Kennedy Space Center

| |

Clockwise from the top: Vehicle Assembly Building, Shuttle Landing Facility, Launch Control Center, Visitor Complex, KSC Headquarters Building and Space Shuttle Endeavour on Pad 39A | |

KSC shown in white; CCSFS in green | |

| Abbreviation | KSC |

|---|---|

| Named after | John F. Kennedy |

| Formation | July 1, 1962 |

| Type | NASA facility |

| Location | |

| Coordinates | 28°31′27″N 80°39′03″W / 28.52417°N 80.65083°W |

Official language | English |

| Owner | NASA |

Director | Robert D. Cabana |

Deputy director | Janet E. Petro |

Budget (2019[needs update]) | US$324 million[1][needs update] |

Staff (2019[needs update]) | 10,150[1][a][needs update] |

| Website | www |

Formerly called | Launch Operations Center |

| [2] | |

The John F. Kennedy Space Center (KSC, originally known as the NASA Launch Operations Center), located on Merritt Island, Florida, is one of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration's (NASA) ten field centers. Since December 1968, KSC has been NASA's primary launch center of human spaceflight. Launch operations for the Apollo, Skylab and Space Shuttle programs were carried out from Kennedy Space Center Launch Complex 39 and managed by KSC.[3] Located on the east coast of Florida, KSC is adjacent to Cape Canaveral Space Force Station (CCSFS). The management of the two entities work very closely together, share resources and operate facilities on each other's property.

Though the first Apollo flights and all Project Mercury and Project Gemini flights took off from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, the launches were managed by KSC and its previous organization, the Launch Operations Directorate.[4][5] Starting with the fourth Gemini mission, the NASA launch control center in Florida (Mercury Control Center, later the Launch Control Center) began handing off control of the vehicle to the Mission Control Center in Houston, shortly after liftoff; in prior missions it held control throughout the entire mission.[6][7]

Additionally, the center manages launch of robotic and commercial crew missions and researches food production and In-Situ Resource Utilization for off-Earth exploration.[8] Since 2010, the center has worked to become a multi-user spaceport through industry partnerships,[9] even adding a new launch pad (LC-39C) in 2015.

There are about 700 facilities and buildings grouped across the center's 144,000 acres (580 km2).[10] Among the unique facilities at KSC are the 525-foot (160 m) tall Vehicle Assembly Building for stacking NASA's largest rockets, the Launch Control Center, which conducts space launches at KSC, the Operations and Checkout Building, which houses the astronauts dormitories and suit-up area, a Space Station factory, and a 3-mile (4.8 km) long Shuttle Landing Facility. There is also a Visitor Complex open to the public on site.

Formation

The military had been performing launch operations since 1949 at what would become Cape Canaveral Space Force Station. In December 1959, the Department of Defense transferred 5,000 personnel and the Missile Firing Laboratory to NASA to become the Launch Operations Directorate under NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center.[11]

President John F. Kennedy's 1961 goal of a crewed lunar landing by 1970 required an expansion of launch operations. On July 1, 1962, the Launch Operations Directorate was separated from MSFC to become the Launch Operations Center (LOC). Also, Cape Canaveral was inadequate to host the new launch facility design required for the mammoth 363-foot (111 m) tall, 7,500,000-pound-force (33,000 kN) thrust Saturn V rocket, which would be assembled vertically in a large hangar and transported on a mobile platform to one of several launch pads. Therefore, the decision was made to build a new LOC site located adjacent to Cape Canaveral on Merritt Island.[citation needed]

NASA began land acquisition in 1962, buying title to 131 square miles (340 km2) and negotiating with the state of Florida for an additional 87 square miles (230 km2).[12] The major buildings in KSC's Industrial Area were designed by architect Charles Luckman.[13] Construction began in November 1962, and Kennedy visited the site twice in 1962, and again just a week before his assassination on November 22, 1963.[14]

On November 29, 1963, the facility was given its current name by President Lyndon B. Johnson under Executive Order 11129.[15][16] Johnson's order joined both the civilian LOC and the military Cape Canaveral station ("the facilities of Station No. 1 of the Atlantic Missile Range") under the designation "John F. Kennedy Space Center", spawning some confusion joining the two in the public mind. NASA Administrator James E. Webb clarified this by issuing a directive stating the Kennedy Space Center name applied only to the LOC, while the Air Force issued a general order renaming the military launch site Cape Kennedy Air Force Station.[17]

Location

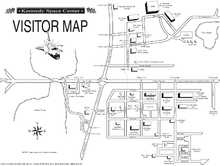

Located on Merritt Island, Florida, the center is north-northwest of Cape Canaveral on the Atlantic Ocean, midway between Miami and Jacksonville on Florida's Space Coast, due east of Orlando. It is 34 miles (55 km) long and roughly six miles (9.7 km) wide, covering 219 square miles (570 km2). KSC is a major central Florida tourist destination and is approximately one hour's drive from the Orlando area. The Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex offers public tours of the center and Cape Canaveral Space Force Station.[18]

Because much of the installation is a restricted area and only nine percent of the land is developed, the site also serves as an important wildlife sanctuary; Mosquito Lagoon, Indian River, Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge and Canaveral National Seashore are other features of the area. Center workers can encounter bald eagles, American alligators, wild boars, eastern diamondback rattlesnakes, the endangered Florida panther[citation needed] and Florida manatees.

