural Revolt: Papers Presented to the Fourth Interdisciplinary Workshop on Peasant Studies, University of British Columbia, 1982. Manchester: Manchester University Press. pp. 342–353. ISBN 0719009901.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Fiction

- Chin, Shunshin (2001). The Taiping Rebellion. Translated by Joshua A. Fogel. orig. Taihei Tengoku. Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 0765601001.

- Hosea Ballou Morse, In the Days of the Taipings, Being the Recollections of Ting Kienchang, Otherwise Meisun, Sometime Scoutmaster and Captain in the Ever-Victorious Army and Interpreter-in-Chief to General Ward and General Gordon (Salem, MA: The Essex institute, 1927; Reprinted: San Francisco: Chinese Materials Center, 1974).

- George MacDonald Fraser. Flashman and the Dragon. New York: Knopf, 1986. ISBN 0394553578. A volume in The Flashman Papers series.

External links

- Taiping Rebellion Videos Chronological presentation of the Taiping Rebellion, with details and anecdotes.

- Taiping Rebellion.com Narrative history, with many illustrations, a Timeline, and a detailed Map of the Rebellion.

- The Taiping Rebellion [BBC] Discussion with Rana Mitter, University of Oxford; Frances Wood British Library; and Julia Lovell, University of London.

- Taiping Rebellion

- 1850 in China

- 1851 in China

- 1852 in China

- 1853 in China

- 1854 in China

- 1855 in China

- 1856 in China

- 1857 in China

- 1858 in China

- 1859 in China

- 1860 in China

- 1861 in China

- 1862 in China

- 1863 in China

- 1864 in China

- 19th century in China

- 19th-century rebellions

- Taiping Heavenly Kingdom

- Peasant revolts

- Persecution of Buddhists

- Rebellions in the Qing dynasty

- Religion-based civil wars

- Wars involving France

- Wars involving the Qing dynasty

- Wars involving the United Kingdom

- Christianity in China

- Christianization

- Eight Banners