Historical programs

Apollo program

From 1967 through 1973, there were 13 Saturn V launches, including the ten remaining Apollo missions after Apollo 7. The first of two uncrewed flights, Apollo 4 (Apollo-Saturn 501) on November 9, 1967, was also the first rocket launch from KSC. The Saturn V's first crewed launch on December 21, 1968, was Apollo 8's lunar orbiting mission. The next two missions tested the Lunar Module: Apollo 9 (Earth orbit) and Apollo 10 (lunar orbit). Apollo 11, launched from Pad A on July 16, 1969, made the first Moon landing on July 20. Apollo 12 followed four months later. From 1970 to 1972, the Apollo program concluded at KSC with the launches of missions 13 through 17.

Skylab

On May 14, 1973, the last Saturn V launch put the Skylab space station in orbit from Pad 39A. By this time, the Cape Kennedy pads 34 and 37 used for the Saturn IB were decommissioned, so Pad 39B was modified to accommodate the Saturn IB, and used to launch three crewed missions to Skylab that year, as well as the final Apollo spacecraft for the Apollo–Soyuz Test Project in 1975.

Space Shuttle

As the Space Shuttle was being designed, NASA received proposals for building alternative launch-and-landing sites at locations other than KSC, which demanded study. KSC had important advantages, including its existing facilities; location on the Intracoastal Waterway; and its southern latitude, which gives a velocity advantage to missions launched in easterly near-equatorial orbits. Disadvantages included: its inability to safely launch military missions into polar orbit, since spent boosters would be likely to fall on the Carolinas or Cuba; corrosion from the salt air; and frequent cloudy or stormy weather. Although building a new site at White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico was seriously considered, NASA announced its decision in April 1972 to use KSC for the shuttle.[19] Since the Shuttle could not be landed automatically or by remote control, the launch of Columbia on April 12, 1981 for its first orbital mission STS-1, was NASA's first crewed launch of a vehicle that had not been tested in prior uncrewed launches.

In 1976, the VAB's south parking area was the site of Third Century America, a science and technology display commemorating the U.S. Bicentennial. Concurrent with this event, the U.S. flag was painted on the south side of the VAB. During the late 1970s, LC-39 was reconfigured to support the Space Shuttle. Two Orbiter Processing Facilities were built near the VAB as hangars with a third added in the 1980s.

KSC's 2.9-mile (4.7 km) Shuttle Landing Facility (SLF) was the orbiters' primary end-of-mission landing site, although the first KSC landing did not take place until the tenth flight, when Challenger completed STS-41-B on February 11, 1984; the primary landing site until then was Edwards Air Force Base in California, subsequently used as a backup landing site. The SLF also provided a return-to-launch-site (RTLS) abort option, which was not utilized. The SLF is among the longest runways in the world.[20]

After 24 successful shuttle flights, Challenger was torn apart 73 seconds after the launch of STS-51-L on January 28, 1986; the first shuttle launch from Pad 39B and the first U.S. crewed launch failure, killing the seven crew members. An O-ring seal in the right booster rocket failed at liftoff, leading to subsequent structural failures. Flights resumed on September 29, 1988, with STS-26 after modifications to many aspects of the shuttle program.

On February 1, 2003, Columbia and her crew of seven were lost during re-entry over Texas during the STS-107 mission (the 113th shuttle flight); a vehicle breakup triggered by damage sustained during launch from Pad 39A on January 16, when a piece of foam insulation from the orbiter's external fuel tank struck the orbiter's left-wing. During reentry, the damage created a hole allowing hot gases to melt the wing structure. Like the Challenger disaster, the resulting investigation and modifications interrupted shuttle flight operations at KSC for more than two years until the STS-114 launch on July 26, 2005.

The shuttle program experienced five main engine shutdowns at LC-39, all within four seconds before launch; and one Abort to Orbit, STS-51-F on July 29, 1985. Shuttle missions during nearly 30 years of operations included deploying satellites and interplanetary probes, conducting space science and technology experiments, visits to the Russian MIR space station, construction and servicing of the International Space Station, deployment and servicing of the Hubble Space Telescope and serving as a space laboratory. The shuttle was retired from service in July 2011 after 135 launches.

Constellation

On October 28, 2009, the Ares I-X launch from Pad 39B was the first uncrewed launch from KSC since the Skylab workshop in 1973.

Expendable launch vehicles (ELVs)

Beginning in 1958, NASA and military worked side by side on robotic mission launches (previously referred to as unmanned),[21] cooperating as they broke ground in the field. In the early 1960s, NASA had as many as two robotic mission launches a month. The frequent number of flights allowed for quick evolution of the vehicles, as engineers gathered data, learned from anomalies and implemented upgrades. In 1963, with the intent of KSC ELV work focusing on the ground support equipment and facilities, a separate Atlas/Centaur organization was formed under NASA's Lewis Center (now Glenn Research Center (GRC)), taking that responsibility from the Launch Operations Center (aka KSC).[7]

Though almost all robotics missions launched from the Cape Canaveral Space Force Station (CCSFS), KSC "oversaw the final assembly and testing of rockets as they arrived at the Cape."[7] In 1965, KSC's Unmanned Launch Operations directorate became responsible all NASA uncrewed launch operations, including those at Vandenberg Air Force Base. From the 1950s to 1978, KSC chose the rocket and payload processing facilities for all robotic missions launching in the U.S., overseeing their near launch processing and checkout. In addition to government missions, KSC performed this service for commercial and foreign missions also, though non-U.S. government entities provided reimbursement. NASA also funded Cape Canaveral Space Force Station launch pad maintenance and launch vehicle improvements.

All this changed with the Commercial Space Launch Act of 1984, after which NASA only coordinated its own and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) ELV launches. Companies were able to "operate their own launch vehicles"[7] and utilize NASA's launch facilities. Payload processing handled by private firms also started to occur outside of KSC. Reagan's 1988 space policy furthered the movement of this work from KSC to commercial companies.[22] That same year, launch complexes on Cape Canaveral Air Force Force Station started transferring from NASA to Air Force Space Command management.[7]

In the 1990s, though KSC was not performing the hands-on ELV work, engineers still maintained an understanding of ELVs and had contracts allowing them insight in the vehicles so they could provide knowledgeable oversight. KSC also worked on ELV research and analysis and the contractors were able to utilize KSC personnel as a resource for technical issues. KSC, with the payload and launch vehicle industries, developed advances in automation of the ELV launch and ground operations to enable competitiveness of U.S. rockets against the global market.[7]

In 1998, the Launch Services Program (LSP) formed at KSC, pulling together programs (and personnel) that already existed at KSC, GRC, Goddard Space Flight Center, and more to manage the launch of NASA and NOAA robotic missions. Cape Canaveral Space Force Station and VAFB are the primary launch sites for LSP missions, though other sites are occasionally used. LSP payloads such as the Mars Science Laboratory have been processed at KSC before being transferred to a launch pad on Cape Canaveral Space Force Station.

Space station processing

As the International Space Station modules design began in the early 1990s, KSC began to work with other NASA centers and international partners to prepare for processing before launch on board the Space Shuttles. KSC utilized its hands-on experience processing the 22 Spacelab missions in the Operations and Checkout Building to gather expectations of ISS processing. These experiences were incorporated into the design of the Space Station Processing Facility (SSPF), which began construction in 1991. The Space Station Directorate formed in 1996. KSC personnel were embedded at station module factories for insight into their processes.[7]

From 1997 to 2007, KSC planned and performed on the ground integration tests and checkouts of station modules: three Multi-Element Integration Testing (MEIT) sessions and the Integration Systems Test (IST). Numerous issues were found and corrected that would have been difficult to nearly impossible to do on-orbit.

Today KSC continues to process ISS payloads from across the world before launch along with developing its experiments for on orbit.[23] The proposed Lunar Gateway would be manufactured and processed at the Space Station Processing Facility.

Current programs and initiatives

The following are current programs and initiatives at Kennedy Space Center:[24]

- Commercial Crew Program[25]

- Exploration Ground Systems Program[26]

- NASA is currently designing the next heavy launch vehicle known as the Space Launch System (SLS) for continuation of human spaceflight.

- On December 5, 2014, NASA launched the first uncrewed flight test of the Orion Multi-Purpose Crew Vehicle (MPCV), currently under development to facilitate human exploration of the Moon and Mars.[27][28]

- Launch Services Program[29]

- Educational Launch of Nanosatellites (ELaNa)[30]

- Research and Technology[8]

- International Space Station Payloads[23]

- Camp KSC: educational camps for schoolchildren in spring and summer, with a focus on space, aviation and robotics.[31]

Facilities

The KSC Industrial Area, where many of the center's support facilities are located, is 5 miles (8 km) south of ((LC-39.))It includes the Headquarters Building, the Operations and Checkout Building and the Central Instrumentation Facility. The astronaut crew quarters are in the O&C; before it was completed, the astronaut crew quarters were located in Hangar S[32] at the Cape Canaveral Missile Test Annex (now Cape Canaveral Space Force Station).[14] Located as KSC was the Merritt Island Spaceflight Tracking and Data Network station (MILA), a key radio communications and spacecraft tracking complex.

Facilities at the Kennedy Space Center are directly related to its mission to launch and recover missions. Facilities are available to prepare and maintain spacecraft and payloads for flight.[33][34] The Headquarters (HQ) Building houses offices for the Center Director, library, film and photo archives, a print shop and security.[35] The library contains over four million items related to the history and the work at Kennedy. As one of ten NASA center libraries in the country, their collection focuses on engineering, science, and technology. The archives contain planning documents, film reels, and original photographs covering the history of KSC. The library is not open to the public, but is available for KSC, Space Force, and Navy employees who work on site.[36] Many of the media items from the collection are digitized and available through NASA's KSC Media Gallery or through their more up-to-date Flickr gallery.

A new Headquarters Building is under construction as a part of the Central Campus consolidation and the first phase is expected to be complete in 2017.[10][37][38][39]

The center operated its own 17-mile (27 km) short-line railroad.[40] This operation was discontinued in 2015, with the sale of its final two locomotives. A third had already been donated to a museum. The line was costing $1.3 million annually to maintain.[41]

Payload processing

- The Operations and Checkout Building (O&C) (previously known as the Manned Spacecraft Operations Building) is a historic site on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places dating back to the 1960s and was used to receive, process, and integrate payloads for the Gemini and Apollo programs, the Skylab program in the 1970s, and for initial segments of the International Space Station through the 1990s.[42] The Apollo and Space Shuttle astronauts would board the astronaut transfer van to launch complex 39 from the O&C building.[43]

- The three-story, 457,000-square-foot (42,500 m2) Space Station Processing Facility (SSPF) consists of two processing bays, an airlock, operational control rooms, laboratories, logistics areas and office space for support of non-hazardous Station and Shuttle payloads to ISO 14644-1 class 5 standards.[44]

- The Vertical Processing Facility (VPF) features a 71-by-38-foot (22 by 12 m) door where payloads which are processed in the vertical position are brought in and manipulated with two overhead cranes and a hoist capable of lifting up to 35 short tons (32 t).[45]

- The Hypergolic Maintenance and Checkout Area (HMCA) comprises three buildings which are isolated from the rest of the industrial area because of the hazardous materials handled there. Hypergolic-fueled modules that made up the Space Shuttle Orbiter's reaction control system, orbital maneuvering system and auxiliary power units were stored and serviced in the HMCF.[46]

- The Multi-Payload Processing Facility is a 19,647 square feet (1,825.3 m2)[47] building used for Orion spacecraft and payload processing.

- The Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility (PHSF) contains a 70-by-110-foot (21 by 34 m) service bay, with a 100,000-pound (45,000 kg), 85-foot (26 m) hook height. It also contains a 58-by-80-foot (18 by 24 m) payload airlock. Its temperature is maintained at 70 °F (21 °C).[48]

Launch Complex 39

Launch Complex 39 (LC-39) was originally built for the Saturn V, the largest and most powerful operational launch vehicle in history, for the Apollo crewed Moon landing program. Since the end of the Apollo program in 1972, LC-39 has been used to launch every NASA human space flight, including Skylab (1973), the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project (1975), and the Space Shuttle program (1981–2011).

Since December 1968, all launch operations have been conducted from launch pads A and B at LC-39. Both pads are on the ocean, 3 miles (4.8 km) east of the VAB. From 1969 to 1972, LC-39 was the "Moonport" for all six Apollo crewed Moon landing missions using the Saturn V,[49] and was used from 1981 to 2011 for all Space Shuttle launches.

Human missions to the Moon required the large three-stage Saturn V rocket, which was 363 feet (111 meters) tall and 33 feet (10 meters) in diameter. At KSC, Launch Complex 39 was built on Merritt Island to accommodate the new rocket. Construction of the $800 million project began in November 1962. LC-39 pads A and B were completed by October 1965 (planned Pads C, D and E were canceled), the VAB was completed in June 1965, and the infrastructure by late 1966.

The complex includes:

- the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB), a 130,000,000 cubic feet (3,700,000 m3) hangar capable of holding four Saturn Vs. The VAB was the largest structure in the world by volume when completed in 1965.[50]

- a transporter capable of carrying 5,440 tons along a crawlerway to either of two launch pads;

- a 446-foot (136 m) mobile service structure, with three Mobile Launcher Platforms, each containing a fixed launch umbilical tower;

- the Launch Control Center; and

- a news media facility.

Launch Complex 48

Launch Complex 48 (LC-48) is a multi-user launch site under construction for small launchers and spacecraft. It will be located between Launch Complex 39A and Space Launch Complex 41, with LC-39A to the north and SLC-41 to the south.[51] LC-48 will be constructed as a "clean pad" to support multiple launch systems with differing propellant needs. While initially only planned to have a single pad, the complex is capable of being expanded to two at a later date.[52]

Commercial leasing

As a part of promoting commercial space industry growth in the area and the overall center as a multi-user spaceport,[53][54] KSC leases some of its properties. Here are some major examples:

- Exploration Park to multiple users (partnership with Space Florida)

- Shuttle Landing Facility to Space Florida (who contracts use to private companies)

- Orbiter Processing Facility (OPF)-3 to Boeing (for CST-100 Starliner)

- Launch Complex 39A to SpaceX

- O&C High Bay to Lockheed Martin (for Orion processing)

- Land for FPL's Space Coast Next Generation Solar Energy Center to Florida Power and Light (FPL)[55][56][57]

- Hypergolic Maintenance Facility (HMF) to United Paradyne Corporation (UPC)[58]

Visitor complex

The Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex, operated by Delaware North since 1995, has a variety of exhibits, artifacts, displays and attractions on the history and future of human and robotic spaceflight. Bus tours of KSC originate from here. The complex also includes the separate Apollo/Saturn V Center, north of the VAB and the United States Astronaut Hall of Fame, six miles west near Titusville. There were 1.5 million visitors in 2009. It had some 700 employees.[59]

It was announced on May 29, 2015 that the Astronaut Hall of Fame exhibit would be moved from its current location to another location within the Visitor Complex to make room for an upcoming high-tech attraction entitled "Heroes and Legends". The attraction, designed by Orlando-based design firm Falcon's Treehouse, opened November 11th, 2016.[60]

In March 2016, the visitor center unveiled the new location of the iconic countdown clock at the complex's entrance; previously, the clock was located with a flagpole at the press site. The clock was originally built and installed in 1969 and listed with the flagpole in the National Register of Historic Places in January 2000.[61] In 2019, NASA celebrates the 50th anniversary of the Apollo program, and the launch of Apollo 10 on May 18.[62] In summer of 2019, Lunar Module 9 (LM-9) will be relocated to the Apollo/Saturn V Center as part of an initiative to rededicate the center and celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Apollo Program.

Historic locations

NASA lists the following Historic Districts at KSC; each district has multiple associated facilities:[63][64][65]

- Launch Complex 39: Pad A Historic District

- Launch Complex 39: Pad B Historic District

- Shuttle Landing Facility (SLF) Area Historic District

- Orbiter Processing Historic District

- Solid Rocket Booster (SRB) Disassembly and Refurbishment Complex Historic District

- NASA KSC Railroad System Historic District

- NASA-owned Cape Canaveral Space Force Station Industrial Area Historic District

There are 24 historic properties outside of these historic districts, including the Space Shuttle Atlantis, Vehicle Assembly Building, Crawlerway, and Operations and Checkout Building.[63] KSC has one National Historic Landmark, 78 National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) listed or eligible sites, and 100 Archaeological Sites.[66]

Other facilities

- The Rotation, Processing and Surge Facility (RPSF) is responsible for the preparation of solid rocket booster segments for transportation to the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB). The RPSF was built in 1984 to perform SRB operations that had previously been conducted in high bays 2 and 4 of the VAB at the beginning of the Space Shuttle program. It was used until the Space Shuttle's retirement, and will be used in the future by the Space Launch System[67] (SLS) and OmegA rockets.

Weather

Florida's peninsular shape and temperature contrasts between land and ocean provide ideal conditions for electrical storms, earning Central Florida the reputation as "lightning capital of the United States".[68][69] This makes extensive lightning protection and detection systems necessary to protect employees, structures and spacecraft on launch pads.[70] On November 14, 1969, Apollo 12 was struck by lightning just after lift-off from Pad 39A, but the flight continued safely. The most powerful lightning strike recorded at KSC occurred at LC-39B on August 25, 2006, while shuttle Atlantis was being prepared for STS-115. NASA managers were initially concerned that the lightning strike caused damage to Atlantis, but none was found.[71]

On September 7, 2004, Hurricane Frances directly hit the area with sustained winds of 70 miles per hour (110 km/h) and gusts up to 94 miles per hour (151 km/h), the most damaging storm to date. The Vehicle Assembly Building lost 1,000 exterior panels, each 3.9 feet (1.2 m) x 9.8 feet (3.0 m) in size. This exposed 39,800 sq ft (3,700 m2) of the building to the elements. Damage occurred to the south and east sides of the VAB. The shuttle's Thermal Protection System Facility suffered extensive damage. The roof was partially torn off and the interior suffered water damage. Several rockets on display in the center were toppled.[72] Further damage to KSC was caused by Hurricane Wilma in October 2005.

The conservative estimate by NASA is that the Space Center will experience 5 to 8 inches of sea level rise by the 2050s. Launch Complex 39A, the site of the Apollo 11 launch, is the most vulnerable to flooding, and has a 14% annual risk of flooding beginning in 2020.[73][74]

KSC directors

Since KSC's formation, ten NASA officials have served as directors, including three former astronauts (Crippen, Bridges and Cabana):

| Name | Start | End | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dr. Kurt H. Debus | July 1962 | November 1974 | [75] |

| Lee R. Scherer | January 19, 1975 | September 2, 1979 | [76] |

| Richard G. Smith | September 26, 1979 | August 2, 1986 | [77] |

| Forrest S. McCartney | August 31, 1987 | December 31, 1991 | [78] |

| Robert L. Crippen | January 1992 | January 1995 | [79] |

| Jay F. Honeycutt | January 1995 | March 2, 1997 | [80] |

| Roy D. Bridges, Jr. | March 2, 1997 | August 9, 2003 | [81] |

| James W. Kennedy | August 9, 2003 | January 2007 | [82] |

| William W. Parsons | January 2007 | October 2008 | [83] |

| Robert D. Cabana | October 2008 | present | [84] |

Labor force

When KSC separated from Marshall Space Flight Center in July 1962, it took 375 employees with it.

In May 1965, KSC had 7,000 employees and contractors move from rented space in Cocoa Beach to the new Merritt Island facilities. The peak number of persons working on center was 26,000 in 1968 (3,000 were civil servants). In 1970, President Nixon announced intent to reduce cost of space operations and major cuts occurred at KSC. By 1974, KSC's workforce was down to 10,000 employees (2,408 civil servants).[7]

A total of 13,100 people worked at the center as of 2011. Approximately 2,100 are employees of the federal government; the rest are contractors.[85] The average annual salary for an on-site worker in 2008 was $77,235.[86]

The end of the Space Shuttle program in 2011, preceded by the cancellation of Constellation Program in 2010, produced a significant downsizing of the KSC workforce similar to that experienced at the end of the Apollo program in 1972. As part of this downsizing, 6,000 contractors lost their jobs at the center during 2010 and 2011.[87]

In popular culture

In addition to being frequently featured in documentaries, Kennedy Space Center has been portrayed on film many times. Some studio movies have even gained access and filmed scenes within the gates of the space center. If extras are needed in those scenes, space center employees are recruited (employees use personal time during filming). Films with scenes at KSC include:[88]

- Moonraker

- SpaceCamp

- Apollo 13

- Contact

- Armageddon[89]

- Space Cowboys

- Swades

- Transformers 3: Dark of the Moon

- Tomorrowland

- Sharknado 3: Oh Hell No!

- First Man

- Geostorm

Several television shows have had KSC as one of the primary settings, though not necessarily with any scenes filmed on center:

British-Irish band One Direction also filmed their music video for "Drag Me Down" at KSC.

See also

- Air Force Space and Missile Museum

- Astronaut beach house

- Kerbal Space Program

- List of memorials to John F. Kennedy

- List of tallest buildings and structures in the world

- Mobile launcher platform

- NASA Causeway

- Solar eclipse of August 12, 2045 (Kennedy Space Center will be in the path of totality)

- Swamp Works

References

Notes

- ^ Number includes commercial tenants.

Citations

- ^ a b 2019 Kennedy Space Center Annual Report (PDF). NASA. 2019. pp. 50, 52. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ "Kennedy Business Report" (PDF). Annual Report FY2010. NASA. February 2011. Retrieved August 22, 2011.

- ^ "Kennedy Space Center Implementing NASA's Strategies" (PDF). NASA. 2000. Retrieved November 5, 2015.

- ^ "Appendix 10 – Government Organizations Supporting Project Mercury". NASA History Program Office. NASA. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

- ^ "2. Project Support from the NASA Centers". Mercury Project Summary (NASA SP-45). NASA. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

- ^ "Mercury Mission Control". NASA. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Lipartito, Kenneth; Butler, Orville (2007). 'A History of the Kennedy Space Center. University Press of Florida. ISBN 978-0-8130-3069-2.

- ^ a b "Research & Technology". Kennedy Space Center. NASA. Retrieved November 5, 2015.

- ^ "NASA Partnerships Launch Multi-User Spaceport". NASA. May 1, 2014. Retrieved November 5, 2015.

- ^ a b "Kennedy Creating New Master Plan". NASA. March 12, 2012. Retrieved November 5, 2015.

- ^ "Kennedy Space Center Story". NASA. Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- ^ Charles D. Benson and William Barnaby Faherty. "Land, Lots of Land – Much of It Marshy". Moonport: A History of Apollo Launch Facilities and Operations. NASA. Retrieved August 27, 2009.

- ^ Muschamp, Herbert (January 28, 1999). "Charles Luckman, Architect Who Designed Penn Station's Replacement, Dies at 89". The New York Times. Retrieved August 22, 2011.

- ^ a b "Kennedy History Quiz". NASA. Retrieved November 5, 2015.

- ^ "The National Archives, Lyndon B. Johnson Executive Order 11129". Retrieved April 26, 2010.

- ^ "Kennedy Space Center Story". NASA. 1991. Retrieved November 5, 2015.

- ^ Benson, Charles D.; Faherty, William B. (August 1977). "Chapter 7: The Launch Directorate Becomes an Operational Center – Kennedy's Last Visit". Moonport: A History of Apollo Launch Facilities and Operations. History Series. Vol. SP-4204. NASA. Archived from the original on November 6, 2004.

- ^ "See All Attractions | Kennedy Space Center". www.kennedyspacecenter.com. Retrieved June 5, 2020.

- ^ Heppenheimer, T. A. (1998). The Space Shuttle Decision. NASA. pp. 425–427. Archived from the original on October 30, 2004.

- ^ Shuttle Landing Facility (SLF). Science.ksc.nasa.gov. Retrieved on May 5, 2012.

- ^ "Style Guide for NASA History Authors and Editors". NASA's History Office. NASA. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

- ^ "Presidential Directive on National Space Policy". NASA. White House. February 11, 1988. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

- ^ a b "Kennedy Space Center Payload Processing". NASA. Retrieved November 5, 2015.

- ^ "Kennedy Space Center". NASA. Retrieved November 5, 2015.

- ^ "Commercial Crew Program". NASA. Retrieved November 5, 2015.

- ^ "Exploration Ground Systems". NASA. Retrieved October 13, 2018.

- ^ Garcia, Mark (April 12, 2015). "Orion Overview". NASA. Retrieved January 17, 2017.

- ^ "Orion Explained: NASA's Multi-Purpose Crew Vehicle (Infographic)". Space.com. Retrieved January 17, 2017.

- ^ "Launching Rockets". NASA. Retrieved November 5, 2015.

- ^ "Small Satellite Missions". NASA. Retrieved November 5, 2015.

- ^ "Camp Kennedy Space Center and Space Camp". NASA. Retrieved September 18, 2019.

- ^ "Hangar S History". Kennedy Space Center. NASA. Retrieved November 5, 2015.

- ^ "iv. Kennedy Space Center Planning and Development Office – What We Offer – Physical Assets". Archived from the original on April 4, 2014. Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- ^ "Kennedy Space Center Resource Encyclopedia". NASA – Kennedy Space Center. 2010. Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- ^ Headquarters Building (HQ). Science.ksc.nasa.gov. Retrieved on May 5, 2012.

- ^ Borchert, Carol Ann; Arthur, Michael A. (2007). Ginanni, Katy (ed.). "John F. Kennedy Space Center Library". Serials Review. 33: 277–280. doi:10.1016/j.serrev.2007.08.012 – via Academia.edu.

- ^ "Kennedy Space Center Central Campus". NASA. Retrieved February 3, 2016.

- ^ "Central Campus of the Kennedy Space Center" (PDF). Kennedy Space Center Fact Sheets. NASA. Retrieved February 3, 2016.

- ^ "Media Invited to Groundbreaking for New Kennedy Space Center Headquarters". NASA. October 2, 2014. Retrieved November 5, 2015.

- ^ "The NASA Railroad" (PDF). Kennedy Space Center Fact Sheets. NASA. Retrieved February 3, 2016.

- ^ Dean, James (May 24, 2015). "NASA Railroad rides into sunset". Florida Today. Melbourne, Florida. pp. 25A. Retrieved June 2, 2015.

- ^ "Operations and Checkout Building".

- ^ Mansfield, Cheryl L. (July 15, 2008). "Catching a Ride to Destiny". NASA. Retrieved July 13, 2009.

- ^ Space Station Processing Facility (SSPF). Science.ksc.nasa.gov. Retrieved on May 5, 2012.

- ^ Vertical Processing Facility. Science.ksc.nasa.gov. Retrieved on May 5, 2012.

- ^ "Hypergolic Maintenance and Checkout Facility".

- ^ Granath, Bob (August 25, 2016). "Multi-Payload Processing Facility Provides 'Gas Station' for Orion". NASA. Retrieved December 1, 2019.

- ^ "Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility". Science.ksc.nasa.gov. Retrieved May 2, 2018.

- ^ Benson, Charles D.; Faherty, William B. (August 1977). "Preface". Moonport: A History of Apollo Launch Facilities and Operations. History Series. Vol. SP-4204. NASA.

- ^ "Senate". Congressional Record: 17598. September 8, 2004.

- ^ Kelly, Emre (June 14, 2019). "Meet Launch Complex 48, NASA's new small rocket pad at Kennedy Space Center". Florida Today. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

- ^ Draft Environmental Assessment for Launch Complex 48 (PDF). NASA. February 19, 2019. pp. ii–iii. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

- ^ "Partnering with KSC". Archived from the original on November 4, 2015.

- ^ "The Front Page Archive". Doing Business With Kennedy. NASA. Retrieved November 5, 2015.

- ^ "Partnering with KSC".

- ^ "Solar Energy Centers". FPL.

- ^ "Space Coast Next Generation Solar Energy Center". Sustainability. NASA. Retrieved November 5, 2015.

- ^ "Partnering with KSC".

- ^ Stratford, Amanda (January 12, 2010). "NASA's new image". Florida Today. Melbourne, Florida: Florida Today. pp. 1A.

- ^ Dean, James. "KSC Visitor Complex introduces 'Heroes and Legends'". Florida Today. Retrieved August 6, 2015.

- ^ "Iconic KSC countdown clock gets a new home". News 13. March 1, 2016. Retrieved March 2, 2016.

- ^ https://www.kennedyspacecenter.com/launches-and-events/events-calendar/2019/may/event-apollo-10

- ^ a b "Historic Properties at Kennedy Space Center As of January 2015" (PDF). Environmental Planning – Cultural Resources. NASA. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 3, 2016. Retrieved November 5, 2015.

- ^ "Understanding NASA's Historic Districts" (PDF). Environmental Program at KSC. NASA. June 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 17, 2015. Retrieved November 5, 2015.

- ^ "Environmental Planning – Cultural Resources". Environmental Program at KSC. NASA. Archived from the original on September 22, 2015. Retrieved November 5, 2015.

- ^ "NASA's Historic Preservation Program: Celebrating and Managing Significant Historic Resources" (PDF). NASA. Retrieved November 5, 2015.

- ^ "NASAfacts: Rotation, Processing and Surge Facility (RPSF) at Kennedy Space Center" (PDF). NASA. Retrieved December 21, 2019.

- ^ Oliver, John E. (2005). Encyclopedia of world climatology. Springer. p. 452. ISBN 978-1-4020-3264-6.

- ^ "Lightning: FAQ". UCAR Communications. University Corporation for Atmospheric Research. Archived from the original on March 16, 2010. Retrieved June 17, 2010.

- ^ KSC – Lightning and the Space Program Archived September 24, 2008, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved May 28, 2008

- ^ "NASA Checks Shuttle After Lightning Strike Near Launch Pad". Space.com. Retrieved October 19, 2017.

- ^ "NASA Assesses Hurricane Frances Damage". NASA Press Release.

- ^ Horn-Muller, Ayurella; Joy, Rachael (November 14, 2019). "Could Kennedy Space Center launch pads be at risk as climate changes? Experts say yes". Climate Central / Florida Today. Retrieved December 11, 2019.

- ^ "Future Flood Risk: John F. Kennedy Space Center & Cape Canaveral Air Force Station" (PDF). Climate Central. October 2019. Retrieved December 11, 2019.

- ^ NASA – Biography of Dr. Kurt H. Debus. Nasa.gov. Retrieved on May 5, 2012.

- ^ NASA – Biography of Lee R. Scherer. Nasa.gov. Retrieved on May 5, 2012.

- ^ NASA – Biography of Richard G. Smith. Nasa.gov. Retrieved on May 5, 2012.

- ^ NASA – Biography of Forrest S. McCartney. Nasa.gov. Retrieved on May 5, 2012.

- ^ NASA – Biography of Robert L. Crippen. Nasa.gov. Retrieved on May 5, 2012.

- ^ NASA – Biography of Jay F. Honeycutt. Nasa.gov. Retrieved on May 5, 2012.

- ^ NASA – Biography of Roy Bridges. Nasa.gov. Retrieved on May 5, 2012.

- ^ NASA – NASA KSC Director Announces Retirement. Nasa.gov (February 24, 2008). Retrieved on May 5, 2012.

- ^ NASA – Biography of William W. (Bill) Parsons. Nasa.gov (February 24, 2008). Retrieved on May 5, 2012.

- ^ "Cabana to Succeed Parsons as Kennedy Space Center Director" (Press release). NASA. September 30, 2008. Retrieved September 30, 2008.

- ^ Dean, James (March 17, 2011). "NASA budget woes leads to layoffs". Federal Times. Retrieved August 21, 2011.

- ^ Peterson, Patrick (November 28, 2010). "High-paying jobs scant outside KSC". Melbourne, Florida: Florida Today. pp. 1A.

- ^ Dean, James (November 5, 2011). "Laid-off KSC workers' supplies eagerly accepted by educators". Florida Today. Melbourne, Florida. pp. 2B.

- ^ Sangalang, Jennifer (January 19, 2018). "Hey, girl: Casting call for Ryan Gosling movie 'First Man' at Kennedy Space Center". Florida Today. USA Today Network. Retrieved January 30, 2018.

- ^ "Armageddon Production Notes". Michael Bay. Retrieved January 30, 2018.

Bibliography

- Benson, Charles W.; Faherty, William Barnaby (1978). Moonport: A History of Apollo Launch Facilities and Operations. Scientific and Technical Information Office, NASA. Archived from the original on November 17, 2004..

- Middleton, Sallie. "Space Rush: Local Impact of Federal Aerospace Programs on Brevard and Surrounding Counties," Florida Historical Quarterly, Fall 2008, Vol. 87 Issue 2, pp 258–289

- Reynolds, David West (September 2006). Kennedy Space Center: Gateway to Space. Buffalo, New York: Firefly Books. ISBN 978-1-55407-039-8. Retrieved January 30, 2010.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

External links

- Kennedy Space Center Web site

- Kennedy History Vault

- Spaceport News KSC Employee Magazine

- KSC Visitor Complex Web site

- Streaming audio of KSC radio communications

- Astronauts Memorial Foundation Web site

- "America's Space Program: Exploring a New Frontier", a National Park Service Teaching with Historic Places lesson plan

- "Aviation: From Sand Dunes to Sonic Booms", a National Park Service Discover Our Shared Heritage travel itinerary

- A Field Guide to American Spacecraft

- Documentary of the U.S. Space Program in Florida

- Kennedy Space Center

- NASA facilities

- Aerospace museums in Florida

- Buildings and structures in Merritt Island, Florida

- Monuments and memorials to John F. Kennedy in the United States

- Government buildings in Florida

- IMAX venues

- Industrial buildings and structures in Florida

- Museums in Brevard County, Florida

- Government buildings on the National Register of Historic Places in Florida

- Industrial buildings and structures on the National Register of Historic Places in Florida

- National Register of Historic Places in Brevard County, Florida

- Parks and attractions with Angry Birds exhibits

- Rocket launch sites in the United States

- Science museums in Florida

- Spaceports in the United States

- Titusville, Florida

- Government buildings completed in 1962

- 1962 establishments in Florida

- Tourist attractions in Brevard County, Florida